Abstract

Background

An estimated 47 million people have dementia globally, and around 10 million new cases are diagnosed each year. Many lifestyle factors have been linked to cognitive impairment; one emerging modifiable lifestyle factor is sedentary time.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of peer-reviewed literature examining the association between total sedentary time with cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults under the moderating conditions of (a) type of sedentary time measurement; (b) the cognitive domain being assessed; (c) looking at sedentary time using categorical variables (i.e., high versus low sedentary time); and (d) the pattern of sedentary time accumulation (e.g., longer versus shorter bouts). We also aimed to examine the prevalence of sedentary time in healthy versus cognitively impaired populations and to explore how experimental studies reducing or breaking up sedentary time affect cognitive function. Lastly, we aimed to conduct a quantitative pooled analysis of all individual studies through meta-analysis procedures to derive conclusions about these relationships.

Methods

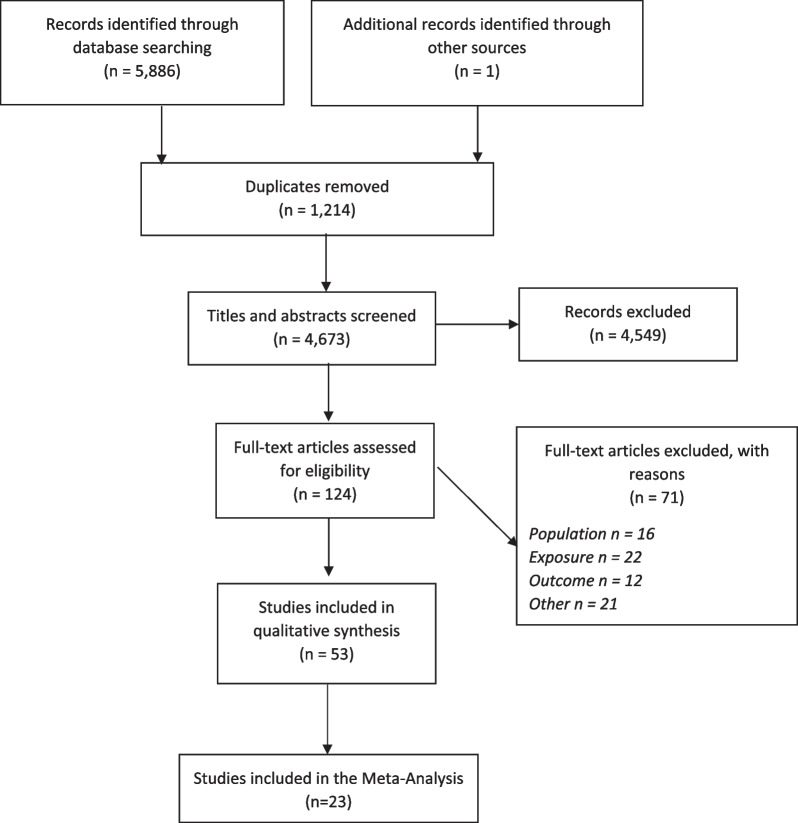

Eight electronic databases (EMBASE; Web of Science; PsycINFO; CINAHL; SciELO; SPORTDiscus; PubMed; and Scopus) were searched from inception to February 2021. Our search included terms related to the exposure (i.e., sedentary time), the population (i.e., middle-aged and older adults), and the outcome of interest (i.e., cognitive function). PICOS framework used middle-aged and older adults where there was an intervention or exposure of any sedentary time compared to any or no comparison, where cognitive function and/or cognitive impairment was measured, and all types of quantitative, empirical, observational data published in any year were included that were published in English. Risk of bias was assessed using QualSyst.

Results

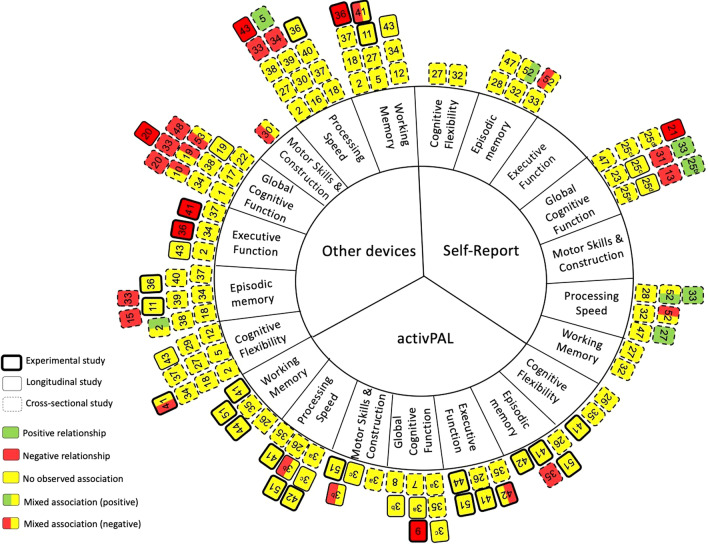

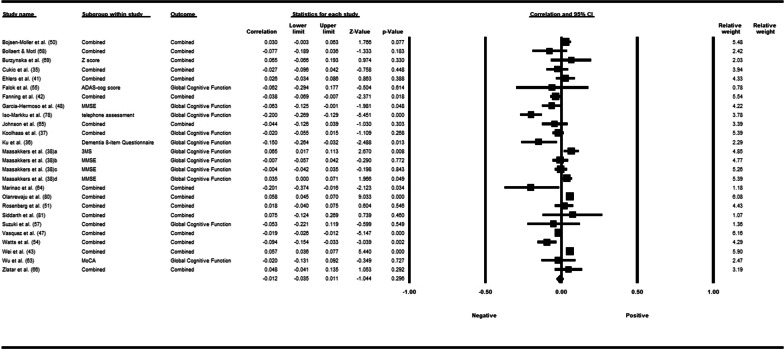

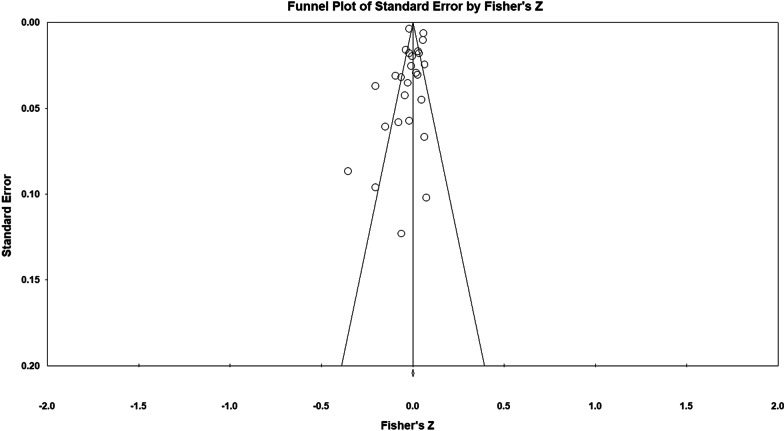

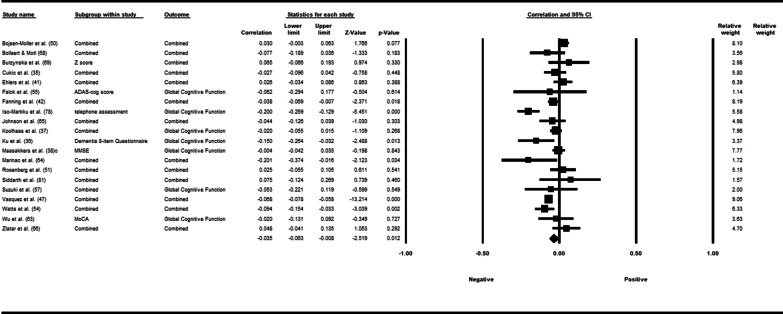

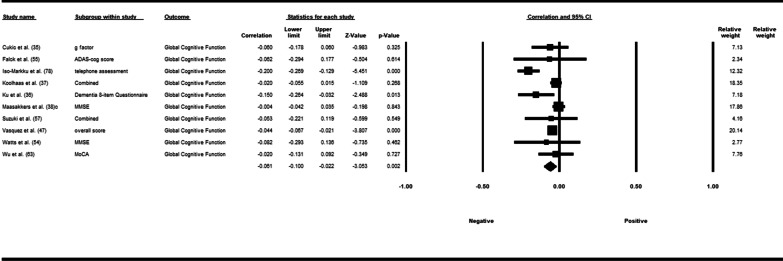

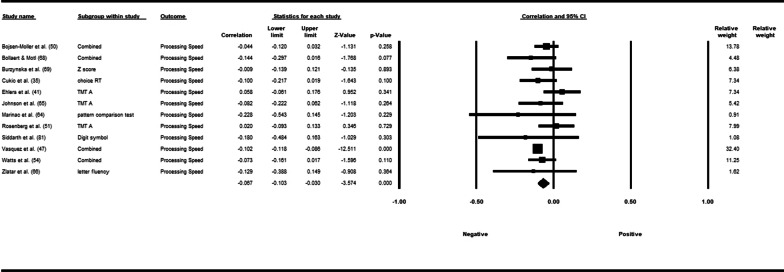

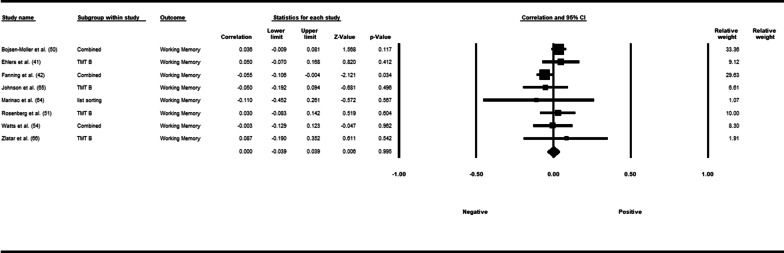

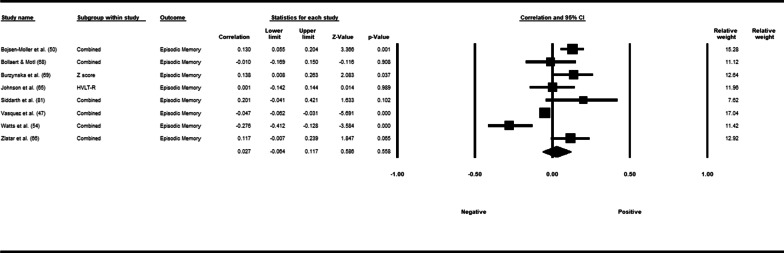

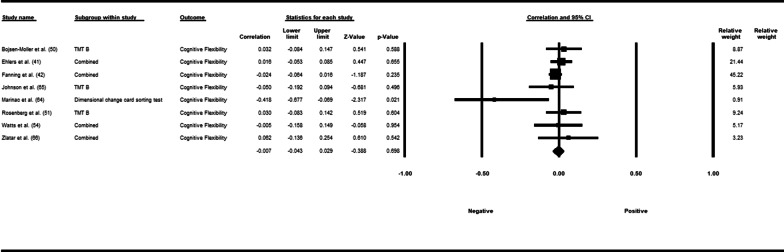

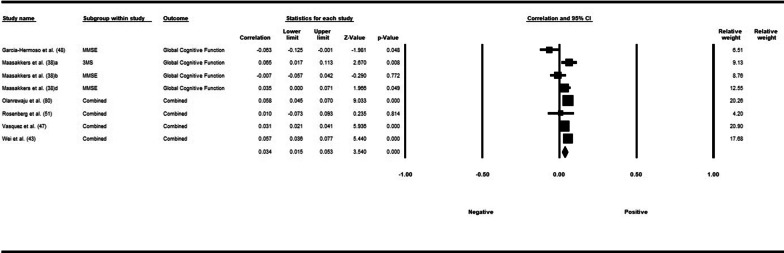

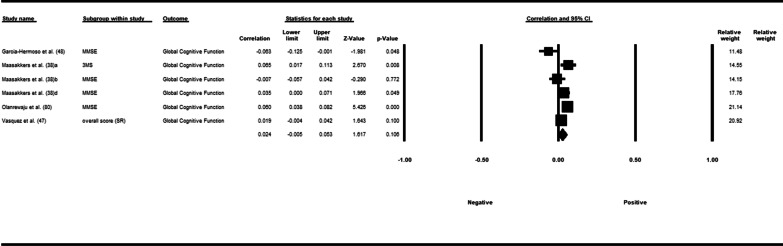

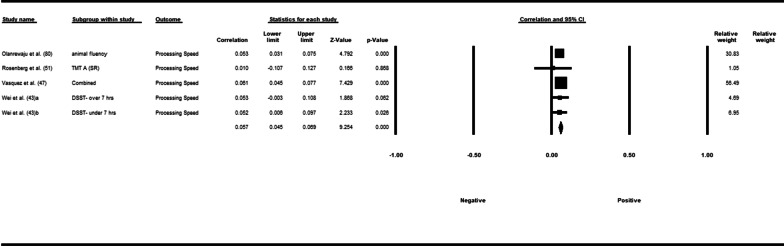

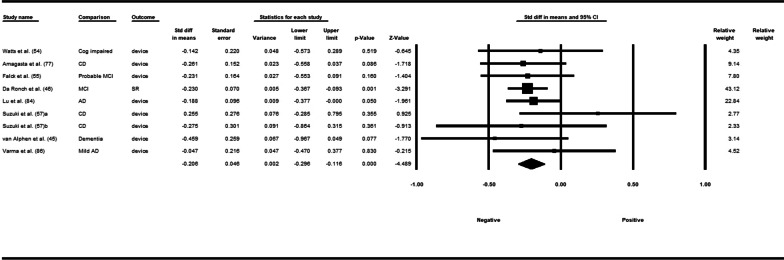

Fifty-three studies including 83,137 participants met the inclusion criteria of which 23 studies had appropriate data for inclusion in the main meta-analysis. The overall meta-analysis suggested that total sedentary time has no association with cognitive function (r = −0.012 [95% CI − 0.035, 0.011], p = 0.296) with marked heterogeneity (I2 = 89%). Subgroup analyses demonstrated a significant negative association for studies using a device to capture sedentary time r = −0.035 [95% CI − 0.063, − 0.008], p = 0.012). Specifically, the domains of global cognitive function (r = −0.061 [95% CI − 0.100, − 0.022], p = 0.002) and processing speed (r = −0.067, [95% CI − 0.103, − 0.030], p < 0.001). A significant positive association was found for studies using self-report (r = 0.037 [95% CI − 0.019, 0.054], p < 0.001). Specifically, the domain of processing speed showed a significant positive association (r = 0.057 [95% CI 0.045, 0.069], p < 0.001). For prevalence, populations diagnosed with cognitive impairment spent significantly more time sedentary compared to populations with no known cognitive impairments (standard difference in mean = −0.219 [95% CI − 0.310, − 0.128], p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The association of total sedentary time with cognitive function is weak and varies based on measurement of sedentary time and domain being assessed. Future research is needed to better categorize domains of sedentary behaviour with both a validated self-report and device-based measure in order to improve the strength of this relationship. PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018082384.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40798-022-00507-x.

Keywords: Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Middle-aged, Older adults, Sedentary behaviour, Cognition, Cognitive decline

Key Points

The association of total sedentary time with cognitive function varies based on the method of sedentary time measurement and the cognitive domain being assessed

Populations that have been diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or dementia spend significantly more time sedentary compared to cognitively healthy populations.

Future research is needed to investigate associations of individual sedentary behaviours with cognitive function and examine the impact of cognitive load on this association.

Introduction

Cognitive function refers to multiple mental abilities including learning, thinking, reasoning, remembering, problem solving, decision making and attention [1]. Dementia can be defined simply as a significant loss of cognitive function that impacts functions of daily living [2]. An estimated 47 million people have dementia globally and around 10 million new cases are diagnosed each year [3]. Unfortunately, this number will continue to rise at an exponential rate due to a global increase in the number of people living to older age [4]. Dementia has a major impact on the individual, but also has detrimental physical, emotional, psychological, social, and economic effects on caregivers, families, and society as a whole [5]. It is estimated that the total global societal cost of dementia is US$818 billion per year (1.1% of global gross domestic product); making it a public health priority [6, 7].

With the absence of a pharmacological treatment for the disease, current medications can only modestly alleviate symptoms [8]. Thus, other strategies (i.e., lifestyle modifications) are imperative for addressing the forthcoming dementia pandemic. Although cognitive decline tends to materialize later on in life, it is experienced by every individual at different severities and rates [1]. The latest Lancet review published in 2020 on dementia prevention, intervention and care concluded that 40% of worldwide dementia cases can be attributed to 12 modifiable risk factors [9], which is three more risk factors than the original review published in 2017 [10]. While we know a lot about some risk factors, there may be other unexplored factors, for example, targeting the reduction of sedentary time and how it may impact cognitive function. Despite the well-known benefits of moderate to vigorous physical activity, only 15% of adults aged 65–79 achieve at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week [11] and in addition, spend an average of 10.1 h/day being sedentary [12].

The associations between sedentary time and non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, some forms of cancers, as well as all-cause mortality are now well established [13]. Sedentary behaviour is defined as any waking behaviour in a seated or lying posture while expending less than or equal to 1.5 metabolic equivalents of energy [14]. The evidence on the health risks associated with too much sitting is now informing public health guidelines. For example the Canadian 24-h movement guidelines recommend that in addition to accumulating 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week, people should keep prolonged sitting time to a minimum, advising no more than eight hours of sitting per day [15].

Sedentary time has become a known modifiable determinant of health and an important predictor of healthy aging [16–19]. More recently, studies have emerged suggesting that higher levels of sedentary time may also be linked to lower levels of cognitive function and an increased risk of cognitive decline [20–22]. Previous reviews have investigated the relationship between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function [23–26]. From these reviews, we know that the relationship is inconsistent, and observed relationships are rather weak. More specifically, Falck et al. (2016) suggested higher levels of sedentary behaviour were associated with lower cognitive performance [24]. This was concluded from eight observational studies including adults 40 years and over. A later review by Copeland and colleagues (2017) investigated the relationship in adults 60 years and older [23]. They were able to include 14 studies, including five studies featured in Falck’s 2016 review [24]. Of these, only half reported finding associations between increased sedentary behaviour and decreased cognitive function and the results were not differentiated according to the exposure and outcome measures used (i.e., self-report versus device or specific cognitive domains). The review by Loprinzi (2019) included humans of all ages and focused specifically on memory, including 25 studies [25]. Loprinzi observed a conflicting association of sedentary behaviour with cognitive function. Results from the most recent review are not much clearer. Olanrewaju et al. (2020) also found varied and inconclusive evidence on the relationship between the two variables [26]. The main difference of this review from the preceding ones was that it excluded studies involving participants diagnosed with dementia. Out of the 18 studies included, seven of these studies reported associations between increased sedentary behaviour time and decreased cognitive function. Only four of the 18 studies were consistent with those included in the Copeland (2017) review [23]. Despite including 18 studies, there were no interventions identified; and there was too much heterogeneity to perform a meta-analysis. The current systematic review builds on these previous ones, addressing specific conceptual and methodological issues that these reviews could not avoid due to the nature of the literature at that time.

Although the definition of sedentary behaviour was properly defined in previous reviews, the large-scale heterogeneity found within the available studies at the time could stem from the broadly defined study exposure (i.e., sedentary behaviour) needed in order to synthesize the current state of the literature. In other words, a specific domain of sedentary behaviour (i.e., television viewing) needed to be synthesized alongside studies measuring total sedentary time. This is problematic as we know that television viewing is a poor proxy of overall sedentary time [27]. Thus, no reviews have specifically aimed to review the association of total sedentary time with cognitive function. Secondly, the inconsistent and weak relationships between sedentary behaviour and cognitive function reported in previous reviews suggests that this relationship needs to be examined under certain moderator conditions. None of the reviews examined the association between studies that have used self-reported measures versus those that have used a device (i.e., activPAL™). This is an important moderator to investigate as self-report has been shown to underestimate sedentary time when compared to device-based measurements [23]. Although touched upon in the review by Falck (2016), another moderator that warrants attention is which specific domains of cognition are most affected by total sedentary time. Insight here will assist researchers’ focus on cognitions that are more salient to total sitting time. Third, no previous reviews have interpreted the findings based on a threshold or cut-off that compares two categorical groups (i.e., high versus low sedentary time) as opposed to comparing the relationship using continuous variables. It is unknown whether this relationship will be more concrete if more extreme groups or categorical groups are used; this may have implications for how researchers collect and analyze total sitting time data. Fourth, no previous review has interpreted the associations based on how sedentary time was accumulated throughout the day (i.e., short, frequent bouts vs. longer uninterrupted bouts). Recent investigations have highlighted the negative aspects of accumulating prolonged bouts of sedentary time regardless of meeting physical activity guidelines [17]. Thus, it is recommended to incorporate short bouts of activity to break up sedentary periods throughout the day [28]. Fifth, no previous reviews have synthesized the findings based on the prevalence of sedentary time in populations diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or dementia versus populations deemed as cognitively healthy. Since the older adult population is the most sedentary and inactive population, it makes it hard to tease out a bidirectional relationship (i.e., is more sitting causing cognitive decline or is cognitive decline resulting in more sitting?). Therefore, differentiating populations that may be more susceptible to increased amounts of sitting, (i.e., people with cognitive impairment, transitioning into retirement, etc.) could help tease out any mixed association. This also highlights the importance of including both middle-aged and older adults. Sixth, experimental studies were scarce at the time of these previous reviews, but with the growing interest in this relationship, synthesizing any experimental studies aiming to reduce or break up sedentary time is important as it could illustrate whether we are able to manipulate cognitive function with sitting time. Seventh and finally, due to the heterogeneity of the literature at the time of these previous reviews, they were not able to perform a meta-analysis to quantify the effect size of the relationship. Since these reviews, there have been many more studies published on the relationship of sedentary behaviour with cognitive function, which allows this review to have a narrower view of the exposure variable, sedentary time, alongside being able to evaluate the relationship with the aforementioned moderators.

Addressing the abovementioned issues, the overarching objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review to explore the relationship of total sedentary behaviour time with cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults. A specific objective was to examine the relationship under the following moderator conditions: a) self-reported versus device based sedentary time measurement; b) the cognitive domain being assessed (e.g., working memory, processing speed, etc.); c) looking at sedentary time using categorical variables (i.e., high versus low sedentary time) and d) the pattern of sedentary time accumulation (e.g., longer versus shorter bouts). We also aimed to examine the prevalence of sedentary time in healthy versus cognitively impaired populations. Additionally, we aimed to explore how experimental studies reducing or breaking up sedentary time affects cognitive function. Lastly, we aimed to conduct a quantitative pooled analysis of all individual studies through meta-analysis procedures to derive conclusions about these relationships. In doing so, we intended to determine whether the aforementioned variables on their own, or in conjunction with one another served to change the strength and/or direction of relationships between total sedentary time and cognitive function.

Methods

The protocol for this review is registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42018082384). The review and meta-analysis were also completed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA). This paper was also conducted in accordance with the PRISMA in Exercise, Rehabilitation, Sports Medicine, and Sports Science guidelines (PERSIST).

Search Strategy

We searched the following electronic databases from inception to February 13th, 2021: Excerpta Medica (EMBASE); Web of Science; PsycINFO; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO); SPORTDiscus; PubMed; and Scopus. The databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free text terms. The review authors along with librarians at The University of Queensland and Western University developed the search strategy. The search included terms related to the exposure (i.e., sedentary behaviour), the population (i.e., middle-aged and older adults), and the outcome of interest (i.e., cognitive function) (See Additional file 1 for an example search strategy for Scopus). All database searches were appropriately revised to suit the specific database. Where the database software had the function, we used "forward" citation searches (showing the sources that cite these articles) on the studies we included in this systematic review. Additionally, reference lists of all relevant reviews on cognitive outcomes and sedentary behaviour from the last 10 years were hand-searched. These reviews were identified in the initial title and abstract screening and through a search of our key terms in Cochrane. All additional articles identified through these other sources were subject to the same eligibility criteria and screening process as those found through the electronic database searches.

Selection Criteria

Types of Participants

The focus of this review was middle-aged and older adults. Therefore, we included studies where the mean age of the population was aged 40 or over [29]. Studies from any country were included. If the data set had been used more than once, the publication most relevant and appropriate for the current review was included.

Types of Interventions/Exposure

This review examined studies where the intervention or exposure was sedentary behaviour, as defined by each individual study. The definition of sedentary behaviour is sitting or lying behaviours during waking time that expend low levels of energy (≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents) [14]. Studies were included if they reported the total time spent ‘sedentary’ per day or week, or if they reported the percentage of daily waking hours in ‘sedentary behaviour’ per day or week. Thus, any reference to ‘sedentary time’ in the current review can be interpreted as ‘total’ or all-encompassing sedentary time unless stated otherwise. Studies were excluded if they defined and/or measured sedentary behaviour as a lack of physical activity, included sleep time in the reported sedentary behaviour time, only measured leisure sedentary time, or only measured a specific domain of sedentary behaviour. Studies were also excluded if they were a multicomponent lifestyle intervention where sedentary behaviour was only one component of the intervention. In other words, if sedentary behaviour was only a ‘control’ condition of the intervention, it was excluded. Studies specifically investigating bedrest or designed for cognitive rehabilitation or training were excluded.

Types of Comparison

Studies with any comparators or no comparators were eligible for inclusion.

Types of Outcome Measures

Studies measuring cognitive function and/or cognitive impairment/decline (i.e., dementia or mild cognitive impairment [MCI]) using a recognised method or measure were included. Cognitive outcomes from each study were tabulated and categorized based on the authors’ classification of which domain the task measured (i.e., processing speed, episodic memory, etc.). If the task was used in more than one study and the authors reported different domains, discrepancies were solved by the current study’s authors using guidance from an article which reviewed the general structures of cognitive domains, along with assessment strategies for differentiating them [30]. The various outcomes of cognitive function from each study were grouped into one or more of the following domains: (1) processing speed; (2) episodic memory; (3) global cognitive function; (4) motor skills and construction; (5) executive function; (6) cognitive flexibility and (7) working memory. The definition and acceptable cognitive tests for each domain are described in Additional file 2. Studies that measured cognitive function as defined by brain volume or cerebral blood flow using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Positron Emission Tomography (PET) were excluded.

Types of Studies

Quantitative empirical studies published in any year were included, including observational (cross-sectional and/or longitudinal) and intervention/experimental studies. Discussion articles, conference proceedings, book chapters, theses or commentaries not presenting empirical research in a peer-reviewed journal were excluded. Studies published in a language other than English were also excluded.

Selection of Studies

Titles and abstracts of the identified studies were independently checked by two review authors using Covidence systematic review software and those that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Full texts were then also reviewed by two authors. At both stages of the screening process, the authors discussed any discrepancies in their initial judgements and reached a consensus.

Data Extraction

Data from each of the included studies were extracted independently by one review author and checked by a second author for accuracy. The following data from each of the included studies were extracted and can be found in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4: (1) author name and year; (2) study design; (3) participant characteristics (country, number of participants in each group, mean age, percent of female participants, and sedentary time reported; (4) measure of exposure (i.e., sedentary behaviour); (5) measure of outcome (i.e., cognitive function); (6) covariates used in the least and fully adjusted models (if applicable) and (7) main findings/numerical results for each outcome of interest (i.e., correlation coefficients, mean [SD], effect sizes, p values, etc.). Additional information that was extracted, but not reported within Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 consisted of: (1) study objectives; (2) source of recruitment/method; (3) inclusion/exclusion criteria; (4) number of groups and method of group allocation (if application); (5) type of data (i.e., binary or continuous) for both exposure and outcome variables; (6) time frame of intervention/observation; (7) statistical methodology (i.e., subgroup analysis, intention to treat, etc.); (8) conclusion; (9) limitations identified by the authors and 10) any declared conflict of interest. If any study reports were incomplete or if data were missing, corresponding study authors were contacted via email.

Table 1.

Summary and characteristics of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies reporting an association of sedentary behaviour with cognitive function

| Authors (year) Country Study design Pinwheel number |

Participants Mean age (Mage) % F (female) SB time (min) |

Device or self-report (measure of sedentary behaviour) | Domain (outcome measure) | Covariates adjusted for | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amagasta et al. (2020) [77] Japan CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = 1 |

Cognitive decline n = 48, Mage = 77.6 (5.4), %F = 52, SB time = 476 Non-cognitive decline n = 463, Mage = 73.0 (5.4), %F = 53, SB time = 442 Population: mixed |

Device (Active style Pro HJA-750C) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) ≤ 23 = Cognitive Function Decline |

Model 1: unadjusted Model 4: Gender, age, education, BMI, living arrangements, working status, smoking, alcohol use, past history of stroke, medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes |

SB relative to other behaviours: OR 1.06; 95% CI [0.42, 2.72] SB and cognitive function: Model 1: OR 1.30 [0.63, 2.70] Model 4: OR 0.96 [0.38, 2.39] |

|

Bollaert et al. (2019) [68] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 39 |

Healthy group n = 40, Mage = 66.5 (6.7), %F = 63, SB time = 534 Multiple Sclerosis group n = 40, Mage = 65.3 (4.3), %F = 63, SB time = 540 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Processing Speed (PASAT) Episodic Memory (CVLT-II) |

Not stated |

Total SB Healthy Controls (r) SDMT: − 0.38 CVLT-II: − 0.13 BVMT-R: − 0.03 PASAT: − 0.11 MS Group (r) SDMT: − 0.15 CVLT-II: 0.20 BVMT-R: − 0.08 PASAT: 0.08 |

|

Bojsen-Moller et al. (2019) [50] Sweden CS Study number in pinwheel = 2 |

n = 334, Mage = 42.4 (9.1), %F = 68, SB time = 565 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph GT3X) |

Processing Speed (TMT A, Digit Symbol) Working Memory (DSB, N-back (2-back), AOS, TMT B) Episodic Memory (Free Recall, Word Recognition) Executive Function (Stroop) Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B) |

Model 2: age, gender, education, % of daytime in sedentary behaviour Model 4: age, gender, education, % of daytime in sedentary behaviour and VO2max |

SB and cognitive outcomes: β, [95% CI] Model 2 Digit symbol: 0.004 [− 0.145, 0.138] Free recall: 0.125 [− 0.011, 0.266], p < 0.05 Digit span backwards: 0.003 [− 0.139, 0.146] 2-back (accuracy): − 0.022 [− 0.165, 0.120] 2-back (reaction time): − 0.053 [− 0.195, 0.087] Word recognition: 0.035 [− 0.107, 0.177] AOS (recalled sets): − 0.011 [− 0.159, 0.136] AOS (accuracy): − 0.022 [− 0.165, 0.120] Stroop: 0.012 [− 0.131, 0.155] TMT A: 0.042 [− 0.103, 0.190] TMT B: − 0.032 [− 0.194, 0.126] Model 4 Digit symbol: − 0.047 [− 0.219, 0.126] Free recall: 0.136 [− 0.003, 0.280], p < 0.05 Digit span backwards: − 0.003 [− 0.149, 0.142] 2-back (accuracy): 0.060 [− 0.085, 0.207] 2-back (reaction time): − 0.052 [− 0.198, 0.092] Word recognition: 0.071 [− 0.071, 0.215] AOS (recalled sets): 0.010 [− 0.140, 0.161] AOS (accuracy): − 0.006 [− 0.152, 0.140] Stroop: − 0.016 [− 0.162, 0.129] TMT A: 0.04 [− 0.108, 0.191] TMT B: − 0.044 [− 0.210, 0.118] |

|

Burzynska et al. (2020) [69] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 40 |

n = 228, Mage = 65.3 (4.5) %F = 68, SB time = 537 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (DS, Digit Symbol, Pattern comparison, letter comparison) Episodic Memory (Word recall, Logical memory, Paired associates) |

Model 1: age, sex, education, adult education, light, and moderate to vigorous PA |

β (SE) Processing speed: − 0.009 (0.001) p = 0.900 Episodic Memory: β = 0.088 (0.001) p = 0.245 |

|

Cukic et al. (2018) [35] Scotland CS/LO Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 3a,b,c |

LBC1936 cohort n = 271, Mage = 79.0 (0.4) % F = 48, SB time = 627 Population: non-clinical 3a |

Device (activPal3) |

Global Cognitive Function (general cognitive ability factor (g) computed from 6 tests taken from the WAIS (Matrix Reasoning, Block Design, Letter-Number Sequencing, Symbol Search, DSB, and Digit Symbol), Moray Houst Test No. 12 (MHT), Alice Heim 4 test (AH4)) Processing Speed (Four-choice RT) Motor Skills and Construction (Simple RT) |

Model 1: age and sex Model 3: age, sex, education, long standing illness |

Cog ability & total SB: β, [95% CI] Model 1 g-wave 4: − 0.06 [− 0.18, 0.06], p = 0.36 Simple RT: 0.03 [− 0.09, 0.15], p = 0.61 Choice RT: − 0.10 [− 0.22, 0.02], p = 0.09 MHT change age 11–79: − 0.09 [− 0.21, 0.03], p = 13 Model 3 g-factor: − 0.01 [− 0.15, 0.13], p = 0.9 Simple RT: 0.02 [− 0.1, 0.14], p = 0.77 Choice RT: − 0.12 [− 0.24, 1.0], p = 0.05 MHT change age 11–79: − 0.06 [− 0.20, 0.08], p = 0.34 |

|

Twenty-07 1950’s cohort n = 310, Mage = 64.6 (0.9), %F = 53.2, SB time (%) = 60.8 Population: non-clinical 3b |

Model 1: age and sex Model 4: age, sex, education, long standing illness, employment status |

Cog ability & total SB: β, [95% CI] Model 1 AH4 wave 5: − 0.08 [− 0.04, 0.20], p = 0.18 Simple RT wave 5: 0.12 [0.00, 0.24], p = 0.04 Choice RT wave 5: 0.09 [− 0.03, 0.21], p = 0.13 Model 4 AH4 wave 5: − 0.06 [− 0.20, 0.08], p = 0.39 Simple RT: 0.06 [− 0.06, 0.18], p = 0.26 Choice RT: 0.05 [− 0.07, 0.17], p = 0.41 |

|||

|

Twenty-07 1930’s cohort n = 119, Mage = 83.4 (0.6), %F = 55, SB time (%) = 68 Population: non-clinical 3c |

Model 1: age and sex Model 3: age, sex, education, long standing illness |

Cog ability & total SB: β, [95% CI] Model 1 AH4 wave 1: − 0.08 [− 0.28, 0.12], p = 0.41 AH4 wave 5: − 0.07 [− 0.27, 0.13], p = 0.49 Simple RT wave 5: 0.04 [− 0.14, 0.22], p = 0.70 Choice RT wave 5: 0.10 [− 0.14, 0.34], p = 0.42 Model 3 AH4 wave 1: − 0.08 [− 0.30, 0.14], p = 0.45 AH4 wave 5: − 0.04 [− 0.26, 0.18], p = 0.75 Simple RT wave 5: 0.02 [− 0.18, 0.22], p = 0.82 Choice RT wave 5: 0.10 [− 0.15, 0.35], p = 0.42 |

|||

|

Ehlers et al. (2018) [41] USA CS Isotemporal Study number in pinwheel = 5 |

n = 271, Mage = 57.8 (9.5), %F = 100, SB time = 600 Population: clinical |

Device (Actigraph) Isotemporal: Substituting 30 min of sedentary time with 30 min of light-intensity activity, MVPA, and sleep |

Processing Speed (TMT A) Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B, Task-switching) Working Memory (TMT B) |

Single effect: age, months of hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, total time Partition effect: age, months of hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, total time, other behaviours |

Total SB time and cognitive function B 95% CI Single effect Task switch-switch: 2.06 [− 7.07, 11.16] Task switch-stay: − 1.47 [− 9.62, 6.69] TMT A: − 0.97 [− 1.85, − 0.08], p < 0.05 TMT B: − 1.19 [− 2.41, 0.03] Partition effect Task switch-switch: − 8.76 [− 22.26, 4.76] Task switch-stay: − 5.94 [− 18.07, 6.18] TMT A: − 0.75 [− 2.05, 0.55] TMT B: − 0.92 [− 2.71, 0.87] Replacing 30 min of sedentary time with 30 min of MVPA yielded faster reaction times on Task-Switch stay (B = −29.37, p = 0.04) and switch (B = −39.49, p = 0.02) trials Replacing sedentary time with light-intensity activity was associated with slower Trails A (B = 1.55 p = 0.002) and Trails B (B = 1.69, p = 0.02) completion |

|

Ekblom et al. (2019) [90] Sweden CS Study number in pinwheel = 6 |

n = 216, age range = 54–66, %F = 56, SB time = 461 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Episodic Memory (Verbal Memory) Motor Skills and Construction (Rey Complex Figure) Processing Speed (SDMT, TMT A, Stroop 1) Cognitive Flexibility & Working Memory (TMT B) Executive Function (Stroop 2 & 3) |

age, gender, smoking, education, born outside Sweden |

SB and cognitive function (β) verbal memory (verbatim): 0.136, p < 0.05 verbal memory (direct Syn): 0.137, p < 0.05 verbal memory (delayed Verbatim): 0.119, p < 0.1 verbal memory (delayed Syn): 0.134, p < 0.1 Stroop 1: not significant Stroop 2: − 0.141, p < 0.05 Stroop 3: − 0.137, p < 0.01 SDMT: 0.126, p < 0.01 TMT A: not significant TMT B: − 0.113, p < 0.01 RCF 1: 0.109, p = 0.139 RCF 2: 0.071, p = 0.342 RCF 3: − 0.027, p = 0.717 |

|

English et al. (2016) [74] Australia CS Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 7 |

n = 50, Mage = 67.2 (11.6), % F = 34, SB = nr Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | waking hours |

MoCA with total sitting time r = 0.153, p = 0.3 |

|

Ezeugwu et al. (2017) [70] Canada CS Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 8 |

n = 30, Mage = 63.8 (12.3), %F = 43, SB time = 674 Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | Not reported |

SB time and MoCA r = −0.08, p > 0.05 |

|

Falck et al. (2017) [55] Canada CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 10 |

Probable MCI n = 81, Mage = 72.5 (7.6), %F = 60, SB time = 595 Without MCI n = 69, Mage = 69.4 (6.4), %F = 78, SB time = 542 Population: mixed |

Device (MotionWatch8) |

Global Cognitive Function (MoCA, ADAS-Cog Plus) Probable MCI = MoCA < 26 |

Age, sex, education |

SB and ADAS-Cog Plus (β) % Sedentary time: 0.007, p = 0.089 Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.061, p = 0.016 SB and ADAS-Cog Plus Based on MCI Status (β) non-MCI % Sedentary time: 0.012, p = 0.038 Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.075, p = 0.064 MCI % Sedentary time: < 0.001, p = 0.948 Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.033, p = 0.282 |

|

Fanning et al. (2017) [42] USA CS Isotemporal Study number in pinwheel = 12 |

n = 247, Mage = 65.4 (4.6), %F = 68, SB time = 534 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph) Isotemporal: Substituting 30 min of sedentary behavior with 30 min of light activity, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), or sleep |

Working Memory (computer-based task) Cognitive Flexibility (Task-switching) |

Age, gender, race |

SB and Working memory 2-item accuracy r = −0.106, p = 0.133 3-item accuracy r = −0.040, p = 0.575 4-item accuracy r = −0.081, p = 0.249 2-item reaction time r = 0.052, p = 0.460 3-item reaction time r = 0.013, p = 0.851 4-item reaction time r = 0.040, p = 0.566 SB and Cognitive Flexibility Single avg accuracy: r = −0.061, p = 0.391 Mixed repeat avg acc: r = 0.045, p = 0.532 Mixed switch avg acc: r = 0.006, p = 0.933 Global switch cost acc: r = −0.086, p = 0.228 Local switch cost acc: r = 0.084, p = 0.240 Single avg RT: r = 0.019, p = 0.794 Mixed repeat avg RT: r = 0.067, p = 0.352 Mixed switch avg RT: r = 0.070, p = 0.329 Global switch cost RT: r = 0.046, p = 0.525 Local switch cost RT: r = 0.026, p = 0.712 Substitution of sedentary time with MVPA was associated with higher accuracy on 2-item (B = .03, p = .01) and 3-item (B = .02, p = .04) working memory tasks, and with faster reaction times on single (B = −23.12, p = .03) and mixed-repeated task-switching blocks (B = −27.06, p = .04) Substitution of sedentary time with sleep was associated with marginally faster reaction time on mixed-repeated task-switching blocks (B = −12.20, p = .07) and faster reaction time on mixed-switch blocks (B = 17.21, p = .05), as well as reduced global reaction time switch cost (B = −16.86, p = .01) |

|

García-Hermoso et al. (2018) [48] Chile CS Study number in pinwheel = 13 |

n = 989, Mage = 74.1 (7.0), %F = 61, SB time = 225 Population: mixed |

Self-report (Global Physical Activity Questionnaire) |

Global Cognitive Function (modified-MMSE) ≤ 13 or less considered cognitively impaired |

Model 1: age, sex, education level, BMI, social characteristics (living alone), alcohol and drug use, tobacco intake, depression Model 2: age, sex, BMI, social characteristics (education level and living alone), alcohol and drug use, tobacco intake, depression, MVPA |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] 1.00, non-sedentary/active (ref group) 1.63 [0.92 to 4.75] non-sed/inactive, p = 0.084 1.91 [1.83 to 3.75] sed/active, p = 0.011 4.65 [2.50 to 6.31] sed/inactive, p < 0.001 SB and cognition Model 1: β = −0.063, p = < 0.001 Model 2: β = −0.046, p = < 0.05 |

|

Hayes et al. (2015) [61] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 15 |

n = 31, Mage = 64.5 (7.0), %F = 58, SB time = 565 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph) |

Episodic Memory (BVMT-Revised and the Faces subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition, verbal memory Z score, CVLT logical memory recall) Executive Function (TMT, VF from the Delis Kaplan Executive Function System, DSB and mental arithmetic from WAIS and the WCST) |

Age, gender, education, depression, hypertension, wear time |

SB and cognition Visuospatial memory test pr = −0.41, p < 0.05 face-name memory task pr = −0.53, p < 0.05 verbal memory: nr Executive Function: nr |

|

Hubbard et al. (2015) [79] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 16 |

n = 82, Mage = 49.0 (9.1), %F = 76, SB time = 582 Population: clinical |

Device (Actigraph) | Processing Speed (SDMT) | Not reported |

SB and cognition overall: r = −0.12, p = 0.29 mild: r = −0.14, p = 0.38 moderate: r = 0.06, p = 0.71 |

|

Iso-Markku et al. (2018) [78] Finland CS Study number in pinwheel = 17 |

n = 726, Mage = 72.9 (1.0), %F = 52, SB time = 537 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Hookie AM20) | Global Cognitive Function (Telephone assessment and interview for Cognitive Status (orientation, serial subtraction, word recall, semantics, sentence repetition, linguistic skills, and attention) |

Model 1: age, sex, accelerometer wear time, mean daily MET Model 2: age, sex, accelerometer wear time, BMI, living condition, years of education, mean daily MET |

Total cog score and SB Between-family analyses β (95% CI) Model 1: − 0.20 (− 0.41 to 0.01), p > 0.05 Model 2: − 0.21 (0.42 to − 0.003), p < 0.05 |

|

Johnson et al. (2016) [65] Australia CS Study number in pinwheel = 18 |

n = 188, Mage = 64.0 (7.3), %F = 54, SB time = 582 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (TMT A) Cognitive Flexibility & Working Memory (TMT B) Episodic Memory (HVLT-R) |

age, gender, level of education, waist to hip ratio, history of cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, HVLT total recall score (screening tool for MCI) |

SB and cognitive function TMT A: r = 0.082, p = ns TMT B: r = 0.050, p = ns HVLT: r = 0.001 p = ns |

|

Kojima et al. (2019) [40] Japan LO Study number in pinwheel = 43 |

n = 15, Mage = 78.0 (11.6), %F = 40 SB time = 1312 Population: clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (SDMT) Working Memory (Symbol Trails, Design Memory) Cognitive Flexibility (Symbol Trails, Symbol Cancellation) Executive Function (Symbol Cancellation, Mazes) |

Not stated |

4 months Value of sedentary behavior significantly decreased over four months (p < 0.05) Less sedentary behavior was significantly correlated with better SDMT scores (r = −0.355, p = 0.005) |

|

Koolhaas et al. (2019) [37] Netherlands CS/LO Study number in pinwheel = 19 |

n = 1841, Mage = 62.6 (9.3), %F = 54, SB time = 528 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (MMSE, g-factor test battery: MMSE, Stroop, letter-digit substitution task, VF15-word learning test, Purdue pegboard test) |

Model 1: age, sex, cohort, awake time Model 3: age, sex, cohort, awake time, education, occupational status, marital status, smoking, BMI, PA and disability score |

Cross-sectional β [95% CI] SB and g-factor Model 1: − 0.03 [− 0.05, − 0.01], p = 0.005 Model 3: − 0.01 [− 0.03, 0.01], p = 0.23 SB and MMSE Model 1: − 0.01 [− 0.06, 0.04], p = 0.66 Model 3: − 0.0004 [− 0.05, 0.05], p = 0.98 5.7-year follow-up g-factor: 0.18-point (SD: 0.51) decline MMSE score: 0.06-point decline (SD: 1.89) |

|

Ku et al. (2017) [36] Taiwan CS/LO Study number in pinwheel = 20 |

n = 274, Mage = 74.5 (6.1), %F = 54, SB time = categories Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (AD8) |

Model 1: baseline cognitive status, sex, age, and wear time of accelerometer Model 3: baseline cognitive status, sex, age, years of formal education, marital status, income source, smoking, number of comorbidities, depressive symptoms, wear time of accelerometer, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and activities of daily living |

SB time & cognitive ability (baseline) r = 0.15, p = < 0.05 SB time & cognitive ability (2-year follow-up) r = 0.21, p = < 0 .001 Adjusted rate ratio [95% CI] Model 1: 1.13 [1.04, 1.22), p = 0.002 Model 3: 1.10 [1.00, 1.19], p = 0.047 |

|

Lee et al. (2013) [39] Japan LO Study number in pinwheel = 21 |

n = 550, Mage = nr, %F = 48, SB time = nr Population: non-clinical |

Self-report (Trained interviewers asked subjects about time spent in physical activity for the past 12 months) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) Incidence and Odds of Significant cognitive decline (− 3 points on MMSE) |

Model 1: age, sex, educational level Model 3: age, sex, educational level, BMI, initial MMSE score, smoking status, self-rated health, Depression, sleep duration, whether participant was working, hypertension, myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, stroke, rheumatoid arthritis and MVPA |

Longitudinal (8-years) OR [95% CI] Model 1: 1.97, 95% [1.01, 3.86] Model 3: 3.03 [1.29, 7.14] |

|

Leung et al. (2017) [76] Canada CS Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 22 |

n = 114, Mage = 86.7 (7.5), %F = 85, SB = nr Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | Not reported |

% waking time in SB and MoCA: p > 0.05 |

|

Lopes et al. (2015) [82] Brazil CS Study number in pinwheel = 23 |

n = 2471, Mage = nr, %F = 60, SB time = categories Population: mixed |

Self-report (The International physical activity questionnaire) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) ≤ 25 = low cognitive performance (LCP) > 25 = high cognitive performance |

Not reported |

LCP prevalence [95% CI] 1st tertile (< 180 min/day): 38.20 [32.10, 44.69] 2nd tertile (> 180 < 308.61 min/day): 28.42 [22.70, 34.93] 3rd tertile (> 308.61 min/day): 29.34 [24.48, 34.72] LCP Prevalence ratio (PR) [95% CI] 2nd tertile [> 180 ≤ 308.61 min/day] Crude PR, 0.74 [0.60, 0.91] Adjusted PR, 0.73 [0.59, 0.89], p < 0.05 3rd tertile [> 380.61 min/day] Crude PR, 0.76 [0.62, 0.93] Adjusted PR, 0.75 (0.61–0.91), p < 0.05 |

|

Lu et al. (2018) [84] Hong Kong CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 24 |

Healthy: n = 271, Mage = 81.9 (3.5), %F = 38 Low MoCA: n = 252, Mage = 83.4 (4.0), %F = 48 MCI: n = 105, Mage = 83.6 (3.7), %F = 49 AD: n = 182, Mage = 80.8 (5.9), %F = 65 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (Hong Kong version of (MoCA) |

Model 1: age, gender, wear time Model 2: age, gender, wear time, years of education, BMI, unusual gait speed, living status, disease burden |

Time in SB (min/day): Controls = 546.7 Low MoCA = 534.1 MCI = 516.9 AD = 601.2 |

|

Maasakkers et al. (2020) [38] Australia, USA, Japan, and Singapore CS/LO Study number in pinwheel = 25a,b,c,d |

PATH Cohort n = 1552, Mage = 75.1 (1.5), %F = 49, SB time = 426 Population: non-clinical 25a |

Self-report (asked two questions relating to SB on a usual day, which distinguished between weekdays and weekend days) | Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) |

Unadjusted model: none Model 3: age, gender, education, income, alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, marital status, living status, perceived health, morbidities, blood pressure, sleep quality, depression and PA |

Cross-sectional Unadjusted B = −0.003 [− 0.005, 0.001], p = 0.79 Model 3 B = 0.001 [− 0.021, 0.022], p = 0.96 |

|

SALSA Cohort n = 1663, Mage = 70.2 (6.8), %F = 58, SB time = 276 Population: non-clinical 25b |

Self-report (administered three questions of SB related to sitting at work, at home, and while driving a car during a regular week) | Global Cognitive Function (3MS) |

Unadjusted model: none Model 2: age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, marital status, living status, perceived health, morbidities, blood pressure, sleep quality, depression and PA |

Cross-sectional (B) Unadjusted: 0.33 [0.027, 0.632], p = 0.03 Model 2: − 0.043 [− 0.317, 0.230], p = 0.76 Longitudinal (8.1-year follow-up) Unadjusted: 0.008 [− 0.038, 0.053], p = 0.74 Model 2: − 0.011 [− 0.058, 0.037], p = 0.66 |

|

|

SGS Cohort n = 2597, Mage = 73.4 (6.1), %F = 56, SB time = 444 Population: non-clinical 25c |

Device (Active style Pro HJA-350IT) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) |

Unadjusted model: none Model 2: age, gender, education, income, alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, living status, perceived health, morbidities, depression and PA |

Cross-sectional (B) Unadjusted: − 0.005 [− 0.015, 0.004], p = 0.25 Model 2: 0.006 [− 0.006, 0.018], p = 0.35 Longitudinal (2-year follow-up) Unadjusted: − 0.003 [− 0.009, 0.004], p = 0.40 Model 2: − 0.001 [− 0.010, 0.007], p = 0.73 |

|

|

SLAS2 Cohort n = 3087, Mage = 66.7 (7.8), %F = 63, SB time = 366 Population: non-clinical 25d |

Self-report (asked two questions relating to SB on a usual day, which distinguished between weekdays and weekend days) | Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) |

Model 1: unadjusted Model 2: age, gender, ethnicity, education, alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, marital status, living status, perceived health, morbidities, blood pressure, sleep quality, depression and PA |

Cross-sectional (B) Unadjusted: 0.04 [− 0.004, 0.083], p = 0.08 Model 2: 0.118 [0.075, 0.160], p = < 0.001 Longitudinal (3.8-year follow-up) Unadjusted: − 0.007 [− 0.021, 0.007], p = 0.32 Model 2: − 0.011 [− 0.027, 0.004], p = 0.16 |

|

|

Marinac et al. (2019) [64] USA CS Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 26 |

n = 30, Mage = 62.2 (7.8), %F = 100, SB time = 498 Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) |

Cognitive Flexibility (The Dimensional Change Card Sort Test) Executive Function (FLA) Episodic Memory (Picture Sequence Memory Test) Working Memory (List Sorting) Processing Speed (Pattern Comparison Test) |

device wear time, education, employment status, MVPA, chemotherapy status |

Total sitting time: (b, p) Executive Function: 0.21, 0.88 Cognitive Flexibility: − 2.75, 0.06 Episodic memory: 2.69, 0.34 Working memory: − 1.01, 0.63 Processing speed: − 2.47, 0.32 |

|

Olanrewaju et al. (2020) [80] Ireland CS Study number in pinwheel = 47 |

n = 8163, Mage = 63.5 (9.2), %F = 52, SB time = 295 Population: non-clinical |

Self-report (International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)) |

Processing Speed (AF) Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) Episodic Memory (Immediate and delayed recall) |

Age, sex, social class |

Episodic memory: β (95% CI) 0.01 (− 0.004, 0.02), p > 0.05 Processing Speed: β (95% CI) 0.003 (− 0.01, 0.01), p > 0.05 Global Cognitive Function: β (95% CI) 0.01 (− 0.01, 0.02), p > 0.05 |

|

Rosenberg, et al. (2016) [51] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 27 |

n = 307, Mage = 83.6 (6.4), %F = 72, SB time = 516 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Working Memory & Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B) Processing Speed (TMT A) |

age, gender, marital status, educational status, MVPA, wear time |

Objective Sedentary Time (β (SE)) TMT A: − 0.02 (0.02) p = 0.33 TMT B: − 0.03 (0.02) p = 0.18 |

|

n = 280, SB time = 660 Population: non-clinical |

Self-report (Sedentary Behaviour Questionnaire) |

Working Memory & Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B) Processing Speed (TMT A) |

age, gender, marital status, educational status, MVPA |

Self-reported SB (β(SE)) TMT A: − 0.01 (0.00) p = < 0.01 TMT B: 0.01 (0.01) p = 0.08 |

|

|

Siddarth et al., (2018) [81] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 28 |

n = 35, Mage = 60.4 (8.1), %F = 71, SB time = 432 Population: non-clinical |

Self-report [International Physical Activity Questionnaire modified for older adults (average number of hours spent sitting)] |

Episodic Memory (Verbal paired association, Selective reminding scores) Processing Speed (Digit symbol scores) |

age |

Verbal paired association: r = 0.12 p = 0.5 Selective reminding scores: r = 0.28 p = 0.11 Digit symbol scores: r = −0.18 p = 0.34 |

|

Snethen et al. (2014) [44] USA CS 29 Study number in pinwheel = 29 |

n = 30, Mage = 50.6 (nr), %F = 10, SB time = 406 Population: clinical |

Device (Actigraph) | Cognitive Flexibility (WCST) | Diagnosis, sex, age, BMI | r = 0.04, p > 0.05 |

|

Stubbs et al. (2017) [56] Taiwan CS Study number in pinwheel = 30 |

Schizophrenia n = 199, Mage = 44.0 (9.9), %F = 39, SB time = 581 Controls n = 60, Mage = 41.9 (9.6), %F = 43, SB time = 336 Population: mixed |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (COG) Motor Skills and Construction (Reaction Test, GPT) |

Model 1: age, sex, education, weight status, smoking, alcohol consumption, medications, PANSS, MetS Model 2: age, sex, education, weight status, smoking, alcohol consumption, medications, PANSS, MetS, Physical activity energy expenditure |

Total SB and cognitive function outcomes Schizophrenia group COG: p = 0.403 GPT: p = 0.020 Reaction Time reaction (msec): p = 0.984 Reaction Time motor (msec): p = 0.070 control group COG: p = 0.295 GPT: p = 0.016 Reaction Time reaction (msec): p = 0.016 Reaction Time motor (msec): p = 0.378 Comparing means b/w low and high SB in Patients with Schizophrenia Reaction Time reaction (msec) p = 0.803 669.5 (SD = 532.2) low sed 652.3 (SD = 410.0) high sed Reaction Time motor (msec), p = 0.037 355.2 (SD = 170.8) low sed 421.3 (SD = 252.7) high sed COG, p = 0.442 176.9 (SD = 95.1) low sed 165.8 (SD = 107.1) high sed GPT: p = 0.034 131.6 (SD = 44.1) low sed 145.4 (SD = 46.7) high sed |

|

Suzuki et al. (2020) [57] Japan CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = 48 |

Males n = 68, Mage = 88.0 (1.0), %F = 0, SB time = 855 Females n = 68, Mage = 88.0 (0.9), %F = 100, SB time = 798 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Global Cognitive Function (ACE) Score of ≤ 88 indicating cognitive impairment |

Single Factor Model: device wear time, age, education and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Partition Model: All time units spent performing any of the activity categories and covariates were entered into the same model, and the independent effects of each behavioral variable were examined |

Males Time in SB and cognitive function β = −0.069, p = 0.332 Females Time in SB and cognitive function β = −0.026, p = 0.758 |

|

Vancampfort et al. (2018) [52] China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa CS Study number in pinwheel = 31 |

Whole sample: n = 32,715, Mage = 62.1 (15.6), %F = 50 MCI n = 4082, Mage = 64.4 (17.0), %F = 55, SB time = 262 Population: mixed |

Self-report (Global physical activity questionnaire) | Global Cognitive Function (Based on the recommendations of the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association) | sex, age, years of education, wealth, depression, obesity, number of chronic conditions, low PA, country |

OR [95% CI] ≥ 8 h vs < 8/day SB and cognitive function 1.56 [1.27, 0.91], p < 0.001 1 h increase in SB 1.08 [1.05–1.11], p < 0.001 |

|

Vance et al. (2016) [49] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 32 |

n = 122, Mage = 70.5 (7.2), %F = 57, SB time = 803 Population: non-clinical |

Self-report (Single item from the Physical activity questionnaire) |

Processing Speed (AF, TMT A) Episodic Memory (CVLT-II) Working Memory & Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B) |

Not reported |

Correlations with SB AF: r = −0.09, p = ns CVLT-II: r = 0.00, p = ns TMT A: r = 0.10, p = ns TMT B: r = −0.03, p = ns |

|

Vasquez et al. (2017) [47] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 33 |

n = 7478, age range: 45–75, %F = 62, SB time = 738 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actical model 198–0200-06) Self-report (not reported) |

Global Cognitive Function (cognitive function overall score) Episodic Memory (B-SEVLT) Processing Speed (Word fluency, DSST) |

Sex |

Device measured SB (each 10 min/day increase) β (SE): Cognitive Function overall score: − 0.044 (0.006), p < 0.0001 Word Fluency: − 0.004 (0.002), p = 0.0356 DSST: − 0.198 (0.022), p < 0.0001 SEVLT Sum3 trials: − 0.033 (0.005), p < 0.0001 SEVLT Free recall: − 0.033 (0.005), p < 0.0001 Self-reported sedentary time (each 10 min/day increase): Cognitive Function overall score: 0.019 (0.003), p < 0.0001 Word Fluency: 0.006 (0.001), p < 0.0001 DSST: 0.115 (0.014), p < 0.0001 SEVLT Sum3 trials: − 0.033 (0.005), p = 0.1154 SEVLT Free recall: 0.005 (0.003), p = 0.0583 |

|

Wanigatunga et al. (2018) [53] USA CS Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 34 |

n = 1275, Mage = 79 (5.0), %F = 67, SB time (min–max) = 24–512 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (DSC) Episodic Memory (HVLT-Revised) Working Memory (n-back) Cognitive Flexibility (Task switching paradigm) Executive Function (FLA) Global Cognitive Function (global composite: DSC, HVLT, n-back, task switching paradigm) |

age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, BMI, smoking status, sleep quality, perceived stress, living with two or more morbid conditions |

Associations b/w low and high total SB, β (SE) one-back high: − 0.012 (0.013) two back high: 0.001 (0.016) DSC high: − 2.03 (0.854), p < 0.05 task-switching (no) high: 86.22 (74.541) task-switching (yes) high: 117.953 (94.122) FLA congruent high: 24.541 (15.994) FLA incongruent high: 18.602 (23.158) HVLT immediate high: 0.385 (0.363) HVLT delayed high: 0.252 (0.197) global cognitive function: 0.085 (0.047) |

|

Watts et al. (2018) [54] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 35 |

Mild AD n = 47, Mage = 73.1 (8.0), %F = 34, SB time = 584 Controls n = 53, Mage = 73.2 (6.5), %F = 69, SB time = 556.8 Population: mixed |

Device (activPAL) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) Processing Speed (WAIS-DSST, block design, digits forward, AF, vegetable fluency, TMT A) Executive Function (Stroop) Cognitive Flexibility (Letter number sequencing, TMT B) Working Memory (Letter number sequencing, DSB, TMT B) Episodic Memory (logical memory immediate, logical memory delayed) Mild AD diagnosis: = 0.5 (very mild) or 1 (mild) Controls: = 0 (no dementia) |

None |

(whole sample, n = 83): MMSE: r = −0.082 WAIS: r = −0.053 Block Design: r = 0.044 Stroop Interference: r = −0.129 Letter Number Sequencing: r = 0.139 Logical Memory Immediate: r = −0.285, p = 0.015 Logical Memory Delayed: r = −0.267, p = 0.022 Digits Forward: r = −0.011 Digits Backward: r = 0.000 Animal fluency: r = −0.156 Vegetable fluency: r = −0.165 TMT A: r = 0.093 TMT B: r = 0.148 |

|

Wei et al. (2021) [43] USA CS Isotemporal Study number in pinwheel = 52 |

Sleep ≤ 7 h per night n = 1843, Mage = nr %F = ~ 50, SB time = nr Sleep > 7 h per night n = 1243, Mage = nr %F = ~ 43, SB time = nr Population: non-clinical |

Self-report (The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire) Isotemporal: Replacing sleep, sedentary activity, walking/bicycling, MVPA with each other |

Episodic Memory (CERAD Word Learning subtest) Processing Speed (DSST, AF) |

age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, smoking, and body mass index |

Sleep ≤ 7 h per night; β (95% CI) DSST: 0.002 (− 0.01, 0.01) CERAD: 0.01 (0.003, 0.02), p < 0.05 AF: 0.01 (0.003, 0.02), p < 0.05 Sleep > 7 h per night; β (95% CI) DDST: 0.003 (− 0.01, 0.01) CERAD: 0.01 (− 0.003, 0.02) AF: 0.003 (− 0.01, 0.02) Among participants with sleep duration ≤ 7 h/night, replacing 30 min/day of sedentary activity with 30 min/day of MVPA or 30 min/day was associated with better cognition. Among participants with sleep duration > 7 h/night, replacing 30 min/day of sleep with 30 min/day of sedentary activity, walking/bicycling, or MVPA was associated with better cognition |

|

Wu et al. (2020) [63] China CS Study number in pinwheel = 53 |

n = 308, Mage = 68.66 (5.37), %F = 57, SB time = 591 Population: non-clinical |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) |

Model 1: uncorrected Model 2: age, BMI, highest education, monthly average income. SED sedentary behavior, LPA light physical activity, MVPA moderate-vigorous physical activity, TPA total physical activity |

SB and Global Cognitive Function Model 1: β = −0.020 SE = 0.001, p = 0.061 Male subgroup β = −0.003 SE = 0.001 p = 0.029 |

|

Zhu, W. et al. (2015) [67] USA CS Study number in pinwheel = 38 |

n = 7098, Mage = 70.1 (8.5), %F = 54.2, SB time = nr Population: clinical |

Device (Actical) |

Episodic Memory (word list learning, recall) Processing Speed (semantic fluency, letter fluency) Global Cognitive Function (items from MOCA) |

Model 1 was unadjusted Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, race, region of residence, education, ST%, BMI, hypertension, smoking, and diabetes mellitus |

Not reported |

|

Zlatar (2019) [66] USACS Study number in pinwheel = 37 |

n = 52, Mage = 72.3 (5.0), %F = 57.7, SB time = 548 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (Letter fluency) Executive Function (colour word inhibition Working Memory (TMT B) Cognitive Flexibility (TMT B, WCST) Episodic Memory (Face naming score, CVLT, WMS-R) |

Unadjusted |

CWI switch: r = 0.118, p > 0.05 CWI: r = −0.011, p > 0.05 letter fluency: r = −0.129, p > 0.05 TMT B: r = −0.087, p > 0.05 WCST: r = 0.036, p > 0.05 face naming score: r = −0.232, p > 0.05 CVLT-II List A: r = 0.195, p > 0.05 CVLT-II short delay: r = 0.184, p > 0.05 CVLT-II long delay: r = 0.187, p > 0.05 WMS-R LMI: r = 0.248, p > 0.05 WMS-R LMII: r = 0.254, p > 0.05 |

ACE Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, AF Animal Fluency, AOS Automated Operation Span, B-SEVLT Brief Spanish English Verbal learning Test, BVMT Brief Visuospatial Memory Test, CVLT California Verbal Learning Test, AD8 Chinese version of the Ascertain Dementia 8-item questionnaire, COG Cognitrone Test, CS Cross Sectional, DSB Digit Span Backwards, DSC Digit Symbol Coding, DSST Digit Symbol Substitution Task, FLA Flanker or Eriksen Flanker Test, GPT Grooved Pegboard Test, HVLT Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, LO Longitudinal, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, nr Not reported, PASAT Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, RT Reaction Time, SB Sedentary Behaviour, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, TMT A Trail Making Test A, TMT B Trail Making Test B, VF Verbal Fluency, WAIS Wecshler Adult Intelligence Scale, WMS-R Wechsler Memory Scale-revised, WCST Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, 3MS Modified Mini Mental State Examination

Table 2.

Summary and characteristics of cross-sectional studies reporting the associations for pattern of sedentary behaviour accumulation with cognitive function

| Authors (year) Country Study Design Pinwheel number |

Participants Mean age (Mage) % F (female) SB time (min) |

Device or self-report (measure of sedentary behaviour) | Domain (outcome measure) | Covariates adjusted for | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bollaert et al. (2019) [68] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 39 |

Healthy group n = 40, Mage = 66.5 (6.7), %F = 62.5, SB time = 534 Multiple Sclerosis group n = 40, Mage = 65.3 (4.3), %F = 62.5, SB time = 540 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Processing Speed (SDMT, PASAT) Episodic Memory (BVMT, CVLT-II) |

Not stated |

# of SB bouts Between groups p > 0.05 Healthy Controls (r) SDMT: − 0.12 CVLT-II: − 0.17 BVMT-R: − 0.04 PASAT: − 0.08 MS group (r) SDMT: 0.09 CVLT-II: 0.24 BVMT-R: 0.08 PASAT: 0.20 Duration of SB bouts: Between groups p > 0.05 Healthy Controls (r) SDMT: − 0.11 CVLT-II: − 0.10 BVMT-R: 0.10 PASAT: 0.01 MS group (r) SDMT: − 0.22 CVLT-II: 0.01 BVMT-R: − 0.08 PASAT: − 0.18 # of long SB bouts (> 30 min) Between groups p > 0.05 Healthy Controls (r) SDMT: − 0.08 CVLT-II: − 0.27 BVMT-R: 0.02 PASAT: − 0.09 MS group (r) SDMT: − 0.17 CVLT-II: 0.22 BVMT-R: − 0.02 PASAT: 0.03 Duration of long SB bouts Between groups p < 0.015 Healthy Controls (r) SDMT: − 0.21 CVLT-II: − 0.02 BVMT-R: 0.11 PASAT: − 0.01 MS group (r) SDMT: − 0.05 CVLT-II: 0.04 BVMT-R: − 0.02 PASAT: 0.08 |

Pattern of SB was not associated with cognitive function Duration of long sedentary bouts were longer in the MS group compared to the controls |

|

Cukic et al. (2018) [35] Scotland CS/LO Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 3a,b,c |

LBC1936 cohort n = 271, Mage = 79.0 (0.4) % F = 48.3, SB time = 626.8 Population: non-clinical 3a |

Device (activPal3) |

Global Cognitive Function (general cognitive ability factor (g) computed from 6 tests taken from the WAIS (Matrix Reasoning, Block Design, Letter-Number Sequencing, Symbol Search, DSB, and Digit Symbol), Moray Houst Test No. 12 (MHT), Alice Heim 4 test (AH4)) Processing Speed Four-choice (RT) Motor Skills and Construction (Simple RT) |

Model 1: age and sex Model 3: age, sex, education, long standing illness |

Interruptions: β, [95% CI] Model 1 g-factor: 0.02 [− 0.10, 0.14], p = 0.80 Simple RT: 0.00 [− 0.12, 0.12], p = 0.99 Choice RT: − 0.03 [− 0.15, 0.09], p = 0.60 MHT Age 11: 0.07 [− 0.05, 0.19], p = 0.24 MHT change age 11–79: 0.03 [− 0.11, 0.14], p = 0.99 Model 3 g-factor: − 0.04 [− 0.18, 0.10], p = 0.61 Simple RT: 0.01 [− 0.11, 0.13], p = 0.89 Choice RT: 0.03 [− 0.15, 0.09], p = 0.60 MHT change age 11–79: 0.01 [− 0.01, 0.03], p = 0.99 |

Interruptions in SB were not associated with cognitive function |

|

Twenty-07 1950’s cohort n = 310, Mage = 64.6 (0.9) %F = 53.2, SB time % = 60.8 Population: non-clinical 3b |

Model 1: age and sex Model 4: age, sex, education, long standing illness, employment status |

Interruptions: β, [95% CI] Model 1 AH4 wave 5: 0.05 [− 0.07, 0.17], p = 0.37 Simple RT wave 5: − 0.06 [− 0.18, 0.06], p = 0.27 Choice RT wave 5: − 0.04 [− 0.16, 0.08], p = 0.49 Model 4 AH4 wave 5: 0.11 [− 0.03, 0.25], p = 0.11 Simple RT wave 5: − 0.06 [− 0.06, 0.18], p = 0.29 Choice RT wave 5: − 0.05 [− 0.17, 0.07], p = 0.43 |

Interruptions in SB were not associated with cognitive function | |||

|

Twenty-07 1930’s cohort n = 119, Mage = 83.4 (0.6) % F = 54.6, SB time % = 68.2 Population: non-clinical 3c |

Model 1: age and sex Model 3: age, sex, education, long standing illness |

Cog ability & SB interruptions: β, [95% CI] Model 1 AH4 wave 1: 0.08 [− 0.10, 0.26], p = 0.41 AH4 wave 5: 0.05 [− 0.15, 0.25], p = 0.60 Simple RT: − 0.07 [− 0.27, 0.13], p = 0.47 Choice RT: 0.09 [− 0.09, 0.27], p = 0.32 Model 3 AH4 wave 1: 0.13 [− 0.09, 0.35], p = 0.24 AH4 wave 5: 0.10 [− 0.12, 0.32], p = 0.41 Simple RT: − 0.09 [− 0.29, 0.11], p = 0.39 Choice RT: 0.04 [− 0.21, − 0.29], p = 0.77 |

Interruptions in SB were not associated with cognitive function | |||

|

English et al. (2016) [74] Australia CS Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 7 |

n = 50, Mage = 67.2 (11.6) % F = 34.0, SB = nr Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | Waking hours |

MoCA with prolonged sitting time (≥ 30) r = −0.006, p = 0.970 |

Prolonged sitting was not associated with cognitive function |

|

Ezeugwu et al. (2017) [75] Canada CS Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 8 |

n = 30, Mage = 63.8 (12.3) % F = 43.3, SB time = 673.9 Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | Not reported |

Sedentary interruptions and MoCA r = 0.07, p > 0.05 |

Interruptions in SB time were not associated with cognitive function |

|

Falck et al. (2017) [55] Canada CS Prevalence Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 10 |

Probable MCI n = 81, Mage = 72.5 (7.6) % F = 59.8, SB time = 594.8 Without MCI n = 69, Mage = 69.4 (6.4) % F = 77.9, SB time = 541.6 Population: mixed |

Device (MotionWatch8) |

Global Cognitive Function (MoCA, ADAS-Cog Plus) Probable MCI = MoCA < 26 |

Age, sex, education |

Mean (SD) b/n those with MCI & without Average 30 + min bouts/day SB with probable MCI = 4.07 (1.85)without MCI = 3.30 (1.73) p = 0.046 SB and ADAS-Cog Plus (β) Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.061, p = 0.016 SB and ADAS-Cog Plus Based on MCI Status (β) non-MCI Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.075, p = 0.064 MCI Average 30 + min bouts/day: 0.033, p = 0.282 |

Participants with probable MCI had more 30 + min bouts/day of SB compared to those without MCI Significant association between greater 30 + min bouts/day of SB and poorer cognitive performance Marginal relationship between greater 30 + min bouts/day of SB and poorer cognitive function for participants without MCI No relationship for more 30 + min bouts of SB and cognitive performance for those with probable MCI |

|

Hartman et al. (2018) [83] Netherlands CS Prevalence Pattern Study # in pinwheel = N/A |

Dementia n = 45, Mage = 79.6 (5.9) % F = 51, SB time = 510 Controls n = 49, Mage = 80.0 (7.7) % F = 48.9, SB time = 486 Population: mixed |

Device (Philips Actiwatch 2) | Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) | Not reported |

# of interruptions in SB (SD) Dementia: 28.2 (26.2–32.5) Control: 27.2 (24.5–31.0) p = 0.195 # of 30 min prolonged bouts (SD) Dementia: 2.0 (0.9–3.3) Control: 2.3 (1.0–4.1) p = 0.227 Duration of avg SB bout (SD) Dementia: 16.6 (15.3–18.4) Control: 18.3 (16.4–21.1) p = 0.008 |

No significant difference between groups for number of interruptions or number of 30-min prolonged bouts of SB The dementia patients had significantly longer durations of SB bouts compared to the controls |

|

Leung et al. (2017) [76] Canada CS Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 22 |

n = 114, Mage = 86.7 (7.5) % F = 85.1, SB = 835 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) | Global Cognitive Function (MoCA) | Not reported |

# of sedentary bouts: p > 0.05 Duration of sedentary bouts: p > 0.05 |

Number and duration of SB bouts were not associated with cognitive function |

|

Lu et al. (2018) [84] Hong Kong CS Prevalence Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 24 |

Healthy: n = 271, Mage = 81.9 (3.5), % F = 38.2 Low MoCA: n = 252, Mage = 83.4 (4.0), % F = 47.6 MCI: n = 105, Mage = 83.6 (3.7), % F = 48.6 AD: n = 182, Mage = 80.8 (5.9), % F = 65.4 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (Hong Kong version of MoCA) |

Model 1: age, gender, wear time Model 2: age, gender, wear time, years of education, BMI, unusual gait speed, living status, disease burden |

Average SB bout length compared to the AD group: Controls: 6.6 (0.2), p < 0.05 Low MoCA: 6.5 (0.2), p < 0.05 MCI: 6.3 (0.3), p < 0.05 AD: 7.9 (0.2) # of SB bouts > 30 min compared to the AD group = Controls: 3.3 (0.1), p < 0.05 Low MoCA: 3.3 (0.1), p < 0.05 MCI: 3.5 (0.2), p < 0.05 AD: 4.1 (0.1) |

AD patients had longer SB bouts compared to the other 3 groups AD patients had more SB bouts > 30 min compared to the other 3 groups |

|

Marinac et al. (2019) [71] USA CS Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 26 |

n = 30, Mage = 62.2 (7.8) % F = 100, SB time = 498 Population: clinical |

Device (activPAL) |

Cognitive Flexibility (The Dimensional Change Card Sort Test) Executive Function (FLA) Episodic Memory (Picture Sequence Memory Test) Working Memory (List Sorting) Processing Speed (Pattern Comparison Test) |

Device wear time, education, employment status, MVPA, chemotherapy status |

Time in sitting bouts > 20 min: (b, p) Executive Function: − 0.73, 0.54 Cognitive Flexibility: − 2.82, 0.02 Episodic memory: 3.29, 0.17 Working memory: 1.36, 0.44 Processing speed: − 1.21, 0.57 Sit-to-stand transitions: (b, p) Executive Function: 0.14, 0.27 Cognitive Flexibility: 0.16, 0.2 Episodic memory: − 0.06, 0.82 Working memory: − 0.36, 0.051 Processing speed: 0.07, 0.77 |

More time spent in prolonged sitting bouts was associated with worse cognitive flexibility scores More sit-to-stand transitions was not associated with cognitive function |

|

Wanigatunga et al. (2018) [53] USA CS Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 34 |

n = 1275, Mage = 79 (5.0) % F = 67, SB time (min–max) = 24–512 Population: non-clinical |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed (Digit Symbol Coding (DSC)) Episodic Memory (HVLT) Working Memory (n-back) Cognitive Flexibility (Task switching paradigm) Executive Function FLA Global Cognitive Function (DSC, HVLT, n-back, task switching paradigm) |

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, BMI, smoking status, sleep quality, perceived stress, living with two or more morbid conditions |

Association’s b/w low and high 30 + min bouts of SB [b, (SE)] One-back high: − 0.014 (0.013) Two back high: − 0.003 (0.016) DSC high: − 0.519 (0.879) Task-switching (no) high: 50.636 (76.635) Task-switching (yes) high: 27.604 (96.787) Flanker congruent high: 12.798 (16.416) Flanker incon high: 3.798 (23.759) HVLT immediate high: 0.284 (0.372) HVLT delayed high: 0.199 (0.202) Global composite high: − 0.012 (0.048) |

No significant associations for more 30 + min bouts of SB and cognitive function |

|

Watts et al. (2018) [54] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study # in pinwheel = 35 |

Mild AD n = 47, Mage = 73.1 (8.0) % F = 34. SB time = 584 Controls n = 53, Mage = 73.2 (6.5) % F = 69, SB time = 556.8 Population: mixed |

Device (activPAL) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) Mild AD diagnosis: = 0.5 (very mild) or 1 (mild) Controls: = 0 (no dementia) |

None |

# interruptions, (SD) Mild AD activPAL: 42.28 (13.43) Controls activPAL: 47.52 (12.01) p = 0.06 30 + min bouts Mild AD activPAL: 5.49 (1.35) Controls activPAL: 4.91 (1.57) p = 0.07 |

Number of SB interruptions or 30 + min bouts of SB did not differ between groups |

ACE Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, AD Alzheimer’s Disease, AF Animal Fluency, AOS Automated Operation Span, BVMT Brief Visuospatial Memory Test, CVLT California Verbal Learning Test, COG Cognitrone Test, DSB Digit Span Backwards, DSST Digit Symbol Substitution Task, FLA Flanker or Eriksen Flanker Test, GPT Grooved Pegboard Test, HVLT Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Mage Mean Age, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, PASAT Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, RT Reaction Time, SB Sedentary Behaviour, SDMT Symbol Digit Modalities Test, TMT A Trail Making Test A, TMT B Trail Making Test B, VF Verbal Fluency, WAIS Wecshler Adult Intelligence Scale, WCST Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

Table 3.

Summary and characteristics of cross-sectional studies reporting prevalence of sedentary behaviour for clinical and non-clinical populations

| Authors (year) Country Study Design Pinwheel number |

Participants Mean age (Mage) % F (female) SB time (min) |

Device or self-report (measure of sedentary behaviour) | Domain (outcome measure) | Covariates adjusted for | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amagasta et al. (2020) [77] Japan CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = 1 |

Cognitive decline n = 48, Mage = 77.6 (5.4) % F = 52, SB time = 476.2 Non-cognitive decline n = 463, Mage = 73.0 (5.4), % F = 53, SB time = 442.4 Population: mixed |

Device (Active style Pro HJA-750C) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) ≤ 23 = Cognitive Function Decline (CFD) |

Model 1: unadjusted Model 4: Gender, age, education, BMI, living arrangements, working status, smoking, alcohol use, past history of stroke, medication for hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes |

SB (min) mean (SD) Cognitive Decline 476.2 (153.9) Non-Cognitive Decline 442.4 (126.8) p = 0.086 |

No significant difference in total SB time between the two groups |

|

Bollaert & Motl (2019) [68] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 39 |

Healthy group n = 40, Mage = 66.5 (6.7) % F = 62.5, SB time = 534 Multiple Sclerosis group n = 40, Mage = 65.3 (4.3) % F = 62.5, SB time = 540 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Processing Speed (SDMT, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test) Episodic Memory (Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-revised, CVLT-II) |

Not stated |

Total SB Between groups p < 0.05 # of SB bouts Between groups p > 0.05 Duration of SB bouts: Between groups p > 0.05 # of long SB bouts (> 30 min) Between groups p > 0.05 Duration of long SB bouts Between groups p < 0.015 |

Total SB time was significantly greater in the impaired group Duration of SB bouts were significantly greater for impaired group |

|

Da Ronch et al. (2015) [46] Italy Switzerland Germany CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = N/A |

Whole sample n = 1383 Mage = 73.1 (5.7), %F = 47.6 MCI: n = 251 No cognitive impairment: n = 1132 Population: mixed |

Self-report (Self-report daily hours sitting) |

Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) 18–26 = MCI 27–30 = No cognitive impairment |

Gender, age, education, employment status, financial situation, living status, study centre |

mean hours/day (SD) MCI: 3.98 (SD = 1.42) No MCI: 3.62 (SD = 1.4) p < 0.001 |

Total SB was significantly higher in the impaired group |

|

Falck et al. (2017) [55] Canada CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 10 |

Probable MCI n = 81, Mage = 72.5 (7.6) % F = 59.8, SB time = 594.8 Without MCI n = 69, Mage = 69.4 (6.4) % F = 77.9, SB time = 541.6 Population: mixed |

Device (MotionWatch8) |

Global Cognitive Function (MoCA, ADAS-Cog Plus) Probable MCI = MoCA < 26 |

Age, sex, education |

Mean (SD) b/n those with MCI & without % Sedentary time with probable MCI = 61.65 (11.35) without MCI = 57.24 (12.38) p = 0.161 Average 30 + min bouts/day SB with probable MCI = 4.07 (1.85) without MCI = 3.30 (1.73) p = 0.046 |

Total SB time did not significantly differ between groups Impaired group had significantly more 30 + min bouts of SB/day compared to the non-impaired group |

|

Hartman et al. (2018) [83] Netherlands CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = N/A |

Dementia n = 45, Mage = 79.6 (5.9) % F = 51, SB time = 510 Controls n = 49, Mage = 80.0 (7.7) % F = 48.9, SB time = 486 Population: mixed |

Device (Philips Actiwatch 2) | Global Cognitive Function (MMSE) | Not reported |

SB minutes (SD) Dementia: 510 (432–600) Control: 486 (432–552) p = 0.0216 # of interruptions in SB (SD) Dementia: 28.2 (26.2–32.5) Control: 27.2 (24.5–31.0) p = 0.195 # of 30 min prolonged bouts (SD) Dementia: 2.0 (0.9–3.3) Control: 2.3 (1.0–4.1) p = 0.227 Duration of avg SB bout (SD) Dementia: 16.6 (15.3–18.4) Control: 18.3 (16.4–21.1) p = 0.008 |

Total SB time was significantly greater in the impaired group Number of SB interruptions or number of 30 + min SB bouts did not significantly differ between groups Duration of SB bouts were significantly greater for impaired group |

|

Lu et al. (2018) [84] Hong Kong CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 24 |

Healthy: n = 271, Mage = 81.9 (3.5), % F = 38.2 Low MoCA: n = 252, Mage = 83.4 (4.0), % F = 47.6 MCI: n = 105, Mage = 83.6 (3.7), % F = 48.6 AD: n = 182, Mage = 80.8 (5.9), % F = 65.4 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) | Global Cognitive Function (Hong Kong version of MoCA) |

Model 1: age, gender, wear time Model 2: age, gender, wear time, years of education, BMI, unusual gait speed, living status, disease burden |

Time in SB (min/day): Controls = 546.7 Low MoCA = 534.1 MCI = 516.9 AD = 601.2 Average SB bout length: Controls: 6.6 (0.2)* Low MoCA: 6.5 (0.2)* MCI: 6.3 (0.3)* AD: 7.9 (0.2) # of SB bouts > 30 min = Controls: 3.3 (0.1)* Low MoCA: 3.3 (0.1)* MCI: 3.5 (0.2)* AD: 4.1 (0.1) *p < 0.05 compared to the AD group |

The most impaired group (AD) spent significantly more time in SB The most impaired group (AD) had significantly more 30 + min SB bouts |

|

Marmeleria et al. (2017) [85] Portugal Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = N/A |

Cognitively impaired: n = 48, Mage = 83.9 (7.7), %F = 73, SB time = 604 MMSE = 14.9 (4.9) Healthy: n = 22, Mage = 82.2 (8.8), %F = 55, SB time = 601 MMSE = 25.8 (2.2.) Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) | Motor Skills and Construction (Dear-Leiwald Reaction task) | age, gender, and accelerometer wear time |

Sedentary time p > 0.05 Reaction time p > 0.05 |

No significant difference in total SB time between the two groups |

|

Stubbs et al. (2017) [56] Taiwan CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = 30 |

Schizophrenia n = 199, Mage = 44.0 (9.9) % F = 38.7, SB time = 581 Controls n = 60, Mage = 41.9 (9.6) % F = 43.3, SB time = 336 Population: mixed |

Device (ActiGraph) |

Processing Speed, (Cognitrone test (COG)) Motor Skills and Construction (Reaction Test, Grooved Pegboard Test (GPT)) |

Model 1: age, sex, education, weight status, smoking, alcohol consumption, medications, PANSS, MetS Model 2: age, sex, education, weight status, smoking, alcohol consumption, medications, PANSS, MetS, Physical activity energy expenditure |

p < 0.001 | Total SB time was significantly greater in the impaired group |

|

Suzuki et al. (2020) [57] Japan CS Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = 48 |

Males n = 68, Mage = 88.0 (1.0), %F = 0, SB time = 855 Females n = 68, Mage = 88.0 (0.9), %F = 100, Sb time = 798 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Global Cognitive Function (ACE-III) Score of ≤ 88 indicating cognitive impairment |

Single Factor Model: device wear time, age, education and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Partition Model: All time units spent performing any of the activity categories and covariates were entered into the same model, and the independent effects of each behavioral variable were examined |

SB time (min), SD Males Cognitive Decline Group (n = 54) 859.1 (149.2) Cognitive Maintain Group (n = 14): 837.4 (130.3) p = 0.363 Females Cognitive Decline Group (n = 50): 788.6 (150.0) Cognitive Maintain Group (n = 18): 824.8 (116.0) p = 0.357 |

No significant difference in total SB time between the two groups |

|

van Alphen et al. (2016) [45] Netherlands Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = N/A |

Institutionalized dementia patients n = 83, age: 83.0 (7.6), % F = 79.5 MMSE: 15.5 ± 6.5 Community dwelling dementia patients n = 37, Mage = 77.3 (5.6) % F = 40.5 MMSE = 20.8 (4.8) Healthy older adults n = 26, Mage = 79.5 (5.6) % F = 50 MMSE: 28.2 ± 1.6 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) | Cognitive status (MMSE) | Age, and cognitive state (MMSE) |

SB time was different for the 3 groups (F(2,143) = 9.891, p < .001) institutionalized dementia patients: SB h/day = 17.30 (3.24) community dwelling dementia patients: SB h/day = 15.83 (2.72) healthy control: SB h/day = 14.54 (1.92) |

Total SB time was significantly different in the three groups, with the greatest total SB time in the most impaired group |

|

Vancampfort et al. (2018) [52] China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa CS Study number in pinwheel = 31 |

Whole sample: n = 32,715, Mage = 62.1 (15.6) % F = 50.1 MCI n = 4082, Mage = 64.4 (17.0) % F = 55.1, SB time = 262 Population: mixed |

Self-report (Global physical activity questionnaire) | Global Cognitive Function (Based on the recommendations of the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association) | Sex, age, years of education, wealth, depression, obesity, number of chronic conditions, low PA, country |

Sedentary < 4 h/day, prevalence of MCI = 13.5% Sedentary ≥ 11 h/day, prevalence of MCI = 21.3% |

The prevalence of MCI increased with increasing hours per day spent sedentary |

|

Varma et al. (2017) [86] USA Prevalence Study number in pinwheel = N/A |

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease n = 36, Mage = 73.5 (7.9), % F = 28 SB time = 585 Controls n = 53, Mage = 73.2, %F = 70 SB time = 518 Population: mixed |

Device (Actigraph) |

Cognitive Status (clinical dementia rating scale scores) 0 (normal) 0.5 (very mild) 1 (mild) |

Cardiorespiratory capacity, body mass index, mobility impairment, age, sex, and race | Difference (Mild AD—Control) sedentary minutes: − 5.738 (SE = 26.691) p = 0.830 | Total SB was significantly higher in the impaired group |

|

Watts et al. (2018) [54] USA CS Prevalence Pattern Study number in pinwheel = 35 |

Mild AD n = 47, Mage = 73.1 (8.0) % F = 34. SB time = 584 Controls n = 53, Mage = 73.2 (6.5) % F = 69, SB time = 556.8 Population: mixed |

Device (activPAL) |