Abstract

Background:

The AMP studies (HVTN 703/HPTN 081 and HVTN 704/HPTN 085) are harmonized Phase 2b trials to assess HIV prevention efficacy and safety of intravenous infusion of anti-gp120 broadly neutralizing antibody VRC01. Antibodies for other indications can elicit infusion-related reactions (IRRs), often requiring pre-medication and limiting their application. We report on AMP study IRRs.

Methods:

From 2016–2018, 2,699 HIV-uninfected, at-risk men and transgender adults in the Americas and Switzerland (704/085) and 1,901 at-risk heterosexual women in sub-Saharan Africa (703/081) were randomized 1:1:1 to VRC01 10 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg, or placebo. Participants received infusions every 8 weeks (n=10/participant) over 72 weeks, with 104 weeks of follow-up. Safety assessments were conducted pre- and post-infusion and at non-infusion visits. A total of 40,674 infusions were administered.

Results:

Forty-seven participants (1.7%) experienced 49 IRRs in 704/085; 93 (4.8%) experienced 111 IRRs in 703/081 (p<0.001). IRRs occurred more frequently in VRC01 than placebo recipients in 703/081 (p<0.001). IRRs were associated with atopic history (p=0.046) and with younger age (p=0.023) in 703/081. Four clinical phenotypes of IRRs were observed: urticaria, dyspnea, dyspnea with rash, and “other”. Urticaria was most prevalent, occurring in 25 (0.9%) participants in 704/085 and 41 (2.1%) participants in 703/081. Most IRRs occurred with the initial infusion and incidence diminished through the last infusion. All reactions were managed successfully without sequelae.

Conclusions:

IRRs in the AMP studies were uncommon, typically mild or moderate, successfully managed at the research clinic, and resolved without sequelae. Analysis is ongoing to explore the potential IRR mechanisms.

Keywords: infusion related reactions, hypersensitivity, broadly neutralizing antibodies, AMP study, VRC01, HIV

BACKGROUND

HIV broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (bnAbs or mAbs) exhibit potent in vitro neutralization against multiple HIV strains, often target conserved viral envelope epitopes1, and have the potential to expand HIV prevention options and inform HIV vaccine development.2 This potential was evaluated for VRC01, a bnAb targeting the HIV-1 CD4 binding site, in two harmonized, randomized, controlled, Phase 2b proof-of-concept antibody mediated prevention (AMP) trials in the Americas and Europe (NCT02716675) and in sub-Saharan Africa (NCT02568215).3,4

In early phase studies, VRC01 demonstrated an acceptable safety profile.5–7 However, mAbs can elicit infusion-related reactions (IRRs),8 common adverse drug reactions in oncologic and rheumatologic applications with mAbs of murine or chimeric origin targeting human antigens; in contrast, VRC01 is of human origin and targets a viral antigen. IRR incidence varies by agent and is typically observed with the first or second mAb exposure,9–11 with symptoms temporally related to mAb administration and ranging from mild or moderate (e.g., dyspnea, nausea, pruritis) to life-threatening events such as anaphylaxis.8,12

The etiology of IRRs remains unclear; IgE- or non-IgE-dependent mechanisms have been implicated.13 The classical Gell and Coombs classification has been useful to provide mechanistic understanding. However, the diverse clinical presentations or IRRs may reflect multiple possible mechanisms, diagnosis may be difficult, and there is no standardized management guidance.12,14,15

IRRs were reported as part of the AMP trials’ safety assessments. Herein we describe the clinical phenotypes and management of AMP IRRs.

METHODS

Study participants

HVTN 704/HPTN 085 (704/085) enrolled transgender individuals (TG) and men who have sex with men (MSM) and TG at 26 clinical research sites (CRSs) in Brazil, Peru, Switzerland, and the US. HVTN 703/HPTN 081 (703/081) enrolled sexually active heterosexual women at 20 CRSs in Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. In October 2018, enrolment of 4,623 participants concluded. Volunteers were aged 18–50 years, in good general health, HIV-uninfected, and at risk for HIV acquisition.3,4

The Institutional Review Boards/Ethic Committees of participating CRSs approved the studies, which were conducted under the oversight of the NIAID Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). All participants gave written informed consent.

Infusion administration procedures

Participants were randomized 1:1:1 to receive VRC01 30 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or placebo.16 VRC01 or placebo (150 mL) was administered intravenously (IV) approximately every eight weeks, for 10 infusions total over about 72 weeks, with 104 weeks of follow-up. Safety assessments were conducted pre- and post-infusion and at subsequent q4-weekly non-infusion visits. From April 2016 through April 2020, 40,674 infusions were administered.

Prior to infusion, study product prepared in normal saline was stored at 2°- 8° C for up to 8 hours, including equilibration time of at least 30 minutes to room temperature. A 0.2 µm in-line infusion filter was used to reduce particulate contamination. Participants were not pre-treated (e.g., with antihistamines or glucocorticoids). Study product was administered using a volumetric pump over at least 60 minutes for the first infusion and over about 30 minutes for subsequent infusions, or longer per clinician judgement. Initial infusions were followed by a safety assessment period of approximately 30 minutes prior to discharge from the clinic, or shorter for subsequent infusions if the participant tolerated the infusions well.

IRR management and reporting

CRSs adhered to standard operating procedures on medical emergency management, including ensuring staff training in emergency management and timely access to advanced life support. CRSs maintained an emergency trolley with contents for airway and hemodynamic management. Additionally, site staff training, including IRR simulation exercises, was conducted prior to opening and periodically throughout the trial. Standardized IRR management guidelines were developed (Supplementary Appendix 1) and best practices were shared throughout the trials.

Participants underwent safety assessments, including vital sign monitoring, immediately before, during and after each infusion. Suspected IRRs of any severity grade were reported immediately to protocol safety staff based in each region of trial conduct, facilitating near-real time evaluation of safety events. Severity was assigned using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 (https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5×7.pdf), Division of AIDS Adverse Event Grading Table (https://rsc.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/daidsgradingcorrectedv21.pdf) and protocol-specific grading. Upon prompt notification, protocol safety staff blinded to treatment assignment reviewed each event with CRSs and determined infusion disposition (e.g., rechallenge at a slower rate or permanent infusion discontinuation). Participants who exhibited clinically significant hypersensitivity associated with study product were permanently discontinued from infusions. Rechallenge or follow-up infusions were preceded by re-confirmation of consent and were administered over at least one hour followed by an extended in-clinic observation period and daily calls during the minimum 4-day post-infusion safety assessment period. No pretreatment was administered prior to rechallenge or follow-up infusions.

Statistical analysis

To summarize baseline data, counts and proportions were used for categorical variables, and medians and ranges for quantitative variables. Associations of IRR occurrence with each baseline covariate were assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test for nominal variables and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test for quantitative variables. Within each trial separately, all reported association tests were adjusted for multiplicity using adjusted p-values (Holm, 1979) controlling the familywise error rate.17 Sample proportions of infusions that led to an IRR are reported, with 95% binomial score confidence intervals (CIs).

To estimate cumulative incidence of the first occurrence of an IRR by the number of received infusions, the complement of the Kaplan-Meier estimator for the survival function and 95% pointwise Wald CIs were employed. Participants who did not experience an IRR were right-censored. To estimate cumulative incidence by phenotype, a competing risks analysis was performed using the Aalen-Johansen estimator with 95% pointwise Wald CIs. All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Association of IRRs with baseline characteristics

In 704/085, 23,867 infusions were administered to 2,699 participants; in 703/081, 16,807 infusions were administered to 1,924 participants. In 704/085, 47 (1.7%) participants experienced 49 IRRs and in 703/081, 93 (4.8%) experienced 111 IRRs (p<0.001 for differential occurrence by trial) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Treatment and demographic characteristics of participants at enrollment by occurrence of an infusion reaction.

| HVTN 704/HPTN 085 (N=2699) | HVTN 703/HPTN 081 (N=1924) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Did not experience IRR | Experienced IRR | Unadjusted P-value | Adjusted P-value | Did not experience IRR | Experienced IRR | Unadjusted P-value | Adjusted P-value |

| Enrolled participants, n (%) | 2652 (98.3) | 47 (1.7) | 1831 (95.2) | 93 (4.8) | <0.001* | |||

| Treatment group, n (%) | ||||||||

| Placebo | 888 (98.3) | 15 (1.7) | 0.75 | 1.00 | 626 (98.3) | 11 (1.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VRC01 10 mg/kg | 885 (98.4) | 14 (1.6) | 601 (93.6) | 41 (6.4) | ||||

| VRC01 30 mg/kg | 879 (98.0) | 18 (2.0) | 604 (93.6) | 41 (6.4) | ||||

| Sex at birth, n (%) | ||||||||

| Male | 2627 (98.3) | 46 (1.7) | -- | -- | ||||

| Female | 25 (96.2) | 1 (3.8) | 1831 (95.2) | 93 (4.8) | ||||

| Region, n (%) | ||||||||

| USA/Switzerland | 1392 (98.2) | 25 (1.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||

| Peru/Brazil | 1260 (98.3) | 22 (1.7) | -- | -- | ||||

| RSA | -- | -- | 963 (94.5) | 56 (5.5) | 0.18 | 0.73 | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding RSA)** | -- | -- | 868 (95.9) | 37 (4.1) | ||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| Black or African American | 399 (97.8) | 9 (2.2) | 0.74 | 1.00 | 1809 (95.1) | 93 (4.9) | ||

| White | 837 (98.4) | 14 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Other*** | 1416 (98.3) | 24 (1.7) | 22 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 1518 (98.3) | 26 (1.7) | 0.91 | 1.00 | -- | -- | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 1134 (98.2) | 21 (1.8) | 1831 (95.2) | 93 (4.8) | ||||

| Age, median years (range) | 28 (18–52) | 26 (18–48) | 0.51 | 1.00 | 26 (17–45) | 24 (18–36) | 0.0038 | 0.023 |

| Body weight (kg), median (range) | 74.6 (42.5–152.3) | 71.4 (51.9–124.3) | 0.63 | 1.00 | 64.9 (37.0–121.0) | 66.3 (39.5–109.8) | 0.76 | 0.96 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (range) | 25.1 (15.4–39.9) | 24.6 (19.5–39.6) | 0.68 | 1.00 | 25.4 (16.0–40.7) | 26.1 (16.8–39.4) | 0.32 | 0.96 |

| History of allergic disorder, n (%) | ||||||||

| Yes | 811 (97.2) | 23 (2.8) | 0.011 | 0.10 | 118 (90.1) | 13 (9.9) | 0.0092 | 0.046 |

| No | 1841 (98.7) | 24 (1.3) | 1713 (95.5) | 80 (4.5) | ||||

| Eosinophil count, n (%) | ||||||||

| ≤ 500/µl | 2365 (98.1) | 45 (1.9) | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1749 (95.1) | 91 (4.9) | 0.45 | 0.96 |

| > 500/µl | 281 (99.3) | 2 (0.7) | 79 (97.5) | 2 (2.5) | ||||

This p-value represents the test of association between trial and occurrence of an infusion reaction. All other p-values represent within-trial comparisons.

Sub-Saharan Africa (Excluding RSA) includes the countries Botswana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

“Other” refers to participants identifying as Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaska Native, Indian, colored/mixed, multi-racial, or another race. Racial categories may not be directly comparable across regions due to differences in cultural perceptions of race.

IRR incidence was associated with a history of allergic disorder in 703/081 (adjusted p=0.046) and with younger age at enrollment in 703/081 (adjusted p=0.023) (Table 1). There was no evidence for an association of IRR occurrence and region, body weight, BMI, or eosinophil count (≤ vs. > 500/µl) in either trial, or race (Black/African American vs. White vs. Other) or ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx vs. non-Hispanic/non-Latinx) in 704/085.

Occurrence of IRRs by clinical phenotype and treatment assignment

Four distinct clinical phenotypes were observed in this study: urticaria; dyspnea with non-urticarial rash; dyspnea without rash; and ‘other.’ Urticaria was the most common IRR phenotype in both trials, experienced by 25 (0.9%) participants in 704/085 and 41 (2.1%) participants in 703/081 (Table 2). Urticaria onset was typically 30–60 minutes into the infusion; most were observed with the first infusion. IRRs characterized predominantly by dyspnea typically presented with sudden dyspnea, occasional chest tightness and/or facial flushing within the first few minutes of infusion. A few participants exhibited dyspnea and a non-urticarial, macular, erythematous rash. The ‘other’ IRR clinical phenotype includes primarily generalized pruritis and other rare IRRs like facial flushing or feeling hot, cough, throat irritation, nausea, dizziness, and epigastric pain.

Table 2.

Number of infusion reactions and participants with an infusion reaction by treatment group and clinical phenotype.

| No. of Infusion Related Reactions (%)* No. of Participants with an Infusion Related Reaction (%)# |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVTN 704/HPTN 085 | ||||

| Phenotype | Overall N=2699 |

Placebo N=903 |

VRC01 10 mg/kg N=899 |

VRC01 30 mg/kg N=897 |

| Overall | 49 47 (1.7) |

16 (32.7) 15 (1.7) |

14 (28.6) 14 (1.6) |

19 (38.8) 18 (2.0) |

| Urticaria | 26 25 (0.9) |

2 (7.7) 2 (0.2) |

10 (38.5) 10 (1.1) |

14 (53.8) 13 (1.4) |

| Dyspnea with rash | 3 3 (0.1) |

2 (66.7) 2 (0.2) |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (33.3) 1 (0.1) |

| Dyspnea without rash | 4 4 (0.1) |

1 (25.0) 1 (0.1) |

1 (25.0) 1 (0.1) |

2 (50.0) 2 (0.2) |

| Other | 16 15 (0.6) |

11 (68.8) 10 (1.1) |

3 (18.8) 3 (0.3) |

2 (12.5) 2 (0.2) |

| HVTN 703/HPTN 081 | ||||

| Phenotype | Overall N=1924 |

Placebo N=637 |

VRC01 10 mg/kg N=642 |

VRC01 30 mg/kg N=645 |

| Overall | 111 93 (4.8) |

12 (10.8) 11 (1.7) |

52 (46.8) 41 (6.4) |

47 (42.3) 41 (6.4) |

| Urticaria | 41 41 (2.1) |

2 (4.9) 2 (0.3) |

17 (41.5) 17 (2.6) |

22 (53.7) 22 (3.4) |

| Dyspneawith rash | 1 1 (0.1) |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

1 (100.0) 1 (0.2) |

0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) |

| Dyspnea without rash | 20 19 (1.0) |

2 (10.0) 2 (0.3) |

14 (70.0) 13 (2.0) |

4 (20.0) 4 (0.6) |

| Other | 49 41 (2.1) |

8 (16.3) 7 (1.1) |

20 (40.8) 17 (2.6) |

21 (42.9) 17 (2.6) |

The denominator for percentages is the total number of infusion reactions within each phenotype.

Participants are counted once within each phenotype. The denominator for percentages is the number of enrolled participants (N).

IRRs occurred more frequently in VRC01 than placebo recipients in 703/081 (6.4% versus 1.7%, adjusted p<0.001), but not in 704/085 (1.8% versus 1.7%, adjusted p=1) (Table 1). Twenty-eight of 160 (17.5%) IRRs developed in placebo recipients in both trials, 32.7% of IRRs in 704/085 and 10.8% in 703/081 (Table 2).

In each trial, urticaria occurred more frequently in VRC01 than in placebo recipients. VRC01 recipients experienced 92.3% of urticarias in 704/085 and 95.1% of urticarias in 703/081. The incidence of the other three IRR phenotypes was also predominantly noted in participants in VRC01 recipients in both trials with the exception of the ‘other’ IRR phenotype, which was predominantly noted among placebo recipients in 704/085 (Table 2).

In both trials combined, 16 participants experienced more than one (range 2–4) IRR (Supplementary Appendix 2). No consistent pattern of increasing or decreasing IRR severity was observed with repeated infusions among these 16 participants.

Clinical description of selected IRRs

Participant A, a 23-year-old Black African female, received her first infusion (VRC01 10mg/kg) in September 2018. At enrollment, she reported no history of allergies or atopy. After receiving 90mL of the 150mL infusion, she reported a generalized itchy rash and teary eyes. On examination, she exhibited periorbital edema and hives over the malar regions of the face, the arms, legs, and trunk. She had no other symptoms. All symptoms promptly resolved after hydrocortisone 200mg IV and promethazine 25mg IM. The participant left the clinic with no residual symptoms and a prescription for three days of oral cetirizine. She was contacted daily and reported no symptoms. An IRR of moderate severity was reported, and infusions were permanently discontinued per protocol (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Visual of two participant case studies of IRR.

A) Participant A, who developed urticaria after the first infusion. B) Participant B, who developed dyspnea with rash after the fifth infusion.

Participant B, a 24-year-old Black African female, received her first infusion (VRC01 10mg/kg) in November 2016. At enrollment she reported no history of past allergies or atopy. Her first four infusions were administered uneventfully. Five minutes into the fifth infusion, after 12.4mL had been administered at a rate of 400 mL/hr, she complained of sudden onset of chest tightness, denying any other symptoms. The infusion was immediately stopped. On examination, skin flushing was noted on the chest and developed into mildly erythematous macular lesions (Figure 1B). Except for mild tachycardia, vital signs and mental status were normal throughout observation and chest was clear on auscultation. She received hydrocortisone IV and promethazine IM and her symptoms resolved. She was discharged on oral chlorpheniramine; the participant was contacted daily and had no further complaints. An IRR (dyspnea with rash category) was reported, and infusions were permanently discontinued per protocol.

Participant C, a 33-year-old Black African female, received her first infusion (VRC01 10mg/kg) in June 2017. She denied any history of allergy or atopy. She completed the first infusion uneventfully. Seven minutes after beginning her second infusion she reported chest tightness with generalized lethargy, describing this as being unable to speak and feeling too weak to alert staff; she reported “I felt like I was dying.” The infusion was paused. The symptoms resolved spontaneously in less than one minute. Vital signs were normal. Dyspnea without rash, judged related to the infusion, was reported and shortly after complete symptom resolution she consented to infusion re-initiation. This was accomplished at a slower rate and the full volume was administered successfully. At the third infusion she complained of difficulty breathing due to chest tightness one minute into the infusion, which was then paused. On examination she had normal vital signs and no findings suggesting respiratory distress. Her symptoms resolved spontaneously within a minute after infusion pause; she was successfully rechallenged later the same day. The subsequent seven infusions were completed uneventfully.

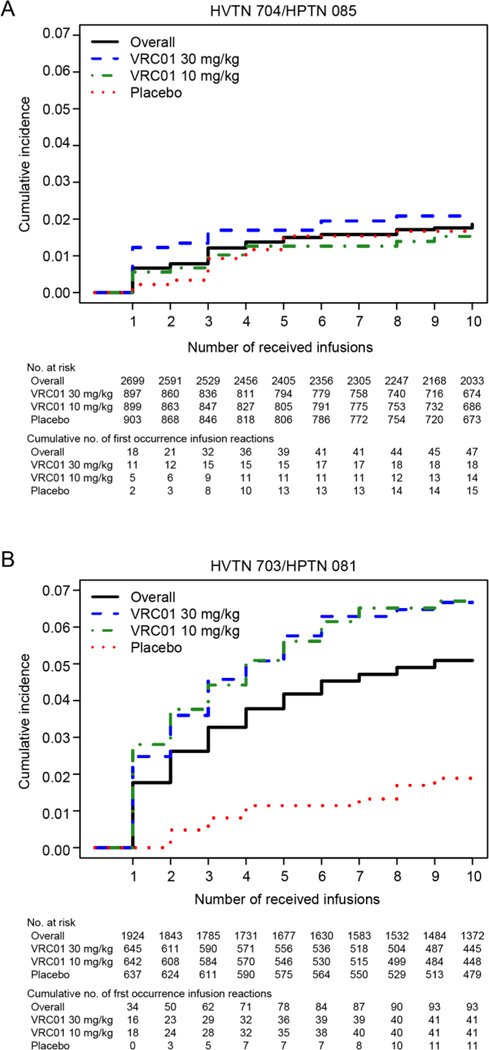

Cumulative incidence of IRRs

Cumulative incidence of the first occurrence of an IRR throughout the administration of 10 infusions was 1.9% (95% CI, 1.3 to 2.4) in 704/085 and 5.1% (95% CI, 4.1 to 6.1) in 703/081 (Figure 2A-B). In 703/081, the cumulative incidence was markedly greater in each VRC01 group than in the placebo group: 1.9% (95% CI, 0.8 to 3.0) in the placebo group, 6.7% (95% CI, 4.7 to 8.7) in VRC01 10mg/kg, and 6.7% (95% CI, 4.7 to 8.6) in VRC01 30mg/kg. No association was noted between cumulative IRR incidence and VRC01 receipt in 704/085.

Figure 2:

Estimated cumulative incidence, overall and by treatment, of the first occurrence of an infusion related reaction by the number of received infusions in 704/085 (Panel A) and 703/081 (Panel B)

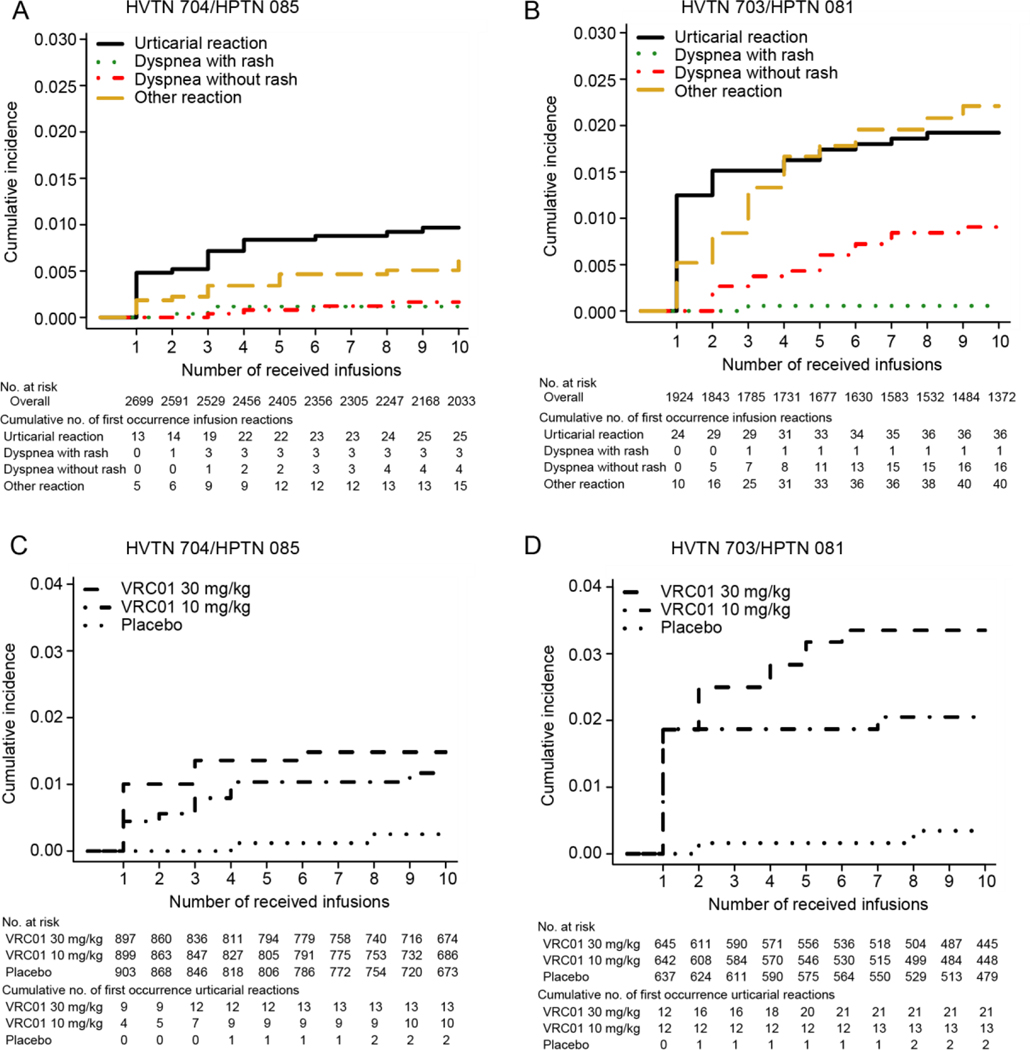

Through 10 infusions, cumulative incidence of urticaria was 1.0% (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4) in 704/085 and 1.9% (95% CI, 1.4 to 2.6) in 703/081 (Figure 3A–B). In both trials throughout the infusion phase, there was a trend suggesting a dose-response association between treatment and cumulative incidence of urticaria (Figure 3C–D). The association appeared stronger in 703/081; through 10 infusions, cumulative incidence was 0.3% (95% CI, 0.1 to 1.2) among placebo recipients, 2.1% (95% CI, 1.2 to 3.4) in VRC01 10mg/kg, and 3.4% (95% CI, 2.1 to 5.0) in VRC01 30 mg/kg. This dose-response association was not observed for other IRR clinical phenotypes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Estimated cumulative incidence of the first occurrence of each of the four infusion related reaction phenotypes (Panel A for 704/085 and Panel B for 703/081) and of urticaria stratified by treatment (Panel C for 704/085 and Panel D for 703/081) by the number of received infusions

Infusion administrations triggering IRRs

About one third of all IRRs in each trial occurred with the initial infusion (18 of 49 or 36.7% in 704/085 and 34 of 111 or 30.6% in 703/081). In 704/085, 0.67% (95% CI, 0.42 to 1.05) of first infusions triggered an IRR; in 703/081, it was 1.77% (95% CI, 1.27 to 2.46). All IRR phenotypes accrued at decreasing rates through the infusion period (Supplementary Appendix 3, Figure 2). About half of the urticarial IRRs developed with the initial infusion (13 of 26 or 50.0% in 704/085 and 24 of 41 or 58.5% in 703/081); urticaria was the most common type of IRR observed at the first infusion (Supplementary Appendix 4, Figure 3A–B).

IRR severity, discontinuations and rechallenges

Of 160 IRRs, 6 (3.8%) were deemed severe and 154 (96.2%) were deemed mild or moderate. All six IRRs graded severe occurred in in 703/081 among VRC01 recipients; five were urticaria, one was dyspnea with rash. One IRR was classified as a serious adverse event (SAE) per the investigator’s judgement. The participant, a 29-year-old woman who received VRC01 30mg/kg, developed a generalized urticarial rash, feeling of throat tightness and swelling around the eyelids 20 minutes into the first infusion. She was transferred to a nearby emergency room and was assessed and observed before discharge on oral prednisone and chlorpheniramine tablets. Infusions were permanently discontinued.

Of the 140 participants who experienced an IRR, 83 (59.3%) required permanent discontinuation of infusions (33 of 47, 72.2%, in 704/085 and 50 of 93, 53.7% in 703/081); 66 were due to urticaria, 4 were due to dyspnea with rash, 4 were associated with dyspnea without rash, and 9 were associated with other IRRs.

DISCUSSION

We describe four clinical IRR phenotypes among 4,623 AMP participants receiving 40,674 infusions of saline placebo or VRC01, a bnAb to prevent HIV-1 acquisition. These are the largest cohorts to receive any anti-HIV mAb, with each participant receiving up to ten infusions over a period of nearly two years. These diverse cohorts provide a unique opportunity to comprehensively examine the incidence, presentation, and management of IRRs to an anti-HIV mAb.

Overall, VRC01 was well-tolerated, with low rates of IRRs, which were medically managed without sequelae. Serum sickness, anaphylaxis, cytokine release syndrome, or other potentially life-threatening reactions were not observed in AMP.9 As described in the literature, urticarial IRRs generally occurred during initial exposure.18 Urticaria was uncommon with later infusions. As observed in other series, most other IRRs were also reported more commonly after the first or second exposure, and less often with subsequent infusions.9,13,15,19

IRRs were managed successfully with prompt intervention, as needed. As pre-specified in the protocol, participants who experienced clinically significant hypersensitivity, such as urticarial IRRs or dyspnea with cutaneous symptoms, received no further infusions, as re-exposure in such cases could trigger a more severe and potentially fatal reaction. However, this was not observed with the one AMP participant who received a second infusion after not disclosing a previous urticarial reaction to his first infusion.18,20 Most non-urticarial IRRs resolved without pharmacologic intervention and were followed by successful rechallenge (i.e., no IRR recurrence upon resumption of a paused infusion or administration of a subsequent scheduled infusion). In the remainder of cases (mostly urticaria) in which pharmacologic intervention was applied, antihistamines and corticosteroids were most commonly administered. No participants required hospital admission due to an IRR.

The underlying mechanisms for the observed IRRs remain under investigation. Acute urticaria is often related to IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated release of histamines, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins from mast cells in tissues and basophils in peripheral blood.21,22 While further laboratory assessment is ongoing, it is unlikely that the urticarial lesions we observed were IgE-mediated, which would typically require prior exposure. There is no evidence of prior exposure to this novel investigational product among participants who had urticaria, including no evidence of anti-drug antibody (ADA) among these participants.

While myriad clinical presentations were noted, all IRRs observed here are well described with administration of other mAbs.9,23 However, IRR incidence and severity observed in AMP is far lower than that observed with oncologic and anti-inflammatory mAbs. This is likely due to the fully human VRC01 targeting a viral epitope. The origin of chemotherapeutic mAbs falls on a spectrum from fully murine to chimeric (approximately 30% murine), humanized (approximately 5% murine), or fully human.24 Fully human mAbs such as VRC01 likely exhibit less antigenicity than mAbs with increased protein sequence variation from human lineages. Furthermore, unlike chemotherapeutic mAbs targeting human antigens, VRC01 targets epitopes on the HIV envelope, limiting potential stimulation of an autologous immune response, an observation further supported by the absence of ADA observed in AMP.

Notably, the 3.7% incidence of IRRs in VRC01 recipients is comparable to rates observed in trials of other fully human or humanized mAbs against non-human targets. In early COVID-19 treatment with anti-Spike casirivimab and imdevimab, IRRs and hypersensitivity were reported in 1.7% (3/176) of mAb recipients.25 Similarly, in COVID-19 treatment trials of anti-Spike bamlanivimab, IRRs were reported in 2.3% (7/309) of mAb recipients.26

IRR incidence in 704/085 was the same, about 1.7%, among VRC01 and placebo recipients. IRR incidence among 703/081 placebo recipients was also 1.7%, but among 703/081 VRC01 recipients rates were 6.4%, nearly three times the rate among VRC01 recipients in the Americas and Europe. These differences likely reflect multiple factors. The heavy and light chains of human IgG proteins exhibit extensive structural polymorphic (allotypic) forms. These potential human IgG allotype differences across individuals and ethnic groups can contribute to immunogenicity.9,27 ADA can be generated, which may result in an anti-allotype response: neutralization of the mAb, leading to enhanced clearance or precipitation of severe adverse reactions.25 No tier-3 ADA was detected in any of the samples from AMP participants with IRRs, and it is unclear whether the fact that VRC01 was isolated from an individual in North America, who was infected with subtype B virus, may have contributed to different IRR rates observed in each of these trials.27,28 29 Available literature suggests there may be an inverse correlation of infestation with helminths with allergy. With the “hygiene hypothesis” it is postulated that individuals who have less exposure to infections and infestations in childhood have insufficiently stimulated Th1 cells, resulting in a lack of counterbalance in the expansion of Th2 cells, hence a predisposition to allergy.30 However, in the AMP trials, occurrence of IRR was higher in the African cohort, a population group more likely to have higher exposure to other infections and infestations like helminth infections.

IRR differences in these cohorts may reflect demographic and medical history differences. Predictors of IRR risk for other mAbs include age, race, sex, geographic location, malignancy, and previous chemotherapy administration.31 The sex assigned at birth for most participants in 704/085 was male, and female in 703/081; studies report higher incidence of hypersensitivity or other allergic reactions among females compared to males.32 History of allergic disorder or atopy was significantly associated with IRR in 703/081, as has been reported for other mAbs.33 Younger age was also a predictor of IRR in the Black African cohort only, where the median age was 26 years compared to the MSM/TG cohort’s median age of 28 years.

Identifying potential clinical predictors of IRRs facilitates optimal preparation and management. Understanding underlying mechanisms and establishing biomarkers for the measurement of IRRs may aid accurate and timely diagnosis, inform optimal medical management and comparison of IRR profiles across molecules, and facilitate the development of a standardized classification of diverse IRRs to human mAbs against non-human targets.

This report illuminates key considerations for future studies evaluating similar mAbs. Though small differences were identified across each AMP cohort, overall, IRRs were rarely elicited and severe IRRs were particularly rare. Most IRRs were successfully managed by temporary infusion interruption, slowing the infusion, and symptom management. Where indicated, rechallenge was successful after complete symptom resolution. Thorough preparation, including availability of emergency resuscitation equipment, medications, and trained staff on-site, facilitated optimal responses to IRRs. As more mAbs for HIV and other infectious diseases advance, further research is required to elucidate IRR mechanisms and identify discriminatory biomarkers for diagnosis and clinical management.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

AI068614, AI068635, AI068618, AI068619, AI069412

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

NMM, SE, ST, SK, MJ, MRG, MAA, LN, KM RDLG, LC, CK, PA, MMGL have no COI to declare; SRW has received clinical trial funding from Janssen Vaccines

REFERENCES

- 1.Yaseen MM, Yaseen MM & Alqudah MA. Broadly neutralizing antibodies: An approach to control HIV-1 infection. Int. Rev. Immunol. 36, 31–40 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karuna ST & Corey L. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies for HIV Prevention. Annu. Rev. Med. 71, 329–346 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mgodi NM et al. A Phase 2b Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of VRC01 Broadly Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibody in Reducing Acquisition of HIV-1 Infection in Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Baseline Findings. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 87, 680–687 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edupuganti S et al. Feasibility and Successful Enrollment in a Proof-of-Concept HIV Prevention Trial of VRC01, a Broadly Neutralizing HIV-1 Monoclonal Antibody. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 87, 671–679 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bar KJ et al. Effect of HIV Antibody VRC01 on Viral Rebound after Treatment Interruption. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2037–2050 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledgerwood JE et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and neutralization of the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody VRC01 in healthy adults. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 182, 289–301 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer KH et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunological activities of multiple intravenous or subcutaneous doses of an anti-HIV monoclonal antibody, VRC01, administered to HIV-uninfected adults: Results of a phase 1 randomized trial. PLoS Med. 14, 1–30 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maggi E, Vultaggio A & Matucci A. Acute infusion reactions induced by monoclonal antibody therapy. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 7, 55–63 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doessegger L & Banholzer ML. Clinical development methodology for infusion-related reactions with monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 4, e39 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brennan PJ, Rodriguez Bouza T, Hsu FI, Sloane DE & Castells MC. Hypersensitivity reactions to mAbs: 105 desensitizations in 23 patients, from evaluation to treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 1259–1266 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtenstein L et al. Infliximab-Related Infusion Reactions: Systematic Review. J. Crohns. Colitis 9, 806–815 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picard M & Galvao VR. Current Knowledge and Management of Hypersensitivity Reactions to Monoclonal Antibodies. J. allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 5, 600–609 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dillman RO. Infusion reactions associated with the therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 18, 465–471 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos RB & Galvao VR. Monoclonal Antibodies Hypersensitivity: Prevalence and Management. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 37, 695–711 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz H-J. Management and preparedness for infusion and hypersensitivity reactions. Oncologist 12, 601–609 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corey L et al. Two Randomized Trials of Neutralizing Antibodies to Prevent HIV-1 Acquisition. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1003–1014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6, 65–70 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein JA et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133, 1270–1277 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi K et al. Severe infusion reactions to cetuximab occur within 1 h in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a nationwide, multicenter, prospective registry study of 2126 patients in Japan. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 44, 541–546 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel WH. Infusion reactions: diagnosis, assessment, and management. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 14, E10–21 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone SF, Phillips EJ, Wiese MD, Heddle RJ & Brown SGA. Immediate-type hypersensitivity drug reactions. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 78, 1–13 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zellweger F & Eggel A. IgE-associated allergic disorders: recent advances in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Allergy 71, 1652–1661 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isabwe GAC, Neuer G & Vecillas D. Hypersensitivity reactions to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies : Phenotypes and endotypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 159–170.e2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson PJ & Souriau C. Engineered antibodies. Nat. Med. 9, 129–134 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinreich DM et al. REGN-COV2, a Neutralizing Antibody Cocktail, in Outpatients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 238–251 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen P et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody LY-CoV555 in Outpatients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 229–237 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jefferis R & Lefranc M-P. Human immunoglobulin allotypes: possible implications for immunogenicity. MAbs 1, 332–338 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirino AJ, Ary ML & Marshall SA. Minimizing the immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 9, 82–90 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bharadwaj P et al. Implementation of a three-tiered approach to identify and characterize anti-drug antibodies raised against HIV-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 479, 112764 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG & van Ree R. Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis. Science 296, 490–494 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gobel BH. Chemotherapy-induced hypersensitivity reactions. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 32, 1027–1035 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimby E. Tolerability and safety of rituximab (MabThera). Cancer Treat. Rev. 31, 456–473 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Neil BH et al. High incidence of cetuximab-related infusion reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the association with atopic history. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 25, 3644–3648 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.