TP53 inactivation is the genomic biomarker most consistently associated with adverse outcomes in primary and metastatic prostate cancer. 70% of pathogenic TP53 mutations in prostate cancer are protein-stabilizing missense mutations leading to nuclear accumulation. Other TP53 alterations are truncating mutations (or rarely deep deletions) leading to protein loss. Here, we evaluated a genetically validated immunohistochemical assay with high sensitivity for missense mutations [1] in population-based cohorts.

This institutional review board-approved study included Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and Physicians’ Health Study (PHS) participants diagnosed with prostate cancer 1982–2009 during prospective follow-up [2] and followed through 2019 (HPFS) or 2014 (PHS). Diagnoses and metastases were confirmed by the participating health professionals, their treating physicians, and medical record review. Cause of death was adjudicated by physicians.

Tumor samples for the 962 men (94% cT1/T2; Supplementary Table S1), were from prostatectomy (95%) and transurethral resection of the prostate (5%).

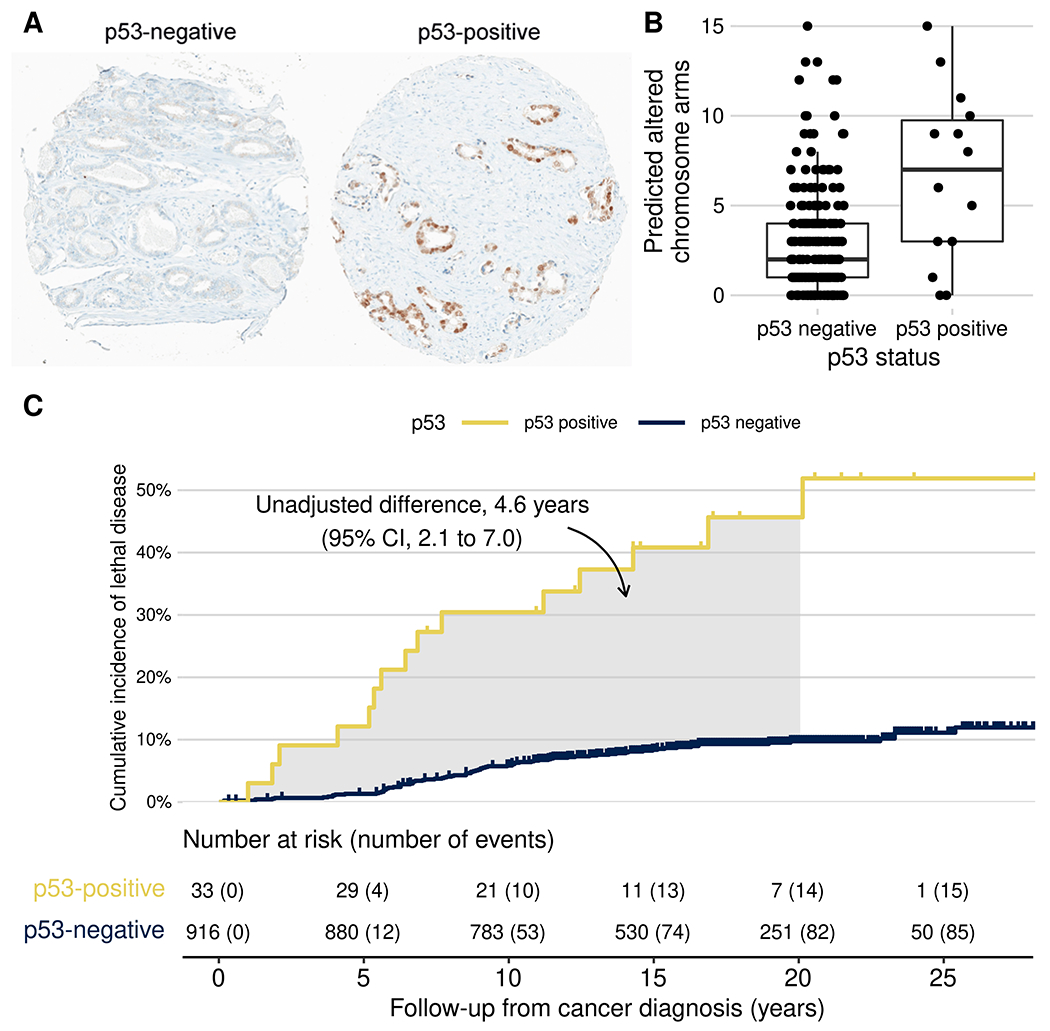

In 15 tissue microarrays [2], p53 immunostaining was performed in a CLIA-certified laboratory using the BP53-11 mouse monoclonal antibody (Roche) on the BenchMark platform (Ventana/Roche) [1]. Cores were dichotomously scored by consensus of two urologic pathologists (D.C.S., T.L.L.) as p53 nuclear accumulation if >10% of tumor nuclei showed p53 positivity (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of primary prostate tumors with and without p53 nuclear accumulation. (B) p53 expression and tumor aneuploidy (number of chromosome arms altered by gains or deletions, as predicted from the transcriptome). (C) p53 expression and cumulative incidence of lethal prostate cancer (metastases/prostate cancer death) among men with primary, non-metastatic prostate cancer in the HPFS (1986–2019) and PHS (1982–2014). The shaded area is equivalent to the unadjusted difference in cause-specific 20-year restricted mean time lost.

p53 nuclear accumulation was present in 36 tumors (prevalence 3.7%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.7–5.1%). p53-positive tumors had higher Gleason scores, tumor stage, and Ki67 proliferative indices than p53-negative tumors (Supplementary Table S1). PTEN loss [2] was more common among p53-positive (40%; Supplementary Table S1) than p53-negative tumors (16%; difference 24 percentage points, 95% CI 7–42). Tumor aneuploidy was quantified in 247 tumors using whole-transcriptome profiling [3]. p53-positive tumors had more chromosome arms predicted as gained or lost (mean 6.6) than p53-negative tumors (2.0; difference 3.8, 95% CI 2.2–5.5; Figure 1B).

Among 949 men with non-metastatic prostate cancer at diagnosis, 101 lethal events (metastases/ cancer-specific death) occurred over up to 30.9 years of follow-up (median 17.2). p53 status was associated with lethal disease after adjusting for age at diagnosis and Gleason grade groups from central re-review (HR 3.8, 95% CI 2.2–6.7) and, among men treated with prostatectomy, even adjusting for pTNM stage (HR 3.9, 95% CI 1.9–7.8) and prostate-specific antigen (Supplementary Table S2). Both p53 status and PTEN loss were associated with lethality (Supplementary Table S2).

We estimated the loss in life expectancy due to lethal prostate cancer during 20 years, accounting for competing mortality (Figure 1C) [4]. Men with p53-negative tumors lost, on average, 1.1 years due to lethal prostate cancer, compared to 3.9 years for p53-positive tumors (difference 2.9 years, 95% CI 0.1–5.6, adjusted for ordinal Gleason groups and age using inverse-probability weighting).

Our findings clinically validate a p53 immunostaining assay for TP53 missense mutations as a potent prognostic biomarker in primary prostate cancer. Limitations of the current study include the use of surgical samples and the inability of the assay to detect the (less common) truncation mutations. Future studies will test its utility in diagnostic biopsies and for therapy selection in metastatic disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Daniela Correia Salles, MD (1986-2021). We are grateful to the participants and staff of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study for their valuable contributions. In particular, we would like to recognize the contributions of Liza Gazeeva, Siobhan Saint-Surin, Robert Sheahan, Betsy Frost-Hawes, and Eleni Konstantis. We appreciate the support by the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. In addition, we would like to thank the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Tissue Microarray Core Facility constructed the tissue microarrays for this project (P30 CA06516).

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute (U01CA167552; 1P01CA228696; P30CA008748; P30 CA006516; P50CA58236; 5P30CA006973-52), the Department of Defense (Early Investigator Research Award W81XWH-18-1-0330, to K.H. Stopsack), and a Harvard–MIT Bridge Project (to L.A. Mucci). K.H. Stopsack, L.A. Mucci, and T.L. Lotan are Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigators.

Conflicts of Interest

K.H. Stopsack, D. Correia Salles, J.B. Vaselkiv, and S.T. Grob reported no potential conflicts of interest. L.A. Mucci receives prostate cancer research support from Bayer, Astra Zeneca, and Janssen, and is a paid consultant to Bayer. T.L. Lotan has received research support from Roche/Ventana, DeepBio, and Myriad Genetics for other studies.

References

- [1].Guedes LB, Almutairi F, Haffner MC, Rajoria G, Liu Z, Klimek S, et al. Analytic, Preanalytic, and Clinical Validation of p53 IHC for Detection of TP53 Missense Mutation in Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4693–703. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ahearn TU, Pettersson A, Ebot EM, Gerke T, Graff RE, Morais CL, et al. A Prospective Investigation of PTEN Loss and ERG Expression in Lethal Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. 10.1093/jnci/djv346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Stopsack KH, Whittaker CA, Gerke TA, Loda M, Kantoff PW, Mucci LA, et al. Aneuploidy drives lethal progression in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:11390–5. 10.1073/pnas.1902645116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Conner SC, Trinquart L. Estimation and modeling of the restricted mean time lost in the presence of competing risks. Stat Med 2021;40:2177–96. 10.1002/sim.8896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.