Abstract

Objectives

Few machine learning (ML) models are successfully deployed in clinical practice. One of the common pitfalls across the field is inappropriate problem formulation: designing ML to fit the data rather than to address a real-world clinical pain point.

Methods

We introduce a practical toolkit for user-centred design consisting of four questions covering: (1) solvable pain points, (2) the unique value of ML (eg, automation and augmentation), (3) the actionability pathway and (4) the model’s reward function. This toolkit was implemented in a series of six participatory design workshops with care managers in an academic medical centre.

Results

Pain points amenable to ML solutions included outpatient risk stratification and risk factor identification. The endpoint definitions, triggering frequency and evaluation metrics of the proposed risk scoring model were directly influenced by care manager workflows and real-world constraints.

Conclusions

Integrating user-centred design early in the ML life cycle is key for configuring models in a clinically actionable way. This toolkit can guide problem selection and influence choices about the technical setup of the ML problem.

Keywords: Machine Learning; Decision Support Systems, Clinical; Software Design

Introduction

Despite the proliferation of machine learning (ML) in healthcare, there remains a considerable implementation gap with relatively few ML solutions deployed in real-world settings.1 One common pitfall is the tendency to develop models opportunistically—based on availability of data or endpoint labels—rather than through ground-up design principles that identify solvable pain points for target users. There is a long history of clinical decision support tools failing to produce positive clinical outcomes because they do not fit into clinical workflows, cause alert fatigue or trigger other unintended consequences.2 3 Li et al introduced a ‘delivery science’ framework for ML in healthcare, which is the concept that the successful integration of ML into healthcare delivery requires thinking about ML as an enabling capability of a broader set of technologies and workflows rather than the end product itself.4 However, it is still unclear how to operationalise this framework, particularly how to select the right healthcare problems where an ML solution is appropriate. As ML becomes increasingly commoditised with advances like AutoML,5 the real challenge shifts towards identifying and formulating ML problems in a clinically actionable way.

User-centred or human-centred design principles are recognised as an important part of ML development across a range of sectors.6 Here, we introduce a toolkit for user-centred ML design in healthcare and showcase its application in a case study involving care managers. There were an estimated 3.5 million preventable adult hospital admissions in the USA in 2017, accounting for over US$30 billion in health care spend.7 Care management aims to assist high-risk patients in navigating care by proactively targeting risk factors via social and medical interventions. In this case study, we provide practical guidance for ‘understanding the problem’ and ‘designing an intervention’ (stages in the Li et al framework) via user-centred design principles. We draw on cross-domain resources, specifically the Google People+AI Research guidebook8 and the Stanford d.school design thinking framework (Empathise/Define/Ideate/Prototype/Test),9 which we adapt for a clinical setting.

Methods

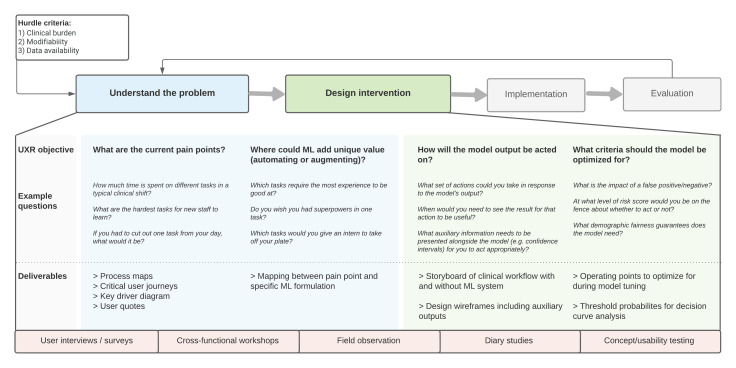

Figure 1 illustrates the toolkit. First, a problem must satisfy a set of ‘hurdle criteria’: is it worth solving? Specifically, the problem must be associated with significant morbidity or clinical burden, have evidence of modifiability and have adequate data for ML techniques. For candidate problem areas, there are then four key user-centred questions that must be answered:

Figure 1.

Toolkit for integrating user-centred design into the problem definition stages for ML development in healthcare. ML, machine learning; UXR, user-experience research.

Q1. Where are the current pain points?

Q2. Where could ML add unique value?

Q3. How will the model output be acted on?

Q4. What criteria should the model be optimised for?

The above toolkit was applied through a series of six user-experience research (UXR) workshops with multidisciplinary stakeholders, including care managers, nurses, population health leaders and physicians affiliated with a managed care programme at Stanford Health Care. Workshops were conducted virtually and were approved by Stanford and Advarra Institutional Review Boards, with consent obtained from all participants.

The schedule of workshops is detailed below:

Workshop 1 focused on mapping existing workflows. The output was a set of process maps, annotated with pain points.

Workshop 2 focused on where ML could add unique value (Q2). This yielded a mapping between pain points and possible ML formulations, categorised into automation (replicating repetitive, time-consuming tasks) versus augmentation (adding superhuman functionality).8

Workshops 3 and 4 focused on how a model output would be acted on (Q3). Low-fidelity study probes were developed—storyboards of how an ML tool might fit into a clinical workflow. These were presented to participants for feedback and refined iteratively.

Workshops 5 and 6 explored ML evaluation metrics for the most promising concept designs. This included how care managers would expect results to be presented and any auxiliary information required alongside the main model output (Q4)

Results

What are the current pain points?

The following pain points were identified:

Identifying and prioritising the highest risk patients.

Extracting relevant risk factors from the electronic health record.

Selecting effective interventions.

Evaluating intervention efficacy.

Where could ML add unique value?

Risk stratification (pain point number 1) emerged as an opportunity for ‘augmentation’ given the challenges in forecasting future deterioration. The ML formulation was a model to predict adverse outpatient events, with emergency department visits and unplanned chronic disease admissions chosen as the prediction endpoints (online supplemental table S1). Identifying risk factors (pain point number 2) was classed as an opportunity for ‘automation’ given that there is a large volume of unstructured clinical data to sift through. The proposed ML formulation was a natural language processing tool for summarising clinical notes and extracting modifiable risk factors. Selecting interventions and evaluating efficacy (pain points number 3 and 4) were also classed as augmentation opportunities. The ML formulation involved causal inference approaches to estimate individualised treatment effects.

bmjhci-2022-100656supp001.pdf (160.9KB, pdf)

How will the model output be acted on?

Online supplemental figure S1 shows example workflows and storyboards addressing the first two ML formulations above. The actionability pathway for risk scores and personalised risk factor summaries is that care managers can more rapidly prepare for calls and more effectively target their calls to patients with modifiable risk. These risk summaries could be presented to care managers on a monthly basis alongside the existing rule-based lists for high-risk patients. To mimic the existing workflow, the triggering frequency for inference was set as monthly and the inclusion criteria were tailored to fit the managed care population.

What criteria should the model be optimised for?

Since care managers have a limited capacity of patients whom they can contact, precision (positive predictive value) at c (where c is capacity) was selected as the primary evaluation metric. The value of c could be set either as a percentage of the total attributable population (more generalisable across health systems) or as a fixed value (more realistic given care manager staffing does not directly scale with patient load). We also selected realistic baselines to compare the ML models against—namely, rule-based risk stratification heuristics such as selecting recently discharged patients or those with high past utilisation.10

Discussion

We applied a practical toolkit for user-centred design, involving four key questions about pain points and ML formulations, via a series of participatory design workshops with care management teams. This guided us towards the pain points of outpatient risk stratification and risk factor identification, with ML formulations involving personalised risk scoring and extraction of potentially modifiable risk factors from the notes. Critical choices about the setup of the ML model were informed by workflow considerations—namely, the endpoint definition, the triggering frequency and the inclusion criteria. Importantly, the evaluation metrics must be tailored to a care management workflow. In this case, there was a capacity constraint on how many patients a care manager can contact each day or week. Hence, the most pragmatic metric was the precision of the model on the top c highest risk patients, rather than global accuracy metrics such as area under the curve of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC-AUC) or precision recall curve (PR-AUC).

This study is limited in only focusing on a single clinical use-case and only using workshops and concept probes as a medium for UXR, given the challenges around direct field observation during the pandemic. Future work will showcase the results of the ML models generated from this UXR collaboration.

Conclusion

User-centred design is important for developing ML tools that address a real clinical pain point and dovetail with existing workflows. An iterative approach involving stakeholder interviews and concept feedback can be used to identify pain points, pinpoint where a model could add unique value, understand the actionability pathway and prioritise evaluation metrics.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the leadership and clinical staff of the Stanford University HealthCare Alliance.

Footnotes

Twitter: @martin_sen

MGS and RCL contributed equally.

Contributors: MGS, RCL, NS devised the project. MS led the UX study sessions with support from MGS, LV, DL-M, DW, KE-K, LTF, JBK, EL, M-JC, PG, RCL, KEM, NLD, JD, JHC. MGS and RCL wrote the initial draft and all other authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Google (N/A).

Competing interests: This research was funded by Google LLC. LF is now an employee of Marpai Inc. but work for this paper was completed at Google.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Seneviratne MG, Shah NH, Chu L. Bridging the implementation gap of machine learning in healthcare. BMJ Innovations 2019. 10.1136/bmjinnov-2019-000359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone EG. Unintended adverse consequences of a clinical decision support system: two cases. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018;25:564–7. 10.1093/jamia/ocx096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JP, Cao T, Viviano JD, et al. Problems in the deployment of machine-learned models in health care. Can Med Assoc J 2021;193:E1391–4. 10.1503/cmaj.202066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li RC, Asch SM, Shah NH. Developing a delivery science for artificial intelligence in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:107. 10.1038/s41746-020-00318-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waring J, Lindvall C, Umeton R. Automated machine learning: review of the state-of-the-art and opportunities for healthcare. Artif Intell Med 2020;104:101822. 10.1016/j.artmed.2020.101822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillies M, Fiebrink R, Tanaka A. Human-Centred machine learning. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference extended Abstracts on human factors in computing systems. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016: 3558–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott KW, Jiang HJ. Statistical Brief #259: Characteristics and Costs of Potentially Preventable Inpatient Stays, 2017, 2020. Agency for healthcare research and quality (AHRQ). Available: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb259-Potentially-Preventable-Hospitalizations-2017.jsp [PubMed]

- 8.Google . People + AI research (pair) Guidebook. Available: https://pair.withgoogle.com/guidebook

- 9.Stanford d.school . Resources: start with design. Available: https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/get-started-with-design

- 10.Baker JM, Grant RW, Gopalan A. A systematic review of care management interventions targeting multimorbidity and high care utilization. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:65. 10.1186/s12913-018-2881-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjhci-2022-100656supp001.pdf (160.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.