Abstract

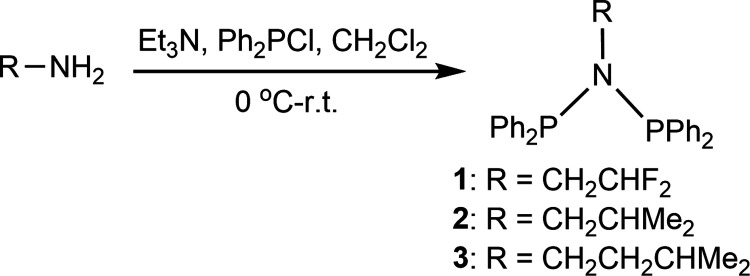

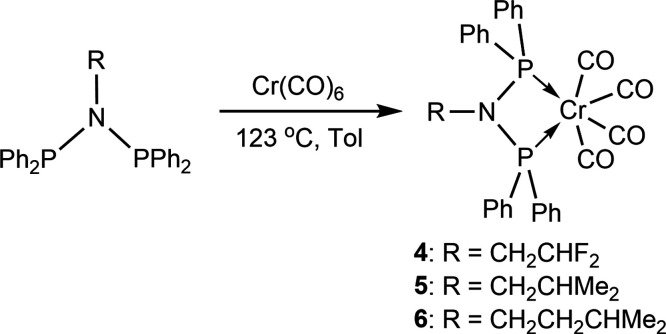

A range of novel N-substituted diphosphinoamine (PNP) ligands Ph2PN(R)PPh2 [R = F2CHCH2 (1); R = Me2CHCH2 (2); R = Me2CHCH2CH2 (3)] have been synthesized via one-step salt elimination reaction. The ligand-coordinated chromium carbonyls [Ph2PN(R)PPh2]Cr(CO)4 (4–6) were further synthesized, and X-ray crystallography analysis of complex 6 revealed the κ2-P,P bidentate binding mode of Cr center and the molecular structure of PNP ligand 3. Then the catalytic ethylene oligomerization behaviors of PNP ligands 1–3 bridging chromium chloride complexes {[Ph2PN(R)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 (7–9) were further discussed in depth. Experimental results showed that complex 7 with the strong electron-withdrawing F2CHCH2 group can promote the nonselective ethylene oligomerization, while both complex 8 and complex 9 with the electron-donating Me2CHCH2 and Me2CHCH2CH2 groups can significantly enhance the selective ethylene tri/tetramerization. The good catalytic activity of 198.3 kg/(g Cr·h), the selectivity toward 1-hexene and 1-octene of 76.4%, and the low PE content of 0.2% were simultaneously achieved with the Al/Cr molar ratio of 600 using the complex 8/MMAO system at 45 °C and 45 bar. These excellent results were mainly attributed to the fact that the β-branching of bridging ligand 2 increased the steric bulk of the N-moiety for complex 8.

1. Introduction

Linear alpha-olefins (LAOs) serve as the crucial organic raw material and chemical intermediates, which are usually used for the production of plasticizers, surfactants, lubricants, long-chain carboxylic acids, epoxides, and so forth.1−3 Among linear α-olefins, 1-hexene, 1-octene, and α-olefins with the higher carbon numbers are also the important comonomers for the preparation of the high-quality polyolefins.4−6 The traditional synthetic methods of linear α-olefins mainly include the alkane dehydrogenation, alkane catalytic cracking, fatty alcohol dehydrogenation, olefin dimerization and disproportionation, internal olefin isomerization, and so forth.7,8 In recent years, ethylene oligomerization has been rapidly developed for producing the linear α-olefins with higher purity than the traditional methods. There are primarily two types of ethylene oligomerization: nonselective oligomerization and selective tri/tetramerization.9,10 The traditional ethylene oligomerization is nonselective, which mostly produces a wide range of oligomers, and the separation of the corresponding components from the product mixtures requires intensive energy. The most representative nonselective oligomerization was based on the iron/nickel (Fe/Ni)-based catalyst systems, which mainly produced the multicomponent oligomers with the Schulz–Flory distribution.11−13 However, the selective ethylene tri/tetramerization can directly produce 1-hexene and 1-octene with high selectivity, which has attracted extensive research interest from both academia and industry. In particular, chromium-based catalysts have been widely studied due to their superior selectivity of 1-octene and 1-hexene in comparison with the other metal-based catalysts (Fe-, Co-, and Ni-based).14−17

The most common ligands used in chromium-based catalysts for ethylene tri/tetramerization are PNP and alternative diphosphines including PNNP, PCP, PCCP, PCNCP, or PN(C)nNP scaffolds.18−22 Since the ligands can stabilize the particular oxidation state and regulate the product selectivity, the ligand modification on the structure and electron will affect the catalytic selectivity.23,24 It has been proved that the catalytic performance of chromium-based complexes bearing tridentate PNP, PSP, and SPS ligands with S-substitution can be improved.25 Furthermore, the PNP ligands with tunable substituents on both N and P atoms are in favor of regulating the electron distribution and the steric bulk of the Cr center, which can produce the CrC6 or CrC6/CrC8 metallocycles that can promote the selectivity of 1-C6 and 1-C8.26,27 As reported, those Cr-based complexes bridging PNP ligands with the high steric bulks at backbone N (Chart 1A–D) have shown good catalytic activity and selectivity toward 1-octene and 1-hexene production.28 Nicoline Cloete’ and co-workers have also observed a similar tendency that a slight increase in 1-octene selectivity is found with increased bulkiness around the N atom.29 In addition, those PNP ligands with the electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups at backbone N can also affect the catalytic ethylene oligomerization behavior of Cr-based complexes. Artem A. Antonov and co-workers reported a family of cobalt(II) bis(imino)pyridine complexes bearing electron-withdrawing substituents (F, Cl, Br, CF3) at the aniline moieties, and the highest catalytic activities were obtained by cobalt complexes with electron-withdrawing o-substituents (Cl, CF3).30 However, the ligands with strong electron-withdrawing groups on the N-atom which can be used for chromium-catalyzed ethylene oligomerization have not been studied.

Chart 1. Typical Cr-based complexes supported by N-substituted PNP ligands.

Herein, we have synthesized a series of N-substituted PNP ligands Ph2PN(R)PPh2 with different electron-withdrawing or -donating and steric bulk groups [Chart 1, 1–3; R = CH2CHF2 (1); R = Me2CHCH2 (2); R = Me2CHCH2CH2 (3)]. To explore the binding environment of Cr center and the structures of PNP ligands 1–3, chromium carbonyl [PNP]Cr(CO)4 complexes (4–6) are further prepared based on the as-obtained ligands 1–3. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis indicates the κ2-P,P bidentate binding mode of [Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2CH2)PPh2]Cr(CO)4 complex (6). Furthermore, the chromium chloride {[Ph2PN(R)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 complexes (7–9) bearing PNP ligands 1–3 are also prepared to study the catalytic behaviors of ethylene oligomerization. Experimental results reveal that complex 7 can effectively promote the nonselective ethylene oligomerization, while both complexes 8 and 9 are beneficial for the selective ethylene tri/tetramerization. The probable explanation was that bridging ligand 1 in complex 7 occupies the strong electron-withdrawing CH2CHF2 group, while bridging ligands 2 and 3 in complexes 8 and 9 present the electron-donating groups. Then based on the preferable complex 8, the oligomerization temperature, reaction pressure, Al/Cr molar ratio, and cocatalysts (MAO and MMAO) were systematically optimized. As a result, the complex 8/MMAO system showed the good catalytic activity and tri/tetramerization selectivity, along with the extremely low 0.2% PE content.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Instrument

All handling of air- and humidity-sensitive compounds was conducted by using the Schlenk technique or in an argon-filled MBRAUN glovebox. Prior to use, organic solvents, such as toluene, n-hexane, ether, and tetrahydrofuran, were dried over the fine sodium wires and then refluxed with sodium/potassium benzophenone under nitrogen. All polymerization grade ethylene, high-purity nitrogen (99.999%), and high-purity argon (99.999%) were purchased from Jiangsu Hongren Special Gas Co., Ltd. (China), and no further purification was carried out. CH2Cl2 and CDCl3 were degassed and dried over CaH2. Both methylaluminoxane (MAO, 10% solution in toluene) and modified methylaluminoxane (MMAO, 7.1% aluminum solution in toluene) were purchased from Akzo-Nobel company. Anhydrous CrCl3 and Cr(CO)6 were purchased from J & K Chemical Technology Co. CrCl3(THF)3 was prepared by referring to the procedures in the literature.31

1H NMR, 13C{1H} NMR, 19F NMR, and 31P{1H} NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer (Figures S1–S20). Melting points of compounds were measured in a sealed glass tube of a Büchi-540 instrument. Elemental analysis was tested on a Thermo Quest Italia SPA EA 1110 instrument.

2.2. Synthesis of Chromium Complexes

2.2.1. Ph2PN(CH2CHF2)PPh2 Ligand (1)

Ph2PN(CH2CHF2)PPh2 ligand 1 was synthesized according to the procedures reported in the literature.32 At first, the distilled Ph2PCl (7.9 mL, 43.2 mmol) solution was mixed thoroughly with the CH2Cl2 (120 mL) and Et3N (22.5 mL, 162.0 mmol) solution. Then F2CHCH2NH2 (1.50 mL, 21.1 mmol) was added into the obtained mixture solution at 0 °C. After stirring continuously for 1 h, the ice bath was removed. Keeping stirring for another 15 h, the as-obtained mixture was further concentrated and the residue was pulpified with Et2O (∼200 mL) solution. The Et3N·HCl salt was filtered through a simple activated alumina column. Finally, the solvent was evaporated to obtain the white solid for the target ligand (6.80 g, 72%); Mp 97–98 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 3.65 (m, 2 H, CH2), 4.88 (td, J = 56.3 and 3.0 Hz, 1 H, CHF2), 7.32–7.39 (m, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 54.72 (m, CH2), 115.36 (d, J = 243.8 Hz, CHF2), 128.39 (d, J = 5.8 Hz), 129.32 (s), 132.84 (d, J = 21.7 Hz), 138.48 (dd, J = 17.5 and 3.8 Hz) (C6H5). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 67.36 (PPh2). 19F NMR (565 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = −120.99 (CHF2). Anal. Calcd for C26H23F2NP2, (Mr = 449.42): C, 69.49; H, 5.16; N, 3.12; Found, C, 69.23; H, 5.26; N, 3.05.

2.2.2. Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2)PPh2 Ligand (2)

The preparation of PNP ligand 2 was similar to that of PNP ligand 1, except that the F2CHCH2NH2 group was replaced by Me2CHCH2NH2 (2.10 mL, 21.1 mmol). The white solid of PNP ligand 2 was finally obtained (6.85 g, 74%). Mp: 113–114 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 0.56 (br, 6 H, CH3), 1.50 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1 H, Me2CH), 3.15 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH), 7.28–7.41 (m, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 20.38 (s, CH3), 29.41 (t, J = 3.2 Hz, Me2CH), 60.59 (s, NCH2CH), 127.99 (d, J = 5.9 Hz), 128.75 (s), 133.05 (d, J = 21.1 Hz), 139.74 (dd, J = 17.7, 3.9 Hz) (C6H5). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 62.72 (PPh2). Anal. Calcd for C28H29NP2, (Mr = 441.49): C, 76.17; H, 6.62; N, 3.17; found, C, 76.05; H, 6.53; N, 2.98.

2.2.3. Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2CH2)PPh2 Ligand (3)

Similarly, the preparation of PNP ligand 3 was consistent with that of PNP ligand 1, except that the F2CHCH2NH2 group was replaced by Me2CHCH2CH2NH2 (2.50 mL, 21.1 mmol). The white solid of PNP ligand 3 was finally obtained (7.36 g, 77%). Mp: 116–117 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 0.51 (br, 6 H, CH3), 0.91 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH2), 1.11 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1 H, Me2CH), 3.19 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH2), 7.22–7.32 (m, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 21.45 (s, CH3), 25.30 (s, Me2CH), 39.08 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, NCH2CH2), 50.53 (s, NCH2CH2), 126.97 (m), 127.62 (s), 131.70 (m), 138.58 (d, J = 12.5 Hz) (C6H5). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 62.12 (PPh2). Anal. Calcd for C29H31NP2 (Mr = 455.52): C, 76.47; H, 6.86; N, 3.07; found, C, 76.53; H, 6.75; N, 2.92.

2.2.4. [Ph2PN(CH2CHF2)PPh2]Cr(CO)4 Complex (4)

PNP ligand 1 (0.53 g, 1.18 mmol) and Cr(CO)6 (0.26 g, 1.20 mmol) were dissolved into toluene (50 mL), and then the mixture was heated to 123 °C for 24 h, obtaining a yellow solution. After cooling to room temperature, all volatiles were removed under the decompression conditions. The residue was collected and washed with n-hexane (5 mL) to obtain the yellow solid of complex 4 (0.52 g, 72%). Mp: 227 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 3.23 (m, 2 H, CH2), 5.45 (t, J = 55.1 Hz, 1 H, CHF2), 7.50 (br, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 51.48 (t, J = 27.8 Hz, CH2), 113.61 (t, J = 244.3 Hz, CHF2), 128.59 (t, J = 4.9 Hz), 130.89 (s), 131.86 (t, J = 6.7 Hz), 135.48–136.30 (m) (C6H5), 222.56 (t, J = 12.7 Hz), 227.73 (t, J = 8.9 Hz) (CO). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 120.99 (PPh2). 19F NMR (565 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = −118.46 (CHF2). IR (nujol mull, KBr plate, cm–1): ν = 1859, 1876, 1924, and 2005 (C≡O). Anal. calcd for C30H23CrF2NO4P2 (Mr = 613.46): C, 58.74; H, 3.78; N, 2.28; found, C, 58.63; H, 3.55; N, 2.19.

2.2.5. [Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2)PPh2]Cr(CO)4 Complex (5)

The preparation of complex 5 was similar to that of complex 4, except that PNP ligand 1 was replaced by PNP ligand 2 (0.52 g, 1.18 mmol). The yellow solid of complex 5 was finally obtained (0.54 g, 76%). Mp: 242 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 0.40 (br, 6 H, CH3), 1.53 (br, 1 H, Me2CH), 2.76 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH), 7.45–7.52 (m, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 19.95 (s, CH3), 27.19 (s, Me2CH), 58.54 (s, NCH2CH2), 128.33 (t, J = 4.8 Hz), 130.60 (s), 132.14 (t, J = 6.4 Hz), 137.04 (t, J = 18.9 Hz) (C6H5), 223.23 (t, J = 12.6 Hz), 228.32 (t, J = 9.3 Hz) (CO). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 116.24 (PPh2). IR (nujol mull, KBr plate, cm–1): ν = 1872, 1874, and 1998 (C≡O). Anal. calcd for C32H29CrNO4P2 (Mr = 605.53): C, 63.47; H, 4.83; N, 2.31; found, C, 63.38; H, 4.75; N, 2.24.

2.2.6. [Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2CH2)PPh2]Cr(CO)4 Complex (6)

The preparation of complex 6 was similar to that of complex 4, except that PNP ligand 1 was replaced by PNP ligand 3 (0.54 g, 1.18 mmol). The yellow solid of complex 6 was finally obtained (0.57 g, 78%). Mp: 224 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 0.59 (br, 6 H, CH3), 1.06 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH2), 1.14 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H, Me2CH), 2.97 (br, 2 H, NCH2CH2), 7.45–7.53 (m, 20 H, C6H5). 13C{1H} NMR (151 MHz, C6D6, 298 K, ppm): δ = 21.80 (s, CH3), 26.20 (s, Me2CH), 39.09 (s, NCH2CH2), 48.98 (s, NCH2CH2), 128.42 (t, J = 4.8 Hz), 130.59 (s), 132.25–131.60 (m), 136.94 (t, J = 18.9 Hz) (C6H5), 222.85 (t, J = 12.7 Hz), 228.38 (t, J = 9.3 Hz) (CO). 31P{1H} NMR (243 MHz, CDCl3, 298 K, ppm): δ = 113.90 (PPh2). IR (nujol mull, KBr plate, cm–1): ν = 1863, 1878, 1892, and 2003 (C≡O). Anal. calcd for C33H31CrNO4P2 (Mr = 619.56): C, 63.98; H, 5.04; N, 2.26; found, C, 64.12; H, 5.24; N, 2.18.

2.2.7. {[Ph2PN(CH2CHF2)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 Complex (7)

The PNP ligand 1 (0.53 g, 1.18 mmol) and CrCl3(THF)3 (0.41 g, 1.10 mmol) were dissolved into toluene (50 mL), and then the mixture was heated to 80 °C for 12 h, obtaining a blue suspension. After cooling to room temperature, toluene was filtered from the suspension. The residue was collected and washed with n-hexane (5 mL), further obtaining the blue solid of complex 7 (0.51 g, 76%). Mp: 171 °C. Anal. calcd for C52H46Cr2Cl6F4N2P4 (Mr = 1215.54): C, 51.38; H, 3.81; N, 2.30; found, C, 51.54; H, 3.67; N, 2.16.

2.2.8. {[Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 Complex (8)

The preparation of complex 8 was similar to that of complex 7, except that PNP ligand 1 was replaced by PNP ligand 2 (0.52 g, 1.18 mmol). The blue-violet solid of complex 8 was finally obtained (0.51 g, 72%). Mp: 187 °C. Anal. calcd for C56H58Cr2Cl6N2P4 (Mr = 1199.68): C, 56.07; H, 4.87; N, 2.34, found, C, 56.15; H, 4.96; N, 2.23.

2.2.9. {[Ph2PN(Me2CHCH2CH2)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 Complex (9)

The preparation of complex 9 was similar to that of complex 7, except that PNP ligand 1 was replaced by PNP ligand 3 (0.54 g, 1.18 mmol). The blue solid of complex 9 was finally obtained (0.57 g, 75%). Mp: 245 °C. Anal. calcd for C58H62Cr2Cl6N2P4 (Mr = 1227.74): C, 56.74; H, 5.09; N, 2.28; found, C, 56.56; H, 4.92; N, 2.18.

2.3. X-Ray Crystallographic Analysis

The crystal samples were assembled on the glass fiber through the oil drop method. The graphite-monochromatic Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) was used for measurements. Crystallographic data were collected on a Bruker D8 QUEST system. The spherical harmonics program (multi-scan type) was used for the absorption corrections. The direct method (SHELXS 97) or intrinsic phasing method (ShelXT) was used for structural analysis.33 All nonhydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined through the least square method on F2. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) are listed in Table S1.

2.4. Ethylene Oligomerization Reaction

Ethylene oligomerization reaction was performed in a 1.0 L stainless-steel autoclave equipped with a mechanical stirrer, a temperature controller, and an internal cooling system. Typically, the reactor was heated to 100 °C under vacuum and kept for 5 h to fully remove the air and moisture and then cooled to room temperature prior to use. After washing three times with nitrogen gas, the catalyst solution (in 20 mL of solvent), cocatalyst, and solvent were successively injected into the autoclave. The reactor was pressurized with ethylene and then heated to the desired temperature. Ethylene was continuously supplied to maintain a stable pressure environment. After ethylene oligomerization reaction, the ethylene feed gas was stopped and the reactor was quickly cooled to ca. 10 °C through a H2O/glycol low-temperature cycling system. Then the gas mixture was collected into the gasbags, and the liquid mixture was quenched with the 10% HCl/H2O solution. The liquid products were analyzed using a GC-FID instrument using a Shimadzu GC-2014C with an Inc19091Z-236 HP-1 capillary column (60 m × 0.25 mm). The corresponding linear relations for the calculations of 1-C6, methylcyclopentane, methylenecyclopentane, 1-C8, 1-C10, 1-C12, 1-C14, 1-C16, and 1-C18 are shown in Figures S21–S29. The GC-FID instrument worked at 35 °C for 10 min, then was heated to 85 °C at 5 °C/min, and then was heated to 280 °C at 10 °C/min and remained for another 10 min. The solid product was dried overnight in an oven at 50 °C to a constant weight. The GC-FID spectra of the oligomerization products obtained from entry 1 of Table 2 and entry 7 of Table 3 are displayed in Figures S30, S31. The corresponding residence times of the chromatographic peak to the products obtained from entry 1 of Table 2 and entry 7 of Table 3 are shown in Tables S2, S3.

Table 2. Catalytic Response Toward Ethylene Oligomerization with the Chromium Chloride Complexesa.

| Oligomer

distribution (wt %)b |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry (Cat.) | activity kg/(g Cr·h) | 1-C4 | C6(1-C6) | C8(1-C8) | C10 | C12 | C14 | C16 | C18 | PEc (wt %) |

| 1 (CrCl3(THF)3) | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 2 (7) | 75.6 | 11.9 | 24.5(100) | 31.8(100) | 12.6 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 9.5 |

| 3 (8) | 62.3 | 0 | 22.7(43.6) | 65.8(100) | 3.0 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| 4 (9) | 54.5 | 0 | 24.7(45.8) | 58.6(100) | 4.6 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 |

General conditions: 1.0 L reactor, 10.0 μmol of chromium-based precatalyst, 800 equiv of MAO, 180 mL toluene, 50 °C, 30 bar, run time: 30 min.

Weight percentage of the liquid fraction.

Weight percentage of the total product.

Table 3. Catalytic Response toward Ethylene Oligomerization with Complex 8a.

| Oligomer

distribution (wt %)b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry (Cat.) | P (bar) | T (°C) | cocat. (Al/Cr) | activity kg/(g Cr·h) | C6(1-C6) | C8(1-C8) | C10+ | PEc (wt %) |

| 1 (8) | 40 | 40 | MAO (800) | 134.6 | 18.2(32.4) | 69.8(100) | 12.0 | 1.0 |

| 2 (8) | 40 | 45 | MAO (800) | 201.9 | 20.2(38.1) | 69.1(100) | 10.7 | 0.9 |

| 3 (8) | 40 | 50 | MAO (800) | 153.8 | 22.6(42.8) | 67.2(100) | 10.2 | 1.4 |

| 4 (8) | 40 | 55 | MAO (800) | 75.0 | 23.5(46.2) | 65.6(100) | 10.9 | 2.6 |

| 5 (8) | 30 | 45 | MAO (800) | 73.1 | 21.3(39.0) | 67.3(100) | 11.4 | 0.9 |

| 6 (8) | 35 | 45 | MAO (800) | 105.8 | 20.7(38.5) | 68.1(100) | 11.2 | 1.0 |

| 7 (8) | 45 | 45 | MAO (800) | 207.7 | 17.1(36.2) | 70.2(100) | 12.7 | 0.8 |

| 8 (8) | 45 | 45 | MAO (1000) | 182.5 | 19.2(36.8) | 68.2(100) | 12.6 | 1.0 |

| 9 (8) | 45 | 45 | MAO (900) | 190.6 | 18.8(36.5) | 69.5(100) | 11.7 | 1.1 |

| 10 (8) | 45 | 45 | MAO (700) | 165.3 | 18.7(36.2) | 70.5(100) | 10.8 | 2.8 |

| 11 (8)d | 45 | 45 | MAO (600) | 105.6 | 16.9(35.5) | 70.8(100) | 12.3 | 6.7 |

| 12 (8) | 45 | 45 | MMAO (600) | 198.3 | 19.6(36.2) | 69.3(100) | 11.1 | 0.2 |

| 13 (8) | 45 | 45 | MMAO (500) | 195.5 | 18.9(36.8) | 68.9(100) | 12.2 | 0.3 |

| 14 (8) | 45 | 45 | MMAO (400) | 143.2 | 19.2(35.9) | 69.2(100) | 11.6 | 0.3 |

| 15 (8)d | 45 | 45 | MMAO (300) | 98.5 | 18.7(36.5) | 69.8(100) | 11.5 | 0.4 |

General conditions: 1.0 L reactor, 10.0 μmol of chromium-based precatalyst, 180 mL of toluene, run time: 30 min.

Weight percentage of the liquid fraction.

Weight percentage of the total product.

Run time: 20 min.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

The PNP ligands Ph2PN(R)PPh2 [R = F2CHCH2 (1); R = Me2CHCH2 (2); R = Me2CHCH2CH2 (3)] were synthesized with a high yield of 72–77% via one-step salt elimination reaction (Scheme 1). The R group in the Ph2PN(R)PPh2 scaffold can be easily tuned by using different primary amines as precursors.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the N-Substituted PNP Ligands 1–3.

At first, ligands 1–3 were characterized by NMR (31P, 1H, 13C, and 19F) spectra and CHN elemental analysis (Figures S1–S10). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of ligand 1 in CDCl3 (Figure S3) presented the characteristic single peak at 67.36 ppm, which has been verified to the P-atom of the PNP ligands.34,35 The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum (Figures S7, S10) also showed the characteristic single peak at 62.72 ppm for ligand 2 and at 62.12 ppm for ligand 3. The characteristic chemical shift value of ligand 1 was slightly positively shifted in comparison with that of ligands 2 and 3, which was probably ascribed to the strong electron-withdrawing behaviors of the CH2CHF2 group in ligand 1.36 In addition, the 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra (Figures S1, S2, S4–S6, S8, S9) of ligands 1–3 also further confirmed the formation of the expected PNP ligands.

Since the chromium carbonyl complexes can crystallize easily, the ligands and Cr(CO)6 were combined to characterize the bonding mode and the structure of PNP ligands. Chromium carbonyl complexes 4–6 were prepared via bonding Cr(CO)6 with ligands 1–3 in toluene at reflux, as shown in Scheme 2. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction results revealed the κ2-P,P bidentate binding mode of PNP ligands 1–3 at the Cr(VI) center. In Figures S13, S17, and S20, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of complexes 4–6 showed the characteristic single peak at 120.99 ppm for complex 4, at 116.24 ppm for complex 5, and at 113.90 ppm for complex 6. The chemical shift values of complexes 4–6 showed the positive shift in comparison with that of ligands 1–3, which was mainly attributed to the P,P binding mode of complexes 4–6. Besides, the variation tendency of the characteristic chemical shift value for complexes 4–6 was highly consistent with ligands 1–3. The single crystal of complex 6 was grown through the slow diffusion of n-hexane into the toluene solution at room temperature to define the coordination mode of the prepared PNP ligand. The high-quality single crystal of complex 6 has been obtained for X-ray diffraction analysis, which revealed the monomeric PNP-Cr(CO)4 complex with the distorted octahedral geometry at the center of Cr(VI) (Figure 1). The coordination sphere consisted of one PNP ligand and four carbonyl (CO) molecules. In Table 1, the chelating ring Cr(1)–P(2)–N(1)–P(3) is almost coplanar, and the corresponding dihedral angle defined is 4.81°. The P(2)–Cr(1)–P(3) bite angle of 68.24(2)° in complex 6 is close to the P–Cr–P angle of 70.58(2)° in chromium-based complexes bearing the PCP ligand, which is consistent with the previous reported work.37 Similarly, the Cr–P bond distances in the range of 2.3385–2.3398 Å for complex 6 are also similar to those found in the cyclopentyl–PNP–Cr complexes (2.3364–2.3622 Å).38 To sum up, the X-ray molecular structure of complex 6 further revealed the distorted octahedral geometries with bidentate P,P coordination of the PNP ligands.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the P, P-Chelation Cr(VI) Complexes.

Figure 1.

X-ray molecular structure of complex 6 with thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability level. H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Table 1. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for Complex 6.

| complex 6 | selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) |

|---|---|

| Cr(1)–P(2) | 2.3398(7) |

| Cr(1)–P(3) | 2.3385(8) |

| P(2)–N(1) | 1.697(3) |

| P(3)–N(1) | 1.700(2) |

| P(2)–Cr(1)–P(3) | 68.24(2) |

| P(2)–N(1)–P(3) | 101.17(12) |

| N(1)–P(2)–Cr(1) | 95.21(8) |

| N(1)–P(3)–Cr(1) | 95.17(9) |

Subsequently, the chromium chloride complexes were also prepared based on ligands 1–3 for the catalytic ethylene oligomerization. CrCl3(THF)3 reacted with ligands 1–3 in toluene solvent; then the solvent was removed and washed with n-hexane. The preparation process is displayed in Scheme 3, and the blue or blue-violet solids of complexes 7–9 were obtained. No suitable single crystal of chromium chloride complexes 7–9 was obtained for X-ray analysis, resulting in an undefined crystal structure. Elemental analysis of chromium chloride complexes 7–9 revealed the unoccupied sixth coordination site of chromium by THF, which is consistent with other known chromium-based complexes.35

Scheme 3. Synthesis of the P,P-Chelation Chromium(III) Chloride Complexes.

3.2. Effect of the Ligand Structure on Catalytic Performance

The dependence of production contents and ratios of ethylene oligomers on the nature of the N-substituents in the PNP ligands was systematically investigated. First, ethylene oligomerization properties were evaluated in toluene with 800 equiv of MAO as an activator. The CrCl3(THF)3/MAO system showed the sole catalysis for ethylene polymerization, regardless of the ethylene oligomerization. No obvious ethylene oligomerization response was detected with the CrCl3(THF)3/MAO system, further indicating that the catalytic center was mainly determined on the coordination environment of Cr center with the PNP ligand, instead of the sole chromium(III). From the data summarized in Table 2 (entries 2–4), chromium chloride complex 7 presented a higher catalytic activity [75.6 kg/(g Cr·h)] than complexes 8 [62.3 kg/(g Cr·h)] and 9 [54.5 kg/(g Cr·h)]. However, the selectivity toward 1-C6 and 1-C8 of complex 7 was lower than that of complexes 8 and 9. The probable reason was that the strong electron-withdrawing group of CH2CHF2 in complex 7 can promote the nonselective catalytic ethylene oligomerization. Although the electron-donating behaviors of complexes 8 and 9 were almost identical, the catalytic activity and ethylene tri/tetramerization selectivity of complex 8 [62.3 kg/(g Cr·h), 88.5%] were clearly superior to those of complex 9 [54.5 kg/(g Cr·h), 83.3%]. It can be observed that the bridging N-substituted moiety in complex 8 contained β-branching (relative to the bridging nitrogen atom), which effectively increased the steric bulk of the N-moiety. Similar results have been observed for the ligand 2-ethylhexyl-PNP (β-branching) and decyl-PNP, which reported the selectivity of 74.3 and 70.8% toward 1-C6 and 1-C8 production, respectively.28 Furthermore, the large amounts of 1-butene production (11.9%) of complex 7 implied the absence of extended metalacyclic mechanisms. Complex 8 afforded the 65.8% selectivity toward C8 and the 22.7% selectivity toward C6. In the C6 production of complex 8, the purity of 1-hexene was 43.6%, and the rest C6 fraction (56.4%) was composed of methylcyclopentane and methylenecyclopentane with the ratio of 1:1.26 Complex 9 afforded the 58.6% selectivity toward C8 and the 24.7% selectivity toward C6 (45.8% 1-C6). These results demonstrated that the catalytic activity and the production selectivity were mainly dependent on the electron-donating property and the steric bulk in ligands 1–3, which was in line with the literature results.39,40 To summarize, the experimental results also revealed that complex 7 can promote the nonselective ethylene oligomerization, while both complex 8 and complex 9 are more beneficial for the selective ethylene tri/tetramerization. Since complex 8 presented the highest C8 selectivity and the lowest PE content, it was selected to further explore the effect of reaction conditions on the catalytic selective ethylene tri/tetramerization.

3.3. Effect of Reaction Conditions on the Catalytic Behaviors

The effects of reaction conditions, including the oligomerization temperature, reaction pressure, and Al/Cr molar ratio, on the catalytic selective ethylene tri/tetramerization were studied with the complex 8/MAO system to achieve the optimal catalytic response. First, the different oligomerization temperatures (40, 45, 50, and 55 °C) were evaluated, as shown in Figure 2a. The catalytic activity of the complex 8/MAO system showed a volcano shape with increasing reaction temperatures from 40 to 55 °C, and the highest catalytic activity of 201.9 kg/(g Cr·h) was obtained at 45 °C. The temperature above 45 °C can gradually result in catalyst deactivation, which exhibited the lowest catalytic activity of 75.0 kg/(g Cr·h) at 55 °C. On the other hand, the gradually deactivated catalytic activity above 45 °C was also attributed to the decreasing ethylene solubility in toluene. Furthermore, with the increase of temperature, the C6 selectivity kept constantly increasing from 18.2% to 23.5% and the 1-C6 selectivity in C6 increased from 32.4% to 46.2%, while the 1-C8 selectivity was gradually decreased from 69.8% to 65.6% (Table 3, entries 1–4). This is largely in line with observations of Blann et al., which demonstrated that the reaction temperature plays a dominant role in determining the selectivity toward 1-C6 and 1-C8 production for PCNP/Cr tetramerization catalyst systems.22 The main reason was the poor stability of the generated metallacycloheptane intermediate at the high temperature. The probable catalytic reaction mechanism speculated that the β-hydride transfer and reductive elimination of metallacycloheptane were more beneficial than further insertion of ethylene.17,41 Besides, the PE content (0.9%) was the lowest at 45 °C.

Figure 2.

Effects of temperatures (a,b) pressures on 1-C6, 1-C8, and C10+ olefin catalytic activity and selectivity with the complex 8/MAO system in toluene. General conditions: 1.0 L reactor, 10.0 μmol of chromium-based precatalyst, 180 mL of toluene, run time: 30 min.

Second, the effects of ethylene pressures (30, 35, 40, and 45 bar) on the catalytic activity and the product selectivity with the complex 8/MAO system at 45 °C were further studied. As shown in Figure 2b, the catalytic activity was remarkably increased from 73.1 to 207.7 kg/(g Cr·h) with the increase of ethylene pressures from 30 to 45 bar (Table 3, entries 2 and 5–7), which was mainly attributed to the improved solubility of ethylene in the toluene solvent. With the increase of ethylene pressures, the C6 selectivity kept decreasing from 21.3% to 17.1% and the 1-C6 selectivity in C6 slightly decreased from 39.0% to 36.2%, while the 1-C8 selectivity was gradually increased from 67.3% to 70.2% (Table 3, entries 2 and 5–7). At 45 bar, the C8 selectivity was up to 70.2%, and the PE content was as low as 0.8%. These results indicated that the high pressure was in favor of the ethylene insertion into metallacycloheptane (CrC6), further producing metallacyclononane (CrC8).42

Third, different Al/Cr molar ratios (600, 700, 800, 900, and 1000) were further investigated with the complex 8/MAO system at 45 °C and 45 bar, as displayed in Figure 3a. The catalytic activity presented a volcano shape with the increase of Al/Cr molar ratios. The highest catalytic activity of 207.7 kg/(g Cr·h) was achieved when the molar ratio of Al/Cr was 800. At the Al/Cr molar ratio range of 600–800, the catalytic activity was significantly enhanced from 105.6 to 207.7 kg/(g Cr·h) (Table 3, entries 7 and 10–11), which indicated that MAO cocatalyst can affect the activity of selective catalytic ethylene tri/tetramerization. Moreover, enough MAO was required for the whole activation of chromium chloride complexes and the stabilization of active species. However, at the Al/Cr molar ratio range of 800–1000, the catalytic activity and C8 selectivity were slightly decreased (Table 3, entries 7–9), which was mainly ascribed to the interference of over-reduced chromium species by excess MAO.43 It is well known that MAO cocatalyst is highly expensive and produces the extra ash content.44 The modified MAO (MMAO) cocatalyst was developed for achieving the high catalytic performance toward selective ethylene tri/tetramerization. In Table 3, the complex 8/MMAO system cannot obviously change the oligomer distribution, indicating that both the complex 8/MAO and complex 8/MMAO systems produced identical active species toward the selective ethylene tri/tetramerization. As shown in Figure 3b, the catalytic activity with the complex 8/MMAO system was significantly improved in comparison with that of complex 8/MAO at the Al/Cr molar ratio of 600. MMAO cocatalyst was a more efficient activator than MAO for ethylene tri/tetramerization with chromium-based complexes bearing N-substituted diphosphinoamine ligands.36,45 With the decrease of Al/Cr molar ratio at the range of 300–500, the catalytic activities toward ethylene tri/tetramerization with the complex 8/MMAO system were remarkably decreased from 195.5 to 98.5 kg/(g Cr·h) (Table 3, entries 13–15). The catalytic activity platform appeared at the Al/Cr molar ratio range of 500–600 (Table 3, entries 12–13). Moreover, at the same molar ratio of Al/Cr (Table 3, entries 11 and 12), the PE content with the complex 8/MMAO system was sharply decreased in comparison with the complex 8/MAO system. The optimal catalytic activity of 198.3 kg/(g Cr·h) and the 1-C6 and 1-C8 selectivity of 76.4% were achieved with the Al/Cr molar ratio of 600 using the complex 8/MMAO system at 45 °C and 45 bar. Besides, the extremely low PE (0.2%) content was also obtained.

Figure 3.

Effects of Al/Cr molar ratios (a) with the complex 8/MAO system and (b) with the complex 8/MMAO system on 1-C6, 1-C8, and C10+ olefin catalytic activity and selectivity. General conditions: 1.0 L reactor, 10.0 μmol of precatalyst, 180 mL of toluene, run time: 30 min.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have designed and synthesized a series of chromium chloride {[Ph2PN(R)PPh2]CrCl2(μ-Cl)}2 complexes (7–9) bearing the N-substituted PNP ligands Ph2PN(R)PPh2 [R = F2CHCH2 (1); R = Me2CHCH2 (2); R = Me2CHCH2CH2 (3)] with the different electron-withdrawing or -donating and steric bulk properties for enhancing the selective catalytic ethylene tri/tetramerization. Since the formations of crystals of chromium chloride complexes (7–9) were knotty, the κ2-P,P bidentate binding mode of Cr center and the molecular structure of the PNP ligands were revealed on ligands 3 bridging chromium carbonyl complex 6. Furthermore, the catalytic behaviors showed that complex 7 with the strong electron-withdrawing F2CHCH2 group can promote the nonselective ethylene oligomerization, while both complexes 8 and 9 with the electron-donating Me2CHCH2 and Me2CHCH2CH2 groups can enhance the selective catalytic ethylene tri/tetramerization. In particular, complex 8 exhibited a higher catalytic activity and product selectivity than complex 9, which was mainly attributed to the fact that the β-branching of bridging ligand 2 increased the steric bulk of the N-moiety. Based on the optimized temperature, reaction pressure, Al/Cr molar ratio, and cocatalysts (MAO and MMAO), the first-rank catalytic activity of 198.3 kg/(g Cr·h), the 1-hexene and 1-octene selectivity of 76.4%, and the low PE content of 0.2% were simultaneously achieved with the Al/Cr molar ratio of 600 using the complex 8/MMAO system at 45 °C and 45 bar. This work can provide a new insight into the design of catalysts with an excellent overall performance toward selective ethylene tri/tetramerization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (no. 2017YFE0106700).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c04733.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agapie T. Selective ethylene oligomerization: Recent advances in chromium catalysis and mechanistic investigations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 861–880. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sydora O. L. Selective Ethylene Oligomerization. Organometallics 2019, 38, 997–1010. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Neal L.; Ding D.; Wu W.; Baroi C.; Gaffney A. M.; Li F. Recent Advances in Intensified Ethylene Production—A Review. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 8592–8621. 10.1021/acscatal.9b02922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen P. W. N. M.; Clément N. D.; Tschan M. J.-L. New processes for the selective production of 1-octene. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1499–1517. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Liu W.; Wang W.-J.; Li B.-G.; Zhu S. A Comprehensive Review on Controlled Synthesis of Long-Chain Branched Polyolefins: Part 1, Single Catalyst Systems. Macromol. React. Eng. 2016, 10, 156–179. 10.1002/mren.201500053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. H.; Lee H. M.; Jeong M. S.; Ryu J. Y.; Lee J.; Lee B. Y. Methylaluminoxane-Free Chromium Catalytic System for Ethylene Tetramerization. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 765–773. 10.1021/acsomega.6b00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monai M.; Gambino M.; Wannakao S.; Weckhuysen B. M. Propane to olefins tandem catalysis: a selective route towards light olefins production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 11503–11529. 10.1039/d1cs00357g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub’ F. S.; Bolotov V. A.; Parmon V. N. Modern Trends in the Processing of Linear Alpha Olefins into Technologically Important Products: Part I. Catal. Ind. 2021, 13, 168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer A.; Dietel T.; Kretschmer W. P.; Kempe R. A broadly tunable synthesis of linear α-olefins. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1226. 10.1038/s41467-017-01507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J. W.; Ko J. H.; Park J. H.; Park J. Y.; Lee H. J.; Seo Y. H.; Lee J.; Lee B. Y. α-Olefin Trimerization for Lubricant Base Oils with Modified Chevron–Phillips Ethylene Trimerization Catalysts. Organometallics 2022, 41, 2455–2465. 10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small B. L.; Brookhart M. Iron-Based Catalysts with Exceptionally High Activities and Selectivities for Oligomerization of Ethylene to Linear α-Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 7143–7144. 10.1021/ja981317q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier-Bourbigou H.; Breuil P. A. R.; Magna L.; Michel T.; Espada Pastor M. F.; Delcroix D. Nickel Catalyzed Olefin Oligomerization and Dimerization. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7919–7983. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngcobo M.; Nose H.; Jayamani A.; Ojwach S. O. Structural and ethylene oligomerization studies of chelating (imino)phenol Fe(ii), Co(ii) and Ni(ii) complexes: an experimental and theoretical approach. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 6219–6229. 10.1039/d1nj06065a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Zhong X.; Liu Z.; Liang S.; Zhu H. Selective Ethylene Oligomerization Catalyzed by the Chromium Complex Bearing N-Tetrahydrofurfuryl PNP Ligand. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 37, 2315. 10.6023/cjoc201703010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R.; Xiao L.; Hao X.; Sun W. H.; Wang F. Synthesis of benzoxazolylpyridine nickel complexes and their efficient dimerization of ethylene to α-butene. Dalton Trans. 2008, 41, 5645–5651. 10.1039/b807604a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan A.; Dastidar R. G.; Wang C.; Dumesic J. A.; Huber G. W. Effect of catalyst support on cobalt catalysts for ethylene oligomerization into linear olefins. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 3639–3649. 10.1039/d2cy00531j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Lin W.; Liu T.; Ye Z.; Liang T.; Sun W. H. Fluorinated Sterically Bulky Mononuclear and Binuclear 2-Iminopyridylnickel Halides for Ethylene Polymerization: Effects of Ligand Frameworks and Remote Substituents. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 30157–30172. 10.1021/acsomega.1c05418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh Y.; Albahily K.; Sutcliffe M.; Fomitcheva V.; Gambarotta S.; Korobkov I.; Duchateau R. A highly selective ethylene tetramerization catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1366–1369. 10.1002/anie.201106517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Song L.; Wu H.; Ji X.; Jiao J.; Zhang J. Ethylene tri-/tetramerization catalysts supported by diphosphinothiophene ligands. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 8399–8404. 10.1039/c7dt01060e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelter S. D.; Davies D. R.; Milbrandt K. A.; Wilson D. R.; Wiltzius M.; Rosen M. S.; Klosin J. Evaluation of Bis(phosphine) Ligands for Ethylene Oligomerization: Discovery of Alkyl Phosphines as Effective Ligands for Ethylene Tri- and Tetramerization. Organometallics 2020, 39, 967–975. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheredilin D. N.; Sheloumov A. M.; Senin A. A.; Kozlova G. A.; Afanas’ev V. V.; Bespalova N. B. Catalytic Properties of Chromium Complexes Based on 1,2-Bis(diphenylphosphino)benzene in the Ethylene Oligomerization Reaction. Pet. Chem. 2020, 59, S72–S87. 10.1134/s0965544119130036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blann K.; Bollmann A.; Brown G. M.; Dixon J. T.; Elsegood M. R. J.; Raw C. R.; Smith M. B.; Tenza K.; Willemse J. A.; Zweni P. Ethylene oligomerisation chromium catalysts with unsymmetrical PCNP ligands. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 4345–4354. 10.1039/d1dt00287b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T.; Lindeperg F.; Stradiotto M.; Turculet L.; Sydora O. L. Chromium N-phosphinoamidine ethylene tri-/tetramerization catalysts: Designing a step change in 1-octene selectivity. J. Catal. 2021, 394, 444–450. 10.1016/j.jcat.2020.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z.; Bi H.; Ding B.; Wang H.; Xu G.; Dai S. A rigid-flexible double-layer steric strategy for ethylene (co)oligomerization with pyridine-imine Ni(ii) and Pd(ii) complexes. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 8669–8678. 10.1039/d2nj00183g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D. S.; Wasserscheid P.; Morgan D. H.; Dixon J. T. Ethylene trimerization with mixed-donor ligand (N,P,S) chromium complexes: Effect of ligand structure on activity and selectivity. Organometallics 2005, 24, 552–556. 10.1021/om049168+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overett M. J.; Blann K.; Bollmann A.; Dixon J. T.; Haasbroek D.; Killian E.; Maumela H.; McGuinness D. S.; Morgan D. H. Mechanistic investigations of the ethylene tetramerisation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 10723–10730. 10.1021/ja052327b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agapie T.; Labinger J. A.; Bercaw J. E. Mechanistic studies of olefin and alkyne trimerization with chromium catalysts: deuterium labeling and studies of regiochemistry using a model chromacyclopentane complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14281–14295. 10.1021/ja073493h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blann K.; Bollmann A.; Debod H.; Dixon J.; Killian E.; Nongodlwana P.; Maumela M.; Maumela H.; Mcconnell A.; Morgan D. Ethylene tetramerisation: Subtle effects exhibited by N-substituted diphosphinoamine ligands. J. Catal. 2007, 249, 244–249. 10.1016/j.jcat.2007.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cloete N.; Visser H. G.; Engelbrecht I.; Overett M. J.; Gabrielli W. F.; Roodt A. Ethylene tri- and tetramerization: a steric parameter selectivity switch from X-ray crystallography and computational analysis. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 2268–2270. 10.1021/ic302578a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonov A. A.; Semikolenova N. V.; Talsi E. P.; Bryliakov K. P. Catalytic ethylene oligomerization on cobalt(II) bis(imino)pyridine complexes bearing electron-withdrawing groups. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 884, 55–58. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2019.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mastalir M.; Glatz M.; Stöger B.; Weil M.; Pittenauer E.; Allmaier G.; Kirchner K. Synthesis, characterization and reactivity of vanadium, chromium, and manganese PNP pincer complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 455, 707–714. 10.1016/j.ica.2016.02.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishna M. S.; Reddy V. S.; Krishnamurthy S. S.; Nixon J. F.; Burckett St.Laurent J. C. T. R. Coordination chemistry of diphosphinoamine and cyclodiphosphazane ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994, 129, 1–90. 10.1016/0010-8545(94)85018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/s2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Z. F.; Scopelliti R.; Dyson P. J. Influence of the functional group on the synthesis of aminophosphines, diphosphinoamines and iminobiphosphines. Dalton Trans. 2003, 2772–2779. 10.1039/b303645f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann A.; Blann K.; Dixon J. T.; Hess F. M.; Killian E.; Maumela H.; McGuinness D. S.; Morgan D. H.; Neveling A.; Otto S.; Overett M.; Slawin A. M.; Wasserscheid P.; Kuhlmann S. Ethylene tetramerization: a new route to produce 1-octene in exceptionally high selectivities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14712–14713. 10.1021/ja045602n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaseer E. A.; Garcia N.; Barman S.; Khawaji M.; Xu W.; Alasiri H.; Peedikakkal A. M. P.; Akhtar M. N.; Theravalappil R. Highly Efficient Ethylene Tetramerization Using Cr Catalysts Constructed with Trifluoromethyl-Substituted N-Aryl PNP Ligands. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16333–16340. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulai A.; de Bod H.; Hanton M. J.; Smith D. M.; Downing S.; Mansell S. M.; Wass D. F. C-Substituted Bis(diphenylphosphino)methane-Type Ligands for Chromium-Catalyzed Selective Ethylene Oligomerization Reactions. Organometallics 2009, 28, 4613–4616. 10.1021/om900285e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam F.; Fan H.; Dong C.; Zhang J.; Ma J.; Chen Y.; Jiang T. Chromium catalysts stabilized by alkylphosphanyl PNP ligands for selective ethylene tri-/tetramerization. J. Catal. 2021, 404, 163–173. 10.1016/j.jcat.2021.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang X.; Zhang X.; Wu W.; Zhang G.; Xu S.; Shi M. Switchable Ethylene Tri-/Tetramerization with High Activity: Subtle Effect Presented by Backbone-Substituent of Carbon-Bridged Diphosphine Ligands. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2311–2317. 10.1021/cs400651h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makume B. F.; Holzapfel C. W.; Maumela M. C.; Willemse J. A.; Berg J. A. Ethylene Tetramerisation: A Structure-Selectivity Correlation. Chempluschem 2020, 85, 2308–2315. 10.1002/cplu.202000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Liu Z.; Cheng R.; He X.; Liu B. Unraveling the Effects of H2, N Substituents and Secondary Ligands on Cr/PNP-Catalyzed Ethylene Selective Oligomerization. Organometallics 2018, 37, 3893–3900. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh R.; Morgan D. H.; Bollmann A.; Dixon J. T. Reaction kinetics of an ethylene tetramerisation catalyst. Appl. Catal., A 2006, 306, 184–191. 10.1016/j.apcata.2006.03.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T.; Ning Y.; Zhang B.; Li J.; Wang G.; Yi J.; Huang Q. Preparation of 1-octene by the selective tetramerization of ethylene. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006, 259, 161–165. 10.1016/j.molcata.2006.06.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J.; Zhang X.; Liu S.; Li Z. Chromium complexes supported by NNO-tridentate ligands: an unprecedented activity with the requirement of a small amount of MAO. Polym. Chem 2022, 13, 1852–1860. 10.1039/d2py00125j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T.; Liu X.; Ning Y.; Chen H.; Luo M.; Wang L.; Huang Z. Performance of various aluminoxane activators in ethylene tetramerization based on PNP/Cr(III) catalyst system. Catal. Commun. 2007, 8, 1145–1148. 10.1016/j.catcom.2006.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.