Abstract

Objective

To scope all published information reporting on the feasibility, cost, access to rehabilitation services, implementation processes including barriers and facilitators of telerehabilitation (TR) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries (HICs).

Methods

A comprehensive electronic search of PubMed, Scopus, PEDro, Cochrane library, EBSCOhost (Academic search premier, Africa-wide information, CINAHL, Eric, MEDLINE, Health sources - Nursing/Academic edition), Africa online, as well as ProQuest databases were conducted. To maximise the coverage of the literature, the reference lists of included articles identified through the search were also screened. The analysis included both descriptive summary and inductive thematic analysis.

Results

Twenty-nine studies were included. TR was reported to be feasible, cost-saving and improved access to rehabilitation services in both HICs and LMICs settings. Asynchronous methods using different mobile apps (Skype, WhatsApp, Google meet, Facebook messenger, Viber, Face time and Emails) were the most common mode of TR delivery. Barriers to the implementation were identified and categorised in terms of human, organisational, technical and clinical practice related factors. Facilitators for health professionals and patients/caregivers’ dyads were also identified.

Conclusion

TR could be considered a feasible service delivery mode in both HICs and LMICs. However, the mitigation of barriers such as lack of knowledge and technical skills among TR providers and service users, lack of secure platform dedicated for TR, lack of resources and connectivity issues which are particularly prevalent in LMICs will be important to optimise the benefits of TR.

Keywords: Access, barriers, cost, facilitators, feasibility, impact, rehabilitation, telerehabilitation

Introduction

Telerehabilitation (TR) is an emerging segment of telehealth and telemedicine that holds promise for enhanced access to cost-efficient quality rehabilitation services particularly where the geographical distance bars access to care.1–4 TR falls under both categories of telehealth care and telemedicine. Telehealth refers to the management of disability and health, whereas telemedicine refers to delivery of clinical services, thus the term ‘telerehabilitation’ refers to clinical services for the management of disability and health .5 The term ‘telerehabilitation’ encompasses a range of rehabilitation services that include assessment, monitoring, therapy, prevention, supervision, education, consultation, counselling and coaching.6–8

TR is equally effective as face-to face care across a range of conditions.2–4 However, its overall implementation has been slow among health care providers globally, and even slower in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Before COVID-19 outbreak, TR was viewed as an optional health care service.9 The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of TR as a potential means for vulnerable groups such as people with disability to continue to gain access to rehabilitation services.

The World Health Organization (WHO) found that rehabilitation was most disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation of the impact of future pandemics should be planned. The rehabilitation community plays a significant role in exploring service modes such as TR to inform health policy makers and planners of its feasibility and affordability for scalable uptake in the local context.

Due to the shift in paradigm from TR as an alternative to an integral part of the health system, it is important to systematically evaluate its feasibility, cost implications and implementation processes (including barriers and facilitators) to guide health planners, educators and clinicians who wish to strengthen TR as in their health systems. This information will particularly be relevant for LMICs with weak health systems.

According to the World Bank Methods for the current 2023 fiscal year, low-income economies are defined as those with a General National Income (GNI) per capita, of $1086 and $4255; upper middle-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of between $4256 and $13,205; and high-income economies are those with a GNI per capita of $13,205 or more.10

Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to scope all published information reporting on the feasibility, cost, access to rehabilitation services and implementation process including barriers and facilitators of TR in HICs as well as LMICs.

The review objectives are to describe

The feasibility and cost of TR

To what extent TR impact on access and quality of rehabilitation services

The key process factors (including barriers and facilitators) relevant to the implementation of TR in LMICs.

Methodology

A scoping review method was selected because it enables mapping of exploratory research by systematically searching and synthesising exiting knowledge without critically appraising the methodological quality. Scoping reviews aim to examine the amount, range and nature of empirical and conceptual research activity in a broad topic area.11 The methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley,12 enhanced by Levac et al.13 and refined by Peters et al.,14 was applied to extract and synthesise the data. The five stages proposed in this framework are: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collecting, summarising and reporting the results.12

Identifying research questions

Scoping review questions are naturally broad and the aim of these types of reviews is to summarise the range of evidence in the area of interest. Following the initial engagement and gaining familiarity with the existing literature, the following questions were identified: (1) Is TR feasible and cost-saving especially in LMICs settings? (2) Does TR have a potential impact on access to/and quality rehabilitation services especially in LMICs settings? (3) What are potential barriers and facilitators to implementation of TR?

Identifying relevant studies (information source)

A comprehensive electronic search of PubMed, Scopus, PEDro, Cochrane library, EBSCOhost (Academic search premier, Africa-wide information, CINAHL, Eric, MEDLINE, Health sources - Nursing/Academic edition), Africa online, as well as ProQuest databases were conducted from July 2021 to March 2022. To maximise the coverage of the literature, the reference lists of included articles and reviews identified through the search were also screened. To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to report at least on feasibility of TR, cost of TR compared to centre-based rehabilitation services, the role of TR in terms of access to rehabilitation services, and its implementation process including barriers and facilitators. Studies could be of any design except reviews.

Inclusion: Included in this review are feasibility studies, randomised control trials (RCTs), surveys, case reports and a pilot study. Only studies that were published within and after 2010 (to depict the most recent, relevant information) with full text available in English were included.

Exclusion: We excluded systematic and literature reviews. However, we hand searched articles included in systematic and literature reviews for eligible studies to be included in this review.

Search strategy

In consultation with the librarian of the University of Stellenbosch, the review team developed the search strategy. The search strategy was developed using Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] ‘telerehabilitation’ ‘telehealth’, ‘telemedicine’, and text words related to terms included in the objectives of this review. Table 1 contains search terms and strategies that were used to identify the relevant studies for this review:

Table 1.

Search terms

| Concept 1 | Concept 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Telemedicine [MeSH] OR | Access* OR | |

| Telerehabilitation [MeSH] OR | Barrier*[tiab] OR | |

| Telehealth [MeSH] OR | AND | Challeng*[tiab] OR |

| ‘Tele physiotherapy’ [tiab] OR | Facilitat*[tiab] OR | |

| ‘Tele-physiotherapy’ [tiab] OR | Cost [tiab] OR | |

| ‘Tele therapy’ [tiab] OR | Implement*[tiab] | |

| ‘Tele-therapy’ [tiab] OR | ||

| ‘Tele-occupational therapy’ [tiab] OR | ||

| ‘Tele-audiology’ [tiab] OR | ||

| Rehabilitation [tiab]NOT | ||

| Telemedicine |

Study selection (screening)

Based on pre-determined criteria, the principal reviewer (NE) screened the abstract of all hits to identify potentially eligible articles. Full text of potentially relevant papers was screened by NE, and CJ & Q L independently verified the accuracy and eligibility inclusion of papers in instances where NE was uncertain.

Charting the data (data extraction)

Data charting is a method which allows researchers/reviewers to capture a breadth of information and details on processes to provide further context to the research outcomes.13 The review team developed a standardised data charting form and piloted it on four randomly selected studies. The extraction form included information on: 1) authors and year of publication; 2) country where the study was conducted; 3) aim and objectives of the study, 4) study design; 5) implementation processes (mode and methods of delivery: e.g., videoconferencing, mobile apps, emails, telephone calls or SMSs, synchronous (real time) or asynchronous); 6) outcomes (e.g., feasibility, cost, access to rehabilitation services, continuity of care), and 7) barriers and facilitators to implementation. The form was modified based on experiences of extracting data from each of the four (pilot) studies.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results (synthesis of the results)

To increase the methodological rigour of the scoping review, Lavac et al.13 suggested that this section be divided into three separate foci including analysing the data, reporting results and applying the meaning to the results. Our analysis included both descriptive summaries and inductive thematic analysis. We descriptively summarised the study characteristics and the evidence extracted from all sources was narratively summarised into key themes. To synthesise results, we formed clusters of similar publications by classifying the data items collected. This method allowed us to analyse and compare evidence of TR within each publication cluster.

Results

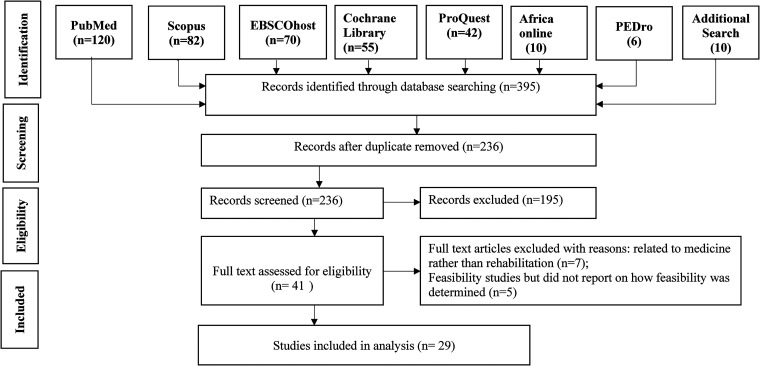

The search resulted in 236 records (after the duplicates were removed) that were considered relevant and were selected for abstract screening. After reading the abstracts, 195 studies were excluded resulting in 41 articles eligible for full-text review. Twelve studies were further excluded leaving 29 studies included in the review. The identification and selection process of the studies are described based on modified Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA-ScR).15 Figure 1 depicts the flow diagram outlining the selection process for the studies included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram outlining the selection process for the studies included in the review.

Characteristics of included studies:

Figure 2A and 2B present the distribution of included studies by geographic area and year of publication. 10 studies (34%) were conducted in Europe, 7(24%) in North America, 6 (21%) in Asia, 4 (14%) in Australia, 2 (7%) in Africa. The largest number (n = 10) were conducted in 2020 and only 1 study was conducted in 2011 and 2014, respectively. No study was published in 2010.

Figure 2.

(A) The distribution of included studies by geographical area. (B) Summary of included studies based on the year of publication.

The detailed characteristics of included studies are provided in Table 2. More than half (n = 16) were feasibility studies; 5 randomized control trial (RCTs); 5 surveys; 2 case reports and 1 pilot study. In 14 studies, TR was delivered asynchronously, 11 studies used synchronous video conferencing, while 4 studies used a combination of synchronous and asynchronous delivery modes.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of included studies.

| First author Yea of Publication | Aim | Country Low/high income | Design | Targeted Population/ Problems | Enrolled (Gender) | Completed (Gender) | Reason for participant drop-out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdolahi et al., 2016 16 | To evaluate the feasibility and potential validity of assessing the Montreal Cognitive Assessment tool remotely in patients with Parkinson and Huntington diseases using web-based video conferencing | USA High income |

Feasibility | Patients with Parkinson disease (PD) and Huntington disease (HD) |

17 (Gender not mentioned) | All participants Completed the Program |

N/A |

| Bernocchi et al., 2015 17 | To evaluate the feasibility of Implementing a home-based tele-Surveillance | Italy High income |

Feasibility | Post- stroke Patients |

26 (Gender not mentioned) | 23 (Gender not Mentioned) |

dropped out due to: Hospitalisation, for respiratory problems (n = 1); Femoral fracture (n = 1); subarachnoid haemorrhage following a fall (n = 1). |

| Dimitropoulos et al., 2017 18 | To evaluate the feasibility of play-based TR program with children with Prader Willi syndrome | USA High income |

Feasibility | Children with Prader Willi Syndrome |

10 (7 males &3 females) | 8(Gender no mentioned |

2 withdrawn during the program due to inability to dedicate time to the intervention program |

| Dobbs et al., 2018 19 | To determine the generalizability of RS-tDCS paired with cognitive training (CT) by testing its feasibility in participants with Parkinson's disease (PD). | USA High income |

Feasibility | Patients with Parkinson disease |

16 (12 males &4 females) | 15 (Gender not Mentioned) |

One participant was discontinued from treatment after two study sessions due to a medical issue (cardiac event) |

| Hwang et al., 2017 20 | To describe the perspectives of a group-based heart failure (HF) TR program delivered to homes via online videoconferencing | Australia High income |

Feasibility | Patients with heart failure |

17(88% males) | All participants Completed the program |

N/A |

| Jahromi et al., 2017 21 | To assess the satisfaction of patients with stutter concerning the therapeutic method and the infrastructure used to receive tele-speech therapy services | Iran LMIC |

Feasibility | Patients with Stutter |

30 (17 males & 13 females) | All participants completed the program |

N/A |

| Kikuchi et al, 2021 22 | To evaluate the feasibility of real time monitoring system for home-based cardiac rehabilitation among elderly with heart failure. | Japan High income |

Feasibility | Cardiac Patients |

10 (6 males & 4 females) | All participants Completed |

N/A |

| Negrini et al. 2020 23 | To investigate the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine as substitute for outpatients services in emergency situation such as COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy | Italy High income |

Feasibility | Patients with spinal disorders | 1207 (Gender not mentioned) |

All participants completed | N/A |

| Odetunde et al., 2020 24 | To determine feasibility of video-based home exercise program (VHEP) in Yoruba language | Nigeria LMIC |

Feasibility | Chronic stroke survivor patients |

10(5 males & 5 females) | All participants completed | N/A |

| Ora et al., 2020 25 | To investigate the feasibility augmented TR in post- stroke |

Norway High income |

Feasibility | Post-stroke Aphasia |

30 (19 males &11 females) | All participants completed |

N/A |

| Peel et al., 2011 26 | To determine the feasibility of delivering rehabilitation remotely to aged clients using eHABTM video-conferencing system | Australia High income |

Feasibility | Older people with disabilities |

3 (Gender not mentioned) | 2 (Gender not mentioned) | 1 person did not complete the trial because of their

condition worsened |

| Piraux et al., 2020 27 | To determine the feasibility of Pre-surgery TR program |

Belgium High income |

Feasibility | Esophagogastric Cancer patients |

23 (Gender not mentioned) | 15 (Gender not mentioned) |

Withdrawal (n = 4); excluded due to disease progression (n = 2) Died during the program (n = 2) |

| Puspitasari et al., 2021 28 | To determine feasibility of program that switched from an in-person group to a video teletherapy group during COVID- 19 pandemic | USA High income |

Feasibility | Psychiatric patients | 76 (65 males &11 females) | 70 (Gender not mentioned) |

Excluded due to refusing to provide research authorization (n = 13) |

| Silva et al., 2020 29 | To determine feasibility of web-based education and exercise therapy | Australia High income |

Feasibility | Patellofemoral pain patients | 35 (27 females & 5 males) | All completed | N/A |

| Van Egmond et al., 2020 30 | To determine feasibility of supervised postoperative physiotherapy TR | Netherlands High income |

Feasibility | Oesophageal cancer patients | 22(17 males & 5 females) | 15 (Gender not mentioned) | Quit because: Preferred face to face physiotherapy(n = 3);

developed metastases (n = 1); required

multidisciplinary approach (n = 3) |

| Woolf et al., 2016 31 | To test the feasibility of a TR comparing to the remote and face to face therapy |

UK High income |

Feasibility | Post-stroke Aphasia |

21(Gender not mentioned) 56(Gender not mentioned) |

All participants completed |

N/A |

| Fatoye et al., 2020 4 | To evaluate cost effectiveness of TR compared to

clinic-based intervention |

Nigeria LMIC |

RCT | Chronic back pain patients |

56: TR-based Mackenzie therapy (n = 24) Clinic based Mackenzie therapy (n = 32) |

47: TR-based Mackenzie therapy(n = 21) Clinic-based Mackenzie therapy (n = 26) |

Discontinued (n = 3); Voluntary withdrawal (n = 6) |

| Frederix et al., 2016 3 | To evaluate cost-effectiveness of comprehensive TR program | Belgium High income |

RCT | Cardiac patients | 140 (Gender not specified) TR (n = 70) Usual care (70) |

126 TR (n = 62) Usual care (n = 64) | CT problems (n = 2); logistics problems (n = 7); new pathology (n = 3); Lost interest (n = 2) |

| Hwang et al., 2017 32 | To determine the efficacy and safety of short

term Telerehabilitation program |

Australia High income |

RCT | Heart failure Patients |

53 (75% males) Telerehab (n = 24) Standard rehab (n = 29) |

49 (Gender not mentioned Telerehab (n = 23) Standard rehab (n = 26) |

Lost at 12 weeks follow-up: Tele-group: none Control group: (n = 3) |

| Pastora-Bernal et al, 2017 33 | To compare costs of TR Vs conventional physiotherapy |

Spain High income |

RCT | Subacromial Problem |

18 (10 males and 8 females) | All patients completed the |

N/A |

| Tousignant et al., 2015 2 | To compare the real cost of in-home TR and

conventional home visits (VISIT) |

Canada High income |

RCT | Total knee Arthroplasty patients |

205(Gender not mentioned) TR group (n = 104) VISIT group (n = 101) |

195 TR group (n = 94) VISIT group (n = 101) |

Unsatisfied with with randomization ( = 6); poor internet connection (n = 3) Self-perception of recovery (n = 1) |

| Aloyini et al., 2020 34 | To explore knowledge, attitude and barriers to

the Implementation of TR in physical therapy |

Saudi Arabia High Income |

Survey | Physiotherapists in public and Private hospitals |

347 (106 males and 70 Females) |

347(106 males and 70 Females) | N/A |

| Buckingham et al., 2020 35 | To assess training needs and collate ideas on best practices in TR for physical disabilities and movement impairment. | UK High income |

Survey | Health professionals | 245 (202 female &35 male) | All completed the survey | N/A |

| Damhus et al., 2018 36 | To examine barriers and enablers of online based TR | Denmark High income |

Survey | Health professionals | 25(Gender not

mentioned) Physiotherapists(n = 19) Nurses (n = 6) |

All 25 participants Completed the Program |

N/A |

| Hermes et al., 2021 37 | To discern barriers to TR in primary rural states | USA High income |

Survey | Health professionals | 46(gender not

mentioned) Speech-language therapists (n = 32) Occupational therapists (n = 12) |

46 Speech-language therapists (n = 32) Occupational therapists (n = 12) |

N/A |

| Tyagi et al., 2018 38 | To explore perceive barriers and facilitators of TR |

Singapore High income |

Survey | Stroke patients Care givers & Therapists |

31(Gender not mentioned) Patients (n = 13) Caregivers (n = 13) Therapists (n = 5) |

31 Patients (n = 13) Caregivers (n = 13) Therapists (n = 5) |

N/A |

| Leochico et al, 2020 39 | To conduct a wheelchair follow-up via TH |

Philippine LMIC |

Case report | Patients with Paraplegia |

2(1 male and 1 Female) | 2 (1 male and 1 Female) |

N/A |

| Luxamana et al., 2018 40 | To determine feasibility of TR | Philippine LMIC |

Case report | Parkinson's Disease patient |

1 female patient | 1 female patient | N/A |

| Adler et al., 2014 41 | To identify barriers and facilitators of TR implementation |

USA High income |

Pilot study | Health professionals | 12: Psychologists (n = 7) Social workers (n = 3) Vocational therapists (n = 2) |

All 12 participants completed | N/A |

Feasibility

This review identified 16 studies that investigated the feasibility of TR programs for neurological conditions,16–19,21,23–25,28,31 medical conditions,20,22,27,30 neuromusculoskeletal disorders,29 as well as older people.26 Fourteen (14) out of 16 studies 16–20,22,23,25–31 were conducted in HICs and only 2 studies 21,24 in LMICs. Feasibility was determined by recruitment rate, retention rate, attendance/adherence to the program, completion rate, satisfaction, adverse events and technical faults during the implementation. In most cases, health professionals monitored TR program though telephone calls and emails (in case of asynchronous) and video conferencing (in case of synchronous). During the monitoring phase, therapists provided feedback and modification of therapy as required. The overall satisfaction ranged between good and very good, the retention, adherence and completion rate were very high and adverse events were very low. Table 3 summarises the key findings of the feasibility studies.

Table 3.

Feasibility outcomes.

| Feasibility outcome measures | Authors | Outcomes/findings |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment rate | Piraux et al., 202027. | 1 of 24 (5%) declined |

| Odetunde et al., 202024 | 100% (n = 10) recruited within 1 week | |

| Silva et al., 202029 | 100% (n = 35) recruited within 18 weeks | |

| Attendance/Adherence | Piraux et al., 202027 | 77% attendances in aerobic 68% attendance in resistance training |

| Puspitasari et al., 202128 | Attendance ranged from 8 to 15 sessions | |

| Odetunde et al., 202024. | 100% adhered to the exercises | |

| Van Egmond et al., 202030 | 99% adherence in the first 6 weeks 75% in the following 6 weeks. |

|

| Silva et al., 202029 | Average of 4 face -to-face sessions Average of 5 TR sessions. |

|

| Completion of intervention | Puspitasari et al., 202128 | 70 of 76 (92%) completed |

| Ora et al., 202025 | 30 of 30 (100%) completed | |

| Woolf et al., 201531 | 21 of 21(100%) completed | |

| Kikuchi et al., 202122 | 10 of 10 (100%) completed | |

| Piraux et al., 202027 | 15 of 22 (68%) completed | |

| Puspitasari et al.,202128 | 70 of 76 (92%) completed | |

| Odetunde et al., 202024 | 10 of 10 (100%) completed | |

| Silva et al., 202029 | 35 of 35 (100%) completed at 6 weeks follow-up 31 of 35 (88%) completed at18 weeks follow-up |

|

| Satisfaction | Odetunde et al., 202024 | Use of Yoruba video- based home exercise program was well received |

| Van Egmond et al., 202030 | Satisfaction measured by telemedicine satisfaction and useful questionnaire (TSUQ) at T1 was 135.0 (SD = 19.5). | |

| Negrini et al., 202023 | High satisfaction | |

| Ora et al., 202025 | 93% of participants were satisfied | |

| Hwang et al., 201720 | Moderate to high satisfaction | |

| Bernocchi et al., 201517 | 100% of participants were satisfied | |

| Adverse events Technical faults. during implementation | Piraux et al., 202027. | The satisfaction was excellent |

| Van Egmond et al., 202030 | No adverse events | |

| Silva et al., 202029 | Events unrelated to the trial (n = 3), knee pain (n = 11). Fall (n = 2) | |

| Dobbs et al.,201819 | Cardiac issue (n = 1) | |

| Piraux et al., 202027 Bernocchi et al., 201517 Ora et al., 202025 |

No exercise adverse events Episodes of atrial fibrillation (n = 8) 86 faults occurred out of 541 video sessions provided. |

|

| Abdullahi et al., 201616 | Slow internet connection speeds (n = 5) |

Cost and access to rehabilitation services

The studies which discussed the cost and access to TR services in relation to usual care, are presented in Table 4. Four (4) of the 6 intervention studies 2–4,33 evaluated the cost of TR in comparison to the usual care (control group) of which only 1 study 4 was conducted in LMICs. Two (2) studies32,39 reported on access to rehabilitation services. In general, the findings indicate that TR was cost saving compared to usual care, improved access to rehabilitation services and specialised rehabilitation professionals while overcoming the barriers associated with distance, travel time and transportation costs.

Table 4.

Interventions and implementation processes for telerehabilitation.

| Authors, Year and place of Publication | Intervention | Control | Frequency | Duration | Mode of delivery | Outcomes/results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tousignant et al., 20152 (HIC) | In-home TR Vs Home visit | Conventional home-visit (VISIT) | 2 × per week | 8- weeks | TR: Delivered by real time video-conferencing

(Synchronous) VISIT: delivered by the Physiotherapist at the patients’ homes |

TR was not inferior to face-to-face in terms of rehabilitation efficacy. The mean cost of single sessions for TR was = $ 33.70 and $26.60 for VISIT. The real total cost analysis showed a cost differential in favor of TR. |

| Frederix et At, 20153 (HIC) | TR in addition to conventional rehabilitation | Conventional rehabilitation alone | 2 × per week 45 sessions per week 45–60 min Per session |

24 weeks Tele rehab 12 weeks Conventional rehab |

TR: delivered via emails and text messages.

(Asynchronous) Conventional rehab: delivered at the rehab center. |

The number of days lost due to cardiovascular rehospitalization was significantly lower in TR group than in control group and the average cost per patient was lower in TR group (E272_E126) than in conventional group (E272_E276) |

| Fatoye et al., 20204 (LMIC) | TR- based Mackenzie therapy (TBMT) Vs Conventional Mackenzie therapy | Clinic-based Mackenzie therapy (CBMT) | 3 × per week | 8- weeks | TBMK: delivered by video

via Mobile-based app. (Asynchronous) CBMT: Delivered at rehab center |

TBMT arm was associated with an additional 0.001 QALY (95% CL 0.001 to 0.002) per participant and the mean cost of TBMT and CBMT was $ 61.7 and $. 106 respectively. The TBMT was cost-saving and more effective compared to CBM. |

| Pastora-Bernal et al., 201733 (HIC) | TR Vs traditional physiotherapy | Traditional Physiotherapy |

5 × per week | 12-wees | TR: delivered by use of Videos, Emails, images

(Asynchronous) Traditional physiotherapy: delivered at the rehabilitation center. |

Total intervention in TR saves 21.15% of the costs incurred for the conventional rehabilitation. |

| Hwang et al., 201732 (HIC) | TR- based exercises Vs Hospital- based rehabilitation program | Traditional hospital outpatient-based exercises | 2 × session per Week, 60 min per session |

12-weeks | TR: delivered via video-conferencing platform

within patients’ homes.

(Synchronous) Traditional hospital-based program: delivered in the outpatient department. |

A significantly higher attendance rate was observed in the TR group compared to the hospital-based group. Increased access to care and increased social support were reported in TR group |

| Leochico et al., 202039 (LMIC) | Teleconsultation | No control group | Not mentioned | Not Mentioned | Teleconsultation done through

phone calls, video conferencing using patients’ own device (Synchronous and Asynchronous) |

TR increased access to

rehabilitation services by overcoming barriers of distance and transportation cost |

Barriers to the implementation of telerehabilitation

Several barriers to the implementation of TR were identified and grouped into human, organisational, technical and clinical practice categories. Four studies 21,38–40 out of 11 which reported the barriers to TR were conducted in LMICs. Connectivity issues, lack of TR knowledge and technical skills were the most barriers identified in our review of which connectivity issues (poor or slow internet connection) were reported in all 11 studies (100%) that reported barriers to TR. Most of the barriers identified are inter-related, meaning that one barrier might lead to another while removing one barrier might facilitate another. The detailed information about this inter-relationship is provided in detail in the discussion section of this review. Table 5 summarises the barriers that were identified in each category.

Table 5.

Barriers to telerehabilitation implementation.

| Categories | Barriers[references] |

|---|---|

| 1. Human | |

| 2. Organizational | |

| 3. Technical | |

| 4. Clinical practice |

Facilitators of telerehabilitation implementation

Some facilitators to implementation of TR were also identified by different stakeholders (health professionals, patients and caregivers). Familiarity of the system (technical skills) and ease of use were the most important facilitators reported by both health professionals and patients/caregivers' dyads. Table 6 summarises the facilitators identified.

Table 6.

Facilitators of telerehabilitation implementation.

| Categories | Facilitators [references] |

|---|---|

| Health professionals | |

| Patients/Caregivers |

Discussion

This is the first scoping review that reports on the feasibility, access and cost of TR as reported in the 29 publications. Overall, the findings regarding the feasibility of TR were positive, despite a number of barriers which may bar scalable use of TR in LMICs if not adequately addressed.

Feasibility

More than half of the eligible papers (55%) investigated the feasibility of TR program in different topic areas of which only two studies21,24 were conducted in LMICs. This is an indication that despite the popularity TR is gaining in HICs, its use in LMICs is still in the infancy stage and that it has not penetrated well in these areas. According to Scott and Mars,42 the main reasons why telehealth has not been integrated well into existing health system in the LMICs includes limited resources, unreliable power, poor connectivity, and high cost for those in need. However, our review highlights that these barriers are also common in HIC settings. Thus, collaborations within and outside the health system to co-developing strategies to overcome these barriers are needed and will increase TR opportunities for more end-users.

Medical insurances/schemes are quite diverse from different countries around the world and may play a big role in implementation of TR especially in HICs where medical insurances are most likely to be affordable. The lack of medical insurance/scheme reimbursement in LMICs might also be another reason why TR has not gained popularity in these areas. Thus, moving towards the universal health coverage that include TR services might facilitate the use of TR in LMICs.

Although, our review identified only two studies investigating the feasibility of TR in LMICs, the general findings were not different between the HICs and LMICs. All of the studies we reviewed showed positive feasibility findings. This signals that integrated TR platforms might be an alternative option to address the challenging problems faced by patients who are unable to participate in centre-based rehabilitation programs due to geographical distance, barriers associated with travel time, and transportation costs. Transport (cost, poor road quality, access to transport, poor public transportation systems) related factors are well reported barriers to access of rehabilitation in many LMICs.4,32,39 Therefore, if the health system can move towards the support of digital systems for patients and clinicians to access rehabilitation, TR may become an attractive service mode in LMICs to enhance access in a cost-efficient way. Strengthening of TR in weaker health systems may contribute to reducing inequality in access to rehabilitation services in LMICs.

Cost and access to rehabilitation services

While the need of rehabilitation services is increasing significantly, healthcare access through traditional models of healthcare is often expensive especially in LMICs with weak healthcare systems. Our review demonstrated that TR has a lot of potential in lower resource settings if barriers can be addressed. All four studies reporting on the cost demonstrated lower costs in favour of TR. 2–4,33 This is consistent with a previous study conducted in rural India to estimate the therapists' salary, traveling and communication costs that is applicable for face-to-face delivery, which found that the mean cost of 12 sessions over four weeks was approximately $ 100 less in TR group compared to face-to-face group.43

The findings of this review demonstrated a correlation between cost-saving and access to healthcare services through TR. This is because eliminating the need to travel to the day rehabilitation centre and not to have to pay the transportation and parking costs as well as flexibility nature of TR program enhanced affordability, convenience, and consequently facilitating more access to rehabilitation services..20,21,38,39 Improved healthcare services through TR while reducing barriers related to time and distance has been previously reported in the literature.44 Our findings also showed that the reduced cost of care did not compromise patients’ satisfaction and adherence to care (see Table 3). In addition, our findings show that TR can be as effective as face-face rehabilitation or even superior. 2–4,32,33,39 Therefore, these results indicate that TR could have a positive impact on the current challenges in health care systems especially in LMICs where resources are dwindling while the need for rehabilitation is increasing. If planned well to ensure that vulnerable communities are included, TR can be an important innovation to provide universal access to rehabilitation care and reduce inequality in rehabilitation services, especially in resource limited settings.

Telerehabilitation mode of delivery

Asynchronous methods using different mobile apps (e.g., Skype, WhatsApp, Google meet, Facebook messenger, Viber and Face time), as well as emails and text messages were the most common mode of TR delivery and monitoring.3,4,20,21,24,26,27,29,30,33,34,36–38,41 According to Hwang et al.,32 synchronous (real-time videoconferencing) TR might seem to be more beneficial because patients are able to demonstrate how they have been performing therapy, and rehabilitation professionals can directly monitor the accuracy of the therapy performed, modify and promote progress through practical demonstration.

Previous studies have also reported that synchronous mode of delivery might be more beneficial in some specific disease conditions. For example, video telehealth modalities have been reported to be especially helpful in general spinal cord injury (SCI) care as an efficient and convenient mode for follow-ups, discussing bowel and bladder concerns, or addressing spasticity and chronic pain issues that cannot be easily done via asynchronous mode of delivery.45,46 Video modalities can enhance remote care by allowing patients to see their provider, supporting clinical rapport and building interpersonal relationships and therapeutic alliance, while affording clinicians an opportunity to see home environments to gain insights regarding challenges impacting care.47

However, synchronous TR may have some limitations as it requires both the patient and therapist to be available at the same time and have access to high-quality screen and devices with the reliable highspeed internet connection. With connectivity issues that have been reported as major barrier to the implementation of TR in resource limited settings (Table 5), the synchronous mode of delivery might not be the best option especially in LMICs settings where health care systems are under-resourced and have poor internet connectivity. The asynchronous visual platform on mobile devises that use either short videos or images to exchange information without requiring simultaneous internet access might be the best mode of delivery for TR services especially in LMICs where internet connectivity might be a major barrier to synchronous mode of delivery.

Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of telerehabilitation

It is evident that most of reported barriers to the implementation of TR, if addressed could act as facilitators. For example, while lack of TR knowledge and technical skills among TR providers and service users are among the human and organizational barriers which are constantly reported to have made it difficult to adopt TR and, in some cases, leading to scepticism and resistance to change,32,34,36–39,41 service providers and users who had good knowledge about TR, and had technical skills needed for the implementation found it easy to accept and use TR technology.17,18,20,21,26,36 Therefore, it is very crucial that TR providers and service users have accurate knowledge about TR and its contribution to healthcare services. Service providers who have a good knowledge about TR and its benefits can easily become champions or innovators of the use of TR services.

Lack of exposure to technical skills to use the necessary electronic devices such as computers, tablets, smart phones by service providers and services users is a major issue that need to be addressed before TR can be adopted and be used effectively.48 Training of service providers and service users can enhance knowledge and skills needed for the use of TR technology, and acquiring knowledge and technical skills may lead to the ease of use, which in turn may lead to the acceptance of the technology. This will consequently eliminate the possible barriers that might be associated with service providers and users’ scepticism and resistance to change.

Good TR knowledge and technical skills can influence service providers and service users’ satisfaction and willingness to adopt and use TR technology, indicating the correlation between TR knowledge, technical skills and TR technology or innovation acceptance. In addition, it is also important that organisations wishing to use TR ensure that necessary infrastructures (such as dedicated space, hardwires and software), and administrative protocols are in place and that additional resources are available should further support be required. Lobbying for administrative support and funding to secure the necessary infrastructures is important for a successful implementation of TR.

The secure and strong internet connection is one of the most essential elements needed for both service providers and service users who seek to use TR technology. However, connectivity issues (poor and slow internet connection) are reported to have been a major barrier to TR in our reviewed studies that reported on barriers.16,17,20–22,34,36–39,41 Poor quality and slow speed internet during TR is most likely to result in poor video and audio quality, loss of connection which may in turn negatively affect both service providers and users’ interest for using TR services leading to resistance to change. Although faster internet was not mentioned among facilitators of TR in our reviewed studies, previous reports indicated that faster internet facilitate the implementation to TR.49,50 This may also indicate that there is a correlation between internet speed and service providers and users’ satisfaction and acceptance of TR. Therefore, healthcare planers and policy makers should invest on increasing bandwidth to improve the success of TR programs especially in LMICs where connectivity issues are the major barriers to the successful implementation of TR services.

Although TR might be a viable alternative for service delivery where traditional face-to-face intervention is not possible, it might also have some limitations in terms of providing comprehensive services. This is evident in the studies of which patient/care giver dyads and clinicians reported some barriers such as limited scope of exercises, limited patient assessment, interpersonal communication skills and feeling unsafe while doing TR.36,38 The issue of communication skills in telehealth has been previously reported. Souza-Junior51 argued that telehealth providers require high-level of communication skills to compensate for lack of visual cues. It is also important to note that some other studies have reported that clinicians' communication skills during TR helped them to deliver the best care for patients and contributed to the treatment plan.52,53 On the contrary, the lack of the clinicians training on communication skills affected the uptake of online consultation.26 Therefore, the training of clinicians on communication skills, specifically for TR is deemed very important for a successful implementation of TR.

Limitations

Firstly, this review included studies from both LMICs and HICs. Since TR is technology driven, and HICS are believed to have a better access to and knowledge of the use of technology compared to LMICs, this may limit the generalizability of review results depending on the context.

Secondly, most studies came from HICs. This may also hamper the generalizability to other similar contexts, particularly LMICs. However, the results should be interpreted using a pragmatic lens of what is affordable and possible in the setting where interested parties wish to explore the use of TR.

Thirdly, there is little information on the role of health planers and policy makers.

Lastly, only English papers were reviewed, and no methodological quality appraisal as it was not deemed necessary.

Conclusion

TR has the potential to be a cost-saving and effective mode to increase access to services and reduce inequality provided that key barriers are pro-actively addressed by key stakeholders. The key barriers included: lack of TR knowledge and technical skills among service providers and service users, patients and service provider's scepticism and resistance to change, lack of secure platforms, limited resources, connectivity issues, equipment related difficulties and lack of access to technology. Saving travel time and transportation costs, familiarity with the system, accessibility, affordability and convenience, motivation and engagement, support from families and caregivers, provision of feedback and technical support, and interpersonal communication skills acted as facilitators to TR. Further research focusing on how to integrate TR into the health system in LMICs to strengthen rehabilitation services is needed.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article

Ethical approval: As this is a scoping review of published literature, ethics approval is not required.

Guarantor: EN.

Contributor ship: EN was responsible for conceptualizing the study, collecting the literature, writing the first draft, and the last version of the manuscript. He managed the whole project. CJ assisted in conceptualization and approved the final version of the manuscript. NP assisted in writing the first draft and approved the last version of the manuscript. DG assisted in writing the first draft and approved the last version of the manuscript. QL assisted in conceptualization, assisted in the literature collection, and approved the last version of the manuscript.

ORCID iD: Eugene Nizeyimana https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0859-5013

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. Report on the second global survey on eHealth. World Health Organization; 2010.

- 2.Tousignant M, Moffet H, Nadeau Set al. Cost analysis of in-home telerehabilitation for post-knee arthroplasty. J Med Internet Res 2015; 17: e3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frederix I, Hansen D, Coninx Ket al. Effect of comprehensive cardiac telerehabilitation on one-year cardiovascular rehospitalisation rate, medical costs and quality of life: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23: 674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fatoye F, Gebrye T, Fatoye Cet al. et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of telerehabilitation for people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: randomised controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020; 8: e15375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winters JM. Telerehabilitation research: emerging opportunities. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2002; 4: 287–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richmond T, Peterson C, Cason Jet al. American telemedicine association’s principles for delivering telerehabilitation services. Int J Telerehabil 2017; 9: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cason J. Telehealth opportunities in occupational therapy through the Affordable Care Act. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2012; 66: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan D, Tindall L, Theodoros Det al. A blueprint for telerehabilitation guidelines. Int J Telerehabil 2010; 2: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leochico CF, Espiritu AI, Ignacio SDet al. et al. Challenges to the emergence of telerehabilitation in a developing country: A systematic review. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 1007–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 02 September, 2022.

- 11.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien KKet al. et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67: 1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010; 5: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil Het al. et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation 2015; 13: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PMet al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021; 10: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdullahi A, Bull MT, Darwin KCet al. et al. A feasibility study of conducting the Montreal Cognitive Assessment remotely in individuals with movement disorders. Health Informatics J 2016; 22: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernocchi P, Vanoglio F, Baratti Det al. et al. Home-based tele-surveillance and rehabilitation after stroke: a real-life study. Top Stroke Rehabil 2016; 23: 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimitropoulos A, Zyga O, Russ S. Evaluating the feasibility of a play-based telehealth intervention program for children with Prader–Willi syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 2017; 47: 2814–2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobbs B, Pawlak N, Biagioni Met al. Generalizing remotely supervised transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): feasibility and benefit in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2018 Dec; 15: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang R, Mandrusiak A, Morris NRet al. et al. Exploring patient experiences and perspectives of a heart failure telerehabilitation program: a mixed methods approach. Heart Lung 2017; 46: 320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahromi ME, Ahmadian L. Evaluating satisfaction of patients with stutter regarding the tele-speech therapy method and infrastructure. Int J Med Inf 2018; 115: 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kikuchi A, Taniguchi T, Nakamoto Ket al. et al. Feasibility of home-based cardiac rehabilitation using an integrated telerehabilitation platform in elderly patients with heart failure: a pilot study. J Cardiol 2021; 78: 66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negrini S, Donzelli S, Negrini Aet al. et al. Feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine to substitute outpatient rehabilitation services in the COVID-19 emergency in Italy: an observational everyday clinical-life study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020; 101: 2027–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odetunde MO, Binuyo OT, Maruf FAet al. et al. Development and feasibility testing of video home based telerehabilitation for stroke survivors in resource limited settings. Int J Telerehabil 2020; 12: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Øra HP, Kirmess M, Brady MCet al. et al. Technical features, feasibility, and acceptability of augmented telerehabilitation in post-stroke aphasia. Experiences from a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peel NM, Russell TG, Gray LC. Feasibility of using an in-home video conferencing system in geriatric rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med 2011; 43: 364–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piraux E, Caty G, Reychler Get al. et al. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of a tele-prehabilitation program in esophagogastric cancer patients. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puspitasari AJ, Heredia D, Coombes BJet al. et al. Feasibility and initial outcomes of a group-based teletherapy psychiatric day program for adults with serious mental illness: open, nonrandomized trial in the context of COVID-19. JMIR Ment Health 2021; 8: e25542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva DD, Pazzinatto MF, Crossley KMet al. et al. Novel stepped care approach to provide education and exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e18584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Egmond MA, Engelbert RH, Klinkenbijl JHet al. et al. Physiotherapy with telerehabilitation in patients with complicated postoperative recovery after esophageal cancer surgery: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res 2020; 22: e16056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf C, Caute A, Haigh Zet al. A comparison of remote therapy, face to face therapy and an attention control intervention for people with aphasia: a quasi-randomised controlled feasibility study. Clin Rehabil 2016; 30: 359–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang R, Bruning J, Morris NRet al. et al. Home-based telerehabilitation is not inferior to a centre-based program in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2017; 63: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pastora-Bernal JM, Martín-Valero R, Barón-López FJ. Cost analysis of telerehabilitation after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24: 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aloyuni S, Alharbi R, Kashoo Fet al. et al. Knowledge, attitude, and barriers to telerehabilitation-based physical therapy practice in Saudi Arabia. InHealthcare 2020; 8: 460. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buckingham SA, Anil K, Demain Set al. Telerehabilitation for people with physical disabilities and movement impairment: a survey of United Kingdom practitioners. JMIRX Med 2022; 3: e3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damhus CS, Emme C, Hansen H. Barriers and enablers of COPD telerehabilitation–a frontline staff perspective. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018; 13: 2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermes SS, Rauen J, O'Brien S. Perceptions of School-Based Telehealth in a Rural State: Moving Forward After COVID-19. Int J Telerehabil 2021; 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tyagi S, Lim DS, Ho WHet al. et al. Acceptance of tele-rehabilitation by stroke patients: perceived barriers and facilitators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018; 99: 2472–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leochico CF, Valera MJ. Follow-up consultations through telerehabilitation for wheelchair recipients with paraplegia in a developing country: a case report. Spinal Cord Series and Cases 2020; 6: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laxamana FE, Leochico CF, Espiritu AIet al. et al. Feasibility of Speech Telerehabilitation for a Patient with Parkinson's Disease in a Low-Resource Country during the Pandemic: A Case Report. Acta Medica Philippina. 2020.

- 41.Adler G, Pritchett LR, Kauth MRet al. et al. A pilot project to improve access to tele psychotherapy at rural clinics. Telemedicine and e-Health 2014; 20: 83–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott RE, Mars M. Telehealth in the developing world: current status and future prospects. Smart Homecare Technol Telehealth 2015; 3: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tousignant M, Boissy P, Corriveau Het al. et al. In home telerehabilitation for older adults after discharge from an acute hospital or rehabilitation unit: a proof-of-concept study and costs estimation. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2006; 1: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jafni TI, Bahari M, Ismail Wet al. et al. Understanding the implementation of telerehabilitation at pre-implementation stage: a systematic literature review. Procedia Comput Sci 2017; 124: 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sechrist S, Lavoie S, Khong CMet al. et al. Telemedicine using an iPad in the spinal cord injury population: a utility and patient satisfaction study. Spinal Cord Series and Cases 2018; 4: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Straaten MG, Cloud BA, Morrow MMet al. et al. Effectiveness of home exercise on pain, function, and strength of manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury: a high-dose shoulder program with telerehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95: 1810–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zulman DM, Verghese A. Virtual care, telemedicine visits, and real connection in the era of COVID-19. JAMA 2021; 325: 26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mbunge E, Batani J, Gaobotse Get al. et al. Virtual healthcare services and digital health technologies deployed during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Africa: a systematic review. Global Health Journal 2022: 102–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dorsey ER, Achey MA, Beck CAet al. National randomized controlled trial of virtual house calls for people with Parkinson's disease: interest and barriers. Telemedicine and e-Health 2016; 22: 590–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bull MT, Darwin K, Venkataraman Vet al. et al. A pilot study of virtual visits in Huntington disease. J Huntingtons Dis 2014; 3: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Souza-Junior VD, Mendes IA, Mazzo Aet al. et al. Application of telenursing in nursing practice: an integrative literature review. Appl Nurs Res 2016; 29: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams A, LaRocca R, Chang Tet al. et al. Web-based depression screening and psychiatric consultation for college students: a feasibility and acceptability study. Int J Telemed Appl 2014; 1: 580786–580786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillen S, Arredondo MT, Traver Vet al. et al. Multimedia telehomecare system using standard TV set. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2002; 49: 1431–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]