Abstract

The amendments to the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of India in 2019 address non-binary persons’ constitutional rights, recognition of their gender identity, and non-discrimination laws across institutional spaces (for example, family, workplace, education, and healthcare). The Act discusses legal rights in isolation of praxis, structural support and, more importantly, lacks guidelines needed to substantively access rights. Such a disconnection relegates human rights to merely legal changes with limited practice. In this article, we discuss the achievements and failures of the act from the perspective of a transgender community in India, and the impact it has had on their lives from its formulation in 2014. Although non-binary communities are recognized, they face severe abuse and discrimination. We analyse accounts of 15 transgender persons’ lived experiences and challenges they faced in claiming their rights in Kolkata, a metropolis in eastern India. We used the framework of substantive access to rights, that is, the actual ability to practice and access documented rights, to critically discuss our findings across family, work, education, and healthcare spaces, often showing the gaps between achieved legal status, and the practical realities on the ground. We provide several recommendations to bridge these gaps—improving educational equity for non-binary people, including transgender specific training for healthcare providers and, more importantly, increasing the adequate representation of non-binary people in the positions of negotiation. The road to claiming social and economic rights following legal rights for non-binary gender communities cannot be achieved without overcoming their erasure within families and hypervisibility in public spaces.

Keywords: community perspective, discrimination, intersectionality, legal rights, non-binary gender identity, public spaces

1. Introduction

The passage of the Yogyakarta plus 10 principles1 institutionalized the inclusion of non-binary gender identities such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ+) persons in the discussions of human rights (Grinspan et al. 2017). Since then, a rapidly growing body of research and activism at regional, national, and international levels indicated that we are in a historic moment when rights for individuals with diverse and overlapping gender identities are gaining recognition (Farrior 2009). Individuals are born with basic human rights, so why is there a delayed recognition of rights among the LGBTIQ+ communities? Chua (2019) attempted to answer this question by pointing out the difference between human rights praxis as a ‘mode’ through which human rights can be made sense of or put into action, as opposed to a ‘theory’, where human rights is a way of life. Embodying aspects of practice serves not only as conduits and triggers but also something much deeper, that is, co-constructing the processes of human rights practice. Protagonists who adopt a rights-based approach form a community of activists who maintain and spread the practice and implementation of rights through collective action and social movements, introducing new claims and claimants. Human rights practice, therefore, forms the heart and soul of human rights discourse or theory.

Significant gaps and delays exist between the formulation of laws and actual practice of these laws leading to barriers and struggles for accessing rights even when policies favouring LGBTIQ+ communities are increasingly accepted worldwide (Parker 2007). Most research on LGBTIQ+ communities within the human rights framework has focused on the legal side of the policies (Cossman 2018; Lakkimsetti 2020) and little has been analysed from the perspective of practice, access, or implementation of these policies (Schulz 2019). The diversity of non-binary gender identities and their specific barriers to access rights situated within spaces and places of their everyday lived experiences has been studied even less. For example, will the barriers to practising human rights differ for a white gay man in the Global North compared to a transgender2 person in the Global South? Different countries have different levels of progress in terms of human rights for LGBTIQ+ communities (Ilkkaracan 2015). In 2016, 25 countries allowed gay marriage, while ten punished homosexuality with death (Dicklitch-Nelson et al. 2019). Recently published books on gay rights (Hindman 2011) and transgender movements (Nownes 2019) document the struggles, setbacks, and victories of the LGBTIQ+ communities in the United States; similar literature exists for Canada (Phillips 2014). Post-colonial scholars, however, have emphasized that focusing exclusively on legal rights without interrogating systems such as colonialism, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, patriarchy, and class that impede access to legal rights relegates human rights to merely legal changes that affect practice in very limited arenas (Baxi 2007; Kannabiran 2016). South Asian3 scholars further emphasized that understanding social struggles to claim and access legal rights influenced by power, inequitable resources, and political impact becomes central to human rights practice in South Asian countries (Armaline et al. 2015). This becomes even more critical for the rights of communities with non-binary gender identities where obvious barriers such as lack of power, resources, and political influence are wrapped within rigid heteronormative norms and behaviours. It is well known that the State had not until recently made efforts to protect the interests and rights of the LGBTIQ+ people in South Asia; thus, implicitly contributing to the discrimination against them.

Recently across South Asia new legislation and administrative decisions to recognize transgender and other gender-diverse people’s identities have been introduced. The governments following various international human rights principles, laws, and reports recognized their constitutional rights and granted them equal citizenship (Jain and DasGupta 2021). In November 2013, the Bangladesh government officially recognized hijra4 (in Urdu) as a ‘third gender’5 (Jain and Kartik 2020), which later in 2018 led to a separate category along with male and female categories for the question on gender on voter registration forms. In the same year, Pakistan voted the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill into a law, which recognized non-binary people with constitutional rights (Jain and Kartik 2020). In recent years India witnessed legal and policy changes which significantly affected gender-diverse communities. The 2011 census of India added an ‘other’ category along with male and female categories to the question on gender for the first time. Although ‘other’ is nowhere near the respectful and rightful inclusion of diverse gender identities, it is a leap towards acknowledgment. In the 2021 Census, for the first time in history, the options listed under the question asking the sex of the household head will be ‘male,’ female’ and ‘transgender’ (Ministry of Home Affairs). In 2018, after decades of struggles, activism, and social movements from all fronts, the Supreme Court of India in a historic decision repealed the application of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a colonial-era law that criminalized consensual homosexual activities between adults (Dutta 2020b). As Dutta stated, although this legal reform was a landmark moment heralding the progression of gender-diverse people from criminality to citizenship, we should further build on this achievement for facilitating empowerment, rights, and opportunities for people on a gender spectrum from less privileged backgrounds (Dutta 2020a). Most recently, an amended version of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was passed in 2019. This Act, which was previously a bill, was first formulated in 2014 and went through changes over the years (see Section 1.1 for a brief history).

Following Dutta’s appeal to build on the momentum of decriminalization of Section 377 and move towards rights-based policies and interpretation (Dutta 2020a), in this article, we focus on the critical analysis of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act from the perspectives of a transgender community following the substantive access and practice of human rights approaches. From here onwards, we will refer to this Act as the ‘ Trans Act’ for brevity. Existing scholarships have discussed the prior and latest versions of the Trans Act, its merits, and challenges within legal and political frameworks, thus neglecting to analyse its policies from the perspectives of non-binary community members from diverse family, economic, and social backgrounds (Sayan Bhattacharya 2019; Loh 2018). In India, despite historical and cultural practices, and recent legal recognition, non-binary persons simultaneously experience hypervisibility as adbhut (in Sanskrit) or strange, and invisibility as rights-bearing citizens for decades. We argue in this article that understanding the structural/institutional mechanisms and their intersectionality, identifying the barriers, and finding feasible ways to overcome them will reduce the gap between the formulation of legal rights and actual access to rights.

1.1 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of India

In 2014, the Supreme Court of India delivered a judgment following a written petition filed by the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA). This judgment, popularly known as the NALSA judgment, was supported by prominent transgender activists like Lakshmi Narayan Tripathi. The judgment included directives for the legal recognition of people with non-binary gender identities and developed social welfare schemes such as reservations in State educational institutions and the public employment sector (Jain and Kartik 2020). A praiseworthy characteristic of this judgment was that it recognized the diversity and fluidity of gender identities unique to India’s regional, cultural practices, and linguistic diversities (Chakrapani et al. 2017) and had several positive effects on gender-diverse communities. It sets a precedent for the expansion and protection of their constitutional rights. On the heels of the NALSA judgment, came the first act for gender-diverse people’s rights.

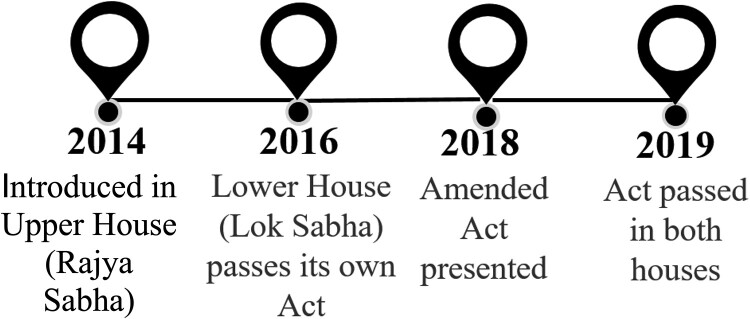

The member of parliament (MP) Tiruchi Siva, introduced the Rights of Transgender Persons Act in 2014 (Aswani 2020). This version of the Act was developed in close collaboration with the gender-diverse communities and was passed unanimously in the Rajya Sabha (upper house of the parliament of India). The Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment (MSJE), next drafted parallel legislation in 2015 and invited comments for improvement from civil society organizations and gender-diverse groups (Semmalar 2017). However, this legislation was never introduced, and the MSJE later introduced another piece of legislation, titled the ‘Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill’ in the Lok Sabha (lower house of the parliament) in 2016. A striking failure was that this legislation was not inclusive; it did not incorporate the feedback from the community-led consultations (Government of India 2015), thereby drawing significant criticism from the LGBTIQ+ community for violating their human rights. For example, the Bill indicated that a ‘screening committee’ would have the power to declare the gender identity of a non-binary person (Sawhney and Grover 2019), which directly goes against the rights of self-declaring one’s gender identity, in violation of one’s right to dignity and bodily autonomy. The Bill’s inclusion of intersex persons within the umbrella term of transgender was also criticized, as not all intersex persons identify as transgender persons. In response to the protests for stopping the Bill from passing, the Lok Sabha set up a Standing Committee and invited several groups such as human rights and gender activists to revise it. Sampoorna Working Group (SPWG) worked with the Committee to meet the demands made by the gender-diverse groups for revisions to the Bill (Jain and Kartik 2020). On 17 December 2018, the Lok Sabha passed a revised version of the Bill with 27 amendments, including an improvement in the definition of a transgender person. In 2019, this amended Bill was declared as an Act with nine clauses and 23 subclauses. Fig. 1 summarizes the landmark events in the pathway to the 2019 Trans Act and Table 1 highlights its important clauses.

Figure 1.

Timeline showing the landmark events leading to the 2019 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of India.

Table 1.

Major highlights of the 2019 Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of India

| Clauses/Chapter | Details | Criticism by Activists |

|---|---|---|

| Prohibition against discrimination [Chapter 2] | Discrimination against a transgender person including denial of service or unfair treatment in relation to: (i) education; (ii) employment; (iii) healthcare; and (iv) housing. | |

| Right to ‘self-perceived’ gender identity [Chapter 3] | A transgender person may make an application to the District Magistrate for a certificate of gender identity. The District Magistrate will issue such certificate based on the recommendations of a District Screening Committee. The Committee will comprise: (i) the Chief Medical Officer; (ii) District Social Welfare Officer; (iii) a psychologist or psychiatrist; (iv) a representative of the transgender community; and (v) an officer of the relevant government. | Right to self-declare one’s perceived gender identify cannot be done without a certification by the District Magistrate and after proof of a sex reassignment surgery is provided. This goes against the right to dignity and bodily autonomy, puts additional burden on their health costs, and forces them to go through painful and often corrupt bureaucratic processes. |

| Offences and Penalties [Chapter 8] | The Act recognizes the following: (i) begging will no longer be penalized; (ii) penalize whoever denies access of a public place to transgender individuals; (iii) penalize whoever denies residence in household, village, etc.; (iv) penalize the physical, sexual, verbal, emotional and economical abuse of a transgender person. These offences will lead to imprisonment between six months and two years and a fine. | |

| Minor’s Rights [Chapter 5: 12] | Enforces a minor’s right of residence compelling any transgender person below 18 years to cohabit with their natal family. | Families are often a source of gruesome violence against the transgender community leading them to separate from their natal family. |

| Transgender women and Hijra | Strongly focuses on transwomen and hijras. | There is little emphasis on other non-binary identities such as intersex, gender queer and even transgender men. |

Source: The Gazette of India, The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019.

Even though the current Trans Act makes the definition of ‘transgender’ more inclusive of other non-binary gender identities, the Act has attracted several criticisms. The most important criticism is that it does not mention self-affirmation of gender, which directly contradicts the 2014 verdict of the Supreme Court of India that upheld the right of all citizens to the self-determination of their gender identity. It explicitly contradicts the NALSA verdict by stating that transgender individuals will have to apply for a gender verification certificate to the District Magistrate, who will then refer the application to a District-Level (an administrative unit in India) Screening Committee for further implementation and evaluation.

Existing literature analyses the Trans Act following legal frameworks, while our article makes a novel contribution by analysing the potential impact of the Act from the perspectives of transgender and other gender-diverse communities. The main focus of this article is how legal reforms and policies translate to the everyday lives of the members of the community; we examine their anticipation and apprehensions regarding the current clauses included in the Trans Act, which has affected their lives since 2014. This community-based approach is crucial, as it is only after countrywide protests, where gender activists burnt copies of the prior Bill on the streets and conducted several meetings and marches, that the central government altered the pathological definition of ‘transgender’ in the current version of the Act. Therefore, LGBTIQ+ communities have successfully stalled the rights-violating clauses before and will continue to evaluate the Trans Act through human rights, recognition, and empowerment lenses. Protest meetings were already being conducted across the country against this act, which was passed a few months before we started our data collection for this article in December 2019 (see Section 2 for details). It is important to understand the achievements and criticisms from the perspectives of community members for overcoming the barriers that restrict implementation of legal rights in the everyday lived experiences of non-binary people across institutional spaces (such as family, workplace, education, and healthcare).

1.2 Substantive rights access and the practice of human rights

Scholars have indicated that to minimize the gap between the passing of laws and rights and the actual practice of such rights for discriminated and marginalized communities, the rights need to intersect with social, economic, and political constructs such as colonialism, neoliberalism, authoritarianism, patriarchy, and classism. The substantive rights access framework allows us to understand the underlying mechanisms behind this gap and identify barriers to claiming and accessing rights (Glenn 2002; Kannabiran 2016; Anandhi and Kapadia 2017). Substantive access refers to the actual ability of groups to exercise their rights (Purkayastha 2020). Specifically, there is a need to examine the variety of conditions existing within institutional arrangements, patterns of interactions, and built environments that act as barriers to accessing legal rights. Scholars have noted that stigmatized communities encounter significant additional restrictions in public places (Glenn 2012; Anandhi and Kapadia 2017). These restrictions based on their hypervisibility in public places act as powerful mechanisms to ensure their ongoing marginalization (Armaline et al. 2015). Any discussion of substantive rights is therefore contingent upon understanding the forces that keep marginalized groups simultaneously hyper-visible and invisible. To ensure substantive rights access and practice there is a need to study the grassroots implementation of the policies. Out of the three landmark legal policies mentioned in Section 1.1, the NALSA judgment was a significant step forward in recognizing the rights of transgender and gender-diverse communities, and decriminalization of Section 377 was the next crucial step towards accepting individuals with diverse gender identities as persons and not as criminals. The 2019 Trans Act, the third legal reform, allows us to critically analyse the gap between legal rights and practice using the substantive access to rights framework. We build on Jain and Kartik’s (2020) pioneering work on the controversies surrounding the self-determination of gender identity, by critically analysing the Trans Act from the perspective of a transgender community (Table 1). To show the gaps and fissures between rights as written and rights that are accessible substantively, we focus on the constant struggles around how stigmatized communities claim and access their human rights of being recognized, not discriminated against, and enjoy right-based opportunities for their sustainable development across institutional spaces—family, educational, workplace and health spaces.

2. Research design, data, and analytic framework

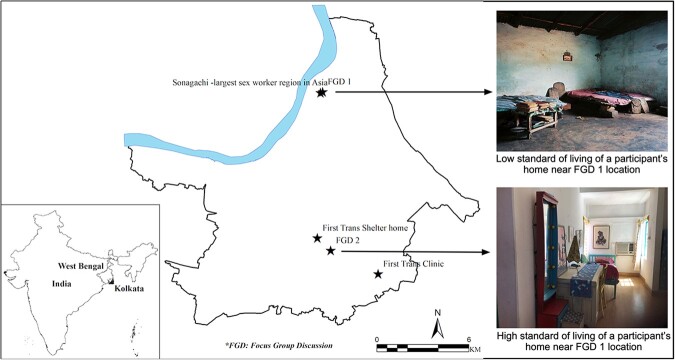

We focus on the non-binary gender communities of Kolkata, one of the four densely populated metropolises of India (Fig. 2). Though approximately 25,000 unidentified non-binary people reside in Kolkata, only 1,426 enrolled for voting (Javed and Chakraborty 2019). This wide gap between non-binary registered voters versus unidentified non-binary people in Kolkata is due to discrimination and stigma towards the marginalized gender-diverse communities—further magnified by intersections of patriarchy, class, social, and economic inequalities. The city, however, has also recently witnessed significant NGO-based movements (Samabhabona, Pratay GenderTrust, SAPPHO forEquality) for the LGTBIQ+ communities. In 2020, the State’s first health clinic exclusively for the transgender community was inaugurated following the establishment of the first transgender ‘shelter home’ (Ghosh 2020; Yengkhom 2020).

Figure 2.

Map showing focus group discussion sites and locations of relevance for trans persons in Kolkata, India.

To critically analyse the changes to the 2019 Trans Act on non-binary people’s struggles to access rights from the perspective of community members, we conducted two focus groups discussions (FGDs)6 from December 2019 to January 2020, with ten participants at a site in North Kolkata and five participants at a second site in South Kolkata (Fig. 2). The 15 participants were part of a larger multiyear research project titled SHAKTHI—Studying Healthcare Accessibility among Kothi, Transgender, and Hijra Individuals. The background and details of the SHAKTHI project are described in Bhattacharya and Ghosh 2020. The eligibility criteria for study participants were as follows: 1) individuals who self-identified themselves as a hijra, kothi7, or a transgender; 2) 18 years or older; 3) living in Kolkata, and 4) able to provide consent for the procedures of the study.

Participants were recruited by a combination of methods including targeted advertising, word of mouth, and snowball sampling techniques. Although these methods are well suited for reaching hard-to-reach populations such as the gender-diverse communities in Kolkata, they may increase the selection bias in research (Meyer 1995; Harcourt 2006). Advertisements and flyers about the study were posted on social media, community-based WhatsApp and Facebook groups, at LGBTIQ+ themed cafes, and distributed among community leaders. More details on data collection and FGD sites can be found in Becoming An Ally and Understanding the Geographies of Gender Identity: Lessons from Fieldwork (Bhattacharya 2021).

The sites of the FGDs were selected carefully to draw participants from regions with differences in socioeconomic and cultural practices between the northern and the southern neighbourhoods of the city (Sengupta 2010; Haque et al. 2020). Asia’s largest sex-work district, Sonagachi, where several of our study participants live and/or work is located in North Kolkata (Fig. 2). The participants were 18 years or older and 75 per cent had a high-school education or beyond (Table 2). The majority of the participants (53 per cent) identified themselves with more than one non-binary gender identity such as hijra, kothi, and transgender, while only two participants identified themselves as hijra (Table 2). Some participants were activists who were engaged in the national protests that led to the decriminalization of Section 377 and critical amendments to the current Trans Act. Out of the 15 participants, while none of them fully supported the Trans Act; 10 per cent supported ‘Prohibition against discrimination’ (sub-clause 3 of clause 8) indicating that discrimination has somewhat reduced across institutional spaces, and the majority criticized clause 4 on ‘Right to self-perceived gender identity’ and ‘Offence and Penalties’. These clauses denied the community their gender identity and the justice of proper penalties for sexual offences committed against them (see Table 1 for the details of these clauses from the Act).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants (N = 15)

| Demographic Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |

| Kothi (only) | 2 (13.3) |

| Transgender (only) | 5 (33.3) |

| More than one identity (HKTD)a | 8 (53.3) |

| Educational Qualification | |

| Non-Literate | 1 (06.7) |

| Secondary Schoolb | 3 (20.0) |

| High Schoolc | 4 (26.7) |

| College and above | 7 (46.6) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single or Never Married or Divorced | 7 (46.6) |

| Married or Partnered | 3 (20.0) |

| Multiple Partners | 5 (33.3) |

| Age (in years) | |

| 18–29 | 4 (26.7) |

| 30–39 | 6 (40.0) |

| >= 40 | 5 (33.3) |

| Employment Type | |

| Unemployed | 2 (13.3) |

| Employed (Self-employed, Sex work)d | 10 (66.6) |

| Traditional Jobs (Badhai, Logon, Cholla)e | 3 (20.0) |

| Monthly Income (in INR) f | |

| Low (5,001–7,500) | 1 (06.7) |

| Low Medium (7,501–10,000) | 5 (33.3) |

| Medium (10,001–20,000) | 3 (20.0) |

| High Medium (20,001–50,000) | 4 (26.7) |

| High (>= 50,001) | 2 (13.3) |

Notes: a= HKT—Hijra, Kothi, and Transgender.

= Secondary School refers to 10–12 years of education from primary to 10th standard.

= High School refers to 12–14 years of education from primary to 12th standard.

= Employed including self-employment and informal sex work.

= Badhai refers to profession of offering blessings via singing and dancing at childbirth, opening ceremonies of businesses; Cholla refers to begging on the street, train compartments; Logon refers to the profession of singing and dancing at weddings.

= 1 INR is 0.013 USD; 50,000 INR is 70 USD (exchange rate).

We draw from the detailed account of the FGDs to analyse the perceived impact of the changes to the 2019 Trans Act on a transgender community in Kolkata using a substantive rights framework (Section 1.2). Specifically, we attempt to understand the social, economic, and political mechanisms leading to the gaps between the passing of the legal rights legislation and actual access to, and practice of, these rights in institutional spaces—family, educational, workplace, and health spaces.

3. Discussion

3.1. Substantive access and practice of human rights across institutional spaces

A transgender or a gender-diverse person experiences stigma and discrimination in every sphere of life (Chakrapani et al. 2017), from family members, at school (Palkki and Beach 2016), work, and in other public interactions. It has been emphasized in subclause 3, clause 2 of the Act that ‘No person or establishment shall discriminate against a transgender person’. So, how did a transgender community experience access to rights in institutional spaces post the Trans Act? In this section, we answer this question from the perspective of our study participants and their lived experiences. Including the lived experiences also supports our argument on understanding structural mechanisms, intersections, and barriers to accessing social, economic, and healthcare rights that inform human rights practice in institutional spaces.

3.1.1 Family and relationship spaces

Our study participants expressed that they were rarely accepted by their family members, despite their legal rights. A participant (hijra) in their late 40s, indicated that even when being the sole contributing wage earner in the family, they were still not accepted as an equal member of the family, except by their mother. After the mother’s death, the participant’s father, ruthlessly, asked them to ‘look like a man’ by removing lipstick and feminine clothes before accompanying him to collect the death certificate. Other participants recounted various instances of being rebuked by their fathers, brothers, and other male family members, reaffirming the psychological toll that hegemonic patriarchy can take on a hijra even in private family spaces. Some participants lamented that their relationship with their family was based solely on their ability to provide financial support. So much so that often participants’ brothers or fathers would take their money to organize social gatherings such as prayer ceremonies or marriages, but they would not be invited or welcomed to those events. Participants were frequently scorned during events they hosted—they noted with sorrow that sometimes they consciously left these social events to avoid being mocked by their family members. Transgender minors below 18 years old are enforced to cohabit with their natal family by the Act (Table 1), which leads to more violence, neglect, and trauma. It is quite evident that the Act did not ensure the practice of non-discrimination by the family members in spite of a clause requiring this (subclause 12 (c) of clause 5).

This inability to access safe environments in a family is extended to partners or other intimate relationships. Almost 50 per cent of the participants were single, while approximately 30 per cent had multiple partners (Table 2); the latter were often unstable relationships. Given the present religious and cultural conventions guiding marriage laws in India, transgender and gender-diverse people often fall outside these heteronormative conventions and are left with few social supports for their marriages (Zivi 2014).

The Act has a subclause, 3(g) of clause 2, that states ‘the denial or discontinuation of, or unfair treatment regarding the right to reside, purchase, rent, or otherwise occupy any property’ by an institution or a person was prohibited. However, our participants still cannot inherit their parent’s property seamlessly as they face legal barriers when asked to document their gender identity. They do not have the valid verification of their gender identity required to inherit documents nor did they know what undocumented individuals should show within the existing inheritance laws; leaving them ineligible to inherit their parents’ property (Misra 2009; Kumari 2019), and most often end up being homeless. This brings us to another controversial clause (4) of this act: the right to ‘self-perceived’ gender identity (Table 1). As explained by Jain and Kartik’s (2020), and criticized by several gender and sexual rights activists, a huge gap exists between the right of self-affirming one own’s gender identity and how this right is practised in reality, for example when inheriting ancestral properties. Gender identity is not formalized without a certification by the District Magistrate (DM) and proof of sex reassignment surgery (SRS). The DM—as a paternalistic and bureaucratic gatekeeper with the authority to determine an applicant’s gender identity—is thus positioned at direct odds with the constitutionally protected tenets of autonomy and self-determination. The contradictions between self-affirmation or self-recognition of gender and the administrative process for ‘formal proof of recognition’ show the differential nature of citizenship granted to non-binary people, who must rely on the State to verify their gender identity. This goes against the right to dignity and bodily autonomy, puts an additional burden on their health costs, and forces them to go through painful and often corrupt bureaucratic processes. Our FGD participants expressed anxiety and scepticism around these gaps and contradictions.

3.1.2 Educational space

‘Every educational institution shall provide inclusive education and opportunities for sports, recreation, and leisure activities to transgender persons without discrimination on an equal basis with others’, according to subclause 13 of clause 6 of the Trans Act. The participants reflected that even after several years had passed since this Act was formulated in 2014, the schools did not include sex education regarding non-heterosexual identities in their curriculum nor were there provisions for the introduction of transgender characters as role models in primary or secondary schools (Raj 2017). Several participants mentioned that due to a lack of proper information and knowledge, minors struggled to understand and accept their non-binary sexualities and gender identities. Schools not only failed to make them aware of their own sexual identities but created a situation for stigmatization, psychological issues, and barriers to growth and development (Bhattacharya and Ghosh 2020). Participants also reported sexual abuse and harassment at schools, which was their primary reason for leaving education at an early stage (Palkki and Beach 2016). For most participants, the lack of awareness of diverse gender identities and sensitivity among peers and teachers made school a bad experience—leading to high dropout rates. The Act very vaguely addressed discrimination in school, with no mention of protection against sexual abuse and violence, which students faced constantly. The participants anticipated that the role of educators would be crucial to implementing the non-discriminatory laws and mediating the mechanisms of legal rights to substantive access and practice of rights for creating an inclusive environment at educational institutions.

In typical local schools, feminine boys will be molested. Will the teacher say that there are laws that protect them and prohibit such abuses? At the most, the teacher will beat the boy who played the prank— It will depend on the liberal mindset of the teacher to practice the anti-discriminatory laws. (42-year-old college graduate who self-identified with more than one gender identity.)

Subclause 14 of clause 6 of the Trans Act mentions the necessity to ‘formulate welfare schemes and programs to facilitate and support livelihood for transgender persons including their vocational training and self-employment’. A participant reflected that they do not want vocational training such as designing and tailoring clothes, rather they emphasized the need for education such as that provided to cisgender individuals, which could allow them to obtain jobs of their preference.

If you do not educate trans persons, how will you give them jobs? If I do not have an equal level of education, how do I compete for corporate jobs with a cisgender individual? Does creating jobs in a candle company, or giving out sewing machines make a difference? This is a very old idea. Employment generation is making employment available in all sectors and for that inclusive education and training are required from the early stages. If that is not provided, how will we get jobs? (40-year-old college graduate, earning more than 50,00 INR per year, and self-identified with more than one gender identity.)

3.1.3 Workspace

The norms and structures that keep transgender and gender-diverse people invisible and marginalized within their homes and schools catapult them to hypervisibility in workplaces. Though the Act has provisions for job security, when it comes to substantive access to jobs they are rarely accepted into mainstream work arenas. Without alternatives, many end up in culturally rooted occupations like badhai,8chola,9logon,10 and kharja.11 Badhai and logon are considered auspicious following centuries-old traditions and yet are still stigmatized. Among the 15 FGD participants, 66 per cent were involved in self-employment and kharja (sex-work), and 20 per cent in the traditional jobs of badhai, logon, and chola (Table 2). The 2016 version of the Act proposed punitive measures for chola (begging). The subclause 18 (a) of clause 8 of the Trans Act stated that ‘Whoever (a) compels or entices a transgender person to indulge in the act of begging or other similar forms of forced or bonded labor other than any compulsory service for public purposes imposed by Government’ will be criminalized. Framing begging as a ‘bonded labor’ is important discursively and performatively because it threatens to erase the history of hijras in India. The hijra community in India has historically lived as gharanas (big family) and each of the gharana members contributed financially for the sustenance of the gharana (Tapasya 2020). The gurus (mentor) train young chella (apprentice) hijras on how to ask for chola (alms) at several cultural occasions, and at trains, bus stops, and other landmark locations (Goel 2018; Sinha 2019). Once trained and having started earning, chellas were included in a gharana culture and had the right to inherit property from their mentors. The criminalization of begging made it difficult to earn money via this guru-chella system, exposing all hijra households to the risk of criminalization (Saria 2019), and threatened to wipe out centuries-old cultural and traditional practices of bonding, social support, and social capital. The 2019 version of the act, however, decriminalized begging. While this step was in the favour of the hijra community (Table 1), members were concerned about the continued policing and harassment, indicating a disconnection between the formulation of law and its fair implementation. As one participant reported, ‘It has not been said that just because begging has been de-criminalized, the police cannot harass the chollawalis [beggars]. There is too much ambiguity in the language of the new act’ (40-year-old college graduate, earning more than 50,00 INR per year, and self-identified with more than one gender identity).

Even after begging is decriminalized, heavy reliance on other traditional jobs adds to the struggles of everyday lived experiences of stigma, discrimination, and violence. Policing often undermines a transgender person’s livelihood. Their only access to earning a living via traditional jobs is often curtailed by strict policing along with the unfair burden of bribing police for continuing with those occupations, leaving most people mired in poverty and debt.

Then there are the middle-class trans persons, who are stuck in between. Given the families we come from, we cannot do cholla [begging] on the street or openly perform sex work because it would disturb our middle-class family’s norms and reputation. The middle-class trans community is in bad shape. We cannot undergo castration to become a hijra and do badhai or logon, nor can I practice khajra [sex-work] openly. Neither do we get jobs easily as we do not have an education. (42-year-old college graduate who self-identified with more than one gender identity, also a gender activist.)

Discrimination and policing at workplaces often intersect with class-based stigma. A typical middle-class12 family in India looks down upon jobs such as begging or prostitution, not for economic reasons but because these activities would negatively affect the family’s reputation among their peers. Community members born in middle-class families, who have little or no education, are likely to face severe financial hardships. They are hesitant to beg due to family pressure and unable to acquire mainstream jobs with no education and due to their non-binary gender identity. The Trans Act failed to recognize discriminatory experiences intersecting with caste and class, a complex underlying mechanism of Indian society. The lack of such intersectional perspectives within the Act makes it a failure regarding substantive access to rights.

Inaccurate perceptions of the larger society, rooted in heteronormative norms and cultures, about the impact of the Act on the gender-diverse community may have caused new problems for transgender and hijra communities. With the passage of the act, cisgender people now think that the State has provided gender-diverse communities with adequate resources, and that, therefore, they do not need to be paid for badhai or cholla. For example, a trans woman participant was paid less than the female prostitutes for soliciting sex work. Participants complained about the lack of safe spaces for solicitation of sex work online and in person. They compared their situation with the sex workers in Thailand who used designated spaces such as sex clubs where clients had to swipe their credit cards before engaging in any sexual activity. This setting minimizes exploitation, ensuring safe sex and fair deals, a recommendation that the participants suggested should happen in India through direct government interventions for creating safe spaces and reliable payment methods13 (see Section 4 for more details).

It is quite evident that non-binary people have a very limited set of job options—access to traditional occupations (such as logon, cholla, and badhai) are dwindling, a heavy presence of police and rules around these occupations making it harder for them to earn a living, and little or no education for acquiring other types of mainstream jobs. Such challenges intersect with major social barriers such as gender disparity, police harassment, patriarchy, and classism. If a person on a spectrum of non-binary gender identity is not affirmatively included in other types of employment, traditional means of earning will remain dominant by default and keep adding to the perils of exclusion, poverty, debt, and lack of empowerment.

3.1.4 Healthcare spaces

As non-binary people navigate healthcare institutions, accessing basic healthcare needs can be fraught with challenges and discrimination. Even though the Trans Act directs healthcare spaces to recognize non-binary people and their health needs, few health centres have built infrastructure and invested in resources with the community in mind (Reddy 2018). Encounters with health professionals, who are rarely trained in gender-sensitive healthcare practice, can be humiliating. Such experiences magnify the stigma that they experience in healthcare spaces. Participants recounted several experiences that they had in healthcare centres even after the Trans Act was passed with a clear clause on the prohibition of discrimination in the health sector (subclause 15 of clause 6).

My community friend went to a dermatologist, who treated my friend like an untouchable. The way a dermatologist touches and examines a cisgender person is different for us—the doctor kept a distance from my friend and refrained from examining them physically. When a trans patient attempts to sit near the reception in the waiting area, they were asked to move back. This happened just last year. From the moment they understand I am a trans person, other cisgender patients start behaving differently, making doctors’ offices and health institutions uncomfortable spaces. (A 31-year-old transgender woman with primary school education, and employed.)

Trans patients used to be harassed more, but since we started demanding transgender [hospital] wards the harassment has lessened. Previously it was more, but it has reduced comparatively. The awkward glances and expressions from the healthcare providers when they see a hijra or a trans woman clad in a sari [traditional Indian garment] have lessened over time. (A 31-year-old transgender woman with high school education, and unemployed/looking for jobs.)

A transgender person’s survival and wellbeing are contingent upon access to and utilization of healthcare services. The mixed impact of legal reforms on this basic human right was a vital discussion topic among the participants. Some participants acknowledged that due to the Act there has been some achievements in terms of their healthcare, but these improvements have been concentrated only in HIV care at the Integrated Counseling and Testing Centers (ICTC). ICTC HIV centres tend to be the most LGBTIQ+ friendly because of the presence of counsellors and the role of the NGOs and community-based organizations (CBOs), although sometimes the State neglects to acknowledge the contributions of the NGOs. ICTC is just one sector; State intervention is therefore necessary for providing wide-ranging diverse gender identity friendly healthcare services. For instance, binary male-female hospital wards reflect heteronormative principles of gender categories. The lack of hospital wards for transgender and hijra patients and undertrained healthcare providers, top the list of healthcare concerns for the community. When trans women are admitted in a male ward, the patients often become victims of sexual harassment, whereas in female wards they were objects of disgust and ridicule. This leads to microaggression among non-binary patients and worsens their overall health and well-being. To mitigate such stresses, non-binary patients would prefer private wards, but currently, these are too expensive or unavailable in public hospitals. The 2019 Trans Act also mentioned the inclusion of medical care facilities such as ‘sex reassignment surgery and hormonal therapy counseling’ (subclause 15 (d) of clause 6). One public hospital opened a unit for transgender patients to offer these services (Yengkhom 2020) , but participants noted several risks to receiving the service from that particular hospital.

The lived experiences of the participants across institutional spaces—family, education, work, and healthcare—show that legal rights alone will not ensure that gender-diverse people have access to the conditions that human rights aim to secure for them. More specifically, these experiences highlight the need for guidelines emphasizing praxis that will ensure substantive access to rights.

4. ‘What we got and what we desired’: achievement, failures, and recommendations

Participants expressed mixed opinions about the impact of the changes included in the Trans Act in 2019. Some claimed that the Act was a step forward in their fight for rights, while others indicated that the Act caused more problems. Below we highlight achievements and negative experiences the community faced while claiming their rights.

One positive consequence that stemmed from the continued struggle of the community in claiming their rights is greater access to heteronormative spaces with relatively less discrimination.

In terms of safe space, previously our interactions were restricted to only hidden places around parks and lakes; despite bad weather or pests, we had to hang out in these zones. But now we have queer cafés. Though few, there exists some safe spaces for the community.14 (A 39-year-old kothi, primary school educated, and working at an HIV/AIDS counselling centre with a salary of 30,000 INR per year.)

The pride parades have made the LGBTIQ+ communities visible in a less discriminatory way—rather than being strange/queer—across public spaces in Kolkata (and other parts of India). Trans women can now wear feminine make-up and clothes and roam around in popular heteronormative spaces with less public harassment. After the decriminalization of Section 377 and the passage of the right to ‘self-perceived gender identity (clause 4 in the Trans Act), transgender people can now disclose their sexual orientation without fear and can, therefore, discuss appropriate healthcare needs. Although not fully practised as desired, both law enforcement and cisgender people are aware that discrimination against a non-binary person including the denial of service or unfair treatment to education, employment, healthcare, and housing, is prohibited by the law. The recent legal reforms also provided NGOs with more opportunities to directly support and work with gender-diverse communities. NGOs have played a key role in both claiming rights through activism and substantively accessing the rights. Participants reported that in general, NGOs have provided strong support in employment generation, in increasing empowerment at the grassroots level, and in the creation of safe spaces, although a few were sceptical about the motivation of some NGOs.

Major gaps, however, remain in transgender and gender-diverse person’s economic and social needs and representation, the three distinct forms of intersectionality (Crenshaw 1991). Typically, when political rights are achieved through legal means, their impact on substantively accessing social and economic rights in public and private spaces takes much longer; often delayed by barriers. For instance, as with other neoliberal solutions to structural problems, services (mentioned above) offered via NGOs to meet transgender person’s economic and social needs do not create significant changes.

I was told that a person from a low caste (Dalits) has been oppressed for a long time, kept as outcasts and so without affirmative action, this group could not have prospered. I have known from previous generations that we [trans persons] have been oppressed forever. Therefore, we need reservations too. More support and reservation should be given to a rural trans person, who faces more discrimination than us living in the urban areas. To bring social equality, you need to bring structural changes and reservations for the transgender community. (42-year-old college graduate who self-identified with more than one gender identity, also a gender activist.)

Non-binary communities’ demand for reservations is similar to the other lower caste groups in India, which is based on their historical and ongoing social and economic marginalization. This has not been fulfilled in the current Trans Act. This lack of reservation also speaks for the inability to access rights at institutional spaces, such as workspaces, which is in turn due to the inadequate representation of non-binary people in positions of power and a lack of effort to bridge the existing gap in rights access.

Our FGD participants also expressed concern about their safety. As discussed in detail in the previous section, the law to decriminalize begging, one of their traditional means of earning, is a start. However, community members were apprehensive about police harassment and their inability to claim their rights. The subclause 18 (d) of clause 8 on punishment for sexually harassing a trans person is unequal and discriminatory when compared to that protecting a cisgender individual. The following was remorsefully quoted by one of our participants:

Someone in the neighbourhood molests me, sexually assaults me, and this person gets arrested for only two years. For assaulting cisgender women, the term is seven years. Does a trans woman feel less pain while being raped and that whoever is guilty of raping them, their punishment should be reduced to just two years? (42-year-old college graduate who self-identified with more than one gender identity, also a gender activist.)

In India, when a woman or a child is sexually abused, the legal punitive measure can be as severe as a life sentence or in some cases, even the death penalty. The lesser punishment for similar crimes against non-binary people suggests that trans lives are disposable and of less value.

4.1. Recommendations for substantive access to human rights and praxis

We need social acceptance, employment, and rights to live with utmost dignity. I am not claiming that it will happen overnight. In the past few years, I have observed a trend toward partial representation—and I encourage that shift. Something is better than nothing. Empowerment, respect, and access in all sectors of society are all that we desire. (42-year-old college graduate who self-identified with more than one gender identity, also a gender activist.)

From the human rights practice lens and the lived experiences accounted by our study participants, we know that establishing rights and recognition does not guarantee access to human rights. How can we substantively access rights then? We list several recommendations below based on the perspectives of our study participants, criticisms from the activists, and our interpretations of the act.

The first and most important recommendation is the need for educational equity. Enforcement of the prohibition of discrimination at educational spaces must be ensured so that non-binary youth and adults have equal access to educational opportunities in an inclusive and safe environment. Only education will equip them to become competent for mainstream jobs in place of their traditional occupations; a chance to break free from the shackles of poverty and discrimination. Second, more emphasis should be given to improving the school curriculum. A few participants suggested including transgender stories and characters and gender studies in elementary and middle school curricula to create awareness and normalize the existence of non-binary gender identities at an early stage. They mentioned that they were not aware of their non-binary gender identity even as teenagers, which made coming out as a non-binary person difficult. These experiences led them to recommend the need for counsellors in schools to help and support transgender and gender-diverse students, thereby reducing high dropout rates.

Third, in line with the perspective of our participants, we recommend the introduction of non-binary gender specific healthcare training within the existing medical curriculum for healthcare providers, allowing more sensitivity and understanding of nuanced healthcare needs for people with overlapping and diverse gender identities. Healthcare providers need practical training and awareness to interact effectively with non-binary patients; such training will be key to creating substantive access to health rights. The Act does have a clause on ‘review of medical curriculum and research for doctors to address trans specific health issues’ (subclause 15 (e), clause 6), but missed specifying the need for sensitivity training. There is a popular belief that non-binary patients’ healthcare needs consist entirely of SRS. However, the health of patients on a gender spectrum should encompass other critical health issues and comorbidities such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. Similarly, physical, mental health, and substance misuse disorders are also neglected (Bhattacharya and Ghosh 2020; Srivastava et al. 2020). Thus, the provision of medical curricula needs to be improved in the next revision of the act.

Fourth, some participants argued that instead of focusing on providing free yet poor-quality treatment, the government should consider providing inclusive and budget-friendly health insurance to non-binary persons. This will incentivize healthcare providers to provide quality treatment. To them, quality of healthcare is more important than free healthcare. The Act does have a provision on health insurance—‘provision for coverage of medical expenses by a comprehensive insurance scheme for Sex Reassignment Surgery, hormonal therapy, laser therapy or any other health issues of transgender persons’ (subclause 15 (g), clause 6)—but as the participants reported, it was just a legal right on paper and no progress had been made in terms of substantively accessing this right.

Fifth, we all need to support our non-binary friends and family members at home. If a transgender or a hijra person is supported at home, fighting societal discrimination might become a little easier for the community members. Along with the need for counsellors at schools, there is also a need for counsellors for parents of transgender youth, who have little clarity and information about their child’s gender identity, and limited experience on how to support them (Newcomb et al. 2018).

Sixth, a more inclusive and helpful act could have been passed if more community members were involved in the process of formulating and amending the act. For example, although the Trans Act prohibits discrimination against a transgender person in education (subclause 3(a) of clause 2), employment (subclause 3(b, c) of clause 2), and in renting or buying a property (subclause 3(g) of clause 2), there is no penalty specified for failure to adhere to these protections, making the Act substantively ineffective. The Act does not mention civil rights such as marriage, adoption, and social security benefits, and it fails to provide clear directives about economic and social rights. Therefore, in terms of documented legal rights, the recognition of non-binary people is an important step forward, but in practice, the Act is limited in its substantive improvements to the lives of people on a gender spectrum within families, schools, workplaces, and healthcare spaces.

5. Conclusion

Continued activism and struggles to claim rights led to the passage of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act and the institutionalization of human rights and citizenship for communities with non-binary gender identities. The voices of the hard-to-reach and marginalized community members, however, tell a different story. The journey from legal rights to substantively claiming rights remains unfinished well after the establishment of rights, often blocked by structural and institutional barriers set up by heteronormative norms and cultures. Non-discrimination based on gender identity is a political right, yet that right is not substantively guaranteed for non-binary people; they continue to encounter barriers to their economic, social, and cultural rights across institutional spaces. In this article, we discussed the achievements and failure of the Trans Act from the perspective of a transgender community in India. They vividly narrated their lived experiences and challenges in claiming their rights; highlighting why the legal institutionalization of rights alone has an insufficient impact on the conditions of their lives and security. The accounts of the participants describing their erasure and hypervisibility across family, occupation, education, and healthcare spaces and institutions, show the gaps between achieved legal status, the promises of laws, and the practical realities on the ground. The different forms of discrimination that gender-diverse groups face continually serve as significant impediments to substantive access to and practice of rights. Thus, their fight for substantive human rights involves a variety of strategic practices to normalize and publicize their presence and to claim equal treatment across institutions and spaces. This article provides several recommendations such as ways to improve educational equity; including gender studies in the school curriculum for developing awareness of non-binary gender identities from early ages; introduction of transgender specific training for healthcare providers; government provided inclusive and budget-friendly health insurance; providing more institutional support for families such as counselling for parents of non-binary youth; and, finally, increasing the adequate representation of non-binary people in positions of power to bridge the existing gap in right’s access. When political rights are achieved through legal means, the road to claim social and economic rights in public and private spaces cannot be achieved without overcoming the structural barriers of class, patriarchy, stigma, discrimination, inequity, and other norms of heteronormative society.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants for their time and involvement with the study. A special thanks to Amrita Sarkar (trans community leader), and the owners of the ‘Amra Godbout Café’ for providing support and a safe and comfortable venue for conducting focus group discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [K01DA037794] and the Department of Geography, University of Connecticut.

Conflict of interest statement. There is nothing to declare.

Footnotes

The Yogyakarta plus 10 was adopted on 10 November 2017 to supplement the Yogyakarta Principles. The Yogyakarta plus 10 documents emerged from the intersection of the developments in international human rights law with the emerging understanding of violations suffered by persons on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity, and the recognition of the distinct and intersectional grounds of gender expression and sex characteristics.

Transgender identity does not fully represent the diversity among non-binary identities in India. We use ‘transgender’ in this piece, cognizant of the fact that it is a Western term and does not adequately cover all gender-diverse identities in South Asia. South Asia uses several vernacular terms for gender identities as Meti in Nepal (Oestreich 2018), Ponnaya in Sri Lanka (Nichols 2010), and Hijra in India (Chhetri 2017). As this article aims to provide critical analysis of the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of India, we are using the same term used in the Act. In Pakistan, another South Asian country, the term ‘transgender’ is also used in a similar Act, The Transgender Person’s (Protection of Rights) Act.

We understand ‘South Asia’ in geographical, cultural, political, and linguistic terms and acknowledge that South Asia is not a homogeneous entity and that the LGBTIQ+ movements within the region (specifically in Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bangladesh) have their own histories and cannot all be analyzed through the same lens.

Hijras are biologically male but express their gender identity through living as women and performing rituals rooted in cultural history, at weddings and childbirth (Nanda 1998).

In South Asian countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, individuals with non-normative gender identities such as hijra and transgender are referred to as ‘third gender’ in the census and other official government documents.

The study is approved by the University of X’s (name hidden during peer review) Institutional Review Board.

Kothi is a category for socioeconomically marginalized gender variant or ‘feminine’ same sex desiring men, who gained visibility within the emerging institutional movement for LGBT rights in the late 1990s (Gill 2016).

Badhai is the ritual where hijras sing, dance, and bless a newborn child or a newly married couple.

Cholla refers to begging on streets, at traffic signals and in local trains. Individuals who practice cholla are called chollawalis.

Logon is performing dances at marriage parties for entertainment, which sometimes leads to sexual activities.

Khajra refers to sex work.

Middle class households in an Indian context describe a person living on $2–10 per day. When compared to the developed countries, this amount is very low but in India they are still better off than the poor, who live on less than $2 a day (Banerjee and Duflo 2008).

In Kolkata, sex workers have successfully organized a government-recognized workers union, ‘Darbar’. The demand for safe sex practices is now recognized. There are also accounts of union-building among trafficked persons in other countries (Purkayastha and Yousaf 2019; Lakkimsetti 2020).

The last decade was also marked by a proliferation of queer social spaces in cities like Kolkata and Delhi, paralleling the growing visibility of queer and transgender people and related issues in the media and public sphere. Kolkata, for example, now has two ‘cafes’ catering to trans and queer people and their allies: Amra Odbhut Cafe and Cafe #377. Amra Odbhut has been hailed as the only community space of its kind and as a groundbreaking example of resistance to socially imposed gender/sexual norms and identities, while Cafe #377 has been celebrated as a sign of the growing liberal acceptance of LGBTIQ+ people in Kolkata (Dutta 2020b).

Contributor Information

Shamayeta Bhattacharya, Shamayeta Bhattacharya (First Author) is a PhD candidate in Geography, at the University of Connecticut, USA. Her research interest includes health and gender geography, human rights, postcolonial queer literature, and South Asia.

Bandana Purkayastha, Bandana Purkayastha (Third Author) is Professor of Sociology and Asian & Asian American Studies, University of Connecticut, USA. She has published extensively on human rights, intersectionality, transnationalism, migrants, violence, and peace.

References

- Anandhi S., Kapadia K.. 2017. Dalit Women: Vanguard of an Alternative Politics in India. London: Taylor & Francis. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315206493/dalit-women-anandhi-karin-kapadia. [Google Scholar]

- Armaline W. T., Glasberg D. S., Purkayastha B.. 2015. The Human Rights Enterprise: Political Sociology, State Power, and Social Movements. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aswani D. 2020. Transgender Neutrality of Sexual Offences: An Aftermath of Decriminalization of Section 377. National Law University Delhi (India), 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A. V., Duflo E.. 2008. What is Middle Class about the Middle Classes around the World? Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(2): 3–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Guha S.. 1997. Medium Towns or Future Cities. In Diddee J. (ed.), Indian Medium Towns: An Appraisal of Their Role as Growth Centres. New Delhi: Rawat Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baxi U. 2007. The Future of Human Rights – Upendra Baxi. Oxford India. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S. 2019. The Transgender Nation and Its Margins: The Many Lives of the Law. South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 20(20): 1–19. DOI: 10.4000/samaj.4930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S. 2021. Becoming an Ally and Understanding the Geographies of Gender Identity: Lessons from Fieldwork – ProQuest. Geographical Bulletin 62 (2A): 72–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Ghosh D.. 2020. Studying Physical and Mental Health Status among Hijra, Kothi and Transgender Community in Kolkata, India. Social Science and Medicine 265. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazenave N. A. 2018. Killing African Americans: Police and Vigilante Violence as a Racial Control Mechanism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V., Vijin P. P., Logie C. H.. et al. 2017. Assessment of a ‘Transgender Identity Stigma’ Scale among Trans Women in India: Findings from Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses. International Journal of Transgenderism 18(3): 271–81. DOI: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1303417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chua L. J. 2019. The Politics of Love in Myanmar: LGBT Mobilization and Human Rights as a Way of Life. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cossman B. 2018. Gender Identity, Gender Pronouns, and Freedom of Expression: Bill C-16 and the Traction of Specious Legal Claims. University of Toronto Law Journal 68(1): 37–79. DOI: 10.3138/utlj.2017-0073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. 1991. Stanford Law Review Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dicklitch-Nelson S., Thompson Buckland S., Yost B., Draguljić D.. 2019. From Persecutors to Protectors: Human Rights and the F&M Global Barometer of Gay Rights TM (GBGR). Journal of Human Rights 18(1): 1–18. DOI: 10.1080/14754835.2018.1563863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A. 2020a. The End of Criminality? The Synecdochic Symbolism of §377. NUJS Law Review 3: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A. 2020b. Beyond Prides and Cafes: Exploring Queer Spaces in Non-Metropolitan Bengal. Groundxero: Facts as Resistance. 5 February. https://www.groundxero.in/2020/02/05/beyond-prides-and-cafes-exploring-queer-spaces-in-non-metropolitan-bengal/. Referenced 11 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Farrior S. 2009. Human Rights Advocacy on Gender Issues: Challenges and Opportunities. Journal of Human Rights Practice 1(1): 83–100. DOI: 10.1093/jhuman/hup002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh B. 2020. First-Ever Shelter for the Transgender Opens in Kolkata. The Hindu. 26 August.

- Gill H. 2016. Kothi. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1–2. DOI: 10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn E. N. 2002. Unequal Freedom How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn E. N. 2012. Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goel I. 2018. The Lifestyle of Hijras Embodies Resistance to State, Societal Neglect. The Wire. 12 April.

- Grinspan M. C., Carpenter M., Ehrt J.. et al. 2017. Additional Principles and State Obligation on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics to Complement the Yogyakarta Principles. The Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10. https://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/yp10/.

- Haque I., Rana M. J., Patel P. P.. 2020. Location Matters: Unravelling the Spatial Dimensions of Neighbourhood Level Housing Quality in Kolkata, India. Habitat International 99. DOI: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt J. 2006. Current Issues in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health. Journal of Homosexuality 51(1): 1–11. DOI: 10.1300/J082v51n01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman M. 2011. LGBT’s Pre-History: Democratic Inclusion and Homophile Citizenship Before Stonewall. Western Political Science Association 2011 Annual Meeting Paper. San Antonio, Texas, 21–23 April 2011.

- Ilkkaracan P. 2015. Commentary: Sexual Health and Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress or Backlash? Global Public Health 10(2): 268–70. DOI: 10.1080/17441692.2014.986173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D., DasGupta D.. 2021. Law, Gender Identity, and the Uses of Human Rights: The Paradox of Recognition in South Asia. Journal of Human Rights 20(1): 110–26. DOI: 10.1080/14754835.2020.1845129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D., Kartik K.. 2020. Unjust Citizenship: The Law That Isn’t. NUJS Law Review 2: 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Javed Z., Chakraborty M.. 2019. For 1,426 Transgenders in West Bengal, This Election is a Great Leveller | Kolkata News - Times of India. Times of India. 5 May. [Google Scholar]

- Kannabiran K. (ed.). 2016. Violence Studies. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R. 2019. Socio-Cultural Elimination and Insertion of Trans-Genders in India. IJRAR-International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 6(2): 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkimsetti C. 2020. Legalizing Sex: Sexual Minorities, AIDS, and Citizenship in India. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loh J. U. 2018. Transgender Identity, Sexual versus Gender “Rights” and the Tools of the Indian State. Feminist Review 119(1): 39–55. DOI: 10.1057/s41305-018-0124-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H. 1995. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men Author. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36(1): 38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. 2011. Census of India Website: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. https://censusindia.gov.in/

- Misra G. 2009. Decriminalising Homosexuality in India. Reproductive Health Matters 17(34): 20–8. DOI: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34478-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda S. 1998. Neither Man nor Woman. The Hijras of India. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co. DOI: 10.1300/J082v11n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M. E., Feinstein B. A., Matson M.. et al. 2018. ‘I Have No Idea What’s Going on out There’: Parents’ Perspectives on Promoting Sexual Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adolescents. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 15(2): 111–22. 10.1007/s13178-018-0326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nownes A. J. 2019. Organizing for Transgender Rights: Collective Action, Group Development. State University of New York Press.

- Palkki J., Beach L.. 2016. ‘My Voice Speaks for Itself’: The Experiences of Three Transgender Students in Secondary School Choral Programs. Doctoral thesis, University of Michigan. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.3195.2881. [DOI]

- Parker R. G. 2007. Sexuality, Health, and Human Rights. American Journal of Public Health 97(6): 972–3. DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips B. 2014. Letter from Toronto: Post-World Pride 2014 Reflections on LGBTQ Art and Activism. Journal of Human Rights Practice 6(3): 511–21.DOI: 10.1093/jhuman/huu016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purkayastha B. 2020. The Unfinished Journey from Suffrage to Substantive Human Rights: The Continuing Journey for Racially Marginalized Women. Western New England Law Review 42(3): 32. [Google Scholar]

- Purkayastha B., Yousaf F. N.. 2019. Human Trafficking: Trade for Sex, Labor, and Organs. Medford, MA, USA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raj S. 2017. Absence of Transgender in Curriculum. International Journal of Research Culture Society 1(10): 221–7. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. 2018. Paradigms of Thirdness: Analyzing the Past, Present, and Potential Futures of Gender and Sexual Meaning in India. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 5(3): 48–60. DOI: 10.14321/qed.5.3.0048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saria V. 2019. Begging for Change: Hijras, Law and Nationalism. Contributions to Indian Sociology 53(1): 133–57. DOI: 10.1177/0069966718813588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney A., Grover S.. 2019. The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill 2019 Divergent Interpretations and Subsequent Policy Implications. Indian Journal of Law & Public Policy 6(1): 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz P. 2019. ‘“To Me, Justice Means to Be in a Group’: Survivors’ Groups as a Pathway to Justice in Northern Uganda. Journal of Human Rights Practice 11(1): 171–89. DOI: 10.1093/jhuman/huz006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semmalar G. I. 2017. First Apathy, then Farce: Why the Parliamentary Report on Trans Persons’ Rights is a Big Joke. The News Minute.

- Sengupta U. 2010. The Hindered Self-Help: Housing Policies, Politics and Poverty in Kolkata, India. Habitat International 34(3): 323–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha C. 2019. ‘We can’t erase our hijra culture’ – India Today Insight News. India Today. 19 July.

- Srivastava A., Sivasubramanian M., Goldbach J. T.. 2020. Mental Health and Gender Transitioning among Hijra Individuals: A Qualitative Approach Using the Minority Stress Model. Culture, Health and Sexuality 17(3): 1–15. DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1727955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapasya. 2020. What Does India’s Transgender Community Want? The Diplomat. 9 January.

- Yengkhom S. 2020. A Step Forward: Third-Gender Patients get Exclusive Clinic in West Bengal | Kolkata News –Times of India. Times of India. 28 February.

- Zivi K. 2014. Performing the Nation: Contesting Same-Sex Marriage Rights in the United States. Journal of Human Rights 13(3): 290–306. DOI: 10.1080/14754835.2014.919216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]