Abstract

The utility of promoters regulated by the bacteriophage P1 temperature-sensitive C1 repressor was examined in Shigella flexneri and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Promoters carrying C1 operator sites driving LacZ expression had induction/repression ratios of up to 240-fold in S. flexneri and up to 50-fold in K. pneumoniae. The promoters exhibited remarkably low basal expression, demonstrated modulation by temperature, and showed rapid induction. This system will provide a new opportunity for controlled gene expression in enteric gram-negative bacteria.

Many regulated promoter systems have been described for use in Escherichia coli. These systems include promoters regulated by LacI (2), AraC (9), and TetR (18) or combinations that can provide both low basal and high induced expression. Each system has shown utility with varying success in other bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (6), Corynebacterium glutamicum (4), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (22), and Xanthomonas campestris (27). However, few or no data exist for a regulated promoter system in the medically important species Klebsiella pneumoniae (14) and Shigella flexneri. Klebsiella species cause approximately 8% of nosocomial infections in the United States and are commonly found in both humans and the environment (23). In contrast, Shigella species, found mainly in humans, cause shigellosis, which is characterized by cramps, fever, and dysentery (1).

The temperate bacteriophage P1 can infect and lysogenize several enterobacterial species, including K. pneumoniae and Shigella dysenteriae (21, 30). Stable lysogeny is maintained by the action of the components of the tripartite immunity system (for a review, see reference 10). The C1 repressor protein acts as a central regulator by binding to and negatively regulating promoter elements for a variety of genes (7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 17, 28). The C1 asymmetric operator sites (consensus sequence ATTGCTCTAATAAATTT) are widely dispersed over the P1 genome and are numbered according to their positions on the P1 genetic map (10, 30).

In this report, we describe a temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoter system in a broad-host-range plasmid for controlled gene expression in both K. pneumoniae and S. flexneri.

Characteristics and construction of the expression vectors.

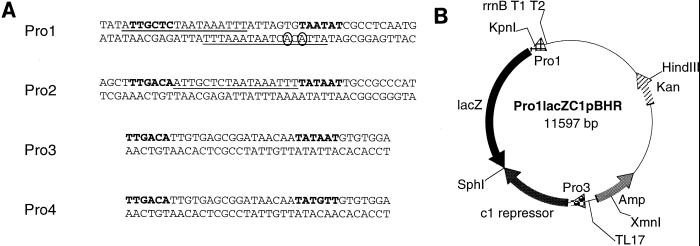

The lacZ reporter gene vectors were constructed in the broad-host-range gram-negative plasmid pBBR122 (Mobitec). The lacZ gene was placed under the transcriptional control of two C1-regulated promoters (Fig. 1A). The Pro1 promoter is based on the promoter responsible for driving ban gene expression in bacteriophage P1 and has been shown to be effectively repressed in E. coli in the presence of C1 (11, 26). It consists of two overlapping C1 operator sites but lacks consensus E. coli −10 and −35 promoter elements. In contrast, the artificial promoter (Pro2) contains a consensus C1 operator site flanked by consensus −10 and −35 promoter elements. To prevent read-through from cryptic promoters and runaway transcription, the ribosomal terminators rrnB T1 T2 (5) and TL17 (29) were placed at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the expression cassette, respectively (Fig. 1B). To control gene expression, the temperature-sensitive c1 gene (25) from the thermoinducible bacteriophage P1Cm carrying the c1.100 mutation (kindly provided by Michael Yarmolinsky) was PCR amplified and placed under the transcriptional control of either a promoter containing consensus E. coli −10 and −35 promoter elements (Pro3) or a promoter containing two mismatches from consensus (Pro4) (Fig. 1A). These constructs were expected to provide differing amounts of the C1 repressor. At the permissive temperature, C1 binds to its operator site and prevents transcription from the gene of interest, while at the nonpermissive temperature, C1 is thermally unstable, thereby allowing transcription to proceed. Where indicated below, the coi gene (3) from bacteriophage P1 was PCR amplified and placed 3′ of the lacZ gene to ensure full derepression from the promoters.

FIG. 1.

Construction of the bacteriophage P1-derived C1-regulated promoter system. (A) Topography and sequence of the promoters. The Pro1 promoter consists of two partially overlapping C1 operators (top and bottom strand, as indicated by the underlined sequences). The top C1 operator site matches the 17-bp consensus (8, 11) while the bottom operator deviates from the consensus by two nucleotides (circled bases). The Pro1 promoter has been reported to exhibit a high level of expression in E. coli (26), even though it differs markedly from the E. coli consensus −10 and −35 hexamers. The proposed −10 and −35 promoter elements are shown in bold. The artificial promoter (Pro2) contains a consensus C1 operator site flanked by consensus −10 and −35 hexamers. Pro3 and Pro4 drive c1 expression. Pro3 consists of consensus hexamers, while Pro4 contains two nucleotides that do not match the consensus. (B) Map of the Pro1lacZc1pBHR vector with its relevant features. The lacZ reporter gene vectors were constructed in the broad-host-range gram-negative plasmid pBBR122 (Mobitec). The vector was modified to contain two antibiotic-resistant markers to facilitate selection. The expression cassette is flanked by terminators at the 5′ (5) and 3′ (29) ends. The sequence is available on request.

Analysis of β-Gal activity from temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoters in S. flexneri.

As P1 is able to lysogenize a wide variety of gram-negative bacteria, including K. pneumoniae (21) and Shigella species (30), it was postulated that the C1 protein would be functional in those bacteria. β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) expression under the control of two C1-regulated promoters was examined at the permissive (31°C) and nonpermissive (42°C) temperatures in S. flexneri ATCC 12022 (Table 1), which was transformed with the reporter plasmids as described previously (15). In the absence of C1, the activities from both promoters were high, with Pro1 being stronger than Pro2. This result suggested that promoter recognition elements other than the consensus −10 and −35 hexamers were being efficiently recognized in S. flexneri. In the presence of C1 and at the permissive temperature, the β-Gal activity from both promoters was significantly reduced, indicating that C1 can efficiently repress expression. In particular, the basal expression of Pro1 was extremely low compared to that of Pro2 (1 compared to 69 Miller units), which may be a reflection of the two overlapping C1 binding sites located within this promoter (Fig. 1A). The basal expression of Pro1 was similar to the background activity levels displayed by the control strain carrying the plasmid containing the promoterless lacZ gene. This indicated that the promoter was completely repressed in the presence of C1, a finding that has been demonstrated previously for E. coli (11, 26). Little difference was observed in the basal levels of expression when C1 was expressed from either a consensus promoter (Pro3) or a promoter with two mismatches in the conserved hexamers (Pro4).

TABLE 1.

Basal and induced activities from lacZ fusions to C1-regulated promoters in S. flexneria

| Construct | Presence of C1 repressor | Activity (Miller units)

|

Fold induction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal, at 31°C | Induced, at 42°C | |||

| Control | + | 2.9 | 3.1 | 1.1 |

| Pro1lacZ | − | 924.9 | 932.9 | 1.0 |

| Pro1lacZ | + | 0.9 | 90 | 100 |

| Pro1lacZ*b | + | 1.1 | 176.9 | 161 |

| Pro2lacZ | − | 622.4 | 628.3 | 1.0 |

| Pro2lacZ | + | 69.2 | 576.3 | 8.4 |

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.1 in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 31°C. The cultures were then divided equally and incubated at 42 or 31°C for 105 min prior to being assayed for β-Gal activity (OD600, approximately 0.6). The control strain carried a plasmid containing c1 and a promoterless lacZ gene. β-Gal activity was measured according to the method of Miller (20), and samples (n = 3) were assayed in triplicate (standard deviation, <5%).

Asterisk denotes the Pro4 promoter driving c1.

To examine the levels of induction from both promoters, the cultures were incubated at the permissive temperature, divided equally, and shifted to the nonpermissive temperature for 95 min to allow for expression of LacZ (Table 1). This process resulted in a significant increase in β-Gal activity from both promoters, although for Pro1 this level was still below fully induced levels. Nevertheless, this increase represented an induction of up to 161-fold for Pro1, depending on the expression signals for the promoter driving C1. Pro2 exhibited a much lower level of induction (eightfold) than Pro1, primarily because of its leaky expression. However, the results indicated that a temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoter can be effectively repressed to levels comparable to those of the control vectors yet give high levels of induced expression. This system represents the first heterologous regulated promoter system to be described for S. flexneri.

Analysis of β-Gal activity from temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoters in K. pneumoniae.

A regulated promoter system utilizing the LacI repressor in K. pneumoniae has been described previously (14). However, the level of induction and, more importantly, the basal level of expression were not quantitated. Therefore, the expression of LacZ from C1-regulated promoters was also examined in K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 (Table 2), which was transformed as described previously (19). As for S. flexneri, Pro1 was stronger than Pro2 and, in the presence of C1, exhibited extremely low levels of basal expression that were comparable to those of control vectors. These results indicate that the promoters are being efficiently recognized by the transcriptional machinery and that C1 can effectively repress transcription. However, unlike for S. flexneri, levels of induction were modest (4- to 27-fold). While still retaining low basal expression, the highest levels of expression of Pro1 and Pro2 were achieved when the weaker promoter driving C1 was utilized (5 and 58 Miller units, respectively). This suggests that high induced expression cannot be achieved if the repressor molecule is overexpressed. To increase the levels of derepression at elevated temperatures, the level of available C1 was controlled by cloning the coi gene 3′ of lacZ, thereby transcriptionally coupling its expression to lacZ. The coi gene encodes the C1 inactivator protein from bacteriophage P1 (12), which exerts its antagonistic effect by forming a complex with the C1 repressor (13). A previous study has shown that the presence of Coi interferes with the ability of C1 to prevent transcription from a C1-regulated promoter (3), which resulted in high levels of induced expression. However, while these high levels of expression resulted in 19-fold induction, the basal expression from this vector was also increased. Therefore, this construct may be more suitable when high levels of induced activity are desired. In summary, good regulation (27-fold) of β-Gal activity can be achieved in K. pneumoniae and, depending on the constructs utilized, can yield either low basal expression or fully induced activity.

TABLE 2.

Basal and induced activities from lacZ fusions to C1-regulated promoters in K. pneumoniaea

| Construct | Presence of C1 repressor | Activity (Miller units)

|

Fold induction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal, at 31°C | Induced, at 42°C | |||

| Control | + | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.3 |

| Pro1lacZ | − | 409.9 | 536.0 | 1.3 |

| Pro1lacZ | + | 1.4 | 5.2 | 3.7 |

| Pro1lacZ*b | + | 2.2 | 58.6 | 26.6 |

| Pro1lacZcoi | + | 36.4 | 697.9 | 19 |

| Pro2lacZ | − | 307.7 | 457.0 | 1.5 |

| Pro2lacZ | + | 36.9 | 221.2 | 6.0 |

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 and grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.1 in LB medium at 31°C. The cultures were then divided equally and incubated at 42 or 31°C for 75 min prior to being assayed for β-Gal activity (OD600, approximately 0.6). The control strain carried a plasmid containing c1 and a promoterless lacZ gene. Values are averages of results for multiple cultures (n = 3) assayed in triplicate (standard deviation, <5%).

Asterisk denotes the Pro4 promoter driving c1.

Modulation of β-Gal activity in S. flexneri and K. pneumoniae.

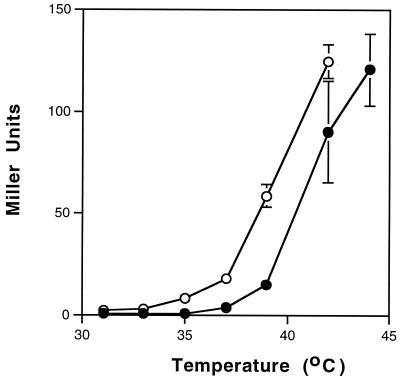

An important feature of a controlled expression system is the ability to obtain different levels of expression by partial induction of the promoter. Therefore, to assess the ability to modulate a temperature-sensitive C1 promoter system, we measured the extent of induction from Pro1 at different temperatures. The results indicated that it was possible to achieve partial induction of the promoter (Fig. 2). However, the ability to modulate activity was more pronounced in K. pneumoniae than in S. flexneri. For example, incubation at 37 and 39°C for K. pneumoniae resulted in 15 and 50% of maximal levels of induced activity, respectively. In contrast, the percentages for S. flexneri were only 4 and 17% of maximal levels of induced activity under the same conditions. Maximal induction was achieved at 42°C or higher, which is consistent with other temperature-sensitivity-regulated promoter systems (24).

FIG. 2.

Modulation of expression from the Pro1 C1-regulated promoter in S. flexneri (●) and K. pneumoniae (○). Overnight cultures carrying the Pro1 C1∗ reporter construct (the asterisk indicates that the Pro4 promoter drives c1) were diluted 1:100 and grown in LB medium at 31°C. The culture was then divided equally and incubated for 105 min (S. flexneri) or 30 min (K. pneumoniae) at the designated temperatures prior to being assayed for β-Gal activity (OD600 at time of harvesting, approximately 0.6). Values (± standard deviations) are averages of results for duplicate cultures assayed in triplicate.

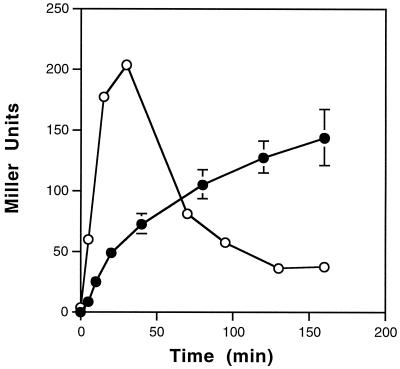

To examine the kinetics of induction from a temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoter, cultures were grown under repressing conditions and then induced at the elevated temperature (Fig. 3). At the indicated times, cultures were harvested and β-Gal activity was determined. For S. flexneri, activity ranged from 0.6 Miller units under repressing conditions to 144 Miller units after 160 min under inducing conditions, which represented a 240-fold induction of β-Gal activity. In contrast, maximal induced activity was achieved after 30 min for K. pneumoniae, which corresponded to a 50-fold induction. This level of regulation is comparable to that achieved with the commonly used Ptac promoter in E. coli (9). Intriguingly, incubation for longer time periods at the induced temperature resulted in a dramatic decrease in β-Gal activity, which may be due to the instability of LacZ at elevated temperatures. Alternatively, the rapid decrease in activity may be a reflection of the detrimental effects of the elevated temperature on the cells' physiology. However, because the cells were growing rapidly (data not shown), we consider this unlikely.

FIG. 3.

Time course analysis of the temperature induction of LacZ expression. Overnight cultures of S. flexneri (●) and K. pneumoniae (○) carrying the Pro1 C1∗ reporter constructs (the asterisk indicates that the Pro4 promoter drives c1) were diluted 1:100 and grown in LB medium at 31°C to early log phase. Aliquots of the culture were then incubated at 42°C for the indicated times in a staggered fashion so that the OD600 at the time of harvesting for β-Gal assays was approximately 0.6. Values reported (± standard deviations) are averages of results for duplicate cultures assayed in triplicate.

In summary, the temperature-sensitive C1-regulated promoter system exhibited very low basal expression, with the ratio of induction to repression being up to 240-fold for S. flexneri and up to 50-fold for K. pneumoniae. Therefore, the results indicated the usefulness of the expression systems in S. flexneri and K. pneumoniae and will provide a new opportunity for controlled gene expression in enteric gram-negative bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Hexal Gentech ForschungsGmbH.

DNA sequencing data were obtained by the Biotechnology Resource Laboratory of the Medical University of South Carolina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson D W K, Keusch G T. Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. In: Blaser M J, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrent R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press Ltd.; 1995. pp. 763–784. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backman K, Ptashne M. Maximising gene expression on a plasmid using recombination in vitro. Cell. 1978;13:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumstark B R, Stovall S R, Bralley P. The ImmC region of phage P1 codes for a gene whose product promotes lytic growth. Virology. 1990;179:217–227. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Samoun K, Leblon G, Reyes O. Positively regulated expression of the Escherichia coli araBAD promoter in Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J, Ullrich A, Raker M A, Gray A, Dull T J, Gutell R R, Noller H F. Construction and fine mapping of recombinant plasmids containing the rrnB ribosomal RNA operon of E. coli. Plasmid. 1981;6:112–118. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunschwig E, Darzins A. A two-component T7 system for the overexpression of genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1992;111:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90600-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citron M, Velleman M, Schuster H. Three additional operators, Op21, Op68, and Op88, of bacteriophage P1. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3611–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliason J L, Sternberg N. Characterization of the binding sites of c1 repressor of bacteriophage P1. Evidence for multiple asymmetric sites. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:281–293. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman L, Belin D, Carson M J, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinrich J, Velleman M, Schuster H. The tripartite immunity system for phages P1 and P7. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzel T, Velleman M, Schuster H. ban operon of bacteriophage P1. Mutational analysis of the c1 repressor-controlled operator. J Mol Biol. 1989;205:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinzel T, Velleman M, Schuster H. The c1 repressor inactivator protein coi of bacteriophage P1. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17928–17934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinzel T, Velleman M, Schuster H. C1 repressor of phage P1 is inactivated by noncovalent binding of P1 Coi protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4183–4188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleiner D, Paul W, Merrick M J. Construction of multicopy expression vectors for regulated over-production of proteins in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other enteric bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1779–1784. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lederberg E M, Cohen S N. Transformation of Salmonella typhimurium by plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1974;119:1072–1074. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.1072-1074.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehnherr H, Velleman M, Guidolin A, Arber W. Bacteriophage P1 gene 10 is expressed from a promoter-operator sequence controlled by C1 and Bof proteins. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6138–6144. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6138-6144.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehnherr H, Jensen C D, Stenholm A R, Dueholm A. Dual regulatory control of a particle maturation function of bacteriophage P1. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4105–4109. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4105-4109.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz R, Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrick M J, Gibbens J R, Postgate J R. A rapid and efficient method for plasmid transformation of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:2053–2057. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-8-2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murooka Y, Harada T. Expansion of the host range of coliphage P1 and gene transfer from enteric bacteria to other gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;38:754–757. doi: 10.1128/aem.38.4.754-757.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman J R, Fuqua C. Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the l-arabinose-inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene. 1999;227:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podschun R, Ullmann U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:589–603. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remaut E, Stanssens P, Fiers W. Plasmid vectors for high-efficiency expression controlled by the pL promoter of coliphage lambda. Gene. 1981;15:81–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosner J L. Formation, induction, and curing of bacteriophage P1 lysogens. Virology. 1972;49:679–689. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaefer T S, Hays J B. Bacteriophage P1 bof protein is an indirect positive effector of transcription of the phage bac-1 ban gene in some circumstances and a direct negative effector in other circumstances. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6469–6474. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6469-6474.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukchawalit R, Vattanaviboon P, Sallabhan R, Mongkolsuk S. Construction and characterization of regulated l-arabinose-inducible broad host range expression vectors in Xanthomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;181:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Velleman M, Dreiseikelmann B, Schuster H. Multiple repressor binding sites in the genome of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5570–5574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright J J, Kumar A, Haywood R S. Hypersymmetry in a transcriptional terminator of Escherichia coli confers increased efficiency as well as bidirectionality. EMBO J. 1992;11:1957–1964. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarmolinsky M B, Sternberg N. Bacteriophage P1. In: Calender R, editor. The bacteriophages. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1988. pp. 291–438. [Google Scholar]