Abstract

Introduction: When deciding on which programs to rank or fellowships to enter, medical students and residents may assess the program's prestige and specialty training opportunities. This report aimed to analyze the demographics of orthopedic department chairs and program directors (PDs), focusing on the prestige of their orthopedic training and medical school. Secondary data included fellowship, higher-level education, sex, professorship, years of practice, and total published research.

Methods: We used U.S. News and Doximity to rank 192 medical schools and 200 orthopedic residency programs based on prestige rankings, respectively. We searched for the department chair, vice-chair, and PD via program websites, Council of Orthopaedic Residency Directors (CORD), Orthopedic Residency Information Network (ORIN), personal websites, LinkedIn, and Doximity. Subsequently, we searched for each individual’s demographic information, education and research history, employment history, and medical school attended.

Results: We gathered data on 268 orthopedic surgeons with leadership positions at academic hospitals. Of the 268, 115 were department chairs, 15 were vice-chairs, 126 were PDs, 11 were both the chair and PD, and one was vice-chair and PD. Of the 268 physicians, 244 physicians were male (91.0%), while 22 were female (9.0%). The average residency reputation ranking overall was 59.7 ± 5.7. More specifically, for chairs, the average was 57.0 ± 8.3 (p < 0.005), and for PDs, the average was 63.6 ± 8.0 (p <0.005). There was no significant difference between chairs and PDs (p = 0.26).

Conclusion: Orthopedic leaders were found to have trained at more prestigious programs. This trend could be explained by increased research opportunities at more prestigious programs or programs attempting to increase their own reputation. 9.0% of the leaders identify as female, which is comparable to the 6.5% of practicing female orthopedic surgeons. However, this further demonstrates a need for gender equity in orthopedic surgery. Assessing trends in the training of orthopedic surgeons with leadership positions will allow a better understanding of what programs look for in the hiring process.

Keywords: women, residency, ranking, orthopedics, program director, vice-chair, chair

Introduction

Historically, academic leadership positions such as the chair and program director (PD) were devoted to patient care, research, and teaching, but as the medical system evolves, there has been a shift toward administrative tasks [1]. Recent data has shown that department chairs specifically only spend 40 to 45% of their time on clinical activities, leaving 50 to 55% of their time for budgeting, staffing, financial management, negotiations, and contracting [2]. This information begs the question of whether the prestige of chairs’ and PDs' residency training is essential to their selection.

Past literature has analyzed the qualities and traits of orthopedic leadership, but there is minimal published literature analyzing what is academically required to attain one of these leadership positions [2,3]. Bi et al. recently published a paper analyzing demographic information, residency, and fellowship location of department chairs and PDs at academic institutions. While accounting for national subspecialty size, it was found that orthopedic oncology and orthopedic trauma surgeons were overrepresented while reconstructive surgeons were underrepresented amongst department chairs and PDs. Chairs had more publications than PDs and were more likely to be professors, while PDs were more likely to remain in the same program as their residency training [4].

One area of orthopedics that has gained much attention is the lack of females in leadership positions. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 2018 census found that self-reported females only made up 5.8% of the AAOS membership [5]. A study in 2021 showed only 2% of department chairs and 11.2% of PDs identified as female, which continues to lag behind the 5.8% found in the AAOS census [4]. However, in 2016, there was only one female department chair, showing that orthopedics is continuing to move towards becoming a more diverse field [6,7].

There is a paucity of literature on whether medical school or residency program reputation influences who is hired to academic orthopedic leadership positions. Literature has shown that medical school ranking plays a role in the orthopedic surgery match, while residency program reputation contributes to fellowship match results [8-10]. We hypothesize that those in academic orthopedic leadership positions attended medical school and orthopedic residency programs with higher reputation rankings.

This report aims to analyze the demographics of orthopedic department chairs and PDs, focusing on the prestige of their orthopedic training and medical school. Secondary data included fellowship, higher-level education, self-reported gender, professorship, years of practice, and total published research.

Materials and methods

Two hundred Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), Doctor of Medicine (MD), and Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) residency programs located in the United States as of December 2021 were identified. Program websites, CORD (Council of Orthopaedic Residency Directors) Orthopedic Residency Information Network (ORIN), personal websites, LinkedIn, and Doximity were searched for the PD, department chair, and vice-chairs and then subsequently searched for demographic information, education, research history, employment history, and medical school attended for each individual. If there was a discrepancy between information on program websites and other sources, data was recorded from the program websites. All data was gathered in March 2022.

Demographic data included the name of the residency program, professorship level, and sex. Professorship levels included professor, associate professor, assistant professor, professor emeritus, and non-professors. Education and research history included program and year of orthopedic internship and residency; name, year, and title of fellowship; the total number of publications, any master's training (MPH {Master of Public Health}, MBA (Masters in Business Administration}, etc.) or a PhD (Doctorate in Philosophy). The number of publications was obtained from the PubMed publications listed on each individual’s Doximity account. If that information was not available, the physician was searched on PubMed manually.

U.S. News rankings were used to determine the rankings of each medical school, while Doximity rankings for reputation and research were used for residency program rankings. The U.S. News research ranking is a composite score consisting of a peer assessment score (15%), residency director assessment score (15%), median Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) score (13%), median undergraduate grade point average (GPA) (6%), acceptance rate (1%), faculty resources (10%), total federal research activity (30%), and average federal research activity per faculty member (10%) [11]. Doximity calculates the reputation of residency programs by surveying each orthopedic Doximity member, verified by board certification, allowing each to nominate five programs while weighting each vote inversely to the size of alumni [12].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were status as chair, vice-chair, or PD and professor (professor, assistant professor, or associate professor) at their respective MD or DO ACGME accredited orthopedic residency programs. Exclusion criteria were physicians with interim positions, professor emeritus, non-professor or clinical professor, residency programs outside the 50 States of the United States (thus, excluding Puerto Rico), and residency training in a different specialty.

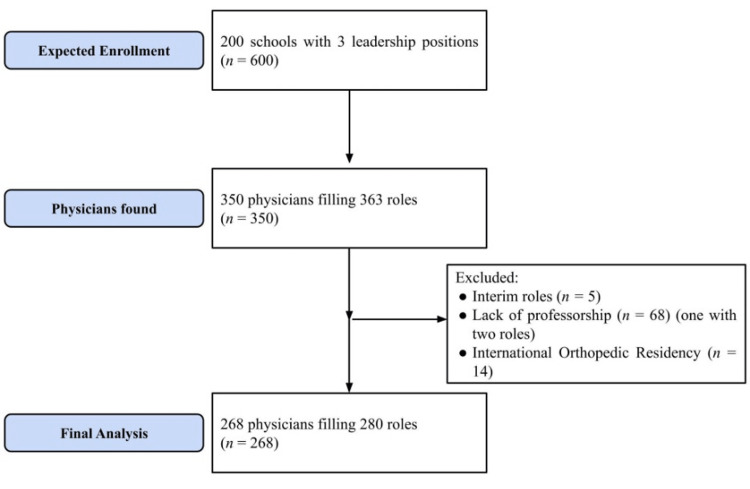

Given the 200 ACGME accredited programs and the three positions of leadership we planned to assess, we expected to gather data on 600 physicians. After searching each program's website, we found 350 physicians fulfilling 363 leadership roles. Thirteen physicians held multiple leadership roles in their program. To assess physicians with permanent roles, we excluded physicians with interim roles, which excluded five physicians. To assess physicians with academic titles, we only assessed physicians with professorships in orthopedics at their respective institutions. This excluded 68 physicians, one of which had multiple roles. Finally, we excluded 14 physicians with orthopedic training outside of the United States since those were not ranked in the Doximity rankings. This restriction narrowed the total to 268 physicians satisfying 280 roles (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Leadership inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were set to include physicians with permanent leadership positions with academic titles. Furthermore, to assess residency reputation ranking, only those with residency training inside the United States were included.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis included the assessment of averages and frequencies of demographic and research data. We used univariate data analysis comparing the reputation rankings of orthopedic residency training program rankings of chairs and PDs with two-sample t-tests. In addition, we used univariate data analysis comparing the reputation rankings of orthopedic residency training program rankings of the faculty in leadership positions versus the expected reputation ranking with two-sample t-tests. The expected reputation ranking was calculated by finding the weighted average of the residency ranking. The weighted average was determined first by finding the weighted value of each program, which was obtained by multiplying each residency ranking by the total number of residents at each program. Then, we took the sum of the weighted values and divided this number by the total of 4567 resident positions across the 200 U.S. residency programs to determine the weighted average. To assess for frequency of females in leadership positions, we used a Pearson’s chi-square test using the 2018 AAOS Census as expected data [5]. Finally, to compare fellowship trends in orthopedic academic chairs, vice-chairs, and program directors to orthopedics as a whole, we used the 2018 AAOS Census data for the percentage of each fellowship orthopedic surgeon pursued [5]. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to the number of unranked medical schools, statistical analysis was not performed on this data.

Results

Total leadership statistics

In total, we gathered data on 115 department chairs, 15 vice-chairs, 126 PDs, 11 with both titles of chair and PD, and one with the title of vice-chair and PD. In total, there were 244 males and 24 females (9.0% female). One hundred sixty were professors (59.7%), 62 were associate professors (23.1%), and 46 were assistant professors (17.2%). On average, the physicians completed 23 years of graduating from orthopedic residency. Two hundred twenty-two of the 268 physicians completed one American fellowship (82.8%), 14 had done two American fellowships (5.2%), and one physician did three American fellowships (0.4%). Therefore, 237 of the physicians had completed at least one American fellowship (88.4%) On average, each physician had 60.7 publications on PubMed. Twenty-two of the 268 physicians had master's degrees (8.2%), and four of the physicians had PhD degrees (1.5%), two of which had both a master’s degree and a PhD (0.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Data of Academic Orthopedic Leadership.

*12 physicians with multiple titles (11 with both department chair and PD, one with vice-chair and PD)

SD = Standard deviation, CI = 95% confidence interval, PhD = Doctorate in Philosophy, MD = Doctor of Medicine, DO = Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

| Department Chair | Vice-chair | Program Directors | Total | |

| Total Number | 126 | 16 | 138 | 268* |

| Males (%) | 121 (96.0) | 13 (81.3) | 122 (88.4) | 244 (91.0) |

| Females (%) | 5 (4.0) | 3 (18.7) | 16 (11.6) | 24 (9.0) |

| Years since Graduating Residency (years) (SD) | 28.4 (7.1) | 29.7 (12.0) | 18.4 (9.0) | 23.4 (9.9) |

| Additional Fellowship (%) | 113 (89.6) | 15 (93.8) | 120 (87.0) | 231 (86.2) |

| 1 Fellowship (%) | 103 (81.7) | 14 (87.5) | 116 (84.1) | 222 (82.1) |

| 2 Fellowship (%) | 9 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 4 (2.9) | 14 (5.2) |

| 3 Fellowship (%) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Number of publications (SD) | 91.8 (116.7) | 48.7 (31.3) | 35.7 (52.1) | 60.7 (88.4) |

| Higher-Level Training (%) | 15 (11.9) | 4 (25.0) | 6 (4.3) | 24 (9.0) |

| Masters (%) | 13 (10.3) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (3.6) | 20 (7.5) |

| PhD (%) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) |

| Masters and PhD (%) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) |

| MD Degree (%) | 124 (98.4) | 14 (87.5) | 134 (97.1) | 262 (97.8) |

| DO Degree (%) | 2 (1.6) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (2.9) | 6 (97.8) |

| Average Reputation Residency Ranking (CI) | 57.0 (8.3) | - | 63.6 (8.0) | 59.7 (5.7) |

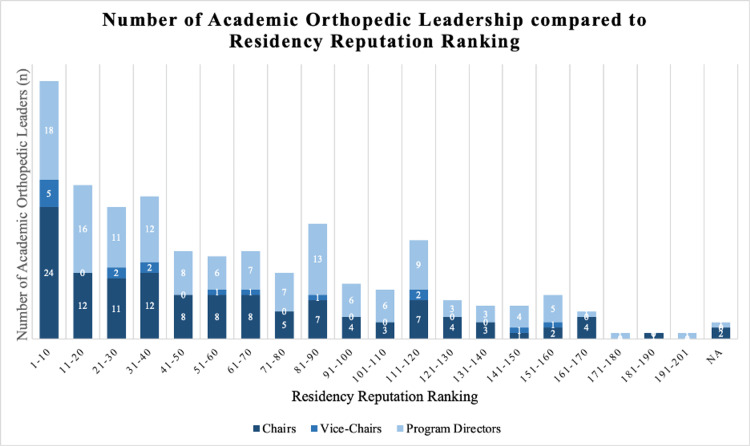

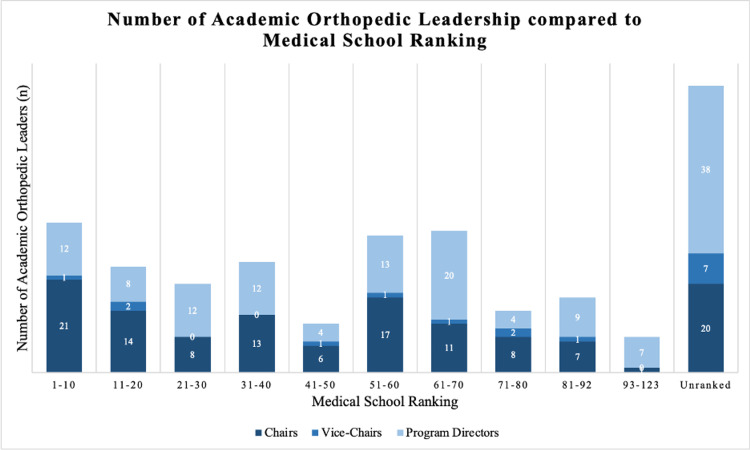

Given the number of spots at each program, the expected average reputation ranking was 83.6. The average residency reputation of all the physicians was 59.7 ± 5.7 according to Doximity’s rankings (p < 0.005). The most common residency programs were Hospital for Special Surgery/Cornell Medical Center, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, and NYU Grossman School of Medicine/NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital, each producing eight physicians with leadership positions. Thirty-two of the 126 department chairs are chairs in the same program as their residency training (36.6%). The distribution of the programs can be seen in Figure 2. Two hundred and sixty-two physicians are MDs while six are DOs (97.8% MD). The distribution of their medical school ranking according to U.S. News can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2. The number of Academic Orthopedic Leadership compared to Residency Reputation Ranking.

Reputation rankings were determined using Doximity. The programs under NA were former residency programs that have been closed (Letterman Army Medical Center and Fitzsimons Army Medical Center).

Figure 3. The number of Academic Orthopedic Leadership compared to Medical School Ranking Ranking.

Medical rankings were determined using the U.S. News research ranking.

Department chair statistics

A total of 126 department chairs were found, with 11 of them also having the title of PD. In total, there were 121 males and 5 females (4.0% female). One hundred eight were professors (85.7%), 11 were associate professors (8.7%), and seven were assistant professors (5.6%). On average, the physicians completed 28 years of graduating from orthopedic residency. One hundred three of the 126 physicians completed one American fellowship (81.7%), nine had completed two American fellowships (7.1%), and one physician completed three American fellowships (0.8%). Therefore, 116 of the physicians completed at least one American fellowship (92.0%). On average, each physician had 91.8 publications on PubMed. Fourteen of the 126 physicians had master's degrees (11.1%), and two had PhD degrees (1.6%), one of which had both a master’s degree and a PhD (0.8%).

Vice-chair statistics

A total of 16 vice-chairs were found, with one of them also having the title of PD. In total there were 13 males and three females (18.8% female). Thirteen were professors (81.3%), two were associate professors (12.5%), and one was an assistant professor (6.3%). On average, the physicians completed 30 years of graduating from orthopedic residency. Fourteen of the 16 physicians completed one American fellowship (87.5%), and one completed two American fellowships (6.3%). Therefore, 15 of the physicians completed at least one American fellowship (93.8%). On average the physicians had 48.7 publications on PubMed. Four of the 16 physicians had master's degrees (25.0%), one of which had both a master’s degree and a PhD (6.3%).

The average residency reputation of all the physicians was 56.6 according to Doximity’s rankings. The most common residency program was Wake Forest University School of Medicine. The distribution of the programs can be seen in Figure 2. Seven of the 16 are vice-chair in the same program as their residency training (43.8%). Fourteen of the physicians had their MD while two had a DO (87.5% MD). The distribution of their medical school ranking according to U.S. News can be seen in Figure 3.

Program director statistics

A total of 138 PDs were found, with 11 of them also having the title of the chair, and one also having the title of vice-chair. In total, there were 122 males and 16 females (11.6% female). Forty-six were professors (33.3%), 53 were associate professors (38.4%), and 39 were assistant professors (28.3%). On average, the physicians completed 18 years of graduating from orthopedic residency. One hundred sixteen of the 138 physicians completed one American fellowship (84.0%), and four completed two American fellowships (2.9%). Therefore, 120 of the physicians completed at least one American fellowship (87.0%). On average the physicians had 35.7 publications on PubMed. Five of the 138 PDs had master's degrees (3.6%), and one of the PDs had a PhD (0.7%). No PD had both a master's and a PhD.

Department chairs versus program director residency Doximity reputation ranking

The average residency reputation of all the chairs was 57.0 ± 8.3, according to Doximity’s rankings (p < 0.005). The most common residency programs to appear with five chairs each were the University of Rochester and NYU Grossman School of Medicine/NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital. The distribution of the programs can be seen in Figure 2. Thirty-two of the 126 department chairs are chairs in the same program as their residency training (25.4%). One hundred twenty-four of the physicians had their MD while two had a DO (98.4% MD). The distribution of their medical school ranking according to U.S. News can be seen in Figure 3.

The average residency reputation of all the PDs was 63.6 ± 8.0, according to Doximity’s rankings (p < 0.005). The most common residency programs to appear with four PDs each was Hospital for Special Surgery/Cornell Medical Center, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science (Rochester), and SUNY (The State University of New York) Downstate Health Sciences University. The distribution of the programs can be seen in Figure 2. Sixty-three of the 138 department chairs are chairs in the same program as their residency training (58.3%). One hundred thirty-four of the physicians had their MD while four had a DO (97.1% MD). The distribution of their medical school ranking according to U.S. News can be seen in Figure 3. We found no statistically significant difference in residency reputation rankings between department chairs and PDs (p = 0.26).

Gender distribution

We performed a Pearson’s chi-squared to assess the distribution of women in leadership. The data obtained from the 2018 AAOS Census was used as the expected value, which stated that women made up 5.8% of orthopedic attendings [5]. Twenty-four women held leadership positions, which was significantly different than the expected 15.5 women (p = 0.031). There was no significant difference in female chairs (p = 0.33), however, there was a significant difference in female PDs (p <0.005), with 16 females as PDs compared to the expected eight females.

When using data that states that females made up 17.8% of females at academic orthopedic institutions as the expected value, the results changed [6]. Twenty-four women overall had a position of leadership compared to the expected 47.7 women (p < 0.005). There were five female chairs compared to the expected 22.4 female chairs (p < 0.005), and 16 female PDs compared to the expected 24.6 female PDs (p = 0.056).

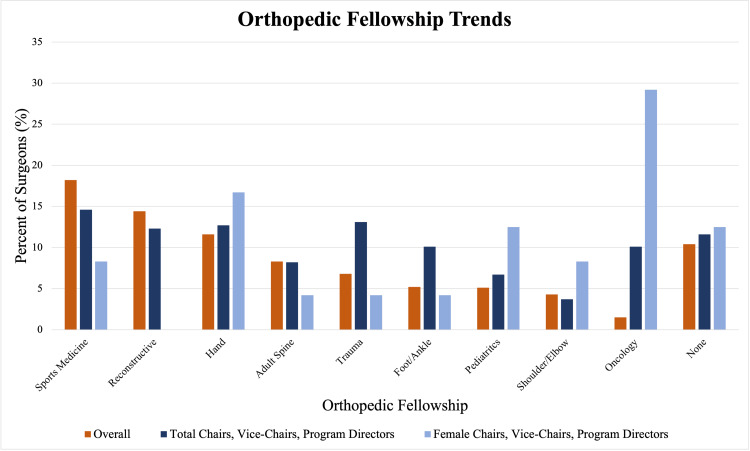

Fellowship data

We assessed the percentage of each fellowship represented in total and women orthopedic academic chairs, vice-chairs, and program directors. In total, while sports medicine was the most represented (14.6%), oncology and trauma were overrepresented at 10.1% and 13.1%, respectively, compared to the 2018 AAOS census data for all orthopedic surgeons (1.5% and 6.8%, respectively) [5] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Orthopedic Fellowship Trends.

The following graph looks at the distribution of orthopedic fellowships in all orthopedics, females in orthopedics, all orthopedic chairs, vice-chairs, and PDs at academic institutions, and female orthopedic chairs, vice-chairs, and PDs at academic institutions. The data for the overall numbers for orthopedics came from the 2018 AAOS census. The data on chairs, vice-chairs, and PDs came from our own data.

Discussion

Previous literature has assessed the characteristics and patterns of faculty with leadership positions at academic orthopedic institutions. Common characteristics include significant research history and geographical ties to the location. Furthermore, there has been an increasing trend of faculty with leadership positions who are fellowship trained in either orthopedic trauma or orthopedic oncology. Finally, there remains to be a lack of females in leadership [1,3,4]. Our study aimed to expand on this data and further identify whether the reputation of their orthopedic training program correlates with those in leadership positions.

In order to assess those with leadership positions in academics, we assessed only physicians with professorship (professor, associate professor, or assistant professor) at their own academic institutions who were the chair, vice-chair, or PD. This limitation excluded leaders at hospitals who may interact with residents but do not have an academic title.

We found that around half (136/268) of academic orthopedic leaders were trained at a top 50 residency programs according to Doximity reputation rankings, with an average residency program reputation ranking of 59.7. The average residency reputation ranking for department chairs was 57.0, and for PDs was 63.6. There was no significant difference between the reputation rankings for department chairs and PDs, but there was a significant difference in the reputation rankings seen in this study compared to the expected reputation ranking value of 83.6 in all leadership positions.

This data implies that orthopedic leadership often comes from programs with an increased reputation. This trend can be due to a variety of reasons. Often programs with a higher reputation also produce a significant amount of research, which has been shown to be associated with those found in leadership in orthopedics [4]. Also, academic institutions may want to pursue physicians with training at higher ranking residency programs to improve their own reputation further. While many factors go into deciding which programs to rank when matching into a residency program, program reputation may play a role in those hoping to pursue an academic leadership position eventually.

With a large portion of the orthopedic surgeons in academic leadership attending unranked medical schools according to the U.S. News ranking, it was difficult to assess the data quantitatively. However, based on the chart, around half (142/268) of physicians came from a top 60 medical school. There are 192 medical schools, which implies a trend for orthopedic academic leaders to attend higher-ranking medical schools [11]. However, we were unable to assess the significance of this trend. Future research should attempt to quantify this data to determine objective trends.

We found similar statistics in publications, years of experience, and fellowship distribution compared to previous studies [4]. Furthermore, we also found that the orthopedic oncology and orthopedic trauma fellowships were seen in a disproportionately high amount compared to the number of those that pursue these fellowships. We believe this may occur because orthopedic trauma and orthopedic oncology fellowships may result in these physicians remaining within a hospital system rather than in private practice. Chan et al. found that the top two orthopedic subspecialties with job listings, by percentage, in academic centers were orthopedic oncology and orthopedic trauma [13]. Furthermore, it may be easier for orthopedic oncologists and orthopedic trauma surgeons to pursue research and set themselves up for an academic orthopedic leadership position by remaining in a hospital system.

Furthermore, previous literature found that women remain underrepresented in academic orthopedic leadership positions [1,3,4]. Our data continues to support this. At the first glance, using the number of female orthopedic attendings provided by the AAOS, it seems like women are overrepresented in academic orthopedic leadership [5]. However, when using the number of full-time women orthopedic surgery faculty found in academic programs, we found that women continue to be underrepresented in leadership [6]. Correcting this trend may lead to more women pursuing orthopedics out of medical school. A number of studies have shown that women are more likely than men to indicate having a role model or mentor positively influences their pursuit of orthopedic surgery [6,7,14-18]. On the other hand in January 2020, Bi et al. found that 3/153 (2.0%) chairs and 18/161 (11.2%) of PDs were women in all residency programs, while our study found that 5/126 (4.0%) of chairs and 16/138 (11.6%) of PDs with an academic position were women as of March 2022 [4]. This represents a slight increase in women's representation, but it remains disproportionately low compared to the 17.8% of women with positions at academic institutions.

Finally, we assessed orthopedic fellowship trends amongst women. In 2020, Jurenovich et al. surveyed 252 women on their fellowship choices [19]. Women in this survey were more likely to pursue pediatric and hand fellowships and less likely to pursue a reconstructive fellowship compared to the 2018 AAOS census on total fellowship trends amongst all orthopedic surgeons. Similarly, we found that female orthopedic chairs, vice-chairs, and PDs at academic institutions were more likely to have completed a fellowship in pediatrics and hand, but less likely to pursue reconstruction. Women in academic leadership positions were also more likely to have a fellowship in oncology, which aligns with the fact that women tend to choose oncology more often, and oncology-trained orthopedic surgeons are more likely to be chairs, vice-chairs, and PDs (Figure 4). Therefore, even within orthopedics, women are disproportionately represented in each subspeciality compared to their peers. It has been reported that the biggest factor in females producing certain fellowships was pure enjoyment, while mentorship was not found to play a factor in fellowship choice, which contrasts with the importance of having a female model to choose a career in orthopedics [6,7,13-18]. Statistical analysis was not performed due to the limited number of females in academic leadership positions and the fellowship data coming from two different surveys. We recommend that future census collections assess fellowship choice amongst all genders.

Limitations of this study include the lack of standardization and accessibility of data surrounding orthopedic academic leadership, which has been discussed in numerous studies [4,20-22]. Standardization and easy access to this data would allow for a better understanding of trends related to orthopedics. However, cross-referencing Doximity with the academic websites allowed us to accurately assess the training programs of all the orthopedic academic leaders. Furthermore, due to the lack of public data surrounding vice-chairs, we could not analyze their training. Whether this data was unable to be found due to a lack of availability or whether programs have opted to have vice-chairs no longer should be assessed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights that the average leader in academic orthopedics trained in a residency program with a higher than average reputation. This trend suggests that these surgeons had more access to research, or could have been hired due to an attempt by programs to improve their own reputation. Finally, women continue to be underrepresented in orthopedic academic leadership, and correcting this could lead to more women pursuing orthopedics.

Appendices

Table 2 demonstrates the reputation ranking data obtained from Doxmity, along with the number of residents at each program and the percentage of residents at this program.

Table 2. Doximity’s Orthopedic Surgery Reputation Ranking with Number of Residents.

| Ranking | School | Number of Residents | Percentage of Residents |

| 1 | Hospital for Special Surgery/Cornell Medical Center | 45 | 1.0% |

| 2 | Washington University/B-JH/SLCH Consortium | 40 | 0.9% |

| 3 | Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science (Rochester) | 65 | 1.4% |

| 4 | NYU Grossman School of Medicine/NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital | 70 | 1.5% |

| 5 | Duke University Hospital | 40 | 0.9% |

| 6 | University of Washington | 40 | 0.9% |

| 7 | Massachusetts General Hospital/Brigham and Women's Hospital/Harvard Medical School | 60 | 1.3% |

| 8 | Rush University Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 9 | Vanderbilt University Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 10 | UPMC Medical Education | 40 | 0.9% |

| 11 | University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics | 30 | 0.7% |

| 12 | Emory University School of Medicine | 30 | 0.7% |

| 13 | University of Pennsylvania Health System | 40 | 0.9% |

| 14 | University of Utah Health | 40 | 0.9% |

| 15 | Carolinas Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 16 | University of California (San Francisco) | 35 | 0.8% |

| 17 | Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University/TJUH | 30 | 0.7% |

| 18 | Cleveland Clinic Foundation | 30 | 0.7% |

| 19 | University of Virginia Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 20 | Johns Hopkins University | 30 | 0.7% |

| 21 | New York Presbyterian Hospital (Columbia Campus) | 30 | 0.7% |

| 22 | Stanford Health Care-Sponsored Stanford University | 35 | 0.8% |

| 23 | University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston | 30 | 0.7% |

| 24 | University of Miami/Jackson Health System | 35 | 0.8% |

| 25 | University of Minnesota | 40 | 0.9% |

| 26 | University of Southern California/LAC+USC Medical Center | 40 | 0.9% |

| 27 | McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University | 45 | 1.0% |

| 28 | University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center | 30 | 0.7% |

| 29 | University of Michigan Health System | 40 | 0.9% |

| 30 | University of Rochester | 40 | 0.9% |

| 31 | University of California Davis Health | 25 | 0.5% |

| 32 | University of Tennessee/Campbell Clinic | 40 | 0.9% |

| 33 | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai | 35 | 0.8% |

| 34 | Prisma Health/University of South Carolina SOM Greenville (Greenville) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 35 | Brown University | 30 | 0.7% |

| 36 | Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | 30 | 0.7% |

| 37 | University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics | 30 | 0.7% |

| 38 | Wake Forest University School of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 39 | Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science (Arizona) | 10 | 0.2% |

| 40 | Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine | 15 | 0.3% |

| 41 | UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine/UCLA Medical Center | 30 | 0.7% |

| 42 | University of Maryland | 30 | 0.7% |

| 43 | University of South Florida Morsani | 20 | 0.4% |

| 44 | Loyola University Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 45 | University of Chicago | 25 | 0.5% |

| 46 | Allegheny Health Network Medical Education Consortium (AGH) | 25 | 0.5% |

| 47 | MedStar Health/Georgetown University Hospital | 20 | 0.4% |

| 48 | University of Colorado | 35 | 0.8% |

| 49 | Tufts Medical Center | 20 | 0.4% |

| 50 | University of Missouri-Columbia | 25 | 0.5% |

| 51 | Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine | 30 | 0.7% |

| 52 | University of California (San Diego) Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 53 | Ohio State University Hospital | 30 | 0.7% |

| 54 | University of Tennessee College of Medicine at Chattanooga | 15 | 0.3% |

| 55 | University of Alabama Medical Center | 30 | 0.7% |

| 56 | University of New Mexico School of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 57 | University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 58 | University of Florida | 20 | 0.4% |

| 59 | Texas A&M College of Medicine-Scott and White Medical Center (Temple) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 60 | Boston University Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 61 | University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio Joe and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine | 35 | 0.8% |

| 62 | Baylor College of Medicine | 30 | 0.7% |

| 63 | Prisma Health/University of South Carolina SOM Columbia (Columbia) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 64 | Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell at Huntington Hospital | 30 | 0.7% |

| 65 | Virginia Commonwealth University Health System | 25 | 0.5% |

| 66 | Summa Health System/NEOMED | 20 | 0.4% |

| 67 | Tulane University | 15 | 0.3% |

| 68 | University of Connecticut | 25 | 0.5% |

| 69 | University of Kansas School of Medicine | 20 | 0.4% |

| 70 | Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell | 20 | 0.4% |

| 71 | Indiana University School of Medicine | 30 | 0.7% |

| 72 | Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 73 | Rutgers Health/New Jersey Medical School | 30 | 0.7% |

| 74 | University at Buffalo | 25 | 0.5% |

| 75 | Yale-New Haven Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 76 | Medical University of South Carolina | 20 | 0.4% |

| 77 | Rutgers Health/Robert Wood Johnson Medical School | 20 | 0.4% |

| 78 | Oregon Health & Science University | 25 | 0.5% |

| 79 | Spectrum Health/Michigan State University | 25 | 0.5% |

| 80 | University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center | 30 | 0.7% |

| 81 | Beaumont Health (Royal Oak and Taylor) | 40 | 0.9% |

| 82 | MedStar Health/Union Memorial Hospital | 10 | 0.2% |

| 83 | University of North Carolina Hospitals | 25 | 0.5% |

| 84 | University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) College of Medicine | 30 | 0.7% |

| 85 | Mount Carmel Health System | 10 | 0.2% |

| 86 | George Washington University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 87 | Maimonides Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 88 | Orlando Health | 25 | 0.5% |

| 89 | Temple University Hospital | 20 | 0.4% |

| 90 | University of Kansas (Wichita) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 91 | Cedars-Sinai Medical Center | 20 | 0.4% |

| 92 | Akron General Medical Center/NEOMED | 15 | 0.3% |

| 93 | University of Louisville School of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 94 | University of Cincinnati Medical Center/College of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 95 | University of Mississippi Medical Center | 20 | 0.4% |

| 96 | UMass Chan Medical School | 25 | 0.5% |

| 97 | University of Kentucky College of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 98 | Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell at Lenox Hill Hospital | 10 | 0.2% |

| 99 | University of Vermont Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 100 | West Virginia University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 101 | Henry Ford Hospital | 30 | 0.7% |

| 102 | NYU Long Island School of Medicine | 15 | 0.3% |

| 103 | Louisiana State University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 104 | Naval Medical Center (San Diego) | 25 | 0.5% |

| 105 | National Capital Consortium | 30 | 0.7% |

| 106 | Los Angeles County-Harbor-UCLA Medical Center | 25 | 0.5% |

| 107 | McLaren Health Care/Flint/MSU | 15 | 0.3% |

| 108 | University of Michigan Health-West | 10 | 0.2% |

| 109 | University of Texas Medical Branch Hospitals | 25 | 0.5% |

| 110 | Dartmouth-Hitchcock/Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital | 20 | 0.4% |

| 111 | Naval Medical Center (Portsmouth) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 112 | UPMC Medical Education/Hamot | 15 | 0.3% |

| 113 | Geisinger Health System | 20 | 0.4% |

| 114 | Univ of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences | 15 | 0.3% |

| 115 | Medical College of Wisconsin Affiliated Hospitals | 25 | 0.5% |

| 116 | Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV | 20 | 0.4% |

| 117 | Tripler Army Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 118 | SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University | 30 | 0.7% |

| 119 | Albert Einstein Healthcare Network | 15 | 0.3% |

| 120 | University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson | 20 | 0.4% |

| 121 | Madigan Army Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 122 | San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium (SAUSHEC) | 30 | 0.7% |

| 123 | University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago | 25 | 0.5% |

| 124 | Baylor University Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 125 | St Joseph's University Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 126 | Cleveland Clinic Foundation/South Pointe Hospital | 15 | 0.3% |

| 127 | SUNY Upstate Medical University | 25 | 0.5% |

| 128 | University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville | 20 | 0.4% |

| 129 | William Beaumont Army Medical Center/Texas Tech University (El Paso) | 25 | 0.5% |

| 130 | University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix | 20 | 0.4% |

| 131 | University of California (Irvine) | 20 | 0.4% |

| 132 | Methodist Hospital (Houston) | 15 | 0.3% |

| 133 | Southern Illinois University | 15 | 0.3% |

| 134 | University of California (San Francisco)/Fresno | 20 | 0.4% |

| 135 | Detroit Medical Center/Wayne State University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 136 | St Louis University School of Medicine | 25 | 0.5% |

| 137 | OhioHealth/Doctors Hospital | 25 | 0.5% |

| 138 | Wright State University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 139 | John Peter Smith Hospital (Tarrant County Hospital District) | 30 | 0.7% |

| 140 | St Luke's University Hospital | 15 | 0.3% |

| 141 | University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School | 20 | 0.4% |

| 142 | Rutgers Health/Jersey City Medical Center | 15 | 0.3% |

| 143 | Howard University | 20 | 0.4% |

| 144 | Louisiana State University (Shreveport) | 15 | 0.3% |

| 145 | University of Toledo | 20 | 0.4% |

| 146 | Marshall University School of Medicine | 15 | 0.3% |

| 147 | Ochsner Clinic Foundation | 15 | 0.3% |

| 148 | USA Health | 15 | 0.3% |

| 149 | University of Puerto Rico* | 20 | 0.2% |

| 150 | University of Hawaii | 10 | 0.4% |

| 151 | Medical College of Georgia | 20 | 0.3% |

| 152 | Broward Health | 15 | 0.5% |

| 153 | Stony Brook Medicine/University Hospital | 25 | 0.3% |

| 154 | Westchester Medical Center | 15 | 0.4% |

| 155 | University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine | 20 | 0.4% |

| 156 | WellStar Atlanta Medical Center | 20 | 0.3% |

| 157 | Wellspan Health/York Hospital | 15 | 0.4% |

| 158 | Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Lubbock | 20 | 0.5% |

| 159 | Albany Medical Center | 25 | 0.3% |

| 160 | St Mary's Hospital and Medical Center | 15 | 0.2% |

| 161 | HCA Healthcare/USF Morsani College of Medicine GME: Largo Medical Center | 10 | 0.4% |

| 162 | Larkin Community Hospital | 20 | 0.3% |

| 163 | Nassau University Medical Center | 12 | 0.3% |

| 164 | Kettering Health Network | 15 | 0.4% |

| 165 | Community Memorial Health System | 20 | 0.4% |

| 166 | McLaren Health Care/Greater Lansing/MSU | 20 | 0.5% |

| 167 | Loma Linda University Health Education Consortium | 25 | 0.2% |

| 168 | Western Reserve Hospital | 10 | 0.2% |

| 169 | OPTI West/Valley Hospital Medical Center | 10 | 0.3% |

| 170 | Valley Consortium for Medical Education | 15 | 0.4% |

| 171 | Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine | 20 | 0.2% |

| 172 | Rutgers Health/Monmouth Medical Center | 10 | 0.2% |

| 173 | Cooper Medical School of Rowan University/Cooper University Hospital | 10 | 0.3% |

| 174 | Inspira Health Network/Inspira Medical Center Vineland | 15 | 0.4% |

| 175 | Kansas City University GME Consortium (KCU-GME Consortium)/HCA Healthcare Kansas City | 20 | 0.3% |

| 176 | University of Central Florida/HCA Healthcare GME (Ocala) | 15 | 0.5% |

| 177 | RowanSOM/Jefferson Health/Virtua Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital | 25 | 0.5% |

| 178 | UPMC Medical Education (Harrisburg) | 25 | 0.2% |

| 179 | One Brooklyn Health System/Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center | 10 | 0.3% |

| 180 | Ascension Genesys Hospital | 15 | 0.2% |

| 181 | Ascension Macomb-Oakland Hospital | 10 | 0.3% |

| 182 | Ascension Providence/MSUCHM | 15 | 0.4% |

| 183 | Beaumont Health (Farmington Hills and Dearborn) | 20 | 0.2% |

| 184 | Case Western Reserve University/University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center/Regional | 10 | 0.2% |

| 185 | Dwight David Eisenhower Army Medical Center | 10 | 0.2% |

| 186 | East Tennessee State University/Quillen College of Medicine | 10 | 0.4% |

| 187 | Franciscan Health Olympia Fields | 20 | 0.2% |

| 188 | Garden City Hospital | 10 | 0.4% |

| 189 | Geisinger Health System (Wilkes Barre) | 20 | 0.2% |

| 190 | Henry Ford Macomb Hospital | 10 | 0.3% |

| 191 | Jack Hughston Memorial Hospital | 15 | 0.3% |

| 192 | Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine | 15 | 0.3% |

| 193 | McLaren Health Care/Macomb/MSU | 15 | 0.3% |

| 194 | McLaren Health Care/Oakland/MSU | 15 | 0.3% |

| 195 | Mercy St Vincent Medical Center | 15 | 0.2% |

| 196 | Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences | 10 | 0.3% |

| 197 | Riverside University Health System | 15 | 0.3% |

| 198 | Robert Packer Hospital | 15 | 0.3% |

| 199 | Samaritan Health Services | 15 | 0.2% |

| 200 | Sinai Hospital of Baltimore | 10 | 0.3% |

| 201 | St Elizabeth Youngstown Hospital | 15 | 1.0% |

Table 3 demonstrates U.S. News rankings used to rank each medical school.

Table 3. U.S. News’ Research Rankings for Medical Schools*.

*Remaining schools were unranked.

| Ranking | School |

| 1 | Harvard University |

| 2 | New York University (Grossman) |

| 3 | Duke University |

| 4 | Columbia University |

| 4 | Stanford University |

| 4 | University of California - San Francisco |

| 7 | Johns Hopkins University |

| 7 | University of Washington |

| 9 | University of Pennsylvania (Perelman) |

| 10 | Yale University |

| 11 | Mayo Clinic School of Medicine (Alix) |

| 11 | Washington University in St. Louis |

| 13 | University of Pittsburgh |

| 13 | Vanderbilt University |

| 15 | Northwestern University (Feinberg) |

| 15 | University of Michigan - Ann Arbor |

| 17 | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai |

| 17 | University of Chicago (Pritzker) |

| 19 | Cornell University Weill |

| 19 | University of California - San Diego |

| 21 | University of California - Los Angeles |

| 22 | Baylor College of Medicine |

| 22 | Emory University |

| 24 | University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill |

| 25 | Case Western Reserve University |

| 26 | University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center |

| 27 | University of Colorado |

| 27 | University of Maryland |

| 29 | Oregon Health and Science University |

| 29 | University of Southern California (Keck) |

| 31 | University of Virginia |

| 32 | University of Alabama - Birmingham |

| 33 | Boston University |

| 33 | Ohio State University |

| 33 | University of Wisconsin - Madison |

| 36 | Brown University (Alpert) |

| 36 | University of Florida |

| 36 | University of Rochester |

| 39 | Albert Einstein College of Medicine |

| 39 | University of Iowa (Carver) |

| 41 | University of Utah |

| 42 | Indiana University - Indianapolis |

| 42 | University of Cincinnati |

| 42 | University of Minnesota |

| 45 | Dartmouth College (Geisel) |

| 45 | University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School |

| 45 | University of Miami (Miller) |

| 48 | University of California - Davis |

| 48 | University of California - Irvine |

| 48 | University of South Florida |

| 48 | Wake Forest University |

| 52 | University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio |

| 53 | University of Texas Health Science Center Houston (Mcgovern) |

| 54 | University of Nebraska Medical Center |

| 55 | Georgetown University |

| 55 | Stony Brook University - SUNY |

| 55 | Thomas Jefferson University (Kimmel) |

| 55 | Tufts University |

| 55 | University of Illinois |

| 60 | George Washington University |

| 61 | Temple University (Katz) |

| 61 | University of Connecticut |

| 61 | Virginia Commonwealth University |

| 64 | Rush University |

| 64 | University of Hawaii Manoa (burns) |

| 66 | Hofstra University/Northwell Health (Zucker) |

| 66 | Rutgers New Jersey Medical School - Newark |

| 66 | University of Vermont (Larner) |

| 66 | Wayne State University |

| 70 | Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick |

| 70 | Saint Louis University |

| 70 | University of Arizona - Tucson |

| 70 | University of Kentucky |

| 74 | University of Oklahoma |

| 75 | Augusta University |

| 75 | Texas A&M University |

| 75 | University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences |

| 75 | University of Kansas Medical Center |

| 75 | University of Louisville |

| 75 | University of Missouri |

| 81 | University at Buffalo SUNY (Jacobs) |

| 81 | University of New Mexico |

| 83 | University of Missouri - Kansas City |

| 83 | Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine |

| 83 | West Virginia University |

| 86 | Drexel University |

| 86 | University of Central Florida |

| 88 | Eastern Virginia Medical School |

| 88 | SUNY Upstate Medical University |

| 90 | New York Medical College |

| 90 | Tripler Army Medical Center |

| 90 | University of South Carolina |

| 93-123 | Copper Medical School of Rowan University |

| 93-123 | East Carolina University (Brody) |

| 93-123 | East Tennessee State University (Quilen) |

| 93-123 | Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine |

| 93-123 | Florida Atlantic University (Schmidt) |

| 93-123 | Florida International University (Wertheim) |

| 93-123 | Florida State University |

| 93-123 | Howard University |

| 93-123 | Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine |

| 93-123 | Lincoln Memorial University (Debusk) |

| 93-123 | Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center - Shreveport |

| 93-123 | Marshall University (Edwards) |

| 93-123 | Midwestern University (Arizona) |

| 93-123 | Midwestern University (Illinois) |

| 93-123 | Nova Southeastern University Patel College of Osteopathic Medicine (Patel) |

| 93-123 | Ohio University |

| 93-123 | Oklahoma State University |

| 93-123 | Quinnipiac University |

| 93-123 | Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine |

| 93-123 | Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center |

| 93-123 | Touro University California |

| 93-123 | University of California Riverside |

| 93-123 | University of New England |

| 93-123 | University of North Texas Health Sciences |

| 93-123 | University of Pikeville |

| 93-123 | University of Tennessee Health Science Center |

| 93-123 | University of Toledo |

| 93-123 | Western University of Health Sciences |

| 93-123 | West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine |

| 93-123 | William Carney University College of Osteopathic Medicine |

| 93-123 | Wright State University (Boonshoft) |

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.The academic chair: achieving success in a rapidly evolving health-care environment: AOA critical issues. Salazar DH, Herndon JH, Vail TP, Zuckerman JD, Gelberman RH. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leadership in academic medicine: capabilities and conditions for organizational success. Lobas JG. Am J Med. 2006;119:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Characteristics of highly successful orthopedic surgeons: a survey of orthopedic chairs and editors. Klein G, Hussain N, Sprague S, Mehlman CT, Dogbey G, Bhandari M. Can J Surg. 2013;56:192–198. doi: 10.1503/cjs.017511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The current state of orthopaedic educational leadership. Bi AS, Fisher ND, Singh SK, Strauss EJ, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2021;29:167–175. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AAOS Department of Clinical Quality and Value: Orthopaedic Practice in the U.S. 2018. [ May; 2022 ];https://www.aaos.org/ globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/census/2018-census.pdf 2019 8:2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Women in orthopaedic surgery: population trends in trainees and practicing surgeons. Chambers CC, Ihnow SB, Monroe EJ, Suleiman LI. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A 5-year update on the uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery residency training programs in the United States. Van Heest AE, Fishman F, Agel J. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:0. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The effect of medical school reputation and Alpha Omega Alpha membership on the orthopedic residency match in the United States. Campbell ST, Chin G, Gupta R, Avedian R. Med Sci Edu. 2017;27:503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Residency program reputation influences the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons match results. Krueger CA, Chisari E, Israel H, Cannada LK. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2676–2681. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Analysis of current orthopedic surgery residents and their prior medical education: does medical school ranking matter in orthopedic surgery match? Holderread BM, Liu J, Craft HK, Weiner BK, Harris JD, Liberman SR. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:1063–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Methodology: 2022 Best Medical Schools Rankings. U.S. News & World Report. [ May; 2022 ]. 2022. https:// www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate- schools/articles/medical-schools-methodology https:// www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate- schools/articles/medical-schools-methodology

- 12.Doximity Residency Navigator. [ May; 2022 ];https://www.doximity.com/residency/programs?spe- cialtyKey=bd234238-6960-4260-9475-1fa18f58f092- orthopaedic-surgery&sortByKey=reputation&trainin- gEnvironmentKey=all&intendedFellowshipKey= 2022 https://www.doximity.com/residency/programs?spe-:234238–236960. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Analysis of orthopaedic job availability in the United States based on subspecialty. Chan JY, Charlton TP, Thordarson DB. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4:0. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Residents' perceptions of sex diversity in orthopaedic surgery. Hill JF, Yule A, Zurakowski D, Day CS. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:0–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Factors influencing orthopedic surgery residents' choice of subspecialty fellowship. Kavolus JJ, Matson AP, Byrd WA, Brigman BE. Orthopedics. 2017;40:0–4. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170619-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The return on investment of orthopaedic fellowship training: a ten-year update. Mead M, Atkinson T, Srivastava A, Walter N. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:0–31. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mentoring during residency education: a unique challenge for the surgeon? Pellegrini VD Jr. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:143–148. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224026.85732.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Perry Initiative's Medical Student Outreach Program recruits women into orthopaedic residency. Lattanza LL, Meszaros-Dearolf L, O'Connor MI, Ladd A, Bucha A, Trauth-Nare A, Buckley JM. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1962–1966. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4908-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Women in orthopedics and their fellowship choice: what influenced their specialty choice? Jurenovich KM, Cannada LK. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32742203/ Iowa Orthop J. 2020;40:13–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Accessibility and availability of online information for orthopedic surgery residency programs. Davidson AR, Loftis CM, Throckmorton TW, Kelly DM. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4910793/ Iowa Orthop J. 2016;36:31–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Information on orthopedic trauma fellowships: online accessibility and content. Hinds RM, Capo JT, Egol KA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29099889/ Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2017;46:0–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.How useful are orthopedic surgery residency web pages? Oladeji LO, Yu JC, Oladeji AK, Ponce BA. J Surg Educ. 2015;72:1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]