Abstract

Background

The evidence on what strategies can improve recruitment to clinical trials in maternity care is lacking. As trial recruiters, maternity healthcare professionals (MHCPs) perform behaviours (e.g. talking about trials with potential participants, distributing trial information) they may not ordinarily do outside of the trial. Most trial recruitment interventions do not provide any theoretical basis for the potential effect (on behaviour) or describe if stakeholders were involved during development. The study aim was to use behavioural theory in a co-design process to develop an intervention for MHCPs tasked with approaching all eligible potential participants and inviting them to join a maternity trial and to assess the acceptability and feasibility of such an intervention.

Methods

This study applied a step-wise sequential mixed-methods approach. Key stages were informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT) Taxonomy to map the accounts of MHCPs, with regard to challenges to trial recruitment, to theoretically informed behaviour change strategies. Our recruitment intervention was co-designed during workshops with MHCPs and maternity service users. Acceptability and feasibility of our intervention was assessed using an online questionnaire based on the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) and involved a range of trial stakeholders.

Results

Two co-design workshops, with a total of nine participants (n = 7 MHCP, n = 2 maternity service users), discussed thirteen BCTs as potential solutions. Ten BCTs, broadly covering Consequences and Reframing, progressed to intervention development. Forty-five trial stakeholders (clinical midwives, research midwives/nurses, doctors, allied health professionals and trial team members) participated in the online TFA questionnaire. The intervention was perceived effective, coherent, and not burdensome to engage with. Core areas for future refinement included Anticipated opportunity and Self-efficacy.

Conclusion

We developed a behaviour change recruitment intervention which is based on the accounts of MHCP trial recruiters and developed in a co-design process. Overall, the intervention was deemed acceptable. Future evaluation of the intervention will establish its effectiveness in enabling MHCPs to invite all eligible people to participate in a maternity care trial, and determine whether this translates into an increase in maternity trial recruitment rates.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13063-022-06816-6.

Background

It is widely acknowledged that clinical trials frequently fail to reach recruitment targets, with just 50% of publicly funded trials in the UK achieving optimal participant numbers [1]. The consequences for trials are far reaching, including underpowered results [2], increased costs, ethical implications [3], and ultimately contribution to ‘research waste’ [4]. However, within certain clinical areas, trial recruitment can face even greater challenges, for example, in clinical trials set within maternity care [5]. The participation of pregnant people in trials differs from the general population as it potentially affects two participants. The risk of teratogenicity and adverse pregnancy outcomes increases the perception of vulnerability surrounding the mother and baby dyad [6]. Our previous work, a qualitative evidence synthesis on recruiters’ perspectives of recruiting people to pregnancy and childbirth to clinical trials, found that Maternity Healthcare Professional (MHCP) recruiters often act as protective advocates, creating an additional gatekeeping barrier between trial and participant [7]. Factors such as these have likely contributed to limiting the number of eligible people participating in maternity trials [8, 9] and the evidence available to guide researchers recruiting to clinical trials in maternity care—synergistically creating a crisis for effective recruitment for trials in maternity care.

Empirical evidence on how to recruit participants to clinical trials in general is limited, with even less evidence on which strategies are effective. In the most recent Cochrane review of strategies to improve recruitment to trials [3], the majority of strategies were targeted towards potential participants rather than Healthcare Professional (HCP) recruiters. Only three of the recruitment interventions reported were aimed at HCPs, these centred around communication [10], training and ongoing support for clinicians [11], and evaluating email or postal invitations to general practitioners [12]. In addition to a lack of HCP focus, most of the interventions in the review are atheoretical and lack a predefined mechanism of action reported during the development. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) recently updated framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions (which a recruitment intervention would likely be considered) recognises the need for theory to inform intervention development [13]. As Brehaut et al., note, even large-scale methodological initiatives such as the Studies Within A Trial (SWAT) repository [14] contains studies of interventions focusing on a single aspect of recruitment that lacks a theoretical basis [15].

The trial recruitment process has multiple components [16], and many of the process components within recruitment can be considered behaviours. Behaviours such as talking about a trial with potential participants, distributing trial information, and collecting trial consent, are all behaviours that HCPs may not perform during the normal course of their role [17]. Framing trial recruitment in behavioural terms provides a structure for researchers to systematically identify which behaviours are amenable to change and target them with an intervention [18]. Using a behavioural approach to understand trial recruitment barriers has already shown promise across a variety of clinical settings [19, 20] and in trial process interventions specifically [15, 21]. While the use of behavioural theory in developing trial recruitment interventions is a relatively recent advancement [17], the theoretical grounding of this approach can offer a substantiated explanation of the barriers and solutions for trial recruitment in the maternity setting.

The aim of this study is to use behavioural theory in a co-design process to develop an intervention aimed at changing the behaviour of MHCPs recruiting to clinical trials in maternity care and to assess the acceptability and feasibility of such an intervention.

Methods

This study is part of a larger programme of research; the ENCOUNTER project, a multi-phased, mixed methods project exploring behavioural barriers to recruitment to clinical trials in maternity care from the recruiters’ perspective and developing an intervention to target the barriers. Our previous theory-guided qualitative interview study [22] with twenty-two MHCP recruiters identified the factors enabling or inhibiting MHCP recruiters to invite all eligible women to participate in a maternity care trial. Four global themes, Availability and accessibility of resources, Navigating the recruitment pathway, Prioritising clinical responsibilities over research responsibilities, and The influence of colleagues and peers, mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), identified thirteen salient TDF domains relevant to the behaviour. The target behaviour of interest ‘Maternity Healthcare Professionals inviting all eligible people to participate in a maternity care trial’ was specified in our previous study [22] using the AACTT framework [23].

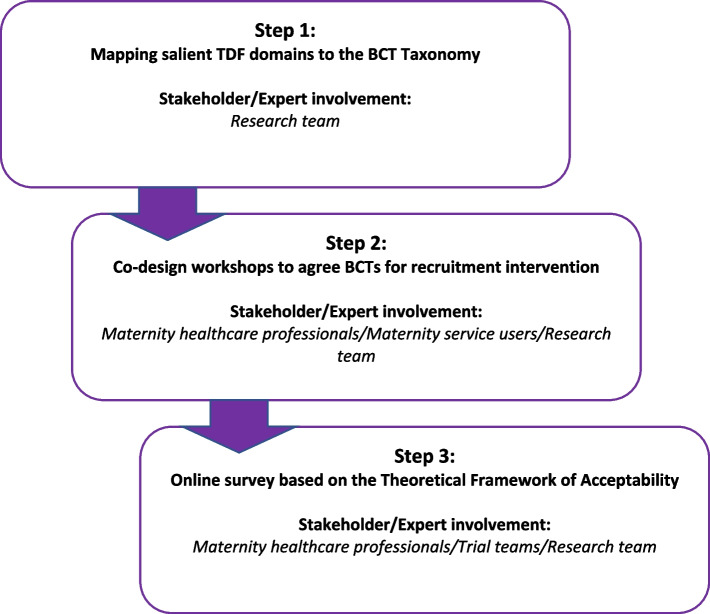

We conducted this study in three distinct steps (Fig. 1). Step 1 was to carry out a mapping exercise of the salient domains of the TDF to Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT) Taxonomy [24]. Step 2 was to hold a co-design workshop with stakeholders to discuss which BCTs to include in a recruitment intervention. Step 3 was to conduct an online survey to determine whether the resulting intervention was acceptable and feasible to a larger stakeholder group.

Fig. 1.

Overview of steps in intervention development

Step 1—Mapping salient TDF domains to behaviour change techniques (BCTs)

The first step in the development of the intervention was to identify BCTs that could potentially target the salient TDF domains identified and reported in our interview study [22]. BCTs are theoretically derived and the smallest ‘active’ components of an intervention [24]. Using the online Theory and Techniques tool (an interactive ‘heat map’ matrix of 74 BCTs and 26 mechanisms of action) [25], we mapped TDF domains to BCTs, noting which BCTs were most likely to be effective in changing behaviour within a particular domain. The mapping process, undertaken by VH and LL, produced a long list of BCTs for potential use in an intervention to enable MHCPs to invite all eligible people to participate in a maternity care trial. The long list was narrowed down by the research team (VH, KG, LB) based on whether the BCT was pragmatic to operationalise within the scope of the current study (for example, non-modifiable organisational factors such as requiring additional staffing or consultation rooms were excluded). Next, suggestions were made (VH) as to how each of the BCTs shortlisted could be operationalised as a potential solution either as a stand-alone, or as part of an intervention package. For example, BCT 7.1 ‘Prompts/cues’ could be operationalised by providing MHCPs with lanyard cards listing trial inclusion criteria. Potential solution suggestions were discussed (VH, LB, KG) and checked by behaviour change experts on the team (ED, LL) to ensure fidelity with the BCT linked to the behaviour. The APEASE (Acceptability, Practicability, Effectiveness/cost-effectiveness, Affordability, Safety/side-effects and Equity) criteria were applied by members of the team (VH, LB, KG) to the remaining BCTs which informed the final selection that were taken forward to the co-design workshop [26].

Step 2—Co-design workshops for developing behaviour change recruitment intervention

In this step of the development, we included MHCP recruiters and maternity service users as stakeholders. This was to ensure the resulting intervention(s) were fit for purpose from the perspective of those who may use/receive it. We chose to hold two separate online co-design workshops, with two separate sets of participants, allowing the opportunity for each participant to contribute to the discussion.

Sampling

Previous participants from our interview study [22], who had consented to future contact, were invited (without obligation) to take part. We also invited maternity service users, who had experienced pregnancy within the past 2 years, via the ENCOUNTER Study Twitter account. Interested people were asked to email the research team and were sent a ‘Study Pack’ (including a brief summary of the ENCOUNTER project, workshop agenda, outline of potential solutions for discussion, and consent form). Participants returned a digital copy of signed consent. We allocated participants to one of two workshops based on their preference, clinical/professional role (midwife, nurse, doctor), the trial they were/had recruited for, and geographical location. This was to ensure, in so far as possible, that groups were balanced. Pilot workshops were held with MHCP recruiters and members of the trials community to check the coherence of the workshop content and format. Pilot participants had no previous involvement with the ENCOUNTER project, did not take part in the actual co-design workshops, nor was the data collected included in the analysis.

Workshops were held via Zoom in October 2021 and scheduled to last 90 min. Facilitation of both workshops was led by VH and co-facilitated by ED and LL. A brief summary of the ENCOUNTER project, an explanation of the ‘behavioural approach’ and workshop objectives was presented to participants using MS PowerPoint. In workshop 1, participants were asked to consider seven BCTs: Pros and cons, Goal setting (behaviour), Goal setting (outcome), Information about antecedents, Self-monitoring of behaviour, Review behaviour goals, and Review outcome goals. Each of these was presented with a description of how it could be operationalised as a potential solution to the target behaviour. Workshop 2 followed the same format, participants were asked to consider five BCTs: Information about health consequences, Information about social and environmental consequences, Reduce negative emotions, Information about emotional consequences, and Salience of consequences. The BCT 13.2 Reframing was implicit in both workshops as the premise of the intervention was to conceptualise ‘recruiting’ as ‘inviting’ all eligible people to participate in a maternity trial. During both workshops, participants gave their opinion on each potential solution presented and discussed how or if they could envision the potential solution being used in practice. Finally, participants were asked if any potential solution stood out as particularly helpful or unhelpful in inviting all eligible people to participate in a maternity care trial. In using co-design principles [27], we anticipated that participants would naturally begin to discuss BCTs beyond those presented. We decided a priori to make a list of any additional BCTs suggested by participants and crosscheck them against the original long-list generated by the mapping exercise. This allowed us to reintroduce any BCTs stakeholders deemed important that had been excluded earlier.

Discussions were audio recorded to facilitate transcription and also summarised in real-time to feed back to participants at the end of the workshop (LL). Directed content analysis was performed (VH) [28], focussing on participant-reported concerns and/or advantages related to each potential solution. The summarised findings were checked by all members of the research team by comparing findings to notes taken during the workshops by LL and ED. BCTs from both workshops were brought together and VH, KG, and LB met to ensure all BCTs remained within the APEASE criteria [26]. We used the GUIDED [29] and TIDieR [30] checklists to report the development and content of the intervention (Supp. File 1).

Step 3—Evaluating acceptability and feasibility of the proposed intervention

In the third step, we conducted an online survey to assess the acceptability and feasibility of the proposed recruitment intervention. A 3-min video introducing the proposed intervention and demonstrating a prototype of the ENCOUNTER app was recorded by the team and embedded within the online survey hosted by QuestionPro. The survey design was informed by the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA), a theoretical framework developed to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions [31]. Participants were asked to respond using a five-point Likert scale to two belief statements and seven questions focused on each of the seven TFA constructs: Affective attitude, Burden, Ethicality, Intervention coherence, Opportunity, Perceived effectiveness, and Self-efficacy. An open text box was also provided for additional comments.

Sampling

We identified the two stakeholder groups that could potentially interact directly with the intervention: MHCPs and maternity trial team members. We invited members of these groups (based in Ireland or the UK) to complete the questionnaire. MHCPs who had taken part in or previously indicated interest in any phase of the study were emailed an invitation to participate. Chief investigators of relevant maternity care trials (identified through a clinical trials database search of Ireland and the UK) were also invited to take part. In addition, the link to the survey was promoted and shared on social media via the ENCOUNTER Study Twitter account. Consent was implicit by completion and submission of the questionnaire.

Results

Step 1—Mapping salient TDF domains to Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs)

Initially, the mapping exercise resulted in 31 BCTs being identified as relevant to the target behaviour. From this long-list, 18 BCTs were excluded based on APEASE criteria. Table 1 presents further detail on the mapping process and justification for inclusion/exclusion. The remaining short-list of BCTs (n = 13) were then divided into two groups, broadly based on intervention function (i.e. how an intervention can change behaviour, e.g. education or modelling), to facilitate presentation to stakeholders at the co-design workshops.

Table 1.

Results of mapping exercise (short-list of Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT) for potential inclusion in recruitment intervention)

| Behavioural analysis using TDF: barriers and enablers to inviting all eligible women to participate in a clinical trial in maternity care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | TDF domain | BCT (salient domain) | Example/suggestions | Intervention function(s) | Decision/notes |

|

Availability and accessibility of resources Having access to resources is a key enabler for trial recruitment. Recruiters need reliable technology such as iPads to facilitate mobile recruitment as they often have ‘no fixed abode’. Recruiters also struggle to communicate effectively without the use of dedicated reliable mobile phone technology. There is rarely a dedicated space for recruiters to have a private conversation with potential participants. Recruiters frequently ‘lurk’ in corridors and waiting rooms to meet potential participants. While the majority of recruiters identified the lack of space as a barrier, some felt that recruiting participants from the waiting area was an efficient use of the woman’s time. Having a sufficient number of staff, both clinical and research, allows recruiters the capacity to approach all eligible women and take the time needed to present and discuss the trial thoroughly with them. Recruiters frequently report that being understaffed limits their ability to reach all eligible women and as a result many recruitment opportunities are missed. Trial funding also plays a role in influencing recruitment efforts, as some recruiters report placing a greater emphasis on offering the trial to all eligible women, when the trial secures funding for the department |

ECR |

3.2. Social support (practical) Advise on, arrange, or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) for performance of the behaviour |

Set up an online peer support group for recruiters Develop a trial recruiter network with regular meetings providing peer support |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

7.1. Prompts/cues Introduce or define environmental or social stimulus with the purpose of prompting or cueing the behaviour. The prompt or cue would normally occur at the time or place of performance |

Provide recruiters with lanyard cards listing trials and inclusion criteria | Environmental restructuring | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

12.1. Restructuring the physical environment Change, or advise to change the physical environment in order to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour (other than prompts/cues, rewards and punishments) |

Have designated space (or folder) where trial materials are convenient and easy to access | Environmental restructuring | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

12.2. Restructuring the social environment Change, or advise to change the social environment in order to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour (other than prompts/cues, rewards and punishments) |

Assign roles (“champions”) responsible for trial recruitment in the area. Champions would take the lead to ensuring all women were approached with trial information | Environmental restructuring | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

12.5 Adding objects to the environment Add objects to the environment in order to facilitate performance of the behaviour |

Display trial information posters in the clinical area and staff break room (content maybe additional multiple BCTs on poster) | Environmental restructuring |

Exclude— APEASE (effectiveness) not reaching target (AACTTa) |

||

|

Planning and preparation The importance of planning and preparing for trial recruitment was emphasised. This involves screening ward and clinic lists and accessing women’s charts to gain background knowledge on potential participants. Recruiter’s favour strategies such as using a ‘two stage’ recruitment process because it allows women more time to assimilate trial information and make an informed decision as to whether they take part or not. Recruiters differentiate between non-CTIMP and CTIMP, highlighting that the latter requires extra planning and preparation on their behalf |

Behavioural regulation Less salient domains: Knowledge Memory, attention, decision-making processes |

1.2. Problem solving Analyse, or prompt the person to analyse, factors influencing the behaviour and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators (includes ‘Relapse Prevention’ and ‘Coping Planning’) |

Provide recruiters with an opportunity to role play the recruitment encounter during trial training. Recruiters could role play with clinical colleagues to anticipate any environmental or emotional barriers and generate strategies to overcome these | Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

2.3. Self-monitoring of behaviour Establish a method for the person to monitor and record their behaviour(s) as part of a behaviour change strategy |

Ask recruiters to keep a record of each recruitment encounter or potential encounter and the outcome—recruiters could then reflect on diary and share learning with peers | Enablement | Include | ||

|

11.2. Reduce negative emotions Advise on ways of reducing negative emotions to facilitate performance of the behaviour (includes ‘Stress Management’) |

To overcome ‘feeling the vibe’ remind recruiters that it’s OK just to invite women to the trial by giving them the information | Enablement | Include | ||

|

11.3. Conserving mental resources Advise on ways of minimising demands on mental resources to facilitate behaviour change |

Recruiters to carry with them trial information packs/lanyards cards with eligibility criteria | Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

Being visible The visibility of the trial and also the recruiter is important. Recruiter’s discussed ways in which they promote the trial, using methods such as posters to raise awareness of the trial amongst clinical staff and potential participants, both internally and externally at the site. Recruiters use creative means to maintain visibility of the trial and in doing so extend their reach in accessing potential participants that might otherwise have been missed. Recruiters being visible and having a presence in the clinical area also raises awareness about the trial and gives clinical colleagues a point of contact where they can signpost potential participants to |

Behavioural regulation Domain was only identified as an enabler (not a barrier) Less salient domains: Intentions Environmental Context and resources |

1.2. Problem solving Analyse, or prompt the person to analyse, factors influencing the behaviour and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators (includes ‘Relapse Prevention’ and ‘Coping Planning’) |

Encourage recruiters to plan Give recruiters time to plan and develop design recruitment strategies tailored to each trial and each site |

Enablement | Exclude—domain was only identified as an enabler (not a barrier) |

|

2.3. Self-monitoring of behaviour Establish a method for the person to monitor and record their behaviour(s) as part of a behaviour change strategy |

Ask recruiters to record where they placed posters etc. to monitor what works. Ask women and clinical if they have noticed these posters referring to the trial | Enablement | |||

|

8.2. Behaviour substitution Prompt substitution of the unwanted behaviour with a wanted or neutral behaviour |

Recruiters approach all eligible women about trial the rather than making an assessment beforehand Promote visibility of the trial and the recruiter by regular visits to the clinical area Recruiters hand out ‘business’ card with photo and contact details to colleagues and women |

Restriction | |||

|

11.2. Reduce negative emotions Advise on ways of reducing negative emotions to facilitate performance of the behaviour (includes ‘Stress Management’) |

Reduce feelings of ‘being in the way’ by trial teams/clinical seniors reiterating the value of what they are doing and their contribution to clinical advancement | Enablement | |||

|

11.3. Conserving mental resources Advise on ways of minimising demands on mental resources to facilitate behaviour change |

Recruiters wear ID badges with trial name and recruiter role clearly visible Recruiters wear lanyards with trial name and their role clearly visible Advertise trials and brief inclusion criteria using hospital website/app |

Enablement | |||

|

Approach to recruiting Recruiters describe how the actual approach to recruitment needs to be sensitive and appropriate to the woman’s situation. There was a common feeling that the approach should be quiet and gentle. Recruiters talk about the importance of timing when recruiting, choosing the ‘right’ time to approach was seen as key in successfully recruiting into a trial. Recruiters also discuss how their intuition plays a part in whether or not they approach a woman, describing how having a ‘feeling’ or getting a ‘vibe’ may deter them from offering a trial to a women despite her meeting eligibility criteria. Recruiters highlight that communicating the trial in a concise understandable way is key, and many describe having rehearsed a recruitment ‘spiel’ for each trial |

Emotion Less salient domains: Skills Beliefs about Consequences Environmental context and resources |

11.2. Reduce negative emotions Advise on ways of reducing negative emotions to facilitate performance of the behaviour (includes ‘Stress Management’) |

Reduce feelings of apprehension (burdensome to women) by using a ‘two-stage’ recruitment strategy to introduce the trial To overcome ‘feeling the vibe’ remind recruiters that it’s OK just to invite women to the trial by giving them the information Reduce negative emotions through building peer network—discuss the balance between protecting women’s interests while supporting them to benefit from evidence-based care |

Enablement |

Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice Include Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

5.5. Anticipated regret Induce or raise awareness of expectations of future regret about performance of the unwanted behaviour |

Ask recruiters to assess the degree of regret they will feel if they do not invite all eligible women to participate in a trial (ask them how they would feel if potential participants are overlooked) | Coercion | Exclude—APEASE (not appropriate) | ||

|

5.6. Information about emotional consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about emotional consequences of performing the behaviour |

Provide recruiters with information about women’s autonomy and right to determine their own health choices. Remind recruiters that whether to offer trial participation is not their choice to make | Education/Persuasion | Include | ||

|

12.6. Body changes Alter body structure, functioning or support directly to facilitate behaviour change |

Make recruiters aware of how they position themselves during a recruitment encounter. Encourage recruiters to be at the same eye level as the woman (i.e. both seated) when discussing the trial | Enablement |

Exclude— APEASE (not practicable) |

||

|

13.2. Framing/reframing Suggest the deliberate adoption of a perspective or new perspective on behaviour (e.g. its purpose) in order to change cognitions or emotions about performing the behaviour (includes ‘Cognitive structuring’) |

Recruiters focus on offering the ‘invitation’ to participate in a trial (rather than thinking about the number of women that agree to participate) | Enablement | Include | ||

|

The ‘right’ participants Despite believing that all pregnant women, if eligible, should be offered the opportunity to join a trial, and have the right to decide whether or not they participate, recruiters highlighted difficulties in identifying the ‘right’ participants. In the first instance, recruiters discuss assessing the suitability of potential trial participants based on their own judgement or beliefs on whether the woman could or would complete the trial. In the second instance, recruiters report the ambiguity relating to their own interpretation of the protocol criteria i.e. who was or was not eligible, proved problematic in finding the ‘right’ participant for the trial |

Beliefs about consequences Less salient domains: Knowledge Memory and decision processes Intentions |

5.1. Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour |

Explain that not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial could restrict and slow down evidence generation and treatment options for o women during pregnancy | Education | Include |

|

5.2. Salience of consequences Use methods specifically designed to emphasise the consequences of performing the behaviour with the aim of making them more memorable (goes beyond informing about consequences) |

Show treatment options and advances in care now available to women as a result of earlier clinical trial. Show how lack of evidence limits choices and treatment options for women | Education | Include | ||

|

5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about social and environmental consequences of performing the behaviour |

Remind recruiters that women have the right to be asked if they would like to participate | Persuasion | Include | ||

|

5.5. Anticipated regret Induce or raise awareness of expectations of future regret about performance of the unwanted behaviour |

Ask recruiters to assess the degree of regret they will feel if they do not invite all eligible women to participate in a trial (ask them how they would feel if potential participants are overlooked) | Coercion | Exclude—APEASE (not appropriate) | ||

|

5.6. Information about emotional consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about emotional consequences of performing the behaviour |

Provide recruiters with information about women’s autonomy and right to determine their own health choices. Remind recruiters that whether to offer trial participation is not their choice to make | Education/Persuasion | Include | ||

|

9.2. Pros and cons Advise the person to identify and compare reasons for wanting (pros) and not wanting to (cons) change the behaviour (includes ‘Decisional balance’) |

Ask recruiters to list and compare the advantages and disadvantages of inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial | Enablement | Include | ||

|

10.10. Reward (outcome) Arrange for the delivery of a reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in achieving the behavioural outcome (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’) |

Arrange for recruiters to receive reward (i.e. box of chocs) if, and only if, there is an increase in the number of women are invited to take part in a trial | Incentivisation | Exclude—APEASE (ethical) | ||

|

4.1. Instruction on how to perform behaviour Advise or agree on how to perform the behaviour (includes ‘Skills training’) |

Provide step by step training to recruiters on how to invite all eligible women to participate in a trial | Training | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

4.2. Information about antecedents Provide information about antecedents (e.g. social and environmental situations and events, emotions, cognitions) that reliably predict performance of the behaviour |

Encourage recruiters to keep a record of situations or events occurring prior to approaching a woman about the trial and reflect on this (learning) with peers Experienced recruiters to give lectures/talk discussing how to troubleshoot antecedents |

Education | Include | ||

|

5.1. Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour |

Explain that not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial could restrict and slow down evidence generation and treatment options for o women during pregnancy. Specific tagline (easy for recruiters remember) about the health consequences of not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial | Education | Include | ||

|

5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about social and environmental consequences of performing the behaviour |

Remind recruiters that not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial could led to health inequality for women Highlight the contribution to evidence that inviting all eligible women to trial makes |

Education/Persuasion | Include | ||

|

Putting women’s clinical care and wellbeing first Prioritising the clinical care and wellbeing of potential participants is a view shared by all recruiters in the study. Trial recruitment is a secondary consideration for recruiters as they attend to the immediate physical or emotional needs that women have. Recruiters discussed their professional responsibility and a duty of care towards women and seek to minimise any potential burden associated with participation |

Intentions Less salient domains: Social/professional Role and identity Goals |

Goal setting (behaviour) Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of the behaviour to be achieved |

Ask recruiters to set an agreed daily/weekly goal for inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial | Enablement | Include |

|

5.1. Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour |

Explain that by not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial reduces the evidence base and treatment options available to women during pregnancy.Reinforce research as part of clinical care and central to generating evidence to inform treatments. Emphasise the counter factual is to provide a treatment based on preference not evidence, i.e. care will not be evidence based, rather it will be based on the clinicians preference | Education | Include | ||

|

10.8. Incentive (outcome) Inform that a reward will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in achieving the behavioural outcome (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’) |

Inform recruiters that they will receive money if, and only if, there is an increase in the number of women are invited to take part in a trial Acknowledge changes in behaviour (i.e. increased number of women invited to trial) by rewarding recruiters with co-authorship or other non-monetary incentives |

Incentivisation |

Exclude— APEASE (not acceptable) |

||

|

Acceptability of the intervention Recruiter’s beliefs about the acceptability of the intervention directly influences whether or not they invite all eligible women to a trial. Recruiters were more comfortable and therefore more willing to recruit to trials where they believed the intervention was acceptable to women. Recruiting for trial interventions that did not align with their professional opinion was more challenging for recruiters. Furthermore, the recruiter’s perception of acceptability varies depending on their clinical background |

Beliefs about consequences Less salient domains: Social and professional role and identity |

5.1. Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour |

Inform recruiters of the rationale for the trial intervention and how the trial results will help fill a gap in the evidence Explain that approaching all eligible women has a potential to make trials happening more efficiently and generate evidence more quickly Address concerns about the acceptability of the trial intervention with the early involvement of recruiters (from MDT background) in design |

Education |

Include Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

5.2. Salience of consequences Use methods specifically designed to emphasise the consequences of performing the behaviour with the aim of making them more memorable (goes beyond informing about consequences) |

Show recruiters treatment options and advances in care now available to women because of earlier clinical trials interventions Invite past trial participants to discuss with recruiters their experiences of receiving an intervention that had been deemed ‘less acceptable’ |

Persuasion |

Include (would need to also give balance of different opinions) |

||

|

5.3. Information about social and environmental consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about social and environmental consequences of performing the behaviour |

Remind recruiters that not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial could led to health inequality for women Highlight the contribution to evidence that inviting all eligible women to trial makes |

Persuasion | Include | ||

|

5.5. Anticipated regret Induce or raise awareness of expectations of future regret about performance of the unwanted behaviour |

Ask recruiters to assess the degree of regret they will feel if they do not invite all eligible women to participate in a trial with an intervention that later proves beneficial to women’s care, or standard care proved to be detrimental | Coercion | Exclude—APEASE (not appropriate) | ||

|

5.6. Information about emotional consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about emotional consequences of performing the behaviour |

Recruiters share anecdotes of past emotionally sensitive situations where women were glad to be invited to participate in the trial and may have found inclusion helpful or comforting in their situation | Education/Persuasion | Include | ||

|

Commitment to the research Recruiters express a sense of ownership towards the trial and discuss feeling ‘invested’ in it. This sense of ownership and desire for success appears to encourage recruiters to extend the invitation to participate in the trial to all eligible women Recruiters consider the research to be a worthwhile endeavour when it addresses a clinical need. Recruiters are also keen to show clinical colleagues that the research is worthwhile. Belief in the research enables recruitment, however, when doubts are raised so too are barriers |

Intentions Less salient domains: Social and professional role and identity Beliefs about consequences |

1.1. Goal setting (behaviour) Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of the behaviour to be achieved |

Ask recruiters to set an agreed daily/weekly goal for inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial | Enablement | Include |

|

5.1. Information about health consequences Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour |

Explain that not inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial reduces the potential evidence base and treatment options available to women during pregnancy | Education | Include | ||

|

10.8. Incentive (outcome) Inform that a reward will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in achieving the behavioural outcome (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’) |

Inform recruiters that they will receive a reward for increasing the number of eligible women invited to the trial (possible reward with co-authorship/public acknowledgement) | Incentivisation | Exclude—APEASE (ethical) | ||

|

Being supported Support from peers across the trial setting is important to recruiters and enables them to offer the trial to all eligible women. Collaboration from clinical colleagues allows recruiters to gain access to potential participants, this support is valued by recruiters as they make efforts to build and nurture these relationships. Recruiters report that the absence of support from clinical colleagues passively blocks them from reaching all potential trial participants. Collaboration with other trial recruiters, both inside and outside the current trial, provides an additional source of support encouraging recruiters to offer the trial to all eligible women Recruiters reported that regular communication with the trial team was helpful, while onsite support from the team was especially appreciated |

Social Influences Less salient domains: Social and professional role and identity Reinforcement |

3.1. Social support (unspecified) Advise on, arrange or provide social support (e.g. from friend, relatives, colleagues or staff or non-contingent praise or reward for performance of the behaviour. It includes encouragement and counselling, but only when it is directed at the behaviour |

Encourage recruiters to call a ‘buddy’ when they are struggling to invite all eligible women to the trial (i.e. set up WhatsApp group) Give recruiters protected time to engage in their peer support network |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

3.2. Social support (practical) Advise on, arrange, or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) for performance of the behaviour |

Set up an online peer support group for recruiters Develop a trial recruiter network with regular meetings providing peer support Opportunities for peer learning both within and across sites, etc Team meetings to discuss the trials (similar to MDT meeting) to get buy in from cross speciality |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

6.2. Social comparison Draw attention to others’ performance to allow comparison with the person’s own performance |

Show recruiters the proportion of women approached to participate in a trial by other trial recruiters/sites and compare with their own data Site league tables (publish data on all trial sites including their level of resources) at set time points in the recruitment process, so that each site can see for themselves how they compare |

Persuasion | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

6.3. Information about others’ approval Provide information about what other people think about the behaviour. The information clarifies whether others will like, approve or disapprove of what the person is doing or will do |

Let recruiters know clinical colleagues are on board and approve of the trial invitation | Persuasion | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

10.4. Social reward Arrange verbal or non-verbal reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’) |

Congratulate and praise recruiters for each day/week they invite all eligible women to participate in a trial (not just for numbers recruited). Potential mode of delivery—Twitter/email/card to acknowledge effort | Incentivisation | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

Gatekeeping Recruiter’s report experiencing some logistical and/or active clinician gatekeeping at trial sites. Much to the frustration of some recruiters, there appears to be a number of eligible women that are denied the invitation to participate in a trial because of logistical or clinician gatekeeping. While some recruiters are sympathetic and make an allowance for gatekeeping behaviour, others seek to address it by escalating the issue to senior colleagues |

Social Influences Less salient domains: Intentions |

3.1. Social support (unspecified) Advise on, arrange or provide social support (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, buddies or staff or non-contingent praise or reward for performance of the behaviour. It includes encouragement and counselling, but only when it is directed at the behaviour |

Advise recruiters to call a ‘buddy’ when they are struggling (due to gatekeeping) to invite all eligible women to the trial Arrange for trial team to support recruiters with regular site visits |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice |

|

3.2. Social support (practical) Advise on, arrange, or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff for performance of the behaviour |

Set up an online peer support group for recruiters Develop a trial recruiter network with regular meetings providing peer support Encourage research culture with recruiters giving clinical colleagues regular updates on the progress of the trial and potential contribution it will make to the clinical field |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

6.2. Social comparison Draw attention to others’ performance to allow comparison with the person’s own performance |

Recruiters show clinical colleagues the proportion of women approached at their site compared to other sites (produce a visual representation like a thermometer chart, showing climbing numbers | Persuasion |

Exclude APEASE (effectiveness) only helpful if number of women approached does in fact lead to more recruitment |

||

|

6.3. Information about others’ approval Provide information about what other people think about the behaviour. The information clarifies whether others will like, approve or disapprove of what the person is doing or will do |

Tell recruiters that clinical colleagues approve of all eligible women being invited to participate in a trial Hold MDT trial meetings to discuss trials in the clinical area |

Persuasion | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

10.4. Social reward Arrange verbal or non-verbal reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’) |

Congratulate each clinical area for referring women to the trial (numbers could be identified by doing an audit asking women if they had been invited to participate in a trial during their care episode—results could be displayed in public area of hospital | Incentivisation | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

Recruitment targets Recruitment targets set by the trial teams can be a driver for recruiters and encourages them to invite all eligible women to join a trial. Targets can also create competition between trial sites, which is generally well received as recruiters appreciate the opportunity to benchmark their recruitment performance. However, the element of competition serves as a disincentive for some recruiters as they feel under pressure to measure up to what they often consider as unachievable recruitment targets |

Goals Less salient domains: Reinforcement Emotion Social influences |

1.1. Goal setting (behaviour) Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of the behaviour to be achieved |

Collaborative goal setting (considering resources) encouraging recruiters to set an agreed daily/weekly goal of inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial. Emphasis on SMART goals Discuss with site teams to set realistic targets |

Enablement |

Include (emphasis on this has to be a collaborative effort, given that unrealistic goals etc. can serve as a disincentive) |

|

1.3. Goal setting (outcome) Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of a positive outcome of wanted behaviour |

Set a weekly goal (e.g. x number of eligible women invited to trial) as an outcome of changed recruitment behaviours | Enablement | Include | ||

|

1.5. Review behaviour goal(s) Review behaviour goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) or behaviour change strategy in light of achievement. This may lead to re-setting the same goal, a small change in that goal or setting a new goal instead of (or in addition to) the first, or no change |

Collaboratively review how well a recruiter’s/site’s performance corresponds to the previously agreed goals (e.g. whether they invited all eligible women to trial). Modifying future goals to ensure that they remain realistic given environmental constraints and adjust as required Review and feedback on screening logs Regular review of targets (and active support of trial teams to achieve them) |

Enablement | Exclude—APEASE (effectiveness) existing practice | ||

|

1.6. Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal Draw attention to discrepancies between a person’s current behaviour (in terms of the form, frequency, duration, or intensity of that behaviour) and the person’s previously set outcome goals, behavioural goals or action plans (goes beyond self-monitoring of behaviour) |

Trial team to do an audit and feedback on previously agreed site goals and highlight any discrepancies. The findings could be reported to recruiters and followed up with offers of practical assistance from the trial team | Coercion |

Exclude— APEASE (acceptability) |

||

|

1.7. Review outcome goal(s) Review outcome goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) in light of achievement. This may lead to re-setting the same goal, a small change in that goal or setting a new goal instead of, or in addition to the first |

Review how many eligible women were invited to participate in a trial and consider modifying the recruitment goal accordingly, e.g. by increasing or decreasing subsequent recruitment targets | Enablement | Include | ||

aAACTT Action Actor Context Target Time

Step 2—Co-design workshop for developing behaviour change recruitment intervention

Twenty-two MHCP recruiters were invited to participate in one of the co-design workshop; 10 agreed to take part; due to unforeseen clinical commitments, three later withdrew. MHCPs had a range of maternity trial experience in Ireland and the UK and clinical backgrounds that included midwifery, nursing, and obstetrics. Six maternity service users expressed an interest in participating; of those, two women who had birthed within the past 6 months consented to take part. Both women had previous experience of participation in clinical research but not in a clinical trial. Further details on participant characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recruitment intervention co-design workshops: participant characteristics

| Total number of participants in workshop | n = 9 |

|---|---|

| Workshop 1 | 5 |

| Workshop 2 | 4 |

| Participants (maternity service users) | n = 2 |

| Based in Ireland | 2 (100%) |

| Based in UK | 0 |

| Participants (HCP recruiters) | n = 7 |

| Based in Ireland | 1 (14%) |

| Based in UK | 6 (86%) |

| Professional background | |

| Clinical midwife/nurse | 0 |

| Research midwife/nurse | 6 (86%) |

| Obstetrician | 1 (14%) |

| Recruitment experience (HCP) | |

| 2 years | 7 (100%) |

| < 2 years | 0 |

| Clinical experience | |

| < 5 years | 1 (14%) |

| > 5 years | 6 (86%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (87.5%) |

| Male | 1 (12.5%) |

Workshop 1 (duration: 99 min) included five participants. Workshop 2 (duration: 106 min) included four participants. Participants offered comment on each potential solution, and the group discussed and made suggestions about how they might be adjusted, improved, or delivered in practice. Participants in both workshops suggested the intervention could be delivered as part of mandatory training. However, the majority of participants were strongly opposed to this idea, stating that the agenda for mandatory training days was already full and adding something further would necessitate losing something equally important. Participants were concerned that in the current climate (COVID-19 pandemic) MHCPs did not have the appetite for more training and it would become “just another ‘thing’ they had to do”.

Many participants commented on how mobile phone apps had recently become a useful tool in recruitment. Voice notes were discussed as a particularly helpful method of communication between MHCP recruiters. Group members shared scenarios where they regularly used voice notes to instruct other recruiter colleagues about how to communicate trial specific information to potential participants. One participant had found voice notes especially useful as a means of facilitating remote recruitment, by communicating directly with women about the trial during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following a discussion summary, participants were asked if they considered any potential solution to be particularly helpful or unhelpful in inviting all eligible people to participate in a maternity trial. In workshop 1, the majority agreed that having ‘experienced recruiters give a talk (or video clip) about resolving situations that commonly occur prior to inviting a woman to a trial’ (BCT 4.2—Information about antecedents) was the most helpful. There was no agreement on the least helpful potential solution as participants all selected different BCTs. In workshop 2, participants agreed that all the potential solutions presented to them would be helpful in addressing the barriers. Furthermore, participants creatively suggested that some solutions could be combined to make a more practicable intervention. Tables 3 and 4 provides a brief summary of participant discussion around each potential solution presented at the workshops.

Table 3.

Summary of trial recruitment intervention co-design workshop discussion with maternity healthcare professionals and maternity service users: workshop 1

|

Recruiter’s list and compare advantages and disadvantages of inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial 9.2 Pros and cons (linked subthemes—the ‘right’ participants and acceptability of the intervention) |

• Good to do at start of study, discuss how to approach and reassess once study is underway • Depends on resources and capacity to screen women to do this • Inviting all women promotes research—helpful for future studies • This is not something consciously done at the moment • Important to include underrepresented, non-English speaking, ethnic, and cultural minorities • Wouldn’t use this method—prefer team-based approach to make trial more appealing, educate public about what a trial involves • Tool is more helpful for trials difficult to recruit to or struggling—could modify approach by recognising problem |

|

Set an agreed daily/weekly goal to invite all eligible women 1.1 Goal setting (behaviour) (linked subthemes—putting women’s clinical care and wellbeing first and commitment to the research and recruitment targets) |

• Setting targets helps—nice to be first to recruit and gain sense of achievement • Depends on trial, some trials you really can’t set goals for (lack of staff, not enough patients, etc.) • Tool could be helpful in identifying where problems are—should be reward rather than punishment system • Goals depend on staff availability and staff to support women throughout the trial ‘• Goals’ focuses on quantity not quality—talking to everyone spreads yourself too ‘thin on the ground’ • ‘Goals’ not good, means just another pressure—wouldn’t benefit the trial • Better to concentrate on areas to target (ward, clinics etc.) for recruitment rather than numbers |

|

Set an agreed weekly goal to have increased the number of women invited to the trial 1.3 Goal setting (outcome) (linked subthemes—recruitment targets) |

• This one is about incentivising people to approach more women than they are doing currently • If you are recruiting well, you do not need this • Inviting everyone could be a tick box exercise (invitees may not sign up for study) • Most multicentre sites do not know how many women have been invited—screening logs are not routinely looked at • Tool might be useful on a local level to know if you are targeting the right areas • Tool is useful if talking to lots of women means lots of recruits • It is the quality of the chat not the numbers invited—its deeper than just numbers • Goals motivate people; it gets people working together on something • It would be more beneficial to look back retrospectively to learn rather than set goals |

|

Experienced recruiters give talk (or video clip) about resolving situations that commonly occur prior to inviting a woman to a trial 4.2 Information about antecedents (linked subthemes—planning and preparation and being visible and benefit of experience) |

• Include people from different backgrounds, recruiters from ethnic minorities have different experiences and are asked different questions • This could cover a range of difficulties faced—talk through and present ways of resolving those • Also helpful in deflecting concerns and uncertainties in the clinical team—addressing these head on is sensible • May not video but a meeting or something at local level—because issues differ from site to site • Could be PI, R&D lead, research midwife/nurse delivering • Could be virtual conservation so people could ask questions, and provide recording to watch back • Zoom meetings for recruiters are held for some trials but are not always accessible as timing does not always suit staff • WhatsApp voice notes are helpful for recruiters to communicate their methods to other recruiters • Good idea to have one video at set up and one subsequently as may need to adapt approach as trial goes on |

|

Recruiters keep diary of recruitment or potential recruitment encounters (reflecting on diary and shared learning with peers) 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour (linked subthemes—being visible and planning and preparation) |

• Writing in diary is useful, means you will remember • Write significant encounters, difficulties, or learnings—do not want to record every single thing • Fill them out when you have time—can be brief as they need to be • Diary is reflective and more useful than a screening log • Could be recorded centrally or as a personal record—Sharing diary is not problematic (all agreed) • Positive consequence—the record shows difficulties or missed opportunities which could justify argument for more resources • Tool could be helpful to show R&D why recruitment is problematic • Not sure reflection is helpful—if you are recruiting well why are you reflecting on it? • Diary provides retrospective perspective, helpful in identifying where women could potentially be missed |

|

Regular review (with trial team) of the change in behaviour being used by recruiters 1.5 Review behaviour goals (linked subthemes—recruitment targets) |

• Might be helpful if you are not recruiting well—see where you could improve • Not regular review—better to positively motivate people with degree of healthy competition • Trial team already send league tables—giving shout out to top recruiter • On a local level you can incentivise with chocolates, etc.—small stuff means something • Already being done—it really helped concentrating on where is focus efforts • Review of behaviour change ensures you are doing your best and change if necessary |

|

Trials teams carry out monthly review to reveal if all eligible women had been invited to the trial 1.7 Review outcome goals (linked subthemes—recruitment targets) |

• This is not achievable as there is no record of ‘all women’—not possible to know about all eligible women • You already know if you have approached all eligible women, and if not, you know why • This is not useful because capacity of the team is often the problem • Review helps people write down the issues and address them • A positive consequence might be reallocation of staff following review |

Table 4.

Summary of trial recruitment intervention co-design workshop discussion with maternity healthcare professionals and maternity service users: workshop 2

|

Inform recruiters that research is part of clinical care, explain the importance of maternity care research and give the rationale for trial 5.1 Information about health consequences (linked subthemes—the ‘right’ participants and benefit of experience and acceptability of the intervention and commitment to the research) |

• Research should be considered part of clinical care • COVID, through news and social media, has helped push importance of clinical research to the fore front • Work is now being done to promote research as part clinical care—research feels more embedded in clinical practice than before COVID—this needs to continue as both branches of same tree • Challenging and burdensome for research staff to educate clinical colleagues that women deserve research opportunities • Helpful to show a direct link between research and clinical care |

|

Remind recruiters that all eligible women should be offered the chance to participate 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences (linked subthemes—‘the ‘right’ participants and benefit of experience and acceptability of the intervention) |

• Really good idea—research invitation should be embedded like flu vaccine or whooping cough vaccine • Need to be conscious of this—it is hard to talk about and hard to admit • Healthcare services should prioritise translated/plain English versions of all medical information is available to women—so that if communication is difficult, she has something to go home with and discuss with others • Educate the research team to understand exactly why the trial is important and why it is a better option to offer it to everyone • Particularly relevant for bereaved women—participating might give some meaning to their experience • Mandatory training could be good delivery mode - reenforces research as part of clinical care, everybody is offered the same health advice, they should be offered research participation (i.e. all staff receive it, does not feel personal, gives people time to ask questions, not trial specific, just promoting awareness) • Mandatory training is relentless • Messages needs to come from senior staff—clinical leaders rather than researchers • Could have big campaign using up to date social media, i.e. Instagram and TikTok |

|

Remind recruiters that it is OK to invite women by just giving them information 11.2 Reduce negative emotions (linked subthemes—planning and preparation and being visible and approach to recruiting) |

• Really helpful as there is a lot of pressure to recruit to targets—ongoing funding and posts demand on accruals • Pressure to recruit and limited time leads recruiters to approach only those they believe more likely to take part • Just giving information increases likelihood of recruitment • Ok if they decline—shows you have given them an informed choice • Good for women to receive information without feeling pressured to participate • Would not recruit successfully just by giving information—would need to follow up • Important to give information that is accessible to all women (languages, literacy levels, etc.) • Instagram influencers are highly regarded source of medical information for women in pregnancy—good medium to communicate research message through |

|

Invite recruiters to share anecdotes of inviting women to participate in a trial during emotionally sensitive situations 5.6 Information about emotional consequences (linked subthemes—approach to recruiting and the right participants and acceptability of the intervention) |

• Really helpful idea • Daunting when first starting to recruit—speaking with person who knows how to discuss topic makes it much easier • Good to have training on how to speak to someone in this situation • This often happens informally as every situation is different—maybe just space and time with colleagues? • Midwifing the woman—she needs us, precious relationships to nurture • Audio clips (WhatsApp notes) have been useful maybe this could be developed? |

|

Invite previous trial participants to share their experiences of being invited to a maternity care trial 5.2 Salience of consequences (linked subthemes—the ‘right’ participants and acceptability of the intervention) |

• Really important—why do not we do this more?—good opportunity to celebrate and share the findings • Does not necessarily need to be trial specific • Clinical midwives invite women back to share experiences in antenatal/postnatal groups • Women that have been through trials are our greatest asset in encouraging others to participate • People really crave human face-to-face or online experience—use Instagram? • Suggestion—using Teams or Zoom setting (similar to workshop) would be good • Current approach is old fashioned (giving leaflets, etc.) people do not communicate that way anymore |

Six additional BCTs were mentioned by participants during the discussions, all of which featured on the initial long-list generated during the mapping exercise in step 1. Five BCTs had already been excluded based on the APEASE criteria and were not carried forward. The remaining one (10.4 Social rewards) was brought forward to the next stage of development.

The APEASE criteria were applied to the aggregated findings of both co-design workshops: this produced the final list of BCTs for inclusion in the intervention (Tables 5 and 6). In total, 10 BCTs were confirmed for inclusion in the final intervention (1.2 Problem Solving; 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour; 4.2 Information about antecedents; 5.1 Information about health consequences; 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences; 5.6 Information about emotional consequence; 9.2 Pros and Cons; 10.4 Social Rewards; 11.2 Reduce negative emotions; 13.2 Reframing).

Table 5.

APEASE criteria applied by ENCOUNTER team to behaviour change techniques following co-design workshops: intervention 1

| BCT | Label | Affordability | Practicability | Effectiveness | Acceptability | Side-effects/safety | Equity | Decision Yes/no |

Reasons for exclusion/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.2 | Pros and cons | ||||||||

| Description: Ask recruiter’s list and compare advantages and disadvantages of inviting all eligible women to participate in a trial | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Perceived as helpful by most participants | |

| 1.1 | Goal setting—behaviour | ||||||||

| Description: Ask recruiters to set an agreed daily/weekly goal to invite all eligible women (not necessarily the numbers) | √ | X | - | X | - | √ | No | Negative response at workshop | |

| 1.3 | Goal setting—outcome | ||||||||

| Description: Ask recruiters to set weekly goal to have increased the number of women invited to the trial | √ | X | - | X | - | √ | No | Negative response at workshop | |

| 4.2 | Information about antecedents | ||||||||

| Description: Show recruiters a video clip of an experienced recruiter—what prompts/motivates them to invite all eligible women to a trial as well as discussing the common challenges in approaching potential participants | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | The most well received BCT at the workshop | |

| 2.3 | Self-monitoring of behaviour | ||||||||

| Description: Ask recruiters to keep a diary of each recruitment encounter or potential encounter and the outcome (perhaps limited to the first 10). Recruiters could later reflect on diary and share learnings with peers | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Well received by midwives and nurse in the workshop | |

| 1.2 | Problem solving | ||||||||

| Description: Encourage recruiters to be creative in thinking about strategies to adopt as challenges are presented i.e. “If x goes wrong, then this is what you do” | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Could fit neatly with 2.3 and the shared learnings | |

| 1.5 | Review behaviour goals | ||||||||

| Description: Regular review, with the trial team, of the changed behaviour being used by the recruiters | √ | √ | - | X | X | √ | No | No longer relevant as 1.1 and 1.3 have been excluded | |

| 1.7 | Review outcome goals | ||||||||

| Description: Trial teams carry out monthly review to reveal if all eligible women had been invited to participate in the trial. Based on outcome, recruiter and trial team could consider modifying invitation goal | √ | X | - | X | X | √ | No | No longer relevant as 1.1 and 1.3 have been excluded | |

| 10.4 | Social rewardsa | ||||||||

|

Identified as ‘creep’ BCT Description: Trial team give recruiters thank you cards/acknowledgements |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Yes | ||

aAdditional ‘creep’ BCTs that emerged during the workshop, they were identified on original ‘Long List’ but not initially proposed as intervention components during the workshop

Table 6.

APEASE criteria applied by ENCOUNTER team to behaviour change techniques following co-design workshops: intervention: intervention 2

| BCT | Label | Affordability | Practicability | Effectiveness | Acceptability | Side-effects/safety | Equity | Decision Yes/no |

Reasons for exclusion/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | Information about health consequences | ||||||||

| Description: Give recruiters information about research being part of clinical care, the importance of maternity care research, rationale for trial | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Well received in workshop | |

| 5.3 | Information about social and environmental consequences | ||||||||

| Description: Remind recruiters that all eligible women are entitled to be asked to participate in the trial, and by inviting all eligible women, it means the sample is more likely to be representative, maybe greater chances of trial success, impact on research | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Well received at workshop | |

| 11.2 | Reduce negative emotions | ||||||||

| Description: Overcome recruiters’ feelings of apprehension from getting the feeling or the ‘vibe’ that the woman may not be interested in participating in the trial by reminding them it’s OK just to invite women by giving them information | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Well received at workshop | |

| 13.2 | Reframing | ||||||||

| Description: Educating recruiters that intervention is about ‘inviting’ (offering the chance) and not necessary recruiting all eligible women. Offering the opportunity to take part in research in the way that health advice/information is offered to everybody | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Important concept to the aim of this intervention | |

| 5.6 | Information about emotional consequences | ||||||||

| Description: Invite recruiters to share anecdotes of past emotionally sensitive situations where women were glad to be invited to participate in the trial and may have found inclusion helpful or comforting in their situation | √ | √ | - | √ | √ | √ | Yes | Well received at workshop | |

| 5.2 | Salience of consequences | ||||||||

| Description: Invite previous trial invitees to share their experiences of being approached to take part in a trial in maternity care (via narrative testimonial, short video clip) | √ | - | - | √ | √ | √ | No | Well received at workshop. Exclude as not target behaviour and difficult to ethically justify in APEASE | |

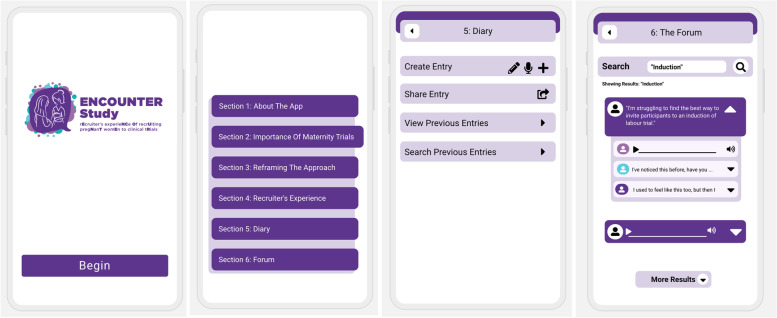

Our choice of intervention delivery was informed by comments made by participants about the convenience and helpfulness of using mobile phone apps in their working practice and the high number of BCTs we wished to incorporate into one intervention. We developed a prototype app to deliver the intervention in this setting (Fig. 2). It should be noted, however, that in this study, we were interested in the BCT content of the intervention, rather than the technological functions of the app, and therefore, we focused predominantly on content during acceptability and feasibility assessment.

Fig. 2.

ENCOUNTER app prototype screenshots

Step 3—Evaluating acceptability and feasibility of the proposed intervention

The final step in the development process involved assessing the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention using an online survey capturing the opinions of key stakeholders. Fifty-four participants, twenty-five from Ireland and twenty-nine from the UK, initiated the online questionnaire, providing demographic information and answering the two statements questions. However, nine participants did not proceed beyond the two statement questions, resulting in a total of 45 completed questionnaires (reported in section below). Responses were provided by MHCPs, including midwives (clinical and research), research nurses, doctors (obstetricians and other specialties), allied health professionals, and maternity trial team members. All respondents described themselves as white and were predominately female 92.6% (n = 50). Research midwives represented the largest group of respondents (n = 25, 46%), followed by clinical midwives (n = 8, 15%) and trial team members (n = 8, 15%). Detailed participant characteristics are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Recruitment intervention survey: participant characteristics

| Total survey responses—n = 54 (Ireland—n = 25, UK—n = 29) Total surveys completed—n = 45 n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Clinical midwife | Research midwife | Clinical nurse | Research nurse | Doctor (obstetrics) | Doctor (other) | Allied health professional | Trial team member |

| Survey responses initiated | 8 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Dropped out before TFA questions | 1 | 3 | - | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Completed TFA questions | 7 | 22 | - | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Based in | ||||||||

| Ireland | 7 (71.43) | 5 (20) | - | 1 | 2 (33.33) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 4 (50) |

| UK | 1 (28.57) | 20 (80) | - | 0 | 4 (66.67) | 0 | 0 | 4 (50) |

| Trial experience | ||||||||

| < 2 years | 4 (50) | 4 (16) | - | 0 | 1 (16.67) | 0 | 0 | 2 (25) |

| 2–5 years | 0 | 9 (36) | - | 0 | 2 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | 0 | 0 |

| > 5 years | 4 (50) | 12 (48) | - | 1 (100) | 3 (50) | 1 (33.33) | 3 (100) | 6 (75) |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25–34 | 0 | 4 (16) | - | 0 | 2 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | 2 (66.67) | 3 (37.5) |

| 35–44 | 3 (37.5) | 8 (32) | - | 0 | 0 | 1 (33.33) | 0 | 1 (12.5) |

| 45–54 | 4 (50) | 10 (40) | - | 1 | 2 (33.33) | 0 | 1 (33.33) | 3 (37.5) |

| 55–64 | 1 (12.5) | 3 (12) | - | 0 | 2 (33.33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) |

| 65 + | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 8 (100) | 25 (100) | - | 1 (100) | 6 (100) | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 8 (100) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 0 | 1 (4) | - | 0 | 1 (16.67) | 0 | 1 (33.33) | 2 (25) |

| Female | 8 (100) | 24 (96) | - | 1 (100) | 6 (83.33) | 3 (100) | 2 (66.67) | 6 (75) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Response to statement questions | ||||||||

| “Improving recruitment to trials in maternity care is something I care about” | ||||||||

| Strongly agree | 37.5% (3) | 80 (20) | - | 0 | 83.33% (5) | 50% (2) | 100% (3) | 100% (8) |

| Agree | 62.5% (5) | 20 (5) | - | 0 | 16.67% (1) | 50% (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutral | 0 | 0 | - | 100% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| “I have a role to play in helping to ensure all eligible people are invited to participate in a clinical trial in maternity care” | ||||||||

| Strongly agree | 0 | 76 (19) | - | 0 | 66.67% (4) | 50% (2) | 66.67% (2) | 100% (8) |

| Agree | 100% (8) | 24 (6) | - | 100% | 33.33% (2) | 50% (2) | 33.33% (1) | 0 |

| Neutral | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strongly disagree | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In response to the first statement question on the survey: “Improving recruitment to trials in maternity care is something I care about”, over 98% (n = 53) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed. In response to the second statement: “I have a role to play in helping to ensure all eligible people are invited to participate in a clinical trial in maternity care”, 100% (n = 54) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement.