Abstract

The application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of municipal secondary effluents (MSE) in developing tropical countries is the main topic of this review. Alternative technologies such as stabilization ponds and upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) are vastly applied in these countries. However, data related to the application of solar photo-Fenton to improve the quality of effluents from UASB systems are scarce. This review gathered main achievements and limitations associated to the application of solar photo-Fenton at neutral pH and at pilot scale to analyze possible challenges associated to its application as post-treatment of MSE generated by alternative treatments. To this end, the literature review considered studies published in the last decade focusing on CECs removal, toxicity reduction and disinfection via solar photo-Fenton. Physicochemical characteristics of effluents originated after UASB systems alone and followed by a biological post-treatment show significant difference when compared with effluents from conventional activated sludge (CAS) systems. Results obtained for solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE in developed countries indicate that remaining organic matter and alkalinity present in UASB effluents may pose challenges to the performance of solar advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). This drawback could result in a more toxic effluent. The use of chelating agents such as Fe3+-EDDS to perform solar photo-Fenton at neutral pH was compared to the application of intermittent additions of Fe2+ and both of these strategies were reported as effective to remove CECs from MSE. The latter strategy may be of greater interest in developing countries due to costs associated to complexing agents. In addition, more studies are needed to confirm the efficiency of solar photo-Fenton on the disinfection of effluent from UASB systems to verify reuse possibilities. Finally, future research urges to evaluate the efficiency of solar photo-Fenton at natural pH for the treatment of effluents from UASB systems.

Abbreviations: AOP, Advanced Oxidation Processes; ARB, Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria; ARG, Antibiotic-Resistant Genes; CAS, Conventional Activated Sludge; CECs, Contaminants of Emerging Concern; CPC, Compound Parabolic Collector; DOM, Dissolved Organic Matter; ERA, Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment; HRT, Hydraulic Residence Time; LA, Latin America; MEC, Measured Environmental Concentration; MSE, Municipal Secondary Effluent; MWWTP, Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant; NOEC, Non-Effect Concentration; NOM, Natural Organic Matter; PNEC, Predicted No Effect Concentration; QSAR, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; RPR, Raceway Pond Reactor; RQ, Risk Quotient; SODIS, Solar Disinfection; TP, Transformation Product; UASB, Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket; UASB + PT, UASB Followed by Post-treatment; WET, Whole Effluent Toxicity

Keywords: AOP, Urban wastewater, Neutral pH, UASB post-treatment, Solar photo-Fenton

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

UASB systems are frequently used in developing areas to treat municipal wastewater.

-

•

Dissimilarity amidst UASB and CAS effluents challenges the use of solar AOPs.

-

•

Lack studies on solar photo-Fenton application for UASB effluent improvement.

-

•

Fractionated iron addition in photo-Fenton is promising for UASB effluent treatment.

-

•

AOPs must be explored as UASB post-treatment strategies.

1. Introduction

Municipal wastewater treatment plants (MWWTP) worldwide aim to remove suspended particles, organic matter, nutrients and pathogens from domestic sewage (Giannakis et al., 2017) prior to discharge or reuse. However, most MWWTPs in developing countries lack a tertiary treatment stage due to restricted investments in sanitation. Thus, resulting in limited removal of nutrients and pathogens (Noyola et al., 2012). Moreover, in the absence of an advanced treatment stage, persistent compounds, especially non-biodegradable chemicals, may resist aerobic and anaerobic biological treatment processes, thus remaining in municipal secondary effluent (MSE).

Many recent studies have focused on the improvement of MSE quality by removing persistent compounds and pathogens and reducing toxicity to allow for its reuse in irrigation or a safer discharge to the environment (Costa et al., 2021b; Gonçalves et al., 2020; Maniakova et al., 2022; Rizzo et al., 2020). Most of these studies concern the removal of micropollutants (MPs) from MSE. MPs occur in low concentrations (ng L−1–μg L−1) in environmental matrices and constitute daily use products (licit and illicit drugs, hormones, personal care products and personal hygiene products, etc.) and their metabolites, all of which end up in municipal wastewater (Rizzo et al., 2019; Starling et al., 2019). Due to recent interest in the effects promoted by MPs on aquatic biota and human health and lack of legal standards related to their occurrence in the environment and removal from MSE, these pollutants have also been referred to as contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) (Arzate et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2019).

CECs may reach surface water via wastewater discharge generating potential risks for human health, animals, and the environment. Among CECs, pharmaceuticals have been associated to ecotoxicological risks (Sodré et al., 2018) and adverse effects upon aquatic organisms, depending on exposure route, bioavailability, susceptibility, and stability (Espinosa-Barrera et al., 2021). Marson et al. (2022) concluded that from the high load of CECs present in municipal wastewater and reaching surfaces waters, most are pharmaceutical drugs. In fact, concentrations of some pharmaceutical drugs (e.g. sulfamethoxazole and 17α-ethynylestradiol) were higher in the output of MWWTP when compared to the inlet due to difficulties associated to the analytical detection of low solubility compounds which are usually excreted in the conjugated form, yet present in detectable form in the outlet (Plósz et al., 2010; Queiroz et al., 2012). Hence, most studies regarding the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE target the removal of pharmaceutical drugs.

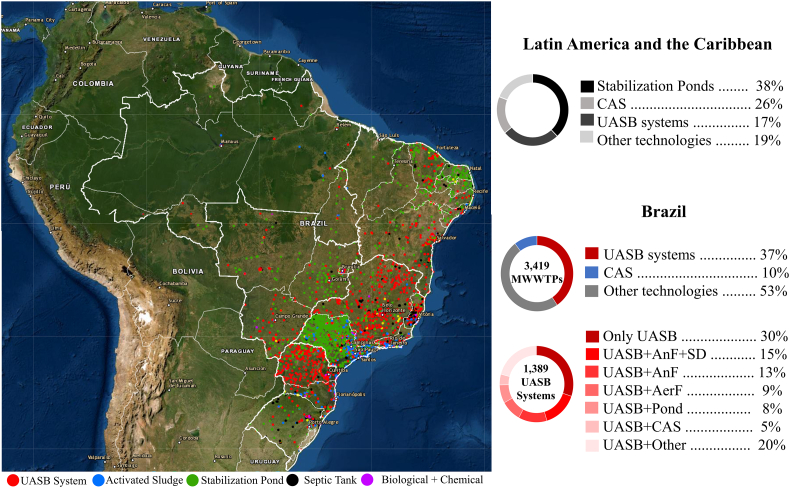

Most of the published studies aiming at the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE are performed with effluents from conventional activated sludge (CAS). However, results obtained in these studies do not apply to the reality in Latin America (LA), where main technologies applied in MWWTP are stabilization ponds (38 %), activated sludge (26 %), and Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) (17 %) (Noyola et al., 2012; Von Sperling, 2016). Fig. 1 illustrates the application of these technologies in LA with a special focus in the application of UASB reactors for the treatment of MWW in Brazil, as it is the biggest and most populous country in the region.

Fig. 1.

Wastewater Treatment Technologies applied in Brazil focused on Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket reactors (UASB) followed by different systems. Note: UASB – Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket; CAS – conventional activated sludge; AnF – anaerobic filter; SD – secondary decanter; AeF – aerobic filter; pond – stabilization ponds.

Source: Adapted from ANA (2020).

The number of UASB reactors applied for domestic wastewater treatment in Brazil (1389 units) is nearly four-fold higher than that of CAS reactors (359 units). UASB reactors correspond to 37 % of treatment units in Brazil, compared to 9 % for CAS (ANA, 2020). Considering other LAC countries, UASB reactors used for municipal wastewater treatment in Colombia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala and Mexico correspond to, respectively, 25 %, 18 %, 17 % and 10%of all existing MWWTP in these countries (Noyola et al., 2012). As MSE treated via anaerobic and aerobic processes are different as according to physicochemical quality (Oliveira and Von Sperling, 2008), it is critical to investigate the performance of advanced treatment technologies for the removal of CECs and pathogens for effluents generated from anaerobic treatment systems applied in LA.

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), such as UVC-H2O2, Fenton, photo-Fenton, ozonation, and UV-TiO2, are based on the generation of highly reactive oxidizing compounds such as hydroxyl radicals (HO•). These processes have been increasingly studied and implemented as post-treatment of MSE (Rizzo et al., 2019). Special attention has been given to solar irradiated AOPs (Malato et al., 2009) which represent valuable alternatives in developing countries located in tropical areas, such as Latin America, as these regions receive high levels of incident solar radiation and suffer from lack of investment in wastewater treatment facilities.

The solar photo-Fenton process is based on the generation of HO•. The reaction is catalyzed by iron in the presence of an oxidant (H2O2, persulfate) and cyclical oxidation/reduction of iron occurs in the system. The classic Fenton reaction (Eq. (1)) takes place in the dark, generating HO•. The process is enhanced under irradiation as the photolysis of ferric ions produces HO• and accelerates Fe2+ cycling (Eq. (2)). In addition, iron hydroxides present in the system absorb radiation in the visible range (<450 nm), thus corresponding to an additional route for the formation of HO• (Eq. (3)) (Pignatello et al., 2006).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The photo-Fenton process is commonly conducted at acid pH as hydrated iron ions predominate in this pH (FeOH2+,48 %, pH 2.8 and 25 °C, 0.5 M of ionic strength), thus corresponding to maximum efficiency of the H2O2 catalysis reaction (Pignatello et al., 2006). Despite better performance under acidic conditions, pH adjustment prior and after treatment may increase process costs and risks associated with the storage of chemical reagents and sludge disposal. Hence, there is high interest in performing solar photo-Fenton at circumneutral pH and the scientific community has proposed different strategies for this purpose.

Despite broad use of anaerobic wastewater treatment systems in LA and the disparity between effluents generated from anaerobic and aerobic wastewater treatment processes, most studies have applied solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of CAS effluent. Thereafter, there is a gap in the literature regarding the assessment of solar photo-Fenton performance towards CEC removal, disinfection, and toxicity reduction in effluents from anaerobic treatment systems. Considering intense application of anaerobic treatment systems in tropical developing countries and challenges posed by natural organic matter and ions present in these effluents upon AOPs (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019), it is critical to elucidate the effectiveness of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of anaerobic effluents.

In this context, this review aims (i) to compare the quality of effluents resulting from domestic wastewater treatment via CAS systems operating worldwide with UASB systems operating mainly in LAC; and (ii) to discuss challenges associated to post-treatment of UASB effluents via solar photo-Fenton in light of studies carried out worldwide to assess the removal of pharmaceutical drugs and pathogens from MSE, as well as toxicity responses. This content is valuable for evaluating the feasibility of solar photo-Fenton application as post-treatment of MSE from anaerobic treatment systems.

2. Quality of MSE originated from CAS and anaerobic systems

Physicochemical quality of effluents originated from secondary municipal wastewater treatment plants which apply CAS, UASB and UASB followed by post-treatment (UASB + PT) systems was investigated by a literature review using the keywords “UASB effluent” AND “post-treatment UASB effluent” AND “quality”. All data regarding UASB effluent quality presented in Fig. 2 were obtained from UASB systems operating in developing countries (Aiyuk et al., 2004; Amildon Ricardo et al., 2018; Antonio da Silva et al., 2021; Bhatti et al., 2014; Bressani-Ribeiro et al., 2021a; Cardinali-Rezende et al., 2013; De Almeida et al., 2009; Espinosa et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2020; Komolafe et al., 2021; Lopes et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2014; Marson et al., 2020; Oliveira and Von Sperling, 2008; Paniagua et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021a; Vassalle et al., 2020a, Vassalle et al., 2020). According to these studies, post-treatment systems following UASB reactors include aerated filter, anaerobic filter, trickling filter, facultative pond, maturation pond and, to a lesser extent, coagulation/flotation unit. No data was available for UASB effluent quality in developed countries as the application of UASB in these countries is limited to the treatment of industrial wastewater (Chan et al., 2009). Yet, physicochemical quality data for MSE derived from CAS systems operated in developed regions is abundant. Data on CAS effluent quality (Fig. 2) was extracted from studies related to CAS systems operating worldwide (Arzate et al., 2020, Arzate et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2020; De la Obra Jiménez et al., 2019; Dimane and El Hammoudani, 2021; Freitas et al., 2017; Salaudeen et al., 2018; Soriano-Molina et al., 2021, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a; Starling et al., 2021a; Vilela et al., 2022).

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical and biological characteristics of effluents generated from the treatment of municipal wastewater by conventional activated sludge (CAS), upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor (UASB), upflow anaerobic sludge blanket followed by post-treatment (UASB + PT): A) pH; B) conductivity; C) turbidity; D) total suspended solids (TSS); E) chemical oxygen demand (COD); F) dissolved organic carbon (DOC); G) total inorganic carbon (TIC); H) Escherichia coli. The letters a, b, and c indicate the significant difference (α = 0.05). Note: CAS/Strip shows the prior acidification with H2SO4 to perform (HCO3−/CO3−2) strip regarding the solar photo-Fenton post-treatment.

Statistical analysis was performed using the BioEstat 5.3 free software (Tefé, Amapá, Brazil). Physicochemical and biological characteristics of effluents from CAS, UASB and UASB + PT were compared by Kruskal-Wallis (5 % significance level, α = 0.05) followed by the Dunn non-parametric multiple comparisons test (5 % significance level, α = 0.05). Regarding dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and total inorganic carbon (TIC), significant differences were assessed by using Mann-Whitney (5 % significance level, α = 0.05) non-parametric test as there was no data available for the UASB effluent.

2.1. Effect of anaerobic effluents constituents upon solar photo-Fenton: operational conditions

2.1.1. pH

No significant difference was detected between the pH of MSE from aerobic and anaerobic treatment systems (Fig. 2A). As all secondary treatment systems generate effluents which present circumneutral pH, efforts to perform solar photo-Fenton as a post-treatment at neutral pH by using the intermittent iron addition strategy (Carra et al., 2014; Freitas et al., 2017; Starling et al., 2021a) or complexing agents (Arzate et al., 2020; Costa et al., 2020, Costa et al., 2021a; Maniakova et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021a; Soriano-Molina et al., 2021, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b, Soriano-Molina et al., 2018) must be encouraged to increase treatment applicability.

Carra et al. (2013) proposed the sequential iron addition strategy to allow for availability of dissolved iron throughout the entire reaction. Freitas et al. (2017) and Starling et al. (2021a) reported effective degradation of CECs from secondary wastewater by solar photo-Fenton at neutral or circumneutral pH using single and sequential iron additions, respectively. Alternatively, the use of iron complexing agents, which increase iron solubility to a broader pH range, also allows the performance of the photo-Fenton process at neutral pH. Poly-carboxylate acids such as oxalic acid, citric acid, ethylenediamine-N,N′-disuccinic acid (EDDS), ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), and nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) are commonly applied for this purpose (Arzate et al., 2020; Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b).

Ahile et al. (2020a) applied the iron chelation strategy for the treatment of effluents in the photo-Fenton process at circumneutral pH. Among the positive aspects of using this strategy in the photo-Fenton process are (i) H2O2 activation with the generation of HO• still takes place in the system; (ii) enhanced iron solubility at circumneutral pH promoting faster reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ under irradiation; (iii) reactions between complexes and HO0 form species which present higher quantum yield when compared to those formed in the presence of Fe3+ (Dias et al., 2014; Moreira et al., 2017). Eqs. (4), (5) demonstrate the generalized interaction between light and chelating agents (Fe3+-L). Eq. (4) represents the photo-activation of the Fe3+-L complex which promotes a ligand to metal charge transfer, thus reducing Fe3+ to Fe2+ and allowing for a more profitable catalytic cycle of iron. In addition to this mechanism, organic radicals (L•) produced in the system may generate other reactive oxygen species (ROS) as shown in Eq. (5) (Papoutsakis et al., 2015a, Papoutsakis et al., 2015b).

| (4) |

| (5) |

Studies demonstrate a great interest in the use of Fe3+-EDDS to promote CECs removal from MSE via solar photo-Fenton (Maniakova et al., 2022, Maniakova et al., 2021; Miralles-Cuevas et al., 2021; Sánchez-Montes et al., 2022; Sánchez Pérez et al., 2020). According to Prada-Vásquez et al. (2021), this is the most popular version of solar photo-Fenton process at neutral pH for post-treatment of MSE. Mechanisms of EDDS action as a chelating agent in photo-Fenton process are shown in Eqs. (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), (11) and are related mainly to simultaneous effect of EDDS•3−, H2O2, HO• and O2•− (Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a, Soriano-Molina et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2014). The use and efficiency of Fe3+-EDDS in solar photo-Fenton for post-treatment of MSE is deeply discussed in Section 3.

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

Despite advantages associated to photo-Fenton operation at neutral pH, some studies suggest prior effluent acidification with H2SO4 for the consumption of carbonates and bicarbonates from CAS effluents. Total inorganic carbon (TIC) concentrations below 15 mg L−1 are desirable to achieved enhanced efficiency during AOP treatment (Arzate et al., 2020, Arzate et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2020, Costa et al., 2021a; De la Obra Jiménez et al., 2019; Freitas et al., 2017; Soriano-Molina et al., 2021, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b). These authors highlight that prior acidification strips carbonates and bicarbonates from MSE, which is advantageous as these molecules act as oxidative radical scavengers by (i) reacting with free radicals to generate secondary radicals with lower oxidative-reduction potential or (ii) competing for free radicals with target CECs (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019).

2.1.2. Alkalinity and conductivity

Effluents from UASB and UASB + PT (post-treatment) show significantly higher TIC (57 and 44 mg L−1; p-value 0.0002 and 0.0032, respectively) when compared to CAS effluent (15 mg L−1) (Fig. 2G). In contrast, no significant difference was detected between UASB and UASB + PT (p-value > 0.05). Monitoring of UASB and UASB + PT (trickling filter) for over 300 days (2019–2020) resulted in mean bicarbonate alkalinity values equivalent to 237(38) mg L−1 and 19(15) mg L−1 for UASB and UASB + PT effluents, respectively (Bressani-Ribeiro et al., 2021b). Conductivity is also higher (p-value < 0.05) for UASB + PT when compared to CAS + Strip (Fig. 2B).

As bicarbonates and other ions act as HO• scavengers and reduce AOP effectiveness (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019), this may be an important limiting factor to the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of UASB and UASB + TP effluents. Rommozzi et al. (2020) evaluated the effect of different inorganic ions and their concentration upon disinfection via solar photo-Fenton process at near-neutral pH (1 mg Fe2+ L−1 and 10 mg H2O2 L−1). The authors reported a more significant inhibiting effect for HCO3− ions, which presented adverse effects at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 mg L−1. For Cl−, concentrations higher than 100 mg L−1 caused inhibitory effects upon treatment. Although this work evaluated disinfection of natural water matrices rather than MSE, it stands out for demonstrating the interference of organic matter and inorganic ions, especially HCO3−, on the oxidative efficiency of the photo-Fenton process. Despite scarcity of data regarding inorganic carbon concentration in UASB effluents, conductivity values, TIC and HCO3− concentrations shown in Fig. 2B indicate that acidification may be required to reduce bicarbonates concentration prior the application of photo-Fenton process aiming at CEC removal from UASB effluent as this was proven to be an effective strategy for post-treatment CAS effluents (Klamerth et al., 2010).

2.1.3. Alternative oxidants

Another strategy to reduce the scavenging effect of ions present in MSE, such as carbonate and bicarbonate, is the application of alternative radicals, which still have high oxidative potential yet are more selective than hydroxyl radicals. This is the case of sulfate radical (SO4−•), which is generated during solar photo-Fenton when hydrogen peroxide is replaced by either persulfate (S2O82−) or peroxymonosulfate (HSO5−) as according to Eqs. (12), (13), (14), (15) (Ferreira et al., 2020; Starling et al., 2021b). As reaction rates between SO4−• and matrix components are lower than those observed for HO•, this may be a feasible strategy to enable solar photo-Fenton treatment of MSE from anaerobic treatment systems.

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

In addition, HSO5− (E0 = 1.81 V/SCE) is used as a strong oxidant to degrade organic compounds as it is easily activated by solid catalysts, heat, UV irradiation, among others, to generate SO4−• (Eq. (16)). HSO5− redox potential (E0 = 2.44 V/SCE, pH 0) increases to 3.1 V/SCE in alkaline matrices, where it can be hydrolyzed to HO•. Therefore, co-occurrence of HO• and SO4−• may happen depending on matrix pH.

| (16) |

Khan et al. (2021) reported that inorganic ions (CO32−, HCO3−, Cl− and SO42−) affected the removal of target CECs in the presence of sulfate radicals. This effect was mainly associated to HCO3− and CO32− which exert significant SO4•− quenching through reactions shown in Eqs. (17), (18).

| (17) |

| (18) |

The use of persulfate as an oxidant in solar photo-Fenton at natural pH (intermittent iron additions) without prior removal of bicarbonates was successful for the removal of CECs (60 % removal), disinfection (reduction of 3 log units of E. coli), and elimination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (2–4 log units) from CAS effluent (Starling et al., 2021a). Median conductivity of MSE was 638 μS cm−1 which is similar to that observed for UASB + PT effluents (871.5 μS cm−1). Thus, suggesting that this strategy may be effective for the improvement of MSE from UASB systems. Despite lack of data related to the conductivity of UASB effluent, mean conductivity of UASB effluent was equivalent to 841 μS cm−1 (Bhatti et al., 2014), which is similar to values observed for UASB + PT. In contrast to observations made for solar photo-Fenton in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, these results indicate that solar photo-Fenton treatment using persulfate is a promising strategy for post-treatment of UASB effluent with no need for prior acidification.

2.1.4. Turbidity and suspended solids

Turbidity and total suspended solids (TSS) may limit the application of photocatalytic processes due to the light scattering effect (Ma et al., 2021). Consequently, treatment times are increased compared to the time required to achieve the same efficiency in clear effluents (Costa et al., 2021b). There is no significant difference between turbidity of CAS effluents (6.9 NTU; n = 13) and UASB + PT effluents (10.1 NTU; n = 12) (α = 0.05) (Fig. 2C). However, UASB effluents (n = 6) showed median turbidity equivalent to 81 NTU resulting in significant difference when compared to CAS (p-value 0.0005) and UASB + PT effluents (p-value 0.0242).

Similarly, no significant difference (p-value 0.6679) was detected for TSS concentration in CAS effluents (15.5 mg L−1) compared to UASB + PT effluents (38.5 mg L−1). Yet, TSS concentration in the output of UASB effluents (64.2 mg L−1) is significantly higher than TSS concentrations in CAS effluent (p-value 0.0061) and UASB + PT effluents (p-value 0.0113). These results indicate that direct post-treatment of UASB effluent via irradiated processes will probably require a previous stage to reduce suspended solids concentrations to allow for process improvement and reduction of treatment time.

2.1.5. Natural organic matter content

Natural organic matter (NOM) present in MSE may consume oxidative radicals generated during AOP, thus decreasing the removal of target contaminants (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019). Quantification of organic matter in effluents may be measured (i) directly by using a Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Analyzer, (ii) or indirectly by quantification of oxygen required for biological (Biological Oxygen Demand, BOD) or chemical oxidation (Chemical Oxygen Demand, COD) of organic matter. Direct quantification is not affected by NOM biodegradability nor by the presence of inorganic ions and other components. Nevertheless, most studies related to the characterization of UASB effluents quantify organic content by measuring COD, probably due to lack of access to a TOC Analyzer (Fig. 2E) and absence of legal standards associated to Total Organic Carbon or Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) for wastewater disposal in developing countries. Effluents from CAS systems showed dissolved organic carbon (DOC) levels below 23 mg L−1 (median = 14.7 mg L−1), while effluents from UASB and UASB + PT showed average concentrations equivalent to 26.5 and 30.3 mg L−1, respectively. According to the few reports of DOC concentrations in UASB effluents, organic content in MSE from UASB systems differs from MSE from CAS systems (p-value 0.0288 for UASB and 0.0219 for UASB + PT). Considering COD values, CAS effluents average 49.5 mg L−1, compared with 173 mg L−1 for UASB effluents, and 110 mg L−1 in UASB + PT effluents. COD concentrations were significantly lower in the output of CAS compared to UASB (p-value 0.0003) and UASB + PT (p-value 0.0009). According to Costa et al. (2021b), NOM present in the matrix affects the degradation of CECs and disinfection of wastewater via photo-Fenton (Eq. (19)) because NOM can act as scavengers of HO• or compete with the target CECs.

| (19) |

Therefore, optimum reagent concentrations required for the removal of CEC from UASB and UASB + PT effluents via solar photo-Fenton are probably higher than those applied for post-treatment of CAS effluents.

Among LA, Brazil is the major user of UASB reactors for municipal wastewater treatment. 77 % of all MWWTP in operation in Brazil consist of stabilization ponds, followed by UASB reactors (Chernicharo et al., 2018). However, according to the bibliometric survey performed by Costa et al. (2021b), only very few studies have investigated the use of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE generated by anaerobic treatments. Therefore, data regarding solar photo-Fenton performed with UASB and UASB + TP effluents is scarce. Organic matter removal achieved by UASB is limited to 65–75 %, and the removal of pathogens ranges between 90 % and 99 %. Considering typical initial concentration of pathogen indicators in raw municipal wastewater (1 × 109 CFU mL−1), final concentrations equivalent to 1 × 108 (1 Log removal) or 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 (2 Logs removal), respectively, are higher than concentrations set for environmentally safe discharge. Therefore, a removal rate equivalent to 99 % is still not satisfactory as it results in a final concentration equivalent to 1 × 107–104 CFU mL−1 (Chernicharo, 2015; Sperling, 2008).

Median E. coli concentrations were significantly different (p-value 0.003) in CAS effluents (2.3 × 104 CFU mL−1 or MPN 100 mL−1) compared to UASB effluents (6.5 × 107 CFU mL−1 or MPN 100 mL−1). No significant difference occurs between E. coli concentrations in effluents from UASB and UASB + PT (4.0 × 106 CFU mL−1 or MPN 100 mL−1) (Fig. 2H). These results suggest that disinfection of UASB effluents via solar photo-Fenton will be more challenging when compared to CAS effluents. Considering broad applicability of UASB systems in developing countries and proved efficiency of solar photo-Fenton for disinfection of MSE, as well as the urgent need to remove antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and genes (ARG) from MSE, it is urgent to evaluate the efficiency of solar AOPs for disinfection and removal of antimicrobial resistance from UASB effluents (Starling et al., 2021b). In this sense, photo-Fenton process performed as post treatment of MSE may improve the quality of effluents providing safer discharge to the environment and decreasing risks of waterborne diseases, thus improving public health.

2.1.6. Nutrient content

UASB reactors are not effective to remove nutrients, presenting negative removal of nitrogen (−13 %) and phosphorus (−1 %) (Oliveira and Von Sperling, 2008). As these are inorganic ions, their occurrence in MSE limits the performance of photo-Fenton due to secondary consumption of hydroxyl radicals (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019). According to Giannakis et al. (2021), phosphates are unreactive compounds that act as terminal receptors and do not propagate further reactions with HO•. Among 333 MWWTP comprised of UASB reactors in Brazil, only 25 % (82 plants) contain trickling filters (TF) as a post-treatment unit (Chernicharo et al., 2018). Although there is no available substantial data on the removal of nitrogen via UASB + PT, phosphorus removal is improved by 23 % when UASB is coupled to an aerated filter, anaerobic filter, trickling filter, flotation unit, facultative pond or maturation ponds (Oliveira and Von Sperling, 2008). Therefore, the efficiency of solar photo-Fenton must be evaluated not only for UASB effluents yet also for each of these multistage systems to cover the existing knowledge gaps.

Bressani-Ribeiro et al. (2018) reviewed the main characteristics and performance of rock and plastic-bed trickling filters following UASB reactors at laboratory, pilot, and full-scale for the treatment of MWW. Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5) values ranged from 40 to 140 mg L−1 (median = 96 mg L−1), TSS concentration varied broadly between 35 and 181 mg L−1 (median = 49 mg L−1), and NH4+ concentrations were between 19 and 37 mg L−1 (median = 30 mg L−1). Median values presented for these parameters after post-treatment by TF (32 mg L−1 of BOD5, 22 mg L−1 of TSS, 19 mg L−1 of NH4+) reveal effluent quality improvement. This improvement may pave the way for the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of UASB + TF effluents.

Despite removing nitrogenous compounds, solar photo-Fenton applied as post-treatment for UASB-TF enable (i) oxidation of nitrogen compounds to NO3−, and (ii) photoreduction of NO3− to NO2− with the formation of NO2• (Zuo and Deng, 1998). Nitrate absorbs UVC radiation more readily than H2O2 (wavelengths < 250 nm), while nitrite absorbs mainly in the UVA region and extends into the visible region (Vinge et al., 2020). However, the generation of NO2• is not advantageous in Fenton-based process as it presents lower redox potential compared to HO• (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019). Moreover, there still are uncertainties regarding inhibition of photo-Fenton process by natural components of wastewater. The nitration pathway involving the HO• + NO2− mechanism could also induce the formation of aromatic nitrocompounds involving the addition of NO2• (Carlos et al., 2010).

Among all physicochemical parameters presented for CAS, UASB and UASB + PT effluents, NOM plays a critical role in the application of the photo-Fenton processes as post-treatment of MSE. Data gathered here indicate the need for a biological post-treatment following UASB reactors due to limited organic matter (COD and BOD5) removal achieved by UASB alone. In addition, it is urgent to evaluate strategies to allow for the application of photo-Fenton process as post-treatment of UASB and UASB + PT effluents, as matrix components may hinder the removal of CECs and disinfection and influence toxicity responses.

3. Predicting challenges to be faced during post-treatment of anaerobic effluents via solar photo-Fenton

There has been a rise in the interest towards the application of homogeneous solar photocatalysis to remove CECs present in aqueous matrices for the last decade. However, full-scale application of photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE is not yet a reality due to various reasons: (i) the numerous chemical compounds in fluctuating concentrations in MSE which hinders the surveillance of the totality of CECs; (ii) lack of enforcement in wastewater treatment facilities due to absence of explicit regulations aiming at the control and elimination of CECs from MSE; (iii) the presence of organic and inorganic scavengers as natural components of MSE (NOM, ions, etc.); (iv) and lack of accessible information associated to the design of photoreactors (Klavarioti et al., 2009; Maniakova et al., 2020; Schwarzenbach et al., 2006).

As CECs occur in fairly low concentrations in the environment, limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) make the analysis of CEC complex and costly. Despite these limitations, plenty of effort has been put into research projects conducted at pilot scale to simulate real circumstances imposed by post-treatment of MSE (Wang et al., 2020). Only a few studies carried out in developed countries, assess the performance of photo-Fenton considering the occurrence and removal of CECs in their actual concentrations in MSE (Arzate et al., 2020, Arzate et al., 2017; Freitas et al., 2017; Soriano-Molina et al., 2021, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a). In addition, while most studies are performed in solar chambers which simulate sunlight irradiation, recent studies have used solar photo-reactors operating at batch and continuous modes.

3.1. Solar photoreactors and operation settings

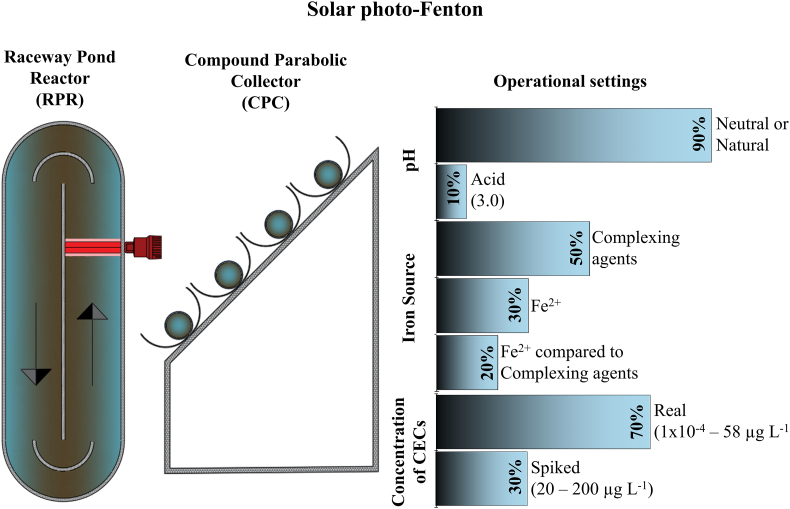

Solar photo Fenton is an alternative to remove CECs occurring in MSE. Among photoreactors designed to perform wastewater treatment via solar photocatalytic processes, options include reflective concentrating parabolic surfaces and non-concentrating collectors (Cabrera-Reina et al., 2019; Malato et al., 2007). Compound parabolic collectors (CPCs) are the most extensively low-concentrating models applied for the application of solar photo-Fenton. They consist of two connected parabolic reflective surfaces and an absorber tube in the axis. Besides the CPC, published studies have reported the use of a non-concentrating low-cost raceway pond reactor (RPR) as a sound system for the performance of solar photo-Fenton aiming at the removal of CECs from wastewater (Arzate et al., 2017; Costa et al., 2020, Costa et al., 2021a; Freitas et al., 2017; Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a, Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b, Soriano-Molina et al., 2021; Starling et al., 2021a). This reactor earns particular interest due to its higher treatment capacity and lower cost when compared to other reactors (Esteban García et al., 2018). Moreover, there are a plenty of studies for its application in a full scale, especially in the South of Spain (Maniakova et al., 2022, Maniakova et al., 2021; Miralles-Cuevas et al., 2021; Sánchez-Montes et al., 2022; Sánchez Pérez et al., 2020). Fig. 3 presents main photoreactors and information related to studies applied for the removal of pharmaceutical drugs present in MSE via solar photo-Fenton at pilot scale.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the Raceway Pond and Compound Parabolic Reactors and operational settings used in studies evaluated in this review and related to the application of solar photo-Fenton at pilot-scale for the treatment of municipal wastewater aiming at CEC removal.

Studies shown in Table 1 aimed at post-treatment of MSE via solar photo-Fenton and were developed in various regions of the world including developed countries. Only one of the listed studies investigates the efficiency of photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE in a CPC, thus demonstrating the great interest of the scientific community in RPRs. Disregarding the photoreactor, 30 % of studies performed at pilot scale analyzed the removal of target-CECs (20–200 μg L−1) spiked to MSE due to analytical limitations associated to the detection of these compounds at reduced concentration levels. Furthermore, Table 1 shows that there is a scarcity of studies that apply solar photo-Fenton using Fe2+ at circumneutral pH and great interest in the use of chelating agents such as Fe3+-EDDS in developed countries. The main achievements and limitations encountered in these studies are analyzed in this review considering possible application of photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE generated from UASB and UASB + PT. A few studies carried out with synthetic wastewater matrix were also considered due to their relevance to this subject. Table 1 summarizes key findings achieved in each of these studies.

Table 1.

Solar photo-Fenton performed in the post-treatment of secondary municipal wastewater treatment plant for the removal of pharmaceutical drugs.

| CEC | Concentration | Matrix (treatment technology) | Reactor | Reactor features | Iron Source | pH | Experimental Scale | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetamiprid (ACTM) group of 77 CECs, mainly drugs, belonging to different therapeutic groups, including some of their metabolites. | ACTM: 200 μg L−1 Total CECs: 30.3 ± 0.3 μg L−1 |

SW and MSE (CAS) | RPR (fiberglass – SW, and PVC – MWW) |

SW: 5 cm liquid depth, 120 L of total volume and a mixing time of 5 min. MWW: 80 L of total volume with 15 cm of liquid depth with a mixing time of 3 min, or 18 L of total volume, with a liquid depth of 5 cm and a mixing time of 2 min. |

Fe2+ (5.5 mg L−1) |

Acid 3.0 |

Pilot-scale | No significant difference for different liquid depths tested during continuous operation mode (87 % for 15 cm and 89 % for 5 cm). For the different HRT, removal rates were: 79 % (20 min), 84 % (40 min) and 89 % (80 min). | (Arzate et al., 2017) |

| 77 CECs, mainly drugs, belonging to different therapeutic groups, including some of their metabolites | 0.1 ng L−1 to 31 μg L−1 | MSE (CAS) |

RPR (PVC) | 0.98 m of length and 0.36 m width, divided by a central wall. A paddlewheel at 200 rpm, mixing time of ~1.52 min. | Fe2+ (3 × 20 mg L−1) |

Natural | Pilot-scale | 99 % removal of total CECs load within 90 min of treatment. However, some compounds still showed resistance to oxidation (salicylic acid). 56 % of the DOC was removed during treatment, decreasing from 20.6 to 9.1 mg L−1.Total H2O2 consumption after 90 min. | (Freitas et al., 2017) |

| Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) as a model CEC and 116 CECs including drugs, belonging to different therapeutic groups. | SMX: 50 μg L−1. Total CECs: 14 to 44 μg L−1. |

MSE (CAS) |

RPR |

Lab. scale: internal diameter = 10 cm; height = 20 cm. Lateral walls covered. Pilot scale: 19 L of total volume, channel width 22 cm and mixing time = 2 min. |

Fe2+ (20 mg L−1) Fe3+-EDDS (5.6:58 mg L−1) |

Natural | Laboratory and pilot-scale |

Lab. scale: For the Fe3+-EDDS, decrease in the liquid depth increased SMX removal, leading to >70 % removal regardless of the liquid depth. Pilot scale: 34–45 CECs were detected in wastewater. 35 ± 11 % CECs removal achieved with FeSO4 and 81 ± 17 % with Fe3+-EDDS after 15 min of reaction. |

(Soriano-Molina et al., 2021) |

| Diclofenac (DCF), Trimethoprim (TMP) and Carbamazepine (CBZ) | 200 μg L−1 of each | UP and MSE (CAS) |

CTC | Irradiated volume of 10.24 L, 8 acrylic glass tubes (150 cm length, 3.3 cm external diameter and 0.25 cm thickness). | Fe2+ (5.6 mg L−1) Fe3+-EDDS (5.6:58 mg L−1) |

Natural | Pilot-scale |

Fe2+in MWW: Dark Fenton (0 min) removed 50 % of DCF; photo-Fenton reached 85 % removal of DCF in 30 min, and 40 % CBZ removal in 120 min. Fe3+-EDDS in MWW: 99 % removal of all CECs in 15 min. |

(Maniakova et al., 2020) |

| Naproxen (NAP) | 226,36 μg L−1 | UP and MSE (UASB + PT) |

Solar reactor | Conventional glass recipient depth: 4.9 cm; diameter: 15.5 cm, irradiated surface: 189 cm2, total volume: 500 mL artificial irradiation by two black light lamps (10 W each, 350–400 nm) placed in parallel (3.5 cm) 1.0 cm above the surface | Fe3+-oxalate Fe3+-citrate Fe3+-NTA Fe3+-EDTA Fe3+-EDDS |

7.0 | Laboratory scale | Best results obtained in the presence of Fe/EDDS (1:1) and Fe/NTA (1:1), Fe/EDTA (1:2), Fe/Cit (1:3) and Fe/Ox (1:12). NAP removal from UP was faster when using H2O2 (20 kJ m−2 required) compared to S2O82− (90 kJ m−2 required). Better performance of S2O82− was observed in MWW. Fe3+-citrate complex with H2O2 was the most cost-effective alternative for both matrices. | (Silva et al., 2021a) |

| Caffeine (CAF), carbendazim (CBZ), and losartan potassium (LP) | 100 μg L−1 each | MSE (CAS) | Solar reactor and RPR |

Lab. scale: Conventional glass recipient (400 mL) under simulated solar radiation (SunTest CPS+). RPR pilot-scale: 1.22 m maximum length, 1.02 m central wall length and 0.20 m width; total volume of 12 L; 5 cm liquid depth |

Fe2+ (5 × 11 mg L−1) |

7.0 | Laboratory and pilot scale |

Lab. scale: the strategy to perform solar photo-Fenton at neutral pH using intermittent iron additions was effective for modified photo-Fenton using persulfate as oxidant. Pilot scale: final removal of CECs obtained during solar/Fe/H2O2 at near-neutral pH reached 49 % (2.5 kJ L−1). Solar/Fe/S2O82− showed higher efficiency of CECs removal (55 %) (1.9 kJ L−1). |

(Starling et al., 2021a) |

| Nimesulide (NMD), furosemide (FRS), paracetamol (PCT), propranolol (PPN), dipyrone (DIP), fluoxetine (FXT), diazepam (DZP), and progesterone (PRG) | 500 μg L−1 of each | UP and SW | Solar reactor | 1 L of total volume in a bold bottom reflector. | Fe3+-EDDS (EDDS: 0.05, 0.28 and 0.50 mmol L−1) |

Natural | Laboratory-scale | 99.9 % and 98.7 % removal of total CECs from UP and SW, respectively. | (Cuervo Lumbaque et al., 2019) |

| Acetamiprid (ACTM) | 100 μg L−1 | SW | RPR (Cylindrical PVC) |

Lab scale: Stirred tank reactors, 0.85 L total volume, 15 cm diameter, conducted in SunTest CPS. Pilot scale: RPR made of PVC, 19 L, liquid depth of 5 cm, channel width of 22 cm and mixing time of 2 min. |

Fe3+-EDDS (0.1:0.1 mM) |

Natural | Laboratory and Pilot-scale |

Lab scale: In all cases, the model was accurate to reproduce experimental data regarding ACTM removal in the first 5 min of reaction and with good prediction until 10 min. Pilot scale: results are similar to those observed in the solar simulator. Nearly 80 % removal of ACTM in winter and spring. |

(Soriano-Molina et al., 2018) |

| O-desmethyltramadol (O-DSMT), O-desmethylvenlafaxine (O-DSMV) and gabapentin (GBP) | O-DSMT: 0.32–1.98 μg L1 O-DSMV: 0.681.32 μg L1, GBP: 0.94–7.86 μg L−1 |

MSE (CAS) |

RPR (PVC) | Liquid depth of 5 cm, volume of 19 L and length of the straight section of 2.4 m. For the liquid depth of 15 cm, volume of 78 L and length of the straight section of 5.1 m. | Fe3+-EDDS (5.6:29 mg L−1) |

Natural | Pilot-Scale | Comparing kinetic constants obtained for CEC oxidation, differences between effluents are not causally related to salinity. In the continuous operation flow, 78 % (HRT 15 min) and 76 % (HRT 10 min) CECs removal were obtained in 5 cm and 15 cm depth in the RPR. | (Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b) |

| A group of 92 CEC, most of them pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals | Total load ranges from 6.2 to 58 μg L−1 | MSE (CAS) |

RPR (PVC) | Total volume of 19 L, liquid depth of 5 cm, channel width of 22 cm and mixing time of 2 min. | Fe3+-EDDS (5.6:29 mg L−1) |

Natural | Pilot-Scale | No detrimental effect of the initial concentration of the main anions upon CECs removal. Average removal of CECs for the 5 MWW effluents from CAS was 83 % (15 min; 30 W m−2). | (Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a) |

| A group of 92 CEC, most of them pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals | Total load of 15.8 ± 81 μg L−1 | MSE (CAS) |

RPR (PVC) | Total volume of 16 L, length of 0.98 m and width of 0.38 m; liquid depth of 5 cm. | Fe3+-EDDS (5.6:29 mg L−1 5.6:58 mg L−1) |

Natural | Pilot-Scale | CEC removal for both Fe3+EDDS molar ratios tested in batch were similar: 65 % (1:1) and 69 % (1:2). In continuous treatment, CEC removal was 51 ± 3 % (1:1) and 57 ± 8 % (1:2). | (Arzate et al., 2020) |

| Acetaminophen, caffeine, carbamazepine, diclofenac, sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim |

Lab scale: 100 μg L−1 Pilot scale: 20 μg L−1 |

MSE (CAS) |

RPR |

Lab. scale: internal diameter of 19 cm and height of 19 cm. Liquid depth of 7 cm (1.6 L), 10 cm (2.4 L) and 15 cm (3.9 L). The lateral walls were covered. Pilot scale: volume of 19 L, channel width of 22 cm and. Reflexive aluminum surface at the bottom. |

Fe3+-EDDS (Fe3+: 1, 2, 3, and 5.5 mg L−1) |

Natural | Laboratory and Pilot-Scale | All experimental conditions achieved maximum efficiency for all the different liquid depths tested within 15 min of reaction. The positive influence of the reflexive surface on the bottom of the reactor was more apparent with lower initial iron concentrations. | (Costa et al., 2020) |

Note: SW = simulated wastewater; MSE = municipal secondary effluent; UP = ultrapure water; CAS = conventional activated sludge; UASB + TP = Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor followed by post-treatment; RPR = raceway pond reactor; CTC = compound triangular collector. Only Arzate et al. (2017) did not perform the treatment at circumneutral pH.

All studies summarized in Table 1 are related to application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of CAS effluent aiming CEC removal, except for the analysis performed by Silva et al. (2021a) which analyzed CEC removal from an effluent sampled in the output of a UASB + PT. This confirms lack of data on the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of UASB effluents.

As shown in Fig. 2, there are significant differences among physicochemical properties of CAS, UASB, and UASB + PT effluents. Even though results obtained in studies shown in Table 1 are mostly relevant to the reality of developed countries and urbanized regions, limitations and tendencies found in these studies may guide process adaptation for its application as post-treatment of MSE from UASB reactors which are widely used for the treatment of domestic sewage in Latin America (ANA, 2017; Noyola et al., 2012).

A previous study compared three different photoreactors in the classic photo-Fenton process (FeSO4 at pH 2.8; intermittent additions of H2O2 during treatment): CPC, flat collector (FC), and RPR. The goal was to reach 75 % mineralization of four CECs (45, 90, 180 and 270 mg L−1 of DOC) (Cabrera-Reina et al., 2019). Among all tested reactors, the RPR required a longer treatment time to achieve target mineralization for both liquid depths. Even so, the economic evaluation presented for the treatment (mg DOC €−1 min−1; 10,000 m2, initial DOC of 90 mg L−1, and 15-cm liquid depth) using a RPR estimated a cost equivalent to 19.78 mg DOC removed €−1 min−1. This cost was significantly lower than costs calculated for tubular reactors (0.37 and 0.50 mg DOC removed €−1 min−1 for the CPC and the FC, respectively). Even though the RPR required a longer treatment time when compared to CPC and FC reactors, the authors concluded that the RPR is the best option for CEC removal as a lower area is necessary to treat the same volume of wastewater in this reactor compared with the other photoreactors. These findings emphasize the advantages of using RPR for the application of solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of MSE.

Cabrera Reina et al. (2020) shed new light on the influence of temperature and sunlight availability and intensity upon solar photo-Fenton performance by comparing the efficiency of this process in three different countries (Spain, Chile, and Qatar) which receive relatively high incidence of solar irradiation, yet present different climate patterns. According to the study, in addition to incident solar irradiation, climate also plays an essential role in the efficiency of solar photo-Fenton, and reactor design should take both into account for each specific application and location. Moreover, this study shows a difference in solar reactor plant design for each season in a same location. Thus, ratifying the need to assess the performance of solar photo-Fenton in various seasons or to consider the worst-case scenario (winter season) related to incident irradiation, as pointed out elsewhere (Starling et al., 2021b). After all, considering the annual average sunlight irradiation for the design of a treatment plant based on a solar technology may underestimate the critical area required to reach target CECs removal during the winter, especially in temperate regions. Therefore, there is critical need for studies concerning the operation of solar photo-Fenton in continuous flow mode and simulating different scenarios to enable the application of the treatment throughout the year and in effluents generated from other biological treatment technologies, such as UASB and UASB + PT.

Solar photo-Fenton treatment was conducted in batch in most studies listed in Table 1. Yet, continuous operation mode aiming at the degradation of acetamiprid (ACTM) as a model contaminant on CAS effluent at pH 3.0 was studied in a RPR (Arzate et al., 2017). This study demonstrated the viability of operating solar photo-Fenton in continuous mode. Experiments were first performed on synthetic secondary wastewater (SW), then as post-treatment of MSE. Different hydraulic residence times (HRT) and liquid depths were tested to optimize the removal of CECs, thus raising essential background knowledge. Considering results reported in the referred study and continuous generation of MSE in a treatment facility, it is better to work at increased depths to ensure maximum treatment capacity. Minimum CECs removal corresponded to 79 % and was observed at a HRT equivalent to 20 min. The study confirmed the feasibility of applying continuous photo-Fenton treatment at low HRT which increases chances of using this process on a full-scale. However, continuous operation is not sufficient to enable full-scale application of photo-Fenton as it is also essential to consider limitations related to optimum pH (≈2.8) for photo-Fenton operation.

3.2. Photo-Fenton operation at neutral pH: complexing agents and intermittent iron additions

Considering higher solubility of iron at acidic pH, the optimum pH range for the operation of Fenton treatments is between 2.8 and 3.0 (Tarr, 2003). However, natural matrices, such as MSE usually present neutral pH and pH adjustment increases operational costs and wastewater salinity after treatment, apart from risks associated to storage of large volumes of acid and base before and after treatment, respectively. The use of iron complexing agents has been stimulated to overcome this limitation, as these complexes increase iron solubility at near-neutral pH (Costa et al., 2021a; Maniakova et al., 2022, Maniakova et al., 2021; Miralles-Cuevas et al., 2021; Sánchez-Montes et al., 2022). Soriano-Molina et al. (2021) compared the performance of photo-Fenton treatment using Fe3+-EDDS complex with Fe2+ as iron sources at circumneutral pH in a pilot-scale (RPR). A maximum of 35 % CECs removal was achieved for Fe2+ while Fe3+-EDDS reached 81 % removal. This indicates that it is more effective to use Fe-complex as a source of iron for the treatment of MSE at neutral pH compared to Fe2+.

In this regard, Maniakova et al. (2020) compared Fe2+ with Fe3+-EDDS as iron sources for the removal of diclofenac (DFC), trimethoprim (TMP), and carbamazepine (CBZ) from ultrapure water (UP) and MSE via photo-Fenton treatment at circumneutral pH in a compound triangular collector (CTC). While 99 % removal of all CECs was obtained in the presence of Fe2+ in UP within 4 min by the dark Fenton process, a maximum of 50 % TMP degradation was achieved by dark Fenton in MSE after 120 min. In contrast, removal of target CECs by photo-Fenton in the real matrix was limited to 58 % (120 min, QUV = 12.1 kJ L−1). These results confirm the influence of matrix composition upon CEC removal via Fenton processes. The use of EDDS as a chelating agent improved solar photo-Fenton efficiency, leading to 99 % removal of CECs from MSE within 15 min (QUV = 1.2 kJ L−1). Although chelating agents have not yet been reported for the removal of CECs from UASB systems effluents, these results indicate the use of complexing agents as an appropriate strategy to conduct photo-Fenton at neutral pH. However, considering that UASB systems are used for municipal sewage treatment mainly in developing countries, costs associated to the addition of complexing agents may be a significant drawback in this region.

A recent work has evaluated the use of complexing agents to remove naproxen from effluent sampled in the output of a MWWTP which applies UASB + PT (coagulation-flocculation-ferric chloride, FeCl3 – and flotation) (Silva et al., 2021a). The study compared the performance of photo-Fenton using different complexing agents (Fe3+-oxalate (FeOx), Fe3+-citrate (FeCit), Fe3+-nitrilotriacetic acid (FeNTA), Fe3+-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Fe-EDTA) and Fe3+-EDDS and oxidants (H2O2 or S2O82−)). Treatment efficiency was strongly dependent on the Fe-complex, iron/ligand molar ratio, oxidant agent, and matrix composition. The work demonstrated that S2O82− is more efficient than H2O2 in treating UASB + PT effluent, probably due to higher selectivity and lifespan associated to sulfate radical compared to HO• (Duan et al., 2020; Wacławek et al., 2017). However, considering high commercial prices of persulfate, the option which gave the best cost-benefit was the treatment performed using FeCit + H2O2.

Still regarding the use of Fe3+-EDDS complex in the photo-Fenton treatment, Fe2+ concentration was only stable for the 1:2.5 Fe:EDDS molar ratio. This indicates that an excess of EDDS is necessary to maintain this catalyzer available during the photo-Fenton reaction applied as post-treatment of MSE. The chelating complex remained stable in the system for 120 min (Cuervo Lumbaque et al., 2019). This fact must be considered to define the most appropriate HRT to be applied for post-treatment of MSE, especially when aiming at continuous operation of solar photo-Fenton treatment in real treatment plants. In fact, some studies have proved that the removal of pharmaceutical drugs from MSE generated by aerobic systems via solar photo-Fenton occurs at the beginning of treatment indicating that photoreactor scale-up aiming at a minimum of 80 % CECs removal may consider HRT ranging from 10 to 30 min (Soriano-Molina et al., 2019b). However, as UASB and UASB + PT effluents are more complex than CAS effluent, HRT required for the removal of CECs from these matrices may be longer.

A mechanistic model for the removal of ACTM via solar photo-Fenton conducted at neutral pH in SW in the presence of Fe3+-EDDS and as a function of radiance and reactor geometry was developed by Soriano-Molina et al. (2018). As suggested in the model, UV light promotes the conversion of soluble Fe3+-EDDS into Fe2+-EDDS. Kinetic models for laboratory-scale experiments showed that the oxidation of Fe2+-EDDS by H2O2 (k = 1.9 ∙ 103 mM−1 min−1) is three orders of magnitude higher than the reaction between Fe2+ and H2O2 which occurs in the classic Fenton reaction (k = 4.6 mM−1 min−1) (Buxton et al., 1988). In contrast, the reaction between Fe2+ and H2O2 in the classic Fenton reaction generates Fe3+, which precipitates at neutral pH. This explains higher H2O2 consumption within the first few minutes of reaction when EDDS is used as a complexing agent. In addition, Fe hydroxides formed in the classic system showed lower light absorption when compared to Fe3+-EDDS. Longer lifespan of soluble iron after its decomposition in the process conducted in the presence of EDDS is advantageous, and may be attributed to the presence of Fe3+-EDDS oxidized species generated by its reaction with HO• (Huang et al., 2013). Experiments performed under real solar radiation in a RPR confirmed data adjustment to the model with regard to H2O2 consumption, total dissolved iron profile, Fe3+-EDDS decomposition, and ACTM degradation. The most important contribution of the referred study is related to the applicability of the kinetics model developed with data obtained in laboratory-scale for data obtained in large scale using RPR. Therefore, this kinetic model can be useful for solar photo-Fenton scale-up for application in real MWWTP.

Nonetheless, attention should be given to matrix composition. Model performance (Soriano-Molina et al., 2018) was evaluated for the treatment of CAS effluent samples from 5 MWWTP (Soriano-Molina et al., 2019a). The target was to maximize treatment capacity in terms of volume of MSE treated per unit of reactor surface area and time (L m−2 d−1). Three model drugs were tracked during experiments: o-desmethyltramadol (O-DSMT), o-desmethylvenlafaxine (O-DSMV), and gabapentin (GBP). The kinetic model successfully predicted reagent consumption and CECs degradation (76 % in 10 min, 78 % in 15 min, 5 cm of liquid depth). Yet, Fe3+-EDDS conversion was slightly overestimated for a liquid depth of 15 cm. Even so, the model successfully predicted H2O2 consumption and CECs removal for all effluents. Differences regarding the removal of CECs in each effluent were associated to the composition of effluent organic matter as it affects iron availability in the system. Considering higher concentration of organic matter in MSE from UASB systems compared to those from CAS systems, it is imperative to analyze the applicability of this model for post-treatment of anaerobic effluents.

Although organic matter present in MSE may hinder treatment efficiency, the use of NOM such as humic acid and humic like substance as chelating agents to enable photo-Fenton operation at neutral pH has also been studied in the past few years. According to Georgi et al. (2007), NOM are classified into humic acid, fulvic acid or humin as according to their solubility. Humic acid is insoluble at pH < 2, while fulvic acid is soluble at all pH values. Overall, humic acid molecules are larger than fulvic acids and contain more aromatic rings with a large number of attached —OH and —COOH groups, while fulvic acids hold a higher number of carbonyl and aliphatic groups (Lindsey and Tarr, 2000). These substances are known to form complexes with metal ions as they bind to carboxylate, polyphenolic and nitrogen-containing sites. The presence of carboxylic, phenolic, alcoholic, quinone, amino and amido groups enables ionic exchange, complex formation and oxidation-reduction processes (Zhang and Zhou, 2019). In this sense, special interest has been given to wastewaters generated from industrial processes and which could be a potential source of NOM to be used as iron complexing agents, such as olive mill wastewater. However, comparable removal of CECs using NOM or Fe3+-EDDS (>80 %) as complexing agents were only reached at pH 5 (Davididou et al., 2019; García-Ballesteros et al., 2018; Ruíz-Delgado et al., 2019). Prada-Vásquez et al. (2021) presented strategies for the elimination of CECs via photo-Fenton process using Ibero-American effluents as NOM sources. Despite promising results in the use NOM present in wastewaters as iron-complexes to promote the photo-Fenton processes, their concentration in these matrices was limited to a few mg L−1, thus showing limited practical application for post-treatment of MSE in real scale. In addition, as there is no data regarding the use of NOM-rich wastewaters as alternative sources of chelating agents for solar photo-Fenton treatment of UASB effluents, this could be an interesting approach for future research.

Despite inhibitory effects promoted by matrix constituents during oxidative treatments (Lado Ribeiro et al., 2019), Soriano-Molina et al. (2019b) demonstrated no detrimental impact upon reaction rate or CECs removal for different initial concentrations of the main cations and anions among CAS effluents from 5 MWWTP. Thus, the authors indicated that organic matter present in MSE is the main disturbing factor for the removal of CECs under similar treatment conditions. Although most studies perform solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of CAS effluent, other technologies (anaerobic reactors, membrane bioreactors and moving bed biological reactors) are also applied in MWWTPs and each of these technologies lead to distinct organic matter composition in MSE. Hence, solar photo-Fenton treatment conditions must be adapted mainly to the concentration of organic matter present in each MSE before its application as a tertiary treatment in real MWWTPs. Considering NOM content in MSE generated by each treatment technology, it is expected that minimum accumulated UV energy and required oxidant concentrations may follow the following order from higher to lower: UASB effluent > UASB + PT effluent > CAS effluent (Fig. 2E, F).

Arzate et al. (2020) were the pioneers to test the operational feasibility of photo-Fenton using EDDS as a chelating agent in continuous flow for three consecutive days aiming at post-treatment of MSE. Results demonstrated that percentage of CECs removal were reasonably similar for Fe3+:EDDS molar ratios equivalent to 1:1 and 1:2. Despite the difference in the total load of CECs (15.8–77.5 μg L−1) in each MSE sample, CECs removal ranged between 51 ± 3 % (20 min) and 56 ± 4 % (40 min). Similar profiles of CECs removal obtained for all samples may be associated to comparable organic matter content (DOC 14.0–22.5 mg L−1). Global degradation of CECs was equivalent to 66–67 % during continuous operation (HRT 20 min and Fe3+:EDDS 1:1) (Soriano-Molina et al., 2021).

The conception and design of a treatment plant should not only consider the capacity of the AOP to mineralize CECs. Yet, it should also account for the natural variability of solar radiance throughout the year and the incident irradiation particularities for each region. One of the options to overcome natural solar irradiation shifts is the use of Light Emitting Diode (LED) lamps for cloudy/winter days (Silva et al., 2021b). Another strategy tested to enhance photo-Fenton treatment in a RPR is to improve the optical pathway by installing a reflexive aluminum surface at the bottom of the reactor (Costa et al., 2020). This adaptation was positive for low initial iron-EDDS concentrations (0.018 mM and 0.036 mM), as higher iron concentrations increased wastewater turbidity at neutral pH, thus reducing the probability of photo-activation of the iron catalyst. Strategies such as the use of a reflexive surface to enhance light absorbance may enable the application of this process for post-treatment of UASB effluents as they present higher TSS and turbidity (Fig. 2C, D) which may scatter light reducing treatment effectiveness.

Despite various studies with chelating agents, the use of these agents adds organic matter to the matrix, increases costs, and has unknown toxicity (Ahile et al., 2020b). Thus, Carra et al. (2013) proposed the use of the intermittent iron addition strategy to overcome these limitations and enable photo-Fenton operation at neutral pH at lower costs. The strategy was further tested by Freitas et al. (2017) for post-treatment of MSE via photo-Fenton treatment in a RPR. The authors observed pH decay after each Fe2+ addition which contributed to the continuous presence of dissolved iron in aqueous solution and, consequently, to the occurrence of photo-Fenton reactions, thus leading to 99 % removal of CECs within 90 min of treatment. Iron additions occurred at 5, 15, and 20 min, yet this procedure required two times more FeSO4 than the amount applied by Soriano-Molina et al. (2021).

Starling et al., 2021a, Starling et al., 2021b studied the use of S2O82− as an alternative oxidant to perform solar photo-Fenton for post-treatment of CAS effluent at neutral pH in a pilot-scale RPR aiming at the degradation of caffeine (CAF), carbendazim (CBZ), and losartan potassium (LP) (100 μg L−1 each). This was the first study to test and confirm the efficiency of the intermittent iron addition strategy using S2O82− as an oxidant and higher removal of CECs was obtained when using S2O82− (55 %; 1.9 kJ L−1) compared to H2O2 (49 %; 2.5 kJ L−1). In contrast to Silva et al. (2021a), the study showed that the total cost (operational costs + investment costs + amortization costs) associated with the modified solar photo-Fenton process in the presence of S2O82− (0.6 € m−3) was lower when compared to traditional solar photo-Fenton (H2O2; 1.2 € m−3). In this case, the lower cost associated with treatment performance using persulfate was highly influenced by the reduced surface area required for this oxidant. Performing cost evaluations is essential to choose the most appropriate post-treatment strategy, especially for complex matrices such as UASB and UASB + PT effluents.

3.3. Transformation products formed during post-treatment of MSE treatment

Another key issue which must be investigated during solar photo-Fenton application as post-treatment of MSE is the identification of by-products formed from multiple and simultaneous degradation reactions occurring during treatment. The identification of by-products elucidates the pathway of degradation of each CEC during the oxidative process. The application of solar photo-Fenton to degrade six drugs (dipyrone, diazepam, fluoxetine, acetaminophen, propranolol, and progesterone at 500 μg L−1) at circumneutral pH in wastewater using Fe3+-EDDS (1:1 and 1:2, 15.35 mg L−1 of iron and 230 mg L−1 of H2O2) reached high degradation levels (>77 %; t30W = 57 min) (Cuervo Lumbaque et al., 2021a). The authors reported the identification of 21 by-products from the oxidation of target drugs during treatment, of which 16 were still present in samples after treatment.

Also, Sanabria et al. (2021) studied the degradation of anastrozole (50 μg L−1) in aquatic matrices via solar photo-Fenton process. Solar photo-Fenton removed 95 % of anastrozole in deionized water (t30w = 65.8 min, 5 mg Fe2+ L−1, 25 mg H2O2 L−1, pH 5.0), while the treatment performance in real wastewater was limited to 51 % (intermittent additions of iron at 10 mg Fe2+ L−1, 25 mg H2O2 L−1, pH 5.0). Five by-products of anastrozole were identified in deionized water and only two of them were also detected in wastewater. The main degradation pathways proposed by authors were demethylation and hydroxylation. The lower number of by-products detected in real wastewater is probably associated to the lower efficiency of the solar photo-Fenton process. In real matrices, NOM and inorganic substances may act as HO• scavengers and/or compete with target compounds, thus decreasing treatment efficiency (Maniakova et al., 2021; Rizzo et al., 2020).

As UASB effluent presents higher organic matter content than CAS effluent, the degradation of target CECs may be limited in this matrix resulting in a reduced number of by-products during treatment. Due to lack of studies exploring the treatment of this matrix it is not possible to conclude what are the consequences of matrix composition to degradation mechanisms occurring in this matrix. This calls attention to the critical need for research on this direction.

4. Toxicity evolution during solar photo-Fenton as post-treatment of municipal wastewater treatment plant effluent at pilot-scale

One of the leading environmental concerns associated with the presence of pharmaceutical drugs in MSE is effluent toxicity (Dalgaard, 2012) as these compound may cause effects to aquatic biota even when in low concentrations (μg L−1 to ng L−1). Hence, the strategy of the European Union (EU) to preserve ecosystem integrity involves of the removal of CECs from MSE via post-treatment. The EU has recently invested in programs that stimulate research and development of technologies that enable the removal of pharmaceuticals and antimicrobial-resistance bacteria and genes from treated wastewater before disposal in surface waters (European Commission, 2020).

The 2008/105/EC Directive of the European Parliament and the Council imposed (i) the identification of all causes of chemical pollution of surface water representing a threat to the aquatic environment (acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic organisms) and (ii) implementation of pollution control measures at the source. Also, the EU Watch List included metaflumizone, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine, dimoxystrobin, famoxadone, and 10 azole compounds to the list of substances for Union-Wide monitoring after careful revision by the Commission Implementing Decision EU/2020/1161. This selection considered the toxicity of listed substances along with sensitivity, reliability, and comparability of monitoring methods.

In addition to analytical methods that allow for monitoring of listed compounds, standardized bioassays (OECD, ISO) using different test-organisms allow for the quantification of toxic effects promoted environmental samples, such as MSE, to different trophic levels. Bacteria (e.g., Aliivibrio fischeri and Photobacterium phosphoreum), invertebrates (e.g., Daphnia magna), algae (e.g., Chlorella vulgaris and Raphidocelis subcapitata), fish (e.g., Danio rerio), and plants (e.g., Lactuca sativa and Sinapis alba) are currently used as test-organisms for this purpose. Tests sold as kits such as the Microtox bioassay (MICROTOX®), Medaka multigeneration Test (MTT), Tetrahymena thermophila bioassay (PROTOXKIT F), and bacterial luminescence test (BLT) are some of the main tests used to assess toxicity of water and wastewater samples (Tufail et al., 2020).

Table 2 presents CECs covered in the European Union's latest Watch List and toxicity data for these compounds (ECOTOX, 2022) considering acute toxicity to Daphnia magna (consumer) and chronic toxicity to Raphidocelis subcapitata (primary producer). Details on toxicity data, such as endpoints selection criteria and exposure period, is described in Rico et al. (2019). As shown in Table 1, EC50 values reported for R. subcapitata (chronic toxicity) are bellow EC50 values reported for acute toxicity with D. magna, and non-effect concentration (NOEC) values for all substances are in the range of 20 μg L−1.

Table 2.

CECs enlisted in the European Union's Watch List and their acute and chronic toxicity responses.

| Name of substance | Maximum acceptable method LOD (ng L−1) |

Daphnia magna |

Raphidocelis subcapitata |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (mg L−1) | NOEC (mg L−1) | EC50 (mg L−1) | NOEC (mg L−1) | ||

| Metaflumizone | 65 | 2.56 | 1.1 | >0.31 | 0.31 |

| Amoxicillin | 78 | >1500.00 | ND | >1000 | ND |

| Ciprofloxacin | 89 | 1.20 | 10 | 18.70 | <5.00 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 100 | 96.70 | ND | 0.52 | <0.50 |

| Trimethoprim | 100 | 92.00 | ND | 83.80 | 16.00 |

| Venlafaxine | 6 | 141.28 | ND | ND | ND |

| O-desmethylvenlafaxine | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Clotrimazole | 20 | 0.21 | ND | ND | ND |

| Fluconazole | 250 | ND | ND | ND | 3.07 |

| Imazalil | 800 | 2.02 | >1.80 | 0.73 | ND |

| Ipconazole | 44 | 1.70 | 0.13 | ND | ND |

| Metconazole | 29 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Miconazole | 200 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Penconazole | 1700 | 3.69 | ND | ND | ND |

| Prochloraz | 161 | 3.01 | ND | ND | ND |

| Tebuconazole | 240 | 4.00 | 0.49 | 2.73 | 1.19 |

| Tetraconazole | 1900 | 2.63 | 0.48 | 15.00 | ND |

| Dimoxystrobin | 32 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Famoxadone | 8.5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Note: LOD = limit of detection; ND = no data.

The implementation of this Watch List in developing countries such as those in Latin America, is a massive challenge as advanced analytical methods and sample preparation techniques (in example: Solid Phase Extraction, SPE) are required for their analysis by High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS-MS). Although these methods are able to detect these analytes in low concentrations (low LOD), they may be expensive for developing countries. In addition, occurrence of CECs in the environment does not directly reflect ecological effect upon aquatic biota as some CEC may promote toxicity even below quantification and detection limits and simultaneous occurrence of a mixture of compounds in complex matrixes, such as MSE, may promote higher or lower toxicity due to synergism or antagonism, respectively. Therefore, CEC monitoring must be performed along with toxicity assays.

Additionally, when it comes to ecotoxicity, the European Environment Agency (EEA) report No. 23/2018 lists MWWTPs as significant contributors to direct releases of all groups of pollutants into water. The chemical industry and energy supply facilities are also substantial contributors to the release of substances that promote ecotoxicity to water and indirect releases of these substances to MWWTPs (M. Granger et al., 2019). Besides, the commission of evaluation of MWWTP recognized CECs as an environmental issue, and supports the upgrade of MWWTP with post-treatment stages aiming at toxicity removal (European Commission, 2020). In this regard, the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency Report No. 6766 presented AOPs as effective post-treatment alternatives to be implemented among available advanced technologies (Sundin et al., 2017).

Regarding the evaluation of toxicity during the application of AOPs as post-treatment of MSE, different reposes have been detected: i) toxicity reduction during AOP treatment, as observed for the photo-Fenton performed under artificial radiation and for the Fenton process; ii) toxicity increase in the beginning of treatment followed by decrease; iii) toxicity increase after AOP treatment as seen for the solar photo-Fenton (Wang and Wang, 2021). Toxicity responses after AOPs may be related to many factors, such as: types of reactive species active in the system, structure and chemical properties of organic pollutants (Kow, pka, solubility, among others) present in the matrix, concentration of reactive species, the toxicity assay selected to analyze matrix effect, experimental parameters, residual oxidants, and applied catalysts. It is known that partial oxidation of organic contaminants during treatment by AOPs can generate by-products which are more toxic than their parent molecule leading to increased toxicity (Oller and Malato, 2021; Rizzo, 2011).

The application of analytical tools based on high-performance liquid chromatography to monitor and quantify CECs, their transformation products and metabolites in the environment (Pinasseau et al., 2019) is highly challenging when it comes to MSE due to matrix complexity (Hinojosa Guerra et al., 2019). Analytical methods used for the surveillance of CEC and their degradation products in this matrix may show increased LOD and LOQ values (Rizzo et al., 2020, Rizzo et al., 2019). This is critical as some compounds may still promote toxic effects even when present at concentrations levels below LOD (Oller and Malato, 2021). Hence, bioassays should be applied along with analytical monitoring to detect acute and chronic toxic effects upon aquatic biota. In addition, bioassays enable the assessment of the impact promoted by interactions between a mixture of compounds (matrix components) and test-organisms, as it usually occurs in MSE and surface water after MSE disposal.

One alternative used to quantify individual risks associated to each compound detected in the environment is the ecotoxicological risk assessment (ERA). This method associates environmental concentration of a compound with safe concentration values defined for each substance as according to results obtained in ecotoxicological assays. In ERA, measured environmental concentration (MEC) obtained for each pollutant is divided by predicted no effect concentration (PNEC) obtaining a Risk Quotient (RQ). PNEC values are calculated by dividing acute (concentration which causes an effect to 50 % of the population, EC50) or chronic effect concentrations (non-observed effect concentration, NOEC) by an assessment factor (AF) which varies from 10 to 1000. Hence, if MEC is lower than PNEC there is no risk associated to the occurrence of that compound in the environment (RQ < 1). Whereas, if MEC is equal to or higher than PNEC (RQ ≥ 1) that compound presents an ecotoxicological risk. Gosset et al. (2021) investigated ecotoxicological risk concerning 41 CECs (37 pharmaceuticals and 4 pesticides) detected in 10 MWWTPs in France by evaluating the single CECs approach and the mixture of these substances. RQ were calculated according to Perrodin et al. (2011) based on the comparison between the predicted environmental concentration (PEC) of a compound or its mixture in water courses and its PNEC data obtained from ecotoxicity responses (1 < RQ < 10 = low risk; 10 < RQ < 100 = medium risk; 100 < RQ = high risk). 19 compounds (17 pharmaceutical drugs) detected in samples represented significant risks: N,N-diéthyl-3-méthylbenzamide (DEET) (RQ = 39.84), diclofenac (RQ = 62,10), lidocaine (RQ = 125.58), atenolol (RQ = 179.11), terbutryn (RQ = 348.24), atorvastatin (RQ = 509.27), methocarbamol (RQ = 1509.71), and venlafaxine (RQ = 3097.37). Although some CECs led to a negligible risk when evaluated individually, a significant risk was detected for the mixture. This fact must be considered for the selection of post-treatment technologies to be applied for MSE improvement, as CEC removal and organic matter composition may vary as according to the technology employed in each treatment plant.