As of August 5, 2022, there have been more than 7500 confirmed or suspected monkeypox (MPX) cases in the United States—mostly among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM).1 These numbers are certainly underestimates, given the lack of widespread testing. Although effective vaccines exist, they are in short supply, and to date, the federal government has prioritized MPX postexposure prophylaxis. The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have highlighted the significance of controlling the spread of MPX early on as the number of cases climbs rapidly2; however, this will take coordinated planning by public health officials, local health jurisdictions, and GBMSM communities as the federal government makes more vaccines available.

In the coming months, the federal government will deploy an estimated 1.6 million doses of the two-dose JYNNEOS vaccine to prevent MPX.3 Although scale-up of MPX vaccination is a key pillar of the Biden–Harris administration’s strategy to combat the MPX virus, the plan lacks guidance for local health jurisdictions about how to deploy vaccines to reach those most affected by MPX. The health inequities that GBMSM already face compared with their heterosexual counterparts demand focused attention on our communities without further stigmatizing GBMSM in the context of MPX. Fortunately, we can rely on scientific evidence from previous infectious disease outbreaks primarily affecting GBMSM, including HIV and invasive meningococcal disease, as well as lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.

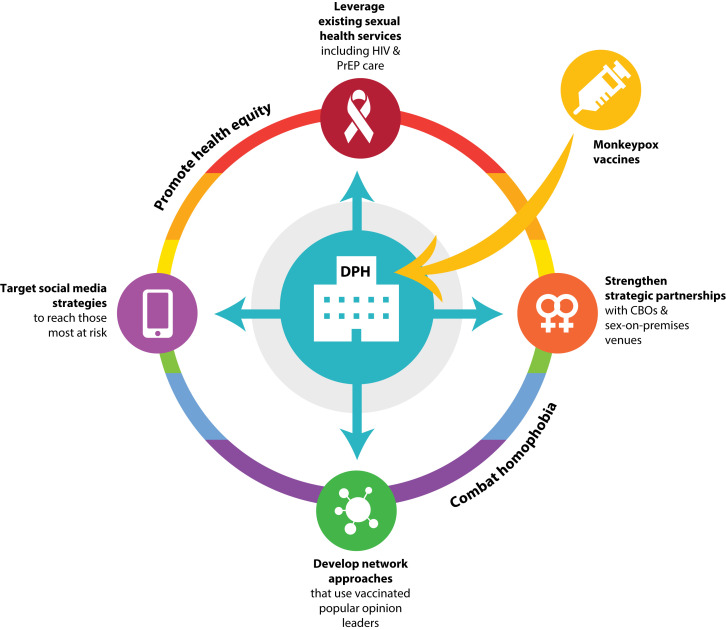

Although invasive meningococcal disease is more virulent and fatal than monkeypox, vaccine coverage among GBMSM is low: the 2018 study by Holloway et al. estimated that less than 40% of GBMSM had been vaccinated during an ongoing outbreak in Southern California.4 By contrast, a February 2022 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report noted that nearly 90% of GBMSM had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine,5 which may bode well for MPX vaccination campaigns. However, the long-complicated relationship between GBMSM and public health presents potential barriers: many GBMSM continue to face challenges trusting and accessing health care services. If efforts to control the spread of MPX in the United States are to be effective, public health must work collaboratively with GBMSM communities on vaccination implementation. Figure 1 outlines four key strategies for improving MPX vaccine coverage among GBMSM.

FIGURE 1—

Four Community-Based Strategies for Scale-Up of Monkeypox (MPX) Vaccination Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States

Note. CBO = community-based organization; DPH = department of public health; PrEP = preexposure prophylaxis.

A strengths-based perspective for achieving MPX vaccination among GBMSM, including GBMSM living with HIV, should use existing health care engagement. In the United States, an estimated 700 000 GBMSM are living with HIV,6 and hundreds of thousands more are current users of HIV preexposure prophylaxis, a prevention strategy that requires quarterly sexually transmitted infection testing. During the 2016 invasive meningococcal disease outbreak, Holloway et al. found that 12% of preexposure prophylaxis users had not been vaccinated for invasive meningococcal disease—a key missed opportunity for vaccination during preexposure prophylaxis provider visits.7 HIV service providers, sexual health clinics, and CDC-funded preexposure prophylaxis centers of excellence should be prioritized as MPX vaccination sites. This strategy would benefit those who are immunocompromised and those whose sexual behaviors may put them at elevated risk for contracting MPX.

As with COVID-19, local health jurisdictions have been the first to receive limited JYNNEOS vaccine. In preparation for widescale distribution, public health officials across the United States should forge and strengthen existing relationships with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) community–based organizations that serve GBMSM. These same organizations have been at the forefront of educating GBMSM about MPX while minimizing stigma about the disease. Many of these community-based organizations are federally qualified health centers or are affiliated with health care networks that have established trust with GBMSM over decades and are well poised to be MPX vaccine providers.

Beyond community-based organizations that serve the LGBTQ+ community, public health providers must establish robust partnerships with sex-on-premises venues that cater to GBMSM. Bathhouses, saunas, raves and other electronic music events, and popular sex parties are ideal places to hold vaccination clinics. Many sex-on-premises venues already offer HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevention services (e.g., informational resources, weekly sexually transmitted infection testing) and are keenly interested in health promotion. In the early days of HIV, some local health jurisdictions closed sex-on-premises venues, cutting off key opportunities for community education during an emerging health crisis. Now, approaching owners and organizers of sex-on-premises venues early and making the case for protecting staff and patrons from MPX in ways that respect the social context will be crucial. As we learned from COVID-19, these clinics need to be carefully managed to meet the requirements of vaccine storage and to schedule follow-up appointments for those receiving their first dose. Planning now will ensure that protocols and processes are ready for deployment when vaccine supplies arrive.

Although many GBMSM attend sex-on-premises venues, more seek sexual partners via geosocial networking applications and Web sites. The 2016 California Department of Public Health guidance for invasive meningococcal disease vaccination included GBMSM who sought partners through Web sites or telephone digital apps, as they are more likely to have multiple sex partners and to have been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection than GBMSM who do not use these technologies.4 Grindr, a popular dating app among GBMSM, has recently been used for MPX-specific education efforts, yet there are hundreds of niche apps and Web sites used by GBMSM who would not be reached by Grindr. Public health departments, therefore, must get comfortable with advertising vaccination opportunities on other niche gay sex partner–seeking platforms. Further collaboration with GBMSM networking apps to create profile fields that indicate whether users have been vaccinated for MPX, as was done with COVID-19, will simultaneously raise awareness of and set community norms for vaccination.

One of the most well-established HIV prevention interventions among GBMSM is the popular opinion leader model.8 Just as MPX is being spread via dense, interconnected social networks, vaccination information can be too. As public health departments and community-based organizations are vaccinating early adopters, likely those with the most confidence in vaccines, they should also be distributing and incentivizing referrals. GBMSM who are interested in becoming opinion leaders can be trained on how to talk to their friends and acquaintances about MPX. Public health departments and community-based organizations can begin holding workshops now for GBMSM who wish to serve their communities in this way.

Online popular opinion leader interventions have been used to increase discussions of sexual health and HIV testing among racial/ethnic minority GBMSM.9 This strategy may be especially helpful in promoting MPX vaccination uptake among racial/ethnic minority GBMSM, who have had lower levels of COVID-19 vaccination than their White counterparts.5 Although the federal government prioritizes vaccine allocation to jurisdictions with the highest MPX disease burden, local public health officials must pay careful attention to creating vaccination access points in diverse communities and offering vaccination clinics with weekend and evening hours. Finally, demographic data must be collected at vaccination, and those data should be rapidly synthesized and delivered back to local and federal public health officials to promote vaccine equity strategies.

One of the most widely shared videos on social media regarding MPX is that of an actor, Matt Ford, who contracted MPX and shared his story.10 Personal anecdotes are effective ways to shift public opinion. Many remember the positive impact that Magic Johnson and Pedro Zamora had on changing attitudes about HIV in the early 1990s. GBMSM community leaders, including drag and adult film performers, who have been vaccinated should be recruited (and compensated) to tell their stories. Personal accounts that highlight the importance of protecting oneself and protecting one’s community are powerful and can inspire widespread MPX vaccination in GBMSM communities. These efforts also combat stigma, one of the most intractable challenges in the fight against HIV.11 Unfortunately, we have seen a rise in online homophobia surrounding MPX as well as prominent figures, including celebrities and politicians, spreading the misinformation that MPX is a “gay disease.” Of course, MPX can affect anyone, and although it is currently concentrated in GBMSM communities, stigmatizing messages will only hamper ongoing public health efforts. In response, we must meet homophobic discourse with condemnation and focus our efforts on community education that inspires MPX vaccination, testing, and treatment.

Unlike the early days of the HIV epidemic, we currently have a presidential administration that acknowledges and values the lives of GBMSM. In late May, less than a month after the first cases of MPX were detected in the United States, the White House convened a meeting of LGBTQ+ community leaders to discuss strategies for combating the MPX virus. This is a stark contrast to the federal government’s inaction during the first years of the HIV epidemic. Although there is certainly more to be done to combat MPX, including substantial resource allocation to local health jurisdictions to implement vaccination, the efforts of GBMSM activists are not being ignored as they were in the early 1980s.

In addition, unlike the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have a US Food and Drug Administration–approved vaccine, which is currently being deployed and ordered in bulk. We also have a community ready to receive MPX vaccination and an established network of LGBTQ+ community–based organizations and opinion leaders ready to disseminate messaging to encourage vaccination. In the coming weeks and months, as JYNNEOS becomes more widely available, the strategies I have described can help establish widespread MPX vaccination coverage among GBMSM in the United States.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- 2.World Health Organization. Surveillance, case investigation and contact tracing for monkeypox: interim guidance. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Surveillance-2022.2

- 3.White House. 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/06/28/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administrations-monkeypox-outbreak-response

- 4.Holloway IW, Wu ESC, Gildner J, et al. Quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine uptake among men who have sex with men during a meningococcal outbreak in Los Angeles County, California, 2016–2017. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(5):559–569. doi: 10.1177/0033354918781085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and vaccine confidence by sexual orientation and gender identity—United States, August 29–October 30, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(5):171–176. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7105a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2021;26(1) https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-26-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holloway IW, Tan D, Bednarczyk RA, et al. Concomitant utilization of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and meningococcal vaccine (MenACWY) among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Los Angeles County, California. Arch Sex Behav. 2020;49(1):137–146. doi: 10.1007/s10508-019-01500-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/rep/packages/pol.html

- 9.Young SD, Holloway I, Jaganath D, Rice E, Westmoreland D, Coates T. Project HOPE: online social network changes in an HIV prevention randomized controlled trial for African American and Latino men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1707–1712. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen J. “You do not want this” virus: California man with monkeypox urges others to get vaccinated. CNNhttps://edition.cnn.com/2022/07/01/health/monkeypox-patient-tiktok/index.html2022

- 11.Frew PM, Holloway IW, Goldbeck C, et al. Development of a measure to assess vaccine confidence among men who have sex with men. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(11):1053–1061. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1541405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]