Abstract

Parents of children seeking non-urgent care in the emergency department completed surveys concerning media use and preferences for health education material. Results were compiled using descriptive statistics, compared by health literacy level with logistic regression, adjusting for race/ethnicity and income. Semi-structured qualitative interviews to elicit reasons for preferences, content preference, and impact of health information were conducted and analyzed using content analysis. Surveys (n=71) showed that despite equal access to online health information, parents with low health literacy were more likely to use the internet less frequently than daily (p<0.01). Surveys and interviews (n=30) revealed that health information will be most effective when distributed by a health care professional and must be made available in multiple modalities. Parents requested general information about childhood illness including diagnosis, treatment, and signs and symptoms. Many parents believed that appropriate health information would change their decision-making regarding seeking care during their child’s next illness.

Keywords: health literacy, emergency services utilization, health education

INTRODUCTION:

There are 20 million pediatric Emergency Department (ED) visits in the United States annually and over half are non-urgent.1,2 Non-urgent ED use directly impacts the increasing number of ED visits, which leads to ED overcrowding and, worse patient outcomes.3,4 The cost of an ED visit is also considerably more than a clinic visit.4,5 While there are numerous factors that contribute to non-urgent ED use, parental low health literacy is an independent predictor of both higher ED use and non-urgent ED use, especially for children without a chronic illness.6,7 In some studies, more than half of parents presenting to the ED with their children have low health literacy, which greatly affects their ability to make health decisions for their child. 6,8

Parents who lack the necessary information or resources often rely on EDs for health concerns that could be treated at home or by a primary care clinic.9,10 Parents commonly go to the ED when they need assurance that their child’s condition is not serious or life-threatening, and parents with low health literacy frequently describe their child’s condition as severe despite being triaged as nonurgent.11–14 Most parents do seek health information about their children after receiving a diagnosis or when their child is healthy, but search for information much less frequently when their child is acutely ill or injured.9,15,16 Parents frequently go to the internet for health information and they prefer easy to access, professionally validated, simple messages.9 Low health literacy, which is common in this non-urgent ED population, is associated with lower internet use by adults.15 Despite this, few studies have examined the media use of parents in the ED nor their specific preferences for the medium, location, and content of educational information, and none analyzed this in the context of health literacy.9,15,16

Gaining perspective on parents’ health information preferences will result in more parents receiving the desired information to make appropriate health decisions for their children, with the potential to reduce non-urgent pediatric ED visits. Therefore, this mixed-methods study seeks to define current media access and use and educational content preferences within parents presenting with a child for a non-urgent ED visit and any differences based on health literacy. We hypothesized that parents with low health literacy would have equal access to media but use media less often. We also hypothesized that parents with low health literacy would have different educational preferences than parents with adequate health literacy for education about childhood illness including analysis of: 1) educational medium, 2) location of distribution, 3) content, and 4) impact of health information.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Population and Design

The mixed methods study took place in the ED at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (CHW) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. CHW’s ED serves an urban/suburban population with over 65,000 visits annually. The study was reviewed and approved by the CHW Institutional Review Board.

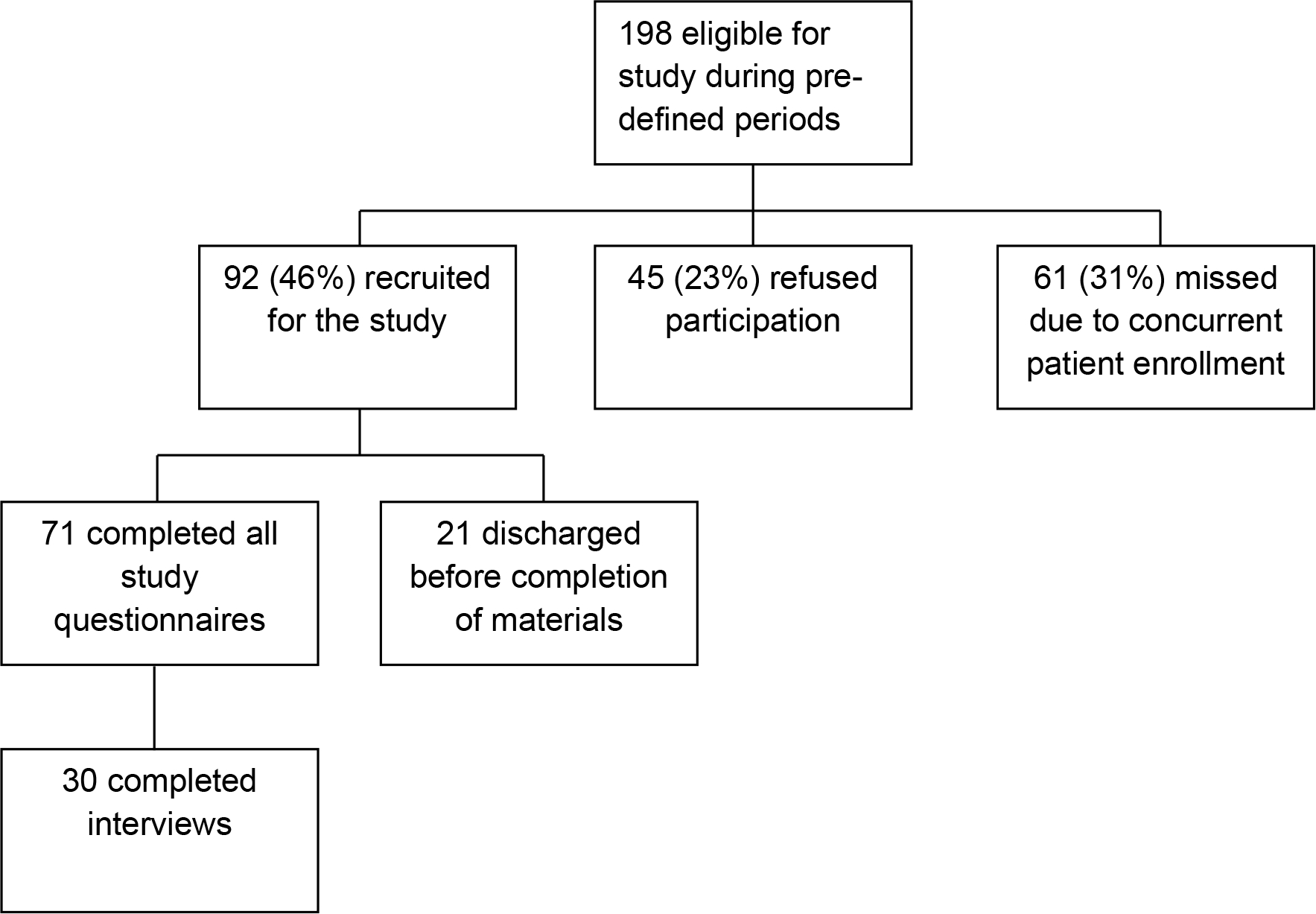

From December 2013-August 2014 a purposive sample of participants were consecutively recruited to complete the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), the Children with Special Health Care Needs questionnaire (CSHCN), a sociodemographic survey, and an in-person semi-structured interview. After completing the initial measures and sociodemographic survey, participants were asked to complete the 15 to 30 minute interview (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Study Flow Diagram

Study Protocol

A trained research assistant (RA) enrolled parents and/or legal guardians (hereafter termed parents) during pre-selected four-hour weekday daytime blocks. Parents were enrolled at any point during the child’s ED care. Inclusion criteria included parents aged ≥ 18 years old seeking care for an acute illness or injury for children ≤ 8 years old. Only parents of children whose triage level was 5 out of 5 on the Emergency Severity Index, to prospectively select children with non-urgent visits, were eligible. This method of classification is the best method of prospectively identifying patients most likely to have a non-urgent ED visit. Parents were excluded if they were non-English speaking, the child was in distress or was being seen for a non-accidental trauma. After confirming eligibility, an RA utilized a low literacy script to obtain consent.

Measures

After consent was given, RAs administered the NVS, CSHCN, and parents used an iPad installed with REDcap survey software to self-administer the socio-demographic survey. The NVS is a standardized measure to screen for health literacy and numeracy in clinical settings, and the CSHCN is used to determine chronic illness status.17,18 The NVS was scored as low health literacy (0–3 correct/6) or adequate health literacy (4–6 correct/6) per published cut-off.17 Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Medical College of Wisconsin.19 The survey included questions on internet access (Yes/No access) and use (Daily use vs. less than daily use) from the Pew Research Center and questions seeking parental preference of health educational material medium and location.20 Parents were allowed to select multiple educational mediums or locations. The study measures were administered in examination rooms during or after completion of ED care.

Qualitative Interviews

After completing the initial measures and survey, parents were asked to complete an additional in-person semi-structured interview (Figure 1). Individual semi-structured interviews using standard questions (Table 1) were conducted by one interviewer (A.M.) who was blinded to the parent’s health literacy score. Interviews were conducted after treatment was completed. Interviews lasted between 15 and 30 minutes and were recorded on an encrypted digital recorder. A subset of interview questions aimed to understand the parent preference for health information, including: 1) medium preferences; 2) location preferences; 3) content preferences; and 4) impact of health information.

Table 1:

Semi-structured Interview Questions

| What do you wish you had when (child’s name) is sick or hurt? |

| Medium Preference |

| I want you to think about ways that you could get information about your child’s health, what would help you when (child’s name) gets sick or hurt? |

| What type of material would be helpful to you in making decisions about the health of your child? |

| Written information (books or pamphlets), videos, internet sites, emails, or in person teaching? |

| Location Preference |

| Where would be a convenient place to get this from? |

| ER, Doctor’s office, community center, school? |

| Content Preference |

| What information do you need to help you treat (child’s name) at home when he/she is sick or hurt? |

| What type of information would be helpful to you? |

| Information on what causes problems, how to diagnose a problem, how to treat a problem, or how to take care of (child’s name) when he/she is not sick or hurt. |

| Impact of Information |

| Do you think it would be helpful to have information about child illnesses at home to use when (child’s name) is sick or hurt? |

| A book, phone app or program, or DVD? |

| If you had information at home about caring for (child’s name) while they are sick or hurt, what would change about caring for your child this time when he/she was sick or hurt? |

Mixed Methods Analysis

Socio-demographic data from the survey were compiled using descriptive statistics. Parents’ answers about media access and use, medium, location, and content preferences for health education materials were first compiled using descriptive statistics, then compared between low and adequate health literacy groups using chi-square analysis. For variables with significant differences between low and adequate health literacy, the analyses were adjusted for race/ethnicity and household income using logistic regression forcing those variables into the model.

Interviews were transcribed and independently coded by two reviewers (A.D. and A.M.) and continued until thematic saturation was reached. Coding began after ten interviews were completed, and then after every two to five interviews. Consensus agreement resolved any disagreements around coding. Inductive reasoning was used to develop initial themes and the constant comparative method was used for new themes. Thematic analysis was done concurrently with enrollment to permit theme discovery to influence future interviews. Themes were analyzed using content analysis to determine which 1) medium, 2) location, and 3) content parents preferred, reasons for those preferences, and whether information would impact their decision making. Health literacy scores and demographic information were integrated with interview transcripts and codes using NVivo version 11.0 software. 21

The survey data regarding medium and location preferences of educational materials were then integrated with corresponding interview analysis in order to gain a deeper understanding of parents’ preferences. Parents were categorized as having either low or adequate health literacy to compare differences in preferences for health information. The socio-demographic data and qualitative analysis are hence grouped together based on theme and compared based on health literacy.

RESULTS:

Of the 71 parents that completed the initial measures and survey, the median age was 26 years and ranged from 18–53; half were African American and 19% were Hispanic. High school was the highest level of education for 49% of parents and 50% of parents had low health literacy. Over 90% of children had public health insurance, and the median age of children was two years old. The children’s most common presenting complaints included cough, ear pain/drainage, fever and rash. The demographic characteristics of the parents interviewed were similar (Table 2).

Table 2:

Parent and Child Demographic Information

| Survey (n=71) (%) | Interview (n=30) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Parent | ||

| Age (y; range) | 26; 18–53 | 26; 18–48 |

| Female Gender | 60 (85) | 25 (83) |

| Foreign Born | 12 (17) | 4 (13) |

| Ethnicity* | ||

| White | 17 (24) | 7 (23) |

| Black | 35 (50) | 15 (50) |

| Hispanic | 13 (19) | 4 (13) |

| Other | 5 (7) | 4 (13) |

| Health Literacy | ||

| Adequate (4–6) | 36 (51) | 15 (50) |

| Low (0–3) | 35 (49) | 15 (50) |

| Education** | ||

| Less than HS | 4 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Graduated HS | 35 (49) | 15 (50) |

| 1–4 College | 24 (33) | 13 (43) |

| ≥ College degree | 8 (11) | 1 (3) |

| Employed outside of home | 42 (58) | 17 (57) |

| Household Income | ||

| ≤$20,000 | 31 (46) | 12 (44) |

| $20,000–$30,000 | 20 (29) | 7 (26) |

| $30,001–$40,000 | 9 (13) | 5 (19) |

| Over $40,000 | 8 (12) | 3 (11) |

| Child | ||

| Age (y; range) | 2; .08–8 | 2; .08–8 |

| First Born | 35 (50) | 14 (47) |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 7 (10) | 3 (10) |

| Public | 65 (90) | 27 (90) |

| None | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic Illness | 26 (36) | 14 (47) |

One parent declined to answer question

Two parents declined to answer question

Media Access and Use

The survey showed internet accessibility was common, 91% of parents had internet access, with no significant difference between those with low and adequate health literacy (89% vs 94% p=0.39). However, parents with low health literacy were less likely to access the internet at least once per day- 33% low vs. 85% adequate health literacy, p <0.01) and this persisted after adjusting for race/ethnicity and household income (p <0.01).

The most common access point for the internet was a smart phone (58%), followed by a home computer (53%), then 16% on a computer at work. Parents with adequate health literacy were more likely to use the internet on a smart phone (71 vs. 44% p=0.02). Nearly all parents (99%) possessed a cell phone and 85% of all parents had a smart phone with no differences between adequate and low health literacy.

Medium Preference

When surveyed about the best way to get general health information about child illness or injury, 45% of parents said in-person teaching, 38% said they preferred getting information from a paper, book or pamphlet, 38% said a website, followed by 35% and 8.5% stating email and videos respectively. Only 4% said they would not be interested in any more information.

When interviewed about their preferred medium for receiving information, almost half of parents said they would like to get printed information, like pamphlets or short handouts. Print information was more important to parents with low health literacy. Parents said print was preferred over other methods because it offers an opportunity to refer to that information later. One parent explained, “Because you can take your time to look on paper and go back.” Parents, especially those with low health literacy, wanted brief information, which parents referred to as, “pamphlets” (Table 3).

Table 3:

Medium Preference

| Medium Preference | Written |

| “You can take your time to look on paper and go back and forward over it. With online it’s kind of like you got to rush through it because your computer might freeze up or something else might happen but with paper you can always just go back and forth to read it.” “I think like it could be nice that they have just a health book or a health magazine, that teach you or tell you how little different parts of articles about everything that you could be sick by, rash, you know, different stuff like that.” “I think like some pamphlets about, you know, certain things like stomach aches, flu, common cold, things like that, I think that’d be helpful.” “Maybe a little pocket guide.” | |

| Website | |

| “[On websites] I can see it because that’s instant. I can look it up immediately. I can look it up, I can see pictures of whatever I’m trying to look for, you know? I can get multiple different types of information for what I’m looking for.” “It would be really to cool to have a website that was all about the sicknesses that kids got or that updated you about the previous viruses and everything that is going on.” “It would be cool to have a website that would tell you what’s the season, and what’s going around, what to look for, ask your doctor about this. That would be really cool, that’s updated with the seasons and sicknesses and would give you general information about each and every one that usually kids and toddlers get about that age.” “I actually like seeing visual stuff, so when I go on line it is a lot of visual stuff more than just reading.” | |

| Smart Phone App | |

| “Apps are always nice to have because they’re quick, they’re easy, you don’t have to wait too long for them to boot up for you.” “A phone app would be awesome. Because when I was laying in bed last night I wouldn’t even have to get up and even get on a computer. So it was very accessible.” | |

| In-Person | |

| “In-person. Because you get to see the person that you are talking to, you get to see their expressions, you get to know, like, it’s like basically hands-on. I am going to learn everything; I need to learn that way.” “In-person teaching. Because I am more...hands-on.” | |

| Video or DVD | |

| “I actually like seeing visual stuff, so when I go on line it is a lot of visual stuff more than just reading. I want to be able to see exactly what the person is doing, even if there is just videos.” “I’m not into reading. I can read but, I’m not into reading. I like DVDs better.” | |

| Live-Chat | |

| “[I would prefer live-chat because] you could chat with someone and ask them...about something you read on there that wasn’t clear. Or that you wanted more of an explanation that would be fantastic!” |

In interviews, half of parents said they wanted information available on a website. Parents preferred the internet because it’s quick, easy to access, parents have experience using it, and it offers pictures and videos to supplement text. One parent said, “I can look it up immediately… I can get multiple different types of information for what I’m looking for” (Table 3). Consistent with accessing information via the internet or digitally, over one third of parents would like a smart phone app, which was the third most requested medium to receive health information. Parents like smart phone apps because of their accessibility and their functionality. One parent summed up why she preferred smart phones saying, “they’re quick, they’re easy, you don’t have to wait too long.” More parents with adequate health literacy said smart phone apps would be a preferable way to get information.

In regards in-person teaching, interviews contrasted with the survey with only a few parents expressed wanting in-person teaching. One parent explicitly expressed the benefits of face-to-face communication when she said, “Because you get to see the person that you are talking to, you get to see their expressions” (Table 3). Additionally, a few parents, all with low health literacy, specifically said a video or a DVD option would be the preferred way to get information. One parent said, “I want to be able to see exactly what the person is doing, even if there is just videos.” Two parents said live-chat would be a helpful option and one parent said a nurse phone-line; all of these alternatives were suggested by parents with adequate health literacy. The reason parents chose a nurse line or chat line was due to the credibility of the information. One parent explained why she would like a live-chat option saying, “I would trust that a lot.” Lastly, one parent also suggested a ‘Parent care kit’ that could be given to parents that could include a variety of basic resources for parents like common medications, coupons and general information.

Location Preference

When asked on the survey where they would prefer to receive health information, 62% of parents said a healthcare location (38% - doctor’s office, 24% - Emergency Room), 10% at a community center, 6% at school, and one parent wrote in “my nurse visitor.”

Interviews concurred with survey results that information is preferred coming from a healthcare location. Parents said any healthcare location, including the clinic, ED, or school nurses’ office is preferred vs. other locations such as community centers or libraries. Parents believe that information was validated by a healthcare professional when present at these locations and thus credible and trustworthy. One parent described why she preferred getting information from her child’s doctor as opposed to searching online, “Because then I can trust it. You can’t trust everything on the internet” (Table 4). Parents described trusting the information from healthcare locations because they perceive the information as professionally validated. Getting information from a health professional or healthcare location was the most preferred location of information by both adequate health literacy and low health literacy parents, though this was expressed by more parents with adequate health literacy.

Table 4:

Location Preference

| Location Preference | A Health Professional |

| “[Information from a healthcare provider is best] because then I can trust it. You can’t trust everything on the internet.” “When it comes to medical care, I guess you always put the hospital at the top because they know the most or they got the most.” “Maybe at school, or doctor’s office. Somebody who is experienced.” | |

| School | |

| “The school would be good... because they are there all the time. You don’t come to the ER all the time.” “Schools and daycares because that’s where kids pass on all of their germs.” |

Schools and Community Centers were also mentioned by several parents, all with adequate health literacy, as locations where information would be helpful. Parents preferred these locations because of the frequency of visiting those locations and because typically school’s employee a “nurse.” One parent described the preference for getting information from a professional and suggested a school because she could access “somebody who is experienced” (Table 4).

Content Preference

During interviews, almost half of parents said they wanted information on diagnosis and treatment. Often this was described as wanting general information about illnesses, such as “…some pamphlets about… certain things like stomach aches, flu, common cold, things like that” (Table 5). One parent said, “the number one most helpful thing would be how to diagnose it. And then number two would be how do you treat it.” Parents with low and adequate health literacy both requested information on diagnosis and treatment. Parents with low health literacy also frequently wanted information on signs and symptoms whereas only one parent with adequate health literacy mentioned this.

Table 5:

Content Preference

| Content Preference | Diagnosis and Treatment |

| “OK, the number one most helpful thing would be how to diagnose it. And then number two would be how do you treat it, and how you take care of your kid.“ “Like what can I do to help fix the problem in order instead of having to come to the ER or the doctor.” “I think like some pamphlets about, you know, certain things like stomach aches, flu, common cold, things like that, I think that’d be helpful.” “It would be really to cool to have a website that was all about the sicknesses that kids got or that updated you about the previous viruses and everything that is going on” “It would be cool to have a website that would tell you what’s the season, and what’s going around, what to look for, ask your doctor about this. That would be really cool, that’s updated with the seasons and sicknesses and would give you general information about each and every one that usually kids and toddlers get about that age.” | |

| Signs and Symptoms | |

| “I’ll punch in the symptoms, and what I think the symptoms are and then I’ll go from there.” “I go to google and I type in ‘if a child [has] swollen tonsils what can be the problem’ and then all the stuff will come up like what it can be” | |

| Treatment Location Information | |

| “If my child needs help, you know he’s this age you know where’s the best place near here to go” |

During interviews parents also requested information on giving medication, red flags, nearest treatment options, and disease specific information for conditions such as asthma. Other parent suggestions included having information available on what are common ailments or injuries for the time of year, what illnesses are currently “going around,” and general information about what commonly affects kids at different ages. Lastly, one parent mentioned having a “one-stop-shop” for all important phone numbers and resources, with an option to connect to those resources (Table 5).

Impact of Information

Parents had mixed responses when discussing the impact of this information. Some parents felt having information or better information would have made a difference in their decision to seek care or how they handled their child’s situation. When asked if better information would have made a difference, one parent said, “It would have changed a lot because I would know what to do” (Table 6). Having information may not only help parents make decisions but can also help them feel comfortable and more confident about those decisions. Another parent said, “I think it would have actually assisted me a little better in how to take care of the symptoms and stuff like that vs me getting scared and actually coming to the hospital.” Other parents did not feel additional information would have been helpful in stopping them from bringing their child for a physical examination. After one parent brought her child in with vomiting and diarrhea, she was asked if she would have had information on vomiting and diarrhea would that have helped her at all, she said, “I probably wouldn’t have even looked at it. Because, I feel better getting care.” She later went on to say, “Having him examined (is what’s important), because it might be something that I may be mistaking.” This group of parents describe lacking trust in their assessment skills and are concerned they may miss something important. No differences in impact were found between low and adequate health literacy parents.

Table 6:

Impact of Health Information

| Impact of Health Information | Beneficial |

| “It would have changed a lot because I would know what to do.” “I think it would have actually assisted me a little better in how to take care of the symptoms and stuff like that vs. me getting scared and actually coming to the hospital.” “Yes it would have helped me out. That mean I wouldn’t have been so frantic” | |

| Not Beneficial | |

| “I probably wouldn’t have even looked at it. Because, I feel better getting care, you know what I mean...He needs to be seen physically versus literature.” “Having him examined [is what is important], because it might be something that I may be mistaking. And, what it I am doing things and procedures and stuff that, you know, make it worse or agitate the situation. I’m not going to do that.” “Yeah, just to make sure exactly what it was or if it was something dangerous or something like that... I would rather take them to the doctor.” |

DISCUSSION:

Parents have access to many types of educational media, though parents with low health literacy use the internet less frequently. Parents want diagnostic and treatment information about childhood illness that they can trust, easily access, and serve as reference material. Parents prefer to receive information from health professionals or a healthcare location because that implies trustworthy information. Parents with low health literacy prefer paper based information and this must be considered in future interventions. Lastly, many parents felt acute illness information would be helpful to treat a child at home during a future illness, but others rely on a healthcare provider to physically assess the child.

When designing an intervention to decrease ED utilization for acute illness, parents described that the information needs to be easily accessible such as web-based, but this has to be tempered by the differing needs of parents with low health literacy. As described by parents, web-based information is easily accessible and desired. However, in a real-world setting, we found that parents with low health literacy may not access the internet for information. Previous research suggests the lack of internet use may be a matter of internet access as those with low health literacy were less likely to have access to the internet.22,23 In contrast, our results and others show that internet access was not impacted by health literacy level, rather parents with low health literacy have similar access, but are less likely to use it daily.24,25 Others have found that patients with low health literacy were less likely to use digital tools or perceive them as easy or useful.26 This is also reflected in the qualitative comments that parents with low health literacy prefer paper information more so than online or app-based information. This likely reflects the difficulty of using the internet of a parent with low health literacy rather than a lack of access.

Many parents, but more of those with adequate health literacy mentioned websites and a smart phone app suggesting parents are also primarily concerned with being able to quickly and easily access information, similar to previous research.24 Moreover, parents endorsed how challenging it can be to access information when their child is ill, and requested information that is easily accessible for these situations. Parents, especially those with low health literacy, had a preference for brief materials, indicating what is currently available may be too burdensome for some parents and being able to provide concise information will potentially help these parents.

Parents most frequently said they preferred getting information from a health professional or a healthcare location. Parents believe that the information received from a healthcare professional or healthcare location implies that the information is credible. Likewise, previous research found the primary source for obtaining health information was a health care professional, without differences in health literacy.27 Future interventions may need to focus on information delivery in healthcare settings rather than community settings or schools. This may only be applicable to this group of parents and not others because of the high prevalence of low health literacy in this population. Source validity may be more important to this group of parents than others. Furthermore, many parents expressed their desire to actually have the child seen and physically examined by a health professional to make sure nothing is “missed,” similar to other studies of non-urgent ED use.11,28 No matter the intervention, there will be still be those instances of parents not being comfortable with their ill child until the child has had a formal examination.

During interviews, parents requested general information about acute childhood illness, diagnosis and treatment, as well as signs and symptoms. Previous research suggests information should focus on the signs and symptoms of the most serious and most common childhood illnesses. 29 This indicates that some parents are not as confident in their ability to analyze, identify and treat basic health problems as they desire and need aid in this regard. Previous studies have found that parents want information about acute childhood conditions, but have not received it from their child’s healthcare provider.30 Giving parents the necessary information to adequately diagnosis and treat minor illnesses and injuries may provide much needed support for these parents.

When determining future educational interventions, the development must include consideration of the parents with low health literacy at the forefront of design to be effective. An ideal intervention improves outcomes for all patients regardless of health literacy. To do this, different media should be made available to match the needs and preferences of patients and their families. For instance, having an easy to access smart phone app that has videos and potentially a way to instantly communicate, a full website as a secondary option, and additional printed material provided by a healthcare professional or location would likely have the greatest effect to be given to all parents, including those with low health literacy.

Limitations

The findings of this study may not apply beyond the non-urgent Emergency Department setting. Half of these parents have low health literacy, which likely leads to differences in information preferences. Patients and parents in other settings may respond to electronic only education, but our study suggests that printed informational materials need to be included in the ED or other populations with a high prevalence of parents with low health literacy. Additionally, some parents with low health literacy had difficulty articulating their preferences, making interpretation difficult. This was a convenience sample, limiting the interpretation of this data.

CONCLUSION:

Health literacy is an important consideration in the development of educational interventions, especially in populations with a high prevalence of low health literacy. Parents want information they can trust and easily access to diagnose and treat their child’s illness. Because of different parent educational needs in this population with the majority of parents with low health literacy, it is likely parents would benefit from a combination of print, internet, or app-based information. If healthcare providers work to ensure there are multiple quality information resources available for their patients and families, there is potential to reduce the number of the non-urgent ED visits, which is a burden on the health care system and families alike.

Grant numbers and/or funding information:

The project described was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR001436. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Adam M. Drent, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI.

David C. Brousseau, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI.

Andrea K. Morrison, Department of Pediatrics, Section of Emergency Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI.

References

- 1.Suruda A, Burns TJ, Knight S, Dean JM. Health insurance, neighborhood income, and emergency department usage by utah children 1996–1998. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmer KP, Walker A, Minkovitz CS. Epidemiology of pediatric emergency department use at an urban medical center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(2):84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herman A, Mayer G. Reducing the use of emergency medical resources among head start families: A pilot study. J Community Health. 2004;29(3):197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derlet RW, Richards JR. Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: Complex causes and disturbing effects. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bamezai A, Melnick G. Marginal cost of emergency department outpatient visits: An update using california data. Med Care. 2006;44(9):835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison AK, Schapira MM, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and nonurgent visits. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(3):309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison AK, Chanmugathas R, Schapira MM, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Caregiver low health literacy and nonurgent use of the pediatric emergency department for febrile illness. Acad Pediatr. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, eds. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. 1st ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neill SJ, Jones CH, Lakhanpaul M, Roland DT, Thompson MJ, the ASK SNIFF research team. Parent’s information seeking in acute childhood illness: What helps and what hinders decision making? Health Expect. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin NP, Goepp JG, Malia T, Harris L, Poordabbagh A. Nonurgent use of a pediatric emergency department: A preliminary qualitative study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(1):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costet Wong A, Claudet I, Sorum P, Mullet E. Why do parents bring their children to the emergency department? A systematic inventory of motives. Int J Family Med. 2015;2015:978412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry A, Brousseau D, Brotanek JM, Tomany-Korman S, Flores G. Why do parents bring children to the emergency department for nonurgent conditions? A qualitative study. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(6):360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubicek K, Liu D, Beaudin C, et al. A profile of nonurgent emergency department use in an urban pediatric hospital. Pediatric Emergency Care, Ped Emer Care. 2012;28(10):977–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon RY, Cheng TL, Patel KM, Baumhaft K, Scheidt PC. Parental literacy level and understanding of medical information. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2):e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman RD, Macpherson A. Internet health information use and e-mail access by parents attending a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(5):345–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoo K, Bolt P, Babl FE, Jury S, Goldman RD. Health information seeking by parents in the internet age. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(7–8):419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss B, Mays M, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Annals of family medicine. 2005;3(6):514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein REK, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: Development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2002;2(1):38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Question search. pew research center. PewResearchCenter Web site. http://www.pewresearch.org/question-search/?keyword=internet+access&x=0&y=0. Accessed November, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR international pty ltd. version 10, 2012. . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen JD, King AJ, Davis LA, Guntzviller LM. Utilization of internet technology by low-income adults: The role of health literacy, health numeracy, and computer assistance. J Aging Health. 2010;22(6):804–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey SC, O’Conor R, Bojarski EA, et al. Literacy disparities in patient access and health-related use of internet and mobile technologies. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):3079–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manganello J, Gerstner G, Pergolino K, Graham Y, Falisi A, Strogatz D. The relationship of health literacy with use of digital technology for health information: Implications for public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Deursen A, van Dijk J. Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, New Media Soc. 2010;13(6):893––911. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackert M, Mabry-Flynn A, Champlin S, Donovan EE, Pounders K. Health literacy and health information technology adoption: The potential for a new digital divide. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(10):e264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutierrez N, Kindratt TB, Pagels P, Foster B, Gimpel NE. Health literacy, health information seeking behaviors and internet use among patients attending a private and public clinic in the same geographic area. J Community Health. 2014;39(1):83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams A, O’Rourke P, Keogh S. Making choices: Why parents present to the emergency department for non-urgent care. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(10):817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones CH, Neill S, Lakhanpaul M, Roland D, Singlehurst-Mooney H, Thompson M. Information needs of parents for acute childhood illness: Determining ‘what, how, where and when’ of safety netting using a qualitative exploration with parents and clinicians. BMJ Open. 2014;4(1):e003874–2013–003874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenberg SR, Bair-Merritt MH, Colson ER, Heeren TC, Geller NL, Corwin MJ. Maternal report of advice received for infant care. Pediatrics [Mother’s dont’ receive preventative information]. 2015;136(2):e315–e322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]