Abstract

The COVID-19 outbreak magnified territorial inequalities and increased vulnerability among low-income groups. Inhabitants in informal settlements are structurally disadvantaged in coping with communicative diseases such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite that, the pandemic has been accompanied by the proliferation of informal settlements. This study explores how the pandemic caused the squatting on new land with the case of “Los Hornos” in suburban Buenos Aires. We used a random forest algorithm and Google Earth Engine to estimate the rapid growth of a new informal settlement from a series of satellite images from early 2020. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with inhabitants to investigate the link between squatting and COVID-19. The study revealed that squatting on new land during the pandemic was mainly due to economic difficulties, overcrowding in existing informal settlements in the metropolitan center, and speculation in the informal housing market. This case is an example of how the most vulnerable groups bore the brunt of the pandemic, how the households in the existing informal settlement were behaving similar to those in the formal housing market (i.e., away from the urban centers), and how the outbreak had also been an opportunity for collective action of squatting a new land to materialize.

Keywords: Informal settlements, Informal housing market, Google earth engine, Random forest, COVID-19

1. Introduction

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, without a vaccine, governments were forced to implement regulations and public policies to control social behavior and prevent the spread of the virus. The pandemic did not discriminate and has reached almost every corner of the world, affecting all social sectors, showing dramatic evidence of these measures' social and economic effects and their disparate impact on the most vulnerable communities. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the multidimensional vulnerability of informal settlements (Duque Franco et al., 2020). Inhabitants of these settlements live in precarious housing conditions, without tenure security and with insufficient access to essential services (UN-Habitat, 2016), and are more exposed to infections due to overcrowding.1 Physical distancing and self-quarantine have been challenging as they are involved in informal, precarious jobs, irregular income, and a lack of savings that allow them to stay home.

In cities like Buenos Aires, more than half of the inhabitants of informal settlements live in crowded conditions (in contrast to 8% in the rest of the city), and 60% live in inadequate housing (Azparren Almeira, 2021). This overcrowding led to the rapid spread of the disease in informal settlements (von Seidlein et al., 2021). As a strategy to reduce the chance of being affected, some inhabitants in densely-populated areas have decided to move to suburban and peripheral areas with less density (Liu & Su, 2021). However, the formal housing market is not an option for the most vulnerable sectors.

As COVID-19 spread, governments put in place mobility restrictions that resulted in reduced income and job losses (Gil et al., 2021). Inhabitants of informal settlements are more economically vulnerable during COVID-19 because they do not have access to regular income (Corburn, Vlahov, Mberu, & et al., 2020), and unemployment and under-employment are substantially higher in informal settlements (GCBA, 2021; Observatorio de la Deuda Social Argentina, 2017). Additionally, reduced income and job losses may have led to more people opting for informal settlements as a housing strategy (Carmona Barrenechea & Messina, 2015). This results in existing informal settlements becoming even more overcrowded or expanding or in the emergence of a new informal settlement.

This study aims to document the emergence of a new squatter settlement and explore the causes of squatting in the pandemic context. The preliminary questions guiding this research are: How fast did the new squatter settlement grow during the COVID-19 pandemic? How did mobility restrictions during COVID-19 promote the squatting of new lands? Had there been motivation other than solving housing needs during the COVID-19 pandemic?

This paper begins with a review of the literature on the nature of informal settlements, how inhabitants were affected by COVID-19, and the use of remote sensing in monitoring such settlements. Then, we describe our study area, the informal settlement “Los Hornos” in the city of La Plata in the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area. This was a new informal settlement during the time of mobility restrictions due to COVID-19. The Methods section describes the method for estimating squatter settlement expansion and conducting a semi-structured interview. The Results section reveals the settlement's rapid emergence and growth and its inhabitants' attributes. The Discussion and Conclusion sections explore the causes of squatting on new land.

2. Literature review

2.1. Informal settlements

Almost 32% of the global urban population is estimated to live in slums (UN-Habitat, 2009). The World Bank/UNCHS (2000) recognizes that “Slums range from high density, squalid central city tenements to spontaneous squatter settlements without legal recognition or rights, sprawling at the edge of cities.” Slums are characterized by wide-ranging terms in the literature that define them as informal settlements, squatter settlements, shanty towns, and self-help settlements (Rodwin, 2022; Ulack, 1978; Ward, 2015). It also has endemic names in different countries, such as villas miseries in Argentina, favelas in Brazil, jhuggis in India, and kampung in Indonesia, among others (Arif et al., 2022). Owing to the comprehensiveness of the definition of the “Slum,” the proper definition in the developing world is controversial (Gilbert, 2007). We consider the definition of informal settlements best suited to our research because (A.) informal settlements are broadly defined as squatter lands without, or in defiance of, government approval and a lack of adequate housing and residential infrastructure. The squatting of land is often thought to occur on vacant public or private land (World Bank, 2007). (B.) as a verb, informal settlement is associated with self-organized modes of production through which the low-income sectors can access housing and urban infrastructure (Dovey et al., 2020).

Diverse approaches exist regarding the nature and genesis of informal settlements. From a traditional perspective, the genesis of informal settlements can be explained by the proliferation of industrial activities. The accelerated industrialization process in developing countries has become an extensive phenomenon in the industrialized world and has been acknowledged as unavoidable. Regardless of the benefits of urban economies for countries, the rapid spread of urbanization results in the unplanned expansion of cities, which leads to other consequences, such as informal settlement. Brunn et al. (2008) linked squatter settlements and urbanization in developing countries with their endemic economic situation. Developing countries have passed through a recognizable gradual pattern of urbanization associated with rural migration.

The second perspective lies in the interaction between the two dimensions within the city: formal and informal. This spatial and social division between different social sectors within cities has been conceptualized with the terms “dual city” (Castells & Mollenkopf, 1991) and “divided city” (Fainstein et al., 1992). According to Eckstein (2000), these settlements result from the deterioration of local economic opportunities, social problems, and increasing demand for low-income housing. Prévôt-Schapira (2000) argues that fragmentation results from the vanishing of global functioning into small units and the dilution of organic links between the different areas of the city. With the deprivation of the spatial continuum and the repetition of inequalities at different infra-urban scales, the city is represented by islands of poverty adjoining wealth isolated within urban archipelagos. Davis (2006) saw slums as resulting from urban inequalities and the segregation of some peri-urban regions. In this context, a squatter settlement is a new form of urban inequality. The author observed that these settlements are largely cut off from the subsistence solidarities of the traditional city's life, being a radical new face of inequality. He warns that these “urban badlands are the new territory from which insurgency will spring. In line with this perspective, Verma (2003) claims that the root that causes urban slums in India is not the urban property, but the speculation associated with urban greed.

The third perspective considers the positive characteristics of informal settlements, such as resilience, adaptability, resource efficiency, and sense of community (Neuwirth, 2006) or as a solution to the housing problems of low-income populations in developing countries (Turner, 1969; Wekesa et al., 2011). Some researchers see more significant social, political, and economic inequalities that lead to the development of informal settlements (Roy, 2011). In addition, informal settlements are associated with entrepreneurship, which has led some to become highly productive components of the city's economy (Brand, 2010).

The fourth perspective is associated with housing strategy in the face of a lack of a housing policy. Hardoy et al. (2001) indicated that the rapid physical expansion in most cities in developing countries is not due to land shortages but to the lack of appropriate strategies and policies at different planning levels for new development. Overcrowding occurs in particular areas of the city, and large amounts of land are left vacant or partially developed in other regions (Hardoy et al., 2001). Merklen (1997, 2010) argued that informal settlements result from a defensive strategy from the social sector, which cannot access the formal housing market. Sietchiping (2005) argues that squatter settlements manifest as failed housing and land access policies. This analysis can explain the proliferation of socio-spatial inequalities in the housing market, the city's weak housing policy, exclusionary financial and mortgage systems (Solo, 2008), and the poorly regulated real estate market (Marcos & Mera, 2018). Barriers to accessing the formal housing market among low-income and informal immigrants are due to the high cost of formal housing and stringent prerequisites for renting a home. Consequently, these population sectors have created new strategies to solve their housing needs. One such strategy is squatting (Van Gelder et al., 2013).

The fifth perspective emphasizes the “squatting organizer role.” Squatter organizers, called punteros in Argentina (fixers or brokers), are social actors associated with clientele relationships with the community, maintain links, and have patronage from local and national political leaders, government officials, and local law enforcement agencies (Lanjouw & Levy, 2002). Although tenure security is a rule in informal settlements, there is no program to improve its conditions, except in some cases through political patronage. The punteros may also benefit politically from their local power, but in exchange, they are often highly receptive to the needs of the communities, building trust over time by developing personal relationships with households (Auyero, 2000). Clientelism locks residents of informal settlements into dependency, as political punteros have little incentive to allow the poor to access land and services independently (Benjamin, 2005).

It is necessary to incorporate the above-mentioned perspectives into the study design, data collection, and analysis of informal settlements. The genesis of the new informal settlement can be explained as a housing strategy for low-income sectors in the city, the product of the lack of a housing policy, motivated by squatter organizers, and the proliferation of an informal housing market that can only occur in a fragmented urban space. In addition, we consider the social stratification within informal settlements created by housing tenure, which makes preferences and interests differ greatly among de facto owners, landlords, and tenants (Ogas-Mendez & Isoda, 2022). The context of COVID-19 makes this case different from that of the previous squatting process. The pandemic accelerated the process of squatting, settlement of the land, and proliferation of the informal housing market in the context of high social effervescence and the reduction of vigilance from the State.

2.2. Pandemic and the informal settlements

Agglomeration and dispersion continue to influence city structure and population density (Ahlfeldt et al., 2015). The COVID-19 pandemic has reduced the desirability of large cities and dense neighborhoods, and the dispersion tendency has risen again since the outbreak of COVID-19. The pandemic has shifted housing demand away from urban areas with a high population density (Delventhal et al., 2022; Liu & Su, 2021; Ramani & Bloom, 2021).

Informal settlements in metropolitan areas have high levels of density and low levels of health infrastructure; social distance is not feasible if such a protocol does not come with concomitant economic support targeted to the vulnerable population in these settlements (Wasdani & Prasad, 2020). Prevention measures, such as hand washing or working from home, may not be possible because of limited water supply or informal sector employment (Corburn, Vlahov, Mberu, & et al., 2020). Experts have warned that populations with fewer resources are more vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19, particularly in informal settlements (Corburn, Vlahov, Mberu, & et al., 2020). Von Seidlein et al. (2021) explored how overcrowding in informal settlements facilitates the transmission of COVID-19, underlining the importance of identifying the population and geographic areas most at risk of infection to reduce levels of transmission. Azparren Almeira (2021) analyzed the impact of COVID-19 on the informal settlements in Buenos Aires, as well as the public policies implemented and the role of territorial organizations in reducing the pandemic vulnerability in these settlements. Using a qualitative approach based on semi-structured interviews with key informants and official documents, she revealed how the spread of COVID-19 has a differential impact on informal settlements in relation to the rest of the city, highlighting the existing social and territorial inequalities.

2.3. Research objective

Despite vulnerabilities toward communicative disease in the informal settlement, there had been an accelerated proliferation of the informal settlement and, in its extreme, a rapid formation of a new squatter settlement. This study aims to delve into housing strategies among low-income groups during the pandemic by understanding the squatting process of a newly emerged informal settlement. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a rare opportunity to document and analyze the emergence of squatter settlements in real-time, and such knowledge is hardly available in the existing literature. Despite the particularities of the pandemic, the extreme economic and social condition during the pandemic elucidates the usual circumstances that squatters and vulnerable social groups face, and the outcome is expected to contribute in a better understanding of the phenomenon of informal settlement.

3. Study area

The case study selected for this research is the new informal settlements called “Los Hornos,” located in the administrative location with the same name in La Plata City (LPC) in the province of Buenos Aires. LPC, is the administrative capital of the province of Buenos Aires, located at the southern end of the Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area. The city is separated from the City of Buenos Aires (CBA) by two dense forest reserves: The “Reserva de Punta Lara " and the “Parque Pereyra Iraola.” The distance to the CBA is approximately 50 km, which makes many inhabitants of the city commute to the CBA. The city has 171 informal settlements (RENABAP, 2022) with an estimated population of 85,000 inhabitants. These informal settlements are mostly located on the fringes of the built-up areas of LPC (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Informal Settlements in La Plata. The locations of informal settlements based on TECHO (2018), background image from Google Earth Engine.

The proliferation of these settlements exposes weak housing policies and spatial fragmentation between informal settlements and the rest of the city (Ogas-Mendez & Isoda, 2021). This segregation, especially in South America, occurs primarily for socioeconomic reasons, with a subsequent concentration of low-income populations (Di Virgilio & Perelman, 2014). As a consequence of the high risk and vulnerability, the inhabitants of informal settlements have experienced disproportionately greater infection than the rest of the city. In the CBA, informal settlements have constituted the urban environment where the virus presented the highest rates of COVID-19 (Table 1 ). An example of this situation is the case of Villa 31, one of the most emblematic and overcrowded informal settlements in CBA. This informal settlement had more than half of its population affected by the virus (Clarín, 2020).

Table 1.

Number of persons infected by COVID-19 in the CBA and its informal settlements in December 2020.

| City of Buenos Aires | Informal Settlements | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,075,646 est. | 250,000 est. | ||

| Infected | 171,097 | 5.56% | 17.694 | 7.07% |

Source: CBA Ministry of Health (2022) * Estimated values Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, 2004; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, 2015); InstitutoGeográfico Nacional (2022)

To limit COVID-19 cases, the national government implemented the measures of compulsory preventive social isolation (ASPO) decreed on March 20, 2020 (Executive Decree 297/2020, 2020). However, pre-existing housing conditions in informal settlements increased their chances of becoming pandemic hotspots. Despite the high risk and vulnerability to COVID-19, the area of squatted land increased (BBC, 2020).

The new informal settlement is situated on a base airfield used by a glider club, a plain of 154 ha of land. With accelerated squatting, the field was almost entirely squatted in one and a half years (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Perimeter selection for the informal settlement “Los Hornos” in August 2019 and February 2022. Source: Google Earth Engine.

The squatting process in Los Hornos began on February 16, 2020, with 200 inhabitants building precarious houses made of sheet metal, cardboard, wood pallets, and tarpaulin (Infobae, 2021). Initially, squatting was organized by political punteros (fixers or brokers) (Infobae, 2021; La Nacion, 2022). Over the following months, under strict quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic, squatting expanded exponentially, and it became the largest squatter settlement in the province of Buenos Aires, reaching 2200 families in January 2022 (La Nacion, 2022).

4. Methods and data

4.1. Method

A mixed-method approach was adopted, including a quantitative approach for identifying informal settlements and their expansion and a qualitative approach to understand squatters’ motivations. Using numerical information to draw broad conclusions and deep descriptive text on contextual issues enables mixed-method research to produce results that are distinct from those of mono-approach research (Sosulski & Lawrence, 2008).

The identification involved using baseline land cover maps of the squatting areas generated in early 2020 and their changes until the beginning of 2022. A series of temporal satellite images were analyzed and mapped to identify new houses in the new informal settlement to compare and identify the changes and derive the growth rates.

The quantitative analysis was complemented by qualitative data collected in the field through semi-structured surveys with inhabitants involved in squatting. The qualitative analysis focused on a continuum of ideas about the reasons and motivations for squatting on new land.

4.2. Identification of the squatter settlement houses

4.2.1. Random forest machine learning algorithm

We use the random forest (RF) algorithm to classify satellite image pixels into land cover categories. The RF algorithm is a supervised classification method that constructs multiple correlated random decision trees that are bootstrapped and aggregated to classify a dataset using the mode of predictions from all decision trees (Breiman, 2001). The RF algorithm is generally more immune to data noise and overfitting and is extremely useful in classifying remote sensing data (Teluguntla et al., 2018). It is considered one of the most widely used and accurate land-cover classification algorithms (Millard & Richardson, 2015). The RF algorithm identifies squatter housing and the results are combined in ArcGIS 1.5 (ESRI) and the Geographical Information System (GIS). We classified land cover based on the six bands of 10 or 20 m resolution from the Sentinel-2 satellite. Spectral bands in the following domains were used: Bands 2, 3, 4, 8, 8a, and 11 visual (blue, green, red), near-infrared (NIR), narrow NIR, and short-wave infrared (SWIR1) (see Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Sentinel 2 bands used, source: EESA.

| Spectral band | Central wavelength (nm) | Spatial resolution (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Band 2 blue | 490 | 10 |

| Band 3 green | 560 | 10 |

| Band 4 red | 665 | 10 |

| Band 8 NIR | 842 | 10 |

| Band 8a narrow NIR | 865 | 20 |

| Band 11 SWIR | 1610 | 20 |

4.2.2. Training and test data

This study used training and test data obtained through visual inspection of high-resolution satellite images from CNES and Maxer Technologies in GEE. Training data were created for each period. We completed 357 training data for 2020, 402 training data for 2021, and 440 training data for 2022. We created 234 testing point data from the polygons of the house, grassland, and bare ground for 2022 only, and we assumed that the identification accuracy across the three periods was similar.

4.3. Semi-structured survey

A semi-structured qualitative survey is conducted to uncovers the reasons and motivations behind the phenomenon. We focused on squatters' previous socioeconomic situations, as well as their current situations and their motivation for squatting in the area during the COVID-19 outbreak. The survey took place at the end of the ASPO, following the necessary measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and at participants' homes in the informal settlement, with each observation representing a household. The households were chosen based on stratified random sampling to obtain spatially even observations that included inhabitants at the edge and high-and low-density areas in the informal settlement. The study area was divided into segments of approximately 7 ha each, and two households from each segment were selected based on a randomly generated number. The total number of observations consisted of 43 households (see Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Datasheet | |

|---|---|

| Area of Study | Los Hornos |

| Number of samples | 43 |

| Observation unit | Households |

| Collection date | November 2021 |

| Selection criteria | Two per segment (randomly selected) |

| Number of segments | 21 |

The interviews were also open-ended, allowing respondents to ask questions freely or expand the topic (Table 4 ). Analysis of the qualitative survey results was based on grounded theory. This inductive methodology provides systematic guidelines for gathering, synthesizing, analyzing, and conceptualizing qualitative data for theory construction (Charmaz, 2001). This methodology aims to explain that squatting is a housing strategy by social sectors with fewer resources to reduce their vulnerability in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 4.

Themes and questions of the qualitative survey.

| Topic | Question |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Results

5.1. Remote sensing result

5.1.1. Growth of squatter settlement

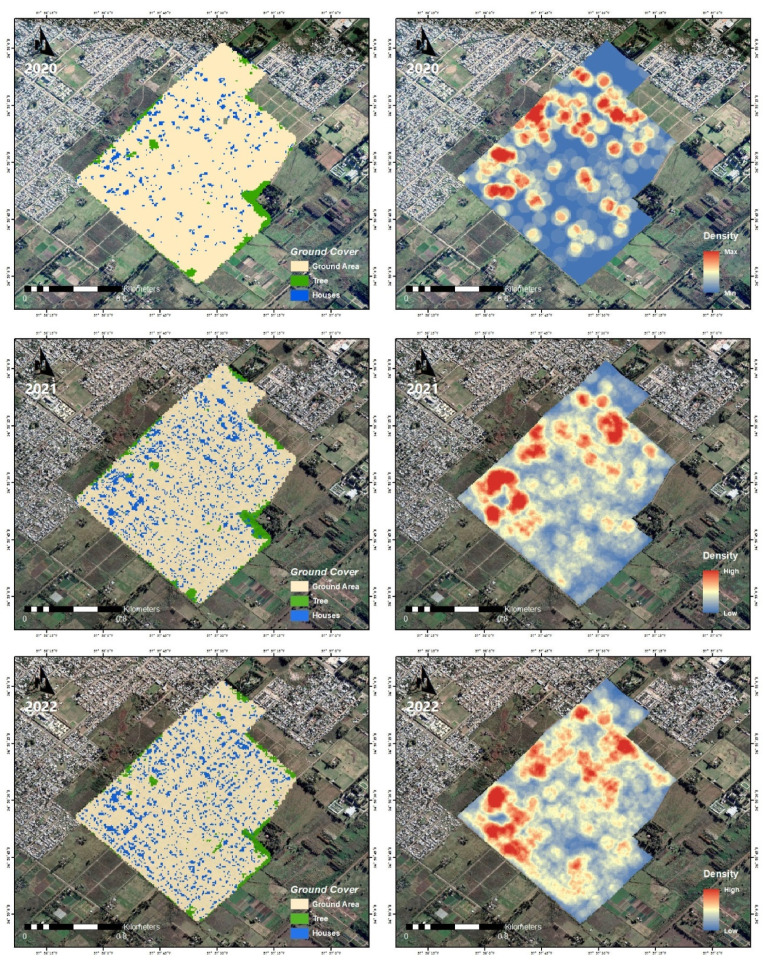

The procured satellite images revealed that informal settlements did not exist in the study area in August 2019; they first appeared in images available on Google Earth in April 2020, and, since then, the number of households has increased rapidly, a trend that is likely to have lasted until at least January 2022, the date of the latest image available in GEE at the time of writing. The land has changed its use and users, from recreational use by the gliders club to residential use by squatters. The growth continued from 2020 to 2022, becoming more densely populated, as shown in Fig. 3 . We found that the main layout of the streets follows the surrendered grid outside the study area; once the houses converge inside, they follow the pre-existing roads used by the gliders club.

Fig. 3.

Squatter housing and densities, October 2020, June 2021, and January 2022. Squatter houses did not exist in April 2019. Source: Google Earth Engine.

Table 5 shows three periods of squatting on the land. The first period is the beginning of squatting until October 2020. The second period is until June 2021, when the accelerated squatting process resulted in several dense clusters of houses (Fig. 3). The last stage is until January 2022, characterized by reduced growth.

Table 5.

Estimated changes in the housing area, April 2019 to January 2022. Confidence interval (CI) is based on user accuracy.

| Date | Area (m2) | CI (95%) |

Difference | Growth Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| April 2019 | 0 (0%) | – | – | – | – |

| October 2020 | 88,213(5.73%) | 81,649 | 94,705 | 88,213 | – |

| June 2021 | 239,115 (15.52%) | 221,323 | 256,795 | 150,902 | 171% |

| January 2022 | 299,701 (19.35%) | 277,401 | 321,861 | 60,586 | 25% |

5.1.2. Accuracy assessment and validation

To evaluate the classification accuracy, we used a multi-index test based on a confusion matrix, including producer accuracy (PA), user accuracy (UA), and overall accuracy (OA). Producer accuracy is the omission or inclusion error (from the map maker's perspective), UA corresponds to the error of commission or exclusion (from the users' perspective), and OA is the number of correct pixels divided by the total number of pixels (Foody, 2010). We propose a 95% CI to measure the classification accuracy and determine the uncertainty of an estimate. Table 6 lists the accuracy assessment results for the year 2022.

Table 6.

Confusion matrix, UA, PA, OA, of the RF classification of the study area (2022).

| Classified data | House | Grassland | Bare ground | Total | PA (%) | UA (%) | PA(CI95%) | UA(CI95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| House | 73 | 11 | 1 | 85 | 86.9 | 85.88 | 80.62–93.17 | 79.49–92.23 |

| Grassland | 8 | 89 | 7 | 104 | 87.25 | 85.58 | 81.59–92.91 | 79.8–91.36 |

| Bare ground | 3 | 2 | 40 | 45 | 83.33 | 88.89 | 74.54–92.12 | 80.73–97.05 |

| Total | 84 | 102 | 48 | 234 |

Overall accuracy 78.03%, Overall CI (95%) 74.63–81.43%.

5.2. Semi-structured interview results

5.2.1. Respondent profile

Of the 43 households we surveyed, more than 90% of the surveyed inhabitants had migrated from other informal settlements in the metropolitan area, and 65% of them were tenants in an informal settlement (Table 7 ). Regarding the current employment of the household's primary breadwinner, 58% were in the informal sector, 23% were in formal employment, and the rest were either unemployed or retired.

Table 7.

Respondent profile: Employment and Housing.

| Current Employment | The previous type of housing |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal housing |

Formal housing |

||||

| Total | Tenant | Total | Tenant | ||

| Informal employment | 25 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 25 (58%) |

| Formal employment | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 10 (23%) |

| Unemployment | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 (12%) |

| Retired | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 (7%) |

| Total | 39 (91%) | 28 (65%) | 4 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 43 (100%) |

5.2.2. Motivations for squatting

The reasons for squatting on new land are summarized in Table 8 . We divided the primary motivations for squatting into three groups: Economic, overcrowding, and other.

Table 8.

Respondents reasons for squatting, by previous housing and current employment.

| Previous housing |

Current employment |

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal Total tenants | Formal | Informal | Formal/Retired | Unemp. | |||

| Economic | 22 | 20 | 4 | 22 | 3 | 1 | 26 (60%) |

| Overcrowding | 12 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 12 (28%) |

| Sell the land | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 (12%) |

| Total | 39 (91%) | 28 (65%) | 4 (9%) | 25 (58%) | 13 (30%) | 5 (12%) | 43 (100%) |

Economic reasons include those who reported reduced income or job loss and were typically employed in the informal sector and/or renting in the informal housing market. Lack of income and the possibility of being evicted were the main reasons for squatting on new land. About half of the surveyed population's primary motivation for squatting was associated with their economic dependence on the informal labor market. They see this opportunity as a way to avoid paying the rent where they used to live or selling the land, “I am squatting the land because I lost my job during the pandemic and the social assistance is not enough, selling this land would help me improve my situation.”

Overcrowding is associated with the risk of being infected with COVID-19 in existing informal settlements. These areas are densely populated with inadequate household water and sanitation, presenting conditions for the virus's rapid spread. As vulnerable communities, the inhabitants of high-density population informal settlements feel excluded and perceive squatting on new lands as an alternative way of reducing their level of vulnerability in the face of the COVID-19 spread. From the perspective of a part of the survey, squatting the lands is a way to negotiate with the government for better living conditions, “The government locked out the whole population in the squatter settlement where I used to live, while the cases increased day by day, without giving a solution. I think if squatting increases, the government would be forced to negotiate a solution.” Other experiences suggest that moving to less overcrowded places will improve the social distance and reduce the infection risk: “Although I know the squatting place does not have services like sewers and water, I think moving to a less crowded location can reduce my family's chances to getting the virus.”

The final reasons given by the five households are related to speculative behavior in the informal housing/land market and are, in fact, a mixture of two groups. One is de facto owner-occupiers in the previous informal settlement who (informally) sold their previous land. The other is those who saw the opportunity to squat as a way to become owners of the land that could be sold later. Many interviewers also highlight how gangs or punteros squat lands to sell it, “At the beginning of the squatting, many families come to become owners of the land or sold it, but now many lands are squatted by the punteros and their people to sell it.”

Approximately 80% (35) of the surveyed population residing in this settlement had no intention of returning to their previous location after the COVID-19 pandemic ends.

6. Discussion & conclusion

Among other squatting cases, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the process of squatting new lands in the context of less monitoring by the State and social effervescence. The late and inadequate response from the State provided an opportunity to squat new lands. The combination of GEE and RF demonstrated an accelerated and continuous process of squatting on new land during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the first stage, the squatting process was mainly concentrated on the northeast edge of the study area by continuing with the existing urban fabric. This concentration was primarily motivated by accessibility to the city center and public transport. As the squatting process continued, the central and southern areas increased their population density until they filled the entire study area.

The survey results showed that 90% of squatters came from other informal settlements, and 65% had been tenants in other informal settlements. The first dominant reason for squatting in Los Hornos was a reduction in income or job loss associated with ASPO implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tenants in informal settlements were most vulnerable to economic downturns, leading to difficulties in paying the rent of informal housing and facing the chances of being evicted; they see squatting as an alternative. Squatting gives them the chance to become de facto owners in a new informal settlement and avoid paying rent. These houses acquired the land in Los Hornos by direct squatting or by informally purchasing the land from the initial squatter.

The second cause is the tread of COVID-19 in metropolitan areas. Poor sanitary conditions and overcrowding facilitated the rapid spread of the virus in informal settlements. In the face of reducing vulnerability to the pandemic, inhabitants of high-density informal settlements in metropolitan areas have adopted a strategy of squatting new lands. The response to the COVID-19 tread is similar to that in the formal housing market. Low-income groups that had difficulty accessing the formal housing market took a strategy to squat lands away from the metropolitan center for more spacious housing and environments.

The third reason is speculation in the informal housing market, which we see as a counterpart to the formal housing market. Squatting is not always conducted to solve housing needs, which in many cases is related to the speculation and proliferation of an informal housing market in these settlements (Cravino, 2008). During the mobility restriction, the State's vigilance and tolerance of specific practices allowed the squatting of new lands. Speculation sectors have also exploited the situation of squatting land to sell it in the informal land market. The context of the COVID pandemic and ASPO implementation brings about a scenario with less vigilance that facilitates the squatting of new lands. There were individuals squatting on new land, in order to sell or rent out housing on a previous informal settlement. By moving to an informal settlement in a suburb with lower rent or house prices, the squatters could draw housing equity from their previous housing and make a speculative gain by selling the (squatted) land before the price was lowered further by COVID-19. There were also those who found the opportunity to squat as a means of becoming a (de facto) owner of land, by which the land could be sold if the situation changed.

From the testimony of the surveyed population and in the media (Infobae, 2021; La Nacion, 2022), we consider “clientelism"2 as a crucial factor that materialized the emergence of a new squatter settlement. For these reasons, there has been sudden growth in the demand for cheaper and more spatious housing in the informal housing market. Punteros, perceiving such a surge in demand, used the opportunity to organize the collective squatting action. The existence of an agent who perpetrates collective action is an important determinant of whether squatted lands become squatter settlements with vested interests. From another perspective, the event demonstrates that punteros had been keen on understanding the changing needs of the urban poor.

When we enquired about the possibility of returning to their previous residence before the COVID-19 spread, nearly all the surveyed participants had no wish to return to their previous locations. Squatting new land had been a strategy of those who had been a tenant in an informal settlement. With the squatting of new lands, the tenants became de facto owner-occupiers, which means they no longer have to pay rent in the informal housing market. After seeing the well-advanced squatting of the lands, the Government of the Buenos Aires Province announced that urban redevelopment works involving title transfers would be carried out in Los Hornos (Government of the province of Buenos Aires, 2020a; b), which would encourage households to stay motivated by the opportunity to eventually formalize the tenure of the land. Although title transfers may not occur soon, people might not be able to return to their previous location because of high rent and overcrowding. People also spend money on constructing their houses or purchasing land.

Our documentation of the emergence of an informal settlement indeed reveals that the urban poor have borne the brunt of the economic difficulties associated with COVID-19, resulting in the inhabitants of the existing informal settlement seeking a cheaper alternative. Simultaneously, we see the inhabitants of the informal settlement, in the informal housing market, behaving similarly to how the rest of the citizens behave in the formal housing market, moving away from the city center to more spatious areas. Furthermore, squatters can also be strategic and opportunistic, moving for speculative reasons and becoming de facto owner-occupiers by squatting on new land. By analyzing how the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the emergence of a new informal settlement, the findings of this study revealed how the informal housing market works, which is very similar to its formal counterpart.

Authors’ contributions

Alberto Federico Ogas Mendez: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Methodology, Data Collection, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization.

Xuanda Pei: Methodology, Data Collection, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Review & Editing, Data Curation, Visualization.

Yuzuru Isoda: Conceptualization, Review & Editing.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This research is not funded by a specific financial support.

Footnotes

UN Habitat define overcrowding as when there are more than three people per habitable room (UN Habitat 2008).

Clientelism relations are carried out by punteros who canvas on behalf of a political leader (patron) by providing them with access to rough areas, operational skills, and information and delivering public goods and services. The punteros have an asymmetrical relationship based on an exchange of benefits or rights that locks informal settlement residents (clients) into a dependency, which can also be marked by coercion and violence, especially if organized crime is active in informal settlements (Davis, 2014).

References

- Ahlfeldt G.M., Redding S.J., Sturm D.M., Wolf N. The economics of density: Evidence from the Berlin wall. Econometrica. 2015;83(6):2127–2189. doi: 10.3982/ECTA10876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arif M.M., Ahsan M., Devisch O., Schoonjans Y. Integrated approach to explore multidimensional urban morphology of informal settlements: The case studies of lahore, Pakistan. Sustainability. 2022;14:7788. [Google Scholar]

- Auyero J. The logic of clientelism in Argentina: An ethnographic account. Latin American Research Review. 2000;35(3):55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Azparren Almeira A.L. In: COVID-19 and cities. The urban book series. Montoya M.A., Krstikj A., Rehner J., Lemus-Delgado D., editors. Springer; Cham: 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on informal settlements in Buenos Aires, Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- BBC Toma de tierras en Argentina: Qué hay detrás de la “oleada” de ocupación de terrenos, [Land squatting in Argentina: What is behind the “wave” of land occupation] 2020. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-54381168 October 2. Retrieved from.

- Benjamin S. 2005. Touts, pirates and ghosts. Sarai reader, no. Bare acts. 242–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brand S. Prospect Magazine; 2010. How slums can save the planet. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45(1):5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunn S.D., Hays-Mitchell M., Zeigler D.J., White E.R. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; Maryland, USA: 2008. Cities of the world: World regional urban development. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona Barrenechea V., Messina G. In: El bienestar en brechas. Un análisis de las políticas sociales en la Argentina de la postconvertibilidad. Pautassi L., Gamallo G., editors. Biblios; Buenos Aires: 2015. La problemática habitacional de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires desde la perspectiva de la provisión de bienestar [The housing problem of the City of Buenos Aires from the perspective of welfare provision] pp. 201–236. [Google Scholar]

- Castells M., Mollenkopf J. Russel Sage Foundation; New York, New York, NY: 1991. Dual city: Restructuring. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the City of Buenos Aires, Ministry of Health Actualización de los casos de coronavirus en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires [Update of the coronavirus cases in the city of Buenos Aires] 2022. https://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/coronavirus/noticias/actualizacion-de-los-casos-de-coronavirus-en-la-ciudad-buenos-aires

- Charmaz K. In: International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral science. Smelser N.J., Baltes P.B.E., editors. Pergamon; Toronto: 2001. Grounded theory: Methodology and theory construction; pp. 6396–6399. [Google Scholar]

- Clarín Coronavirus en la Ciudad: Afirman que en la villa 31 se contagiaron la mitad de los vecinos [Coronavirus in the city: They affirm that in the village 31 half the neighbors got sick] 2020. https://www.clarin.com/ciudades/coronavirus-ciudad-afirman-villa-31-contagio-mitad-vecinos_0_6QBjtr8JN.html August 24. Retrieved from.

- Corburn J., Vlahov D., Mberu B., et al. Slum health: Arresting COVID-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements. Journal of Urban Health. 2020;97:348–357. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J., Vlahov D., Mberu B., Riley L., Caiaffa W.T., Rashid S.F., Ayad H. Slum health: Arresting COVID-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2020;97(3):348–357. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravino M.C. Relaciones entre el mercado inmobiliario informal y las redes sociales en asentamientos informales del área metropolitana de Buenos Aires. Territorios. 2008;18–19:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Verso; New York: 2006. Planet of slums. [Google Scholar]

- Davis D.E. Modernist planning and the foundations of urban violence in Latin America. Built Environment. 2014;40(3):376–393. doi: 10.2148/benv.40.3.376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delventhal M., Kwon E., Parkhomenko A. JUE Insight: How do cities change when we work from home? Journal of Urban Economics. 2022;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2021.103331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio M.M., Perelman M. In: Ciudades latinoamericanas. Desigualdad, segregación y tolerancia. Di Virgilio M.M., Perelman M., editors. CLACSO; 2014. Ciudades latinoamericanas. La producción social de las desigualdades urbanas [Latin American cities. The social production of urban inequalities] pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K., van Oostrum M., Chatterjee I., Shafique T. Towards a morphogenesis of informal settlements. Habitat International. 2020;104 doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duque Franco I., Ortiz C., Samper J., Millan G. Mapping repertoires of collective action facing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal settlements in Latin American cities. Environment and Urbanization. 2020;32(2):523–546. doi: 10.1177/0956247820944823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein S. In: Social development in Latin America: The politics of reform. Tulchin J., Garland A., editors. Lynne Rienner; Boulder, AZ: 2000. What significance hath reform? The view from the Mexican barrio. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Decree 297/2020 (2020) Buenos Aires, Argentina (Aislamiento social, preventivo y obligatorio) [Decree 2972020, Buenos Aires, Argentina (social distancing, preventfull and mandatory)] Retrieved from. https://www.boletinoficial.gob.ar/detalleAviso/primera/227042/20200320. 2020. (Accessed April 2022).

- Fainstein S.S., Gordon I., Harloe M., editors. Divided cities: New York & london in the contemporary world. Blackwell; Cambridge, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Foody G. Assessing the accuracy of remotely sensed data: Principles and practices. Photogrammetric Record. 2010;25(130):204–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-9730.2010.00574_2.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert A. The return of the slum: Does language matter? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2007;31:697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Gil D., Domínguez P., Undurraga E.A., Valenzuela E. Employment loss in informal settlements during the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from Chile. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2021;98(5):622–634. doi: 10.1007/s11524-021-00575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of the province of Buenos Aires La provincia urbanizará más de, 160 hectáreas en los Hornos, [The goverment of the province of Buenos Aires plan redevelopt more than 160 hectares in Los Hornos] 2020. https://www.gba.gob.ar/desarrollo_de_la_comunidad/noticias/la_provincia_urbanizar%C3%A1_m%C3%A1s_de_160_hect%C3%A1reas_en_los_hornos June 3. Retrieved from.

- Government of the province of Buenos Aires Precisiones sobre el plan de urbanización integral en los Hornos, [Details on the comprehensive urbanization plan in los Hornos] 2020. https://www.gba.gob.ar/desarrollo_de_la_comunidad/noticias/precisiones_sobre_el_plan_de_urbanizaci%C3%B3n_integral_los_hornos November 6. Retrieved From.

- Government of the City of Buenos Aires Tasas de Actividad, Empleo y desocupación de la población según zona, [Rates of activity, employment, and unemployment of the population according to zone] 2021. https://www.estadisticaciudad.gob.ar/eyc/?p=27382 Retrieved from.

- UN-Habitat . Publisher: UN-Habitat; 2016. World cities report 2016: Urbanization and development–emerging futures. [Google Scholar]

- Hardoy J.E., Mitlin D., Satterthwaite D. Earthscan Publications London; 2001. Environmental problems in an urbanizing world: Finding solutions for cities in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. [Google Scholar]

- Infobae Toma en los Hornos: Un campo de batalla de, 160 hectáreas que enfrenta a punteros, desocupados y vendedores por internet [squatting in los Hornos: A 160-hectare battlefield that political patrons, unemployed, and informal internet land sellers against each other] 2021. https://www.infobae.com/politica/2021/01/30/toma-en-los-hornos-un-campo-de-batalla-de-160-hectareas-que-enfrenta-a-punteros-desocupados-y-vendedores-por-internet January 30. Retrieved from.

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional Población estimada [Estimated population] 2022. https://www.ign.gob.ar/NuestrasActividades/Geografia/DatosArgentina/Poblacion2 Retrieved from.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos . INDEC; 2004. Anuario estadístico de la República Argentina 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos . INDEC; 2015. Anuario estadístico de la República Argentina 2015. [Google Scholar]

- La Nacion Planeadores: De un antigout club de aviones a la toma de tierras más grande de la Provincia [Gliders: From an old plane club to the largest squatting land in the Province of Buenos Aires] 2022. https://www.lanacion.com.ar/politica/planeadores-de-un-antiguo-club-de-aviones-a-la-toma-de-tierras-mas-grande-de-la-provincia-nid30012022/ January 30. Retrieved from.

- Lanjouw J.O., Levy P.I. Untitled: A study of formal and informal property rights in urban Ecuador. The Economic Journal. 2002;112(482):986–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Su Y. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for density: Evidence from the U.S. housing market. Economics Letters. 2021;207 doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2021.110010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos M., Mera G. Migración, vivienda y desigualdades urbanas: Condiciones socio-habitacionales de los migrantes regionales en Buenos Aires. INVI. 2018;33(92):53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Merklen D. Un pobre es un pobre. La sociabilidad en el barrio: Entre las condiciones y las prácticas. Revista Sociedad. 1997;11 [Google Scholar]

- Merklen D. 2010. Pobres ciudadanos. Las clases populares en la era democrática (Argentina 1983-2003). Buenos Aires. [Google Scholar]

- Millard K., Richardson M. On the importance of training data sample selection in random forest image classification: A case study in peatland ecosystem mapping. Remote Sensing. 2015;7(7):8489–8515. [Google Scholar]

- National registry of popular neighborhoods (RENABAP) Listado de Barrios Populares de Argentina [List of Informal Settlements in Argentina] 2022. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/desarrollosocial/renabap/tabla

- Neuwirth R. Routledge; New York: 2006. Shadow cities: A billion squatters, a new urban world. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio de la Deuda Social Argentina (UCA) Estudios sobre los procesos de integración social y urbana en tres villas porteñas. 2017. http://wadmin.uca.edu.ar/public/ckeditor/2017-Observatorio-Informes_Defensoria-CBA-24-10-VF.pdf Retrieved from.

- Ogas-Mendez A.F., Isoda Y. Examining the effect of squatter settlements in the evolution of spatial fragmentation in the housing market of the City of Buenos Aires by using geographical weighted regression. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2021;10(6):359. doi: 10.3390/ijgi10060359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas-Mendez A. Federico, Isoda Yuzuru. Obstacles to urban redevelopment in squatter settlements: The role of the informal housing market. Land Use Policy. 2022;123 doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prévôt-Schapira M.-F. América Latina, la ciudad fragmentada. Revista de Occidente. 2000;230–231:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ramani A., Bloom N. The donut effect: How COVID-19 shapes real estate. SIEPR Policy Brief, January. 2021:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwin L. Taylor & Francis Group; Oxfordshire, UK: 2022. Shelter, settlement & development. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Slumdog cities: Rethinking subaltern urbanism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2011;35(2):223–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Seidlein L., Alabaster G., Deen J., Knudsen J. Crowding has consequences: Prevention and management of COVID-19 in informal urban settlements. Building and Environment. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sietchiping R. Third urban symposium on land development, urban policy and poverty reduction. 2005. Prospective slum policies: Conceptualisation and implementation of A proposed informal settlement growth; pp. 4–6. Brazilia, DF. [Google Scholar]

- Solo T.M. Financial exclusion in Latin America—or the social costs of not banking the urban poor. Environment and Urbanization. 2008;20(1):47–66. doi: 10.1177/0956247808089148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sosulski M.R., Lawrence C.K. Mixing methods for full-strength results. Two welfare studies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2008;2(2):121–148. doi: 10.1177/1558689807312375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- TECHO National survey of squatter settlements 2018. 2018. http://datos.techo.org/dataset?organization=techo-argentina Retrieved from.

- Teluguntla P., Thenkabail P.S., Oliphant A., Xiong J., Gumma M.K., Congalton R.G., Huete A. A 30-m Landsat-derived cropland extent product of Australia and China using random forest machine learning algorithm on Google Earth Engine cloud computing platform. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. 2018;144:325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2018.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. In: The city in newly developing countries: Readings on urbanism and urbanization. Breese G., editor. Prentice Hall; 1969. Uncontrolled urban settlement: Problems and policies; pp. 507–534. [Google Scholar]

- Ulack R. The role of urban squatter settlements. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1978;68:535–550. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat . Routledge; London, UK: 2009. Planning sustainable cities: Global report on human settlements 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Habitat . 2008. Principles recommendations population housing censuses, Statistical papers Series M No 67/Rev2. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder J.L., Cravino M.C., Ostuni F.N. Movilidad social espacial en los asentamientos informales de Buenos Aires, Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação e Pesquisa, Planejamento Urbano e Regional. Estudos Urbanos e Regionais. 2013;15(2):123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Verma G. Penguin; New Delhi: 2003. Slumming India: A chronicle of slums and their saviours. [Google Scholar]

- Ward P.M. Housing policy in Latin American cities. Routledge; London, UK: 2015. Latin America's “Innerburbs”: Towards a new generation of housing policies for low-income consolidated self-help settlements; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wasdani K.P., Prasad A. The impossibility of social distancing among the urban poor: The case of an Indian slum in the times of COVID-19. Local Environment. 2020;25(5):414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Wekesa B.W., Steyn G.S., Otieno F.A.O. A review of physical and socio-economic characteristics and intervention approaches of informal settlements. Habitat International. 2011;35(2):238–245. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2007. Dhaka: Improving living conditions for the urban poor. Bangladesh Development Series Paper 17. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank/UNCHS (Habitat) Cities alliance for cities without slums: Action plan for moving slum upgrading to scale, special summary edition. 2000. https://www.citiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/ActionPlan.pdf