Abstract

The versatility of RNA in sensing and interacting with small molecules, proteins and other nucleic acids while encoding genetic instructions for protein translation makes it a powerful substrate for engineering biological systems. RNA devices integrate cellular information sensing, processing and actuation of specific signals into defined functions and have yielded programmable biological systems and novel therapeutics of increasing sophistication. However, challenges centred on expanding the range of analytes that can be sensed and adding new mechanisms of action have hindered the full realization of the field’s promise. Here, we describe recent advances that address these limitations and point to a significant maturation of synthetic RNA-based devices.

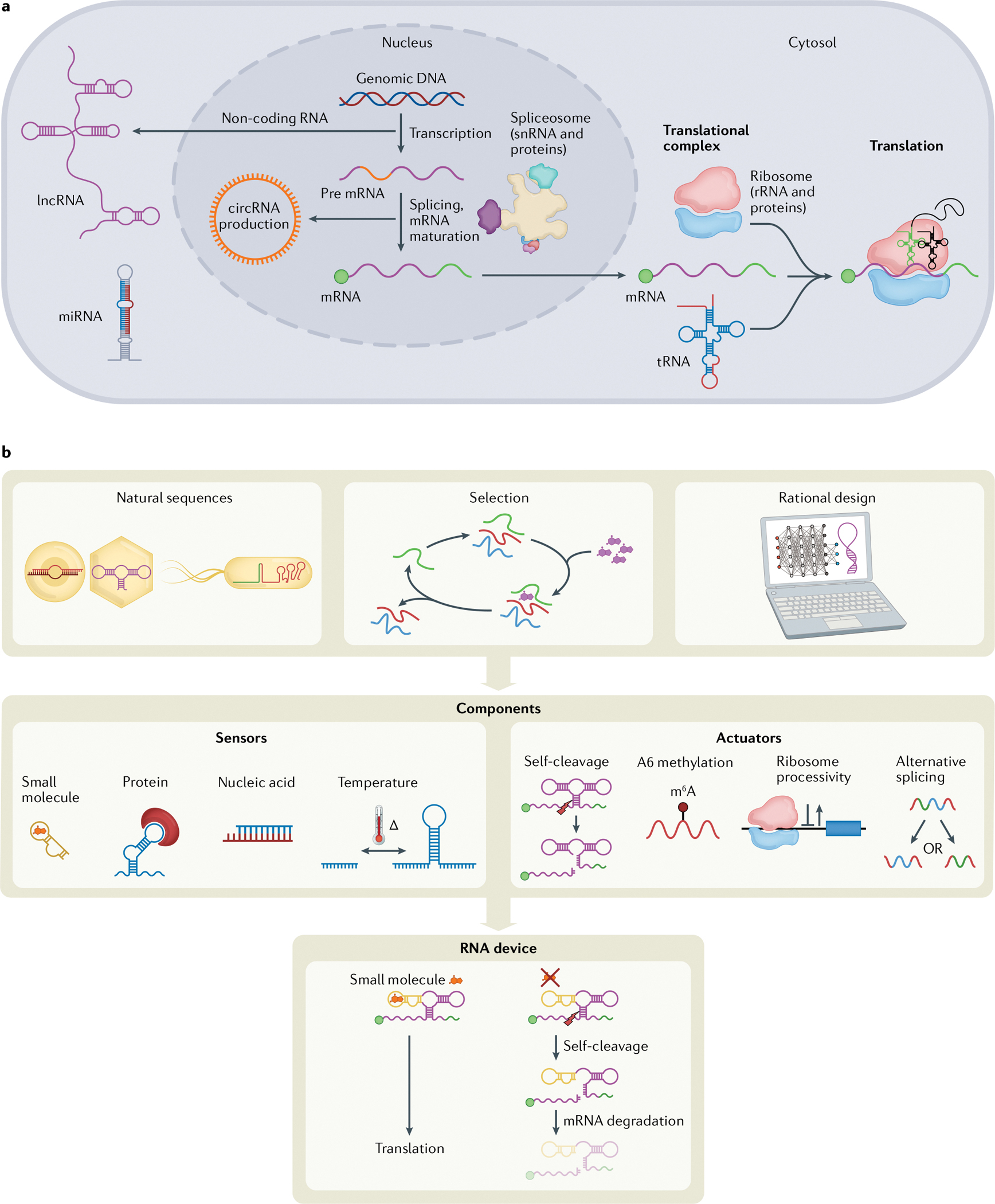

RNA is more than a messenger. Genetics research has not only cemented the principles of gene expression control — that RNA molecules transmit genetic information between DNA and protein — but also uncovered the significant role that RNA plays in directly regulating cell behaviour (FIG. 1a). Because of its structural flexibility and ability to sense and interact with a range of inputs, RNA has proven to be an important tool in engineering research and sits on the precipice of widespread application on a par with that of proteins and DNA.

Fig. 1 |. RNA cellular functions.

a | Following transcription, mRNAs are spliced by the spliceosome, a complex of small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and proteins, and matured by the addition of markers such as a 5′ cap (green circle) and polyA tail (green line)147,148. Outside the nucleus, the canonical function of RNA is the combination of tRNAs, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) (with accompanying ribosomal proteins, making up the ribosome) and mRNAs to form translational complexes that produce most cellular proteins. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are RNA molecules that form naturally via lariat intermediates as a splicing by-product149. RNA regulation of cellular processes can be accomplished by circRNAs, as well as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) that can regulate levels of exogenous RNA, endogenous RNA and protein expression150,151. b | RNA device engineering. Parts for RNA devices can be obtained by mining natural sequences, selection experiments or rational design of sequences. Sensing and actuating components can be characterized and combined to form an RNA device with both sensing and actuation capabilities.

Sensor.

An element that can detect signals, including nucleic acid sequences, proteins, small molecules or non-biological stimuli such as temperature and light.

Actuator.

An element that can control a process or event.

Synthetic biologists take inspiration from diverse fields of engineering to develop frameworks for the design, construction and characterization of new biological systems1–4. A core concept is the engineering of systems that can receive an input signal (via a sensor), perform an operation and generate an interpretable output (via an actuator)5. Endeavours to engineer RNA benefit from customizable ligand-sensing and gene-regulatory RNA elements and tunable response characteristics. The advantageous qualities of RNA have led to the development of diverse synthetic RNA devices that sense, process and act upon genetic and molecular information6 (FIG. 1b).

Gene-regulatory RNA elements.

RNA elements that control expression of a gene.

RNA devices.

Engineered genetically encoded RNA elements that combine sensing and actuation activities.

Riboswitches.

Natural RNA elements that conditionally regulate gene expression in response to binding of a small molecule.

Early RNA gene control elements were developed shortly after the discovery of functional riboswitches in nature7–9. Owing to the central role of RNA in gene expression, many of these initial engineered systems focused on regulating translation to affect protein levels7,8,10. Further advances generated RNA devices that integrated sensing and control activities and enabled more precise modulation of cellular functions11. But whereas the RNA engineering field matured, several limitations persisted. One long-standing challenge in RNA device engineering is the limited set of analytes that can be sensed by RNA aptamers due to limitations in our ability to predict or select for sequences that can bind and report binding. Having diverse options for selecting an input ligand tailored to a given system is important to advance applications and RNA engineering approaches have not yet scaled sensor development. However, recent developments in high-throughput strategies for generating RNA components that sense new analytes may rapidly change the landscape12.

Another major challenge has been the limited mechanisms of action by which synthetic RNA devices can meaningfully affect cell function. Early RNA devices that focused on the modulation of mRNA levels and translational efficiency within cells10 tapped into a small subset of the wider possibilities for RNA modulation. Recently, novel design techniques around protein translation have demonstrated strategies that can achieve increased dynamic range and temporal control13–16. Furthermore, approaches such as the use of synthetic components to harness natural processes and the de novo utilization of RNA for novel and artificial cellular functions showcase advanced mechanisms that open new avenues for the future of RNA engineering14,17.

In this Review, we discuss current applications of RNA devices spanning research, biomanufacturing and clinical uses. We then review advances in expanding analyte sensing and mechanisms of action with engineered RNA. Recent reviews have comprehensively covered the topics of aptamer selection via systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX)18 and mammalian post-transcriptional circuits19. Here, we examine novel strategies to create new ligand sensors and engineered RNAs that regulate diverse cellular processes. We conclude with a perspective on the maturation of the RNA device field and areas where we anticipate new technologies will drive further key advances.

Components of synthetic RNA devices

A major research focus in synthetic biology is the development of modular frameworks for constructing genetically encoded devices and engineered biological systems supported by the generation of well-characterized, biological component parts20. RNA devices are engineered RNA sequences that combine distinct sensor and actuator components to encode higher-order function than the components by themselves (FIG. 1b). In general, the sensor and actuator components are physically coupled such that binding of a ligand to the sensor component alters the activity of the actuator component5. The quantitative activity of the actuator component is therefore a read-out of the bound state of the sensor component and, ultimately, the concentration of the target ligand in the cellular environment.

Aptamers.

Nucleic acid sequences that can bind a particular ligand, such as a small molecule or protein.

RNA sensors can detect a range of biological inputs including nucleic acids, proteins and small molecules (FIG. 1b). RNA aptamers are a class of RNA sensors that bind molecular ligands via direct binding interactions. The quantitative activity of an RNA device is highly dependent on aptamer affinity and specificity. The ligand concentration range that a device is capable of reporting, its sensitivity (this is often reported as the EC50, the half maximal effective concentration), is closely coupled to the affinity of the incorporated aptamer. Cells contain many structurally similar molecules and aptamer specificity is critical to ensuring that the device reports on the desired molecular target. Starting from the analyte-sensing RNA sequences found in natural systems, researchers have worked to expand the number and diversity of molecular ligands that can be detected by RNA. Efforts have been split between mining genomes for new aptamers21 and generating de novo aptamers through high-throughput selection22,23. Both of these methods have faced limitations in generating new RNA aptamers, with RNA aptamers against approximately 100 small molecules and 400 proteins currently reported24–27.

RNA actuators are typically encoded by gene-regulatory or enzymatic components that control a process or event (FIG. 1b). In early examples, RNA devices inspired by natural riboswitches were used to control translation of gene expression in bacteria10. These RNA devices were located within the 5’ untranslated region of a target mRNA and modulated translation initiation of the encoded gene sequence by controlling ribosome binding site accessibility via alteration of RNA structure in that region10. Other early RNA devices modulated translation levels by controlling the degradation rate of the target mRNA with a self-cleaving ribozyme switch28. Additional designs have incorporated actuators that work through RNA interference-mediated silencing29, antisense-mediated silencing30 or transcription termination30. The majority of RNA devices described to date utilize actuators that control gene expression, and more generally have faced limitations in gene-regulatory dynamic range and ligand sensitivity31–34. Over the past decade, roles for RNA beyond control of translation through the central dogma have been better understood — including microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), spliceosome processing and CRISPR biology — providing opportunities to expand the mechanisms and systems through which RNA devices can act.

Ribozyme switch.

A type of riboswitch that uses a ribozyme, an RNA element that acts through cleaving RNA, to encode the actuation component.

Emerging applications of RNA devices

RNA devices enable advances in basic research.

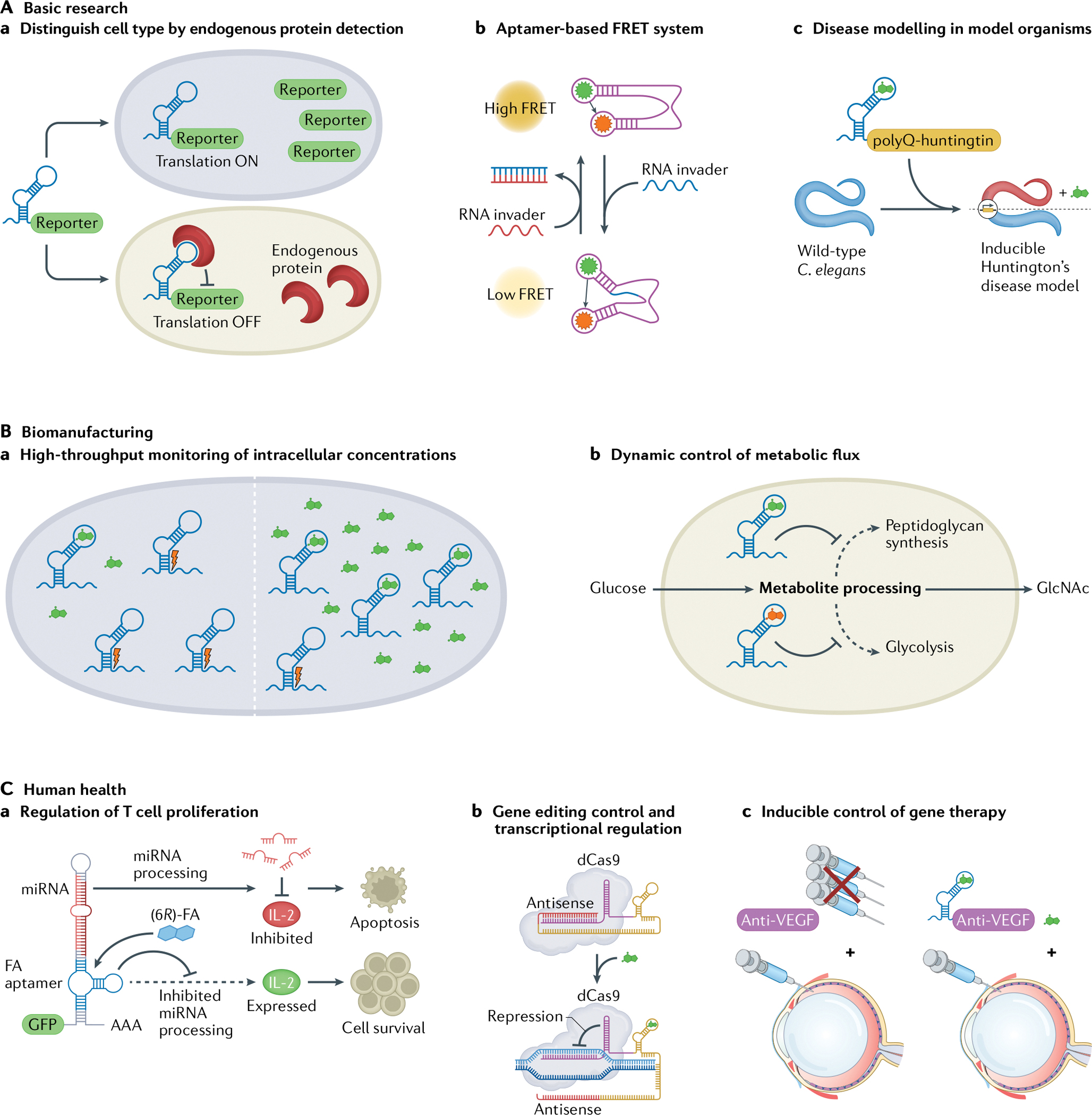

RNA devices have been applied as tools to address specific bottlenecks and propel basic research forward. One such bottleneck is the need to determine the cell state by detecting endogenous protein expression. Techniques to monitor protein levels such as western blotting, immunostaining and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry face difficulties in detecting proteins in living cells. RNA devices offer a promising solution by combining a protein-responsive RNA aptamer with a simple fluorescent read-out. One example of this approach is an mRNA device design that can distinguish between undifferentiated human induced pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells by quantifying endogenous LIN28A protein levels35 (FIG. 2Aa). This categorization method based on detecting key endogenous protein levels could pave the way for future strategies in live-cell detection or purification of specific cell types for regenerative medicine.

Fig. 2 |. RNA devices enable diverse applications.

Versatility of RNA highlighted in the wide application space of RNA devices ranging from addressing bottlenecks in basic research (part A), to providing advancements in biomanufacturing (part B) to propelling new frontiers in human health (part C). Aa | Detecting and quantifying endogenous LIN28A protein levels enables qualitative distinction between undifferentiated human induced pluripotent stem cells and differentiated cells35. Ab | RNA aptamers can be combined to create an aptamer-based Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) system for studying RNA folding inside living cells37. Ac | A tetracycline-dependent ribozyme switch controls polyQ-huntingtin expression and inclusion body formation in a novel inducible Caenorhabditis elegans polyglutamine Huntington’s disease model38. Ba | Cytoplasmic small-molecule concentrations can be monitored with ribozyme switches engineered to respond to specific metabolites39. Bb | Metabolite-responsive ribozyme switches integrated into cellular pathways enable reprogramming of networks for dynamic control of metabolic flux40. Ca | Insertion of a 6R-folinic acid (6R-FA)-responsive aptamer into microRNA (miRNA) switches enables regulation of T cell proliferation through control of miRNA processing44. Cb | CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) engineered with RNA aptamers that use a strand-displacement mechanism can lead to transcriptional regulation by ‘dead’ CRISPR–Cas9 (dCas9) (REF.45). Cc | A ribozyme switch can enable inducible control of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) proteins in a mouse model of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD)56. GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine.

RNA devices can also be used to study RNA folding inside living cells. Current techniques for studying in vivo RNA folding are lacking, but advances in the engineering of fluorescent RNA aptamers could potentially fill this need. Certain RNA aptamers can combine with specific small molecules to create a fluorescent complex. Researchers have improved upon early demonstrations in this space36, creating an RNA aptamer-based Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) system by placing fluorescent aptamers on RNA scaffolds37 (FIG. 2Ab). This apta-FRET system reports on RNA conformational changes and offers a general tool for studying the folding and conformational changes of natural and artificial RNA structures in vivo.

RNA devices also provide new ways to improve disease models. For instance, Caenorhabditis elegans can be used to study diseases such as Huntington’s disease, but suffers as a model system from a dearth of convenient methods for achieving conditional gene expression induction. Recent work described a tetracycline-dependent ribozyme switch that can confer inducible control when inserted into the 3′ untranslated region38 (FIG. 2Ac). This system was used to establish an inducible C. elegans polyglutamine Huntington’s disease model that exhibited ligand-controlled polyQ-huntingtin expression, inclusion body formation and toxicity. Although this inducible gene expression platform provides notable advantages over attempts to combine multiple components into the host genome, the dynamic range of the gene induction was limited compared with other methods used in C. elegans. Future efforts may leverage reported screening strategies to optimize switch activity that increase the dynamic range in a desired model system.

RNA devices detect and enhance metabolite production.

The ability to sense and monitor intracellular concentrations of metabolites is important for using biological systems to produce valuable small molecules at scale. Although existing technologies such as high-performance liquid chromatography, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry and others can be used to quantify concentrations of metabolites in biological samples, such analytical assays are of low throughput and only provide bulk assay measurements. An RNA device responsive to a specific metabolite offers a high-throughput, real-time and, potentially, single-cell alternative to current methods. In one example, in vitro selection was used to generate a series of engineered ribozyme switches that sense and respond to cyclic diguanosyl-5′-monophosphate (c-di-GMP)39 (FIG. 2Ba). The ribozyme switches were constructed by joining a self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme (HHRz) to an aptamer from a natural c-di-GMP riboswitch. These detectors quantitatively estimated cytoplasmic concentrations of c-di-GMP as low as 90 nM by assaying Escherichia coli lysate, thus demonstrating their use as convenient tools to monitor metabolite levels.

More recent work also showcases strategies that incorporate metabolite-responsive ribozyme switches into cellular systems for dynamic control of metabolic flux. In an effort to overproduce N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), metabolic networks in Bacillus subtilis were reprogrammed using a glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P)-responsive glmS ribozyme switch40 (FIG. 2Bb). By linking the GlcN6P-responsive ribozyme switches to the regulation of multiple target proteins involved in the peptidoglycan synthesis, glycolysis and GlcNAc synthesis pathways, researchers demonstrated an engineered cell system that doubled the total GlcNAc titre. GlcN6P is an essential metabolite with variable concentrations and although the system worked well at fairly high GlcN6P concentrations, the limited dynamic range of the glmS ribozyme switch meant that optimal GlcNAc synthesis was difficult to achieve at low GlcN6P levels. However, because the intermediate GlcN6P is involved in the biosynthesis of numerous products in addition to GlcNAc, with further optimization of the glmS ribozyme switch, this dynamic control strategy can enhance engineering of additional metabolic pathways for small-molecule production in B. subtilis and other industrial microbes.

Human health as the next frontier of RNA engineering.

Advances in RNA device engineering have propelled applications in human health. The incorporation of RNA devices offers distinct advantages in human health applications by facilitating therapeutic applications owing to their ability to encode multiple activities (including sense and respond functions) into a small genetic footprint for cellular delivery. The human immune response is a key area of interest for applying engineering biological tools to medicine. T cell immunotherapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T cell) therapies, seek to reprogramme patients’ immune cells to find and attack cancer cells. However, a primary issue with using CAR-T cells is the lack of ability to control cell behaviour and function in vivo after cell delivery. CAR-T cells can show powerful efficacy, but CAR-T cell-associated toxicities such as abnormally high cytokine production and massive in vivo T cell expansion have presented a major obstacle41. In response, the field has sought different ways to tailor individual treatments and develop safeguards against CAR-T cell-associated toxicities, including suicide switches to control cell death42. One early foray into genetic control of T cell proliferation used ribozyme switches to modulate expression levels of multiple cytokines, directing cells to either proliferate or undergo apoptosis43. Theophylline-mediated regulation of clonal T cell growth was demonstrated over 2 weeks in vivo along with effective control over primary human T cell proliferation. More recent work focused on the regulation of endogenous cytokine receptor subunits and developed synthetic miRNA-based RNA devices responsive to the biologically inert drug leucovorin ((6R)-folinic acid (6R-FA))44 (FIG. 2Ca). Combinatorial targeting of multiple receptor subunits with the incorporation of multiple miRNA switches responsive to (6R)-FA resulted in dynamic regulation of T cell growth, with up to 4-fold higher growth after addition of (6R)-FA and up to 26-fold diminished growth after removal of (6R)-FA. Taken together, these approaches offer a versatile strategy to address CAR-T cell-associated toxicities.

Applications requiring direct editing of the genome with CRISPR–Cas can also benefit from RNA devices. Leveraging the dependence of the CRISPR system on a guide RNA (gRNA), researchers designed a control system that incorporates small molecule-responsive aptamers into the 3′ region of the gRNA to modulate its structure45 (FIG. 2Cb). Initially, the spacer (which is complementary to the target sequence) is occluded. Ligand binding exposes the spacer sequence. The exposed sequence allows a catalytically inert ‘dead’ CRISPR–Cas9 (dCas9) to bind to the target sequence and silence the gene. More recent work demonstrated similar small molecule-responsive control of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) activity by incorporating similar RNA devices into CRISPR–Cpf1, showcasing the versatility of this strategy46. A separate example incorporated small molecule-responsive ribozyme switches into the 5′ region of the gRNA. Here, the spacer is occluded by a complementary strand. In contrast to the above structural rearrangement mechanism, the spacer is exposed, and the complex activated, when the complementary strand is cleaved by the cis-acting ribozyme in the presence of a ligand47.

Small molecule-responsive RNA controllers still face challenges related to the specificity and affinity of the incorporated aptamers. A more clinically advanced method for cell-specific control of translation via genome editing with a CRISPR effector has been demonstrated through the use of miRNA-controlled translation48–50. This system combined a CRISPR effector and an anti-CRISPR gene with miRNA response elements (MRE) in the 3′ untranslated region. The described system leveraged tissue-specific expression of miRNAs to direct repression of the anti-CRISPR proteins through the MREs and, thus, enable tissue-specific inhibition or activation of the CRISPR effector. The system was demonstrated in an in vivo mouse model, where MREs complementary to miR-122 (a liver-specific miRNA) directed gene editing to occur only in the liver, even with the RNA device delivered to all tissues via an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector51. These advances in incorporating RNA devices into CRISPR systems offer new strategies for temporal and conditional control of genome editing and transcriptional regulation that could lead to reductions in off-target effects52.

Clinical gene therapy is another health application space where the incorporation of RNA devices may improve clinical outcomes and safety. A primary method of gene therapy uses AAV vectors to deliver therapeutic genes to the patient. The small genetic size of RNA devices offers particular benefits for AAV vectors, which suffer from size constraints, only packaging ~4.7 kb53. Engineered ligand-responsive and miRNA-responsive RNA devices provide a compact control system, requiring just ~100 bp of plasmid space54. In one example, a guanine-responsive ribozyme switch was used to suppress transgene expression during AAV production and increase subsequent AAV vector yield up to 23-fold after addition of guanine54. Later work demonstrated the portability of the RNA device strategy by inserting the same guanine-responsive ribozyme switch to repress transgene expression from a replication-incompetent vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) vector by more than 26-fold in mammalian cells55. The use of small molecule-responsive RNA devices has also been demonstrated in a mouse model of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD)56 (FIG. 2Cc). Current treatments for wet AMD use repeated large-bolus injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents into the eye. Repetitive bolus dosing is associated with accelerated retinal degeneration, and there is a clear need to develop a long-term, single-use treatment for wet AMD that allows for tight temporal control of anti-VEGF agent expression. In this application, a tetracycline-responsive ribozyme switch delivered via a recombinant AAV vector enabled small molecule-controlled overexpression of an anti-VEGF protein and led to near complete inhibition of wet AMD disease lesions in mice56. More recent work showcased a tetracycline-responsive ribozyme switch also able to effectively control AAV-mediated transgene expression that demonstrated 15-fold induction, reversibility and multiorgan functionality — key clinical features that highlight the applicability of RNA devices for gene therapy57.

Finally, RNA devices have been applied to targeted cancer therapies using multiple methodologies that may overcome the clinical barriers of high cost, laborious techniques or safety concerns common to other treatments. One recently described approach takes advantage of a trans-splicing ribozyme to selectively inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma up to 86% through specific replacement of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) RNA in human TERT (hTERT)-positive liver cancers58. Adenovirus was used to deliver a trans-splicing ribozyme under the control of miR-122, a miRNA that is highly expressed in the liver, that specifically targeted, cleaved and then ligated the hTERT mRNA introducing a therapeutic gene RNA modification. This approach demonstrated that a cancer-specific RNA device could treat hepatocellular carcinoma by enabling a post-transcriptionally regulated RNA replacement strategy. In an alternative strategy, RNA aptamers were used to target and induce apoptosis in human NCI-H460 cells, a model of non-small cell lung cancer59. The RNA aptamers were capable of inhibiting NCI-H460 cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in the 100 nM range. Although there is potential immunogenicity from the AAV vector60, this method, once delivered, draws on the small size, specific binding and tissue-penetrative ability of RNA aptamer-based devices for targeted cancer therapy.

One concern for the use of RNA devices in human health applications is the natural immunogenicity of RNA61. The ubiquitous presence of RNA viruses has marked RNA and, especially, double-stranded RNA to be a particularly strong pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP), leading to rapid immune responses in humans through pathways such as RIG-I62,63. This immunogenicity has been shown to be reduced by replacement of uridines with N1-methylpseudouridine, RNA circularization and RNA designs that lack double-stranded regions64–68. Immunogenicity can be further mitigated by masking RNA PAMPs within lipid nanoparticles during delivery69. These advances in addressing RNA immunogenicity offer various strategies to streamline the translation of RNA devices to the clinic.

Cellular information sensing

The ability to design cell-control devices requires scalable strategies for developing genetically encoded aptamers with affinities and specificities that enable recognition of diverse cellular signals in the complex background of the cell environment. Although advances have also been made in the development of RNA molecules for sensing nucleic acid sequences, proteins and even non-biological stimuli, such as temperature and light70–73, we focus here on recent advances in strategies for the scalable generation of RNA aptamers for small-molecule sensing.

SELEX as a model for de novo generation of nucleic acid aptamers.

High-throughput selection techniques such as SELEX have been successful in scaling the number of aptamers that sense proteins, but selection for aptamers against small-molecule ligands has had limited success74. This discrepancy is largely due to the enrichment strategies used in conventional high-throughput selection approaches. A large nucleic acid library is mixed with the ligand(s) of interest, and the sequences that bind to the ligand are then separated from those that do not bind the ligand. Separation techniques generally utilize the size or mass difference between an aptamer and the aptamer–ligand complex to recover the ligand-binding sequences and favour methods that can be performed in high throughput (for example, membrane binding or capillary electrophoresis).

Although there is a large size difference between the aptamer and the aptamer–ligand complex when the ligand is a protein, this is not the case when the ligand is a small molecule. Methods developed to recover aptamer–small-molecule ligand complexes generally covalently link the small molecule, through a linker, to purification modalities such as magnetic beads, resins or a glass surface. Conjugating the small-molecule ligand to such linkers results in several challenges, including a lower-throughput process and enrichment of aptamers that bind to the conjugated molecule rather than the unconjugated molecule. The purification tags are normally conjugated onto reactive elements in the target molecule, removing functional groups that can interact with the aptamer22,75.

The critical properties of an RNA aptamer are its specificity (its ability to distinguish between molecules of similar structures) and affinity (how tightly it binds the ligand). High-specificity aptamers are often required for RNA devices used in cellular applications where many similarly structured molecules to the target ligand may be present. Such instances include discriminating between small molecules in a biosynthetic pathway or sensing specific molecules in a diagnostic setting. The required affinity of the aptamer incorporated in an RNA device will depend on the intended application and the anticipated concentration range of the ligand in the cell environment. Ultimately, the EC50 value of the RNA device, which is directly related to the affinity of the incorporated aptamer76, should be within the biologically relevant range of the target ligand. Both specificity and affinity can be tailored during the selection process for an aptamer. For example, negative or counterselection steps (that is, selecting against ligands of similar structures) can be incorporated to tune the specificity of an aptamer77. Similarly, affinity can be increased by lowering the ligand concentration as the selection progresses to place selective pressure for higher-affinity aptamers75,78,79. Finally, once an aptamer is generated, further tuning of specificity and affinity is possible through directed mutagenesis or rational engineering80–83. Despite advances in RNA aptamer selection and engineering, the total number of small molecules that can be sensed remains limited, and the imminent need for increased numbers of genetically encoded sensors requires an exponential expansion of our current throughput. Overcoming this barrier will require focused effort on improving enrichment efficiency of small-molecule aptamer selection, post-selection tuning of aptamer properties and computational modelling of RNA–ligand binding.

Capture-SELEX enhances selection for small-molecule ligands.

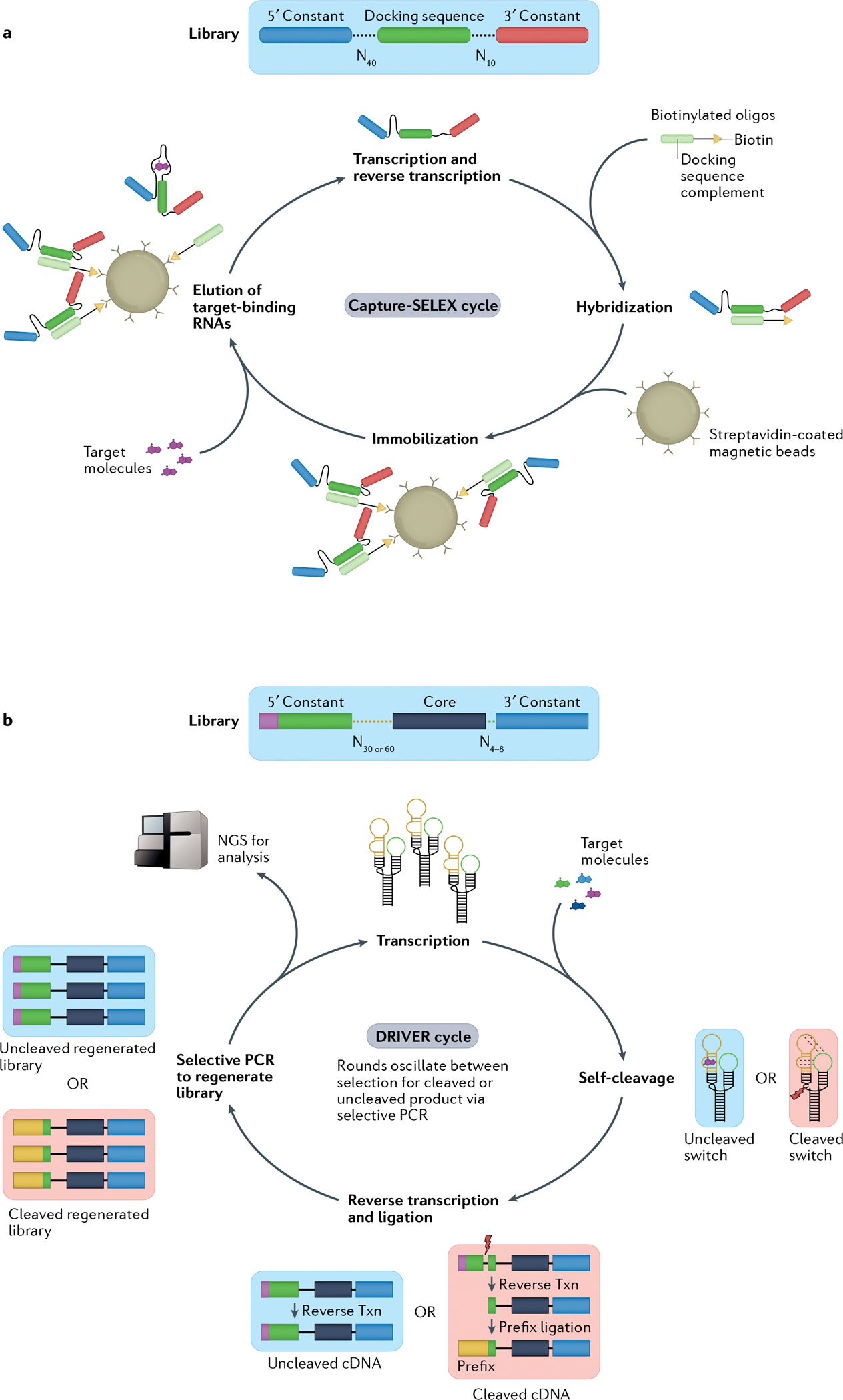

One recently described method, Capture-SELEX, utilizes structural changes between the ligand bound and unbound states of an RNA aptamer to enable a more efficient selection strategy for non-modified small-molecule ligands23,84 (FIG. 3a). This method immobilizes biotinylated oligonucleotides, called capture oligos, onto a streptavidin-covered magnetic bead. An RNA library consisting of 10 randomized nucleotides and 40 randomized nucleotides on either side of a capture sequence complementary to the capture oligos is transcribed and allowed to bind to the capture oligos. Small molecules of interest are added to the mixture and a small subset of the RNAs will bind to the ligands, disturbing the RNA-DNA interaction and causing the ligand-binding RNAs to be released from the beads. The released RNA is then recovered and separated from the remaining captured RNAs, reverse transcribed and sequenced, or put through further rounds of selection. After nine rounds of selection, Capture-SELEX generated RNA aptamers against adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in a mixture of multiple competing small molecules85. However, new aptamers created with Capture-SELEX are developed outside a biosensor context and must be subsequently incorporated into an RNA device framework for use in cellular control, which may require further modification and testing. Improvements in the method would allow direct selection of aptamers in their final RNA device context and scale up the development of new aptamers.

Fig. 3 |. Novel methods accelerate RNA sensor selection.

Overview of two methods for selection of RNA aptamers or sensors. Both methods begin with a diverse DNA library consisting of 1012–1015 distinct members. a | In the Capture-SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) method23,84,85, initial sequences consist of a 5′ and 3′ constant region flanking two randomized regions of 10 or 40 nucleotides with a constant docking sequence in the centre. The transcribed library is then hybridized to a biotinylated oligonucleotide via base pairing of the docking sequence. The complexes are immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and mixed with the target molecules. RNA sequences that bind the target molecules and undock from the biotinylated oligonucleotides are subsequently eluted from the beads, creating the starting library for the next selection cycle. b | In the DRIVER (de novo rapid in vitro evolution of RNA biosensors) method81, libraries are designed based on a modified hammerhead ribozyme (HHRz) from satellite RNA of tobacco ringspot virus (sTRSV) — a small, naturally occurring self-cleaving ribozyme — with the two loops replaced by either a randomized 30–60mer or a randomized 4–8mer. Sequences are mixed with target molecules. Desired RNA biosensor sequences cleave in the absence of the target molecule but bind to the target molecule when present, preventing cleavage. In iterative cycles of negative and positive selection, the RNA sequences are reverse transcribed (txn) and the resultant cDNA of cleaved sequences has a 5′ primer ligated that allows for selective PCR amplification of the sequences corresponding to either the cleaved or uncleaved RNA. The amplified DNA library then serves as the starting library for a new round of DRIVER. Periodically, these libraries can be analysed following quantification by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Part a reprinted with permission from REF85, Elsevier.

DRIVER utilizes ribozyme cleavage to automate selection strategy.

A second recently described method, DRIVER (de novo rapid in vitro evolution of RNA biosensors), relies on sequence changes between the ligand bound and unbound states of an aptamer-coupled ribozyme device to enable an entirely in-solution selection strategy that can be executed autonomously on a liquid handling robot81 (FIG. 3b). DRIVER utilizes a device framework that couples an aptamer to a ribozyme, in which binding of the ligand to the aptamer controls the ribozyme’s self-cleavage activity. A library is created that contains two randomized regions, a shorter sequence of up to 8 random nucleotides and a longer sequence of up to 60 random nucleotides, on loops I and II of the HHRz. These libraries are transcribed in the presence or absence of a small-molecule ligand mixture. A given HHRz molecule will either remain intact or undergo self-cleavage depending on its folded structure and ligand-bound state. A novel splint oligonucleotide is used to specifically recover and amplify cleaved sequences from the reaction mixture, whereas a standard primer is used to recover uncleaved sequences. The reaction is then run over multiple cycles with or without ligand present. In the absence of ligand, only cleaved sequences are recovered and in the presence of ligand, only uncleaved sequences are recovered. The alternating cycles allow for selection of ligand-responsive ribozyme switches.

In the original demonstration of the DRIVER method, small molecule-responsive RNA biosensors with nanomolar and micromolar affinities were generated against six small molecules, five of which had no previously reported aptamers81. Aptamers created via DRIVER can be used in the HHRz framework directly as genetic controllers or can be isolated and used separately. However, isolation of functional switches via DRIVER can require more than 100 rounds of selection owing to low enrichment efficiencies caused by the persistence of sequences that naively fold into cleaving and non-cleaving conformations independent of ligand concentration86. DRIVER makes such intensive selection viable by automating the process on a liquid handling robot system so that an entire selection experiment against multiple ligands in parallel can be performed in a high-throughput manner. Although DRIVER exhibits robust ability for novel sensor generation, some limitations require consideration in its broad application. Because bulk selection conditions in DRIVER are not optimized to generate switches responsive to specific ligands, some DRIVER-derived sensors may require further optimization post selection. The DRIVER method also only generated ribozyme switches responsive to a small subset of all tested ligands. It is unknown whether this is a limitation of the types of ligands that RNA can sense or a limitation of the pooled, multiplexed process in which the DRIVER selections were performed. Future work should focus on scaling the throughput of DRIVER and demonstrating the utility of DRIVER-selected switches in diverse applications.

Sequencing methods enable high-throughput optimization of existing aptamers.

High-throughput methods have recently been described with streamlined workflows for generating RNA devices from existing aptamers. The aptamer sequences are generally integrated into an RNA device framework and then regions of the device are randomized. As the aptamer sequence already exists, the library sizes can be drastically reduced from those used in methods such as Capture-SELEX and DRIVER. The smaller starting library sizes allow researchers to collect activity data for all library members, as well as run selection and functional assays in the cell systems that the RNA devices will ultimately be used in87–91. For example, fluorescence-activated cell sorting followed by sequencing (FACS–seq) and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) approaches were recently used to screen RNA device libraries based on existing small-molecule aptamers to identify sequences that result in gene expression control in human cells87. As these approaches can suffer from time-intensive and cost-intensive steps, efforts have also focused on developing a high-throughput method for the identification of synthetic RNA devices based on existing aptamers by barcode-free amplicon sequencing88. This method was applied to screening RNA device libraries based on existing tetracycline and guanine aptamers and leveraging ribozyme cleavage (that is, HHRz, hepatitis delta virus and Twister ribozymes) and U1-snRNP polyadenylation mechanisms in human cells. Taken together, these methods also showcase the modularity possible with RNA parts — aptamers generated in one context can be incorporated across diverse device platforms.

RNA processing and cell control

RNA devices are integrated into cellular regulatory networks from which they can control and probe biological processes. Here, we highlight recent advances in engineered RNAs acting as actuators. These novel RNA regulatory strategies provide opportunities for researchers to expand the mechanisms through which RNA devices can act.

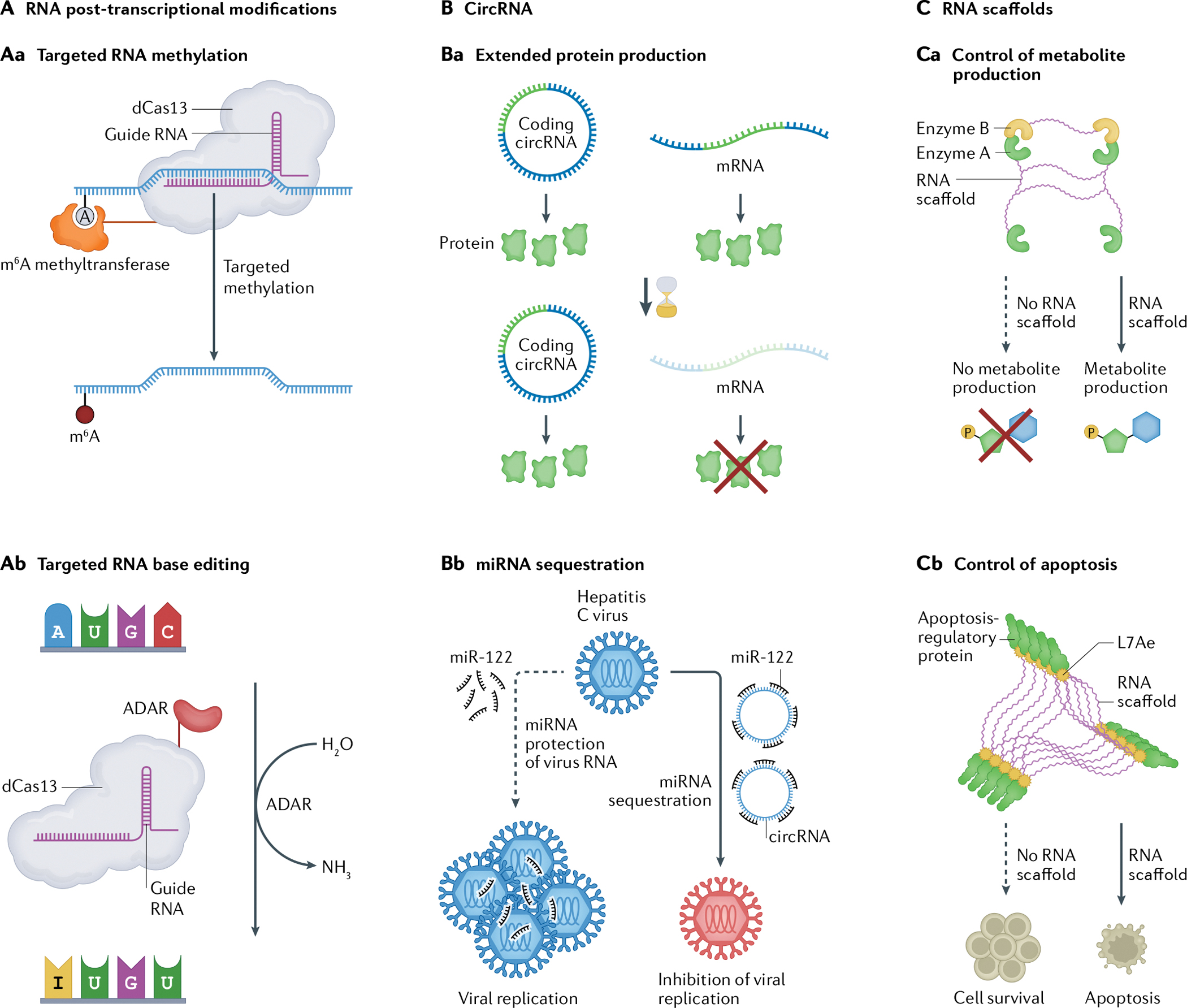

RNA base modifications enable tuning of translation.

One of the more nuanced forms of RNA regulation is based on post-transcriptional modification of bases in RNA92. Sequencing of tRNAs revealed the first discovered RNA modifications to be pseudouridine (ψ) and N-methylation of nucleotides that have been shown to increase processivity of the ribosome and lower the translational error frequency93,94. Newer sequencing techniques, such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A) sequencing (m6A-seq)95 and methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP–seq)96, have allowed the mapping of the role of RNA post-transcriptional modification in biological processes. Using these techniques, m6A has been revealed as vital to gene control and linked to cancer92,97. m6A modifications affect mRNA stability and translation through a set of methyltransferases, demethylases and proteins that can read out m6A modifications — so-called writers, erasers and readers98. RNA actuators have been constructed that can add and remove m6A modifications from a target RNA by fusing methyltransferases to a catalytically inactive CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas13 (REF99) (FIG. 4Aa). Leveraging Cas13, which can selectively target RNA complementary to its loaded gRNA, the fused methyltransferase catalyses the conversion of specific adenosines to m6A. This work showed that the translation of mRNAs with known m6A sensitivity could be tuned via these targeted modifications. Further studies are required to fully understand how m6A modifications affect RNA stability and translation in cells, and whether this approach can be expanded to the broader cellular suite of readers, writers and erasers. Additionally, future work can explore whether this type of artificial methylation can be used to programme other processes such as alternative splicing100.

Fig. 4 |. Emerging mechanisms of RNA processing and cell control for novel RNA devices.

Recent findings have revealed new roles and mechanisms for RNA beyond control of translation through the central dogma, including targeted RNA base editing and post-transcriptional modifications (part A), circular RNA (circRNA) mechanisms (part B) and novel uses of RNA scaffolds (part C). Future RNA devices can incorporate these new mechanisms. Aa | Post-transcriptional modifications are involved in RNA regulation. N6-Methy[adenosine (m6A) is a post-transcriptional modification affecting mRNA stability and translation. Methyltransferases can be fused to dCas13 (a catalytically inactive CRISPR-associated nuclease) directed by a guide RNA to catalyse the conversion of adenosines to m6A, allowing targeted artificial methylation of RNA which could be further utilized99. Ab | RNA base editors use naturally occurring and evolved enzymes to modify RNA nucleobases for post-transcriptional gene editing. Current editors utilize deaminases to convert adenosine and cytosine to inosine and uracil, respectively103,104,106,152. Ba | circRNA expression vectors express proteins for longer than equivalent mRNA sequences107. Bb | Synthetic circRNAs can be designed as microRNA (miRNA) sponges to quench specific miRNAs and inhibit miRNA-dependent viral replication120. Ca | RNA can be repurposed as a scaffold to co-localize enzymes and increase local enzyme concentrations for control of metabolite production125. Cb | RNA scaffolds can also be constructed to induce proximity oligomerization of Caspase 8 within the caspase pathway for apoptosis126. ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA. Part Aa is adapted from REF99, Springer Nature Limited. Part Cb is adapted from REF126, CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Advances in RNA-targeting proteins have led to a renaissance in RNA base editing for scientific and therapeutic uses101,102. Although much of the attention of genome engineering is focused on editing DNA, RNA editing may allow for non-permanent gene therapy techniques and targeting of conditions that can only be altered post-transcriptionally. These actuation mechanisms function by linking an RNA-targeting complex, such as CRISPR–Cas13, CRISPR–Cas9 or endogenous human RNA-binding proteins to an enzyme capable of modifying an RNA base, such as adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) domains103–105 (FIG. 4Ab). The RNA-targeting domain brings the deaminase enzyme in proximity with an adenosine, thus deaminating the adenosine into an inosine. Recent work has expanded the toolbox to allow for the editing of cytosines to uridines106. Future work may focus on developing additional editing domains to allow for all RNA bases to be modified to every possible other base, as well as the incorporation of this regulatory mechanism into RNA device frameworks for conditional control of editing functions.

Circular RNAs as temporally stable translation platforms and molecular sponges.

Another area of RNA regulation where our understanding of the underlying biological processes has recently advanced is circRNA107. circRNAs are RNA molecules that take the form of a covalently closed loop due to post-transcriptional processing108 (FIG. 1a) and have been shown to play a pathological role in numerous diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer disease and cardiovascular disease109–111. There is also evidence that circRNAs can encode proteins and regulate translation by serving as sponges for miRNAs and RNA-binding proteins112–114.

Methods for synthesizing engineered circRNA devices in cells have been described that use various mechanisms, including ribozyme cleavage and tRNA ligation, group I self-splicing introns and back-splicing115–117. Each of these methods was demonstrated to create synthetic circRNAs that can be translated to proteins in cells. It was hypothesized that circRNAs can persist longer in cells than mRNAs as they lack ends accessible to exonuclease activity; this increased stability was demonstrated by showing that luciferase activities from a circRNA and an mRNA were comparable, whereas the circRNA exhibited a protein production half-life (that is, time for luciferase activity to decrease by 50%) of 80 h compared with 45 h for the comparable mRNA116 (FIG. 4Ba). The persistence of circRNAs has been leveraged as a platform for the expression of RNA devices. Ribozyme-assisted circular RNAs (racRNAs) are a class of RNA devices that can be expressed in cells at high concentrations, increasing device concentrations from the low nanomolar to micromolar range115. The platform places the RNA sequence of interest between two ribozymes, where, once cleaved, the ends of the RNA are circularized by ligation through the endogenous RNA ligase RtcB. This platform was used to develop RNA devices that detect intracellular SAM concentrations and inhibit the cell-signalling protein NF-κB118.

circRNAs can also be engineered to act as non-natural miRNA sponges119. One recent study reported the engineering of a synthetic circRNA with multiple binding sites for miR-122 to act as a miR-122 sponge120 (FIG. 4Bb). miR-122 protects the 5’ end of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) genome from degradation and enhances viral replication and translation. The engineered circRNAs were transcribed and circularized in vitro, and subsequently transfected into human hepatoma cell lines Huh-7 and Huh-7.5, where they sequestered miR-122 and resulted in lower HCV infection120,121. circRNAs have also been developed as sponges for proteins122. Researchers engineered and integrated a construct that would become a circRNA with 100 CA dinucleotides when transcribed in HEK293 cells. These CA repeats are a known binding site for heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear protein L (hnRNPL), a regulator of alternative splicing. When the circRNA was expressed, a shift in alternative splicing was observed across the genome. These early studies show that circRNAs can be used for long-lasting protein production in mammalian cells and function as sponges for other RNAs and RNA-binding proteins.

Despite these recent advances, circRNAs remain underexplored in the field largely due to the difficulty in detecting and measuring the concentration of circRNAs distinct from their cognate linear isoforms123. As a result, we still do not fully understand the cellular role circRNAs play and, thus, what unintentional effects overexpression of engineered circRNAs may have on cells. Advances in methods to detect and quantify circRNAs in cells are critical to supporting the development of this RNA platform into a broader engineering tool for the field.

RNA scaffolds serve as modular substrate for programming spatial organization.

Beyond these examples of incorporating new RNA biology, scientists have utilized RNA to achieve genetically encodable, biological elements that do not have known RNA counterparts in nature. One way RNA can be repurposed is as a scaffold for various cellular processes124. For instance, RNA scaffolds have been engineered into cells to co-localize enzymes in a biosynthetic pathway, increasing the local concentration of the metabolites and enzymes, and thus the rate at which reactants can be converted into pathway products. In one example, researchers working with E. coli designed a set of RNA sequences encoding aptamers in a 2D scaffold and then co-expressed four enzymes involved in succinate production that were fused to the corresponding aptamer-binding protein domains125 (FIG. 4Ca). The RNA-scaffolded pathway exhibited an 88% increase in succinate production when compared with a control strain.

In another example, scientists replaced a protein-based scaffold in the caspase pathway for apoptosis with an RNA-based scaffold126 (FIG. 4Cb). Caspase 8 normally requires a protein scaffold for proximity oligomerization to occur, which triggers the cell-death cascade. Researchers fused Caspase 8 to L7Ae, an RNA-binding protein, and designed an RNA scaffold harbouring L7Ae binding sequences. When the fusion protein and RNA scaffold were present in cells, the caspase pathway was triggered, leading to programmed apoptosis. The authors built a targeted RNA device that induced expression of the L7Ae–Caspase 8 fusion upon binding of specific miRNAs, resulting in cell death. The resulting RNA device enabled selective control of cell death in HeLa cells, achieving apoptosis rates more than double those of background levels (up to 70%) with the full L7Ae–Caspase 8 device.

Strategies using engineered RNA as a platform to assemble and organize molecules inside cells are currently limited in the size and diversity of known scaffolds. Development of future RNA scaffolds may require the design of basic RNA building blocks that could be combined in a modular fashion to form diverse and programmable structures that can control orientation and organization inside cells. Diverse RNA elements could ultimately be integrated throughout the resulting scaffold to achieve dynamic control over spatial organization via conformational changes.

Conclusions and perspective

RNA science has flourished in the last decade. Two mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were designed, manufactured and distributed to hundreds of millions of people in the span of 18 months127–129. This achievement has highlighted the promise of engineered RNA and has led to substantial public and private-sector investments in both basic and applied research and development130–133. Fulfilling the potential of this field will require partnerships between basic and applied researchers, organizations, commercial entities and funding bodies.

RNA engineering has lagged behind protein engineering, despite RNA’s simpler component parts and robust secondary-structure modelling. However, recent progress in RNA engineering tool development provides optimism as similar advances accelerated the field of protein engineering. The goal of RNA device engineering must be to, at the very least, match nature’s level of proficiency with RNA polymers. To achieve this, the field should take inspiration from the development of the protein design field. Protein engineers have access to large, well-annotated, public libraries of protein data. These shared resources have allowed for the development of powerful computational tools for de novo protein design134–137. Building out similar shared resources for RNA will require coordination within the field. The utility of medium-throughput RNA structural determination has been spurred on by recent advances in cryogenic electron microscopy, nuclear magnetic resonance and chemical mapping, as well as the application of new statistical techniques for RNA tertiary structure prediction138–142. Partnerships that focus on the further development, application and scaling of these tools should be incentivized.

Inspired by coordinated efforts in the protein and enzymology fields, RNA foundries should be established to focus on scaling high-throughput methods to generate open-source libraries of standard, well-characterized RNA components that can be used widely by the field in support of new device generation23,81,88. Scaling such efforts will ensure a critical open resource to advance the broader adoption of RNA devices in research, commercial and clinical settings. Larger consortiums should be established to focus on tool development to advance RNA biology and engineering, including work to improve in vitro transcription, RNA quantification, in vitro and in vivo RNA modifications, targeting of RNA by small-molecule drugs and the delivery and immunogenicity of RNA therapeutics69,123,143–146. As momentum in the field continues to grow, engineered RNA devices will fulfil their potential as precision engineered systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Payne, P. Srinivasan and B. Townshend for valuable feedback in the preparation of this Review. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant to C.D.S.), National Science Foundation (NSF) (graduate fellowships to P.B.D. and M.K.) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) (Gilliam graduate fellowship to M.K.). C.D.S. is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub investigator.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Genetics thanks James M. Carothers, James J. Collins and Hirohide Saito for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Nshogozabahizi JC, Aubrey KL, Ross JA & Thakor N Applications and limitations of regulatory RNA elements in synthetic biology and biotechnology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 127, 968–984 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J & Franco E RNA nanotechnology in synthetic biology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 63, 135–141 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt CM & Smolke CD RNA switches for synthetic biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 11, 135–141 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SV et al. Catalytic RNA, ribozyme, and its applications in synthetic biology. Biotechnol. Adv. 37, 107452 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Win MN, Liang JC & Smolke CD Frameworks for programming biological function through RNA parts and devices. Chem. Biol. 16, 298–310 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang JC, Bloom RJ & Smolke CD Engineering biological systems with synthetic RNA molecules. Mol. Cell 43, 915–926 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahvi A et al. Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem. Biol. 9, 1043–1049 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S & Breaker RR An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15908–15913 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudarsan N, Barrick JE & Breaker RR Metabolite-binding RNA domains are present in the genes of eukaryotes. RNA 9, 644–647 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacs FJ et al. Engineered riboregulators enable post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 841–847 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suess B & Weigand JE Engineered riboswitches: overview, problems and trends. RNA Biol. 5, 24–29 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKeague M, Wong RS & Smolke CD Opportunities in the design and application of RNA for gene expression control. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 2987–2999 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westbrook AM & Lucks JB Achieving large dynamic range control of gene expression with a compact RNA transcription–translation regulator. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 5614–5624 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J et al. De novo-designed translation-repressing riboregulators for multi-input cellular logic. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 1173–1182 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauch S, Jones KA & Dickinson BC Small molecule-inducible RNA-targeting systems for temporal control of RNA regulation. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1987–1996 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chappell J, Westbrook A, Verosloff M & Lucks JB Computational design of small transcription activating RNAs for versatile and dynamic gene regulation. Nat. Commun. 8, 1051 [2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anzalone AV, Lin AJ, Zairis S, Rabadan R & Cornish VW Reprogramming eukaryotic translation with ligand-responsive synthetic RNA switches. Nat. Methods 13, 453–458 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sporing M, Finke M & Hartig JS Aptamers in RNA-based switches of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 63, 34–40 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki S, Ono H, Hirosawa M & Saito H RNA and protein-based nanodevices for mammalian post-transcriptional circuits. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 63, 99–110 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endy D Foundations for engineering biology. Nature 438, 449–453 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrick JE & Breaker RR The distributions, mechanisms, and structures of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Genome Biol. 8, R239 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellington AD & Szostak JW In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauridsen LH, Doessing HB, Long KS & Nielsen AT in Synthetic Metabolic Pathways: Methods and Protocols (eds. Jensen MK & Keasling JD) 291–306 (Springer, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird GS Where are all the aptamers? Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 134, 529–531 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn MR, Jimenez RM & Chaput JC Analysis of aptamer discovery and technology. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1,0076 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKeague M & DeRosa MC Challenges and opportunities for small molecule aptamer development. J. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1–20 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKeague M et al. Analysis of in vitro aptamer selection parameters. J. Mol. Evol. 81, 150–161 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu J, Hannon GJ & Parker R Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes Dev. 20, 515–524 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom RJ, Winkler SM & Smolke CD Synthetic feedback control using an RNAi-based gene-regulatory device. J. Biol. Eng. 9, 5 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucks JB, Qi L, Mutalik VK, Wang D & Arkin AP Versatile RNA-sensing transcriptional regulators for engineering genetic networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8617–8622 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Auslander S & Fussenegger M Synthetic RNA-based switches for mammalian gene expression control. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 48, 54–60 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chappell J et al. The centrality of RNA for engineering gene expression. Biotechnol. J. 8, 1379–1395 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Till P, Toepel J, BUhler B, Mach RL & Mach-Aigner AR Regulatory systems for gene expression control in cyanobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 1977–1991 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayer TS & Smolke CD Programmable ligand-controlled riboregulators of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 337–343 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawasaki S, Fujita Y, Nagaike T, Tomita K & Saito H Synthetic mRNA devices that detect endogenous proteins and distinguish mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e117–e117 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paige JS, Nguyen-Duc T, Song W & Jaffrey SR Fluorescence imaging of cellular metabolites with RNA. Science 335, 1194–1194 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jepsen MDE et al. Development of a genetically encodable FRET system using fluorescent RNA aptamers. Nat. Commun. 9, 18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurmthaler LA, Sack M, Gense K, Hartig JS & Gamerdinger M A tetracycline-dependent ribozyme switch allows conditional induction of gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 10, 491 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu H, Furukawa K & Breaker RR Engineered allosteric ribozymes that sense the bacterial second messenger cyclic diguanosyl 5′-monophosphate. Anal. Chem. 84, 4935–4941 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niu T et al. Engineering a glucosamine-6-phosphate responsive glmS ribozyme switch enables dynamic control of metabolic flux in Bacillus subtilis for overproduction of N-acetylglucosamine. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 2423–2435 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sterner RC & Sterner RM CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 11, 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Stasi A et al. Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1673–1683 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YY, Jensen MC & Smolke CD Genetic control of mammalian T-cell proliferation with synthetic RNA regulatory systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8531–8536 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong RS, Chen YY & Smolke CD Regulation of T cell proliferation with drug-responsive microRNA switches. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1541–1552 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y et al. Directing cellular information flow via CRISPR signal conductors. Nat. Methods 13, 938–944 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y et al. Engineering cell signaling using tunable CRISPR-Cpf1-based transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 8, 2095 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang W, Hu JH & Liu DR Aptazyme-embedded guide RNAs enable ligand-responsive genome editing and transcriptional activation. Nat. Commun. 8, 15939 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann MD et al. Cell-specific CRISPR–Cas9 activation by microRNA-dependent expression of anti-CRISPR proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e75 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirosawa M et al. Cell-type-specific genome editing with a microRNA-responsive CRISPR–Cas9 switch. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, e118 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirosawa M, Fujita Y & Saito H Cell-type-specific CRISPR activation with microRNA-responsive AcrllA4 switch. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1575–1582 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee J et al. Tissue-restricted genome editing in vivo specified by microRNA-repressible anti-CRISPR proteins. RNA 25, 1421–1431 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis KM, Pattanayak V, Thompson DB, Zuris JA & Liu DR Small molecule-triggered Cas9 protein with improved genome-editing specificity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 316–318 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins PD, Tahara H & Ghivizzani SC Viral vectors for gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 16, 35–40 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strobel B et al. Riboswitch-mediated attenuation of transgene cytotoxicity increases adeno-associated virus vector yields in HEK-293 cells. Mol. Ther. 23, 1582–1591 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi K & Yokobayashi Y Reversible gene regulation in mammalian cells using riboswitch-engineered vesicular stomatitis virus vector. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 1976–1982 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reid CA, Nettesheim ER, Connor TB & Lipinski DM Development of an inducible anti-VEGF rAAV gene therapy strategy for the treatment of wet AMD. Sci. Rep. 8, 11763 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strobel B et al. A small-molecule-responsive riboswitch enables conditional induction of viral vector-mediated gene expression in mice. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 1292–1305 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han SR et al. Targeted suicide gene therapy for liver cancer based on ribozyme-mediated RNA replacement through post-transcriptional regulation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 23, 154–168 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H et al. Characterization of a bifunctional synthetic RNA aptamer and a truncated form for ability to inhibit growth of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 9, 18836 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Worgall S, Wolff G, Falck-Pedersen E & Crystal RG Innate immune mechanisms dominate elimination of adenoviral vectors following in vivo administration. Hum. Gene Ther. 8, 37–44 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uehata T & Takeuchi O RNA recognition and immunity-innate immune sensing and its posttranscriptional regulation mechanisms. Cells 9, E1701 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ireton RC, Wilkins C & Gale M RNA PAMPs as molecular tools for evaluating RIG-I function in innate immunity. Methods Mol. Biol. 1656, 119–129 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kell AM & Gale M RIG-I in RNA virus recognition. Virology 479–480, 110–121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu MZ, Asahara H, Tzertzinis G & Roy B Synthesis of low immunogenicity RNA with high-temperature in vitro transcription. RNA 26, 345–360 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andries O et al. N1-Methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J. Control. Rel. 217, 337–344 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kariko K et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol. Ther. 16, 1833–1840 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wesselhoeft RA et al. RNA circularization diminishes immunogenicity and can extend translation duration in vivo. Mol. Cell 74, 508–520.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pardi N, Hogan MJ & Weissman D Recent advances in mRNA vaccine technology. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 65, 14–20 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wadhwa A, Aljabbari A, Lokras A, Foged C & Thakur A Opportunities and challenges in the delivery of mRNA-based vaccines. Pharmaceutics 12, E102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dua P, Kim S & Lee D Nucleic acid aptamers targeting cell-surface proteins. Methods 54, 215–225 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Narberhaus F, Waldminghaus T & Chowdhury S RNA thermometers. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 3–16 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neupert J, Karcher D & Bock R Design of simple synthetic RNA thermometers for temperature-controlled gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e124–e124 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lotz TS et al. A light-responsive RNA aptamer for an azobenzene derivative. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 2029–2040 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gold L et al. Aptamer-based multiplexed proteomic technology for biomarker discovery. PLoS ONE 5, e15004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Darmostuk M, Rimpelova S, Gbelcova H & Ruml T Current approaches in SELEX: an update to aptamer selection technology. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 1141–1161 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wayment-Steele H, Wu M, Gotrik M & Das R in Methods in Enzymology Vol. 623 Ch. 18 (ed. Hargrove AE) 417–450 (Academic, 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davis JH & Szostak JW Isolation of high-affinity GTP aptamers from partially structured RNA libraries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11616–11621 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kohlberger M & Gadermaier G SELEX: critical factors and optimization strategies for successful aptamer selection. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 10.1002/bab.2244 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Komarova N & Kuznetsov A Inside the black box: what makes SELEX better? Molecules 24, E3598 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ricci F, Vallée-Bélisle A, Simon AJ, Porchetta A & Plaxco KW Using nature’s “tricks” to rationally tune the binding properties of biomolecular receptors. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1884–1892 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Townshend B, Xiang JS, Manzanarez G, Hayden EJ & Smolke CD A multiplexed, automated evolution pipeline enables scalable discovery and characterization of biosensors. Nat. Commun. 12, 1437 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hasegawa H, Savory N, Abe K & Ikebukuro K Methods for improving aptamer binding affinity. Molecules 21,421 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kalra P, Dhiman A, Cho WC, Bruno JG & Sharma TK Simple methods and rational design for enhancing aptamer sensitivity and specificity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 5, 41 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stoltenburg R, Nikolaus N & Strehlitz B Capture-SELEX: selection of DNA aptamers for aminoglycoside antibiotics. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2012, 1–14 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boussebayle A, Groher F & Suess B RNA-based Capture-SELEX for the selection of small molecule-binding aptamers. Methods 161, 10–15 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koizumi M, Soukup GA, Kerr JN & Breaker RR Allosteric selection of ribozymes that respond to the second messengers cGMP and cAMP. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1062–1071 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xiang JS et al. Massively parallel RNA device engineering in mammalian cells with RNA-seq. Nat. Commun. 10, 4327 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Strobel B et al. High-throughput identification of synthetic riboswitches by barcode-free amplicon-sequencing in human cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Townshend B, Kennedy AB, Xiang JS & Smolke CD High-throughput cellular RNA device engineering. Nat. Methods 12, 989–994 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nomura Y, Chien H-C & Yokobayashi Y Direct screening for ribozyme activity in mammalian cells. Chem. Commun. 53, 12540–12543 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gotrik M et al. Direct selection of fluorescence-enhancing RNA aptamers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3583–3591 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao BS, Roundtree IA & He C Posttranscriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 31–42 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Holley RW, Everett GA, Madison JT & Zamir A Nucleotide sequences in the yeast alanine transfer ribonucleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 240, 2122–2128 (1965). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pereira M et al. Impact of tRNA modifications and tRNA-modifying enzymes on proteostasis and human disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, E3738 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dominissini D et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Meyer KD et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jaffrey SR & Kharas MG Emerging links between m6A and misregulated mRNA methylation in cancer. Genome Med. 9, 2 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu J et al. A METTL3–METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 93–95 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilson C, Chen PJ, Miao Z & Liu DR Programmable m6A modification of cellular RNAs with a Cas13-directed methyltransferase. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1431–1440 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xiao W et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 61,507–519 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rees HA & Liu DR Base editing: precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 770–788 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marina RJ, Brannan KW, Dong KD, Yee BA & Yeo GW Evaluation of engineered CRISPR-cas-mediated systems for site-specific RNA editing. Cell Rep. 33, 108350 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qu L et al. Programmable RNA editing by recruiting endogenous ADAR using engineered RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1059–1069 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cox DBT et al. RNA editing with CRISPR–Cas13. Science 358, 1019–1027 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rauch S et al. Programmable RNA-guided RNA effector proteins built from human parts. Cell 178, 122–134.e12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Abudayyeh OO et al. A cytosine deaminase for programmable single-base RNA editing. Science 365, 382–386 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salzman J Circular RNA expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends Genet. 32, 309–316 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lasda E & Parker R Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA 20, 1829–1842 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Akhter R Circular RNA and Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1087, 239–243 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Altesha M-A, Ni T, Khan A, Liu K & Zheng X Circular RNA in cardiovascular disease. J. Cell Physiol. 234, 5588–5600 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Han B, Chao J & Yao H Circular RNA and its mechanisms in disease: from the bench to the clinic. Pharmacol. Ther. 187, 31–44 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Prats A-C et al. Circular RNA, the key for translation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8591 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Legnini I et al. Circ-ZNF609 is a circular RNA that can be translated and functions in myogenesis. Mol. Cell 66, 22–37.e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pamudurti NR et al. Translation of circRNAs. Mol. Cell 66, 9–21.e7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Litke JL & Jaffrey SR Highly efficient expression of circular RNA aptamers in cells using autocatalytic transcripts. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 667–675 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wesselhoeft RA, Kowalski PS & Anderson DG Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 2629 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meganck RM et al. Engineering highly efficient backsplicing and translation of synthetic circRNAs. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 23, 821–834 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paige JS, Wu KY & Jaffrey SR RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Science 333, 642–646 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rossbach O Artificial circular RNA sponges targeting microRNAs as a novel tool in molecular biology. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 17, 452–454 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jost I et al. Functional sequestration of microRNA-122 from hepatitis C virus by circular RNA sponges. RNA Biol. 15, 1032–1039 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Blight KJ, McKeating JA & Rice CM Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 76, 13001–13014 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schreiner S, Didio A, Hung L-H & Bindereif A Design and application of circular RNAs with protein-sponge function. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 12326–12335 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Li X, Yang L & Chen L-L The biogenesis, functions, and challenges of circular RNAs. Mol. Cell 71, 428–442 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Delebecque CJ, Lindner AB, Silver PA & Aldaye FA Organization of intracellular reactions with rationally designed RNA assemblies. Science 333, 470–474 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sachdeva G, Garg A, Godding D, Way JC & Silver PA In vivo co-localization of enzymes on RNA scaffolds increases metabolic production in a geometrically dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 9493–9503 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shibata T et al. Protein-driven RNA nanostructured devices that function in vitro and control mammalian cell fate. Nat. Commun. 8, 540 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.WHO. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard with vaccination data. World Health Organization; https://covid19.who.int/info(2020). [Google Scholar]

- 128.Polack F P. et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Corbett KS et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Slaoui M & Hepburn M Developing safe and effective covid vaccines — Operation Warp Speed’s strategy and approach. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1701–1703 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bell J Moderna founder’s next big play in RNA raises $440M. BioPharma Dive https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/laronde-endless-rna-series-b-flagship-moderna/605740/(2021).

- 132.Bell J Venture capital pours more money into RNA medicines with the launch of Replicate. BioPharma Dive https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/replicate-launch-rna-ehlers-apple-tree/606210/(2021).

- 133.Al Idrus A Shape builds out RNA editing tech with a major $112M funding boost. FierceBiotech https://www.fiercebiotech.com/biotech/shape-therapeutics-reels-112m-to-spur-rna-editing-tech (2021).

- 134.Baek M et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 373, 871–876 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Senior AW et al. Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 577, 706–710 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kuhlman B & Bradley P Advances in protein structure prediction and design. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 681–697 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Langan RA et al. De novo design of bioactive protein switches. Nature 572, 205–210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhang K et al. Cryo-EM structure of a 40 kDa SAM-IV riboswitch RNA at 3.7 Å resolution. Nat. Commun. 10, 5511 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]