Abstract

Xylanase activity of Clostridium cellulovorans, an anaerobic, mesophilic, cellulolytic bacterium, was characterized. Most of the activity was secreted into the growth medium when the bacterium was grown on xylan. Furthermore, when the extracellular material was separated into cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions, the activity was present in both fractions. Each of these fractions contained at least two major and three minor xylanase activities. In both fractions, the pattern of xylan hydrolysis products was almost identical based on thin-layer chromatography analysis. The major xylanase activities in both fractions were associated with proteins with molecular weights of about 57,000 and 47,000 according to zymogram analyses, and the minor xylanases had molecular weights ranging from 45,000 to 28,000. High α-arabinofuranosidase activity was detected exclusively in the noncellulosomal fraction. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis revealed that cellulosomes derived from xylan-, cellobiose-, and cellulose-grown cultures had different subunit compositions. Also, when xylanase activity in the cellulosomes from the xylan-grown cultures was compared with that of cellobiose- and cellulose-grown cultures, the two major xylanases were dramatically increased in the presence of xylan. These results strongly indicated that C. cellulovorans is able to regulate the expression of xylanase activity and to vary the cellulosome composition depending on the growth substrate.

Plant cell walls, the major reservoir of fixed carbon in nature, have three major polymers: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (29). In anaerobic environments and decaying plant materials, complex communities of interacting microorganisms carry out the decomposition of lignocellulose. Among the lignocellulolytic bacteria, cellulolytic clostridia play important roles in plant biomass turnover (19). Clostridium cellulovorans (ATCC 35296) (28), an anaerobic, mesophilic, and spore-forming bacterium, produces a large extracellular polysaccharolytic multicomponent complex (with a molecular weight of about one million) called the cellulosome (7), in which several cellulases are tightly bound to a scaffolding protein called CbpA (26). The C. cellulovorans cellulosome consists of three major subunits—CbpA, P100, and P70—and several minor subunits (20, 27, 31). Recent work in our laboratory has contributed to better understanding of the molecular biology of degradation of crystalline cellulose by C. cellulovorans cellulosome (7, 8, 33). Furthermore, we have also found that C. cellulovorans utilizes not only cellulose but also xylan, pectin, and several other carbon sources (28, 32). Among these carbon sources, xylan is mainly found in secondary walls of plants, the major component of woody tissue (35) and, after cellulose, xylan is the most abundant renewable polysaccharide in plants (34).

Xylan, which has a backbone of β-1,4-linked xylopyranosyl residues contains various substituted side-groups such as acetyl, l-arabinofuranosyl, and o-methylglucuronyl residues (6). The enzymes involved in hydrolysis of the main chain of xylan are endoxylanase (1,4-β-d-xylan xylanohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.8) and β-xylosidase (β-d-xyloside xylohydrolase; EC 3.2.1.37) (6). A majority of cellulolytic clostridia (e.g., C. thermocellum and C. cellulolyticum) have reported presence of several xylanases that have been cloned and characterized (15, 22, 23). Little research has been done, however, on the extracellular xylanolytic activity in C. cellulovorans.

We are interested in understanding the response to extracellular substrates and the physiology of this bacterium when the carbon source changes from cellulose to hemicellulose. In this study, we have characterized the extracellular xylanolytic enzymes of C. cellulovorans. The extracellular xylanolytic enzymes, both cellulosomal and noncellulosomal, appear to be regulated by growth substrates. Our ultimate goal is to elucidate the relationships between the function and variety of enzymes involved in the cellulosome system of C. cellulovorans and to eventually apply this information to a biomass conversion system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture condition, and media.

Cultures of C. cellulovorans (ATCC 35296) were grown anaerobically at 37°C in round-bottom flasks containing the previously described medium (27, 28), which included 0.5% (wt/vol) of several carbon sources (glucose, cellobiose, cellulose, Avicel, or xylan [oat-spelt or birchwood]).

Substrates.

Cellobiose, oat spelt, and birchwood xylan were purchased from Sigma. Avicel PH101 and medium-viscosity carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) were obtained from Fluka. o-Nitro-phenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-arabinopyranoside were purchased from Sigma. Cellulose powder (medium length fibers) was obtained from Whatman. Unless otherwise specified, all other chemicals used in this study were reagent grade.

Fractionation of xylan substrate.

To prepare the insoluble fraction of xylan, a suspension of commercial xylan (0.5% [wt/vol] in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.0]) was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged for 20 min at 15,300 × g, and the supernatant, comprising the soluble fraction, was removed. The pellet, comprising the insoluble xylan, was collected and saved.

Preparation of extracellular materials from the growth medium.

Extracellular materials were obtained from the cultures at stationary phase (4 days) by centrifuging the cells at 12,100 × g for 10 min. The supernatants were precipitated with ammonium sulfate at 80% saturation. After centrifugation, the ammonium sulfate precipitate was dialyzed against distilled water (Spectrum Lab, Inc.; 12-kDa cutoff). After the dialyzed extracellular materials were concentrated, the precipitate was dissolved with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

Bacterial protein estimation and preparation of cell-free or cell-associated materials.

The determination of cell mass in xylan-grown cultures was based on a bacterial-protein estimation as described by Bensadoun and Weinstein (4). A 5-ml aliquot was centrifuged for 10 min at 12,100 × g. The pellets were washed with the same volume of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and incubated with 4 ml of sodium deoxycholate (2%) for 20 min. A 1-ml volume of 24% trichloroacetic acid was added to the suspension and centrifuged at 12,100 × g for 10 min. Under these conditions, the cells burst, and cellular proteins were found in the pellet. The protein concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The values obtained were converted to milligrams of bacterial mass protein per milliliter of broth.

Preparation of cellulosome and noncellulosomal materials.

The cellulosome was purified from extracellular materials as described previously (21, 27). The extracellular material was mixed with Avicel, which resulted in binding of the cellulosome complex and some noncellulosomal enzymes to Avicel. After incubation for 1 h at 4°C, the suspension was poured into a column. The column was washed with 3 volumes of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to elute the unattached fractions. These unattached fractions were saved as the noncellulosomal fraction after concentration with Millipore PTGC (10-kDa cutoff). The bound fraction was eluted from the cellulose column with deionized water and concentrated with Millipore PTGC (10-kDa cutoff) before being subjected to gel filtration on a Sephacryl S-200 column (2.6 by 75 cm; Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The high-molecular-weight fractions were collected as the cellulosomal fraction, and then they were concentrated with Millipore PTGC (10-kDa cutoff).

Enzyme assays.

Avicelase, carboxmethyl cellulase (CMCase), and xylanase were assayed by incubating the desired enzyme preparation in the presence of 0.2% (wt/vol) of a substrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 37°C. The incubation was performed for 30 min except in the case of Avicelase (6-h incubation time). The reducing sugar formed was measured by the method of Somogyi-Nelson with glucose or xylose as the standard (36). One unit of each enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme which released 1 μmol of reducing sugar per ml of sample per min under the condition indicated, except with Avicelase (per hour). β-Xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase were estimated by measuring the release of o- or p-nitrophenol from the appropriate substrate (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside or p-nitrophenyl-β-d-arabinopyranoside) (17). The protein concentrations were determined by using the BCA-200 protein assay kit (Pierce).

Electrophoresis and zymogram.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed on 12% acrylamide gels by the procedure developed by Laemmli (18). The samples used for SDS-PAGE were boiled in sample buffer and stored at −20°C. The protein bands were detected by staining the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue R250.

The zymograms for xylanase and CMCase were performed by using a 0.1% (wt/vol) concentration of each substrate incorporated into the polyacrylamide (23). After electrophoresis, the gel was incubated at 37°C for 30 min in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The enzymatic activities were visualized after staining with 0.25% Congo red and destaining with 1 M NaCl (5).

Analysis of reaction products.

Xylan degradation products were qualitatively determined by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on precoated TLC sheets (silica gel; Aldrich) with acetone-ethyl acetate-acetic acid (2:1:1, vol/vol/vol) (23). The plates were visualized by spraying with a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of 0.2% methanolic orcinol and 20% sulfuric acid.

N-terminal sequencing.

For N-terminal amino acid sequencing, cellulosomal fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by electroblotting (Bio-Rad). The protein bands were determined by staining with 0.1% Ponceau red and cut out and were then sequenced by the Edman method by using a model 477 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

Effect of carbon source on the extracellular enzyme activity of C. cellulovorans.

C. cellulovorans was grown on several carbon sources to determine their effect on the expression of xylanases. The culture supernatants were harvested after 4 days, and the extracellular materials were examined for cellulose and hemicellulose degradation activities (Table 1). The CMCase and Avicelase activities were observed to be similar irregardless of the carbon source. When xylan (oat spelt and birchwood) was used as the sole carbon source, the xylanase activity was significantly increased compared to that of glucose-, cellobiose-, cellulose-, and Avicel-grown cultures. The xylanase activity from cells grown on birchwood xylan was especially higher than that from cells grown on oat spelt. Therefore, we used birchwood xylan as the xylan substrate in the following experiments.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of enzyme activities in culture supernatants after growth in several carbon sources

| Carbon source | Activity in the supernatants (U/mg of protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMCase | Avicelasea | Xylanase (oat spelt) | Xylanase (birchwood) | |

| Glucose | 0.39 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Cellobiose | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Cellulose | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Avicel | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Xylan (oat spelt) | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| Xylan (birchwood) | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.81 |

The Avicelase activity is based on the activity per hour.

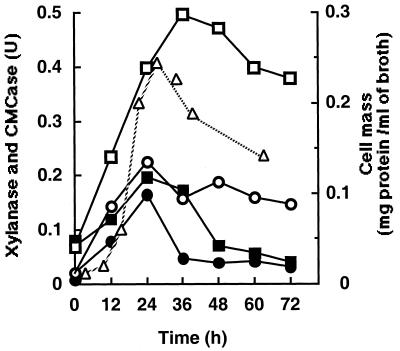

Distribution of xylanase activity during growth of C. cellulovorans.

In order to determine the distribution of xylanase during growth on xylan, the xylanase and CMCase activities associated with the cell and in the growth medium were measured (Fig.1). At the end of the growth phase, 80 to 89% of the total xylanase activity was detected in the extracellular fraction. The maximal xylanase activity detected in the extracellular fraction was 0.5 μmol of xylose per ml of broth per min, and xylanase production correlated reasonably well with the cell growth phase. On the other hand, xylanase activity in the cell-associated fraction was low compared to the supernatant fraction. However, at early logarithmic growth phase, the cell-associated activity remained comparatively high (0.19 μmol of xylose per ml of broth per min). CMCase activity could be detected at the same levels in both the cell-free and the pellet-associated fractions during the early logarithmic growth phase. The maximum CMCase activity was 0.23 and 0.17 μmol of glucose per ml of broth per min for cell-free and pellet-associated fractions, respectively. It appeared that enzymes related to the cellulosome were attached to the cell during the early logarithmic growth phase. The results also showed that much more of the xylanase activity was in the growth medium at all times.

FIG. 1.

Activity of xylanase and CMCase in xylan (birchwood)-grown cultures. The supernatant and the pellet were assayed for CMCase and xylanase as cell-free and cell-attached fractions, respectively. The activities are indicated as units per milliliter of culture broth. Cell mass is indicated as milligrams of total protein per milliliter of culture broth. Symbols: □, cell-free xylanase activity; ■, cell-attached xylanase activity; ○, cell-free CMCase activity; ●, cell-attached CMCase activity; ▵, cell mass.

Fractionation of extracellular xylanase activity.

To determine the distribution of the xylanase activity of C. cellulovorans, the extracellular materials of xylan-grown cells were fractionated into cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions either according to size or according to their interaction with cellulose by previously described methods (21, 27). The culture supernatant was harvested after 48 h of growth and concentrated by 80% ammonium sulfate saturation. After the concentrated materials were mixed with cellulose, two fractions were obtained. The fraction that did not bind to cellulose was collected as the noncellulosomal fraction. The fraction that adsorbed to cellulose was eluted from the cellulose and subjected to gel filtration. The high-molecular-weight fraction obtained from gel filtration was pooled as the cellulosomal fraction.

Under these conditions, about 65 to 77% of the total xylanase activity was found to be in the cellulosome fraction. This purification procedure led to the recovery of 2.9 to 3.6 mg of cellulosomal protein per liter of culture with a specific CMCase activity of 4.0 U/mg of protein and a specific xylanase activity of 11.9 U/mg of protein. The noncellulosomal fraction contained 28 mg of protein per liter of culture, with specific CMCase and xylanase activities of 0.8 and 3.7 U/mg of protein, respectively.

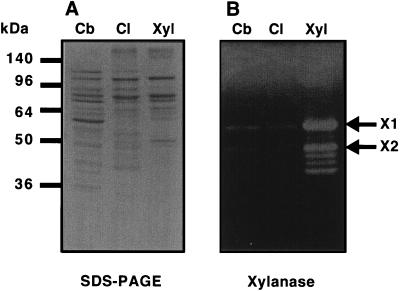

Comparative polypeptide and zymogram patterns of cellulosomal and noncellulosomal xylanase.

When subjected to SDS-PAGE, the cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions were found to yield significantly different polypeptide patterns. The cellulosomal polypeptides ranged from 40 to 180 kDa (Fig. 2A). Among these polypeptides, the 180-, 110-, 75-, and 50-kDa proteins were the most abundant. To identify these proteins, their amino termini were sequenced. The sequences of the 180-, 110-, and 75-kDa polypeptides were identical to those of the major cellulosomal subunits, i.e., scaffolding protein CbpA (ATSSMSV) (26), endoglucanase EngE (AEANXTTKG) (31), and exoglucanase ExgS (APVVPNN) (20), respectively. On the other hand, the polypeptides in the noncellulosomal fraction ranged from 25 to 130 kDa (Fig. 2B). The amounts of low-molecular-weight proteins were increased relative to that found for the low-molecular-weight cellulosomal proteins. In addition, the 125-, 85-, and 50-kDa polypeptides were more abundant in the noncellulosomal fraction compared to that found in the cellulosomal fraction. These results showed that the noncellulosomal pattern of proteins was quite different from that of the cellulosomal fraction.

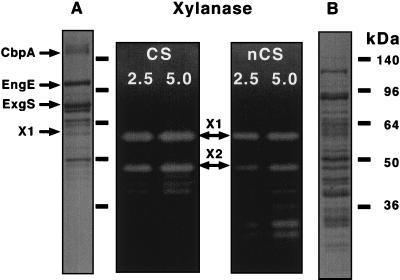

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE and xylanase activity profile of cellulosome and noncellulosomal components. The cellulosomal (lanes A and CS) and noncellulosomal (lanes B and nCS) fractions were applied to SDS–12% PAGE gels with or without 0.1% xylan. After electrophoresis, the gels were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (lanes A and B) or examined for xylanase activity by using Congo red. The protein amount (2.5 or 5 μg,) of each fraction (CS and nCS) applied to the gels is indicated. Molecular mass is indicated in kilodaltons on the right.

To determine the distribution of xylanase activity in the cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions, we performed zymograms with xylan. In the cellulosomal fraction, two major xylanase activities could be detected, corresponding to molecular weights of 57,000 (X1) and 47,000 (X2) (Fig. 2). In addition to these major subunits, two to three minor activities could also be discerned, corresponding to molecular masses of from 42 to 39 kDa. In the noncellulosomal fraction, several major xylanases were observed, corresponding to molecular masses of 57, 47, 30, and 28 kDa. In addition, minor xylanase activities at several low molecular weights ranging from 42,000 to 33,000 were also discerned. Xylanase activity corresponding to the 30- and 28-kDa polypeptides was also comparatively high.

Regarding enzymatic activities with X1 and X2, these activities interestingly were observed in both the cellulosomal and the noncellulosomal fractions. Their presence in cellulosome suggests that X1 and X2 probably carry dockerin domains which are required by enzymatic subunits to interact with the cohesins present in scaffolding protein CbpA (7, 30).

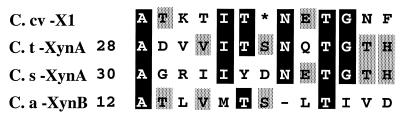

The migration of one (X1) of these activities also coincided with the polypeptide which is a 57-kDa polypeptide in the cellulosomal fraction (Fig. 2). To characterize this polypeptide exhibiting a major xylanase activity, we also sequenced the amino terminus of this protein and obtained the sequence ATKTITXNETGNF. When the amino acid sequence obtained was compared with that of other xylanases from clostridia (15, 24, 37), it was similar to xylanases classified in Family-11 of the glycosyl hydrolases, such as C. thermocellum XynA, C. stercorarium XynA, and C. acetobutylicum XynA (Fig. 3). It is known that typical Family-11 enzymes have a narrow substrate specificity and a high activity with xylooligosaccharides (15, 24). We were not successful in determining the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the polypeptide corresponding to X2, since it occurred in very low quantities. In previous work, we have cloned the genes for C. cellulovorans EngB and EngD, which have not only CMCase activity but also xylanase activity (9, 10, 14). Although the deduced molecular masses for EngB (48 kDa) and EngD (50 kDa) are close to that of X2, X2 has no CMCase activity (data not shown). Both X1 and X2, in zymogram studies, did not show any activity on CMC and were active only on xylan. Therefore, it is likely that X1 and X2 are novel xylanases for C. cellulovorans.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of N-terminal amino acid sequence of the Family-11 xylanases C. thermocellum (C.t-XynA), C. stercorarium (C.s-XynA), and C. acetobutylicum (C.a-XynB) with the N terminus of C. cellulovorans xylanase X1 (C.cv-X1). Residues identical in at least three of the four sequences are written in white letters on a black background. Similar residues are displayed with a shaded background. Numbers at the start of the respective lines refer to amino acid residues; the sequences are numbered from Met-1 of the peptide. The asterisk in C.cv-X1 indicates an unclear amino acid. A gap in C.a-XynB is indicated by a dash to improve the alignment.

Characterization of the products of xylanases from cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions.

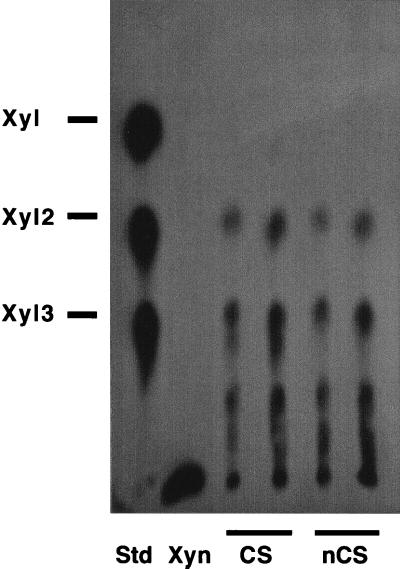

The degradation products of xylan by the cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions were analyzed by TLC. In the cellulosomal fraction, the major products of the reaction included xylobiose as the main reaction product, xylotriose, and various unidentified oligosaccharides (Fig. 4). Furthermore, when the incubation was continued for 4 days, very low levels of xylose were also detected, and most of the xylotriose was converted to xylobiose (data not shown). In the noncellulosomal fraction, the major products and pattern of hydrolysis products were similar to those of the cellulosomal fraction, with xylobiose being the predominant product. In both cases, almost complete depolymerization of the xylan substrate was observed.

FIG. 4.

TLC of reaction products of xylanase activity in C. cellulovorans. Cellulosomal (CS) and noncellulosomal (nCS) fractions were mixed with 0.5% xylan and incubated for 2 days at 37°C, and the samples of each were applied to TLC plates. Xyn, reaction mixtures without enzymes. Xylooligomers xylose (Xyl), xylobiose (Xyl2), and xylotriose (Xyl3) were used as standards (Std).

It is known that xylan is a highly branched molecule. The common substitutes found on the β-1,4-linked d-xylopyranosyl residues are acetyl, arabinosyl, and glucuronosyl residues, which are hydrolyzed by several xylanolytic enzymes (34). We also determined the distribution of β-xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase in cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions by using o-nitrophenyl-β-xylopyranoside or p-nitrophenyl-α-arabinopyranoside as the substrate. While both β-xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase activities could be detected in the cellulosomal and the noncellulosomal fractions (Table 2), the observed β-xylosidase activity in both fractions was very low.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic characters of cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions in xylan-grown cultures

| Enzyme | Activity of each fraction (U/mg of protein)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Cellulosomal | Noncellulosomal | |

| CMCase | 4.01 | 0.87 |

| Xylanase | 11.95 | 3.80 |

| β-Xylosidase | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| α-Arabinofuranosidase | 0.03 | 0.18 |

Interestingly, α-arabinofuranosidase activity occurs at a relatively high level in the noncellulosomal fraction. Furthermore, this α-arabinofuranosidase activity is strongly influenced by the carbon source in the growth medium. When C. cellulovorans was grown on cellobiose or cellulose as the carbon source, the α-arabinofuranosidase activity could not be detected in the culture supernatant (data not shown). These results suggest that the α-arabinofuranosidase may be induced depending on the carbon source in the growth medium and that both β-xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase contribute to xylan depolymerization by C. cellulovorans.

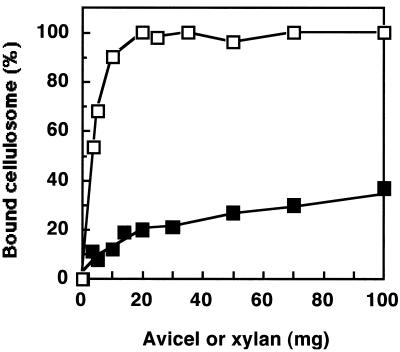

Interaction of cellulosome with xylan.

It is known that the cellulosome from C. cellulovorans is responsible for the adhesion of the bacterium to the insoluble cellulose substrate (7, 12). To determine whether the cellulosomes prepared from xylan-grown cells bind to xylan, we measured interaction of cellulosomes with insoluble xylan. A positive-control experiment in which cellulose was used as adsorbent was performed. About 90% of the cellulosome was adsorbed to relatively low amounts (10 mg) of cellulose (Fig. 5). In contrast, the adsorption of cellulosomes to xylan remained very weak. About 60 to 70% of the activity remained in the unbound state, even when large amounts (100 mg) of xylan were used. These results are similar to xylan adsorption properties of cellulosomes from other cellulolytic clostridia (22, 23).

FIG. 5.

Adsorption of cellulosome to Avicel or insoluble xylan. The capacity of a constant amount (40 μg/ml) of cellulosome to bind to various amounts of crystalline cellulose or insoluble xylan (2.5 to 100 mg per tube) was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as percentages of bound xylanase activity. Symbols: □, Avicel; ■, insoluble xylan.

Regulation of xylanotic activity in C. cellulovorans.

We have observed changes in xylan degradation activity when xylan was used as the carbon source for growth (Table 1). In order to study this change in xylanase activity, cellulosome fractions derived from cellobiose-, cellulose-, and xylan-grown cultures were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. When each cellulosomal fraction derived from growth in difference media was subjected to SDS-PAGE, quite different subunit patterns were observed (Fig. 6A). In cellulosomes derived from cellobiose-grown cells, the amount of the scaffolding protein CbpA decreased relative to that from cellulosomes from cellulose- and xylan-grown cells. Although the polypeptide patterns of cellulose- and xylan-grown cells were similar for some peptides, e.g., EngE and ExgS, the low-molecular-weight peptides in the cellulose-grown cells increased compared with that of xylan-grown cells.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of SDS-PAGE pattern (A) and xylanase activity (B) of the cellulosomal fraction derived from cellobiose-, cellulose-, and xylan-grown cells. (A) The cellulosomal samples were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and applied to SDS–12% PAGE gels. (B) After electrophoresis, the gels were examined for xylanase activity by the Congo red procedure. Each sample contained 5 μg of cellulosomal protein. Lanes: Cb, cellobiose-grown cells; Cl, cellulose-grown cells; Xyl, xylan-grown cells. Molecular mass is indicated in kilodaltons on the left. X1 and X2, xylanase 1 and xylanase 2, respectively.

Furthermore, to determine whether there was a difference in the distribution pattern of xylanase activity between these cellulosomal fractions, we subjected the cellulosomal subunits to zymograms. Although the distribution pattern of xylanase activity derived from cellobiose- and cellulose-grown cells was similar to that of xylan-grown cells and activities corresponding to X1 and X2 (Fig. 6B) were detected, xylanase activities derived from xylan-grown cells were quite higher than that from cellobiose- and cellulose-grown cells. The proportion of these xylanase activities from the zymogram also were in good agreement with the activities in the culture broth (Table 1). In addition, when the 57- and 47-kDa proteins derived from xylan-grown cells were compared by SDS-PAGE with those from cellobiose- and cellulose-grown cells, these proteins were also found to be present in greater amounts (Fig. 6A). These results strongly indicated that C. cellulovorans regulates not only xylanolytic activities but also components in the cellulosome depending on the growth substrate.

DISCUSSION

C. cellulovorans utilizes not only cellulose but also xylan, pectin, and several other carbon sources. Among the available carbon sources, xylan is one of the predominant hemicelluloses in plant cell walls. In this study, we characterized the xylan degradation enzymes of C. cellulovorans when it was cultured with xylan as the growth substrate. The extracellular xylanase activity is significantly increased, compared with that found in cellobiose-, cellulose-, and Avicel-grown culture supernatants. These xylanase activities were found primarily in the cell-free supernatant fraction but also in the cellulosome fraction. These results are very similar to that found in C. thermocellum (23) and C. cellulolyticum (22). Xylanase activity in C. cellulovorans was mainly associated with two major polypeptides (X1 and X2) in the cellulosomal fraction. These results suggest the xylanolytic polypeptides probably carry dockerin domains since all cellulosomal enzymatic subunits require dockerins to bind to cohesins present in scaffolding proteins such as CbpA (2, 7, 30). However, in these experiments, these xylanolytic polypeptides were also found in the noncellulosomal fraction. Furthermore, when the cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions were subjected to a zymogram with CMC, most of the CMCase activity was associated with bands corresponding to EngE and ExgS. These results suggest that cellulosomal subunits that are expressed more abundantly than the xylanase subunits may compete for cohesin domains, thus preventing the binding of all the xylanase that is produced. Thus, some of the xylanase is released into the culture medium. Since the quantity of EngE and ExgS is significantly higher than that of X1 and X2 as visualized by SDS-PAGE, this may be the case. Another possibility is that the interaction between the dockerin domain of the xylanases and the cohesin domains in CbpA is weaker than that of other enzymatic subunits. In any case, the lack of strong interaction between xylanases and CbpA could explain the presence of large amounts of xylanase in the growth medium.

The presence of xylanase activities of low molecular weights (30,000 and 28,000) on zymograms can be interpreted as products of xylanase genes coding for these smaller xylanases. However, we found that during 2 weeks of storage of the X1 and X2 that their activities decreased and there was an increase in the 30- and 28-kDa proteins. Therefore, it is likely that these two smaller activities are the result of partial proteolysis of X1 and/or X2.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the X1 had high homology for xylanases classified in family 11 of glycosyl hydrolases. Several xylanases have been cloned and expressed in E. coli. On the basis of amino acid sequence similarity, xylanases have been grouped into families 10 and 11 of the glycosyl hydrolases (16). Family 11 enzymes such as C. themocellum XynA and XynB and C. stercorarium XynA have a narrow substrate specificity and a high activity with xylotetraose and larger xylooligosaccharides but less activity with xylotriose (15, 24). Therefore, xylan hydrolysis activity of X1 seems to contribute mainly to the depolymerization of β-1,4-linked chains in xylan. On the other hand, the property of X2 remains unknown, since preliminary N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis did not reveal its basic properties.

We also detected β-xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase activities in the cellulosomal and noncellulosomal fractions when C. cellulovorans was cultured with xylan. However, the β-xylosidase activity in both fractions were very low. In C. thermocellum, β-xylosidase was observed exclusively in the cell-associated fraction (23). It was also reported that β-xylosidase was purified from broken cell extracts of C. cellulolyticum (25). The cellulosomes of C. thermocellum and C. cellulolyticum are in essence cell-surface components (1, 3, 11). In C. thermocellum in the early logarithmic phase of growth the cellulosome is intimately associated with the cell but becomes dissociated from the cell during the late-exponential-growth phase. It is unclear whether β-xylosidase is associated with intracellular or cell-surface components, including the cellulosome in C. cellulovorans, because we did not measure cell-associated β-xylosidase activity in this experiment. However, β-xylosidase in C. cellulovorans is associated probably with the cell or the surface, since the activity in culture supernatants specifically increased when the culture time was extended from 2 to 7 days (data not shown). The increase in activity appears to be caused by bacteriolysis or dissociation of the cellulosomes from the cell surface.

Interestingly, in C. cellulovorans α-arabinofuranosidase activity was found exclusively in the noncellulosomal fraction. In nature, xylan in woody tissue is known to be highly branched with acetyl, arabinosyl, and glucuronosyl residues (34). Complete enzymatic hydrolysis for xylan, therefore, requires the cooperative action of β-1,4-xylanase, and a series of enzymes such as α-arabinofuranosidase and xylan acetylesterase that cleave side chain groups. It is also interesting that the observed α-arabinofuranosidase probably acts as free subunits in culture broth and is not associated with the cellulosome. The debranching enzymes may have to be mobile to work with xylanase for the effective degradation of xylan. In fact, synergism between an α-arabinofuranosidase and a β-1,4-xylanase from Ruminococcus albus has been reported (13). Therefore, it appears that the α-arabinofuranosidase plays an important role for effective degradation of highly branched xylan polymers in C. cellulovorans. So far, many xylanase genes have been cloned from several different microorganisms, including thermophilic clostridia. In contrast, little is known about the β-xylosidase and α-arabinofuranosidase genes. Therefore, it is important to obtain more information about the genetics and regulation of both enzymes.

In this study, we have also shown that C. cellulovorans is not only able to regulate the expression of xylanase activity but that the production of cellulosomal components may be altered depending on the carbon source, e.g., cellobiose, cellulose, and xylan. When the xylanase activity for the cellulosomal fraction was compared with zymograms, the relative proportion of xylanase activity was quite different depending on the growth substrate. When cells were grown on xylan, two bands of xylanase activity corresponding to X1 and X2 were increased significantly, compared with the fractions from cellobiose- and cellulose-grown cultures. These results clearly indicated that C. cellulovorans was able to regulate the expression of xylanases. On the other hand, the CMCase activity for these cellulosomal fractions did not show a large difference with the variety of the carbon sources used (data not shown). These results suggest that the major cellulosomal subunits, EngE and ExgS, are constitutively expressed in C. cellulovorans. These regulatory effects are very interesting, and we need to study the xylanase genes for better understanding of their structure, function, and regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The research was supported in part by grant DE-DDF03-92ER20069 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer E A, Setter E, Lamed R. Organization and distribution of the cellulosome in Clostridium thermocellum. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:552–559. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.2.552-559.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayer, E. A., L. J. W. Shimon, Y. Shoham, and R. Lamed. 1998. Cellulosome-structure and ultrastructure. 124:221–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Belaich J-P, Tardif C, Belaich A, Gaudin A. The cellulolytic system of Clostridium cellulolyticum. J Biotechnol. 1997;57:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(97)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensadoun A, Weinstein D. Assay of proteins in the presence of interfering materials. Anal Biochem. 1976;70:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(76)80064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bequin P. Detection of cellulase activity in polyacrylamide gels using Congo red-stained agar replicas. Anal Biochem. 1983;131:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biely P. Microbial xylanolytic systems. Trends Biotechnol. 1985;3:286–290. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doi R H, Park J-S, Liu C-C, Malburg L M, Tamaru Y, Ichi-ishi A, Ibrahim A. Cellulosome and noncellulosomal cellulase of Clostridium cellulovorans. Extremophiles. 1998;2:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s007920050042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi R H, Tamaru Y. The Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome: an enzyme complex with plant cell wall degrading activity. Chem Rec. 2001;1:24–32. doi: 10.1002/1528-0691(2001)1:1<24::AID-TCR5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foong F C, Doi R H. Characterization and comparison of Clostridium cellulovorans endoglucanases-xylanases EngB and EngD hyperexpressed in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1403–1409. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1403-1409.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foong F C, Hamamoto T, Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Nucleotide sequence and characteristics of endoglucanase gene engB from Clostridium cellulovorans. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1729–1736. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-7-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujino T, Beguin P, Aubert J-P. Organization of a Clostridium thermocellum gene cluster encoding the cellulosomal scaffolding protein CipA and a protein possibly involved in attachment of the cellulosome to the cell surface. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1891–1899. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1891-1899.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Mutation analysis of the cellulose-binding domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7328–7334. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.23.7328-7334.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greve L C, Labavitch J M, Hungate R E. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase from Ruminococcus albus 8: purification and possible role in hydrolysis of alfalfa cell wall. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:1135–1140. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.5.1135-1140.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamamoto T, Shoseyov O, Foong F, Doi R H. A Clostridium cellulovorans gene, engD, codes for both endo-β-1,4-glucanase and cellobiosidase activities. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;72:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi H, Takehara M, Hattori T, Kimura T, Karita S, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Nucleotide sequences of two contiguous and highly homologous xylanase genes xynA and xynB and characterization of XynA from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:348–357. doi: 10.1007/s002530051401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henrissat B, Bairroch A. Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem J. 1996;316:695–696. doi: 10.1042/bj3160695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lachke A H. 1,4-β-d-Xylan xylohydrolase of Sclerotium rolfsii. Methods Enzymol. 1988;160:679–684. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;277:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leschine S B. Cellulose degradation in anaerobic environments. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:399–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C-C, Doi R H. Properties of exgS, a gene for a major subunit of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes. Gene. 1998;211:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matano Y, Park J-S, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Cellulose promotes extracellular assembly of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosomes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6952–6956. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6952-6956.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohand-Oussaid O, Payot S, Guedon E, Gelhaye E, Youyou A, Petitdemange H. The extracellular xylan degradative system in Clostridium cellulolyticum cultivated on xylan: evidence for cell-free cellulosome production. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4035–4040. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.4035-4040.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morag E, Bayer E A, Lamed R. Relationship of cellulosomal and noncellulosomal xylanases of Clostridium thermocellum to cellulose-degradating enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6098–6105. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6098-6105.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakka K, Kojima Y, Kondo T, Karita S, Ohmiya K, Shimada K. Nucleotide sequence of the Clostridium stercorarium xynA gene encoding xylanase A: identification of catalytic and cellulose binding domains. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:273–277. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxena S, Fierobe H-P, Gaudin C, Guerlesquin F, Belaich J-P. Biochemical properties of a β-xylosidase from Clostridium cellulolyticum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3509–3512. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3509-3512.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoseyov O, Takagi M M, Goldstein M A, Doi R H. Primary sequence analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A (CbpA) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3483–3487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoseyov O, Doi R H. Essential 170-kDa subunit for degradation of crystalline cellulose of Clostridium cellulovorans cellulase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2192–2195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sleat R, Mah RA, Robinson R. Isolation and characterization of an anaerobic, cellulolytic bacterium, Clostridium cellulovorans sp. nov. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:88–93. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.88-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taiz L, Zeiger E. Plant physiology. Redwood City, Calif: The Benjamin Cummings Publishing Company, Inc., Publishers; 1991. Plant and cell architecture; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takagi M, Hashida S, Goldstain M A, Doi R H. The hydrophobic repeated domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein (CbpA) has specific interactions with endoglucanases. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7119–7122. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.7119-7122.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamaru Y, Doi R H. Three surface layer homology domains at the N terminus of the Clostridium cellulovorans major cellulosomal subunit EngE. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3270–3276. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3270-3276.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamaru Y, Doi R H. The engL gene cluster of Clostridium cellulovorans contains a gene for cellulosomal ManA. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:244–247. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.244-247.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamaru Y, Karita S, Ibrahim A, Chan H, Doi R H. A large gene cluster for the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5906–5910. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.20.5906-5910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomson J A. Molecular biology of xylan degradation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;104:65–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb05864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timmell T E. Recent progress in the chemistry of wood hemicelluloses. Wood Sci Technol. 1967;1:45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood W A, Bhat K M. Methods for measuring cellulose activities. Methods Enzymol. 1988;160:87–112. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zappe H, Jones WA, Woods DR. Nucleotide sequence of a Clostridium acetobutylicum P262 xylanase gene (XynB) Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:2179–2179. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.8.2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]