In the last decade, there has been an increasing awareness of the importance of addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH), the nonmedical conditions that influence health outcomes,1 as a systemic strategy for improving health, particularly among groups that are disproportionally affected by SDOH.2 While health care is important, it is estimated that these conditions, ranging from structural racism to socioeconomic factors, drive as much as 50% of health outcomes.3

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the urgency to address these broader societal conditions that are the root causes of poor health outcomes has been magnified by the widening racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality and comorbidities.4,5 At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), this work is fully linked to the agency-wide commitment to health equity, named CORE (strategies and framework are available on the Web site).6 CORE efforts, including CDC's SDOH approach, promote health equity where all people can attain their full health potential and not be negatively affected by socially determined factors including those related to structural racism and other forms of discrimination.7

Addressing SDOH is a priority for CDC. As such, the agency has undertaken multiple steps to ensure that efforts to address SDOH fall within CDC's broader health equity strategy and are built into the agency's work and not confined to a single program, national center, or public health topic.2,8

Emerging Roles of CDC and the Public Health Field

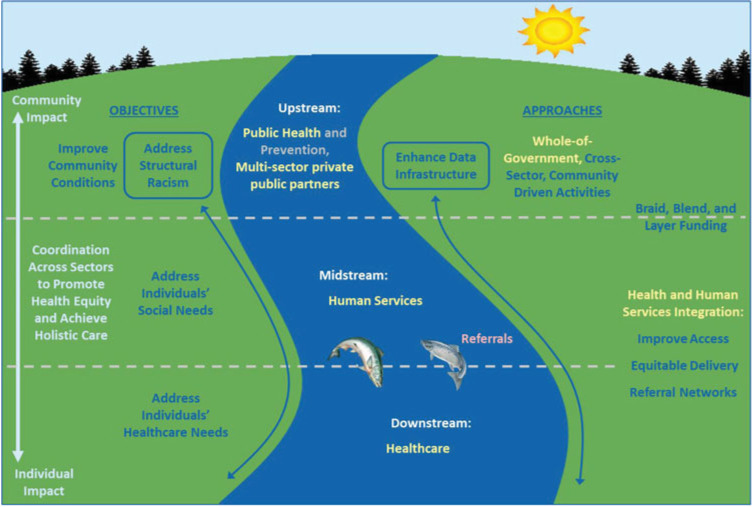

CDC's approach to addressing SDOH was born out of a recognition that nonmedical conditions have far-ranging impact on health and an awareness of the important role that public health can play in addressing them.9 Yet, neither CDC nor the public health sector has consistently been focused on the SDOH. The structure of public health appropriations and funding is often categorical and disease-specific, which can create challenges to addressing the underlying economic and social conditions.10 All too often, public health professionals have had to attend to the downstream consequences of harmful social conditions when attention to the upstream conditions would have reduced preventable illness, injury, and death. Now, as we depict in the SDOH ecosystem, public health has an opportunity to expand work in the upstream arena (Figure 1).12

FIGURE 1.

Social Determinants of Health Ecosystema

aAdapted From Castrucci and Auerbach.11 This figure is available in color online (www.JPHMP.com).

There are a growing number of examples of governmental public health successfully engaged in such efforts. These include working with community development corporations to expand affordable housing,13 promoting Complete Streets14 initiatives that enable mobility for all users,15 preventing and mitigating adverse childhood experiences,16 and taking steps in partnership with civil rights and social justice groups to oppose racism and other forms of discrimination that impact health.17,18

At the state, tribal, local, and territorial (STLT) levels, public health departments have often brought together partners to develop community health improvement plans to address findings from community health needs assessments, respond to local stakeholders, and meet accreditation standards. The newly revised version of the 10 Essential Public Health Services framework, a collaborative effort by several organizations, now directly calls out service #4 “strengthen, support, and mobilize communities and partnerships” as a specific public health department responsibility.19,20 In addition to convening and fostering multisector partnerships, the service includes “authentically engaging with community members.”20

CDC has done groundbreaking work in this arena. One long-standing example is the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program, which the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) began in 1999.21 The most recent iteration of REACH targets 4 areas of risk for chronic disease: the built environment, food insecurity, tobacco policy, and connections to clinical care. Recipients have proposed a variety of evidence-based practices to address these SDOH, ranging from bike paths and Complete Streets programs to farmers' markets with fruit and vegetable subsidies for income-eligible residents. Similarly, CDC's National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) has taken steps to reduce adverse childhood experiences,22 with targeted efforts in such areas as violence prevention and motor vehicles safety. The Office of Minority Health and Health Equity (OMHHE) and the National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) have an established history of work addressing the impact of racism, homophobia, transphobia, and other forms of discrimination on health and the steps that can be taken to combat these negative factors.

In fiscal year 2021, CDC received funding to launch the SDOH Accelerator Plan Initiative, which supports state, tribal, and local organizations to develop SDOH plans for future implementation.23 Additional seed dollars were also allocated to local coalitions to help identify lessons learned from successful SDOH initiatives.24

Subsequently, CDC leadership initiated an agency-wide process led by NCCDPHP to build and expand these efforts, deepening the agency's understanding of and commitment to promoting work on the SDOH.25 A key step was articulating the ways the public health sector can affect SDOH.

Possible Roles for CDC and Public Health Agencies at All Levels

There are 4 primary roles that governmental26 public health can take in addressing SDOH: as a changemaker, a convener, an integrator, and an influencer.

As a changemaker, public health leaders can support and inform policy efforts and lead interventions. This was recently demonstrated by the Los Angeles County public health initiative that resulted in the passage of a menthol cigarette ban.27 CDC-funded REACH grantees around the country have provided useful information that contributed to the adoption of Complete Streets policies in multiple communities.21 Numerous state and local jurisdictions have passed regulations related to reducing lead exposure and improving air quality to advance healthier living environments.28,29 Health departments have also acted as funders of smaller community organizations that were engaged in policy areas ranging from violence prevention to food security.

As a convener, public health organizations can bring together multisector partnerships to focus on relevant issues, and the 10 Essential Public Health Services identify this work as core to the field.19 CDC often finds itself in the role of convener, bringing together different parties, sometimes from different sectors, to work on issues of common concern. For example, on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee to the Director, CDC recently helped establish 3 work groups that bring together people from state and local health departments, the private sector, and academia to consider how best to address issues regarding equity, data, and laboratory quality.30

As an integrator, public health departments can also provide important data to their local and state constituents. They can integrate various sources of data—including data from non–health sectors—and work with communities to identify dissemination strategies. They can also assist with the evaluation of the health outcomes, given their knowledge of epidemiology and related evaluation strategies. In numerous places such as Chicago, Seattle, and Boston, public health departments provide GIS maps of community needs and assets.31–34 Decision makers have reported that these maps are critical data sources31 and can be joined with other data sources to provide important information. At CDC, PLACES,35 which provides local data on important chronic diseases, and environmental justice data36 are important sources of this kind of granular information. As part of its data modernization initiative, the agency is building capacity for public health entities to access data from other sectors such as housing and education.37,38

Finally, public health can be an influencer by using its prominence and scientific expertise to inform the behavior of organizations and individuals. When CDC Director Rochelle Walensky announced that racism is a public health threat,39 it reinforced actions that had already taken place in communities around the country and supported many others as they took subsequent action.40 This work can foster community trust and promote health-enhancing programs and policies across sectors that can lead to systems and environmental changes.

The CDC Framework

With these roles in mind, CDC next focused on developing a high-level framework to guide its work on SDOH and as a resource for STLT partners. This framework was informed by Healthy People 2030,41 WHO,42 and the newly revised 10 Essential Public Health Services.19 The 6 pillars of the framework are explained in the following text and illustrated in Figure 2. These pillars represent functional approaches to SDOH where work is needed.

FIGURE 2.

CDC SDOH Framework

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; SDOH, social determinants of health. This figure is available in color online (www.JPHMP.com).

Policy and law reflect CDC's work to understand existing policies that have a positive or negative impact on health (eg, tobacco-free laws and redlining, respectively). As an evidence-based agency, CDC has examined which social and economic policies are most likely to result in improved health. The Health Impact in Five Years or Less or HI-543 effort identified 14 policies with solid evidence of health improvement in a relatively short period of time. Six of the 14 policies are related to SDOH factors. They include early childhood education, earned income tax credits, and home improvement loans to low-income families. Similarly, The Community Guide44 has drawn attention to the policies and laws that improve health such as those that prevent motor vehicle–related injuries and decrease tobacco utilization.

Infrastructure and capacity reflects various strategies that have been shown to help address SDOH including public health workforce competencies, training, financial investments, and information technology systems. Advances have recently been made in this pillar because of the creation of the line item for SDOH at CDC. With the new funding, CDC issued the first SDOH-specific Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO), funding 20 state and local grantees to complete plans to address SDOH.23 More recently, CDC issued a workforce and infrastructure NOFO,45 totaling close to $4 billion. This NOFO was unusual in that it allowed great flexibility in the types of positions that could be funded. If health departments choose, they can hire specialists in housing, transportation, or other sectors that would influence the social and economic conditions.

Community engagement reflects CDC's work to involve and engage active participation in decision making of those most impacted by the SDOH. In the last 18 months, innovative approaches that support community participation have been funded. For example, the Community Health Workers for COVID Response and Resilient Communities initiative46 led to the hiring of scores of residential neighborhood leaders to deliver health messages and services to their fellow community members. And $2.25 billion in COVID funding for the National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved Communities, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities, was awarded to 108 states, counties, cities, and territories.47 These dollars are supporting a wide variety of initiatives aimed at reducing health disparities and increasing health equity, many related to SDOH. Community engagement is a major expectation of these grantees.

Partnerships and collaboration refer to linkages built between public health and community organizations and institutions, public and private, that represent multiple sectors.8,21 Demonstrating the ways to build nontraditional partnerships, CDC has strengthened its collaboration with multiple federal agencies both within and external to HHS. For example, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and CDC are working in alignment to reduce homeless encampments and support affordable healthy housing. CDC has participated in strategic planning with the Department of Transportation, emphasizing the value of walkable and bikeable communities and mass transportation in rural and low income income jurisdictions. And CDC is collaborating with the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to make screening for and referrals to address individual health-related social needs a routine part of health care delivery.

Evaluation and evidence building reflects CDC's work to gather evidence and advance scientific understanding of effective strategies that have been shown to improve SDOH. Efforts are underway to identify the strategies that have been successful in addressing the SDOH and to assist with the development of appropriate measures. A recent effort with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) identified 42 communities that had achieved positive results,24 ranging from new policies related to tobacco-free spaces to the design and planning of bike paths. So too, evidence from prior programs demonstrate the success that communities can have when they work together.

Data and surveillance refers to the collection and analysis of SDOH variables. As attention to SDOH has grown, CDC has taken steps to increase access to data and surveillance that measure a wider array of factors that impact health. Recently, CDC developed new SDOH modules for the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Systems (PRAMS), and the National Diabetes Surveillance System. Questions assess food insecurity, housing, education, health care access, experience with discrimination, and economic stability. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) also developed the Social Vulnerability Index,48 which is a tool for identifying risk factors, including SDOH, affecting specific geographic areas. CMS has proposed rules that require hospitals to screen patients for social needs related to housing, transportation, food security, and interpersonal safety. CDC is exploring ways to make such information available to the public health sector in an aggregate format through its support of The Gravity Project.49

The Future of SDOH Work—The Time Is Now

Today, CDC's work on SDOH is at a crucial junction. Noteworthy steps have been taken to encourage an agency-wide awareness of the relevance of social and economic factors in the lives of the public, particularly those who experience elevated risk for preventable illness, infectious diseases, injuries, and deaths. And the agency is poised to expand even further. But this work is still at an early stage. Opportunities to bring these efforts to scale could include engagement, technical assistance, and sustainable partnerships with the field. Recognizing that social determinants are key to attaining more equitable health for communities and individuals can support and sustain this work. The key to success is understanding the evidence from multiple perspectives, engaging communities in meaningful and sustainable ways, aligning with partners from multiple sectors, and spreading the lessons learned. CDC is prioritizing these efforts and embedding them into CDC's overall comprehensive CORE approach to advancing health equity. Long-term health improvement depends on it.

Footnotes

SDOH Task Force is the cross-agency task force addressing social determinants of health at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Karen Hacker, Email: pju3@cdc.gov.

John Auerbach, Email: jxa4@cdc.gov.

Robin Ikeda, Email: rmi0@cdc.gov.

Celeste Philip, Email: fhd7@cdc.gov.

Debra Houry, Email: vjz7@cdc.gov.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health: know what affects health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm. Updated September 20, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 2.De Lew N, Sommers BD. Addressing social determinants of health in federal programs. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(3):e221064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(2):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC COVID-19 response health equity strategy: accelerating progress towards reducing COVID-19 disparities and achieving health equity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/cdc-strategy.html. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. Presidential Covid-19 Health Equity Task Force final report and recommendations. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=100. Published 2021. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC CORE Health Equity Science and Intervention Strategy. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/core/index.html. Updated May 16, 2022. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is health equity? https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthequity/index.html. Updated May 11, 2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 8.Lipshutz JA, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, Skillen E, Naoom S, Irune I. Leveraging social and structural determinants of health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: a systems-level opportunity to improve public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(2):E380–E389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paving the road to health equity. https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/publications/health_equity/index.html. Updated November 30, 2020. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- 10.Fleming PJ, Spolum MM, Lopez WD, Galea S. The public health funding paradox: how funding the problem and solution impedes public health progress. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(1):10–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castrucci B, Auerbach J. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Affairs Blog. Posted January 16, 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190115.234942/. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 12.Whitman A, De Lew N, Chappel A, Aysola V, Zuckerman R, Sommers BD. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2022. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massachusetts Public Health Association. Partnerships for housing. https://mapublichealth.org/housing-policy-partnerships. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 14.US Department of Transportation. Complete Streets. https://www.transportation.gov/mission/health/complete-streets. Updated August 24, 2015. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 15.Salud America. 15 examples of health involvement in Complete Streets. https://salud-america.org/15-examples-of-health-involvement-in-complete-streets/#:∼:text=Although%20Complete%20Streets%20initiatives%20are%20traditionally%20led%20by,played%20a%20role%20in%20communities%20across%20the%20country. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 16.National Governors Association, Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. A case study of Building Strong Brains Tennessee. https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/CaseStudyBuildingStrongBrainsTN.pdf. Published March 2021. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 17.Michigan Health and Human Services. Mother Infant Health & Equity Improvement Plan. https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/keep-mi-healthy/maternal-and-infant-health/miheip. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- 18.American Public Health Association. Social justice and health. https://www.apha.org/what-is-public-health/generation-public-health/our-work/social-justice. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- 19.The Public Health National Center for Innovations. Celebrating 25 years and launching the revised 10 Essential Public Health Services. https://phnci.org/national-frameworks/10-ephs. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 20.Public Health Accreditation Board. Standards & Measures Version 2022. https://phaboard.org/version-2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. REACH. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/reach.htm. Updated May 26, 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html. Updated April 2, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health Accelerator Plans. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/programs-impact/sdoh/accelerator-plans.htm. Updated October 27, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving social determinants of health—getting further faster. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/programs-impact/sdoh/community-pilots.htm. Updated April 4, 2022. Accessed June 21, 2022.

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/programs-impact/sdoh.htm. Updated March 29, 2022. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- 26.DeSalvo KB, Wang YC, Harris A, Auerbach J, Koo D, O'Carroll P. Public Health 3.0: a call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kekatos M. LA City Council votes unanimously to ban the sale of flavored tobacco products. ABCNews. June 2, 2022. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/la-city-council-votes-unanimously-ban-sale-flavored/story?id=85133858#:∼:text=The%20Los%20Angeles%20City%20Council,menthol%20cigarettes%20and%20flavored%20cigars. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 28.National Center for Health Housing. State and local lead laws. https://nchh.org/information-and-evidence/healthy-housing-policy/state-and-local/lead-laws. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 29.The Tishman Center at the New School. Local policies for environmental justice: a national scan. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/local-policies-environmental-justice-national-scan-tishman-201902.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advisory Committee to the Director (ACD). https://www.cdc.gov/about/advisory-committee-director/index.html. Updated May 17, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 31.Musa GJ, Chiang PH, Sylk T, et al. Use of GIS mapping as a public health tool—from cholera to cancer. Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boston Public Health Commission. Health of Boston 2016-2017. https://www.bphc.org/healthdata/health-of-boston-report/Pages/Health-of-Boston-Report.aspx. Published 2017. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 33.Public Health Seattle & King County. City Health Profiles. https://kingcounty.gov/depts/health/data/city-health-profiles.aspx. Updated June 1, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 34.Chicago Department of Public Health. Healthy Chicago 2.0. 2016-2020. hrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/depts/cdph/CDPH/Healthy%20Chicago/HC2.0Upd4152016.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PLACES: local data for better health. https://www.cdc.gov/places/index.html. Updated April 4, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Environmental Public Health Tracking. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/tracking/topics/EnvironmentalJustice.htm. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data modernization initiative. https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/data-modernization/index.html. Updated May 10, 2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH) and PLACES data. https://www.cdc.gov/places/social-determinants-of-health-and-places-data/index.html. Updated May 27, 2022. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Media statement from CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, on racism and health. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0408-racism-health.html. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 40.American Public Health Association. Analysis: declarations of racism as a public health crisis. https://www.apha.org/-/media/Files/PDF/topics/racism/Racism_Declarations_Analysis.ashx. Published 2021. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 41.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. HealthyPeople.gov, Healthy People 2020, discrimination. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/discrimination. Updated February 6, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022.

- 42.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health impact in 5 years. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hst/hi5/index.html. Updated February 2, 2022. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Community Guide. https://www.thecommunityguide.org. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strengthening U.S. public health infrastructure, workforce, and data systems. https://www.cdc.gov/workforce/resources/infrastructuregrant/index.html. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2022.

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Health Workers for COVID Response and Resilient Communities (CCR). https://www.cdc.gov/covid-community-health-workers/index.html. Updated April 15, 2022. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC announces $2.25 billion to address COVID-19 health disparities in communities that are at high-risk and underserved. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/p0317-COVID-19-Health-Disparities.html. Published March 17, 2021. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- 48.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Updated March 15, 2022. Accessed June 23, 2022.

- 49.The Gravity Project. The Gravity Project. https://thegravityproject.net/. Accessed July 22, 2022.