Abstract

Purpose

Retinoblastomas are malignant eye tumors diagnosed in young children. Most retinoblastomas are genetically characterized by biallelic inactivation of the RB1 gene. However, 1.5% of tumors demonstrate high-level amplification of the proto-oncogene MYCN. Patients with MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastoma receive a diagnosis at an earlier age and show a clinically and histologically more malignant phenotype. This study aimed to identify genome-wide molecular features that distinguish this subtype from other retinoblastomas.

Design

Cohort study.

Participants

Forty-seven retinoblastoma tumors, comprising 36 RB1–/–, 4 RB1+/–, and 7 RB1+/+ tumors. In total, 5 retinoblastomas displayed high-level MYCN amplification, with 3 being RB1+/+, 1 being RB1+/–, and 1 being RB1–/–.

Methods

Integrated analysis, based on gene expression, methylation, and methylation-expression correlations, was performed to identify distinct molecular components of MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas compared with other retinoblastoma subtypes. The methylation and methylation-expression correlation analysis was initially conducted within a subset of samples (n = 15) for which methylation profiles were available. The significant findings were cross-validated in the entire cohort (n = 47) and in publicly available data.

Main Outcome Measures

Differentially expressed genes/pathways, differentially methylated genes, and methylation-driven differential gene expression.

Results

A large number of genes (n = 3155) were identified with distinct expression patterns in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. The upregulated and downregulated genes were associated with translation and cell-cycle processes, respectively. Methylation analysis revealed distinct methylated patterns in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumors, many of which showing significant impact on gene expression. Data integration identified a 40-gene expression signature with hypermethylated state resulting in a significant downregulation in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. Cross-validation using the entire cohort and the public domain expression data verified the overall lower expression of these genes not only in retinoblastomas with a MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient background, but also in MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas. These include the metabolism-associated TSTD1 gene and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene CDKN2C.

Conclusions

MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas display significantly distinct molecular features compared with other retinoblastomas, including a set of 40 hypermethylation-driven downregulated genes. This gene set can give insight into the biology of MYCN-amplified retinoblastomas and may help us to understand the more aggressive clinical behavior.

Keywords: Methylation analysis, MYCN, RB1, Retinoblastoma, Transcriptomics

Abbreviations and Acronyms: FC, fold change; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; LOH, loss of heterozygosity; RMA, robust multiarray average

Retinoblastoma is a malignant pediatric eye cancer with a median age at diagnosis of approximately 2 years.1 Incidence rates of retinoblastoma in Europe have been estimated at 1 in 13 844 live births.2 The diagnosis of retinoblastoma is by ophthalmoscopy and ultrasonography, because biopsies are contraindicated owing to the risk of metastasis.3,4 Retinoblastoma is highly curable when diagnosed in an early stage; however, current treatment options are not specifically targeting the molecular features of the tumor and are associated with local and systemic late effects.4,5 Retinoblastoma can develop as a heritable or sporadic tumor. Patients with heritable retinoblastoma (45%) demonstrate biallelic loss of the RB1 gene, and in most patients, bilateral retinoblastoma develops. Nonhereditary retinoblastoma (55%) also develops because of biallelic inactivation of the RB1 gene in approximately 97% of patients; however, a small percentage of patients with sporadic disease (approximately 1.5%) show MYCN amplification as the initiating event,6 whereas the disease of the remaining percentage (approximately 1.5%) remains unexplained. MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient (MYCNA RB1+/+) retinoblastomas are diagnosed at an earlier age compared with classic RB1–/– retinoblastomas and display more aggressive clinical behavior.6

Genetically, MYCN-amplified RB1+/+ retinoblastomas show fewer copy number changes compared with classic RB1–/– retinoblastomas,6 and they are hypothesized to originate in an earlier retinal precursor cell6 compared with RB1–/– retinoblastomas, which are thought to develop from a cone-photoreceptor precursor cell.7,8 In addition, their histologic appearance differs from the classic RB1–/– retinoblastoma, showing an undifferentiated phenotype.6

Previously, we showed that RB1–/– retinoblastomas are heterogeneous and express different levels of genes related to vision (photoreceptorness score), which is positively correlated with the amount of differentiation observed at the histologic level.9 Nondifferentiated tumors show a lower photoreceptorness score and upregulation of ribosome and mRNA synthesis genes. Interestingly, the two MYCN-amplified retinoblastomas that were included in this cohort clustered together with the undifferentiated RB1–/– retinoblastomas.9

A recent study divided retinoblastomas into 2 different groups based on multiomics classification. Similarly to our previous study, the 2 groups showed a correlation between the level of differentiation and expression of vision-related genes, more specifically late cone markers. Again, MYCN-amplified retinoblastomas classified in the undifferentiated group.10 The present study dove deeper into the biology of the MYCN retinoblastoma subtype by correlating information of different molecular levels, defining MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastoma as a unique retinoblastoma subtype with a distinct molecular background.

Methods

Patient Material and Characteristics

Retinoblastoma tumor material was previously collected.9,11 In brief, patient samples were collected after primary enucleation, before start of other treatments at the Amsterdam University Medical Center (UMC) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80° C. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and recommendations of the medical ethical committee of Amsterdam UMC, with a waiver of informed consent (identifiers, IRB00002991, FWA00017598; reference, 2014.360). Expression and copy number data were available for 47 patients, while methylation profiling was performed for a selection of 15 patients (Appendix 1).

RNA Extraction and Expression Profiling

RNA extraction and expression profiling were previously performed9 (GSE59983 [dataset ID of public data at GEO]). In brief, frozen tumor samples were homogenized in TRIzol with a rotor-stator homogenizer and RNA was extracted. DNase treatment was carried out and RNA was purified using the NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up XS kit (Macherey-Nagel). The Affymetrix HT HG U133 + PM96 microarray platform was used for expression profiling, which was performed at ServiceXS/Genomescan (Leiden, The Netherlands).

Microarray Expression Analysis

The raw expression signal intensity CEL files were read into an R object by affy.12 A normalized expression matrix was created by the robust multiarray average (RMA) method embedded in the limma package.13 This was followed by generating a design matrix (i.e., MYCNA RB1PRO; n = 4) versus the rest of the retinoblastoma cohort (n = 43), fitting the linear model and pairwise differential expression analysis by limma. To obtain gene-level differential expression, the probe-level-fold changes and P values were aggregated by the function of mean. Genes with the adjusted P value of < 0.05 were deemed significant. Hierarchical clustering was based on normalized log2 RMA expression values by the WARD2 method. Functional enrichment analysis was performed using the web-based functional annotation suite ToppGene (Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center).

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

DNA extraction and sequencing were previously performed11 (EGAS00001001690 [ID number for published DNA sequence data]). In brief, genomic DNA was isolated using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel) or Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega). The TruSeq Nano DNA library prep kit (Illumina) was used for DNA end repair and ligation of sequencing and indexing adapters. Sequencing was performed using 125-bps paired-end sequencing (HiSeq, 2500; HT, v3/4; Illumina).

DNA Copy Number Analysis

Copy number variation analysis was performed solely for the purpose of re-evaluating MYCN copy number levels and establishing the genomic copy number variable regions that need to be excluded before methylation analysis. The whole-exome sequence reads were used in somatic copy number analysis by CNVkit version 0.9.5.14 The pooled patient-matched diploid blood samples were used as reference in segmentation and calling copy number alternations in tumor samples. Genes with a log2 ratio (sample/control) of > 0.3 were considered as gain. Genes with a log2 ratio (sample/control) of < –0.3 were considered as loss. High-level amplification was defined as log2 ratio (sample/control) of > 2 (approximate absolute copy number, > 10).

Methylation Profiling

Extracted genomic DNA (500 ng) was bisulfite-converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research). Converted samples were processed and hybridized on the Illumina Human Methylation450 BeadChip (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All steps were performed at ServiceXS/Genomescan. BeadChip images were scanned on the iScan system and data were extracted into GenomeStudio software version 2011.1 with Methylation Module version 1.9.0 using default settings. The number of detected genes per sample was between 484 945 and 485 435 of a maximum of 485 557 total genes per array.

DNA Methylation Analysis

The raw methylation signal intensity files (IDAT file type) were read into a methylation intensity object using minifi.15 Data were normalized by quantile methods and probes with low quality (detection P values < 0.01) or high single nucleotide polymorphism frequency (> 0.01), as well as probes residing at X/Y chromosomes; frequently, copy number varied regions were filtered out. This was followed by calculating the methylated probe signal intensities as β and M values. β-Values were used in modeling data, hierarchical cluttering (WARD2), and correlation analysis. M values were used for the differential methylation testing between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent samples using limma. Gene-level methylation-fold changes and significance were obtained by aggregating the corresponding gene’s probe sets log2 fold change (FC) and P values by the function of the mean. Genes with the methylated log2 FC of < 0 and adjusted P value of < 0.05 were defined as hypomethylated. Genes with the methylated log2 FC of > 0 and adjusted P value of < 0.05 were defined as hypermethylated.

DNA Methylation and mRNA Expression Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis between normalized methylation signal intensity (β-value) and normalized expression values (log2 RMA) were performed using the R/MvisAGE package.16 Correlations with R < 0 and a q value of < 0.05 were deemed significant. Because different methylation sites in relationship to CpG islands constitute different methylation amplitude and impact on expression, correlation analysis for shore, island, shelf, and open sea were performed separately. Subsequently, the end product of each analysis was compared and combined for data modeling. Functional annotation network analysis was performed by Cytoscape’s plug-in tool ClueGo.17,18

Analysis of Public Domain Expression Data

The mRNA-expression microarray CEL files from an independent retinoblastoma cohort comprising 61 primary tumor samples were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (GSE58785 [dataset ID of public data at GEO]).10 The expression microarray CEL files from a neuroblastoma cohort comprising 88 tumors were downloaded from GEO (GSE16476 [dataset ID of public data at GEO]).19 The data normalization and the differential expression testing were conducted via the same tools and methodologies as used in the analysis of the in-house expression data.

Data Availability

Expression data were previously published and available at GEO under database number GSE59983.9 Whole exome sequencing data also was previously published and available at EGAS00001001690 (ID number for published DNA sequence data).11 Publicly available data comprising mRNA expression data of 61 retinoblastomas was downloaded from the GEO under database number GSE58785.10 Methylation data are deposited in the GEO repository.

Results

This study relied on a previously described retinoblastoma cohort comprising 47 tumor samples (Appendix 1).9 The RB1 mutation and copy number status and MYCN somatic copy number levels were determined by whole exome sequencing. In total, 36 of 47 retinoblastomas indicated RB1–/– status, 12 of which were caused by loss of heterozygosity of a nonsynonymous or high-impact germline variant. Four retinoblastoma tumors displayed RB1–/+ status and 7 exhibited RB1+/+ genotypes. Somatic copy number analysis identified 5 retinoblastoma tumors with high-level MYCN amplification (absolute copy number, > 10; Supplemental Fig 1A). Of these, 4 are considered RB1 proficient, with 3 exhibiting RB1+/+ and 1 previously characterized as RB1–/+ by clinical diagnostics because of a germline insertion. No additional somatic variants were identified either by clinical diagnostics or whole exome sequencing in this tumor sample. One MYCN-amplified tumor displayed complete RB1 loss (RB1–/–), caused by a germline frameshift on exon 5 followed by loss of heterozygosity. This study aimed to establish whether the high-level MYCN-amplified, RB1-proficient (MYCNA RB1PRO) retinoblastoma present in this cohort displays unique molecular features that discriminate them from the rest of the retinoblastoma genomic subtypes.

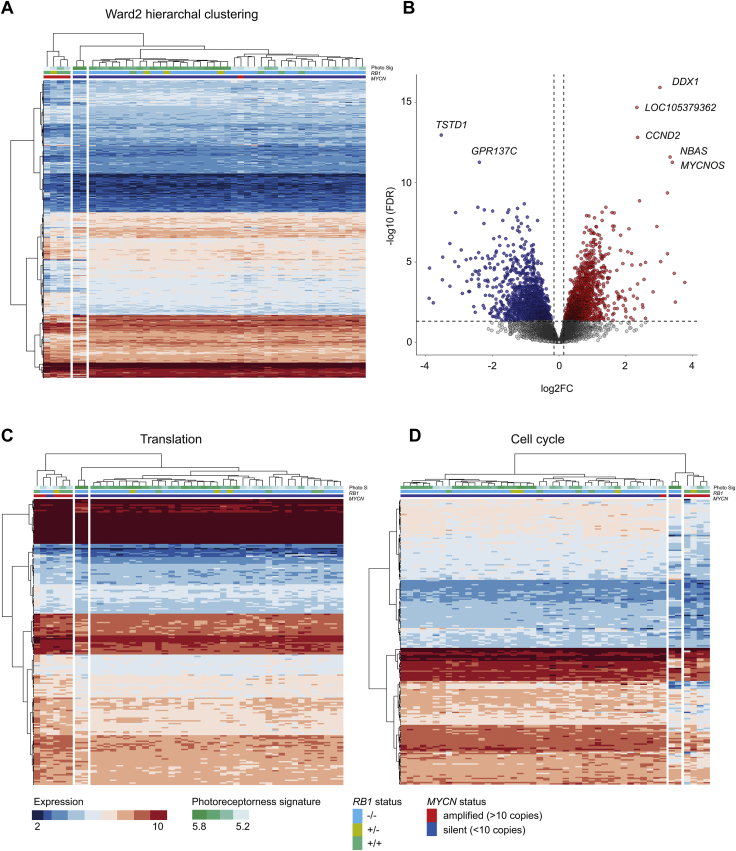

MYCN-Amplified RB1-Proficient Retinoblastomas Possess Significantly Different Gene Expression Patterns Compared with Other Retinoblastoma Subtypes

To observe how different genomic backgrounds concerning MYCN amplification and RB1 mutations may influence retinoblastoma tumors’ transcriptomic relationships, hierarchal WARD2 clustering based on RMA-normalized expression values was performed (Supplemental Fig 1B). Hierarchal clustering resulted in 2 main branches. The MYCNA RB1PRO tumors formed their own separate subbranch within branch 1. The tumor sample with the MYCN-amplified RB1-deficient (MYCNA RB1–/–) background clustered within another subbranch in branch 1 and separated from MYCNA RB1PRO tumors. A previous study from our laboratory showed that branch 1 encompasses 2753 downregulated genes compared with branch 2 samples. These genes were collectively coined as photoreceptorness gene signatures and comprised genes functionally associated with visual perception. Based on the averaged expression of this gene set, each sample was assigned a photoreceptorness score. MYCN-amplified tumors together with other retinoblastoma tumors in branch 1 belonged to the category of samples with a continuously lower photoreceptorness score (Supplemental Fig 1B). To identify gene-expression patterns specifically for MYCNA RB1PRO tumors, differential expression analysis comparing MYCNA RB1PRO (n = 4) to the rest of retinoblastoma tumors (n = 43) was performed (Fig 1, Appendix 2). In total, 3155 differentially expressed genes were detected with 1407 downregulated (log2 FC < 0; adjusted P < 0.05) and 1748 upregulated (log2 FC < 0; adjusted P < 0.05) MYCNA RB1PRO samples. Hierarchical clustering showed a clear distinction between MYCNA RB1PRO tumors and the rest of the samples for the expression of these genes. This was independent of photoreceptorness score (Fig 1A). Moreover, MYCNA RB1PRO samples indicated an overall distinctive expression pattern compared with the MYCNA RB1–/– sample. The top upregulated genes in MYCNA RB1PRO were related to chromosome 2 amplification, most significantly the DDX1, NBAS, and MYCNOS genes. TSTD1, a hydrogen-sulfide metabolism-associated gene, and the MTORC1-related GPR137C gene were the top downregulated genes in MYCNA RB1PRO tumors (Fig 1B). Collectively, the expression analysis revealed that the MYCNA RB1PRO molecular background correlates with significantly distinct transcriptomic signatures that discriminates this retinoblastoma subgroup from other retinoblastoma primary tumors regardless of photoreceptorness signature.

Figure 1.

Differential expression analysis between MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastoma tumors and MYCN-silent and RB1-deficient retinoblastoma tumors. MYCN-amplified, RB1-proficient retinoblastoma tumors display significantly different gene expression patterns compared with the MYCN-silent and RB1-deficient samples. A, Heatmap showing hierarchal clustering (WARD2) findings. The relationship between samples based on the 3155 differentially expressed genes in MYCNARB1PRO retinoblastomas is depicted. Rows represent genes. Columns represent samples. Expression colors are adjusted by the level of expression. The MYCN and RB1 status and samples’ photoreceptorness scores are annotated beneath the dendrogram. The MYCNARB1PRO tumors form their own distinct cluster, departing from other retinoblastoma tumors irrelevant of photoreceptorness background. B, Volcano plot showing the differentially expressed genes in MYCNARB1PRO retinoblastomas. Top MYCN-amplified upregulated genes are associated with chromosome 2 amplification. The most significantly downregulated gene in MYCNARB1PRO samples, TSTD1, functions in hydrogen-sulfide metabolism. C, Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering (WARD2) visualizing the expression of 229 ribosomal RNA processing and translation initiation-associated genes significantly upregulated in MYCNARB1PRO samples. The high-level MYCN-amplified tumors cluster together independent of RB1 genotypic background or photoreceptorness levels. D, Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering (WARD2) for the expression of 220 cell cycle-related genes significantly downregulated in MYCNARB1PRO samples. MYCN-amplified samples with RB1-proficient background cluster together. Two RB1-null MYCN-silent samples indicate a closer relationship to MYCNARB1PRO samples and cluster in the adjacent subbranch. Expression values as normalized log2 robust multiarray average: upregulation, log2 fold change (FC) > 0 and adjusted P < 0.05; downregulation, log2 FC < 0 and adjusted P < 0.05. FDR = false dscovery rate.

Gene Ontology Analysis Reveals an Upregulation of Genes Involved in Translation and Downregulation of Cell Cycle-Related Genes in MYCNARB1PRO Tumors

To annotate the differentially expressed genes in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastoma functionally, gene ontology analysis was performed using ToppGene. Functional enrichment analysis for MYCNA RB1PRO-upregulated genes resulted in multiple overlapping biological processes involved with translation, such as ribosomal RNA processing and translational initiation and elongation (Appendix 3). This group of translation-associated genes collectively consisted of 229 genes (Appendix 4). Hierarchical clustering based on the expression of the translation-related genes resulted in separate branch for MYCN-amplified tumors, including the MYCNA RB1–/– tumor (Fig 1C). Functional annotation based on downregulated genes in MYCNA RB1PRO identified several overlapping biological processes associated with the cell cycle (Appendix 3). This cell cycle-associated category comprised 220 genes (Appendix 4). Hierarchical clustering showed a separation of the MYCNA RB1PRO genes from the rest of cohort with the exception of 2 MYCN-silent RB1–/– samples that cluster in a subbranch adjacent to the MYCNA RB1PRO branch (Fig 1D). Furthermore, the cell cycle gene group comprises a diverse array of functional categories such as DNA repair and replication, negative regulation of cell cycle phase transition (includes 6 cyclin kinase inhibitors), regulation of G2/M mitotic cell cycle transition, and sister chromatid segregation. Overall, functional enrichment analysis showed that the differential transcriptomic signatures of MYCNA RB1PRO are highly functionally relevant because they are associated with major and general biological processes.

Low Expression of Both Cone and Rod Photoreceptor Markers in MYCN-Amplified RB1-Proficient Retinoblastomas

Looking further into the importance of retinal markers in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas, we performed clustering analysis on the entire cohort specifically for genes expressed in cone and rod photoreceptors, Müller glia, horizontal, bipolar, amacrine astrocytes, microglia, and ganglion cells (Supplemental Fig 2). This resulted in a scattered clustering of MYCNA RB1PRO samples within different subbranches. As the clustering showed, an overall tendency exists for the MYCNA RB1PRO samples to reside relatively closer to retinoblastoma tumors with lower photoreceptorness scores, which infers relatively lower expression of retina markers associated with visual perception (Supplemental Fig 2). Overall, the analysis did not identify a unique expression pattern for a specific set of retina markers that widely separate MYCNA RB1PRO from other retinoblastomas.

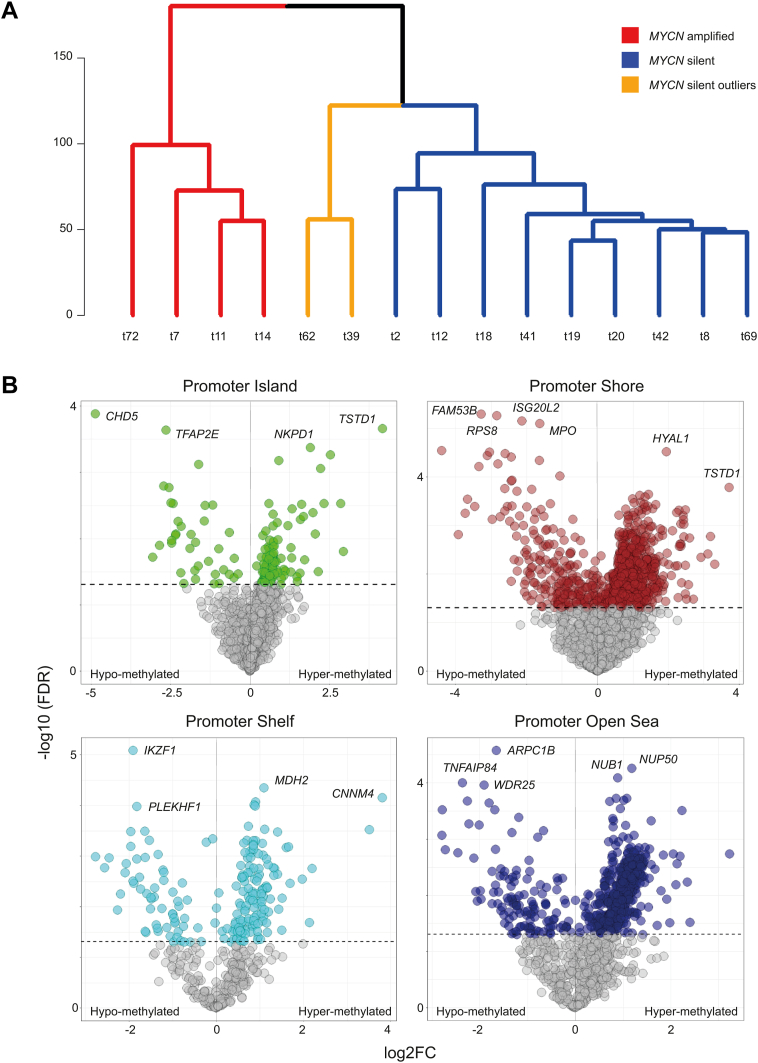

At the Methylation Level, MYCN-Amplified RB1-Proficient Retinoblastomas Are Distinct from MYCN-Silent Retinoblastomas

Of the 47 samples in the retinoblastoma cohort, methylation profiles for 15 samples, including the 4 MYCNA RB1PRO samples, were available. These profiles were examined to explore the significant epigenetic differences between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent tumors. In addition, the methylation and expression profile of the 15 samples were integrated to identify the most significant methylation-driven gene expression in MYCN tumors. We subsequently cross-examined the reproducibility of these findings (n = 15) in the entire retinoblastoma cohort (n = 47) and publicly available data. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent tumors based on normalized methylated signals (β value) resulted in complete separation of MYCN-amplified samples from MYCN-silent samples (Fig 2A). Differential methylation analysis was performed to assess the amplitude of methylation differences between the two retinoblastoma groups (Appendix 5). Because promoter site methylations have more effect on gene expression, the downstream analysis mainly focused on differentially methylated genes in this region. Moreover, because different methyl sites in relationship to the CpG island may impact gene expression differently, the differentially methylated genes between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent samples for promoter island, shore, shelf, and open sea were modeled and evaluated separately (Fig 2B). For all the different methylation sites, many genes showed significant differential methylation between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent samples, but promoter shore and promoter open sea were the most densely differentially methylated regions between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent tumors. Altogether, methylation analysis, in line with transcriptomic profiling, showed unique methylation patterns in MYCNA RB1PRO tumors that distinguishes them from other retinoblastomas.

Figure 2.

Differential methylation analysis between a group of 4 high-level MYCN-amplified and a group of 11 MYCN-silent retinoblastomas. MYCN tumors possess distinct methylation patterns compared with non–MYCN-amplified retinoblastomas. A, Dendrogram showing the hierarchical clustering relationships of the retinoblastoma samples. Based on the WARD2 clustering method, MYCN-amplified tumors display distinct methylation patterns compared with MYCN-silent retinoblastomas. B, Volcano plots depicting the differentially methylated genes at various promoter methylation sites between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent samples. All sites indicate significantly differentially methylated genes between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent samples. Methylated signal is quantile-normalized β values: hypermethylated, log2 fold change (FC) > 0 and adjusted P < 0.05; hypomethylated, log2 FC < 0 and adjusted P < 0.05). FDR = false discovery rate.

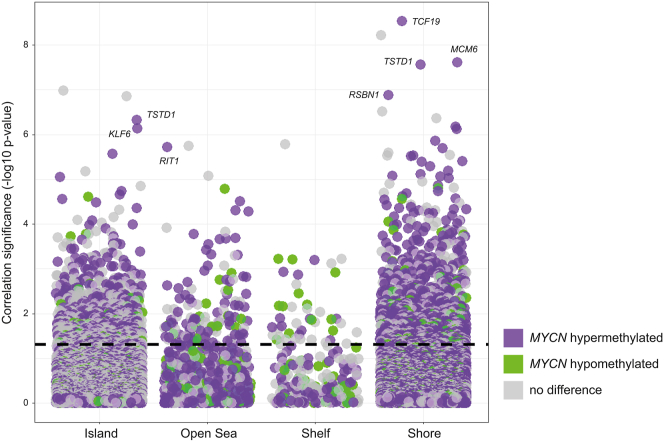

Promotor Hypermethylation Is the Main Driver of Methylation-Specific RNA Expression Changes in MYCN-Amplified Retinoblastomas

To identify genes whose expression levels were significantly determined by methylation, Pearson correlation analysis between gene-level methylated signals (β values) and normalized gene expression levels was performed (Fig 3, Appendix 6). Correlations with R < 0 and q < 0.05 were deemed significant. Promoter methylation in shores followed by islands correlated most significantly with RNA expression levels. However, methylation levels at shelfs and open sea sites showed less effect on gene expression. Based on the correlation analysis, the hypermethylation in MYCN-amplified samples versus MYCN-silent samples was the most predominant source of mRNA expression changes, with many genes hypermethylated in MYCN-amplified tumors showing significant methylation-expression correlations. The MYCN-hypermethylated genes TCF19, MCM6, TSTD1, RSBN1, KLF6, and RIT1 were the most significant methylation-driven genes. Overall, it was shown that the hypermethylation observed in high MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas has significant influence on global gene expression in this tumor subtype.

Figure 3.

Promoter methylation-expression correlation analysis. Methylation status significantly influences gene expression in MYCN-amplified samples. Correlation jitter plot presenting the significance of methylation-expression correlations across the retinoblastoma panel, based on normalized methylated signal β values and the expression log2 robust multiarray averages. Correlations with R < 0 and q < 0.05 were considered significant. The y-axis presents correlation significance as the minus log10-transformed q value. The x-axis presents the methylation region. In MYCN-amplified tumors, hypermethylation has more overall significant influence on gene expression than hypomethylation. TCF19 and TSTD1 are the most significant methylation expression-correlated genes in MYCN-amplified tumors.

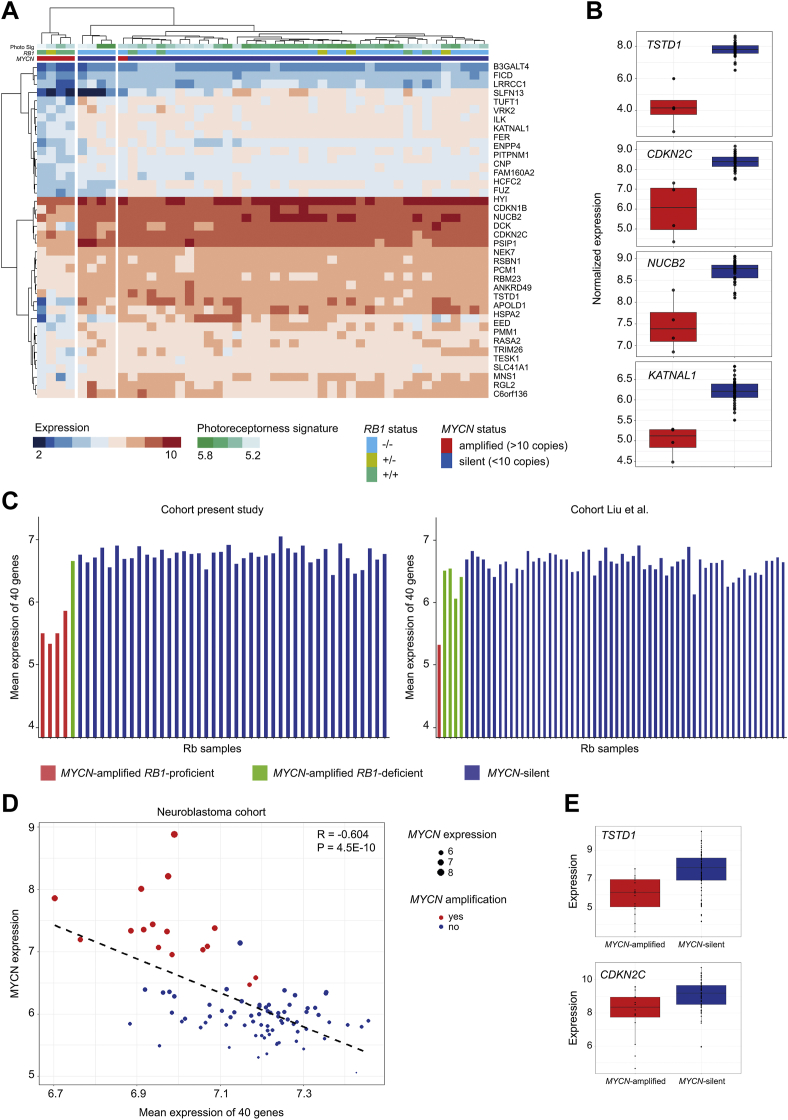

MYCN-Amplified RB1-Proficient Retinoblastomas Express a Unique Set of Hypermethylation-Driven Genes That Distinguishes Them from Other Retinoblastomas

To identify hypermethylated and hypomethylated genes that correlated with significant differential expression between MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas and the rest of the cohort, the differential expression, methylation, and correlation results were integrated (Supplemental Fig 3). This facilitated the identification of genes in which hypermethylation in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastoma (log2 FC > 0; adjusted P < 0.05) strongly correlated with expression (R < 0; q < 0.05) and subsequently resulted in significant downregulation in MYCNA RB1PRO samples (log2 FC < 0; adjusted P < 0.05). The data integration was also performed in the opposite direction to determine hypomethylation-driven upregulated genes in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas compared with the rest of the cohort.

The integrated analysis identified 79 overlapping genes that showed hypermethylation on promoter shore or island regions and that were significantly downregulated in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas compared with MYCN-silent retinoblastomas (Supplemental Fig 4). Considerably fewer shelf and open sea hypermethylated genes showed significant downregulation in MYCN-amplified retinoblastomas. Nine genes were identified that showed hypomethylation and were significantly upregulated in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas. Our data show that hypermethylation in MYCN-amplified samples is the most important epigenetic event inducing gene expression differences between MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastoma and the other retinoblastomas.

To determine whether these results were also reproducible in a broader context, the findings were cross-validated using RNA expression data available from the entire retinoblastoma cohort (n = 47). Hierarchical clustering for the expression values of the 79 hypermethylated genes, but not for the hypomethylated genes, resulted in clear distinction in expression between MYCNA RB1PRO and the rest of the retinoblastomas (Supplemental Fig 5). The unique expression pattern was also reflected in expression-fold changes between MYCNA RB1PRO and the rest of the retinoblastomas (Appendix 7). All 79 genes showed a downregulation in MYCNA RB1PRO, with 74 being statistically significant. Although expression of all these genes was significantly decreased in MYCNA RB1PRO tumors, their expression was not clear-cut and may be partially influenced by the relatively low photoreceptorness score observed in this MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastoma subgroup. Thus, to extract the most significant expression signatures exclusive to MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas, we performed 3 additional differential expression analysis. Analyses 1 and 2 were between MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas and the 2 main retinoblastoma subbranches (adjusted P < 0.05, MYCN vs. clusters 1 and 2), whereas analysis 3 was between branches 1 and 2 to filter out genes that were differentially expressed between the two (adjusted P > 0.1, cluster 2 vs. cluster 1; Supplemental Figs 3 and 5, Appendix 8). Subsequently, a refined list of 40 genes was produced showing downregulation most exclusively in MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas (Appendix 9). This was confirmed by hierarchal clustering, which showed a clear separation between MYCNA RB1PRO and the rest of the retinoblastoma cohort (Fig 4A). TSTD1, CDKN2C, NUCB2, and KATNAL1 showed the most significant MYCNA RB1PRO-specific downregulated expression pattern among the hypermethylated genes in this retinoblastoma subtype (Fig 4B). In addition, averaged expression of the 40 genes displayed a clear distinction between different retinoblastoma groups. MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastomas showed a clear downregulation of these 40 genes, while the MYCNA RB1DEF retinoblastoma sample in this cohort showed a similar expression signature as the MYCN-silent retinoblastomas (Fig 4C, left). Our findings were also validated in an independent previously published retinoblastoma cohort by Liu et al10 (Fig 4C, right; Supplemental Fig 6), where the MYCNA RB1PRO retinoblastoma showed an average lower expression of this gene panel in comparison with the rest of the retinoblastoma cohort. Overall, the integrated analysis revealed that the hypermethylation pattern in MYCNA RB1PRO tumors enforces significant downregulation of a gene set in these tumors that discriminates the MYCNA RB1PRO tumor from all other retinoblastoma subtypes.

Figure 4.

Methylation-driven differentially expressed genes in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. MYCN-driven, RB1-proficient tumors display unique methylation-derived gene expression signatures that globally discriminate them from other retinoblastoma tumors. A, Heatmap showing hierarchal clustering for 40 genes that are hypermethylated (log2 fold change [FC] > 0; adjusted P < 0.05), downregulated (log2 FC < 0; adjusted P < 0.05), and indicate significant methylation-expression correlation (R < 0; q < 0.05) in MYCNARB1PRO retinoblastomas. The distinct expression of the 40 genes in MYCNARB1PRO samples primarily identified within a subset of the cohort (n = 15) is also reproducible in the entirety of the local retinoblastoma cohort (n = 47). For the expression of these genes, MYCNARB1PRO retinoblastomas (n = 4) show clear-cut separation from the rest of the retinoblastoma cohort (n = 47). B, Box-dot plots demonstrating normalized expression values of the top 4 hypermethylation-driven downregulated genes in MYCNARB1PRO versus the rest of the retinoblastoma cohort. C, Bar charts showing averaged expression of the 40 hypermethylated-driven genes discriminating MYCNARB1PRO retinoblastomas from other retinoblastoma subtypes: the current study (left) and public domain expression data (Liu et al10) including 62 retinoblastoma tumors (right). Red indicates MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. Green indicates MYCN-amplified RB1-deficient retinoblastomas. Blue indicates MYCN-silent retinoblastomas. Expression values are as normalized log2 robust multiarray average. D, Scatterplot depicting the association between MYCN expression and the mean expression of the 40 MYCNARB1PRO hypermethylation-driven downregulated genes in neuroblastoma (Pearson method). MYCN-amplified samples appear in red and MYCN-silent samples appear in blue. The dot sizes are adjusted by the expression level of MYCN. MYCN expression shows a significant negative correlation with the expression of the 40 signature genes (R = –0.604; P = 4.5 × 10–10). E, Box-dot plots for the normalized expression values of TSTD1 and CDKN2A within MYCN-amplified and silent neuroblastomas. Rb = retinoblastoma.

The Hypermethylation-Driven, Downregulated Genes in MYCNARB1PRO Tumors Also Show Overall Lower Expression in MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma

Furthermore, because MYCN amplification is also a common somatic event in neuroblastoma, we examined the behavior of the signature genes in a public data set derived from 88 neuroblastoma tumors, with 16 harboring a MYCN amplification (Fig 4D, E). Differential expression analysis verified a significantly higher expression of MYCN in the MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas. Subsequently, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis between the expression of MYCN and the mean expression of the signature genes. The analysis showed a significant negative correlation between mean expression of the MYCNA RB1PRO signature genes and the expression of MYCN (R = –0.604; P = 4.5 × 10–10; Fig 4D). We also examined the expression of the 40 genes between MYCN-amplified and MYCN-silent neuroblastoma to identify the genes contributing most significantly to the observed correlation. A total of 33 of the 40 genes showed a negative-fold change in expression in MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas compared with MYCN-silent samples, with 11 being significant by the adjusted P value of < 0.05 (Appendix 10). These included the top MYCNA RB1PRO downregulated TSTD1 and CDKN2C genes, which also showed a significantly lowered expression in MYCN-amplified compared with the MYCN-silent neuroblastomas (Fig 4E). Overall, the expression patterns observed in neuroblastoma MYCN-amplified samples were in line with the expression of these genes in MYCNA RB1PRO, suggesting a broader implication for the observed signatures in MYCN-amplified cancers beyond retinoblastoma.

The Hypermethylation-Driven, Downregulated Genes in MYCNARB1PRO Tumors Are Interactionally Enriched and Linked to a Number of Pathways Including G1 to S-Phase Transition

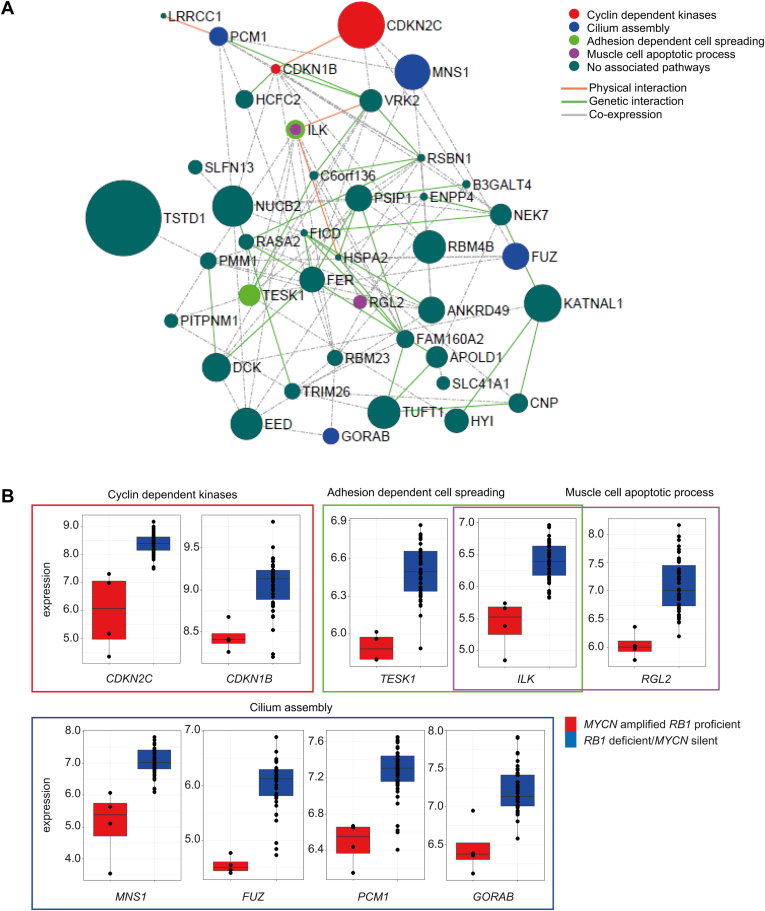

Gene–gene interaction and functional network analysis was performed using GeneMANIA and ClueGo, respectively, for the 40 MYCNA RB1PRO hypermethylation-driven downregulated genes. Network analysis detected several genetic and physical interactions between these genes (Fig 5A). Pathway analysis showed that some of these genes were enriched for functionally relevant processes. These were cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor activity (CDKN2C and CDKN1B), muscle cell apoptotic process (ILK and RGL2), adhesion-dependent cell spreading (ILK and TESK1), and nonmotile cilium assembly (GORAB, PCM1, FUZ, and MNS1; Fig 5B). In summary, network and pathway analysis identified a set of interacting and functionally related genes that, based on their methylation-driven expression pattern, significantly discriminate MYCNA RB1PRO tumors from the rest of retinoblastomas.

Figure 5.

Functional and gene–gene interaction analysis for methylation-driven differentially expressed genes in MYCN-amplified tumors. A, Interaction network with functional annotation depicting the interaction between genes as well as their pathway enrichment. Interaction network analysis was conducted by GeneMANIA and pathway analysis was conducted by ClueGo. Nodes represent genes. Edges represent interaction. Node sizes are adjusted based on the significance of the specific downregulation in MYCNARB1PRO tumors: largest node, –log10 adjusted P = 11.5; smallest node, –log10 adjusted P = 2.5). Node colors are adjusted based on the functional group they belong to. Edge’s types are drawn based on the type of interaction. B, Box plots showing for the expression of the downregulated pathways in MYCNARB1PRO tumors. Expression values as normalized log2 robust multiarray average.

Discussion

In this study, we explored unique transcriptomic and epigenomic features of MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas compared with other retinoblastomas. The genome-wide mRNA expression and methylation analysis identified large numbers of differentially expressed and methylated genes. Using an integrated approach, we identified a set of hypermethylation-driven downregulated genes in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumors. The MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient specific downregulated genes were also validated analyzing an independent cohort, inferring the universality of the findings. Moreover, we observed a downregulated pattern for the expression of at least a subset of these genes in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma compared with MYCN-silent neuroblastoma. Overall, the results showed that MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas do possess distinct molecular signatures that diverge them from MYCN-silent or RB1-null retinoblastoma, or both. This in turn may point to differential biological or oncogenic dynamics within this rare retinoblastoma subtype, which is already clinically reflected in the earlier age at diagnosis compared with that of classical RB1–/– retinoblastomas.6 Based on the neuroblastoma data, this distinct property may also have implications beyond retinoblastoma and may be linked to the general biological features of pediatric cancers harboring MYCN amplification.

A previous transcriptomic-based analysis revealed 2 major subgroups within retinoblastoma, interacting in a continuous fashion.9 A recent multiomics classifications study also further postulated the existence of 2 major retinoblastoma groups.10 The present analysis reconfirmed the clustering of MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient wild-type tumors within a retinoblastoma subbranch characterized by lower photoreceptorness. However, it also extracted a large set of differentially expressed genes in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient samples. This set clearly distinguished the subgroup from other retinoblastomas, independently of their photoreceptorness grade. It is suggested that these gene signatures infer unique molecular characteristics that are possessed by these rare tumors. We showed that genes upregulated in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas were significantly enriched for translation and mRNA synthesis processes, whereas downregulated genes were enriched for cell cycle regulation pathways. The upregulation of translation and mRNA synthesis in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas may be the direct outcome of MYCN overexpression. It is well known that the MYCN oncogene significantly impacts on translation via boosting ribosomal biogenesis and mRNA translation.20,21 MYCN overexpression also influences the cell cycle.22,23 The fact that we find downregulation of genes that are important for proliferation in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastoma may initially seem counterintuitive. However, it is noted that not all cell cycle-related genes on the list influence cell cycle dynamics in a similar fashion, and the downregulation of different cell cycle genes or subclasses may impose different and at times opposing effects on cell cycle progression. In fact, the downregulation of cell cycle G1 to S-phase transition genes such as cyclin kinase inhibitors may promote further proliferation, rather than inhibition, in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastoma. Our analysis indicated, in concordance with the literature, a systematic downregulation of 6 cytokine kinase inhibitors.22 This can potentially induce the acceleration of cell cycle transition through G1.24 These results are in line with and complement the upregulation of CCND2 observed in the MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. CCND2 is an important regulator of cell cycle and it facilitates G1 to S-phase transition. The hyperactivity of CCND2 has been associated with malignancy, and it promotes proliferation in cancer cell lines.25 In line with this, one of the most striking and statistically significant findings in the study was the hypermethylation-driven downregulation of CDKN2C. This may imply a selective pressure for the repression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors activity within the MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient genomic background. CDKN2C in particular retained the most consistent and significantly declined mRNA expression in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumors. CDKN2C blocks cell cycle progression via its interaction with CDK4 and CDK6. Consequently, it has been shown that the declined CDKN2C activity can lead to dysregulated S-phase cell cycle progression, which functionally resembles a RB1 null-like cell cycle behavior.26,27 CDKN2C repression has been reported in multiple cancers, including melanoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and pituitary adenomas.28, 29, 30 Furthermore, a recent genomic study in leiomyosarcoma characterized by frequent RB1/TP53 mutations identified a distinct class featuring wild-type TP53/RB1 and homozygous deletion of CDKN2C.31 Consequently, it is hypothesized that the hypermethylation of CDKN2C in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas may be a distinct oncogenic event and it may potentially act as an alternative to RB1 deactivation in dysregulating G1 and S-phase cell cycle progress. The analysis of MYCN-amplified versus MYCN-silent neuroblastoma also showed a significant downregulation of CDKN2C in MYCN-amplified samples, suggesting a potential, general oncogenic function for the lowered expression of CDKN2C for MYCN-amplified pediatric cancers.

In fact, the differences in molecular spectra of MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas compared with other retinoblastoma subtypes were very well marked at the epigenomic level, which affected a molecular network beyond CDKN2C. Epigenetic alterations are well-known cancer events with versatile impact on various stages of carcinogenesis, ranging from disruption of genomic stability to silencing of tumor suppressors and regulatory elements.32,33 In addition, methylation patterns can potentially be used as biomarkers in tissue characterization, prognosis prediction, and adapting cancer treatment strategies.34 Differential methylation profiling identified a large number of significantly hypomethylated and hypermethylated genes in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient wild-type tumors compared with MYCN-silent retinoblastomas. The integrated methylation expression analysis pointed to hypermethylation rather than hypomethylation as the main epigenetic influencer of gene expression differences between the 2 retinoblastoma subtypes. This was projected most notably in the case of 40 hypermethylated downregulated genes in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient samples. The expression pattern of these genes clearly separates MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumors from other retinoblastomas, observed in both in-house and public-domain patient cohorts. The MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient hypermethylation-driven, differentially expressed genes are a functionally diverse set of genes, suggesting that hypermethylation in this tumor subtype is indeed not functionally unidirectional, and it may be modulating multiple aspects of the tumor biology. Next to cell cycle transition-related CDKN2C, the other top distinctly downregulated gene, thiosulfate sulfurtransferase-like domain containing 1 (TSTD1), is of a radically different functional class. This gene, in fact, is poorly characterized; however, it is established to be involved in hydrogen sulfide metabolism by the means of S-sulfanylglutathione production.35, 36, 37 Hence, the very distinct and specifically lowered expression level of this gene potentially hints at the existence of differential metabolic dynamics within MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas. In addition, cilia assembly was also identified as a potential differential regulated pathway in MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient retinoblastomas compared with the rest of the cohort. Cilia are sensory organelles that protrude from the cell surface into the extracellular space and are expressed on all nonhematologic cell types in the body. They are important for communication between cells and the tumor microenvironment and are associated with several important signaling pathways. The formation of cilia is linked to control of the cell cycle, where they occur in the G0 to early G1 phases and vanishes again in S or G2 phase. Because oncogenic signaling, for example by MYCN, stimulates proliferation, this can result in the loss or shortening of primary cilia.38

In conclusion, although MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumors reside within the molecular spectra of retinoblastoma, they still possess significant differences in expression and methylation patterns that distinguish them from the other retinoblastoma tumors. This may emphasize the importance of also implementing more targeted and gene set-oriented approaches when classifying and labeling tumor subtypes. Tumors, which may be interrelated globally, still may possess a subset of features that significantly diverge them from each other. This indeed is the trend we see in the case of MYCN tumors. The significantly distinct molecular components in MYCN tumors, such as upregulated translation processes or hypermethylated genes related to metabolism, cell cycle transition, or cilium assembly, may imply the presence of differential cellular and oncogenic dynamics unique to the MYCN-amplified RB1-proficient tumor subtype. The recently developed noninvasive methods for the detection of gene amplification in tumors, analyzing circulating free DNA present in aqueous humor of affected eyes,39 may be relevant in this context. It can be especially expected that the large MYCN amplifications, as present in the MYCN-amplified tumor, may be detected relatively more easily. Detection of MYCN amplification may aid the decision-making process regarding whether to enucleate an eye. Furthermore, it can be envisioned that the unique MYCN signature we discovered in these tumors may be explored in the future to adapt a more personalized and targeted approach when treating children with MYCN-amplified retinoblastoma.

Manuscript no. XOPS-D-22-00070.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available atwww.ophthalmologyscience.org.

Disclosure(s):

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Supported by Dutch Cancer society (KWF) project 10832 and Stichting Cancer Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

HUMAN SUBJECTS: No human subjects were included in this study. The Amsterdam UMC institutional review board approved the study. All research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Roohollahi, de Jong, Dorsman

Analysis and interpretation: Roohollahi, de Jong, Fabius, Moll, Dorsman

Data collection: Roohollahi, de Jong, van Mil

Obtained funding: Dutch Cancer Society (KWF) project 10832 and Stichting Cancer Centre Amsterdam.

Overall responsibility: Roohollahi, de Jong, van Mil, Fabius, Moll, Dorsman

Contributor Information

Yvonne de Jong, Email: y.dejong1@amsterdamumc.nl.

Josephine C. Dorsman, Email: jc.dorsman@amsterdamumc.nl.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Global Retinoblastoma Study Group. Fabian I.D., Abdallah E., et al. Global retinoblastoma presentation and analysis by national income level. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):685–695. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stacey A.W., Bowman R., Foster A., et al. Incidence of retinoblastoma has increased: results from 40 European countries. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(9):1369–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimaras H., Corson T.W., Cobrinik D., et al. Retinoblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1 doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munier F.L., Beck-Popovic M., Chantada G.L., et al. Conservative management of retinoblastoma: challenging orthodoxy without compromising the state of metastatic grace. “Alive, with good vision and no comorbidity.”. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019;73 doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabian I.D., Onadim Z., Karaa E., et al. The management of retinoblastoma. Oncogene. 2018;37(12):1551–1560. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rushlow D.E., Mol B.M., Kennett J.Y., et al. Characterisation of retinoblastomas without RB1 mutations: genomic, gene expression, and clinical studies. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):327–334. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh H.P., Wang S., Stachelek K., et al. Developmental stage-specific proliferation and retinoblastoma genesis in RB-deficient human but not mouse cone precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(40):E9391–E9400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808903115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X.L., Fang Y., Lee T.C., et al. Retinoblastoma has properties of a cone precursor tumor and depends upon cone-specific MDM2 signaling. Cell. 2009;137(6):1018–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kooi I.E., Mol B.M., Moll A.C., et al. Loss of photoreceptorness and gain of genomic alterations in retinoblastoma reveal tumor progression. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(7):660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J., Ottaviani D., Sefta M., et al. A high-risk retinoblastoma subtype with stemness features, dedifferentiated cone states and neuronal/ganglion cell gene expression. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5578. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25792-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kooi I.E., Mol B.M., Massink M.P., et al. Somatic genomic alterations in retinoblastoma beyond RB1 are rare and limited to copy number changes. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep25264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautier L., Cope L., Bolstad B.M., Irizarry R.A. affy—Analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(3):307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie M.E., Phipson B., Wu D., et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talevich E., Shain A.H., Botton T., Bastian B.C. CNVkit: genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aryee M.J., Jaffe A.E., Corrada-Bravo H., et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter V., Du Y., Danilova L., et al. MVisAGe identifies concordant and discordant genomic alterations of driver genes in squamous tumors. Cancer Res. 2018;78(12):3375–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindea G., Galon J., Mlecnik B. CluePedia Cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(5):661–663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bindea G., Mlecnik B., Hackl H., et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valentijn L.J., Koster J., Haneveld F., et al. Functional MYCN signature predicts outcome of neuroblastoma irrespective of MYCN amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(47):19190–19195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208215109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boon K., Caron H.N., van Asperen R., et al. N-myc enhances the expression of a large set of genes functioning in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. EMBO J. 2001;20(6):1383–1393. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole M.D., Cowling V.H. Transcription-independent functions of MYC: regulation of translation and DNA replication. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(10):810–815. doi: 10.1038/nrm2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baluapuri A., Wolf E., Eilers M. Target gene-independent functions of MYC oncoproteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(5):255–267. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0215-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dang C.V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Sante G., Page J., Jiao X., et al. Recent advances with cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: therapeutic agents for breast cancer and their role in immuno-oncology. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19(7):569–587. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1615889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hung C.S., Wang S.C., Yen Y.T., et al. Hypermethylation of CCND2 in lung and breast cancer is a potential biomarker and drug target. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3096. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chinnam M., Goodrich D.W. RB1, development, and cancer. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2011;94:129–169. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380916-2.00005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaidelli A., Negri G.L., Jan A., et al. MYCN amplified neuroblastoma requires the mRNA translation regulator eEF2 kinase to adapt to nutrient deprivation. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24(9):1564–1576. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirsch M., Morz M., Pinzer T., et al. Frequent loss of the CDKN2C (p18INK4c) gene product in pituitary adenomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48(2):143–154. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z., Liao B., Xiang X., Ke S. miR-21–5p promotes cell proliferation and G1/S transition in melanoma by targeting CDKN2C. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10(5):752–760. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou M., Mao Y., Yu S., et al. LINC00673 represses CDKN2C and promotes the proliferation of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by EZH2-mediated H3K27 trimethylation. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1546. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams E.A., Sharaf R., Decker B., et al. CDKN2C-null leiomyosarcoma: a novel, genomically distinct class of TP53/RB1-wild-type tumor with frequent CIC genomic alterations and 1p/19q-codeletion. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4 doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00040. PO.20.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feinberg A.P., Ohlsson R., Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(1):21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prada D., Gonzalez R., Sanchez L., et al. Satellite 2 demethylation induced by 5-azacytidine is associated with missegregation of chromosomes 1 and 16 in human somatic cells. Mutat Res. 2012;729(1–2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Locke W.J., Guanzon D., Ma C., et al. DNA methylation cancer biomarkers: translation to the clinic. Front Genet. 2019;10:1150. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Libiad M., Motl N., Akey D.L., et al. Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase-like domain-containing 1 protein interacts with thioredoxin. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(8):2675–2686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melideo S.L., Jackson M.R., Jorns M.S. Biosynthesis of a central intermediate in hydrogen sulfide metabolism by a novel human sulfurtransferase and its yeast ortholog. Biochemistry. 2014;53(28):4739–4753. doi: 10.1021/bi500650h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenzel K., Felix S.B., Flachmeier C., et al. Identification and characterization of KAT, a novel gene preferentially expressed in several human cancer cell lines. Biol Chem. 2003;384(5):763–775. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H., Kiseleva A.A., Golemis E.A. Ciliary signalling in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(8):511–524. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry J.L., Xu L., Kooi I., et al. Genomic cfDNA analysis of aqueous humor in retinoblastoma predicts eye salvage: the surrogate tumor biopsy for retinoblastoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16(11):1701–1712. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Expression data were previously published and available at GEO under database number GSE59983.9 Whole exome sequencing data also was previously published and available at EGAS00001001690 (ID number for published DNA sequence data).11 Publicly available data comprising mRNA expression data of 61 retinoblastomas was downloaded from the GEO under database number GSE58785.10 Methylation data are deposited in the GEO repository.