Abstract

Introduction

An important challenge for future palliative care delivery is the growing number of people with palliative care needs compared with the limited qualified professional workforce. Existing but underused professional potential can further be optimised. This is certainly the case for social work, a profession that fits well in multidisciplinary palliative care practice but whose capacities remain underused. This study aims to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders (Belgium) by the development of a Palliative Care Program for Social Work (PICASO).

Methods and analysis

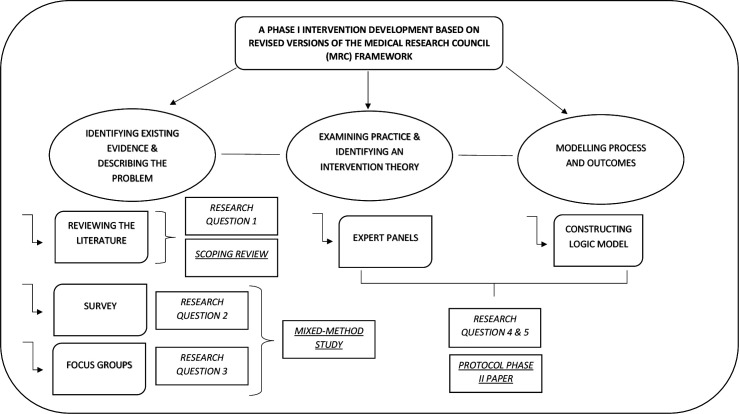

This protocol paper covers the steps of the development of PICASO, which are based on phase I of the Medical Research Council framework. However, additional steps were added to the original framework to include more opportunities for stakeholder involvement. The development of PICASO follows an iterative approach. First, we will identify existing evidence by reviewing the international literature and describe the problem by conducting quantitative and qualitative research among Flemish social workers. Second, we will further examine practice and identify an appropriate intervention theory by means of expert panels. Third, the process and outcomes will be depicted in a logic model.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for this study was given by the KU Leuven Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC) on 14 April 2021 (reference number: G-2020-2247-R2(MIN)). Findings will be disseminated through professional networks, conference presentations and publications in scientific journals.

Keywords: palliative care, social medicine, adult palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study answers a call in the international literature to investigate how the involvement of social workers in palliative care can be optimised.

The outcomes of this study will entail an intervention (Palliative Care Program for Social Work, PICASO) aimed at the optimisation of the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers as well as a list of preconditions for successful social work involvement in Flanders.

The major strengths of this study relate to its participatory approach grounded in adequate stakeholder involvement and the consideration of context during the development process, which assure the embeddedness of PICASO in Flemish social work practice.

A limitation of this protocol is that no concrete steps for evaluating PICASO are described. These steps will be described in a subsequent protocol paper based on phase II of the Medical Research Council framework.

Introduction

Although the delivery and quality of palliative care have significantly improved in the past decades, several challenges remain. One of the most urgent challenges is the growing ageing population1 along with a higher prevalence of chronic conditions in all ages.2 The number of people with palliative care needs is increasing, while the professional workforce that is fully qualified to meet these needs is not growing at the same pace.3–5 It will however not suffice to simply increase the number of professionals in palliative care.6 Instead, it may be more efficient to optimise existing but underused professional and non-professional potential.

This study considers the case of social work in the optimisation of professional potential in palliative care. By social work we refer to the definition set out by the International Federation of Social Workers7 as ‘a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people’. Furthermore, the International Federation of Social Workers suggests that the main role of the social work profession is to engage ‘people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing’. The latter certainly applies to palliative care, which can be defined as a practice that ‘improves the quality of life of patients and that of their families who are facing challenges associated with life-threatening illness, whether physical, psychological, social or spiritual’. Improving the quality of life of caregivers is also an important part of this practice.8 Furthermore, palliative care is a practice for anyone with a life-threatening and incurable condition, without necessarily being in the end-of-life phase.

Generally, social work fits well within the multidisciplinary practice of palliative care. On the one hand, the involvement of social workers in palliative care is linked with better health outcomes for clients.9 10 On the other hand, their involvement is also linked with general savings in healthcare spending at the end of life.11 12 Three additional reasons further illustrate why the involvement of social workers is important for the multidisciplinary practice of palliative care.

First, since ‘person in environment’ is one of the central guiding concepts in social work, social workers aim to positively influence the relationship between clients and their social environment. In palliative care, they build bridges between individual patients, their families, the wider social environment and formal healthcare settings.13–15 This bridging function is an important professional asset because a substantial part of palliative care is being delivered outside of formal healthcare institutions.16 The social dimension of palliative care also remains one of the most underexposed, and professional psychosocial care often becomes ‘more psycho- than social’.17 The inclusion of social workers in the care model is therefore an important step in what Brown and Walter18 called a ‘social model of end-of-life care’.

Second, social work is well suited to highlight the issue of social determinants of health.19 20 Determinants, such as age, ethnicity and socioeconomic position, result in inequalities in access to palliative care and general quality of care at the end of life. Differences in social and cultural capital are often the most important mediators.21–23 It is therefore hypothesised that social workers can contribute to diminishing social inequalities at the end of life.24

Third, although the provision of holistic palliative care was found to be challenging in the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic,25 social workers should have been attributed an expanded role in addressing the consequences of the pandemic for their clients.26 The core values on which social workers base their practices are valuable even in times of health crises and rapid social changes.27

Despite the fact that social workers possess relevant competencies and professional perspectives for making valuable contributions in palliative care, at least three factors are responsible for the underutilisation of their capacities in daily practice.

First, the inadequate role definition of social work in palliative care makes social workers often unaware of the actions that are expected from them. This causes much role ambiguity in daily practice. Additionally, professionals from other disciplines do not know what social work has to offer.28–31 This is a major problem since social workers may be reluctant to take initiative while other professionals may also not involve them in palliative care practice.

Second, role ambiguity is even reinforced by processes that put social workers on the same level as professionals who usually approach palliative care on an individualised basis. On the one hand, the pitfall of therapeutisation of social work practices, which is still relevant two decades after Specht and Courtney’s32 highly cited critical contribution, makes that social workers forget about ‘person in environment’. On the other hand, the medicalisation of palliative care is another process that jeopardises a broad and encompassing perspective on end-of-life problems.33 34 Both processes influence the social work role in palliative care. Hodgson35 suggested that social workers tend to overemphasise psychological issues as a result of working in medicalised settings characterised by an individualised approach to care, rather than focusing on social needs. This may produce role conflicts between social workers and other professionals such as nurses, physicians and psychologists.36 37 Likewise, Lawson38 and Stein and colleagues39 noted that the role of social work in palliative care practice significantly depends on the specific working environment in which they are employed and the model of care in which they operate.

Third, although previous research has shown that social workers tend to have positive attitudes towards palliative care delivery,40–43 this does not imply that they are fully comfortable in taking up their role. Positive attitudes towards palliative care are strongly influenced by personal characteristics, comfort with death and dying and the years of professional experience.40 41 44 Equally important as attitudes are social workers’ level of confidence and competence in palliative care, which were often found to be low. On the one hand, social workers have indicated that their competencies for performing palliative care tasks, that is, addressing social and practical aspects around living with or caring for someone with serious illness and around loss, are often insufficient. On the other hand, they often have little confidence in the usefulness of their social work practices in palliative care.42 45 These are logical consequences of the poor amount of course content on palliative care in social work education programmes,31 46 resulting in the need for additional training after graduation.45

Study rationale: optimising the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers

The contradiction between the theoretical fit of social work in palliative care and its underutilisation in daily practice urges investigation of how the palliative care capacity of social workers can be optimised. With this term, we point to the ability of professionals to perform ‘general and discipline-specific tasks in palliative care delivery’. The palliative care capacity of individual professionals depends on three inter-related factors: their attitudes towards palliative care, their level of confidence in performing general and discipline-specific tasks and their level of competence with which they perform these tasks. These concepts require some further explanation.

First, the attitude—broadly defined as ‘an orientation that is held to be indicative of an underlying value or belief’47—of social workers towards palliative care determines the importance that social workers attach to performing tasks in this field of practice. In this respect, the attitudes of social workers are the first indicators of the actions that social workers will take.

Second, confidence represents a personal judgement influencing whether individuals are willing or not to undertake tasks.48 In this study, confidence refers to the extent to which social workers feel confident towards performing tasks in palliative care. This judgement therefore also determines which actions social workers will take.

Third, competence represents what individuals know about their ability, based on previous experiences of performing tasks.48 In this study, competence refers to the extent to which social workers indicate to possess essential generic competencies—understood in terms of knowledge and skills—to perform typical social work tasks in palliative care practice. Knowledge and skills as elements of competence cover, respectively, the knowledge of social workers on palliative care tasks and the application of this knowledge in practice.

Apart from social workers’ attitudes, confidence and competence, there are also contextual factors that affect the palliative care capacity of individual social workers such as the organisational structure and the care model they are operating in. It is therefore also necessary to look at the preconditions for successful social work involvement to have as complete a picture of the problem as possible.

The optimisation of the palliative care capacity of social workers therefore requires well-developed interventions. It may be useful to start off with a broad examination of the preconditions that would facilitate social work involvement. Furthermore, research could explore how social workers can become more comfortable in palliative care and develop interventions based on these findings. These interventions should not only focus on social workers in specialised palliative care settings, since all social workers, wherever they may function and whatever their specialisation, will sooner or later in their professional careers be confronted with clients facing palliative care needs—broadly defined as the needs following a life-threatening and incurable condition.46 49–51

Study aim: the development of an intervention—Palliative Care Program for Social Work—to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders

This study aims to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders (Belgium) by the development of an intervention—Palliative Care Program for Social Work (PICASO). The study will address the following objectives and associated research questions.

Research objectives

To assess the preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care practice as mentioned in the international literature.

To explore the current palliative care capacity as well as the underused potential of social workers in Flanders.

To examine how the current palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders can be further optimised.

To investigate how the preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care can be realised in the Flemish context.

To develop an intervention, PICASO, to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders.

Research questions

Which preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care are mentioned in the international literature?

What is the current palliative care capacity and underused potential of social workers in Flanders?

How can the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders be further optimised?

How can the preconditions for successful social work involvement be realised in the Flemish context?

Which components should be included in the PICASO in order to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders?

Methods: a phase I intervention development based on revised versions of the Medical Research Council framework

Although this study protocol largely covers the three steps set out in the original 2008 Medical Research Council (MRC) framework52—‘identifying evidence base’, ‘identifying/developing theory’ and ‘modelling process and outcomes’—we slightly adapted the first and second steps. The main argument for adapting these steps is to account for recent critiques on the MRC framework concerning the lack of stakeholder involvement and intervention context. Stakeholder involvement and intervention context are important to account for when designing complex social interventions, most of which are implemented in a diffuse social reality. The coproduction of interventions with relevant stakeholders assures the combination of research evidence and professional expertise, and provides a certain degree of congruence between intervention theory and context.53–55 Furthermore, it also increases the feasibility of the implementation of the intervention.56

More concretely, we used the revised versions of the MRC framework by Bleijenberg and colleagues57 and Moore and colleagues58 to adapt the steps of phase I to the research objectives of this study. Figure 1 illustrates the main ideas of the first and second steps in the original versus the adapted phase I development of the MRC framework.

Figure 1.

The three steps of the phase I development of the Palliative Care Program for Social Work (PICASO).

On the one hand, additional elements were added to the step of ‘identifying evidence base’. Apart from summarising existing evidence in a literature review, it is necessary to understand the problem more thoroughly by examining stakeholders’ perceptions of the subject at hand. This approach combines academic knowledge with intimate stakeholder knowledge.57 58 The intervention development will therefore start by reviewing the international literature as well as examining the characteristics of current social work involvement in Flemish palliative care. Since social workers in Flanders are the target population for the intervention, they will be the main stakeholders to consult in this step.

On the other hand, additional elements were used to adapt the step of ‘identifying/developing theory’. As it is the purpose of PICASO to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders, the intervention development should be embedded in the Flemish context of social work practice as well as possible. The theory that underpins an intervention should relate to the local context of practice.57 58 This approach offers another opportunity for stakeholder involvement, by consulting multiple practice experts who will coproduce an appropriate intervention theory.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient involvement in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Public involvement will however take place in the conduct, reporting and dissemination of the research.

Three iterative steps of developing PICASO

The development process of PICASO contains three steps, which are depicted in figure 1 and further described below. It is important to note that the development process of PICASO, as recommended by the official MRC framework,52 follows an iterative rather than a linear stepwise approach. The whole research trajectory covers the period 2019–2024.

Identifying existing evidence and describing the problem

Reviewing the international literature (research question 1)

By means of a scoping review, existing evidence on the topic will be collected. The research question driving the scoping review is: ‘Which preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care are mentioned in the international literature?’ As mentioned above, these preconditions can be theoretical, organisational or disciplinary.

The scoping review will be performed in three steps. First, three electronic databases (Web of Science, Scopus and PubMed) will be searched for articles published between 2000 and 2020 using the following search string: (Palliative care OR End of life care OR hospice care) AND (social work OR social work practice). Second, a single researcher will screen titles and abstracts and then two independent researchers will screen the full text of the remaining articles. Articles will be included if (1) the full text is available and written in the English language, (2) the main focus of the paper is the involvement of social work in palliative care, and (3) the paper reports on any general preconditions that lead to a successful involvement of social work in palliative care. Finally, the content of the included articles will be thoroughly analysed to answer the research question.

As a result, the scoping review will present a list of preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care. Although this list consists of preconditions reported in the international literature, it can serve as preparatory work in the exploration of the Flemish context in two ways. First, the existing evidence base can help determine the themes for the subsequent survey round and focus group sessions with Flemish social workers. Second, it is recommended that stakeholders with intimate knowledge on the subject at hand inspect the relevant evidence base.58 Therefore, stakeholders participating in subsequent expert panels can assess which preconditions described in the review are applicable to the Flemish case.

Survey with Flemish social workers (research question 2)

A survey with Flemish social workers is a first step in the examination of the problem as perceived by the main stakeholders of this study. Social work is a broad professional working field characterised by multiple theoretical views on the profession’s roles and responsibilities,59 60 and also by different cross-national traditions and professionalisation histories.61 62 Therefore, a review of the international literature should be complemented with an exploration of the local context. This approach assures the embeddedness of PICASO in Flemish social work practice.

The main objective of the survey is to shed light on the current palliative care capacity as well as the underused potential of Flemish social workers, which means that it answers the second research question of this study. The questionnaire will follow a cross-sectional design measuring the following parameters: (1) the attitudes of Flemish social workers towards palliative care practice, (2) the extent to which they are currently performing social work tasks in palliative care practice, and (3) the self-assessment on their competence in performing these tasks. These parameters will be measured for 10 clusters of important social work tasks for which we will use the ‘core competencies framework for palliative care in Europe’ by Hughes and colleagues63 as a main guideline. Other sources of inspiration include the Death Literacy Index,64 the Palliative End-of-Life Care Competency Assessment Tool,65 the Self-assessment of Confidence Scale66 and the Palliative Care Self-efficacy Scale.67 Although we expect varied results for each cluster of social work tasks, three hypotheses, which may coexist, are formulated beforehand:

Social workers regularly perform certain tasks in palliative care that they consider important, but do not always feel competent enough to carry them out.

Social workers do not regularly perform certain tasks in palliative care that they consider important, but do feel competent enough to carry them out.

Social workers consider the performance of certain tasks in palliative care unimportant.

These three hypotheses all have consequences for the later intervention development. A first hypothesis suggests that increasing the level of confidence and/or competence of social workers may be a pathway to optimise their palliative care capacity. Next, a second hypothesis implies that the focus should rather be on making better use of existing potential of social workers. Finally, a third hypothesis hints that it may be worthwhile to improve the attitudes of social workers towards palliative care. Since it is evident that multiple hypotheses are applicable, it is likely that the intervention will consist of multiple strategies to optimise the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers.

Social workers who (1) have achieved a social work degree from an official educational institution and (2) may come into contact with palliative care while exercising their profession will be eligible to fill out the survey questionnaire. Some (umbrella) organisations in Flanders, of which we believe that they are likely to employ social workers meeting these criteria, will be purposefully selected. The organisations will then be contacted and requested to distribute an email for participation containing an anonymous online survey link on QUALTRICS to their affiliated social workers. With regard to the organisations for which the population of social workers is known, the questionnaire will be distributed to the total subpopulation. With regard to the organisations for which the population of social workers is not known, a rather pragmatic sampling strategy is set up. For the social services of the health insurance companies, the three largest companies will be selected and contacted independently. They will then be asked to distribute the questionnaire to their affiliated social workers. Despite the fact that the actual population is not known, this approach ensures that we still approach a total population sampling. For the nursing homes, a random sample will be drawn on the organisational level. It is expected to select 80 nursing homes (roughly 10% of the total number of nursing homes in Flanders). The selected nursing homes will then be contacted to distribute the questionnaire to their affiliated social workers. Table 1 depicts the sampling strategy for each of the selected (umbrella) organisations. The population number n should be considered as an estimate. It can, however, be precisely determined during the survey distribution and will be reported exactly in a future results paper.

Table 1.

Sampling strategy

| Selected (umbrella) organisation | n (estimate) | Sampling strategy |

| Home care services | 1200 | Total population sampling |

| Community health centres | 35 | Total population sampling |

| Social services of the hospitals | 1200 | Total population sampling |

| Social services of the health insurance companies | 490* | Total population sampling |

| Nursing homes | Unknown | Simple random sampling (organisational level) |

*Three largest companies.

The survey will run for a predetermined period of time. During this period, the response rate will be maximised by implementing various elements (such as sending reminders) from Dillman’s68 total design method.

Survey data will be transported to SPSS Statistics (V.28.0), after which they will be analysed in terms of descriptive analysis and reported based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. This analysis provides an initial picture of the field as well as a first indication for potential improvement, further explored in subsequent focus group sessions.

Focus groups with Flemish social workers (research question 3)

Following the survey round, focus group sessions will provide deeper insights into the survey results and, more specifically, the consequences of these results for social work practice. While the survey is about exploring the current palliative care capacity and underused potential of Flemish social workers, the focus group sessions form a means to examine how the current situation can be improved. This step thus addresses the third research question of this study.

The questioning of the focus group sessions will therefore largely depend on the hypotheses in the survey round. Depending on the survey scores, participants in the focus groups will be asked to discuss how the current situation can be improved. Three main questions are possible here. First, if survey respondents would indicate to perform certain tasks, although not feeling competent enough to perform them, it will be asked how the level of confidence and/or competence for these tasks could be increased. Second, if survey respondents would indicate to not perform certain tasks, although feeling competent enough to perform them, it will be asked how to make better use of existing potential for performing these tasks. Third, if survey respondents would indicate to not consider certain tasks as important, it will be asked how the attitudes of social workers towards palliative care could be improved. Since multiple hypotheses can apply to different tasks in the survey questionnaire, a mixture of these questions is possible. Apart from the main questions, additional questions focusing on other preconditions of successful social work involvement in palliative care will also be included in the focus group sessions.

Participants for the focus groups will be recruited during the survey round and by additional calls. At the end of the survey questionnaire, respondent social workers will be asked whether they want to participate in subsequent focus groups. Furthermore, additional calls for participation will be sent out via the (umbrella) organisations selected in the survey round. The eligibility criteria for participation in the survey are therefore also applicable for the focus group sessions. When organising the focus groups, we will take the distribution of social workers across the various organisational types into account.

The format of the focus group sessions will be as follows: all focus groups will last approximately 2 hours, take place in a predefined setting and will be attended by two researchers and a maximum number of eight participating social workers per group. Five focus groups are estimated to be sufficient for reaching data saturation. First, the main results of the survey will be presented by the researchers, after which participants can discuss them in an in-depth way. Subsequently, participants will be asked to share their ideas on how the current palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers can be further optimised. The topic list guiding this discussion will largely depend on the results of the survey round. First, if social workers indicate to perform certain tasks when they actually feel not competent to perform them, it will be asked whether this is due to a lack of confidence and/or competence. Furthermore, it will be asked how their confidence and/or competence in palliative care can be improved. Second, if social workers indicate to feel competent to perform certain tasks when they actually do not perform them in practice, it will be asked why they are not performing them. Furthermore, it will be asked how existing potential can be better used. Third, if social workers indicate to have negative attitudes towards the performance of certain palliative care tasks, it will be asked how these attitudes can be improved.

Data of all focus groups will be audio recorded, anonymously transcribed and analysed by two independent researchers using NVivo V.12. Data will be inductively as well as deductively analysed following the steps of the framework method set out by Ritchie and Spencer.69 As recommended by Parker and Tritter,70 sufficient attention will be paid to the interaction between the individual and the group level in the data analysis. Results will be reported based on the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist.

Examining practice and identifying an intervention theory

Expert panels (research questions 4 and 5)

The main objectives of the expert panels are to further examine the current practice of social work in palliative care in Flanders, adjust the intervention theory to this practice and coproduce the components of PICASO. This research activity helps to ensure that the study finds the right balance between academic theory and stakeholder-led theories.

The format and composition of the expert panels will be as follows. Generally, all expert panels will last approximately 2 hours, take place in a predefined setting and will be attended by two researchers and a maximum number of eight experts per panel. The composition of the expert panels will consist of various field experts from multiple disciplines (such as social workers, healthcare professionals in palliative care, education managers of bachelor’s and master’s social work programmes, policy makers and patient organisation representatives). Participants will be recruited by sending an invitation mail to various stakeholder organisations (such as the Flemish social care services of the health insurance organisations; the Flemish services for family care and home care; the professional association of hospital social workers in Flanders; multiple social work educational institutions and services in palliative care in Flanders).

In the first part of each expert panel, the researchers will present the list of preconditions for successful social work involvement in palliative care as identified in the scoping review. The experts will be asked whether and how these preconditions apply to the Flemish context and which recommendations can be formulated to optimise social work involvement in palliative care in Flanders. These insights form the basis in answering the fourth research question of this study. The researchers will guide this process as they will have scrutinised several forms of grey literature in preparation for the expert panels, such as practical guidelines for social workers, educational material, policy documents and national registries.

In the second part, the researchers will present the survey and focus group results, after which the experts can further discuss the implications for the intervention theory of PICASO. More concretely, they will be able to propose essential intervention components based on desired outcomes through ‘backcasting’ methods. Backcasting involves ‘the development of normative scenarios aimed at exploring the feasibility and implications of achieving certain desired end-points’.71 These steps should answer the final research question of this study: ‘Which components should be included in PICASO in order to optimise the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers?’

Modelling process and outcomes

The survey round, focus group sessions and expert panels should result in a thorough exploration of the local context, in which the intervention will be embedded. According to Bleijenberg and colleagues,57 these insights can now be synthesised, after which they can be used in modelling the intervention components.

Logic models have often been criticised for their simplistic presentation of interventions53 but are still a useful method to depict the chain of reasoning between intervention input and outcomes. Furthermore, they are a good means to illustrate the pathways within interventions.72 Nonetheless, apart from depicting intended pathways, it is recommended to consider alternative scenarios to account for human volition in the logic model.73 These alternative scenarios are preferably based on ‘a range of assumptions about how actors within the system will respond to intervention’.58

The modelling process of PICASO therefore will therefore consist of constructing a logic model and setting out a limited number of alternative scenarios. Following the main assumptions in the normalisation process theory (NPT) by May and colleagues,74 it is important to consider the possible pathways in the implementation and integration of an intervention. The inclusion of alternative scenarios to the logic model may furthermore serve as a concrete starting point in identifying the priorities for a later phase II evaluation.58

The outcomes of this phase I development study will entail an intervention (PICASO) aimed at the optimisation of the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers as well as a list of preconditions for successful social work involvement in Flanders. These outcomes will be further described in an upcoming protocol paper that will initiate the steps of the phase II feasibility and pilot trial.

Discussion

This protocol paper describes the development of an intervention, PICASO, that aims to optimise the palliative care capacity of social workers in Flanders, Belgium. The study is based on the recent revisions of the phase I MRC framework by Bleijenberg and colleagues57 and Moore and colleagues58 to include sufficient opportunities for stakeholder participation and to increase the sensitivity for the intervention context.

The relevance and social value of this study are twofold. On the one hand, the delivery of good-quality palliative care is linked to cost savings for healthcare services,11 which makes the optimisation of professional potential even more relevant. Furthermore, based on the findings by Reese and Raymer,9 we hypothesise that the involvement of social workers in palliative care can produce positive outcomes for clients and relatives such as increased quality of life. As social workers bring ‘person in environment’ perspectives to the table, they may challenge the medicalised model and inform a more holistic and social model of palliative care. Given these arguments, this study answers a call in the international literature to increase the involvement of social workers in multidisciplinary palliative care delivery.28 37 39 On the other hand, thus far, to our knowledge, no peer-reviewed records cover the case of social work in palliative care in Flanders. This study is therefore also a first step in increasing the involvement of social work in Flanders.

The aspect of stakeholder involvement is a first major strength of this study. Many interventions that are currently being developed are afterwards (meaning after a full clinical trial) being labelled as ‘research waste’ due to a poor development process.57 Therefore, it is necessary that the development of an intervention follows a participatory approach supporting its fit into daily practice before evaluation in a pilot or full clinical trial.75 76 This study is relevant for Flemish social work practice since it involves stakeholders throughout the development phase—from describing the problem to modelling process and outcomes. In this respect, PICASO will be a quintessentially coproduced intervention.

A closely related second strength relates to the attempt to take the broader context of the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers into account. This approach also ensures that the chance of producing research waste is minimised. Although PICASO is predominantly aimed at disciplinary preconditions for successful social work involvement, this study accounts for other preconditions as well by making recommendations for fulfilling these preconditions in the Flemish context. The underlying rationale for taking these into account is that the intervention can only work well if it is embedded in a context that is positive towards social work involvement in palliative care. As Moore and colleagues58 argued, intervention developers have to ‘focus carefully on constructing a clear understanding of current system functioning, before considering the impact of introducing change’. Moreover, it also aligns with the NPT, which emphasises the importance of understanding the context in which a new intervention is to be implemented.

A third strength relates to this study’s potential relevance beyond Flanders. The steps described in this protocol can serve as the starting point for future research in regions or countries that have a similar organisation of the social work profession. Yet, even for regions or countries where social work is organised very differently, the research steps of this study can serve as inspiration for the optimisation of social workers’ palliative care capacity. As the scoping review provides a list of the preconditions that need to be fulfilled for successful social work involvement, it can be scrutinised according to local practice needs. Furthermore, the other steps outlined in this protocol paper can be adopted and adapted to the local context.

A first limitation of this protocol is that no concrete evaluation steps are described because the intervention has yet to be developed. Moreover, the participatory research approach in which we involve as many stakeholders as possible makes it difficult to formulate any intervention scenarios beforehand. The planning of the feasibility and pilot trial for evaluating PICASO, which will be based on phase II of the MRC framework, will therefore start with a presentation of the main research outcomes of the phase I development in a second study protocol. These research outcomes will include the logic model of PICASO and the preconditions for successful social work involvement in Flanders and the corresponding recommendations mentioned in the expert panels. Intervention content will be reported based on the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist.

A second limitation relates to the question of this study’s representativeness. As there is no professional social work association in Flanders and central lists of social workers are not available, we cannot use population data to check the representativeness of our sample. Furthermore, also the response rate for the survey research will be difficult to exactly determine, since organisations’ lists are sometimes ambiguous (eg, other non-social worker professionals in the social sector may also be on the lists). Instead, we argue that this three-stage study (survey round, focus group round and expert panels) in which we use a mixed-methods approach is the best way to paint a realistic picture when answering the research questions. This study will form the basis of a phase II feasibility and pilot trial to evaluate the intervention in terms of its acceptability, feasibility, validity and effectiveness. The intended impact of PICASO after phase I and II will be an optimisation of the palliative care capacity of Flemish social workers, which will ultimately contribute to a better social work involvement in multidisciplinary palliative care delivery.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for all activities described in this study protocol was given by the KU Leuven Social and Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC) on 14 April 2021 (reference number: G-2020-2247-R2(MIN)).

We will provide both written and verbal information to all participants of the studies described in this study protocol. Written informed consent is required from all participants prior to data collection.

Findings of each of the studies mentioned will be disseminated through professional networks, conference presentations and publication in scientific journals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BT, KiH and AD drafted the initial manuscript. All authors (BT, KiH, CVA, JC, KoH, AD) participated in creating the concept of the paper and in discussions about earlier versions, and critically revised the different versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study is part of the project ‘CAPACITY: Flanders Project to Develop Capacity in Palliative Care Across Society’, a collaboration between the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Ghent University and the University of Leuven, Belgium. This study is supported by a grant from the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (file number: S002219N).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Morin L, Aubry R, Frova L, et al. Estimating the need for palliative care at the population level: a cross-national study in 12 countries. Palliat Med 2017;31:526–36. 10.1177/0269216316671280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:102. 10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connolly M, Ryan K, Charnley K. Developing a palliative care competence framework for health and social care professionals: the experience in the Republic of Ireland. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:237–42. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliat Care 2017;10:117822421668888. 10.1177/1178224216688887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selman L, Robinson V, Klass L, et al. Improving confidence and competence of healthcare professionals in end-of-life care: an evaluation of the 'Transforming End of Life Care' course at an acute hospital trust. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:231–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. Future of the palliative care workforce: preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med 2017;130:113–4. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Federation of Social Workers . Global Definiton of social work, 2014. Available: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- 8.World Health Organization . Palliative care: key facts, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

- 9.Reese DJ, Raymer M. Relationships between social work involvement and hospice outcomes: results of the National hospice social work survey. Soc Work 2004;49:415–22. 10.1093/sw/49.3.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, et al. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist 2008;48:485–94. 10.1093/geront/48.4.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson LC, Usher B, Spragens L, et al. Clinical and economic impact of palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:340–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stilos Kalliopi (Kalli), Takahashi D, Nolen AE. The role of the social worker at the end of life: paving the way in an academic Hospital quality improvement initiative. The British Journal of Social Work 2021;51:246–58. 10.1093/bjsw/bcaa096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holloway M. Dying old in the 21st century: a neglected issue for social work. International Social Work 2009;52:713–25. 10.1177/0020872809342640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig SL, Muskat B, Bouncers MB. Bouncers, brokers, and glue: the self-described roles of social workers in urban hospitals. Health Soc Work 2013;38:7–16. 10.1093/hsw/hls064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon F, Fraser L, McDermott F. Sitting with silence: Hospital social work interventions for dying patients and their families. Soc Work Health Care 2019;58:444–58. 10.1080/00981389.2019.1586027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pesut B, Duggleby W, Warner G, et al. Volunteer navigation partnerships: Piloting a compassionate community approach to early palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2017;17:2. 10.1186/s12904-017-0210-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellehear A. Health-Promoting palliative care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75–82. 10.1080/713685967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown L, Walter T. Towards a social model of end-of-life care. Br J Soc Work 2014;44:2375–90. 10.1093/bjsw/bct087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akyar I, Dionne-Odom JN, Ozcan M, et al. Needs assessment for Turkish family caregivers of older persons with cancer: first-phase results of adapting an early palliative care model. J Palliat Med 2019;22:1065–74. 10.1089/jpm.2018.0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholas DB, Jones C, McPherson B, et al. Examining professional competencies for emerging and novice social workers in health care. Soc Work Health Care 2019;58:596–611. 10.1080/00981389.2019.1601650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burt J. Back to basics: researching equity in palliative care. Palliat Med 2012;26:5–6. 10.1177/0269216311431370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies JM, Sleeman KE, Leniz J, et al. Socioeconomic position and use of healthcare in the last year of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002782. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JM, DiGiacomo M, Currow DC, et al. Dying in the margins: understanding palliative care and socioeconomic deprivation in the developed world. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42:105–18. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.10.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne M. Inequalities, end-of-life care and social work. Prog Palliat Care 2010;18:221–7. 10.1179/096992610X12624290277187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costantini M, Sleeman KE, Peruselli C, et al. Response and role of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national telephone survey of hospices in Italy. Palliat Med 2020;34:889–95. 10.1177/0269216320920780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raftery C, Lewis E, Cardona M. The crucial role of nurses and social workers in initiating end-of-life communication to reduce overtreatment in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontology 2020;66:427–30. 10.1159/000509103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swinford E, Galucia N, Morrow-Howell N. Applying Gerontological social work perspectives to the coronavirus pandemic. J Gerontol Soc Work 2020;63:513–23. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1766628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosma H, Johnston M, Cadell S, et al. Creating social work competencies for practice in hospice palliative care. Palliat Med 2010;24:79–87. 10.1177/0269216309346596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glajchen M, Berkman C, Otis-Green S, et al. Defining core competencies for Generalist-Level palliative social work. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:886–92. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Head B, Peters B, Middleton A, et al. Results of a nationwide hospice and palliative care social work job analysis. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2019;15:16–33. 10.1080/15524256.2019.1577326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein GL, Berkman C, Pollak B. What are social work students being taught about palliative care? Palliat Support Care 2019;17:536–41. 10.1017/S1478951518001049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Specht H, Courtney ME. Unfaithful angels: how social work has abandoned its mission. New York: Free Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Floriani CA, Schramm FR. Routinization and medicalization of palliative care: losses, gains and challenges. Palliat Support Care 2012;10:295–303. 10.1017/S1478951511001039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Payne M. Developments in end-of-life and palliative care social work international issues. International Social Work 2009;52:513. 10.1177/00208728091042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodgson J. Working together - a multidisciplinary concern. In: Parker J, ed. Aspects of social work and palliative care. Mark Allen Group, 2005: 170. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier DE, Beresford L. Social workers advocate for a seat at palliative care table. J Palliat Med 2008;11:10–14. 10.1089/jpm.2008.9996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reese DJ. Interdisciplinary perceptions of the social work role in hospice: building upon the classic Kulys and Davis study. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2011;7:383–406. 10.1080/15524256.2011.623474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawson R. Home and Hospital; hospice and palliative care: how the environment impacts the social work role. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2007;3:3–17. 10.1300/J457v03n02_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein GL, Cagle JG, Christ GH. Social work involvement in advance care planning: findings from a large survey of social workers in hospice and palliative care settings. J Palliat Med 2017;20:253–9. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker ME. Knowledge and attitudes of health care social workers regarding advance directives. Soc Work Health Care 2000;32:61–74. 10.1300/j010v32n02_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutheil IA, Heyman JC. A social work perspective: attitudes toward end-of-life planning. Soc Work Health Care 2011;50:763–74. 10.1080/00981389.2011.595479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leichtentritt RD. Beyond favourable attitudes to end-of-life rights: the experiences of Israeli health care social workers. Br J Soc Work 2011;41:1459–76. 10.1093/bjsw/bcr006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C-W, Chan CLW, Chow AYM. Social workers' involvement in advance care planning: a systematic narrative review. BMC Palliat Care 2017;17:5. 10.1186/s12904-017-0218-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simons K, Park-Lee E. Social Work Students’ Comfort With End-of-Life Care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2009;5:34–48. 10.1080/15524250903173884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisenfluh SM, Csikai EL. Professional and educational needs of hospice and palliative care social workers. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2013;9:58–73. 10.1080/15524256.2012.758604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berkman C, Stein GL. Palliative and end-of-life care in the masters of social work curriculum. Palliat Support Care 2018;16:180–8. 10.1017/S147895151700013X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall G, Scott J. A dictionary of sociology. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford university press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart J, O'Halloran C, Barton JR, et al. Clarifying the concepts of confidence and competence to produce appropriate self-evaluation measurement scales. Med Educ 2000;34:903–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becker JE. Oncology social workers' attitudes toward hospice care and referral behavior. Health Soc Work 2004;29:36–45. 10.1093/hsw/29.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murty SA, Gilmore K, Richards KA, et al. Using a LISTSERV™ to develop a community of practice in end-of-life, hospice, and palliative care social work. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2012;8:77–101. 10.1080/15524256.2011.652857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reith M, Payne M. Social work in end-of-life and palliative care. Policy Press, 2009: 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:979–83. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fletcher A, Jamal F, Moore G, et al. Realist complex intervention science: applying realist principles across all phases of the medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. Evaluation 2016;22:286–303. 10.1177/1356389016652743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med 2018;16:95. 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore GF, Evans RE. What theory, for whom and in which context? Reflections on the application of theory in the development and evaluation of complex population health interventions. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:132–5. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen HT. The bottom-up approach to integrative validity: a new perspective for program evaluation. Eval Program Plann 2010;33:205–14. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bleijenberg N, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Trappenburg JCA, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste by optimizing the development of complex interventions: enriching the development phase of the medical Research Council (MRC) framework. Int J Nurs Stud 2018;79:86–93. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore GF, Evans RE, Hawkins J, et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation 2019;25:23–45. 10.1177/1356389018803219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Payne M. What is professional social work? Rev. 2nd edn. Bristol: Polity press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Staniforth B, Fouché C, O'Brien M. Still doing what we do: defining social work in the 21st century. J Soc Work 2011;11:191–208. 10.1177/1468017310386697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lorenz W. Perspectives on European social work: from the birth of the nation state to the impact of globalisation. Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss I, Welbourne P. Social work as a profession: a comparative cross-national perspective. Birmingham: Venture Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hughes S, Firth P, Oliviere D. Core competencies for palliative care social work in Europe: an EAPC white paper – Part 2. Eur J Palliative Care 2015;22:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leonard R, Noonan K, Horsfall D, et al. Death literacy index: a report on its development and implementation. Western Sydney University, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Northern Ireland Practice and Educational Council (NIPEC) . Palliative End-of-Life-Care competency assessment tool. Northern Ireland Practice and Educational Council (NIPEC), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weber M, Schmiedel S, Nauck F, et al. Knowledge and attitude of final - year medical students in Germany towards palliative care - an interinstitutional questionnaire-based study. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:19. 10.1186/1472-684X-10-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phillips J, Salamonson Y, Davidson PM. An instrument to assess nurses' and care assistants' self-efficacy to provide a palliative approach to older people in residential aged care: a validation study. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1096–100. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys : the total design method. New York: Wiley, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman B, Burgess R, eds. Analyzing qualitative data, 1994: 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parker A, Tritter J. Focus group method and methodology: current practice and recent debate. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 2006;29:23–37. 10.1080/01406720500537304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robinson J. Future subjunctive: backcasting as social learning. Futures 2003;35:839–56. 10.1016/S0016-3287(03)00039-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baxter SK, Blank L, Woods HB, et al. Using logic model methods in systematic review synthesis: describing complex pathways in referral management interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:62. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bonell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, et al. Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:2299–306. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.May CR, Mair F, Finch T, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci 2009;4:29. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Glasgow RE, Green LW, Taylor MV, et al. An evidence integration triangle for aligning science with policy and practice. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:646–54. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, et al. Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ 2010;341:c3852. 10.1136/bmj.c3852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.