Abstract

The Community Social Paediatrics approach (CSPA) is a comprehensive and personalized approach to care that is becoming more widely used throughout Canada. However, data on its implementation fidelity remain scarce. The purpose of this research was to assess the implementation fidelity of a CSPA established in 2017 in Canada. Data were collected through focus group interviews with the CSPA team using an implementation fidelity grid based on the Dr. Julien Foundation standard accreditation criteria. Results showed that on one hand, administrative and financial management and governance were among those domains with lower ratings. On the other hand, assessment/orientation and follow-up/support had high levels of fidelity of implementation. This research helps to better understand which factors are contributing to varying levels of fidelity of implementation. To reach an increased level of fidelity of implementation, it is recommended that adequate resources be in place.

Keywords: Social pediatrics, fidelity of implementation, community health services, child health services

Introduction

Worldwide, children are one of the most vulnerable populations. Their health, their environment, their safety, and their capacity to live a healthy lifespan are still of concern. Acquiring knowledge and understanding the state of children’s health and how the healthcare system responds and addresses their needs is necessary from a population health perspective.1 Latest data show that 1.2 million Canadian youth are affected by mental illness, while a third have experienced some forms of maltreatment before the age of 15. In addition, about 1.2 million children are living in poverty with around 28 000 of them living in the New Brunswick (NB) province, Canada.2,3

To reach these families, new ways of providing care are warranted. The social pediatrics movement is one approach aimed at improving access to care for families living in vulnerable contexts. This movement was initiated in the 70’s in Europe4 and was further defined and implemented around the world over the years. The Community Social Paediatrics Approach (CSPA) can be defined as preventive, rehabilitative, and curative pediatric services offered in community settings in a holistic and multidisciplinary way, as it considers all dimensions of children’s health and contexts in which they live.5 This approach goes beyond medical lenses as it is a community-integrated healthcare approach for children and their families.

Pioneered by Dr. Julien and Lieber in Canada during the 90’s, its objective is “to promote a compassionate relationship, composed of equal parts listening and empathy, involving the therapist, the child, the family and the community.”6 As explained by Dr. Julien: “We get to know each other. . . establish a connection and then we start working together to find solutions. This is what community social pediatrics is all about.”7 Reports of the CSPA implemented in the Quebec province have shown that their services are offered in an integrated way and are more accessible to vulnerable families.8 There is a considerable level of collaboration between the CSPA and other public and community psychosocial and educational services, which have been perceived as beneficial by these partners and can potentially also facilitate families’ access to multidisciplinary and integrated care.9 Finally, preliminary data are showing that receiving services within CSPA was related to gains in children’s socio-affective development, parental self-efficacy, and parent-child relationship, as well as social support to families.10

Despite theoretical and empirical evidence of the benefits and effectiveness of the CSPA, no known studies have looked at the implementation fidelity of the approach. Empirical research is required to evaluate whether it has been implemented following CSPA guidelines. Fidelity research can contribute to the body of knowledge on differences between clinical practice and the intended model of care, including its application to the context of care while highlighting factors that enable or hinder the implementation.11,12 In addition, “fidelity is a key ingredient for the systematic implementation of evidence-based interventions in community settings,” providing an avenue for monitoring how the program is offered in different settings and how staff can adapt their practices or undergo further training to improve the implementation fidelity of their program.12

The aim of this paper is therefore to present the results of the first stage of the fidelity assessment of the CSPA implementation in 2 small, rural communities in the southeast region of NB, Canada. Since 2017, the CSPA has been piloted in these 2 communities by a multidisciplinary team. The CSPA team’s objective is to capitalize on the child’s and family’s strengths, as well as to collaboratively work with various community resources to enhance therapeutic uptake and continuity of care.

Methods

Design

The present convergent mixed-methods case study explores a contemporary bounded system within a CSPA to care in NB, Canada.13 The CSPA is being implemented in 2 rural, francophone communities of the province (a village of approximately 3 000 people, and part of a county of approximately 30 000 people). This study applies a rubrics-based rating system using a focus group to measure the implementation fidelity of a CSPA.14

To evaluate the fidelity of the approach, a scale was developed through an iterative process in collaboration with key informants from the CSPA center. The scale was based on the Dr. Julien Foundation’s standard accreditation document, which is used by the Foundation as a continuous improvement mechanism.15 Key components of the model were identified and served as fidelity criteria. Each criterion was then carefully reviewed, adapted, and added to the fidelity scale, as recommended by Mowbray et al.16 Anchors for scores on a four-point rating scale were specified for each criterion. The final scale comprises the following 8 domains, and each includes a set of individual criteria corresponding to the Dr Julien Foundation’s accreditation criteria: (1) Access services (eg, reach of children in vulnerable situations and physical proximity; 22 criteria), (2) Evaluation/Orientation (eg, shared leadership with the family and identification of the sources of toxic stress; 15 criteria), (3) Follow-up/support (for example, flexible care, relationship of trust with the family; 12 criteria), (4) Innovation/Change of practices (for example, integration of evidence and research recommendations into practices; 8 criteria), (5) Rights of the child and advocacy (for example, identification of the needs related to the violated rights of children, and defense of children’s rights; 4 criteria), (6) Human capital (eg, following the training and support program of the Foundation, and building a culture of inclusion for volunteers; 4 criteria), (7) Administrative and financial management (eg, establishing accounting rules, and making financial information accessible to stakeholders; 16 criteria), and (8) Governance (eg, holding an annual general meeting, and complying with the legal obligations of a non-profit and charitable organization; 15 criteria) (refer to appendix for more details on each domain).

Selection of Participants and Data Collection

A purposive sample composed of all 4 members of the CSPA team (a pediatrician, 2 social workers, and a director of operations) was used. Two semi-structured focus groups were conducted in person, voluntarily. All sessions were audio-recorded. The data collection took place in April 2019 by a team of 2 researchers. During the sessions, the data collection process was explained, and participants could ask questions. Each criterion of the scale was read to participants. Participants were asked to indicate, on a scale from 1 to 4 (4 being the highest), the degree of implementation of each criterion. They were also asked about the reason for this rating, challenges encountered, facilitators, and next steps. The final score attributed to each criterion was the result of the consensus among participants. Following the meeting, results were reported and validated by the 4 interviewed stakeholders through member checking.17

Data Processing and Analyses

For each domain of the scale, a mean score of all its criteria was calculated and proportions were calculated. Thus, a mean fidelity score of 4 out of 4 on 1 domain would be represented by a total level of fidelity of 100% concerning implementation. The qualitative content of each focus group was transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. Two researchers independently coded the interview data to ensure triangulation and collaboratively discussed participants’ responses. Qualitative description was selected closely reflect the data while providing a summary of the findings.18 The qualitative and quantitative data were merged to corroborate information regarding the implementation fidelity.19

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical approval was granted by 2 relevant research ethics committees: the Vitalité Health Network and the Université de Moncton (no. 1819-021). Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Results

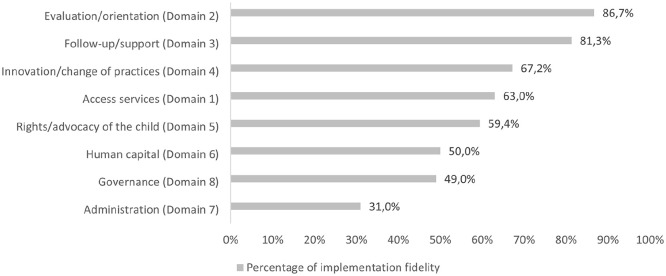

Overall, the level of implementation varied from 30.8% to 86.7%, with Domains 1 to 5 being over 50% and Domains 6 to 8, being equal to or below 50% (see Figure 1). Qualitative descriptions are provided for each domain (descending order from domains with the highest to the lowest implementation fidelity levels).

Figure 1.

Summary scores for the implementation fidelity of each domain related to the CSPA.

Evaluation/Orientation (Domain 2)

This domain had the highest level of fidelity implementation at 86.7% (15 criteria; Mean score/M = 3.47 out of 4; Standard deviation/SD = 0.55). The health-related evaluation/orientation approach employed by the pediatrician and social workers was reported as being collaborative and considering the multiple socio-political factors and contexts influencing the child and his family’s everyday life. This interactive process remains centered on the child and his family using a comfortable clinical platform and informal atmosphere. Although small, the CSPA center has a skilled and very proactive clinical team that focuses on an approach to care based on trust and transparency. Challenges, such as limited physical space, insufficient staff, work overload, and limited funding hinder the maintenance of certain clinical practices under the evaluation/orientation Domain, especially when dealing with complex clinical situations.

Follow-up/Support (Domain 3)

Follow-up/support had a high implementation fidelity level of 81.3% (12 criteria; M = 3.25 out of 4; SD = 0.58). Despite limited staff, the CSPA team offers support to basic needs and individual-level interventions, all of which can be offered to children and families within 3 months if needed. They apply interventions using a flexible, multidisciplinary, and systematic approach, centered on the best interests of the child while enabling open communication and interactions with the child and his family. The complex nature of certain situations can sometimes be a challenge to the development of a fully cohesive and integrated intervention plan for the child. Limited clinical resources in the community complicate the referral process and the establishment of partnerships.

Innovation/Change of Practices (Domain 4)

With regards to Innovation/change of practices, the level of implementation fidelity was at 67.2% (8 criteria; M = 2.69 out of 4; SD = 0.53). The CSPA team demonstrates high levels of critical thinking, self-reflection, and openness to feedback. The team can identify less successful practices and propose creative solutions to overcome them. However, human and financial restraints affect their ability to look at emerging evidence-based practices, implement innovative practices, consult with other organizations, and hold activities.

Access Services (Domain 1)

The level of implementation fidelity for this domain (63.0%; 22 criteria; M = 2.52 out of 4; SD = 0.87) was comparable to that of Innovation/change of practices. The CSPA center services are reachable, and they are mainly accessed by families with vulnerable school-aged children. The CSPA center includes multiple locations (school, community space), some with smaller spaces and others with access to greater space to welcome the family and clinical team during evaluations or interventions. The hospitality and interpersonal skills of the CSPA team, their flexibility (accommodating schedule, virtual or in-person services), as well as the proximity of services, are factors that enhance access to services. Clinical data are electronically compiled but not commonly shared between members of the clinical team through a computer database system.

Rights/Advocacy of the Child (Domain 5)

Regarding the Rights of the child and advocacy (4 criteria; M = 2.34 out of 4; SD = 0.87), the level of implementation fidelity was 59.4%. Members of the CSPA center reported a general sense of awareness of the principles of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Promotional and collaborative activities related to the Convention have also taken place in schools. Needs were identified by the team for expanding the consideration of the children’s rights in clinical care, including an increased level of communication and consultation with people in the legal field.

Human Capital, Administration, and Governance (Domains 6, 7, & 8)

The last 3 domains of the CSPA Fidelity Scale—Human capital, Administration, and Governance—were at levels of implementation fidelity of 50% or less. When looking at Human Capital (50.0%) (4 criteria; M = 2.00 out of 4; SD = 0.82) at the time of data collection, the CSPA team was composed of 4 staff members, a few volunteers, and some external collaborators (a receptionist and a legal consultant). The Governance domain was at 49.1% (14 criteria; M = 1.96 out of 4; SD = 1.15). The CSPA center is recognized both as a non-profit and a charitable organization. When data collection took place, the Annual General Meeting was scheduled, and a Board of Directors was to be elected. For now, the strategic vision remains to be developed, as well as ethical and deontological procedures. Finally, the Administration domain scored 30.8% (15 criteria; M = 1.23 out of 4; SD = 0.65). This low score was explained by few administrative and financial procedures implemented, partly because of limited financial resources at the time.

Discussion

This study aims to investigate the fidelity of implementation of the CSPA offered in 2 rural communities in NB, Canada. This assessment is crucial for identifying potential factors affecting the implementation of a complex healthcare set of interventions and their effectiveness.20 Overall, the results show high levels of the fidelity of implementation for domains namely orientation/evaluation and support/follow-up services domains. Yet, for innovation/changes of practice, access to services, and children’s rights/advocacy, the level of achievement was in the medium range while domains related to human capital, administrative/financial management, and governance had a lower level of fidelity of implementation.

Although funding for the CSPA is scarce, results have shown that the team in place is providing quality care, focusing on the child’s strengths and needs, and working with the family and the context in which they live. They use a family-centered approach to care while intervening clinically in a community-based scope of practice. As suggested in prior work,12 the high levels of fidelity of implementation for the evaluation and intervention services could be linked with the high level of competencies and commitment of the clinical team. Their skills and commitment to continuously learn and improve through competency-based clinical learning activities could also be associated with these 2 domains and other domains that achieved a moderate level of fidelity of implementation. Indeed, staff training and orientation have previously been described as one critical factor related to successful program implementation, as it provides the knowledge and skills needed to deliver a quality health-related program in any community context and promotes clinicians’ and employees’ support and commitment to their clients and their program.20,21

Some challenges impacted fidelity of implementation on multiple domains. Implementing health programs outside hospital settings can be challenging and these obstacles are not unique to the CSPA. Multiple factors within the program itself and within the larger context in which it is being implemented can contribute to creating a non-cohesive uptake when trying to establish an integrated healthcare platform in different community settings.20-23 As defined by Peters et al,24 context can include all levels of the social, cultural, economic, political, legal, and physical environment, including community settings with various stakeholders and their interactions, and demographics.

For instance, a lack of resources within the CSPA could have impacted the quality and access to care, the scope of services, the use of innovative practices, and the collaboration with public and community partners. In addition, a lack of specialized health and legal services for children with complex needs can further complicate access to care.25 This contrasts with the CSPA implemented in urban centers in the province of Quebec where specialized and legal services are integrated with the approach and are more accessible.8 Increasing specialized services for children and families in the province and resources within the CSPA could contribute to access to care, continuity of care within the child’s therapeutic care plan, and the diversification of care and services for children living with complex needs.

Results of the current study have also underlined lower levels of implementation fidelity for administrative, financial, and governance procedures. These more distal and organization-level factors of the program have also been shown to be implemented with less integrity in other community-based programs, partially due to limited financial or human resources or suboptimal relationships with community stakeholders.23 Similarly, Mihalic et al21 have suggested that having a program director, a coordinator, and champions leading the program together from its inception and throughout implementation can create a stronger basis for success and continuity. Therefore, for the CSPA, the addition of new people to the team would be valuable to improve infrastructures, stabilize financial resources, and enhance networking abilities with the communities (including visits to organizations and community involvement). This will contribute to further guidance and standardization of the CSPA program.

The study has many strengths that need to be acknowledged. First, a convergent mixed methods design was used allowing a comprehensive understanding of the results. Moreover, the ongoing collaborative relationship between researchers and participants favored a climate of trust and respect. Trust in the qualitative data is also enhanced by having 2 data analysts, peer debriefing, and member checking. Finally, these results have been presented to the CSPA team and will be part of an ongoing implementation monitoring over the next few years. This allows providing feedback to the team and offering recommendations to address areas of concern. This has been shown as useful to encourage adaptation and improve the fidelity of implementation in other community-based initiatives.20,21,23,24

As for all case studies, generalization of findings is a limit to this study as the data was collected at only 2 sites with a small number of participants. Also, the fidelity scale is considered preliminary, and standardization is warranted. As raised by Breitenstein et al,12 the fact that data are exclusively self-reported by members of the CSPA center also needs to be taken into consideration. Hence, future research is needed to test the currently developed grid with other CSPA centers and to combine it with other methods and sources of information such as patients’ perspectives.22 Future work is also warranted to continue monitoring the fidelity of implementation as the CSPA evolves and continues growing, to see where improvements or new challenges arise.

In conclusion, this work adds to the growing body of knowledge related to the fidelity assessment of the implementation of community-based health-related models of care.12,20-23 It demonstrates the feasibility of implementing community social pediatrics in small communities. At the same time, this study highlights different factors contributing to the fidelity of implementation of the CSPA, including resources within the program, and the larger context in which it is implemented. These can offer insights for the successful implementation of other similar community-based health interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinical team for taking the time to participate in this research. Without them, this work would not have been possible.

Appendix

Appendix.

Detailed Results on the Fidelity of Implementation of Each Criterion are Included in Each of the 8 Domains Related to the Assessment of the Community Social Paediatric Approach (CSPA).

| Item | Criteria | Results | Score /4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1—Access services | |||

| 1.1 | Maximize complementarity in the environment | The CSPA has a good knowledge of existing services in the community of Memramcook is less familiar with the mandate of organizations in the community of Kent. | 2.5 |

| 1.2 | Has a good knowledge of the community | Sociodemographic data specific to Memramcook and Kent are not always available since in the statistics they are combined with other communities. The CSPA also does not annually update the data they possess. | 2 |

| 1.3 | Organizes neighborhood visits | The CSPA involves new team members and interns in visits and activities within the community but does not organize visits to other communities. The pediatrician is very familiar with the Memramcook area but could visit the Kent region more. | 1.5 |

| 1.4 | Has a clinical database and a profile of the clientele | The data is compiled into computer databases, but the CSPA does not have a single database that is used by all team members. | 2 |

| 1.5 | Has a record management and retention system | The CSPA has a computerized management system, but the interface used limits the transferability of files between team members. | 3 |

| 1.6 | Reaches children in vulnerable situations in their community | The CSPA mainly serves young people of school age (primary level) in vulnerable situations, but it does not reach as many children under five and adolescents. | 2 |

| 1.7 | Reaches children in vulnerable situations in their community by the number of clinical days | Since the CSPA is in development, it fails to offer clinical days every week. | 1.5 |

| 1.8 | Possible to reach a member of the staff between appointments | Although it is generally possible to reach a member of the CSPA staff between appointments, the response will not always be received within 8-12 h as there is no staff on call at night and on weekends. There is questioning about the possible dependence of clients if CSPA staff are too readily available. | 2.5 |

| 1.9 | Reaches children in vulnerable situations in their community through active involvement in the community | The CSPA is clinically involved in the community, but this involvement is mostly concentrated in the Memramcook region, while community involvement in the Kent region is still little developed. | 2.5 |

| 1.10 | Promotes the Social Paediatric approach in the community | The CSPA sets up a variety of means to make the CSPA known to community partners, but the citizens are not necessarily familiar with the service and/or the referral process. | 3 |

| 1.11 | Is involved in the community and does screening | The CSPA is more involved in activities in the Memramcook region and occasionally screens during them but does so less systematically in other regions. | 2.5 |

| 1.12 | Sets up recurring activities within the community | Since the establishment of the center is recent, the objective is to involve the center in existing activities rather than creating new ones. | 1 |

| 1.13 | Sets up joint activities with partners within the community | The CSPA already collaborates in partner activities in the Memramcook community at least once a year but does not collaborate yet in other regions. | 3 |

| 1.14 | Offers physical proximity - building | The CSPA is accessible, close to schools, and a maximum of 30 min from all the communities where it is located but does not have a sign visible from the street allowing the location of the physical structure offering the services. | 3 |

| 1.15 | Offers physical proximity—openness | The CSPA is accessible more than 4 days a week, but on a flexible and virtual schedule, so there may be times during the week when there is no one at the CSPA. However, the team remains accessible by email and phone. | 4 |

| 1.16 | Offers physical proximity—layout | The Memramcook location is more spacious and therefore allows an arrangement adapted to families (reception area, assessment-orientation room, and office, without however offering a place for clinical services), while in other communities, the CSPA has only one space at school. | 2.5 |

| 1.17 | Offers physical proximity—clinic room | The Memramcook clinic room offers more of the sought-after items (such as a kitchen table, space for a physical examination, and toys), while for the other communities, the space offered is also convivial and warm, but smaller. | 1 |

| 1.18 | Offers an approach of relational proximity through its hospitality | A person is generally present at the reception during the opening hours of the CSPA. | 4 |

| 1.19 | Offers an approach of relational proximity through its soft skills. | The CSPA is transparent, respectful, authentic, and egalitarian in its approach, thanks to a careful selection of team members, as well as to the small size of the team. | 4 |

| 1.20 | Has a pre-assessment process for children in vulnerable situations | The pre-assessment process is not entirely clear and defined. | 2 |

| 1.21 | Sets up service corridors with community partners | The CSPA has developed service corridors with the school and with Family and Early Years, but they are not perfectly two-way. | 3 |

| 1.22 | Organizes regular meetings with community partners | Although the center occasionally organizes meetings with community partners, current resources are not sufficient to regularize these meetings. | 3 |

| Domain 2—Evaluation/orientation | |||

| 2.1 | The child and significant people for the child participate throughout the assessment/orientation meeting | The participation of the child and significant others is encouraged and their assent to decisions is required, but some people/organizations do not always respond to the invitation. | 4 |

| 2.2 | The doctor leads the assessment/orientation meeting by providing shared leadership | The doctor establishes a bond of trust and complicity with the child and the family. She acts as a consultant to the health team and uses a proactive, collaborative, and flexible approach to improving the health status of the child. | 4 |

| 2.3 | The social worker leads the assessment/orientation meeting by providing shared leadership | Thanks to their experience, social workers develop a bond of trust with those supported, gather information, identify resources, and collaborate in the care of clients. | 4 |

| 2.4 | Has collective know-how aimed at identifying the sources of toxic stress in children in their eco-bio developmental context | Thanks to the small size of the team, and the experience and dedication of its members, the CSPA team can do real collaborative work to take into account both the medical dimension and the socio-environmental in its approach. | 4 |

| 2.5 | Decodes the emotions and behaviors of the child, family, and participants | Team members decode emotions and behaviors. | 4 |

| 2.6 | Welcomes the child, family, and participants to create a climate favorable to the creation of a bond of trust | The reception of the child and the family is done by the worker at the reception and creative means are implemented to offer a friendly exchange from the start, but the location of the CSPA (small room, reception by secretary) in some of the regions may affect this. | 3 |

| 2.7 | Opens the assessment/orientation meeting by creating an informal and relaxed atmosphere | The child or family is always included, but sometimes the team may choose to meet without the child due to the nature of what the parent wants to discuss. | 3 |

| 2.8 | Has know-how that allows information to circulate | Team members will often be transparent and use open dialog, but in some cases, to maintain the bond of trust, they will take a moment to reflect before sharing the diagnosis or therapeutic treatment with the person accompanied by their parent. | 3 |

| 2.9 | Highlights the needs and strengths of the child, family, and community | While initially, team members often used a socio-environmental approach to identify the child’s strengths and motivations rather than focusing on their issues, there was some setback at this level, in part due to fatigue and overload of team members. | 3 |

| 2.10 | The doctor performs the physical examination of the child using the social paediatric approach | The doctor explores other elements in her discussions with the child during the physical examination. | 3.5 |

| 2.11 | The social worker completes the psychosocial portrait using the social pediatrics approach | Yes, and social workers use various means to obtain information on the functioning of the child and the family. | 4 |

| 2.12 | Uses two-way discussion | Parents are involved in the discussion and are informed, even if the child is met more often. We note that the evaluation of the physical living environment (the house) could be further developed in the meetings. | 4 |

| 2.13 | Uses a participatory and circular approach allowing the co-construction of hypotheses and possible solutions | When possible, the family is involved in identifying hypotheses about the sources of the child’s and family’s difficulties. | 3 |

| 2.14 | Defines, in consensus mode, a therapeutic and preventive action plan to act on the overall health of the child | The child is mostly informed of the steps related to his treatment plan because he participates in the discussion. | 2.5 |

| 2.15 | Ensures that the follow-up actions of the therapeutic and preventive action plan are implemented | Diagnosis and treatment are reassessed periodically, and efforts are made to engage community partners, but it does not always work. | 3 |

| Domain 3—Follow-up/support | |||

| 3.1 | Develops flexible and coherent care and follow-up/support services in complementarity with its community | The CSPA offers several services such as individual intervention services in the community and support for basic needs. The main challenge that limits the number of services offered is the lack of resources. | 3 |

| 3.2 | Has internal and external support and referral mechanisms to act on issues relating to the well-being of the child | When the needs warrant, people are met within less than 3 month, but alternative therapeutic resources are limited, making the referral process and the establishment of partnerships difficult. | 2.5 |

| 3.3 | Sets up follow-up/support services throughout the child’s development path | The actions of team members are concerted to ensure the consistency of psychosocial and medical interventions, but the child is not always involved in the development of the intervention plan due to a lack of resources. | 3 |

| 3.4 | Sets up conditions facilitating the creation of a collective intelligence specific to the Social Paediatric Approach | Competencies are shared within the CSPA team, but the role of the CSPA is not always clear to other actors, for example, school stakeholders. | 2.5 |

| 3.5 | Ensure the harmonious flow of information concerning the child while respecting the rules of confidentiality | The CSPA communicates and collaborates well with the resources/departments involved from a multidisciplinary perspective. | 4 |

| 3.6 | Manages risky situations or crises in the best interests of the child | Crisis management in the best interests of the child is sometimes complex because of the risk of breaking the relationship with partners; the search for consensus is preferred. | 3 |

| 3.7 | Builds and maintains a relationship of trust with the child and the family | Although meetings are not scheduled regularly, they are frequent. | 3 |

| 3.8 | Promotes and encourages shared experiences with children and families. | Discussions with children and families about their experiences and habits are encouraged. | 4 |

| 3.9 | Uses shared experiences to develop the therapeutic and preventive action plan and the intervention plans. | Team members use all the information at their disposal to reassess the therapeutic action plan. | 4 |

| 3.10 | Considers requests of the child and the family. | The CSPA often takes the perspective of the child and family into account when planning interventions, but it is difficult to include the voice of the child in some contexts. | 3 |

| 3.11 | Considers the different spheres of child development in making the clinical analysis. | The CSPA always assesses the situation from a systemic perspective. | 4 |

| 3.12 | Seeks to decode and relieve the effects of toxic stresses in children. | It is sometimes difficult to meet this criterion because of the difficulty that some parents may have in understanding the situation. | 3 |

| Domain 4—Innovation/Accompaniment | |||

| 4.1 | Wonders about practices and actions | The team periodically questions its practices, but feedback on practices is done more informally, once a year, and not always with all members. | 2.5 |

| 4.2 | Is open to constructive criticism | The team can deal with mishaps and is open to criticism. The team does not find it easy to choose a score specifying the diversity of situations encountered, the needs that must be met, and the human and financial resources available. | 3 |

| 4.3 | Understands the complexity of situations | The team finds that the assessment of the complexity of situations is not done “all the time” since there are tools (e.g., genogram, eco-map) that are not always used. Likewise, the Convention on the Rights of the Child is not “sufficiently” used. | 3 |

| 4.4 | Integrates evidence and research recommendations into its practices. | While some consult evidence-based information weekly, this is not the case for all team members. | 2.5 |

| 4.5 | Sets up a learning culture | The team finds that they do not know enough about the region, but they consider themselves to be participating in its co-construction. There are resources in the community (e.g., public services, family resources, extramural, social development, public health) with which there is communication/visit, but others have not yet been approached, especially in the Kent region. | 2 |

| 4.6 | Regularly and systematically assesses its practices. | The team often identifies practices that are not working. They mention the lack of time and the difficulty of maintaining human resources by a lack of financial resources. | 2 |

| 4.7 | Regularly implements new and original solutions | Although the team says they do not lack solutions, the use of these solutions is not done regularly, especially in Kent County. | 3 |

| 4.8 | Acts as an ambassador for social pediatrics. | The team believes they engage in advocacy for children on an ad hoc basis and they offer/participate in conferences every month, except for the last 4-5 month. | 3.5 |

| Domain 5—Rights of the child and advocacy | |||

| 5.1 | Identifies the needs related to the violated rights of children within their community | The team says the Convention on the Rights of the Child “is not being applied” consistently. The team knows the seven main principles, without going in-depth, and they understand the full text of this Convention. | 3 |

| 5.2 | Identifies potential legal partners to promote access to justice | The team has worked with a lawyer (even two in the past) on some cases, but not on children’s cases. | 2 |

| 5.3 | Favors non-contentious approaches. | The team specifies that they know a few approaches mainly related to their area of specialization (e.g., medicine, social work), but considers that they know very few strategies in the legal field. | 2 |

| 5.4 | Is proactive in promoting and defending children’s rights | The team posts at least one child rights document and organizes at least one activity in a school to promote these rights. The team claims to have worked with the school district on children’s rights. | 2.5 |

| Domain 6—Human capital | |||

| 6.1 | Has human resources in line with the identified needs of children in vulnerable situations | The team gives a more nuanced answer, specifying that there are two people employed by the center. The center also has the support of a receptionist (not paid by the center); and collaborates with a legal specialist. | 2 |

| 6.2 | Sets up a process for the selection, hiring, and retention of staff | The team considers that there is no specific selection, hiring, or retention process at the center. | 1 |

| 6.3 | Follows the training and support program of the Dr. Julien Foundation | The team follows basic training. | 3 |

| 6.4 | Builds a culture of inclusion for volunteers | The team considers that it can count on the support of certain volunteers for the organization of various activities (e.g., activities with children, social coffee), but it does not have formal mechanisms for recognizing and including volunteers. | 2 |

| Domain 7—Administrative and financial management | |||

| 7.1 | Accounting rules | In the future, it will be necessary to monitor finances locally. | 1 |

| 7.2 | Financial states | The team considers that, given the lack of financial resources and the modest sums available, this criterion is less applicable when evaluating fidelity. Although the center is incorporated and the team must provide an accounting report for tax purposes, the amounts shown are 0. | 1 |

| 7.3 | Bookkeeping | The team considers that they are not keeping an accounting book at the time of the evaluation. | 1 |

| 7.4 | Financial information | The team considers that financial information is available to center officials and sometimes to external agencies (eg, Ministry of Education and Early Childhood Development). | 1.5 |

| 7.5 | Financial report | The center must produce an annual financial report presenting the major activities and achievements as well as the financial statements for the year. | 1 |

| 7.6 | Funding sources | The team does not have fundraising strategies. It claims to have two sources of external funding, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Department of Health. She sets up some ad hoc fundraising means. | 2 |

| 7.7 | Allocation of funds | Over 80% of funds are administrative costs (salaries). | 1 |

| 7.8 | Cash-flow | The team says they have no cash. | 0.5 |

| 7.9 | Financial partners | There is minimal connection with donors and issuance of tax receipts at the time of the evaluation (limited to one). | 1 |

| 7.10 | Fundraising | The team says it enforces regulations regarding the issuance of tax receipts. | 2 |

| 7.11 | Administrative procedures | The team says it does not have any administrative procedures in place. | 1 |

| 7.12 | Financial control measures | The team considers financial controls to be important, but these measures are not in place yet. | 1 |

| 7.13 | Ethics | There is no board of directors in place for the center. | 0.5 |

| 7.14 | Legal obligations | Most financial documents are kept per current government standards. | 3 |

| 7.15 | Insurance | The CSPA has property insurance, and the homeowner has third-party insurance. | 1 |

| 7.16 | Security and confidentiality | Each professional applies the security and confidentiality criteria related to his profession, but no overall policy for the center has been established. The team, therefore, considers that this criterion does not currently apply. | - |

| Domain 8—Governance | |||

| 8.1 | Legal and fiscal status | Regarding legal and fiscal status, the implementation is complete, since the CSPA is recognized both as a non-profit organization and as a charitable organization. | 4 |

| 8.2 | Mission | The mission is disseminated to the various actors, but mostly verbally. | 3.5 |

| 8.3 | General regulations | The general regulations cover all the necessary elements, but they have not yet been adopted since the board of directors has not yet been appointed. | 4 |

| 8.4 | Annual General Meeting (AGM) of Members | This criterion does not currently apply. The first annual general meeting has not yet taken place at the time of the evaluation, but it is planned. | - |

| 8.5 | Compliance with the legal obligations of a non-profit and charitable organizations | Since the first year of operation of the CSPA has not ended, legal obligations have not yet been met. | 2 |

| 8.6 | Election or appointment of directors: directors are diversified | Although potential candidates for the board have been identified, it has not yet been established. | 1 |

| 8.7 | Election or appointment of directors: directors are integrated | It is expected that invitations to participate in the board of directors will be sent and the representativeness of interest groups on the board is provided for in the general regulations. | 1.5 |

| 8.8 | Roles and responsibilities of directors | The responsibilities of the directors have been defined in writing but are not adopted by the board of directors as it does not yet exist. | 1.5 |

| 8.9 | Board of Directors meetings | Only the start-up committee participated in the meetings, but a first meeting of the board of directors, i.e., the annual general meeting, is planned. | 1.5 |

| 8.10 | Responsibilities of the CSPA Manager | Since the board of directors has not yet been elected, there is no review process for the manager of the CSPA. | 1 |

| 8.11 | Complaint’s handling | The CSPA does not have a complaints process | 1 |

| 8.12 | Code of ethics | The CSPA does not have its code of ethics | 1 |

| 8.13 | Conflicts of interest | The CSPA does not have a mechanism for preventing, controlling, and dealing with conflicts of interest | 1 |

| 8.14 | Confidentiality | Team members must respect confidentiality related to their professional code of ethics, but the CSPA does not have a defined confidentiality procedure. | 3 |

| 8.15 | Objectives and strategic vision | Objectives have started to be defined, but the board has not been elected and the strategic vision has not been developed. | 1.5 |

Criteria 8.4 and 7.16 were deemed non-applicable at this time and were therefore omitted. The scale was based on the Dr. Julien Foundation standard accreditation document (Bureau de normalisation du Québec, 2017).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Doucet D: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Dubé A: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Corriveau H: Select item; contributed to analysis and interpretation; Select item; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Blaney S: Contributed to conception and design, contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; Select item; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Iancu P: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to analysis and interpretation; Select item; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Morin S: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to analysis and interpretation; Select item; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

Plourde V: Select item; contributed to analysis and interpretation; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Government of New Brunswick.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Comité d’éthique de la recherche, Réseau de santé Vitalité; Comité d’éthique de la recherche avec les être humains, Université de Moncton, no. 1819-021) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ORCID iD: Danielle Doucet  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7714-123X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7714-123X

References

- 1. Raphael D. Social Determinants of Children’s Health in Canada: Analysis and Implications. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies. 2014;5:220-239. doi: 10.18357/ijcyfs.raphaeld.522014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burczycka M, Conroy S. Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile, 2015. 2017. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14698-eng.htm

- 3. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Children and Youth. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/what-we-do/children-and-youth

- 4. Köhler L; European Society for Social Paediatrics. ESSOP-25 years: personal reflections from one who started the European Society for Social Paediatrics. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29(5):321-328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2003.00350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spencer N, Colomer C, Alperstein G, et al. Social paediatrics. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(2):106-108. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.017681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Julien G, Lieber K. A Different Kind of Care: The Social Pediatric Approach. McGill-Queen’s University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dr. Julien Foundation. Dr. Gilles Julien: The Man at the Heart of the Foundation. Accessed May 11, 2022. http://fondationdrjulien.org/en/foundation/dr-gilles-julien/

- 8. Clément MÈ, Moreau J, Gendron S, et al. Regard Mixte Sur Certaines Particularités et Retombées de l’approche de La Pédiatrie Sociale Telle Qu’implantée Au Québec et Sur Son Intégration Dans Le Système Actuel Des Services Sociaux et de Santé. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://institutpediatriesociale.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/RapportScIntegral_2012-DJ-164587_Clement_M-E-2.pdf

- 9. Clément MÈ, Lavergne C, Turcotte G, Gendron S, Léveillé S, Moreau J. Collaboration entre les centres de pédiatrie sociale en communauté et les réseaux des services sociaux public et communautaire pour venir en aide aux familles : Quelle place et quels enjeux pour les acteurs? Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2015;106(Suppl 7):eS66-eS73. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.106.4822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clément MÈ, Bérubé A, Moreau J. Le modèle de la pédiatrie sociale en communauté et ses retombées sur le bien-être des familles : une étude pilote. La revue internationale de l’éducation familiale. 2017;39(1):81-106. doi: 10.3917/rief.039.0081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’Donnell CL. Defining, conceptualizing, and measuring fidelity of implementation and its relationship to outcomes in K–12 Curriculum Intervention Research. Rev Educ Res. 2008;78(1):33-84. doi: 10.3102/0034654307313793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(2):164-173. doi: 10.1002/nur.20373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods, 5th ed. SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson B, Christensen L. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches, 6th ed. SAGE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bureau de normalisation du Québec. Référentiel de certification des centres de pédiatrie sociale en communauté (CPSC). Published online 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, Bybee D. Fidelity criteria: development, measurement, and validation. Am J Eval. 2003;24(3):315-340. doi: 10.1177/109821400302400303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Creswell JW, Poth J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed. SAGE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A Systematic Review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23-42. doi: 10.1002/nur.21768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134-2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bird ML, Mortenson WB, Eng JJ. Evaluation and facilitation of intervention fidelity in community exercise programs through an adaptation of the TIDier framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4919-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mihalic SF, Fagan AA, Argamaso S. Implementing the LifeSkills Training drug prevention program: Factors related to implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1-9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richards Z, Kostadinov I, Jones M, Richard L, Cargo M. Assessing implementation fidelity and adaptation in a community-based childhood obesity prevention intervention. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(6):918-932. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Republished research: Implementation research: What it is and how to do it. BMJ. 2014;48(8):731-736. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richard B, Smallwood S. Staying Connected : A Report of the Task Force on a Centre of Excellence for Children and Youth with Complex Needs. Office of the Ombudsman and Child and Youth Advocate. 2011. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.ombudnb.ca/site/images/PDFs/staying_connected-e.pdf [Google Scholar]