Abstract

Hyperhidrosis is a dermatological condition that causes psychosocial impairment and has a negative impact on patients’ quality of life. The epidemiology of hyperhidrosis is currently poorly understood. The aim of this study was to analyse comorbidities and treatments in 511 subjects with hyperhidrosis selected from the patient records of Oulu University Hospital. The mean age of patients with local hyperhidrosis was 27.9 years and the majority were female (62.7%). The most common anatomical site of symptoms in the youngest age group was the palms, whereas the axillae were a more common site in advanced age. Depression was a common comorbidity in both local (11.6%) and generalized hyperhidrosis (28.6%). Anxiety affected 12.7% of patients with generalized hyperhidrosis. In 36.8% of the patients with local hyperhidrosis there was a delay in diagnosis of more than 10 years. The most commonly used treatments included topical antiperspirants, iontophoresis and botulin toxin injections.

Key words: hyperhidrosis, iontophoresis, botulin toxin injections, comorbidity, depression, anxiety

Hyperhidrosis (HH) is a condition in which the body produces more sweat than is necessary for normal physiological thermoregulation (1). HH can be divided into primary and secondary HH, of which primary hyperhidrosis (PHH) is the most common form, comprising up to 93% of all patients with HH (2, 3). HH is less frequently caused by other medical conditions or medications. The estimated prevalence of HH is 2.8% in the USA, whereas, in Germany, the prevalence is estimated to be as high as 16.3% (4, 5).

PHH usually starts in childhood or early adulthood and, in most patients, it has a familial or genetic background (6). The diagnosis of HH is clinical and based on the patient’s symptoms (2). HH has a wide range of effects on patients’ quality of life, causing, for example, limitations in work, social relationships and leisure activities, but also causing impairment in mental health (7, 8). There are many treatment options available for HH, which can be classified into non-surgical (topical and systemic medications, iontophoresis and botulinum toxin injections (BTIs)) and surgical treatments (9).

SIGNIFICANCE

Hyperhidrosis is a condition defined as excessive sweating, which can be local or generalized. Hyperhidrosis has a negative effect on patients’ quality of life. This study investigated hyperhidrosis comorbidities and treatments, by using the patient records of Oulu University Hospital. One of the most common comorbidities associated with hyperhidrosis was depression. In more than one-third of patients with local hyperhidrosis, there was a long delay (over 10 years) before they received a diagnosis. Most of the patients experienced iontophoresis and botulin toxin injections as effective treatments for symptoms.

Even though HH is reported to be one of the most burdensome skin conditions, reducing patients’ quality of life (10), it has not been studied comprehensively. The aim of this study was to determine HH comorbidities and treatments in patients in Northern Finland.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patient records with International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision (ICD-10) codes for HH (R61.0 Local HH, R61.1 Generalized HH, R61.9 Unspecified HH) were extracted from the Oulu University Hospital medical records database. Study data were collected, checked and managed by the authors using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Oulu (11, 12). All patients who visited the dermatology outpatient clinic with the above-mentioned diagnoses between 1996 and 2019 were included in this study. The medical director of Oulu University Hospital approved the study. Ethics committee approval was not required, since the study was retrospective and based on medical records.

Statistical analysis

The overall prevalences of HH comorbidities and treatments were calculated. Data are presented as means, standard deviation (SD) and range, and as proportions for categorical variables. A χ2 test and analyses of variance were used to test differences between local and generalized HH and between age groups. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.1. R Core Team (2020) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/). A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients with hyperhidrosis

The current study included a total of 511 cases of HH (Table I). The most common diagnosis was local HH (80.1%). A minority (6.8%) of patients had been diagnosed with unspecified HH and had symptoms such as night sweating. Local and unspecified HH were seen more often in females (62.7% and 62.9%, respectively) compared with males (37.3% and 37.1%, respectively), but the sex distribution was even for patients with generalized HH (p = 0.1). Patients with local HH were notably younger (mean age 27.9 years) than those with generalized (43.6 years) or unspecified HH (47.4 years) (p < 0.01). A long duration of symptoms prior to receiving a diagnosis (>10 years) was seen more often in patients with local HH (36.8%) compared with those with generalized HH (20.0%) (p < 0.01). The most common anatomical sites for symptoms in local HH were the palms, soles of the feet and axillae (Table I). The distribution of anatomical sites of symptoms by age is shown in Table II. Nearly half of the patients (48.9%) with local HH had symptoms at only one anatomical site. Smoking was more common in patients with generalized (20.0%) and unspecified HH (28.6%) than in local HH (11.6%) (p < 0.01).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics

| LHH | GHH | UHH | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients, n | 413 | 63 | 35 | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 27.9 (11.8) | 43.6 (19.0) | 47.4 (20.3) | |

| Age group, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| 0–18 years | 78 (18.9) | 3 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | |

| 18–25 years | 119 (28.8) | 10 (15.9) | 5 (14.3) | |

| 25–40 years | 143 (34.6) | 16 (25.4) | 9 (25.7) | |

| 40–90 years | 73 (17.7) | 34 (54.0) | 20 (57.1) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.120 | |||

| Male | 154 (37.3) | 32 (50.8) | 13 (37.1) | |

| Female | 259 (62.7) | 31 (49.2) | 22 (62.9) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Smoker | 48 (11.6) | 13 (20.6) | 10 (28.6) | |

| Non-smoker | 78 (18.9) | 18 (28.6) | 12 (34.3) | |

| Ex–smoker | 10 (2.4) | 8 (12.7) | 2 (5.7) | |

| No informationa | 277 (67.1) | 24 (38.1) | 11 (34.1) | |

| Positive family history, n (%) | 0.138 | |||

| Yes | 53 (12.8) | 8 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No | 13 (3.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No informationa | 347 (84.0) | 54 (82.7) | 35 (100.0) | |

| Duration of symptoms, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| <1 years | 23 (6.3) | 16 (26.7) | 14 (40.0) | |

| 1–2 years | 38 (10.4) | 12 (20.0) | 8 (22.9) | |

| 2–5 years | 110 (30.2) | 14 (23.3) | 6 (17.1) | |

| 5–10 years | 59 (16.2) | 6 (10.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| >10 years | 134 (36.8) | 12 (20.0) | 5 (14.3) | |

| No informationa | 49 (11.9) | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Anatomical site of symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Palms | 226 (54.7) | |||

| Soles of the feet | 224 (54.2) | |||

| Axillae | 215 (52.1) | |||

| Face | 14 (3.4) | |||

| Scalp | 13 (3.1) | |||

| Number of symptomatic sites, n (%) | ||||

| One | 202 (48.9) | |||

| Two | 132 (32.0) | |||

| Three or four | 75 (18.2) | |||

| No informationa | 4 (1.0) | |||

The information was not found from patient records.

LHH: local hyperhidrosis; GHH: generalized hyperhidrosis; UHH: unspecified hyperhidrosis; SD: standard deviation.

Table II.

Anatomical site of symptoms in local hyperhidrosis by age

| 0–18 years n = 78 | 18–25 years n = 119 | 25–40 years n = 143 | 40–90 years n = 73 | All n = 413 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Palms | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 19 (24.4) | 45 (37.8) | 79 (55.2) | 44 (60.3) | 187 (45.3) | |

| Yes | 59 (75.6) | 74 (62.2) | 64 (44.8) | 29 (39.7) | 226 (54.7) | |

| Soles | 0.659 | |||||

| No | 36 (46.2) | 51 (42.9) | 71 (49.7) | 31 (42.5) | 189 (45.8) | |

| Yes | 42 (53.8) | 68 (57.1) | 72 (50.3) | 42 (57.5) | 224 (54.2) | |

| Axillae | 0.003 | |||||

| No | 43 (55.1) | 57 (47.9) | 53 (37.1) | 45 (61.6) | 198 (47.9) | |

| Yes | 35 (44.9) | 62 (52.1) | 90 (62.9) | 28 (38.4) | 215 (52.1) | |

| Face | 0.026 | |||||

| No | 78 (100.0) | 117 (98.3) | 137 (95.8) | 67 (91.8) | 399 (96.6) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (4.2) | 6 (8.2) | 14 (3.4) | |

| Scalp | < 0.001 | |||||

| No | 78 (100.0) | 117 (98.3) | 140 (97.9) | 65 (89.0) | 400 (96.9) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.1) | 8 (11.0) | 13 (3.1) | |

| Whole body | 0.798 | |||||

| No | 78 (100.0) | 118 (99.2) | 142 (99.3) | 72 (98.6) | 410 (99.3) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) | |

Comorbidities

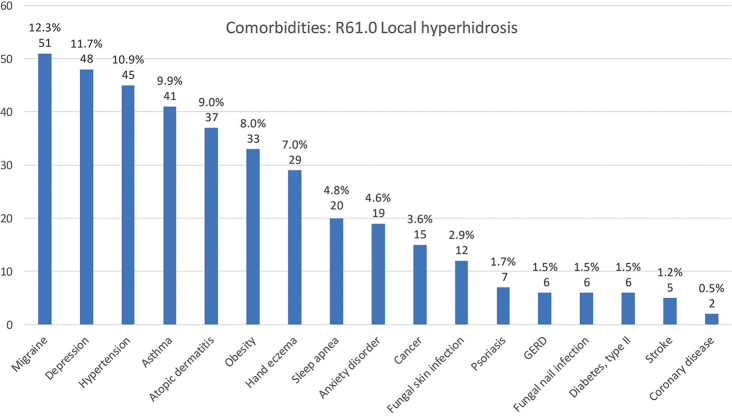

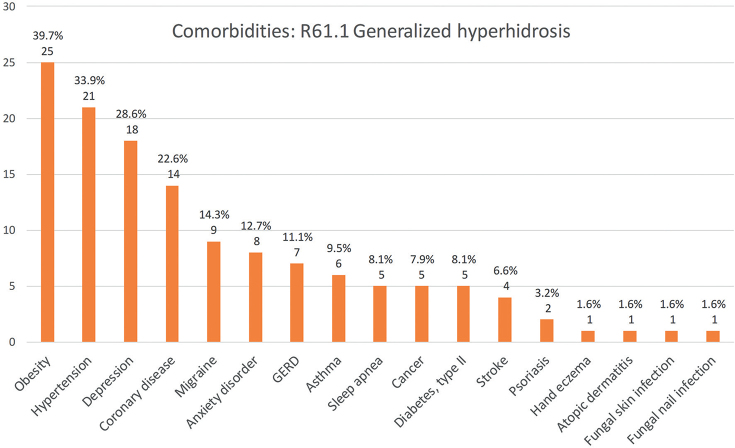

The most common comorbidity in the whole study population was depression (14.3%), which was more common in generalized HH (18/63, 28.6%) than in local HH (48/413, 11.6%) (p < 0.001). Migraine, asthma and atopic dermatitis were common comorbidities in patients with local HH. In patients with generalized HH, the most frequent comorbidities were obesity (39.7%), high blood pressure (33.9%), and depression (28.6%). Anxiety disorders were also common in patients with generalized HH (12.7%). Anxiety disorders were also seen more frequently in patients treated with BTIs (9/117; 7.7%) compared with patients treated only with iontophoresis (10/234; 3.9%), although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.3). Dermatological comorbidities, such as hand eczema, were seen more often in local HH than in generalized HH (7.0% vs 1.6%), but, again, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.2). The absolute numbers and prevalence of the studied comorbidities in local and generalized HH are shown in Figs 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Comorbidities in patients with local hyperhidrosis in Northern Finland between 1996 and 2019. Absolute numbers and percentage of local hyperhidrosis patients with named condition (n = 413).

Fig. 2.

Comorbidities in patients with generalized hyperhidrosis in Northern Finland between 1996 and 2019. Absolute numbers and percentage of generalized hyperhidrosis patients with named condition (n = 63).

Treatments and treatment outcomes

As seen in Table III, the majority (68.9%) of patients with local HH had used topical aluminium chloride-containing antiperspirants. Iontophoresis was also used for most patients with local HH (81.8%). The most typical duration of iontophoresis treatment was more than 6 months (25.7%), but quite a large proportion of patients tried it only briefly (11.6%). Iontophoresis provided adequate symptom relief for a large proportion of patients (40.4%), but there were still many patients who did not experience any symptom relief (22.8%).

Table III.

Treatments and treatment outcomes of patients with hyperhidrosis

| LHH n = 413 | GHH n = 63 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Antiperspirants | 284 (68.9) | 14 (22.2) | 0.001 |

| Iontophoresis | 337 (81.8) | 12 (19.0) | |

| Duration of the treatment | |||

| Did not try | 8 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.592 |

| Only trial | 39 (11.6) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 1–2 months | 31 (9.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| 3–4 months | 49 (14.6) | 3 (25.0) | |

| 4–6 months | 57 (17.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| > 6 months | 86 (25.7) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Exact usage time unknown | 65 (19.4) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Benefit of the treatment | 0.689 | ||

| No relief | 77 (22.8) | 3 (25.0) | |

| A little relief | 32 (9.5) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Moderate relief | 25 (7.4) | 1 (8.3) | |

| Adequate relief | 136 (40.4) | 2 (16.7) | |

| No informationa | 88 (26.1) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Botulinum toxin injections | 117 (28.5) | 5 (7.9) | 0.001 |

| Injection site | |||

| Axillae | 79 (67.5) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Palms | 33 (28.2) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Soles of the feet | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No informationa | 2 (1.7) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Number of injections | 0.711 | ||

| 1 | 81 (69.2) | 4 (80.0) | |

| 2–3 | 14 (12.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| More | 22 (18.8) | 1 (20.0) | |

| Benefit of treatment | 0.869 | ||

| No relief | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| A little relief | 13 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Adequate relief | 53 (45.3) | 1 (20.0) | |

| No informationa | 49 (41.8) | 4 (80.0) | |

| Anticholinergic therapy | 38 (9.2) | 26 (41.3) | |

| Benefit of the treatment | 0.382 | ||

| No relief | 8 (21.1) | 2 (7.7) | |

| A little relief | 8 (21.1) | 7 (26.9) | |

| Adequate relief | 10 (26.3) | 7 (26.9) | |

| No informationa | 12 (31.6) | 10 (38.5) | |

| Surgery treatments for hyperhidrosis | 13 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

The information was not found from patient records.

LHH: local hyperhidrosis; GHH: generalized hyperhidrosis.

Botulinum toxin injections (BTIs) were used in more than one-quarter of the patients with local HH (28.5%). The most common injection sites were the axillae and palms (67.5% and 28.2%, respectively) and the most common number of BTIs given was only 1 (69.2%). The majority of patients treated with BTIs (82/117, 70.1%) had previously tried iontophoresis with poor results: 38/82 (46.3%) did not experience any symptom relief (data not shown). Almost one-third of patients treated with BTIs (35/117, 29.9%) did not receive any iontophoresis treatment (data not shown). Surgical interventions (thoracic sympathectomy and axillary hidradenectomy) were used only for a few patients with local HH (3.2%), but for none of the patients with generalized HH.

Oral anticholinergic medication (OAM, almost always oxybutynin) was used for a small group of patients with local HH (9.2%), but was the most common treatment for generalized HH (41.3%). More than half of the patients with generalized HH (53.8%) experienced at least some symptom relief with OAM.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated HH comorbidities and treatments in 511 subjects, based on hospital patient records. Local HH was the most common form, affecting more females than males, and more commonly seen in younger patients than other types of HH. Most of the patients had used iontophoresis as a treatment, and up to 40% considered this treatment useful. One of the most common comorbidities in both local and generalized HH was depression.

HH can affect people at any age (2); however, it is most common in adolescents and young adults (8, 13), as was also seen in the current study (mean age 27 years in local HH). Nevertheless, in line with previous reports (14), patients with generalized HH in the current study were older than those with local HH (mean age 40 years). Previous studies have also shown that anatomical sites affected by HH differ by age (3, 15). The current study strengthens these findings, demonstrating that the palms and soles were the most typically affected sites in the youngest age group, whereas the axillae were more common sites after the age of 18 years.

HH is thought to be an underdiagnosed condition (8). Up to 36% of patients with local HH In the current study had had symptoms for more than 10 years before receiving a diagnosis. There are many possible reasons for this long delay in diagnosis: HH is often considered a “normal” or non-medical condition. Patients may also be ashamed of their HH symptoms, and not seek medical help. In addition, patients may not know that there are treatments available for the condition.

There are only a few studies broadly analysing HH comorbidities (3, 14, 16). Nevertheless, the quality of life in patients with HH has been studied widely and is shown to be reduced (8). Furthermore, in many studies, HH has been associated with mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety (14, 17–19). Correspondingly, the degree of difficulty in HH has been shown to correlate with the degree of depression and anxiety (18, 20). The most common comorbidity in the current study was depression, which was present in 14.3% of all patients, while as many as 28.6% of patients with generalized HH had depression. In Finland, the total prevalence of depressive disorders in those aged 30 years or over was 9.6% in 2011 (21). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of anxiety disorders between patients with local HH (4.6%) and the general population in Finland (4%) (22). However, patients with generalized HH had a higher prevalence of anxiety disorders (12.7%). In addition, in the current study, anxiety disorders were more common in patients treated with BTIs compared with those treated only with iontophoresis. We suspect that these patients had more severe symptoms and therefore did not experience adequate relief from first-line treatment (in the current patients, BTIs were usually used if iontophoresis was ineffective). This finding also aligns with those of previous studies, which have reported an association between the degree of difficulty in HH and the degree of anxiety (18, 20).

Regarding the other comorbidities in this study, migraine was a common condition in both local (12.3%) and generalized HH (14.3%). In a recent Finnish register data study among occupational healthcare users, the prevalence of migraine was approximately 9.5% (23). Correspondingly, obesity was quite frequent in our patients, and occurred more often in those with generalized HH. Previously, Astman et al. (16) studied the association between obesity and hyperhidrosis among 2.77 million adolescents, and demonstrated the relationship between these 2 conditions. Patients with HH have also been reported having more maceration of the skin, atopic and eczematous dermatitis, and pitted keratolysis infections (3). In the current study, hand eczema was present in 7.0% of patients with local HH, being higher than, for example, reported in the review by Thyssen et al. (24), who studied the prevalence of hand eczema in general populations (point prevalence 4.0%). Atopic dermatitis was present in 9.0% of patients with local HH. In general, the prevalence of self-reported atopic dermatitis in Finland is approximately 17–30% in the age group 25–45 years (25), and, thus, atopic dermatitis was not a frequent diagnosis in the current study. The association between cutaneous infections and HH has also been reported in previous studies. In particular, the risk of fungal infections has been shown to be increased in patients with HH (3), probably due to the moist environment in the skin favouring fungal growth. However, fungal skin infection was not a frequent comorbidity in the current study, as it was present in only 2.9% of patients with local HH.

The most commonly used treatments included topical antiperspirants, iontophoresis and BTIs. Antiperspirants were typically used for the axillae, and iontophoresis for the soles of the feet and palms. The majority of patients treated with iontophoresis and BTIs had first used topical antiperspirants containing aluminium chloride, which is in line with clinical recommendations: According to the American Academy of Family Physicians, topical antiperspirants should be used as a first-line treatment in most cases of HH regardless of the anatomical site or severity of the symptoms (1). More than 40% of patients using iontophoresis had received benefit from the treatment. Nevertheless, approximately 20% of patients had found iontophoresis to be totally ineffective. There were also some patients who had tried the treatment only once or had used it for a short time (1–2 months). Discomfort during the treatment, or the perception that it was difficult to use, may have been reasons to stop iontophoresis. Some patients may also experience side-effects during iontophoresis, such as short-term skin irritation, which can lead to discontinuation of treatment. BTIs were used in 28% of the current study patients and the majority were satisfied with the treatments. Newer treatment options, such as microwave technology, laser therapy, or fractionated microneedle radiofrequency therapy, were not used in the current study population.

The majority of the patients with local and unspecified HH were female. Correspondingly, in a previous study performed in Sweden, severe HH was shown to affect more females than males (14). However, there are also opposite findings: in another study, male predominance was seen in patients with HH (5). The current result may be explained partly by the fact that, in general, males are less likely to seek medical help.

Strength and limitations

The major strength of the current study is that all patients were evaluated and diagnosed by experienced dermatologists. Oulu University Hospital is the only hospital with a department of dermatology in the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District (NOHD), providing special healthcare in dermatology for a Finnish population of 413,830. Thus, the current study includes all the dermatological patients with HH treated in NOHD between 1996 and 2019.

The current study has some limitations. The study was retrospective and based on medical reports and, hence, the information about patients and their treatment was, in some cases, incomplete (e.g. the benefit from the iontophoresis-treatment was unknown for some patients because of incomplete medical reports). In addition, the patients with HH in the axillae typically received only one BTI, due to the policy that in order to get more than one injection, the patients had to use private healthcare. Multiple injections were given only in the palms if HH threatened the patient’s working ability. Due to the single-injection strategy, patients did not have any control visits in public healthcare; as a result, the perceived efficacy of BTIs was unknown for a large group of patients (41.9%). A further limitation is that we did not analyse the association between medications and HH, even though HH can be caused by many antidepressive medications, for example.

Conclusion

This study adds to our knowledge of HH, its treatments and comorbidities. HH especially affects young adults. In addition, depression and anxiety were frequently seen in the current study patients, and this must be borne in mind when treating patients with HH. Awareness of HH must be increased in order to improve diagnosis of the condition. Similarly, more information about the treatments available for HH should be provided to patients and physicians.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.McConaghy JR, Fosselman D. Hyperhidrosis: management options. Am Fam Physician 2018; 97: 729–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: etiology and clinical work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walling HW. Primary hyperhidrosis increases the risk of cutaneous infection: a case-control study of 387 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61: 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strutton DR, Kowalski JW, Glaser DA, Stang PE. US prevalence of hyperhidrosis and impact on individuals with axillary hyperhidrosis: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 51: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augustin M, Radtke MA, Herberger K, Kornek T, Heigel H, Schaefer I. Prevalence and disease burden of hyperhidrosis in the adult population. Dermatology 2013; 227: 10–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenach JH, Atkinson JL, Fealey RD. Hyperhidrosis: evolving therapies for a well-established phenomenon. Mayo Clin Proc 2005; 80: 657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamudoni P, Mueller B, Halford J, Schouveller A, Stacey B, Salek MS. The impact of hyperhidrosis on patients’ daily life and quality of life: a qualitative investigation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017; 15: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doolittle J, Walker P, Mills T, Thurston J. Hyperhidrosis: an update on prevalence and severity in the United States. Arch Dermatol Res 2016; 308: 743–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walling HW, Swick BL. Treatment options for hyperhidrosis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2011; 12: 285–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanclemente G, Burgos C, Nova J, Hernandez F, Gonzalez C, Reyes MI, et al. The impact of skin diseases on quality of life: a multicenter study. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2017; 108: 244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Bahar R, Kalia S, Huang RY, Phillips A, Su M, et al. Hyperhidrosis prevalence and demographical characteristics in dermatology outpatients in Shanghai and Vancouver. PloS One 2016; 11: e0153719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shayesteh A, Janlert U, Brulin C, Boman J, Nylander E. Prevalence and characteristics of hyperhidrosis in sweden: a cross-sectional study in the general population. Dermatology 2016; 232: 586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estevan FA, Wolosker MB, Wolosker N, Puech-Leao P. Epidemiologic analysis of prevalence of the hyperhidrosis. An Bras Dermatol 2017; 92: 630–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astman N, Friedberg I, Wikstrom JD, Derazne E, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Afek A, et al. The association between obesity and hyperhidrosis: a nationwide, cross-sectional study of 2.77 million Israeli adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 81: 624–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristensen JK, Moller S, Vestergaard DG, Horsten HH, Swartling C, Bygum A. Anxiety and depression in primary hyperhidrosis: an observational study of 95 consecutive Swedish outpatients. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristensen JK, Vestergaard DG, Swartling C, Bygum A. Association of primary hyperhidrosis with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross KM, Schote AB, Schneider KK, Schulz A, Meyer J. Elevated social stress levels and depressive symptoms in primary hyperhidrosis. PLoS One 2014; 9: e92412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahar R, Zhou P, Liu Y, Huang Y, Phillips A, Lee TK, et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with or without hyperhidrosis (HH). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markkula N, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Pirkola S, Pena S, Saarni S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder and dysthymia in an eleven-year follow-up – results from the Finnish Health 2011 Survey. J Affect Disord 2015; 173: 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.OECD EU (2018). Health at a glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle, OECD Publishing, Paris; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korolainen MA, Kurki S, Lassenius MI, Toppila I, Costa-Scharplatz M, Purmonen T, et al. Burden of migraine in Finland: health care resource use, sick-leaves and comorbidities in occupational health care. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 13–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thyssen JP, Johansen JD, Linneberg A, Menné T. The epidemiology of hand eczema in the general population–prevalence and main findings. Contact Derm 2010; 62: 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vartiainen E, Petays T, Haahtela T, Jousilahti P, Pekkanen J. Allergic diseases, skin prick test responses, and IgE levels in North Karelia, Finland, and the Republic of Karelia, Russia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109: 643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]