Abstract

In this study the essential oils obtained from four different plant species belonging to the Lamiaceae family were extracted by means of hydrodistillation and their composition and antimicrobial activity were evaluated. About 66 components were identified by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), and among all, thymol (67.7%), oleic acid (0.5–62.1%), (−)-caryophyllene oxide (0.4–24.8%), α-pinene (1.1–19.4%), 1,8-cineole (0.2–15.4%), palmitic acid (0.32–13.28%), ( +)spathulenol (11.16%), and germacrene D (0.3–10.3%) were the most abundant in all the species tested (i.e. Thymus daenensis, Nepeta sessilifolia, Hymenocrater incanus, and Stachys inflata). In particular, only the composition of essential oils from H. incanus was completely detected (99.13%), while that of the others was only partially detected. Oxygenated monoterpenes (75.57%) were the main compounds of essential oil from T. daenensis; sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons (26.88%) were the most abundant in S. inflata; oxygenated sesquiterpenes (41.22%) were mainly detected in H. incanus essential oil, while the essential oil from N. sessilifolia was mainly composed of non-terpene and fatty acids (77.18%). Due to their slightly different composition, also the antibacterial activity was affected by the essential oil tested. Indeed, the highest antibacterial and antifungal activities were obtained with the essential oil from T. daenensis by means of the inhibition halo (39 ± 1 and 25 ± 0 mm) against Gram-positive strains such as Staphylococcus aureus and Aspergillus brasiliensis. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal/fungicidal concentration (MBC/MFC) of the essential oils obtained from the four species varied from 16 to 2000 μg/mL and were strictly affected by the type of microorganism tested. As an example, the essential oils from H. incanus and S. inflata were the most effective against the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MIC 16 and 63 μg/ml, respectively), which is considered one of the most resistant bacterial strain. Therefore, the essential oils obtained from the four species contained a suitable phytocomplexes with potential applications in different commercial area such as agriculture, food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries. Moreover, these essential oils can be considered a valuable natural alternative to some synthetic antibiotics, thanks to their ability to control the growth of different bacteria and fungi.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Bioinorganic chemistry

Introduction

An increased interest in finding new and safe antimicrobial molecules from natural origin, especially from plants, has been detected in the last decades1,2. To this purpose the scientific community has focused its attention on natural, safe and effective antimicrobial molecules. In particular, essential oils have been traditionally used for their antimicrobial effects as topical or systemic drugs for bacterial and fungal infections, as preservative in food and topical ointments, as natural as biocide in ecological agriculture. The different molecules contained in the essential oils can exsert a synergistic effect provide a protection higher than that achieved by single molecules also reducing the multidrug resistance, which occurs in different infections and and inhibiting the contamination by foodborne pathogens3–5.

Essential oils obtained from Lamiaceae have gained considerable interest since their rich content in biological active molecules especially volatile molecules, such as monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and coumarins in some cases5,6. The antifungal and antimicrobial effect of several essential oils from this family, like thyme, peppermint, lavender, rosemary, peppermint, savory and marjoram, has been previous demonstrated7,8. The essential oil obtained from Thymus daenensis Čelak., endemic in NE Iraq and Iran, contains thymol, carvacrol, and p-cymene in high amount9–15. Thymol and β-caryophyllene, being the main components of T. daenensis essential oil, seem to be responsible of its antifungal and antibacterial effects10,16–19. As a function of its composition and origin, the essential oils of T. daenensis have been used to treat asthma, recurrent dry cough, and bronchitis as well as food ingredient12,20. The antimicrobial activity of some Nepeta species has been studied as well21–23. The essential oil from Nepeta sessilifolia Bunge, endemic in Iran and Pakistan, was especially effective against Candida albicans. β-caryophyllene and 1,8-cineole, α-pinene, β-pinene, trans-β-ocimene, germacrene-D, and caryophyllene oxide are the major constituents of the essential oil of Hymenocrater incanus Bunge an exclusive species of this genus in Iran24. Recent studies confirmed the potential of the secondary metabolites from this genus as antimicrobial antifungal, antiparasitic25–27. Germacrene-D, bicyclogermacrene, and α-pinene are the main components contained in the essential of Stachys inflata Benth., native from NE Turkey to Iran, which have antimicrobial effect, especially against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa28–32.

The recent interest of consumers in food preservatives of natural origin has shifted the research interest towards the possible application of the essential oils to this propose. Several in vitro studies have established the efficacy of essential oils from Lamiaceae family taxa against common foodborne pathogens such as Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella ser. Enteritidis, Salmonella ser. Typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus.

Overall results disclosed that the cultivation region can strongly affect the composition and consequently the effectiveness of essential oils from Lamiaceae and their selectivity against different pathogens. Given that, it is important to simultaneously compare the efficacy of essential oils obtained from different species also testing different pathogens.

Accordingly, in this study, the essential oils from four different species of Lamiaceae were extracted and characterized and their efficacy was tested simultaneously using 12 strains of microorganisms.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Aerial parts of T. daenensis, N. sessilifolia, H. incanus, and S. inflata, were collected from the Daran region, located in Isfahan province of Iran (longitude: 46˚49ʹ02ʺ and latitude: 36˚54ʹ170ʺ). Permission for collection of plant materials obtained from the Agricultural Jahad Office and also the owner of the farm. The study is in compliance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The harvested specimens were transferred to the laboratory and exposed to free air in shade to dry. One sample of each whole plant was collected and pressed. The plant was identified and recorded at the herbarium of the University of Kashan. The plant was identified and recorded with code number 1018, 1019, 1020, 1021.

Extraction of essential oils

After complete drying, the samples were grinded to obtain small particles and ensure the complete extraction of the bioactives; 100 g of each sample was subjected to extraction by means of hydrodistillation using a Clevenger apparatus for 5 h. The weight of essential oils collected after sodium sulphate dehydration was calculated accurately and essential oils was stored in closed bottles at 4 °C in the dark until further use59,60.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

The determination of the constituents of essential oil samples has been performed by means of GC–MS method. A chromatograph (Model 6890) Coupled with an N-5973 mass spectrometer made in USA and a HP-5MS Capillary Column with 5% methylphenylsiloxane static phase (Length 30 m, Internal Diameter 0.25 mm, Layer Static Thickness 0.25 μm) and ionization energy of 70 eV has been used for qualitative identification of the components. A temperature gradient has been used for the analysis, starting from 60 °C and then increasing the temperature (at a rate of 3 °C/min) up to 246 °C. The injector and detector temperature were set at 250 °C, the injection volume was 1 µl with 1.50 split and the helium carrier gas delivered at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. The chemical components of the essential oils were identified as a function of the retention indices about standards of n-alkane mixtures (C8–C20) and mass spectral data of each peak using a computer library (Wiley-14 and NIST-14 Mass Spectral Library) and comparing these data with those reported in the literature33.

Antimicrobial activity

Tested microorganisms

Twelve microorganisms were used to evaluate the antimicrobial activity of the selected essential oils. Microbial strains were provided by the Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology (IROST, CITY, Iran). Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 12228), S. aureus (ATCC 29737) and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) were chosen as Gram-positive bacteria, while Klebsiella pneumonia (ATCC 10031), Shigella dysenteriae (PTCC 1188), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), Salmonella paratyphi-A serotype (ATCC 5702), Proteus vulgaris (PTCC 1182) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 10536) were the Gram-negative bacteria selected. Aspergillus niger (ATCC 16404), Aspergillus brasiliensis (PTCC 5011) and Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) were the fungal strains tested.

Agar diffusion method

Well plates 6.0 mm in diameter containing Müller Hinton agar were prepared, and 100 µL of bacterial suspensions with a half-McFarland turbidity equivalent in culture medium were cultured. The essential oil (30 mg/mL) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and 10 μL (equivalent to 300 μg) of each essential oil was poured into the wells. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and their antimicrobial activity was measured for each microorganism measuring, by the antibiogram ruler (in millimetres), the diameter of inhibition halos. Three replicates were performed for each strain and results were calculated as mean ± standard deviation. DMSO was used as negative control and gentamicin and rifampin for bacteria, and nystatin for fungi, were used to compare their antimicrobial power with those of the essential oils61.

MIC evaluation

The minimum concentration capable of inhibiting the growth of the bacteria or fungi (MIC) was calculated by microdilution method. The essential oils were dissolved in a mixture of TSB medium and DMSO at an initial concentration of 2000 μg/mL. The stock solutions were diluted to reach the following concentrations: 1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5, 31.25 and 15.63 µg/mL. Experiments were performed by using 96-well microplates. 95 µL of culture medium, 5 µl of bacterial suspension with 0.5 McFarland dilution, and 100 µL of essential oil dilutions were added to each well, and then the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacterial strains and 48 h and 72 h at 30 °C for yeast61. The MIC was determined by the improvement of opacity or the change in colour as the lowest concentration that inhibited the visible growth (absence of turbidity).

Determination of minimum bactericide/fungicidal concentration (MBC/MFC)

To determine the minimum concentration capable of killing the bacterial or fungal strains, the same microdilution method was used. After 24 h of incubation of bacteria with the essential oils at different concentrations, 5 µL of the content of each well were inoculated with neutrin agar medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacterial strains and 48 h and 72 h at 30 °C for yeasts. After incubation, the colony-forming units (CFUs) were enumerated61. The MBC/MFC was the lowest concentration able to effectively reduce the growth of microorganisms (99.5%).

Statistical analysis of data

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple comparisons of means, and the Tukey’s test and Student’s t-test were performed to substantiate differences between groups using XL Statistics for Windows. The differences were considered statistically significant for p < 0.05.

Results

Composition of essential oils

The different essential oils were obtained from the four different Lamiaceae species from Iran. Their colour varied from pale yellow to dark yellow and the yield was 1.88% from T. daenensis, 0.2% from N. sessilifolia, 0.02% from H. incanus, and 0.14% from S. inflata.

GC–MS analysis

The chemical composition of the essential oils was investigated using a GC–MS. About 51 components were identified. The composition of essential oils from H. incanus was completely detected (99.13%), while that of T. daenensis (97.44%), S. inflata (95.77%), and N. sessilifolia (84.56%), was only partially detected (Table 1). The main compounds of essential oil from T. daenensis were oxygenated monoterpenes (75.57%), from S. inflata were sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons (26.88%) and from H. incanus were oxygenated sesquiterpenes (41.22%). Differently, the essential oil from N. sessilifolia was mainly composed of non-terpene and fatty acids (77.18%).

Table 1.

Main components and retention indice (RI) detected in the essential oils from Thymus daenensis (TD), Nepeta sessilifolia (NS), Hymenocrater incanus (HI), and Stachys inflata (SI).

| No | Compound (%) | RI | TD | NS | HI | SI | Molecular formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Thujene | 864 | 0.85 | 0.39 | – | – | C10H16 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 871 | 1.09 | – | – | 1.52 | C10H16 |

| 3 | Camphene | 888 | 0.82 | – | – | 0.55 | C10H16 |

| 4 | Sabinene | 908 | – | 0.33 | – | – | C10H16 |

| 5 | β -pinene | 912 | 0.43 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 6 | β -Myrcene | 921 | 1.50 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 7 | α-Phellandrene | 933 | 0.28 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 8 | α-Terpinene | 943 | 1.71 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 9 | p-Cymene | 953 | 5.16 | – | – | – | C10H14 |

| 10 | 1,8-Cineole | 957 | 3.52 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 1.65 | C10H18O |

| 11 | γ-Terpinene | 980 | 6.20 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 12 | α-Terpinolene | 1002 | 0.26 | – | – | – | C10H16 |

| 13 | Linalool | 1013 | 0.67 | 1.45 | – | 1.20 | C10H18O |

| 14 | Camphor | 1044 | – | – | 1.67 | C10H16O | |

| 15 | Borneol | 1064 | 3.67 | – | 1.17 | C10H18O | |

| 16 | α-Terpineol | 1080 | – | 0.50 | 0.91 | C10H18O | |

| 17 | Verbenone | 1093 | 2.20 | C10H14O | |||

| 18 | Thymol | 1170 | 67.71 | C10H14O | |||

| 19 | Acetic acid, bornyl ester | 1129 | 1.29 | C12H20O2 | |||

| 20 | α-Copaene | 1191 | 0.69 | C15H24 | |||

| 21 | β- Bourbonene | 1197 | – | 1.03 | – | C15H24 | |

| 22 | β-Elemene | 1201 | – | – | 1.12 | C15H24 | |

| 23 | trans-Caryophyllene | 1224 | 2.99 | 0.67 | 3.68 | – | C15H24 |

| 24 | ( +)-Aromadendrene | 1232 | 0.15 | – | – | – | C15H24 |

| 25 | α-Humulene | 1239 | – | – | 1.50 | – | C15H24 |

| 26 | Alloaromadendrene | 1242 | – | 0.29 | – | C15H24 | |

| 27 | α-Amorphene | 1251 | – | – | 0.92 | C15H24 | |

| 28 | β-Cubebene | 1254 | – | 0.26 | – | – | C15H24 |

| 29 | Germacrene D | 1255 | – | – | 0.30 | 10.26 | C15H24 |

| 30 | Bicyclogermacrene | 1263 | – | – | 0.57 | 9.19 | C15H24 |

| 31 | β -Bisabolene | 1268 | 0.50 | – | – | – | C15H24 |

| 32 | δ-cadinene | 1277 | – | 0.34 | – | 4.7 | C15H24 |

| 33 | cis-α-Bisabolene | 1286 | 0.40 | – | – | – | C15H24 |

| 34 | Elemol | 1296 | – | 0.24 | – | – | C15H26O |

| 43 | ( +) spathulenol | 1314 | – | – | 11.16 | C15H24O | |

| 35 | (−)-Caryophyllene oxide | 1315 | 0.41 | 1.26 | 24.81 | – | C15H24O |

| 36 | Viridiflorol | 1321 | – | – | 2.26 | C15H26O | |

| 37 | (−)-Humulene epoxide II | 1330 | – | – | 3.69 | – | C15H24O |

| 38 | α-Chamigrene | 1347 | – | 2.37 | – | C15H24 | |

| 39 | α-Cadinol | 1356 | – | 7.66 | 3.25 | C15H26O | |

| 40 | Caryophyllenol-II | 1367 | – | 5.06 | – | C15H24O | |

| 41 | (3S,4R,5S,6R,7S)-aristol-9-en-3-ol | 1374 | – | 1.51 | C15H24O | ||

| 42 | Myristic acid | 1414 | – | 1.31 | – | C14H28O2 | |

| 43 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | 1445 | – | 1.39 | 0.89 | C18H36O | |

| 44 | Phthalic acid | 1462 | – | 0.55 | – | C8H6O4 | |

| 45 | Tridecane | 1478 | – | 0.42 | 0.45 | C13H28 | |

| 46 | Hexadecanoic acid = palmitic acid | 1515 | – | 13.28 | 12.10 | C16H32O2 | |

| 47 | Phytol | 1580 | – | 9.22 | 2.14 | C20H40O | |

| 48 | Oleic acid | 1600 | 0.49 | 62.09 | 23.53 | 20.75 | C18H34O2 |

| 49 | Stearic acid | 1627 | – | 8.16 | – | 3.89 | C18H36O2 |

| 50 | Linoleic acid | 1633 | – | 6.06 | – | – | C18H32O2 |

| 51 | Lauric acid | 1692 | – | 0.87 | – | – | C12H24O2 |

| Total | 95.77 | 84.56 | 99.13 | 97.44 | |||

| Monoterpenes hydrocarbons | 18.26 | 0.72 | 0 | 2.07 | |||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 75.57 | 2.86 | 0.22 | 8.8 | |||

| Sesquiterpenes hydrocarbons | 4.04 | 2.3 | 8.71 | 26.88 | |||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 0.41 | 1.5 | 41.22 | 18.18 | |||

| Others | 0.49 | 77.18 | 48.98 | 41.55 |

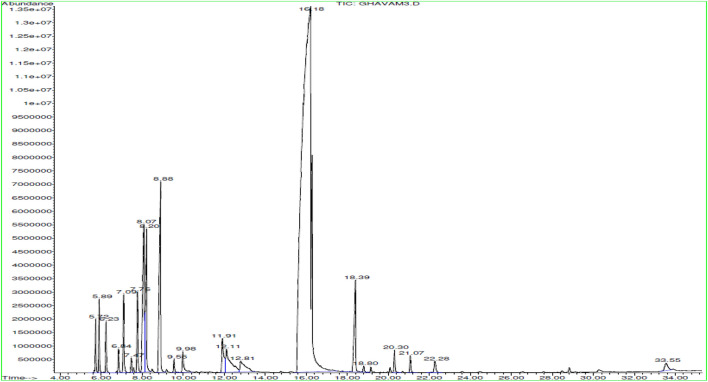

The essential oil from T. daenensis was also rich in monoterpenes hydrocarbons (18.3%), and its main components were thymol (67.71%), γ-terpinene (6.20%), p-cymene (5.16%) and borneol (3.67%), and 1,8-cineole (15%) (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

GC–MS chromatogram of essential oil obtained from Thymus daenensis.

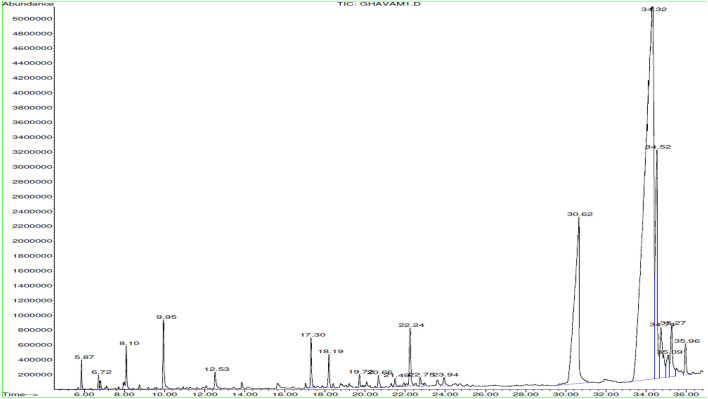

Fatty acids and non-terpenes are the main components of essential oil from N. sessilifolia (Table 1 and Fig. 2). In particular, oleic acid (62.09%), stearic acid (8.16%) and linoleic acid (6.06%) were detected for the first time in this oil.

Figure 2.

GC–MS chromatogram of essential oil obtained from Nepeta sessilifolia.

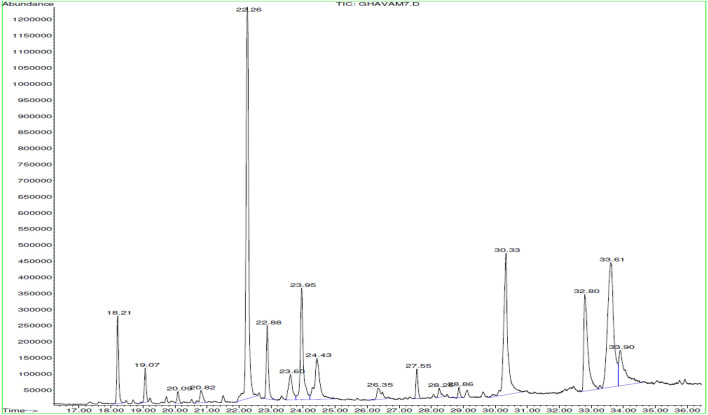

Essential oil obtained from H. incanus was rich in fatty acids (50.65%) and oxygenated sesquiterpenes (41.22%). In particular, (−)-caryophyllene oxide (24.81%), oleic acid (23.53%), palmitic acid (28.23%), phytol (9.22%), α-cadinol (7.66%), and caryophyllenol-II were found (5.06%) (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

GC–MS chromatogram of essential oil obtained from Hymenocrater incanus.

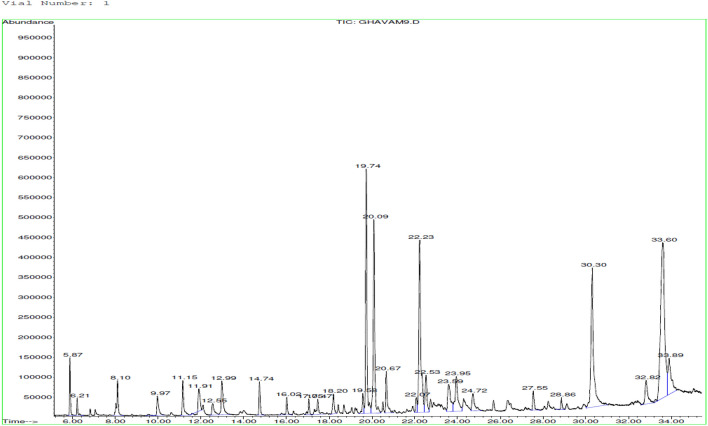

Acids (42.22%) and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (26.25%), were the major constituents of the essential oil from S. inflata. Especially, oleic acid (20.75%), palmitic acid (12.12%), ( +)spathulenol (11.16%), germacrene D (12.26%), and bicyclogermacrene (9.9%) were detected (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

GC–MS chromatogram of essential oil obtained from Stachys inflata.

Overall data underlined that 1,8-cineole and oleic acid were commonly present in the essential oils of T. daenensis, N. sessilifolia, H. incanus, and S. inflata. The highest amount of 1,8-cineole was found in the oil from T. daenensis (3.52%) and the lowest in essential oil from H. incanus (0.22%). The highest amount of oleic acid was detected in the oil from N. sessilifolia (62.09%) while the lowest in that from T. daenensis (0.49%). Linalool was found in all essential oils except in that from H. incanus. Trans-Caryophyllene and (−)-Caryophyllene oxide were found in all essential oils except in that from S. inflata and the highest amount (3.68% and 24.81%) was found in oil from H. incanus. Thymol (67.71) and p-cymene (5.16) were contained only in the oil from T. daenensis; linoleic acid (6.06) and S. inflata; caryophyllenol-II (5.06) in the oil from H. incanus, ( +) spathulenol (11.16) and in the oil from S. inflata.

Antimicrobial activity

Inhibition halos

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of the essential oils were measured to evaluate their potential applications (Table 2). The highest inhibition halo diameter (39 ± 1 mm) was obtained treating S. aureus with essential oil from T. daenensis, and it was even higher than that obtained by using rifampin (21 ± 0 mm) and gentamicin (27 ± 0 mm). Essential oil from N. sessilifolia (10 ± 1 mm) and S. inflata (9 ± 1 mm) had a significantly lower activity against this bacterium, while oil from H. incanus did not show any activity.

Table 2.

Inhibition-zone diameters provided by antibiotics (used as references) and the essential oils from Thymus daenensis (TD), Nepeta sessilifolia (NS), Hymenocrater incanus (HI), and Stachys inflata (SI).

| Test microorganisms | IZ (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oils | Antibiotics | ||||||

| TD | NS | HI | SI | Rifampin | Gentamicin | Nystatin | |

| Sh. dysenteriae | *16 | ND | ND | ND | 9 | 17 | NA |

| P. aeruginosa | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 20 .00 | NA |

| B. subtilis | *♪ 14 | *♪9 | *♪10 | *♪9 | 19 | 30 | NA |

| S. epidermidis | *♪9 | *♪9 | *♪11 | ND | 44 | 39 | NA |

| E. coli | ♪11 | ND | ND | ND | 10 | 23 | NA |

| S. aureus | *♪39 | *♪10 | ND | *♪9 | 21 | 27 | NA |

| K. pneumonia | *18 | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 17 | NA |

| P. vulgaris | *♪14 | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 24 | NA |

| S. paratyphi-A | *♪12 | ND | ND | ND | 8 | 18 | NA |

| C. albicans | Ω 12 | ND | ND | ND | NA | NA | 33 |

| A. sniger | Ω 12 | ND | ND | ND | NA | NA | 27 |

| A. brasiliensis | Ω 25 | ND | ND | ND | NA | NA | 30 |

Mean values ± standard deviations of three cultures were reported.

NA no activity, ND not determined.

Symbols (*) indicate values statistically different from rifampin, symbols (♪) indicate values statistically different from gentamicin and symbols (Ω) indicate values statistically different from nystatin (p < 0.05).

Essential oil from T. daenensis was also effective against A. brasiliensis (25 ± 0 mm), and its activity was similar to that of nystatin (30 ± 0 mm), used as control. Moreover, oil from T. daenensis was capable of inhibiting the growth of A. sniger (12 ± 0 mm) and C. albicans (12 ± 1 mm) but in a lesser extent than nystatin (27 ± 0 and 33 ± 0 mm).

Essential oil from T. daenensis was also effective in counteracting two Gram-negative bacteria K. pneumonia (18 ± 1 mm) mm and Sh. dysenteriae (16 ± 0 mm) as the inhibition halos were larger than those obtained treating the same bacteria with rifampin (8 ± 0 mm and 9 ± 0 mm) and gentamicin (17 ± 0 mm). The oil was also effective against two more Gram-negative bacteria E. coli and S. paratyphi-A, being the inhibition halo 11 ± 1 and 12 ± 1 mm, which was slightly larger than that obtained by using rifampin (10 ± 0 and 8 ± 0 mm) and lower than that exerted by gentamicin (23 ± 0 and 18 ± 0 mm). It was also slightly effective against the Gram-positive S. epidermidis (9 ± 0), but any effect was detected against S. paratyphi-A, S. epidermidis, and P. aeruginosa.

Essential oil from N. sessilifolia was less effective than the essential oil obtained from T. daenensis as it inhibited the growth of only three Gram-positive bacteria: B. subtilis (14 ± 1 mm), S. epidermidis (9 ± 0 mm), and S. aureus (10 ± 1 mm). The efficacy of this oil was also lower than that obtained by using rifampin and gentamicin.

Essential oil from H. incanus inhibited only B. subtilis (10 ± 0) and S. epidermidis (11 ± 0 mm) in the less extend than rifampin and gentamicin. Essential oil from S. inflata had a weak activity against Gram-positive bacteria like B. subtilis (9 ± 0 mm) and S. aureus (9 ± 1 mm).

Measurament of MIC and MBC/MFC

The MIC of the essential oils varied from > 16 μg/mL to > 2000 μg/mL as a function of the microorganism and oil used (Table 3). The MIC (16 μg/mL) obtained treating the Gram-negative P. aeruginosa with essential oil from S. inflata were lower than that obtained using rifampin (31 μg/mL), but it was significantly higher than that obtained using gentamicin (8 µg/mL). The other essential oils had higher MIC (125 µg/mL) against this bacterium. The MIC of all the used oils (except that from T. daenensis) against A. brasiliensis and A. niger were around 2000 µg/mL, disclosing their inactivity and essential oil from S. inflata was not effective also against S. aureus (MIC > 1000 μg/mL).

Table 3.

MIC obtained using antibiotics (used as references) and the essential oils from Thymus daenensis (TD), Nepeta sessilifolia (NS), Hymenocrater incanus (HI), and Stachys inflata (SI).

| Microorganisms | MIC (μg/mL) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oils | Antibiotics | ||||||

| TD | NS | HI | SI | Rifampin | Gentamicin | Nystatin | |

| Sh. dysenteriae | *♪ 500 | *♪ 125 | *♪ 63 | *♪ 125 | 16 | 4 | NA |

| P. aeruginosa | *♪ 125 | *♪ 125 | *♪ 16 | *♪ 16 | 31 | 8 | NA |

| B. subtilis | *♪ 125 | *♪ 250 | *♪ 500 | *♪ 125 | 31 | 4 | NA |

| S. epidermidis | *♪ 125 | *♪ 250 | *♪ 500 | *♪ 500 | 2 | 2 | NA |

| E. coli | *♪ 125 | *♪ 500 | *♪ 250 | *♪ 125 | 16 | 31 | NA |

| S. aureus | *♪ 125 | *♪ 500 | *♪ 500 | *♪ > 1000 | 31 | 2 | NA |

| K. pneumonia | *♪ 125 | *♪ 125 | *♪ 63 | *♪ 125 | 16 | 4 | NA |

| P. vulgaris | *♪ 250 | *♪ 250 | *♪ 500 | *♪ 250 | 16 | 16 | NA |

| S. paratyphi-A | *♪ 125 | *♪ 250 | *♪ 63 | *♪ 125 | 16 | 4 | NA |

| C. albicans | Ω 31 | Ω 250 | Ω 63 | Ω 500 | NA | NA | 125 |

| A. sniger | Ω 250 | Ω 2000 | Ω > 2000 | Ω > 2000 | NA | NA | 31 |

| A. brasiliensis | Ω 250 b | Ω 2000 a | Ω > 2000 | Ω > 2000 | NA | NA | 31 |

Symbols (*) indicate values statistically different from rifampin, symbols (♪) indicate values statistically different from gentamicin and symbols (Ω) indicate values statistically different from nystatin (p < 0.05).

The MIC obtained treating the different bacteria with the oil from T. daenensis varied between 125 and 500 μg/mL, with its weakest inhibitory effect against Sh. dysenteriae. The antifungal activity of oil from T. daenensis was slightly higher (MIC from 31 to 250 μg/mL) and it especially inhibited C. albicans as its power was three times higher than that of nystatin (125 μg/mL).

The MBCs/MFCs obtained treating the different bacterial and fungal strains with oil from T. daenensis varied from 63 to 500 µg/mL (Table 4), the obtained MBCs/MFCs, irrespective of the microorganism tested, except S. aureus, K. pneumonia and C. albicans, were equal to the MICs (Table 3) indicating the capability of this oil of inhibiting the growth and killing the bacteria at the same concentration.

Table 4.

MBC obtained using the essential oils from Thymus daenensis (TD), Nepeta sessilifolia (NS), Hymenocrater incanus (HI), and Stachys inflata (SI).

| Test microorganisms | MBC (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oils | ||||

| TD | NS | HI | SI | |

| Sh. Dysenteriae | 500 | 1000 | *63 | 1000 |

| P. aeruginosa | 125 | 125 | *16 | 250 |

| B. subtilis | *125 | > 1000 | 500 | 250 |

| S. epidermidis | *125 | 250 | 500 | 500 |

| E. coli | *125 | 500 | 250 | 500 |

| S. aureus | 500 | 1000 | 500 | > 1000 |

| K. pneumonia | 250 | 125 | *63 | 1000 |

| P. vulgaris | *250 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| S. paratyphi-A | 125 | 250 | *63 | 500 |

| C. albicans | *63 | 250 | 250 | 1000 |

| A. sniger | *250 | 2000 | > 2000 | > 2000 |

| A. brasiliensis | *250 | 2000 | > 2000 | > 2000 |

Symbols (*) indicate values statistically different from the others essential oils against the same bacterial/fungal strain (p < 0.05).

The MICs obtained by treating all microorganisms with essential oil from N. sessilifolia varied between 125 and 2000 μg/mL. The strongest effect was obtained against the Gram-negative Sh. dysenteriae, K. pneumonia and P. aeruginosa, but the found MICs were four times weaker than that provided by the antibiotics used as control. The lowest effect of this oil was against A. niger and A. brasiliensis. As reported for oil from T. daenensis, MBCs obtained treating the bacteria with oil from N. sessilifolia were always equal to MICs for all microorganisms tested (except S. aureus, B. subtilis, Sh. dysenteriae, and P. vulgaris). The lowest MBC of the essential oil from N. sessilifolia was obtained against Sh. dysenteriae and K. pneumonia, confirming its ability to inhibit and kill them. The low efficacy and high MICs and MBCs of essential oil from N. sessilifolia against most of the bacterial strains tested in this work, should be connected with the absence of terpenes (which are considered the most effective against bacteria). The antimicrobial power against few bacterial strains should be related to the fatty acid content, even if the mechanism of action of these compounds is still completely unknown and they are supposed to modify the permeability of the membrane and promote its disruption, thus causing significant alterations on the membrane-dependent conduction systems.

The MIC values obtained treating the different microorganisms with oil from H. incanus varied between > 16 and > 2000 µg/mL. The strongest activity was found against the Gram-negative P. aeruginosa (MIC 63 μg/mL). The MIC of this oil against C. albicans was (63 µg/mL) lower than that of nystatin (MIC 125 µg/mL) while the MFC was significantly higher (250 µg/mL). Treating the other microorganisms, MBCs/MFCs were always equal to MICs and oxygenated sesquiterpenes such as (−)-caryophyllene oxide and α-cadinol contained can be responsible of these activities.

The MICs essential oil from S. inflata against the tested microorganisms varied between > 16 and > 2000 μg/mL. The strongest effect was found against the Gram-negative P. aeruginosa, being the MIC very low (16 μg/mL).

Discussion

In previous studies, the yield of essential oil collected from T. daenensis was 2.09%15, from N. sessilifolia was 0.56%34, from H. incanus was 0.6%24, and from S. inflata was 2.9%31. Then the yields were always higher probably because the used plants were grown in different areas where the environmental factors can strongly affect the content of secondary metabolites35.

The obtained results were in line with those reported previously, as thymol was always the main component, and the highest amount (91.15%) has been detected with T. daenensis from the Kurdistan region of Iran14. Due to the high content of thymol, T. daenensis can be considered as the main source of this valuable compound, which is the phenolic compounds with remarkable antimicrobial properties36–38.

Differently,34,39,40, reported that oxygenated sesquiterpene (35.3% and 33.14%) and oxygenated monoterpene (49%) were the main components of this essential oil obtained from plants collected in Ghamshelo and Arak, Iran. Hence, the high content of acids is a unique characteristic of the plants harvested from Isfahan province of Iran and can be strongly affected by the location, climatic and ecological conditions, field operations, growth stage, and genetic traits41. Thanks to its acid content, the essential oil from N. sessilifolia can exert several beneficial activities. Indeed, oleic Acid (9-Octadecenoic acid) is a component of omega-9 fatty acids, capable of counteracting cancer and cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune diseases, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, inflammatory diseases and hypertension42–44. Linoleic acid is one of the most unsaturated fatty acids of the human diet except for omega-6 fatty acids and has an active role in human growth and general health42.

This result is not completely in agreement with those of24 because only some compounds were similar but the most were different and none of the major constituents found in this essential oil was recorded by24. These results confirmed that environmental and climate conditions have a significant impact on the chemotypic properties of the obtained oil45. Caryophyllene oxide, which is contained in high amount in the oil from H. incanus collected in the Isfahan province of Iran, can inhibit the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the intercellular space of body tissues and it has been used as antitumor agent46.

In none of the previous studies, oleic acid has been reported as main component of the essential oil obtained from S. inflata, while palmitic acid (9.1%) has been indicated as the most abundant bioactive of the essential oil obtained from this plant by28. Germacrene D and bicyclogermacrene were found by other authors but in different amount: 8.9% and 5.1%28, 16.9% and 16.6%29, and 32.9% and 7.3%30. The differences found were mainly related to genetic or non-genetic variations connected with environmental differences such as soil chemical composition and physiographic factors.

These results perfectly fit with those reported by18, which found the same diameter of inhibition halo. The effective inhibition of the growth of S. aureus provided by this oil can be related to thymol content, which has antimicrobial properties. It is a phenol present in different essential oils with antibacterial activity thanks to its ability to improve the permeability of the membrane of the bacteria38,47.

All the other essential oils were not able to inhibit the growth of this fungal strain. Again, the antifungal activity of oil from T. daenensis may be related to the thymol, as it has good antifungal activity against a wide range of plant pathogenic fungi and food contaminants36,37. The mechanism of action of thymol has not been fully elucidated, but it is believed that it can damage the cell wall of the fungi or cause their cell wall to decay48.

According to these results,18 in their study, used the essential oil from the same plant (Daran, East of Esfahan province, Iran) and reported an effective inhibition of the growth of these two fungi while49, using the same oil, detected a good inhibition of C. albicans growth. Unfortunately, any essential oil obtained from the other species was capable of inhibiting the growth of these two fungal microorganisms.

To the best of our knowledge any activity against these two bacterial strains have been detected in previous studies. Further, the growth of B. subtilis and P. vulgaris was inhibited as well, even if in a lesser extent (14 ± 1 mm) than rifampin (19 ± 0 and 8 ± 0 mm) and gentamicin (30 ± 0 and 24 ± 0 mm) while18 found a remarkable effect of this oil against B. subtilis (43 ± 0 mm).

The efficacy of oil from T. daenensis against E. coli was confirmed by other researcher, even if the results were quite different and the diameter of inhibition halo varied from 7 to 44 mm49,50.

Differently,23 found a good activity against N. asterotricha, probably due to the presence of oleic acid, stearic acid, and linoleic acid, that have inhibitory activities against S. aureus and other microorganisms51–53. According to this, it has been previously reported that P. aeruginosa is highly sensitive to essential oils54.

Candida albicans is one of the most common pathogenic fungi capable of causing human infectious, which are often difficult to be threated because of the abuse of antibiotic occurred in the last decades55. The oil from T. daenensis represents a natural, promising alternative for the treatment of these infections and thymol seems to be the main responsible of its efficacy since its ability to penetrate the cell membrane and contribute to the clotting of cell contents56. The MFC of this oil against C. albicans (20 µg/mL) was also low and confirmed its effectiveness as antifungal agent49.

The strongest activity was found against the Gram-negative P. aeruginosa (MIC 63 μg/mL), according to the results obtained by other authors against H. calycinus, H. sessilifolius. Sh. dysenteriae, K. pneumonia, and S. paratyphi-A, even if rifampin was significantly more effective (MIC 16 μg/mL)57,58.

In previous studies any antimicrobial effect was detected using the same oil obtained from plants collected from Isfahan Province, Iran32. These results confirmed the influence of plant habitat and conditions on the composition and activity of the essential oils. The MBCs/MFCs of the essential oil from S. inflata were always higher than MICs, indicating that the ability to inhibit the growth of bacteria was higher than that of killing them.

Conclusion

In this study, for the first time, the essential oils obtained from T. daenensis, N. sessilifolia, H. incanus, and S. inflata growing in the Daran region of Isfahan (Iran), were obtained and their composition and antimicrobial activity were evaluated. The main common components were thymol, oleic acid, (−)-caryophyllene oxide, α-pinene, 1,8-cineole, palmitic acid, ( +)spathulenol, germacrene D, bicyclogermacrene, phytol, camphor, and borneol, 1,8-cineole and oleic acid, while others were randomly present as a function of the used plants. Essential oil from T. daenensis was the most active as it was able to inhibit the growth of different microorganisms, especially S. aureus and A. brasiliensis. Based on the MICs, the essential oils had low MICs and MBCs/MFCs and good effect on Sh. dysenteriae, P. aeruginosa, E. coli, K. pneumonia and C. albicans, then they can be used as natural and valid agents in agriculture, food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries for the treatment of microbial and fungal infections or contaminations.

Author contributions

M.G. was the supervisor, designer of the hypotheses, and responsible for all the steps (laboratory, statistical analysis, data analysis, etc.) and wrote the text of the article. G.B. identified and confirmed the study plants, wrote part of the text and did the revision and formatting of the work. I.C. and M.L.M. wrote the text and did the revision and formatting of the work. Also M.L.M. interpretated of part of data, substantively revised the text and edited English language.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stojanović-Radić Z, Pejčić M, Joković N, Jokanović M, Ivić M, Šojić B, Škaljac S, Stojanovic P, Mihajilov-Krstev T. Inhibition of Salmonella enteritidis growth and storage stability in chicken meat treated with basil and rosemary essential oils alone or in combination. Food Control. 2018;90:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitić ZS, Jovanović B, Jovanović S, Mihajilov-Krstev T, Stojanović-Radić ZZ, Cvetković VJ, Mitrović TL, Marin PD, Zlatković BK, Stojanović GS. Comparative study of the essential oils of four Pinus species: Chemical composition, antimicrobial and insect larvicidal activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018;111:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aelenei P, Rimbu CM, Guguianu E, Dimitriu G, Aprotosoaie AC, Brebu M, Horhogea CE, Miron A. Coriander essential oil and linalool-interactions with antibiotics against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;68:156–164. doi: 10.1111/lam.13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitsidi Brahim, M., Fadli, M., Hassani, L., Boulay, B., Markouk, M., Bekkouche, K., Abbad, A., Aitali, M., Larhsini, M. Chenopodium ambrosioides var. ambrosioides used in Moroccan traditional medicine can enhance the antimicrobial activity of conventional antibiotics. Ind. Crops Prod.71, 37–43 (2015).

- 5.El Asbahani A, Miladi K, Badri W, Sala M, Ait Addi EH, Casabianca H, El Mousadik A, Hartmann D, Jilale A, Renaud FN, Elaissari A. Essential oils: from extraction to encapsulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2015;483:220–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebadollahi A, Ziaee M, Palla F. Essential oils extracted from different species of the Lamiaceae plant family as prospective bioagents against several detrimental pests. Molecules. 2020;25:1556. doi: 10.3390/molecules25071556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mariotti M, Lombardini G, Rizzo S, Scarafile D, Modesto M, Truzzi E, Benvenuti S, Elmi A, Bertocchi M, Fiorentini L, Gambi L, Scozzoli M, Mattarelli P. Potential applications of essential oils for environmental sanitization and antimicrobial treatment of intensive livestock infections. Microorganisms. 2022;10:822. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10040822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chouhan S, Sharma K, Guleria S. Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils: Present status and future perspectives. Medicines (Basel) 2017;4:58. doi: 10.3390/medicines4030058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajjadi SE, Khatamsaz M. Composition of the essential oil of Thymus daenensis Čelak. ssp. lancifolius (Čelak.) Jalas. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003;15:34–35. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2003.9712257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Samani M, Hashemi M, Zeinali H. Salicylic acid affects growth, essential oil and chemical compositions of thyme (Thymus daenensis Čelak.) under reduced irrigation. Plant Growth Regul. 2014;72:289–301. doi: 10.1007/s10725-013-9860-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehran M, Hoseini H, Hatami A, Taghizade M, Safaie A. Investigation of components of seven species of thyme essential oils and comparison of their antioxidant properties. J. Med. Plants. 2016;58:134–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mashkani M, Larijani K, Mehrafarin A, Naghdi Badi H. Changes in the essential oil content and composition of Thymus daenensis Čelak. under different drying methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018;112:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Askari F, Sefidkon F. Essential oil composition of Thymus daenensis Čelak. from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bearing Plants. 2003;6:217–219. doi: 10.1080/0972-060X.2003.10643357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisany W, Jahanshir A, Saadi S, Somaieh H, Shima Y, Paul CS. Nano silver-encapsulation of Thymus daenensis and Anethum graveolens essential oils enhances antifungal potential against strawberry anthracnose. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019;141:111808. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tohidi B, Mehdi R, Ahmad A. Essential oil composition, total phenolic, flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activity of Thymus species collected from different regions of Iran. Food Chem. 2017;220:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safarpoor M, Ghaedi M, Asfaram A, Yousefi-Nejad M, Javadian H, Zare Khafri H, Bagherinasab M. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of antimicrobial compounds from Thymus daenensis and Silybum marianum: Antimicrobial activity with and without the presence of natural silver nanoparticles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.-Lahian, F., Garshasbi, M., Asiabar, Z., Dehkordi, N., Yazdinezhad, A., & Mirzaei, S.A. Ecotypic variations affected the biological effectiveness of Thymus daenensis Čelak essential oil. Evidence-Based Complem. Altern. Med.10, 1–12 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hosseini Behbahani M, Ghasemi Y, Khoshnoud M, Faridi P, Moradli Gh, Montazeri-Najafabady N. Volatile oil composition and antimicrobial activity of two Thymus species. Pharmacogn. J. 2013;5:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.phcgj.2012.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teimouri M. Antimicrobial activity and essential oil composition of Thymus daenensis Čelak. from Iran. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012;6:631–635. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alizadeh A, Alizadeh O, Amari G, Zare M. Essential oil composition, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity and antifungal properties of Iranian Thymus daenensis subsp. daenensis Čelak. as in influenced by ontogenetical variation. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2013;16:59–70. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2013.764190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amirmohammadi F, Azizi M, Nemati S, Iriti M, Vitalini S. Analysis of the essential oil composition of three cultivated Nepeta species from Iran. Z. Nat. C. 2020;75(7–8):247–254. doi: 10.1515/znc-2019-0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aničić N, Gašić U, Lu F, Ćirić A, Ivanov M, Jevtić B, Dimitrijević M, Anđelković B, Skorić M, Nestorović Živković J, Mao Y, Liu J, Tang C, Soković M, Ye Y, Mišić D. Antimicrobial and immunomodulating activities of two endemic Nepeta species and their major iridoids isolated from natural sources. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;14(5):414. doi: 10.3390/ph14050414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezzatzadeh, E., Fallah Iri Sofla, S., Pourghasem, E., Rustaiyan, A., & Zarezadeh, A. Antimicrobial activity and chemical constituents of the essential oils from root, leaf and aerial part of Nepeta asterotricha from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 17, 415–421 (2014).

- 24.Mirza M, Ahmadi L, Tayebi M. Volatile constituents of Hymenocrater incanus Bunge, an Iranian endemic species. Flav. Fragr. J. 2001;16:239–240. doi: 10.1002/ffj.983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morteza-Semnani K, Saeedi M, Akbarzadeh M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Hymenocrater elegans Bunge. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2010;13:260–266. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2010.10643820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morteza-Semnani K, Saeedi M, Akbarzadeh M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Hymenocrater calycinus (Boiss.) Benth. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2012;15:708–714. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2012.10644110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadi F, Sadeghi S, Modarresi M, Abiri R, Mikaeli A. Chemical composition, in vitro anti-microbial, antifungal and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus Benth., of Iran. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morteza-Semnani K, Akbarzadeh M, Changizi Sh. Essential oils composition of Stachys byzantina, S. inflata, S. lavandulifolia and S. laxa from Iran. Flav. Fragr. J. 2006;21:300–303. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sajjadi SE, Somae M. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Stachys inflata Benth. from Iran. Chem. NatuComp. 2004;40:378–380. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meshkatalsadat MH, Sadeghi Sarabi R, Moharramipour S, Akbari N. Chemical constituents of the essential oils of aerial part of the Stachys lavandulifolia Vahl. and Stachys inflata Benth. from Iran. Asian J. Chem. 2007;19:4805–4808. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alibakhshi M, Mahdavi SKh, Mahmoudi J, Gholichnia H. Phytochemical study of essential oil of Stachys inflata in different habitats of Mazandaran province. Eco-phytoJ. Med. Plants. 2014;2:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahimabadi A, Ebrahimabadia E, Jafari-Bidgolia Z, Jookar Kashia F, Mazoochi A, Batooli H. Composition and antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and extracts of Stachys inflata Benth. from Iran. Food Chem. 2010;119:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.-Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Quadruple Mass Spectroscopy. Carol Stream IL, 804. (Allured Publishing Cropration, 2007).

- 34.Safaei Ghomi J, Nahavand Sh, Batooli H. Studies on the antioxidant activity of the volatile oil and methanol extracts of Nepeta laxiflora Benth. and Nepeta sessilifolia Bunge. J. Food Biochem. 2011;35:14086–14092. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2010.00470.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Llorens L, Llorens-Molina JA, Agnello S, Boira H. Geographical and environment-related variations of essential oils in isolated populations of Thymus richardii Pers. In the Mediterranean basin. Biochem. Syst. Eco. 2014;56:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2014.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villanueva-Bermejo D, Angelov I, Vicente G, Stateva RP, Rodriguez García-Risco M, Reglero G, Ibañez E, Fornari T. Extraction of thymol from different varieties of thyme plants using green solvents. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2015;95:2901–3290. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavaric N, Mozina SS, Kladar N, Bozin B. Chemical profile, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of thyme and oregano essential oils, thymol and carvacrol and their possible synergism. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2015;18:1013–1021. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2014.971069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ultee A, Kets TPW, Smid EJ. Mechanisms of action of carvacrol on the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:4606–4610. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.10.4606-4610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talebi SM, Ghorbani Nohooji M, Yarmohammadi M, Khani M, Matsyura A. Effect of altitude on essential oil composition and on glandular trichome density in three Nepeta species (N. sessilifolia, N. heliotropifolia and N. fissa) Mediter Bot. 2019;40:81–93. doi: 10.5209/MBOT.59730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamzad MA, Rustaiyan SM, Jamzad Z. Composition of the essential oils of Nepeta sessilifolia Bunge and Nepeta haussknechtii Bornm. from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2008;20:533–535. doi: 10.1080/10412905.2008.9700081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghavam M, Afzali A, Manconi M, et al. Variability in chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Rosa × damascena Herrm. from mountainous regions of Iran. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021;8:22. doi: 10.1186/s40538-021-00219-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sales-Campos H, de Souza PR, Peghini BC, da Silva JS, Cardoso CR. An overview of the modulatory effects of oleic acid in health and disease. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013;13:201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choque B, Catherine D, Rioux V, Legrand P. Linoleic acid: Between doubts and certainties. Biochimie. 2014;96:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonçalves, F.A.G., Colen, G., & Takahashi, J.A. Yarrowia lipolytica and its multiple applications in the biotechnological industry. Sci. World. J. 2014, 1–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Yavari AR, Nazeri V, Sefidkon F, Hassani ME. Evaluation of some ecological factors, morphological traits and EO productivity of Thymus migricus Klokov & Desj.-Shost. Iran J. Med. Arom. Plants. 2010;26:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaimand, K., & Rezaei, M.B. Essential Oil, Distillers, Test Methods and Inhibition Index in EOAnalysis. 1st edn (Publication of the Medicinal Plants Association, 2006).

- 47.Nejad Ebrahimi S, Hadian J, Mirjalili MH, Sonboli A, Yousefzadi M. Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of Thymus caramanicus at different phonological stages. Food Chem. 2008;110:927–931. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isman MB, Machial CM. Pesticides based on plant essential oils: From traditional practice to commercialization. In: Rai M, Carpinella MC, editors. Naturally Occurring Bioactive Compounds. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dadashpour M, Rasooli I, Sefidkon F, Taghizadeh M, Astaneh DA. Comparison of ferrous ion chelating, free radical scavenging and anti tyrosinase properties of Thymus daenensis essential oil with commercial thyme oil and thymol. J. Adv. Med. Biomed. Res. 2011;19(77):41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Jahanbazi P, Enteshari S, Malekpoor F, Hamedi B. Antimicrobial activity of some Iranian medicinal plants. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2010;62:633–641. doi: 10.2298/ABS1003633G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mattanna P, Da Rosa PD, Poli J, Richards NSPS, Daboit TC, Scroferneker ML, Valente P. Lipid profile and antimicrobial activity of microbial oils from 16 oleaginous yeasts isolated from artisanal cheese. Rev. Bras. Bioci. 2014;12:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casillas-Vargas G, Ocasio-Malavé C, Medina S, Morales-Guzmán C, Del Valle RG, Carballeira NM, Sanabria-Ríos DJ. Antibacterial fatty acids: An update of possible mechanisms of action and implications in the development of the next-generation of antibacterial agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021;82:101093. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2021.101093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agoramoorthy G, Chandrasekaran M, Venkatesalu V, Hsu M. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of fatty acid methyl esters of the blind-your-eye mangrove from India. BJM. 2007;38:739–742. [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Martino L, De Feo V, Nazzaro F. Chemical composition and in vitro antimicrobial and mutagenic activities of seven Lamiaceae essential oils. Molecules. 2009;14:4213–4230. doi: 10.3390/molecules14104213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luciardi M, Blázquez M, Cartagena E, Bardon A, Arena M. Mandarin essential oils inhibit quorum sensing and virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. LWT-Food Sci. Tech. 2015;68:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.-Lade, H., Chung, S.H., Lee, Y., Kumbhar, B.V., Joo, H.S., Kim, Y.G., Yang, Y.H., & Kim, J.S. Thymol reduces agr-mediated virulence factor phenol-soluble modulin production in Staphylococcus aureus. Biomed. Res. Int. 9, 8221622 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Fazly Bazzaz BS, Haririzadeh G. Screening of Iranian plants for antimicrobial activity. Pharm. Biol. 2003;41:573–583. doi: 10.1080/13880200390501488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.-Rezzoug, M., Bakchiche, B., Gherib, A., Roberta, A., Flamini, G., Kilinçarslan, Ö, Mammadov, R., & Bardaweel, S.K. Chemical composition and bioactivity of essential oils and ethanolic extracts of Ocimum basilicum L. and Thymus algeriensis Boiss. & Reut. from the Algerian Saharan Atlas. BMC Complem. Altern. Med. 19(1), 146 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Ghavam M. In vitro biological potential of the essential oil of some aromatic species used in Iranian traditional medicine. Inflammopharmacology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10787-022-00934-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.-Ghavam, M. Tripleurospermum disciforme (C.A.Mey.) Sch.Bip., Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch.Bip, and Achillea biebersteinii Afan.: Efficiency, chemical profile, and biological properties of essential oil. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric.8, 45 (2021).

- 61.-Clinical, & Institute, L. S. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard. (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.