Abstract

Background

Small bowel ultrasound has very good diagnostic accuracy for disease extent, presence and activity in Crohn’s Disease, is well tolerated by patients and is cheaper when compared with MRI. However, uptake of ultrasound in the UK is limited.

Methods

An online survey to assess the current usage of ultrasound throughout the UK was undertaken by BSG IBD group members between 9/06/2021- 25/06/2021. Responses were anonymous.

Results

103 responses were included in the data analysis. Responses came from 66 different NHS trusts from 14 different regions of the UK. All respondents reported that they currently have an MRI service for Crohn’s disease, whereas only 31 had an ultrasound service. Average time for results to be reported for MRI scans was reported as between 4– and 6 weeks, with a range of 2 days to 28 weeks. The average time for an ultrasound to be reported was stated as 1–4 weeks, with a range of 0–8 weeks. There was disparity between the reported confidence of clinicians making clinical decisions when using ultrasound compared to MRI. Of those respondents who did not have access to an ultrasound service, 72 stated that they would be interested in developing an ultrasound service.

Conclusion

There is an appetite for the uptake of ultrasound in the UK for assessment of Crohn’s disease, however, there remains a significant number of UK centres with little or no access to an ultrasound service. Further research is necessary to understand why this is the case.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn's disease, gastrointestinal ultrasound

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Ultrasound is used widely in central Europe and Canada. Despite ultrasound being a quicker, cheaper and more preferable test for patients, the uptake of ultrasound use in the UK is still limited. The METRIC Study has shown that ultrasound has comparable sensitivity and specificity to magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) when detecting presence and extent of small bowel Crohn’s disease.

What this study adds

Nationally there are longer waiting times for MRE and ultrasounds assessments. Gastroenterologists report that they are more confident in using MRE reports to make clinical decisions than ultrasound reports, it is not yet clear why this is the case. The survey has shown that there are some centres in the UK that are using ultrasound as part of their inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) assessment; however, there still remain many UK National Health Service (NHS) centres that do not use ultrasound but have indicated that they would wish to in the future.

Key messages.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

This survey is part of a programme of work being led by the National Institute for Health Research Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre. This programme of work will investigate aspects of existing ultrasound use in the UK, training needs of the IBD team, confidence in clinical decision-making of the IBD team using ultrasound, cost-effectiveness of an ultrasound pathway in IBD care and stakeholder perceptions of the implementation of ultrasound in the NHS. Mixed methods data will be collected and used to create an implementation package to support the implementation of ultrasound nationally for the care of patients living with IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to two conditions: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis, typically characterised by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Disease distribution in CD varies with up to 70% of patients having small bowel involvement.1

The incidence and prevalence of CD in Europe ranges from 0.5 to 10.6 cases per 100 000 person-years and from 1.522 to 21 312 cases per 100 000 persons, respetively.2 In the UK, it is estimated that there are 300 000 people affected by IBD, one of the highest worldwide.3

The mean cost per patient-year during follow-up has been reported as £2971 (median £602 (180–2948)) for patients with CD, with an overall annual cost to the National Health Service (NHS) of up to £470 million.4 During the first 5 years following IBD diagnosis 50%–75% of the budget is attributed to the use of biologic therapy.4

To ensure optimal long-term clinical outcomes, current recommendations based on the selecting therapeutic targets in IBD (STRIDE-II)5 suggest using objective measures as treatment targets, rather than symptom resolution. A wide array of biological therapies are employed in treating IBD and objectively assessing treatment response has significantly increased the projected IBD healthcare burden for the next decade.6 To ensure cost-effective IBD practice, complex and expensive pharmacological interventions should be targeted at patients most likely to benefit.7

Cross-sectional imaging is used to diagnose and monitor disease activity in small bowel CD (SBCD).8 Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) is often employed as a first modality in the UK for assessment and monitoring of SBCD.8 Waiting times for an NHS MRE may be up to 4 weeks or in some instances longer and have increased due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiological reporting is then undertaken at a later date and may also add to delays. There is still a clinical need to find quicker, more tolerable and cheaper alternatives for monitoring patients with IBD.

Small bowel (enteric) ultrasound is an alternative to MRE and has the potential to significantly reduce waiting times, speed up clinical decision-making and improve patient experience and outcomes.9 Ultrasound is widely used for assessing and monitoring IBD internationally, and the METRIC trial has demonstrated its relative diagnostic accuracy in comparison to MRE.10 11

The National Institute for Health Research-funded METRIC trial is the largest comparative diagnostic accuracy trial of MRE and ultrasound in CD.10 The study reported that sensitivity for detecting small bowel disease was 97% and 92% for MRE and ultrasound, respectively. Specificity was 96% for MRE and 84% for ultrasound.10 These findings were concordant in both new diagnosis and suspected relapse.10 11

NHS tariff reports from 2021/2022 detail the cost for an MRE procedure with intravenous contrast to be £162, with a reporting cost of £22. In comparison the cost of ultrasound is £51, inclusive of reporting, hence making it a less costly and potentially more cost-effective alternative. There is a large clinical need to correctly identify responders and non-responders to therapy in a timely, cost-effective and efficient manner.7 12 However, ultrasound is not commonly used in the NHS, unlike in Central Europe and Canada.13 14 Many authors report this is likely down to lack of available training,9 15–17 although questions over high interobserver variation and suboptimal accuracy have dogged ultrasound for many years. The actual barriers to adoption of ultrasound in the NHS UK are to date speculative and remain largely unknown.

Methods

We designed and conducted an online survey to assess the current usage of ultrasound throughout the UK (table 1). The survey was undertaken by the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) IBD group members between 9 June 2021 and 25 June 2021. The BSG IBD group consists of consultant and trainee gastroenterologists with a special interest in IBD and IBD specialist nurses. There are 1410 members of the BSG IBD group. The survey was sent to all members on 9 and 22 June 2021, the survey was sent twice as the deadline for responses was extended by a week. Responses were anonymous, respondents were able to skip questions if they were unsure of the answers or if the question was not relevant to them (ie, they do not currently use ultrasound). The survey was accessible via online link, no reminders were sent.

Table 1.

Comparison of imaging modalities when assessing small bowel Crohn’s disease

| Ultrasound | MRE | |

| Sensitivity10 | 92% | 97% |

| Specificity10 | 84% | 96% |

| Preparation | None | Oral and intravenous contrast |

| Average duration of test | 20 min | 45 min |

| Average waiting times (from referral to report) | 1–4 weeks (range 0–8 weeks) |

4–6 weeks (range 2 days to 28 weeks) |

| Estimated NHS cost (20/21 NHS tariff) | £51.00 | £162+£22 reporting costs |

MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; NHS, National Health Service.

The questionnaire comprised of 14 questions. Questions were focused on the respondents experiences of MRE and ultrasound use in relation to the clinical IBD care they deliver. We asked respondents to report only on plain ultrasound examinations. We did not collect data regarding other forms of ultrasound examination such as elastography or Doppler. We collected data relating to the regions of the UK where respondents work clinically and their opinions about whether they would like to use ultrasound for monitoring of IBD in the future if they did not already do so.

Results

There were 106 respondents, this is a response rate of 7.5%. There were two incomplete forms, so two respondents were removed, and one international respondent was also removed given the UK focus of the survey. Overall, 103 responses were included in the data analysis.

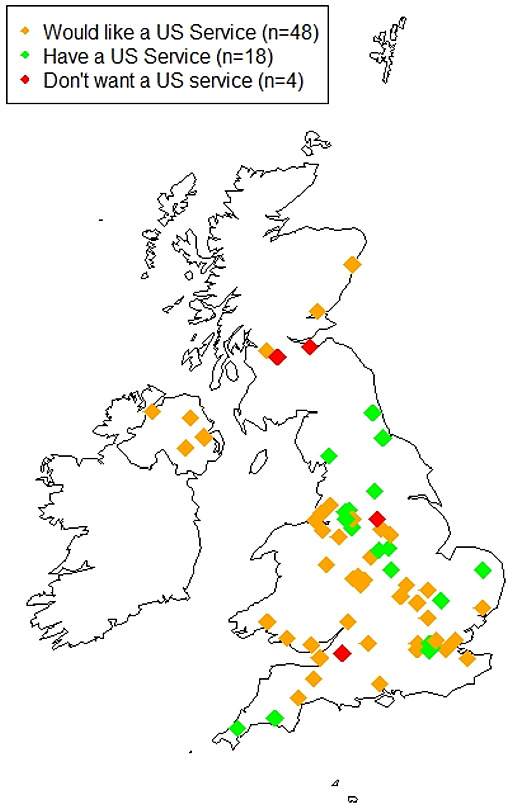

Responses came from 14 different regions of the UK, from 66 individual NHS trusts. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the responding centres, showing those that currently use ultrasound, those that would like to in the future and those that do not.

Figure 1.

Distribution of NHS centres in the UK that responded to the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) survey on the use of small bowel ultrasound (SBUS). NHS, National Health Service.

Overall, all respondents reported that they currently have an MRI service for CD, whereas only 31 had access to ultrasound service. Of those respondents who did not have access to an ultrasound service, 72 stated that they would be interested in developing an ultrasound service.

Overall, 55 respondents reported that they always use MRI when clinically appropriate, 39 reported that they ‘usually’ use MRI, 8 stated that they sometimes use MRI and 1 person stated that they never use MRI. Overall, 46 respondents reported that they never use ultrasound, 12 rarely use it, 22 sometimes use it with only 5 respondents usually using it and 6 always use it.

The number of MRIs performed per month was reported as an average of 15, with a range of 3–75. The average number of ultrasounds undertaken was reported as eight per month, with a range of 0–50. Average time from referral for results to be reported for MRI scans was reported as between 4 and 6 weeks, with a range of 2 days to 28 weeks. The average time for an ultrasound to be reported was stated as 1–4 weeks, with a range of 0–8 weeks.

Overall, 30 respondents reported that they had access to both MRE and ultrasound. Not all respondents completed all sections of the survey questionnaire. Nine different sites were reported to have access to both MRE and ultrasound, with five of those being university hospitals trusts and four NHS foundation trusts. Overall, 21 respondents did not complete data relating to which NHS trust they were currently employed by. Overall, 25 respondents with access to both modalities submitted data relating to waiting times; in these centres, the average waiting time from referral to report was reported as 4.6 weeks for MRE and 3.4 weeks for ultrasound.

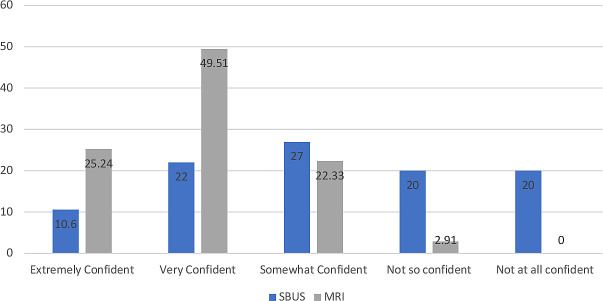

26 respondents were ‘extremely confident’ when using MRI data to make clinical decisions, 5 were ‘very confident’ were somewhat confident and 3 were not so confident. Only 6 respondents stated they would be extremely confident in using ultrasound to make clinical decisions, 17 stated they would be very confident, 20 stated they were somewhat confident, 15 stated they were not so confident and 15 stated they were not at all confident (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Confidence in clinical decision-making when using Small Bowel US (SBUS) and MRE assessment (%). MRE, magnetic resonance enterography.

Discussion

MRE is the first-line imaging modality used to accurately stage small bowel disease location, complexity and activity in newly diagnosed CD.5 10 MRE is also most commonly used to measure disease response to biological therapies. However, once disease location and phenotype are established, in many patients, there is an equipoise between MRE and small bowel ultrasound in subsequent disease follow-up and monitoring. SBUS has been shown to be equally accurate for evaluating enteric disease,18–23 cheaper, quicker, better tolerated and, most importantly, preferred by patients.10 24–27 Despite this, US is not widely implemented for CD in the UK, for reasons we do not fully understand.

The treat-to-target paradigm present in IBD management guidelines is similar in other chronic diseases.28–31 Management strategies in CD reflect a step-up paradigm, where patients clinical symptoms in conjunction with markers of inflammation tend to guide investigation or medical intervention.32 33 Mucosal healing, defined by the absence of ulcerations, is recommended as the therapeutic goal in clinical practice.5 8 34

The equipment required is readily available in most hospitals. ultrasound could be a robust alternative to more invasive and expensive imaging techniques. Besides being quick, well tolerated, relatively inexpensive and readily available, ultrasound is reported and interpreted at the time of scanning and allows for early clinical decision-making in routine IBD care.9 35 Importantly, the METRIC10 Study found no major difference between MRE and ultrasound in terms of therapeutic decision-making, indicating that the differences in accuracy between the two tests do not translate to differences in patient management. Both tests had a similar level of concordance compared with the reference standard in terms of therapeutic decisions (77% for MRE and 78% for ultrasound). This substudy on decision-making, although well designed, was a paper-based exercise with small numbers; further evidence is required to ensure these results reflect real-world practice.

The results from the METRIC20 Study were used to underpin a cost-effectiveness analysis showing that ultrasound was more cost-effective than MRE in the management of suspected relapse; it was estimated that ultrasound saves the NHS an average of £299 per patient, with a negligible –0.0001 (–0.013 to 0.011) impact on QALYs. There is scarce empirical evidence presenting comprehensive data relating to cost or cost-effectiveness of ultrasound.9 In the METRIC Study, ultrasound was considered highly acceptable by patients when compared with MRE.27 Ultrasound is often seen as having limited clinical utility due to operator dependence.35 However, every diagnostic technique, including endoscopy, has a degree of subjectivity and operator dependence and this criticism is perhaps more reflective of a previous lack of identifiable international performance and training standards.35 The training needs for gastroenterologists are similar to those of radiologists as set out in the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) ECCO-ESGAR guidelines,12 this can be time consuming, even when supported by abdominal radiology specialists and in partnership with radiology departments.9 16 35 There is no current literature relating to any other IBD healthcare worker undertaking ultrasound training.

Conclusions

This survey was the first step in a project of further work to investigate patient or clincians preferences for service delivery for imaging for assessment and monitoring imaging in IBD. Ultrasound has been shown to be similar in accuracy to MRE in detecting the presence of SBCD. Ultrasound is reported as quicker, more acceptable to patients and potentially safer when compared with MRE. Ultrasound is used widely in central Europe, Canada and some parts of the USA, but has not been as widely embraced in the UK. It would seem prudent to investigate broader stakeholder perceptions of the use of ultrasound to better understand perceived or potential barriers and enablers to ultrasound implementation in the worldwide healthcare systems and recognise and manage preferences for future service delivery.

flgastro-2021-102065supp001.pdf (30.1KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the BSG IBD group for their contributions. The authors would like to thank Jacqueline Campbell, head of committee services at the BSG, for her help in distributing and collating responses to this survey.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Shellie_Jean

Contributors: SJR: Survey creation, data analysis and manuscript formation and guaruntor. GM and ST: Survey creation and whole manuscript review.

Funding: This study is undertaken as part of doctoral study funded by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein) or of any geographic or locational reference does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: GM receives research funding from Janssen, Arla foods and Astra Zeneca and is a consultant for Alimentiv. ST is a consultant to Alimentiv and has share options in Motilent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1. Jones G-R, Lyons M, Plevris N, et al. IBD prevalence in Lothian, Scotland, derived by capture-recapture methodology. Gut 2019;68:1953–60. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:322–37. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chu TPC, Moran GW, Card TR. The pattern of underlying cause of death in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in England: a record linkage study. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:578–85. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burisch J, Vardi H, Schwartz D, et al. Health-Care costs of inflammatory bowel disease in a pan-European, community-based, inception cohort during 5 years of follow-up: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:454–64. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160:1570–83. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Feagan BG, et al. Treat to target: a proposed new paradigm for the management of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1042–50. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn's disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:341–53. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30012-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1324–38. 10.1038/ajg.2015.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allocca M, Furfaro F, Fiorino G, et al. Point-Of-Care ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2021;15:143–51. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taylor SA, Mallett S, Bhatnagar G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel ultrasound for the extent and activity of newly diagnosed and relapsed Crohn's disease (metric): a multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3:548–58. 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30161-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhatnagar G, Quinn L, Higginson A, et al. Observer agreement for small bowel ultrasound in Crohn’s disease: results from the METRIC trial. Abdom Radiol 2020;45:3036–45. 10.1007/s00261-020-02405-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, et al. ECCO-ESGAR guideline for diagnostic assessment in IBD Part 1: initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:144–64. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reinisch W, et al. Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:556–85. 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Panés J, Bouzas R, Chaparro M, et al. Systematic review: the use of ultrasonography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, assessment of activity and abdominal complications of Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:125–45. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Novak KL, Jacob D, Kaplan GG, et al. Point of care ultrasound accurately distinguishes inflammatory from noninflammatory disease in patients presenting with abdominal pain and diarrhea. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/4023065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grunshaw ND. Initial experience of a rapid-access ultrasound imaging service for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointestinal Nursing 2019;17:42–8. 10.12968/gasn.2019.17.2.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang I, Kamm M, Wong D, et al. P260 Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) when performed by gastroenterologists with 200 supervised scans is accurate and clinically useful for patients with Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2018;12:S232. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx180.387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horsthuis K, Bipat S, Bennink RJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed with us, Mr, scintigraphy, and CT: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Radiology 2008;247:64–79. 10.1148/radiol.2471070611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dong J, Wang H, Zhao J, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic tool in detecting active Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Radiol 2014;24:26–33. 10.1007/s00330-013-2973-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Puylaert CAJ, Tielbeek JAW, Bipat S, et al. Grading of Crohn's disease activity using CT, MRI, US and scintigraphy: a meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2015;25:3295–313. 10.1007/s00330-015-3737-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahmed O, Rodrigues DM, Nguyen GC. Magnetic resonance imaging of the small bowel in Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2016:1–14. 10.1155/2016/7857352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenup A-J, Bressler B, Rosenfeld G. Medical Imaging in Small Bowel Crohn's Disease-Computer Tomography Enterography, Magnetic Resonance Enterography, and Ultrasound: "Which One Is the Best for What?". Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:1246–61. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alshammari MT, Stevenson R, Abdul-Aema B, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive imaging for detection of colonic inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2021;11:1926. 10.3390/diagnostics11101926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miles A, Bhatnagar G, Halligan S, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography, small bowel ultrasound and colonoscopy to diagnose and stage Crohn's disease: patient acceptability and perceived burden. Eur Radiol 2019;29:1083–93. 10.1007/s00330-018-5661-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taylor SA, Mallett S, Bhatnagar G, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography compared with ultrasonography in newly diagnosed and relapsing Crohn's disease patients: the METRIC diagnostic accuracy study. Health Technol Assess 2019;23:1–162. 10.3310/hta23420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allocca M, Fiorino G, Bonifacio C, et al. Comparative Accuracy of Bowel Ultrasound Versus Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Combination With Colonoscopy in Assessing Crohn’s Disease and Guiding Clinical Decision-making. J Crohn’s Colitis 2018;12:1280–7. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans R, Taylor S, Janes S, et al. Patient experience and perceived acceptability of whole-body magnetic resonance imaging for staging colorectal and lung cancer compared with current staging scans: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016391. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yee HS, Chang MF, Pocha C, et al. Update on the management and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection: recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs hepatitis C resource center program and the National hepatitis C program office. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:669–89. 10.1038/ajg.2012.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. LH K. How and when to use biologics in psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatology 2010;9:s106–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hofman P, Nelson AM. The pathology induced by highly active antiretroviral therapy against human immunodeficiency virus: an update. Curr Med Chem 2006;13:3121–32. 10.2174/092986706778742891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. quiz e30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Novak K, Tanyingoh D, Petersen F, et al. Clinic-Based point of care transabdominal ultrasound for monitoring Crohn's disease: impact on clinical decision making. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:795–801. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brazilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases . Consensus guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Arq Gastroenterol 2010;47:313–25. 10.1590/S0004-28032010000300019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68:s1–106. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bryant RV, Friedman AB, Wright EK, et al. Gastrointestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease: an underused resource with potential paradigm-changing application. Gut 2018;67:973–85. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2021-102065supp001.pdf (30.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.