Abstract

Proteins that are expressed on membrane surfaces or secreted are involved in all aspects of cellular and organismal life, and as such require extremely high fidelity during their synthesis and maturation. These proteins are synthesized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where a dedicated quality control system (ERQC) ensures only properly matured proteins reach their destinations. An essential component of this process is the identification of proteins that fail to pass ERQC and their retrotranslocation to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation. This study by Wu et al. reports a cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the five-protein channel through which aberrant proteins are extracted from the ER, providing insights into how recognition of misfolded proteins is coupled to their transport through a hydrophobic channel that acts to thin the ER membrane, further facilitating their dislocation to the cytosol1.

Keywords: Endoplasmic reticulum, ERAD, Cryo-EM, Hrd1

Background

The ER is responsible for the synthesis of approximately one-third of proteins encoded in the eukaryotic genome, which include membrane and secreted proteins. The presence of a signal sequence on these proteins targets them to the ER membrane, where they enter this organelle as extended polypeptide chains via the well-defined Sec61 channel and must fold and assemble into their native forms as membrane or soluble proteins. The success of this process is carefully monitored by ERQC mechanisms to ensure only properly-matured proteins are trafficked further along the secretory pathway to their ultimate destinations. Equally important to cellular and organellar homeostasis is the identification of nascent proteins that fail to mature properly, which is frequently followed by their rapid removal from the ER for ubiquitin-dependent degradation by cytosolic proteasomes. This process is referred to as ER-associated degradation (ERAD) and is conserved from yeast to humans. As luminal (soluble) ERAD (ERAD-L) clients have fully entered the ER, they must be targeted back to the ER membrane, and regions that have folded must either be accommodated during their transport to the cytosol or unfolded, making this retrotranslocation process conceptually distinct and more complicated than the translocation of nascent polypeptide chains from the cytosol into the ER.

A vast number of genetic and biochemical studies conducted in yeast and mammalian cells have demonstrated a critical role for the Hrd1 ubiquitin ligase complex during ERAD-L. The Hrd1 complex is composed of several integral membrane and luminal proteins and plays an essential role in extracting misfolded proteins from the ER. However, it has remained unclear how these various components are assembled into a multi-molecular complex that can both identify and transport misfolded proteins from the ER to the cytosol. To better understand these critical steps during ERAD, Wu et al. used cryo-EM to determine the structure of two Hrd1-containing subcomplexes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which together consist of five different proteins that constitute a functional assemblage for the removal of ERAD-L clients1. Combined with biochemical assays and molecular dynamics simulations, this group has generated a credible model for the mechanisms underlying the identification and dislocation of misfolded ER proteins. This model represents a major step forward in understanding this critical process, provides directions for future work on ERAD, has implications for the disposal of clients associated with numerous ER-associated protein folding diseases, and potentially helps define how protein transport across other biological membranes occurs.

Main contributions and importance

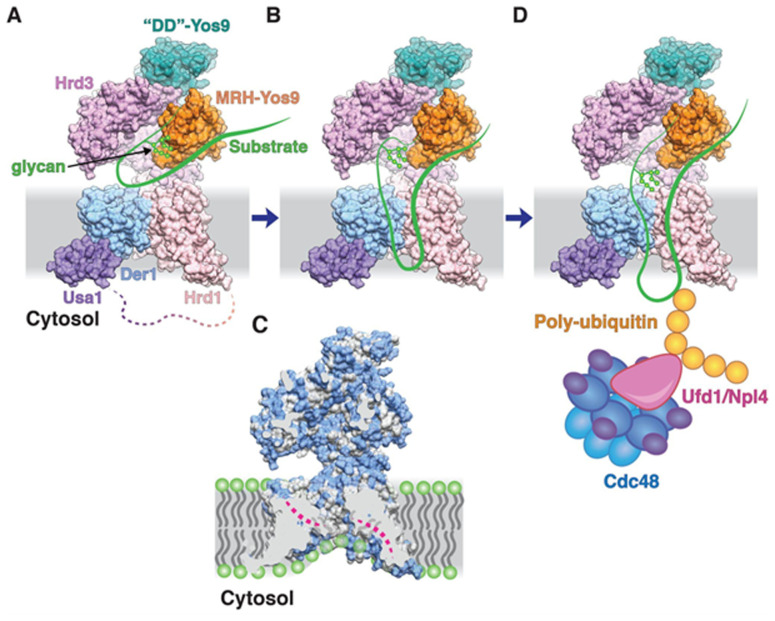

Based on the combination of several cryo-EM structures, coupled with biochemical data and molecular dynamics simulations, this paper provides a compelling model that significantly advances our understanding of three important aspects of ERAD: i) the recognition of misfolded glycoproteins by the Hrd3-Yos9 heterodimer; ii) the nature of the transmembrane channel formed by Hrd1 and Der1; and iii) the alignment of these two components to form a continuous hydrophilic channel and thin the lipid bilayer, which may be necessary to couple identification of an ERAD client with retrotranslocation through the channel (Figure 1).

Figure 1 . A model for the retrotranslocation of a misfolded ER luminal protein by the Hrd1 complex based on assembled cryo-EM structures.

(A) Space-filling model was generated from cryo-EM structures of the yeast Hrd1 complex (PDB code 6VJZ) in which segments of the 5 subunits are depicted in different colors. The predicted interactions of a misfolded glycoprotein, shown schematically in green, with the MRH domain of Yos9 positioning an extended polypeptide segment at the groove present in Hrd3. (B) The various features of the Hrd1 complex identified by cryo-EM structures are compatible with the engaged client inserting as a hairpin loop into the channel formed by Hrd1 and Der1. (C) TM boundaries predict membrane thinning by the Der1 and Hrd1 components of the complex, which was supported by molecular dynamics simulations. Phospholipid molecules are shown schematically with head groups in green and acyl chains in grey. (D) As the client emerges in the cytosol, the Hrd1 ligase catalyzes the attachment of ubiquitin molecules, which are subsequently recognized by the Ufd1/Npl4 cofactor of the Cdc48 ATPase, which pulls it out of the ER membrane. This image was reproduced with kind permission from X. Wu and T. Rapoport.

Previously, the Rapoport lab reported a cryo-EM structure for the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Hrd1, complexed with the luminal portion of Hrd3, which formed a heterodimer when isolated with the detergent decylmaltoside (DM)2. Proteoliposomes reconstituted with DM-solubilized Hrd1 and Hrd3 were capable of transporting a model client across the lipid bilayer, suggesting that the reconstituted complex remained active, but complex instability during purification led this team to subsequently explore other detergents. In this newer paper, two detergents were identified that better maintained the Hrd1-Hrd3 complex. Isolation of the complex with one of these, decylmaltose neopentylglycol (DMNG), revealed that the Hrd1-Hrd3 complex was monomeric and possessed greater ubiquitin ligase activity than the Hrd1-Hrd3 dimer. While the cryo-EM structure of the DMNG-purified monomeric complex was very similar overall to the dimeric complex, there were changes in the transmembrane helices that resulted in an open configuration for the lateral gate of Hrd1, as opposed to a closed configuration observed in the dimeric structure.

Two additional multi-pass membrane proteins that function in ERAD — Usa1 and Der1 — were then co-purified with Hrd1-Hrd3 in DMNG to generate another cryo-EM structure. This four-protein complex was also a heteromeric monomer and revealed that the lateral gates of Hrd1 and Der1 face each other within the membrane and form a hydrophilic pore, a conformation that was supported by previously reported3 and new photo-reactive cross-linking experiments1. The dimension of the region between the lateral gates also suggested a significantly thinned membrane surrounding them, an observation consistent with high-quality molecular dynamics simulations. Although this represents a different type of membrane channel than the translocon through which nascent proteins enter the ER (i.e., Sec61), membrane thinning is observed with a number of ion channels and some bacterial protein translocators (see, e.g., 4,5).

The authors next solved a cryo-EM structure for Hrd1 together with the luminal portion of Hrd3 as well as Yos9, which contains a glycan recognition motif that helps select luminal ERAD substrates. After focused refinement of the Hrd3-Yos9 components, a structure at 3.7Å resolution was obtained, which was further aided by previously published NMR structures of Yos9. This new structure revealed a groove formed between Hrd3 and Yos9 that could bind an extended polypeptide, which was positioned near the lectin recognition site of Yos9, thus suggesting a two-part recognition event that adds greater specificity during the selection of ERAD clients for retrotranslocation. The lower density of the lectin recognition portion of Yos9 is also compatible with flexibility that could contribute to client entry into the groove and/or Yos9’s ability to interact with a wider range of clients. As one-third of the proteins coded in the human genome will be translocated into the ER, and the fact that any of these sequence-unrelated proteins could misfold, significant flexibility is required in the recognition and entry of ERAD clients into the Hrd1-Der1 retrotranslocation channel.

Based on overlapping regions between these two complexes, a model was next assembled for this five-protein Hrd1 complex (i.e., Hrd1, Der1, Usa1, Hrd3, and Yos9). The model suggests the existence of a polypeptide binding groove between Hrd3 and Yos9, one that could extend all the way through the membrane-spanning regions of Hrd1 and Der1. Coupling this model with protein cross-linking data, Wu et al. propose that the substrate glycan binds Yos9, allowing the unfolded polypeptide to be inserted into the groove formed between Hrd3 and Yos9 as a loop (Figure 1). As this loop elongates, it enters the hydrophilic channel formed by Hrd1 and Der1, eventually exiting the cytosolic side of the thinned membrane where it is ubiquitinated by Hrd1 as it emerges from the channel into the cytosol. An advantage of membrane thinning might be that a shorter segment of the ERAD client is sufficient to reach the cytosolic side for ubiquitination, preventing backward movement into the ER lumen and allowing interaction with the p97 AAA-ATPase for extraction. Additional photo-cross-linking experiments with a client protein support this model.

Open questions

Ultimately, the model presented in this paper raises numerous questions and suggests future lines of inquiry. Perhaps most pertinent, a single structure with all five proteins at higher resolution is needed, as are additional mutation and cross-linking studies to determine the importance of specific residues during the selection and retrotranslocation of ERAD substrates. While challenging, the contacts made by a polypeptide “caught in the act” of retrotranslocating will also be vital. Moreover, it is likely that the continued use of different technologies, and perhaps even identification and further examination of existing particles in the cryo-EM dataset that possess different conformations, will highlight Hrd1 complex dynamics, which are proposed to be critical for interactions between members of the complex and with a translocating client. Finally, and relevant to past work2, do the dimeric DM-purified structures and the heteromonomeric DMNG-purified structures represent a closed and open conformation of the retrotranslocon, respectively, or is the DM-purified structure an artifact caused by the detergent used to isolate it?

The ER environment is chemically distinct from the cytosol, and studies on the Sec61 translocon indicate the existence of a closed gate in the absence of a translocating polypeptide chain, which helps maintain a permeability barrier. One might assume the retrotranslocon would need to be similarly gated, perhaps as indicated by the published structures1,2. It is noteworthy that Hrd1 auto-ubiquitination is essential for retrotranslocation activity. How does this alter the structure, and is this event linked to gating?

Because the failure of a single domain or region of a protein to fold renders it an ERAD client, it is likely that many clients retain folded domains or even maintain disulfide bonds during retrotranslocation. An earlier study conducted with mammalian cells demonstrated that a methotrexate-stabilized DHFR domain did not impede extraction from the ER, and the large N-linked glycans present on glycoproteins are not removed until polypeptides exit from the channel on the cytosolic side6. Can the retrotranslocon assemble into even larger structures to accommodate more complex clients with secondary structure, post-translational modifications, or even folded domains? It is also unclear how client entry into the channel is initiated and whether entry into the channel requires energy. Another mystery, based on the model, is how non-glycosylated clients are selected and inserted into the Hrd1 complex, an event that may utilize different regions on Yos9 and require ER-resident chaperones. Pertinent to this point, tunicamycin inhibits N-linked glycosylation and activates the unfolded protein response (UPR), turning many nascent proteins that would normally fold if glycosylated into ERAD clients7.

Conclusion

By combining a range of structural, biochemical and computational methods, a model has been created that suggests how misfolded proteins can be identified and transported out of the ER for destruction. Removing the trash is critical, as misfolding is common and the accumulation of misfolded proteins would rapidly jam the limited space in the ER. Even if some aspects may prove to be in need of correction or modification, having a plausible model is an essential step toward understanding, and allows a number of refined questions to be asked, as noted above. It is expected that this contribution will serve as a significant milestone that will strongly guide progress in the field.

References

- 1. Wu X, Siggel M, Ovchinnikov S, Mi W, Svetlov V, Nudler E, Liao M, Hummer G, Rapoport TA. 2020. Structural basis of ER-associated protein degradation mediated by the Hrd1 ubiquitin ligase complex Science 368:eaaz2449. 10.1126/science.aaz2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 2. Schoebel S, Mi W, Stein A, Ovchinnikov S, Pavlovicz R, DiMaio F, Baker D, Chambers MG, Su H, Li D, Rapoport TA, Liao M. 2017. Cryo-EM structure of the protein-conducting ERAD channel Hrd1 in complex with Hrd3 Nature 548:352–355. 10.1038/nature23314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 3. Mehnert M, Sommer T, Jarosch E. 2014. Der1 promotes movement of misfolded proteins through the endoplasmic reticulum membrane Nat Cell Biol 16:77–86. 10.1038/ncb2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feng S, Dang S, Han TW, Ye W, Jin P, Cheng T, Li J, Jan YN, Jan LY, Cheng Y. 2019. Cryo-EM Studies of TMEM16F Calcium-Activated Ion Channel Suggest Features Important for Lipid Scrambling Cell Rep 28:567–579.e4. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iadanza MG, Schiffrin B, White P, Watson MA, Horne JE, Higgins AJ, Calabrese AN, Brockwell DJ, Tuma R, Kalli AC, Radford SE, Ranson NA. 2020. Distortion of the bilayer and dynamics of the BAM complex in lipid nanodiscs Commun Biol 3:766–14. 10.1038/s42003-020-01419-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tirosh B, Furman MH, Tortorella D, Ploegh HL. 2003. Protein unfolding is not a prerequisite for endoplasmic reticulum-to-cytosol dislocation J Biol Chem 278:6664–6672. 10.1074/jbc.M210158200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee AS. 2001. The glucose-regulated proteins: stress induction and clinical applications Trends Biochem Sci 26:504–510. 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01908-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]