The accumulation of extracellular amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in the brain is one of the primary pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. Several factors contribute to the formation and spread of Aβ, including microglia [1, 2]. Microglia, the primary resident macrophages in the central nervous system, play a vital role in brain development, homeostasis, and neurodegeneration [3, 4]. Under normal conditions, microglia are quiescent and involved in the active surveillance of the microenvironment. However, under pathological conditions (e.g., neurodegenerative disease and brain injury), microglia are activated from a ramified to an amoeboid morphology [1]. In the early stages of AD, Aβ accumulation initiates microglial activation to clear Aβ through phagocytosis [5]. During this stage, microglial activation works as a neuroprotective response against AD pathology [6]. However, the increasing accumulation of Aβ impairs microglial phagocytic ability to removing Aβ and elevates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that accelerate the progression of plaque pathology [1]. Furthermore, several microglia-mediated processes are involved in the Aβ seeding and growth of amyloid plaques [7, 8]. However, the cell-mediated mechanism underlying Aβ propagation and the role of microglia in this process remain elusive.

In a recent study, d’Errico et al. hypothesized that microglia play a crucial role in the propagation of Aβ from an affected brain region into unaffected areas [9]. They first performed transplantation experiments to measure Aβ propagation using embryonic neuronal cells as donors and 5xFAD transgenic mice as recipients. Consistent with a previous study [10], they found that Aβ from the 5xFAD transgenic mice could be transported into WT grafts. Moreover, the Aβ plaques in the WT grafts increased over time, confirming the propagation of Aβ from pathological regions into unaffected brain tissue. Next, using Thy1-GFP/5xFAD mice as the host animals, the authors evaluated whether APP/Aβ is anterogradely transported along axons from the AD host tissue to WT grafts. Notably, they found only a few axons invaded the WT graft, suggesting the neurons are not involved in Aβ propagation from AD tissue to WT grafts.

d’Errico et al. next asked whether host microglia in AD mice contribute to Aβ propagation. They transplanted neuronal cells from WT mice into the Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD mice to answer this question. Interestingly, they found the invasion of microglia into the WT graft was prominent, and Aβ was found within the microglia or located nearby, indicating microglia are involved in Aβ propagation. To further confirm that the microglia in the WT grafts were indeed from recipient tissue rather than donor-derived, d’Errico et al. measured whether microglia were present in the cortical cell suspension used for transplantation. Intriguingly, no astrocytes or microglia were detected in the suspension before transplantation, whereas microglia were detected in the grafts at 4 and 16 weeks after transplantation. In addition, transplantation experiments using Cx3Cr1-GFP mice (donors) and HexbtdTomato (recipients) only found tdTomato-marked microglia and no GFP-marked microglia within the grafts, suggesting that microglia in the WT grafts were transported from the host tissue. Notably, d’Errico et al. also confirmed that these microglia were from the microglia resident in the host brain tissue rather than peripheral monocytes.

As a professional phagocyte in the central nervous system [1], microglia from the transgenic host tissue to the WT grafts promoted the speculation that microglial phagocytosis contributes to the propagation of Aβ and microglial function affects the accumulation of Aβ in WT grafts. Therefore, the authors then asked whether the compromised capacity of microglial phagocytosis affects Aβ propagation from transgenic AD host animals to WT grafts. The authors found that both the Aβ-containing microglia and Aβ content per microglial cell were reduced in elderly mice compared with the microglia from adult mice. Next, after administration of methoxy‐XO4 to adult and old WT and 5xFAD mice, they confirmed the decreased phagocytic capacity of microglia in vivo, indicating the compromised microglial Aβ phagocytosis in old 5xFAD mice. Interestingly, using young or old AD mice as recipients, the authors found that Aβ propagation was more prominent in young host mice, suggesting that microglial phagocytosis contributes to the propagation of Aβ into WT grafts.

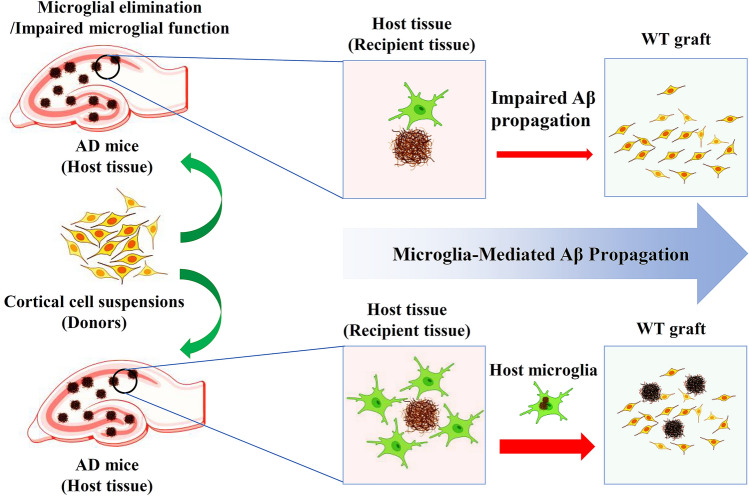

To further validate their finding that microglia contribute to Aβ propagation, Irf8−/−/Cx3cr1+/− transgenic mice characterized by impaired microglial process motility and reduced and shorter branches were generated as host mice. As expected, both microglia and amyloid deposits in the grafts were significantly decreased. Furthermore, they also performed the transplantation experiments in Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD recipient mice after deleting microglia using BLZ945. Consistent with the findings from Irf8−/−/Cx3cr1+/− transgenic mice, the elimination of microglia significantly alleviated amyloid deposits within the grafts. Moreover, because microglial cells are able to migrate toward the site of brain injury and release inflammatory factors that contribute to the pathological process in multiple brain injuries [11, 12], the authors then analyzed the ability of microglia to spread Aβ after a laser-induced, localized tissue injury. To elucidate this, repetitive two-photon in vivo imaging was applied to Irf8+/+/Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD mice and to Irf8−/−/Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD mice to measure the changes in microglial movement and Aβ plaques after focal tissue injury. As expected, the authors found that Aβ-containing microglia in Irf8+/+/Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD mice moved to the lesion site and formed amyloid plaques. In contrast, the movement of Aβ-containing microglia in Irf8−/−/Cx3cr1+/−/5xFAD mice was not evident. Finally, using co-culture of brain slices, the authors detected the migration of microglia from AD brain slices to WT brain slices, further validating their findings. Taken together, their results confirmed their hypothesis that microglia contribute to Aβ propagation into unaffected brain tissue (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Microglia-mediated Aβ propagation in AD. In AD, microglia work as a carrier of amyloid to deliver Aβ into unaffected brain regions (wild-type neuron graft). Elimination of microglia or impaired microglial function attenuates Aβ propagation and slows plaque growth in the WT graft.

In summary, d’Errico et al. found that microglia mediate Aβ spreading and confirmed that microglial function and mobility are involved in regulating Aβ propagation. Moreover, they found that brain injury not only induces the recruitment of microglia but also sparks the accumulation of amyloid plaques within the lesion. Their study fills a critical gap in our knowledge of microglial function in AD and provides a novel mechanism underlying Aβ propagation. For example, the entorhinal cortex is one of the earliest Aβ-affected brain regions [13]. The accumulation of cortical Aβ first occurs in the entorhinal cortex and then spreads over almost the entire cortex. The findings of this study provide a possible explanation for this process, in which microglia mediate the propagation of Aβ from the entorhinal cortex to other cortical areas. Although d’Errico et al. have made remarkable progress in uncovering the novel function of microglia in AD, several intriguing questions are worth further investigation. First, according to a previous study, microglia can be divided into pro-inflammatory M1-like and anti-inflammatory M2-like phenotypes [11]. The expression of IL-3Rα, the specific receptor for IL-3, in different microglial phenotypes may vary. According to a previous study [14], astrocytic IL-3 and microglial IL-3Rα play a pivotal role in regulating microglial motility and recruitment. At the early stage of AD, the expressions of astrocytic IL-3 and microglial IL-3Rα in different microglia may contribute to the migration of Aβ-bearing microglia from affected tissue to non-affected tissue. Therefore, it would be interesting to elucidate the role of different microglial subtypes in Aβ propagation [11]. Second, because microglia-derived inflammatory cytokines also contribute to Aβ deposition [1], more work is needed to clarify the relationship between inflammatory cytokines and microglia-mediated Aβ propagation in AD. In addition, the immune response induced by transplantation may contribute to microglia-mediated Aβ propagation. It would be helpful to consolidate their conclusion if there is some evidence demonstrating that Aβ-bearing microglia spread to unaffected brain regions under physiological conditions. Third, the authors found astrocytes may only play a minor role in the propagation of Aβ in the grafting model system used in their study. However, it is worth investigating the role of astrocytes in amyloid propagation using other animal model systems. Moreover, their analysis identified three genes (Cybb, Myo5a, and Lyz2) that are differentially expressed within or outside the grafts. Studying the role of these genes in microglia in the grafting model system may further our understanding of microglia-mediated Aβ propagation. Finally, it would be interesting to investigate whether microglia play a similar role in mediating the propagation of other pathological factors in AD or other neurodegenerative diseases. Looking deeper into the mechanisms underlying microglia-mediated Aβ propagation not only can shed light on the pathogenesis and progression of AD but also provides a possible way to slow its progression.

Acknowledgments

This highlight was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100918) and the Sigma Xi Grants in Aid of Research program (G03152021115804390).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Wu CY, Yang LD, Tucker D, Dong Y, Zhu L, Duan R, et al. Beneficial effects of exercise pretreatment in a sporadic Alzheimer's rat model. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:945–956. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro V, Sanchez-Mejias E, Jimenez S, Muñoz-Castro C, Sanchez-Varo R, Davila JC, et al. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: Activated, dysfunctional or degenerative. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:140. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CY, Yang LD, Youngblood H, Liu TCY, Duan R. Microglial SIRPα deletion facilitates synapse loss in preclinical models of neurodegeneration. Neurosci Bull. 2022;38:232–234. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00795-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlen CJ, Friedman BA, Dejanovic B, Sheng M. Microglia in brain development, homeostasis, and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Genet. 2019;53:263–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112618-043515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai AY, McLaurin J. Clearance of amyloid-β peptides by microglia and macrophages: The issue of what, when and where. Future Neurol. 2012;7:165–176. doi: 10.2217/fnl.12.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fakhoury M. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease: Implications for therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:508–518. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666170720095240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler-Waldkirch S, D'Errico P, Sauer JF, Erny D, Savanthrapadian S, Loreth D, et al. Seed-induced Aβ deposition is modulated by microglia under environmental enrichment in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 2018;37:167–182. doi: 10.15252/embj.201797021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baik SH, Kang S, Son SM, Mook-Jung I. Microglia contributes to plaque growth by cell death due to uptake of amyloid β in the brain of Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Glia. 2016;64:2274–2290. doi: 10.1002/glia.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.d’Errico P, Ziegler-Waldkirch S, Aires V, Hoffmann P, Mezö C, Erny D, et al. Microglia contribute to the propagation of Aβ into unaffected brain tissue. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25:20–25. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00951-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espuny-Camacho I, Arranz AM, Fiers M, Snellinx A, Ando K, Munck S, et al. Hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease in stem-cell-derived human neurons transplanted into mouse brain. Neuron. 2017;93:1066–1081.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LD, Dong Y, Wu CY, Youngblood H, Li Y, Zong XM, et al. Effects of prenatal photobiomodulation treatment on neonatal hypoxic ischemia in rat offspring. Theranostics. 2021;11:1269–1294. doi: 10.7150/thno.49672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domercq M, Vázquez-Villoldo N, Matute C. Neurotransmitter signaling in the pathophysiology of microglia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:49. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janelsins MC, Mastrangelo MA, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ. Early correlation of microglial activation with enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression specifically within the entorhinal cortex of triple transgenic Alzheimer's disease mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAlpine CS, Park J, Griciuc A, Kim E, Choi SH, Iwamoto Y, et al. Astrocytic interleukin-3 programs microglia and limits Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2021;595:701–706. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03734-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]