Abstract

Archaeal flagella are unique motility structures, and the absence of bacterial structural motility genes in the complete genome sequences of flagellated archaeal species suggests that archaeal flagellar biogenesis is likely mediated by novel components. In this study, a conserved flagellar gene family from each of Methanococcus voltae, Methanococcus maripaludis, Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus, and Methanococcus jannaschii has been characterized. These species possess multiple flagellin genes followed immediately by eight known and supposed flagellar accessory genes, flaCDEFGHIJ. Sequence analyses identified a conserved Walker box A motif in the putative nucleotide binding proteins FlaH and FlaI that may be involved in energy production for flagellin secretion or assembly. Northern blotting studies demonstrated that all the species have abundant polycistronic mRNAs corresponding to some of the structural flagellin genes, and in some cases several flagellar accessory genes were shown to be cotranscribed with the flagellin genes. Cloned flagellar accessory genes of M. voltae were successfully overexpressed as His-tagged proteins in Escherichia coli. These recombinant flagellar accessory proteins were affinity purified and used as antigens to raise polyclonal antibodies for localization studies. Immunoblotting of fractionated M. voltae cells demonstrated that FlaC, FlaD, FlaE, FlaH, and FlaI are all present in the cell as membrane-associated proteins but are not major components of isolated flagellar filaments. Interestingly, flaD was found to encode two proteins, each translated from a separate ribosome binding site. These protein expression data indicate for the first time that the putative flagellar accessory genes of M. voltae, and likely those of other archaeal species, do encode proteins that can be detected in the cell.

The Archaea represent a unique group of organisms that have features in common with both the Bacteria and the Eucarya while also possessing numerous traits that appear to be specific to the archaeal lineage (22, 40). Interestingly, it appears that gene products unique to the Archaea are responsible for the structure and assembly of the flagellar filament. Indeed, no homologues of genes for bacterial flagellar structure and assembly have been found in archaeal genomes (13).

Archaeal flagellins are initially made as preproteins that are processed prior to assembly into the flagellar filament (10, 45). It has been demonstrated for some methanogens that leader peptides are cleaved from preflagellins upon export (2, 14, 24). This is likely true of all archaeal flagellins, based on sequence alignments (45). In addition, many archaeal species have flagellins that are glycosylated (5, 12, 33), although the exact biological significance of this posttranslational modification is not known. The gene products responsible for these specific posttranslational events have not been identified.

To date, two gene families that are involved in archaeal flagellar biosynthesis and function have been identified. A set of bacterial-gene-like chemotaxis genes, including those encoding CheA, CheW, and CheY, has been identified in Archaeoglobus fulgidus and Halobacterium salinarum (29, 42). In addition, a gene family encoding at least some structural features of the flagellum, as well as other products required for flagellation, has been identified (3, 24, 47). The composition and order of the genes in this gene family can vary among archaea (45). Mutations of this gene family indicate that it is a motility gene locus (45, 47). Within the gene family, there are generally multiple flagellin genes that are immediately followed by a number of downstream genes of unknown function. Although the multiple flagellin genes within a particular family share considerable sequence similarity, mutant studies with Methanococcus voltae and H. salinarum suggest that the proteins encoded by the multiple flagellin genes are not simply interchangeable and likely have specific roles within the filament (23, 44). This is supported by the fact that archaeal flagellar filaments tend to be composed of a mixture of different flagellins, present in varying amounts (2, 16).

Transcriptional studies on the motility locus mentioned above have been reported for some archaea. In M. voltae, two transcriptional units have been identified (24). One unit contains flaA, a single flagellin gene that is weakly transcribed. An adjacent unit encodes three flagellin genes (flaB1, flaB2, and flaB3) along with a number of immediate downstream genes. In H. salinarum, two transcriptional units encoding a total of five flagellin genes have been identified (17). One unit (the A locus) contains two flagellin genes, while the other (the B locus) contains three. The two loci are not physically linked on the chromosome, although all of the flagellin genes are expressed and all the flagellins are found in H. salinarum flagellar filaments (16). The flagellar accessory genes of this halophile are not transcribed with any of the flagellin genes (17). Lastly, the flagellin genes and a number of downstream open reading frames (ORFs) appear to be transcribed from a single promoter in Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1 (36).

The majority of the conserved genes immediately downstream of archaeal flagellins appear to be unique to archaeal species. Moreover, no biochemical functions have been experimentally determined for any of these genes. One protein, called FlaI, is homologous to PilT (3), a protein involved in type II secretion and type IV pilus-mediated twitching motility in bacteria (50, 52). The presence of a type II secretion homologue, along with the amino-terminal sequence similarity of archaeal flagellins and type IV pilins (14), suggests that archaeal flagella may be assembled via a mechanism similar to that for type IV pili (45).

Within the genus Methanococcus, a rare situation is found: species grow at very different temperature optima. Specifically, this genus contains closely related mesophiles, thermophiles, and hyperthermophiles. To further the understanding of archaeal flagellation, the flagellar gene families and flagella of selected methanogenic archaea were isolated and studied with respect to gene composition, expression, and filament thermostability. This study presents novel protein expression and localization data on specific conserved proteins that at present have no specific known functions but are known to be involved in flagellar biogenesis in the mesophilic methanogen M. voltae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial strains and growth conditions.

M. voltae (obtained from G. D. Sprott, National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and Methanococcus maripaludis (obtained from W. B. Whitman, University of Georgia, Athens, Ga.) were grown in Balch medium 3 at 37°C as previously described (26), while Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus (obtained from R. M. Sparling, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) was grown in 10 ml of Balch medium 3 in serum bottles at 60°C. Methanococcus jannaschii (obtained from G. D. Sprott) and Methanococcus igneus (DSM 5666) cultures were grown as previously described (15) in modified 1-liter bottles at 80°C. Escherichia coli DH5α was used for all in vitro cloning and was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. E. coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS were used as expression strains. Antibiotics were added for selection of plasmids when needed. Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| M. voltae | Wild type | G. D. Sprott |

| M. maripaludis | Wild type | W. B. Whitman |

| M. thermolithotrophicus | Wild type | R. M. Sparling |

| M. jannaschii | Wild type | G. D. Sprott |

| M. igneus DSM 5666 | Wild type | Deutsche Sammulung von Mikroorganismen |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Laboratory K-12 strain for in vitro cloning | |

| BL21(DE3) | Expression host for T7 promoter-based plasmids | Novagen |

| BL21(DE3)/pLysS | Expression host for T7 promoter-based plasmids with pLysS for tight repression | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKJ60 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 3.3-kb PstI flaC-flaF M. voltae fragment | |

| pKJ184 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 0.7-kb EcoRI flaB1 M. maripaludis fragment | This study |

| pKJ188 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 0.6-kb EcoRI flaB3 M. thermolithotrophicus fragment | This study |

| pKJ191 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 1.8-kb EcoRI flaB2-flaC M. maripaludis fragment | This study |

| pKJ228 | pUC21 derivative carrying a 1.2-kb PstI flaB2 M. thermolithotrophicus fragment | This study |

| pKJ229 | pUC21 derivative carrying a 0.8-kb PstI flaB1 M. thermolithotrophicus fragment | This study |

| pKJ262 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 1.2-kb EcoRI flaC-flaE M. maripaludis fragment | This study |

| pKJ263 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 3.8-kb PvuII M. thermolithotrophicus fragment corresponding to sequence upstream of flaB1; cloned into the SmaI site of the plasmid polylinker | This study |

| pKJ267 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 2.1-kb inverse-PCR product amplified from M. maripaludis genomic DNA; cloned into the SmaI site of the plasmid polylinker | This study |

| pKJ307 | pUC21 derivative carrying a 4.0-kb SmaI/HindIII flaF-flaJ M. maripaludis fragment | This study |

| pKJ312 | pUC21 derivative carrying a 6.7-kb NcoI flaB3-flaJ M. thermolithotrophicus fragment | This study |

| pKJ315 | pUC18 derivative carrying a 0.9-kb inverse-PCR product amplified from M. thermolithotrophicus genomic DNA into the SmaI site of the plasmid polylinker | This study |

| pET23a+ | Expression vector with T7 promoter and sequence for a C-terminal polyhistidine tag on the target protein | Novagen |

| pKJ194 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaEMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pKJ198 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaDMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pKJ199 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaCMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pKJ200 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaHMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pKJ210 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaFMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pKJ266 | pET23a+ derivative carrying flaIMv PCR amplified without a stop codon as an NdeI/XhoI fragment | This study |

| pSJS1240 | pACYC184 derivative containing ileX (encoding tRNAAUA) and argU (encoding tRNAAGA/AGG) | S. Sandler |

DNA manipulations.

Flagellin genes from various methanococci were initially identified by Southern hybridization experiments. A short DNA fragment complementary to the first 135 bp of flaB1 of M. voltae was labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) and used as a probe against restriction enzyme digests of chromosomal DNA (isolated as previously described [18]) from different species of methanococci. Restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA fragments approximately the sizes of those identified by Southern hybridization were gel extracted and purified using a PREP-A-GENE matrix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) and then cloned into the pUC18 or pUC21 vector digested with the appropriate enzyme to generate size-selected libraries.

In M. maripaludis, all three flagellin genes are located on two linked EcoRI fragments that were isolated from an M. maripaludis size-selected EcoRI library. An EcoRI fragment of approximately 1.2 kb linked to the flagellin genes was identified by Southern hybridization with an M. voltae flaC gene probe. An inverse-PCR strategy was employed to obtain downstream sequence using DNA digested with EcoRV and ligated under low DNA concentrations to promote monomeric, intramolecular ligation (9). An aliquot of the ligation reaction product was used as a template in a PCR with the divergent primers 5′-ATACTTATCAGAAAGAGTGG and 5′-AATGCATCTTCTGGAACAGC. The resulting 2.1-kb product was cloned into SmaI Ready to Go/BAP pUC18 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie D'Urfe, Quebec, Canada). The inverse-PCR product was then DIG labeled and used as a probe in Southern blotting to identify a final overlapping DNA fragment that was cloned into pUC21 as a 4.7-kb SmaI/HindIII fragment to complete the flagellar gene family.

For M. thermolithotrophicus, a 0.6-kb EcoRI flagellin gene fragment identified by Southern hybridization was cloned and isolated from a pUC18/EcoRI library. In addition, Southern hybridization identified two PstI flagellin gene fragments of 0.8 and 1.2 kb that were cloned and isolated from a pUC21/PstI genomic library. It was hypothesized that the flagellin genes were located close together, so a PCR-based strategy was used to link the fragments. Two divergent primers located on different DNA strands were designed from each isolated flagellin gene fragment and were used in a PCR with genomic DNA to close the gaps between the fragments and to determine the physical arrangement of the genes on the chromosome. Primers 5′-AATGGAACTACAGTATGG and 5′-AATGCAGATGGTGCATC gave a PCR product of 778 bp, while primers 5′-AAGGTAACAGTATTATCC and 5′-CTGATTCAAATACTGATCC gave a PCR product of 865 bp. These PCR products linked the previously identified flagellin gene fragments. Southern hybridization using the 0.6-kb EcoRI flagellin gene fragment as a probe resulted in the identification and cloning of an overlapping 6-kb NcoI fragment containing a fourth flagellin gene and additional flagellar accessory genes. An inverse-PCR strategy was used to obtain a final DNA fragment for the complete M. thermolithotrophicus flagellar gene family. This involved DraI-digested DNA ligated as described above and used as a template in PCR with the divergent primers 5′-CGCTTCATACGGAGTCGC and 5′-GGATTCAGTCATACCTCC. A 0.9-kb PCR product was amplified and then cloned as a blunt-end DNA fragment into SmaI/BAP Ready to Go pUC18.

RNA isolation.

Total cellular RNA was isolated using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) with minor modifications as previously described (47).

Southern and Northern hybridizations.

Southern and Northern hybridizations were performed as previously described (47). Probes were generated by using a DIG-Labeling Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Specific DNA fragments were gel purified and then random prime labeled according to the manufacturer's directions. Alternatively, DIG-labeled dUTP was directly incorporated into probes using PCR, followed by purification of the PCR products with a Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen).

Construction of flagellar accessory protein overexpression clones.

M. voltae flagellar accessory genes flaC, flaD, flaE, and flaF (GenBank accession number U97040) were PCR amplified using pKJ60, which contains a 3.3-kb PstI M. voltae genomic fragment, as a template. For flaI and flaJ, genomic DNA served as a template in the PCR amplification. For each gene, primers introduced an NdeI site at the 5′ end of the gene and an XhoI site at the 3′ end. Each PCR product was cloned into the corresponding restriction sites in the pET23a+ plasmid (Novagen, Inc., Madison, Wis.). The genes were amplified without their respective stop codons to create an in-frame fusion with the sequence coding for the six-histidine tag upon ligation in the pET23a+ plasmid. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Overexpression and purification of His-tagged flagellar accessory proteins.

T7 RNA polymerase-directed expression (43) of the cloned flagellar accessory genes was performed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Plasmids pKJ199 and pKJ194 were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and plated onto LB agar plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml. Similarly, plasmids pKJ198, pKJ200, and pKJ210 were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells and plated onto LB agar plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and 30 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. For plasmid pKJ266, E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pSJS1240 was used as the expression host. pSJS1240 is a pACYC derivative (compatible with pET23a+) carrying the argU and ileX genes encoding tRNAs (tRNAAGA/AGG and tRNAAUA) (28). The latter transformants were plated onto plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml. Cell cultures, induced for 2 to 4 h with 0.4 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Life Technologies), were harvested at 5,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting cell pellets were frozen overnight at −20°C. Overexpression of recombinant FlaD in E. coli was problematic but eventually was achieved with meticulous attention to plasmid stability. It was not possible to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) with pKJ198. The construct, however, could be transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS, although a small- and a large-colony type were observed. Analysis of late-log-phase cultures initially inoculated with the small-colony type revealed that most of the cells produced large colonies when grown on LB agar plates. Amelioration of an induction procedure for recombinant FlaD expression demonstrated that the small-colony type possessed the ability to express the target protein, whereas the large-colony type did not produce an induction product.

All of the overexpressed target proteins were purified under denaturing conditions with the exception of FlaF and FlaH (see below). Nickel affinity purification was carried out by using a His-bind kit (Novagen) under denaturing conditions, as directed by the manufacturer. The purified proteins were then concentrated and desalted (using sterile distilled water) to a volume of approximately 2 ml using spin filters (Centricon YM-10 or YM-30 [Millipore, Bedford, Mass.], depending on the protein being isolated). Protein concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically by the Bradford binding assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Depending on the flagellar accessory gene expressed in E. coli, approximately 2 to 4 mg of target protein was obtained using this protocol. In the case of FlaF overexpression, most of the protein was located in inclusion bodies that were difficult to solubilize and could not be used for affinity chromatography. For FlaH, the soluble fraction of the cell culture lysate was used in a nondenaturing purification procedure using the His-bind kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Production of polyclonal antibodies to flagellar accessory proteins.

Polyclonal antibodies against purified histidine-tagged M. voltae proteins FlaC, FlaD, FlaE, FlaH, and FlaI were raised in chickens and isolated from eggs. Antibodies were produced by RCH Antibodies, Sydenham, Ontario, Canada.

Immunoblotting.

Membrane and cytoplasmic fractions of M. voltae (4) and flagellar preparations (see below) were subjected to SDS-PAGE as described by Laemmli (32) and then transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membranes (Millipore) as previously described (48). Primary antibodies were diluted to working concentrations. The secondary antibody was a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken immunoglobulin Y (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) used at a 1:50,000 dilution. For immunodetection of overexpressed His-tagged proteins, approximately 1 μg (total protein) was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. Penta-His antibodies (0.2 mg/ml) (Qiagen) were used at a 1:2,000 dilution. The secondary antibody was a peroxidase-linked sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) used at a 1:10,000 dilution. Blots were developed using a chemiluminescent detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's directions.

N-terminal sequencing.

Samples for N-terminal sequencing were prepared and analyzed as previously described (4).

Isolation of flagellar filaments.

Crude preparations of flagellar filaments were isolated by shearing, using a previously described protocol (26). For the isolation of flagella containing some attached basal structure, six liters of cells was pelleted by centrifugation at 5,900 × g for 15 min. The pellet was resuspended in 40 ml of suspension buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.0], 2% [wt/vol] NaCl, 0.28% [wt/vol] MgCl2, 0.35% [wt/vol] MgSO4) and treated with DNase and RNase (Life Technologies). OP-10 detergent (a gift from S.-I. Aizawa) was added to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol), and the suspension was incubated at room temperature for 30 min with occasional inverting. After centrifugation at 5,900 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was collected and then mixed with 1 ml of precipitation buffer (1 M NaCl, 20% [wt/vol] polyethylene glycol 8000) (53), followed by incubation on ice for 1 h with gentle shaking. The mixture was then centrifuged at 7,800 × g for 10 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) prior to being loaded onto a KBr gradient, as previously described (21).

Thermostability of flagellar filaments and electron microscopy.

Crude flagellar filament preparations (50-μl aliquots in Eppendorf microtubes) were incubated at 90, 80, 70, 60, 50, or 40°C for 30 min. After incubation, the flagellar filament preparations were absorbed onto copper grids and negatively stained with 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate for 2 min. Grids were viewed on a Hitachi H-7000 electron microscope operating at 75 kV.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the M. maripaludis and M. thermolithotrophicus flagellar gene families have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF333233 and AF333250, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of methanogen flagellin genes.

Previous studies have identified a motility gene locus in M. voltae (23). In addition, flagellar gene families have been identified by complete genome sequencing of other archaeal species. Initial evaluation of these gene families suggested that the content and number of genes within this motility locus are variable. To obtain a better understanding of methanogen flagellar genetics, the flagellar gene families of closely related methanococci that grow at very different temperature optima were characterized.

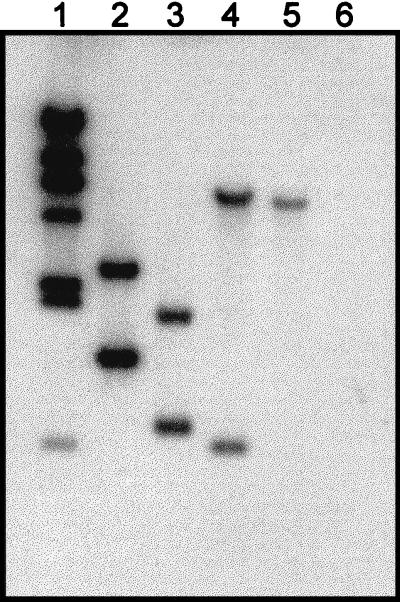

Initially, methanogen flagellin gene fragments were identified using a short DNA probe corresponding to the 5′ end of flaB1 of M. voltae. Chromosomal DNA restriction enzyme digests of M. maripaludis, M. thermolithotrophicus, and M. jannaschii gave strong hybridization signals in Southern blots (Fig. 1), consistent with the known conservation of the 5′ ends of methanogen flagellin genes (25). The presence of more than one signal (depending on the restriction digest) indicated the presence of multiple flagellin genes in the genome. Surprisingly, no hybridization signals were obtained for the hyperthermophile M. igneus, although it is believed that all members of the Methanococcales are flagellated (51). However, it is unclear whether a few filamentous structures observed on the surface of M. igneus are, in fact, flagella (7). Using various libraries, overlapping DNA fragments were isolated, completing the identification of the flagellin genes for each methanogen.

FIG. 1.

Identification of methanococcal flagellin gene fragments by Southern hybridization. EcoRI restriction enzyme-digested chromosomal DNAs from various methanococci were probed with a DIG-labeled DNA fragment corresponding to the first 135 bp of M voltae flaB1. Lane 1, DIG-labeled λ HindIII molecular size standards; lane 2, M. voltae DNA; lane 3, M. maripaludis DNA; lane 4, M. thermolithotrophicus DNA; lane 5, M. jannaschii DNA; lane 6, M. igneus DNA.

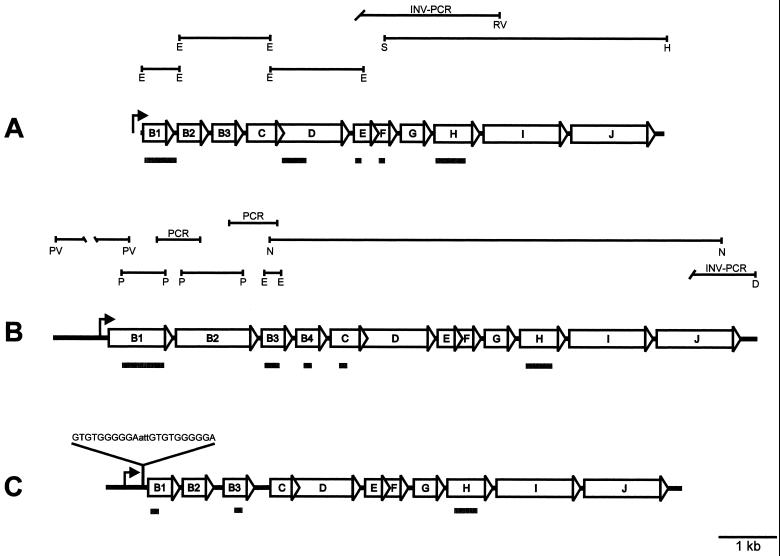

For M. maripaludis, three linked flagellin genes with short intergenic regions (35 and 37 bp) were identified on two EcoRI restriction fragments (Fig. 2). The flagellin genes, arranged in tandem, are each about 650 bp in length, a size similar to those of flagellin genes of other mesophilic methanococci (2, 24), and each one is preceded by a nucleotide sequence resembling a methanogen ribosome binding site (41).

FIG. 2.

Maps of flagellar gene families of M. maripaludis (A), M. thermolithotrophicus (B), and M. jannaschii (C). The M. jannaschii flagellar gene family sequence and its annotation have been determined previously by complete genome sequencing (6). Gene designations are given in the corresponding open arrows. Each arrow points in the direction of transcription. Bent arrows indicate putative promoters of the respective gene families. Lines above the genetic maps represent cloned restriction fragments that were used to obtain sequence data. Restriction site designations: D, DraI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NcoI; P, PstI; PV, PvuII; RV, EcoRV; S, SmaI. Intergenic PCR (denoted by “PCR”) and inverse PCR (INV-PCR) were used to close gaps and to obtain flanking sequences, respectively. Probes used in Northern blotting experiments are shown as shaded rectangles below the respective flagellar gene families. The sequence of a 10-base direct repeat between the putative upstream promoter and the translational start site of flaB1 from M. jannaschii is shown.

For M. thermolithotrophicus, four flagellin genes of different sizes, arranged in tandem, were identified (Fig. 2). Each gene has its own putative ribosome binding site. Unexpectedly, M. thermolithotrophicus flaB1 and flaB2 (flaB1Mt and flaB2Mt) are 986 and 1,305 bp, respectively, much longer than other methanogen flagellin genes. The remaining two flagellin genes are similar in size to those of other methanococci (at 650 bp). The long flagellin genes (flaB1Mt and flaB2Mt) share high sequence identity; however, flaB2Mt appears to encode an internal 220-amino-acid (220-aa) sequence that is unique to this flagellin. A previous study reported three major proteins of 62, 44, and 26 kDa in M. thermolithotrophicus flagellar filaments (30). Our analysis of KBr gradient-purified M. thermolithotrophicus flagellar filaments resulted in the identification of proteins with apparent molecular masses of 62, 44, 37, and 26 kDa by SDS-PAGE (data not shown), while the flagellin genes are predicted to encode proteins with molecular masses of 46.2, 34.9, 22.9, and 22.7 kDa. Glycosylation does not appear to account for the apparent discrepancy in molecular masses, since none of these flagellins stained as glycoproteins with the periodic acid-Schiff stain (data not shown).

From the complete genome sequence of M. jannaschii (6), three adjacent flagellin genes of approximately 650 bp each were identified (Fig. 2). The intergenic regions are larger (85 and 102 bp) than those seen in the other methanococci. Interestingly, 183 nucleotides downstream from a putative promoter and 49 nucleotides upstream from the presumed translational start site for the first flagellin gene, there is a 10-base direct-repeat sequence (capital letters) separated by three bases (lowercase letters), GTGTGGGGGAattGTGTGGGGGA, that may serve as an element for regulating flagellar gene family expression.

Identification of preflagellin leader sequences.

Short leader sequences have been determined for some methanococcal flagellins (2, 14, 24). All of the methanogen flagellins identified in this study are predicted to possess leader sequences similar to those reported for other methanococci. Each leader sequence has an overall net positive charge, an invariant glycine at position −1 (relative to the predicted cleavage site), and a positively charged amino acid at position −2 (either arginine or lysine).

Identification and characterization of methanogen flagellar accessory genes.

Immediately downstream of the flagellin genes in each methanogen there are 8 ORFs that are homologous to flaC, flaD, flaE, flaF, flaG, flaH, flaI, and flaJ of M. voltae (3) (Fig. 2). A summary of identifiable properties of the respective gene products is presented in Table 2. The genes in the cluster are arranged contiguously, either overlapping or separated by short intergenic regions. Larger regions (40 to 60 nucleotides) generally separate the flaF and flaG homologues. Alignment of the various methanococcal flaD genes suggested that the sequence of M. voltae flaD (flaDMv) as deposited in GenBank (1,026 bp; accession number U97040) did not represent the entire gene due to a sequencing error. This was confirmed by resequencing. The correct flaDMv sequence is 1,089 bp, with the new sequence extending the 5′ end of the gene by 63 nucleotides. This new sequence overlaps with the 3′ end of flaCMv, as found in the other methanococci.

TABLE 2.

Properties of the gene products encoded by methanococcal flagellar gene families

| Gene product | Characteristics | Subcellular locationa |

|---|---|---|

| FlaB1/FlaB2b | Highly conserved, mainly hydrophobic N-terminal region with sequence similarity to type IV pilins; synthesized as preproteins with a leader peptide that is removed by a preflagellin peptidase before assembly into flagellar filaments | Flagellar filament |

| FlaC | High charged-amino-acid content (34%) | Membrane |

| FlaD | Putative polyproteinc with C-terminal region exhibiting sequence similarity to FlaE | Membrane |

| FlaE | Sequence similarity to the C-terminal region and short version of FlaD | Membrane |

| FlaF | Limited to methanococcal flagellar gene familiesd; N-terminal hydrophobic region with hydropathy profile similar to that of flagellins | Not determined |

| FlaG | N-terminal hydrophobic region with weak sequence similarity to flagellins | Not determined |

| FlaH | Walker box A motif, putative nucleotide binding protein; found in all flagellated archaea where sequence data are available | Membrane |

| FlaI | Bacterial type II secretion homologue with sequence similarity to PilB/PilT and other supposed type II secretion archaeal homologues; Walker box A motif, putative nucleotide-binding protein; found in all flagellated archaea where sequence data are available | Membrane |

| FlaJ | Presumed integral membrane protein with 7 to 9 predicted transmembrane domains; found in all flagellated archaea where sequence data are available | Not determined |

Determined by immunoblot analyses of M. voltae cell fractions and purified flagellar filaments.

The major flagellins found in Methanococcus sp. flagellar filaments are listed, although other flagellins possess the same features and are likely present as minor components of flagella.

As demonstrated by overexpression studies with M. voltae and suggested by the presence of a second ribosome binding site within the ORF.

Not present in flagellar gene families outside of Methanococcus spp. that are currently available in public databases.

Biochemical functions have yet to be determined for any of the respective gene products, although mutant studies with M. voltae have demonstrated that flaH, flaI, and flaJ are involved in flagellar biogenesis (47; also unpublished data). It has been reported that FlaI is homologous to PilB and PilT (3), two proteins involved in type II secretion and type IV pilus biogenesis in gram-negative bacteria (38, 39, 50). These putative nucleotide binding proteins have a Walker box A motif (49). Furthermore, FlaH (from each methanogen) has a putative Walker box A motif at the N-terminal region of the protein. Interestingly, sequence alignments of the FlaD and FlaE homologues from each methanogen reveal that the ∼135 C-terminal-most amino acids of FlaD (entire length, ∼360 aa) share approximately 65% sequence similarity with the entire FlaE protein (∼135 aa). No flaF homologues have been found in other flagellated archaeal species, suggesting that the gene might be specific to methanogens. FlaF and FlaG are two proteins with hydrophobic N-terminal regions, while FlaI is predicted to possess a hydrophobic C-terminal domain. FlaJ is predicted by dense alignment surface analysis to be an integral membrane protein with 7 to 9 transmembrane domains (11).

Transcriptional analysis of flagellar gene families.

The transcriptional profiles of the flagellar gene families of the three methanogens were determined by Northern blotting.

The 0.7-kb EcoRI fragment containing flaB1 of M. maripaludis (flaB1Mm) was DIG labeled and used as a probe. This probe produced three signals of different intensities corresponding to three mRNA species of approximately 1.3, 2.0, and 4.0 kb (Fig. 3A). Although no data are available for sequences upstream of flaB1Mm, presumably all the messages detected are expressed from a promoter upstream of this gene, as is the case for M. voltae. Furthermore, no nucleotide sequences resembling the methanogenic archaeal consensus box A promoter sequence [TTTA(T/A)ATA] (41) are evident 5′ to any of the downstream genes. The 1.3-kb message therefore likely encodes the first two flagellin genes, flaB1Mm and flaB2Mm. Moreover, a poly(T) stretch immediately after flaB2 may serve as a terminator, reducing transcription levels of downstream genes (24, 41). Transcriptional read-through presumably produces the 2.0-kb message, which would include all three flagellin genes. Additional read-through likely produces the 4-kb mRNA species. A flaDMm probe detected only a 4-kb mRNA species (Fig. 3A), whereas a flaEMm probe did not detect any mRNAs. Thus, the 4-kb message likely extends from flaB1Mm to flaDMm.

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analyses of methanococcal flagellar gene families. The DIG-labeled DNA probe used is given above each blot. (A) M. maripaludis RNA; (B) M. thermolithotrophicus RNA; (C) M. jannaschii RNA.

For M. thermolithotrophicus, only two mRNA species pertaining to the flagellar gene family could be detected. A nucleotide sequence with similarity to the methanogen consensus promoter sequence is located 94 bp upstream of flaB1Mt. A 0.8-kb PstI fragment corresponding to flaB1Mt was used as a probe and detected a transcript of approximately 3 kb (Fig. 3B). If this message originates upstream of flaB1Mt, the transcript would include flaB1Mt, flaB2Mt, and flaB3Mt. Analysis of the intergenic region between flaB3Mt and flaB4Mt revealed the presence of a short poly(T) stretch that may act as a terminator. Interestingly, a probe corresponding to flaB3Mt detected two mRNA species of 3 and 0.6 kb (Fig. 3B). To determine whether the 0.6-kb mRNA species corresponded to flaB3Mt or to flaB4Mt, which is immediately downstream, an internal and unique sequence for flaB4Mt was generated by PCR and used as a probe. No mRNA species were detected using this probe, indicating that the 0.6-kb message does not correspond to flaB4Mt. One possible explanation for the 0.6-kb mRNA species is mRNA processing, a feature that has been reported for some polycistronic mRNAs in methanogens (1, 27, 34). mRNA processing may generate the stable 0.6-kb message carrying flaB3Mt from the larger 3-kb mRNA, since no obvious methanogen promoter sequences are present in the intergenic region between flaB2Mt and flaB3Mt. Although no mRNAs could be detected for the downstream genes, presumably they are transcribed, but at low levels that are not readily detectable. Since no promoter sequences are apparent 5′ to any of the accessory genes, transcription may be driven by the promoter upstream of flaB1Mt and followed by read-through of putative terminator elements immediately after flaB3Mt, resulting in limited expression of flaB4Mt and downstream accessory genes. Presumably, the genes transcribed at lower levels encode products needed in smaller amounts than the major structural flagellins.

For the hyperthermophile M. jannaschii, a ∼1.5-kb RNA species was detected by use of a probe for M. jannaschii flaB1 (flaB1Mj) (Fig. 3C). A nucleotide sequence exactly matching the consensus box A methanogen promoter sequence (TTTATATA) was found 255 bp upstream of the putative translational start site of flaB1Mj. This 1.5-kb message likely includes flaB1Mj and flaB2Mj. As with M. maripaludis, a poly(T) sequence is located immediately after flaB2Mj. Although a flaB3Mj-specific probe did not detect any mRNAs, a sequence close to the methanogen consensus promoter sequence can be identified 5′ to flaB3Mj (ATTATATA); this sequence may serve to drive transcription of this last flagellin gene and the downstream genes. However, this may be a fortuitous result due to the high AT content of intergenic regions common to methanogens (41).

Overexpression of recombinant flagellar accessory proteins in E. coli

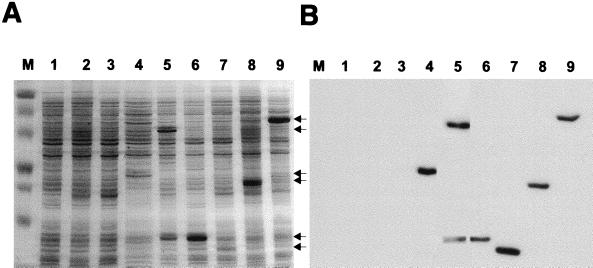

Since much structural information pertaining to flagella has been amassed for M. voltae (26, 31) and mutants with changes in some of its flagellar accessory genes have previously been isolated, the flagellar accessory gene products from this methanogen were overexpressed in E. coli. In this study, six of the eight flagellar accessory genes of M. voltae were successfully overexpressed as His-tagged proteins. The characteristics of each of the expression clones are described below.

Successful overexpression of recombinant FlaC, FlaD, FlaE, FlaF, FlaH, and FlaI was achieved in E. coli (Fig. 4A). In most cases, the apparent molecular weights of the recombinant proteins are higher than the predicted molecular weights (Table 3). Interestingly, upon IPTG induction (for FlaD expression) of E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS harboring pKJ198, two stable products with apparent molecular masses of approximately 49 and 16 kDa were produced (Fig. 4A, lane 5). The flaD ORF that was cloned is predicted to encode a protein with a molecular mass of 39.5 kDa. Purification of the induction products revealed that the 16-kDa species is a C-terminal His-tagged polypeptide of FlaD. Furthermore, immunoblotting with an anti-His antibody revealed that both polypeptides were produced with the polyhistidine tag (Fig. 4B, lane 5), and similar amounts of the two induction products were obtained after nickel affinity chromatography (data not shown). N-terminal sequencing of the 16-kDa induction product revealed the amino acid sequence (MESEIAKINE) that corresponds to amino acid positions 232 to 242 in the FlaD sequence. A sequence with similarity to a methanogen ribosome binding site is located 7 bp upstream of the initiating methionine of the 16-kDa induction product. Indeed, translation from this putative ribosome binding site in E. coli would produce a 131-aa polypeptide with a predicted molecular mass of 15.5 kDa. These data suggest that the 49-kDa protein represents the entire protein, whereas the 16-kDa polypeptide is an induction product that is translated from a second in-frame putative distal start site.

FIG. 4.

Detection of overexpressed His-tagged M. voltae flagellar accessory proteins FlaC, FlaD, FlaE, FlaF, FlaH, and FlaI derived from a T7 expression system. E. coli cultures harboring the respective flagellar accessory gene cloned into pET23a+ were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 and then induced with 0.4 mM IPTG. Background vector controls were included in the analyses. Two hours postinduction, bacterial lysates (20 μg of total protein per lane) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gel) and the proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Arrows point to the gene-specific expressed proteins. (A) Lane M, molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons); lane 1, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pET23a+; lane 2, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pET23a+; lane 3, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pKJ265/pET23a+; lane 4, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pKJ199 (FlaC); lane 5, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pKJ198 (FlaD); lane 6, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pKJ194 (FlaE); lane 7, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pKJ210 (FlaF); lane 8, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS/pKJ200 (FlaH); lane 9, E. coli BL21(DE3)/pKJ265/pKJ266 (FlaI). (B) Immunoblot, developed with an anti-His monoclonal antibody, of a gel similar to that shown in panel A but containing 1/10 the amount of protein per lane.

TABLE 3.

Summary of M. voltae flagellar accessory protein characteristics

| Protein | Size (aa) | Predicted pI | Molecular mass (kDa)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Apparenta | |||

| FlaC | 189 | 4.22 | 21.5 | 31 |

| FlaD | 363 | 4.53 | 41.9 | 52, 15b |

| FlaE | 136 | 5.40 | 15.4 | 15 |

| FlaF | 133 | 5.21 | 14.6 | 14 |

| FlaG | 151 | 5.88 | 16.2 | ND |

| FlaH | 231 | 8.97 | 25.8 | 30 |

| FlaI | 553 | 5.80 | 63.1 | 73 |

| FlaJ | 599 | 8.31 | 63.0 | ND |

Determined by immunoblotting of SDS-PAGE-separated proteins. ND, not determined.

flaD encodes two proteins, as determined by immunoblotting of cell fractions.

No obvious recombinant FlaF production was apparent after 2 h postinduction; however, immunoblotting with anti-His antibodies revealed that a His-tagged protein was being produced, albeit at a minimal level (Fig. 4). The codon usage and hydrophobic character of FlaF may be factors that limit its expression in E. coli. Attempts to increase the level of expression with a plasmid carrying specific tRNA genes (28) or by inducing at lower temperatures were not successful. Furthermore, most of the target protein accumulated in inclusion bodies that, when solubilized, released only small amounts of recombinant FlaF. From these expression experiments, and in our hands, it was not possible to affinity purify FlaF.

Interestingly, overexpression of recombinant FlaI was aided by the presence of a plasmid (pSJS1240) that possesses the genes for tRNAAUA and tRNAAGA/AGG, which are rarely used in E. coli (28) but are favored in Methanococcus species, whose genomes are AT rich (41). A strong induction product of approximately 73 kDa was observed in SDS-PAGE of cell lysates (Fig. 4A, lane 9), although flaI is predicted to encode a protein with a molecular mass of 63.1 kDa.

Overexpression of recombinant FlaG and FlaJ was not achieved, even after thorough efforts. The use of plasmids carrying tRNA genes or lower induction temperatures was ineffective in both cases, as were attempts to clone and express a truncated version of flaJ.

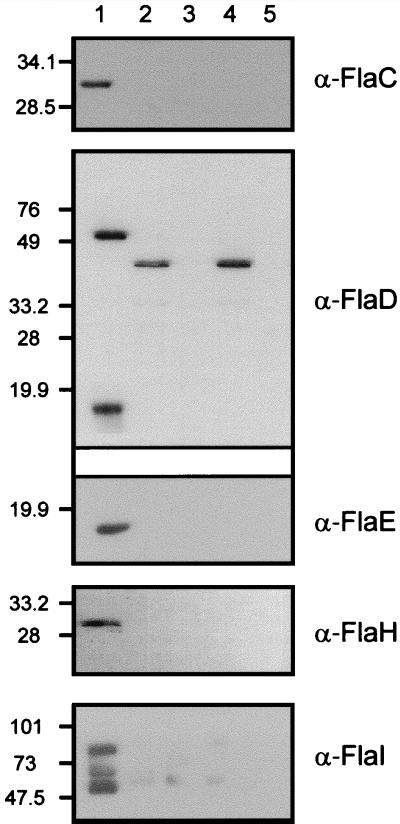

Localization of flagellar accessory proteins in M. voltae.

Cell fractions (membrane or particulate [insoluble] and cytoplasmic [soluble]) and purified flagella were generated and used in immunoblots developed with polyclonal antibodies raised against the recombinant flagellar accessory proteins. A nonflagellated M. voltae mutant, P2, with an insertion in flaB2 that does not express any of the downstream genes (23) was used as a negative control. A summary of the localization data is presented in Table 2. An antibody raised against recombinant FlaC detected a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 31 kDa exclusively in the membrane fractions of cells (Fig. 5). This molecular mass compares closely with that of the His-tagged FlaC that was overexpressed in E. coli. Two proteins with apparent molecular masses of approximately 52 and 15 kDa were detected solely in the membrane fractions of cells with an antibody raised against recombinant FlaD. In agreement with the corrected flaD gene sequence, the apparent molecular mass of the native FlaD (52 kDa) of M. voltae is greater than that of the protein that is expressed in E. coli (49 kDa), since the latter is missing the first 21 aa of the protein. Moreover, the detection of a protein with an apparent molecular mass of 15 kDa in M. voltae with the polyclonal anti-FlaD antibody suggests that translation may also initiate at a downstream location within the ORF. As observed from flaD expression in E. coli, a putative second ribosome binding site may allow for translation of the 15-kDa protein.

FIG. 5.

Subcellular localization of flagellar accessory proteins in M. voltae. Fractionated M. voltae cells and purified flagellar filaments were subjected to immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies raised against purified recombinant flagellar accessory proteins. A nonflagellated M. voltae mutant, P2, which does not express any of the flagellar accessory genes due to insertional inactivation of the flagellar gene family (23), was included as a negative control. Approximately 20 μg of protein was loaded per lane. For FlaC and FlaH, 40 μg of protein was required for immunodetection. The antibodies used in the detection are indicated to the right of each panel. Lane designations apply to all the panels. Lane 1, M. voltae membrane fraction; lane 2, M. voltae cytoplasmic fraction; lane 3, P2 membrane fraction; lane 4, P2 cytoplasmic fraction; lane 5, purified M. voltae flagellar filaments. The α-FlaD antibody preparation cross-reacts with a soluble protein present in both the wild type and the P2 mutant; however FlaD localization is confirmed by the absence of a signal in the membrane fraction of the P2 mutant. Three protein species are recognized by the α-FlaI antibodies.

Polyclonal antibodies raised against recombinant FlaE detected a 15-kDa protein in the membrane fraction of M. voltae. Since FlaD and FlaE share sequence similarity, there was a possibility that the 15-kDa protein identified was a polypeptide derived from FlaD. An experiment to determine if the anti-FlaE antibodies could detect recombinant FlaD was performed. The reciprocal experiment to determine if polyclonal anti-FlaD could detect recombinant FlaE was also carried out. In these experiments the respective antibody preparations demonstrated specificity for the proteins they were raised against and did not exhibit any significant cross-reaction with other proteins (data not shown).

Immunoblots developed with anti-FlaH antibodies detected a 30-kDa protein in the membrane fractions of cells (Fig. 5). Interestingly, recombinant-FlaH expressed in E. coli was mostly soluble and remained in the cytoplasm. Immunoblotting with anti-FlaI antibodies detected three protein species (with approximate molecular masses of 85, 70, and 55 kDa) in the membrane fractions of M. voltae cells (Fig. 5). However, when an induced culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pKJ266 was analyzed, a single protein of approximately 73 kDa (corresponding to recombinant FlaI) was detected by the anti-FlaI antibodies. It is possible that the polyclonal antibody preparation recognizes different forms of the protein in M. voltae or that homologues with epitopes similar to FlaI exist.

Flagella with some attached basal structure were isolated by using OP-10 detergent and were used in immunoblot analyses with anti-FlaC (α-FlaC), α-FlaD, α-FlaE, α-FlaH, or α-FlaI antibodies. No cross-reacting proteins were revealed by any of the antibody preparations, indicating that none of the putative flagellar accessory proteins are major components of flagellar filaments.

Thermostability of methanogen flagellar filaments.

To evaluate flagellar filament thermostability, crude flagellar filament preparations were isolated from each of M. maripaludis, M. thermolithotrophicus, and M. jannaschii and were then incubated at 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, or 90°C. M. maripaludis flagellar filaments retained structure up to 70°C, as viewed by electron microscopy of negatively stained, heat-treated preparations, whereas samples incubated at 80 or 90°C showed aggregated proteins and no evidence of intact filament structures (data not shown). Flagellar filaments isolated from M. thermolithotrophicus and M. jannaschii retained a filament structure up to 90°C, as viewed by electron microscopy.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here characterize flagellar gene families of closely related methanococci and demonstrate for the first time the expression and subcellular localization of specific known and putative flagellar accessory proteins in M. voltae.

The deduced flagellin sequences from each of the methanococci studied exhibit considerable sequence conservation over the first 35 aa of the mature protein. Multiple flagellin genes with high sequence similarity are common in the genomes of flagellated archaeal species, although mutant studies with some archaea demonstrate that the different flagellins are not simply interchangeable in vivo and likely have defined roles (23, 44). In Methanococcus spp., it appears that not all of the flagellins are present in large amounts within the filament. Furthermore, differential transcription patterns of specific flagellin genes suggest that some may be expressed at lower levels in the cell (24). Interestingly, the flagellin genes transcribed at the lowest levels in their respective gene families (flaB3Mm, flaB4Mt, and flaB3Mj) possess shorter leader peptides (11 aa, compared to the typical 12), as first observed in flaB3Mv (24). Although the overall leader sequence is not highly conserved, a net positive charge is present, and the three amino acids preceding the cleavage site tend to be KKG, KRG, or RRG. It has been demonstrated that a positively charged amino acid at position −2 and a small amino acid (glycine or alanine) at position −1 are important for preflagellin processing in M. voltae (46). Furthermore, that study identified other amino acids involved in processing that are also found in the flagellins identified in this study.

The cotranscription of at least some of the flagellar accessory genes with the flagellin genes may allow for their concerted regulation by transcriptional activators or repressors and DNA sequence elements. In M. jannaschii, a 10-nucleotide direct-repeat sequence is located upstream of the first flagellin gene. This sequence could potentially serve as a regulatory element for the flagellar gene family's expression. Examples of DNA elements involved in regulating gene expression in methanogens include heptameric direct-repeat sequences that regulate selenium-free hydrogenase gene expression in M. voltae (37) and an inverted repeat that acts as a repressor binding site to regulate nif (nitrogen fixation) gene expression in M. maripaludis (8). Interestingly, a hydrogen partial-pressure control on the expression of flagella in M. jannaschii has been reported (35), although the mechanism of the regulation was not determined.

The flagellar gene families identified in this study are composed of multiple flagellin genes followed immediately by a number of conserved genes, some of which have been shown to be involved in flagellation (23, 47). It is likely that additional genes exist, but sequencing downstream of flaJ in M. voltae, M. maripaludis, and M. thermolithotrophicus has identified genes that are not predicted to be involved in flagellar biogenesis (unpublished data). In M. jannaschii, there are some genes downstream of flaJ that could be cotranscribed and possibly involved in flagellation, but as yet no data are available to support their role in flagellation. Although the functions of FlaCDEFGHIJ have not been determined, valuable information on their gene products is presented here. FlaC, FlaD, FlaE, FlaH, and FlaI were all detected in the membrane fractions of cells, although transmembrane segment models do not predict these proteins to have membrane-spanning domains, except for FlaI, which is predicted to have a C-terminal membrane-spanning domain. Moreover, the flagellar accessory proteins are not major components of flagella, although there still remains the possibility that these proteins interact with flagella but are not strongly associated and are therefore lost in flagellum isolation procedures. Alternatively, these proteins may have a role in the secretion and translocation of flagellins or possibly in the assembly of flagella.

FlaD and FlaE of M. voltae were readily detected, in agreement with the findings of a study describing two-dimensional protein gel analysis of M. jannaschii (grown under low H2 partial pressure), where mass spectroscopy analysis of selected polypeptide spots identified FlaD, FlaE, and other proteins (35). Strangely, only a ∼16-kDa C-terminal portion of FlaD was detected in that study, and as a result it was considered to be a cleavage product of the entire FlaD protein (calculated molecular mass, 39.95 kDa). The N-terminal sequencing data presented here for the 16-kDa overexpressed protein derived from pKJ198 strongly suggest that an internal ribosome binding site within the ORF results in a shorter version of FlaD. Our ability to readily detect this shorter version of FlaD, as well as the full-length 52-kDa FlaD protein, in M. voltae demonstrates their presence in vivo. No mRNA for flaD can be detected in a flaB2 insertional mutant (unpublished data) that exhibits transcriptional polar effects on downstream genes (23); therefore, the 15-kDa FlaD species is likely translated from a downstream ribosome binding site and not derived from a different transcript. Putative downstream ribosome binding sites followed by in-frame translational start codons are evident within the flaD homologues of M. maripaludis, M. thermolithotrophicus, and M. jannaschii. The short versions of FlaD (predicted to be approximately 135 aa long) are similar in sequence, size, and pI to FlaE of the respective methanogen. Thus, flaD might encode two proteins, one of which is very similar to FlaE. Further studies characterizing FlaD and FlaE are required to assess the functions of these proteins.

Since the flagellins identified for the methanogens in this study share considerable sequence similarity, it was hypothesized that minor differences in flagellin amino acid composition are responsible for the observed increases in thermostability for the flagellar filaments of M. thermolithotrophicus and M. jannaschii. Indeed, a study evaluating large amounts of sequence data from closely related mesophilic and thermophilic Methanococcus species has identified recurring themes for thermal adaptation (20). The protein properties that were found to correlate most closely with thermophiles include higher residue volume, higher residue hydrophobicity, more charged amino acids, and fewer uncharged polar residues. By use of the amino acid category assignments of Haney et al. (20), the flagellins of M. thermolithotrophicus and M. jannaschii do indeed have slight increases in hydrophobic amino acid content (42 to 45%) compared with the mesophilic methanococcal flagellins (40%) and also have a lower polar uncharged residue content. However, these flagellins do not have a higher charged-amino-acid content than their mesophilic counterparts. Nonetheless, hydrophobic interactions have previously been associated with increased thermostability of proteins in methanogens (19). Since the flagella of methanococcal hyperthermophiles and thermophiles are present in high-temperature environments, slight increases in hydrophobic interactions (along with other stabilizing forces) may serve to achieve flagellar filament thermostability, as could posttranslational modifications.

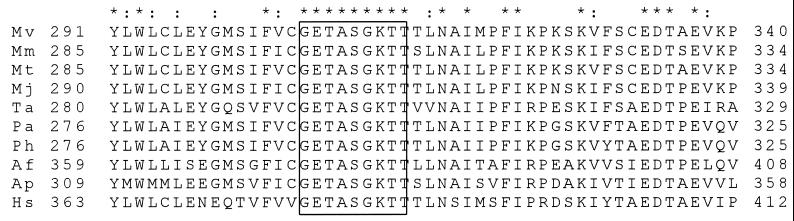

A common trend for this flagellar gene family is multiple flagellin genes followed by at least the flaHIJ genes, which are found in all flagellated archaea for which data are currently available. In all available flaI genes from diverse archaeal species, an invariant Walker box A sequence is present (Fig. 6), indicating an essential role of this motif in flagellar biogenesis. Based on the homology of FlaI to PilB (3), a demonstrated type II secretion protein, and the finding that FlaH and FlaI localize to the membrane, it is presumed that FlaH and FlaI are involved in flagellin secretion. Indeed, an M. voltae strain with an insertional mutation in flaH (affecting flaI as well, due to transcriptional polar effects) makes abundant levels of flagellin but does not secrete flagellins and does not form flagella on the cell surface (47). Furthermore, flaJ (immediately downstream of flaH and flaI) is predicted to be a protein with 7 to 9 transmembrane domains that may form a secretory complex with FlaH and FlaI (45). Additional work will be required to determine the biological functions of these gene products in order to elucidate their involvement in flagellar biogenesis in the methanogenic archaea.

FIG. 6.

Partial amino acid sequence alignment of all archaeal FlaI proteins currently available in public databases. The bordering amino acid positions of each polypeptide are shown. The putative Walker box A motif is boxed. Asterisks indicate invariant amino acids; colons indicate similar amino acids. Abbreviations: Mv, M. voltae; Mm, M. maripaludis; Mt, M. thermolithotrophicus; Mj, M. jannaschii; Ta, Thermoplasma acidophilum; Pa, Pyrococcus abyssi; Ph, Pyrococcus horikoshii; Af, A. fulgidus; Ap, Aeropyrum pernix; Hs, H. salinarum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sonia Bardy for isolating purified flagellar filaments and Aleksandra Lalovic for cloning part of the M. maripaludis flagellar gene family. pSJS1240 was kindly provided by Steven Sandler. OP-10 detergent was a generous gift from S.-I. Aizawa.

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to K.F.J. N.A.T. was the recipient of an Ontario Graduate Scholarship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auer J, Spicker G, Böck A. Organization and structure of the Methanococcus transcriptional unit homologous to the Escherichia coli “spectinomycin operon”: implications for the evolutionary relationship of 70S and 80S ribosomes. J Mol Biol. 1989;209:21–36. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A, Jarrell K F. Flagellin genes of Methanococcus vannielii: amplification by the polymerase chain reaction, demonstration of signal peptides and identification of major components of the flagellar filament. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s004380050777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayley D P, Jarrell K F. Further evidence to suggest that archaeal flagella are related to bacterial type IV pili. J Mol Evol. 1998;46:370–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayley D P, Jarrell K F. Overexpression of Methanococcus voltae flagellin subunits in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a source of archaeal preflagellin. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4146–4153. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4146-4153.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley D P, Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F. Effect of bacitracin on flagellar assembly and presumed glycosylation of the flagellins of Methanococcus deltae. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burggraf S, Fricke H, Neuner A, Kristjansson J, Rouvier P, Mandelco L, Woese C R, Stetter K O. Methanococcus igneus sp. nov., a novel hyperthermophilic methanogen from a shallow submarine hydrothermal system. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Kupiec R, Blank C, Leigh J A. Transcriptional regulation in Archaea: in vivo demonstration of a repressor binding site in a methanogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1316–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins F S, Weisman S M. Directional cloning of DNA fragments at a large distance from an initial probe: a circularization method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6812–6816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.21.6812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correia J D, Jarrell K F. Posttranslational processing of Methanococcus voltae preflagellin by preflagellin peptidases of M. voltae and other methanogens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:855–858. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.855-858.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cserzo M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. Prediction of transmembrane α-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 1997;10:673–676. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faguy D M, Bayley D P, Kostyukova A S, Thomas N A, Jarrell K F. Isolation and characterization of flagella and flagellin proteins from the thermoacidophilic archaea Thermoplasma volcanium and Sulfolobus shibatae. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:902–905. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.902-905.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faguy D M, Jarrell K F. A twisted tale: the origin and evolution of motility and chemotaxis in prokaryotes. Microbiology. 1999;145:279–281. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faguy D M, Jarrell K F, Kuzio J, Kalmokoff M L. Molecular analysis of archaeal flagellins: similarity to the type IV pilin-transport superfamily widespread in bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40:67–71. doi: 10.1139/m94-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrante G, Richards J C, Sprott G D. Structures of polar lipids from the thermophilic, deep-sea archaeobacterium Methanococcus jannaschii. Biochem Cell Biol. 1990;68:274–283. doi: 10.1139/o90-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerl L, Deutzmann R, Sumper M. Halobacterial flagellins are encoded by a multigene family. Identification of all five gene products. FEBS Lett. 1989;244:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerl L, Sumper M E. Halobacterial flagellins are encoded by a multigene family. Characterization of five flagellin genes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:13246–13251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gernhardt P, Possot O, Foglino M, Sibold L, Klein A. Construction of an integration vector for use in the archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae and expression of a eubacterial resistance gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;221:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00261731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haney P, Konisky J, Koretke K K, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes P G. Structural basis for thermostability and identification of potential active site residues for adenylate kinases from the archaeal genus Methanococcus. Proteins. 1997;28:117–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199705)28:1<117::aid-prot12>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haney P J, Badger J H, Buldak G L, Reich C I, Woese C R, Olsen G J. Thermal adaptation analyzed by comparison of protein sequences from mesophilic and extremely thermophilic Methanococcus species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3578–3583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarrell K F, Kalmokoff M L, Koval S F, Faguy D M, Karnauchow T M, Bayley D P. Purification of the flagellins from the methanogenic archaea. In: Robb F T, Sowers K R, DasSarma S, Place A R, Schreier H J, Fleischmann E M, editors. Archaea: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarrell K F, Bayley D P, Correia J D, Thomas N A. Recent excitement about the Archaea. BioScience. 1999;49:530–541. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarrell K F, Bayley D P, Florian V, Klein A. Isolation and characterization of insertional mutations in flagellin genes in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:657–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5371058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F. Cloning and sequencing of a multigene family encoding the flagellins of Methanococcus voltae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7113–7125. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7113-7125.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalmokoff M L, Koval S F, Jarrell K F. Relatedness of the flagellins from methanogens. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:481–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00276766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalmokoff M L, Jarrell K F, Koval S F. Isolation of flagella from the archaebacterium Methanococcus voltae by phase separation with Triton X-114. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1752–1758. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1752-1758.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler P S, Blank C, Leigh J A. The nif gene operon of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1504–1511. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1504-1511.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim R, Sandler S J, Goldman S, Yokota H, Clark A J, Kim S-H. Overexpression of archaeal proteins in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 1998;20:207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J F, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, D'Andrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kostyukova A S, Gongadze G M, Obraztsova A Y, Laurinavichus K S, Fedorov O V. Protein composition of Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus flagella. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:1162–1166. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koval S F, Jarrell K F. Ultrastructure and biochemistry of the cell wall of Methanococcus voltae. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1298–1306. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1298-1306.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lechner J, Wieland F. Structure and biosynthesis of prokaryotic glycoproteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:173–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maupin-Furlow J A, Ferry J G. Analysis of the CO dehydrogenase/acetyl-coenzyme A synthase operon of Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6849–6856. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6849-6856.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukhopadhyay B, Johnson E F, Wolfe R S. A novel pH2 control on the expression of flagella in the hyperthermophilic, strictly hydrogenotrophic methanarchaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11522–11527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagahisa K, Ezaki S, Fujiwara S, Imanaka T, Takagi M. Sequence and transcriptional studies of five clustered flagellin genes from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noll I, Muller S, Klein A. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding the selenium-free [NiFe]-hydrogenases in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae involves positive and negative control elements. Genetics. 1999;152:1335–1341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nunn D. Bacterial type II protein export and pilus biogenesis: more than just homologies? Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:402–408. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01634-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nunn D, Bergman S, Lory S. Products of three accessory genes, pilB, pilC, and pilD, are required for biogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2911–2919. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2911-2919.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsen G J, Woese C R. Archaeal genomics: an overview. Cell. 1997;89:991–994. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeve J N. Structure and organization of genes. In: Ferry J G, editor. Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry and genetics. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1993. pp. 493–527. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph J, Oesterhelt D. Deletion analysis of the che operon in the archaeon Halobacterium salinarium. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:548–554. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct the expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarasov V Y, Pyatibratov M G, Tang S, Dyall-Smith M, Fedorov O V. Role of flagellins from A and B loci in flagella formation of Halobacterium salinarum. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:69–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas N A, Bardy S L, Jarrell K F. The archaeal flagellum: a different kind of prokaryotic motility structure. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:147–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas N A, Chao E D, Jarrell K F. Identification of amino acids in the leader peptide of Methanococcus voltae preflagellin that are important in posttranslational processing. Arch Microbiol. 2001;175:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s002030100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas N A, Pawson C T, Jarrell K F. Insertional inactivation of the flaH gene in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae results in non-flagellated cells. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;265:596–603. doi: 10.1007/s004380100451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Towbin M, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitchurch C B, Hobbs M, Livingston S P, Krishnapillai V, Mattick J S. Characterisation of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility gene and evidence for a specialised protein export system widespread in eubacteria. Gene. 1991;101:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90221-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitman W B. Order II Methanococcales, Balch and Wolfe 1981, 216VP. In: Holt J G, editor. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 3. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. pp. 2185–2190. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolfgang M, Park H S, Hayes S F, van Putten J P M, Koomey M. Suppression of an absolute defect in type IV pilus biogenesis by loss-of-function mutation in pilT, a twitching motility gene in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14973–14978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamamoto K R, Alberts B M. Rapid bacteriophage sedimentation in the presence of polyethylene glycol and its application to large scale virus purification. Virology. 1970;40:734–744. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]