Abstract

In the last decade, there has been an increase in publications on technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Virtual reality based assessments and intervention tools are promising and have shown to be acceptable amongst individuals with ASD. This scoping review reports on 49 studies utilizing virtual reality and augmented reality technology in social skills interventions for individuals with ASD. The included studies mostly targeted children and adolescents, but few targeted very young children or adults. Our findings show that the mode number of participants with ASD is low, and that female participants are underrepresented. Our review suggests that there is need for studies that apply virtual and augmented realty with more rigorous designs involving established and evidenced-based intervention strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10803-021-05338-5.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Virtual reality, Augmented reality, Social skills

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD; autism from hereon) refers to a spectrum of neurodevelopmental conditions marked by impairments in social communication and the presence of repetitive behavior patterns and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals with autism are heterogeneous in their levels of general functioning. For example, some individuals with autism develop advanced expressive language ability, show more subtle difficulties in social interactions, and their repetitive behavior patterns are associated with adherence to routines in their daily life (Horwitz et al., 2020). Others may have impaired expressive language, extensive difficulties with social interaction, and their repetitive behavior takes the form of stereotyped movements (Hattier et al., 2011; Kjellmer et al., 2012).

Already at an early age, individuals with autism show tendencies of orienting themselves mostly to non-social stimuli, at the expense of social stimuli, and this orientation can have cascading effects on their social and linguistic development (Gale et al., 2019). The preference for non-social stimuli and restrictive behavior might be related to challenges for individuals with autism when encountering society. Individuals with autism commonly have lower quality peer friendships with fewer reciprocal relationships and lower acceptance by their classmates (Chamberlain et al., 2007). Difficulties individuals with autism experience in educational settings are often related to making sense of social stimuli and unpredictable social environments (Lüddeckens, 2020). In fact, individuals with autism show significantly more school refusal behavior than their neurotypical peers (Munkhaugen et al., 2017). A high prevalence of school refusal behavior can possibly be attributed to difficulties experienced at school, perhaps due to social difficulties in interaction with peers and teachers. Many individuals with autism experience bullying during their school years (Skafle et al., 2019).

The social communicative impairments defining the disorder makes social skills an important target in educational interventions (Wolstencroft et al., 2018). Many different definitions of social skills have emerged in the literature (Wolstencroft et al., 2018). The term social skill is used interchangeably with other terms, such as social competence and social functioning (see Cordier et al., 2015). In this review, we define the term social skills broadly as a behavior that is performed in a social context and involves interpersonal engagement (Cordier et al., 2015; Wolstencroft et al., 2018). This engagement is not restricted to live human-to-human interactions in this study since we also include human–computer interactions (e.g., engagement with robotic avatars etc.).

Technology, such as virtual reality (VR), seems promising in regard to practicing social skills (Howard & Gutworth, 2020), and represent cost effective ways of meeting the social and, ultimately, the educational needs of individuals with autism. VR technology displays artificial environments that may emulate real world scenarios by generating visual and auditory stimuli, with realistic images or other sensations that can surround the end user. Augmented reality (AR) provides artificial visual and auditory information superimposed on the veridical, real-world environment. AR is often presented through tablets and smartphones in addition to AR-glasses. VR can be presented with various tools such as Head-Mounted Displays (HMD) and Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE), and even desktop or laptop computers. VR HMDs are goggles presenting virtual environments that provide a sense of surrounding the user completely. CAVE is a tool that uses two-dimensional projected displayed arranged around the user to present a pseudo three-dimensional environment. VR/AR and CAVE all provide opportunities where the users can interact through specialized controllers, computer vision techniques (e.g., through motion capture techniques), and other computer-based sensing systems (e.g., eye-tracking, speech recognition etc.).

In the last decade, the number of publications including computer-based or VR/AR assessments and interventions involving individuals with autism has increased significantly (Dechsling et al., 2020). The majority of studies on autism and VR/AR focus on social and emotional skills (Lorenzo et al., 2018; Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018), with multiple studies reporting benefits through skill training (e.g., Didehbani et al., 2016; Kandalaft et al., 2013; Maskey et al., 2014; Newbutt et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017). In addition, computer technology methods have been described as highly motivating for many individuals with autism (Dechsling et al., 2020; Newbutt et al., 2016, 2020; Yang et al., 2017).

A few previous reviews have summarized evidence on VR and assessments or interventions on social skills for individuals with autism. Miller and Bugnariu (2016) conducted a systematic literature search on autism and VR. The included 29 studies were published before July 2015 and focused on both assessments and interventions of social skills and graded them in different levels of the immersion on the apparatus used. The authors presented a useful table on classification of virtual environment characteristics by levels of immersion. An example of a low immersion virtual environment would be one delivered via computer monitor or tablet; a high immersion environment would be one presented through an HMD.

Mesa-Gresa and colleagues conducted a systematic review on the effectiveness of various types of VR-interventions for children with autism, including social skills (Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018), while Lorenzo et al. (2018) focused on identifying variables used in studies that applied VR for students with autism. After excluding studies with participants above 18 years of age in their review, Mesa-Gresa et al. (2018) included 31 studies and concluded that there is moderate evidence for the effectiveness of VR-interventions for children with autism. Lorenzo et al. (2018) on the other hand, included 12 studies and concluded that immersive virtual reality is a promising tool for improving the skills of students with autism. Nevertheless, they pointed out several weaknesses in the studies included, such as small sample sizes and control groups consisting of individuals without autism.

These reviews had some methodological issues limiting their results in terms of providing an exhaustive overview, such as the choice to exclude some age-cohorts. In addition, both reviews used a limited set of search databases. Mesa-Gresa et al. (2018) only searched three databases (Web of Science, PubMed and Scimago Journal & Country Rank), and not psychology and education specific databases such as PsycInfo and ERIC. Lorenzo et al. (2018) did not report which databases they searched. Based on the information they provided, it seems likely that only Web of Science was used with a search string limited to only two search terms.

The rapid development of the research field on autism and VR/AR (Dechsling et al., 2020) combined with the extensive number of journals publishing studies in this domain (both technology- and autism specialized as well as general journals), and the narrow search strategies in previous reviews, warrants a review to map and evaluate the extant research. A transparent review, targeting VR/AR interventions on social skills for individuals with autism, using more exhaustive search string and a more diverse set of search platforms than previous reviews. Scoping reviews are useful when navigating a complex and heterogeneous literature and are commonly conducted to summarize and explore the breadth and depth of the literature, identify gaps, and inform future research (Peters et al., 2020; Tricco et al., 2016).

The objectives of this review are to provide a comprehensive summary of studies where VR/AR-interventions have been used to improve social skills in individuals with autism; to evaluate the literature including the methodology used and the social skills targeted; and to identify research gaps in the literature.

Method

Search Strategy

An information retrieval specialist searched the databases: PsycINFO, PubMed, ERIC, Education Research Complete, IEEE Xplore, and the search platform Web of Science, on February 3rd, 2021. The following search string from Dechsling et al. (2021) was used: (Pervasive development disorder OR pdd OR pdd-nos OR pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified OR autism OR autistic OR autism spectrum disorder OR autism spectrum disorders OR Asperger OR asd OR autism spectrum condition* OR asc AND Virtual Reality OR vr OR hmd OR Head-mounted display OR Immersive Virtual Environment OR Augmented Reality OR Artificial Reality OR Oculus OR Immersive Technolog* OR Mixed Reality OR Hybrid Reality OR Immersive Virtual Reality System OR 3D Environment* OR htc vive OR cave OR Virtual Reality Exposure OR vre). The first and second author also searched the references in other reviews (Lorenzo et al., 2018; Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018; Miller & Bugnariu, 2016) for potential additional studies. No limitations regarding language or publication year were applied in the search, but the search was limited to peer-reviewed publications and to publications that included human participants.

Inclusion and Exclusion of Studies

The study inclusion criteria when screening were as follows: (1) Peer-reviewed studies in English published 2010 or after, (2) included participants diagnosed with autism, (3) included interventions on social skills as defined below (4) used VR/AR-equipment (not restricted to HMD), and (5) involved a human–computer interaction to be evaluated as a VR/AR-intervention. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Grey literature (e.g., dissertations, posters, etc.), (2) studies published before 2010, (3) studies not written in English, (4) studies where the participants did not act or interact in the virtual environment, (4) studies where VR/AR skill improvement was not directly directed to individuals with autism (e.g. VR teaching of professionals working with various populations).

The inclusion criteria on social skills were widely defined as studies with the aim or outcome regarding some social interactions, such as communication, emotion recognition, joint attention, pretend play, and job interview skills. Feasibility studies, pilot studies, and peer-reviewed conference papers were included if they reported interventional data on participants.

Screening and Data Extraction

The first and second author screened the publications from the search consulting the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). After removing duplicates, the initial search results were screened for titles and abstracts by the first and second author for relevance within ASD* and Virtual Reality*, and then selected studies were eventually screened for full text articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussions.

From the included studies, we extracted the following information: authors, publication year, study type (e.g., case-study, pilot-study, randomized controlled trials etc.), duration and aim of the intervention. Information about sample size, age range, and intelligence quotient (IQ) were also extracted, whenever applicable. In addition, we replicated the coding process from Dechsling et al. (2020) to assess the reported acceptability (“i.e., participant reports on usability, enjoyment, likeability, tolerability and so on”, p. 163) data in the included studies.

Results

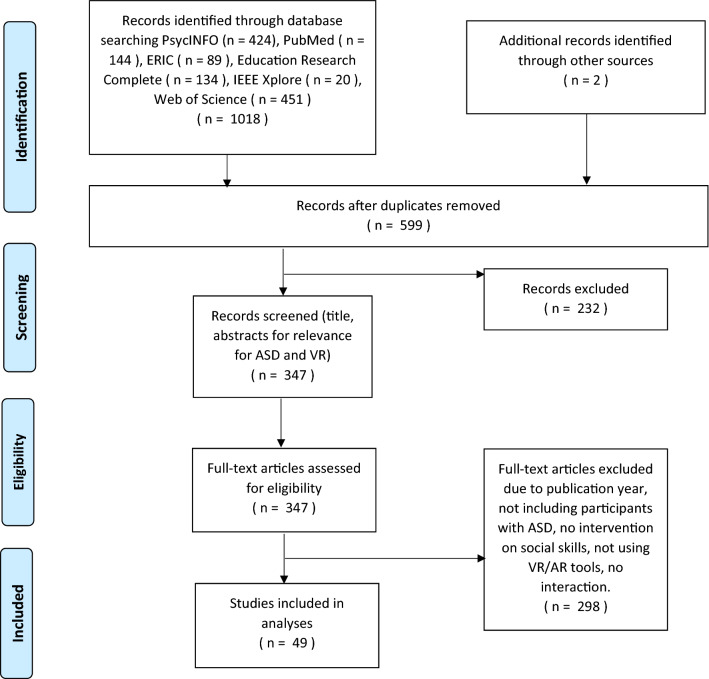

After removing duplicates, the initial search resulted in 599 publications and the screening resulted in 49 publications meeting the inclusion criteria. See Flow chart (Fig. 1) for the details. One relevant article was included after manually searching the reference lists of included publications and the aforementioned reviews. The publications are published in psychology/psychiatry journals (19), educational journals (8), information technology journals (6), hybrid journals of education and technology (11), and the rest in miscellaneous journals (e.g., biomedicine, pediatrics, sociology). The matrix in the Supplementary Appendix contains an overview of the included articles.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection process of included studies

The total number of participants with autism in the included publications was 652. The gender distribution of the participants in this sample were male n = 604, and female n = 48, meaning 7.4% of participants were female (which is lower than the reported male-to-female gender ratio of approximately 3:1 in autism [Loomes et al., 2017]). Note that the reported number of female participants in this total sample may be inaccurate due to 12% of the studies not reporting gender distribution.

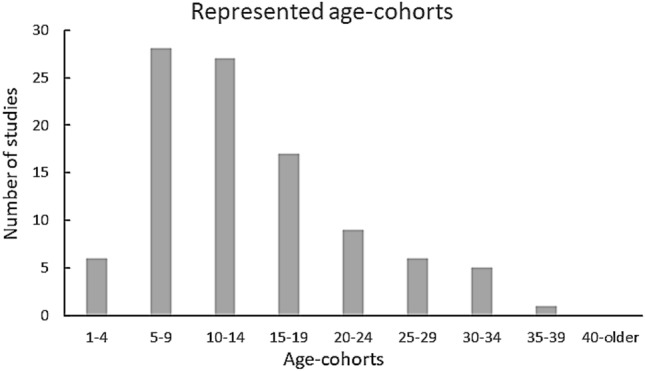

The mean and median number of participants with autism per publication were 13.3 and 10.0 respectively, range was 2–99 (note that if we exclude Burke et al. (2020) the range would be 2–40), and the mode number was 3 participants. The age of participants with autism ranged from 2 to 38 years old. The studies included mainly children and adolescents, with approximately 16% of the studies involving adult individuals with autism (20–38 years of age, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A bar chart of the number of studies and the respective represented age-cohorts. One to 4-year old participants appear in six studies, 5–9 and 10–14-year old participants appear in just over 25 studies, 15–19-year old participants appear in approximately 17 studies, 25–29- and 30–34-year old participants appear in approximately five studies each, and only one study include participants from 35 or older.

The interventions were mostly directed towards individuals with intellectual functioning above the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) cut-off score for intellectual disability (IQ ≥ 70), and around the general population average. However, scarcely above half of the studies in the sample reported participants’ IQ-scores.

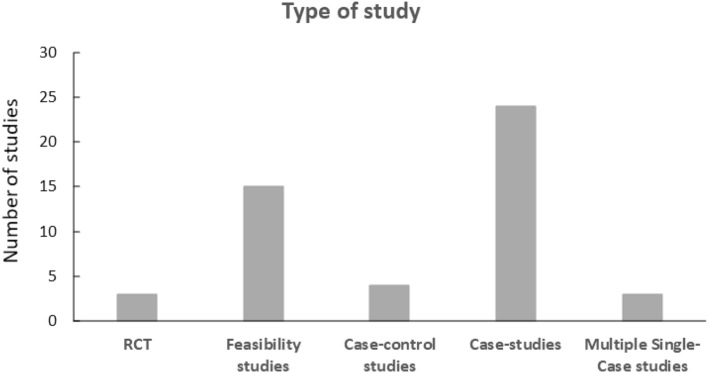

The majority of studies were case-studies and feasibility (pilot/exploratory) studies (Fig. 3), while only three randomized controlled trials (Smith et al., 2014; Strickland et al., 2013; White et al., 2016). Mean duration of the interventions was 8.75 weeks, ranging from < 1 to 40 weeks.

Fig. 3.

A bar chart over different types of study. Three RCT, fifteen feasibility studies, four case-control-studies, 24 case-studies, and three multiple single-case studies.

The studies in our sample targeted: (1) various social interaction skills (e.g., Ke & Moon, 2018; Lorenzo et al., 2019), joint attention (e.g., Amaral et al., 2018; Ravindran et al., 2019), job interview skills (e.g., Burke et al., 2018, 2020; Smith et al, 2014; Strickland et al., 2013; Ward & Esposito, 2019), pretend play (e.g., Bai et al., 2015), collaboration and communication (Bernardini et al., 2014; Crowell et al., 2019; Malinverni et al., 2017; Moon & Ke, 2019; Trepagnier et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2018). Or (2) social knowledge such as emotion recognition (Chen et al., 2016; Didehbani et al., 2016; Serret et al., 2014), broader emotional competence (Lorenzo et al., 2016), and social cognition (Chen et al., 2016). Or (3) a combination of both such as emotion recognition and responses (Chen et al., 2015; Ip et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017), social attention and gestures (Lee, 2020; Lee et al., 2018), or social understanding and cognition (Cheng et al., 2015; Kandalaft et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017, 2018).

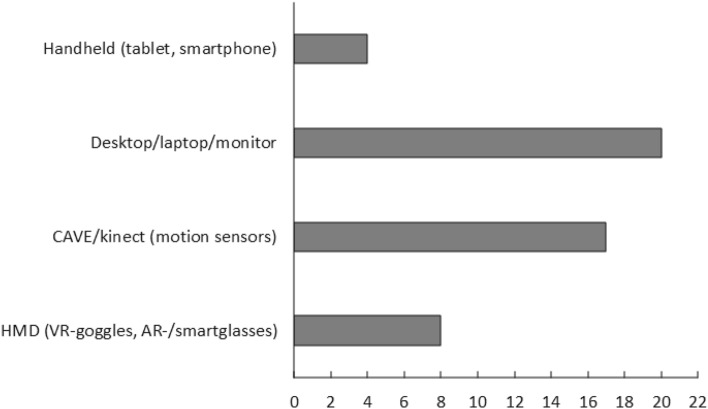

The software and/or hardware that is used in the different studies are listed in Table 1 and reveal a wide range of equipment used aiming at providing a virtual reality environment or augmented reality (Fig. 4). Several levels of immersion were covered by this literature with low immersion apparatus and environments such as monitor-based interventions, and high-immersion apparatus such as VR in HMDs and CAVE. In between, one can find the use of motion cameras (Kinect), laptops with or without additional equipment such as joysticks, headsets and different kinds of software. Eight of the included studies used HMD’s, either AR-goggles, smart-glasses or VR-goggles.

Table 1.

Included studies

| Authors. (year), country of study origin | Study type/duration | Aim | Methodology | N* (f**) | Participant age range (mean IQ) | HMD/equipment used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amaral et al. (2018), Portugal | Feasibility study/17 weeks | Joint attention | Joint attention through EEG brain computer interface | 15 (0) | 16–38 (102.53) | Yes/Oculus Rift + g.Nautilus EEG system |

| Babu and Lahiri (2020), India | Case–control study/80 min | Social interaction | Virtual reality multiplayer interaction platform with eye-gaze monitoring | 18 (n/a) | n/a mean age 9.8 (n/a) | No/eye-tracker, multiplayer interaction framework |

| Bai et al. (2015), United Kingdom | Case-study (within subject)/n/a | Pretend play | Pretend play in an AR open-ended environment | 12 (0) | 4–7 (n/a) | No/AR monitor + logitech webcam + marker-based tracking |

| Beach and Wendt. (2016), USA | Case-study (qualitative)/4 weeks | Social interaction | Social skills through observing scenarios | 2 (0) | 15–18 (n/a) | Yes/Oculus Rift |

| Bernardini et al. (2014), United Kingdom | Feasibility study/6 weeks | Social communicative behaviors | Training social communicative behavior with virtual agents | 19 (1) | 4–14 (n/a) | No/Multitouch LCD display with eye-gaze tracking |

| Burke et al. (2018), USA | Case-study/14 weeks | Job interview skills | Job interview skills using Virtual Interactive Training Agents | 22 (n/a) | 19–31 (n/a) | No/Kinect + TV-screen |

| Burke et al. (2020), USA | Case-study (within subject)/22 weeks | Job interview skills | Job interview skills using Virtual Interactive Training Agents | 99 (n/a) | n/a mean age 21.71 (n/a) | No/laptop, monitor with camera sensor |

| Chen et al. (2015), Taiwan | Case-study/6 weeks | Promote emotional expression and social skills | Promote emotional expressions through AR self-facial modeling | 3 (0) | 10–13 (100.67) | No/monitor + webcam |

| Chen et al. (2016), Taiwan | Case-study/7 sessions | Improve perception and judgement of facial expressions and emotions | Improve perceptions of non-verbal cues through AR video modeling | 6 (0) | 11–13 (103.66) | No/tablet |

| Cheng et al. (2015), Taiwan | Case-study (single subject)/6 weeks | Enhance social understanding and social skills | Enhance social skills using a 3D-social understanding | 3 (0) | 10–12 (82) | Yes/VR-goggles + laptop |

| Cheng et al. (2010), Taiwan | Case-study/23 weeks | Enhancing empathy (instructions) | Enhance empathy and social cognitions through collaborative and virtual environment | 3 (0) | 8–10 (104) | No/laptop computer |

| Cheng and Huang. (2012), Taiwan | Case-study/12 weeks | Joint attention | Joint attention through a virtual reality environment | 3 (0) | 9–12 (61.67) | No/Computer screen and data glove |

| Cheng and Ye. (2010), Taiwan | Feasibility (Pilot-study)/3 weeks | Social competence | Training social and emotional skills through a virtual learning environment | 3 (0) | 7–8 (102.33) | No/laptop computer |

| Chung et al. (2015), USA | Feasibility study (proof-of-concept)/5 weeks | Social behavior in cooperation in videogame | Peer cooperation in AR-videogame | 3 (0) | 8–12 (n/a) | No/AR game (Kinect) |

| Crowell et al. (2019), Spain | Case-study/120 min | Social skills, collaboration | Enhancing social skills in a virtual full-body interaction environment | 25 (0) | 4–14 (> 70) | No/Kinect |

| Didehbani et al. (2016), USA | Case-study/5 weeks | Emotion recognition and social attribution | Enhancing social skills through interactive VR-learning scenarios | 30 (4) | 7–16 (112.6) | No/Computer screen |

| Halabi et al. (2017), Qatar | Case-study/2 sessions of 20 min | Social interaction and communication | Enhancing communication skills through VR | 3 (0) | 4–6 | Yes/CAVE VR + Oculus Rift |

| Herrero and Lorenzo (2020), Spain | Case–control study/10 sessions | Social and emotional abilities | Social interaction with avatars in a virtual environment | 14 (1) | 8–15 (approx. average) | Yes/Oculus Rift, smartphone |

| Ip et al. (2018), Hong Kong | Case-study/14 weeks | Enhance emotional and social adaption skills | Enhance social skills and emotion regulation in an immersive VR environment | 36 (5) | 6–12 (n/a) | No/4-side CAVE VR system |

| Kandalaft et al. (2013), USA | Feasibility study/5 weeks | Enhancing social skills, social cognition, and social functioning | Enhancing various social and social cognitive skills through VR-scenarios | 8 (2) | 18–26 (111.9) | No/Computer screen and VR software |

| Ke and Im. (2013), USA | Case-study/5 weeks | Social interaction | Social interaction tasks in VR-based learning environment | 4 (2) | 9–10 (n/a) | No/Computer screen and VR software |

| Ke and Lee. (2016), USA | Feasibility—exploratory case study/5 weeks | Social behavior in game play | Enhancing social skills through VR collaboration game | 2 (0) | 9–10 (n/a) | No/OpenSim |

| Ke and Moon. (2018), USA | Case-study/16 to 31 45–60 min sessions | Social interaction | Enhancing social skills through VR collaboration game | 8 (1) | 10–14 (> 70) | No/OpenSim |

| Ke et al. (2020), USA | Multiple single-case study/12 weeks | Social skills and role-play | 7 (1) | 10–14 (n/a) | No/OpenSim | |

| Lee. (2020), Taiwan | Multiple single-case study/8 sessions | Judge other people’s social interaction and respond appropriately | Improving performance and understanding of body gestures through AR-role-play and tutoring | 3 (1) | 7–9 (102.3) | No/Kinect Tracking system |

| Lee et al. (2018), Taiwan | Case-study/6 weeks | Teach how to use social cues | Teaching social skills through social scenarios in AR | 3 (1) | 8–9 (93.3) | No/tablet, TV-screen and concept map |

| Liu et al. (2017), USA | Feasibility study/1 session | Emotion Recognition, Social Attention, Eye-contact and self-regulation | Enhancing social gaze and emotion recognition through AR-games | 2 (0) | 8–9 (n/a) | Yes/brain power system (BPS) + smartglasses |

| Lorenzo et al. (2019), Spain | Feasibility study (preliminary)/20 weeks | Social skills | Enhancing social skills through AR-based social activities | 5 (1) | 2–6 (n/a) | No/AR on smartphone |

| Lorenzo et al. (2016), Spain | Case–control/40 weeks | Emotional competence | Learning emotional scripts in VR | 40 (11) | 7–12 (n/a) | No/Semi-cave, robot and camera |

| Lorenzo et al. (2013), Spain | Case-study/40 weeks | Social competence | Training social and emotional skills in a VR-based school setting | 20 (4) | 8–15 (n/a) | No/3D IVE + Kinect + 3D glasses |

| Malinverni et al. (2017), Spain | Feasibility (Exploratory case study)/4 sessions | Social initiation | Enhancing social skills through VR collaborative game (PICO) | 10 (0) | 4–6 (95.9) | No/Pico's adventure Full body interact. Kinect |

| Milne et al. (2010), Australia | Case-study/n/a | Conversational skills and dealing with bullying | Conversational skills and dealing with bullying through virtual agent tutoring | 14 (n/a) | 6–15 (n/a) | No/desktop computer and webcam |

| Moon and Ke. (2019), USA | Feasibility (mixed methods)/6 sessions | Social skills; responding, initiating, negotiating and collaborating | Social skills training through social role-play in VR-game | 15 (2) | 10–14 (> 70) | No/open simulator |

| Parsons. (2015), United Kingdom | Case-study/2 weeks | Communicative perspective-taking skills | Social interaction in a collaborative VRE | 6 (0) | 10–13 (96) | No/laptop computers and microphone headsets |

| Ravindran et al. (2019), USA | Feasibility (pilot study)/5 weeks | Joint Attention | Training joint attention in VR | 12 (0) | 9–16 (n/a) | Yes/HMD cardboard with smartphone, tablets |

| Serret et al. (2014), France | Feasibility study (pilot-study)/4 weeks | Emotion recognition | Training emotion recognition through Serious game | 33 (2) | 6–17 (70.5) | No/computer game with a gamepad |

| Smith et al. (2014), USA | Randomized control trial/10 h | Job interview skills | Computer simulation of job interviews in VR | 26 (n/a) | 18–31 (n/a) | No/computer |

| Stichter et al. (2014), USA | Case-study/17 weeks | Social competence | Training social and emotional skills through distance education in iSocial | 11 (0) | 11–14 (99.55) | No/computers with headset |

| Strickland et al. (2013), USA | Randomized study/n/a | Job interview skills | Computer simulation of job interviews in VR | 11 (0) | 16–19 (n/a) | No/computer |

| Trepagnier et al. (2011), USA | Feasibility study/2 weeks | Conversational skills | Training of conversational skills through computer simulation | 16 (1) | 16–30 (109.4) | No/computer screen simulation |

| Tsai et al. (2020), Taiwan | Multiple single-case design/5 weeks | Emotion recognition | Role-play and observation | 3 (0) | 7–9 (87) | No/CAVE-like environment using Kinect |

| Uzuegbunam et al. (2018), USA | Feasibility (Pilot-study)/7 weeks | Social greeting behavior | Social greeting behavior through social narratives | 3 (0) | 7–11 (n/a) | No/touchscreen computer with Kinect v2 |

| Vahabzadeh et al. (2018), USA | Feasibility study/6 weeks | Irritability, hyperactivity, and social withdrawal | Training on facial attention, mutual gaze and emotion recognition through smartglasses with social cues | 4 (0) | 6–8 (n/a) | Yes/smartglasses |

| Wang et al. (2017), USA | Case-study/18 weeks | Verbal and nonverbal social interaction | Training social and emotional skills through iSocial | 11 (0) | 11–14 (> 75) | No/3D VLE, computer screen |

| Ward and Esposito. (2019), USA | Exploratory study—case study/mean 129 min | Job interview skills | Computer simulation of job interviews in VR | 12 (2) | 18–22 (95.6) | No/Chromebook, headset w/microphone |

| White et al. (2016), USA | Randomized control trial/10–14 weeks | Social competence and self-regulation | Training of social interaction and emotion recognition in VE | 8 (3) | 19–23 (126.75) | No/desktop computer, tablet and EEG |

| Yang et al. (2017, 2018), USA | Case-study/5 weeks | Social cognition | Training social and emotional skills in immersive role play | 17 (2) | 18–31 (109.65) | No/computer and fMRI |

| Zhang et al. (2018a, 2018b), USA | Case–control study—Feasibility study/50 min | Collaborative interaction and verbal communication | Social communication through collaborative playing in a virtual environment | 7 (1) | 7–17 (191.06) | No/Desktop computers |

| Zhao et al. (2018), USA | Case-dyad study—feasibility study/n/a | Communication and collaboration | Collaborative skills through game-playing in VR | 12 (n/a) | n/a mean age 12.20 (n/a) | No/motion controller, eye tracking, headset, webcam and computer |

Table of the included studies

*Total number of participants with ASD (all genders) in the study, this number is excluding the other participants in the respective studies

**Number of female participants. This number is also included in the total number and should not be added to the total number of participants

Fig. 4.

A bar chart of the different kinds of hardware used. Four studies using handheld equipment like tablets or smartphones. Twenty studies using desktops, laptops, or monitors. Seventeen studies using CAVE or Kinect (with motion sensors). Eight studies using Head-Mounted Displays such as VR-goggles or AR-goggles/smartglasses

Acceptability was reported in 21 of the 49 included studies. None of the studies reported negative evaluations, while 81% of the studies reported positive evaluations, and 19% reported inconclusive evaluations.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to identify intervention studies using VR/AR to improve social skills for individuals with autism. We identified 49 studies with various focus, intervention types, and technology within the scope of autism and social skills. Although this field of research is young, the median and mode number of participants across studies are noteworthy as the number of participants in such quantitative studies could be quite essential as a prerequisite for reliability and validity. Apart from eight studies like for example Burke et al. (2020), Ip et al. (2018), and Lorenzo et al. (2016), most of the studies are characterized with a small number of participants and short duration of the interventions.

Another remarkable finding is that the female participants with autism are underrepresented in our sample considering the male-to-female ratio within the autism spectrum. There might be several reasons why female participants are underrepresented. Some suggest females with autism to have less overt challenges related to social interaction, or that there are differences in social strategies between genders which makes the challenges more difficult to detect in females (Hiller et al., 2016), and that such strategies might camouflage other symptoms (Rynkiewicz et al., 2016). Therefore, it could be issues related to the likelihood of females being discovered in a selection process. However, May et al. (2016) found no differences in social ability between genders with autism, but some differences in communication ability, so there seems to be no reason to exclude females from this field of research based on differences in symptoms between genders. For example, Kanfiszer et al. (2017) interviewed several women with autism that explained challenges in daily life due to lack of skills and confidence when interacting with others. It is of course important to remember that such challenges should be met with both enhancing the individual’s skills, and with an increased awareness by the society. We have pointed to the novelty and rapid growth of the research field on social skills intervention in VR/AR, and as the evidence syntheses are emerging, there is a risk of unnoticed gender bias being part of such intervention practices. The underrepresentation of females should be seen as one shortcoming within this research area. Future research should have a greater emphasis and focus on recruiting female participants to balance the gender representation according to the gender ratio. It also calls for an investigation of which factors are present during the recruitment and selection process of participants, and furthermore investigations on elements important for females using VR/AR.

Further, this review shows that very few studies include individuals scoring below the threshold for an Intellectual Disability (ID) diagnosis. A selection bias of participants above this threshold for ID is found in most areas of autism research (Russell et al., 2019), and it seems that social skills interventions using VR/AR are no exception. Our findings could therefore be argued to complement Russell et al.’ (2019) and add this research area of technological interventions to the list of selection biased autism research.

Most of the studies focus on training various skills for social interaction. Play skills and job-related social skills are subdomains with few VR-intervention studies while job-interview skills are more frequent. There might be several factors that could influence the difficulties in implementing and intervening play skill-training into the computerized virtual environment. For instance, play skills are traditionally most relevant for younger children, which are least likely to tolerate the equipment, and understand and act upon the virtual environment. Interventions on job-related social skills are on the other hand an up-and-coming area of research (Grob et al., 2019). Emotional skills however, a domain that has been popular in computer-based interventions for individuals with autism (Ramdoss et al., 2012), are targeted by fewer studies included in this review. This could perhaps be because the development of VR/AR interventions have focused on skills where the traditional computer-based interventions fall short.

It is difficult to compare studies on social skills due to inconsistent definitions and intervention strategies (Ke et al., 2018). Technology-based interventions on social skills are no exception given the number of feasibility-, usability-, and pilot-studies in our overall sample, which confirms that the research field is still youthful. The novelty of the field can also explain the relatively low number of participants in most of the studies. There is a need for studies with more participants, which also use participants with autism as controls as opposed to using participants without autism. Only one study (Amaral et al., 2018) included participants in the age cohorts above 31 years old which indicates that the research field of using VR/AR on social skills with adults with autism over 30 is an untouched research area.

A variety of methods should be used when establishing causation since no method can reveal all relevant information (Anjum et al., 2020). Variation in types of studies should be considered a strength in evidence-based approaches. Since the majority of studies in our review are case- or feasibility studies, there is a need for more randomized controlled trials, which take into account necessary quality considerations (see for example Sandbank et al., 2020), to conclude on the effectiveness of using VR/AR. However, more replication studies, and studies using statistical methods developed for trials using rigorous single-case and multiple single-case designs (e.g., Shadish et al., 2014) can also contribute to building the evidence base in this research area. We welcome a diversity of studies which will impact the rigour and the generalizability of research applying VR/AR for individuals with autism.

The recency of the field can also explain the variety of methodology applied in the different studies in our sample. A variety of methodology is not a problem in itself, rather a strength once there is a sufficient number of studies converging towards the same outcome. However, an approach on using VR/AR in already established and evidence-based interventions might be warranted. For instance, Sandbank et al. (2020) concluded in their meta-analysis that there is a need for connecting technological tools with established intervention approaches and theoretical groundwork. Dechsling et al. (2021) provide examples on how to apply VR in Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBI; see Schreibman et al., 2015), the intervention approach considered most promising for helping children with autism in regard to social communication (Sandbank et al., 2020). Researchers and interventionists using VR/AR-technology should look at the most promising intervention approaches available, such as NDBI, when developing their intervention protocols and hereunder software development, with appropriate cultural adjustments. To obtain this there might be a need for clinical researchers and technology researchers to collaborate across disciplines in developing and designing robust VR/AR intervention studies. But most importantly, researchers should focus on involving individuals with autism in decision-making and development of such studies and technology (Parsons et al., 2020). In addition, strategies on assessing acceptability and stakeholder’s opinions should be implemented.

After summarizing the reports of participants with autism, across 63 studies utilizing VR/AR/computer-based tools in miscellaneous ways, Dechsling et al. (2020) found that computer-based equipment and HMDs were feasible and widely accepted amongst individuals with autism. Those findings are in accordance with the reports from the sample in our review showing a high acceptance rate among the studies reporting acceptability. However, an important note is that only 43% of the studies report such data. Recent findings from Newbutt et al. (2020) suggest further that individuals with autism prefer HMDs with controllers rather than tablets and HMDs with less opportunities to interact. However, HMDs such as VR/AR-goggles are only used in 16% of the studies in our overall sample. This indicates a need for more research on the effectiveness using high-immersive technology, in line with the conclusions of Miller and Bugnariu (2016). AR-/smartglasses are used in very few studies and research should investigate for example whether such glasses could be beneficial in aiding individuals with social cues in daily social encounters. Further considerations regarding cost and benefits using high-immersive versus low-immersive technological tools both in research and clinical practice should also be done, as well as other normative considerations (Dechsling et al., 2020). Individual considerations should be taken into account when applying various technologies. Some individuals may for example have sensory issues that makes a high immersive CAVE more feasible than HMDs (Dechsling et al., 2021).

The number of studies found both in computer-related journals and autism related journals shows the need for a broad search in databases and journals when reviewing studies on VR/AR, and autism. Our review identified a higher number of studies than the previous reviews, indicating a rapid growth of research in this area. This growth can be illustrated by the fact that the studies published from 2018 represent 41% of the total studies included in our review. The rapid growth of research in VR/AR is probably due to technological advancements making VR/AR software and equipment (e.g., HMDs) more affordable and widely available (Dechsling et al., 2020; Howard & Gutworth, 2020). These technological advancements offer new possibilities, for example can researchers and clinicians create an indefinite amount of different real-world scenarios VR intervention programs, in many cases also scenarios impossible to incorporate into traditional interventions (e.g., accident simulation, flights etc.; Manca et al., 2013). In regards to autism, an increased awareness of the possibilities combined with an awareness of the acceptability from individuals with autism, hereunder better equipment reducing notions of cybersickness, have contributed to the increased use of VR/AR in autism research. In social skills training in particular, VR/AR represents new possibilities for the development of social skills training programs where clients easily can get extensive and intensive training on social skills in situations and environments that mimics real-life. As pointed out by Dechsling et al. (2021), new VR/AR interventions can be based on existing evidence-based practices, and thus make them more affordable and easier to provide, broader availability at remote locations, and at the same time reduce unwanted geographical variation between clinics and service sites. However, as noted by the informants in Parsons et al. (2020), future research and development should focus on participatory design and to include stakeholders which also communicate without using speech since it is important also to include the opinions of marginalized groups.

Limitations

The main limitations of this review are (1) omitting the grey literature search, and (2) restricting the field on publication year. Excluding grey literature might have biased our sample of included studies because, traditionally, studies with significant and novel results have greater chance to be published (i.e., “file drawer problem”; Rosenthal, 1979). Similarly, we could have excluded some relevant studies that have been published before 2010, which might have weakened the comprehensiveness of this study. Also, we did not conduct a meta-analysis on effects of interventions. However, considering the scarcity of rigorous designs, most notably the low amount of RCTs and lack of comparison groups with individuals with autism (Nordahl-Hansen et al., 2020), conducting a meta-analysis of intervention effects is still premature.

Conclusion

This scoping review reveals that the number of studies using VR/AR in social skills intervention for individuals with autism have continued to increase, but that there are still gaps to be addressed (see Table 2 for a summary of the identified gaps). We have identified work by several authors and research teams, and a heterogeneity in terms of demographics, study aims and methodology. Still, a minority of the studies apply HMDs, but we suggest future studies investigate these tools further as soft- and hardware developments have increased the usability of HMDs.

Table 2.

Identified gaps in the reviewed literature

| Identified gap | Reason | Report | Percentage of studies reporting | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability data | Too few reporting data | 4/5 evaluate as positive | < 50% | Should be reported in every study |

| Diversity of methodology and demographics | ||||

| Female participants | Too few female participants | 7.4% females | > 85% | The gender ratio in the total sample does not reflect the actual male-to-female ratio in autism |

| Studies with participants with ID | Few studies | One study report to have participants with ID | < 55% | May be underreported and underrepresented |

| Age above 30 | Few studies | Six studies with participants above 30 | 100% | Lack of diversity in terms of participants’ age |

| HMD | Few studies | Eight studies applying VR-goggles or AR-/smartglasses | 100% | Considering the reported acceptability and preference towards HMD |

| Diversity of methods | ||||

| RCT and case–control studies | Few studies | Seven RCTs or case–control studies | 100% | Low amount compared to feasibility and case-studies (n = 39) |

| Multiple single-case design | Few studies | Three studies | 100% | Low amount compared to feasibility and case-studies (n = 39) |

The table summarized the identified gaps in the research literature on autism, VR/AR and social skills

It is important to consider the relatively low representation of female participants, and efforts should be made to recruit more gender-balanced samples. Furthermore, researchers and practitioners should strive towards identifying potential gender differences that might influence the effects. There is a need to investigate further the effectiveness of using VR/AR with individuals below ID threshold as they are also underrepresented in this research area as well.

Most studies lack a clear theoretical grounding in evidence-based approaches and we suggest more studies using rigorous designs, and studies including more participants with individuals with autism as controls. More interventions are needed for different age groups, most notably younger children and older adults. As the acceptance and feasibility of using VR/AR are heavily documented, it is time to utilize this technology in established evidence-based practices aiming at enhancing social skills helping individuals with autism maneuver in society. We recommend that future research build on collaborative interdisciplinary efforts including technology and software developers, autism researchers and individuals with autism.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the specialist librarian Grete Gluppe at the Section for Library at Østfold University College for contributing with information retrieval.

Author Contributions

AD: principal author, conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization; SO: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; TK: methodology, writing—review & editing; SS: writing—review & editing, supervision; RAØ: writing—review & editing; FS: writing—review & editing; AN-H (P.I.): conceptualization, methodology, writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Ostfold University College. No funding was received for conducting this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

The asterisk in the reference list indicates the included publications listed in Table 1.

- Amaral C, Mouga S, Simões M, Pereira HC, Bernardino I, Quental H, Playle R, McNamara R, Oliveira G, Castelo-Branco M. A feasibility clinical trial to improve social attention in autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) using a brain computer interface. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2018;12:477. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum RL, Copeland S, Rocca E. Medical scientists and philosophers worldwide appeal to EBM to expand the notion of ‘evidence’. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2020;25:6–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2018-111092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu PRK, Lahiri U. Multiplayer interaction platform with gaze tracking for individuals with autism. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2020;28(11):2443–2450. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2020.3026655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z, Blackwell AF, Coulouris G. Using augmented reality to elicit pretend play for children with autism. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 2015;21(5):598–610. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2014.2385092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach J, Wendt J. Using virtual reality to help students with social interaction skills. Journal of the International Association of Special Education. 2016;16(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini S, Porayska-Pomsta K, Smith TJ. ECHOES: An intelligent serious game for fostering social communication in children with autism. Information Sciences. 2014;264:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2013.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SL, Bresnahan T, Li T, Epnere K, Rizzo A, Partin M, Ahlness RM, Trimmer M. Using virtual interactive training agents (ViTA) with adults with autism and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(3):905–912. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3374-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SL, Li T, Grudzien A, Garcia S. Brief report: Improving employment interview self-efficacy among adults with autism and other developmental disabilities using virtual interactive training agents (ViTA) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;51:741–748. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain B, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E. Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classrooms. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(2):230–242. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Lee IJ, Lin LY. Augmented reality-based self-facial modeling to promote the emotional expression and social skills of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015;36C:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-H, Lee IJ, Lin L-Y. Augmented reality-based video-modeling storybook of nonverbal facial cues for children with autism spectrum disorder to improve their perceptions and judgments of facial expressions and emotions. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55(Part A):477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YF, Chiang HC, Ye J, Cheng LH. Enhancing empathy instruction using a collaborative virtual learning environment for children with autistic spectrum conditions. Computers & Education. 2010;55(4):1449–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Huang C-L, Yang C-S. Using a 3D immersive virtual environment system to enhance social understanding and social skills for children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2015;30(4):222–236. doi: 10.1177/1088357615583473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YF, Huang RW. Using virtual reality environment to improve joint attention associated with pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012;33(6):2141–2152. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YF, Ye J. Exploring the social competence of students with autism spectrum conditions in a collaborative virtual learning environment - The pilot study. Computers & Education. 2010;54(4):1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung PJ, Vanderbilt DL, Soares NS. Social behaviors and active videogame play in children with autism spectrum disorder. Games for Health. 2015;4(3):225–234. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2014.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier R, Speyer R, Chen Y-W, Wilkes-Gillan S, Brown T, Bourke-Taylor H, et al. Evaluating the psychometric quality of social skills measures: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e103299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell C, Mora-Guiard J, Pares N. Structuring collaboration: Multi-user full-body interaction environments for children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2019;58:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2018.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dechsling A, Shic F, Zhang D, Marschik PB, Esposito G, Orm S, Sütterlin S, Kalandadze T, Øien RA, Nordahl-Hansen A. Virtual reality and naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechsling A, Sütterlin S, Nordahl-Hansen A. Acceptability and normative considerations in research on autism spectrum disorders and virtual reality. In: Schmorrow D, Fidopiastis C, editors. Augmented cognition. Human cognition and behavior. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Didehbani N, Allen T, Kandalaft M, Krawczyk D, Chapman S. Virtual reality social cognition training for children with high functioning autism. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;62:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale CM, Eikeseth S, Klintwall L. Children with autism show atypical preference for non-social stimuli. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):10355. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46705-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob CM, Lerman DC, Langlinais CA, Villante NK. Assessing and teaching job-related social skills to adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(1):150–172. doi: 10.1002/jaba.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi O, El-Seoud SA, Alja'am JM, Alpona H, Al-Hemadi M, Al-Hassan D. Design of immersive virtual reality system to improve communication skills in individuals with autism. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning. 2017;12(5):50–64. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v12i05.6766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattier MA, Matson JL, Tureck K, Horovitz M. The effects of gender and age on repetitive and/or restricted behaviors and interests in adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(6):2346–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero JF, Lorenzo G. An immersive virtual reality educational intervention on people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) for the development of communication skills and problem solving. Education and Information Technologies. 2020;25:1689–1722. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-10050-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller RM, Young RL, Weber N. Sex differences in pre-diagnosis concerns for children later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(1):75–84. doi: 10.1177/1362361314568899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz EH, Schoevers RA, Greaves-Lord K, de Bildt A, Hartman CA. Adult manifestation of milder forms of autism spectrum disorder; autistic and non-autistic psychopathology. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020;50(8):2973–2986. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MC, Gutworth MB. A meta-analysis of virtual reality training programs for social skills development. Computers & Education. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ip HH, Wong SW, Chan DF, Byrne J, Li C, Yuan VS, Lau KSY, Wong JY. Enhance emotional and social adaptation skills for children with autism spectrum disorder: A virtual reality enabled approach. Computers & Education. 2018;117:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandalaft MR, Didehbani N, Krawczyk D, Allen T, Chapman S. Virtual reality social cognition training for young adults with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43:34–44. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanfiszer L, Davies F, Collins S. ‘I was just so different’: The experiences of women diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder in adulthood in relation to gender and social relationships. Autism. 2017;21(6):661–669. doi: 10.1177/1362361316687987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F, Im T. Virtual-reality-based social interaction training for children with high-functioning autism. The Journal of Educational Research. 2013;106(6):441–461. doi: 10.1177/0162643420945603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F, Lee S. Virtual reality based collaborative design by children with high-functioning autism: Design-based flexibility, identity, and norm construction. Interactive Learning Environments. 2016;24(7):1511–1533. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2015.1040421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F, Moon J. Virtual collaborative gaming as social skills training for high-functioning autistic children. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2018;49(4):728–741. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F, Moon J, Sokolikj Z. Virtual reality-based social skills training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Special Education Technology. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0162643420945603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F, Whalon K, Yun J. Social skill interventions for youth and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research. 2018;88:3–42. doi: 10.3102/0034654317740334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellmer L, Hedvall Å, Fernell E, Gillberg C, Norrelgen F. Language and communication skills in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders: Contribution of cognition, severity of autism symptoms, and adaptive functioning to the variability. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012;33(1):172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IJ. Kinect-for-windows with augmented reality in an interactive roleplay system for children with an autism spectrum disorder. Interactive Learning Environments. 2020 doi: 10.1080/10494820.2019.1710851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IJ, Chen CH, Wang CP, Chung CH. Augmented reality plus concept map technique to teach children with ASD to use social cues when meeting and greeting. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 2018;27(3):227–243. doi: 10.1007/s40299-018-0382-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Salisbury JP, Vahabzadeh A, Sahin NT. Feasibility of an autism-focused augmented reality smartglasses system for social communication and behavioral coaching. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2017;5:145. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ration in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo G, Gómez-Puerta M, Arráez-Vera G, Lorenzo-Lledó A. Preliminary study of augmented reality as an instrument for improvement of social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Information Technologies. 2019;24(1):181–204. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9768-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo G, Lledó A, Arráez-Vera G, Lorenzo-Lledó A. The application of immersive virtual reality for students with ASD: A review between 1990–2017. Education and Information Technologies. 2018;24:127–151. doi: 10.1007/s10639-018-9766-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo G, Lledó A, Pomares J, Roig R. Design and application of an immersive virtual reality system to enhance emotional skills for children with autism spectrum disorders. Computers & Education. 2016;98:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo G, Pomares J, Lledó A. Inclusion of immersive virtual learning environments and visual control systems to support the learning of students with Asperger syndrome. Computers & Education. 2013;62:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lüddeckens J. Approaches to inclusion and social participation in school for adolescents with autism spectrum conditions (ASC)—A systematic research review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40489-020-00209-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malinverni L, Mora-Guiard J, Padillo V, Valero L, Hervas A, Pares N. An inclusive design approach for developing video games for children with autism spectrum disorder. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;71:535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manca D, Brambilla S, Colombo S. Bridging between virtual reality and accident simulation for training of process-industry operators. Adcances in Engineering Software. 2013;55:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.advengsoft.2012.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maskey M, Lowry J, Rodgers J, McConahie H, Parr JR. Reducing specific phobia/fear in young people with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) through a virtual reality environment intervention. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May T, Cornish K, Rinehart NJ. Gender profiles of behavioral attention in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2016;20(7):627–635. doi: 10.1177/1087054712455502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa-Gresa P, Gil-Gómez H, Lozano-Quilis J, Gil-Gómez J-A. Effectiveness of virtual reality for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: An evidence-based systematic review. Sensors. 2018;18:2486. doi: 10.3390/s18082486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller HL, Bugnariu NL. Level of immersion in virtual environments impacts the ability to assess and teach social skills in autims spectrum disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2016;19:246–256. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Milne, M., Luerssen, M. H., Lewis, T. W., Leibbrandt, R. E., & Powers, D. M. W. (2010). Development of a virtual agent based social tutor for children with autism spectrum disorders. In: Proceedings of the2010 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Barcelona, pp. 1–9, 10.1109/IJCNN.2010.5596584

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J, Ke FF. Exploring the treatment integrity of virtual reality-based social skills training for children with high-functioning autism. Interactive Learning Environments. 2019 doi: 10.1080/10494820.2019.1613665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munkhaugen EK, Gjevik E, Pripp AH, Sponheim E, Diseth TH. School refusal behaviour: Are children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder at a higher risk? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2017;41:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newbutt N, Bradley R, Conley I. Using virtual reality head-mounted displays in schools with autistic children: Views, experiences, and future directions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2020;23(1):23–33. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbutt N, Sung C, Kuo H, Leahy MJ. The potential of virtual reality technologies to support people with an autism condition: A case study of acceptance, presence and negative effects. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine. 2016;14:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Nordahl-Hansen A, Dechsling A, Sütterlin S, Børtveit L, Zhang D, Øien RA, Marschik PB. An overview of virtual reality interventions for two neurodevelopmental disorders: intellectual disabilities and autism. In: Schmorrow D, Fidopiastis C, editors. Augmented cognition. Human cognition and behaviour. HCII 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons S. Learning to work together: Designing a multi-user virtual reality game for social collaboration and perspective-taking for children with autism. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction. 2015;6:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcci.2015.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons S, Yuill N, Good J, Brosnan M. Whose agenda? Who knows best? Whose voice? Co-creating a technology research roadmap with autism stakeholders. Disability & Society. 2020;35(2):201–234. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2019.1624152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramdoss S, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, Mulloy A, Lang R, O'Reilly M. Computer-based interventions to improve social and emotional skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2012;15(2):119–135. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2011.651655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran V, Osgood M, Sazawal V, Solorzano R, Turnacioglu S. Virtual reality support for joint attention using the floreo joint attention module: Usability and feasibility pilot study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. 2019;2(2):e14429. doi: 10.2196/14429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(3):638–641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell G, Mandy W, Elliott D, White R, Pittwood T, Ford T. Selection bias on intellectual ability in autism research: A cross-sectional review and meta-analysis. Molecular Autism. 2019;10:9. doi: 10.1186/s13229-019-0260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewicz A, Schuller B, Marchi E, Piana S, Camurri A, Lassalle A, Baron-Cohen S. An investigation of the 'female camouflage effect' in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism. 2016;7:10. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0073-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbank M, Bottema-Beutel K, Crowley S, Cassidy M, Dunham K, Feldman JI, Crank J, Albarran SA, Raj S, Mahbub P, Woynaroski TG. Project AIM: Autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychological Bulletin. 2020;146(1):1–29. doi: 10.1037/bul0000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, Landa R, Rogers SJ, McGee GG, Kasari C, Ingersoll B, Kaiser AP, Bruinsma Y, McNerney E, Wetherby A, Halladay A. Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45(8):2411–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serret S, Hun S, Iakimova G, Lozada J, Anastassova M, Santos A, Vesperini S, Askenazy F. Facing the challenge of teaching emotions to individuals with low- and high-functioning autism using a new Serious game: A pilot study. Molecular Autism. 2014;5:37. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Hedges LV, Pustejovsky JE. Analysis and meta-analysis of single-case designs with a standardized mean difference statistic: A primer and applications. Journal of School Psychology. 2014;52(2):123–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skafle I, Nordahl-Hansen A, Øien RA. Short report: Social perception of high school students with ASD in Norway. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04281-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Ginger E, Wright K, Wright M, Taylor J, Humm L, Olsen DE, Bell MD, Fleming M. Virtual reality job interview training in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(10):2450–2463. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2113-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stichter J, Laffey J, Galyen K, Herzog M. iSocial: Delivering the social competence intervention for adolescents (SCI-A) in a 3D virtual learning environment for youth with high functioning autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(2):417–430. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland D, Coles C, Southern L. JobTIPS: A transition to employment program for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(10):2472–2483. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1881-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepagnier CY, Olsen DE, Boteler L, Bell AB. Virtual conversation partner for adults with autism. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2011;14(1–2):21–27. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K, Kenny M, Warren R, Wilson C, Stelfox HT, Straus SE. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2016;16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai WT, Lee IJ, Chen CH. Inclusion of third-person perspective in CAVE-like immersive 3D virtual reality role-playing games for social reciprocity training of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Universal Access in the Information Society. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10209-020-00724-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uzuegbunam N, Wong WH, Cheung SCS, Ruble L. MEBook: Multimedia social greetings intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Ieee Transactions on Learning Technologies. 2018;11(4):520–535. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2017.2772255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vahabzadeh A, Keshav NU, Abdus-Sabur R, Huey K, Liu R, Sahin NT. Improved socio-emotional and behavioral functioning in students with autism following school-based smartglasses intervention: Multi-stage feasibility and controlled efficacy study. Behavioral Sciences. 2018;8(10):85. doi: 10.3390/bs8100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Laffey J, Xing W, Galyen K, Stichter J. Fostering verbal and non-verbal social interactions in a 3D collaborative virtual learning environment: A case study of youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders learning social competence in iSocial. Educational Technology Research and Development. 2017;65(4):1015–1039. doi: 10.1007/s11423-017-9512-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DM, Esposito MCK. Virtual reality in transition program for adults with autism: Self-efficacy, confidence, and interview skills. Contemporary School Psychology. 2019;23(4):423–431. doi: 10.1007/s40688-018-0195-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *White, S. W., Richey, J. A., Gracanin, D., Coffman, M., Elias, R., LaConte, S., & Ollendick, T. H. (2016). Psychosocial and computer-assisted intervention for college students with autism spectrum disorder: Preliminary support for feasibility. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 307–317. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc5241080/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wolstencroft J, Robinson L, Srinivasan R, Kerry E, Mandy W, Skuse D. A systematic review of group social skills interventions, and meta-analysis of outcomes, for children with high functioning ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(7):2293–2307. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3485-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YJD, Allen T, Abdullahi SM, Pelphrey KA, Volkmar FR, Chapman SB. Brain responses to biological motion predict treatment outcome in young adults with autism receiving Virtual Reality Social Cognition Training: Preliminary findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2017;93:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YJD, Allen T, Abdullahi SM, Pelphrey KA, Volkmar FR, Chapman SB. Neural mechanisms of behavioral change in young adults with high-functioning autism receiving virtual reality social cognition training: A pilot study. Autism Research. 2018;11(5):713–725. doi: 10.1002/aur.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Fu Q, Swanson A, Weitlauf A, Warren Z, Sarkar N. Design and evaluation of a collaborative virtual environment (CoMove) for autism spectrum disorder intervention. ACM Transactions on Accessible Computing. 2018;11(2):1–22. doi: 10.1145/3209687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Warren Z, Swanson A, Weitlauf A, Sarkar N. Understanding performance and verbal-communication of children with ASD in a collaborative virtual environment. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(8):2779–2789. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Swanson AR, Weitlauf AS, Warren ZE, Sarkar N. Hand-in-hand: A communication-enhancement collaborative virtual reality system for promoting social interaction in children with autism spectrum disorders. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems. 2018;48(2):136–148. doi: 10.1109/THMS.2018.2791562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.