Abstract

Understanding the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers in wastewater should guide wastewater-based epidemiology users in selecting best RNA biomarkers for reliable detection of the virus during current and future waves of the pandemic. In the present study, the persistence of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 were assessed during one month for six different RNA biomarkers and for the pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) at three different temperatures (4, 12 and 20 °C) in one wastewater sample. All SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers were consistently detected during 6 days at 4° and differences in signal persistence among RNA biomarkers were mostly observed at 20 °C with N biomarkers being globally more persistent than RdRP, E and ORF1ab ones. SARS-CoV-2 signal persistence further decreased in a temperature dependent manner. At 12 and 20 °C, RNA biomarker losses of 1-log10 occurred on average after 6 and 4 days, and led to a complete signal loss after 13 and 6 days, respectively. Besides the effect of temperature, SARS-CoV-2 RNA signals were more persistent in the particulate phase compared to the aqueous one. Finally, PMMoV RNA signal was highly persistent in both phases and significantly differed from that of SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers. We further provide a detailed overview of the latest literature on SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV decay rates in sewage matrices.

Keywords: Wastewater-based epidemiology, Decay rate, SARS-CoV-2, Biomarkers partitioning, PMMoV

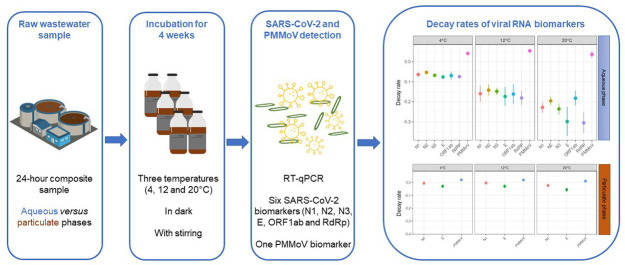

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is currently causing an unprecedented public health crisis with profound health, social and economic impacts. Scientists and governments have had to develop new strategies to limit the impact of this evolving pandemic on their health systems and societies. Among these strategies, wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) has proven to be a relevant and almost indispensable tool for monitoring the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 circulation at the community level. Although the main routes of SARS-CoV-2 are airborne transmission and person-to-person contact (Samet et al., 2021), SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the faeces of infected patients (Miura et al., 2021) and in wastewater from many countries around the world. On this basis, WBE has been proposed as a tool for monitoring virus circulation at population level and the European Commission strongly encouraged the Member States to put in place a national wastewater surveillance system targeted at data collection of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants in wastewaters (UE 2021/472). Several RNA biomarkers have been proposed for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, but no specific recommendation has been done toward the preferred used of one of these biomarkers. Most of the ongoing research has primally focused on optimising virus recovery methods (Ahmed et al., 2020c; Bertrand et al., 2021; Calderón-Franco et al., 2022; Forés et al., 2021), comparison of RT-qPCR methods (Ahmed et al., 2022), monitoring of the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater by RT-qPCR (ex. (Ahmed et al., 2020a, Hasan et al., 2021, Medema et al., 2020b, Wu et al., 2020a, Wurtzer et al., 2020) as well as improving the detection limits and reducing false negative and positive results (Ahmed et al., 2020c; Ahmed et al., 2020d). However, to be as relevant as possible, WBE still needs to be improved by answering many remaining outstanding scientific questions, such as the variability in magnitude and duration of faecal shedding, the kinetics of the viral load and excretion over the entire course of a symptomatic and asymptomatic infection, as well as the half-life or persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers monitored in wastewater. All this information is crucial, especially for modelling the absolute level of infection and infer actual incident cases of COVID-19 in a population from SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentrations in wastewater (Hong et al., 2021; Proverbio et al., 2022).

Like all other faecally excreted viruses, SARS-CoV-2 can be subjected to numerous inactivation and degradation factors during transport in sewage, leading to possible viral particle degradation and RNA fragmentation (Kantor et al., 2021). As a result, SARS-CoV-2 can be found under the form of intact viruses, capsid compromised viruses, and free nucleic acids (Wurtzer et al., 2021). During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, little was known about the stability of SARS-CoV-2 and its RNA in untreated wastewater and sewage systems after excretion by an infected individual (Hart and Halden, 2020; Wu et al., 2020b). Most of the available knowledge came from previous studies on other human coronaviruses (CoV) (Amoah et al., 2020; Gundy et al., 2008) or model viruses of CoV (Casanova et al., 2009). Since then, studies have reported the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in untreated wastewater or sludges seeded with infectious or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 particles (Table 1 ). Although these studies provide important information on the decay dynamics of SARS-CoV-2, they are not performed under environmentally relevant conditions since used viral concentrations largely exceed those found in raw sewage. Therefore, while the data revealed a specific and significant decay pattern of viruses in wastewater, there may be a difference in the persistence properties of lower titres (~103 copies/L) of SARS-CoV-2 typically found in raw wastewater (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Bivins et al., 2020; Sala-Comorera et al., 2021). Recent studies have examined the degradation of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers and infectious particles in raw wastewater (see Table 1). However, a limited number of RNA fragments of interest (up to three) were investigated and compared in these studies, with a focus on E and N genes. Other RNA biomarkers (RdRp, ORF1ab, S gene) have been proposed and used for routine monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater-based epidemiology (Bertrand et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; La Rosa et al., 2020; Sakarovitch et al., 2022), but no information is currently available on the persistence of those SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers. This information is important as several studies have reported that different regions of a same viral genome (RNA or DNA viruses) can exhibit statistically different degradation kinetics after inactivation treatment using (RT)-qPCR tools (Li et al., 2004; Page et al., 2010; Qiao et al., 2022). Possible explanations are the enriched presence of certain nucleotide bases (Rockey et al., 2020) and/or the presence of secondary structures on the target region (Relova et al., 2018). In any case, this information is essential to select the most relevant biomarker for large-scale monitoring purposes.

Table 1.

Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 (RNA biomarkers and infectious particles) in wastewater influent (WWI) and primary treated solids retrieved from recent literature. ⁎ RNA signal loss is expressed either in T90 (days), log reduction values (LRV) or percentage of reduction (PR).

| SARS-CoV-2 target | Experimental conditions | Temperature | RNA signal loss⁎ | Decay rate constant (k) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) Wastewater | |||||

| RNA (N1 assay) | WWI spiked with gamma-irradiated SARS-CoV-2 (~107 gc/L) No clarification No concentration No stirring/aeration 15-mL microcosms Incubation 33 days in dark |

4 °C 15 °C 25 °C 37 °C |

T90: 27.8 ± 4.45 days T90: 20.4 ± 2.13 days T90: 12.6 ± 0.59 days T90: 8.04 ± 0.23 days |

0.084 ± 0.013 d−1 0.114 ± 0.012 d−1 0.183 ± 0.008 d−1 0.286 ± 0.008 d−1 |

(Ahmed et al., 2020b) |

| RNA (E assay) | WWI spiked with infectious SARS-CoV-2 (~105 and ~103 TCID50/mL) No clarification No concentration No stirring/aeration 15-mL microcosms Incubation 7 days in dark |

20 °C | T90: 3.3 days (high titer) T90: 26 days (low titer) |

0.67 d−1 (high titer) 0.09 d−1 (low titer) |

(Bivins et al., 2020) |

| RNA (N2 assay) | WWI with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 (~104 gc/L) Clarification step (4654 × g, 30 min.) No concentration Incubation 16 days |

5 °C | Data from this study indicate that SARS-CoV-2 RNA is stable in wastewater when stored at 5 °C | nd | (Medema et al., 2020a) |

| RNA (N1, N2 and E assays) | WWI endogenous SARS-CoV-2 Clarification step (4625 × g, 30 min.) Concentration by ultrafiltration (Centricon Plus-70) No stirring/aeration 50-mL microcosms Incubation 10 days (4 °C) |

4 °C | N2-gene fragment showed high in-sample stability in WWI for 10 days of storage at 4 °C. The E gene fragment proved to be less stable compared to the N2-gene fragment |

nd | (Boogaerts et al., 2021) |

| RNA (N2 and E assays) | WWI spiked with SARS-CoV-2 isolated from swab (~108 gc/mL) Clarification step (4654 × g, 30 min.) Concentration by ultrafiltration (Centricon Plus-70) No stirring/aeration 50-mL microcosms Incubation 28 days |

4 °C | T90: 36 days (N2) T90: 52 days (E) |

0.06 ± 0.0 d−1 (N2) 0.04 ± 0.2 d−1 (E) |

(Hokajärvi et al., 2021) |

| RNA (N1 and N2 assays) | WWI with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 (1.3–9.5 105 gc/L) Clarification step (4000 × g, 20 min.) Acidification Filtration (negatively charged mixed cellulose ester 0.45 μM membrane) No stirring/aeration 250-mL microcosms Incubation up to 22 h (10 °C and 35 °C) and up to 7 days (4 °C) |

4 °C 10 °C 35 °C |

PR: 86.5 % (7 days) PR: 67 % (22h) Not detectable after 6 h |

0.04 to 0.09 h−1 0.09 h−1 0.18 h−1 |

(Weidhaas et al., 2021) |

| RNA (E, ORF1ab, RdRP, and NSP3 assays) | WWI endogeneousSARS-CoV-2 (~105 gc/L) Clarification step (5000 × g, 30 min.) Concentration by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation 600-mL microcosms Incubation at room temperature (RT) Aerobic or anaerobic conditions |

RT | LRV: 1 log10 (24 h, aerobic), undetectable after 4 days LRV: 0.3 log10 (24 h, anaerobic), subsequently concentration stable |

nd | (Ho et al., 2022) |

| RNA (N1 and E assays) | WWI with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 (5.103 gc/L) No clarification Concentration by ultrafiltration No stirring/aeration 200-mL microcosms Incubation 7 days in dark Freezing at −80 °C before RNA quantification |

4 °C 26 °C |

T90: 17.17 days T90: 7.68 days |

0.134 d−1 (0.046–0.314) 0.274 d−1 (0.234–0.314) |

(Yang et al., 2022) |

| RNA (N1 assay) |

WWI with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 Clarification step (4500 × g, 30 min.) Concentration by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation Incubation up to 9 days at 4 °C |

4 °C | No significant effect on the number of detectable SARS-CoV-2 fragments | nd | (Markt et al., 2021) |

| RNA (N1 assay) |

WWI with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 No clarification step Concentration by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation Incubation 7 and 14 days at 4 °C |

4 °C | PR: 1.11 % (7 days) PR: 11.23 % (14 days) |

(Islam et al., 2022) | |

| Infectious assay | WWI spiked with infectious SARS-CoV-2 (~105 and ~103 TCID50/mL) No clarification No concentration No stirring/aeration 15-mL microcosms Incubation 7 days in dark |

20 °C | T90: 1.6 days (high titer) T90: 2.1 days (low titer) |

1.4 d−1 (high titer) 1.1 d−1 (low titer) |

(Bivins et al., 2020) |

| Infectious assay | WWI autoclaved spiked with infectious SARS-CoV-2 | 4 °C 24 °C |

T90: 12.1 days T90: 2.9 days |

0.19 d−1 0.83 d−1 |

(de Oliveira et al., 2021) |

| b) Primary sludge | |||||

| RNA (N1 and N2 assays) | Primary sludge with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 (3–4.104 gc/g dry weight) No stirring Purged with ambient air or nitrogen gas for 10 min. 600-mL microcosms Incubation 7 days |

4 °C 22 °C 37 °C |

T90: 65 to 214 days T90: 26 to 107 days T90: 23 to 49 days |

0.01 to 0.04 d−1 0.02 to 0.08 d−1 0.05 to 0.98 d−1 |

(Roldan-Hernandez et al., 2022) |

| RNA (N, S and ORF1a assays) |

Settled solids with endogenous SARS-CoV-2 Dewatering step: centrifugation 24,000 ×g, 30 min Short-term storage: 7–8 days at 4 °C Long-term storage: 35–122 days at 4 °C |

4 °C | Short-term: PR: 0 % (3/4 samples) PR: 60–80 % (1/4 samples) Long-term: PR: 29–63 % (average 40 %) |

nd | (Simpson et al., 2021) |

With the rise of WBE during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) has been used as an endogenous viral process control and faecal indicator (Wu et al., 2020a), as previously described in studies on enteric viruses (Ahmed et al., 2021; Kitajima et al., 2018). In addition, several studies on the monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater have used PMMoV to normalise SARS-CoV-2 concentrations (D'Aoust et al., 2021). Considering the inherent size and structure differences between PMMoV and SARS-CoV-2, a better understanding of the relative persistence of both viruses in wastewater is needed. Whereas similar decay rates between endogenous SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV were observed in primary settled solids (Roldan-Hernandez et al., 2022), their relative persistence in wastewater is currently not known.

The objective of the present study was to assess the persistence of six RNA biomarkers (N1, N2, N3, E, RdRP and ORF1ab) of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 as well as PMMoV, at three different temperatures (4, 12 and 20 °C) typically found over the year in cold and temperate sewersheds. To investigate a possible effect of virus partitioning on signal persistence, we further compared RNA biomarker decay in the aqueous and particulate phases of wastewater for SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sampling and microcosm setup

For the study of SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV RNA signal persistence in wastewater, a 24-h composite raw sewage sample (20L) was collected on Jan 26, 2021, using an automated sampler at the inlet of the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) of Luxembourg City, Luxembourg. The WWTP collects domestic sewage from approximately 140,000 people and receives also industrial and hospital wastewaters. At the time of sampling, 150 cases of COVID-19 were reported in the population of the sewershed the week preceding sample collection. The SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in the raw sewage sample used in this study averaged 1.0 ± 0.6 × 104 genome copies per L (gc.L−1) and 3.8 ± 0.1 × 102 gc.L−1, in the aqueous and particulate phases, respectively. Upon collection, the composite sample was immediately brought back to the laboratory and used to prepare the microcosms.

The 27-day persistence experiment was performed in microcosms consisting of autoclaved 250-mL glass bottles with an aerated cap and a magnetic stirrer. Each microcosm contained 200 mL of raw sewage and was placed on an OxiTop® table for continuous mixing during the duration of the experiment. Bottle microcosms were incubated at 4, 12 and 20 °C in absence of light. For 20 °C, a complete Oxitop® system (table and incubator) maintained a constant temperature, while for 4 and 12 °C, Oxitop® tables were only placed in thermostatic incubators (Memmert).

At the day of sampling, three bottles were analysed for the determination of the initial concentration of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers (T0). For each subsequent time point, a total of three bottles per temperature condition were sacrificed to quantify SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers. The latter were analysed after 1, 3, 6, 9, 13, 20 and 27 days of incubation (T1, T3, T6, T9, T13, T20 and T27, respectively).

2.2. Sample processing

At the time of analysis, samples were all spiked with a fresh suspension of Phi 6 (DSMZ, DSM 21518) used as a process control at a final concentration of 500 PFU.mL−1. This enveloped bacteriophage (Cystoviridae) has been suggested as a surrogate for studying persistence of enveloped viruses including human coronaviruses (Silverman and Boehm, 2020). Upon spiking, samples were gently mixed, and shortly after, they were centrifuged at 2400 ×g for 20 min to pellet large particles. The particulate phases obtained from the pre-centrifugation step were frozen at −80 °C and kept for further analyses. Supernatants were processed on Amicon-15 10 kDa ultracentrifuge units (Millipore, UFC901024) at 3200 ×g for 25 min. The concentrate (1.4 to 6.7 mL) was directly used for RNA extraction or stored at −80 °C until further use.

2.3. Viral RNA extraction

Viral RNA was extracted from each replicate microcosm concentrate (280 μL-aliquots of the total concentrate) using the QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit (Qiagen, 52906) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Frozen particulate phases were thawed at 4 °C and viral RNA was extracted from 140-μL aliquots of each. RNA from aqueous samples and particulate phases was eluted in 60 μL AVE buffer and directly processed by RT-qPCR or stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

2.4. RT-qPCR analyses

Based on available literature for the quantification of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewaters, it was decided to target six different RNA biomarkers located in the N (N1, N2, N3), E, RdRP and ORF1ab genes. Published RT-qPCR assay conditions (Table 2 ) were set up in this study and optimized for primer/probe concentrations using the EDX SARS-CoV-2 synthetic RNA standard (Biorad, COV019). This standard was manufactured with synthetic RNA transcripts containing 5 gene targets (E, N, S, ORF1a, and RdRP genes) of SARS-CoV-2 at a concentration of 200,000 copies.mL−1 each. Analytical limits of detection (LOD) were determined for each assay based on a minimum 95 % positivity rate (Bustin et al., 2009). For the RdRP gene, the initial assay developed by (Corman et al., 2020) was optimized using the reverse primer modified by (La Rosa et al., 2021). All RT-qPCR were performed in 20 μL reaction mixtures (15 μL RT-qPCR mix and 5 μL RNA extract) using the respective primer/probe sets and TaqPath™ One-Step RT-qPCR Master mix, CG (Thermofisher Scientific, A15299). For each RNA biomarker, standard curves were carried out using the EDX SARS-CoV-2 synthetic RNA that was serially log-diluted in DNase-RNase-free water. To reduce the uncertainty associated with the estimation of SARS-CoV-2 concentrations, a pooled standard calibration curve approach (Sivaganesan et al., 2010) was adopted. Following this approach, RNA standard measurements from all runs were pooled (Fig. S1) while simultaneously generating a calibration curve for each single RT-qPCR run.

Table 2.

Primers, probes and RT-qPCR cycling information for the assays used in this study. BHQ, black hole quencher; FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescéine; MGBEQ, minor-groove binding Eclipse® quencher; NFQ, non-fluorescent quencher; ORF, open reading frame; PMMoV, pepper mild mottle virus; RdRP, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

| Assay | Target gene | Primer/Probe name | Concentration (nM) | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | N1 | 2019-nCoV_N1-F | 500 | GACCCCAAAATCAGCGAAAT | (CDC, 2020) |

| 2019-nCoV_N1-R | 500 | TCTGGTTACTGCCAGTTGAATCTG | |||

| 2019-nCoV_N1-P | 125 | FAM-ACCCCGCATTACGTTTGGTGGACC-BHQ | |||

| N2 | 2019-nCoV_N2-F | 500 | TTACAAACATTGGCCGCAAA | (CDC, 2020) | |

| 2019-nCoV_N2-R | 500 | GCGCGACATTCCGAAGAA | |||

| 2019-nCoV_N2-P | 125 | FAM-ACAATTTGCCCCCAGCGCTTCAG-BHQ | |||

| N3 | 2019-nCoV_N3-F | 500 | GGGAGCCTTGAATACACCAAAA | (CDC, 2020) | |

| 2019-nCoV_N3-R | 500 | TGTAGCACGATTGCAGCATTG | |||

| 2019-nCoV_N3-P | 125 | FAM-AYCACATTGGCACCCGCAATCCTG-BHQ | |||

| E | E_Sarbeco_F | 500 | ACAGGTACGTTAATAGTTAATAGCGT | (Corman et al., 2020) | |

| E_Sarbeco_R | 500 | ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA | |||

| E_Sarbeco_P1 | 125 | FAM-ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG-BHQ | |||

| RdRp | RdRP_SARSr-F2 | 600 | GTGARATGGTCATGTGTGGCGG | (Corman et al., 2020) | |

| RdRP_SARSr-R1mod | 800 | CARATGTTAAAAACACTATTAGCATA | (La Rosa et al., 2021) | ||

| RdRP_SARSr-P2 | 250 | FAM-CAGGTGGAACCTCATCAGGAGATGC-BHQ | |||

| ORF1ab | 2297-CoV-2-F | 500 | ACATGGCTTTGAGTTGACATCT | (La Rosa et al., 2021) | |

| 2298-CoV-2-R | 900 | AGCAGTGGAAAAGCATGTGG | |||

| 2299-CoV-2-P | 250 | FAM-CATAGACAACAGGTGCGCTC-MGBEQ | |||

| PMMoV | Viral coat protein | PMMV-FP | 400 | GAGTGGTTTGACCTTAACGTTTGA | (Haramoto et al., 2020) |

| PMMV-RP | 400 | TTGTCGGTTGCAATGCAAGT | |||

| PMMV-P | 200 | FAM-CCTACCGAAGCAAATG-NFQ-MGB | |||

| Phi 6 | S segment | phi6T-F | 1000 | TGGCGGCGGTCAAGAGC | (Gendron et al., 2010) |

| phi6T-R | 1000 | GGATGATTCTCCAGAAGCTGCTG | |||

| phi6T-P | 300 | FAM-CGGTCGTCGCAGGTCTGACACTCGC-BHQ |

2.5. Quality control and quality assurance

To monitor the recovery performance of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarker detection workflow, the bacteriophage Phi 6 was spiked into each sample (500 PFU.mL−1 final concentration) prior to sample concentration. PCR inhibition was monitored in the aqueous and particulate phases using a synthetic internal positive control (IPC) (VetMAX™ Xeno™ Internal Positive Control, A29762 and VetMAX™ Xeno™ Internal Positive Control - VIC™ Assay, A29767; ThermoFisher Scientific), which was added to the RT-qPCR mix following the instructions of the manufacturer. To determine PCR inhibition, IPC DNA was added to positive control wells (SARS-CoV-2 RNA, EVAg-GLOBAL material) and the mean Cq value ± standard deviation (n = 18) was used as reference point to determine if inhibition occurred in wastewater samples. The latter were considered to have PCR inhibition if the Cq values of the IPC exceeded the reference point by >2 Cq values (Ahmed et al., 2020d). Each RT-qPCR reaction was run in triplicates, both for standards and microcosm samples. To minimize the risk of RT-qPCR contamination, RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analysis were performed in separate laboratories. Extraction blanks were added to each RNA extraction run and no template controls were added to each RT-qPCR plate.

2.6. Decay of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers and T90 prediction

Because of the uncertainty associated with the quantification of RNA concentrations for Cq values close to and below the LOD, SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV RNA Cq values at each time point (0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 13, 20 and 27) were analysed according to Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where C t and C o are the RNA biomarker concentrations at time t and time 0, respectively; Cqt and Cq0 are the Cq values at time t and time 0, respectively, and a is the slope of the RT-qPCR standard curve for each RNA biomarker assay. Considering the low starting concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 in our microcosms, non-detects occurred during the experiment and their frequency increased over time. To account for these results, non-detects (absence of amplification) were attributed a Cq value of 40 and the maximum decay that could be observed based on the Cq values measured at T0 were calculated according to Eq. (1). Regression analysis was used to model the decay of each SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarker as a function of time. To this end, simple linear regression models were fitted to experimental data and used to predict T90 reduction times (i.e., the predicted number of days to achieve a 1-log10 reduction), as previously described (Ogorzaly et al., 2010). The decay of each RNA biomarker (SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV) under the different experimental conditions (i.e., conservation temperatures of 4 °C, 12 °C or 20 °C, and aqueous phase or particulate phase) was modelled according to Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where the dependent variable is the log10 of the ratio of C t to C o (i.e., the RNA biomarker concentrations at time t and time 0, respectively), k represents the slope of the regression line i.e., the first-order decay rate constant (expressed in log10 units per day), and t is the time (day) of sampling. The intercept of the regression line is 0 as it represents the decay rate at time 0. The slopes calculated for the different experimental conditions and RNA biomarkers represent the corresponding Cq increase (i.e., RNA signal decrease) per day. The time needed to achieve a 1-log10 reduction in RNA biomarker signal (T90) was calculated using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where k represents the first-order decay rate constant estimated in Eq. (2) for the different experimental conditions and RNA biomarkers.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Differences in decay rates between biomarkers in the aqueous phase were assessed by comparing the 95 % confidence intervals (Green et al., 2011; Tiwari et al., 2019). The 1 - a confidence limits for k were calculated using Eq. (4):

| (4) |

where the statistical significance was set at a = 0.05, n is the sample size, and SE is the standard error. Decay rates were considered different when the 95 % confidence intervals of 2 biomarkers did not overlap.

The association between the SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV biomarker signal loss over time and the conservation temperature (4 °C, 12 °C or 20 °C) or the sample phase (aqueous or particulate) was taken into consideration. Multivariate linear regression models were built, and model assumptions checked. Non-detect samples were excluded from these analyses. Data manipulation and statistical analyses were done in R (R Core Team, 2022) using the Tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019), readxl (https://readxl.tidyverse.org/), gridExtra (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gridExtra/index.html), car (Fox and Weisberg, 2019) and multcomp (Hothorn et al., 2008) packages.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. RT-qPCR assay characteristics, analytical recovery performance and matrix inhibition

Standard curve characteristics for RT-qPCR assays were within the prescribed range of MIQE guidelines with slopes ranging between −3.13 and − 3.33, and PCR efficiencies between 100 and 109 %, except for ORF1ab (−3.07 and 112 %, respectively) (Table S1). The LOD (95 % positivity rate) was 10 gc.r−1 for all RT-qPCR assays including Phi 6 and PMMoV. LOD values between 5 and 50 gc.r−1 have been reported elsewhere for N, E, RdRP and ORF1ab gene targets (Muenchhoff et al., 2020). For a concentration of 1 gc.r−1 (in the linear range of the standard curves, Fig. S1), positivity rates of 70 %, 67 %, 64 %, 30 %, 50 % and 80 % were obtained for N1, N2, N3, E, RdRP, and ORF1ab assays, respectively. No amplification was observed in no template controls (NTCs) except for one out of five NTCs with the N3 assay. It has been demonstrated that the CDC N3 biomarker generates false positives in NTCs due to a design flaw leading to the complementarity between the N3 probe and the reverse primer of the CDC assay and resulting in the amplification of duplex and triplex products (Lee et al., 2021).

Wastewaters are complex matrices containing substances that can affect RT-qPCR performances if they are not properly removed during sample processing (Schrader et al., 2012). Using an exogenous inhibition control, no apparent PCR inhibition was observed in wastewater samples analysed here. Several process controls have been proposed to assess whole method recovery efficiency, such as enveloped bacteriophages (e.g. Phi 6 phage) (Ahmed et al., 2020d). Using Phi 6 RT-qPCR assay, the whole method recovery efficiency averaged 3.8 ± 1.4 %. Systematic assessment of the recovery rate using Phi 6 showed consistent method performance over the course of the experiment. Phi 6 recovery rates were not used to adjust endogenous SARS-CoV-2 concentrations because spike-and-recovery approaches may not authentically reflect the recovery of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, notably because of the short time between sample spiking and sample processing and a resulting different partitioning behaviour between both viruses (Chik et al., 2021; Kantor et al., 2021). The stronger and consistent signal of Phi 6 RNA in the aqueous phase (Table S2) compared to the particulate phase (pre-centrifugation pellet) (Table S3) tends to confirm this hypothesis. Recently, Alamin et al. (2022) reported very low detection efficiencies (0.1–4.2 %) with Phi 6, even when SARS-CoV-2 spiked in wastewater was detected with good efficiency.

3.2. Effect of temperature on the decay of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers in aqueous phase of wastewater

3.2.1. Temperature

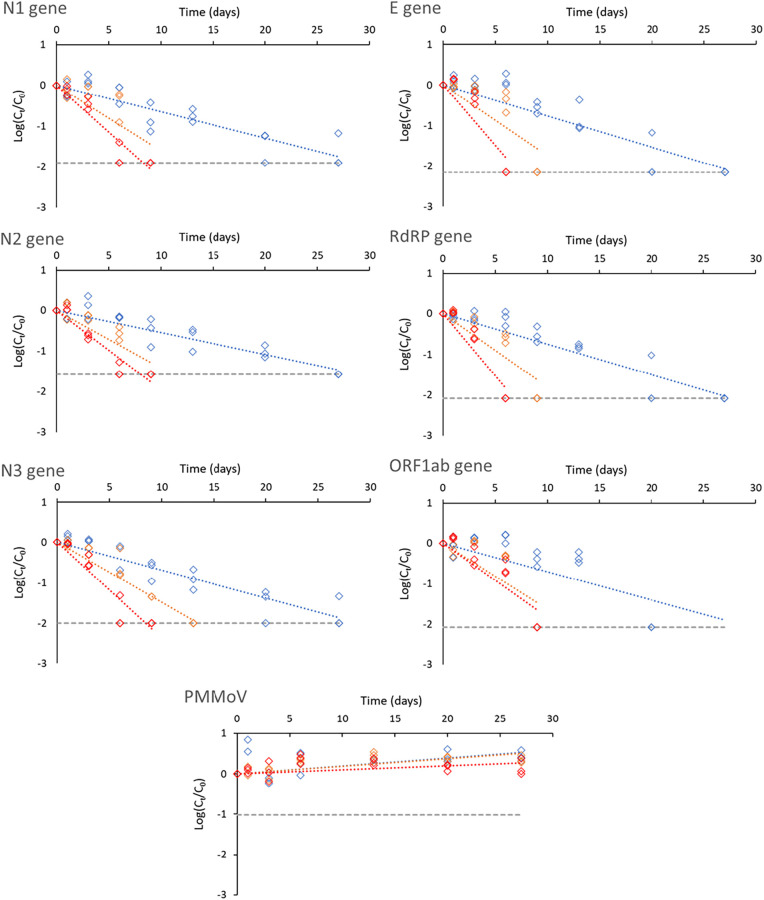

Depending on the RNA biomarker, decay slopes ranged between −0.05 and − 0.08 at 4 °C, between −0.14 and − 0.18 at 12 °C and between −0.18 and − 0.31 at 20 °C (Table 3 ). The T 90 reduction times varied between 13.0 and 18.5 days at 4 °C, between 5.5 and 7.0 days at 12 °C and between 3.3 and 5.1 days at 20 °C. As shown in Table 1, similar or even shorter persistence periods of endogenous SARS-CoV RNA biomarkers have been reported in raw wastewater at 4 °C (Weidhaas et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022). In contrast, other studies found longer persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA signals at 4 °C with T 90 values ranging from 22 to 52 days (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Hokajärvi et al., 2021). Initial SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in the latter studies were several orders of magnitude higher than in the present study. The use of high spiking doses of gamma-irradiated or patient-derived SARS-CoV-2 particles may not be representative of natural levels of SARS-CoV-2 in contaminated wastewaters, which are likely composed of a complex mixture of intact viruses, capsid-compromised viruses and free RNA. The use of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 concentrations may thus provide data that are more representative of contaminated wastewater matrices. Most data on SARS-CoV-2 persistence in wastewater have been gathered for typical fridge (4–5 °C) (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Hokajärvi et al., 2021; Medema et al., 2020a) and freezer (−20 °C and − 80 °C) (Islam et al., 2022; Markt et al., 2021) temperatures, but less is known on signal stability at higher (above 10 °C) temperatures, especially for natural virus concentrations (Table 1). Such information is essential for WBE investigations, notably in remote settings with limited logistics, where samples might be exposed to higher temperatures until they can be handled in a laboratory. We found that storage temperature has a significant effect on endogenous SARS-CoV-2 RNA persistence, as higher conservation temperatures lead to increased decay rates (Table 4 ). At 12 and 20 °C, RNA biomarker losses of 1-log10 occurred on average after 6 and 4 days, respectively (Fig. 1 ). Conservation at these higher temperatures led to a complete signal loss of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers after 6 and 13 days, respectively. In another study, no significant differences in decay rates were found between 4 and 15 °C for spiked samples, but rather between these temperatures and higher ones (25 and 37 °C) (Ahmed et al., 2020b). Other studies also reported a higher decay rate of SARS-CoV-2 RNA at temperatures above 20 °C compared to 4 °C in wastewater (Weidhaas et al., 2021, Yang et al., 2022) and settled solids (Roldan-Hernandez et al., 2022) (Table 1). A previous study on SARS-CoV-1 (using natural virus concentrations) showed that the virus was still recovered in wastewater after at least 14 days when stored at 4 °C, but that the signal remained only 2 days at 20 °C (Wang et al., 2005). Slower inactivation kinetics at 4 °C have further been reported for enveloped surrogates such as murine hepatitis virus (MHV) when compared to temperatures above 20 °C (Ye et al., 2016). In practice, our results indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarker signal remained constant for at least 6 days at 4 °C, but rapidly dropped after 1 day at 20 °C (Fig. 1). This emphasizes the need for suitable storage conditions during collection and transport of wastewater samples used in WBE, especially when local testing logistics are limited, and samples cannot be refrigerated appropriately during several days.

Table 3.

Fate of signals of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers and PMMoV at 4, 12 and 20 °C in the aqueous and particulate phases of wastewater according to temperature. ⁎The particulate phase was yielded following pelleting of the raw sample (see material and methods for details).

| Phase | Target | Temperature (°C) | Slope (± Stand. Error) | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | T90 | 95 % confidence limits (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous | E | 4 | −0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.90 | <0.0001 | 13.0 | 10.8; 14.2 |

| 12 | −0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.77 | <0.0001 | 5.7 | 4.2; 7.6 | ||

| 20 | −0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.85 | <0.0001 | 3.3 | 2.5; 4.2 | ||

| N1 | 4 | −0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.90 | <0.0001 | 15.5 | 13.3; 17.6 | |

| 12 | −0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | <0.0001 | 6.2 | 4.6; 7.9 | ||

| 20 | −0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 4.4 | 3.8; 4.9 | ||

| N2 | 4 | −0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.92 | <0.0001 | 18.5 | 16.2; 20.7 | |

| 12 | −0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.87 | <0.0001 | 7.0 | 5.6; 8.5 | ||

| 20 | −0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 5.1 | 4.5; 5.7 | ||

| N3 | 4 | −0.07 ± 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.0001 | 14.5 | 12.8; 16.2 | |

| 12 | −0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.94 | <0.0001 | 6.7 | 5.9; 7.6 | ||

| 20 | −0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.95 | <0.0001 | 4.2 | 3.7; 4.7 | ||

| RdRP | 4 | −0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.0001 | 13.0 | 11.8; 14.8 | |

| 12 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.87 | <0.0001 | 5.8 | 4.4; 6.7 | ||

| 20 | −0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.92 | <0.0001 | 3.3 | 2.7; 3.9 | ||

| ORF1ab | 4 | −0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.71 | <0.0001 | 14.3 | 10.3; 18.3 | |

| 12 | −0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.73 | <0.0001 | 6.2 | 4.2; 8.1 | ||

| 20 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.86 | <0.0001 | 5.5 | 4.3; 6.6 | ||

| PMMoV | 4 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.86 | <0.0001 | – | – | |

| 12 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.84 | <0.0001 | – | – | ||

| 20 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.0006 | – | – | ||

| Particulate⁎ | E | 4 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.49 | 0.0002 | 33.4 | 19.1; 47.7 |

| 12 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.0002 | 33.1 | 0.0; 82.2 | ||

| 20 | −0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.68 | <0.0001 | 17.6 | 0.0; 46.6 | ||

| N1 | 4 | −0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.2744 | – | – | |

| 12 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.4100 | – | – | ||

| 20 | −0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.0002 | 41.9 | 0.0; 103.3 | ||

| PMMoV | 4 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.50 | 0.0002 | – | – | |

| 12 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.73 | <0.0001 | – | – | ||

| 20 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.0025 | – | – |

Table 4.

Summary of the multivariate linear regression comparing the effects of incubation period and temperature on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV biomarkers in the aqueous phase. The intercept is set at 0 to reflect the decay rate at the start of the experiment. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

| Term | Estimate | Standard error | t Statistic | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (n = 318) | Time | −0.03 | 0.00 | −8.084 | <0.0001 |

| Time∗Temperature | −0.01 | 0.00 | −21.659 | <0.0001 | |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.8751 | ||||

| F (2, 316) | 1115 | ||||

| p-Value | <0.0001 | ||||

| PMMoV (n = 69) | Time | 0.04 | 0.00 | 8.195 | <0.0001 |

| Time∗Temperature | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.101 | 0.920 | |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.733 | ||||

| F (2, 67) | 95.73 | ||||

| p-Value | <0.0001 |

Fig. 1.

Decay of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers (N1, N2, N3, E, RdRP and ORF1ab) and PMMoV in the aqueous phase according to temperature (4, 12 and 20 °C, represented by blue, orange, and red lines, respectively). Grey dashed lines symbolise the maximum decay that can be measured (see material and methods for details). Cq values and positivity rates are summarized in Table S2.

3.2.2. RNA biomarker target

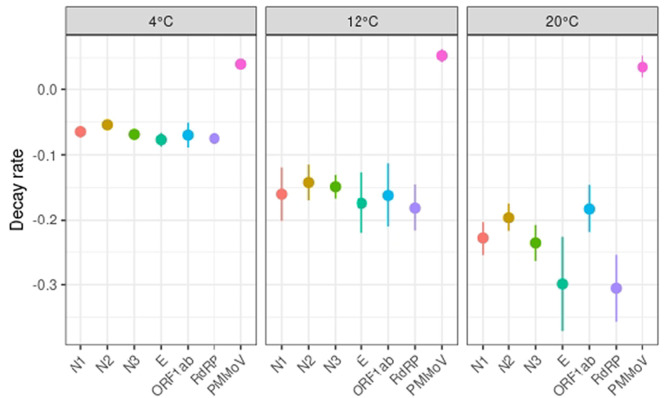

Comparative studies on the analytical performance of several SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers have been conducted in clinical settings and showed that some biomarkers outperformed others in terms of sensitivity and specificity (Nalla et al., 2020; Vogels et al., 2020). Lower sensitivities or detection failures were shown to be caused by primer/probe mismatches and single-nucleotide polymorphism (Artesi et al., 2020; Pillonel et al., 2020). Similar head-to-head comparisons using wastewater matrices is currently lacking although some differences between SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers have been reported during quantification in wastewater (Chavarria-Miró et al., 2021; Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2021). The choice of the RNA biomarker target for WBE investigations of SARS-CoV-2 can be responsible for variable outcomes in terms of viral load estimates and positivity rates because of different RT-qPCR assay sensitivities (Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2021). Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers in wastewater has been tested using up to three different primer sets, usually N1, N2 or E (Table 1) (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Boogaerts et al., 2021; Hokajärvi et al., 2021). A slightly more rapid decay of the N2 assay target compared to the E-Sarbeco assay target was reported, indicating a possible difference in decay rates of nucleocapsid and envelope genes (Hokajärvi et al., 2021). On the contrary, Boogaerts et al. (2021) reported a higher in-sample stability of the N2 target compared to the E-Sarbecco target. Ho et al. (2022) measured SARS-CoV-2 persistence in wastewater using RdRP and ORF1ab genes at 20 °C, but no decay rate was reported (Table 1). For the six RNA biomarkers assessed in this study, some differences were observed. Pairwise comparison of the decay rates of the SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers showed that there is no overlap between the 95 % confidence intervals of N2 and the N3, E and RdPR biomarkers at 4 °C. While these differences might be significant statistically, the decay rates can be considered similar in practice given the short range of these decay rates compared to those of higher storage temperatures (Fig. 3). Decay rates were similar at 12 °C for all the SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers. At 20 °C, differences were observed between N2 and the E and RdPR biomarkers and between N1 and RdPR (Fig. 3). Besides decay rates, differences were observed in terms of positivity rate over time (Table S2). At 4 °C, the most persistent and consistent RNA signal was achieved by N biomarkers followed by equal performance of E and RdRP biomarkers (Table S2). Complete signal loss was observed after 13 days for the ORF1ab biomarker, compared to 20 to 27 days for other RNA biomarkers, although the RNA signal strength remained rather constant until day 9 (Fig. 1). At 12 °C, the N3 gene was still detected after 9 days, whereas the signal for all other RNA biomarkers was lost. At 20 °C, all RNA biomarkers were detected after 3 days but only N biomarkers and ORF1ab could be detected after 6 days (Table S1). CDC primer sets N1 and N2 have been most frequently used in WBE studies (Bivins et al., 2021) and previous studies have found that they yielded the highest sensitivity, both in clinical and environmental settings (Kaya et al., 2022; Pérez-Cataluña et al., 2021; Vogels et al., 2020). Furthermore, differences between N1 and N2 assay sensitivities appeared to be minimal, compared to other sources of analytical variability (LaTurner et al., 2021; Pecson et al., 2021). We observed similar results for RNA biomarker persistence, but in contrast to previous reports (Boogaerts et al., 2021; Randazzo et al., 2020; Vogels et al., 2020), the additional N3 primer set performed equally well as N1 and N2. In fact, the three primer sets targeting the nucleocapsid achieved very similar standard curve characteristics (Table S1, Fig. S1) as well as decay slopes and T90 values (Table 2). The fact that PCR amplification was observed in one out of five no template controls with the N3 assay suggests though that N3 assay may be less appropriate for WBE due to possible false positives (Hong et al., 2021). Overall, all the tested RNA biomarkers enabled to consistently detect SARS-CoV-2 during the first 6 days when samples were stored at 4 °C.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the decay rates of the SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV biomarkers in aqueous phase (average ± their 95 % confidence intervals) for the three incubation temperatures.

3.3. Fate of PMMoV in raw wastewater

PMMoV is the most abundant RNA virus in human faeces, and it is prevalent in wastewaters at high levels; it has thus been suggested as a viral water quality indicator (Kitajima et al., 2018). Like SARS-CoV-2, PMMoV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, but its structure and size substantially differ from SARS-CoV-2. It may thus provide an inaccurate estimation of recovery and should rather be used as a qualitative control to monitor sample-to-sample variability or to check the successful extraction of RNA from wastewater samples (Wu et al., 2020a). Since many WBE studies use PMMoV for normalisation of SARS-CoV-2 data (D'Aoust et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2020a), it is essential to ensure that the RNA signal from both viruses behave similarly. Its persistence has been measured in controlled laboratory conditions for river water and marine water, but data for wastewater matrices are currently very scarce (Kitajima et al., 2018). Here, we assessed the fate of PMMoV RNA signal in raw wastewater and compared it to that of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers during 27 days at three different temperatures. PMMoV was very persistent over the 27-day incubation period (Fig. 3) since no apparent decay was observed regardless of the storage temperature (Table 4) or the phase used for viral RNA extraction (Table 5 ). Most notably, the persistence of PMMoV in wastewater was higher than that of SARS-CoV-2 during the 4-week experiment (Fig. 3). A recent study highlighted the high persistence of PMMoV RNA in settled solids at different temperatures, with decay rates varying between 0.01 and 0.09 days−1 (Roldan-Hernandez et al., 2022). Another study analysed the percent change in PMMoV signal after 7 and 14 days of sample storage at 4 °C and found an increase in some of the tested raw wastewater matrices (Islam et al., 2022). A similar increase of PMMoV was observed in our study within 4 weeks at the three incubation temperatures. PMMoV concentration increase over time could result from a change in the wastewater matrix during the incubation that would lead to an improved detection performance of PMMoV or a release of PMMoV particles from the particulate phase over time due to continuous stirring in the microcosms.

Table 5.

Summary of the multivariate linear regression comparing the effect of aqueous and particulate phases on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 (E and N1 only) and PMMoV biomarkers. The intercept is set at 0 to reflect the decay rate at the start of the experiment. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

| Term | Estimate | Standard error | t Statistic | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (n = 228) | Time | −0.03 | 0.01 | −3.657 | 0.0003 |

| Time∗Phase | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.0588 | |

| Time∗Temperature | −0.01 | 0.00 | −10.834 | <0.0001 | |

| Time∗Temperature∗Phase | 0.01 | 0.00 | 8.847 | <0.0001 | |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.7391 | ||||

| F (4, 224) | 162.5 | ||||

| p-Value | <0.0001 | ||||

| PMMoV (n = 130) | Time | 0.04 | 0.00 | 9.189 | <0.0001 |

| Time∗Phase | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.114 | 0.9098 | |

| Time∗Temperature | −0.02 | 0.00 | −2.878 | 0.0047 | |

| Time∗Temperature∗Phase | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.988 | 0.3249 | |

| Adjusted-R2 | 0.6902 | ||||

| F (4, 126) | 73.41 | ||||

| p-Value | <0.0001 |

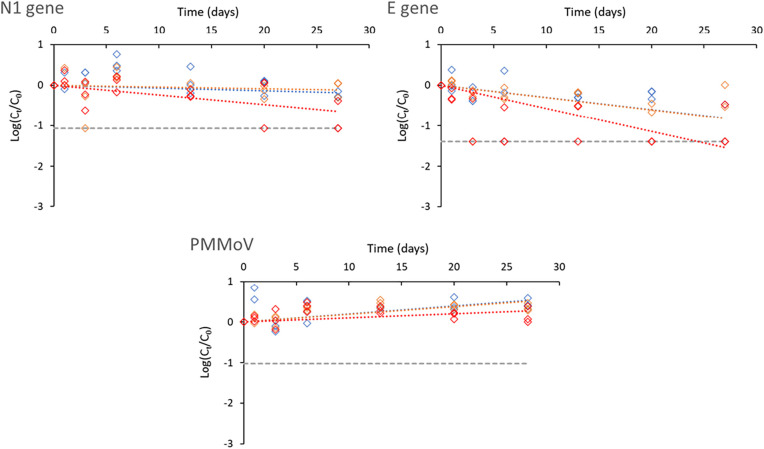

3.4. Fate of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers and PMMoV in the aqueous phase vs particulate phase

Studies on the fate of the RNA biomarkers have predominantly focused either on the whole sample (small volumes, high spiking doses) (Ahmed et al., 2020b; Bivins et al., 2020) or on the aqueous phase after pelleting large particles and debris (Boogaerts et al., 2021; Hokajärvi et al., 2021). A pre-centrifugation step is often added to SARS-CoV-2 detection workflows in raw wastewater, which aims at removing large debris and particles and limit potential interferences during the downstream molecular analytical steps. The resulting pellet is usually discarded, and limited knowledge exists on the concentration and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 as well as PMMoV in this phase. A recent study assessed the fate of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers in biosolids (Roldan-Hernandez et al., 2022). It is however still unknown if and to what extent the fate of SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV is differentially affected in the aqueous and particulate phases of wastewater samples. As shown in the results summarized in Table 5, the fate of the RNA signal for SARS-CoV-2 (N1 and E biomarkers) was significantly different between the aqueous and particulate phases. In the aqueous phase, the decay rate is considerable and accelerates as temperature increases as shown above (Table 5). Although the initial RNA signal was comparatively lower (higher Cq values) in the particulate phase, RNA signals were still measurable after 27 days for both biomarkers, especially at 4 and 12 °C (Fig. 2 ). In other words, the signal in the particulate phase is much more stable and is not as impacted by temperature as in the aqueous phase. This is captured in our model by the significant three-way interaction between time, temperature, and phase (Table 5). In contrast, the PMMoV signals remain highly persistent in both the aqueous and particulate phases unlike those measured for SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). This is reflected by the very small regression coefficients and the non-significant three-way interaction (Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Decay of SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers (N1, E) and PMMoV in the particulate phase according to temperature (4, 12 and 20 °C, represented by blue, orange, and red lines, respectively). Grey dashed lines symbolise the maximum decay that can be measured (see material and methods for details). Cq values and positivity rates are summarized in Table S2.

3.5. Concluding remarks

The present study was performed to investigate the comparative persistence of 6 SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers and PMMoV in wastewater at three different temperatures over 4 weeks. Given that these results were generated on one wastewater sample, similar comparative efforts using additional matrices would be valuable to confirm the trends observed here. Most studies on persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater (or settled solids) have been performed at fridge temperature and using a limited number of biomarkers (Table 1). Over the 27-day time series, we identified some differences in persistence among the selected SARS-CoV-2 biomarkers, particularly at 20 °C. We further confirm that the persistence of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 in raw sewage is temperature dependent, as shown by previous results using SARS-CoV-2 spiking (Ahmed et al., 2020b). Assessment of in-sample stability of RNA biomarkers in sewage is comparatively more challenging for endogenous SARS-CoV-2 concentrations than for spiked ones because of the proximity to the RT-qPCR assay LOD (Boogaerts et al., 2021). The information retrieved from such experiments is essential though for appraising RNA biomarker stability under real-world conditions. Unlike SARS-CoV-2, PMMoV was very persistent over the 27-day incubation period since no apparent decay was observed regardless of the storage temperature or the phase used for viral RNA extraction. Although at 4 °C the difference in decay dynamics between SARS-CoV-2 and PMMoV appears to be minor within the first 6 days, both in the aqueous and particulate phases, this is no longer true for higher temperatures (12 and 20 °C) and for higher storage time periods. The significant differences in decay observed here between both viruses could be a source of underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 concentrations when PMMoV is used to normalise the SARS-CoV-2 signal. Caution must therefore be taken when using such an approach and further investigations are needed to confirm or not the relevance of using PMMoV as a normalisation control. On the other hand, the use of PMMoV as process control (to assess concentration and RNA extraction efficiencies, and to identify false negatives and false positives) is not questioned here and would be applicable as previously described (Alamin et al., 2022).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jean-Baptiste Burnet: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Henry-Michel Cauchie: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Cécile Walczak: Formal analysis. Nathalie Goeders: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Leslie Ogorzaly: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the technical staff of Luxembourg wastewater treatment plant for assistance in wastewater sample collection, and Chantal Snoeck from the Luxembourg Institute of Health (LIH) for the transfer of the RT-qPCR assays targeting the E and N1 genes. This work was also supported by the European Virus Archive Global (EVA-GLOBAL) project by providing SARS-CoV-2 positive control. This work was financially supported by the Fondation André Losch and by the Fonds National de la Recherche (FNR) under FNR COVID-19 project 14806023 (CORONASTEP+).

Editor: Warish Ahmed

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159401.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Ahmed W., Angel N., Edson J., Bibby K., Bivins A., O'Brien J.W., Choi P.M., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Li J., Tscharke B., Verhagen R., Smith W.J.M., Zaugg J., Dierens L., Hugenholtz P., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. First confirmed detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewater in Australia: a proof of concept for the wastewater surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Haramoto E., Hewitt J., Huygens F., Gyawali P., Korajkic A., Riddell S., Sherchan S.P., Simpson S.L., Sirikanchana K., Symonds E.M., Verhagen R., Vasan S.S., Kitajima M., Bivins A. Decay of SARS-CoV-2 and surrogate murine hepatitis virus RNA in untreated wastewater to inform application in wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bertsch P.M., Bivins A., Bibby K., Farkas K., Gathercole A., Haramoto E., Gyawali P., Korajkic A., McMinn B.R., Mueller J.F., Simpson S.L., Smith W.J.M., Symonds E.M., Thomas K.V., Verhagen R., Kitajima M. Comparison of virus concentration methods for the RT-qPCR-based recovery of murine hepatitis virus, a surrogate for SARS-CoV-2 from untreated wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;739 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bivins A., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Choi P.M., Farkas K., Gyawali P., Hamilton K.A., Haramoto E., Kitajima M., Simpson S.L., Tandukar S., Thomas K.V., Mueller J.F. Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater: methods optimization and quality control are crucial for generating reliable public health information. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health. 2020;17:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Bivins A., Bertsch P.M., Bibby K., Gyawali P., Sherchan S.P., Simpson S.L., Thomas K.V., Verhagen R., Kitajima M., Mueller J.F., Korajkic A. Intraday variability of indicator and pathogenic viruses in 1-h and 24-h composite wastewater samples: implications for wastewater-based epidemiology. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed W., Smith W.J.M., Metcalfe S., Jackson G., Choi P.M., Morrison M., Field D., Gyawali P., Bivins A., Bibby K., Simpson S.L. Comparison of RT-qPCR and RT-dPCR platforms for the trace detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater. ACS ES&T Water. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.1c00387. acsestwater.1c00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamin M., Tsuji S., Hata A., Hara-Yamamura H., Honda R. Selection of surrogate viruses for process control in detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;823 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoah I.D., Kumari S., Bux F. Coronaviruses in wastewater processes: source, fate and potential risks. Environ. Int. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artesi M., Bontems S., Göbbels P., Franckh M., Maes P., Boreux R., Meex C., Melin P., Hayette M.-P., Bours V., Durkin K., Caliendo A.M. A recurrent mutation at position 26340 of SARS-CoV-2 is associated with failure of the E gene quantitative reverse transcription-PCR utilized in a commercial dual-target diagnostic assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(10) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01598-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand I., Challant J., Jeulin H., Hartard C., Mathieu L., Lopez S., Schvoerer E., Courtois S., Gantzer C. Epidemiological surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 by genome quantification in wastewater applied to a city in the northeast of France: comparison of ultrafiltration- and protein precipitation-based methods. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2021;233 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2021.113692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., Greaves J., Fischer R., Yinda K.C., Ahmed W., Kitajima M., Munster V.J., Bibby K. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7(12):937–942. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., North D., Wu Z., Shaffer M., Ahmed W., Bibby K. Within- and between-day variability of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in municipal wastewater during periods of varying COVID-19 prevalence and positivity. ACS ES&T Water. 2021;1(9):2097–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaerts T., Jacobs L., De Roeck N., Van den Bogaert S., Aertgeerts B., Lahousse L., van Nuijs A.L.N., Delputte P. An alternative approach for bioanalytical assay optimization for wastewater-based epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;789 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S.A., Benes V., Garson J.A., Hellemans J., Huggett J., Kubista M., Mueller R., Nolan T., Pfaffl M.W., Shipley G.L., Vandesompele J., Wittwer C.T. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55(4):611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Franco D., Orschler L., Lackner S., Agrawal S., Weissbrodt D.G. Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in sewage: toward sentinels with analytical accuracy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;804 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova L., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water. Water Res. 2009;43(7):1893–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) - Real-Time RT-PCR Panel Primers and Probes. [Google Scholar]

- Chavarria-Miró G., Anfruns-Estrada E., Martínez-Velázquez A., Vázquez-Portero M., Guix S., Paraira M., Galofré B., Sánchez G., Pintó R.M., Bosch A., Elkins C.A. Time evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in wastewater during the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 in the metropolitan area of BarcelonaSpain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021;87(7) doi: 10.1128/AEM.02750-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chik A.H.S., Glier M.B., Servos M., Mangat C.S., Pang X.-L., Qiu Y., D'Aoust P.M., Burnet J.-B., Delatolla R., Dorner S., Geng Q., Giesy J.P., McKay R.M., Mulvey M.R., Prystajecky N., Srikanthan N., Xie Y., Conant B., Hrudey S.E. Comparison of approaches to quantify SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater using RT-qPCR: results and implications from a collaborative inter-laboratory study in Canada. J. Environ. Sci. 2021;107:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2021.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K.W., Bleicker T., Brunink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Mulders D., Haagmans B.L., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P.G., Drosten C. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aoust P.M., Mercier E., Montpetit D., Jia J.-J., Alexandrov I., Neault N., Baig A.T., Mayne J., Zhang X., Alain T., Langlois M.-A., Servos M.R., MacKenzie M., Figeys D., MacKenzie A.E., Graber T.E., Delatolla R. Quantitative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from wastewater solids in communities with low COVID-19 incidence and prevalence. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira L.C., Torres-Franco A.F., Lopes B.C., Costa E.A., Costa M.S., Reis M.T.P., Melo M.C., Polizzi R.B., Teixeira M.M., Mota C.R., Santos B.S.Á.D.S. Viability of SARS-CoV-2 in river water and wastewater at different temperatures and solids content. Water Res. 2021;195:117002. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forés E., Bofill-Mas S., Itarte M., Martínez-Puchol S., Hundesa A., Calvo M., Borrego C.M., Corominas L.L., Girones R., Rusiñol M. Evaluation of two rapid ultrafiltration-based methods for SARS-CoV-2 concentration from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;768 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Weisberg S. Third edition. Sage Publication; Oaks CA: 2019. An R Companion to Applied Regression. [Google Scholar]

- Gendron L., Verreault D., Veillette M., Moineau S., Duchaine C. Evaluation of filters for the sampling and quantification of RNA phage aerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2010;44(10):893–901. [Google Scholar]

- Green H.C., Shanks O.C., Sivaganesan M., Haugland R.A., Field K.G. Differential decay of human faecal bacteroides in marine and freshwater. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;13(12):3235–3249. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundy P.M., Gerba C.P., Pepper I.L. Survival of coronaviruses in water and wastewater. Food Environ. Virol. 2008;1(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- Haramoto E., Malla B., Thakali O., Kitajima M. First environmental surveillance for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and river water in Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart O.E., Halden R.U. Computational analysis of SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 surveillance by wastewater-based epidemiology locally and globally: feasibility, economy, opportunities and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan S.W., Ibrahim Y., Daou M., Kannout H., Jan N., Lopes A., Alsafar H., Yousef A.F. Detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and treated effluents: surveillance of COVID-19 epidemic in the United Arab Emirates. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;764 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J., Stange C., Suhrborg R., Wurzbacher C., Drewes J.E., Tiehm A. SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance in Germany: long-term RT-digital droplet PCR monitoring, suitability of primer/probe combinations and biomarker stability. Water Res. 2022;210 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokajärvi A.-M., Rytkönen A., Tiwari A., Kauppinen A., Oikarinen S., Lehto K.-M., Kankaanpää A., Gunnar T., Al-Hello H., Blomqvist S., Miettinen I.T., Savolainen-Kopra C., Pitkänen T. The detection and stability of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA biomarkers in wastewater influent in Helsinki, Finland. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;770 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong P.-Y., Rachmadi A.T., Mantilla-Calderon D., Alkahtani M., Bashawri Y.M., Al Qarni H., O'Reilly K.M., Zhou J. Estimating the minimum number of SARS-CoV-2 infected cases needed to detect viral RNA in wastewater: to what extent of the outbreak can surveillance of wastewater tell us? Environ. Res. 2021;195 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T., Bretz F., Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom. J. 2008;50(3):346–363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam G., Gedge A., Lara-Jacobo L., Kirkwood A., Simmons D., Desaulniers J.-P. Pasteurization, storage conditions and viral concentration methods influence RT-qPCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;821 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor R.S., Nelson K.L., Greenwald H.D., Kennedy L.C. Challenges in measuring the recovery of SARS-CoV-2 from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021;55(6):3514–3519. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c08210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya D., Niemeier D., Ahmed W., Kjellerup B.V. Evaluation of multiple analytical methods for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in wastewater samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;808 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima M., Sassi H.P., Torrey J.R. Pepper mild mottle virus as a water quality indicator. Npj cleanWater. 2018;1(1):19. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Joshi M., Patel A.K., Joshi C.G. Unravelling the early warning capability of wastewater surveillance for COVID-19: a temporal study on SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and need for the escalation. Environ. Res. 2021;196 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Iaconelli M., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. First detection of SARS-CoV-2 in untreated wastewaters in Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;736 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa G., Mancini P., Bonanno Ferraro G., Veneri C., Iaconelli M., Bonadonna L., Lucentini L., Suffredini E. SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating in northern Italy since december 2019: evidence from environmental monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;750 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaTurner Z.W., Zong D.M., Kalvapalle P., Gamas K.R., Terwilliger A., Crosby T., Ali P., Avadhanula V., Santos H.H., Weesner K., Hopkins L., Piedra P.A., Maresso A.W., Stadler L.B. Evaluating recovery, cost, and throughput of different concentration methods for SARS-CoV-2 wastewater-based epidemiology. Water Res. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.S., Goldstein J.M., Moon J.L., Herzegh O., Bagarozzi D.A., Jr., Oberste M.S., Hughes H., Bedi K., Gerard D., Cameron B., Benton C., Chida A., Ahmad A., Petway D.J., Jr., Tang X., Sulaiman N., Teklu D., Batra D., Howard D., Sheth M., Kuhnert W., Bialek S.R., Hutson C.L., Pohl J., Carroll D.S. Analysis of the initial lot of the CDC 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel. PLoS One. 2021;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.W., Xin Z.T., Wang X.W., Zheng J.L., Chao F.H. Mechanisms of inactivation of hepatitis a virus in water by chlorine dioxide. Water Res. 2004;38(6):1514–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markt R., Mayr M., Peer E., Wagner A.O., Lackner N., Insam H. Detection and stability of SARS-CoV-2 fragments in wastewater: impact of storage temperature. Pathogens. 2021;10(9):1215. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Been F., Heijnen L., Petterson S. Implementation of environmental surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 virus to support public health decisions: opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health. 2020;17:49–71. doi: 10.1016/j.coesh.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema G., Heijnen L., Elsinga G., Italiaander R., Brouwer A. Presence of SARS-Coronavirus-2 RNA in sewage and correlation with reported COVID-19 prevalence in the early stage of the epidemic in the Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7(7):511–516. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura F., Kitajima M., Omori R. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding in faeces as a parameter for wastewater-based epidemiology: re-analysis of patient data using a shedding dynamics model. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;769 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenchhoff M., Mairhofer H., Nitschko H., Grzimek-Koschewa N., Hoffmann D., Berger A., Rabenau H., Widera M., Ackermann N., Konrad R., Zange S., Graf A., Krebs S., Blum H., Sing A., Liebl B., Wölfel R., Ciesek S., Drosten C., Protzer U., Boehm S., Keppler O.T. Multicentre comparison of quantitative PCR-based assays to detect SARS-CoV-2, Germany, March 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(24) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.24.2001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalla A.K., Casto A.M., Huang M.-L.W., Perchetti G.A., Sampoleo R., Shrestha L., Wei Y., Zhu H., Jerome K.R., Greninger A.L., McAdam A.J. Comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 detection assays using seven different primer-probe sets and one assay kit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(6) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00557-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogorzaly L., Bertrand I., Paris M., Maul A., Gantzer C. Occurrence, survival, and persistence of human adenoviruses and F-specific RNA phages in raw groundwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76(24):8019–8025. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00917-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.A., Shisler J.L., Mariñas B.J. Mechanistic aspects of Adenovirus serotype 2 inactivation with free chlorine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76(9):2946–2954. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02267-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecson B.M., Darby E., Haas C.N., Amha Y.M., Bartolo M., Danielson R., Dearborn Y., Di Giovanni G., Ferguson C., Fevig S., Gaddis E., Gray D., Lukasik G., Mull B., Olivas L., Olivieri A., Qu Y., Consortium S.A.-C.-I. Reproducibility and sensitivity of 36 methods to quantify the SARS-CoV-2 genetic signal in raw wastewater: findings from an interlaboratory methods evaluation in the U.S. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 2021;7(3):504–520. doi: 10.1039/d0ew00946f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cataluña A., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Randazzo W., Falcó I., Allende A., Sánchez G. Comparing analytical methods to detect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;758 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillonel T., Scherz V., Jaton K., Greub G., Bertelli C. Letter to the editor: SARS-CoV-2 detection by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(21) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.21.2000880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio D., Kemp F., Magni S., Ogorzaly L., Cauchie H.-M., Gonçalves J., Skupin A., Aalto A. Model-based assessment of COVID-19 epidemic dynamics by wastewater analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;827 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Z., Ye Y., Szczuka A., Harrison K.R., Dodd M.C., Wigginton K.R. Reactivity of viral nucleic acids with chlorine and the impact of virus encapsidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56(1):218–227. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c04239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo W., Truchado P., Cuevas-Ferrando E., Simón P., Allende A., Sánchez G. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area. Water Res. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relova D., Rios L., Acevedo A.M., Coronado L., Perera C.L., Pérez L.J. Impact of RNA degradation on viral diagnosis: an understated but essential step for the successful establishment of a diagnosis network. Vet. Sci. 2018;5(1):19. doi: 10.3390/vetsci5010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockey N., Young S., Kohn T., Pecson B., Wobus C.E., Raskin L., Wigginton K.R. UV disinfection of human norovirus: evaluating infectivity using a genome-wide PCR-based approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54(5):2851–2858. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b05747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldan-Hernandez L., Graham K.E., Duong D., Boehm A.B. Persistence of endogenous SARS-CoV-2 and pepper mild mottle virus RNA in wastewater-settled solids. ACS Environ. Sci. Technol. Water. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acsestwater.2c00003. acsestwater.2c00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakarovitch C., Schlosser O., Courtois S., Proust-Lima C., Couallier J., Pétrau A., Litrico X., Loret J.-F. Monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: what normalisation for improved understanding of epidemic trends? J. Water Health. 2022;20(4):712–726. doi: 10.2166/wh.2022.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala-Comorera L., Reynolds L.J., Martin N.A., O'Sullivan J.J., Meijer W.G., Fletcher N.F. Decay of infectious SARS-CoV-2 and surrogates in aquatic environments. Water Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet J.M., Prather K., Benjamin G., Lakdawala S., Lowe J.-M., Reingold A., Volckens J., Marr L.C. Airborne transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): what we know. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73(10):1924–1926. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader C., Schielke A., Ellerbroek L., Johne R. PCR inhibitors: occurrence, properties and removal. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;113(5):1014–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman A.I., Boehm A.B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the persistence and disinfection of human coronaviruses and their viral surrogates in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7(8):544–553. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A., Topol A., White B.J., Wolfe M.K., Wigginton K.R., Boehm A.B. Effect of storage conditions on SARS-CoV-2 RNA quantification in wastewater solids. PeerJ. 2021;9 doi: 10.7717/peerj.11933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaganesan M., Haugland R.A., Chern E.C., Shanks O.C. Improved strategies and optimization of calibration models for real-time PCR absolute quantification. Water Res. 2010;44(16):4726–4735. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Kauppinen A., Pitkänen T. Decay of enterococcus faecalis, vibrio cholerae and ms2 coliphage in a laboratory mesocosm under brackish beach conditions. Front. Public Health. 2019;7 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels C.B.F., Brito A.F., Wyllie A.L., Fauver J.R., Ott I.M., Kalinich C.C., Petrone M.E., Casanovas-Massana A., Catherine Muenker M., Moore A.J., Klein J., Lu P., Lu-Culligan A., Jiang X., Kim D.J., Kudo E., Mao T., Moriyama M., Oh J.E., Park A., Silva J., Song E., Takahashi T., Taura M., Tokuyama M., Venkataraman A., Weizman O.-E., Wong P., Yang Y., Cheemarla N.R., White E.B., Lapidus S., Earnest R., Geng B., Vijayakumar P., Odio C., Fournier J., Bermejo S., Farhadian S., Dela Cruz C.S., Iwasaki A., Ko A.I., Landry M.L., Foxman E.F., Grubaugh N.D. Analytical sensitivity and efficiency comparisons of SARS-CoV-2 RT–qPCR primer–probe sets. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5(10):1299–1305. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0761-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.W., Li J.S., Guo T.K., Zhen B., Kong Q.X., Yi B., Li Z., Song N., Jin M., Xiao W.J., Zhu X.M., Gu C.Q., Yin J., Wei W., Yao W., Liu C., Li J.F., Ou G.R., Wang M.N., Fang T.Y., Wang G.J., Qiu Y.H., Wu H.H., Chao F.H., Li J.W. Concentration and detection of SARS coronavirus in sewage from Xiao Tang Shan Hospital and the 309th Hospital. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;128(1–2):156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidhaas J., Aanderud Z.T., Roper D.K., VanDerslice J., Gaddis E.B., Ostermiller J., Hoffman K., Jamal R., Heck P., Zhang Y., Torgersen K., Laan J.V., LaCross N. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater with COVID-19 disease burden in sewersheds. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;775 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H., Averick M., Bryan J., Chang W., D'agostino McGowan L., François R., Grolemund G., Hayes A., Henry L., Hester J., Kuhn M., Lin Pedersen T., Miller E., Milton Bache S., Müller K., Ooms J., Robinson D., DP S., Spinu V., Takahashi K., Vaughan D., Wilke C., Woo K., Yutani H. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019;4(43):1686. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhang J., Xiao A., Gu X., Lee Wei L., Armas F., Kauffman K., Hanage W., Matus M., Ghaeli N., Endo N., Duvallet C., Poyet M., Moniz K., Washburne Alex D., Erickson Timothy B., Chai Peter R., Thompson J., Alm Eric J., Gilbert Jack A. SARS-CoV-2 titers in wastewater are higher than expected from clinically confirmed cases. mSystems. 2020;5(4) doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00614-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Guo C., Tang L., Hong Z., Zhou J., Dong X., Yin H., Xiao Q., Tang Y., Qu X., Kuang L., Fang X., Mishra N., Lu J., Shan H., Jiang G., Huang X. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5(5):434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Marechal V., Mouchel J., Maday Y., Teyssou R., Richard E., Almayrac J., Moulin L. Evaluation of lockdown effect on SARS-CoV-2 dynamics through viral genome quantification in waste water, Greater Paris, France, 5 March to 23 April 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(50) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.50.2000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., Waldman P., Ferrier-Rembert A., Frenois-Veyrat G., Mouchel J.M., Boni M., Maday Y., Marechal V., Moulin L. Several forms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be detected in wastewaters: implication for wastewater-based epidemiology and risk assessment. Water Res. 2021;198 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Dong Q., Li S., Cheng Z., Kang X., Ren D., Xu C., Zhou X., Liang P., Sun L., Zhao J., Jiao Y., Han T., Liu Y., Qian Y., Liu Y., Huang X., Qu J. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater after the end of the COVID-19 epidemics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022;429 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Ellenberg R.M., Graham K.E., Wigginton K.R. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50(10):5077–5085. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.