Abstract

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) is a rare condition that refers to a spectrum of noninfectious lesions of cardiac valves that is most commonly seen in advanced malignancy. We describe a case report of a 63-year-old male with NBTE and multiple embolizations (encephalic, coronary, splenic, and renal). The patient was admitted to the emergency department for stroke. During hospitalization, the patient complained of left leg pain and a venous echo color Doppler of the lower limbs was performed, showing bilateral distal deep-vein thrombosis. A thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan, which was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism, revealed a primary lung cancer and subcarinal lymphadenopathy. As collateral findings, multiple ischemic lesions in the spleen and in both kidneys were identified. In addition, areas of subendocardial hypodensity compatible with ischemia were also highlighted. An electrocardiogram showed acute myocardial infarction and focused echocardiographic evaluation displayed hypokinesis of the lateral and posterior in the mid- and distal segments and aortic and mitral valve vegetations, confirmed by a transesophageal echocardiography. Empiric antimicrobial therapy was started; all blood culture sets were negative and the patient was apyretic throughout the hospitalization. These findings supported the hypothesis of NBTE with multiple embolizations during a hypercoagulable state associated with advanced lung cancer.

Keywords: Marantic endocarditis, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, transesophageal echocardiography, valvular heart disease, valvular regurgitation

INTRODUCTION

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) is an uncommon condition that could affect patients with chronic debilitating disease, characterized by the deposition of thrombi on previously undamaged heart valves (most commonly left-side heart valves) in the absence of a systemic infection, and by the increased risk of arterial embolic events.[1] The pathogenesis causing NBTE is complex and multifactorial, and involves endothelial cell injury in the context of a hypercoagulable state.[2] NBTE represents a diagnosis of exclusion and requires a high degree of suspicion. Treatment of NBTE usually consists of treating the underlying disease while managing the risk for systemic embolization.[2]

CASE REPORT

We describe the case report of a 63-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with left deviation of the oral rhyme, dysarthria, and left hemiparesis. In the days preceding the hospitalization, the patient experienced walking impairment. A brain computed tomography (CT) showed multiple ischemic lesions (blurred hypodense areas with localization predominantly frontoparietal, insular, and right temporo-occipital) [Supplementary Figure 1 (18.9KB, jpg) ], attributable to a synchronous subacute ischemic vascular event and suspected hemorrhagic adenoma near the left optic tract, confirmed on cerebral magnetic resonance imaging performed the next day. He was then admitted to the neurology clinic of our hospital.

His vital signs on examination and significant laboratory results were as follows: temperature 36.5°C, blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, heart rate 70 beats/min, normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin 11 gr/dl), thrombocytopenia (58,000/μl), and high level of C-reactive protein (15 mg/dL). The patient complained of left leg pain. A venous echo color Doppler of the lower limbs was performed, showing bilateral distal deep-vein thrombosis. A thoracoabdominal CT scan, which was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism (showing no defects within the pulmonary vasculature), revealed a 35 mm × 33 mm × 36 mm lesion in the lower right lung lobe consistent with primary lung cancer, characterized by scissor crossing, extension to the pleura, and concomitant hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy [Supplementary Figure 2 (21.1KB, jpg) ]. A removable inferior vena cava filter was then placed. As collateral findings, multiple ischemic lesions in the spleen and in both kidneys were identified [Supplementary Figures 3 (21.1KB, jpg) and 4 (19.8KB, jpg) ]; in addition, areas of subendocardial hypodensity in the lateral wall, septum, and papillary muscles compatible with ischemia were also highlighted [Supplementary Figure 5 (21.8KB, jpg) ].

The patient denied chest pain; an electrocardiogram showed posterolateral ST elevation with negative T-wave and pathological posterolateral Q-waves, suggesting an acute myocardial infarction. Focused echocardiographic evaluation displayed hypokinesis of the lateral and posterior in the mid-and distal segments, with ejection fraction of about 45% by qualitative visual inspection. The patient was therefore transferred to our cardiology department.

Due to the suspected intracranial hemorrhagic lesion with concomitant severe thrombocytopenia (minimum value during hospitalization 20,000/μl, which contraindicated antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy), a conservative approach strategy was taken. High-sensitivity troponin I was elevated, showing rise and fall trend on serial testing (peak concentration 8366 ng/L).

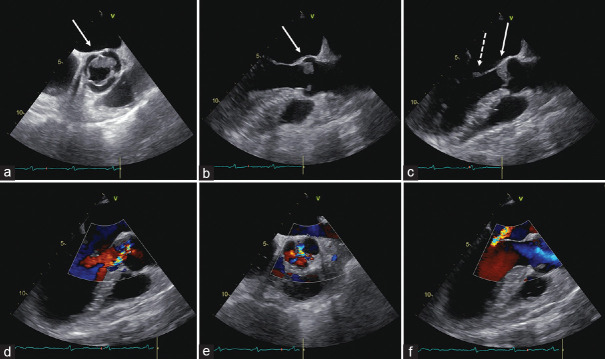

Aortic [Figure 1a–f] and mitral [Figure 1c] valve vegetations were highlighted by transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE); therefore, four sets of blood cultures and direct-from-blood fungal pathogen detection assay were drawn. Empiric antimicrobial therapy with daptomycin and ceftriaxone was then started.

Figure 1.

Transesophageal echocardiogram. Midesophageal views at 49° (a) and 118° (b, systole; c, diastole) showing a low-isoechoic mass attached to the midportion and to free margins of the aortic cusps (white solid arrows). Aortic masses appeared low-isoechoic, with smooth margins, and homogeneous internal structure. The mitral vegetation on the anterior leaflet is indicated by the white dashed arrow (c). Midesophageal views at 134° (d) and 38° (e) showing eccentric moderate aortic regurgitation. Midesophageal views at 134° (f) moderate mitral regurgitation (central jet)

Voluminous aortic vegetations were visualized by TEE, located at the ventricular side of the midportion and on free margins of the cusps, [Figure 1a–c]. Aortic masses appeared low-isoechoic, with relatively smooth margins, and homogeneous internal structure. Furthermore, a mitral vegetation was located at the coaptation zone of the anterior leaflet [Figure 1c]. Moderate aortic (eccentric, directed toward the interventricular septum) and moderate mitral (central jet) regurgitations were highlighted [Figure 1d and f, respectively].

All blood culture sets were negative; the basic coagulation workup showed low fibrinogen concentrations (42 mg/dl), and high D-dimer levels (2450 μg/mL), consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Those findings, together with (i) the absence of fever for the entire hospitalization, (ii) the presence of metastatic lung cancer, and (iii) concomitant bilateral deep-vein thrombosis, supported the hypothesis of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), with multiple embolizations (encephalic, coronary, splenic, and renal), during a hypercoagulable state associated with advanced stage of lung cancer. A progressive deterioration of the clinical condition occurred, with respiratory and hemodynamic instability leading to death on day 3 of hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

NBTE, formerly known as marantic endocarditis and first described by Ziegler in 1888, is a well-known entity due to a state of hypercoagulability, often correlated with malignancy.[1] It is found in 4% of terminal cancer patients but its autopsy prevalence increases to 32% if a history of cerebral ischemia is present.[2] The etiology of the hypercoagulable state in cancer is multifactorial;[1] contributing factors include procoagulant alterations associated with the malignancy and the host's inflammatory response.

NBTE is characterized by the deposition of thrombi on previously undamaged heart valves in the absence of a bloodstream bacterial infection and by the increased frequency of arterial embolic events in patients with state of chronic debilitating diseases. The most commonly affected valves are the left-sided heart valves (the aortic valve, mitral valve, and combination of both the aortic and mitral valves, in descending order of frequency). Involvement of right-sided valves and chordae tendinae have also been described although it is less frequent.[3]

Vegetations are typically present on the atrial surface of the mitral and tricuspid valves and the ventricular surface of the aortic and pulmonic valves; those lesions characteristically occur at the leaflet's free edges, and they are usually described as follows: rounded, sessile, heterogeneous in shape, and >3 mm when visualized on echocardiography. As compared to the lesions encountered in infective endocarditis (IE), NBTE vegetations are always sterile, more friable, and prone to systemic embolization.[2] Systemic emboli usually are the cause of presenting symptoms; cerebral, coronary, renal, and mesenteric circulations are the vascular territories most frequently affected.[1] Lung, pancreas, gastric cancer, and adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site are the most common cancer type associated with NBTE.[1]

As compared to IE, diagnosis of NBTE is more elusive. TEE is thought to be more sensitive in detecting valvular vegetations than transthoracic echocardiography,[1] and represents the preferred diagnostic tool for this disease entity; when a diagnosis of IE is suspected, but (i) blood cultures and serology are negative, (ii) response to antibiotic treatment is lacking, and (iii) a concomitant state of hypercoagulability is present, then NBTE should be strongly considered.

Treatment of NBTE usually consists of systemic anticoagulation and treatment of the underlying disease.[4] The prognosis is extremely poor.[3]

Declaration of patient consen

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Brain computed tomography scan showing multiple ischemic lesions

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: lesion in the lower right lung lobe consistent with primary lung cancer

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: ischemic lesions in the spleen

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: renal ischemic lesions

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: Areas of subendocardial hypodensity in the lateral wall, septum, and papillary muscles compatible with ischemia

REFERENCES

- 1.el-Shami K, Griffiths E, Streiff M. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in cancer patients: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Oncologist. 2007;12:518–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-5-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J, Frishman WH. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Cardiol Rev. 2016;24:244–7. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee MH, Tsai WC, Su HM, Hsu PC. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in multiple heart valves. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2020;36:220–1. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazokopakis EE, Syros PK, Starakis IK. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (marantic endocarditis) in cancer patients. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;10:84–6. doi: 10.2174/187152910791292484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Brain computed tomography scan showing multiple ischemic lesions

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: lesion in the lower right lung lobe consistent with primary lung cancer

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: ischemic lesions in the spleen

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: renal ischemic lesions

Thoracoabdominal computed tomography scan: Areas of subendocardial hypodensity in the lateral wall, septum, and papillary muscles compatible with ischemia