Abstract

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)-induced cognitive dysfunction is common, but its underlying mechanisms are still poorly understood. In this study, we found that knockout of conventional protein kinase C (cPKC)γ significantly increased the phosphorylation of Tau at Ser214 and neurofibrillary tangles, but did not affect the activities of GSK-3β and PP2A in the hippocampal neurons of T1DM mice. cPKCγ deficiency significantly decreased the level of autophagy in the hippocampal neurons of T1DM mice. Activation of autophagy greatly alleviated the cognitive impairment induced by cPKCγ deficiency in T1DM mice. Moreover, cPKCγ deficiency reduced the AMPK phosphorylation levels and increased the phosphorylation levels of mTOR in vivo and in vitro. The high glucose-induced Tau phosphorylation at Ser214 was further increased by the autophagy inhibitor and was significantly decreased by an mTOR inhibitor. In conclusion, these results indicated that cPKCγ promotes autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway, thus reducing the level of phosphorylated Tau at Ser214 and neurofibrillary tangles.

Keywords: Conventional protein kinase C (cPKC)γ, Tau, Phosphorylated Tau, Autophagy, AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia due to insulin deficiency [1]. Compared with the non-diabetic population, T1DM patients perform poorly in most cognitive domains, such as learning, memory, attention, and executive function [2–4]. However, the molecular mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction caused by T1DM remain unclear.

Constant hyperglycemia can activate protein kinase C (PKC), thereby modulating a wide range of cellular responses [5]. PKC has many isoforms, including conventional PKC (α, βI, βII, and γ), novel PKC (δ, ε, η, and θ), and atypical PKC (ζ and λ). The γ isoform of conventional PKC (cPKCγ) is primarily present in the neurons of the central nervous system. Increased cPKCγ may be involved in diabetic complications, such as diabetic retinopathy and orofacial thermal hyperalgesia [6, 7]. Furthermore, cPKCγ activity in the hippocampus decreases significantly, along with learning and memory impairment, in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice [8]. Knockout of the cPKCγ gene aggravates the impairments of spatial learning and memory in T1DM mice [9]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which cPKCγ might improve cognitive function in type 1 diabetic animals remain unclear.

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein involved in microtubule maintenance, fast axonal transport, and other physiological functions in neurons [10]. However, hyperphosphorylation of Tau can lead to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), resulting in neuronal degeneration, synapse dysfunction, neuronal degeneration, and cognitive impairments [11, 12]. The effects of PKC on Tau phosphorylation remain controversial. On the one hand, PKC has been found to inhibit glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β activity by phosphorylating Ser9 of GSK-3β and then indirectly suppress the GSK-3β-stimulated phosphorylation of Tau [13]. On the other hand, some studies have also reported that PKC can directly phosphorylate Tau at Ser203, Ser214, and Thr231 [14]. These controversial results may be related to diseases, stages of the disease, the types of tissue, and different subtypes of PKC. As an important and neuron-specific subtype of PKC, the effect of cPKCγ on Tau phosphorylation in T1DM mice is not well understood. In this study, we explored the effects of cPKCγ on Tau hyperphosphorylation at different sites in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and the further molecular mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male wild-type (cPKCγ+/+) and cPKCγ knockout (cPKCγ−/−) C57BL/6 mice (18 g–22 g, 6–8 weeks) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and maintained in the Experimental Animal Center of Capital Medical University, PR China. Mice were housed in groups of three under constant temperature and humidity-control, and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Capital Medical University (SCXK2016-0006).

Induction of T1DM in Mice

The mice were randomly divided into four groups as follows: CON+ cPKCγ+/+ group (cPKCγ+/+ mice with citrate buffer treatment, n = 15), CON + cPKCγ−/− group (cPKCγ−/− mice with citrate buffer treatment, n = 15), T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group (cPKCγ+/+ mice with STZ treatment, n = 15), and T1DM + cPKCγ−/− group (cPKCγ-knockout mice with STZ treatment, n = 15). As previously described, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with either freshly-prepared STZ (50 mg/kg per day) dissolved in 0.1 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 4.5) or citrate buffer (5 mL/kg per day) for 5 consecutive days. Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein for measuring the blood glucose concentration with a OneTouch® Ultra blood glucose meter (Milpitas, CA, USA) every week. Mice were considered to have diabetes mellitus when their blood glucose levels were ≥ 11.1 mmol/L. Finally, the mice were killed at 8 weeks after STZ injection.

Rapamycin (S1039, Selleck Chemicals) was intracerebroventricularly injected into the right lateral ventricle using osmotic micropumps at 6 weeks after STZ injection. The micropumps were filled with rapamycin or vehicle (DMSO), and implanted subcutaneously along the back of the neck. An infusion cannula (0008851, Alzet Osmotic Pumps, Cupertino, CA, USA) connected to the micropump was placed in the right lateral ventricle at AP − 0.5 mm, ML + 1.0 mm, and DV − 2.8 mm relative to bregma. These mice received 0.2 mg/kg of rapamycin or an equal volume of DMSO for 14 days.

Morris Water Maze (MWM) Test

The MWM test was carried out as previously described [9]. Briefly, four different maze cues were fixed at the quarters of the tank periphery (Fig. 1E). At 8 weeks after STZ injection, the mice were trained for 5 days (4 trials per day) to find a fixed hidden platform, and the time that mice took to find the platform was recorded as the escape latency. If a mouse did not find the hidden platform in 90 s, it was guided to the platform and allowed to remain there for 10 s. On day 6, the platform was removed and the percentage of time that the mice spent in each quadrant was recorded. On day 7, the mice were tested to find the hidden platform and the escape latency was recorded. On day 8, the mice were allowed to find the visible platform to evaluate their sensorimotor abilities and motivation. Swim paths were recorded on a CCD camera and analyzed using WaterMaze 3 Software. Average swimming speed was determined to exclude motor impairments.

Fig. 1.

cPKCγ deficiency aggravates the spatial learning and memory impairment of T1DM mice. A, B Statistics of body weight and blood glucose in each group. C The escape latency of each group during 5 consecutive days of the learning process. D, E Statistics of the time spent in the target quadrant and a graph of the swim path measured after removing the platform on day 6. F, H Statistics of the escape latency and a graph of the swim path of each group after resetting the platform on day 7. G Statistics of the escape latency of each group in the visible test on day 8. I Statistics of speed in each group every day. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs CON + cPKCγ+/+ group. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group. +++P < 0.001 vs CON + cPKCγ−/− group.

Primary Hippocampal Neuron Culture and Treatment

Hippocampal tissue from postnatal cPKCγ+/+ and cPKCγ−/− mice were carefully dissociated, cut into small pieces (~1.0 mm3). The tissue was digested with 0.25% trypsin for 9 min to create a single-cell suspension, and then seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells/well in six-well plates in DMEM (C11995500BT, Gibco, Grand Island, USA). The DMEM was replaced by Neurobasal medium (21103-040, Gibco) supplemented with 2% B27 (17504-044, Gibco) after 6 h. Half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium once every 72 h. On day 7, 75 mmol/L glucose (A24940-01, Gibco) and mannitol (M4125, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) were each added to the medium and incubated for 72 h. The autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA, 5 mmol/L, S2767, Selleck Chemicals) and the autophagy activator rapamycin (50 nmol/L, S1039, Selleck Chemicals) dissolved in H2O or DMSO respectively, were added to the medium on day 7. Cells were transfected using lentiviral vectors containing the cPKCγ or the GFP gene (Lv-cPKCγ or Lv-GFP, Genepharma, Suzhou, China), according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Western Blot

Western blots were analyzed as described previously [15, 16]. In brief, hippocampal protein extracts and cell lysates with equal amounts of total protein were separated by 10%–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and subsequently probed with primary antibodies against Tau (1:1000, AHB0042, Invitrogen), the Tau epitopes phosphorylated at Ser214 (P-Ser214-Tau, 1:1000,44742G, Invitrogen), Ser396 (P-Ser396-Tau, 1:1000, 44752G, Invitrogen), Thr231 (P-Thr231-Tau, 1:1000, 44746G, Invitrogen), GSK-3β (1:1000, 9315, Cell Signaling Technology), the GSK-3β epitope phosphorylated at Ser9 (P-Ser9-GSK-3β 1:1000, 5558, Cell Signaling Technology), Akt (1:1000, 4691, Cell Signaling Technology), the Akt epitope phosphorylated at Ser473 (P-Ser473-Akt, 1:500, 4060, Cell Signaling Technology), protein phosphatase 2 A (PP2A) (1:1000, 2259, Cell Signaling Technology), the PP2A epitope phosphorylated at Tyr307 (P-Tyr307-PP2A, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) I/II (1:1000, 12741, Cell Signaling Technology), p62/SQSTM1(p62) (1:500, 5114, Cell Signaling Technology), β-actin (1:10000, 6008-1-Ig, Proteintech), the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, 1:1000, 2983, Cell Signaling Technology), the mTOR epitope phosphorylated at Ser2448 (P-Ser2448-mTOR, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK, 1:1000, 9102, Cell Signaling Technology), the ERK epitopes phosphorylated at Thr202/Tyr204 (P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, 1:1000, 9101, Cell Signaling Technology), adenosine 5’-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK, 1:1000, 07-350, Millipore), and the AMPK epitope phosphorylated at Thr172 (P-Thr172-AMPK, 1:1000, 2535, Cell Signaling Technology). Enhanced chemiluminescent reagent solution (chemiluminescent HRP substrate, Millipore Corp., USA) was used to detect the signals. Quantitative analysis of immunoblotting was done using Fusion Capt 16.15 software (Fusion FX6 XT, Vilber Lourmat, France). The amount of protein was quantified by densitometry and normalized to β-actin, an internal standard. The levels of P-Ser214-Tau, P-Ser396-Tau, P-Thr231-Tau, P-Ser9-GSK-3β, P-Ser473-Akt, P-Tyr307-PP2A, P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, and P-Thr172-AMPK were normalized against the levels of total Tau, GSK-3β, Akt, PP2A, mTOR, ERK, and AMPK, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence, and Bielschowsky’s Silver Staining

After the MWM test, the mice were transcranially perfused sequentially with 0.9% NaCl and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Sections 20 μm thick (bregma, − 1.58 to − 2.06 mm) were cut on a freezing microtome (CM1950 Clinical Cryostat, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

For immunohistochemistry, sections containing the hippocampus were incubated for 24 h at 4°C with primary antibodies against P-Ser214-Tau (1:100), anti-P-Ser396-Tau (1:100), and anti-P-Thr231-Tau (1:100). The sections were developed with Histostain TM-SP kits (Zemed, South San Francisco, CA, USA) and visualized with 3,30-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining.

After high glucose or mannitol treatment, primary hippocampal neurons were fixed in 4% PFA at room temperature for 30 min. For immunofluorescence, sections containing the hippocampus or fixed hippocampal neurons were incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with primary antibodies against P-Ser214-Tau (1:100), P-Ser396-Tau (1:100), and P-Thr231-Tau (1:100). Then the immunoreactivity was probed with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Fluorescently-stained sections were examined using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

NFTs were stained with modified Bielschowsky silver [17]. Briefly, sections containing the hippocampus were immersed in 3% AgNO3 aqueous solution for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing with distilled water, the sections were successively immersed in 10% formaldehyde for 5 min, then ammoniacal silver solution for 5 min; and finally in 8% formaldehyde until the sections became dark brown. Images of slices were captured by the Leica microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the hippocampus with the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, #74804, Germantown, MD, USA). The RNA was used to generate cDNA with the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for qPCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #K1642). Equal amounts of cDNA were used for qPCR analysis using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, #4367659, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cycling conditions for qPCR were established using a 7500 real-time PCR thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, #4367659, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The specific primers used were as follows: lc3 I/II forward 5’-GATGTCCGACTTATTCGAGAGC-3’, lc3 I/II reverse 5’-TTGAGCTGTAAGCGCCTTCTA-3’, p62 forward 5’-TGTGGAACATGGAGGGAAGAG-3’, p62 reverse 5′-TGTGCCTGTGCTGGAACTTTC-3’. gapdh forward 5’-GACCCCTTCATTGACCTCAAC-3’, gapdh reverse 5’-TGGACTGTGGTCATGAGTCC-3’. The relative expression levels were calculated using the following equation: 2−[Δ threshold cycle number (Ct) sample − ΔCT control] [18].

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

The hippocampus was lysed in IP buffer A (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 2 mmol/L EGTA, 5 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 100 μmol/L sodium vanadate, 1 mmol/L DTT, 50 mmol/L KF, 5 mol/L iodoacetamide, and a protease inhibitor mixture), and then incubated with 10 μg antibody against cPKCγ or IgG in a spin column from the Protein G Immunoprecipitation Kit (IP50, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) overnight with constant rotation. After incubation, 30 μl washed Protein G agarose was transferred to the lysate and incubated overnight with constant rotation. Finally, the immunoprecipitates were resolved in loading buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Statistical Analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism version 7.0 was used for data analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted by using one-way or two-way analysis of variance followed by all pairwise multiple comparison procedures using the Bonferroni test. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the correlations between P-Ser214 Tau and escape latency (day 7). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

cPKCγ Deficiency Aggravates the Spatial Learning and Memory Impairment of T1DM Mice

As shown in Fig. 1A, the weight of the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group (24.68 ± 1.08 g) was lower than that of the CON+ cPKCγ+/+ group (32.22 ± 0.87 g) at 8 weeks after STZ injection. After STZ injection, the blood glucose of the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group increased rapidly with a mean value of 27.63 ± 3.08 mmol/L at 8 weeks (Fig. 1B). The weight and blood glucose in the CON+ cPKCγ−/− group (32.18 ± 1.89 g and 4.02 ± 0.52 mmol/L ) did not change compared with that in the CON+ cPKCγ+/+ group (32.22 ± 0.87 g and 4.68 ± 0.48 mmol/L). There was no significant difference in body weight and blood glucose between the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice and the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice. The above results indicated that cPKCγ did not affect the body weight and blood glucose of mice.

To explore the role of cPKCγ in learning and memory, the MWM test was carried out at 8 weeks after STZ injection. As shown in Figure 1C, there was no significant difference in latency between the CON+ cPKCγ+/+ and CON+ cPKCγ−/− groups. On days 3, 4, and 5, the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice took more time to find the hidden platform than the CON mice (Fig. 1C). Compared with the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice, T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice had longer escape latency (Fig. 1C).

On day 6, the platform was removed to evaluate the search behavior of mice. The CON + cPKCγ+/+ and CON+ cPKCγ−/− mice mainly swam in the target quadrant (quadrant II) to find the platform. The T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice swam in random circles throughout the pool and the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice spent longer swimming along the pool wall (Fig. 1E). The percentage of time spent in the target quadrant in the probe trial was markedly lower for the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice than for the CON mice (Fig. 1D). Besides, the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice spent less time near the previous platform location than the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice during the probe trial (Fig. 1D).

On day 7, the hidden platform was put back in its original position. The CON + cPKCγ+/+ and CON+ cPKCγ−/− mice swam directly to the hidden platform, while the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice swam randomly. The T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice took significantly longer than CON mice to locate the hidden platform (Fig. 1F, H). Moreover, the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice performed worse than the cPKCγ+/+ diabetic mice (Fig. 1F, H).

As the visual and sensorimotor ability of a mouse could affect the reliability of the MWM test, the visible platform test was carried out on day 8. There was no significant difference in the escape latency and average swimming speed among the four groups, suggesting that T1DM and cPKCγ deficiency did not affect the visual and sensorimotor abilities of mice (Fig. 1G, I). Taken together, our findings suggested that cPKCγ deficiency did not affect the cognitive function of normal mice but aggravated the spatial learning and memory impairment of diabetic mice.

cPKCγ Deficiency Increases Tau Phosphorylation and Neurofibrillary Tangles in the Hippocampus of T1DM Mice and High Glucose-treated Neurons

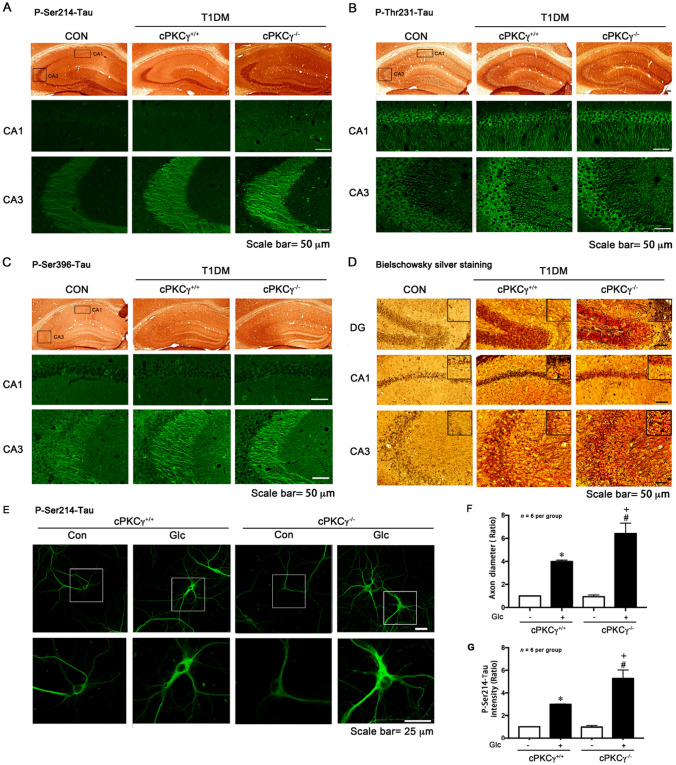

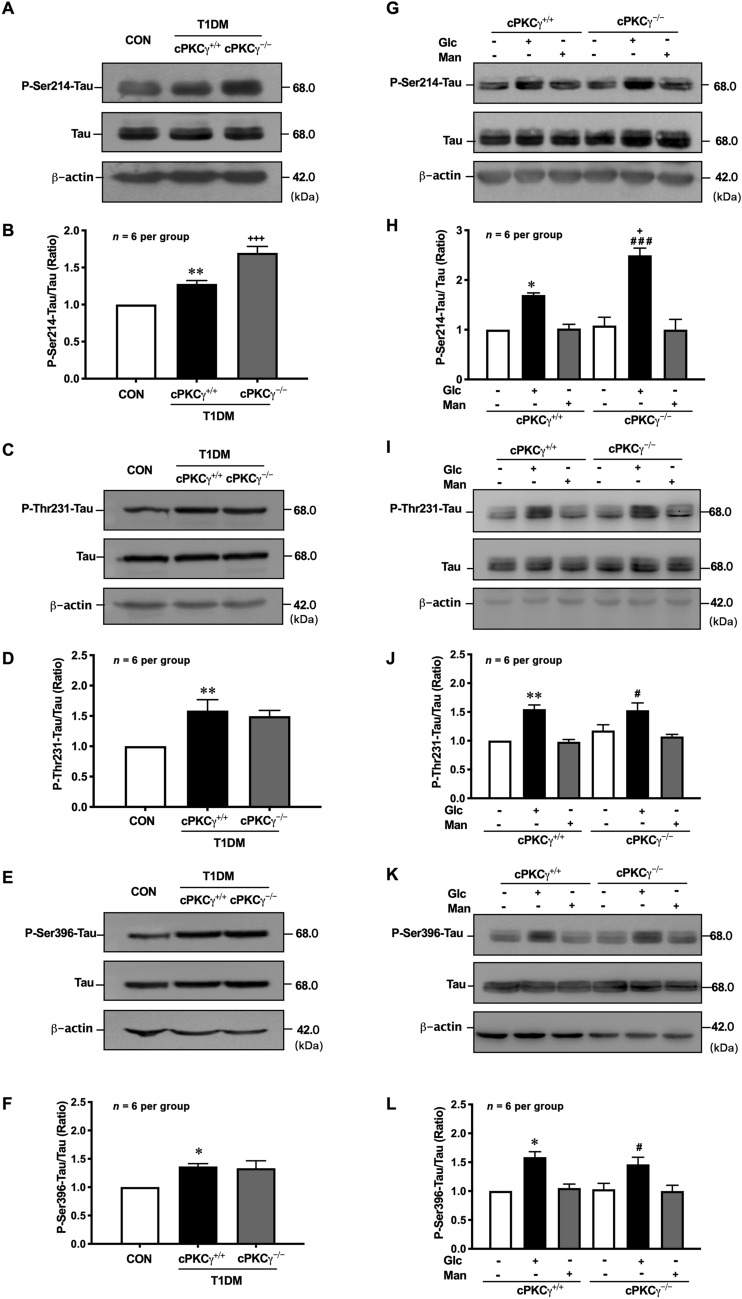

Bielschowsky’s silver staining showed a significant accumulation of argentophilic substances in the hippocampus of T1DM mice, and cPKCγ gene knockout further enhanced the staining (Fig. 3D). NFTs are mainly composed of hyperphosphorylated Tau, which is incompetent in binding and stabilizing microtubules and leads to disruption of neuronal transport and eventual degeneration of the affected neurons. To determine the effect of cPKCγ on phosphorylation of Tau in T1DM, we measured the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, P-Thr231-Tau, and P-Ser396-Tau in vivo and in vitro by Western blot analysis. The level of total Tau was unchanged in all groups. The Tau phosphorylated at Ser214, Thr231, and Ser396 increased prominently in the hippocampus at 8 weeks after STZ injection (Fig. 2 A–F). Compared with cPKCγ+/+ diabetic mice, cPKCγ−/− diabetic mice had significantly elevated P-Ser214-Tau, while there was no significant difference in the level of P-Thr231-Tau or P-Ser396-Tau (Fig. 2 A–F). High glucose treatment significantly increased the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, P-Thr231-Tau, and P-Ser396-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons, whereas mannitol treatment, the control for osmotic pressure, did not affect Tau phosphorylation at the three sites (Fig. 2 G–L). The cPKCγ deficiency further enhanced the high glucose-induced hyperphosphorylated Tau at Ser214, rather than Thr231 and Ser396 (Fig. 2 G–L).

Fig. 3.

cPKCγ deficiency increases Tau phosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. A–C Representative images of immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence showing the distribution of P-Ser214-Tau, P-Thr231-Tau, and P-Ser396-Tau in the hippocampus. D Representative images of Bielschowsky’s silver staining showing neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus. E Representative images of immunofluorescence showing the distribution of P-Ser214-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. F, G Quantitative analysis of the intensity of P-Ser214-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons and P-Ser214-Tau in axonal diameter distributions in axon initial segment. *P < 0.05 vs Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons. #P < 0.05 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. +P < 0.05 vs Glc group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons. Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L); Man: mannitol (75 mmol/L).

Fig. 2.

cPKCγ deficiency increases Tau phosphorylation in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. A, B Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis of showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau in the hippocampus. C, D Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of P-Thr231-Tau in the hippocampus. E, F Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of P-Ser396-Tau in the hippocampus. G, H Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. I, J Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of P-Thr231-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. K, L Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of P-Ser396-Tau in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs CON group (in vivo) or Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. + P < 0.05, +++P < 0.001 vs T1DM+ cPKCγ+/+ group (in vivo) or Glc group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L); Man: mannitol (75 mmol/L).

A similar trend of the alterations in Tau phosphorylation was also found by immunocytochemistry and immunofluorescence staining. We found that the intensity of P-Ser214-Tau, P-Ser396-Tau, and P-Thr231-Tau was significantly increased in the CA3 region of the hippocampus in T1DM mice compared with that in CON mice (Fig. 3A–C). Furthermore, cPKCγ gene knockout only increased the intensity of P-Ser214-Tau in CA3 of T1DM mice (Fig. 3A). High glucose treatment significantly increased the relative intensity of P-Ser214-Tau in primary cultured neurons (Fig. 3E, F). Then we measured the P-Ser214-Tau in axonal diameter distributions in the axon initial segment. We found that high glucose treatment remarkably increased the P-Ser214-Tau in the axon initial segment, which indicated that axon structure and function might be damaged (Fig. 3E, G) [19]. Moreover, cPKCγ gene knockout further enhance it (Fig. 3E–G). Taken together, our findings suggested that cPKCγ deficiency increases NFTs induced by Tau hyperphosphorylated at Ser214 in the hippocampus of T1DM.

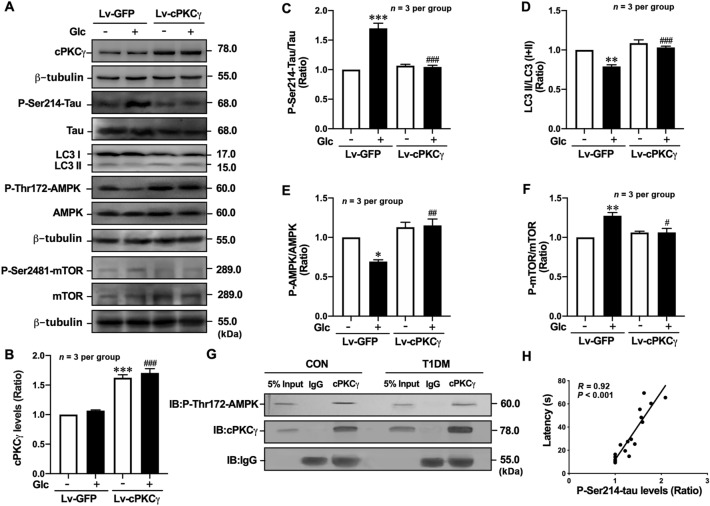

In addition, the correlation between the phosphorylation of Tau at Ser214 in the hippocampus and the escape latency of mice (day 7) was analyzed, and a strong positive correlation was found (R = 0.92, P < 0.001, Fig. 8H). The results suggested that the level of P-Ser214-Tau is closely related to memory impairment in mice.

Fig. 8.

cPKCγ overexpression decreases Tau hyperphosphorylation and alleviates autophagy impairment via the AMPK-mTOR pathway in high-glucose-treated neurons. A Representative Western blots showing the levels of cPKCγ, P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, P-Thr172-AMPK, and P-Ser2448-mTOR in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after Lv-cPKCγ treatment. B–F Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of cPKCγ, P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, P-Thr172-AMPK, and P-Ser2448-mTOR in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after Lv-cPKCγ treatment. G Immunoprecipitation results showing the association between cPKCγ and P-Thr172-AMPK in the hippocampus. H Pearson correlation analysis demonstrating that the levels of P-Ser214-Tau in the hippocampus are positively correlated with escape latency (day 7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs Con of Lv-GFP group neurons. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P< 0.001 vs Glc group of Lv-GFP group neurons. IB: immunoblotting. Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L).

cPKCγ Deficiency does not Affect the Activity of GSK-3β or PP2A in the Hippocampus of T1DM Mice and High Glucose-treated Neurons

GSK-3β and PP2A are responsible for regulating Tau phosphorylation, therefore their activities were measured in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and primary cultured hippocampal neurons with high-glucose treatment. The level of P-Ser9-GSK-3β was significantly increased in the hippocampus of T1DM mice (Fig. 4 A, B) and neurons with high glucose treatment (Fig. 4D, E), but were not altered by cPKCγ gene knockout (Fig. 4A, B, D, E). There was no significant difference in the level of P-Tyr307-PP2A among the three groups in the hippocampus (Fig. 4A, C) and neurons (Fig. 4D, F). These results suggested that GSK-3β and PP2A do not participate in the regulation of Tau hyperphosphorylation at Ser214 by cPKCγ in the hippocampus of T1DM.

Fig. 4.

cPKCγ deficiency does not affect the activity of GSK-3β or PP2A in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. A Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser9-GSK-3β and P-Tyr307-PP2A in the hippocampus. B, C Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser9-GSK-3β and P-Tyr307-PP2A in the hippocampus. D Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser9-GSK-3β and P-Tyr307-PP2A in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. E, F Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser9-GSK-3β and P-Tyr307-PP2A in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. ***P < 0.001 vs CON group (in vivo) or Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). ###P < 0.001 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L).

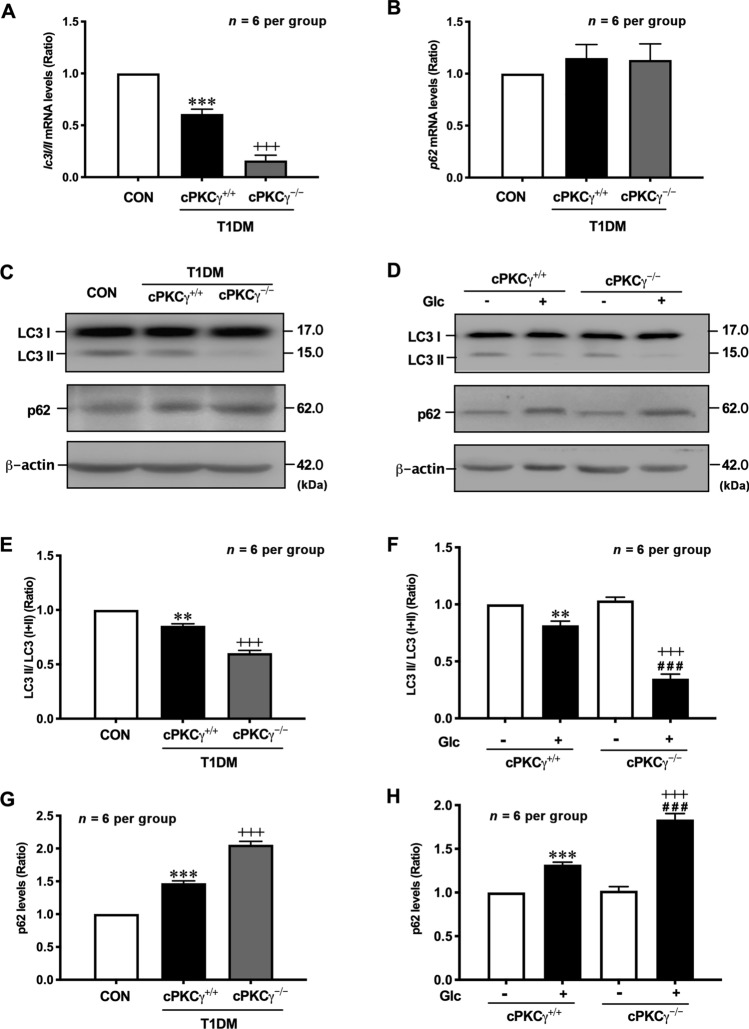

cPKCγ Deficiency Exacerbates Autophagy Impairment in the Hippocampus of T1DM Mice and High Glucose-treated Neurons

Autophagy promotes the degradation of phosphorylated Tau [20], therefore the expression levels of two autophagy-related proteins, LC3 and p62, were evaluated by Western blot and qPCR in vivo and in vitro.

The conversion of LC3 I into LC3 II directly participates in autophagosome formation and is considered an important autophagy marker. Compared with normal mice, the ratio of LC3 II/(I+II) at both the mRNA and protein levels was significantly reduced in the hippocampus of T1DM mice (Fig. 5A, C, E). Compared with the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice, the LC3 II/(I+II) ratio at both levels was further decreased in the hippocampus of T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice (Fig. 5A, C, E). Consistent with the above results, the LC3 II/(I+II) ratio was significantly reduced in the high glucose treated hippocampal neurons and further decreased in cPKCγ−/− neurons (Fig. 5D, F).

Fig. 5.

cPKCγ deficiency exacerbates the autophagy impairment in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. A Statistical results for the lc3 I/II mRNA level in the hippocampus. B Statistics of the p62 mRNA level in the hippocampus. C, E, G Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of LC3 conversion and p62 in the hippocampus. D, F, H Representative Western blots and quantitative analysis showing the levels of LC3 conversion and p62 in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs CON group (in vivo) or Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). ###P < 0.001 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. +++P < 0.001 vs T1DM+ cPKCγ+/+ group (in vivo) or Glc group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L).

During autophagic flux, p62 is an adaptor of LC3 II and serves as a substrate for autophagic degradation. The level of p62 protein was significantly increased in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and further enhanced in the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice (Fig. 5C, G). In parallel with the above results, the expression of p62 was significantly increased in the high glucose-treated hippocampal neurons and further enhanced in the cPKCγ−/− neurons (Fig. 5 D, H). Therefore, these results suggested that cPKCγ deficiency exacerbates the autophagy impairment in the hippocampus of T1DM mice.

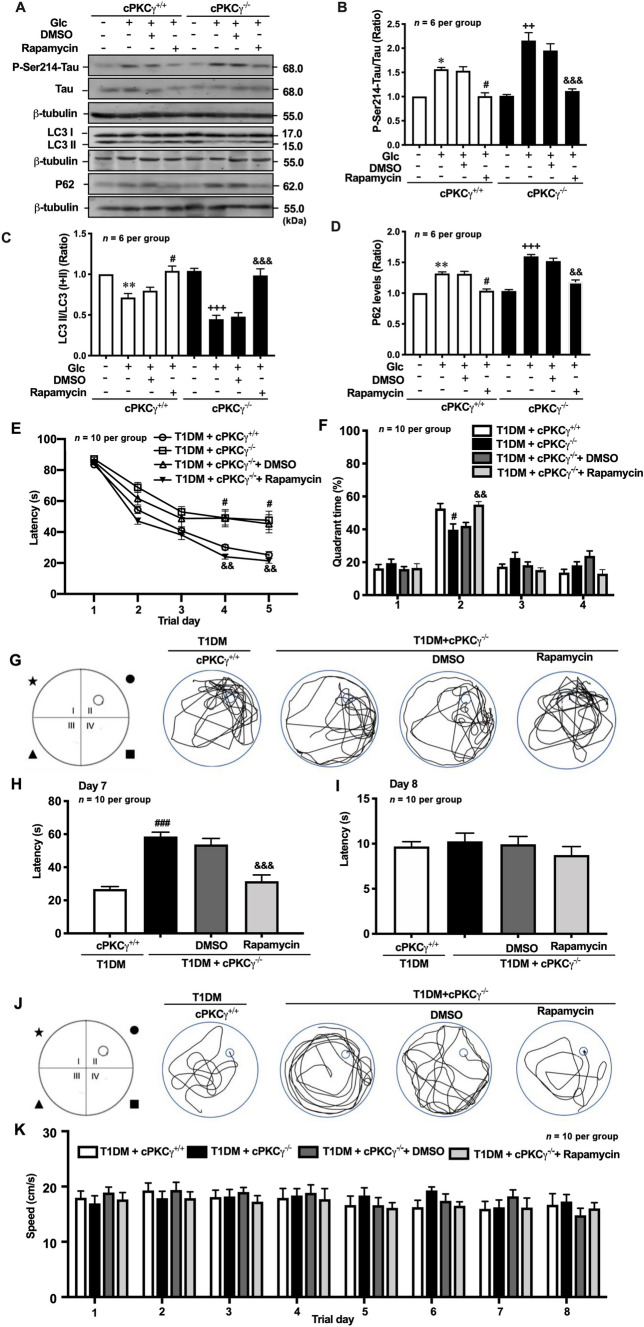

Activation of Autophagy Alleviates the Cognitive Impairment Induced by cPKCγ Deficiency in T1DM Mice

To explore the role of autophagy in the spatial learning and memory impairment of T1DM mice, rapamycin was intracerebroventricularly injected into their right lateral ventricle. On days 4 and 5, the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice took more time to find the hidden platform than the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice (Fig. 6E). Compared with T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + DMSO mice, rapamycin treatment reversed the increased latency induced by cPKCγ deficiency (Fig. 6E). As shown in Fig. 6G, the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice swam in random circles throughout the pool and the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− diabetic mice spent longer swimming along the pool wall. Compared with T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + DMSO mice, T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + Rapamycin mice spent more time in the target quadrant (quadrant II) to seek the platform. The percentage of time spent in the target quadrant in the probe trial was markedly lower for the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice than for the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice (Fig. 6F). Besides, the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + Rapamycin mice stayed significantly longer in the target quadrant than the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + DMSO mice (Fig. 6F). On day 8, the T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ mice took longer to find the hidden platform than the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice (Fig. 6H, J). Moreover, the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + Rapamycin mice performed better than the T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + DMSO mice (Fig. 6H, J). There was no significant difference in the escape latency and average swimming speed among the four groups in the visible platform test (Fig. 6I, K). Our results indicated that the activation of autophagy greatly improves the cognitive impairment induced by cPKCγ deficiency in T1DM mice.

Fig. 6.

Activation of autophagy reduces hyperphosphorylated Tau and alleviates the cognitive impairment induced by cPKCγ deficiency. A Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, and p62 in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after rapamycin treatment. B–D Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, and p62 in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after rapamycin treatment. E The escape latency in each group during 5 consecutive days of the learning process. F, G Statistics of the time spent in the target quadrant and a graph of the swim path measured after removing the platform on day 6. H, J Statistics of the escape latency and a graph of the swim path of each group after resetting the platform on day 7. I Statistics of the escape latency of each group in the visible test on day 8. K Statistic of speed in each group every day. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons. #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs Glc + DMSO group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro) or T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group (in vivo). ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001 vs Glc + DMSO group of cPKCγ−/− neurons (in vitro) or T1DM + cPKCγ−/− + DMSO group (in vivo). Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L).

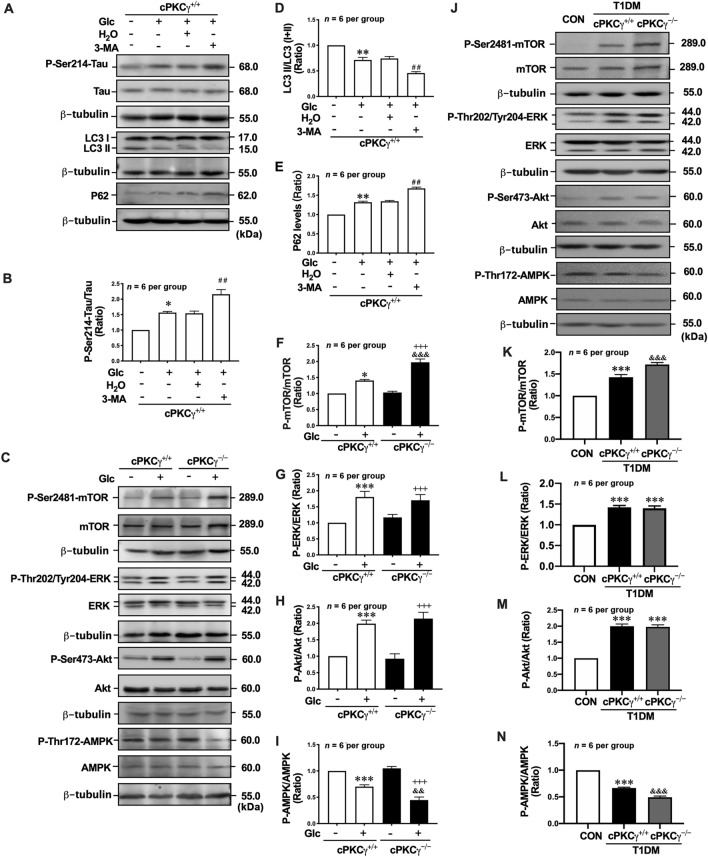

cPKCγ Deficiency Exacerbates Autophagy Impairment via the AMPK-mTOR Pathway in the Hippocampus of T1DM Mice and High Glucose-treated Neurons

To explore the role of autophagy in the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated Tau, 3-MA was applied to the neurons treated with high glucose. 3-MA, an inhibitor of class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), has been widely used to suppress autophagy. We found that 3-MA treatment significantly decreased the ratio of LC3 II/(I+II) (Fig. 7A, D) and increased the level of p62 in cPKCγ+/+ neurons exposed to high glucose (Fig. 7A, E). Meanwhile, 3-MA treatment significantly increased the P-Ser214-Tau levels (Fig. 7A, B). These results suggested that autophagy promotes the degradation of P-Ser214-Tau in neurons exposed to high glucose.

Fig. 7.

cPKCγ deficiency exacerbates the autophagy impairment via the AMPK-mTOR pathway in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. A Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, and p62 in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after 3-MA treatment. B, D, E Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser214-Tau, LC3 conversion, and p62 in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons after 3-MA treatment. C Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, P-Ser473-Akt, and P-Thr172-AMPK in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons. F–I Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, P-Ser473-Akt, and P-Thr172-AMPK in high-glucose-treated primary cultured hippocampal neurons. J Representative Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, P-Ser473-Akt, and P-Thr172-AMPK in the hippocampus of T1DM mice. K–N Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the levels of P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, P-Ser473-Akt, and P-Thr172-AMPK in the hippocampus of T1DM mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs CON group (in vivo) or Con group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). ##P < 0.01 vs Glc + H2O group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons. +++P < 0.001 vs Con group of cPKCγ−/− neurons. &&P < 0.01, &&&P < 0.001 vs T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ group (in vivo) or Glc group of cPKCγ+/+ neurons (in vitro). Glc: glucose (75 mmol/L).

Since activated mTOR suppresses autophagy induction, we measured the phosphorylation of mTOR as an early marker of autophagy induction in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. The results showed that the level of P-Ser2448-mTOR was significantly increased in neurons treated with high glucose. cPKCγ gene knockout further enhanced the high glucose-induced mTOR phosphorylation (Fig 7C, F). Rapamycin is a commonly used autophagy activator that inhibits the activation of mTOR. We found that the levels of LC3 II/(I+II) and p62 were reversed by rapamycin treatment both in high-glucose-treated cPKCγ+/+ and cPKCγ−/− neurons (Fig. 6A, C, D). Meanwhile, rapamycin reversed the increase of P-Se214-Tau induced by high glucose in cPKCγ+/+ and cPKCγ−/− neurons (Fig. 6A, B).

Since activated PI3K/Akt, ERK, and AMPK are upstream modulators of mTOR activity, we measured their phosphorylation levels in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. The levels of P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK and P-Ser473-Akt were significantly increased in high-glucose-treated neurons (Fig. 7C, G, H). However, cPKCγ gene knockout did not affect the levels of P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK and P-Ser473-Akt. The levels of P-Thr172-AMPK were significantly decreased in high-glucose-treated neurons, and cPKCγ gene knockout further decreased the phosphorylation levels of AMPK (Fig. 7C, I).

A similar trend in the levels of P-Ser2448-mTOR, P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK, P-Ser473-Akt, and P-Thr172-AMPK were also found in the hippocampus of T1DM + cPKCγ+/+ and T1DM + cPKCγ−/− mice (Fig. 7J, K–N). In addition, the IP analysis demonstrated that cPKCγ and P-Thr172-AMPK reciprocally immunoprecipitate in the hippocampus of CON mice, and T1DM decreased their interactions (Fig. 8G).

In order to further confirm that cPKCγ regulates autophagy and Tau hyperphosphorylation through the AMPK-mTOR pathway, Lv-cPKCγ was used to overexpress cPKCγ in hippocampal neurons. Fig. 8 A and B show that Lv-cPKCγ successfully increased the cPKCγ levels in hippocampal neurons. Lv-cPKCγ treatment significantly increased the ratio of LC3 II/(I+II), markedly decreased the levels of P-Ser214-Tau and P-Ser2448-mTOR, and noticeably increased the levels of P-Thr172-AMPK in the high-glucose-treated hippocampal neurons (Fig. 8A, C–F).

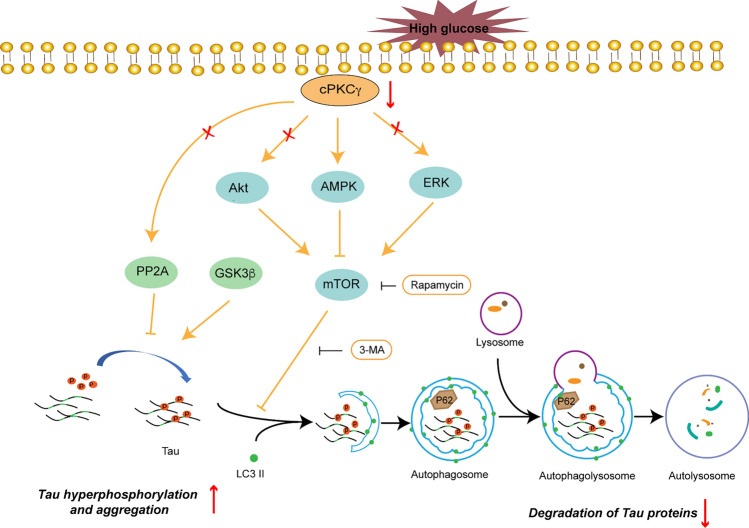

The above results suggested that cPKCγ deficiency reduced AMPK activity, rather than Akt or ERK activity, in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. The decrease of AMPK activity increased the level of P-Ser2448-mTOR, which exacerbated the autophagy impairment. Then autophagy impairment subsequently increased the level of P-Ser214-Tau (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Schematic of the effect of cPKCγ on autophagy through the AMPK-mTOR pathway in the hippocampus of T1DM mice. High glucose induces the hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser214 in the hippocampus and results in the cognitive dysfunction of T1DM mice. The decreased cPKCγ activity caused by T1DM results in autophagy impairment through the AMPK-mTOR pathway, while it does not affect the activity of GSK-3β or PP2A. Downregulated autophagy inhibits the degradation of phosphorylated Tau at Ser214.

Discussion

NFTs are composed of abnormally hyperphosphorylated and aggregated Tau protein. There are > 80 potential Tau phosphorylation sites in the Tau protein, which may alter the conformation and promote Tau protein aggregation and the disruption of microtubules [21]. The phosphorylation of Tau at different sites has different effects on the dynamic instability of microtubules and the deposition of Tau protein [22]. Hyperphosphorylation of the Tau protein at the Ser214, Ser396, and Thr231 sites has been found in NFTs, which are associated with Alzheimer's disease and other age-related dementias with tauopathy [23]. The phosphorylation of Tau at Ser214 prevails during the early stages of Alzheimer's disease [24]. The Ser214 site containing Ser-Pro motifs is critical for the dynamic instability of microtubules [22]. The phosphorylation of Tau at Thr231 is sufficient to induce microtubule instability that results in disruption of the microtubules and neuron death [25, 26]. Phosphorylation of Tau at the Ser396 site is related to the late stage of tauopathy and is mostly found in NFTs [27]. P-Ser396-Tau destabilizes microtubules, resulting in the degeneration of neurons [28]. In this study, we found that the phosphorylation levels of Ser214, Thr231, and Ser396 were significantly increased and argentophilic substances significantly accumulated in the hippocampus of mice at 8 weeks after STZ injection. High-glucose treatment significantly increased the relative intensity of P-Ser214-Tau in primary cultured neurons. We also found that P-Ser214-Tau was more enriched in the axon initial segment after high-glucose treatment. The phosphorylated Tau is able to damage microtubule dynamics in the axon initial segment [13]. Therefore, our results suggested that high glucose significantly increases tau phosphorylation in hippocampal neurons and affects the structure and function of axons.

PKC directly phosphorylates Tau or indirectly suppresses the phosphorylation of Tau [13]. PKC specifically phosphorylates Ser214 in the proline-rich regions of the Tau protein [24]. PKC strongly phosphorylates Tau at Ser 203 and Ser214 in early-stage R504X mutation knock-in mice (a model of frontotemporal lobar degeneration) [14]. PKC provokes increases in the phosphorylation levels of Tau at Thr231 in high-fat-fed insulin-resistant mice [29]. Other studies have reported that a decrease in PKC activity leads to Alzheimer-like Tau hyperphosphorylation at Ser396, Ser199-202, and Ser404 [32–36]. The contradictory role of PKC on Tau phosphorylation may be attributed to its isoforms. Distinct subtypes of PKC may phosphorylate Tau protein at different sites. cPKCγ belongs to the conventional PKC isoform subfamily and mainly occurs in the neurons of the central nervous system. Our previous studies showed that the activity of cPKCγ is remarkably decreased in the hippocampus at 2 and 8 weeks after STZ injection [9]. In this study, we found that cPKCγ deficiency aggravated the spatial learning and memory impairment of T1DM mice and was accompanied by an increase in the level of phosphorylated Tau at Ser214 without affecting the levels of phosphorylated Tau at Ser396 and Thr231. Our results suggested that cPKCγ indirectly down-regulates the phosphorylation of Tau specifically at Ser214. Studies have demonstrated that Tau phosphorylation at Ser214 potently reduces the affinity of Tau for microtubules and disrupts microtubule binding alone [30]. Therefore, cPKCγ may reduce neurofibrillary tangles by reducing tau hyperphosphorylation at Ser214 in the T1DM brain. P-Ser214-Tau is commonly associated with the early stage of tauopathy and accelerates Tau hyperphosphorylation at multiple sites [26]. Through correlation analysis, we found that the level of P-Ser214-Tau was significantly related to memory impairment in mice. These results suggest that P-Ser214-Tau plays an important role in the cognitive impairment in T1DM mice.

The phosphorylation of Tau is regulated by a balance between protein kinase and phosphatase activities, in which GSK-3β and PP2A are both important enzymes [31]. GSK-3β is a serine/threonine kinase that can phosphorylate Tau at Ser214, Ser396, and Thr231, and it is the substrate of PKC [17, 32, 33]. The activity of GSK-3β is mainly regulated by its phosphorylation at Ser9 that reduces its activity. In this study, we found that cPKCγ gene knockout did not alter the phosphorylation of GSK-3β induced by T1DM or high-glucose treatment in the hippocampus. PP2A is the main phosphatase of Tau protein and its activity is determined by the phosphorylation level of its C-terminal regulatory subunit (PP2Ac) at Tyr307 [34, 35]. Studies have shown that the activity of PP2A can be regulated by PKC-dependent phosphorylation of its regulatory and targeting subunits [36, 37]. However, we found that T1DM and cPKCγ gene knockout did not alter the level of P-Tyr307-PP2A in the hippocampus and neurons. Although PKC can regulate the activity of GSK-3β and PP2A, our results indicated that the cPKCγ isoform does not affect GSK-3β and PP2A activities in the brain of T1DM or high-glucose-treated neurons.

Besides kinase and phosphatase, autophagy also regulates the level of phosphorylated Tau [21, 37]. Autophagy clears Tau phosphorylated at Ser214, Ser199/202, Ser396/404, Ser262 and Thr231 [38–41]. LC3 and p62 are markers for autophagy. LC3 is involved in the formation of autophagosomes and autolysosomes, while p62 is an autophagy substrate degraded by autophagy. Studies have shown that hyperglycemia reduces autophagy. The level of LC3 expression is reduced in the spinal cord of diabetic rats [42]. Decreased LC3 II and increased p62 have been reported in the heart of T1DM rats [33]. The levels of autophagy-related protein (Atg) 4 and LC3 II also decrease in the trigeminal ganglion of STZ-induced T1DM mice [43]. Our findings are in agreement with the above results. In the present study, the ratio of LC3 II/(I+II) was reduced and the p62 level was increased in the hippocampus of T1DM mice and high-glucose-treated neurons. Our results indicated that both autophagosome formation and autophago-lysosomal degradation are impaired in the T1DM brain. Many studies have shown that PKC plays a different regulatory role in autophagy in different systemic diseases [44–46]. In the present study, cPKCγ deficiency significantly decreased the level of autophagy both in high-glucose-treated hippocampal neurons and the hippocampus of T1DM mice. Meanwhile, the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA increased the level of P-Se214-Tau induced by high-glucose in hippocampal neurons. These findings further indicated that autophagy promotes the degradation of phosphorylated Tau, while cPKCγ promotes autophagy in the hippocampus of T1DM mice.

mTOR is known as a key negative regulator of autophagy through direct phosphorylation of unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (Ulk1) and Atg13 [47, 48]. It has been reported that cPKCγ mediates autophagy through the mTOR pathway in ischemic injuries of mice and neurons [15, 49, 50]. In agreement with the above research, we also showed that the phosphorylation level of mTOR was significantly increased in high-glucose-treated neurons and cPKCγ deficiency further increased the phosphorylation levels of mTOR. We further found that an mTOR inhibitor increased the level of autophagy and decreased the level of P-Se214-Tau induced by high-glucose in hippocampal neurons.

Akt, ERK and AMPK signal pathways are the main upstream regulatory factors of mTOR in autophagy. Akt is crucial downstream of the PI3K signal and phosphorylates mTOR [51]. ERK positively regulates mTOR phosphorylation and inhibits autophagic flux. AMPK is a major activator of autophagy and inhibits the activation of mTOR [52]. In this study, we found that cPKCγ gene knockout did not affect the levels of P-Ser473-Akt and P-Thr202/Tyr204-ERK in high-glucose-treated primary neurons, while the phosphorylation level of AMPK was further decreased by cPKCγ deficiency, suggesting that AMPK signaling pathways are involved in autophagy promoted by cPKCγ in glucose-treated neurons.

Conclusion

In summary, our results indicate that cPKCγ promotes autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway, thus reducing the hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser214 induced by T1DM. However, further studies on the mechanism by which cPKCγ regulates the AMPK/mTOR pathway in the brain of T1DM are required.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7192016 and 7222064), the Scientific Research Common Program of Beijing Municipal Commission of Education (KM201910025029), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071539 and 31972911).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Jiayin Zheng and Yue Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Junfa Li, Email: junfali@ccmu.edu.cn.

Li Zhao, Email: zhaoli@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. 2. classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care 2018, 41: S13–S27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ohmann S, Popow C, Rami B, König M, Blaas S, Fliri C, et al. Cognitive functions and glycemic control in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Psychol Med. 2010;40:95–103. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W, Huang E, Gao SJ. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairments: A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:29–36. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarado-Rodríguez FJ, Romo-Vázquez R, Gallardo-Moreno GB, Vélez-Pérez H, González-Garrido AA. Type-1 diabetes shapes working memory processing strategies. Neurophysiol Clin. 2019;49:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie HY, Xu F, Li Y, Zeng ZB, Zhang R, Xu HJ, et al. Increases in PKC gamma expression in trigeminal spinal nucleus is associated with orofacial thermal hyperalgesia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J Chem Neuroanat. 2015;63:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amadio M, Bucolo C, Leggio GM, Drago F, Govoni S, Pascale A. The PKCbeta/HuR/VEGF pathway in diabetic retinopathy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou HC, Liu J, Ren LY, Liu W, Xing Q, Men LL, et al. Relationship between[corrected]spatial memory in diabetic rats and protein kinase Cγ, caveolin-1 in the Hippocampus and neuroprotective effect of catalpol. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:916–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng JY, Wang Y, Han S, Luo YL, Sun XL, Zhu N, et al. Identification of protein kinase C isoforms involved in type 1 diabetic encephalopathy in mice. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:8431249. doi: 10.1155/2018/8431249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustke N, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Domains of tau protein and interactions with microtubules. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9511–9522. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forner S, Baglietto-Vargas D, Martini AC, Trujillo-Estrada L, LaFerla FM. Synaptic impairment in Alzheimer's disease: A dysregulated symphony. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdile G, Keane KN, Cruzat VF, Medic S, Sabale M, Rowles J, et al. Inflammation and oxidative stress: The molecular connectivity between insulin resistance, obesity, and Alzheimer's disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:105828. doi: 10.1155/2015/105828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isagawa T, Mukai H, Oishi K, Taniguchi T, Hasegawa H, Kawamata T, et al. Dual effects of PKNα and protein kinase C on phosphorylation of tau protein by glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:209–212. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita K, Chen XG, Homma H, Tagawa K, Amano M, Saito A, et al. Targeting Tyro3 ameliorates a model of PGRN-mutant FTLD-TDP via tau-mediated synaptic pathology. Nat Commun. 2018;9:433. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang D, Han S, Wang SZ, Luo YL, Zhao L, Li JF. cPKCγ-mediated down-regulation of UCHL1 alleviates ischaemic neuronal injuries by decreasing autophagy via ERK-mTOR pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3641–3657. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao L, Chu CB, Li JF, Yang YT, Niu SQ, Qin W, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 reduces acetylcholine level in striatum via disturbing cellular distribution of choline acetyltransferase in cholinergic interneurons in rats. Neuroscience. 2013;255:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Tian Q, Liu EJ, Zhao L, Song J, Liu XN, et al. Activation of GSK-3 disrupts cholinergic homoeostasis in nucleus basalis of meynert and frontal cortex of rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3515–3528. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zempel H, Mandelkow E. Mechanisms of axonal sorting of tau and influence of the axon initial segment on tau cell polarity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1184:69–77. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9358-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MJ, Lee JH, Rubinsztein DC. Tau degradation: The ubiquitin-proteasome system versus the autophagy-lysosome system. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;105:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX. Tau and neurodegenerative disease: The story so far. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:15–27. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drewes G, Ebneth A, Mandelkow EM. MAPs, MARKs and microtubule dynamics. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:307–311. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morishima-Kawashima M, Hasegawa M, Takio K, Suzuki M, Yoshida H, Titani K, et al. Proline-directed and non-proline-directed phosphorylation of PHF-tau. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:823–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regalado-Reyes M, Furcila D, Hernández F, Ávila J, DeFelipe J, León-Espinosa G. Phospho-tau changes in the human CA1 during Alzheimer's disease progression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69:277–288. doi: 10.3233/JAD-181263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alonso AD, di Clerico J, Li B, Corbo CP, Alaniz ME, Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Phosphorylation of tau at Thr212, Thr231, and Ser262 combined causes neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30851–30860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luna-Muñoz J, García-Sierra F, Falcón V, Menéndez I, Chávez-Macías L, Mena R. Regional conformational change involving phosphorylation of tau protein at the Thr231, precedes the structural change detected by Alz-50 antibody in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:29–41. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura T, Ono T, Takamatsu J, Yamamoto H, Ikegami K, Kondo A, et al. Sequential changes of tau-site-specific phosphorylation during development of paired helical filaments. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1996;7:177–181. doi: 10.1159/000106875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bramblett GT, Goedert M, Jakes R, Merrick SE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Abnormal tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in Alzheimer's disease recapitulates development and contributes to reduced microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;10:1089–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sajan MP, Hansen BC, Higgs MG, Kahn CR, Braun U, Leitges M, et al. Atypical PKC, PKCλ/ι, activates β-secretase and increases Aβ1-40/42 and phospho-tau in mouse brain and isolated neuronal cells, and may link hyperinsulinemia and other aPKC activators to development of pathological and memory abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;61:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Illenberger S, Zheng-Fischhöfer Q, Preuss U, Stamer K, Baumann K, Trinczek B, et al. The endogenous and cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of tau protein in living cells: Implications for Alzheimer's disease. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1495–1512. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin L, Latypova X, Wilson CM, Magnaudeix A, Perrin ML, Yardin C, et al. Tau protein kinases: Involvement in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson GVW, Stoothoff WH. Tau phosphorylation in neuronal cell function and dysfunction. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5721–5729. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang DW, He Y, Ye XD, Cai Y, Xu JD, Zhang LQ, et al. Activation of autophagy inhibits nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activation and attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetic rats. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taleski G, Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A and tau: An orchestrated ‘pas de deux’. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:1079–1095. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YP, Mandelkow E. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:22–35. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2015.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirchhefer U, Heinick A, König S, Kristensen T, Müller FU, Seidl MD, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A is regulated by protein kinase cα (PKCα)-dependent phosphorylation of its targeting subunit B56α at Ser41. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:163–176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.507996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ricciarelli R, Azzi A. Regulation of recombinant PKC alpha activity by protein phosphatase 1 and protein phosphatase 2A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;355:197–200. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YD, Su Y, Wang JJ, Sun SG, Wang T, Qiao X, et al. Rapamycin decreases tau phosphorylation at Ser214 through regulation of cAMP-dependent kinase. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiu LF, Ng G, Tan EK, Liao P, Kandiah N, Zeng L. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion enhances Tau hyperphosphorylation and reduces autophagy in Alzheimer's disease mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23964. doi: 10.1038/srep23964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang YH, Zhou YJ, Ma H, Cao XZ, Li Z, Chen FS, et al. Autophagy dysfunction and mTOR hyperactivation is involved in surgery: Induced behavioral deficits in aged C57BL/6J mice. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:331–344. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiku T, Hayashishita M, Saito T, Oka M, Shinno K, Ohtake Y, et al. S6K/p70S6K1 protects against tau-mediated neurodegeneration by decreasing the level of tau phosphorylated at Ser262 in a Drosophila model of tauopathy. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;71:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu K, Yang YC, Zhou F, Xiao YD, Shi LW. Inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway promotes autophagy and relieves hyperalgesia in diabetic rats. Neuroreport. 2020;31:644–649. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu JZ, Hu XY, Kan T. miR-34c participates in diabetic corneal neuropathy via regulation of autophagy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60:16–25. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi SW, Song JK, Yim YS, Yun HG, Chun KH. Glucose deprivation triggers protein kinase C-dependent β-catenin proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:9863–9873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.606756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gauron MC, Newton AC, Colombo MI. PKCα is recruited to Staphylococcus aureus-Containing phagosomes and impairs bacterial replication by inhibition of autophagy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:662987. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.662987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kudo Y, Sugimoto M, Arias E, Kasashima H, Cordes T, Linares JF, et al. PKCλ/ι loss induces autophagy, oxidative phosphorylation, and NRF2 to promote liver cancer progression. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:247–262.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyshlovoy SA. Blue-print autophagy in 2020: A critical review. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:E482. doi: 10.3390/md18090482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang T, Yu QJ, Li JJ, Hu B, Zhao Q, Ma CM, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of fumarase maintains tumour growth under glucose deficiency. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:833–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hua RR, Han S, Zhang N, Dai QQ, Liu T, Li JF. cPKCγ-modulated sequential reactivation of mTOR inhibited autophagic flux in neurons exposed to oxygen glucose deprivation/reperfusion. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1380. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei HP, Li Y, Han S, Liu SQ, Zhang N, Zhao L, et al. cPKCγ-modulated autophagy in neurons alleviates ischemic injury in brain of mice with ischemic stroke through Akt-mTOR pathway. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7:497–511. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu F, Na LX, Li YF, Chen LJ. Retraction Note to: Roles of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathways in neurodegenerative diseases and tumours. Cell Biosci. 2021;11:157. doi: 10.1186/s13578-021-00667-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao F, Zhang M, Chen L. 5'-Monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) improves autophagic activity in diabetes and diabetic complications. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]