Abstract

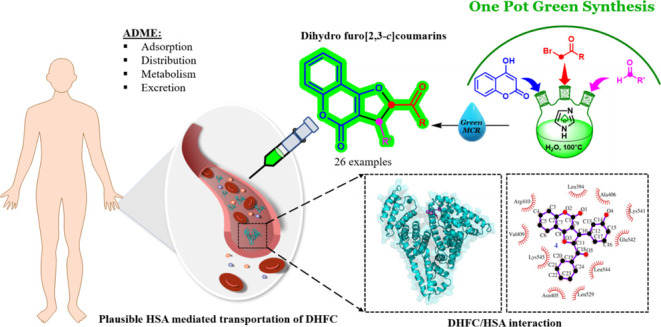

For the first time, an eco-friendly and efficient one-pot green multicomponent approach has been described to synthesize functionalized trans-2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarins (DHFCs). In this synthesis, imidazole and water were used as the catalyst and solvent, respectively, under mild conditions. Applications of the developed catalytic process in a water medium revealed the outstanding activity, productivity, and broad functional group tolerance, affording a series of newly designed DHFC and derivatives in excellent yields (72–98%). Moreover, the human serum albumin (HSA) binding ability of the synthesized DHFC derivatives has been uncovered through the detailed in silico and in vitro-based structure-activity analysis. The ability to bind HSA, the most abundant serum protein, in the low micromolar ranges unequivocally reflects the suitable absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination profile of the synthesized compounds, which may further be envisaged for their therapeutic usage endeavors.

Introduction

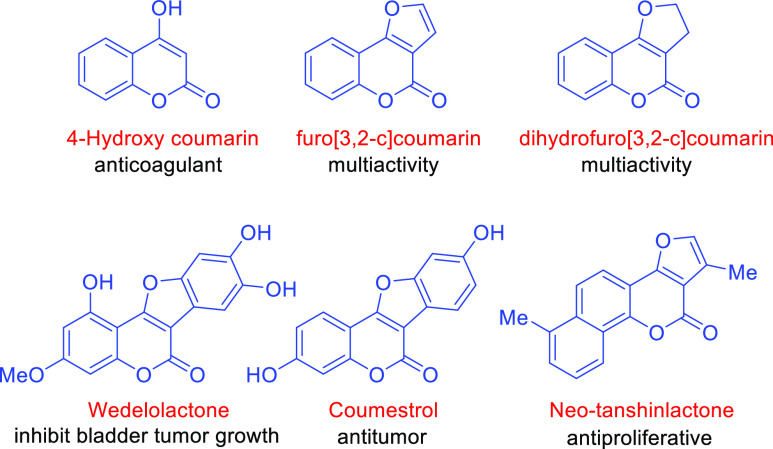

4-Hydroxy coumarin is one of the most important heterocyclic building blocks found in varied biologically active natural products and drug molecules. Warfarin, brodifacoum, dicumarol, coumatetralyl, coumafuryl, and difenacoum are well-known examples of current drugs molecules that possess 4-hydroxy coumarin as a core structural moiety.1−4 Moreover, wedelolactone, coumestrol, and neo-tanshinlactone are emerging potential candidates to this end that revealed promising activities (Figure 1).5,6 Recently, trans-2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarins (DHFCs) (derivatives of 4-hydroxy coumarin) are of great interest among coumarins possessing a unique 4H-furo ring fused with coumarin, which are well-known for their medicinal importance, therapeutic activities, and applications in myriad pharmaceutical ingredients.7,8 Several drug candidates containing the furo[3,2-c]coumarin and DHFC skeleton display an extremely wide range of biological activities such as anticoagulant, antibacterial, antifungal, antitumor, antiviral, anticonvulsant, anticancer, antimicrobial, antiprotozoal, insecticidal, fungicidal, antimycobacterial, antimutagenic, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory.9−22 For instance, natural products austocystin A and D and neo-tanshinlactone isolated from the maize meal cultures of Aspergillus ustus and Salvia miltiorrhiza, respectively, displayed potent antitumor activities and cytotoxicity against breast cancer.23,24 In addition, naphthalene-functionalized DHFCs are known as antioxidant and anthelmintic agents.25

Figure 1.

Representative core skeleton and some naturally occurring furo-fused coumarins with relevant activity.

Furthermore, coumarins and their derivatives are found to inhibit prostaglandin biosynthesis, particularly fatty acid hydroperoxy intermediates.26,27 Along with this, many functionalized coumarins are found to show potential as a fluorescent chemosensor, a fluorescent probe, laser dyes, and a light absorber for solar cells, optical brighteners, and organic light-emitting diodes.28,29

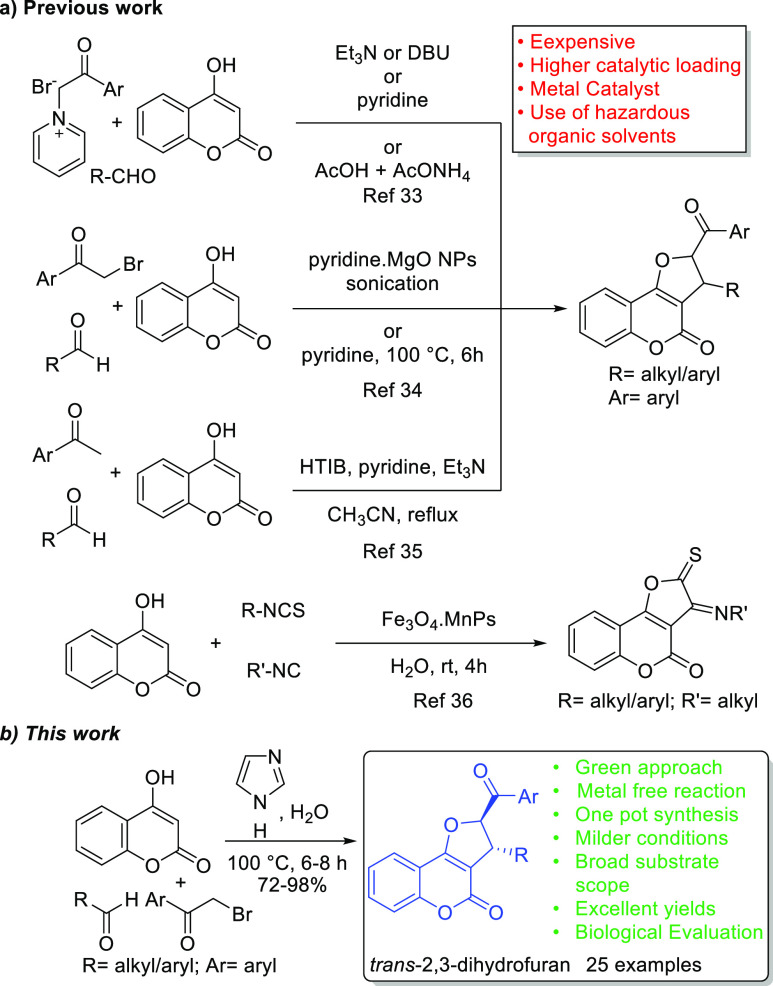

Due to the broad-scale pharmaceutical applications coupled with their high demand in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery, the privileged structure of DHFCs is found to appear in numerous medicinally important scaffolds worldwide. Moreover, great attention from researchers has been given to their organic synthesis, which has led to several elegant methodologies for their rapid construction and stimulated intense research activities toward their structural modification and biological evaluation.30−32 Several syntheses of DHFCs in the literature reported the one-pot, tandem reaction of pyridinium ylide, 4-hydroxycoumarin, and aldehyde catalyzed by Et3N/DBU/pyridine or a mixture of AcOH and AcONH4 to synthesize various fused 2,3-dihydrofuran derivatives including 2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]chromen-4-ones. In addition, Wadhwa et al. developed the multicomponent reaction catalyzed by pyridine and Et3N in CH3CN to synthesize naphthalene-functionalized DHFC and featured its screening toward antioxidant and anthelmintic activities.33 Subsequently, the alternative pathway disclosed by Safaei-Ghomi et al., where MgO nanoparticles along with pyridine have been used as a catalyst for the diastereoselective preparation of DHFC under ultrasonic irradiation, and the method of Kamal et al. (pyridine-catalyzed one pot synthesis) are well-described toward this end.34 Alternatively, modified approaches by Kumar and group (HTIB, pyridine with Et3N, and CH3CN via in situ generated α-tosyloxyketones) and Samant et al. [microwave-assisted, 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP)-mediated multicomponent approach] have been reported. Several metal-catalyzed pathways have also been developed promisingly, and among them, copper-catalyzed synthesis of coumarins has been evaluated to its great extent (Scheme 1).35

Scheme 1. Comparative Study.

As a result of this surge, the multicomponent reaction was found to be the best strategy among all the reported methods that could construct the required skeleton efficiently in a single-step sequence. Fascinatingly, the application of multicomponent reactions toward the synthesis of varied DHFCs from 4-hydroxy coumarins has been evolved exponentially. Hossaini and co-workers developed the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles-catalyzed three-component reaction in water to synthesize a series of 4H-chromin derivatives,36 whereas Mosslemin et al. documented the N-(2-(4-halobenzoyl)-2-oxoethyl)pyridinium bromide and nano γ-Fe2O3-quinuclidine-based catalyzed diastereoselective synthesis of DHFC derivatives under the water reflux condition.37 A recent review by Kaufman and Mancuso also discussed about several synthetic efforts toward 2,3-disubstituted furo[3,2-c]coumarins and the development of multicomponent reactions toward this end.35c,38 Despite phenomenal advances in the divulged methodologies, there is an undeniable potential for an efficient and environmentally friendly approach to synthesize DHFCs that can overcome the prior reports of expensive and higher catalytic loading, harsh reaction conditions, tedious procedures, use of hazardous organic solvents, inadequate yields, and a constrained substrate scope. Looking into the excellent medicisnal profile and essential requirement, DHFC demand a scalable method along with novel functionalized analogues for further drug discovery and development. Herein, with an aim to envisage their therapeutic usage, we set out to optimize an eco-friendly one-pot strategy to synthesize varied functionalized DHFCs along with their novel derivatives targeting in silico and in vitro-based structure–activity analysis. Therefore, in continuation of our unwavering interest in developing an environmentally friendly multicomponent reaction,39−41 we investigated the combined chemistry of 4-hydroxycoumarin, aldehyde, and α-bromoacetophenone, catalyzed by imidazole using only water as a green solvent. In our effort to overcome drawbacks from the previous report and formulate an efficient green approach, for the first time, we disclose here an imidazole-catalyzed simplest technique in aqueous media at moderate temperature for the synthesis of a densely substituted DHFC framework. The described synthetic approach culminated into a simple, eco-friendly, one-pot methodology that produced 25 desired DHFC derivatives including 13 novel products in high yields with no transitional isolation. We believe that the synthesized novel DHFC derivatives will manifest excellent therapeutic usage potentials, for which detailed ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination) profiling of these compounds is a prerequisite. In recent years, the use of human serum albumin (HSA) in therapeutics has been profoundly explored. The high abundance of this protein in human plasma (∼600 μM), the unique ability of HSA to transport a diverse set of ligands to the specific organs/tissues, and especially its amenability to genetic/protein engineering techniques to accommodate organ/tissue-specific transportation signals without losing the ligand binding ability make it a lucrative drug nano-carrier agent. Considering the wide spectrum clinical importance of previously reported coumarins and their derivatives, as well as considering the multifaceted drug nano-carrier roles of HSA, in the present work, we conducted a detailed in silico and in vitro-based interaction analysis of the synthesized DHFC derivatives with purified HSA. The interaction presented herein will be useful to understand serum stability and HSA-mediated targeted druggability of these compounds.

Results and Discussion

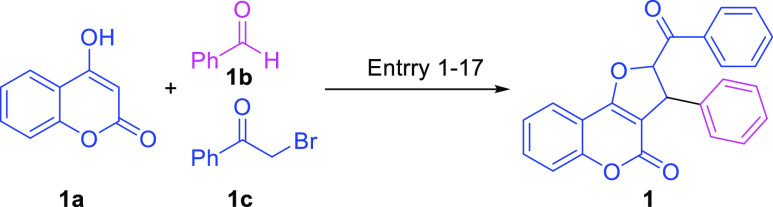

Being inspired by our earlier report on developing a taurine-catalyzed green multicomponent reaction for the synthesis of densely substituted dihydropyrano[2,3-c] pyrazoles42 and our recent report on the taurine-catalyzed green reaction for the synthesis of natural and designed 3,3′-bis(indolyl)methanes (BIMs),43 we became interested in assessing the efficacy of the organocatalyst in water to boost the multicomponent reaction. In our quest to find the best catalytic condition to access furocoumarins and their derivatives, the reaction was performed with 4-hydroxycoumarin 1a, benzaldehyde 1b, and bromoacetophenone 1c as the model substrate under different sets of catalysts, solvents, and conditions. The results thus obtained of the method development toward affording DHFC 1 are summarized in Table 1. Initially, the model reaction of 4-hydroxycoumarin 1a (1 mmol), benzaldehyde 1b (1 mmol), and bromoacetophenone 1c (1 mmol) was attempted using our earlier developed protocol of the taurine-catalyzed water-mediated strategy. However, the taurine-catalyzed reaction performed at 65 °C for 24 h failed to deliver the required DHFC and instead gave an undesired Knoevenagel adduct of coumarin 1a and benzaldehyde 1b (entry 1, Table 1).44−46

Table 1. Selected Optimization Studies to Access 2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarin and Analoguesa.

| entry | catalystb | solventc | temp (°C) | time (h) | yieldd (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | taurine | H2O | 65 | 24 | |

| 2 | Ph3P | MeCN | 65 | 24 | |

| 3 | Cu(OTf)2 | MeCN | 65 | 24 | |

| 4 | Hg(OAc)2 | MeCN | 65 | 24 | |

| 5 | p-TsOH | MeCN | 65 | 24 | |

| 6 | imidazole | MeCN | 65 | 24 | 25 |

| 7 | imidazole | THF | 55 | 24 | 20 |

| 8 | imidazole | DCE | 100 | 8 | trace |

| 9 | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 20 | 35 |

| 10 | imidazole | EtOH | 55 | 12 | trace |

| 11 | imidazole | H2Oe | 90 | 12 | trace |

| 12f | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 6 | 18 |

| 13g | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 8 | 20 |

| 14h | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 16 | 20 |

| 15i | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 15 | 45 |

| 16j | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 6 | 97 |

| 17k | imidazole | H2O | 100 | 5.5 | 90 |

| 18 | DABCO | H2O | 100 | 8 | |

| 19 | Et3N | H2O | 100 | 8 | |

| 20 | NMIl | H2O | 100 | 8 | 25 |

Reaction conditions: 4-hydroxycoumarin 1a (1.0 mmol), benzaldehyde 1b, and bromoacetophenone 1c (1.0 mmol).

Catalyst (1.0 equiv).

Solvent 3–5 mL.

Isolated yields.

Solvent H2O/EtOH (1:1) was used.

(1.0 equiv) K2CO3 was used with the catalyst.

(1.0 equiv) DMAP was used with the catalyst.

Catalyst used 0.5 equiv.

Catalyst used 1.5 equiv.

Catalyst used 2.0 equiv.

Catalyst used 3.0 equiv.

N-methylimidazole (NMI).

On the other hand, the reaction did not work when carried out in the presence of PPh3 as a catalyst under the CH3CN and 65 °C condition. To understand the role and effect of the catalyst, reactions were examined under different acids such as Cu(OTf)2, Hg(Oac)2, and p-TsOH in MeCN at 65 °C but were found to be ineffective in producing the desired skeleton of product 1 (entries 3–5, Table 1).

To our delight, the reaction with the newly implemented amphoteric catalyst imidazole (1.0 equiv) proceeded smoothly in MeCN at 65 °C to afford the desired product 2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarin 1 selectively in 24 h with 25% yield (entry 6, Table 1). Further, to optimize the reaction condition, combinations of solvents and temperatures variations were used. Notably, the results obtained by changing the solvent from MeCN to tetrahydrofuran (THF), dichloroethane (DCE), H2O, EtOH, and a H2O/EtOH mixture delivered the required product but in trace or marginal yields (entries 7–11, Table 1). Moreover, the reduction in yield was observed when the reaction was performed in water with additives K2CO3 and DMAP leading to only 18 and 20% yields, respectively (entries 12 and 13, Table 1). On the other hand, the decrease of catalyst loading (imidazole; 0.5 equiv) led to a decrease in the yield, 20% (entry 14, Table 1). Interestingly, the increase of catalyst loading (imidazole; 1.5 equiv) in aqueous media delivered the required product with 45% yield in 15 h (entry 15, Table 1). Remarkably, the highest yield of 97% was obtained in just 6 h, when the reaction was performed using 2.0 equiv of the catalyst (imidazole) in a water medium (entry 16, Table 1). Further, increasing the equivalent amount of the catalyst (imidazole; 3.0 equiv), the reaction was completed in 5.5 h, but the yield was reduced to 90% (see entry 17, Table 1). Moreover, we performed the rection with 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO), Et3N, and NMI (entries 18–20, Table 1), but the best result obtained was of the imidazole-catalyzed water-mediated multicomponent reaction at 100 °C that gave 97% yield with an excellent selectivity (entry 16, Table 1).

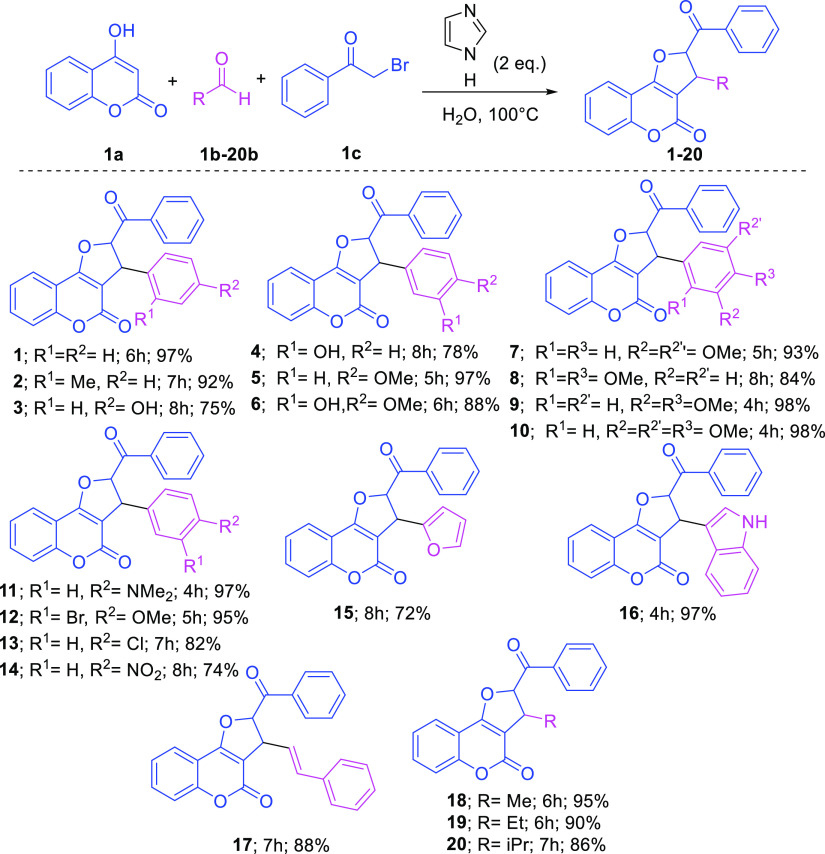

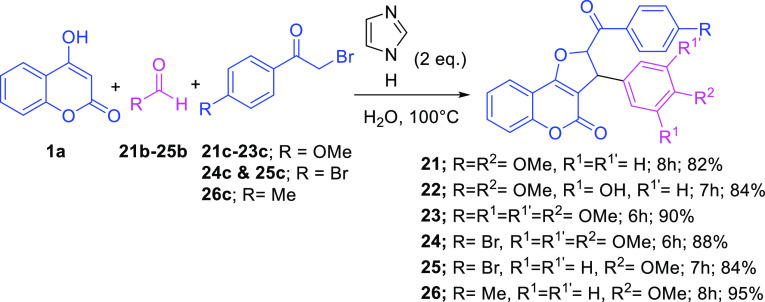

Having the optimized reaction conditions in hand (Imidazole 2.0 equiv; H2O; 100 °C), we examined the scope and generality of the developed protocol by the reaction of coumarin 1a and 2-bromoacetophenone 1c with a range of aldehydes 1b–20b, and the findings are disclosed in Scheme 2. Thus, the imidazole-catalyzed water-mediated green multicomponent reactions of coumarin 1a and 2-bromoacetophenone 1c with varying aldehydes 1b–20b proceeded smoothly, which resulted in several new designed analogues 1–20 in 72–98% yield (Scheme 2). The developed strategy was well-tolerated for both the aromatic aldehydes 1b–17b and aliphatic aldehydes (18b–20b) to construct 20 designed DHFCs including 13 novel analogues in excellent yields. Notably, aromatic aldehydes possessing an electron-donating group (Me, OH, OMe, and NMe2) or an electron-withdrawing group (Br, Cl, and NO2) at the meta and/or para positions afforded the corresponding products in excellent yield (72–98%; Scheme 2). However, the substitution at the ortho position (−Me 2b, and −OMe 8b) in aromatic aldehydes resulted in a lower yield with a ,longer reaction time probably due to the steric hindrance. To our delight, the developed method performed excellently even with the heterocyclic aldehydes such as furfural 15b and indole-3-carboxaldehyde 16b, which formed compounds 15 and 16 with an excellent yield (Scheme 2). Notably, the developed method was also utilized successfully for cinnamaldehyde 17b and aliphatic aldehydes 18b–20b, which generated coumarin dihydrofurans 17 and 18–20 in 88 and 86–95% yields, respectively (Scheme 2). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first simplest cum green report on the catalytic activity of amphoteric imidazole for such an organic transformation. Structures of all the synthesized analogues bearing DHFCs 1–20 were confirmed unambiguously from their spectroscopic analysis [1H NMR, 13C NMR, infrared (IR) spectroscopy, and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS)]. Inspired by the outcome of the developed green multicomponent approach and to further investigate the extent of the proposed catalytic system, we next turned our attention to construct advance DHFC derivatives 21–25 utilizing substituted 2-bromoacetophenone compounds 21c–26c (Scheme 3). Intriguingly, the imidazole-catalyzed water-mediated one-pot three-component reactions of 4-hydroxy coumarin 1a, aldehydes 21b–26b, and substituted 2-bromoacetophenone compounds 21c–26c (4-OMe/4-Br/4-Me) under the optimized condition proceeded very well and produced the required well-designed analogues DHFCs 21–26 with 82–95% yields, respectively (Scheme 3). The structure of all the synthesized advanced analogues of DHFCs 21–26 were validated unambiguously from their spectroscopic investigation (1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR spectroscopy, and HRMS) (see the Supporting Information for details).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarin Derivatives 1–20.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarin Derivatives 21–25.

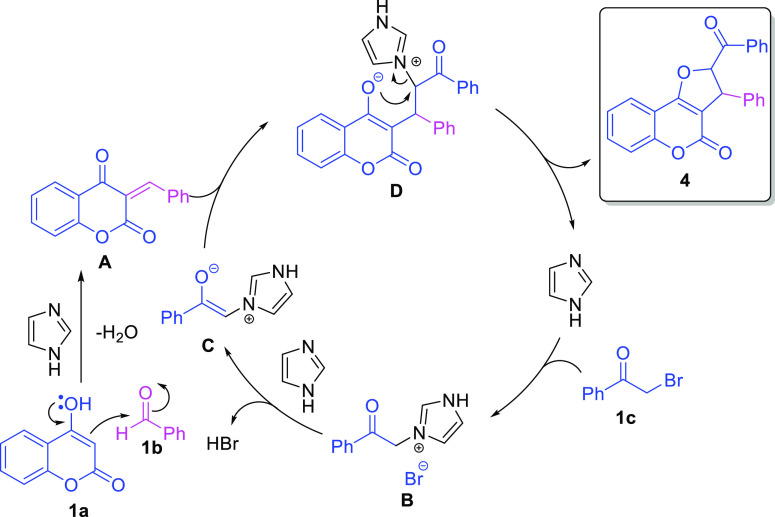

Plausible Mechanism

A plausible mechanism for the said imidazole-catalyzed water-mediated one-pot three-component reactions of 4-hydroxy coumarin 1a, aldehydes 1b, and 2-bromoacetophenone of 1c to construct DHFCs is shown in Scheme 4. The catalyst imidazole is amphoteric in nature (pKa = 14.5) and highly soluble in water due to its highly polar characteristic. 4-Hydroxy coumarin 1a reacts with aldehyde 1b in the presence of imidazole to give the Knoevenagel adduct A. Simultaneously, 2-bromoacetophenone 1c reacts with imidazole to give an intermediate imidazoloium bromide B, which further generates nucleophile imidazolim ylide C. Further, nucleophile C attacks the so-formed Knoevenagel adduct A to generate intermediate D, and sequentially, intermediate D undergoes the cyclization to give product 4 and regenerates imidazole for the next catalytic cycle (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Plausible Reaction Mechanism for the Synthesis of DHFCs 1–25.

Biological Evaluation

Coumarins and their derivatives have been found to be effective against myriad clinically important molecular targets, exerting their pharmacological actions such as anti-neoplastic, antibacterial, anti-fungal, and anti-inflammatory activities to name a few.47−50 Recently, the cytotoxicity profiles and the DNA binding activities of the (DHFC) derivatives have been discovered,51 which may indicate their potential candidature for future clinical usages. However, the efficiency of a drug depends on their selective localization to the target tissue/organ in therapeutic concentration, which will maximize their molecular action as well as will minimize the chance for off-target binding and related side effects.52

Moreover, other than the ambiguous non-specific distribution, small molecule-based therapeutic leads (or drugs) often suffer the fate of low effective plasma concentrations due to low solubility as well as rapid renal clearance with concomitant effective plasma circulatory time.53 To cope up with these problems, state-of-the-art drug delivery systems or vehicles are on high demand. In this context, serum albumin is one of the proteins of choice as the drug nanocarrier.54

HSA naturally transports multiple physiological (fatty acids, hormones, bile salts, etc.) and non-physiological (xenobiotics, e.g., drug molecules) ligands across the body.55 has has several functionally independent ligand binding sites,56 and upon binding with the small molecule ligand(s), HSA can significantly increase the serum circulatory half-life of the bound ligand(s) by preventing their renal clearance as well as protecting them from degradation or chemical modification(s) by physiological enzymes. The HSA-based drug nano-carrier system is also highly effective for those therapeutic leads that suffer from low-solubility issues in human serum. Other than that, several cellular HSA specific receptor molecules have been discovered to date, which can be exploited to maximize the tissue/organ specific targeting of therapeutic leads/drugs carried by the HSA molecule.57 Furthermore, the HSA nano-carrier molecules can be engineered to carry tissue/organ specific tags for targeted drug delivery.54,57

Binding of Synthesized DHFC Derivatives with HSA

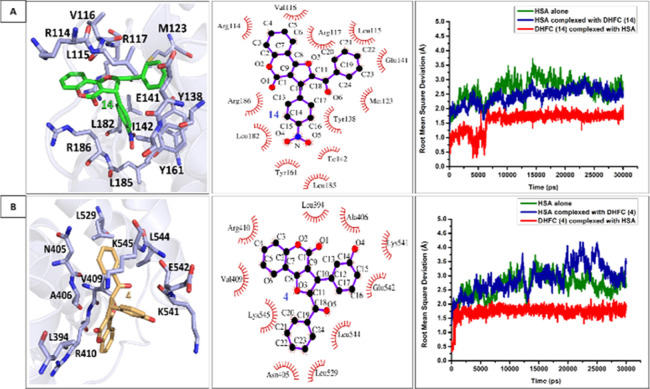

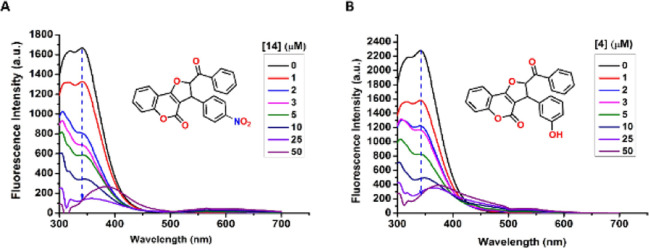

Here, we tested the HSA binding ability of the synthesized DHFC derivatives with purified HSA through in silico and in vitro-based techniques. Intriguingly, in silico docking analysis indicates that all of the synthesized DHFC derivatives excellently bind HSA with the free energy of binding (ΔGbinding) ranging from −10.3 kcal/mol (for the best binding derivative 14) to −7.7 kcal/mol (for the worst binding derivative 21) (Supporting Information Table S1). For further details of the in silico and in vitro HSA binding analysis, we chose two different DHFC derivatives that showed the best binding profile and an average binding profile obtained through initial in silico docking analysis (derivative 14 and derivative 4, respectively). All atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analyses were carried out with these two ligands (derivatives 4 and 14) in their HSA-bound states to test the ligand stability and to track ligand-induced protein conformational changes in the simulated physiological conditions. Both of these ligands were found to be highly stable (rmsd < 1 Å) in their respective HSA-bound states during the entire length of simulation time (30 ns) (Figure 2, third panel). HSA contains three helical domains (domains I, II, and III, respectively), each of which is further subdivided into two sub-domains (A and B). The protein is known to bind a variety of endogenous and exogenous ligands (xenobiotics), among which the majority of the clinically important drugs have been found to bind principally at two sites (Sudlow’s sites 1 and 2) located at subdomains IIA and IIIA (Supporting Information Figure S1). Importantly, among these two ligands, DHFC derivative 2 was found to dock at the close proximity of Sudlow site 2 (sub-domain IIIA) of HSA (Figures 2B; Supporting Information Figure S1), which is also well-known to bind several clinically important therapeutic drugs such as ibuprofen, diazepam, propofol, indoxyl sulfate, and diflunisal.55,58,59 Unlike DHFC derivative 4, DHFC derivative 14 was found to dock at a non-trivial drug binding site at sub-domain IB of HSA (Figures 2A and S1), which was previously found to be important for the binding of hemin and was also known for the secondary binding sites for azapropazone and indomethacin.55,60 HSA is also well-known for its ligand-induced structural plasticity,61 which cannot simply be apprehended through molecular docking studies. Therefore, all atomistic MD simulation analyses of docked ligand/HSA complexes were carried out, which indicate simulation time-dependent subtle changes of protein Cα positions compared to the apo-HSA (HSA, free of bound ligands) (Figure 2A,B, third panels). This suggests ligand-induced conformational changes of HSA. HSA has a single tryptophan residue (W214) located at subdomain IIA, distant from docking sites of derivative 4 and 14 (Figure S1). Importantly, W214 fluorescence is highly sensitive for ligand-induced perturbation of its molecular microenvironment. The change in W214 fluorescence spectra with respect to the increasing concentrations of ligands 4 and 14 has been tracked to deduce the allosteric effect of ligand binding on HSA conformational plasticity. Intriguingly, the increasing concentrations of both the tested ligands (DHFC derivative 4 and 14) were found to quench the intrinsic W214 fluorescence of HSA (Figure 3). The resulting fluorescence titration data were used to calculate the dissociation constants (Kd) of these two ligands, which were found to be 2.17 and 2.35 μM for ligands 14 and 4 respectively, indicative of their strong binding with HSA. Importantly, in both of the HSA–ligand complexes, hydrophobic interactions are the sole players to stabilize the ligand–protein complexes (Figure 2A,B middle panels), which may, in turn, justify the high affinity as well as the higher stability of the bound ligands with HSA. However, the high-resolution crystal structure of the HSA/ligand complexes will be imperative to explain the precise mode of these ligand protein interactions.

Figure 2.

Plausible interaction profiles of the synthesized 2,3-dihydrofuro [3,2-c] coumarin (DHFC) derivatives (14 and 4) with HSA. Left panels of (A,B) represent the molecular docking of 14 and 4 with has, respectively. The middle panels of (A,B) show the two-dimensional representations of amino acid interaction profiles of the docked ligands 14 and 4, respectively. The right panels of each figure represent the rmsd profiles of protein–ligand complexes vs that of the free protein, throughout the entire MDs simulation time period (30 ns) to assess the stability of the protein–ligand complexes.

Figure 3.

HSA fluorescence quenching as a function of DHFC binding. (A,B) fluorescence spectra of HSA in the presence of increasing concentrations of DHFC derivatives 14 and 4, respectively.

Conclusions

Here, we have reported an unprecedented catalytic approach for the first time to access functionalized bioinspired DHFCs in an excellent yield via the imidazole-catalyzed green multicomponent reaction of structurally diverse aldehydes and α-bromo acetophenone with 4-hydroxycoumarin in a water medium. As a result, a series of DHFCs and their new designed congeners were synthesized, and their ability to bind the principal protein component of human serum, HSA, has been determined through in silico and in vitro approaches. An excellent ADME profile of any potential therapeutic agent is a prerequisite for its long journey from “bench to bedside”. One of the most crucial factors governing the physiological distribution and the elimination of many potential therapeutic agents is their ability to bind HSA. The detailed in silico and in vitro-based HSA binding analysis of the synthesized DHFC derivatives presented herein may further escalate their prospective future therapeutic usages. Overall, the procedure’s simplicity and water-mediated straightforward methodology make it an outstanding strategy for these intriguing and appealing reaction products, which continue to be in high demand. Further, in search of the potent drug candidate, an effort toward the construction of bioactive furocoumarins and obtaining its advanced biological data is ongoing and would be disclosed in due course.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DHFC

trans-2,3-dihydrofuro[3,2-c]coumarins

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination

- BIMs

3,3′-bis(indolyl)methanes

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c05361.

Experimental procedures, full characterization for all new compounds, in silico evaluation of all compounds, and in silico molecular docking-based binding energy estimation of synthesized DHFC derivatives with HSA (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ G.M. and S.M. contributed equally.

All the authors are thankful to IIT Jodhpur for providing the necessary facilities for completing this work, the HRMS facility [sanction no. SR/FST/CS-II/2019/119(c); project no. S/DST/RDE/20200038], and the financial support in part by the SEED grant (I/SEED/RDE/20190023 and I/SEED/SUB/20200005) and the JCKIF project (S/JCKIF/MTM/20210072), IIT Jodhpur.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Manolov I.; Danchev N. D. Synthesis and Pharmacological Investigations of Some 4-Hydroxycoumarin Derivatives. Arch. Pharm. 2003, 336, 83–94. 10.1002/ardp.200390010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan E. C.; Radomski J. L. The Toxicity of 3-(Acetonylbenzyl)-4-Hydroxycoumarin (Warfarin) to Laboratory Animals. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc., Sci. Ed. 1953, 42, 379–382. 10.1002/jps.3030420620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J.-C.; Park O.-S. Synthetic Approaches and Biological Activities of 4-Hydroxycoumarin Derivatives. Molecules 2009, 14, 4790–4803. 10.3390/molecules14114790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kandhasamy S.; Ramanathan G.; Kamalraja J.; Balaji R.; Mathivanan N.; Sivagnanam U. T.; Perumal P. T. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Evaluation of Chromen and Pyrano Chromen-5-One Derivatives Impregnated into a Novel Collagen Based Scaffold for Tissue Engineering Applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 55075–55087. 10.1039/c5ra07133j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang W.; He X.; Yin H.; Cao W.; Lin T.; Chen W.; Diao W.; Ding M.; Hu H.; Mo W.; Zhang Q.; Guo H. Allosteric Activation of the Metabolic Enzyme GPD1 Inhibits Bladder Cancer Growth via the LysoPC-PAFR-TRPV2 Axis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 93. 10.1186/s13045-022-01312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen H.; Qian Y.; Zhao X.; Lv T.; Wang B.; Gong G.; Qiu X.; Luo L.; Zhang M.; Qin G.; Khaskheli M. I.; Yang C. Compounds From the Root of Pueraria Peduncularis (Grah. Ex Benth.) Benth. and Their Antitumor Effects. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X1988252. 10.1177/1934578x19882521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qin Z.; Zhao M.; Zhang K.; Goto M.; Lee K.-H.; Li J. Fluorinated Modification of Neo-Tanshinlactone and Antiproliferative Activity Evaluation. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2022, 58, 398–403. 10.1007/s10600-022-03694-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wang X.; Nakagawa-Goto K.; Bastow K. F.; Don M.-J.; Lin Y.-L.; Wu T.-S.; Lee K.-H. Antitumor Agents. 254. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Neo-Tanshinlactone Analogues as Potent Anti-Breast Cancer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5631–5634. 10.1021/jm060184d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.-J.; Syu S.; Chen Y.-J.; Yang M.-C.; Lin W. Syntheses of Furo[3,4-c]Coumarins and Related Furyl Coumarin Derivatives via Intramolecular Wittig Reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 843–847. 10.1039/c1ob06571h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borah B.; Dhar Dwivedi K.; Chowhan L. R. 4-Hydroxycoumarin: A Versatile Substrate for Transition-metal-free Multicomponent Synthesis of Bioactive Heterocycles. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2021, 10, 3101–3126. 10.1002/ajoc.202100550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danis O.; Yuce-Dursun B.; Gunduz C.; Ogan A.; Sener G.; Bulut M.; Yarat A. Synthesis of 3-Amino-4-Hydroxy Coumarin and Dihydroxy-Phenyl Coumarins as Novel Anticoagulants. Arzneimittelforschung 2011, 60, 617–620. 10.1055/s-0031-1296335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović I.; Petrović S.; Milenković M.; Stanojković T.; Nikolić D.; Krunić A.; Niketić M. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Activity of Extracts of Ferula Heuffelii Griseb . Ex Heuff . and Its Metabolites. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 1585–1594. 10.1002/cbdv.201400400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Bastow K. F.; Sun C.-M.; Lin Y.-L.; Yu H.-J.; Don M.-J.; Wu T.-S.; Nakamura S.; Lee K.-H. Antitumor Agents. 239. Isolation, Structure Elucidation, Total Synthesis, and Anti-Breast Cancer Activity of Neo-Tanshinlactone from Salvia Miltiorrhiza. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 5816–5819. 10.1021/jm040112r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu J. R.; Singha R.; Hong S. C.; Chang Y. H.; Das A. R.; Vliegen I.; De Clercq E.; Neyts J. Synthesis of New Benzimidazole–Coumarin Conjugates as Anti-Hepatitis C Virus Agents. Antiviral Res. 2008, 77, 157–162. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R.-H.; Zhang Q.; Ma Y.-B.; Luo J.; Geng C.-A.; Wang L.-J.; Zhang X.-M.; Zhou J.; Jiang Z.-Y.; Chen J.-J. Structure–Activity Relationships Study of 6-Chloro-4-(2-Chlorophenyl)-3-(2-Hydroxyethyl) Quinolin-2(1H)-One Derivatives as Novel Non-Nucleoside Anti-Hepatitis B Virus Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 307–319. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin K. M.; Rahman D. E. A.; Al-Eryani Y. A. Synthesis and Preliminary Evaluation of Some Substituted Coumarins as Anticonvulsant Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 5377–5388. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Dean A. M. K.; Zaki R. M.; Geies A. A.; Radwan S. M.; Tolba M. S. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of New Heterocyclic Compounds Containing Thieno[3,2-c]Coumarin and Pyrazolo[4,3-c]Coumarin Frameworks. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2013, 39, 553–564. 10.1134/s1068162013040079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra E. J. T.; Cordeiro C. F.; de Figueiredo Diniz L.; Caldas I. S.; Hawkes J. A.; Carvalho D. T. Coumarins as Potential Antiprotozoal Agents: Biological Activities and Mechanism of Action. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2021, 31, 592–611. 10.1007/s43450-021-00169-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaček F.; Müller C.; Werner A.; Greger H.; Proksch P. Analysis, Isolation and Insecticidal Activity of Linear Furanocoumarins and Other Coumarin Derivatives FromPeucedanum (Apiaceae: Apioideae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 20, 2035–2054. 10.1007/BF02066241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Tan X.; Liang C.; Zhang W. Design, Synthesis, and Antifungal Evaluation of Novel coumarin-pyrrole Hybrids. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021, 58, 450–458. 10.1002/jhet.4180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C.-C.; Cheng M.-J.; Peng C.-F.; Huang H.-Y.; Chen I.-S. A Novel Dimeric Coumarin Analog and Antimycobacterial Constituents from Fatoua Pilosa. Chem. Biodivers. 2010, 7, 1728–1736. 10.1002/cbdv.200900326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall M. E.; Wani M. C.; Manikumar G.; Hughes T. J.; Taylor H.; McGivney R.; Warner J. Plant Antimutagenic Agents, 3. Coumarins. J. Nat. Prod. 1988, 51, 1148–1152. 10.1021/np50060a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fylaktakidou K.; Hadjipavlou-Litina D.; Litinas K.; Nicolaides D. Natural and Synthetic Coumarin Derivatives with Anti-Inflammatory/Antioxidant Activities. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 3813–3833. 10.2174/1381612043382710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symeonidis T.; Fylaktakidou K. C.; Hadjipavlou-Litina D. J.; Litinas K. E. Synthesis and Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation of Novel Angularly or Linearly Fused Coumarins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 5012–5017. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks K. M.; Park E. S.; Arefolov A.; Russo K.; Ishihara K.; Ring J. E.; Clardy J.; Clarke A. S.; Pelish H. E. The Selectivity of Austocystin D Arises from Cell-Line-Specific Drug Activation by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 567–573. 10.1021/np100429s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Hu J.; Zhang L.; Zhang L.; Sun Y.; Xie Y.; Wu S.; Liu L.; Gao Z. In-Vitro and in-Vivo Evaluation of Austocystin D Liposomes. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 355–362. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2012.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Matos M. J.; Vazquez-Rodriguez S.; Fonseca A.; Uriarte E.; Santana L.; Borges F. Heterocyclic Antioxidants in Nature: Coumarins. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 311–324. 10.2174/1385272820666161017170652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bhavsar Z. A.; Acharya P. T.; Jethava D. J.; Patel H. D. Recent Advances in Development of Anthelmintic Agents: Synthesis and Biological Screening. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 917–946. 10.1080/00397911.2019.1695276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. E.; Bykadi G.; Ritschel W. A. Inhibition of Prostaglandin Biosynthesis by Coumarin, 4-Hydroxycoumarin, and 7-Hydroxycoumarin. Arzneimittelforschung 1981, 31, 640–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa A. A. M.; Farag N. A. H.; Soliman G. A. H. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Docking Studies of Novel Benzopyranone Congeners for Their Expected Activity as Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic and Antipyretic Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5059–5070. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasior M.; Kim D.; Singha S.; Krzeszewski M.; Ahn K. H.; Gryko D. T. π-Expanded Coumarins: Synthesis, Optical Properties and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 1421–1446. 10.1039/c4tc02665a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He H.; Wang C.; Wang T.; Zhou N.; Wen Z.; Wang S.; He L. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Evaluation of Fluorescent Biphenyl–Furocoumarin Derivatives. Dyes Pigm. 2015, 113, 174–180. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2014.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L.; Pang Y.; Yan Q.; Shi L.; Huang J.; Du Y.; Zhao K. Synthesis of Coumestan Derivatives via FeCl3-Mediated Oxidative Ring Closure of 4-Hydroxy Coumarins. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2744–2752. 10.1021/jo2000644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mohamed S.; Rachedi Y.; Hamdi M.; Le Bideau F.; Dejean C.; Dumas F. An Efficient Synthetic Access to Substituted Thiazolyl-Pyrazolyl-Chromene-2-Ones from Dehydroacetic Acid and Coumarin Derivatives by a Multicomponent Approach. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2628–2636. 10.1002/ejoc.201600173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Srivastava S.; Gupta G. Cascade [4 + 1] Annulation via More Environmentally Friendly Nitrogen Ylides in Water: Synthesis of Bicyclic and Tricyclic Fused Dihydrofurans. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3269. 10.1039/c2gc36276g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang Q.-F.; Hou H.; Hui L.; Yan C.-G. Diastereoselective Synthesis of trans-2,3-Dihydrofurans with Pyridinium Ylide Assisted Tandem Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 7403–7406. 10.1021/jo901379h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b An L.; Sun X.; Zhang L.; Zhou J.; Zhu F.; Shen Z. A Practical and Diastereoselective Synthesis of Dihydrofurocoumarin from Pyridinium Ylides in Aqueous Medium. J. Chem. Res. 2016, 40, 698–703. 10.3184/174751916x14768944130291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Borah P.; Naidu P. S.; Bhuyan P. J. Synthesis of Functionalized Dihydrofurocoumarin Derivatives from 3-Aminoalkyl-4-Hydroxycoumarin. Synth. Commun. 2015, 45, 1533–1540. 10.1080/00397911.2015.1027405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Altieri E.; Cordaro M.; Grassi G.; Risitano F.; Scala A. Regio and Diastereoselective Synthesis of Functionalized 2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]Coumarins via a One-Pot Three-Component Reaction. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 9493–9496. 10.1016/j.tet.2010.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Wadhwa D.; Arora V.; Arora L.; Arora P.; Parkash O. Synthesis of Naphthalene Functionalized Trans -2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2- c ]Coumarins as Antioxidant and Anthelmintic Agents: Multicomponent Synthesis of Furocoumarins. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2016, 53, 1030–1035. 10.1002/jhet.2431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Safaei-Ghomi J.; Babaei P.; Shahbazi-Alavi H.; Zahedi S. Diastereoselective Synthesis of Trans -2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]Coumarins by MgO Nanoparticles under Ultrasonic Irradiation. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, 929–937. 10.1016/j.jscs.2016.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tangella Y.; Manasa K. L.; Laxma Nayak V.; Sathish M.; Sridhar B.; Alarifi A.; Nagesh N.; Kamal A. An Efficient One-Pot Approach for the Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of Trans-Dihydrofuran Derivatives: Cytotoxicity and DNA-Binding Studies. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 6837–6853. 10.1039/C7OB01456B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sagar Vijay Kumar P.; Suresh L.; Vinodkumar T.; Reddy B. M.; Chandramouli G. V. P. Zirconium Doped Ceria Nanoparticles: An Efficient and Reusable Catalyst for a Green Multicomponent Synthesis of Novel Phenyldiazenyl–Chromene Derivatives Using Aqueous Medium. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2376–2386. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b00056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kumar R.; Wadhwa D.; Hussain K.; Prakash O. Modified One-Pot Multicomponent Diastereoselective Synthesis of Trans -2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]Coumarins via In Situ–Generated α -Tosyloxyketones. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 1802–1807. 10.1080/00397911.2012.671435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Karanjule B. N.; Samant D. S. Microwave Assisted, 4-Dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) Mediated, Onepot, Three-Component, Regio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of Trans- 2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-c]Coumarins. Curr. Microwave Chem. 2014, 1, 135–141. 10.2174/2213335601666140529003616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Dalpozzo R.; Mancuso R. Copper-Catalyzed Synthesis of Coumarins. A Mini-Review. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1382. 10.3390/catal11111382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani-Amiri S.; Arabkhazaeli M.; Hossaini Z.; Afrashteh S.; Eslami A. A. Synthesis of Chromene Derivatives via Three-Component Reaction of 4-Hydroxycumarin Catalyzed by Magnetic Fe 3 O 4 Nanoparticles in Water: Synthesis of Chromene Derivatives via Three-Component Reaction of 4-Hydroxycumarin Catalyzed by Magnetic Fe 3O4 Nanoparticles in Water. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 55, 209–213. 10.1002/jhet.3028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vatanchian R.; Mosslemin M. H.; Tabatabaee M.; Sheibani A. Nano γ-Fe2O3-Quinuclidine-Based Catalyst as a Recyclable Organic Base for the Diastereoselective Synthesis of Trans-2,3-Dihydrofuro[3,2-C]Coumarins. J. Chem. Res. 2018, 42, 439–443. 10.3184/174751918x15341545555671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés I.; Cala L. J.; Bracca A. B. J.; Kaufman T. S. Furo[3,2-c]Coumarins Carrying Carbon Substituents at C-2 and/or C-3. Isolation, Biological Activity, Synthesis and Reaction Mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 33344–33377. 10.1039/d0ra06930b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silveira Pinto L. S.; Couri M. R. C.; de Souza M. V. N. Multicomponent Reactions in the Synthesis of Complex Fused Coumarin Derivatives. Curr. Org. Synth. 2018, 15, 21–37. 10.2174/1570179414666170614124053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi N.; Ahooie T. S.; Hashemi M. M. Multicomponent Domino Reactions in Deep Eutectic Solvent: An Efficient Strategy to Synthesize Multisubstituted Cyclohexa-1,3-Dienamines. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 246, 221–224. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.09.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande M. B.; Bonifácio V. D. B.; Luque R.; Branco P. S.; Varma R. S. Solvent-Free and Catalysts-Free Chemistry: A Benign Pathway to Sustainability. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 24–44. 10.1002/cssc.201300485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali G.; Shaikh B. A.; Garg S.; Kumar A.; Bhattacharyya S.; Erande R. D.; Chate A. V. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Densely Substituted Dihydropyrano[2,3-c]Pyrazoles via a Taurine-Catalyzed Green Multicomponent Approach. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 30734–30742. 10.1021/acsomega.1c04773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan K. A.; Shukla M.; Chauhan A. N. S.; Maji S.; Mali G.; Bhattacharyya S.; Erande R. D. Effective Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Natural and Designed Bis(Indolyl)Methanes via Taurine-Catalyzed Green Approach. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 10438–10446. 10.1021/acsomega.1c07258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kidwai M.; Rastogi S. Reaction of Coumarin Derivatives with Nucleophiles in Aqueous Medium. Z. Naturforsch., B: J. Chem. Sci. 2008, 63, 71–76. 10.1515/znb-2008-0110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Azizi N.; Dezfooli S.; Hashemi M. M. Chemoselective Synthesis of Xanthenes and Tetraketones in a Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent. C. R. Chim. 2013, 16, 997–1001. 10.1016/j.crci.2013.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwai M.; Singhal K.; Rastogi S.; Singhal P. A Convenient K2CO3 Catalysed Regioselective Synthesis for Benzopyrano[4,3-c]Pyrazoles in Aqueous Medium. Heterocycles 2007, 71, 569. 10.3987/com-06-10958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Refouvelet B.; Guyon C.; Jacquot Y.; Girard C.; Fein H.; Bévalot F.; Robert J.-F.; Heyd B.; Mantion G.; Richert L.; Xicluna A. Synthesis of 4-Hydroxycoumarin and 2,4-Quinolinediol Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Effects on the Viability of HepG2 Cells and Human Hepatocytes Culture. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 39, 931–937. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai N.; Kumbhar A. A.; Pokharel Y. R.; Yadav P. N. Anticancer Potential of Coumarin and Its Derivatives. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2996–3029. 10.2174/1389557521666210405160323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H.-L.; Zhang Z.-W.; Ravindar L.; Rakesh K. P. Antibacterial Activities with the Structure-Activity Relationship of Coumarin Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112832. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusty J. S.; Kumar A. Coumarins: Antifungal Effectiveness and Future Therapeutic Scope. Mol. Diversity 2020, 24, 1367–1383. 10.1007/s11030-019-09992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshibl H. M.; Al-Abdullah E. S.; Haiba M. E.; Alkahtani H. M.; Awad G. E. A.; Mahmoud A. H.; Ibrahim B. M. M.; Bari A.; Villinger A. Synthesis and Evaluation of New Coumarin Derivatives as Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 3251. 10.3390/molecules25143251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostom B.; Karaky R.; Kassab I.; Sylla-Iyarreta Veitía M. Coumarins Derivatives and Inflammation: Review of Their Effects on the Inflammatory Signaling Pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 922, 174867. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.174867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Zuo R.; Hudalla G. A. Harnessing Molecular Recognition for Localized Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2021, 170, 238–260. 10.1016/j.addr.2021.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang G. R.; Harris R. Z.; Lau D. T. Pharmacokinetics and Its Role in Small Molecule Drug Discovery Research. Med. Res. Rev. 2001, 21, 382–396. 10.1002/med.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen M. T.; Kuhlmann M.; Hvam M. L.; Howard K. A. Albumin-Based Drug Delivery: Harnessing Nature to Cure Disease. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2016, 4, 3. 10.1186/s40591-016-0048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G.; Ahn S. N. Structure, Enzymatic Activities, Glycation and Therapeutic Potential of Human Serum Albumin: A Natural Cargo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 979–990. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman J.; Zunszain P. A.; Petitpas I.; Bhattacharya A. A.; Otagiri M.; Curry S. Structural Basis of the Drug-Binding Specificity of Human Serum Albumin. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 353, 38–52. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimizadeh P.; Yang S.; Lim S. I. Albumin: An Emerging Opportunity in Drug Delivery. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2020, 25, 985–995. 10.1007/s12257-019-0512-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czub M. P.; Handing K. B.; Venkataramany B. S.; Cooper D. R.; Shabalin I. G.; Minor W. Albumin-Based Transport of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Mammalian Blood Plasma. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 6847–6862. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A. A.; Curry S.; Franks N. P. Binding of the General Anesthetics Propofol and Halothane to Human Serum Albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 38731–38738. 10.1074/jbc.m005460200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunszain P. A.; Ghuman J.; Komatsu T.; Tsuchida E.; Curry S. Crystal structural analysis of human serum albumin complexed with hemin and fatty acid. BMC Struct. Biol. 2003, 3, 6. 10.1186/1472-6807-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W.; Zhang L.; Okobiah O.; Yang Y.; Wang L.; Zhong D.; Zewail A. H. Ultrafast Solvation Dynamics of Human Serum Albumin: Correlations with Conformational Transitions and Site-Selected Recognition. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 10540–10549. 10.1021/jp055989w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.