Abstract

Objectives: This meta-analysis aimed to assess the effectiveness and safety of Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) in treating chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS).

Methods: Nine electronic databases were searched from inception to May 2022. Two reviewers screened studies, extracted the data, and assessed the risk of bias independently. The meta-analysis was performed using the Stata 12.0 software.

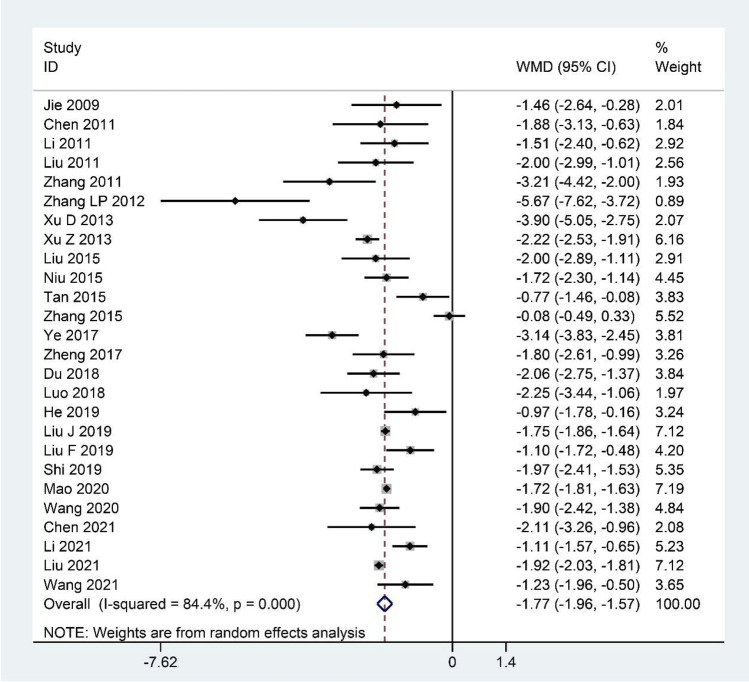

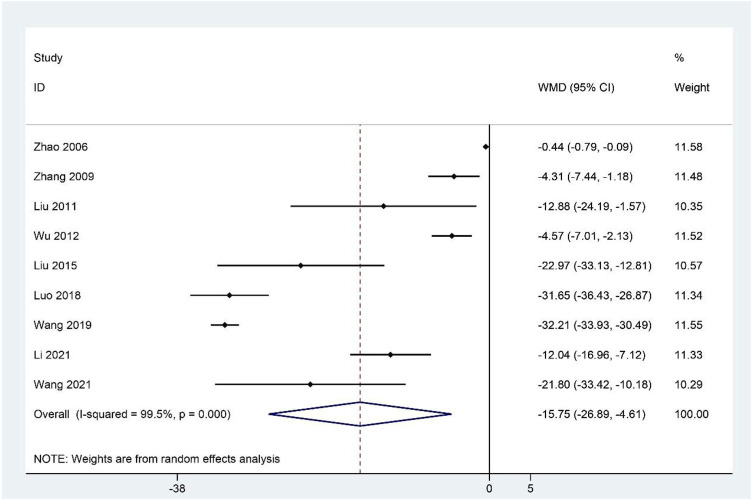

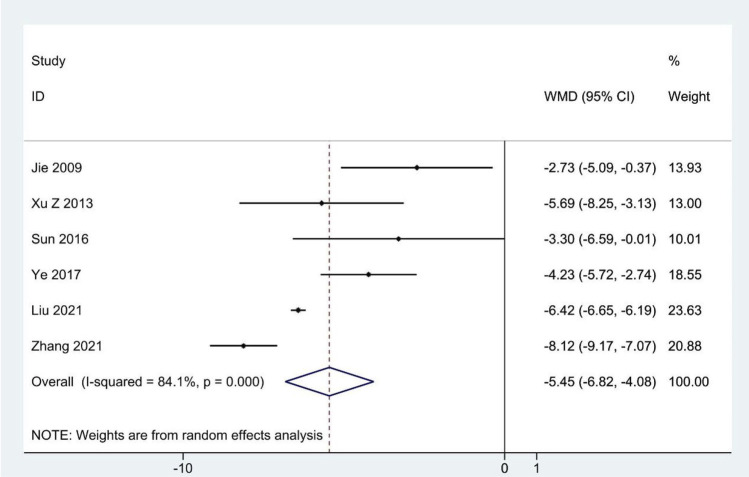

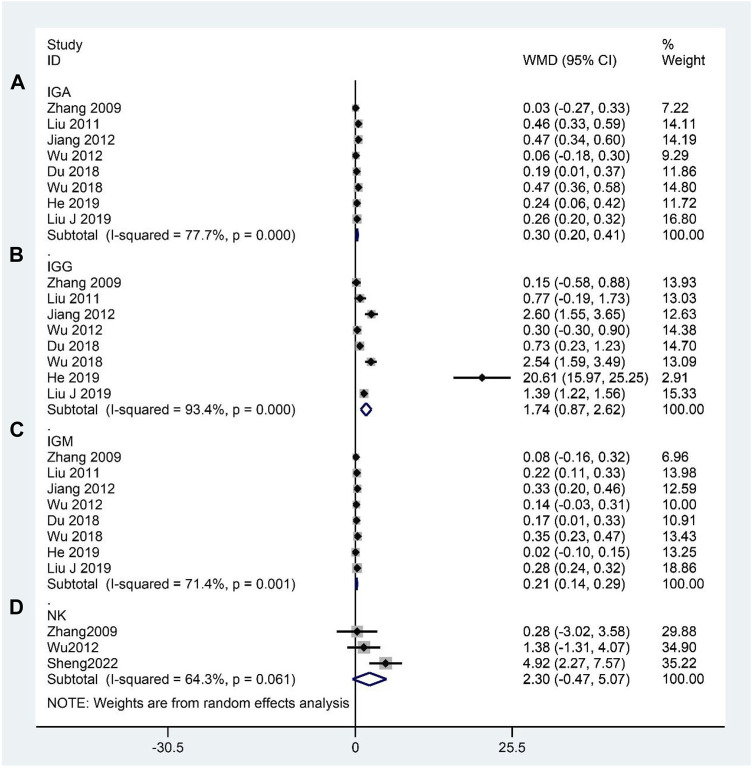

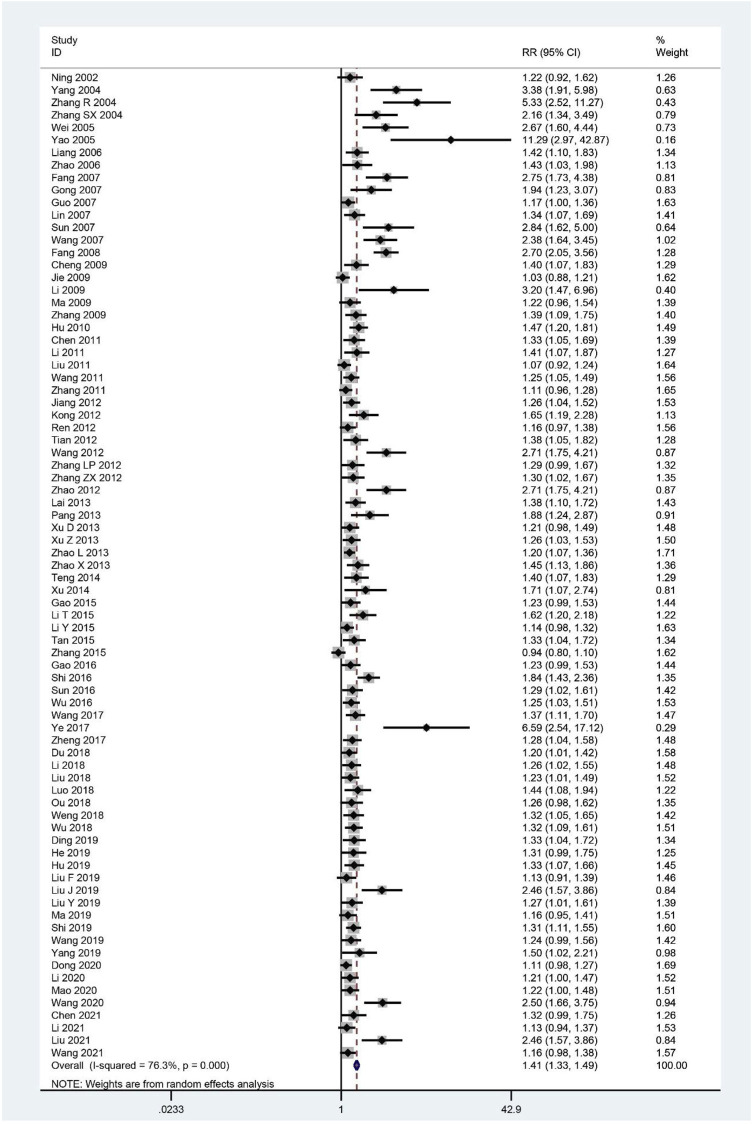

Results: Eighty-four RCTs that explored the efficacy of 69 kinds of Chinese herbal formulas with various dosage forms (decoction, granule, oral liquid, pill, ointment, capsule, and herbal porridge), involving 6,944 participants were identified. This meta-analysis showed that the application of CHM for CFS can decrease Fatigue Scale scores (WMD: –1.77; 95%CI: –1.96 to –1.57; p < 0.001), Fatigue Assessment Instrument scores (WMD: –15.75; 95%CI: –26.89 to –4.61; p < 0.01), Self-Rating Scale of mental state scores (WMD: –9.72; 95%CI:–12.26 to –7.18; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale scores (WMD: –7.07; 95%CI: –9.96 to –4.19; p < 0.001), Self-Rating Depression Scale scores (WMD: –5.45; 95%CI: –6.82 to –4.08; p < 0.001), and clinical symptom scores (WMD: –5.37; 95%CI: –6.13 to –4.60; p < 0.001) and improve IGA (WMD: 0.30; 95%CI: 0.20–0.41; p < 0.001), IGG (WMD: 1.74; 95%CI: 0.87–2.62; p < 0.001), IGM (WMD: 0.21; 95%CI: 0.14–0.29; p < 0.001), and the effective rate (RR = 1.41; 95%CI: 1.33–1.49; p < 0.001). However, natural killer cell levels did not change significantly. The included studies did not report any serious adverse events. In addition, the methodology quality of the included RCTs was generally not high.

Conclusion: Our study showed that CHM seems to be effective and safe in the treatment of CFS. However, given the poor quality of reports from these studies, the results should be interpreted cautiously. More international multi-centered, double-blinded, well-designed, randomized controlled trials are needed in future research.

Systematic Review Registration: [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022319680], identifier [CRD42022319680].

Keywords: herbal medicine, chronic fatigue syndrome, treatment, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a medically unexplained and debilitating mental and physical condition characterized by persistent fatigue (lasting for at least 6 months) and several other symptoms, including sleep disorders, lengthy malaise after exertion, sore throat, muscle pain, multi-joint pain, tender lymph nodes, headache, impairment of concentration or short-term memory, anxiety, and depression, which lead to severe disability and suffering in patients. Studies have shown that the prevalence of CFS is 0.006%–3% in the general population (Cleare et al., 2015), and 836,000–2.5 million people suffer from CFS in the US alone (Clayton, 2015). In addition, a meta-analysis showed that the overall incidence of CFS is 0.77% and 0.76% in Korea and Japan, respectively (Lim and Son, 2021). If there is no effective treatment, CFS will cause a decline in multi-system function and cause systemic diseases such as immune system, circulatory system, nervous system, digestive system, and visceral dysfunction, thus posing a serious threat to human health.

Although the cause of CFS remains uncertain, popular hypotheses include triggers (viral infections, physical trauma, physical and mental stress, vaccinations, and environmental toxins), microbiome disruption, dysregulated immune response, chronic low-grade inflammation, neuroendocrine abnormalities, oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, and genetic predisposition (Brinth et al., 2019; Gregorowski et al., 2019; Noor et al., 2021). These factors can also interact to promote the occurrence and development of CFS. Some studies have suggested that infectious triggers can trigger systemic inflammation by activating the antiviral immune response (Kennedy et al., 2010; Maes et al., 2012; Glassford, 2017; Cortes Rivera et al., 2019). The composition of gut microbes is altered in CFS patients, which might lead to increased intestinal permeability that allows bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, thus increasing systemic inflammation (Deumer et al., 2021). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is impaired in patients with CFS, which may result in neuroendocrine abnormalities and metabolic and inflammatory changes (Deumer et al., 2021). In addition, genetic predisposition is associated with autoimmunity (Deumer et al., 2021).

Currently, the treatment of CFS remains suboptimal because there is a lack of an adequate understanding of the mechanisms and etiology of the disease. Current recommendations for the treatment of CFS include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), graded exercise therapy (GET), western conventional medicine (WCM), complementary or alternative medicine, and nutritional support therapy. CBT challenges patients’ thoughts to relieve patients’ psychological stress, and this may provide short-term benefits but does not permanently reduce symptoms (Fernie et al., 2016; Geraghty and Blease, 2018). Exercise therapy, including aerobic exercises (e.g., walking, jogging, swimming, and cycling) and anaerobic exercises (e.g., strength and stability exercises), could improve physical function and reduce fatigue (Marques et al., 2015; Larun et al., 2017). However, some patients have expressed disappointment with GET because it can interfere with the outcome of alternative treatments and may indirectly exacerbate symptoms in patients (Goudsmit and Howes, 2017; Geraghty and Blease, 2019). Western conventional medicines such as immune modulators, antivirals, antidepressants, antibiotics, and medications to treat specific symptoms that are used for treating CFS have insufficient evidence for their efficacy and may cause serious adverse effects (Mücke et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017). In addition, alternative medicine (e.g., meditation and relaxation response, warm baths, massages, stretching, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, chiropractic, yoga, and Tai Chi), nutritional support therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, physiotherapy, and nerve blocks have all been proposed, but the evidence regarding these treatments is limited and their efficacy is uncertain (Bested and Marshall, 2015; Noor et al., 2021).

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) has been widely used to treat CFS in China and other parts of the world, such as South Korea and Japan (Wang et al., 2014; Joung et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2021). First, according to the dialectical treatment theory of traditional Chinese medicine, specific formulas consisting of different Chinese herbs are used to treat CFS patients with different symptoms. Such treatment tailored to the patient’s specific needs is urgently needed given the obvious heterogeneity in CFS symptoms. The pathogenesis of CFS in traditional Chinese medicine is the deficiency of qi, blood, and yin and yang, accompanied by the stagnation of qi, fire, phlegm, and blood. The treatment is focused on tonifying deficiencies and relieving bruising. CHM such as Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., and Astragalus mongholicus Bunge can nourish deficiency and improve fatigue and lengthy malaise after exertion in CFS patients, whereas Bupleurum falcatum L. and Citrus × aurantium L., among others, can resolve stagnation and relieve pain, insomnia, swollen lymph nodes, and other symptoms. Therefore, CHM can not only improve the main symptoms, but also relieve the accompanying symptoms in CFS. Second, modern pharmacological research has demonstrated that the modern use of CHM in treating CFS mainly focuses on adjusting immune dysfunction, acting as an antioxidant, improving the energy metabolism disorder, and regulating abnormal activity in the HPA axis (Chen et al., 2010; Chi et al., 2016). Buzhong Yiqi decoction, Kuibi decoction, Danggui Buxue decoction, Young Yum pill, and Renshen Yangrong decoction can regulate the immune function of patients with CFS and relieve fatigue symptoms (Ogawa et al., 1992; Shin et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2021; Miao et al., 2022). Ginsenoside, Jujube polysaccharide conjugate, Quercetin, Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal, Hypericum perforatum L., and Ginkgo biloba L. can be antioxidants (Logan and Wong, 2001; Singh et al., 2002; Chi et al., 2015). Schisandra Chinensis Polysaccharide (SCP), HEP2-a extracted from Epimedium brevicornum Maxim., can improve energy metabolism and can regulate the abnormal activity of the HPA axis (Chi et al., 2016; Chi et al., 2017). Additionally, multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported that CHM significantly improves fatigue, insomnia, and other concomitant symptoms; reduces negative emotions such as anxiety and depression; and clearly improves treatment effectiveness and quality of life compared to exercise therapy and alternative therapy (Wang et al., 2011; Kong, 2012; Wang, 2021). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing CHM with western medicine also confirmed the above views (Peng et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). These studies demonstrate the remarkable efficacy and comprehensiveness of CHM for CFS, which is consistent with treatment guidelines emphasizing a holistic, patient-centered approach that considers the patient’s physical, mental, and social well-being (Baker and Shaw, 2007). Finally, CHM has no serious side effects and is relatively safe to treat CFS.

A previous meta-analysis and another systematic review indicated the beneficial role of CHM as a complementary approach for CFS (Peng et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). However, those studies were limited in terms of sample size and outcome indicators because the systematic review only assessed 10 RCTs (including 919 patients), and the meta-analysis of 11 RCTs (including 1,049 patients) only assessed clinical efficacy rates and lacked sufficient evidence. In addition, nearly 50 new trials assessing the effects of CHM for CFS have been published since the previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses were published. Therefore, we conducted a larger systematic review and meta-analysis including more outcome indicators (FS-14, FAI, SCL-90, SAS, SDS, clinical symptom scores, IGA, IGG, IGM, NK cell levels, effective rate, and adverse events) to provide a comprehensive update of previously published studies and stronger evidence for the effectiveness of CHM for CFS.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This meta-analysis was reported in compliance with the PRISMA statement, and the protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022319680). [https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022319680]. The full details of the protocol are available on request.

Search strategy

Electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database, Chinese VIP Database, the US Clinical Trials Registry, and the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry were systematically searched from their inception to May 2022. There was no restriction on language. The search terms used included “Fatigue Syndrome, Chronic”, “CFS”, “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”, “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis”, “ME”, “Encephalomyelitis, Myalgic”, “Chronic Fatigue Disorder”, “Fatigue Disorder, Chronic”, “Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease”, “Chinese herbal medicine”, “Chinese traditional”, “Oriental traditional”, “traditional Chinese medicine”, “traditional Chinese medicinal materials”, “Chinese herb”, “herbal medicine”, “herbal”, “decoction”, “tang”, “pill”, “wan”, “powder”, “formula”, “granule”, “capsule”, “particles”, “ointment”, “prescription”, “receipt”, “placebo”, “random controlled trial”, “random”, and “RCT”. The full details of the search strategy are available (Additional file 1). In addition, we performed manual searches in the reference lists of previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the subject to further look for potentially eligible studies. The search was conducted independently by two authors (YZ and WS).

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

RCTs assessing the efficacy and safety of CHM in the treatment of CFS were included in our review. We only extracted data from the CHM and control groups when we found relevant studies with three treatment groups.

Types of participants

Trials of participants over the age of 16 were included regardless of gender, culture, or setting. CFS was diagnosed using the Center for Disease Control criteria (1987, 1994, or 1998), the Guiding Principles for Clinical Research of New Chinese Medicines (2002), Chinese medicine internal disease diagnosis and treatment routines, the clinical research guidelines for new Chinese medicines for CFS, Chinese internal medicine diagnoses, or the diagnostic efficacy criteria for Chinese medical evidence. All patients had the primary symptom of unexplained fatigue that lasted at least 6 months accompanied by four or more of the following symptoms: unrefreshing sleep, lengthy malaise after exertion, impairment of concentration or short-term memory, sore throat, tender lymph nodes, multi-joint pain, and headaches.

Types of interventions

The formulations of CHM were included. CHM is defined as medicinal raw materials derived from medicinal plants, minerals, and animal sources, according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia edited in 2020 (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2020). A formulation of CHM is usually made up of two or more herbs to produce a synergistic effect on specific illnesses. These materials are prescribed by doctors based on the individual characteristics of the patient according to the dialectical treatment theory of traditional Chinese medicine (Xiong et al., 2019; Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2020).

Participants were treated with CHM alone or combined with WCM, GET, or health guidance. We did not place any limits on the formulation of CHM or the duration of treatment, but CHM was required to be taken orally. We did not include experiments combining Chinese herbal medicine with other traditional Chinese medicine treatments.

Types of controls

Patients in the control group used WCM, GET, health guidance, or placebo, with no limit on the duration of treatment. We did not include experiments combining any Chinese medicine therapy.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were Fatigue Scale (FS-14) and Fatigue Assessment Instrument (FAI) scores. The secondary outcome measures were Self-Rating Scale of mental state (SCL-90) scores, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) scores, Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores, clinical symptom scores, immunological indicators (IGA, IGG, IGM, and NK cell levels), effective rate, and adverse events.

The clinical symptom scores are used to assess the severity of fatigue. The main symptoms and other symptoms of CFS are scored according to their severity, and a higher cumulative score of all symptoms indicates more severe fatigue symptoms. The effective rate is a measure to assess clinical efficacy. It is assessed at the end of treatment using four grades: clinical cure (the patients’ clinical symptoms were basically cured, and they could live and work normally), markedly effective (the cure rate for major and concomitant clinical symptoms up to 2/3), effective (the cure rate for major and concomitant clinical symptoms is 1/3 to 2/3), and invalid (the cure rate for major and concomitant clinical symptoms <1/3).

Study selection

Study selection was performed independently by two authors (YZ and FJ) according to the inclusion criteria. After eliminating duplicates, they independently scanned the title/abstract and full text to identify eligible studies. Any disagreements were settled by a discussion with a third evaluator (WS).

Data extraction

Two investigators (YZ and XW) independently reviewed and extracted the following information: general information (first author, year of publication, region, and types), characteristics of the participants (sample size, age, gender, and course of disease), details of the intervention and the comparison (type of intervention and duration), and outcomes. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussions or adjudication by a third reviewer (YP).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was evaluated independently by two authors (XW and FJ) using the Cochrane collaboration tool with the following seven domains: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other bias. Each domain can be classified as “low-risk,” “high-risk,” or “uncertain risk.” Any differences were resolved by discussion with a third evaluator.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Stata software (version 12.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX). The weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous variables and the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data with 95% confidence intervals (Cl) were used. Heterogeneity was assessed by the Q test and the I2 statistic. When p ≥ 0.10 and I2 ≤ 50%, the fixed-effect model was used; otherwise, the random effects model was used. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The publication bias was assessed by funnel plots and Egger’s test if the number of trials was sufficient. When heterogeneity was detected, the sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the stability of the results by excluding individual studies one by one. Subgroup analysis was performed to explore the sources of heterogeneity according to treatment method (CHM vs. WCM, CHM plus WCM vs. WCM, CHM vs. GET, CHM plus GET vs. GET, CHM vs. health guidance, and CHM vs. placebo) and duration of the intervention (≤30 days vs. 31–60 days vs. > 60 days) based on different treatment methods.

Results

Literature search

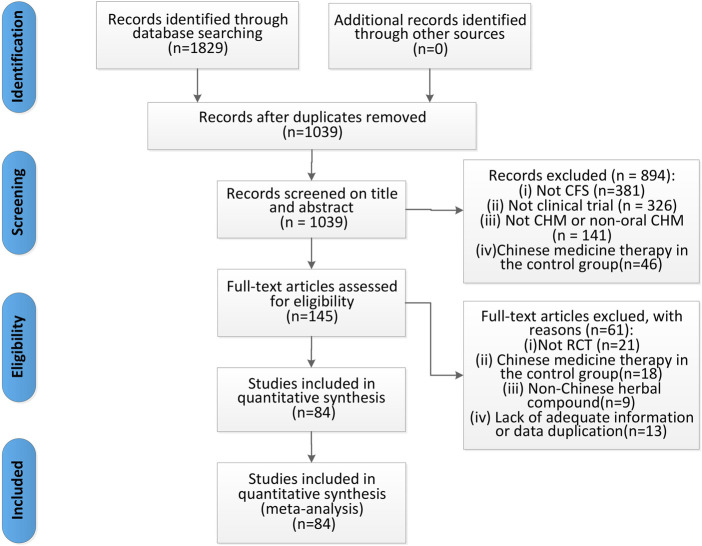

We identified 1,829 articles in the original screening. After eliminating duplicates, 1,039 remained, 894 of which were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria after scanning the titles and abstracts. Moreover, we reviewed the full text of the remaining 145 articles and deleted 61 articles due to the following reasons: 1) non-RCTs, 2) Chinese medicine therapy used in the control group, 3) non-Chinese herbal compounds used, 4) published using repeated data, and 5) missing data. Finally, 84 articles were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the studies selection process.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

A total of 84 RCTs were included, published from 2002 to 2022, and all studies were conducted in China. The sample sizes in the studies varied from 38 to 230 patients, with a total sample size of 3,552 patients in the treatment groups and 3,392 patients in the control groups. The duration of diseases lasted from 0.5 to 24.27 years. Of the 84 studies, five trials (Li, 2009; Liu J. et al., 2019; Wang, 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2022) compared CHM with placebo, whereas comparisons of CHM alone vs. WCM were performed in 63 studies (Ning and Li, 2002; Yang et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Zhang and Zhou, 2004; Wei, 2005; Yao and Qiu, 2005; Liang, 2006; Zhao et al., 2006; Fang et al., 2007; Gong, 2007; Lin, 2007; Sun et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2008; Cheng, 2009; Ma, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang Z. X. et al., 2012; Zhang L. P. et al., 2012; Jiang, 2012; Tian and Wang, 2012; Wang, 2012; Wu et al., 2012; Zhao, 2012; Lai and Lei, 2013; Pang and Liu, 2013; Xu et al., 2013; Zhao, 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; Teng et al., 2014; Xu, 2014; Li, 2015; Li and Zao, 2015; Liu et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Shi and Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Du, 2018; Luo, 2018; Ou et al., 2018; Weng, 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Liu F. et al., 2019; Liu Y. et al., 2019; Ding, 2019; He, 2019; Hu, 2019; Ma et al., 2019; Shi, 2019; Wang, 2019; Yang, 2019; Dong, 2020; Li, 2020; Mao, 2020; Chen, 2021; Zhang, 2021). CHM plus WCM vs. WCM was compared in 12 studies (Guo et al., 2007; Jie and Wang, 2009; Ren and Yu, 2012; Xu and Wang, 2013; Gao and Pang, 2015; Gao and Pang, 2016; Sun et al., 2016; Wang, 2017; Zheng et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Liu and Cai, 2018; Li et al., 2021); CHM vs. GET was compared in one study (Wang, 2021); CHM plus GET vs. GET was compared in two studies (Wang et al., 2011; Kong, 2012); and CHM vs. health guidance was compared in one study (Ye, 2017). The course of treatment ranged from 7 to 120 days. In the outcome indicators, 26 studies (Jie and Wang, 2009; Chen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang L. P. et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013; Xu and Wang, 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Ye, 2017; Zheng et al., 2017; Du, 2018; Luo, 2018; Liu F. et al., 2019; Liu J. et al., 2019; He, 2019; Shi, 2019; Mao, 2020; Wang, 2020; Chen, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Wang, 2021) reported FS-14 scores; nine studies (Zhao et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2015; Luo, 2018; Wang, 2019; Li et al., 2021; Wang, 2021) reported FAI scores; five studies (Zhang et al., 2009; Zhang Z. X. et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012; Niu et al., 2015; Sheng et al., 2022) reported SCL-90 scores; seven studies (Jie and Wang, 2009; Xu and Wang, 2013; Sun et al., 2016; Ye, 2017; Yang, 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang, 2021) reported SAS scores; six studies (Jie and Wang, 2009; Xu and Wang, 2013; Sun et al., 2016; Ye, 2017; Liu et al., 2021; Zhang, 2021) reported SDS scores; 24 studies (Zhang et al., 2004; Yao and Qiu, 2005; Fang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2008; Li, 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Wang, 2012; Zhao, 2012; Li, 2015; Li and Zao, 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Ye, 2017; Du, 2018; Liu and Cai, 2018; Luo, 2018; Liu J. et al., 2019; He, 2019; Hu, 2019; Shi, 2019; Dong, 2020; Wang, 2020; Liu et al., 2021) reported clinical symptom scores; eight studies (Zhang et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2011; Jiang, 2012; Wu et al., 2012; Du, 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Liu J. et al., 2019; He, 2019) reported the level of IGA, IGG, and IGM; three studies (Zhang et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2012; Sheng et al., 2022) reported the NK cell levels; and 79 studies (Ning and Li, 2002; Yang et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2004; Zhang and Zhou, 2004; Wei, 2005; Yao and Qiu, 2005; Liang, 2006; Zhao et al., 2006; Fang et al., 2007; Gong, 2007; Guo et al., 2007; Lin, 2007; Sun et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Fang et al., 2008; Cheng, 2009; Jie and Wang, 2009; Li, 2009; Ma, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Jiang, 2012; Kong, 2012; Ren and Yu, 2012; Tian and Wang, 2012; Wang, 2012; Zhang Z. X. et al., 2012; Zhang L. P. et al., 2012; Zhao, 2012; Lai and Lei, 2013; Pang and Liu, 2013; Xu et al., 2013; Xu and Wang, 2013; Zhao, 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; Teng et al., 2014; Xu, 2014; Gao and Pang, 2015; Li and Zao, 2015; Li, 2015; Tan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Gao and Pang, 2016; Shi and Wu, 2016; Sun et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Wang, 2017; Ye, 2017; Zheng et al., 2017; Du, 2018; Li et al., 2018; Liu and Cai, 2018; Ou et al., 2018; Weng, 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Luo, 2018; Ding, 2019; He, 2019; Hu, 2019; Liu F. et al., 2019; Liu J. et al., 2019; Liu Y. et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2019; Shi, 2019; Wang, 2019; Yang, 2019; Dong, 2020; Li, 2020; Mao, 2020; Wang, 2020; Chen, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Wang, 2021) reported effective rate. The occurrence of adverse effects was reported in 14 studies (Liang, 2006; Gong, 2007; Lin, 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Jie and Wang, 2009; Li, 2009; Li et al., 2011; Xu and Wang, 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Ye, 2017; Li et al., 2018; Liu and Cai, 2018). The basic characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1, and components of CHM used in the included studies are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Region | Types | Sample size (TG/CG) | Age (Y) | Gender (M/F) | Course of disease | Interventions | Duration (days) | Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | CG | TG | CG | TG | CG | TG | CG | ||||||

| Ning and Li (2002) | China | RCT | 43 (23/20) | 42 | 41 | 7/16 | 5/15 | 0.5–5 years | 0.5–5 years | Sijunzi decoction (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol + antipsychotic + vitamin | 30 | ⑪ |

| Yang et al. (2004) | China | RCT | 72 (38/34) | 36.4 | 36.4 | NR | NR | 2.5 years | 2.5 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction (qd) | ATP (2 tablets, tid) | 30 | ⑪ |

| Zhang et al. (2004) | China | RCT | 100 (60/40) | 36.2 ± 7.82 | 34.92 ± 10.28 | 26/34 | 18/22 | 0.5–5 years | 0.5–5 years | Self-designed Shenqi Fuyuan decoction (200 ml, bid) | Oryzanol + multivitamin | 30 | ⑥⑪ |

| Zhang and Zhou (2004) | China | RCT | 68 (40/28) | 37 | 37 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Buzhong Yiqi decoction | Vitamins B, B1, B6 + oryzanol + estazolam + ibuprofen sustained release capsule | 42 | ⑪ |

| Wei (2005) | China | RCT | 72 (37/35) | 29.5 | 28.9 | 12/25 | 10/25 | 2.5 years | 2.4 years | Xiaochaihu decoction (1 package, bid) | Vitamin C (bid) + vitamin B (bid) + diclofenac sodium (25 mg) | 21 | ⑪ |

| Yao and Qiu (2005) | China | RCT | 56 (31/25) | 36.2 ± 7.82 | 35.92 ± 10.28 | 10/21 | 10/15 | 0.6–5 years | 0.6–5 years | Self-designed Xianshen decoction (200 ml, bid) | Centrum vitaminamin A–Z (1 granule, qd) | 30 | ⑥⑪ |

| Liang (2006) | China | RCT | 121 (63/58) | 37.2 | 35.3 | 36/27 | 34/24 | 0.58–6 years | 0.67–8 years | Shengmai pulvis and Xuefu Zhuyu decoction (200 ml, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g, tid) + vitamin B (0.2 g, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 28 | ⑪⑫ |

| Zhao et al. (2006) | China | RCT | 58 (30/28) | 44 | 43 | 11/19 | 11/17 | 1.8 a | 1.6 a | Yiqi Yangyin Jichu prescription (tid) | ATP (40 mg, tid) + vitamin C (0.2 g, tid) | 90 | ②⑪ |

| Fang et al. (2007) | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | 42.15 ± 9.31 | 42.15 ± 9.31 | NR | NR | 16.58 ± 7.69 years | 16.58 ± 7.69 years | Xiaopiling granule (20 g, tid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 28 | ⑥⑪ |

| Gong (2007) | China | RCT | 58 (30/28) | 36.3 | 36.8 | 10/20 | 12/16 | 0.5–5 years | 0.5–5 years | Guipi decoction (200 ml, bid) | ATP (40 mg, tid) | 45 | ⑪⑫ |

| Guo et al. (2007) | China | RCT | 120 (60/60) | 51.07 ± 7.57 | 49.75 ± 7.78 | 29/31 | 32/28 | 2.63 ± 1.16 years | 2.65 ± 1.39 years | Qi and blood proral solution (1 package, 10 ml, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 30 | ⑪ |

| Lin (2007) | China | RCT | 88 (50/38) | 28–60 | 25–65 | 15/35 | 21/17 | 1–6 years | 0.7–5 years | Shenling Baizhu powder (60–90 g, bid/tid) | Oryzanol + vitamin B1 + vitamin B6 + deanxit + amino acid | 56 | ⑪⑫ |

| Sun et al. (2007) | China | RCT | 64 (34/30) | 35.8 | 35.8 | NR | NR | 2.2 a | 2.2 a | Shuyu decoction (200 ml, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g, tid) + vitamin B (0.2 g, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 40 | ⑪ |

| Wang et al. (2007) | China | RCT | 105 (53/52) | 41.37 ± 8.52 | 41.37 ± 8.52 | NR | NR | 17.51 ± 6.39 m | 17.51 ± 6.39 m | Fuzheng Jieyu prescription (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + ATP (40 mg, tid) | 28 | ⑥⑪⑫ |

| Fang et al. (2008) | China | RCT | 230 (120/110) | 40 | 40 | NR | NR | 2.5 years | 2.5 years | Fufang Shenqi ointment (10 g, bid) | ATP (3 tablets, tid) + vitamin C (2 tablets, tid) | 60 | ⑥⑪ |

| Cheng (2009) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | NR | NR | 13/17 | 12/18 | 0.5–2 years | 0.4–2 years | Bainian Le oral liquid (15 ml, bid) | Vitamin B solution (15 ml, bid) | 14 | ⑪ |

| Jie and Wang (2009) | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | 34.55 ± 7.45 | 33.95 ± 6.54 | 14/21 | 16/19 | 14.50 ± 4.50 m | 14.20 ± 4.15 m | Xiaoyao pill (24 pills, tid) + Paroxetine (20–40 mg/d) | Paroxetine (20–40 mg/d) | 56 | ①④⑤⑪⑫ |

| Li (2009) | China | RCT | 38 (19/19) | 32.75 | 31.45 | 6/13 | 12/7 | 0.5–10 years | 0.5–10 years | Anti-fatigue no. 2 decoction granule (tid) | Placebo (tid) | 21 | ⑥⑪⑫ |

| Ma (2009) | China | RCT | 118 (78/40) | 52.5 | 50.2 | 35/43 | 18/22 | NR | NR | Guipi decoction (150 ml, tid) | Vitamin (2 tablets, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + estazolam (1–2 mg, qn) + nimesulide (0.1 g, bid) | 30 | ⑪ |

| Zhang et al. (2009) | China | RCT | 75 (40/35) | 38.63 ± 11.49 | 38.66 ± 10.94 | 19/21 | 14/21 | 10.95 ± 3.73 m | 10.80 ± 2.95 m | Lixu Jieyu prescription (200 ml, bid) | Vitaeamphor (10 mg, bid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 90 | ②③⑦⑧⑨⑩⑪ |

| Hu et al. (2010) | China | RCT | 120 (60/60) | 41.23 | 41.23 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Buqi Tongluo prescription (1 package, tid) | Vitamin B complex (5 ml, tid) | NR | ⑥⑪ |

| Chen et al. (2011) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 44.7 ± 5.6 | 47.4 ± 3.4 | 16/24 | 18/22 | 0.5–4 years | 0.5–3.5 years | Qixue Liangxu prescription + Ganyu Pixu prescription + Ganshen Kuixu prescription | Multidimensional tablet (10 mg, bid) + meloxicam (1 tablet, qd) + estazolam tablet (1 mg, qd) + flupentixton melitoxin (1 tablet, bid) | 90 | ①⑪ |

| Li et al. (2011) | China | RCT | 71 (36/35) | 38.36 ± 7.16 | 39.22 ± 6.85 | 16/20 | 17/18 | 0.5–3 years | 0.6–3 years | Chaihu Shugan pulvis and Guipi decoction (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) | 56 | ①⑪⑫ |

| Liu et al. (2011) | China | RCT | 80 (42/38) | 42.3 ± 10.6 | 41.2 ± 9.5 | 20/22 | 19/19 | 0.5–3 years | 0.67–3 years | Shugan Yangxue prescription (1 package, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g) + vitamin B (0.2 g) + ATP (20 mg) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 56 | ①②⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Wang et al. (2011) | China | RCT | 96 (48/48) | 39 | 38.5 | 27/21 | 25/23 | 5 years | 5 years | Yiqi Ziyin Buyang prescription (300 ml, bid) + GET | GET | 60 | ⑪ |

| Zhang et al. (2011) | China | RCT | 64 (32/32) | 37.97 ± 10.35 | 38.66 ± 11.03 | 15/17 | 14/18 | 11.30 ± 4.73 m | 10.98 ± 4.26 m | Zhenqi Jiepi decoction (100 ml, bid) | Gold theragran (1 tablet, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 60 | ①⑪ |

| Jiang (2012) | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | 37 | 38 | 17/18 | 18/17 | 0.67 years | 1.67 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Guipi decoction (1 package, bid) | Vitamin C + vitamin B complex + oryzanol | 56 | ⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Kong (2012) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.5–3 years | 0.5–3 years | Self-designed anti-fatigue decoction (200 ml, tid) + GET | GET | 45 | ⑪ |

| Ren and Yu. (2012) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 42 | 44 | 22/18 | 24/16 | 5 a | 5.6 a | Self-designed Zhongyao Buxu decoction (1 package) + oryzanol (2 tablets, tid) | Oryzanol (2 tablets, tid) | 21 | ⑪ |

| Tian and Wang. (2012) | China | RCT | 64 (32/32) | 28–60 | 25–65 | 15/17 | 21/11 | 1–6 years | 0.6–3 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol + vitamin B1 + vitamin B6 + deanxit + amino acid | 56 | ⑪ |

| Wang. (2012) | China | RCT | 84 (42/42) | 40.65 ± 12.25 | 40.65 ± 12.25 | NR | NR | 2.14士1.07 years | 2.14士1.07 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | ATP (2 tablets, tid) | 28 | ⑥⑪ |

| Wu et al. (2012) | China | RCT | 120 (60/60) | NR | NR | 24/36 | 22/38 | ≥6 m | ≥6 m | Lixu Jieyu prescription (150 ml, bid) | Vitaeamphor (1 tablet, tid) + ATP (20 mg, bid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 84 | ②③⑦⑧⑨⑩ |

| Zhang et al. (2012a) | China | RCT | 66 (33/33) | 38.74 ± 11.39 | 39.45 ± 10.97 | NR | NR | 10.94 ± 3.72 years | 10.81 ± 2.97 years | Lixu Jieyu prescription (200 ml, bid) | Vitaeamphor (10 mg, bid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 84 | ③⑪ |

| Zhang et al. (2012b) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 37.16+-9.93 | 37.77+-11.48 | 13/17 | 12/18 | 12.52 ± 5.18 m | 13.35 ± 5.17 m | Yaoyao Xiaopi prescription (100 ml, bid) | Gold theragran (1 tablet, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 60 | ①⑪ |

| Zhao. (2012) | China | RCT | 84 (42/42) | 40.65 ± 12.25 | 40.65 ± 12.25 | NR | NR | 2.14 ± 1.07 years | 2.14 ± 1.07 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | ATP (2 tablets, tid) | NR | ⑥⑪ |

| Lai and Lei. (2013) | China | RCT | 68 (34/34) | 46.8 | 47.6 | 15/19 | 14/20 | 0.6–3 years | 0.5–3.5 years | Baiyu Jianpi decoction (200 ml, bid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) | 56 | ⑪ |

| Pang and Liu. (2013) | China | RCT | 60 (32/28) | 28–53 | 24–55 | 9/23 | 11/17 | 0.5–4 years | 0.58- y | Shengmai pulvis and Xiaoyao pulvis | Vitamin C (0.2 g, tid) + vitamin Bco (2 tablets, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 28 | ⑪ |

| Xu et al. (2013) | China | RCT | 68 (40/28) | 33.24 ± 1.56 | 30.24 ± 1.28 | 22/18 | 16/12 | 24.24 ± 4.30 m | 22.20 ± 3.24 m | Jiawei Naoxin Kang (100 ml, bid) | ATP (1 tablet, bid) | 10 | ①⑪ |

| Xu and Wang. (2013) | China | RCT | 84 (42/42) | 35.29 ± 6.18 | 34.87 ± 7.08 | 17/25 | 19/23 | 15.06 ± 4.80 m | 14.75 ± 5.02 m | Chaihu Jia Longgu Muli decoction (200 ml, bid) + paroxetine (20–40 mg/d) | Paroxetine (20–40 mg/d) | NR | ①④⑤⑪⑫ |

| Zhao (2013) | China | RCT | 176 (88/88) | 52.5 | 50.2 | 35/53 | 29/59 | ≥6 m | ≥6 m | Self-designed Baihe Yangxin Jianpi decoction (175 ml, bid) | Vitamina (NR) + oryzanol (NR) + vitamin B (NR) | NR | ⑪ |

| Zhao et al. (2013) | China | RCT | 90 (45/45) | 36.5 | 35.6 | NR | NR | 9.35 ± 2.13 m | 9.05 ± 3.13 m | Compound of Fufangteng mixture (15 ml, bid) | Vitaeamphor (10 mg, bid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 90 | ⑪ |

| Teng et al. (2014) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 43 | 43 | 12/18 | 11/19 | 2.4 years | 2.7 years | Buzhong JiePi decoction (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol (10 mg, tid) + vitamin B1 tablet (10 mg, tid) | 56 | ⑪ |

| Xu (2014) | China | RCT | 63 (32/31) | NR | NR | 18/14 | 16/15 | NR | NR | Qingshu Yiqi decoction (1 package) | Oryzanol diazepam tablet (NR) + poly methamphetamine tablet (NR) | 7 | ⑪ |

| Gao and Pang. (2015) | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | 32.8 ± 10.5 | 33.6 ± 12.7 | 12/23 | 15/20 | 0.75–4 years | 0.7–4.2 years | Wendan decoction and Sini decoction (1 dose/d, bid) + fluoxetine hydrochloride capsules (20–40 mg, qod) | Fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20–40 mg, qod) | 28 | ⑪ |

| Li and Zao. (2015) | China | RCT | 74 (37/37) | 55.3 ± 6.2 | 54.7 ± 6.9 | NR | NR | ≥6 m | ≥6 m | Jianpi Wenshen Shugan prescription (1 dose/d, tid) | Multivitamin tablet (1 tablet, tid) + oryzanol (1 tablet, tid) | 30 | ⑥⑪ |

| Liu et al. (2015) | China | RCT | 100 (51/49) | 43.2 ± 12.6 | 42.6 ± 10.5 | 20/31 | 19/30 | 0.5–3 years | 0.8–3 years | Shugan Yangxue decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g, tid) + vitamin B (0.2 g, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 42 | ①② |

| Li (2015) | China | RCT | 68 (34/34) | 41.3 ± 2.3 | 42.3 ± 2.4 | 18/16 | 19/15 | 2.4 ± 1.1 y | 2.5 ± 1.2 years | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | ATP (2 tablets, tid) | 28 | ⑥⑪ |

| Niu et al. (2015) | China | RCT | 132 (66/66) | 44.18 ± 8.66 | 46.34 ± 9.39 | 26/40 | 22/44 | ≥6 m | ≥6 m | Bushen Shugan decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | ATP (20 mg, bid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 56 | ①③ |

| Tan et al. (2015) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 35.6 ± 9.7 | 35.0 ± 10.4 | 14/16 | 13/17 | 1.4 ± 0.7 years | 1.1 ± 0.5 years | Sini decoction and Wulin powder (1 dose/d, 100 ml, bid) | Vitamin B1 tablet (10 mg, tid) + vitamin B6 tablet (20 mg, tid) + oryzanol tablet (20 mg, tid) | 28 | ①⑪ |

| Zhang et al. (2015) | China | RCT | 172 (88/84) | 32 ± 6.38 | 33 ± 7.26 | 34/54 | 31/53 | NR | NR | Wenzhen Yunqi prescription (1 package, bid) | Deanxit (2 tablets, bid) | NR | ①⑪⑫ |

| Gao and Pang. (2016) | China | RCT | 70 (35/35) | 32.8 ± 10.5 | 33.6 ± 12.7 | 12/23 | 15/20 | 0.75–4 years | 0.7–4.2 years | Wendan decoction and Sini powder (1 dose/d, 150 ml, bid) + fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20–40 mg, qod) | Fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20–40 mg, qod) | 28 | ⑪ |

| Shi and Wu. (2016) | China | RCT | 120 (60/60) | 45.25 ± 9.81 | 43.14 ± 8.35 | 22/38 | 25/35 | 1.20 ± 0.45 years | 1.15 ± 0.50 years | Suanzaoren decoction (1 dose/d) | Oryzanol (30 mg, tid) | 14 | ⑪ |

| Sun et al. (2016) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 36.58 ± 5.48 | 36.87 ± 6.58 | NR | NR | 18.56 ± 6.45 m | 17.75 ± 5.92 m | Shugan Yiyang capsule (0.75 g, tid) + paroxetine hydrochloride tablets (20 mg, 1 dose/d) | Paroxetine hydrochloride tablet (20 mg, 1 dose/d) | NR | ④⑤⑥⑪⑫ |

| Wu et al. (2016) | China | RCT | 80 (42/38) | 40.15 ± 8.51 | 41.46 ± 7.94 | 28/14 | 25/13 | 1.32 ± 0.67 years | 1.28 ± 0.59 years | Xiaopi Yin (1 dose/d, 200 ml, tid) | Vitamin B6 (2 tablets, 1 dose/d) | 42 | ⑥⑪⑫ |

| Wang (2017) | China | RCT | 140 (70/70) | 42.47 ± 12.46 | 42.33 ± 17.40 | 38/32 | 39/31 | 12.63 ± 4.11 m | 12.78 ± 4.24 m | Bupi Yishen decoction (1 dose/d, bid) + ATP (60 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | ATP (60 mg, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 30 | ⑪ |

| Ye (2017) | China | RCT | 76 (37/39) | 40.19 ± 8.05 | 37.67 ± 7.30 | 12/25 | 9/30 | 13.46 ± 4.25 m | 15.13 ± 4.60 m | Shenxian congee (1 dose/d, qd) + health guidance | Health guidance | 56 | ①④⑤⑥⑪⑫ |

| Zheng et al. (2017) | China | RCT | 90 (45/45) | 35.8 ± 7.6 | 34.9 ± 8.1 | 21/24 | 18/27 | 15.4 ± 3.8 m | 16.2 ± 3.5 m | Shugan Jianpi Yishen prescription (1 dose/d, bid) + paroxetine hydrochloride tablet (20 mg, qd) | Paroxetine hydrochloride tablet (20 mg, qd) | 56 | ①⑪ |

| Du (2018) | China | RCT | 108 (54/54) | 40.59 ± 5.60 | 40.64 ± 5.81 | 26/29 | 26/28 | 2.08 ± 0.57 years | 2.10 ± 0.5 years | Self-designed Yishen Buxue ointment (150–200 ml, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g, tid) + vitamin B (0.2 g, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) | 42 | ①⑥⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Li et al. (2018) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 42.65 ± 8.42 | 42.12 ± 7.86 | 18/12 | 17/13 | 2.26 ± 0.67 years | 2.12 ± 0.76 years | Yiqi Yangxue Bupi Hegan prescription (150 ml, bid) + paroxetine hydrochloride tablet (20–40 mg, 1 dose/d) | Paroxetine hydrochloride tablet (20–40 mg, 1 dose/d) | 15 | ⑪⑫ |

| Liu and Cai. (2018) | China | RCT | 82 (41/41) | 34.65 ± 6.98 | 32.99 ± 6.47 | 17/24 | 15/26 | 14.24 ± 4.66 m | 16.01 ± 5.23 m | Bupiwei Xieyinhuo Shengyang decoction (1 dose/d, bid) + fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20 mg, qd) | Fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20 mg, qd) | 28 | ⑥⑪⑫ |

| Ou et al. (2018) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 50.3 ± 11.35 | 49.8 ± 10.45 | 18/22 | 19/21 | 2–5 years | 2–6 years | Guipi decoction Jiawei (1 dose/d, bid) | Fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20–40 mg, qod) | 90 | ⑪ |

| Weng (2018) | China | RCT | 150 (75/75) | 40.9 ± 8.9 | 41.7 ± 9.2 | 28/47 | 26/49 | ≥6 m | ≥6 m | Liujunzi decoction | Oryzanol (10–20 mg, tid) + Vitamin B1 (20 mg, tid) | 90 | ⑪ |

| Wu et al. (2018) | China | RCT | 86 (43/43) | 39.7 ± 6.9 | 40.3 ± 7.5 | 16/27 | 18/25 | 0.5–5 years | 0.5–7 years | Guipi decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Vitamin C + Vitamin B | 84 | ⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Luo (2018) | China | RCT | 56 (28/28) | 28.14 | 28.86 | 15/13 | 14/14 | NR | NR | Qingre Qushi prescription (1 package, bid) | Oryzanol tablet (2 tablets, tid) + multivitamin B tablet (2 tablets, tid) | 14 | ①②⑥⑪ |

| Ding (2019) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 39.21 ± 1.25 | 41.15 ± 1.29 | 15/15 | 16/14 | NR | NR | Guipi decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Vitamin C + vitamin B | 84 | ⑪ |

| He (2019) | China | RCT | 65 (33/32) | 33.84 ± 4.98 | 33.70 ± 4.02 | 9/23 | 8/22 | 12.66 ± 3.16 m | 12.57 ± 3.35 m | Shugan Jianpi Huoxue prescription (1 dose/d, bid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 28 | ①⑥⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Hu (2019) | China | RCT | 66 (33/33) | 55.14 ± 1.26 | 55.11 ± 1.22 | 16/17 | 17/16 | 3.15 ± 1.14 years | 3.11 ± 1.11 years | Buzhong Yiqi and Xiaochaihu decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | ATP (2 tablets, tid) | NR | ⑥⑪ |

| Liu et al. (2019a) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 42 | 42 | NR | NR | 1 year | 1 year | Jiawei Lingzhi pill (1 dose/d, bid) | Fluoxetine tablet (20 mg, qd) | 30 | ①⑪ |

| Liu et al. (2019b) | China | RCT | 72 (36/36) | NR | NR | 9/27 | 11/25 | 0.58–2 years | 0.58–2.2 years | Chaihu Guizhi decoction grain (1 package, bid) | placebo (1 package, bid) | 28 | ①⑥⑦⑧⑨⑪ |

| Liu et al. (2019c) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 43.3 ± 12.6 | 42.9 ± 10.6 | 10/20 | 11/19 | 15.0 ± 5.6 m | 16.0 ± 6.3 m | Jianpi Yishen decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Vitamin C (0.1 g, tid) + vitamin B (0.2 g, tid) + vitamin E (0.1 g, tid) | 42 | ⑪ |

| Ma et al. (2019) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 45.2 | 43 | 12/28 | 10/30 | NR | NR | Self-designed Jiawei Erxian decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Vitamin B1 (20 mg) + oryzanol (20 mg) + Bailemen (4 tablets, tid) | 60 | ⑪ |

| Shi (2019) | China | RCT | 160 (78/82) | 41.51 ± 9.347 | 40.55 ± 9.775 | 35/43 | 32/50 | 0.9–3 years | 0.7–2 years | Xiaoyao pulvis Jiawei (1 dose/d, bid) | Multivitamin B tablet (2 tablets, tid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 21 | ①⑥⑪ |

| Wang (2019) | China | RCT | 69 (35/34) | 34.67 | 35.34 | 18/17 | 19/15 | NR | NR | Sanren decoction and Sijunzi decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + multivitamin B tablet (20 mg, tid) | 14 | ②⑪ |

| Yang (2019) | China | RCT | 40 (20/20) | 38.45 ± 5.36 | 39.12 ± 5.21 | 11/9 | 10/10 | 0.5–1.5 years | 0.5–1.5 years | Zuogui pill (9 g, bid) | Symptomatic treatment + anti-virus + improve immunity + anti-depression + psychotherapy | 120 | ④⑪ |

| Dong (2020) | China | RCT | 80 (40/40) | 37.68 ± 3.41 | 37.72 ± 3.34 | 26/14 | 23/17 | 1.24 ± 0.17 years | 1.21 ± 0.15 years | Qingshu Yiqi decoction grain (200 ml, bid) | Nuodikang capsule (2 tablets, tid) | 90 | ⑥⑪ |

| Li (2020) | China | RCT | 72 (36/36) | 37.82 ± 6.03 | 39.11 ± 5.94 | 19/17 | 21/15 | NR | NR | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | ATP (40 mg, tid) | 30 | ⑪ |

| Mao (2020) | China | RCT | 59 (30/29) | 39.58 ± 0.46 | 39.40 ± 0.37 | 17/13 | 18/11 | 1.26 ± 0.38 years | 1.37 ± 0.22 years | Yishen Tiaodu method (1 dose/d, qod) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) | 56 | ①⑪ |

| Wang (2020) | China | RCT | 90 (45/45) | 47.5 ± 7.3 | 48.1 ± 7.6 | 16/29 | 17/28 | 17.2 ± 3.5 m | 17.7 ± 3.8 m | Chaihu Guizhi decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Placebo (12 g, bid) | 28 | ①⑥⑪ |

| Chen (2021) | China | RCT | 63 (33/30) | 33.8 ± 13.1 | 33.6 ± 13.2 | 15/18 | 14/16 | 18.51 ± 9.03 m | 16.32 ± 8.94 m | Xiaoyao powder (1 dose/d, bid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + vitamin B1 (20 mg, tid) + ATP (20 mg, tid) | 60 | ①⑪ |

| Li et al. (2021) | China | RCT | 79 (40/39) | 41.60 ± 9.29 | 39.51 ± 9.79 | 22/18 | 19/20 | 10.98 ± 3.03 m | 11.49 ± 3.60 m | Jiannao Yizhi ointment (bid) + oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + vitamin B1 (10 mg, tid) | Oryzanol (20 mg, tid) + vitamin B1 (10 mg, tid) | 56 | ①②⑪ |

| Liu et al. (2021) | China | RCT | 72 (36/36) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Chaihu Guizhi decoction grain (1 package, bid) | Placebo (1 package, bid) | 28 | ①④⑤⑥⑪ |

| Wang (2021) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 40.06 ± 11.51 | 41.23 ± 8.47 | 10/20 | 12/18 | NR | NR | Shenling Baizhu powder (1 dose/d, bid) | GET | 30 | ①②⑪ |

| Zhang (2021) | China | RCT | 60 (30/30) | 45.2 ± 3.1 | 46.8 ± 3.4 | 14/16 | 16/14 | NR | NR | Jiawei Guizhi Xinjia decoction (1 dose/d, bid) | Fluoxetine hydrochloride capsule (20–60 mg, qd) | 84 | ④⑤ |

| Sheng et al. (2022) | China | RCT | 69 (35/34) | NR | NR | 16/19 | 14/20 | NR | NR | Wenshen Lipi prescription (1 package, bid) | Placebo (1 package, bid) | 28 | ③⑩ |

RCT: randomized controlled trial; TG: trial group; CG: control group; F: female; M: male; NR: not reported; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; Y: year; GET: graded exercise therapy; ①: Fatigue Scale scores; ②: Fatigue Assessment Instrument scores; ③: Self-Rating Scale of mental state scores; ④: Self-Rating Anxiety Scale scores; ⑤: Self-Rating Depression Scale scores; ⑥: clinical symptom scores; ⑦: Immunoglobulin A; ⑧: Immunoglobulin G; ⑨: Immunoglobulin M; ⑩: natural killer cell level; ⑪: effective rate; ⑫: adverse events.

TABLE 2.

Components of Chinese herbal medicine used in the included studies.

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ning and Li. (2002) | Sijunzi decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 12 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20 g, Acorusgramineus Aiton 10 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 10 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 10 g | Decoction |

| Yang et al. (2004) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 25 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 25 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 20 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 20 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 12 g | Granule |

| Zhang et al. (2004) | Self-designed Shenqi Fuyuan decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Actaea cimicifuga L., Bupleurum falcatum L., Citrus × aurantium L., Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Decoction |

| Zhang and Zhou. (2004) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 9 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 9 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 9 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 9 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 9 g, Spatholobus suberectus Dunn 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 2 g | Decoction |

| Wei (2005) | Xiaochaihu decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 12 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 10 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 5 pieces | Decoction |

| Yao and Qiu. (2005) | Self-designed Xianshen decoction | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 12 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 30 g, Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F.H.Chen 6 g | Decoction |

| Liang (2006) | Shengmai pulvis and Xuefu Zhuyu decoction | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 12 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Kergawl. 15 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 20 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 8 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 6 g, Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch 10 g, Carthamus tinctorius L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 8 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 15 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 20 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Zhao et al. (2006) | Yiqi Yangyin Jichu prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20 g, Pseudostellaria Heterophylla (Miq.) Pax 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 20 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 10 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Kergawl. 15 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 15 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 20 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 10 g | Decoction |

| Fang et al. (2007) | Xiaopiling granule | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Equus Asinus L., Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Kergawl., Dimocarpus Longan Lour., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss. ex Fr.) Karst., Ziziphi Spinosae Semen, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill., Crataegus Pinnatifida Bunge, Spatholobus suberectus Dunn | Granule |

| Gong (2007) | Guipi decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Polygala tenuifolia Willd., Dimocarpus Longan Lour., Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill., Ziziphi Spinosae Semen, Matricaria Chamomilla L., Strobilanthes Cusia (Nees) Kuntze, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Decoction |

| Guo et al. (2007) | Qi and Blood Proral Solution | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Epimedium brevicornum Maxim., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Lycium chinense Mill., Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Curculigo Orchioidesgaertn., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | Oral liquids |

| Lin (2007) | Shenling Baizhu powder | Pseudostellaria Heterophylla (Miq.) Pax 90 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 90 g, Euryale Ferox Salisb. 90 g, Nelumbo Nuciferagaertn. 90 g, Lablab Purpureus Subsp. Purpureus 90 g, glycine Max (L.) Merr. 90 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 90 g, Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. 90 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 150 g, Coix lacryma-jobi L. 60 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 60 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 40 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 25 g, Placenta Hominis 50 g, Ligustrum Lucidum W.T.Aiton 50 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 50 g, Oryza sativa L. 1250 g | Decoction |

| Sun et al. (2007) | Shuyu decoction | Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. 30 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 10 g, Triticum aestivum L. 30 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 30 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 20 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g, Albiziae Cortex 30 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g | Decoction |

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (2007) | Fuzheng Jieyu prescription | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 6 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 12 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 5 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 8 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 5 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 12 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 12 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 12 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 9 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 12 g, Cervus nippon Temminck 12 g, Colla Carapacis et Plastri Testudinis 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 6 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 9 g, Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 6 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 6 g, Hyssopus officinalis L. 9 g, gardenia Jasminoides J.Ellis 6 g | Decoction |

| Fang et al. (2008) | Fufang Shenqi ointment | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong,” Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Curcuma aromatica Salisb., Bupleurum falcatum L. | Ointment |

| Cheng (2009) | Bainian Le oral liquid | Euonymus fortunei var. fortunei, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey., Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Saccharum officinarum L.talis (L.) Franco | Oral liquids |

| Jie and Wang. (2009) | Xiaoyao pill | Bupleurum falcatum L., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz., Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf | Pill |

| Li (2009) | Anti-fatigue no. 2 decoction granule | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco, Polygala tenuifolia Willd., Cyperus rotundus L | Granule |

| Ma (2009) | Guipi decoction | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 30 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Dielslog 10 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 10 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 8 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g | Decoction |

| Zhang et al. (2009) | Lixu Jieyu prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Pueraria montana var. 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 10 g, Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F.H.Chen 15 g, Epimedium brevicornu Maxim. 10 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 10 g, Acorus gramineus Aiton 10 g | Decoction |

| Hu et al. (2010) | Buqi Tongluo prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 5 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Pheretima vulgaris Chen 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g | Decoction |

| Chen et al. (2011) | 1. Qixue Liangxu prescription. 2. Ganyu Pixu prescription. 3. Ganshen Kuixu prescription | 1. Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco 12 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Albiziae Cortex 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g. 2. Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g. 3. Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 9 g, Phellodendron amurense Rupr 9 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 15 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 15 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 15 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 15 g, Achyranthes bidentata Blume 15 g, Trionyx sinensis Wiegmann 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 30 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 12 g, Reynoutria Multiflora (Thunb.) Moldenke 30 g | Decoction |

| Li et al. (2011) | Chaihu Shugan pulvis and Guipi decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 12 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 12 g, Citrus medica L. 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 6 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 15 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g | Decoction |

| Liu et al. (2011) | Shugan Yangxue prescription | Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Citrus medica L. 10 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Albiziae Cortex 20 g | Decoction |

| Wang et al. (2011) | Yiqi Ziyin Buyang prescription | 1. Tonifying qi: Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 6 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 3 g. 2. Nourishing the blood: Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 12 g, Paeonia anomala subsp. veitchii (Lynch) D.Y.Hong and K.Y.Pan 12 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 15 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 12 g, Spatholobus suberectus Dunn 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 3 g. 3. Nourishing Yin: Adenophora triphylla (Thunb.) A.DC. 12 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Kergawl. 12 g, Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce 12 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) | Decoction |

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC. 12 g, Pseudostellaria Heterophylla (Miq.) Pax 15 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 6 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 3 g. 4. Tonifying yang: Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 12 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 10 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 12 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 12 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 12 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 12 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 12 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 3 g | |||

| Zhang et al. (2011) | Zhenqi Jiepi decoction | Polygala fallax Hemsl 20 g, Ardisia gigantifolia Stapf 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Pueraria montana var. 30 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Epimedium sagittatum (Siebold & Zucc.) Maxim. 15 g | Decoction |

| Jiang. (2012) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Guipi decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 12 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 9 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 9 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 9 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 6 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 6 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 6 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Kong (2012) | Self-designed anti-fatigue decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 25 g, Eleutherococcus Nodiflorus (Dunn) S.Y.Hu 18 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 12 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Phyllolobium Chinense Fisch. 12 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 12 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 20 g, Epimedium sagittatum (Siebold & Zucc.) Maxim. 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Lonicera Japonica Thunb. 20 g | Decoction |

| Ren and Yu. (2012) | Self-designed Zhongyao Buxu decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 20 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 10 g, Paeonia anomala subsp. veitchii (Lynch) D.Y.Hong and K.Y.Pan 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Tian and Wang. (2012) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 20 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Actaea cimicifuga L.10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 10 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 6 pieces, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Kergawl. 15 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Wang. (2012) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 30 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 20 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 5 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 15 g | Decoction |

| Wu et al. (2012) | Lixu Jieyu prescription | Not reported | Decoction |

| Zhang et al. (2012a) | Lixu Jieyu prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Pueraria montana var., Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, Rhodiola crenulata (Hook.f. and Thomson) H.Ohba, Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F.H.Chen, Epimedium brevicornu Maxim., Curcuma aromatica Salisb., Acorusgramineus Aiton | Decoction |

| Zhang et al. (2012b) | Yaoyao Xiaopi prescription | Polygala fallax Hemsl 25 g, Radix fici simplicissimae 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 15 g, Pueraria montana var. 15 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 15 g | Decoction |

| Zhao. (2012) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 30 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 20 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 10 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 5 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 15 g | Decoction |

| Lai and Lei. (2013) | Baiyu Jianpi decoction | Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. 15 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 6 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Paeonia × Suffruticosa Andrews 10 g, Mentha Canadensis L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Pang and Liu. (2013) | Shengmai pulvis and Xiaoyao pulvis | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Albiziae Cortex 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 15 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. 10 g | Decoction |

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | |||

| Xu et al. (2013) | Jiawei Naoxin kang | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 20 g, Paeonia anomala subsp. veitchii (Lynch) D.Y.Hong and K.Y.Pan 20 g, Spatholobus suberectus Dunn 20 g, Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. 20 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 20 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Pheretima vulgaris Chen 15 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Lycopodium japonicum Thunb. 25 g | Decoction |

| Xu and Wang. (2013) | Chaihu Jia Longgu Muli decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 6 g, Rheum Palmatum L. 6 g, Os Draconis 30 g, Ostrea gigas Thunberg 30 g, Succinum 3 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 5 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 6 pieces | Decoction |

| Zhao. (2013) | Self-designed Baihe Yangxin Jianpi decoction | Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. 30 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 12 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 30 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 30 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 12 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 30 g, Albiziae Cortex 12 g | Decoction |

| Zhao et al. (2013) | Compound of Fufangteng Mixture | Euonymus fortunei var. fortunei, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey | Oral liquids |

| Teng et al. (2014) | Buzhong Jiepi decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20–30 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20–30 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 9 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 9 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 9 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 5 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 5 g, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen and S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep. 15 g, Os Draconis 30 g, Ostrea gigas Thunberg 30 g | Decoction |

| Xu. (2014) | Qingshu Yiqi decoction | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 1 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. 10 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 9 g, Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 9 g, Phellodendron amurense Rupr 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 12 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. 9 g, Hyssopus officinalis L. 12 g, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen and S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep. 9 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 9 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Gao and Pang. (2015) | Wendan decoction and Sini decoction | Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino, Bambusa tuldoides Munro, Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Bupleurum falcatum L., Citrus × aurantium L., Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Zingiber officinale Roscoe, Citrus × aurantium L | Decoction |

| Li and Zao. (2015) | Jianpi Wenshen Shugan prescription | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Curculigo Orchioides Gaertn. 5 g, Epimedium sagittatum (Siebold & Zucc.) Maxim. 5 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Coptis chinensis Franch 10 g | Decoction |

| Gardenia Jasminoides J.Ellis 10 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 10 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 6 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 6 pieces | |||

| Liu et al. (2015) | Shugan Yangxue decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Citrus medica L. 10 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides ‘Chuanxiong’ 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Albiziae Cortex 20 g | Decoction |

| Li. (2015) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 25g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 25g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 20 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 20 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 15 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 12 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 12 g | Decoction |

| Niu et al. (2015) | Bushen Shugan decoction | Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 20 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 15 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 20 g, Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl 15 g, Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 12 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 12 g, Coptis chinensis Franch 6 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Tan et al. (2015) | Sini Decoction and Wulin powder | Cyperus rotundus L. 9 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 9 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 9 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Polyporus umbellatus (Pers)Fr. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. 15 g, Plantago Asiatica L. 15 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 9 g, Asarum Heterotropoides F.Schmidt 3 g, Brassica Juncea (L.) Czern. 6 g | Decoction |

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. (2015) | Wenzhen Yunqi prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Maesen and S.M.Almeida ex Sanjappa & Predeep., Curcuma aromatica Salisb., Acorus Gramineus Aiton, Actinolitum | Decoction |

| Gao and Pang. (2016) | Wendan decoction and Sini powder | Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 6 g, Bambusa tuldoides Munro 6 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 6 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 6 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 9 g | Decoction |

| Shi and Wu. (2016) | Suanzaoren decoction | Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 3 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 6 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 6 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 6 g | Decoction |

| Sun et al. (2016) | Shugan Yiyang capsule | Bupleurum falcatum L., Tribulus Terrestris L., Aspongopus chinensis Dallas, Polistes mandarinus Saussure, Cnidium Monnieri (L.) Cusson, Cistanche Deserticola Ma, Cuscuta chinensis Lam, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill., Gynochthodes Officinalis (F.C.How) Razafim. and B.Bremer, Polygala tenuifolia Willd., Acorus Gramineus Aiton, Pheretima vulgaris Chen, Whitmania pigra Whitman, Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans L. Koch | Capsule |

| Wu et al. (2016) | Xiaopi Yin | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 20 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 10 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 10 g, Epimedium brevicornu Maxim. 10 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 20 g, Psoralea corylifolia L. 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. 6 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20 g, Matricaria Chamomilla L. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Wang. (2017) | Bupi Yishen decoction | Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 30 g, Rhodiola Crenulata (Hook.F. and Thomson) H.Ohba 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 15 g, Psoralea corylifolia L. 20 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 12 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 15 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g | Decoction |

| Ye. (2017) | Shenxian congee | Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 10 g, Euryale ferox Salisb. 10 g, Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Spreng. 10 g, Zea mays L. 50 g | Herbal porridge |

| Zheng et al. (2017) | Shugan Jianpi Yishen prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 12 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 10 g, Epimedium sagittatum (Siebold & Zucc.) Maxim. 10 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Du (2018) | Self-designed Yishen Buxue ointment | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 15 g, Epimedium sagittatum (Siebold & Zucc.) Maxim.12 g, Psoralea corylifolia L. 10 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 10 g | Decoction |

| Li et al. (2018) | Yiqi Yangxue Bupi Hegan prescription | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 40 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 15 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 10 g, Corydalis yanhusuo (Y.H.Chou & Chun C.Hsu) W.T.Wang ex Z.Y.Su and C.Y.Wu 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 10 g, Gardenia Jasminoides J.Ellis 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g | Decoction |

| Liu and Cai. (2018) | Bupiwei Xieyinhuo Shengyang decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 10 g, Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 10 g, Hansenia Weberbaueriana (Fedde Ex H.Wolff) Pimenov & Kljuykov 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 8 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 7 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 7 g, Coptis chinensis Franch 5 g | Decoction |

| Ou et al. (2018) | Guipi decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 25 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 7 g | Decoction |

| Weng (2018) | Liujunzi decoction | Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 9 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 9 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 3 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 9 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 4.5 g | Decoction |

| Study | Prescription name | Ingredients of herb prescription | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. (2018) | Guipi decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 20 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 15 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 10 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 10 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Luo (2018) | Qingre Qushi prescription | Panax Quinquefolius L. 10 g, Morus alba L. 10 g, Prunus armeniaca L. 10 g, Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. 10 g, Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 10 g, Magnolia officinalis var. biloba Rehder and E.H.Wilson 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Artemisia Capillaris Thunb. 10 g, Coix lacryma-jobi L. 50 g, Coptis chinensis Franch 5 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 5 g, Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz. ex Ledeb.) Schischk. 10 g, Tetrapanax papyrifer (Hook.) K.Koch 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 5 g | Decoction |

| Ding (2019) | Guipi decoction | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 25 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 15 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 7 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g | Decoction |

| He (2019) | Shugan Jianpi Huoxue prescription | Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Cyperus rotundus L. 15 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 12 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 9 g, Eleutherococcus Senticosus (Rupr. and Maxim.) Maxim. 12 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 20 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Conioselinum anthriscoides “Chuanxiong” 10 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g | Decoction |

| Hu (2019) | Buzhong Yiqi and Xiaochaihu decoction | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 24 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 29 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 14 g, Agrimonia Pilosa Ledeb 24 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 21 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 14 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 21 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 21 g, Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. 7 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 14 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 14 g | Decoction |

| Liu et al. (2019a) | Jiawei Lingzhi pill | Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. 30 g, Colla Carapacis et Plastri Testudinis 12 g, Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss. ex Fr.) Karst. 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F.H.Chen 5 g, Acorus Gramineus Aiton 5 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 10 g | Pill |

| Liu et al. (2019b) | Chaihu Guizhi decoction grain | Bupleurum falcatum L., Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm., Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Zingiber officinale Roscoe, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill | Granule |

| Liu et al. (2019c) | Jianpi Yishen decoction | Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 10 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 15 g, Pseudostellaria Heterophylla (Miq.) Pax 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 10 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 20 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Cistanche Deserticola Ma 10 g, Psoralea corylifolia L. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 12 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L.6 g | Decoction |

| Ma et al. (2019) | Self-designed Jiawei Erxian decoction | Epimedium brevicornu Maxim. 15 g, Curculigo Orchioides Gaertn. 10 g, Gynochthodes Officinalis (F.C.How) Razafim. and B.Bremer 10 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. Actaea heracleifolia (Kom.) J.Compton 6 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Phellodendron amurense Rupr 5 g, Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge 10 g | Decoction |

| Shi (2019) | Xiaoyao pulvis Jiawei | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 10 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Mentha Canadensis L. 6 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 20 g | Decoction |

| Wang (2019) | Sanren decoction and Sijunzi decoction | Prunus armeniaca L. 10 g, Wurfbainia Vera (Blackw.) Skornick. and A.D.Poulsen 10 g, Coix lacryma-jobi L. 50 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 10 g, Magnolia officinalis var. biloba Rehder and E.H.Wilson 10 g, Panax ginseng C.A.Mey. 10 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 10 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 20 g, Tetrapanax papyrifer (Hook.) K.Koch 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 5 g | Decoction |

| Yang (2019) | Zuogui pill | Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. 250 g, Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 120 g, Cornus Officinalis Siebold & Zucc. 90 g, Lycium chinense Mill. 20 g, Cervus nippon Temminck 120 g, Cuscuta chinensis Lam. 120 g, Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. 120 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 90 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 60 g, Cyperus Rotundus L. 60 g | Pill |

| Dong (2020) | Qingshu Yiqi decoction grain | Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Actaea cimicifuga L. 9 g, Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. 9 g, Amomum villosum Lour. 10 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 10 g, Phellodendron amurense Rupr 12 g, Citrus × aurantium L. 12 g, Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Alisma plantago-aquatica subsp. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Mosla Chinensis Maxim. 15 g, Hyssopus officinalis L. 20 g, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g | Decoction |

| Li (2020) | Buzhong Yiqi decoction and Xiaochaihu decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Curcuma aromatica Salisb. 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 12 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 5 pieces | Decoction |

| Mao (2020) | Yishen Tiaodu method | Dioscorea oppositifolia L. 10 g, Zea mays L. 50 g, Euryale Ferox Salisb. 10 g, Allium tuberosum Rottler ex Spreng. 10 g | Decoction |

| Wang (2020) | Chaihu Guizhi decoction | Bupleurum falcatum L. 12 g, Neolitsea cassia (L.) Kosterm. 9 g, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi 9 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 9 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 9 g, Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Makino 9 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 9 g, Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. 6 pieces, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 6 g | Decoction |

| Chen (2021) | Xiaoyao powder | Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 12 g, Paeonia lactiflora Pall. 12 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 12 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 10 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 6 g, Bupleurum falcatum L. 6 g, Mentha Canadensis L. 5 g, Zingiber officinale Roscoe 3 g | Decoction |

| Li et al. (2021) | Jiannao Yizhi ointment | Astragalus mongholicus Bunge 30 g, Ziziphi Spinosae Semen 25 g, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf 15 g, Dimocarpus Longan Lour. 15 g, Polygala tenuifolia Willd. 15 g, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels 15 g, Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz. 15 g, Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. 15 g, Dolomiaea Costus (Falc.) Kasana and A.K.Pandey 7 g, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. 10 g | Ointment |