Abstract

There is widespread debate on the drivers of heterogeneity of adverse COVID-19 pandemic outcomes and, more specifically, on the role played by context-specific factors. We contribute to this literature by testing the role of environmental factors as measured by environmentally protected areas. We test our research hypothesis by showing that the difference between the number of daily deaths per 1,000 inhabitants in 2020 and the 2018–19 average during the pandemic period is significantly lower in Italian municipalities located in environmentally protected areas such as national parks, regional parks, or Environmentally Protected Zones. After controlling for fixed effects and various concurring factors, municipalities with higher share of environmentally protected areas show significantly lower mortality during the pandemic than municipalities that do not benefit from such environmental amenities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mortality, Protected areas, Pollution

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a major, partially unexpected, world shock that is leading to reformulate expectations and strategies of private and public actors. The pandemic has made clear the urgent need of reducing vulnerability to such health risks in the future. This goal has stimulated research to identify drivers of adverse outcomes of the pandemic spread (i.e., contagions, deceases) in order to devise proper policies aimed to reduce the impacts of the shock.

The scientific debate around the drivers of the COVID-19 epidemics reflected formation and school of thoughts of (social and natural) scientists working in different domains. On the one side, we can think to an extreme benchmark model where geographical heterogeneity in contagions and deceases only depends on the dynamics of viral circulation (i.e., location of epidemic outbreaks, circulation, and interaction among people before and after lockdown measures). On the other side, we can argue that, beyond these base ingredients, other socio-demographic and environmental factors matter and contribute to explain the stark variation in adverse epidemic outcomes across regions and countries, even those close to each other.

Our paper aims to contribute to this debate by formulating and testing a research hypothesis on the role of environmental factors. More specifically, we investigate whether living in a municipality that belongs to an environmentally protected area makes inhabitants less vulnerable to COVID-19. To this purpose, we adopt a quasi-experimental approach drawing on an ex-ante formulated definition of environmental quality of Italian municipalities, i.e., the share of their surface occupied by protected areas, which is exogenous to the circumstances of the COVID-19 epidemics. To test our research hypothesis, we exploit three different park-municipality definitions: any protected areas (i.e., regional parks, national parks, and Environmental Economic Zones, EEZ henceforth), national parks only, and EEZ only (see Section 4 for details). Protected areas in Italy are classified into national parks, regional natural parks, and natural reserves, as regulated by the Law no. 394 of 6 December 1991. The decision is taken by the President of the Italian Republic based on the proposal of the Ministry of the Environment (now officially named Ministry of the Ecological Transition) after consultations with the interested regional authorities. According to this law, parks are constituted by land, river, or sea areas containing highly relevant natural areas or landscapes. Their objective is to preserve the ecological equilibrium, apply management and conservation tool for a natural human-environment relationship, promote educational and research activities, and preserve hydro-geological equilibrium.

Our findings show that park municipalities display a significantly lower daily difference of deaths per capita during the period of the COVID-19 epidemics with respect to the average of the same period in the two previous years. Results persist when we control for municipality fixed effects and show that park municipalities exhibit a more favorable dynamics of daily deaths per capita than non-park municipalities.

Our findings contribute to different research fields by showing that park areas play an important positive role in health outcomes also in the specific context of a pandemic, and that environmental factors matter for the geographical spread of the disease. In terms of policy implications, our paper suggests that measures ranging from reforestation to urban green policies and enhancement of preservation of natural areas can, at the same time, reduce exposure to environmental as well as pandemic risk. In addition, EEZ benefit from incentives for environmentally sustainable innovation and economic activities. The approach of policies like this, in view of our findings and in the logic of circular economy, can reconcile creation of economic value, environmental quality, and health.

This article is divided into seven sections, including introduction and conclusion. In the second section we provide a review of the literature to whom the paper contributes. In the third section we outline our research hypothesis. In the fourth section we describe data and methods. In the fifth section we present our empirical findings. In the sixth section we discuss our results and the seventh section concludes.

2. Literature review

Our paper aims to contribute to different strands of the literature. The first relates to the effect of parks and, more in general, green areas – including those in urban settings – on health. Overall, there is a common agreement that people in contact with nature reveal better health conditions (see, for instance, [1]). Nature contacts have both psychological benefits as well as immunologic, social, and environmental benefits [1]. More specifically, national parks provide opportunities to increase rigorous physical activity, thereby reducing obesity. The connection with cleaner natural environment reduces pollution with positive effects on health and generates lower levels of stress, improving as well mental health. Several studies show that living close to parks and other recreation facilities is consistently related to higher physical activity levels, improving physical but also mental health [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. More recently, natural sounds have been proven to be a positive source for both mental health as well as other health outcomes such as heart rate, blood pressure, perceived pain, skin conductance, cortisol, and t-wave amplitude [8].

Our study also speaks to the recent literature that analyses the socioeconomic determinants of COVID-19 outcomes, such as lockdown measures, human mobility, economic activities, and environmental conditions. In the United States, Greenstone and Nigam [9] estimate that the physical distance and confinement policies, that are broadly defined as the policies aiming at “keeping people apart from each other by confining them to their homes in order to reduce contact rates”, might have saved 1.7 million lives. In China, Fang et al. [10] have found that without the restrictions on human mobility the number of cases might have been approximately 65% higher, excluding Hubei province, the region of Wuhan, where the first COVID-19 cases were detected. In Italy, a number of authors have investigated the socioeconomic determinants of the heterogeneous spread of the virus. For examples, Becchetti et al. [11] and Gatto et al. [12] analyze the role of lockdown measures, Liotta et al. [13] the role of social connectedness among the elderly, Alacevich et al. [14] and Perone [15] the role of demography and the health care sector, and Becchetti et al. [16] and Perone [15] the role of environmental factors.

More specifically on outdoor pollution, Krupnik et al. [17] demonstrate that air quality improvement leads to significant health benefits in many Central and Eastern Europe countries. In the same direction, Pope and Dockery [18] conduct a literature survey, discuss empirical findings, and conclude that long term exposure to particulate matter increases the likelihood of inflammatory responses to respiratory diseases. The Forum of International Respiratory Societies Environmental Committee provides an updated survey on empirical research documenting the effect of air pollution on respiratory diseases and life expectancy over the world [19]. Since the COVID-19 virus has been found responsible of respiratory and pulmonary diseases, several papers have tested whether particulate matter has worsened patient reaction to the virus consistently with predictions from this literature. In this respect, Wu et al. [20] find a significant and positive nexus for US council, and Becchetti et al. [11] found similar results for Italian provinces.

3. Research hypothesis

The null hypothesis of the current study is that environmental factors do not matter and geographical heterogeneity of COVID-19 outcomes depends only on the dynamics of viral circulation, e.g., location of epidemic outbreaks, circulation, and interaction among people before and after the lockdown measures. If this is the case, environmental factors should not matter after controlling for these factors.

The reasons to believe in the alternative hypothesis – i.e., municipalities containing environmentally protected areas have a significantly lower share of COVID-19 deaths – are explained in the literature review summarised in the introduction, which we sketch here in three points: (i) the virus infection can cause (mainly, but not only) respiratory and pulmonary diseases; (ii) long-term exposure to particulate matter – as captured by the PM10 and PM2.5 particulate measures and other pollutants such as nitrogen bioxide (NO2) – weaken lungs and alveolus response to respiratory and pulmonary viruses, thereby increasing the likelihood of inflammatory responses and adverse outcomes in presence of such viruses [18]; (iii) the COVID-19 generates mainly more negative outcomes in terms of respiratory and pulmonary diseases in areas with higher pollution such as those without national parks and/or preservation of natural resources [16].

Our maintained hypothesis is that a share of municipality geographical area located in national parks makes their environment cleaner and people less exposed to pollutants. This is because, as the literature observes that urban green contributes to better air quality [[21], [22], [23], [24]], and natural parks display better air quality [25], it is reasonable to assume that the air quality is much better when a sizeable portion of a municipality lies within a natural park.

The environmental variable we use as our key explanatory variable relates to three different classifications of Italian municipalities as “green municipalities”: natural parks, regional parks, and EEZ (see the introduction and Section 4 for further details).

Using protected areas as a proxy for air quality has two advantages. First, data on pollutants cannot be disaggregated at municipality level without measurement errors due to the limited number of pollution monitoring devices. These errors may occur as monitoring stations are located in close proximity to major roads, in industrial areas, or where pollution levels are representative of the average exposure of the general population, and their number depends on the population density of the area (for more details about criteria, see https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/air/air-quality-concentrations/classification-of-monitoring-stations-and). Second, our measure is highly policy relevant since the establishment of protected areas like natural parks responds to environmental policy goals. In fact, the increase of protected, green areas has positive effects on biodiversity, air quality, carbon dioxide emissions abatement, and constraints in terms of land use and building areas. In this respect, our research hypothesis indirectly assesses the additional benefits that may arise from the implementation of such policies, specifically in terms of reduced exposure to pandemic risks and their adverse health and economic outcomes.

4. Data and methods

Our main dependent variable is the difference between the number of daily deaths per 1000 inhabitants in 2020 and the 2018–19 average at municipality level. Data on deaths from civil register offices has been released by the Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT) and cover a representative sample of 87% Italian municipalities (for a methodological note, see https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/05/Rapporto_Istat_ISS.pdf). For deaths in 2020, the sample period considered in our data goes from February 24th, 2020 to April 15th, 2020 (the last day for which ISTAT data on deaths by municipality was available).

The deaths difference between the COVID-19 year and the average of the two previous years has been increasingly used to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on mortality (see, for instance, [26]) and is preferred to the use of deaths officially attributed to COVID-19 for several reasons. First, the latter exists only at provincial level and is highly incomplete. Second, COVID-19 deaths strongly depend on certification polices that may vary across countries and regions within the same country. Under the most restrictive approach, COVID-19 deaths are only those of patients who directly died because of COVID-19. Under a less restrictive approach, COVID-19 deaths include those of patients that died with COVID-19. Even though the difference is not so clear-cut since an exact distinction would require knowledge of the counterfactual (i.e., would the patient already having serious pathologies have stayed alive without COVID-19), differences across regions can be substantial.

Further differences can arise also according to the phases of the epidemic. During the first wave (i.e., from the first cases detected in February 2020 to the ease of the first lockdown measures in June 2020) and in regions where health care centers and intensive care units were saturated, it is likely that many COVID-19 deaths occurred at home and were misreported as non-COVID-19 deaths [27]. This may be due to health authorities strongly advising people without severe symptoms to stay home and avoid further congestions for the national health system, as was the case for non-COVID-19 illnesses [28]. Also, the scarcity of tests in some regions during the first wave exacerbated this scenario [29]. As a result, this approach is likely to have caused several COVID-19 home deaths misclassified as non-COVID-19 deaths, due to people who have not timely presented to the hospital and been able to be tested.

Another advantage of considering overall excess mortality is that it includes also indirect COVID-19 effects since during the epidemics there has been reduced attention toward other pathologies, also because of patients’ fear of access to hospital and other health care facilities. In fact, during the first wave in Italy, for non-COVID-19 patients emergency department visits and hospitalisations decreased and out-of-hospital deaths increased [30]. However, this measure records deaths from civil register offices and, as such, it captures residents of each municipality that have died, regardless of where the death occurred. This may represent a limitation if a significant number of people died out of their municipality of residence, an unlikely event given the lockdown measures and the hospital congestions. Our preferred measure for the COVID-19 spread is the number of deaths rather than other measures of contagion for several reasons. First, contagions are not recorded officially at municipality level. Second, they are recorded at province and regional level, but the measurement error is likely to be severe conditional to the intensity of the epidemic. As mentioned above, the guidelines followed by the different Italian Regional Health Systems, especially in the days of epidemic peak, varied markedly and in most cases tended to delay tests in order to avoid hospital congestion [31]. For this reason, testing was taken into account only in presence of several days of fever above 37.5 °C. In many cases it arrived several days later. Many people who recovered from COVID-19 and cleared the virus (or, unfortunately, died) did not take a proper test.

To define whether a municipality lies in a protected area, we use three different definitions of protected areas. First, based on 2020 data from the Italian Ministry of the Environment and Protection of Land and Sea and processed by Ancitel – the Italian Municipality Network public company, we select 2073 municipalities within any protected natural areas - that is, municipalities with areas that are part of national, regional, provincial, or local parks, natural reserves, and sea natural areas. Second, we consider only municipalities within national parks (502 municipalities). Third, we consider municipalities with at least 45% of their surface area in parks, reserves, or naturally protected areas (251 municipalities). The latter were defined as EEZ by a 2019 decree-law (converted, with amendments, by Law 12 December 2019, n.141), with the government delivering forms of support to new or incumbent enterprises engaging in environmentally friendly programs or investments in these municipalities.

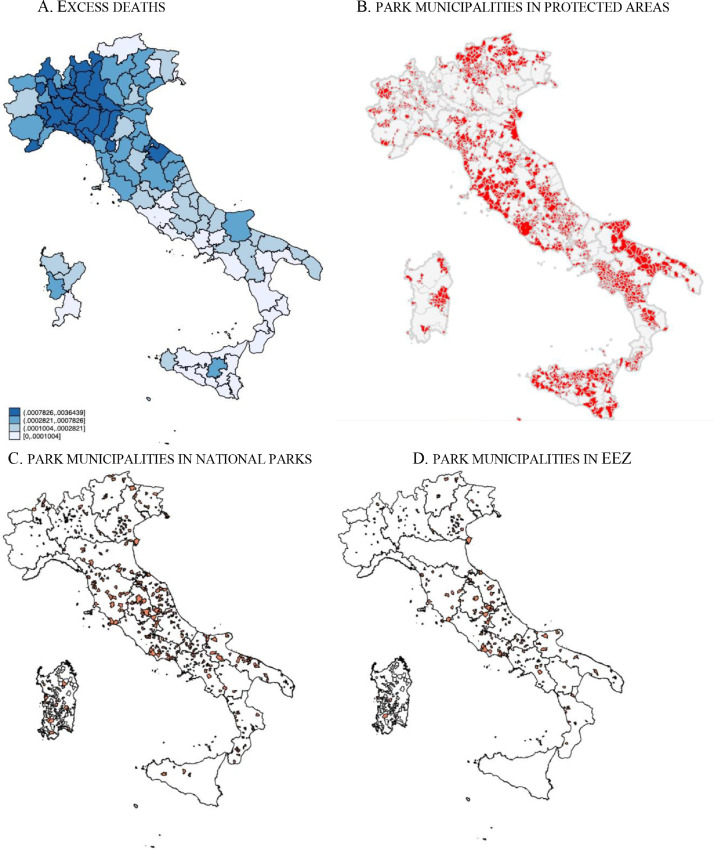

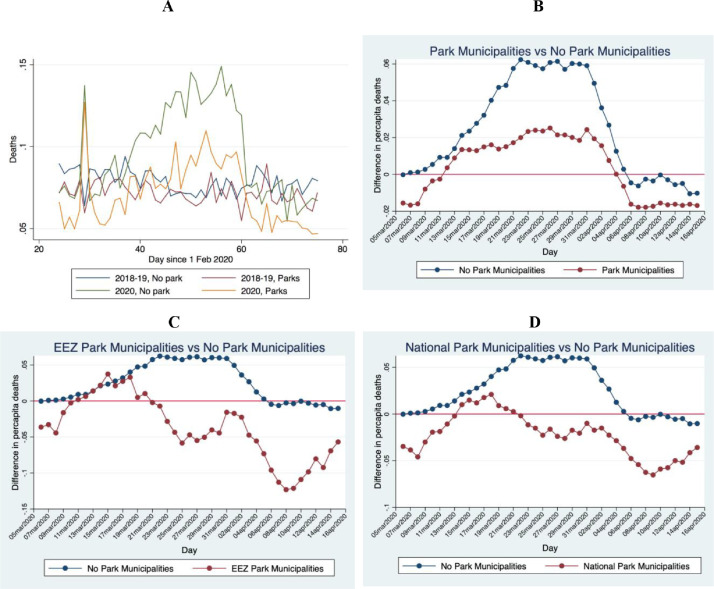

Italian maps describing the intensity of per capita deaths and the park municipality areas (Fig. 1 A-D) show that park municipalities cover a non-negligible share of the total Italian municipalities: around 29% have at least a small portion located into a naturally protected area (the first wider definition), 5.6% have a portion in national parks, and 2.6% have no less than 45% of their surface into a naturally protected area (variables legend and detailed descriptive statistics are provided in Tables A1-A4 in the Appendix). Regional characteristics of our sample are shown in Table A3. As it is well known, Italy displays high geographical heterogeneity that will be accounted for in our analysis using fixed effects (i.e., capturing time invariant local heterogeneity) and subsample estimates for limited and more homogeneous geographical areas such as Northern regions. These preliminary descriptive findings at regional level also show that human interactions do not appear to be a main driver of COVID-19 excess deaths since the region having by far the higher population density (i.e., Campania) is also one with the best performance on excess deaths that are concentrated in the Northern regions. These figures also show that park municipalities are located where per capita deaths are lower. More specifically, the areas where per capita deaths are higher, i.e., the North-West and some other provinces in the rest of the country (Fig. 1A), display no or a very few number of municipalities located in protected areas (Fig. 1B). The 2018–19 average share of deaths is 7.5 per 1000 inhabitants against 8.9 in 2020. This implies 1.4 deaths more per 1000 inhabitants corresponding to 18.7% yearly increase. If we examine the same phenomenon across park and non-park municipalities, we find that the change is close to 0 for the wider park municipality areas and even negative for the national park and the EEZ areas (between −3 and −2 deaths per 1000 inhabitants) (Fig. A1A–A1C in the Appendix). The dynamics of daily per capita deaths over the epidemic period confirm that in 2018–19 deaths in non-park municipality areas are higher than in park municipality areas, and that in 2020 both trends increase during the epidemic period and their difference becomes much larger (Fig. 2 A–D).

Fig. 1.

A-1.D: geographical distribution of excess deaths and park municipalities, legend: A: geographical distribution of excess deaths, i.e., the difference between the number of daily deceases per 1000 inhabitants in 2020 and the 2018–19 average at municipality level; B: municipalities in protected areas (both regional and national parks); C: municipalities in national parks; D: municipalities in EEZ.

Fig. 2.

A-2.D: Dynamics of the one-year difference in daily deaths per 100,000 inhabitants between park and non-park municipalities, Legend: A: Daily deaths between park and non-park areas in 2018–19 and 2020; B: Deaths difference between all parks and non-park areas; C: Deaths difference between national park and non-park areas; D: Deaths difference between EEZ and non-park areas.

In order to control for concurring factors, we estimate the following pooled OLS specification:

| (1) |

where the dependent variable is the change in total deaths per 1000 inhabitants between day t in 2020 and the 2018–2019 average of total deaths in the corresponding day. Among regressors, DayTrend, DayTrend 2, and DayTrend 3 capture respectively the linear, the quadratic, and the cubic daily trend taking into account the non-linear dynamics of the epidemic; Parki is our main regressor of interest, i.e. a dummy equal to one if municipality i is defined as a park municipality (according to one of the three definitions explained above); Over65i is the number of municipality residents aged above 65, per 1000 inhabitants; Employeesi is the number of workers of any economic activity operating in the municipality, per 1000 inhabitants; Densityi is the population density in municipality i. Region dummies are included to control for all time invariant regional effects including, among others, differences in Regional Health Systems since Italian regions enjoy a high degree of autonomy with respect to healthcare policies. Standard errors are clustered at the province level to account for possible error correlation across municipalities within the same province.

5. Results

Municipality parks display a significantly lower number of deaths in both (2018–19 and 2020) observed periods, with the latter difference being almost double in absolute value (−0.026 vs. −0.015) in pooled estimates (Table 1 ). This difference is statistically significant, as confirmed by the same regression using as dependent variable the difference between the number of deaths in 2020 and the average number of deaths in 2018–2019 (Table 1, column 3). In terms of magnitude, over the entire population the difference would be 582 deaths less per day if all the country consisted of park municipalities. Among other regressors, the number of municipality residents aged above 65 is positively and significantly associated with a higher number of deaths, but it is not significant when we consider the deaths difference. Note that any trend or seasonality effect is captured by the DayTrend, DayTrend 2, and DayTrend 3 dummies. The significance of these variables suggests that the number of deaths and the difference observed between 2020 and the previous years have a non-linear trend.

Table 1.

Mortality in park municipalities (pooled OLS).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Deaths 2018–19 | Deaths 2020 | ΔDeaths |

| Park | −0.0145*** (0.00278) | −0.0260*** (0.00539) | −0.0116** (0.00473) |

| Over65 | 0.00104*** (7.58e-05) | 0.00108*** (0.000109) | 3.31e-05 (9.78e-05) |

| Density | −1.19e-05*** (3.99e-06) | −2.11e-05** (8.64e-06) | −9.10e-06* (5.22e-06) |

| Employees | −0.000101*** (1.54e-05) | −8.60e-05*** (1.88e-05) | 1.53e-05 (1.85e-05) |

| DayTrend | −0.000526 (0.00119) | 0.00286 (0.00377) | 0.00342 (0.00394) |

| DayTrend2 | −2.67e-06 (2.52e-05) | 4.04e-05 (6.70e-05) | 4.26e-05 (6.89e-05) |

| DayTrend3 | 7.69e-08 (1.71e-07) | −9.08e-07** (4.06e-07) | −9.83e-07** (4.12e-07) |

| Constant | −0.0844*** (0.0265) | −0.196** (0.0865) | −0.113 (0.0863) |

| Region dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 186,979 | 186,980 | 186,979 |

| R-squared | 0.075 | 0.056 | 0.017 |

Note: Pooled OLS model. Over65, and Employees are expressed per 1000 inhabitants. Standard errors are clustered at province level. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

We also examine the marginal role of national parks and EEZ (Table A5 in Appendix). The coefficient of park remains negative and statistically significant when controlling also for national parks and EEZ. The coefficient of national parks is also negative and statistically significant when we exclude municipality located in regional but not national parks.

Robustness checks

In order to control for unobserved time-invariant municipality-specific factors we run a fixed-effect panel OLS regression, where the role of the park-municipality effect is assessed by interacting park areas with time trend.

The equation we estimate is

| (2) |

where the Park variable is now interacted with the linear time trend. This specification allows us to test the differential effects of park areas on the trend in mortality changes. If is statistically different from zero, park municipalities have a different trend in the death difference with respect to non-park municipalities, net of unobserved time-invariant municipality-specific characteristics.

In Table A6 in Appendix we find that the best fixed effect model specification is that including the cubic trend variable and the interaction between the park and the trend variable. Estimate findings show that is negative and statistically significant for the EEZ (columns 3 and 5), implying that the dynamics of the daily deaths difference in park municipalities is significantly less severe than that in non-park municipalities (Table 2 ). This finding implies that, beyond the time-invariant effect of park municipalities on deaths that is absorbed into municipality fixed effects, the dynamics of the epidemic – driven, for instance, by factors such as location of epidemic outbreaks, circulation and interaction among people before and after lockdown measures – is significantly mitigated in park municipalities where the park area is larger.

Table 2.

Mortality and park municipalities (fixed effects).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | All | National & non-park | EEZ & non-park | |

| VARIABLES | ΔDeaths | ΔDeaths | ΔDeaths | ΔDeaths | ΔDeaths |

| DayTrend | 0.00147 (0.00378) | 0.00144 (0.00377) | 0.00129 (0.00376) | 0.00318 (0.00451) | 0.00302 (0.00468) |

| DayTrend2 | 9.34e-05 (5.96e-05) | 9.34e-05 (5.96e-05) | 9.41e-05 (5.95e-05) | 8.39e-05 (7.01e-05) | 8.61e-05 (7.32e-05) |

| DayTrend3 | −1.24e-06*** (3.64e-07) | −1.24e-06*** (3.64e-07) | −1.24e-06*** (3.63e-07) | −1.24e-06*** (4.24e-07) | −1.27e-06*** (4.41e-07) |

| Park # DayTrend | 2.43e-05 (0.000135) | 7.17e-05 (0.000121) | 0.000153 (0.000134) | ||

| National park # DayTrend | −0.000251 (0.000351) | −0.000121 (0.000371) | |||

| EEZ # DayTrend | −0.00174*** (0.000659) | −0.00148** (0.000659) | |||

| Over65 # DayTrend | 1.41e-06 (4.59e-06) | 1.49e-06 (4.58e-06) | 1.90e-06 (4.54e-06) | −4.28e-09 (5.30e-06) | 1.29e-07 (5.50e-06) |

| Density # DayTrend | −4.29e-09 (5.27e-08) | −7.50e-09 (5.32e-08) | −1.83e-08 (5.37e-08) | 1.91e-08 (5.67e-08) | 5.70e-09 (5.89e-08) |

| Employees # DayTrend | 7.35e-09 (7.01e-07) | −3.09e-09 (7.03e-07) | −1.91e-08 (7.01e-07) | −2.62e-07 (7.47e-07) | −1.09e-07 (7.55e-07) |

| Constant | −0.0661 (0.0616) | −0.0661 (0.0616) | −0.0657 (0.0615) | −0.0822 (0.0727) | −0.0823 (0.0761) |

| Observations | 186,979 | 186,979 | 186,979 | 143,380 | 137,208 |

| R-squared | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Number of municipalities | 7748 | 7748 | 7748 | 6203 | 5954 |

Note: Panel FE model. Over65, and Employees are expressed per 10,000 inhabitants. Standard errors are clustered at province level. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

As a robustness check, we test whether the significance of the park effect in pooled estimates is robust when we exclude big cities (Population ≥ 190,000 inhabitants), small villages (Population ≤ 1000 inhabitants) or when we estimate the subsample of small towns (1000 < Population ≤ 50,000) or small villages. In an additional robustness check, in line with Borri [32], we control for the number of employers or the number of firms in essential economic activities, as defined by the Prime Ministerial Decree of 25 March 2020 (the decree is available at https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/26/20A01877/sg; a full list of essential sectors is provided at the bottom of Table A8 in Appendix). These activities are the only activities that have not been halted during the national lockdown (i.e., 10 March—4 May 2020). The significance of the park variable is robust to all these checks (Tables A7-A8 in Appendix).

As a second robustness check we provide a further analysis focussing on the North-East and North-West regions where most municipalities are in the Po Valley. This geographical area has the characteristics of being, as climatologist use to say, a “room with only one window” due to its orographic conditions that border it with mountains on three of the four sides. Consequently, air tends to stagnate making the problem of particulate matter particularly severe as confirmed by 2020 data showing that the daily limit set by the World Health organisation (WHO) (50 μg/m3, not to be overcome than 35 times per year) has been overcome in 155 monitoring stations, 131 of them in Po Valley (Piedmont, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, and Friuli Venezia Giulia).

More specifically in terms of municipalities, Turin (Grassi monitoring station) is the worst performer municipality with 98 days above the WHO threshold, followed by Venice (via Tagliamento station) with 88 days, Padova (Arcella station) with 84 days, Rovigo (Largo Martiri station) with 83 days, Treviso(via Lancieri station) with 80 days, and Milan (Marche station) with 79 days. All these cities are in the North of the country and in the Po Valley (Venice can be considered at its border). Unfortunately, in this area the number of EEZ is very limited and the robustness check can be performed only on the broader set of park municipalities including regional parks.

We therefore test whether the park municipality effect applies to this particularly difficult area, i.e., the Northern Italy. To this purpose, Fig. A2 and Table A9 in the Appendix replicate Figs. 2B and A2 and Table 1, respectively, for the Northern regions only. More specifically, Fig. A2A shows the dynamics of daily deaths for park and non-park municipalities, and Fig. A2B shows the average daily deaths for park and non-park municipalities, and Table A9 shows the base econometric estimates of the paper. All our findings are confirmed when we restrict the sample to municipalities in the Northern regions.

6. Discussion

Econometric findings discussed above reject the null of absence of significant effects of park areas on yearly changes in daily per capita deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Park area incidence can in principle follow a structural (time invariant) and a time varying direction. Pooled estimates allow us to capture both at the cost of omitting possible time invariant factors beyond those effectively introduced in the regressions. The advantage of the fixed-effect panel estimates from this point of view is that they allow to estimate the impact of parks controlling for time-invariant, unobservable factors. A potential example of this factor is long-term lower exposure to particulate matter, which is a notably crucial driver of pulmonary diseases as pointed out by Pope and Dockery [18] in their survey. Our pooled estimates using the three different park measures show that the wider (including all regional parks) and less restrictive (regardless the share of the municipality located in a park) park measures is sufficient to show statistically significant and negative effects on changes in daily deaths between COVID-19 and pre-COVID-19 period. Our fixed-effect panel estimates show that the tighter and more restrictive definition of park area – as proxied by the EEZ measure – is necessary to find significant and negative trend in these areas compared to non-park areas.

A limit of our analysis is that we do not dispose of additional socio-demographic controls such as levels of comorbidities and socioeconomic status. Time-invariant components of this factors are captured by fixed effects, but we cannot control for time-varying components of them. Moreover, although excess deaths are considered a better measure to understand the true impact of COVID-19 [26], this measure is not free of limitations. For instance, the place where people die may represent a bias as our measure record deaths based on the municipality of residence.

Our results obviously open the questions about causality links. As it is well known, it is impossible to perform a randomised experiment on an ongoing phenomenon (i.e., implement ex-ante a controlled experiment with treatment and control samples with balanced properties). The ex-post analysis of the drivers of COVID-19 deaths we carried out cannot therefore ascertain a causal interpretation to the observed significant correlations. In tackling this issue, we should, however, consider that the reward of park areas that defines our three park municipality measures is obviously antecedent to and unaffected by the outbreak of COVID-19. Therefore, we rule out potential endogeneity determined by reverse causality. The remaining concern is whether omitted variables can be correlated both with the park municipality definition and our dependent variable, thereby creating a spurious correlation among the two. The obvious candidate is air quality, but this is exactly our hypothesis: mortality rates at the time of COVID-19 have been significantly lower in park municipalities when compared to those in the two previous years, most likely because residents’ exposure to pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, and NO2 is presumed to be significantly smaller in these areas. Another potential omitted variable that could contribute to explain our results is the presence of economic activities that may negatively affect the quality of the natural park resource. Related to this point, we expect that policies aimed to preserve value and attractiveness of the natural resources contained in parks and preserved areas will discourage such activities. Again, this is an expected result of environmental policies focusing on preservation of natural resources and could therefore be considered an effect of a policy aiming to expand park areas. Consider, however, that we partially control for industry characteristics in the robustness checks (Table A7). The same reasoning applies for the possibility of performing physical activity in a clean environment with positive consequences on health. More in general, these omitted factors, being themselves a direct intended consequence of the creation of park areas or a driver of the nexus between park municipality and mortality, do not weaken but reinforce our policy conclusions: the creation of park areas has beneficial effects on health and exposure to health (pandemic) risks; a policy aiming at expanding such areas will eventually improve air quality and discourage (or explicitly ban) more polluting economic activities that can harm preservation of the natural resource.

A final issue is that park municipalities can be characterized by a low volume of human interactions; this can be a factor determining also the significantly lower adverse COVID-19 outcomes in such areas. Note, however, that the models estimated in this paper control for this factor in three ways. First, we look at per capita deaths and therefore scale our dependent variable by the local population, thereby implicitly considering the role of human interactions that are significantly higher in number when more population is concentrated in the municipality area. Second, we include municipality population density as control in our pooled estimates. Third, the “structural” time invariant effect of human interactions in each municipality is absorbed into the fixed effect when we implement panel regression models.

Our findings, their limitations and the related discussion can stimulate further research in this direction testing, for instance, the “external validity” of our results in different countries affected by the epidemic.

As our significant findings do reveal a causality nexus a straightforward implication of our paper is that natural park areas not only have a positive and significant effect on health and the quality of the environment but also reduce exposure to health shocks. The policy issue is obviously whether it is possible to avoid a trade-off between the health and environment domains, on the one side, and the economic activity and job domains on the other side. The trade-off is clearly highlighted by the economic significance of our results taken to the extreme. If Italy were made by park municipalities with significant areas in natural parks, and if we interpret our findings as causal, based on the magnitude of the EEZ park municipality coefficient (Table A6), we would have around 582 less COVID-19 deaths per day during our sample period. However, many observers would note that economic life and employment would suffer under such extreme scenario of a country only made by park municipalities.

The trade-off may however be apparent if we examine the issue from a different perspective. Pini and Rinaldi [33] show that Italian regions mostly hit by the pandemics exhibit a far higher rate of firm and job destruction and a far lower rate of firm and job creation in March-April 2020. The presence of areas with characteristics that are opposite to those of our park municipalities have therefore made the lockdown much starker with dramatic negative consequences on economic activities. As well, innovation in terms of circular economy, dematerialization/digitalization and, more in general, improvement in energy efficiency of manufacturing and agricultural production can reduce the trade-off even in non-extreme times as those of the COVID-19 epidemics. Evolution along this path can lead us to a productive system in which the creation of economic value is decoupled from deterioration of natural resources, thereby eventually mitigating the trade-off and allowing park municipalities to match economic activity and environmental quality. The same EEZ government decree in 2019 defines areas of significant environmental relevance (at least 45% of their surface area in parks, reserves, or naturally protected areas) with the goal of providing incentives for environmentally sustainable economic activities in those areas. The goal is exactly that of increasing the creation of economic value without harming environmental quality, thereby increasing circularity (creation of economic value per unit of environmental resource used) in order to avoid the trade-off between health an environmental quality on the one side and economic activity on the other side.

7. Conclusion

We analyze how excess daily deaths in municipalities within protected areas differ from those outside these areas during the first lockdown in Italy. We find that mortality in protected areas was already lower than in the rest of the country before 2020. During the lockdown, while mortality increased overall, excess deaths in park municipalities increased at a lower rate than elsewhere. Moreover, we perform several robustness checks to see the role of different types of natural parks (i.e., EEZ), the role of essential firms which continue to operate during the lockdown, and what happens if we exclude large and small cities that may create a bias. We also estimate both pooled and fixed-effects models to test the overall and the time-trend effect of a park on mortality. All our findings confirm the negative effect of natural parks on mortality. Finally, we suggest how policy-makers can draw implications from our evidence and promote one health policies that benefit at the same time the environment and the health of people by emphasizing how circularity reconciling creation of economic value with environmental sustainability has to be the main policy goal. On this point, we remark that national park regulation includes very severe contraints to building (i.e., the impossibility to increase building areas unless for reasons related to park maintenance or for exceptions consistent with the park goals) and farming activity. Park area constraints include no hunting and no flower picking. A trade-off between environmental sustainability and landscape protection as well exists since there are strong limitation to installation of solar panels in park areas, too. Based on our findings, we argue that green areas should be extended bringing with them their statutory limits on land use; at the same time, the system of incentives for environmentally sustainable economic activity in these areas can help to reconcile creation of economic value with health and environmental sustainability, becoming a frontier for the generation of a new circular paradigm where trade-offs among the three goals are minimised. For this reason, parks – and especially EEZ – can become areas stimulating innovation in the direction of creation of economic value without deterioration of air quality. This goes in the direction requested by the development of circular economy where ratios between gross domestic product or value added and particulate matter are both expected to grow. In this respect, a promising direction to be followed is that suggested by the EEZ law that identifies green areas and provides incentives for the development of environmentally sustainable economic activities in these areas. The goal is that of promoting innovation that can reconcile creation of economic value and environmental quality toward an integrated approach that moves away from the dichotomy between green, healthy areas with low density and low economic activity, and densely populated areas with high economic activity and low environmental quality. The achievement of this goal is possible only with innovation promoting environmentally sustainable modes of creation of economic value.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.10.005.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Frumkin H., Bratman G.N., Breslow S.J., Cochran B., Kahn P.H., Jr, Lawler J.J., Wood S.A. Nature contact and human health: a research agenda. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(7) doi: 10.1289/EHP1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branas C., Cheney R., et al. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(11):1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon–Larsen P., Nelson M., Page P., et al. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humpel N., Owen N., Leslie E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(3):188–199. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mowen A. Active Living Research; 2010. Parks, playgrounds and active living. Retrieved February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallis J., Kerr J. Physical activity and the built environment. President’s Council Phys Fitness Sports Res Digest. 2006;7(4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoup L., Ewing R. Active Living Research; 2010. The economic benefits of open space, recreation facilities and walkable community design. Retrieved February 16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buxton R.T., Pearson A.L., Allou C., Fristrup K., Wittemyer G. A synthesis of health benefits of natural sounds and their distribution in national parks. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2021;118(14) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2013097118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenstone M., Nigam V. University of Chicago; 2020. Does social distancing matter? Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-26. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang H., Wang L., Yang Y. Human mobility restrictions and the spread of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China. J Public Econ. 2020;191 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becchetti L., Conzo G., Conzo P., Salustri F. Understanding the heterogeneity of COVID-19 deaths and contagions: the role of air pollution and lockdown decisions. J Environ Manage. 2022;305 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatto M., Bertuzzo E., Mari L., Miccoli S., Carraro L., Casagrandi R., Rinaldo A. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: effects of emergency containment measures. Proceedings of the Nat Acad Sci. 2020;117(19):10484–10491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004978117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liotta G., Marazzi M.C., Orlando S., Palombi L. Is social connectedness a risk factor for the spreading of COVID-19 among older adults? The Italian paradox. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alacevich C., Cavalli N., Giuntella O., Lagravinese R., Moscone F., Nicodemo C. The presence of care homes and excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Italy. Health Econ. 2021;30(7):1703–1710. doi: 10.1002/hec.4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perone G. The determinants of COVID-19 case fatality rate (CFR) in the Italian regions and provinces: an analysis of environmental, demographic, and healthcare factors. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becchetti L., Beccari G., Conzo G., Conzo P., De Santis D., Salustri F. Particulate matter and COVID-19 excess deaths: decomposing long-term exposure and short-term effects. Ecolog Econ. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krupnick A., Harrison K., Nickell E., Toman M. The value of health benefits from ambient air quality improvements in Central and Eastern Europe: an exercise in benefits transfer. Environ Resource Econ. 1996;7(4):307–332. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pope C.Arden, III, Dockery Douglas W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2006;56(6):709–742. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schraufnagel D.E., et al. Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: a review by the forum of international respiratory societies’ environmental committee, part 1: the damaging effects of air pollution. Chest. 2019;155:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X., Nethery R.C., Sabath B.M., Braun D., Dominici F. MedRxiv; 2020. Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavanagh Jo-Anne E., Peyman Zawar-Reza, Gaines Wilson J. Spatial attenuation of ambient particulate matter air pollution within an urbanised native forest patch. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2009;8(1):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jim Chi Yung, Chen Wendy Y. Assessing the ecosystem service of air pollutant removal by urban trees in Guangzhou (China) J Environ Manage. 2008;88(4):665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nowak David J., Crane Daniel E., Stevens Jack C. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban forestry & urban greening. 2006;4(3–4):115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin S., Shen Z., Zhou P., Zou X., Che S., Wang W. Quantifying air pollution attenuation within urban parks: an experimental approach in Shanghai, China. Environ pollut. 2011;159(8–9):2155–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becchetti, L., Beccari, G., Conzo, G., Conzo, P., De Santis, D. and Salustri, F. (2021). Park municipalities and air quality. Available at SSRN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Konstantinoudis G., Cameletti M., Gómez-Rubio V., Gómez I.L., Pirani M., Baio G., Blangiardo M. Regional excess mortality during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in five European countries. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28157-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fior M., Mpampatsikos V. COVID-19 and estimates of actual deaths in Italy. Scenarios for urban planning in Lombardy. J Urban Manage. 2021;10(3):275–301. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campo G., Fortuna D., Berti E., De Palma R., Di Pasquale G., Galvani M., Casella G. In-and out-of-hospital mortality for myocardial infarction during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Emilia-Romagna, Italy: a population-based observational study. The Lancet Regional Health-Europe. 2021;3 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinceti M., Filippini T., Rothman K.J., Di Federico S., Orsini N. The association between first and second wave COVID-19 mortality in Italy. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12126-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santi L., Golinelli D., Tampieri A., Farina G., Greco M., Rosa S., Giostra F. Non-COVID-19 patients in times of pandemic: emergency department visits, hospitalizations and cause-specific mortality in Northern Italy. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosa I., Castelli A., Castelli M., Ciani O., Compagni A., Galizzi M.M., Vainieri M. Corona-regionalism? Differences in regional responses to COVID-19 in Italy. Health Policy (New York) 2021;125(9):1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borri N., Drago F., Santantonio C., Sobbrio F. The “Great Lockdown”: inactive workers and mortality by COVID-19. Health Econ. 2021;30(10):2367–2382. doi: 10.1002/hec.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pini M., Rinaldi A. Nuova imprenditorialità mancata e perdita di occupazione: prime valutazioni sugli effetti della pandemia sul sistema produttivo italiano. EyesReg. 2020;10(3) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.