Abstract

Introduction:

In the past decade, investigations of the relationship between sleep duration and eating behaviours have been emerging; however, a formal synthesis of the literature focussed on adolescent populations has not yet been conducted. We conducted a scoping review of the literature examining the relationship between sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescents. Gaps in the research and directions for future research were identified based on the findings.

Methods:

A systematic search was employed on four research databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Scopus; relevant grey literature was also reviewed. Studies that reported on the relationship between sleep duration and eating behaviours among high school–aged adolescents were included in the review. Data were extracted, charted and synthesized into a narrative. Consistent with the purpose of a scoping review, the methodological quality of the studies was not appraised. Stakeholders were consulted to validate the findings and provide insight into the interpretation and identification of pressing gaps in the research that remain to be addressed.

Results:

In total, 61 studies published between 2006 and 2021 met the criteria for review. Existing research focussed heavily on examining sleep duration in relation to intake of food from certain food groups, beverages and processed foods, and relied on a population study design, cross-sectional analyses and self-report measures.

Conclusion:

Future research is needed to understand the link between sleep duration and eating-related cognition, eating contexts and disordered eating behaviours in order to better understand how ensuring sufficient sleep among adolescents can be leveraged to support healthier eating practices and reduce diet-related risks.

Keywords: sleep, dietary patterns, eating habits, youth, adolescents

Highlights

Unique to this study, we reviewed the breadth of the literature related to sleep duration, dietary intake and eating habits among adolescents.

We found a large emphasis on the dietary intake of healthful foods, beverages and processed foods, and limited focus on the contextual factors that shape eating, eating- related cognitions and disordered eating symptoms.

Stakeholders validated the findings, provided insight into the interpretation of the findings and highlighted areas for future research.

Additional sleep research exploring the cognitive and contextual factors surrounding eating is needed (e.g. eating with others, eating when not hungry, binge eating).

Introduction

Evidence suggests that poor dietary patterns characterized by excessive intake of sugar, saturated fat and salt, as well as low intake of vegetables and whole grains, are associated with the development of noncommunicable diseases (e.g. diabetes).1,2 The role of psychosocial eating habits, such as eating with other people and mindful eating, is also being increasingly recognized for its role in supporting healthy eating.3,4 Hence, supporting healthy food consumption and eating habits is critical to prevent and manage diet-related diseases. Given the role of sleep in regulating hormones that affect appetite (e.g. insulin, leptin, ghrelin),5-8 fostering adequate sleep among adolescents could support the development of a range of healthy behaviours during adolescence.9-11

Considering the importance of the adolescent period in the development of life-long behaviours, promoting healthy eating behaviours among adolescents is critical.12 Adolescence is especially important because it is characterized by many developmental and behavioural changes, including a decline in healthy eating habits.13 Additionally, changes to the circadian rhythm that occur during this developmental period result in a natural shift towards later sleep onset among adolescents.14 This shift in the circadian rhythm can contribute to insufficient sleep, which is further compromised by changes such as early school start times, increased academic demands and extracurricular activities.15-17 Therefore, examining the relationship between these two modifiable lifestyle factors (sleep duration and eating behaviours) among adolescents is necessary to better understand approaches to facilitating health and the development of healthy life-long behaviours.

Sleep is an essential component of healthy development during adolescence. For optimal health and well-being, it is recommended that adolescents aged 15 to 17years get 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night.18 In the past decade, adequate sleep as a lifestyle factor has garnered increasing attention in the literature. Short sleep duration over a prolonged period of time is associated with a range of adverse physical and emotional health outcomes (e.g. mood dysregulation, accidental injuries).15,19 Insufficient sleep, in particular, has been associated with poor dietary intake and the development of diet-related diseases;13,20 potentially in part due to alterations in metabolic hormone regulation, as well as extended waking hours.5,11,21 Despite these potential links, little is known about the generalizability of the relationship between eating behaviours and sleep duration in adolescent populations. Thus, understanding this relationship is crucial for clinicians and researchers to better understand the complex relationships among sleep duration and diet-related diseases.22

The objectives of this scoping review were to systematically review the literature that examines sleep duration in relation to eating behaviours among adolescents, and to identify gaps and provide direction for future research in the field of adolescent health promotion.

Methods

This review follows the six-staged framework for scoping studies described by Arksey and O’Malley23 and recommendations outlined by Levac and colleagues24 to enhance the scoping review methodologies. The six stages of this framework are: (1) identifying the research question; (2)identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results; and (6) consultation exercise.23 The protocol for this study is available in further detail elsewhere.25 This review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.26,27

Identifying the research questions

The primary research question guiding this scoping review was: what is the nature of the research on the relationship between sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescents? Grounded in the objectives of performing a scoping review—to map the key concepts and evidence available on a research topic—the secondary research questions were: (1) which research designs have been employed?; (2) which adolescent populations have been studied?; (3) which outcome variables have been assessed?; and (4) what questions remain to be addressed? Methodological quality of the studies was not assessed, given the primary purpose of conducting a scoping review.23

Identifying relevant studies

To identify relevant studies, systematic searches were conducted on PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Scopus. The most recent search strategy ( Table 1 ) was executed on 17 November 2021. Grey literature studies were also reviewed using the template provided by Godin et al.28 Using this guideline, a targeted search of relevant health organization websites and public health databases was conducted. The grey literature search was conducted on 20 March 2020.

Table 1. Keywords and search terms employed in the systematic search.

|

Selecting the studies

The studies were screened to ensure that findings reported on the association between sleep duration and eating behaviours among adolescents (approximately 13–19 years of age). No restrictions were placed on research approaches, study design or study type. Studies that solely examined infants, toddlers, preschoolers, school-aged children, adults or older adults were excluded. Only studies reported in English and in the form of a publication, thesis, dissertation, technical report or conference proceedings were included in the final review.

Studies were screened using a two-level screening process to determine eligibility. Studies were first reviewed based on the title and abstract, and then selected for inclusion in the final review based on reading the article in full. In the first stage, the title and abstract of each study were independently screened by one reviewer to determine potential eligible studies. In the second stage, the full text of each study was screened by two reviewers, after which the reviewers met to discuss the cases for which the decision was not unanimous, in order to reach consensus.

Charting the data

The data extraction stage followed the two-step recommendations by Daudt et al.29 To ensure the validity of the data extracted, the review team met to discuss the data extraction protocol. Following that, each member of the review team independently extracted data from articles that were purposely chosen to represent a range of themes and study designs. After independently extracting data from the same set of studies, the review team reconvened to discuss discrepancies before independently extracting data from the remaining studies. Key characteristics were extracted and recorded using a spreadsheet, including publication, study and population characteristics. Data pertaining to the research focus on sleep duration and eating behaviours were extracted. The first author reviewed the data extracted from all studies for accuracy.

Collating, analyzing and synthesizing the data

The charted data were collated, analyzed and synthesized to summarize the current body of literature on sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescent populations. This summary is presented in the form of aggregate numeric values and narrative descriptions in the results section. The findings are grouped under two primary domains: food consumption and eating habits.

Consulting stakeholders

Based on the grey literature review, three stakeholders were identified, and two were contacted via email. These two stakeholders were specifically consulted based on their content expertise (e.g. adolescent health, eating- and weight-related behaviours) and profession. One was a researcher and clinician, and the other was a clinician and community worker. Both stakeholders agreed to participate in a consultation for this scoping review. The first stakeholder was a youth health researcher, with frontline clinical experiences, specializing in population-level primary prevention and health promotion research. The second stakeholder was an education and outreach coordinator and psychotherapist, for a national organization that delivers community education and school-based prevention programming. During the consultations, the first author shared preliminary findings and validated the interpretations with the stakeholders. Stakeholders were solicited for their perspectives on important directions for future research in the field and provided relevant articles for the team to review. The perspectives gathered through the consultation exercise guided the reporting and interpretation of the results. The areas identified as priorities for future research were used to frame the discussion of the results.

Results

Study selection

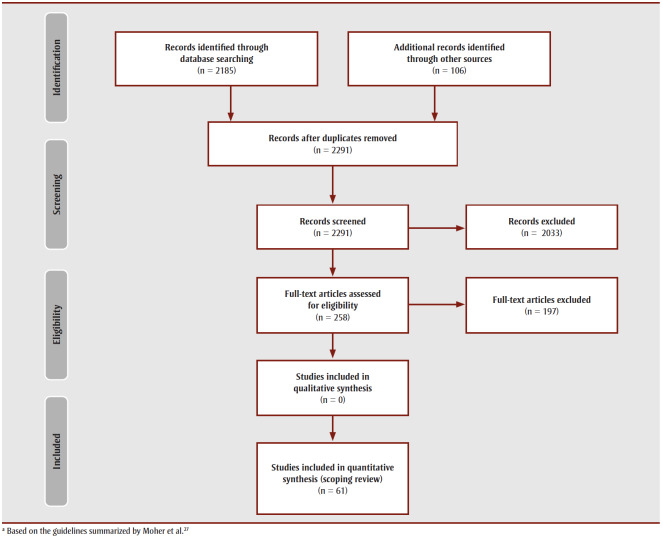

The systematic and grey literature searches yielded 2185 and 106 citations, respectively. After removing duplicates, the remaining 2291 citations were screened. A total of 61 articles from the systematic and grey literature searches met eligibility criteria and were included in the final synthesis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart.

Publication, study and population characteristics

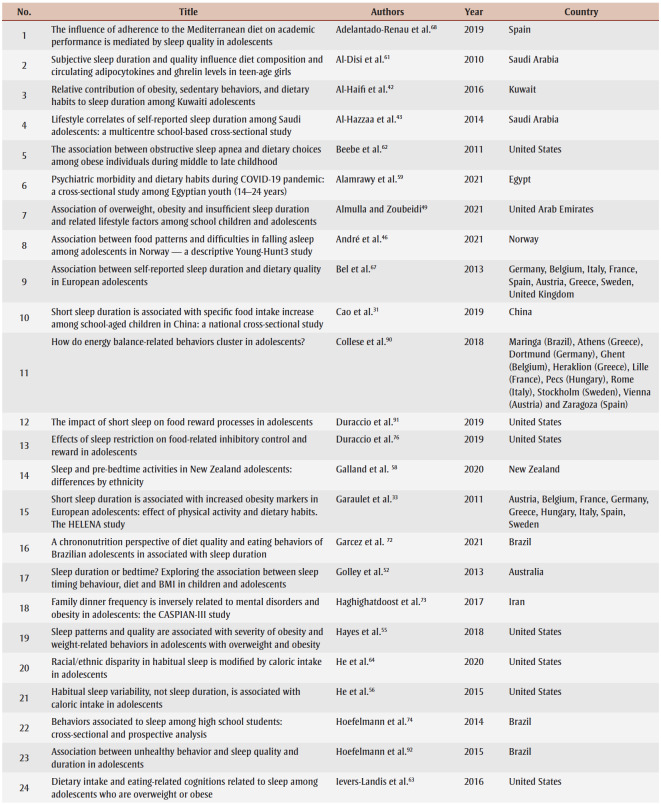

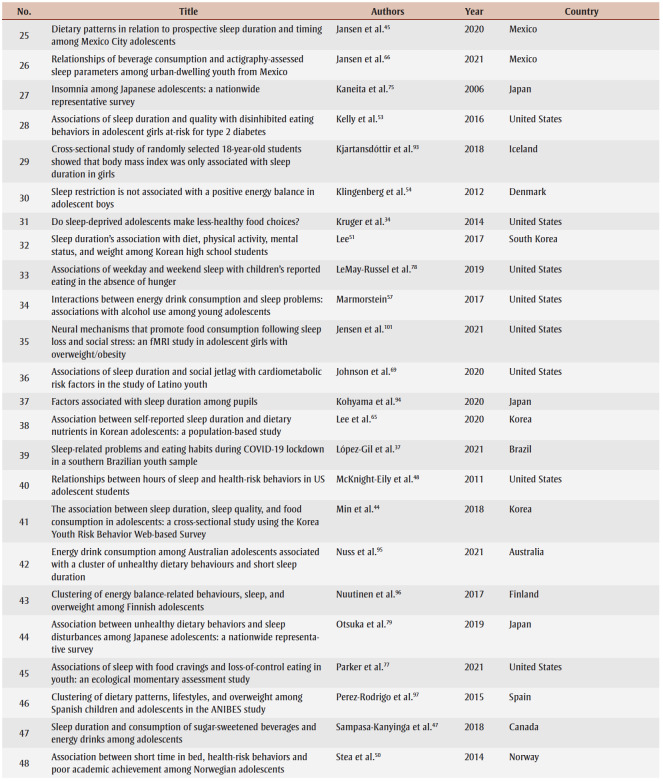

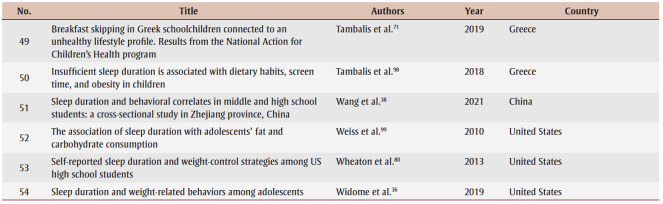

Tables 2 and 3 present the study characteristics of the peer-reviewed and grey literature studies included in the final review, respectively. All studies were published between 2006 and 2021. Most of the studies were conducted in North America (36.1%), Europe (23.0%) and East Asia (13.1%). The sample size of the included studies ranged from 21 to 1777091, with a median sample size of 1522.

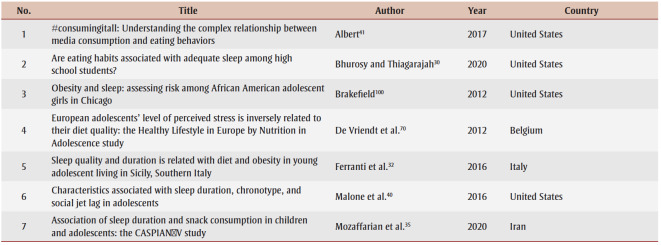

Table 2. Publication characteristics of the studies included from the systematic search.

Table 3. Publication characteristics of the studies included from the grey literature review.

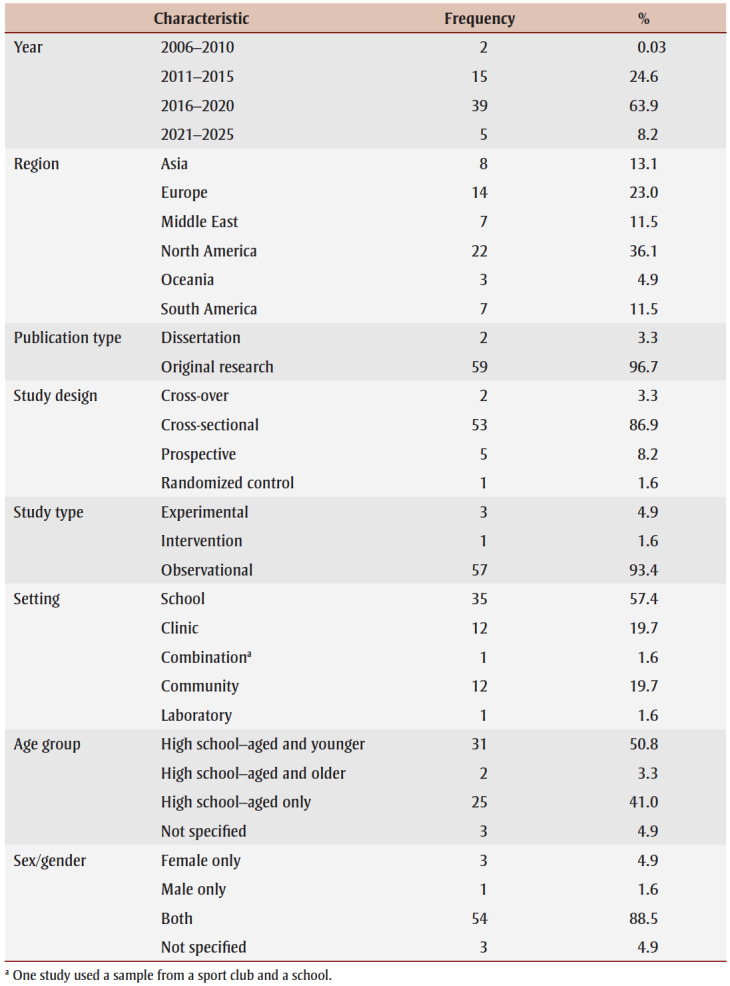

Table 4 presents the study and population characteristics of the 61 included studies. Most studies published on this topic used a cross-sectional design (86.9%), were observational in nature (93.4%) and took place in a school setting (57.4%). Many studies exclusively examined adolescents within the high school age range (41.0%); however, some also included younger (50.8%) or older (3.3%) adolescents in their sample. With the exception of four (and three that did not specify), most studies examined both males and females (88.5%).

Table 4. Study characteristics of included studies.

|

The published research in this domain predominantly used self-report measures of sleep duration; 72.1% of the studies included in our review used such self-report measures (e.g. questionnaire, sleep diary, interview recall, guardian report). Objective measures of sleep duration were used in 16.4% of studies (e.g. actigraphy, accelerometer, polysomnography) and a combination of self-report and objective measures of sleep duration were used in 9.8% of the studies (data not shown).

Most studies examined multiple aspects of eating behaviours using self-report measures. In 72.1% of studies, self-report questionnaires were used and in 14.8% of studies, interview methods were used to obtain a measure of dietary intake. In 6.6% of studies, objective measures of dietary intake, such as analysis of meal orders and absolute caloric intake, were used. Two studies assessed eating behaviours using experimental tasks (3.3%). One study used food records (1.6%), and another used a combination of 24-hour recall and food records (1.6%).

Research focus on sleep duration and eating behaviour studies

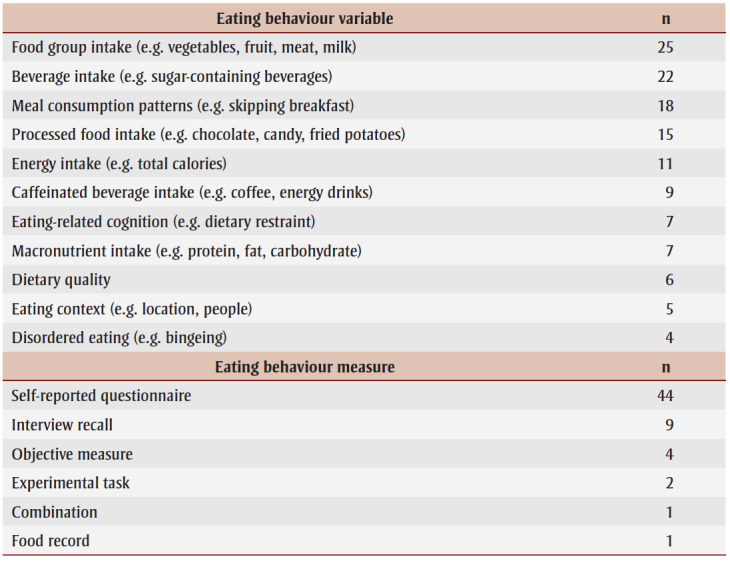

Table 5 presents the frequency with which the research foci were reported in the literature.

Table 5. Research focus of sleep duration and eating behaviour research.

|

Food consumption

Food group intake

Indicators of food groups were represented in the largest number of studies. The food group most commonly assessed was fruit and vegetables. Among studies that examined fruit and vegetable intake, findings were mixed. Ten studies found that vegetable consumption was positively associated with sufficient sleep.30-39 One study found that higher intake of fruit and vegetables was associated with shorter self-reported sleep duration.40 One study found that longer sleep duration was associated with higher fruit and vegetable consumption in males, but not females.41 Two studies did not reveal any significant associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and sleep duration.42,43 Eight studies reported on intake of milk and dairy products, meat and alternatives and grain products, and the findings were mixed.30,31,33,35,42,44,45,46

Beverage intake

Beverage intake was the second most frequently examined variable. A number of studies observed that short sleep was associated with greater intake of sugar-sweetened beverages31,35,36,42,47 and soft drinks.44,48,49 One study observed that short sleep was associated with lower odds of intake of soft drinks without sugars.35

Processed food intake

Studies frequently reported on intake of processed foods, including fast food, sweets and salty snacks. Among these studies, it was often reported that short sleep was associated with higher consumption of fast food,34,42 sweets32,42,44,50 and salty snacks,32,35,51 with the exception of one study that did not find a significant association between sleep duration and fast food consumption.38

Energy intake

Energy intake, or caloric intake, was a common indicator examined among the studies. Studies reported mixed findings regarding the direction and significance of the relationship between sleep duration and energy intake. Some studies reported findings that suggest that short sleep duration was associated with higher energy intake,52,53 while one study reported short sleep duration was associated with a small negative energy balance,54 and two reported insignificant findings.55,56

Caffeinated beverage intake

Nine studies examined the associations between sleep duration and caffeinated beverages.35,36,42,47,49,51,57-59 Of these, four reported significant findings that consumption of caffeinated beverages was associated with shorter sleep duration.47,49,57,58 One study found that short sleep was associated with a decreased intake of coffee.35

Macronutrient intake

Intake of macronutrients was reported in eight studies.56,60-66 Using 24-hour-food-recall questionnaires and wrist-actigraphy measures, one study found that those who slept less than eight hours consumed a higher proportion of calories from fat and a lower proportion of calories from carbohydrates, compared to adolescents sleeping eight hours or more.60 Another study observed that girls who slept less than five hours a night ate a higher proportion of carbohydrates.61

Dietary quality

Six studies assessed dietary quality.67-72 The findings related to dietary quality were mixed, with two studies reporting that insufficient sleep was associated with poorer dietary quality67,72 and another two studies reporting no significant relationship between sleep duration and dietary quality.68,69 Furthermore, one study reported a significant association between sleep duration and dietary quality in the context of the association between perceived stress and dietary quality.70

Eating habits

Meal consumption patterns

Among the studies that examined eating habits, meal consumption pattern was the most commonly examined in relation to sleep duration. Breakfast consumption was examined in all studies except one.59 Lunch, dinner and snack consumption was examined in a very few studies.73,74 Among the studies examining eating habits, it was commonly found that skipping a meal, especially breakfast, was associated with less optimal sleep duration.30,36-38,42,43,50,71 Two studies found that the prevalence of sleep disorders, such as insomnia, were higher for meal skippers.69,75

Eating-related cognitions

Cognitive factors associated with eating emerged as a theme in the literature. Using an experimental study design, one study found that following sleep restriction, adolescents performed more poorly on food-related inhibitory control,76 and another found that short sleep duration was associated with loss-of-control eating.77 Additionally, an interaction was identified whereby adolescents with a BMI in the normal weight range had a heightened response to food reward following sleep restriction. One study found that average weekday sleep duration was negatively associated with eating in the absence of hunger, and the reverse was observed for average weekend sleep duration.78

Eating contexts

Contextual factors surrounding eating were identified as a theme in the variables investigated. One study measured a number of weight-related behaviours, including eating habits such as eating when full.36 Another study found that sleep duration provided a partial explanation for the relationship between media consumption (e.g. listening to music, watching television, playing video games, instant messaging, emailing) and eating behaviours, but only for specific media and only in males.41 One study found that longer sleep duration was associated with fewer times eating outside of the home in a week.32 The findings from a study conducted in Japan indicated that short sleep duration was associated with family meal frequency.79

h5HDisordered eating

Two studies found that very short sleep duration was significantly associated with weight control strategies, such as fasting and purging and eating fewer calories, among adolescent boys and girls.38,80 Another study examined the associations among sleep duration, daytime sleepiness and disinhibited eating, including binge eating.53 One study observed that emotional and night eating emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, and was associated with symptoms of insomnia.59

Discussion

Summary of evidence

The objective of this scoping review was to explore and synthesize the literature on sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescents. In total, 61 articles were included in this synthesis. This review also mapped out the characteristics of existing research by examining the research designs, study populations, outcome variables and research gaps in the current body of literature. To our knowledge, this is the first synthesis published on the topic.

The majority of studies were observational, employed a cross-sectional design, used a school-based population and were published in North America. With respect to methodologies used when assessing eating behaviours, the review identified that the current research focussed heavily on the intake of food and beverages through self-reported questionnaires. This synthesis also revealed a heavy emphasis on eating behaviours related to food group intakes, such as fruit and vegetables. Intakes of beverages and processed food were also very commonly investigated variables.Surprisingly, few studies examined eating habitsin relation to sleep duration. Among the studies that examined eating habits, the majority focussed on breakfast consumption, with very few studies including measures of eating-related cognitions, eating contexts or disordered eating.

A prominent gap in the literature is the limited examination of eating habits as opposed to food consumption. Only four studies examined the contextual factors that surround eating, including eating in the absence of hunger, eating with family and friends and eating while consuming media, in relation to sleep duration in adolescents. This gap is critical to address because of the influence of sleep on eating behaviours, and the increasing recognition of the role of eating habits in overall healthy eating practices.3,81 Therefore, further investigation into the connections between sleep duration and eating habits of adolescents is warranted.

An area that remains to be addressed is how sleep duration is implicated in disordered eating behaviours among adolescents. Previous research has identified that disordered eating and eating disorders often emerge during adolescence and early adulthood.82 However, there is limited research examining the association between sleep duration and disordered eating among adolescents. Of particular relevance to this review is the role of insufficient sleep on binge eating. Research demonstrates that inadequate sleep is associated with binge eating, partly due to decreasing leptin (reduces appetite) and increasing ghrelin (stimulates appetite).83 However, chronic energy restriction has also been demonstrated to compromise sleep health through mechanisms such as reducing orexin, which plays a role in regulating arousal, hunger and wakefulness,84 and compromising sleep by increasing wake time and shallow sleep.85 Considering the bidirectional nature of the relationship between sleep and disordered eating, this area of research requires further investigation.

Additionally, two factors that impact sleep duration and eating behaviours that were not adequately addressed are the role of stress, and changes in metabolic hormones. Research demonstrates that stressful life events impact sleep through alterations to the duration and quality of sleep; however, very few studies reviewed in this synthesis examined the influence of stress on the eating behaviours of adolescents. Research also demonstrates that those experiencing shorter sleep and stress exhibit changes in metabolic hormones (e.g. reduced leptin and elevated ghrelin), which likely contributes to an increase in appetite and changes in eating behaviours8,86 and altered inhibitory control.76 Therefore, addressing this gap in the literature is crucial to better understanding the potential moderating effects of stress on sleep and eating-related cognitions, such as eating in the absence of hunger and disinhibited eating.

The overwhelming majority of studies published on this topic used a cross-sectional approach and were observational in nature. Self-report measures were used the majority of the time as indicators of sleep duration and eating behaviours. To develop a clearer understanding of the nature of the relationship between sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescents, a wider variety of research designs and methods should be employed. The predominantly cross-sectional nature of the study designs and analyses does not enable inferences into the temporality of the associations observed. Future studies using a prospective cohort design are required to assess the temporality and bidirectional nature of the associations between sleep duration and eating behaviours.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this review is that we included the optional step of engaging stakeholders.23 By engaging stakeholders, we were able to share and validate preliminary findings and solicit the perspectives of researchers and clinicians working in the community. Additionally, reliability checks were conducted throughout the scoping review, incorporating steps such as having two or more members of the research team review articles during the data selection and extraction stages.

There are limitations to this review. Unlike other kinds of reviews (e.g. systematic, meta-analytical), scoping reviews are not designed to evaluate the strength of associations between the variables or the quality of studies that were reviewed.87,88 Thus, neither the strength of the associations observed nor the quality of the included studies in our review were assessed. Instead, scoping reviews are used to gather information from a range of study designs and methods in order to identify the types of evidence available in a given field and to identify knowledge gaps; they can serve as a precursor to a systematic review.89

Another limitation to this review is that only studies published in English were screened.

Finally, there is a possibility that relevant articles were inadvertently excluded. Although the search strategy was designed in consultation with subject specialist librarians, less commonly used terms in the literature may have been overlooked in the final search strategy.

Conclusion

Although research on sleep duration and eating behaviours in adolescent populations has been increasingly published in the past decade, much remains to be examined in this field. Further research on this topic is necessary in order to better understand how ensuring sufficient sleep among adolescents can support healthier eating practices. Future research should investigate how insufficient sleep may impact the eating habits of adolescents, including eating-related cognition, eating contexts and disordered eating behaviours. These lines of inquiry could contribute to supporting healthy eating among adolescents and informing behavioural interventions aimed at managing diet-related conditions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the liaison librarians at the University of Waterloo for their guidance in developing the literature search strategy and review protocol.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors contributed meaningfully to the preparation, drafting and editing of this paper. ND designed the protocol and led all aspects of the study, including data collection, extraction, charting, synthesis, stakeholder consultations and writing. AP, KR and EVB engaged in data collection and extraction. KR wrote the introduction, ND wrote the methods and results and AP wrote the discussion. EVB critically reviewed all components of the manuscript. MAF supervised the research, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Bacon SL, Raine KD, et al, Pharm J, et al. Canada’s new Healthy Eating Strategy: implications for health care professionals and a call to action. Can Pharm J. 2019;152((3)):151–157. doi: 10.1177/1715163519834891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenga L, Montez JM, et al. Health effects of saturated and trans-fatty acid intake in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12((11)):e0186672–157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Ottawa(ON): Canada’s food guide [Internet] Available from: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Haerens L, Craeynest M, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. The contribution of psychosocial and home environmental factors in explaining eating behaviours in adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62((1)):51–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- rdova F, Barja S, Brockmann P, et al. Consequences of short sleep duration on the dietary intake in children: a systematic review and metanalysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018:68–84. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capers P, Fobian A, Kaiser K, Borah R, Allison D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the impact of sleep duration on adiposity and components of energy balance. Obes Rev. 2015;16((9)):771–82. doi: 10.1111/obr.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, et al. Sleep and obesity risk in adults: possible mechanisms; contextual factors; and implications for research, intervention, and policy. Sleep Health. 2017;3((5)):393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S, Lin L, Austin D, Young T, Mignot E, et al. Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index. PLoS Med. 2004;1((3)):e62–400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows T, Fenton S, Duncan M, et al. Diet and sleep health: a scoping review of intervention studies in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33((3)):308–29. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton S, Burrows T, Skinner J, Duncan M, et al. The influence of sleep health on dietary intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2021:273–85. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2014:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. 2018 Available from: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lohner S, dy K, r D, et al. Relationship between sleep duration and childhood obesity: systematic review including the potential underlying mechanisms. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27((9)):751–61. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA, et al. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. sleep. 2007;8((6)):602–12. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CE, Poitras VJ, et al, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41((6 Suppl 3)):S266–S282. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte KA, Qian W, Leatherdale ST, et al. Sleep duration trends and trajectories among youth in the COMPASS study. Sleep Health. 2017;3((5)):309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y, et al. Restricted sleep among adolescents: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med. 2011;9((1)):18–30. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.533991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSEP. Ottawa(ON): Children (5–11 years) and youth (12–17 years) [Internet] Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/guidelines/children-youth. [Google Scholar]

- Owens J, et al. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics. 2014:e921–e932. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DW, Simon S, Summer S, Hemmer S, Strotman D, Dolan LM, et al. Dietary intake following experimentally restricted sleep in adolescents. Sleep. 2013;36((6)):827–34. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godos J, Grosso G, Castellano S, Galvano F, Caraci F, Ferri R, et al. Association between diet and sleep quality: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashti H, Scheer F, Jacques P, Fava S, s J, et al. Short sleep duration and dietary intake: epidemiologic evidence, mechanisms, and health implications. Adv Nutr. 2015;6((6)):648–59. doi: 10.3945/an.115.008623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L, et al. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien K, et al. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan N, Ferro MA, et al. Sleep duration and eating behaviours in youth: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9((12)):e030457–32. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169((7)):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009:b2535–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST, et al. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt HM, Mossel C, Scott SJ, et al. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013:48–73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhurosy T, Thiagarajah K, et al. Are eating habits associated with adequate sleep among high school students. J Sch Health. 2020;90((2)):81–7. doi: 10.1111/josh.12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Zhu Y, Sun F, Luo J, Jing J, et al. Short sleep duration is associated with specific food intake increase among school-aged children in China: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19((1)):558–7. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6739-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferranti R, Marventano S, Castellano S, et al, et al. Sleep quality and duration is related with diet and obesity in young adolescent living in Sicily, Southern Italy. Sleep Sci. 2016;9((2)):117–22. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaulet M, Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, et al, et al. Short sleep duration is associated with increased obesity markers in European adolescents: effect of physical activity and dietary habits. Int J Obes. 2011:1308–17. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger AK, Reither EN, Peppard PE, Krueger PM, Hale L, et al. Do sleep-deprived adolescents make less-healthy food choices. Br J Nutr. 2014;111((10)):1898–904. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian N, Heshmat R, Ataie-Jafari A, et al, et al. Association of sleep duration and snack consumption in children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-V study. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8((4)):1888–97. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widome R, Lenk KM, Laska MN, et al, et al. Sleep duration and weight-related behaviors among adolescents. Child Obes. 2019;15((7)):434–42. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- pez-Gil JF, Gaya AR, Reuter CP, et al, et al. Sleep-related problems and eating habits during COVID-19 lockdown in a southern Brazilian youth sample. Sleep Med. 2021:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Zhong JM, Hu RY, Gong WW, Yu M, et al. Sleep duration and behavioral correlates in middle and high school students: a cross-sectional study in Zhejiang province, China. Sleep Med. 2021:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcez MR, Castro MA, sar CL, Goldbaum M, Fisberg RM, et al. A chrononutrition perspective of diet quality and eating behaviors of Brazilian adolescents in associated with sleep duration. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38((3)):387–99. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1851704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone SK, Zemel B, Compher C, et al, et al. Characteristics associated with sleep duration, chronotype, and social jet lag in adolescents. J Sch Nurs. 2016:120–31. doi: 10.1177/1059840515603454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert SL, et al. #consumingitall: Understanding the complex relationship between media consumption and eating behaviors [dissertation] #consumingitall: Understanding the complex relationship between media consumption and eating behaviors [dissertation]. [Los Angeles]: University of California; 2017. 2017 Available from: https://www.proquest.com/docview/1914676841?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview;=true. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haifi AA, AlMajed HT, Al-Hazzaa HM, Musaiger AO, Arab MA, Hasan RA, et al. Relative contributions of obesity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits to sleep duration among Kuwaiti adolescents. Global J Health Sci. 2016;8((1)):107–17. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hazzaa HM, Musaiger AO, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, et al. Lifestyle correlates of self-reported sleep duration among Saudi adolescents: a multicentre school-based cross-sectional study. Child Care Health Dev. 2014:533–42. doi: 10.1111/cch.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C, Kim HJ, Park IS, et al, et al. The association between sleep duration, sleep quality, and food consumption in adolescents: a cross-sectional study using the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey. BMJ Open. 2018:e022848–42. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EC, Baylin A, Cantoral A, et al, et al. Dietary patterns in relation to prospective sleep duration and timing among Mexico City adolescents. Nutrients. 2020;12((8)):2305–42. doi: 10.3390/nu12082305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- o H, Espnes GA, et al, et al. Association between food patterns and difficulties in falling asleep among adolescents in Norway—a descriptive Young-Hunt3 study. J Public Health. 2021;29((6)):1373–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, et al. Sleep duration and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and energy drinks among adolescents. Nutrition. 2018:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily LR, Eaton DK, Lowry R, Croft JB, Presley-Cantrell L, Perry GS, et al. Relationships between hours of sleep and health-risk behaviors in US adolescent students. YPMED. 2011;53((4-5)):271–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almulla AA, Zoubeidi T, et al. Association of overweight, obesity and insufficient sleep duration and related lifestyle factors among school children and adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2021;34((2)):31–40. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2021-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea TH, Knutsen T, Torstveit MK, et al. Association between short time in bed, health-risk behaviors and poor academic achievement among Norwegian adolescents. Sleep Med. 2014;15((6)):666–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, et al. Sleep duration’s association with diet, physical activity, mental status, and weight among Korean high school students. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26((5)):906–13. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.082016.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golley RK, Maher CA, Matricciani L, Olds TS, et al. Sleep duration or bedtime. Int J Obes. 2013;37((4)):546–51. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly NR, Shomaker LB, Radin RM, et al, et al. Associations of sleep duration and quality with disinhibited eating behaviors in adolescent girls at-risk for type 2 diabetes. Eat Behav. 2016:149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg L, ck U, Jennum P, Astrup A, din A, et al. Sleep restriction is not associated with a positive energy balance in adolescent boys. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96((2)):240–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.038638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JF, Balantekin KN, Altman M, Wilfley DE, Taylor BC, Williams J, et al. Sleep patterns and quality are associated with severity of obesity and weight-related behaviors in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Child Obes. 2018;14((1)):11–17. doi: 10.1089/chi.2017.0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Bixler EO, Berg A, et al, et al. Habitual sleep variability, not sleep duration, is associated with caloric intake in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2015;16((7)):856–61. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, et al. Interactions between energy drink consumption and sleep problems: associations with alcohol use among young adolescents. J Caffeine Res. 2017;7((3)):111–6. doi: 10.1089/jcr.2017.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galland BC, Wilde T, Taylor RW, Smith C, et al. Sleep and pre-bedtime activities in New Zealand adolescents: differences by ethnicity. Sleep Health. 2020;6((1)):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamrawy R, Fadl N, Khaled A, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and dietary habits during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study among Egyptian Youth (14–24 years) Middle East Curr Psychiatry. 2021;28((1)):6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R, Stumbo PJ, Divakaran A, et al. Automatic food documentation and volume computation using digital imaging and electronic transmission. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110((1)):42–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Disi D, Al-Daghri N, Khanam L, et al, Endocr J, et al. Subjective sleep duration and quality influence diet composition and circulating adipocytokines and ghrelin levels in teen-age girls. Endocr J. 2010;57((10)):915–23. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DW, Miller N, Kirk S, Daniels SR, Amin R, et al. The association between obstructive sleep apnea and dietary choices among obese individuals during middle to late childhood. Sleep Med. 2011;12((8)):797–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ievers-Landis CE, Kneifel A, Giesel J, et al, et al. Dietary intake and eating-related cognitions related to sleep among adolescents who are overweight or obese. J Ped Psychol. 2016;41((6)):670–9. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Dong H, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Bixler EO, Liao J, Liao D, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in habitual sleep is modified by caloric intake in adolescents. Sleep Med. 2020:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Chung SJ, Seo WH, et al. Association between self-reported sleep duration and dietary nutrients in Korean adolescents: a population-based study. Children. 2020;7((11)):221–71. doi: 10.3390/children7110221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EC, Corcoran K, Perng W, et al, et al. Relationships of beverage consumption and actigraphy-assessed sleep parameters among urban-dwelling youth from Mexico. Public Health Nutr. :1–10. doi: 10.1017/S136898002100313X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bel S, Michels N, Vriendt T, et al, et al. Association between self-reported sleep duration and dietary quality in European adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2013;110((5)):949–59. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512006046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelantado-Renau M, Beltran-Valls MR, Esteban-Cornejo I, no V, as AM, Urdiales D, et al. The influence of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on academic performance is mediated by sleep quality in adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108((2)):339–46. doi: 10.1111/apa.14472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Reid M, Vu TH, et al, et al. Associations of sleep duration and social jetlag with cardiometabolic risk factors in the study of Latino youth. Sleep Health. 2020;6((5)):563–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriendt T, Clays E, Huybrechts I, et al, et al. European adolescents’ level of perceived stress is inversely related to their diet quality: The Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108((2)):371–80. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, Sidossis LS, et al. Breakfast skipping in Greek schoolchildren connected to an unhealthy lifestyle profile. Nutr Diet. 2019:328–35. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcez MR, Castro MA, sar CL, Goldbaum M, Fisberg RM, et al. A chrononutrition perspective of diet quality and eating behaviors of Brazilian adolescents in associated with sleep duration. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38((3)):387–99. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1851704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighatdoost F, Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, et al, et al. Family dinner frequency is inversely related to mental disorders and obesity in adolescents: the CASPIAN-III study. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20((4)):218–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefelmann LP, Silva KS, Filho VC, Silva JA, Nahas MV, et al. Behaviors associated to sleep among high school students: cross-sectional and prospective analysis. Rev Bras Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2014:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Osaki Y, et al, et al. Insomnia among Japanese adolescents: a nationwide representative survey. Sleep. 2006;29((12)):1543–50. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraccio KM, Zaugg K, Jensen CD, et al. Effects of sleep restriction on food-related inhibitory control and reward in adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019:692–702. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsz008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MN, LeMay-Russell S, Schvey NA, et al, et al. Associations of sleep with food cravings and loss-of-control eating in youth: an ecological momentary assessment study. Pediatr Obes. 2021:e12851–702. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMay-Russell S, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Schvey NA, et al, et al. Associations of weekday and weekend sleep with children’s reported eating in the absence of hunger. Nutrients. 2019:1658–702. doi: 10.3390/nu11071658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka Y, Kaneita Y, Itani O, et al, et al. Association between unhealthy dietary behaviors and sleep disturbances among Japanese adolescents: a nationwide representative survey. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2019;17((1)):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton AG, Perry GS, Chapman DP, Croft JB, et al. Self-reported sleep duration and weight-control strategies among US high school students. Sleep. 2013:1139–45. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- nd ed, et al. Dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population. Ministry of Health of Brazil. Available from: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view;=article&id;=11564:dietary-guidelines-brazilian-population&Itemid;=4256⟨=en. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, HG Jr, Kessler RC, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61((3)):348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trace SE, Thornton LM, Runfola CD, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, Bulik CM, et al. Sleep problems are associated with binge eating in women. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45((5)):695–703. doi: 10.1002/eat.22003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JF, Choi DL, Benoit SC, Preedy V, Watson R, Martin C, et al. Orexigenic hypothalamic peptides behavior and feeding. Springer. :355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer CJ, et al. Sleep in eating disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8((2)):109–18. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(02)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macedo DM, Diez-Garcia RW, et al. Sweet craving and ghrelin and leptin levels in women during stress. Appetite. 2014:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucharew H, Macaluso M, et al. Methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. J Hosp Med. 2019;14((7)):416–18. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A, et al. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5((3)):101–17. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E, et al. Systematic review or scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018:143–17. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collese TS, Moraes AC, Alvira JM, et al, et al. How do energy balance-related behaviors cluster in adolescents. Int J Public Health. 2019;64((2)):195–208. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraccio KM, Krietsch KN, Zhang N, et al, et al. The impact of short sleep on food reward processes in adolescents. J Sleep Res. 2021;30((2)):e13054–208. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefelmann LP, Silva KS, Lopes AD, et al, et al. Association between unhealthy behavior and sleep quality and duration in adolescents. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum. 2015:318–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kjartansdottir I, Arngrimsson SA, Bjarnason R, Olafsdottir AS, et al. Cross-sectional study of randomly selected 18-year-old students showed that body mass index was only associated with sleep duration in girls. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107((6)):1070–6. doi: 10.1111/apa.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama J, Ono M, Anzai Y, et al. Factors associated with sleep duration among pupils. Ped Int. 2020;62((6)):716–24. doi: 10.1111/ped.14178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss T, Morley B, Scully M, Wakefield M, Nutr J, et al. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr J. 2021:64–24. doi: 10.1186/s12937-021-00719-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutinen T, Lehto E, Ray C, Roos E, Villberg J, et al. Clustering of energy balance-related behaviours, sleep, and overweight among Finnish adolescents. Int J Public Health. 2017:929–38. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-0991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- rez-Rodrigo C, Gross M, et al, et al. Clustering of dietary patterns, lifestyles, and overweight among Spanish children and adolescents in the ANIBES study. Nutrients. 2015;8((1)):11–38. doi: 10.3390/nu8010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, Sidossis LS, et al. Insufficient sleep duration is associated with dietary habits, screen time, and obesity in children. J Clinical Sleep Med. 2018:1689–96. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Xu F, Storfer-Isser A, Thomas A, Ievers-Landis CE, Redline S, et al. The association of sleep duration with adolescents’ fat and carbohydrate consumption. Sleep. 2010;33((9)):1201–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield T, et al. Obesity and sleep: assessing risk among African American adolescent girls in Chicago [dissertation] [Chicago]: Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science; 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CD, Zaugg KK, Muncy NM, et al, et al. Neural mechanisms that promote food consumption following sleep loss and social stress: an fMRI study in adolescent girls with overweight/ obesity. Sleep. 2022;45((3)):zsab263–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]