Abstract

Background

Bidens pilosa L., an annual herb, has recently been shown to be a potential Cd-hyperaccumulating plant. The germination characteristics of B. pilosa have been documented, while the difference among populations remains unclear. Understanding variability in seed germination among populations is crucial for determining which populations to use for soil remediation programs.

Results

Present study was conducted to compare the requirements of temperature and water potential for germination of B. pilosa cypselae (the central type, hereafter seeds) from three populations using the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models. Seeds of three populations were incubated at seven constant temperatures (8, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 °C) and at each of four water potentials (0, -0.3, -0.6, and -0.9 MPa). The results showed that germination percentage and rate of B. pilosa seeds were significantly by population, temperature, water potential and their interaction except for the interaction of population and water potential. Seeds from Danzhou population displayed a higher base temperature (Tb) for germination than those from Guilin and Baoshan population, however the ceiling temperature (Tc) had no consistent level among the populations but varied according to the water potential. In addition, the median base water potential [ψb(50)] for germination of seeds from Danzhou population was higher than that for seeds from Baoshan and Guilin population at low temperatures (< 25 °C), which was opposite at high temperatures (≥ 25 °C).

Conclusion

Seed germination requirements of B. pilosa on temperature and water differed significantly among populations. Differences in seed germination among populations may be complicated, which could not be simply explained by the temperature and rainfall conditions where the seeds were produced as previously reported. The results suggested that programme management should consider variation in seed germination traits when select which population could be applied to what kind of target remediation sites.

Keywords: Seed, Germination, Hyperaccumulator, Temperature, Water potential

Background

Cadmium (Cd), produced by industrial activities such as mining, electroplating, and waste irrigation, is one of the most hazardous and ubiquitous contaminants in soil and water [1]. Thus, it remains a possible health risk to humans due to bioaccumulation in the food chain, which can lead to lethal disorders like “itai-itai disease” [2]. Therefore, cleanup of Cd-contaminated soil is increasingly imperative. The concept of phytoremediation was first introduced by Chaney et al. (1999), who recommended leveraging the accumulation capability of hyperaccumulator plants to remove heavy metals from the soil which is a cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and sustainable method [3, 4]. To date, over 400 plant species have been discovered as natural hyperaccumulators around the world, but fewer than 10 naturally occurring species have been reported to hyperaccumulate Cd, including Amaranthus hybridus, Arthrocnemum macrostachyum, Chara aculeata, and Phytolacca americana [5].

Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae), is an annual herb that grows widely from the tropics to subtropical zones. After being first reported in Hong Kong in 1857, B. pilosa has spread and is distributed throughout east, central south, and southwest China [6]. It's been advocated as a human treatment for diseases including protozoan infection, bacterial infection, gut disorders, immunological disorders, and so on [7]. Over 200 phytochemicals have been identified from B. pilosa, including polyacetylenes and flavonoids proposed as the active compounds in treating malaria [8]. Recently, it has been proven to be a potential Cd-hyperaccumulating plant [9], which has the characteristics of higher biomass, faster growth, higher seed production, and greater tolerance to adverse environmental conditions than other Cd hyperaccumulators [1].

Seed germination is the first crucial growth stage for successful seedling establishment for soil remediation programs and is affected by various environmental factors, among which temperature and moisture are of overriding importance [10–16]. It is notable that seeds from different environmental conditions of a species’ range often show variability in germination requirements [17–20]. All seeds require a specific range of temperatures for germination; this is called the cardinal temperature: the base temperature (Tb), optimal temperature (To), and ceiling temperature (Tc), which varies according to the climate conditions under which the seeds originated [21–24]. Additionally, the base water potential required for seed germination varies widely among seeds from different provenances, populations, or geographic locations [20, 25–27]. It is crucial for land managers to understand the variations in germination requirements for seeds from diverse populations to ensure that the seeds are sown at the most favorable time and conditions to support germination for establishment of robust plants that can accomplish “phytoremediation” [12, 21].

To date, seed germination requirements for temperature and moisture have been well documented through utilization of the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models [28–30]. Research on threshold values has been mostly conducted for agricultural and ecological purposes in species, such as Carthamus tinctorius [29], Brassica napus [31], Stipa species [32], Camelina sativa [33], and Alyssum homolocarpum [34]. In addition, previous studies on B. pilosa often focused on its metabolites as an edible medicinal plant [8, 35–37], the plant’s mechanism of Cd accumulation/translocation [1, 38], the reasons for its successful invasiveness [39], and the alleviation of dormancy as a weedy species [40]. Previous studies showed that seed germination of B. pilosa could occur over a wide range of temperatures [41–44], and light greatly stimulated seed germination [43]. In addition, B. pilosa was found to germinate at high salt levels (13% at 100 mM NaCl and 3% at 200 mM NaCl), but preferred a moist environment that less than 3% of the seed germinated at -0.75 MPa and germination ceased at -0.8 MPa [41, 43]. However, collaborative response of various environmental factors such as temperature and water on seed germination of B. pilosa had not been studied. In particular, differences in seed germination characteristics among populations have been reported by many previous studies [24, 26, 31], but little research on this species [45, 46].

Cd pollution mainly happened in the southwest, central and north China including Yunnan, Guangxi, Guangdong and other areas where there were rich in cadmium resource [47], meanwhile combined the widely distribution of B. pilosa in China [48, 49]. Thus, we chose seeds collected from Baoshan population in Yunnan Province, Guilin population in Guangxi Province and Danzhou population in Hainan Province to test the effect of temperature and water potential on the seed germination of B. pilosa. Further used the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models to compare seed germination requirements among populations based on the experimental data. The results of this study will be useful for understanding variability in the seed germination requirements of B. pilosa across a range of populations, which will lead to improved seed sourcing and seed application timing decisions for soil remediation programs.

Results

Effect of temperature and water potential on the percentage and rate of B. pilosa seed germination

Population, temperature, water potential, and all their interactions had significant effects on the seed germination percentage and rate of B. pilosa, except for the interaction between population and water potential (Table 1). With increasing temperature, the final germination percentage and germination rate climbed and then fell at all water potentials, while they declined as the water potential fell at all temperatures for the three populations (Table 2). The highest germination percentage and germination rate were observed at 25 °C for the three populations, suggesting that 25 °C was likely considered the optimal temperature for seed germination of B. pilosa. From the results, we found that seed germination percentage at 8 °C under -0.6 MPa was shown as Baoshan > Guilin > Danzhou, while was shown as Danzhou > Guilin > Baoshan at 35 °C under -0.6 MPa. Then the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models were utilized to investigate the seed germination response to temperature and water potential further. Based on the seed germination rate (1/t50), 8, 10, 15, and 20 °C were determined as the suboptimal temperatures and 25, 30, and 35 °C as the supraoptimal temperatures. The meanings of all the parameters in present study were shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Effect of population, temperature and water potential on seed germination percentage and rate (1/t50) of B. pilosa were analyzed by GLMMs based on binomial distribution

| Source of variation | Chi | Germination percentage (%) | Chi | Germination rate (1/t50) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | P | df | P | |||

| Population (P) | 40.618 | 2 | 0.000*** | 9.816 | 2 | 0.007** |

| Temperature (T) | 69.607 | 6 | 0.000*** | 1047.690 | 6 | 0.000*** |

| Water potential (W) | 95.603 | 3 | 0.000*** | 7.620 | 2 | 0.022* |

| P × T | 36.225 | 12 | 0.000*** | 88.658 | 12 | 0.000*** |

| P × W | 2.242 | 6 | 0.896 | 5.980 | 4 | 0.200 |

| T × W | 36.106 | 18 | 0.007** | 422.804 | 12 | 0.000*** |

| P × T × W | 63.701 | 36 | 0.003** | 104.628 | 24 | 0.000*** |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001

Table 2.

The effect of temperature and water potential on seed germination percentage and rate of B. pilosa from three populations

| Population | Temperature (℃) |

Germination percentage (%) | Germination rate (1/t50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 MPa |

-0.3 MPa |

-0.6 MPa |

-0.9 MPa |

0 MPa |

-0.3 MPa |

-0.6 MPa |

-0.9 MPa |

||

| Baoshan | 8 | 80.00c | 74.67b | 26.00c | 0.00a | 0.05d | 0.05e | 0.00c | - |

| 12 | 94.00ab | 96.00a | 82.67a | 4.00a | 0.15c | 0.13c | 0.07b | - | |

| 15 | 98.67a | 96.00a | 92.00a | 2.67a | 0.19c | 0.14c | 0.09a | - | |

| 20 | 98.00ab | 93.33a | 88.67a | 3.33a | 0.32b | 0.18a | 0.09a | - | |

| 25 | 97.33ab | 95.33a | 86.00a | 8.00a | 0.43a | 0.16b | 0.07b | - | |

| 30 | 92.00ab | 86.00ab | 38.00b | 0.00a | 0.37b | 0.08d | 0.00c | - | |

| 35 | 89.33c | 41.33c | 4.67d | 0.00a | 0.13c | 0.00f | 0.00c | - | |

| Guilin | 8 | 76.67b | 68.67b | 20.67c | 0.00b | 0.05e | 0.04e | 0.00d | - |

| 12 | 96.67a | 94.00a | 69.33b | 3.33b | 0.10d | 0.12d | 0.07b | - | |

| 15 | 98.67a | 98.00a | 85.33ab | 3.33b | 0.15d | 0.15 cd | 0.07b | - | |

| 20 | 96.00a | 94.00a | 94.67a | 6.00b | 0.41b | 0.21b | 0.11a | - | |

| 25 | 98.67a | 99.33a | 84.67ab | 16.00a | 0.50a | 0.27a | 0.08b | - | |

| 30 | 97.33a | 94.00a | 65.33b | 4.67b | 0.32c | 0.17bc | 0.04c | - | |

| 35 | 82.67b | 69.33b | 23.33c | 0.00b | 0.10d | 0.05e | 0.00d | - | |

| Danzhou | 8 | 48.00d | 30.00d | 7.33d | 0.00c | 0.00e | 0.00d | 0.00c | - |

| 12 | 95.33ab | 96.00ab | 93.33a | 9.33b | 0.13d | 0.09c | 0.07b | - | |

| 15 | 94.00ab | 96.00ab | 82.00ab | 8.67b | 0.16d | 0.10bc | 0.06b | - | |

| 20 | 97.33a | 100.00a | 92.67a | 12.67ab | 0.37b | 0.29a | 0.10a | - | |

| 25 | 97.33a | 95.33ab | 88.00a | 16.00a | 0.53a | 0.29a | 0.10a | - | |

| 30 | 86.67c | 86.67b | 74.00b | 8.00b | 0.31c | 0.14b | 0.10a | - | |

| 35 | 88.67bc | 59.33c | 31.33c | 0.67c | 0.15d | 0.04d | 0.00c | - | |

Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different temperatures at the same water potential within each population (DUNCAN, P < 0.05). “-” means no data have been calculated

Table 3.

The meanings of the parameters in present study

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Tb | the base temperature |

| To | the optimal temperature |

| Tc | the ceiling temperature |

| tg | the time to a given specific germination percentage g |

| θT(50) | the thermal time for 50% of seeds to germinate |

| Tc(50) | the ceiling temperature for 50% of seeds to germinate |

| θT | the thermal time constant |

| σθT | the standard deviation of log θT requirements |

| σTc | the standard deviation of Tc |

| θH | the hydrotime constant |

| ψb(50) | the median base water potential |

| σψb | the standard deviation of ψb(50) |

| θHT | the hydrothermal time constant |

Thermal time model

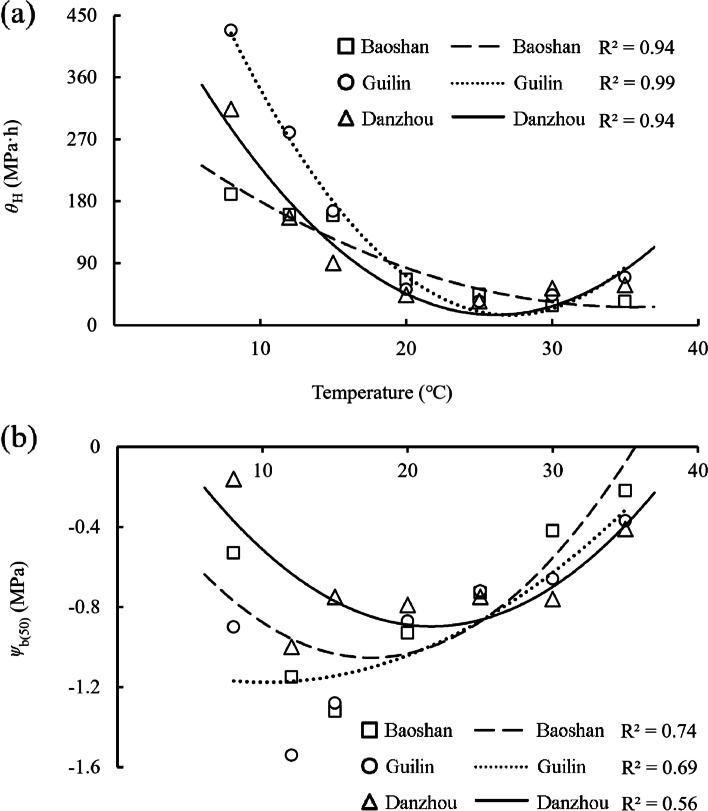

The estimated values of the base temperature (Tb), the thermal time for 50% of seeds to germinate [θT(50)], the ceiling temperature for 50% of seeds to germinate [Tc(50)] and the thermal time constant (θT) were varied with water potentials. The Tb at 0 and -0.3 MPa was shown to be Danzhou > Guilin > Baoshan. The order of the Tc was Baoshan > Danzhou > Guilin at 0 MPa, Guilin > Danzhou > Baoshan at -0.3 MPa, and Danzhou > Guilin > Baoshan at -0.6 MPa (Table 4). A decreased Tb and Tc associated with water stress would limit the temperature range of germination under water stress conditions, especially for Baoshan population. The estimated values of the θT(50) and the Tc(50) is plotted against water potential, and the θT(50) increased as the water potential decreased at suboptimal temperatures (Fig. 1a), and the Tc decreased as the water potential decreased at supraoptimal temperatures for all the three populations (Fig. 1b).

Table 4.

Seed germination parameters of B. pilosa from three populations based on thermal-time model analysis at suboptimal and supraoptimal temperature for different water potentials

| Population | Water potential (MPa) |

suboptimal temperature | supraoptimal temperature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θT(50) (℃·h) | σθT | Tb(℃) | R2 | θT (℃·h) | σTc | Tc(50) (℃) | R2 | ||

| Baoshan | 0 | 1111.92 | 0.65 | 5.38 | 0.92 | 890.68 | 7.30 | 41.96 | 0.82 |

| -0.3 | 1969.45 | 0.66 | 4.58 | 0.91 | 1326.15 | 3.75 | 34.63 | 0.93 | |

| -0.6 | 3374.73 | 0.69 | 4.41 | 0.84 | 1919.41 | 3.24 | 30.97 | 0.95 | |

| Guilin | 0 | 1173.11 | 0.76 | 5.95 | 0.80 | 637.28 | 5.30 | 38.84 | 0.87 |

| -0.3 | 1561.64 | 0.67 | 5.58 | 0.87 | 825.91 | 5.94 | 36.07 | 0.72 | |

| -0.6 | 3201.87 | 0.63 | 5.10 | 0.90 | 2195.41 | 6.29 | 33.25 | 0.89 | |

| Danzhou | 0 | 1039.63 | 0.77 | 6.81 | 0.91 | 823.21 | 6.58 | 41.52 | 0.87 |

| -0.3 | 1505.51 | 0.68 | 6.66 | 0.89 | 733.08 | 6.45 | 35.64 | 0.85 | |

| -0.6 | 4725.14 | 0.59 | 5.14 | 0.76 | 1596.29 | 6.14 | 34.04 | 0.81 | |

θT(50) = thermal time for 50% of seeds to germinate, σθT = standard deviation of log θT(50), Tb = constant base temperature in suboptimal temperature range. θT = constant thermal time, σTc = standard deviation for Tc(50) at supraoptimal temperature, Tc(50) = maximum temperature for 50% of seeds to germinate

Fig. 1.

The relationship between the temperature threshold and water potential. a the thermal time [θT(50)] at suboptimal temperatures, b the ceiling temperature [Tc(50)] at supraoptimal temperatures

Hydrotime model

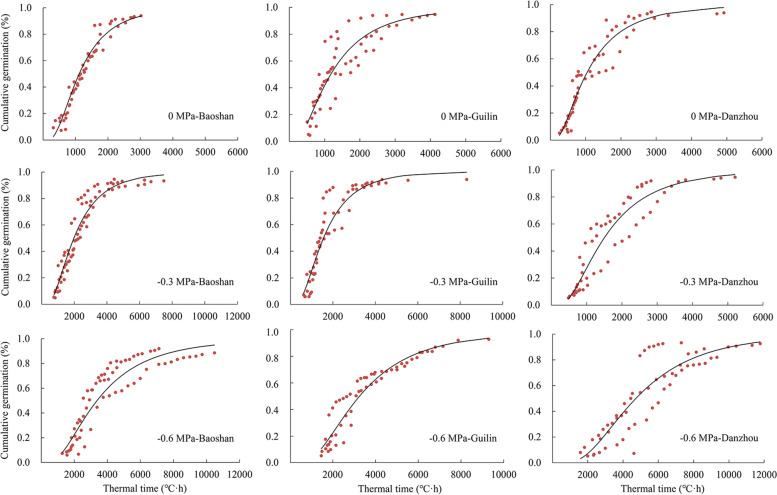

The hydrotime time models were fitted to seed germination data of B. pilosa under different temperature regimes, and the estimated values are shown in Table 5. The hydrotime constant (θH) decreased and then increased with increasing temperature for all three populations, and the lowest value was obtained at 30 °C for Baoshan population, and at 25 °C for Guilin and Danzhou population. The median base water potential [ψb(50)] decreased and then increased with increasing temperature for all three populations, and the lowest value was obtained at 15 °C for Baoshan population, and at 12 °C for Guilin and Danzhou population. The estimated values of the ψb(50) and the θH is plotted against temperature, and which decreased and then increased with increasing temperature for all the three populations (Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Seed germination parameters for response of B. pilosa to water potential from three populations based on hydrotime model analysis for different temperatures

| Population | Temperature (℃) | θH (MPa·h) | ψb(50) (MPa) | σψb | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baoshan | 8 | 190.20 | -0.53 | 0.56 | 0.73 |

| 12 | 160.23 | -1.15 | 0.48 | 0.85 | |

| 15 | 159.07 | -1.32 | 0.52 | 0.89 | |

| 20 | 66.06 | -0.93 | 0.37 | 0.77 | |

| 25 | 44.09 | -0.73 | 0.27 | 0.64 | |

| 30 | 28.06 | -0.42 | 0.25 | 0.78 | |

| 35 | 34.01 | -0.22 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| Guilin | 8 | 428.40 | -0.90 | 0.43 | 0.86 |

| 12 | 279.78 | -1.54 | 0.82 | 0.74 | |

| 15 | 165.44 | -1.28 | 0.66 | 0.81 | |

| 20 | 52.00 | -0.87 | 0.31 | 0.74 | |

| 25 | 33.96 | -0.72 | 0.26 | 0.77 | |

| 30 | 43.23 | -0.66 | 0.29 | 0.80 | |

| 35 | 69.56 | -0.37 | 0.36 | 0.79 | |

| Danzhou | 8 | 313.91 | -0.16 | 0.68 | 0.81 |

| 12 | 156.35 | -1.00 | 0.47 | 0.64 | |

| 15 | 90.21 | -0.75 | 0.36 | 0.75 | |

| 20 | 43.81 | -0.79 | 0.30 | 0.73 | |

| 25 | 34.79 | -0.75 | 0.24 | 0.83 | |

| 30 | 53.34 | -0.76 | 0.47 | 0.77 | |

| 35 | 58.23 | -0.41 | 0.30 | 0.93 |

θH = constant hydrotime, ψb(50) = median base water potential, σψb = standard deviation of ψb(50)

Fig. 2.

The relationship between the water potential threshold and temperature. a the hydrotime constant (θH), b the median base water potential [ψb(50)]

Compared with Baoshan and Guilin populations, tolerance to water potential for seeds from Danzhou population was more sensitive to temperature. Our analyses revealed that the ψb(50) was essentially equal for the three populations at 25 °C, while seeds from Danzhou population were more tolerant to water stress at high temperature (T ≥ 25 °C), and those from Guilin and Baoshan population were more tolerant to water stress at lower temperatures (T < 25 °C) (Table 5).

Hydrothermal time model

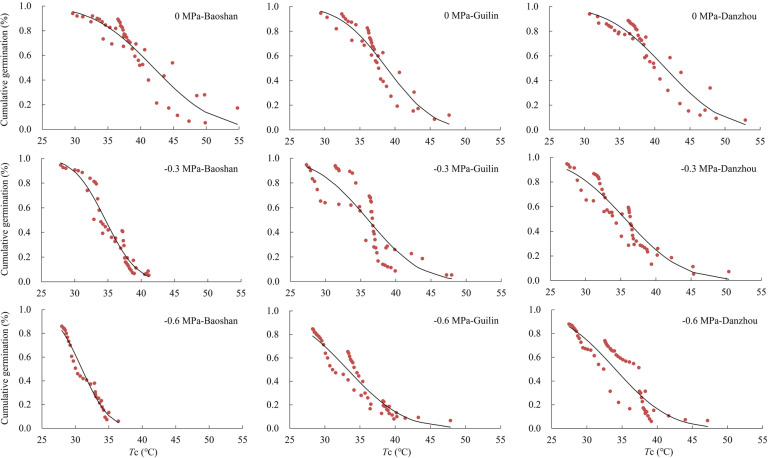

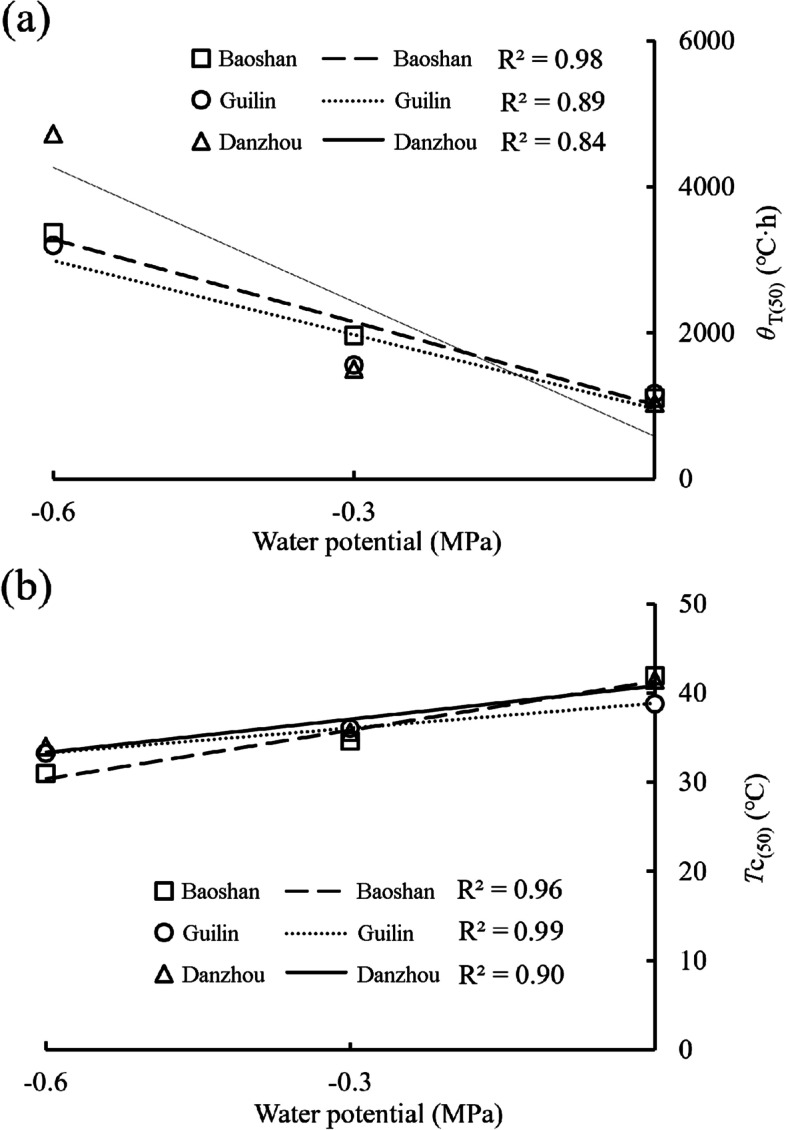

The hydrothermal time model parameters were utilized to explain the difference in germination timing of different populations over the combined range of temperatures and water potentials at which germination can occur. Based on the hydrothermal time model parameters displayed in Table 6, the estimated hydrothermal time constant (θHT) and ψb(50) are shown as Baoshan > Guilin > Danzhou, while the estimated Tb, optimal temperature (To) and θH values were opposite; that is, Danzhou > Guilin > Baoshan. The value of θHT indicated that the hydrothermal time required for completing germination for seeds from Danzhou population was shorter than those from Guilin and Baoshan population, and differences in ψb(50) values demonstrated that seeds from the Danzhou population were more sensitive to low water potential than those from the Guilin and Baoshan populations. The fits between seed germination and the thermal time at different water potentials at suboptimal temperatures (Fig. 3) and the fits between seed germination and the ceiling temperature at different water potentials at supraoptimal temperatures (Fig. 4) showed well agreements between the predicted and observed values for the Normal distribution.

Table 6.

Seed germination parameters for response of B. pilosa to temperature and water potential from three populations based on hydrothermal time model analysis

| Population | suboptimal temperature | supraoptimal temperature | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

θHT (MPa·°C·h) |

Tb (°C) |

ψb(50) (MPa) | σψb | R2 | kT |

To (°C) |

θH (MPa·h) |

ψb(50) (MPa) | σψb | R2 | |

| Baoshan | 1303.52 | 4.33 | -1.12 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 15.53 | 36.72 | -1.12 | 0.24 | 0.73 |

| Guilin | 1095.89 | 5.96 | -1.09 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.05 | 18.96 | 40.39 | -1.09 | 0.30 | 0.72 |

| Danzhou | 694.30 | 6.47 | -0.79 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 25.72 | 40.94 | -0.79 | 0.32 | 0.75 |

Fig. 3.

Thermal time of B. pilosa seeds from three populations predicted by thermal time models based on Normal distribution at different water potentials at suboptimal temperatures. The red circles show the observed mean thermal times and the black dashed lines show the predicted thermal times fitted by the thermal time model

Fig. 4.

Ceiling temperature of B. pilosa seeds from three populations predicted by thermal time models based on Normal distribution at different water potentials at supraoptimal temperatures. The red circles show the observed mean ceiling temperature and the black dashed lines show the predicted the ceiling temperature fitted by thermal time model

Discussion

Knowledge of variation in seed germination requirements among populations helps to plan effective strategies for seed selection and to understand where a species can grow and when to sow in soil remediation programs [12, 50]. Our preliminary results together with previous studies indicated that the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models could help to quantify seed germination behavior against various temperatures and water potentials [11, 29, 33, 50–53]. Seed germination percentage and rate of B. pilosa declined with decreasing water potential while increased and then decreased with increasing temperature for the three populations. Seed germination patterns of B. pilosa response to temperature and water potential varied among populations. Furthermore, seed germination requirements on temperature were affected by water potential and germination requirements on water potential were also influenced by temperature. Differences in seed germination behavior among populations within the range of this species could be particularly suited to increase their fitness under global climate change.

Seeds from different populations may differ greatly in their base, optimal, and ceiling germination temperatures [23, 54–56]. Seeds from Baoshan populations showed a lower Tb than those collected from Guilin and Danzhou population. Consistent with previous studies in Campanula americana [57], Cakile edentula [20], and Conyza bonariensis [24], which showed that seeds from cool environments had the ability to germinate at cold temperatures. This pattern suggested that seeds with low Tb could accumulate more heat units in a given time and would germinate faster than those from warm conditions, which would maximize the length of the growing season to ensure their growth and reproduction in cold regions [58]. As proposed by Cochrane et al. (2014), there had significant positively correlation between To and mean annual temperature at seed source for four congeneric Banksia species [59]. The order of To for seed germination of B. pilosa was Baoshan < Guilin < Danzhou in present study (Table 6), perhaps related to the annual mean temperature where the mother plant grew, but still need much more evidence to confirm. However, Barros et al. (2017) found that the regardless of seed origin, a temperature of 15 °C resulted in maximum germination of B. pilosa in the shortest time, and that some places of origin dormant seeds can partially explain the reason [60].

In addition to temperature, water potential is another important component in regulating seed germination and seedling growth in different plant species [33, 61, 62]. The results of this study demonstrated that seed germination response to water stress varied among different populations. Germination of seeds from Danzhou population had lower ψb(50) at high temperatures, whereas seeds from Guilin and Baoshan had lower ψb(50) at low temperatures. In general, seeds from dry habitats are more tolerant to water stress than those from habitats with wet conditions [12, 26]. For example, the highest osmotic tolerance of Silybum marianum was obtained from a location with a dry climate and the lowest mean annual precipitation [63]. However, seed tolerance to water stress is the confluence of several environmental conditions but not just a single factor. Seeds of Cakile edentula from the temperate climate zone displayed higher base water potential than those from the subtropical area because the high temperature increased evaporation and sand in the subtropical area could not hold sufficient water [20]. These results indicated that differences among populations in response to water potential could not be explained simply due to rainfall where seeds produce, which likely interacts with other factors, evaporation, soil moisture level, and temperature [13, 64, 65].

We identified an interaction effect between water potential and temperature in B. pilosa. The Tb for seed germination decreased as the water potential decreased at suboptimal temperatures (Table 4), similar to red fescue [61] and Camelina sativa [33], but inversely with other studies in Allium cepa and Daucus carota [66], Hordeum spontaneum and Phalaris minor [62]. The θT(50) for seed germination of B. pilosa increased with decreasing water potential for all the three populations (Table 4), indicating that seeds required greater thermal time to complete germination due to the slow germination rate under low water potential [29, 67]. The estimated ceiling temperature decreased linearly with decreasing water potential (Fig. 1b) at supraoptimal temperatures, as seem in other plants [14, 62]. This phenomenon means that seeds will not germinate when exposed to high temperature, especially at lower water potentials, which would ensure germination occurred in suitable conditions [11]. Such interacting effects could appear in different ways that ψb(50) could change considerably with temperature [68–70], which increased with temperature in Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) and red fescue (Festuca rubra ssp. litoralis) but decreased in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) [61]. The base water potential of Carthamus tinctorius decreased with increasing temperature from 5 to 20 °C but increased from 20 to 40 °C [29], which had the same trends as B. pilosa, but the turning point varied with population (Fig. 2b). This indicates that seeds are able to germinate with an elevated level of water stress under suitable temperature conditions [52]. It could be viewed as an adaptive strategy that reduces the accumulated hydrotime necessary for germination while increasing the probability of seed survival and seedling establishment under unfavorable conditions.

Seeds from Danzhou population showed lower θHT, higher ψb(50) and higher Tb than those from Guilin and Baoshan populations (Table 6). It suggested that seeds from Danzhou population tend to germinate more rapidly in the absence of water stress and low temperature restriction, but they are severely inhibited at lower water potential and temperature. For instance, germination rate for seeds from Danzhou population was higher under 0 and -0.3 MPa at 20 and 25 °C than those from the Guilin and Baoshan populations, whereas germination was strongly inhibited under 0 and -0.3 MPa at 8 °C compared with seeds from Guilin and Baoshan populations (Table 2). This result suggested that except for the hydrothermal time model, separate models at sub- and supra-optimal temperatures should be used in modeling germination, in agreement with previous studies [11, 66]. Seeds from the Baoshan population have a lower ψb(50) and a larger standard deviation (σψb) than those from Guilin and Danzhou populations (Table 6). In accordance with research on three dry land species (Danthonia caespitosa, Atriplex nummularia and A. vesicaria), seeds with lower ψb(50) and larger σψb could result in spreading germination across multiple rain events in a given year because of a higher germination plasticity [71].

Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrated that seed germination requirements on temperature and water of B. pilosa varied among populations. The estimated Tb and ψb(50) varied with water potential and temperature, respectively. Based on hydrothermal time model analysis, we found that seeds from Baoshan population were more tolerance to low temperature and low water potential than those from Guilin and Danzhou population. Although this information provide some suggestion on selecting seeds for soil remediation programs, further investigation is necessary under nature field environments to verify these findings. Whilst B. pilosa are plants with strong stress and disturbance resistances and such could be very useful as a potential Cd hyperaccumulator in phytoremediation technology theory and practice in many studies. It is worth noting that this species has a certain invasiveness, thus the plants should be mowed at or before the flowering period in practical applications.

Materials and methods

Seed sources

Cypselae of B. pilosa var. radiata (identification based on Chen et al. (2021) [49]) were collected from three populations located in Baoshan in Yunnan Province, Guilin in Guangxi Province, and Danzhou in Hainan Province in June 2021. The cypselae of each population were collected from several hundred plants, cleaned by hand in the laboratory, and then stored dry at 4 °C in a paper bag until use. There have two cypselae types (the peripheral type shorter and the central type longer) and the central type (more numerous than the shorter, hereafter seeds) were selected to conduct the germination experiments within two weeks of harvest. The climate and detailed information related to the three seed populations are shown in Table 7. The climate data are from weather stations near the seed collection sites, which were obtained from the Yunnan, Guangxi and Hainan Meteorological Service, respectively.

Table 7.

Information of seed collection location, climate information, seed morphology, thousand seed weight and initial germination percentage of B. pilosa from three populations

| Population | Longitude (E) |

Latitude (N) |

Altitude (m a.s.l) |

Monthly mean high temp. (°C) | Monthly mean low temp. (°C) | Monthly rainfall (mm) |

Annual mean temp (°C) |

Annual mean rainfall (mm) |

Seed length (mm) |

Seed width (mm) |

Awn length (mm) |

1000-seed weight (g) |

Initial germination (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||||||||||

| Baoshan | 98°52′37″ | 24°58′32″ | 734 | 24 | 26 | 26 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 49.2 | 90.3 | 126.7 | 21.3 | 850 | 8.24 ± 0.28b | 0.76 ± 0.01a | 2.31 ± 0.06b | 1.11 ± 0.01a | 98.7 |

| Guilin | 110°18′10″ | 25°04′10″ | 150 | 20 | 28 | 31 | 16 | 21 | 25 | 218.3 | 326.7 | 396.5 | 19.1 | 1750 | 9.20 ± 0.30a | 0.66 ± 0.01b | 2.69 ± 0.08a | 0.92 ± 0.08b | 99.3 |

| Danzhou | 109°29′02″ | 19°30′26″ | 137 | 30 | 35 | 34 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 77.5 | 229.3 | 194.4 | 23.2 | 1816 | 8.60 ± 0.29ab | 0.70 ± 0.02b | 2.58 ± 0.09a | 1.18 ± 0.01a | 100.0 |

Experimental designs

Four replicates of 50 seeds were placed in 9-cm-diameter Petri dishes on two sheets of filter paper moistened with 6 ml of distilled water (control) or different PEG solutions. Seeds were incubated in light (12 h/12 h, daily photoperiod) at 8, 12, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 °C under different water potentials of 0, -0.3, -0.6, and -0.9 MPa. The light source was white, fluorescent tubes, and the photon irradiance at the seed level was 60 μmol m−2 s−1 (400–700 nm). Water potential of PEG 6000 was determined using a Dew Point Microvolt meter HR-33 T (Wescor, Logan, Utah, USA) at different temperatures. To maintain a generally consistent water potential, Petri dishes were sealed with parafilm and seeds were transferred to new filter paper with fresh solutions every 48 h. Germination (radicle protrusion) was monitored daily for 28 days. The experimental design was the same for the three populations.

Germination rate was represented by 1/t50 and t50 is defined as the time to reach germination of 50%. The time taken for cumulative germination (t50) to reach 50% was estimated using a GERMINATOR package by using the visual basic module from the Microsoft Excel [72].

Data analysis

A repeated probit regression analysis was used in the thermal time, hydrotime, and hydrothermal time models to analyze the experimental data (the models and parameters are thoroughly explained in Bradford [73]).

A thermal time model was fitted to quantify the germination data with T at each ψ, and the models are shown below at the suboptimal temperature range (Eq. 1) and at the supraoptimal temperature range (Eq. 2):

| 1 |

| 2 |

where T, Tb, tg, θT(50), θT and Tc(50) are the real temperature (°C), the base temperature (°C), the time to a given specific germination percentage g (h), the thermal time for 50% of seeds to germinate at suboptimal temperatures (°C·h), the thermal time constant at supraoptimal temperatures (°C·h) and the ceiling temperature (°C) (varied among different seed percentages g in the population), respectively. σθT is the standard deviation of log θT requirements among individual seeds in the population, and σTc is the standard deviation of the ceiling temperature among individual seeds in the population. A probit analysis was conducted separately for each germination water potential.

A hydrotime model was fitted to quantify the germination data with ψ at each T, and the model is shown below:

| 3 |

where θH is the hydrotime constant (MPa·h), ψ is the actual water potential of the seedbed, ψb(50) is the median base water potential, tg is the actual time to germination of fraction g, and σψb is the standard deviation in base water potential among seeds within the population. Each germination temperature was subjected to a separate probit analysis. A hydrothermal time model was fitted to explain the germination data concurrently with ψ and T, and the models are shown below at the suboptimal temperature range (Eq. 4) and at the supraoptimal temperature range (Eq. 5):

| 4 |

| 5 |

where [kT · (T—To)] applies only when T > To and in the supra-optimal temperature range T—Tb is equal to T—To. θHT is the hydrothermal time constant (MPa·°C·h), ψ is the real water potential (MPa), ψb(50) is the base value of ψ inhibiting germination of 50% (MPa), tg is the real time to germination of percentage g (h) and kT is the line slope between ψb(50) and To < T, which is a constant value (MPa·°C−1).

All statistical analyses were conducted by SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were used investigate the effects of population, temperature, and water potential on the seed germination percentage and rate (1/t50) of B. pilosa by using the glmer function in the R package lme4. Population and water stress were used as fixed effects, while replicates were included as random effects in each model. Duncan's multiple range test was performed to compare the means of the seed germination percentage and rate under different temperatures at the same water potential level when significant variations were discovered. Differences between the virtual θT and predicted θT at suboptimal temperatures and differences between the virtual Tc and predicted Tc at supraoptimal temperatures were estimated based on thermal time models. Second-order polynomials were used to fit the relationship between the hydrotime constant/the base water potential and temperature.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiongying Jiang and Qian Liu for helping collect seeds.

Authors’ contributions

R.Z. and K.L. conceived and designed the experiments. H.L., C.G., L.T., and H.W performed the experiments and R.Z. and D.C. analyzed the data. R.Z. drafted the manuscript and R.Z., D.C. and Y.C. revised the manuscript several times. All authors have read and approved the submitted version.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (2019RC112) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160324).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods in the study were performed in accordance with relevant institutional/ national / international guidelines. There is no restriction of collecting B. pilosa seeds for research purpose since it is not listed as protected species in China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rui Zhang and Dali Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Rui Zhang, Email: zhangrui@hainanu.edu.cn.

Kai Luo, Email: luok@hainanu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sun Y, Zhou Q, Wang L, et al. Cadmium tolerance and accumulation characteristics of Bidens pilosa L. as a potential Cd-hyperaccumulator. J Hazard Mater. 2009;161:808–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belimov AA, Hontzeas N, Safronova VI, et al. Cadmium-tolerant plant growth-promoting bacteria associated with the roots of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L. Czern.) Soil Biol Biochem. 2005;37:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.07.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaney R, Li YM, Brown SL, et al. Improving metal hyperaccumulator wild plants to develop commercial phytoextraction. Plant Soil. 1999;101:129–158. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garbisu C, Alkorta I. Phytoextraction: a cost-effective plant-based technology for the removal of metals from the environment. Bioresource Technol. 2001;77:229–236. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He S, He Z, Yang X, et al. Soil biogeochemistry, plant physiology, and phytoremediation of cadmium-contaminated soils. Adv Agron. 2015;134:135–225. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2015.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng LJ, Zou ZM. Growth regularity, seed propagation and control effect of Bidens pilosa. Southwest China J Agric Sci. 2012;25:1460–1463. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartolome AP, Villaseñor IM, Yang WC. Bidens pilosa L. (Asteraceae): botanical properties, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2:340215. doi: 10.1155/2013/340215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira FQ, Andrade-Neto V, Krettli AU, et al. New evidences of antimalarial activity of Bidens pilosa roots extract correlated with polyacetylene and flavonoids. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei S, Zhou Q. Screen of Chinese weed species for cadmium tolerance and accumulation characteristics. Int J Phytoremediat. 2008;10:584–597. doi: 10.1080/15226510802115174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu J, Bai Y, Coulman B, et al. Using thermal time models to predict seedling emergence of orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.) under alternating temperature regimes. Seed Sci Res. 2006;16:261–271. doi: 10.1017/SSR2006258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarado V, Bradford KJ. A hydrothermal time model explains the cardinal temperatures for seed germination. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:1061–1069. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00894.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baskin JM, Baskin CC. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. 2. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu XW, Fan Y, Baskin CC, et al. Comparison of the effects of temperature and water potential on seed germination of fabaceae species from desert and subalpine grassland. Am J Bot. 2015;102:649–660. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdellaoui R, Boughalleb F, Zayoud D, et al. Quantification of Retama raetam seed germination response to temperature and water potential using hydrothermal time concept. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;157:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakhshandeh E, Gholamhossieni M. Modelling the effects of water stress and temperature on seed germination of radish and cantaloupe. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38:1402–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00344-019-09942-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Zhao K, Li X, et al. Factors affecting seed germination and emergence of Aegilops tauschii. Weed Res. 2020;2020(60):171–181. doi: 10.1111/wre.12410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatri R, Sethi V, Kaushik A. Inter-population variations of Kochia indica during germination under different stresses. Ann Bot. 1991;67:413–415. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a088175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mira S, Arnal A, Pérez-García F. Habitat-correlated seed germination and morphology in populations of Phillyrea angustifolia L. (Oleaceae) Seed Sci Res. 2017;27:50–60. doi: 10.1017/S0960258517000034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, Wang S, Wei X, et al. Sensitivity of seed germination to temperature of a relict tree species from different origins along latitudinal and altitudinal gradients: implications for response to climate change. Trees. 2019;33:1435–1445. doi: 10.1007/s00468-019-01871-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Q, Li C. Germination characteristics of Cakile edentula (Brassicaceae) seeds from two different climate zones. Environ Exp Bot. 2020;180:104268. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donohue K, Rubio de Casas R, Burghardt L, et al. Germination, postgermination adaptation, and species ecological ranges. Annu Rev Eco Evol S. 2010;41:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gratani L. Plant phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental factors. Adv Bot. 2014;2014:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2014/208747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Xu D, Yang Z, et al. Geographic variations in seed germination of Dalbergia odorifera T. Chen in response to temperature. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;102:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valencia-Gredilla F, Supiciche ML, Chantre GR, et al. Germination behaviour of Conyza bonariensis to constant and alternating temperatures across different populations. Ann Appl Biol. 2020;176:36–46. doi: 10.1111/aab.12556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horn KJ, Nettles R, Clair S. Germination response to temperature and moisture to predict distributions of the invasive grass red brome and wildfire. Biol Invasions. 2015;17:1849–1857. doi: 10.1007/s10530-015-0841-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orsenigo S, Guzzon F, Abeli T, et al. Comparative germination responses to water potential across different populations of Aegilops geniculata and cultivar varieties of Triticum durum and Triticum aestivum. Plant Biol. 2017;19:165–171. doi: 10.1111/plb.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mobli A, Mijani S, Ghanbari A, et al. Seed germination and emergence of two flax-leaf alyssum (Alyssum linifolium Steph. ex. Willd.) populations in response to environmental factors. Crop Pasture Sci. 2019;70:807–813. doi: 10.1071/CP19162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dürr C, Dickie JB, Yang XY, et al. Ranges of critical temperature and water potential values for the germination of species worldwide: contribution to a seed trait database. Agr Forest Meteorol. 2015;200:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2014.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bidgoly RO, Balouchi H, Soltani E, et al. Effect of temperature and water potential on Carthamus tinctorius L. seed germination: quantification of the cardinal temperatures and modeling using hydrothermal time. Ind Crops Pro. 2018;113:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Onofri A, Benincasa P, Mesgaran MB, et al. Hydrothermal-time-to-event models for seed germination. Eur J Agron. 2018;101:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2018.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakhshandeh E, Jamali M. Population-based threshold models: a reliable tool for describing aged seeds response of rapeseed under salinity and water stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2020;176:104077. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang R, Luo K, Chen DL, et al. Comparison of thermal and hydrotime requirements for seed germination of seven Stipa species from cool and warm habitats. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:560714. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.560714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanehkoori FH, Pirdashti H, Bakhshandeh E. Quantifying water stress and temperature effects on camelina (Camelina sativa L.) seed germination. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;186:104450. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaferanieh M, Mahdavi B, Torabi B. Effect of temperature and water potential on Alyssum homolocarpum seed germination: quantification of the cardinal temperatures and using hydro thermal time. S Afr J Bot. 2020;131:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiang YM, Chuang DY, Wang SY, et al. Metabolite profiling and chemopreventive bioactivity of plant extracts from Bidens pilosa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;95:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramabulana AT, Steenkamp PA, Madala NE, et al. Profiling of altered metabolomic states in Bidens pilosa leaves in response to treatment by methyl jasmonate and methyl salicylate. Plants. 2020;9:1275. doi: 10.3390/plants9101275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung HH, Ting HM, Wang WH, et al. Elucidation of enzymes involved in the biosynthetic pathway of bioactive polyacetylenes in Bidens pilosa using integrated omics approaches. J Exp Bot. 2021;72:525–541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dai H, Wei S, Twardowska I, et al. Hyperaccumulating potential of Bidens pilosa L. for Cd and elucidation of its translocation behavior based on cell membrane permeability. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:23161–23167. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui QG, He WM. Soil biota, but not soil nutrients, facilitate the invasion of Bidens pilosa relative to a native species Saussurea deltoidea. Weed Res. 2009;49:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3180.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitaker C, Beckett RP, Minibayeva FV, et al. Alleviation of dormancy by reactive oxygen species in Bidens pilosa L. seeds. S Afr J Bot. 2010;76:601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2010.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy KN, Singh M. Germination and emergence of hairy beggarticks (Bidens pilosa) Weed Scie. 1992;40:195–199. doi: 10.1017/S0043174500057210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan WB, Quan GM, Zhang JE, et al. Effects of environmental factors on seed germination of Bidens pilosa and Bidens bipinnata. Ecol Environ. 2013;22:1129–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chauhan BS, Ali HH, Florentine S. Seed germination ecology of Bidens pilosa and its implications for weed management. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52620-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo YT, Wang ZM, Cui XL, et al. The reproductive traits and invasiveness of Bidens pilosa var. radiata. Chin J Ecol. 2019;38:655–662. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou CJ. Effects of water and salt stress on seed germination of Bidens pilosa L. var. radiata Sch from different source. Seed Nursery (Taiwan) 2000;2:119–134. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang HL, Huang YL, Wu TC, et al. Phenotypic variation and germination behavior between two altitudinal population of two varieties of Bidens pilosa in Taiwan. Taiwania. 2015;60:194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan SS, Xiao XY, Guo ZH. Regional distribution of cadmium minerals and risk assessment for potential cadmium pollution of soil in China. Environ Pollut Cont. 2012;6(51–56):100. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue MF, Feng L, Cui Y, et al. Prediction of the potential distribution and suitability analysis of the invasive weed, Bidens alba (L.) DC. Journal of Biosaf. 2016;25:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen YT, Ma Liang, Lu TY, et al. Identification of Bidens weedy taxa of Bidens in China. J Changshu Institute Technol (Natural Sciences). 2021;35:3587–91.

- 50.Saberali SF, Shirmohamadi-Aliakbarkhani Z. Quantifying seed germination response of melon (Cucumis melo L.) to temperature and water potential: thermal time, hydrotime and hydrothermal time models. S Afr J Bot. 2020;130:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2019.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gummerson RJ. The effect of constant temperatures and osmotic potentials on the germination of sugar beet. J Exp Bot. 1986;37:729–741. doi: 10.1093/jxb/37.6.729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kebreab E, Murdoch AJ. Modelling the effects of water stress and temperature on germination rate of Orobanche aegyptiaca seeds. J Exp Bot. 1999;334:655–664. doi: 10.1093/jxb/50.334.655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soltani E, Baskin CC, Baskin JM, et al. A quantitative analysis of seed dormancy and germination in the winter annual weed Sinapis arvensis (Brassicaceae) Botany. 2016;94:289–300. doi: 10.1139/cjb-2015-0166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer SE, McArthur DE, Jorgensen GL. Variation in germination response to temperature in rubber rabbitbrush (chrysothamnus-nauseosus, asteraceae) and its ecological implications. Am J Bot. 1989;76:981–991. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1989.tb15078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abe T, Matsunaga M. Geographic variation in germination traits in Melia azedarach and Rhaphiolepis umbellata. Am J Plant Sci. 2011;2:52–55. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2011.21007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venier P, Ferreras AE, Verga A, et al. Germination traits of Prosopis alba from different provenances. Seed Sci Technol. 2015;43:548–553. doi: 10.15258/sst.2015.43.3.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zettlemoyer MA, Prendeville HR, Galloway LF. The effect of a latitudinal temperature gradient on germination patterns. Int J Plant Sci. 2017;178:673–679. doi: 10.1086/694185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giménez-Benavides L, Escudero A, Pérez-García F. Seed germination of high mountain Mediterranean species: altitudinal, interpopulation and interannual variability. Ecol Res. 2005;20:433–444. doi: 10.1007/s11284-005-0059-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cochrane A, Hoyle GL, Yates CJ, et al. Predicting the impact of increasing temperatures on seed germination among populations of western Australian Banksia (Proteaceae) Seed Sci Res. 2014;24:195–205. doi: 10.1017/S096025851400018X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barros RTD, Martins CC, Silva GZD, et al. Origin and temperature on the germination of beggartick seeds. Rev Bras Eng Agr Amb. 2017;21:448–453. doi: 10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v21n7p448-453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larsen SU, Bailly C, Côme D, et al. Use of the hydrothermal time model to analyse interacting effects of water and temperature on germination of three grass species. Seed Sci Res. 2004;14:35–50. doi: 10.1079/SSR2003153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mesgaran MB, Onofri A, Mashhadi HR, et al. Water availability shifts the optimal temperatures for seed germination: a modelling approach. Ecol Model. 2017;351:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.02.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hammami H, Saadatian B, Hosseini SAH. Geographical variation in seed germination and biochemical response of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) ecotypes exposed to osmotic and salinity stresses. Ind Crop Prod. 2020;152:112507. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicotra AB, Atkin OK, Bonser SP, et al. Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernareggi G, Carbognani M, Petraglia A, et al. Climate warming could increase seed longevity of alpine snowbed plants. Alpine Bot. 2015;125:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00035-015-0156-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowse H, Finch-Savage W. Hydrothermal threshold models can describe the germination response of carrot (Daucus carota) and onion (Allium cepa) seed populations across both sub-and supra-optimal temperatures. New Phytol. 2003;158:101–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00707.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bakhshandeh E, Pirdashti H, Vahabinia F, et al. Quantification of the effect of environmental factors on seed germination and seedling growth of Eruca (Eruca sativa) using mathematical models. J Plant Growth Regul. 2020;39:190–204. doi: 10.1007/s00344-019-09974-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gareca EE, Vandelook F, Fernández M, et al. Seed germination, hydrothermal time models and the effects of global warming on a threatened high Andean tree species. Seed Sci Res. 2012;22:287–298. doi: 10.1017/S0960258512000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bakhshandeh E, Atashi S, Hafeznia M, et al. Hydrothermal time analysis of watermelon (Citrullus vulgaris cv. ‘Crimson sweet’) seed germination. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015;37:1738–1846. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1738-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharma ML. Interaction of water potential and temperature effects on germination of three semi-arid plant species. Agron J. 1976;68:428–429. doi: 10.2134/agronj1976.00021962006800020048x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu S, Bradford KJ, Huang Z, et al. Hydrothermal sensitivities of seed populations underlie fluctuations of dormancy states in an annual plant community. Ecology. 2020;101:e02958. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Joosen RVL, Kodde J, Willems LAJ, et al. GERMINATOR: a software package for high-throughput scoring and curve fitting of Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2010;62:148–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bradford KJ. Applications of hydrothermal time to quantifying and modeling seed germination and dormancy. Weed Sci. 2002;50:248–260. doi: 10.1614/0043-1745(2002)050[0248:AOHTTQ]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.