Abstract

α-Alkylation of a β-keto ester is a frequently used reaction for carbon–carbon bond formation. However, extension to a stereoselective reaction remains a significant challenge, because the product easily racemizes under acidic or basic conditions. Here, we report a hybrid system consisting of Pd and Ru complexes that catalyzes the asymmetric dehydrative condensation between cinnamyl-type allylic alcohols and β-keto esters. α-Non-substituted β-keto ester can be allylated to afford an α-mono-substituted product with high regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity. No epimerization occurs owing to the nearly neutral conditions, which is achieved by a rapid proton transfer from Pd-enolate formation to Ru π-allyl complex formation. Four diastereomers can be synthesized on demand by changing the stereochemistry of the Pd or Ru complex. Eight stereoisomers with three adjacent stereogenic centers can be synthesized by employing diastereoselective reduction of the ketone in the products. The formal synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin demonstrates the utility of the reaction.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Stereochemistry

α-Alkylation of β-keto esters is a frequently used reaction for carbon–carbon bond formation, but a general, stereoselective version of this reaction is challenging to realize. Here, the authors report a combined ruthenium and palladium catalytic system for the asymmetric dehydrative condensation between cinnamyl-type allylic alcohols and β-keto esters.

Introduction

β-Hydroxy esters (βHEs) are ubiquitous structural motifs in organic synthesis, and the asymmetric hydrogenation of β-keto ester is the most promising for providing βHEs1. Although α-alkylated chiral βHE is frequently requested for constructing other complicated structures, the α-alkylation of βHEs is inefficient. Acetalization, deprotonation, alkylation, and deacetalization are generally required for diastereoselective synthesis2. Diastereoselective and enantioselective hydrogenation of α-substituted β-keto esters via dynamic kinetic resolution is attractive3. However, the substrate scope is limited, and the product is diastereospecific. From this perspective, the enantioselective alkylation of β-keto ester, also known as the acetoacetic ester synthesis, seems alluring, followed by diastereoselective reduction of the carbonyl group.

Acetoacetic ester synthesis4, which was discovered by Geuther in 1863, is a traditional and basic carbon–carbon bond-forming reaction wherein the β-keto ester is alkylated via an enol or enolate formation and reaction with alkyl halides5. Because highly functionalized compounds can be synthesized from ample substrates, this reaction has been widely used in organic syntheses. Accordingly, various enantioselective reactions have been developed6. However, there is a critical and fundamental limitation from the viewpoint of asymmetric synthesis. The enantioselective acetoacetate synthesis is generally applied to afford a quaternary carbon center using an α-alkylated β-keto ester substrate4–6. The tertiary stereogenic center is generated when a non-substituted β-keto ester is alkylated. However, the enantiopurity of the generated product is generally low because the corresponding product easily racemizes through keto–enol equilibrium, particularly under basic or acidic conditions. Although enolate formation by a base is vital to proceed the reaction, this makes it difficult to avoid racemization. Thus, the development of mono-alkylation of β-keto ester in an enantioselective manner has remained a significant issue7.

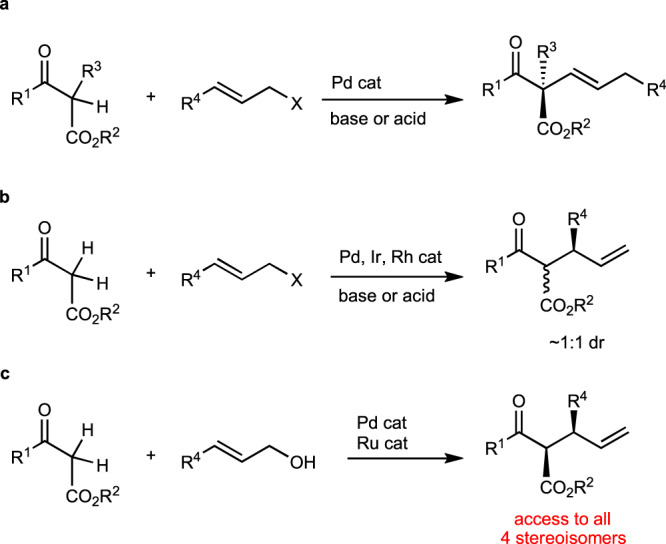

To solve this problem, we focused on Tsuji–Trost-type (T–T) asymmetric allylation8–12, which is a typical catalytic reaction for the alkylation of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds. The T–T reaction can construct a chiral carbon center at two positions, the allylic carbon and dicarbonyl methylene carbon13. In the case of dicarbonyl methylene carbon, the reaction can be applied only to quaternary carbon formation, as shown in Fig. 1a. Double stereo-differentiation occurred when the branched allylation proceeded, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. However, only the stereochemistry of the allylic position can be arranged in this strategy, generating a stereoisomeric mixture (Fig. 1b)13 due to epimerization via keto–enol equilibrium14–17. Thus, the stereodivergent synthesis has not been realized to date. Herein, we attempted to construct both the stereogenic centers using a binary catalytic system, as shown in Fig. 1c18–35. The product possessed many transformative functionalities with two chiral centers in a small molecule. This method can be extended to the synthesis of complicated chiral organic compounds.

Fig. 1. Enantioselective allylation of β-keto esters.

a Enantioselective allylation of α-monosubstituted β-keto ester. b Enantioselective allylation of an unsubstituted β-keto ester. c Stereodivergent allylation of β-keto ester (this work).

In this study, we establish the catalytic asymmetric dehydrative allylation of non-substituted β-keto esters. The catalyst design, screening result, substrate scope and limitation, consideration of reaction mechanism, extension to the construction of three adjacent stereocenters via diastereoselective reduction of ketone, and synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin are reported.

Results and discussion

Development of the catalytic system

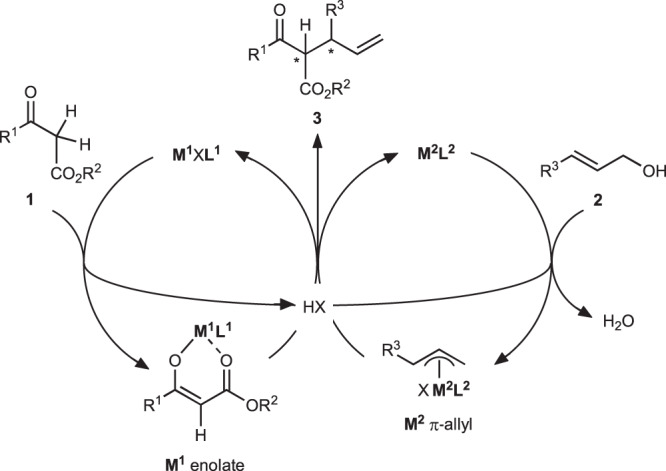

A basial strategy is illustrated in Fig. 2, which is based on stereodivergent allylation using binary chiral catalyst systems, M1XL1 and M2L2, where L1 and L2 are chiral ligands. Catalyst M1XL1 activated β-keto ester 1 to form a corresponding metal enolate (M1 enolate). Here, the anionic X functioned as a Brønsted base to abstract the proton of β-keto ester 1 with the liberation of conjugate acid, HX. Catalyst M2L2 activated allylic alcohol 2 to form a π-allyl complex (M2 π-allyl). M2L2 combined with the liberated HX can cleave a stable alcoholic C–O bond based on the Redox-mediated Donor–Acceptor Bifunctional Catalyst (RDACat) concept36. The formation of hydrogen bond between the allylic alcohol and HX activated the C–O bond, followed by the oxidative addition with M2L2, which was accompanied by the release of water. The reaction between nucleophilic M1 enolate and electrophilic M2 π-allyl produced the allylation adduct 3. The amount of HX generated during the catalytic cycle was the same as that of the introduced catalyst. Thus, the reaction proceeded under almost neutral conditions to avoid epimerization. Each chiral circumstance of M1L1 and M2L2 could discriminate the enantioface selection of enolate and π-allyl moieties, respectively. Thus, the selection of M1XL1 and M2L2 is crucial. We focused on CpRu–(S,S)-Naph-diPIM-dioxo-iPr (RuL2S) as M2L2, which catalyzes dehydrative asymmetric allylation of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds combined with Brønsted acid37,38. However, the selection of M1XL1 was a vital issue.

Fig. 2. Basic strategy for stereodivergent catalytic dehydrative allylation systems.

M1 and M2: metal atom of complex. L1 and L2: chiral ligand. X: anionic ligand.

tert-Butyl 3-oxopropanoate (1a, 500 mM) and cinnamyl alcohol (2a, 600 mM) were selected as standard substrates and investigated as M1XL1 under the following conditions: 2 mol% of M1XL1, 2 mol% of RuL2S, 1,4-dioxane, and 10 °C; the results are shown in Table 1. A complete consumption of 1a within 6 h was observed when Pd((R)-BINAP)(H2O)2(OTf)2 (PdL1R(OTf)) was used39,40, generating 3aa with high diastereo- and enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Among the four stereoisomers, (R,S)-syn-3aa was obtained in 99.7% yield while yields of (S,S)-anti-3aa, (S,R)-syn-3aa, and (R,R)-anti-3aa were 0.1, 0.2, and <0.1%, respectively. Each catalyst, PdL1R(OTf) and RuLS2, could be reduced to 0.25 mol% without the loss of yield and selectivity by elongating the reaction time (entries 2 and 3). Although the combination of RuL2R and PdL1R(OTf) (2 mol% each) afforded (R,R)-anti-3aa with high enantioselectivity, it demonstrated lower reactivity and diastereoselectivity (37%, 85:15 diastereomeric ratio (dr)); the reaction was completed in 24 h (entries 4 and 5). Consequently, the combination of RuL2R and PdL1R(OTf) was a mismatched system, while that of RuL2S and PdL1R(OTf) was a matched system. According to the investigation of conditions in a mismatched system, decreasing the amount of PdL1R(OTf) to 1 mol% increased the diastereoselectivity, generating 3aa with a dr of 96:4 in 98% yield after 72 h under lower concentrations (entries 6–8). In contrast to (R)-BINAP (L1R) in PdL1R(OTf), the more sterically hindered tol-BINAP and xyl-BINAP exhibited less reactivity (entries 9 and 10). The Pd complex of (R)-SEGPHOS exhibited reactivity and selectivity similar to that of BINAP (entry 11) without changing the stereochemistry. The reaction proceeded with the exchange of counter anion of PdL1R(OTf) with BF4, although the reactivity and diastereoselectivity were less. Conversely, the reaction did not proceed in the case of OTs (entries 12 and 13). Pd was essential as M1, while the corresponding Ni complex was ineffective (entry 14). In addition, the Cu complexes did not afford any desired product (entries 15 and 16). Compared to the previously reported allylation of Meldrum’s acid, the Brønsted acid, TfOH, or p-TsOH, could not function as a co-catalyst37, resulting in no reactivity (entries 17 and 18). Additionally, the reaction did not proceed without the Ru catalyst (entry 19). In both matched and mismatched catalyst systems, under higher temperatures, diastereoselectivity tended to become lower (further details are provided in the Supplementary Information).

Table 1.

Screening of two metal complexes catalyzing the dehydrative allylation of 1a and 2a

| Entry | M1XL1(mol%) | RuL2 (mol%) | Time (h) | Yield (%) | (R,S) | (S,S) | (S,R) | (R,R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PdL1R(OTf) (2) | RuL2S (2) | 6 | >99 | 99.7 | 0.1 | 0.2 | <0.1 |

| 2 | PdL1R(OTf) (1) | RuL2S (1) | 12 | >99 | 99.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 3 | PdL1R(OTf) (0.25) | RuL2S (0.25) | 24 | >99 | 98.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | <0.1 |

| 4 | PdL1R(OTf) (2) | RuL2R (2) | 6 | 37 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 14.8 | 85.0 |

| 5 | PdL1R(OTf) (2) | RuL2R(2) | 24 | >99 | <0.1 | 0.2 | 14.8 | 84.8 |

| 6 | PdL1R(OTf) (4) | RuL2R(2) | 24 | >99 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 21.4 | 78.5 |

| 7 | PdL1R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | >99 | <0.1 | 0.2 | 7.1 | 92.7 |

| 8a | PdL1R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | 98 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 96.0 |

| 9a | PdL3R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | 36 | <0.1 | 0.2 | 8.9 | 90.9 |

| 10a | PdL4R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 11a | PdL5R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | 91 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 3.7 | 96.1 |

| 12 | PdL1R(OTs) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 13 | PdL1R(BF4) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | 38 | <0.1 | 0.1 | 12.0 | 87.9 |

| 14a | NiL1R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 15a | CuL6R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 16a | CuL2R(OTf) (1) | RuL2R(2) | 72 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 17 | TfOH (2) | RuL2R (2) | 12 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 18 | p-TsOH (2) | RuL2R (2) | 12 | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 19 | PdL1R(OTf) (2) | (0) | 12 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

a[1a] = 125 mM, [2a] = 150 mM.

Substrate scope of the reaction

The generality of β-keto ester 1 using cinnamyl alcohol (2a) was investigated in the PdL1R(OTf)/RuL2S–matched catalyst system using 1 mol% of each catalyst; the results are illustrated in Table 2. A methyl group connecting to the carbonyl group in 1a could be replaced with H, Et, iPr, and methoxymethyl group (entries 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6, respectively) while maintaining a high level of regio-, diastereo-, or enantioselectivities. The sterically hindered tBu group completely suppressed the reactivity (entry 5). The phenyl group was an acceptable substituent (entry 7). Furthermore, the phenyl group could be functionalized with electron-donating or -withdrawing groups (entries 8 and 9). The α-methylated keto ester afforded the product with a quaternary carbon stereogenic center (entry 10). The results for cyclic substrate were also acceptable (entry 13). The α-fluorinated substrate gave a corresponding product containing tertiary alkyl fluoride (entry 12); however, the α-benzylated substrate did not exhibit any reactivity (entry 11). Next, the generality of allylic alcohol was examined using β-keto ester 1a. Fluoro, methyl, methoxy, chloro, and trifluoromethyl groups could be introduced into the phenyl group of cinnamyl alcohol at ortho, meta, or para positions (entries 14–24). The phenyl group could be replaced with other aromatic rings such as 2-naphthyl, N-Boc-3-pyrrolyl, and N-Boc-3-indolyl groups (entries 25–27). Allylic alcohols connecting to the aliphatic substituent gave a linear product as a major product, while enantioselectivity at the α-position was low (64:36 enantiomeric ratio (er); entry 28). This is the first example wherein an aliphatic allyl alcohol gives an allylated product in high yield by using a Ru–L2S system; this is in contrast to the previously reported system, which gave 1,3-diene as the major product37. Concerning stereochemistry, in the standard reaction, the R,S-configurated syn-3aa was obtained in the PdL1R(OTf)/RuL2S system. For other products (entries 2, 9, 14, 17, 20, and 27), the same absolute configuration was afforded as the major stereoisomers (further details are provided in the Supplementary Information).

Table 2.

Generality of the PdL1R(OTf)/RuL2S-matched catalyst systema

| Entry | Product 3 | Yield (%) | b/l | syn/anti | erb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c,d |  |

R = H | 82 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) |

| 2 | R = Me | 99 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) | |

| 3e | R = Et | 98 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 4e | R = iPr | 91 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 5 f | R = tBu | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 6e,f | R = CH2OCH3 | 96 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 7e |  |

R = H | 97 | >95:5 | >95:5 | 99:1 |

| 8e | R = p-CH3O | 95 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 9 | R = p-Cl | 92 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) | |

| 10e,g,h |  |

R = Me | 91 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 |

| 11i | R = Bn | <5 | n.d | n.d | n.d | |

| 12e,g,h | R = F | 89 | >95:5 | >95:5 | 99:1 | |

| 13e,g,h |  |

97 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 14 |  |

R = o-F | 99 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) |

| 15e | R = o-Me | 97 | >95:5 | >95:5 | 99:1 | |

| 16e | R = o-CH3O | 96 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 17 | R = m-F | 99 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) | |

| 18e | R = m-Me | 98 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 19e | R = m-CH3O | 96 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 20 | R = p-F | 99 | >95:5 | >95:5 | 99:1 (R,S) | |

| 21e | R = p-Cl | 97 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 22e,h,j | R = p-CF3 | 87 | 93:7 | >95:5 | 99:1 | |

| 23e | R = p-Me | 98 | >95:5 | >95:5 | 99:1 | |

| 24e | R = p-CH3O | 99 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 25 |  |

95 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) | |

| 26e,g |  |

97 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 | |

| 27 h |  |

93 | >95:5 | >95:5 | >99:1 (R,S) | |

| 28 |  |

48 | <5:95 | — | 64:36 | |

aConditions unless otherwise specified: [1] = 500 mM; [2] = 600 mM; [PdL1R(OTf)] = [RuL2S] = 5.00 mM; 1,4-dioxane 1.00 mL; 10 °C; 24 h.

bEr; enantiomer ratio. Symbols in parentheses are absolute configuration of major stereoisomer. Details on determination are provided in the Supplementary Information.

c[1] = 500 mM; [2] = 750 mM; [PdL1R(OTf)] = 1.25 mM; [RuL2S] = 2.50 mM.

dProduct was isolated as a β-hydroxy ester after one pot-reduction using K-selectride.

eRelative and absolute configurations were not determined. Structures drawn were estimated from the structure-confirmed analogs.

fReaction time 48 h.

g[1] = 250 mM; [2] = 500 mM; [PdL1R(OTf)] = [RuL2S] = 2.50 mM.

hReaction time 72 h.

i4 mol% of PdL1R(OTf) and 4 mol% of RuL2S were used.

j2 mol% of PdL1R(OTf) and 4 mol% of RuL2S were used.

Table 3 shows the generality in the mismatched-catalyst system, PdL1R(OTf) and RuL2R. In β-keto ester, ethyl- and phenyl-substituted keto esters demonstrated similar results to that of the standard substrate in a matched system; however, the iPr-type substrate was not applied (entry 1–4). α-Fluoro β-keto ester could also be used (entry 5). The scope of allylic alcohol was similar to that in the matched system.

Table 3.

Generality of the PdL1R(OTf)/RuL2R-mismatched catalyst system.a

| Entry | Product 3 | Yield (%) | b/l | syn/anti | erb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

R = Me | 99 | >95:5 | <5:95 | >99:1 (R,R) |

| 2c | R = Et | 94 | >95:5 | 8:92 | >99:1 | |

| 3 | R = iPr | <5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 4c,d | R = Ph | 93 | >95:5 | <5:95 | >99:1 | |

| 5c,d,e |  |

92 | >95:5 | 6:94 | >99:1 | |

| 6c |  |

R = o-Me | 92 | >95:5 | 5:95 | 99:1 |

| 7 | R = m-F | 95 | >95:5 | 5:95 | >99:1 | |

| 8 | R = p-F | 91 | >95:5 | 6:94 | >99:1 | |

| 9c | R = p-Cl | 95 | >95:5 | <5:95 | >99:1 | |

| 10c | R = p-Me | 97 | >95:5 | 5:95 | >99:1 | |

aConditions unless otherwise specified: [1] = 125 mM, [2] = 150 mM; [PdL1R(OTf)] = 1.25 mM; [RuL2R] = 2.50 mM; 1,4-dioxane 4.00 mL; 10 °C; 72 h.

bEr; enantiomer ratio. Symbols in parentheses are absolute configuration of major stereoisomer. The details on determination are provided in the Supplementary Information.

cRelative and absolute configurations were not determined. Structures drawn were estimated from structure-confirmed analogs.

d96 h.

e[PdL1R(OTf)] = [RuL2R] = 2.50 mM.

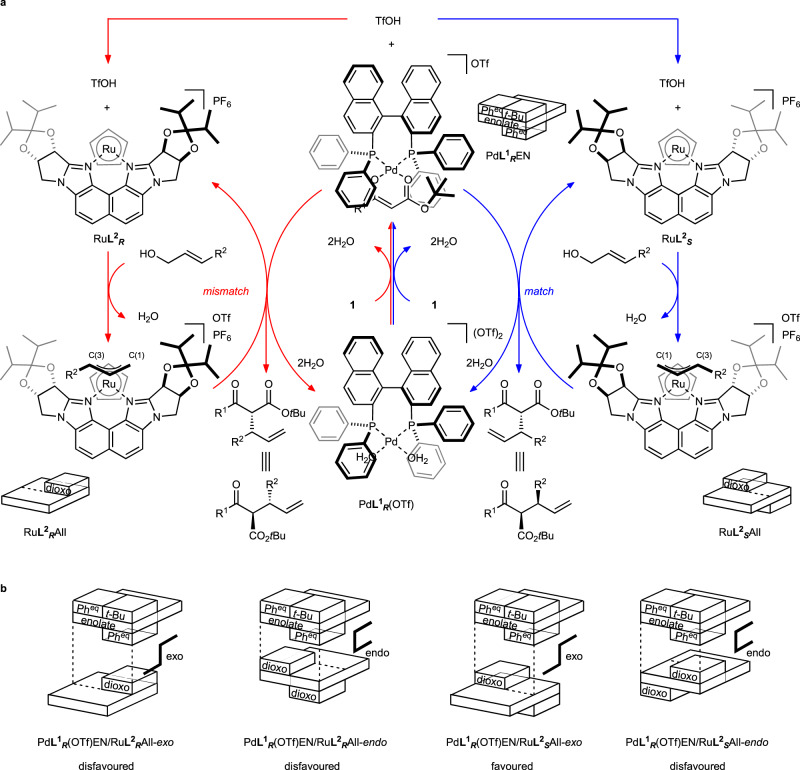

Proposed mechanism

Figure 3 illustrates the proposed catalytic cycles. The matched (blue) and mismatched (red) systems proceeded via similar mechanisms (Fig. 3a). In the blue-colored system, PdL1R(OTf) reacts with substrate 1 to form the Pd enolate (PdL1REN), wherein the enolate anionic ligand coordinates to the Pd metal in a bidentate manner. In addition, the reaction liberates TfOH, which collaborates with RuL2S to activate the allylic alcohol based on the RDACat mechanism36 to form endo-π-allyl species (RuL2SAll), releasing a water molecule. The Pd enolate then attacks the allyl group, producing adduct 3 with the regeneration of PdL1R(OTf) and RuL2S. In the π-allyl complex RuL2SAll formation, one of the two possible diastereomers was selectively generated owing to chiral ligand L2S. The substituent R2 on the π-allyl group is placed at one of the syn-positions away from the sterically hindered dioxolane moiety of the chiral ligand L2S; thus, ruthenium occupies the Si face on C(3) of the π-allyl ligand (when R2 is Ph) as illustrated for RuL2SAll37. In PdL1REN, the two pseudo-equatorial phenyl groups on the phosphinyl group of BINAP shield the planal enolate, and the tBu group on the carboxylate stands up to avoid steric repulsion with a phenyl group of BINAP. Consequently, the two phenyl groups and a tBu group occupy the spaces, which is similar to that illustrated for PdL1REN41. The Pd enolate approaches the RuL2SAll from outside to generate (R,S)-3 as the major isomer. The enantioface selections are consistent with those in the previous reports37,40. The bulkiness of the tBu group on the ester is important, and also demonstrated in the previous report40. Moreover, a methyl ester substrate corresponding to 1a gave ca. 1:1 diastereomeric mixture. In both matched and mismatched cases, the enantioface selectivity of the π-allyl moiety was almost perfect, and the selection of Pd enolate was highly affected by the steric repulsion.

Fig. 3. Proposed reaction mechanism.

a Catalytic cycle of the matched (blue) and mismatched (red) systems using PdL1R(OTf) complex with RuL2S or RuL2R complex. b Pattern diagram of nucleophilic addition for realizing the origin of diastereoselectivity. EN enolate ligand, All allyl ligand.

Models for the nucleophilic attack in the matched or mismatched system are shown in Fig. 3b. The nucleophilic attack proceeds via one of the two patterns by considering the relative stereochemistry between the binaphthyl backbone of BINAP (L1) and the naphthalene backbone of Naph-diPIM-dioxo-iPr (L2) at exo and endo positions. The PdL1REN/RuL2SAll-exo intermediate had good stereocomplementarity in the matched system, whereas the endo structure exhibited steric repulsion. A similar mechanism was followed in the mismatched system. Although the endo intermediate was better than the exo intermediate, it was unfavorable as the backbones closed each other. Furthermore, the mismatched system had low reactivity and diastereoselectivity due to the steric repulsion of both the intermediates.

Over allylation product was not obtained in the current catalytic system. The phenomenon is similar to a PdL1(OTf)-catalyzed α-alkylation of α-alkyl β-keto esters, in which the acceptable substrates are limited to only smaller substituents40. Enolate formation of the allylated β-keto ester with PdL1(OTf) is presumably difficult (Table 2, entry 11) owing to steric reasons. The nucleophilic addition does not proceed even when the enolate is formed and the enolate may be protonated stereoselectively to reverse the mono-allylated product 342,43.

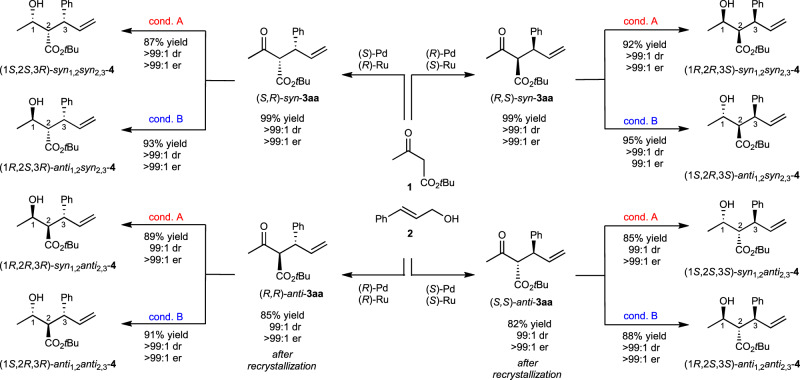

Diastereoselective reduction of carbonyl group

The reduction of the carbonyl group of the adduct 3 gave a βHE, generating another stereogenic center. Three adjacent chiral carbon centers can be controlled by employing diastereoselective reduction, which is summarized in Fig. 4. For example, (R,S)-syn-3aa, the product generated in the matched PdL1R(OTf)/RuL2S system, was reduced by K-selectride (cond. A) to afford syn,syn-4. The origin of diastereoselectivity is further explained by the Felkin–Ahn model. The Luche reduction using LaCl3/NaBH4 also gave syn,syn-4 in high selectivity (93:7 dr). In contrast, the substrate (R,S)-syn-3aa was reduced to another diastereomer, anti,syn-4, using Zn(BH4)2 (cond. B)44. In this case, the reduction proceeded via the Zimmerman–Traxler chelation model. Enantiomeric (S,S,R)-syn,syn-4 and (R,S,R)-anti,syn-4 were obtained from (S,R)-syn-3aa. Diastereomeric adducts 3s, (R,R)- and (S,S)-anti-substrates, could also be reduced with high diastereoselectivity by the same methods. A total of eight diastereomers were synthesized by introducing these reduction methods combined with stereodivergent allylation.

Fig. 4. Acyclic stereocontrolled synthesis of eight possible isomers with three adjacent stereogenic centers.

Condition A: [3aa] = 0.1 M, K-selectride 0.35 M, THF, −78 °C, 12 h; Condition B: [3aa] = 0.1 M, Zn(BH4)2 0.1 M, CH2Cl2-Et2O, 0 °C, 6 h. THF: tetrahydrofuran.

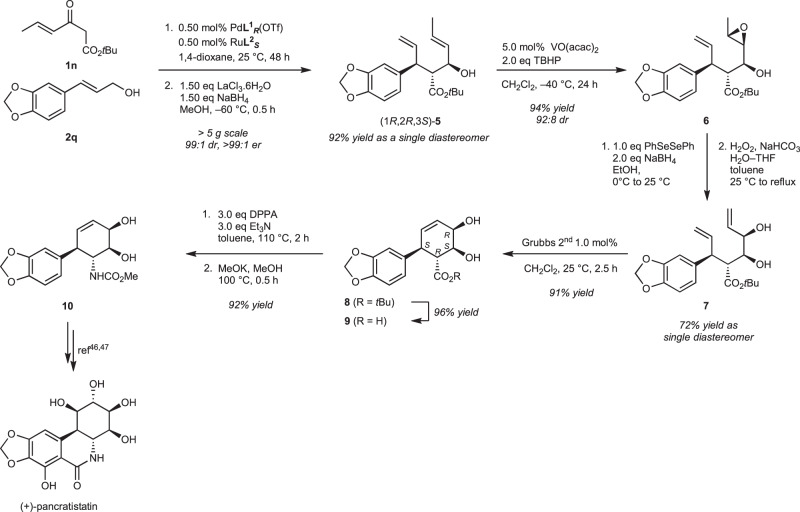

Formal synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin

Thus, compounds with highly condensed stereogenic centers can be synthesized using the above method. These compounds can be further extended to synthesize complex molecules owing to the easily transformative carboxylic ester and olefinic moiety. Herein, we applied our method to the formal synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin to demonstrate the utility of the products45–47.

The result is illustrated in Fig. 5 (further details are provided in the Supplementary Information). The β-keto ester 1n and the allylic alcohol 2q were dehydratively condensed using the above catalytic method (0.5 mol% of PdL1R(OTf) and RuL2S, 1,4-dioxane, 25 °C, 48 h, >99% yield (NMR), >99:1 er, 99:1 dr). The product was reduced in the one-pot reaction under Luche’s conditions to afford the hydroxy ester 5 as a single diastereomer in 92% total yield after the isolation process. The internal double bond was converted to oxirane via hydroxy group-triggered regio-/diastereoselective epoxidation by VO(acac)2/tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP), in 94% yield and 92:8 dr48. The epoxide moiety was converted to allylic alcohol via regioselective ring-opening by sequential nucleophilic selenol addition and oxidation of selenyl ether followed by β-elimination49. The corresponding product 7 was cyclized to cyclohex-3-en-1,2-diol 8 by ring-closing metathesis using 1 mol% of Grubb’s 2nd generation catalyst and obtained in 91% yield. Ester hydrolysis of 8 gave carboxylic acid 9 in quantitative yield. The Curtius rearrangement of acid 9 followed by the CH3OK treatment gave intermediate 10 in 92% yield; the intermediate was previously reported by Hudlicky et al.46. Although the number of steps and the total yield were not the most outstanding47, the chemical yield of each step was high. Thus, stereocontrolling is simple when each chiral catalyst is appropriately used, and various stereoisomers can be synthesized by changing the chirality of the catalysts and the types of reagents. Additionally, the usage of protecting groups can be reduced.

Fig. 5. Formal synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin.

TBHP tert-butyl hydroperoxide, THF tetrahydrofuran, DPPA diphenylphosphoryl azide.

In summary, we established enantio- and diastereoselective dehydrative allylation of β-keto esters in a stereodivergent manner using a binary catalyst system involving PdL1(OTf) and RuL2. This method can be applied to α-non-substituted keto esters to generate products with tertiary stereogenic centers, which are easily epimerized to a diastereomeric mixture under acidic or basic conditions. During the dual catalytic cycle, PdL1(OTf) and keto ester substrates generate Pd-enolate species and liberate a Brønsted acid; the acid acts as a co-catalyst of RuL2 to form π-allyl species and water. This concerted mechanism facilitates nearly neutral conditions to avoid product epimerization. Although the PdL1(OTf)/RuL2 combination exhibited matched/mismatched stereocomplimentarity, both combinations gave >95:5 diastereoselectivity. A wide range of generality allowed the changing of the substituents at the β-position of the keto ester, and aromatic rings of allylic alcohol were realized. Moreover, a quaternary stereogenic carbon center was constructed using α-alkyl β-keto ester. By introducing diastereoselective reduction of the carbonyl group, a total of eight possible diastereomeric isomers could be synthesized on demand. The utility of the highly-stereogenic-center-condensed product was realized by the formal synthesis of (+)-pancratistatin. With the increasing importance of stereodivergent synthesis owing to recent achievement50–53, this method can further improve the utility of beneficial acetoacetic ester synthesis.

Method

General procedure for dehydrative allylation of β-keto ester

The detailed operation was described by taking the dehydrative allylation of β-keto ester 1a with allylic alcohol 2a catalyzed by PdL1R(OTf) and RuL2S (matched system) as the representative (Table 2, entry 2). A 10 mL Young-type Schlenk tube was charged with [RuCp(CH3CN)3]PF6 (2.16 mg, 4.97 μmol), L2S (2.73 mg, 5.01 μmol), and CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 30 min, and then the resulting pale-yellow solution was concentrated in vacuo. To this were added PdL1R(OTf) (5.30 mg, 4.99 μmol), 1a (81.5 μL, 79.0 mg, 0.500 mmol) and a 0.600 M 1,4-dioxane solution of 2a (1.00 mL, 0.600 mmol) under Ar atmosphere. The resulting red-brown solution was stirred at 10 °C for 12 h, resulting in a pale-yellow solution. The reaction mixture was filtered through a short-pad of silica gel and washed two times by a 10:1 hexane/EtOAc mixture. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by using neutralized SiO2-chromatography (20 g; toluene eluent, note: to prevent epimerization of product, flash chromatography was performed as fast as possible, normally within 5 min) to produce syn-3aa as a white solid (136.9 mg, 99.8%).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers JP16H02274 (MK), JP20K21191 (MK), and JP21K05052 (ST)), the Advanced Catalytic Transformation Program for Carbon Utilization (ACT-C, JPMJCR12YC) (MK), and ERATO (JPMJER2103) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) (ST), and The Naito Foundation (ST). LPT is thankful to the Kobayashi Foundation for the Special Research Fellowship.

Author contributions

S.T. and M.K. designed this study. L.P.T., M.Y., and S.T. conducted the experiments. M.K. and K.S. oversaw the project. S.T., K.S., and M.K. wrote the manuscript. L.P.T., M.Y., and S.T. wrote the Supplementary Information.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Wanbin Zhang and Weiwei Zi for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

All crystallographic data generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) database under accession code 2193030 ((R,S)-syn-3aa), 2193039 ((R,R)-anti-3aa), 2193045 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11aa), 2193050 ((1R,2R,3R)-syn1,2anti2,3-11aa), 2193051 ((1S,2R,3R)-anti1,2anti2,3-11aa), 2193052 ((2R,3S)-syn-11ba), 2193053 ((R,S)-syn-3ia), 2193054 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ab), 2193059 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ae), 2193062 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ah), 2193063 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11am), 2193064 ((R,S)-syn-3ao), and 2193066 (8). For compound numbers, see Supplementary Information. All other data relating to the findings of this study, NMR spectrum, and HPLC charts are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shinji Tanaka, Email: tanaka-sh@aist.go.jp.

Masato Kitamura, Email: kitamura@ps.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-33432-4.

References

- 1.Noyori R, et al. Asymmetric hydrogenation of β-keto carboxylic esters. A practical, purely chemical access to β-hydroxy esters in high enantiomeric purity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5856–5858. doi: 10.1021/ja00253a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann J, Seebach D, Ha TK. Highly diastereoselective α-alkylation of β-hydroxycarboxylic acids through lithium enolates of 1,3-Dioxan-4-ones. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1988;71:1143–1155. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19880710527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noyori R, et al. Stereoselective hydrogenation via dynamic kinetic resolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:9134–9135. doi: 10.1021/ja00207a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geuther A. Untersuchungen über die Einbasischen Säuren. Arch. Pharm. 1863;166:97–110. doi: 10.1002/ardp.18631660202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benetti S, Romagnoli R, De Risi C, Spalluto G, Zanirato V. Mastering β-keto esters. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1065–1114. doi: 10.1021/cr00036a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Govender T, Arvidsson PI, Maguire GEM, Kruger HG, Naicker T. Enantioselective organocatalyzed transformations of β-ketoesters. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:9375–9437. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trillo P, Baeza A, Nájera C. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of β-keto esters with xanthydrols. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013;355:2815–2821. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201300627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trost BM, Van Vraken DL. Asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed allylic alkylations. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:395–422. doi: 10.1021/cr9409804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji, J. Palladium Reagents and Catalysts (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2005).

- 10.Mohr JT, Stoltz BM. Enantioselective Tsuji allylations. Chem. Asian J. 2007;2:1476–1491. doi: 10.1002/asia.200700183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Z, Ma S. Metal-catalyzed enantioselective allylation in asymmetric synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:258–297. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng Q, et al. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic substitution reactions. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:1855–1969. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng N, Song W. Progress on transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation reaction of 1,3-Dicarbonyl compounds. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2017;37:1099. doi: 10.6023/cjoc201702013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trost BM, Radinov R, Grenzer EM. Asymmetric alkylation of β-ketoesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:7879–7880. doi: 10.1021/ja971523i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunel JM, Tenaglia A, Buono G. Enantioselective formation of quaternary centers on β-ketoesters with chiral palladium QUIPHOS catalyst. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2000;11:3585–3590. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)00337-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu W-B, Reeves CM, Stoltz BM. Enantio-, diastereo-, and regioselective iridium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of acyclic β-ketoesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17298–17301. doi: 10.1021/ja4097829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu W-B, Reeves CM, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM. Construction of vicinal tertiary and all-carbon quaternary stereocenters via Ir-catalyzed regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective allylic alkylation and applications in sequential Pd catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10626–10629. doi: 10.1021/ja4052075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krautwald S, Sarlah D, Schafroth MA, Carreira EM. Enantio- and diastereodivergent dual catalysis: α-allylation of branched aldehydes. Science. 2013;340:1065–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1237068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krautwald S, Schafroth MA, Sarlah D, Carreira EM. Stereodivergent α-allylation of linear aldehydes with dual iridium and amine catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3020–3023. doi: 10.1021/ja5003247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandmeier T, Krautwald S, Zipfel HF, Carreira EM. Stereodivergent dual catalytic α-allylation of protected α-amino- and α-hydroxyacetaldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:14363–14367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naesborg L, Halskov KS, Tur F, Mønsted SMN, Jørgensen KA. Asymmetric γ-allylation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes by combined organocatalysis and transition-metal catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:10193–10197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huo X, He R, Zhang X, Zhang W. An Ir/Zn dual catalysis for enantio- and diastereodivergent α-allylation of α-hydroxyketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:11093–11096. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Beiger JJ, Hartwig JF. Stereodivergent allylic substitutions with aryl acetic acid esters by synergistic iridium and lewis base catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:87–90. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He R, Liu P, Huo X, Zhang W. Ir/Zn dual catalysis: enantioselective and diastereodivergent α-allylation of unprotected α-hydroxy indanones. Org. Lett. 2017;19:5513–5516. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huo X, Zhang J, Fu J, He R, Zhang W. Ir/Cu dual catalysis: enantio- and diastereodivergent access to α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids bearing vicinal stereocenters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:2080–2084. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang X, Boehm P, Hartwig JF. Stereodivergent allylation of azaaryl acetamides and acetates by synergistic iridium and copper catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1239–1242. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Z-T, Jiang X, Hartwig JF. Stereodivergent construction of tertiary fluorides in vicinal stereogenic pairs by allylic substitution with iridium and copper catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13066–13073. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b04440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, et al. Stereodivergent coupling of 1,3-Dienes with aldimine esters enabled by synergistic Pd and Cu catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He R, et al. Stereodivergent Pd/Cu catalysis for the dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformation of racemic unsymmetrical 1,3-Disubstituted allyl acetates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:8097–8103. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c02150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H-M, et al. Stereodivergent synthesis of α-quaternary serine and cysteine derivatives containing two contiguous stereogenic centers via synergistic Cu/Ir catalysis. Org. Lett. 2020;22:4852–4857. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, et al. Data-driven catalyst optimization for stereodivergent asymmetric synthesis of α-allyl carboxylic acids by iridium/boron hybrid catalysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021;2:100679. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrp.2021.100679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Y, Huo X, Luo Y, Wu L, Zhang W. Enantio- and diastereodivergent synthesis of spirocycles through dual-metal-catalyzed [3+2] annulation of 2-vinyloxyranes with nucleophilic dipoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:24941–24949. doi: 10.1002/anie.202111842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies CR, Luvaga IK, Ready JM. Enantioselective allylation of alkenyl boronates promotes a 1,2-metalate rearrangement with 1,3-diastereocontrol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:4921–4927. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c01242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huo X, et al. Stereodivergent Pd/Cu catalysis for asymmetric desymmetric alkylation of allylic geminal dicarboxylates. CCS Chem. 2022;4:1720–1731. doi: 10.31635/ccschem.021.202101044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y, et al. Stereodivergent total synthesis of rocaglaol initiated by synergistic dual-metal-catalyzed asymmetric allylation of benzofuran-3[2H]-one. Chem. 2022;8:2011–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka S, Kitamura M. Asymmetric dehydrative allylation using soft ruthenium and hard brønsted acid combined catalyst. Chem. Rec. 2021;21:1385–1397. doi: 10.1002/tcr.202000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyata K, Kutsuna H, Kawakami S, Kitamura M. A chiral bidentate sp2-N Ligand, Naph-diPIM: Application to CpRu-catalyzed asymmetric dehydrative C-, N-, and O-allylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:4649–4653. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki Y, Vatmurge N, Tanaka S, Kitamura M. Enantio- and diastereoselective dehydrative “one-step” construction of spirocarbocycles via a Ru/H+-Catalyzed Tsuji–Trost approach. Chem. Asian J. 2017;12:633–637. doi: 10.1002/asia.201700013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamashima Y, Yagi K, Takano H, Tamás L, Sodeoka M. An efficient enantioselective fluorination of various β-ketoesters catalyzed by chiral palladium complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14530–14531. doi: 10.1021/ja028464f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamashima Y, Hotta D, Sodeoka M. Direct generation of nucleophilic chiral palladium enolate from 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds: catalytic enantioselective michael reaction with enones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11240–11241. doi: 10.1021/ja027075i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayamizu K, Terayama N, Hashizume D, Dodo K, Sodeoka M. Unique features of chiral palladium enolates derived from β-ketoamide: structure and catalytic asymmetric michael and fluorination reactions. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:6594–6601. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2015.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamashima, Y., Tamura, T., Suzuki, S. & Sodeoka, M. Enantioselective protonation in the Aza-Michael reaction using a combination of chiral Pd-μ-Hydroxo complex with an amine salt. Synlett 1631–1634 (2009).

- 43.Hamashima Y, Suzuki S, Tamura T, Somei H, Sodeoka M. Scope and mechanism of tandem Aza-Michael reaction/enantioselective protonation using a Pd-μ-Hydroxo complex under mild conditions buffered with amine salts. Chem. Asian J. 2011;6:658–668. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakata T, Oishi T. Stereoselective reduction of β-keto esters with zinc borohydride. stereoselective synthesis of erythro-3-hydroxy-2-alkylpropionates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:1641–1644. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)77774-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danishefsky S, Lee JY. Total synthesis of (±)-pancratistatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4829–4837. doi: 10.1021/ja00195a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hudlicky T, et al. Toluene dioxygenase-mediated cis-dihydroxylation of aromatics in enantioselective synthesis. asymmetric total syntheses of pancratistatin and 7-deoxypancratistatin, promising antitumor agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10752–10765. doi: 10.1021/ja960596j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bingham TW, et al. Enantioselective synthesis of isocarbostyril alkaloids and analogs using catalytic dearomative functionalization of benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:657–670. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharpless KB, Michaelson RC. High stereo- and regioselectivities in the transition metal catalyzed epoxidations of olefinic alcohols by tert-butyl hydroperoxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:6136–6137. doi: 10.1021/ja00799a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharpless KB, Lauer RF. Mild procedure for the conversion of epoxides to allylic alcohols. First organoselenium reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2697–2699. doi: 10.1021/ja00789a055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu M, Zhang Q, Zi W. Diastereodivergent synthesis of β-amino alcohols through dual-metal-catalyzed coupling of alkoxyallenes with aldimine esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:6545–6552. doi: 10.1002/anie.202014510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Zhang R, Zhang Q, Zi W. Synergistic Pd/Amine-catalyzed stereodivergent hydroalkylation of 1,3-dienes with aldehydes: reaction development, mechanism, and stereochemical origins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:10948–10962. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c02220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chai W, Guo B, Zhang Q, Zi W. Cooperative Pd/Cu-catalyzed diastereodivergent coupling of allenamides and aldimine esters to access the Mannich-type motifs. Chem. Catal. 2022;2:1428–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.checat.2022.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu, M., Wang, P., Zhang, Q., Tang, W. & Zi, W. Diastereodivergent aldol-type coupling of alkoxyallenes with pentafluorophenyl esters enabled by synergistic palladium/chiral Lewis base catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. accepted (10.1002/anie.202207621). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All crystallographic data generated in this study have been deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) database under accession code 2193030 ((R,S)-syn-3aa), 2193039 ((R,R)-anti-3aa), 2193045 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11aa), 2193050 ((1R,2R,3R)-syn1,2anti2,3-11aa), 2193051 ((1S,2R,3R)-anti1,2anti2,3-11aa), 2193052 ((2R,3S)-syn-11ba), 2193053 ((R,S)-syn-3ia), 2193054 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ab), 2193059 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ae), 2193062 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11ah), 2193063 ((1R,2R,3S)-syn1,2syn2,3-11am), 2193064 ((R,S)-syn-3ao), and 2193066 (8). For compound numbers, see Supplementary Information. All other data relating to the findings of this study, NMR spectrum, and HPLC charts are provided in the Supplementary Information.