Abstract

Background:

While pain is a significant problem for oncology patients, little is known about inter-individual variability in pain characteristics.

Objective:

Identify subgroups of patients with distinct worst pain severity profiles and evaluate for differences among these subgroups in demographic, clinical, and pain characteristics and stress and symptom scores.

Methods:

Patients (n=934) completed questionnaires six times over two chemotherapy cycles. Worst pain intensity was assessed using a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale. Brief Pain Inventory was used to assess various pain characteristics. Latent profile analysis was used to identify subgroups of patients with distinct pain profiles.

Results:

Three worst pain profiles were identified (Low (17.5%), Moderate (39.9%), Severe (42.6%). Compared to the other two classes, Severe class was more likely to be single and unemployed, had a lower annual household income, a higher body mass index, a higher level of comorbidity, and a poorer functional status. Severe class wase more likely to have both cancer and non-cancer pain, a higher number of pain locations, higher frequency and duration of pain, worse pain quality scores, and higher pain interference scores. Compared to the other two classes, Severe class reported lower satisfaction with pain management and higher global, disease-specific, and cumulative life stress, as well as higher anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and cognitive dysfunction scores.

Conclusions:

Unrelieved pain is a significant problem for over 80% of outpatients.

Implications for Practice:

Clinicians need to perform comprehensive pain assessments; prescribe pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; and initiate referrals for pain management and psychological services.

Introduction

As noted in a recent meta-analysis,1 approximately 55% of oncology patients receiving treatment experience unrelieved pain and 32.4% report that is moderate to severe. Uncontrolled pain results in interruptions in treatments;2 increases in fatigue, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms;3, 4 and decrements in quality of life.5

Guidelines for cancer pain management recommend that comprehensive assessments be done to guide multimodal interventions.6 However, this in-depth evaluation is not always done in research studies because of potential respondent burden. In fact, most studies use binary classifications (e.g., no pain vs. severe pain) to evaluate for associations between various patient characteristics and the occurrence of pain.7,8 Additional information is needed on the risk factors and pain characteristics associated with inter-individual variability in oncology patients’ pain experiences.

While latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to identify subgroups of oncology patients with a variety of distinct symptom profiles,9–11 our study was the first to perform this analysis for pain.12 In this study of 1305 patients undergoing chemotherapy, 28.4% did not report pain. Of the remaining 934 patients, three distinct worst pain profiles were identified (i.e., Mild [12.5%], Moderate [28.6%], Severe [30.5%]). Compared to the None class, the Severe class had fewer years of education and a lower annual income; were less likely to be employed and married; less likely to exercise on a regular basis, had a higher comorbidity burden, and a worse functional status. While this study provided new information on demographic and clinical characteristics associated with more severe pain, differences among the three pain classes in pain characteristics were not evaluated.

An emerging area that warrants consideration is the relationship between stress and pain.13 As noted in one study of older adults,14 higher levels of global stress were associated with higher pain intensity scores. In addition, in the aforementioned study,12 compared to the None class, the Severe class reported higher levels of global, disease-specific, and cumulative life stress, as well as lower levels of resilience. Of note, early life stress appears to decrease an individual’s pain threshold.15 However, resilience may act as a moderator of these effects.16 Therefore, a more detailed evaluation of the relationships between pain and global, cancer-related, and cumulative life stress may increase our understanding of the pain experiences of oncology patients.

Previous research has documented associations between unrelieved pain and higher levels of depressive symptoms,17 anxiety,17,18 fatigue,9 sleep disturbance,19 and cognitive dysfunction.20 However, no studies have evaluated for differences in these symptoms among oncology patients with distinct pain profiles. Given the paucity of research on pain characteristics associated with distinct pain profiles, the current study is an extension of our previous LPA study,12 that used oncology outpatients’ ratings of worst pain intensity (n=934), to identify subgroups of patients with distinct worst pain profiles and evaluate how these subgroups differed on demographic, clinical, and pain characteristics, as well as measures of stress, resilience, and common co-occurring symptoms.

Methods

Patients and settings

This study is part of a larger, study of the symptom experience of outpatients receiving chemotherapy.21 Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, gastrointestinal, gynecological, or lung cancer; had received chemotherapy within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of chemotherapy; were able to read, write, and understand English; and gave written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veteran’s Affairs hospital, and four community-based oncology programs. The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment.

Study procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. Of the 2234 patients approached during their first or second cycle of chemotherapy, 1343 consented to participate. Patients completed questionnaires, six times over two chemotherapy cycles (i.e., prior to chemotherapy administration (assessments 1 and 4), approximately 1 week after chemotherapy administration (assessments 2 and 5), and approximately 2 weeks after chemotherapy administration (assessments 3 and 6)). Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information. Of the 1343 patients, 934 reported pain and were evaluated in this analysis.

Instruments

Demographic and Clinical Measures

Patients completed a demographic questionnaire, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale,22 Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ),23 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),24 and a smoking history questionnaire. Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information. Toxicity of the chemotherapy regimen was evaluated using the MAX2 score.25

Pain Measure

Worst pain severity was assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI).26 Patients were asked to indicate whether they were generally bothered by pain (yes/no). If they were generally bothered by pain, they indicated if they had non-cancer pain, cancer pain, or both types of pain. Then, patients rated their worst pain severity in the past 24 hours using a 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) numeric rating scale (NRS). Additional items on the BPI that were evaluated included: current and average pain intensity; number of days per week that pain interfered with mood and/or activities; number of hours per day in pain; number of pain locations; pain qualities; and pain interference with eight activities. For the pain interference items, a total mean score was computed.

Stress and Resilience Measures

The 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used as a measure of global perceived stress according to the degree that life circumstances are appraised as stressful over the course of the previous week.27 In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

The 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was used to measure cancer-related distress.28 Patients rated each item based on how distressing each potential difficulty was for them during the past week “with respect to their cancer and its treatment”. Three subscales evaluated levels of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Sum scores of ≥24 indicate clinically meaningful post traumatic symptomatology and scores of ≥33 indicate probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).29 In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the IES-R total score was 0.92.

The 30-item Life Stressor Checklist-Revised (LSC-R) is an index of lifetime trauma exposure (e.g., being mugged).30 The total LSC–R score is obtained by summing the total number of events endorsed. If patients endorsed an event, they were asked to indicate how much that stressor affected their life in the past year. Responses were averaged to yield a mean “Affected” score. A PTSD sum score was created based on the number of positively endorsed items (out of 21) that reflect the DSM-IV PTSD Criteria A for having experienced a traumatic event.

The 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRS) evaluates a patient’s personal ability to handle adversity.31 Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicative of higher self-perceived resilience. The normative adult mean score in the United States is 31.8 (±5.4).32 In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Other symptom measures

An evaluation of other common symptoms was done using valid and reliable instruments. The symptoms and their respective measures were: anxiety (Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories (STAI-T and STAI-S)33); depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D)34); morning and evening fatigue and morning and evening energy (Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS)35); sleep disturbance (General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS)36); cognitive function (Attentional Function Index (AFI)37)).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated for sample characteristics at enrollment using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 27 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). LPA was used to identify unobserved subgroups of patients (i.e., latent classes) with distinct worst pain profiles. The LPA was performed using MPlus™ Version 8.4.38

Estimation was carried out with full information maximum likelihood with standard error and a chi-square test that is robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations (“estimator=MLR”). Model fit was evaluated to identify the solution that best characterized the observed latent class structure with the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLRM), entropy, and latent class percentages that were large enough to be reliable. Missing data were accommodated with the use of the Expectation-Maximization algorithm.39

Differences among the latent classes in demographic, clinical, and pain characteristics, stress and resilience measures, and symptom severity scores were evaluated using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis, or Chi-Square tests. All of the analyses used actual values. No adjustments were made for missing data. Therefore, the samples sizes may vary based on the number of patients who responded to each of the questions. A p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Post hoc contrasts were done using a Bonferroni corrected p-value of <.017 (.05/3 possible pairwise comparisons).

Results

Latent profile analysis

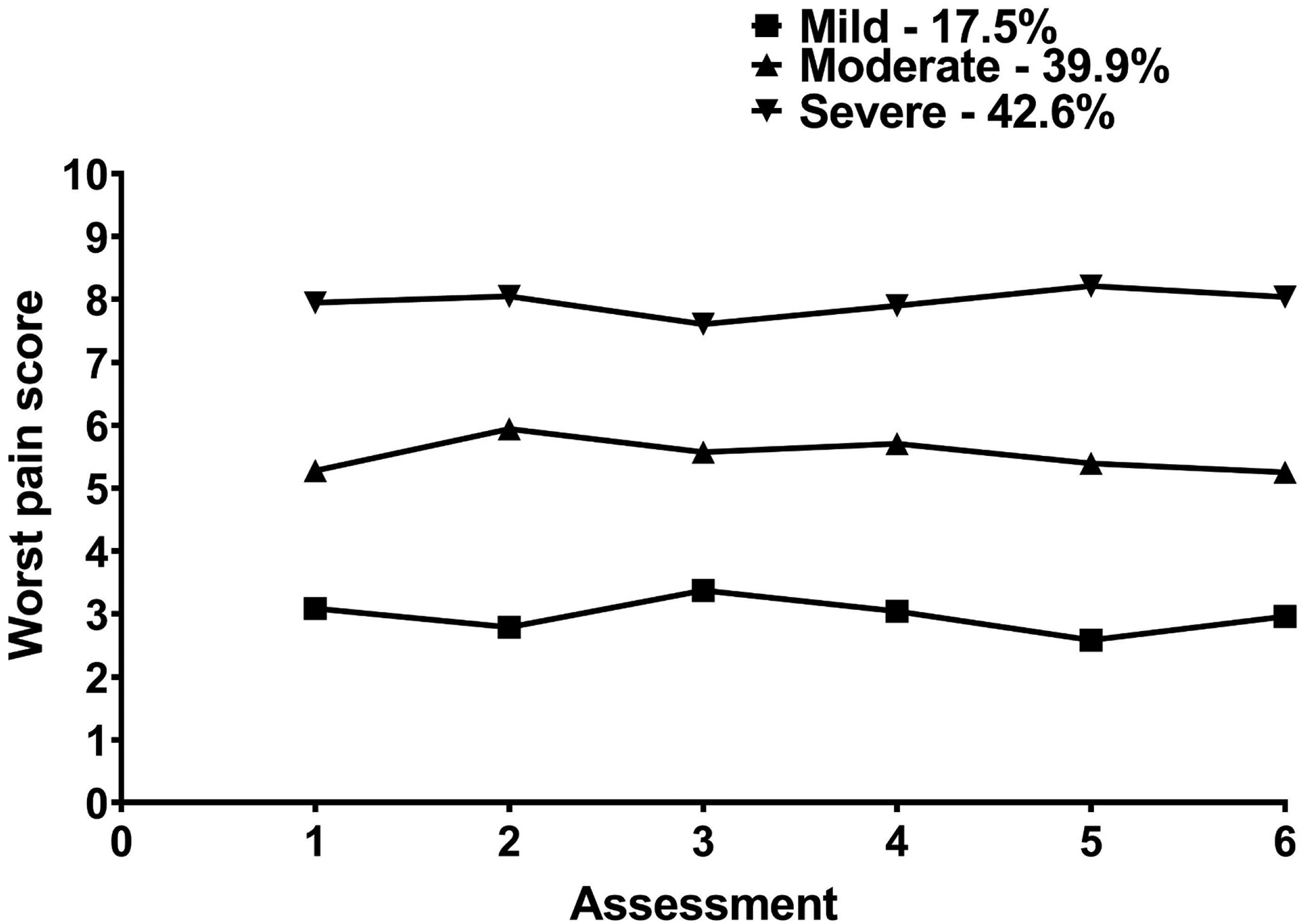

A three-class solution was selected because the 3-class solution fit the data better than the 2-class solution. The BIC for the 3-class solution was lower than the BIC for the 2-class solution. In addition, the VLMR was significant for the 3-class solution. Although the BIC was smaller for the 4-class than for the 3-class solution, the VLMR for 4-classes was not significant. Of the 934 patients in this study, 17.5% were in the Mild, 39.9% in the Moderate, and 42.6% in the Severe classes (see the Figure). The latent classes were named based on clinically meaningful cutoff scores for worst pain.40

Figure –

Trajectories of worst pain for the three latent classes.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Compared to the other two classes, the Severe class had fewer years of education, a lower annual household income, were more likely to be single and unemployed, had a higher number of comorbid conditions, a higher SCQ score, a lower functional status, and were more likely to self-report diagnoses of anemia, depression, and back pain. Compared to the Moderate class, the Severe class was less likely to be White, more likely to be of Hispanic or mixed ethnicity, more likely to have elder care responsibilities, had a higher BMI, was less likely to exercise in a regular basis, and was more likely to self-report a diagnosis of ulcer or stomach disease. Compared to the Mild class, the Severe class was more likely to be female and self-report a diagnosis of osteoarthritis. Compared to the Mild class, the Moderate and Severe classes were less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer and were more likely to have a higher MAX2 score (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in Demographic, Clinical, Symptom Characteristics Among the Worst Pain Latent Classes

| Characteristic | Low (1) 17.5% (n=163) |

Moderate (2) 39.9% (n=373) |

Severe (3) 42.6% (n=398) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 57.9 (12.0) | 57.3 (12.4) | 55.9 (12.8) | F = 1.82, p = .163 |

| Education (years) | 16.4 (3.0) | 16.3 (2.9) | 15.6 (2.9) | F = 6.36, p = .002 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.4 (5.6) | 25.9 (5.3) | 27.1 (6.1) | F = 4.45, p = .012 2 < 3 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score | 2.9 (2.2) | 3.0 (2.6) | 3.0 (2.8) | F = 0.06, p = .946 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 82.7 (11.9) | 80.3 (11.4) | 74.1 (12.3) | F = 38.58, p <.001 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Number of comorbid conditions | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.6) | F = 21.10, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | 4.9 (2.6) | 5.4 (2.9) | 7.0 (3.8) | F = 32.12, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 2.0 (3.7) | 2.2 (4.3) | 2.0 (4.2) | KW, p= .351 |

| Time since diagnosis (years, median) | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.45 | |

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.8 (1.5) | F = 0.77, p = .465 |

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvementa | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.3 (1.3) | F = 0.12, p = .888 |

| Number of metastatic sites excluding lymph node involvement | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | F = 0.07, p = .931 |

| MAX2 score | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) | F = 5.70, p = .003 1 < 2 and 3 |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Gender (% female) | 72.4 (118) | 79.4 (296) | 84.4 (336) | X2 = 10.93, p = .004 1 < 3 |

| Self-reported ethnicity | X2 = 23.19, p = .001 | |||

| White | 66.0 (107) | 75.0 (276) | 66.4 (259) | 2 > 3 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 16.7 (27) | 12.5 (46) | 10.0 (39) | NS |

| Black | 7.4 (12) | 6.5 (24) | 8.2 (32) | NS |

| Hispanic, Mixed, or Other | 9.9 (16) | 6.0 (22) | 15.4 (60) | 2 < 3 |

| Married or partnered (% yes) | 70.4 (114) | 64.7 (236) | 55.8 (218) | X2 = 12.36, p = .002 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Lives alone (% yes) | 19.1 (31) | 21.6 (79) | 25.6 (101) | X2 = 3.29, p = .193 |

| Currently employed (% yes) | 38.0 (62) | 37.3 (138) | 26.2 (103) | X2 = 13.18, p = .001 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Annual household income | KW, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

|||

| Less than $30,000b | 14.9 (21) | 13.6 (45) | 30.0 (110) | |

| $30,000 to $70,000 | 26.2 (37) | 20.0 (66) | 24.0 (88) | |

| $70,000 to $100,000 | 13.5 (19) | 19.7 (65) | 13.9 (51) | |

| Greater than $100,000 | 45.4 (64) | 46.7 (154) | 32.2 (118) | |

| Child care responsibilities (% yes) | 23.1 (37) | 21.3 (78) | 22.2 (86) | X2 = 0.23, p = .891 |

| Elder care responsibilities (% yes) | 6.1 (9) | 6.4 (22) | 12.1 (43) | X2 = 8.50, p =.014 2 < 3 |

| Past or current history of smoking (% yes) | 41.5 (66) | 36.7 (135) | 38.4 (151) | X2 = 1.10, p = .576 |

| Exercise on a regular basis (% yes) | 68.4 (108) | 72.4 (265) | 63.4 (246) | X2 = 7.02, p = .030 2 > 3 |

| Specific comorbid conditions (% yes) | ||||

| Heart disease | 4.3 (7) | 6.7 (25) | 7.8 (31) | X2 = 2.25, p = .325 |

| High blood pressure | 32.5 (53) | 27.6 (103) | 33.7 (134) | X2 = 3.50, p = .174 |

| Lung disease | 10.4 (17) | 11.8 (44) | 14.1 (56) | X2 = 1.70, p = .427 |

| Diabetes | 7.4 (12) | 9.1 (34) | 11.8 (47) | X2 = 3.04, p = .219 |

| Ulcer or stomach disease | 4.3 (7) | 3.5 (13) | 8.0 (32) | X2 = 8.21, p = .017 2<3 |

| Kidney disease | 0.0 (0) | 1.9 (7) | 2.3 (9) | X2 = 3.61, p = .164 |

| Liver disease | 7.4 (12) | 6.7 (25) | 7.0 (28) | X2 =.082, p = .960 |

| Anemia or blood disease | 8.6 (14) | 11.0 (41) | 19.1 (76) | X2 = 15.33, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Depression | 16.0 (26) | 18.5 (69) | 29.1 (116) | X2 = 17.46, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Osteoarthritis | 8.6 (14) | 14.7 (55) | 17.6 (70) | X2 = 7.40, p = .025 1 < 3 |

| Back pain | 21.5 (35) | 27.1 (101) | 43.7 (174) | X2 = 36.27, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.3 (7) | 3.2 (12) | 4.8 (19) | X2 = 1.22, p = .543 |

| Cancer diagnosis | X2 = 16.12, p = .013 | |||

| Breast cancer | 37.4 (61) | 44.5(166) | 38.9 (155) | NS |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 39.3 (64) | 24.7 (92) | 27.1 (108) | 1 > 2 and 3 |

| Gynecological cancer | 14.1 (23) | 20.1 (75) | 20.1 (80) | NS |

| Lung cancer | 9.2 (15) | 10.7 (40) | 13.8 (55) | NS |

| Prior cancer treatment | X2 = 7.39, p = .287 | |||

| No prior treatment | 25.8 (40) | 23.7 (86) | 21.8 (85) | |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 43.2 (67) | 41.6 (151) | 40.3 (157) | |

| Surgery and CTX, or surgery and RT, or CTX and RT | 21.9 (34) | 22.6 (82) | 21.0 (82) | |

| Surgery and CTX and RT | 9.0 (14) | 12.1 (44) | 16.9 (66) | |

| Metastatic sites | X2 = 2.16, p = .905 | |||

| No metastasis | 27.7 (44) | 31.6 (117) | 32.4 (128) | |

| Only lymph node metastasis | 22.0 (35) | 21.1 (78) | 22.8 (90) | |

| Only metastatic disease in other sites | 23.9 (38) | 22.7 (84) | 20.3 (80) | |

| Metastatic disease in lymph nodes and other sites | 26.4 (42) | 24.6 (91) | 24.6 (97) | |

| Receipt of targeted therapy | X2 = 1.98, p = .372 | |||

| No | 66.0 (105) | 71.7 (263) | 68.2 (268) | |

| Yes | 34.0 (54) | 28.3 (104) | 31.8 (125) | |

| CTX regimen | X2 = 6.10, p = .192 | |||

| Only CTX | 66.0 (105) | 71.7 (263) | 68.2 (268) | |

| Only targeted therapy | 5.7 (9) | 2.7 (10) | 2.3 (9) | |

| Both CTX and targeted therapy | 28.3 (45) | 25.6 (94) | 29.5 (116) | |

| Cycle length | KW = 4.89, p = .087 | |||

| 14-day cycle | 47.2 (76) | 39.5 (146) | 37.9 (149) | |

| 21-day cycle | 47.8 (77) | 51.4 (190) | 54.7 (215) | |

| 28-day cycle | 5.0 (8) | 9.2 (34) | 7.4 (29) | |

| Emetogenicity of the CTX regimen | KW = 5.34, p = .069 | |||

| Minimal/low | 17.4 (28) | 20.8 (77) | 24.1 (95) | |

| Moderate | 66.5 (107) | 57.6 (213) | 61.2 (241) | |

| High | 16.1 (26) | 21.6 (80) | 14.7 (58) | |

| Antiemetic regimen | X2 = 9.15, p = .165 | |||

| None | 10.2 (16) | 6.4 (23) | 6.2 (24) | |

| Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone | 15.9 (25) | 22.3 (80) | 22.4 (87) | |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid | 54.1 (85) | 45.5 (163) | 45.9 (178) | |

| NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | 19.7 (31) | 25.7 (92) | 25.5 (99) |

Total number of metastatic sites evaluated was 9.

Reference group

Abbreviations: CTX, chemotherapy; kg, kilograms; KW, Kruskal Wallis; m2, meters squared; n/a, not applicable; NK-1, neurokinin-1; NS, not significant; pw, pairwise; RT, radiation therapy; SD, standard deviation.

Pain characteristics

Significant differences in pain now, average pain, worst pain, number of days per week in pain, number of hours per day in pain, and number of pain locations were found among the three latent classes in the expected pattern (i.e., Mild<Moderate<Severe; Table 2). The three classes had significantly different pain interference scores for: general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, and sleep, as well as overall interference (i.e., Mild<Moderate<Severe). Significant differences in pain quality scores (i.e., throbbing, shooting, sharp, exhausting, tiring, penetrating, miserable pain) were found among three classes (i.e., Mild<Moderate<Severe).

Table 2.

Differences in Pain Characteristics Among the Worst Pain Latent Classes

| Characteristic | Low (1) 17.5% (n=163) |

Moderate (2) 39.9% (n=373) |

Severe (3) 42.6% (n=398) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Pain now | 0.7 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.6) | 2.8 (2.3) | F = 71.58, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Average pain | 1.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.5) | 4.3 (1.9) | F = 152.47, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Worst pain | 2.9 (1.9) | 5.3 (1.7) | 8.1 (1.4) | F = 514.98, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Number of days per week in pain | 1.5 (2.0) | 2.3 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.4) | F = 83.91, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Number of hours per day in pain | 3.9 (5.7) | 7.8 (8.2) | 10.1 (8.3) | F = 27.80, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Number of pain locations | 5.2 (4.6) | 7.3 (6.7) | 10.7 (9.0) | F = 29.58, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Percentage of relief from pain medication | 65.7 (37.5) | 70.5 (28.7) | 64.8 (26.4) | F = 2.50, p = .083 |

| Satisfaction with pain management | 8.0 (2.5) | 7.6 (2.2) | 6.6 (2.6) | F = 17.85, p <.001 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Pain interference | ||||

| General activity | 1.3 (2.0) | 2.5 (2.6) | 4.5 (3.0) | F = 81.87, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Mood | 1.6 (2.1) | 2.4 (2.3) | 4.1 (3.0) | F = 61.06, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Walking ability | 1.4 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.7) | 4.2 (3.2) | F = 60.22, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Normal work | 1.7 (2.5) | 2.9 (2.7) | 4.9 (3.2) | F = 72.98, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Relations with other people | 1.1 (1.9) | 1.7 (2.2) | 3.1 (3.0) | F = 41.18, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Sleep | 1.9 (2.3) | 2.7 (2.6) | 4.7 (3.1) | F = 67.38, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Enjoyment of life | 2.0 (2.5) | 2.6 (2.5) | 4.7 (3.1) | F = 68.94, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Sexual activity | 2.0 (3.4) | 2.5 (3.5) | 4.5 (4.1) | F = 30.45, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Mean pain interference score | 1.6 (1.8) | 2.5 (2.0) | 4.3 (2.5) | F = 95.38, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Both cancer and noncancer pain | 31.0 (44) | 36.3 (117) | 54.2 (202) | 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Other | 43.3 (39) | 37.6 (71) | 47.5 (123) | X2 = 4.38, p = .112 |

| Greater than 6 months | 42.5 (34) | 68.6 (116) | 73.3 (173) | 1 < 2 and 3 |

| Greater than 6 months | 19.4 (18) | 25.1 (63) | 28.7 (88) | NS |

| Continuously | 5.6 (7) | 12.8 (39) | 24.4 (85) | 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Took pain medication in the last week | ||||

| Yes | 37.6 (50) | 57.4 (183) | 76.5 (277) | X2 = 69.25, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Pain qualities (% yes) | ||||

| Aching | 69.3 (88) | 78.4 (247) | 85.2 (306) | X2 = 15.77, p <.001 1 < 3 |

| Throbbing | 22.2 (28) | 37.5 (117) | 49.4 (177) | X2 = 30.52, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Shooting | 8.7 (11) | 30.3 (95) | 44.3 (158) | X2 = 54.99, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Stabbing | 14.1 (18) | 23.3 (73) | 30.8 (143) | X2 = 39.01, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Gnawing | 9.4 (12) | 16.8 (52) | 25.8 (92) | X2 = 18.63, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Sharp | 20.6 (26) | 39.2 (123) | 57.3 (205) | X2 = 56.31, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Tender | 39.1 (50) | 43.2 (134) | 49.9 (179) | X2 = 5.54, p = .063 |

| Burning | 17.3 (22) | 18.1 (57) | 29.9 (251) | X2 = 16.03, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Exhausting | 13.4 (17) | 27.7 (86) | 48.3 (173) | X2 = 61.63, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Tiring | 32.6 (42) | 48.1 (150) | 68.2 (245) | X2 = 57.61, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Penetrating | 7.1 (9) | 21.2 (66) | 36.4 (129) | X2 = 47.27, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Nagging | 32.0 (41) | 42.9 (134) | 51.7 (184) | X2 = 15.65, p <.001 1 < 3 |

| Numb | 24.0 (31) | 25.6 (80) | 36.1(129) | X2 = 11.39, p = .003 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Miserable | 10.2 (13) | 20.4 (64) | 50.4 (181) | X2 = 103.14, p <.001 1 < 2 < 3 |

| Unbearable | 3.9 (5) | 5.1 (16) | 21.8 (78) | X2 = 53.07, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Compared to the other two classes, the Severe class was more likely to have both cancer and non-cancer pain, reported continuous pain, had stabbing, gnawing, burning, numb, and unbearable pain, and reported higher interference scores for relationships with other people, enjoyment of life, and sexual activity. Compared to the Moderate class, the Severe class was less likely to have only cancer pain. Compared to the Mild class, the Severe class was less likely to have only non-cancer pain, report cancer pain for less than 1 month, have pain 1 to 4 times per month, and was more likely to have aching and nagging pain as well as a self-reported diagnosis of arthritis.

Compared to the other two classes, the Mild class was more likely to have non-cancer pain for less than 1 month and was less likely to have non-cancer pain for greater than 6 months. Compared to the Moderate class, the Mild class was more likely to have a self-reported diagnosis of headache. Significant differences in the percentages of patients who took pain medication in the last week were found among three classes (i.e., Mild<Moderate<Severe). Compared to the other two classes, the Severe class was less likely to be satisfied with their pain management. No differences were found among the three classes in the self-reported diagnosis of low back pain and percentage of relief from pain medication (Table 2).

Stress and resilience

Compared to the other two classes, the Severe class reported higher PSS, intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal, and total IES-R, as well as LSC-R affected sum scores. Compared to the Moderate class, the Severe class reported a higher PTSD sum score. No differences were found among the three classes in the LSC-R total and CDRS scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in Stress Profile Measures Among the Worst Pain Latent Classes

| Measuresa | Low (1) 17.5% (n=163) |

Moderate (2) 39.9% (n=373) |

Severe (3) 42.6% (n=398) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| PSS total score (range 0 to 56) | 17.6 (6.9) | 18.5 (8.1) | 20.8 (8.4) | F = 12.48, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| IES-R total score (≥24) | 15.9 (10.5) | 17.9 (12.3) | 23.4 (15.3) | F = 23.74, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| IES-R intrusion | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.8) | F = 17.34, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| IES-R avoidance | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) | F = 12.27, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| IES-R hyperarousal | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.8) | F = 25.53, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| LSC-R total score (range 0–30) | 6.1 (4.2) | 6.3 (3.7) | 6.9 (4.3) | F = 2.77, p = .064 |

| LSC-R affected sum (range 0–150) | 11.7 (11.6) | 11.9 (9.3) | 15.0 (13.3) | F = 7.37, p = .001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| LSC-R PTSD sum (range 0–21) | 3.1 (3.3) | 3.2 (2.8) | 3.9 (3.4) | F = 4.15, p = .016 2 < 3 |

| CDRS total score (range 0–40) | 29.6 (6.2) | 30.3 (6.0) | 29.3 (6.7) | F = 2.27, p = .104 |

Abbreviations: CDRS, Connor Davidson Resilience Scale; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale – Revised; LSC-R, Life Stressor Checklist-Revised; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Clinically meaningful cutoff scores or range of scores

Co-occurring symptoms

Compared to the other two classes, the Severe class reported higher levels of depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, state anxiety, morning and evening fatigue, sleep disturbance, as well as worse decrements in morning energy and cognitive dysfunction. Compared to the Moderate class, the Severe class reported worse decrements in evening energy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differences in Co-Occurring Symptom Severity Scores Among the Worst Pain Latent Classes

| Symptomsa | Low (1) 17.5% (n=163) |

Moderate (2) 39.9% (n=373) |

High (3) 42.6% (n=398) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Depressive symptoms (≥16) | 11.5 (8.7) | 12.8 (9.2) | 16.4 (10.8) | F = 19.36, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Trait anxiety (≥31.8) | 34.4 (9.9) | 35.4 (10.1) | 38.3 (11.2) | F = 10.92, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| State anxiety (≥32.2) | 32.3 (11.7) | 33.6 (11.9) | 37.5 (13.7) | F = 13.46, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Morning fatigue (≥3.2) | 2.6 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.9) | 4.2 (2.4) | F = 44.79, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Evening fatigue (≥5.6) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.3 (1.9) | 5.9 (2.0) | F = 14.85, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Morning energy (≤6.2) | 4.5 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.1) | F = 5.92, p =.003 1 and 2 > 3 |

| Evening energy (≤3.5) | 3.6 (2.1) | 3.7 (1.9) | 3.3 (2.0) | F = 5.07, p =.006 2 > 3 |

| Sleep disturbance (≥43.0) | 47.6 (18.7) | 52.1 (19.0) | 61.0 (20.2) | F = 33.49, p <.001 1 and 2 < 3 |

| Attentional function (<5.0 = Low, 5 to 7.5 = Moderate, >7.5 = High) | 6.7 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.8) | F = 22.12, p <.001 1 and 2 > 3 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Clinically meaningful cutoff scores

Discussion

This study is the first to use LPA to identify patients with distinct worst pain severity profiles. Compared to the 32.4% reported in a meta-analysis,1 of the patients who reported pain over two cycles of chemotherapy, 82.5% of our sample experienced moderate to severe pain. However, our percentage is similar to findings from two registry studies of oncology patients with chronic pain that used cutpoints for average pain intensity to identify patients with moderate and severe pain (i.e., 75.5%7 and 81.7%8) Given that one of our goals was to identify risk factors for more severe pain, Table 5 summarizes the common and distinct risk factors associated with membership in the Moderate and Severe classes compared to the Low class.

Table 5.

Characteristics Associated with Membership in the Moderate and Severe Pain Group Compared to the Mild Pain Group

| Characteristic | Moderate pain | Severe pain |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Lower education | ■ | |

| More likely to be female | ■ | |

| Less likely to be married/partnered | ■ | |

| Less likely to be employed | ■ | |

| More likely to have a lower annual income | ■ | |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Lower functional status | ■ | |

| Higher number of comorbidities | ■ | |

| Higher comorbidity burden | ■ | |

| More likely to self-report anemia or blood disease | ■ | |

| More likely to self-report depression | ■ | |

| More likely to self-report osteoarthritis | ■ | |

| More likely to self-report back pain | ■ | |

| Less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer | ■ | ■ |

| Higher MAX2 score | ■ | ■ |

| Pain Characteristics | ||

| Sources of pain | ||

| Less likely to have only noncancer pain | ■ | |

| More likely to have both cancer and noncancer pain | ■ | |

| Causes of non-cancer pain | ||

| More likely to be arthritis | ■ | |

| Less likely to be headache | ■ | |

| Pain intensity | ||

| Higher current pain score | ■ | ■ |

| Higher average pain score | ■ | ■ |

| Higher worst pain score | ■ | ■ |

| Pain locations | ||

| Higher number of pain locations | ■ | ■ |

| Pain frequency | ||

| Higher number of days per week in pain | ■ | ■ |

| Higher number of hours per day in pain | ■ | ■ |

| Less likely to have pain 1 to 4 times per month | ■ | |

| More likely to have pain continuously | ■ | |

| Pain duration | ||

| Length of time with noncancer pain | ||

| Less likely to have pain less than 1 month | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have pain greater than 6 months | ■ | ■ |

| Length of time with cancer pain | ||

| Less likely to have pain less than 1 month | ■ | |

| Higher Pain interference scores | ||

| Mean pain interference score | ■ | ■ |

| Affective cluster | ||

| Mood | ■ | ■ |

| Enjoyment of life | ■ | |

| Relations with other people | ■ | |

| Activity cluster | ||

| General activity | ■ | ■ |

| Walking ability | ■ | ■ |

| Normal work | ■ | ■ |

| Sexual activity | ■ | |

| Both the affective and activity clusters | ||

| Sleep | ■ | ■ |

| Pain qualities a | ||

| Somatic nociceptive pain (e.g., bone metastasis, mucositis, arthritis, arthralgia, headache) | ||

| More likely to have aching pain | ■ | |

| More likely to have stabbing pain | ■ | |

| More likely to have throbbing pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have penetrating pain | ■ | ■ |

| Visceral nociceptive pain (e.g., visceral organ metastasis, bowel obstruction, coronary ischemia, urinary retention) | ||

| More likely to have sharp pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have gnawing pain | ■ | |

| Neuropathic pain (e.g., nerve damage; CTX-induced peripheral neuropathy, post-mastectomy, post-thoracotomy | ||

| More likely to have shooting pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have burning pain | ■ | |

| More likely to have numb pain | ■ | |

| Emotional aspects | ||

| More likely to have exhausting pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have tiring pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have miserable pain | ■ | ■ |

| More likely to have nagging pain | ■ | |

| More likely to have unbearable pain | ■ | |

| Pain management | ||

| More likely to take pain medication in the last week | ■ | ■ |

| Less likely to be satisfied with pain management | ■ | |

| Stress and Resilience Scores | ||

| Higher PSS score | ■ | |

| Higher IES-R total score | ■ | |

| Higher IES-R intrusion | ■ | |

| Higher IES-R avoidance | ■ | |

| Higher IES-R hyperarousal | ■ | |

| Higher LSC-R affected sum | ■ | |

| Symptom Characteristics | ||

| Higher depressive symptoms | ■ | |

| Higher trait anxiety | ■ | |

| Higher state anxiety | ■ | |

| Higher morning fatigue | ■ | |

| Higher evening fatigue | ■ | |

| Lower morning energy | ■ | |

| Higher sleep disturbance | ■ | |

| Lower attentional function | ■ | |

Abbreviations: IES-R, Impact of Event Scale-Revised; LSC-R, Life Stressor Checklist-Revised; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale.

Based on references cited below [1, 2]

1. Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult Cancer Pain, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(8):977–1007.

2. Hui D, Bruera E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(16):1640–1646.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

While no demographic characteristics were common to both the Moderate and Severe classes, consistent with previous findings in the general population,41 female gender, lower levels of education, and a lower annual income were associated with more severe pain. As noted in one report,42 socioeconomically disadvantaged patients are more likely to have unrelieved pain and experience system-level barriers to effective cancer pain management. For example, oncology patients with less than a high school education were less likely to report pain to clinicians; were more likely to have financial concerns about the costs of analgesics; and had fears about becoming addicted to opioids.42

While not reported previously, patients with gastrointestinal cancer were less likely to be classified in the Moderate and Severe pain classes. In addition, patients in these two pain classes had higher MAX2 scores that indicates greater toxicity from their chemotherapy regimen. More toxic chemotherapy regimens increase the likelihood of acute (e.g., oral or gastrointestinal mucositis) and chronic (e.g., chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN)) pain conditions. Of note, the Severe class had a worse comorbidity profile as well as higher rates of common painful conditions (i.e., osteoarthritis, back pain).

Pain characteristics

Sources of pain

Membership in the Severe class was associated with higher rates of both cancer and non-cancer pain. Of note, over 50% of these patients reported that both types of pain were present for greater than 6 months. The most common causes of non-cancer pain were: low back pain (49.0%), headache (34.9%), and arthritis (30.3%). Given the high rates of painful comorbid conditions in our sample, oncology clinicians need to assess for both cancer and non-cancer pain in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Pain intensity, locations, frequency, and duration

In addition to worst pain, current and average pain scores at enrollment differed among the three classes (Table 2). Consistent with previous registry studies,7,8 all three pain scores increased in a stepwise fashion. In addition, membership in both the Moderate and Severe pain classes was associated with a higher number of pain locations, higher number of hours per day and days per week in pain, and longer length of time experiencing non-cancer pain. For example, patients with the Moderate and Severe classes reported 2 to 4 days per week in significant pain that lasted for 8 to 10 hours per day, respectively. While 12.8% of the patients in the Moderate class reported continuous pain, this frequency occurred in 24.4% of the severe pain class. Equally important, the number of pain locations ranged from 7.3 to 10.7 in the Moderate and Severe pain classes, respectively. Of note, the differences in the majority of these pain characteristics between the Mild and Severe pain classes represent clinically meaningful differences (e.g., d=0.71 for hours per day; d=1.04 for days per week).43

Pain Interference

Compared to the Mild class, patients in the other two classes reported higher scores for the physical activity items on the interference scale (i.e., general activity, walking ability, normal work) as well as for mood and sleep. Given that this evaluation provides information on how pain impacts daily aspects of physical and emotional function44 and that these functional outcomes are being recommended as primary outcomes for analgesic efficacy,45 clinicians need to assess them prior to and during chemotherapy. For pain specific sites (e.g., oral mucositis), additional interference items may warrant evaluation (e.g., swallowing).

Pain Qualities

Recent work suggests that the pain qualities on the BPI can be grouped into somatic, visceral, neuropathic, and emotional categories.6,46 For somatic pain, defined as site-specific pain caused by nociceptors in somatic (skin, bones, muscles, or joints) tissues,47 while the Severe class had higher rates of all four qualities, both the Moderate and Severe classes had higher rates of throbbing and penetrating. While associations between these two qualities and specific pain conditions were not assessed, likely associations include osteoarthritis48 or bone metastases.46

Visceral pain, defined as vague or referred pain caused by nociceptors in visceral tissue,47 is often difficult to localize. Patients in both the Moderate and Severe classes reported higher rates of sharp pain and those in the Severe class reported higher rates of gnawing pain. Given that over 40% of the patients in our sample had gastrointestinal and gynecologic cancers, these relatively high rates for visceral qualities are not surprising.

Neuropathic pain is defined as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system”.49 While patients in both the Moderate and Severe classes were more likely to endorse shooting, patients in the Severe class reported higher rates for numb and burning. These findings may be related to the occurrence of postsurgical pain syndromes, CIPN, and/or back pain in our sample.

Equally important are the pain qualities that evaluate the emotional impact of pain. The qualities common to both the Moderate and Severe classes were exhausting, tiring, and miserable pain. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that unrelieved pain has a significant negative impact on oncology patients’ emotional state.50,51

Pain Management

While 57.4% and 76.5% of the patients in the Moderate and Severe classes reported that they took pain medications last week, the amount of pain relief they experienced was rated at only 70.5% and 64.8%, respectively. In addition, satisfaction with pain management was relatively low in both classes (i.e., 7.6 and 6.6.). Given that approximately 32% of oncology patients do not receive analgesics that correspond to their pain severity,52 it is not surprising that relatively high percentages of our patients reported inadequate pain relief and low levels of satisfaction. Given that our data were collected at a time when discussions about the opioid epidemic in the United States were widespread,53 a potential reason for the undertreatment in pain in our sample was a lower rate of opioid prescriptions.54 However, this hypothesis warrants confirmation because detailed information on analgesic prescriptions was not collected in this study.

Stress and resilience

This study is unique in that it evaluated for differences among our pain classes in global, disease-specific and cumulative life stress. While positive associations between pain and stress are found in the literature,55 this relationship has not been examined in detail in oncology patients. As shown in Table 4, all of the stress measures were highest in the Severe pain class. Of note, while the PSS does not have an established cutoff score, the patients in the Severe pain class reported a score (20.8) that was comparable to oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy56,57 and breast cancer survivors with persistent postmastectomy pain.58 In addition, these patients IES-R total scores are suggestive of post-traumatic symptomatology. While one would expect the resilience scores to differ among the classes, all three classes’ scores were below the normative score for adults in the United States,32 but comparable to those reported by patients in a chronic pain clinic.59

Multiple co-occurring symptoms

Patients in the Severe class reported the highest severity scores for all of the symptoms that were assessed in this study. Not surprising, the Severe class’ depressive symptom score was above the clinically meaningful cutoff. However, all three groups had clinically meaningful levels of trait and state anxiety, morning fatigue, and sleep disturbance, as well as decrements in evening energy. Taken together, these findings add to the evidence regarding the strong inter-relationships among pain and other common symptoms in oncology patients.60,61

Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration. Given that our sample was relatively homogenous in terms of gender and ethnicity, our findings may not generalize to more diverse racial and ethnic groups. Given that these patients were not recruited before the initiation of chemotherapy and not followed to the completion of treatment, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate for changes in the relationships among pain, stress, and multiple co-occurring symptoms. In addition, detailed information on the causes of cancer pain and analgesics were not available for our sample.

Implications for Practice

Despite these limitations, the findings from this study suggest that various demographic, clinical, and pain characteristics, as well as stress and multiple co-occurring symptoms, are associated with unrelieved pain in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. While a single pain intensity rating is obtained in clinical practice, our findings suggest that clinicians need to perform a comprehensive assessment of both cancer and non-cancer pain. Equally important, clinicians need to refer patients who report severe levels of pain and interference to symptom management and psychosocial services.

Acknowledgments:

This study was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA134900). Ms. Harris and Oppegaard and Dr. Calvo-Schimmel are supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR016920). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor. Ms. Harris is supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society. Ms. Oppegaard and Shin are supported by a grant from the Oncology Nursing Foundation.

References

- 1.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1070–1090 e1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miltenburg NC, Boogerd W. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy: A comprehensive survey. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(7):872–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langford DJ, Paul SM, Cooper B, et al. Comparison of subgroups of breast cancer patients on pain and co-occurring symptoms following chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Posternak V, Dunn LB, Dhruva A, et al. Differences in demographic, clinical, and symptom characteristics and quality of life outcomes among oncology patients with different types of pain. Pain. 2016;157(4):892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonhof CS, Trompetter HR, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F. Painful and non-painful chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(12):5933–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, et al. Adult Cancer Pain, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(8):977–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moryl N, Dave V, Glare P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and opioid use by outpatient cancer patients. J Pain. 2018;19(3):278–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witkin LR, Zylberger D, Mehta N, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and opioid use in outpatients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2017;18(5):583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright F, Dunn LB, Paul SM, et al. Morning fatigue severity profiles in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(5):355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tejada M, Viele C, Kober KM, et al. Identification of subgroups of chemotherapy patients with distinct sleep disturbance profiles and associated co-occurring symptoms. Sleep. 2019;42(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Utne I, Løyland B, Grov EK, et al. Distinct attentional function profiles in older adults receiving cancer chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;36:32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin J, Harris C, Oppegaard K, et al. Worst pain severity profiles of oncology patients are associated with significant stress and multiple co-occurring symptoms. J Pain. 2022;23(1):74–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lunde CE, Sieberg CB. Walking the tightrope: A proposed model of chronic pain and stress. Front Neurosci. 2020;14(270). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White RS, Jiang J, Hall CB, et al. Higher Perceived Stress Scale scores are associated with higher pain intensity and pain interference levels in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2350–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caes L, Roche M. Adverse early life experiences are associated with changes in pressure and cold pain sensitivity in young adults. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(4):1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M, Aslaksen PM, Flaten MA. Resilience as a moderator of pain and stress. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li XM, Xiao WH, Yang P, Zhao HX. Psychological distress and cancer pain: Results from a controlled cross-sectional survey in China. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Heer EW, Gerrits MM, Beekman AT, et al. The association of depression and anxiety with pain: a study from NESDA. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e106907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nahin RL, DeKosky ST. Comorbid pain and cognitive impairment in a nationally representative adult population: Prevalence and associations with health status, health care utilization, and satisfaction with care. Clin J Pain. 2020;36(10):725–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Melisko M, et al. Disease and treatment characteristics do not predict symptom occurrence profiles in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2371–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karnofsky D Performance scale. New York: Plenum Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(2):156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(4):423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Extermann M, Bonetti M, Sledge GW, O’Dwyer PJ, Bonomi P, Benson AB. MAX2—a convenient index to estimate the average per patient risk for chemotherapy toxicity: validation in ECOG trials. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(8):1193–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17(2):197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41(3):209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfe J, Kimmerling R. Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell-Sills L, Forde DR, Stein MB. Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(12):1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991;36(3):291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fletcher BS, Paul SM, Dodd MJ, et al. Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cimprich B, So H, Ronis DL, Trask C. Pre-treatment factors related to cognitive functioning in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). 8th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthen B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61(2):277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grol-Prokopczyk H Sociodemographic disparities in chronic pain, based on 12-year longitudinal data. Pain. 2017;158(2):313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stein KD, Alcaraz KI, Kamson C, Fallon EA, Smith TG. Sociodemographic inequalities in barriers to cancer pain management: a report from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Psychooncology. 2016;25(10):1212–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, Wyrwich KW, Norman GR. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(4):371–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Q, Mendoza TR, Dueck AC, et al. Determination of mild, moderate, and severe pain interference in patients with cancer. Pain. 2017;158(6):1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3325–3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hui D, Bruera E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1640–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy PM. Somatic Pain. In: Schmidt RF, Willis WD, eds. Encyclopedia of Pain. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2007:2190–2192. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawker GA. The assessment of musculoskeletal pain. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(S107):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, et al. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152(10):2204–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilkie DJ, Huang H-Y, Reilly N, Cain KC. Nociceptive and neuropathic pain in patients with lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(5):899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlaeger JM, Weng L-C, Huang H-L, et al. Pain quality by location in outpatients with cancer. Pain Manage Nurs. 2019;20(5):425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: An update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4149–4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maxwell JC. The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LeBaron VT, Camacho F, Balkrishnan R, Yao NA, Gilson AM. Opioid epidemic or pain crisis? Using the Virginia all payer claims database to describe opioid medication prescribing patterns and potential harms for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(12):e997–e1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li X, Hu L. The role of stress regulation on neural plasticity in pain chronification. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6402942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kwekkeboom KL, Tostrud L, Costanzo E, et al. The role of inflammation in the pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance symptom cluster in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(5):1286–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim HJ, Malone PS. Roles of biological and psychosocial factors in experiencing a psychoneurological symptom cluster in cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;42:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belfer I, Schreiber KL, Shaffer JR, et al. Persistent postmastectomy pain in breast cancer survivors: Analysis of clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors. J Pain. 2013;14(10):1185–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.France CR, Ysidron DW, Slepian PM, French DJ, Evans RT. Pain resilience and catastrophizing combine to predict functional restoration program outcomes. Health Psychology. 2020;39(7):573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pud D, Ben Ami S, Cooper BA, et al. The symptom experience of oncology outpatients has a different impact on quality-of-life outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(2):162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doong SH, Dhruva A, Dunn LB, et al. Associations between cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in patients prior to breast cancer surgery. Biol Res Nurs. 2015;17(3):237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]