Abstract

Since the discovery of interferon-tau (IFNT) over 30 years ago as the trophectodermal cytokine responsible for the maintenance of the maternal corpus luteum (CL) in ruminants, exhaustive studies have been conducted to identify genes and gene products related to CL maintenance. Recent studies have provided evidence that although CL maintenance, with the up- and down-regulation of IFNT, is important, its regulatory role in the endometrial expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) is far more important for conditioning the uterine environment for successful conceptus implantation and thereafter. This review initially describes the mammalian implantation process, briefly but focuses on recent findings, as there appears to be a common phenomenon during early to mid-pregnancy among mammalian species.

Keywords: Interferon-tau, Mammals, Pregnancy recognition, Ruminants

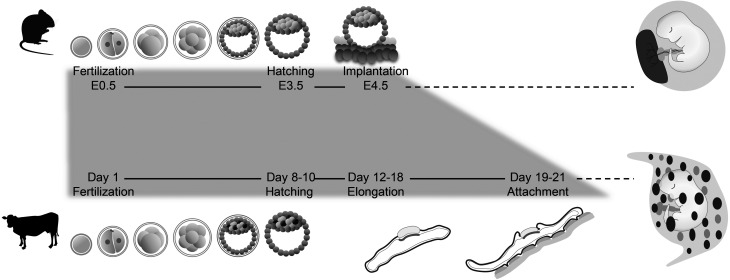

In mammals, implantation is a critical step for a successful pregnancy and the completion of sequential events, such as maternal uterine modification, conceptus (embryo plus extra-embryonic membrane) development, and attachment/invasion to the endometrium, followed by placental formation, must be tightly controlled temporally and spatially. In fact, conceptus and uterine adaptation must be well synchronized and coordinated through physical, cellular, and biochemical communication. From blastocyst development to placental formation, detailed physiological events and their time courses as well as placental structures, differ among mammalian species; however, the basic processes of implantation and the requirement for placental formation are similar among eutherians [1,2,3,4,5] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pre-implantation periods in mice and cows. Implantation in mice—an important laboratory animal model—and in cattle, domestic animal, are illustrated. Although the basic processes of implantation and placentation are similar among mammalian species, the details of these events, their time courses, and placental structures are species-specific. Notably, soon after hatching, the blastocyst implants into the maternal endometrium in mice, while the bovine conceptus elongates prior to its attachment to the uterine epithelium. In both cases, trophoblast cells cover the entire surface of the uterine lumen and this is followed by placentation.

In mice, fertilized eggs reach the uterine lumen on day 3.5 as floating blastocysts. Blastocysts undergo rapid implantation with apposition and attachment to the uterine epithelium, followed by invagination of the uterine endometrium, forming the implantation chamber—a characteristic of eccentric implantation [1]. As blastocyst invagination progresses, trophectodermal cells begin to cover the surface of the uterine lumen. In ruminants, such as bovine, ovine, and caprine species, blastocysts are formed several days after fertilization, as in other mammals, but they do not attach to the uterine epithelium for several days. Trophoblast elongation is one of the unique features of ruminant conceptus development. The blastocyst remains spherical in shape and unattached to the uterine epithelium for several days before its elongation, which begins around day 12–13 (day 0 = day of estrus). Around day 14, the conceptus becomes an ovoid structure and then begins to elongate rapidly. Around day 20, when conceptus elongation slows down, bovine conceptus starts to attach to the endometrial epithelium [6, 7]. At this point, trophoblast cells start to cover the entire uterine lumen, including uterine caruncles, from which placental structures unique to ruminants develop [8] (Fig. 1). Thus, sequential events during conceptus implantation in the maternal endometrium differ in rodents and ruminants, while the events in which the uterine lumen is entirely covered with trophectodermal cells are similar, if not the same, in these mammals.

In mammals, maintenance of corpus luteum (CL) function, from which the continued secretion of progesterone (P4) is ensured, is required for the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. P4 is involved in several uterine functions; however, the mechanisms by which CL is maintained for P4 production differ among mammalian species. In humans, luteolysis is prevented by chorionic gonadotropin (CG), a hormone produced following the implantation of trophoblast cells [9]. CG binds to the luteinizing hormone/CG receptor, modulating the uterine environment and ensuring that the CL continuously secretes P4 [10]. In rodents, CL is maintained through the release of copulation-induced pituitary prolactin (PRL) surges [11]. PRL surges are believed to convert CL to the CL of pregnancy and lead to the secretion of sufficient P4 to support pregnancy [12]. In ruminants, interferon-tau (IFNT) is produced by trophoblast cells of the elongating conceptus during the peri-implantation period [13, 14]. IFNT prevents luteolysis by attenuating prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) secretion from the uterine endometrium, resulting in continued secretion of P4. The attenuation of PGF2α results from the down-regulation of estrogen receptor and estrogen-induced oxytocin receptor expression [15, 16]. IFNT is now well known as the key factor for maternal recognition of pregnancy in ruminants [17,18,19,20,21].

It was reported that homogenates of day 14–16 conceptuses, but not those of days 21–23, extended CL life span, suggesting that these conceptuses actively produced the anti-luteolytic factor trophoblastin [22]. Using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Godin et al. (1982) identified a group of proteins responsible for CL maintenance and named the protein as ovine trophoblast protein-1 (oTP-1) [17]. A similar protein was also identified in bovines [13]. In 1987, through the analysis of cDNA and amino acid sequences, Imakawa et al. identified that the substance was an interferon [18], and later named it interferon τ (tau) because it was derived from the embryonic trophectoderm [21]. More than 30 years after its discovery, IFNT remains a key player in the mechanism of pregnancy establishment in ruminants and has the potential to act beyond pregnancy recognition.

Trophectodermal IFNT is a Product of a Gene Family

Interferons (IFN) are cytokines with antiviral activity induced by a viral infection or double-stranded RNAs. They are divided into three groups: type I, II, and III IFNs [23], and type I IFNs are further divided into the following subfamilies: IFN-alpha (IFNA), beta (IFNB), delta (IFND), epsilon (IFNE), kappa (IFNK), tau (IFNT), omega (IFNW), and zeta (IFNZ) [24, 25]. While IFNW is conserved in most mammals, IFNT is found only in ruminants and is a relatively new IFN that is thought to have derived from IFNW approximately 36 million years ago [26, 27]. The amino acid sequence of IFNT shows high similarity (~70%) with IFNW, moderate similarity (~50%) with IFNA, and low similarity (~25%) with IFNB [28, 29].

All IFN-type genes are located on chromosome 8 in domestic cattle [25]. At least 13 IFNA, 6 IFNB, and 24 IFNW genes have been found in the bovine genome, and although the exact number of IFNT genes has not been determined, as many as 40 IFNT sequences have been suggested to exist [25]. However, a comprehensive analysis of transcripts using peri-implantation bovine conceptuses revealed that among numerous IFNT genes, only two, IFNT1 and IFNTc1, are predominantly expressed in utero during the peri-implantation period [30, 31]. In sheep, multiple IFNT genes are present as well, even though only a single gene (IFNT-o10) accounts for up to 75% of the total mRNA expressed during the equivalent period of early pregnancy [32].

It remains unclear why many duplicated genes have arisen in the IFNT gene family. Although the regulatory mechanisms of these genes have not been definitively elucidated [30], no clear differences in transcriptional regulation, function, or downstream gene targets have been found [33]. Similarly, the exact reason for the presence of multiple IFNT genes and how specific each IFNT variant functions, is still unknown, it could be a molecular mechanism that ensures the maximum level of IFNT production during early pregnancy. Alternatively, the presence of multiple genes ensures IFNT production even when major IFNT genes could be dysfunctional. The presence of multiple IFNT genes suggests that their expression in ruminants must be critical and needs to be ensured during early pregnancy. The evolution of IFNs, including IFNT, has been well described in more detail elsewhere [23, 29].

Transcriptional Regulation of IFNT Gene

a) Up-regulation

IFNT exhibits structural and functional similarities to type I IFNs [34]. Type I IFNs, induced by a viral infection, include several members such as IFNA, IFNW, and IFNB, which are produced by leukocytes and fibroblasts, respectively. IFN gamma (IFNG), a type II IFN, is produced by T cells and Natural Killer (NK) cells following mitogen treatment. IFNT, which has a high degree of structural similarity to IFNW, consists of four cysteine residues that are well conserved across the type I IFN gene family. However, IFNT is not secreted by blood cells, strongly suggesting that IFNT is regulated differently from other type I IFNs.

One of the differences between IFNT and other type I IFNs is that presence and expression of IFNT are unique to ruminant trophoblast cells. The coding sequences of IFNT genes are similar to those of IFNW, but the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR regions differ. The ancestral IFNT gene is predicted to have arisen by the insertion of a novel chorionic membrane-specific 5′ UTR (promoter/enhancer) and 3′ UTR into the gene regulatory region of IFNW [23]. The first 400 bases upstream of the IFNT gene transcription start site are unique to the IFNT gene, and no apparent virus-inducible transcriptional elements are found in this region [28, 35].

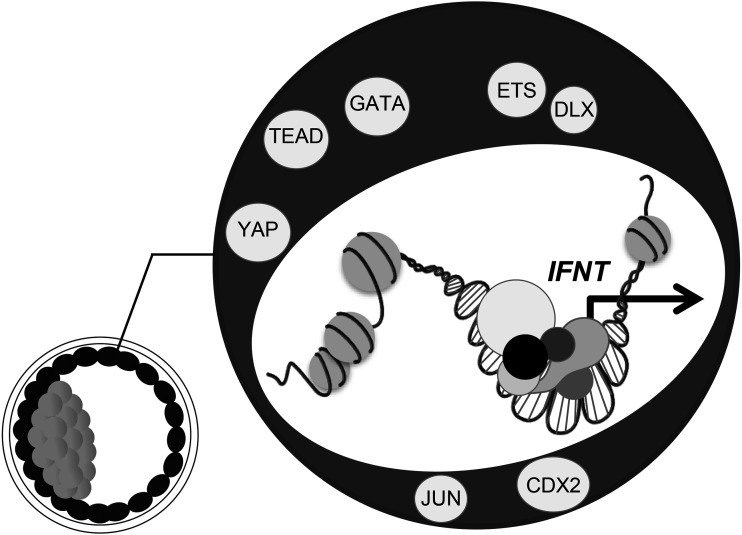

Numerous transcription factor binding sites exist in the regulatory region of the IFNT gene, and several transcription factors have been found to regulate its transcription [36]. IFNT is intrinsically produced by the ruminant trophectoderm (TE) and no other cell types that produce IFNT have been identified to date. However, in non-trophoblastic cells, overexpression of the transcription factor CDX2 can induce endogenous IFNT gene expression in Mardin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells, suggesting that CDX2 is responsible for trophoblast cell-specific regulation of IFNT expression [37]. Together with CDX2 regulation, IFNT gene expression is epigenetically regulated [37, 38]. The binding sites of the transcription factors ETS2 and DLX3 are well conserved in several IFNT genes, and they work together to promote IFNT expression, making them common regulators of IFNT genes [39, 40]. In addition to these main transcription factors, the coactivators CREB binding protein (CREBBP) [41] and p300 [42] have also been reported to be involved in the regulation of IFNT transcription.

b) Down-regulation

Coinciding with conceptus elongation, IFNT expression increases dramatically for several days, and then rapidly declines as the TE attaches to the maternal uterine epithelium [43, 44]. The exact reason and mechanism for this down-regulation have not been definitively elucidated, but it is presumed that IFNT expression needs to decline soon after pregnancy recognition and the initiation of conceptus attachment to the uterine epithelium.

Transcription factors, such as Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4) [45] and eomesodermin (EOMES) [46], have been reported to suppress IFNT gene expression. These factors are known to play an important role in embryonic development in mice. Oct4–/– embryos die at the time of implantation due to failure to form the inner cell mass (ICM) [47]. Eomes-deficient mouse embryos are arrested at the blastocyst stage, suggesting that EOMES may be required for trophoblast stem cell development [48]. The downregulation of IFNT transcription by EOMES has been demonstrated through the use of in vitro co-culture systems of trophoblasts and endometrial epithelial cells [46]. The transcription cofactor Yes-associated protein (YAP) and the TEA domain family transcription factor (TEAD) are major components of the Hippo signaling pathway and play an essential role in cell fate specification of TE and ICM [49, 50, 52, 53]. It has also been shown that the transcription cofactor YAP inhibits IFNT expression by altering the localization of TEAD2 and TEAD4 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [51].

Epigenetic regulation, such as histone modification and DNA methylation, also regulates IFNT gene expression by altering chromatin conformation. Indeed, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using ovine conceptuses (days 14–20) revealed that histone proteins wrapped in the upstream region of the IFNT gene are highly acetylated on days 14 and 16, followed by a decrease in acetylation after conceptus attachment to the uterus with a simultaneous increase in histone methylation [38]. In addition, Nojima et al. examined the methylation status of the upstream region of the IFNT gene using non-IFNT-producing cells (endometrium, leukocytes) and IFNT-producing day 14 (high IFNT production) and day 20 (low IFNT production) conceptuses. They reported that changes in the degree of methylation may be one of the major mechanisms leading to the down-regulation or silencing of ovine IFNT transcription [52]. These epigenetic modifications probably ensure trophoblast specificity of IFNT expression. Indeed, the upstream regions of ovine IFNT genes in non-trophoblastic tissues, such as the uterine endometrium and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), were highly methylated [52]. Thus, in addition to transcription factor expression, epigenetic modifications are required for trophoblast-specific IFNT expression temporally and spatially.

Together, these findings indicate that IFNT genes use multiple transcriptional mechanisms to up-regulate and later down-regulate their transcription. The reason why ruminants acquired the IFNT gene has not yet been elucidated, nor has its gene duplication made it possible for massive IFNT production during this limited pre-attachment period. It is generally accepted that the expression of the IFNT gene is finely regulated by not only various transcription factors but also by epigenetic mechanisms. For more information on the regulation of IFNT expression, please refer to the excellent review [36].

Common Transcription Factors are Involved in Both Trophectodermal Cell Development and IFNT Gene Transcription

Several transcription factors play essential roles in the development and maintenance of mammalian trophoblast cells, and in particular, CDX2 has been extensively studied during early embryonic development in mice. In fact, CDX2 is required for correct cell fate specification and TE differentiation in mouse blastocysts. Cdx2 homozygous mutant embryos die around the time of implantation [53]. In cattle, CDX2 mRNA is detected from the germinal vesicle stage to the expanded blastocyst stage, and CDX2 protein is restricted to the TE in blastocysts [2]. ETS2 expression is restricted to trophoblasts in the early post-implantation stages and is also essential for trophoblast development in mice [54, 55]. In bovines, ETS2 expression begins in trophoblasts at the spherical stage [56].

GATA2 and GATA3 also play key roles in the development and function of mouse trophoblast cells [57, 58]. Although the GATA binding site is found only in the upstream region of IFNTc1, one of the two bovine IFNT genes expressed by the pre-implantation conceptus in utero, they can also induce the transcriptional activity of IFNT genes in non-trophoblast cells and regulate the expression of IFNT as well as other TE factors [59,60,61]. In the human choriocarcinoma JEG3 cell line, GATA2 failed to exert its effect, probably because JEG3 cells express abundant endogenous GATA2 and GATA3. In addition, single-cell analysis revealed that there are four subpopulations of TEs and that the genes strongly expressed in all of them include IFNT, CDX2, GATA2, and GATA3 [62]. In addition to CDX2, GATA expression in trophoblasts can provide an adequate microenvironment that supports IFNT expression [59]. Evidence has accumulated that the transcription factors required for trophectodermal lineage specification are also associated with ruminant-specific IFNT gene transcription.

These findings suggest that although the time course of implantation processes, mechanisms of pregnancy recognition/CL maintenance, and placental formation differ among mammalian species, a group of transcription factors that function in TE is generally conserved (Fig. 2). Therefore, understanding the TE-specific factors associated with the regulatory mechanism of IFNT gene expression may help us identify common mechanisms required for pregnancy establishment in ruminant ungulates as well as in other mammals. In other words, the identification of molecular and cellular mechanisms associated with the temporal and spatial expression of IFNT may provide an alternative method to identify what promotes TE cell development and the regulation of their associated gene expression.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional regulation of IFNT gene. Although IFNT is ruminant-specific, most factors important for trophoblast development are conserved in mammals, and these factors, such as CDX2, ETS2, and GATA are also involved in the regulation of IFNT gene expression. Mammals had existed long before the appearance of the first ruminants with IFNT. As such, ruminants did not acquire new genes to control IFNT genes but were able to use genes that were already functioning in trophoblasts.

Use of IFNT to Improve Pregnancy Success

Since the discovery of IFNT, attempts have been made to utilize IFNT to improve pregnancy rates. At the time of its discovery, a recombinant protein was not available, and thus, recombinant IFNA, another type I IFN, was initially tested for its efficacy in extending inter-estrous intervals or improving pregnancy rates. IFNA administration inhibits oxytocin-induced PGF2α induction and prolongs luteal lifespan [63,64,65]. However, it has not been definitively shown to date whether IFN administration compensates for inadequate conceptus production of IFNT in utero. Recombinant IFNT administration was reported to inhibit luteal regression and extend the luteal phase for only a few days [66, 67]. Following a series of experiments involving the administration of recombinant IFNT proteins with limited success, a new methodology was developed to administer IFNT; the use of trophoblastic vesicles which produce intrinsic IFNT. Trophoblastic vesicles were obtained by cutting elongated conceptuses into small pieces and culturing them. These vesicles produce IFNT and are intended to compensate for IFNT. It has been reported that the co-transfer of trophoblastic vesicles obtained from 14-day blastocysts improves the conception rate in cattle [68]. In addition, it has also been reported that co-transfer of trophoblastic vesicles from pregnant day 14 bovine and day 11–13 sheep embryos maintained the CL [69], and that administration of trophoblastic vesicles from pregnant day 7–8 bovine embryos into the uterine horn prolonged the estrous cycle in approximately half of the examined cows [70].

Co-transfer of trophoblastic vesicles derived from IVF embryos has also been reported to improve pregnancy rates in bovines [71, 72]. Although this treatment was very effective in relatively early pregnancies (days 26–43), there was no significant difference in mid-pregnancy (days 38–73) or final delivery outcomes (days 280–299) [71]. In other words, these findings suggest that IFNT supplementation may improve conception rates from pregnancy recognition to the early stage of gestation, the first 4–5 weeks, but factors other than IFNT are involved in the maintenance of pregnancy after 5 weeks of pregnancy.

Embryo transfer (ET) following artificial insemination (AI) is used to improve the conception rate of repeat-breeder cows [73, 74]. In such cows, improvement in conception rates was observed in about half of the cases [73, 75]. The combination of AI and ET doubled the chance of pregnancy resulting from the effectiveness of IFNT supplementation [75]. However, there is concern that twin pregnancies would increase since embryos could develop from both AI and ET. It was found that IFNT is produced by parthenogenetic embryos as well as by in vivo or in vitro produced embryos and trophoblastic vesicles [76], and their use was expected to increase due to their ease of preparation and cost. Thus, the use of parthenogenetic embryos, which do not become embryos but produce IFNT, is also under investigation. The co-transfer of parthenogenetic embryos enhances maternal recognition of pregnancy and promotes the viability of poor-quality embryos until day 40 of gestation [77]. In addition, it has also been reported that AI plus parthenogenic embryos may be beneficial for improving maternal recognition of pregnancy in repeat-breeder cattle while avoiding twin generation [78]. These findings further emphasize that IFNT is important for the recognition and establishment of pregnancy, especially in the early stages of gestation, and further testing is needed for practical applications to improve pregnancy rates in the future.

Common Maternal Responses Exist during the Early Mid-pregnancy in Mammals

IFNT not only prevents CL regression but also modulates endometrial gene expression as the pregnancy to proceed. For example, IFNT induces the expression of several chemokines in uterine endometrial tissues such as chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) and 9 (CXCL9) [79, 80]. CXCL10 attracts immune cells, especially NK cells, to the implantation site by acting through the CXCL10 receptor, CXCR3, which regulates TE cell migration and integrin expression [81, 82].

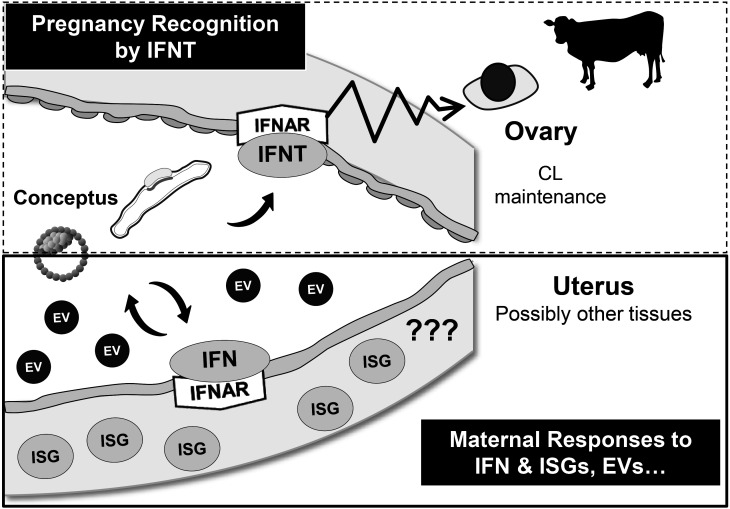

In addition to these chemokines, IFNT induces the expression of numerous interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in the maternal uterus [83,84,85]. Although the detection of ISGs expression in the uterus is well documented [85,86,87], elevated ISGs expression has been reported in various tissues other than the uterus, such as blood cells, luteal tissue, and liver during pregnancy [88,89,90,91,92,93,94]. Since the expression of type I IFN and ISGs during the implantation period has also been found in mice and humans [95, 96], it is likely that these factors play important roles in the maternal uterine environment necessary for conceptus implantation processes and/or the consequence of conceptus implantation into the uterine endometrium. In fact, the immune function of type I IFN and ISGs during pregnancy has been recognized in the human placenta [97].

When compared to non-pregnant ewes, expression of another ISG protein, MX, in pregnant ewes was higher in PBMCs up to 30 days after AI [98]. In addition, it was also reported that although ISG15 mRNA decreased after day 25 of pregnancy, its protein remained in the endometrium until day 40 of pregnancy in sheep [99]. In cows, ISG15 expression is up-regulated in the CL on day 16 of gestation and is still detectable on day 60 [90]. In mouse uteri, ISG15 expression is detectable on embryonic day 3.5 (E3.5) and increases by day 9.5 (E9.5) [95]. In the human placenta, ISG15 is expressed from the first to the second trimester of pregnancy, suggesting that ISG15 is associated with placental development, fetal growth, and/or potential defense mechanisms against infections [100]. These results suggest that ISGs are important not only for the pre-implantation period but also thereafter until mid-pregnancy. These observations are consistent with the fact that ISG expression persists long after IFNT expression subsides. It has been suggested that another type I IFN, such as IFNA or IFNW, could be present, which also up-regulates ISG expression. However, the presence and effects of type I IFN have not been definitively elucidated. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms associated with ISG regulation toward the mid-gestation.

The presence of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in the uterine lumen has been previously reported [101,102,103,104]. In addition to the direct release of IFNT into the uterine lumen, IFNT has been detected in EVs produced by bovine conceptus [105]. The IFNT produced is confined to the uterine lumen [15, 106], although a few studies have reported that IFNT exists in the uterine vein [107]. The presence of IFNT in uterine EVs suggests that such EVs can circulate, and the effect of IFNT may be more widespread. The release of EVs from various tissues is a common phenomenon, and EVs have been detected in the uteri of non-ruminant animals [108,109,110,111]. These results provide evidence that although EVs contain IFNT in ruminants, they may also contain other substances that play a common role in pregnancy establishment in other or all mammals. In cattle, the effects of EVs due to other factors other than IFNT have been reported [112, 113].

Although the role of ISGs during the period following IFNT expression has not yet been well characterized, their expression could be used as a marker for early pregnancy detection in ruminants. Recently, we identified ISGs expression in bovine tissues, such as the cervical and vaginal mucosa, from which a less invasive pregnancy diagnosis was developed. [114, 115]. It appears that the expression of ISGs is seen in humans, mice, and cows, and future validation is needed to understand the species-specific types as well as those common across mammalian species. ISGs induced by type I IFNs are diverse, comprising several hundred types, and are potentially involved in a variety of phenomena during the implantation-placentation processes. In humans, IFN plays no role in pregnancy recognition; however, type I IFN signaling is required for normal pregnancy progression [116, 117]. Although the substances and mechanisms of pregnancy recognition may differ among mammalian species, the existence of type I IFN and ISGs during pregnancy across various mammalian species suggests that the expression of various ISGs and possibly EV release may be a common feature necessary for the establishment and/or maintenance of pregnancy (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ruminant-specific pregnancy recognition and potential factors required for pregnancy establishment in ruminants and beyond. CL maintenance by IFNT is specific to ruminants (dotted line box). However, the expression of type I IFN from the embryo and responses by the uterus, such as interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) expression, are similar among mammals, and ISGs and possibly EVs play a common role in successful pregnancy in these animals (solid-line box).

Conclusion

Although the expression of IFNT is required for the maintenance of CL function in ruminants, the expression of ISGs in the uteri, as well as other tissues during early to mid-pregnancy, appears to be common in mammals. Therefore, elucidation of the molecular mechanisms associated with ISGs expression and understanding of ISGs and even EV’s functions after the first weeks of the pregnancy recognition period is crucial, if pregnancy rates are to be improved in mammalian species.

Conflict of interests

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS KAKENHI 20K15644 (to H.B.) and 16H02584 (to K.I.).

References

- 1.Dey SK, Lim H, Das SK, Reese J, Paria BC, Daikoku T, Wang H. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev 2004; 25: 341–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuijk EW, Du Puy L, Van Tol HT, Oei CH, Haagsman HP, Colenbrander B, Roelen BA. Differences in early lineage segregation between mammals. Dev Dyn 2008; 237: 918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg DK, Smith CS, Pearton DJ, Wells DN, Broadhurst R, Donnison M, Pfeffer PL. Trophectoderm lineage determination in cattle. Dev Cell 2011; 20: 244–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazer FW, Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Wu G. Comparative aspects of implantation. Reproduction 2009; 138: 195–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akizawa H, Saito S, Kohri N, Furukawa E, Hayashi Y, Bai H, Nagano M, Yanagawa Y, Tsukahara H, Takahashi M, Kagawa S, Kawahara-Miki R, Kobayashi H, Kono T, Kawahara M. Deciphering two rounds of cell lineage segregations during bovine preimplantation development. FASEB J 2021; 35: e21904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang MC. Development of bovine blastocyst with a note on implantation. Anat Rec 1952; 113: 143–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenstein JS, Murray RW, Foley RC. Observations on the morphogenesis and histochemistry of the bovine preattachment placenta between 16 and 33 days of gestation. Anat Rec 1958; 132: 321–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillomot M. Cellular interactions during implantation in domestic ruminants. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 1995; 49: 39–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hearn JP, Webley GE, Gidley-Baird AA. Chorionic gonadotrophin and embryo-maternal recognition during the peri-implantation period in primates. J Reprod Fertil 1991; 92: 497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameo P, Srisuparp S, Strakova Z, Fazleabas AT. Chorionic gonadotropin and uterine dialogue in the primate. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2004; 2: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soares MJ, Faria TN, Roby KF, Deb S. Pregnancy and the prolactin family of hormones: coordination of anterior pituitary, uterine, and placental expression. Endocr Rev 1991; 12: 402–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunnet JW, Freeman ME. The mating-induced release of prolactin: a unique neuroendocrine response. Endocr Rev 1983; 4: 44–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartol FF, Roberts RM, Bazer FW, Lewis GS, Godkin JD, Thatcher WW. Characterization of proteins produced in vitro by periattachment bovine conceptuses. Biol Reprod 1985; 32: 681–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farin CE, Imakawa K, Hansen TR, McDonnell JJ, Murphy CN, Farin PW, Roberts RM. Expression of trophoblastic interferon genes in sheep and cattle. Biol Reprod 1990; 43: 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spencer TE, Becker WC, George P, Mirando MA, Ogle TF, Bazer FW. Ovine interferon-tau regulates expression of endometrial receptors for estrogen and oxytocin but not progesterone. Biol Reprod 1995; 53: 732–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer TE, Bazer FW. Ovine interferon tau suppresses transcription of the estrogen receptor and oxytocin receptor genes in the ovine endometrium. Endocrinology 1996; 137: 1144–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godkin JD, Bazer FW, Moffatt J, Sessions F, Roberts RM. Purification and properties of a major, low molecular weight protein released by the trophoblast of sheep blastocysts at day 13-21. J Reprod Fertil 1982; 65: 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imakawa K, Anthony RV, Kazemi M, Marotti KR, Polites HG, Roberts RM. Interferon-like sequence of ovine trophoblast protein secreted by embryonic trophectoderm. Nature 1987; 330: 377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart HJ, McCann SHE, Barker PJ, Lee KE, Lamming GE, Flint APF. Interferon sequence homology and receptor binding activity of ovine trophoblast antiluteolytic protein. J Endocrinol 1987; 115: R13–R15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charpigny G, Reinaud P, Huet JC, Guillomot M, Charlier M, Pernollet JC, Martal J. High homology between a trophoblastic protein (trophoblastin) isolated from ovine embryo and α-interferons. FEBS Lett 1988; 228: 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts RM, Cross JC, Leaman DW. Interferons as hormones of pregnancy. Endocr Rev 1992; 13: 432–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martal J, Lacroix MC, Loudes C, Saunier M, Wintenberger-Torrès S. Trophoblastin, an antiluteolytic protein present in early pregnancy in sheep. J Reprod Fertil 1979; 56: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ealy AD, Wooldridge LK. The evolution of interferon-tau. Reproduction 2017; 154: F1–F10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause CD, Pestka S. Evolution of the Class 2 cytokines and receptors, and discovery of new friends and relatives. Pharmacol Ther 2005; 106: 299–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker AM, Roberts RM. Characterization of the bovine type I IFN locus: rearrangements, expansions, and novel subfamilies. BMC Genomics 2009; 10: 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hughes AL. The evolution of the type I interferon gene family in mammals. J Mol Evol 1995; 41: 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leaman DW, Roberts RM. Genes for the trophoblast interferons in sheep, goat, and musk ox and distribution of related genes among mammals. J Interferon Res 1992; 12: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leaman DW, Cross JC, Roberts RM. Genes for the trophoblast interferons and their distribution among mammals. Reprod Fertil Dev 1992; 4: 349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts RM, Liu L, Guo Q, Leaman D, Bixby J. The evolution of the type I interferons. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1998; 18: 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai T, Nakagawa S, Kim MS, Bai H, Bai R, Li J, Min KS, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. Transcriptional regulation of two conceptus interferon tau genes expressed in Japanese black cattle during peri-implantation period. PLoS One 2013; 8: e80427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MS, Min KS, Seong HH, Kim CL, Jeon IS, Kim SW, Imakawa K. Regulation of conceptus interferon-tau gene subtypes expressed in the uterus during the peri-implantation period of cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 2018; 190: 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda-Minehata F, Katsumura M, Kijima S, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Different levels of ovine interferon-tau gene expressions are regulated through the short promoter region including Ets-2 binding site. Mol Reprod Dev 2005; 72: 7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusama K, Bai R, Nakamura K, Okada S, Yasuda J, Imakawa K. Endometrial factors similarly induced by IFNT2 and IFNTc1 through transcription factor FOXS1. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0171858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farin CE, Imakawa K, Roberts RM. In situ localization of mRNA for the interferon, ovine trophoblast protein-1, during early embryonic development of the sheep. Mol Endocrinol 1989; 3: 1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nephew KP, Whaley AE, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Differential expression of distinct mRNAs for ovine trophoblast protein-1 and related sheep type I interferons. Biol Reprod 1993; 48: 768–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezashi T, Imakawa K. Transcriptional control of IFNT expression. Reproduction 2017; 154: F21–F31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakurai T, Sakamoto A, Muroi Y, Bai H, Nagaoka K, Tamura K, Takahashi T, Hashizume K, Sakatani M, Takahashi M, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Induction of endogenous interferon tau gene transcription by CDX2 and high acetylation in bovine nontrophoblast cells. Biol Reprod 2009; 80: 1223–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakurai T, Bai H, Konno T, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Function of a transcription factor CDX2 beyond its trophectoderm lineage specification. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 5873–5881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ezashi T, Ealy AD, Ostrowski MC, Roberts RM. Control of interferon-tau gene expression by Ets-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 7882–7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ezashi T, Das P, Gupta R, Walker A, Roberts RM. The role of homeobox protein distal-less 3 and its interaction with ETS2 in regulating bovine interferon-tau gene expression-synergistic transcriptional activation with ETS2. Biol Reprod 2008; 79: 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu N, Takahashi Y, Matsuda F, Sakai S, Christenson RK, Imakawa K. Coactivator CBP in the regulation of conceptus IFNtau gene transcription. Mol Reprod Dev 2003; 65: 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Das P, Ezashi T, Gupta R, Roberts RM. Combinatorial roles of protein kinase A, Ets2, and 3′,5′-cyclic-adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein-binding protein/p300 in the transcriptional control of interferon-tau expression in a trophoblast cell line. Mol Endocrinol 2008; 22: 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helmer SD, Hansen PJ, Anthony RV, Thatcher WW, Bazer FW, Roberts RM. Identification of bovine trophoblast protein-1, a secretory protein immunologically related to ovine trophoblast protein-1. J Reprod Fertil 1987; 79: 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ealy AD, Larson SF, Liu L, Alexenko AP, Winkelman GL, Kubisch HM, Bixby JA, Roberts RM. Polymorphic forms of expressed bovine interferon-tau genes: relative transcript abundance during early placental development, promoter sequences of genes and biological activity of protein products. Endocrinology 2001; 142: 2906–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim MS, Sakurai T, Bai H, Bai R, Sato D, Nagaoka K, Chang KT, Godkin JD, Min KS, Imakawa K. Presence of transcription factor OCT4 limits interferon-tau expression during the pre-attachment period in sheep. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2013; 26: 638–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakurai T, Bai H, Bai R, Sato D, Arai M, Okuda K, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Down-regulation of interferon tau gene transcription with a transcription factor, EOMES. Mol Reprod Dev 2013; 80: 371–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Schöler H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 1998; 95: 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russ AP, Wattler S, Colledge WH, Aparicio SA, Carlton MB, Pearce JJ, Barton SC, Surani MA, Ryan K, Nehls MC, Wilson V, Evans MJ. Eomesodermin is required for mouse trophoblast development and mesoderm formation. Nature 2000; 404: 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishioka N, Inoue K, Adachi K, Kiyonari H, Ota M, Ralston A, Yabuta N, Hirahara S, Stephenson RO, Ogonuki N, Makita R, Kurihara H, Morin-Kensicki EM, Nojima H, Rossant J, Nakao K, Niwa H, Sasaki H. The Hippo signaling pathway components Lats and Yap pattern Tead4 activity to distinguish mouse trophectoderm from inner cell mass. Dev Cell 2009; 16: 398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerri C, McCarthy A, Alanis-Lobato G, Demtschenko A, Bruneau A, Loubersac S, Fogarty NME, Hampshire D, Elder K, Snell P, Christie L, David L, Van de Velde H, Fouladi-Nashta AA, Niakan KK. Initiation of a conserved trophectoderm program in human, cow and mouse embryos. Nature 2020; 587: 443–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kusama K, Bai R, Sakurai T, Bai H, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. A transcriptional cofactor YAP regulates IFNT expression via transcription factor TEAD in bovine conceptuses. Domest Anim Endocrinol 2016; 57: 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nojima H, Nagaoka K, Christenson RK, Shiota K, Imakawa K. Increase in DNA methylation downregulates conceptus interferon-tau gene expression. Mol Reprod Dev 2004; 67: 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strumpf D, Mao CA, Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Chawengsaksophak K, Beck F, Rossant J. Cdx2 is required for correct cell fate specification and differentiation of trophectoderm in the mouse blastocyst. Development 2005; 132: 2093–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto H, Flannery ML, Kupriyanov S, Pearce J, McKercher SR, Henkel GW, Maki RA, Werb Z, Oshima RG. Defective trophoblast function in mice with a targeted mutation of Ets2. Genes Dev 1998; 12: 1315–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Georgiades P, Rossant J. Ets2 is necessary in trophoblast for normal embryonic anteroposterior axis development. Development 2006; 133: 1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Degrelle SA, Campion E, Cabau C, Piumi F, Reinaud P, Richard C, Renard JP, Hue I. Molecular evidence for a critical period in mural trophoblast development in bovine blastocysts. Dev Biol 2005; 288: 448–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Home P, Ray S, Dutta D, Bronshteyn I, Larson M, Paul S. GATA3 is selectively expressed in the trophectoderm of peri-implantation embryo and directly regulates Cdx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 28729–28737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ralston A, Cox BJ, Nishioka N, Sasaki H, Chea E, Rugg-Gunn P, Guo G, Robson P, Draper JS, Rossant J. Gata3 regulates trophoblast development downstream of Tead4 and in parallel to Cdx2. Development 2010; 137: 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bai H, Sakurai T, Kim MS, Muroi Y, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Nakajima H, Takahashi M, Nagaoka K, Imakawa K. Involvement of GATA transcription factors in the regulation of endogenous bovine interferon-tau gene transcription. Mol Reprod Dev 2009; 76: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bai H, Sakurai T, Someya Y, Konno T, Ideta A, Aoyagi Y, Imakawa K. Regulation of trophoblast-specific factors by GATA2 and GATA3 in bovine trophoblast CT-1 cells. J Reprod Dev 2011; 57: 518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bai H, Sakurai T, Godkin JD, Imakawa K. Expression and potential role of GATA factors in trophoblast development. J Reprod Dev 2013; 59: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Negrón-Pérez VM, Zhang Y, Hansen PJ. Single-cell gene expression of the bovine blastocyst. Reproduction 2017; 154: 627–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nephew KP, McClure KE, Day ML, Xie S, Roberts RM, Pope WF. Effects of intramuscular administration of recombinant bovine interferon-alpha I1 during the period of maternal recognition of pregnancy. J Anim Sci 1990; 68: 2766–2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Plante C, Thatcher WW, Hansen PJ. Alteration of oestrous cycle length, ovarian function and oxytocin-induced release of prostaglandin F-2 alpha by intrauterine and intramuscular administration of recombinant bovine interferon-alpha to cows. J Reprod Fertil 1991; 93: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parkinson TJ, Lamming GE, Flint AP, Jenner LJ. Administration of recombinant bovine interferon-alpha I at the time of maternal recognition of pregnancy inhibits prostaglandin F2 alpha secretion and causes luteal maintenance in cyclic ewes. J Reprod Fertil 1992; 94: 489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyer MD, Hansen PJ, Thatcher WW, Drost M, Badinga L, Roberts RM, Li J, Ott TL, Bazer FW. Extension of corpus luteum lifespan and reduction of uterine secretion of prostaglandin F2 alpha of cows in response to recombinant interferon-tau. J Dairy Sci 1995; 78: 1921–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bott RC, Ashley RL, Henkes LE, Antoniazzi AQ, Bruemmer JE, Niswender GD, Bazer FW, Spencer TE, Smirnova NP, Anthony RV, Hansen TR. Uterine vein infusion of interferon tau (IFNT) extends luteal life span in ewes. Biol Reprod 2010; 82: 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heyman Y, Chesné P, Chupin D, Ménézo Y. Improvement of survival rate of frozen cattle blastocysts after transfer with trophoblastic vesicles. Theriogenology 1987; 27: 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heyman Y, Camous S, Fèvre J, Méziou W, Martal J. Maintenance of the corpus luteum after uterine transfer of trophoblastic vesicles to cyclic cows and ewes. J Reprod Fertil 1984; 70: 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nagai K, Sata R, Takahashi H, Okano A, Kawashima C, Miyamoto A, Geshi M. Production of trophoblastic vesicles derived from Day 7 and 8 blastocysts of in vitro origin and the effect of intrauterine transfer on the interestrous intervals in Japanese black heifers. J Reprod Dev 2009; 55: 454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hashiyada Y, Okada M, Imai K. Transition of the pregnancy rate of bisected bovine embryos after co-transfer with trophoblastic vesicles prepared from in vivo-cultured in vitro-fertilized embryos. J Reprod Dev 2005; 51: 749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mori M, Kasa S, Hattori MA, Ueda S. Development of a single bovine embryo improved by co-culture with trophoblastic vesicles in vitamin-supplemented medium. J Reprod Dev 2012; 58: 717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dochi O, Takahashi K, Hirai T, Hayakawa H, Tanisawa M, Yamamoto Y, Koyama H. The use of embryo transfer to produce pregnancies in repeat-breeding dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2008; 69: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Canu S, Boland M, Lloyd GM, Newman M, Christie MF, May PJ, Christley RM, Smith RF, Dobson H. Predisposition to repeat breeding in UK cattle and success of artificial insemination alone or in combination with embryo transfer. Vet Rec 2010; 167: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yaginuma H, Funeshima N, Tanikawa N, Miyamura M, Tsuchiya H, Noguchi T, Iwata H, Kuwayama T, Shirasuna K, Hamano S. Improvement of fertility in repeat breeder dairy cattle by embryo transfer following artificial insemination: possibility of interferon tau replenishment effect. J Reprod Dev 2019; 65: 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kubisch HM, Rasmussen TA, Johnson KM. Interferon-tau in bovine blastocysts following parthenogenetic activation of oocytes: pattern of secretion and polymorphism in expressed mRNA sequences. Mol Reprod Dev 2003; 64: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hirayama H, Moriyasu S, Kageyama S, Sawai K, Takahashi H, Geshi M, Fujii T, Koyama T, Koyama K, Miyamoto A, Matsui M, Minamihashi A. Enhancement of maternal recognition of pregnancy with parthenogenetic embryos in bovine embryo transfer. Theriogenology 2014; 81: 1108–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Funeshima N, Noguchi T, Onizawa Y, Yaginuma H, Miyamura M, Tsuchiya H, Iwata H, Kuwayama T, Hamano S, Shirasuna K. The transfer of parthenogenetic embryos following artificial insemination in cows can enhance pregnancy recognition via the secretion of interferon tau. J Reprod Dev 2019; 65: 443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagaoka K, Sakai A, Nojima H, Suda Y, Yokomizo Y, Imakawa K, Sakai S, Christenson RK. Expression of a chemokine, IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 kDa, is stimulated by IFN-τ in the ovine endometrium. Biol Reprod 2003; 68: 1413–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Imakawa K, Imai M, Sakai A, Suzuki M, Nagaoka K, Sakai S, Lee SR, Chang KT, Echternkamp SE, Christenson RK. Regulation of conceptus adhesion by endometrial CXC chemokines during the implantation period in sheep. Mol Reprod Dev 2006; 73: 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nagaoka K, Nojima H, Watanabe F, Chang KT, Christenson RK, Sakai S, Imakawa K. Regulation of blastocyst migration, apposition, and initial adhesion by a chemokine, interferon γ-inducible protein 10 kDa (IP-10), during early gestation. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 29048–29056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Imakawa K, Nagaoka K, Nojima H, Hara Y, Christenson RK. Changes in immune cell distribution and IL-10 production are regulated through endometrial IP-10 expression in the goat uterus. Am J Reprod Immunol 2005; 53: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hansen TR, Sinedino LDP, Spencer TE. Paracrine and endocrine actions of interferon tau (IFNT). Reproduction 2017; 154: F45–F59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Forde N, Lonergan P. Transcriptomic analysis of the bovine endometrium: What is required to establish uterine receptivity to implantation in cattle? J Reprod Dev 2012; 58: 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chaney HL, Grose LF, Charpigny G, Behura SK, Sheldon IM, Cronin JG, Lonergan P, Spencer TE, Mathew DJ. Conceptus-induced, interferon tau-dependent gene expression in bovine endometrial epithelial and stromal cells. Biol Reprod 2021; 104: 669–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Johnson GA, Austin KJ, Collins AM, Murdoch WJ, Hansen TR. Endometrial ISG17 mRNA and a related mRNA are induced by interferon-tau and localized to glandular epithelial and stromal cells from pregnant cows. Endocrine 1999; 10: 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Austin KJ, Carr AL, Pru JK, Hearne CE, George EL, Belden EL, Hansen TR. Localization of ISG15 and conjugated proteins in bovine endometrium using immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 967–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han H, Austin KJ, Rempel LA, Hansen TR. Low blood ISG15 mRNA and progesterone levels are predictive of non-pregnant dairy cows. J Endocrinol 2006; 191: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gifford CA, Racicot K, Clark DS, Austin KJ, Hansen TR, Lucy MC, Davies CJ, Ott TL. Regulation of interferon-stimulated genes in peripheral blood leukocytes in pregnant and bred, nonpregnant dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2007; 90: 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang L, Wang XL, Wan PC, Zhang LY, Wu Y, Tang DW, Zeng SM. Up-regulation of expression of interferon-stimulated gene 15 in the bovine corpus luteum during early pregnancy. J Dairy Sci 2010; 93: 1000–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Magata F, Shirasuna K, Strüve K, Herzog K, Shimizu T, Bollwein H, Miyamoto A. Gene expressions in the persistent corpus luteum of postpartum dairy cows: distinct profiles from the corpora lutea of the estrous cycle and pregnancy. J Reprod Dev 2012; 58: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meyerholz MM, Mense K, Knaack H, Sandra O, Schmicke M. Pregnancy-induced ISG-15 and MX-1 gene expression is detected in the liver of Holstein-Friesian heifers during late peri-implantation period. Reprod Domest Anim 2016; 51: 175–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruhmann B, Giller K, Hankele AK, Ulbrich SE, Schmicke M. Interferon-τ induced gene expression in bovine hepatocytes during early pregnancy. Theriogenology 2017; 104: 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang L, Li N, Zhang L, Bai J, Zhao Z, Wang Y. Effects of early pregnancy on expression of interferon-stimulated gene 15, STAT1, OAS1, MX1, and IP-10 in ovine liver. Anim Sci J 2020; 91: e13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Austin KJ, Bany BM, Belden EL, Rempel LA, Cross JC, Hansen TR. Interferon-stimulated gene-15 (Isg15) expression is up-regulated in the mouse uterus in response to the implanting conceptus. Endocrinology 2003; 144: 3107–3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bebington C, Bell SC, Doherty FJ, Fazleabas AT, Fleming SD. Localization of ubiquitin and ubiquitin cross-reactive protein in human and baboon endometrium and decidua during the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy. Biol Reprod 1999; 60: 920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ding J, Maxwell A, Adzibolosu N, Hu A, You Y, Liao A, Mor G. Mechanisms of immune regulation by the placenta: Role of type I interferon and interferon-stimulated genes signaling during pregnancy. Immunol Rev 2022; 308: 9–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yankey SJ, Hicks BA, Carnahan KG, Assiri AM, Sinor SJ, Kodali K, Stellflug JN, Stellflug JN, Ott TL. Expression of the antiviral protein Mx in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of pregnant and bred, non-pregnant ewes. J Endocrinol 2001; 170: R7–R11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Joyce MM, White FJ, Burghardt RC, Muñiz JJ, Spencer TE, Bazer FW, Johnson GA. Interferon stimulated gene 15 conjugates to endometrial cytosolic proteins and is expressed at the uterine-placental interface throughout pregnancy in sheep. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schanz A, Baston-Büst DM, Heiss C, Beyer IM, Krüssel JS, Hess AP. Interferon stimulated gene 15 expression at the human embryo-maternal interface. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014; 290: 783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ruiz-González I, Xu J, Wang X, Burghardt RC, Dunlap KA, Bazer FW. Exosomes, endogenous retroviruses and toll-like receptors: pregnancy recognition in ewes. Reproduction 2015; 149: 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Burns GW, Brooks KE, Spencer TE. Extracellular vesicles originate from the conceptus and uterus during early pregnancy in sheep. Biol Reprod 2016; 94: 56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Burns GW, Brooks KE, O’Neil EV, Hagen DE, Behura SK, Spencer TE. Progesterone effects on extracellular vesicles in the sheep uterus. Biol Reprod 2018; 98: 612–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.O’Neil EV, Burns GW, Ferreira CR, Spencer TE. Characterization and regulation of extracellular vesicles in the lumen of the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 2020; 102: 1020–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nakamura K, Kusama K, Bai R, Sakurai T, Isuzugawa K, Godkin JD, Suda Y, Imakawa K. Induction of IFNT-stimulated genes by conceptus-derived exosomes during the attachment period. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0158278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Godkin JD, Bazer FW, Thatcher WW, Roberts RM. Proteins released by cultured Day 15-16 conceptuses prolong luteal maintenance when introduced into the uterine lumen of cyclic ewes. J Reprod Fertil 1984; 71: 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Romero JJ, Antoniazzi AQ, Nett TM, Ashley RL, Webb BT, Smirnova NP, Bott RC, Bruemmer JE, Bazer FW, Anthony RV, Hansen TR. Temporal release, paracrine and endocrine actions of ovine conceptus-derived interferon-tau during early regnancy. Biol Reprod 2015; 93: 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Almiñana C, Rudolf Vegas A, Tekin M, Hassan M, Uzbekov R, Fröhlich T, Bollwein H, Bauersachs S. Isolation and characterization of equine uterine extracellular vesicles: A comparative methodological study. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hua R, Liu Q, Lian W, Gao D, Huang C, Lei M. Transcriptome regulation of extracellular vesicles derived from porcine uterine flushing fluids during peri-implantation on endometrial epithelial cells and embryonic trophoblast cells. Gene 2022; 822: 146337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Greening DW, Nguyen HP, Elgass K, Simpson RJ, Salamonsen LA. Human endometrial exosomes contain hormone-specific cargo modulating trophoblast adhesive capacity: Insights into endometrial-embryo interactions. Biol Reprod 2016; 94: 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Giacomini E, Scotti GM, Vanni VS, Lazarevic D, Makieva S, Privitera L, Signorelli S, Cantone L, Bollati V, Murdica V, Tonon G, Papaleo E, Candiani M, Viganò P. Global transcriptomic changes occur in uterine fluid-derived extracellular vesicles during the endometrial window for embryo implantation. Hum Reprod 2021; 36: 2249–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pavani KC, Meese T, Pascottini OB, Guan X, Lin X, Peelman L, Hamacher J, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Deforce D, Boel A, Heindryckx B, Tilleman K, Van Soom A, Gadella BM, Hendrix A, Smits K. Hatching is modulated by microRNA-378a-3p derived from extracellular vesicles secreted by blastocysts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022; 119: e2122708119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nakamura K, Kusama K, Hori M, Imakawa K. The effect of bta-miR-26b in intrauterine extracellular vesicles on maternal immune system during the implantation period. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021; 573: 100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kunii H, Koyama K, Ito T, Suzuki T, Balboula AZ, Shirozu T, Bai H, Nagano M, Kawahara M, Takahashi M. Hot topic: Pregnancy-induced expression of interferon-stimulated genes in the cervical and vaginal mucosal membranes. J Dairy Sci 2018; 101: 8396–8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kunii H, Kubo T, Asaoka N, Balboula AZ, Hamaguchi Y, Shimasaki T, Bai H, Kawahara M, Kobayashi H, Ogawa H, Takahashi M. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and machine learning application for early pregnancy detection using bovine vaginal mucosal membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021; 569: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Andrade D, Kim M, Blanco LP, Karumanchi SA, Koo GC, Redecha P, Kirou K, Alvarez AM, Mulla MJ, Crow MK, Abrahams VM, Kaplan MJ, Salmon JE. Interferon-α and angiogenic dysregulation in pregnant lupus patients who develop preeclampsia. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 977–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cappelletti M, Presicce P, Lawson MJ, Chaturvedi V, Stankiewicz TE, Vanoni S, Harley IT, McAlees JW, Giles DA, Moreno-Fernandez ME, Rueda CM, Senthamaraikannan P, Sun X, Karns R, Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Karp CL, Hildeman DA, Hogan SP, Kallapur SG, Chougnet CA, Way SS, Divanovic S. Type I interferons regulate susceptibility to inflammation-induced preterm birth. JCI Insight 2017; 2: e91288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]