ABSTRACT

This article provides a snapshot of the market structure and regulatory approaches around novel and emerging tobacco and nicotine products, both globally and in Latin America, with a focus on excise taxation. Using data from leading market research companies, the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021, and country laws and decrees, the article analyses the evolution and market structure of heated tobacco products (HTPs), electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS). This is followed by a summary review of regulatory approaches adopted by countries toward these products, with a particular focus on excise tax policies currently implemented. Based on the well-established knowledge about tobacco taxation best practices and on WHO’s recent recommendations on the taxation of novel and emerging tobacco and nicotine products, the authors then discuss possible elements of a good tax policy approach for countries to consider.

Keywords: Taxation of the tobacco-derived products, tobacco products, electronic nicotine delivery systems, health policy, Latin America

RESUMEN

En este artículo se presenta una sinopsis de la estructura del mercado y los enfoques regulatorios de los productos nuevos y emergentes de nicotina y tabaco, tanto en América Latina como a nivel mundial, con especial atención a los impuestos selectivos al consumo. Mediante datos de las principales empresas de investigación de mercado, el Informe OMS sobre la epidemia mundial de tabaquismo del 2021 y las leyes y los decretos de los países, en este artículo se analizan la evolución y la estructura del mercado de los productos de tabaco calentado (PTC), los sistemas electrónicos de administración de nicotina (SEAN) y los sistemas electrónicos sin nicotina (SESN). Además, se resumen los enfoques regulatorios adoptados por los países en lo relativo a estos productos, prestando particular interés a las políticas que se aplican actualmente con respecto al impuesto selectivo al consumo. Sobre la base de conocimientos bien consolidados sobre las mejores prácticas de tributación del tabaco y las recientes recomendaciones de la OMS sobre la tributación de los productos nuevos y emergentes de nicotina y tabaco, los autores presentan a consideración de los países los posibles elementos de un enfoque para abordar la política tributaria de forma satisfactoria.

Palabras clave: Tributación de los productos derivados del tabaco, productos de tabaco, sistemas electrónicos de liberación de nicotina, política de salud, América Latina

RESUMO

Este artigo fornece um retrato da estrutura de mercado e das abordagens regulatórias dos produtos novos e emergentes de tabaco e nicotina, tanto globalmente quanto na América Latina, com foco na tributação sobre o consumo. Utilizando dados das principais empresas de pesquisa de mercado, do Relatório da OMS sobre a Epidemia Global do Tabaco 2021 e de leis e decretos dos países, o artigo analisa a evolução e a estrutura do mercado de produtos de tabaco aquecido (HTPs, sigla do inglês heated tobacco products), sistemas eletrônicos de liberação de nicotina (ENDS, sigla do inglês electronic nicotine delivery system) e sistemas eletrônicos sem nicotina (ENNDS, sigla do inglês electronic non-nicotine delivery system). Segue-se uma breve revisão das abordagens regulatórias adotadas pelos países em relação a esses produtos, com enfoque especial nas políticas tributárias sobre o consumo atualmente implementadas. A seguir, os autores discutem possíveis elementos de uma abordagem adequada de política tributária a serem considerados pelos países, com base no conhecimento já bem estabelecido sobre as melhores práticas de tributação do tabaco e nas recentes recomendações da OMS para a tributação de produtos novos e emergentes de tabaco e nicotina.

Palavras-chave: Tributação de produtos derivados do tabaco, produtos do tabaco, sistemas eletrônicos de liberação de nicotina, política de saúde, América Latina

In the Region of the Americas, notable progress has been made in the understanding of the role of excise taxes—defined here as taxes that apply to a few selected commodities—on tobacco products as an instrument to reduce tobacco use and improve population health. This has been driven by an abundance of supporting evidence, including the effectiveness of tobacco taxes and tobacco demand analyses (1); simulation modeling on the impact of tobacco taxes on price, sales, and revenue (2); independent studies on the extent of illicit trade in tobacco products (3); and comprehensive guidelines for the design and administration of tobacco taxes (4). Yet, translation of the evidence in favor of tobacco taxation into actual policy change has not been near commensurate. Indeed, tobacco taxation (measure R) is the least implemented measure at the highest level of achievement in the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) MPOWER package of measures for tobacco control (5). Keeping all of this in mind, it is not surprising that novel and emerging nicotine and tobacco products—around which the evidence base is still developing, and market dynamics are still evolving—pose challenges that further complicate regulatory efforts (4). Regulatory approaches toward these products have in recent years become a heated point of debate among policymakers and researchers, demanding careful consideration. In practice, the heterogeneity in regulation of these products is evident: while some countries have completely banned sale inside their markets, many other countries are still struggling to determine what is the best approach. Where the sale of these products has not been banned, effective regulation, including taxation, is a key policy to determine in line with decisions taken by the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the international treaty, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) (6, 7).

Novel products typically cover heated tobacco products (HTPs), electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS), and nicotine pouches. This article focuses on HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products only, given the availability of information in relation to their regulation.

HTPs are products that contain tobacco, nicotine, and non-tobacco additives, usually presented in the shape of cigarettes (e.g., heat stick or neo stick) or pods or plugs, which are often flavored. The tobacco in HTPs is heated by a device; this produces aerosols that contain nicotine and other toxic chemicals (8). The COP of the WHO FCTC has recognized HTPs as a tobacco product, confirming that they fall under the provisions of the treaty, calling for an equal regulatory approach for HTPs and any other conventional tobacco product (7). ENDS products heat a solution (called e-liquid) that contains nicotine and other additives, flavors, and chemicals to create an aerosol that is inhaled by the user. ENDS products are not tobacco products, although some countries have regulated them as tobacco products (e.g., Jamaica and Paraguay) (9). ENNDS products are the same as ENDS except that the e-liquid that is heated does not normally contain nicotine. The most commonly used type of ENDS product is electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), but ENDS also include other products such as e-hookahs, e-pipes, or e-cigars (5).

The COP of the WHO FCTC has issued guidance for the regulation of HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products such that the protection and promotion of human health is prioritized (6, 7). As there is no clear understanding of the long-term health effects of these products, and they are not inherently safe, policymakers need to ensure that the right levels of regulations are in place so that they do not encourage initiation by youths and non-smokers (4, 5, 8). This includes consideration to taxation of these products, taxation being a core component of a comprehensive regulatory approach in the context of tobacco control. Analyzing data from two leading market research companies, data from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021 (5), and country laws and decrees, this article provides a brief overview of the current market and regulatory fiscal landscape, with a focus on excise taxation, for HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products globally and, more specifically, in Latin American countries.1

GLOBAL OVERVIEW

Current market trends

Globally, HTPs have seen exceptional growth in a short time frame, with both market value and quantity growing at an exponential rate. According to Euromonitor, the market value in constant US$ increased from an estimated value of US$ 3.97 billion in 2013 to US$ 20.78 billion in 2020, with no signs of slowdown in the near future (10). In terms of quantity, the trend is similar, with the number of sticks sold increasing from an estimated 2.4 million in 2013 to 94.5 billion in 2020. The tobacco heating devices sales have also seen an increase from an estimated 41 557 units in 2013 to 20.7 million units in 2020 (10).2

The supply of HTPs appears to be very highly concentrated, with only a handful of companies catering to the demand of the top five markets (Japan, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Italy, and Germany) (11). In 2020, Philip Morris International’s brand IQOS held by far the largest market share in all five countries. Other key brands present in those markets are Glo (British American Tobacco—BAT), Ploom TECH and Ploom S (JTI), and Lil (Korea Tobacco & Ginseng Corporation—KT&G) (11).

In terms of sales trends, according to Euromonitor, ENDS and ENNDS products have experienced a strong growth of the market over time up until 2019 (from US$ 150 million in 2006 to US$ 20.5 billion in 2019), which was followed by a decrease in the growth rate since (sales value of US$ 21.2 billion in 2020).3 This may be due to the reduction in the market value of open systems, while the market value of closed systems continues to experience an increase in the growth rate. Open systems are devices where users can make their own mixes of the e-liquids they buy, which could be with no nicotine, different nicotine concentrations, and/or flavors. Closed systems come with a prefilled container (called a cartridge, pod, or tank) with no possibility for the users to make their own mixes. In terms of market share globally, closed systems held 64.1% of the market value in 2020 while open systems held 35.9% of the market value (11).

The market for ENDS and ENNDS products seems much more fragmented compared to HTPs, with more than 30 000 ENDS (devices and e-liquids) brands sold in the European Union alone (5). However, the market has been consolidating very rapidly, with Euromonitor estimating that in 2020 just three companies held 45.5% of the market share of ENDS and ENNDS products globally. The top company is Juul Labs Inc., followed by BAT and the Chinese company RELX Technology Co. Ltd. (10). With Altria having a 35% stake in Juul Labs (12) and BAT standing second globally in terms of sales in this sector (14.1% of global sales values in 2020) (10), it is clear that the tobacco industry is rapidly becoming an important player in the ENDS/ENNDS market, and not just in HTPs.

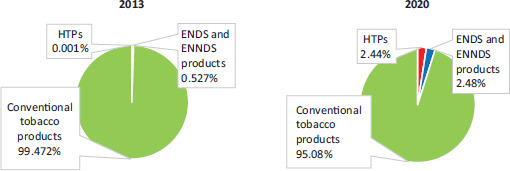

The market share of both HTPs and ENDS/ENNDS products remains very small compared to the share of conventional tobacco products, with each representing about 2.4%–2.5% of the total market value. However, as indicated earlier, those numbers are likely to be underestimates given Euromonitor’s limited coverage of countries for novel products (although the largest markets are included). In any case, those shares have been growing relatively fast over time, eating up more of the total value pie, as can be seen in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Market share in sales value of HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products and conventional tobacco products, 2013 and 2020.

Source: Figure prepared by the authors based on data from Euromonitor International, 2021 (10).

Tax structures applied globally and price levels

As of 2020, there were 11 countries banning HTPs sales (Brazil, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Mexico, Norway, Panama, Singapore, Syrian Arab Republic, and Timor-Leste) (5). Where they are not banned, at least 61 countries and one territory imposed an excise tax on those products. Table 1 summarizes the type of excise tax applied in those countries. Most countries apply a specific excise on HTPs based on the tobacco weight contained; those rates are generally lower than the cigarette excise tax rate. Only a handful apply the tax on the sticks and a fewer number impose the same tax as the one applied on cigarettes.

TABLE 1. Types of excises applied on HTPs, 2022.

|

Type of excise |

Countries (or territory) |

|---|---|

|

Specific excise |

|

|

Base unit: kg of tobacco |

Albania, Austria, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada,a Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Iceland, Indonesia,b Ireland, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Montenegro, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Pakistan, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, United Kingdom |

|

Base unit: sticks |

Armenia, Azerbaijan, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Peru, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Republic of Moldova,c South Africa, Ukraine,c United States of Americad |

|

Ad valorem excise |

|

|

Base: retail price |

Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay,e Spain, Switzerland |

|

Base: retail price exclusive of excise and VAT |

Saudi Arabia,e United Arab Emiratese |

|

Mixed system |

|

|

Base unit for specific: kg of tobacco |

Finland, France, Germany, Poland, |

|

Base unit for ad valorem: retail price |

Portugal |

|

Base unit for specific: sticks |

Colombia,e Georgiae |

|

Base unit for ad valorem: retail price |

|

|

Base unit for specific: sticks |

Israel,e Palestinian territoriese |

|

Base unit for ad valorem: wholesale price |

|

Notes:

This refers to the federal tax applied on HTPs in Canada. Additionally, provinces have opted to include additional specific excise taxes. Most provinces include another specific excise tax that uses gram as a base unit, except for British Columbia, where a specific excise tax per stick with the same rate as cigarettes is implemented, and Saskatchewan, which implements a specific excise tax per stick with a lower rate than cigarettes.

Starting January 2022, the tax structure changed in Indonesia from an ad valorem imposed on the price of HTPs to a specific tax based on the content in tobacco weight.

In the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, the rate is the same as the minimum excise on cigarettes per 1 000 pieces.

This refers to the federal tax applied on HTPs in the United States of America. A number of states also apply a state-level excise tax on those products.

In Colombia, Georgia, Israel, the Palestinian territories, Paraguay, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates, the applicable excise rate is the same as the one applied for cigarettes.

Sources: WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Policy and Administration 2021 (4). TobaccoIntelligence, November 2021 (13). Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance regulation 193/PMK.010/2021 (14). Taxes on heat not burn cigarettes in Canadian jurisdictions (15). Paraguay Law 6380 of 2019 (16). Ecuador Internal Tax Regime Law 2020 (17). Costa Rica Gazette 12 of 20 January 2022 (18). Peru Ministerial Resolution 035 of 2021 (19).

As of 2020, a total of 27 countries and 1 territory banned both ENDS and ENNDS sales (Bahrain, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Egypt, Gambia, India, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritius, Mexico, Oman, Panama, Qatar, Singapore, Suriname, Syrian Arab Republic, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Palestinian territories) and 4 countries banned ENDS sales only (Argentina, Ethiopia, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka) (5). Where they are not banned, at least 40 countries imposed an excise tax on those products. Approaches vary, with most countries implementing a specific excise on the volume of the e-liquids (Table 2). More countries tax all e-liquids (e-liquids for ENDS and ENNDS products) at the same rate. But some countries like Italy, Morocco, and Slovenia impose a lower rate on e-liquids for ENNDS products. The Philippines, on the other hand, imposes a differential rate for nicotine salts and freebase nicotine. Compared to e-liquids with freebase nicotine, those with nicotine salts deliver higher levels of nicotine to the user while masking its harshness (5). Indonesia imposes a differential rate on the e-liquids of closed systems compared to those of open systems. Finally, Denmark and Sweden apply a higher rate on e-liquids containing higher concentrations of nicotine.

TABLE 2. Types of excises applied on ENDS and ENNDS products e-liquids globally, 2022.

|

Type of excise |

Countries |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Taxing only nicotine-containing e-liquids (ENDS products) |

Taxing all e-liquids (ENDS and ENNDS products) |

|

|

Specific |

|

|

|

Base: volume per mL |

Albania, Denmark,a Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Sweden,a Uzbekistan |

Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Estonia,d Egypt, Finland, Germany,e Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Indonesia,f Italy,g Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Morocco,g North Macedonia, Philippines,h Poland, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovenia,g Ukraine |

|

Base: unit/cartridge |

Kenyab |

|

|

Ad valorem |

|

|

|

Base: retail price |

Ecuador |

Costa Rica, Yemen |

|

Base: retail price exclusive of excise and VAT |

Bahrainc |

Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates |

|

Base: cost insurance freight (CIF) value |

|

Jordan |

Notes:

In Denmark (as of 1 July 2022) and Sweden, a differential tax is applied, with a higher rate for e-liquids with a higher nicotine concentration.

In Kenya, the base of the tax on e-liquids is defined on a per unit basis, per cartridge. The amounts of the tax would apply regardless of the volume of the cartridge declared.

Tax applied to e-shisha (or e-hookah) because e-cigarettes are banned in Bahrain.

This tax has been temporarily suspended (April 2021 to December 2022).

Tax implemented as of 1 July 2022.

Moving from an ad valorem excise, Indonesia started imposing from January 2022 a specific excise on ENDS/ENNDS e-liquids with a differential rate applied for open and closed systems. The higher rate is applied on closed systems.

Italy, Morocco, and Slovenia impose differential rates for nicotine and non-nicotine containing liquids. The higher rate is applied to nicotine containing liquids.

The Philippines imposes a differential tax on freebase and salt nicotine-based e-liquids. The higher rate is applied on salt nicotine.

Sources: WHO Technical Manual on Tobacco Tax Policy and Administration 2021 (4). WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2021 (5). ECigIntelligence, October 2021 (20). ECigIntelligence, November 2021 (21). Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance regulation 193/PMK.010/2021 (14). Ecuador Internal Tax Regime Law 2020 (17). Costa Rica Gazette 12 of 20 January 2022 (18).

Some countries such as the Russian Federation also apply an excise on ENDS and ENNDS devices (20) but there are no data compiled in a systematic manner to identify all the countries that do apply such a tax.

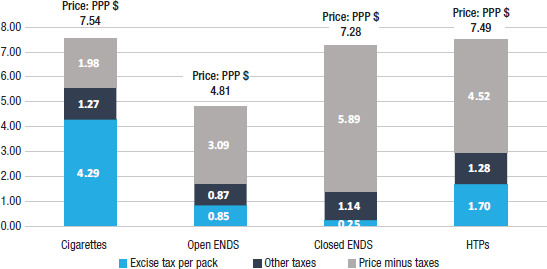

There is little information on how HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products compare with cigarettes in terms of prices and tax burden. Using information available from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021 (5) for cigarettes, HTPs, and e-liquids of open and closed ENDS systems, a compilation was made possible for 31 countries, looking at average price and tax burden by type of product, as depicted in Figure 2. While the tax burden is lower in all novel products when compared with cigarettes, average prices show different trends. Using a specific metric to compare the unit price of those products (as explained in note 2 of Figure 2), Figure 2 shows that the price of HTPs and e-liquids of closed systems is very close to the price of cigarettes, while the price of e-liquids of open systems is much lower.

FIGURE 2. Average global retail price and taxation (excise and all other taxes), 2020, most sold brand for cigarettes and HTPs and cheapest brand for ENDS e-liquids (coverage of 31 countries).

Notes:

1. Units: 20 sticks for cigarettes and HTPs; 10 mL for open systems e-liquids; and 1 mL for closed systems e-liquids.

2. Averages are simple averages.

3. Units of comparison with a pack of cigarettes (20 sticks): (i) HTPs, 20 sticks; (ii) ENDS closed system e-liquids, 1 mL (e-liquids in closed ENDS were typically sold in 2020 in a volume ranging between 0.7 and 1.5 mL, as seen in the data collected for the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. Juul Labs back in 2018–2019 had published on their website that one pod, sold at 0.7 mL volume, was equivalent to a pack of cigarettes, but this statement is no longer available on their website www.juul.com); and (iii) ENDS open system e-liquids, 10 mL. The 10 mL volume is the standard volume found in the countries of the European Union where this product is quite common; however, in terms of comparability with a pack of cigarettes, which is quite challenging to determine, it is believed that the equivalency would be found at a much lower volume, closer to 3.5 mL, as initially determined by Italy in 2015 (see case study https://vaporproductstax.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Determining-excise-rate-for-e-cigarettes-in-Italy-VPT.pdf).

4. The criteria for comparability ignore the initial cost of buying the device used for the consumption of HTPs, ENDS, or ENNDS products.

5. Prices are expressed in purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted dollars or international dollars to account for differences in the purchasing power across countries.

6. Cigarette, HTPs, and ENDS e-liquids information is based on 31 countries: 17 high-income and 14 middle-income countries with data on prices, excise and other taxes, and PPP conversion factors.

7. Countries included: Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and Uzbekistan.

8. Cheapest brand of ENDS products was reported for all countries except for Indonesia where the cheapest price and tax of an ENNDS e-liquid was reported for open systems.

Source: Compiled from data collected in the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021 (5).

REGULATORY AND MARKET SITUATION IN LATIN AMERICA

Regional market trends

Similar to global trends, the ENDS and ENNDS industry in Latin America has grown substantially over the past five years. Euromonitor estimated a retail value of US$ 94.2 million in 2020, up from US$ 21 million in 2015, in constant US$, in the major Latin American markets (10). While this is still a relatively small share (estimated at 0.5%) of the total market value for tobacco products in Latin America, the rapid growth of these products has resulted in a gain in their share of the total value pie over time versus traditional tobacco products (10).

The variability of brands selling ENDS and ENNDS products, particularly e-liquids, is wide and widening, with a growth of local e-liquid brands in countries like Colombia and Mexico (22). However, BAT holds a significant share of the total sales values of ENDS and ENNDS products in the major Latin American markets, through their brand Vype (10). Indeed, increasingly, the top three companies in terms of percentage market share—BAT, Shenzhen Joy Technology Co. Ltd, and Ritchy Group Ltd.—are deepening their market concentration (10).

The market for HTPs in Latin America is at a much younger stage, and the market size, while growing, is relatively small, with an estimated retail value of US$ 17 million in 2020 across the major markets of Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Guatemala; this represents only an estimated 0.08% of the total market for tobacco products in Latin America (10). Nevertheless, the market size has been increasing since 2017 and is forecast to grow rapidly over the next five years (10). In terms of supply, the market appears to be concentrated, with Philip Morris’s IQOS brand found in several Latin American countries, such as Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico (22).

Regulatory frameworks and tax structures applied regionally

As in other parts of the world, governments in Latin America have taken heterogeneous approaches toward regulation of HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products. In the case of HTPs, in Latin America, 3 countries (Brazil, Mexico, and Panama) have opted for a complete ban of their sale (5, 9), 4 countries regulate them as tobacco products with an explicit mention in their respective legal measures (Bolivia, Costa Rica, Paraguay, and Uruguay), while another 11 countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Peru, and Venezuela) include in their tobacco control legislation a definition of tobacco products aligned with the WHO FCTC or provisions which are broad enough to imply HTPs’ regulation, although not explicitly mentioned (9, 17, 18).

In the case of ENDS and ENNDS products, six countries in Latin America have completely banned their sale (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Panama, Uruguay, and Venezuela), seven have applied some form of regulation, but, concerningly, six (Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic,4 Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Peru) have no regulation in place, despite four of them being Parties to the WHO FCTC (5, 9, 22). Out of the seven countries that regulate them, five countries (Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Honduras, and Paraguay), treat them as tobacco or tobacco-related products, one (Chile) regulates them as a therapeutic product, and one (El Salvador) classifies them as a consumer product (5, 9, 16–18, 22–28). Of note, some countries apply these regulatory frameworks only to ENDS (e.g., the sale ban in Argentina applies only to ENDS), and in other countries ENNDS are treated the same as ENDS (e.g., Brazil and Honduras) (9). In practice, ENDS products can be almost indistinguishable from ENNDS, complicating regulatory enforcement efforts in the case that only one product is regulated.

In regard to taxation of these products, five countries (Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru) apply taxes on HTPs, Ecuador explicitly applies taxes on ENDS, and Costa Rica explicitly applies taxes on both ENDS and ENNDS. Specific excise taxes on HTPs are used in Peru (base unit is individual stick) and ad valorem excise taxes on the final retail price are implemented by Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Paraguay (16–18). Colombia has a mixed excise tax on HTPs, where the specific component is applied on the number of sticks as base unit (5). In six countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Venezuela), even though their legislation has not yet explicitly included taxation on HTPs, the broad definition of taxation applying to other tobacco products suggests that they could implement excise taxes as they do for other tobacco products (5, 9, 24, 26, 27, 29–32).

Ad valorem excise taxes are applied on ENDS products in Ecuador (17). Costa Rica applies ad valorem excise taxes on ENDS and ENNDS products (18). The remaining three countries that regulate ENDS/ENNDS products as tobacco products (Bolivia, Honduras, and Paraguay) have broad definitions of taxation applying to other tobacco products that suggest they could implement excise taxes for ENDS/ENNDS as they do for other tobacco products (9, 16, 24, 27, 28). Other countries, such as Colombia, have proposed legislation to implement excise taxes on ENDS and ENNDS products (33).

DISCUSSION

Unlike cigarette taxation, novel and emerging nicotine and tobacco products do not have a long history of taxation, and, therefore, the knowledge and evidence-base for best practices is not yet well established.

However, the experience in tobacco taxation can shed light on some effective approaches to the taxation of those products. For example, having a clearly defined and identifiable base for the excise tax will be important for both policymakers and tax administrators to implement this tax effectively. If specific excise tax is considered, the unit base needs to be clearly defined to facilitate enforcement. For example, in the case of e-liquids for ENDS and ENNDS products, a base of mL could be advisable. For HTPs, defining the unit base as the stick rather than the tobacco weight contained in each stick is much easier to implement from a tax administration perspective, as one can easily control the quantity of stick declared. If ad valorem tax is considered, setting the retail price as the base will be as effective for cigarettes as for HTPs or ENDS and ENNDS products because such base can be easily verified in the market and is less prone to undervaluation by manufacturers (4).

For ENDS products, a question arises on whether the excise tax should increase with higher nicotine concentration (this is, for example, the case for Denmark and Sweden). While nicotine itself is a toxicant (34), its impact depends essentially on how it is absorbed into the body of consumers. This can vary, in the case of tobacco, depending on the type of product consumed (e.g., smoked vs. chewed or nasal product) (35). In the case of ENDS products, this can depend, for example, on the battery power used for vaping, which can increase the nicotine delivery in e-liquids with low nicotine concentration by increasing voltage (36). This is one good reason to tax ENDS e-liquids similarly regardless of nicotine concentration. Additionally, nicotine from all sources should be taxed (e.g., nicotine extracted from the leaf or the stem of tobacco or synthetic nicotine) (4). Pushing the argument further, WHO also recommends taxing both nicotine and non-nicotine containing e-liquids similarly. This will reduce the burden on authorities to ensure e-liquids labeled as nicotine-free are indeed without nicotine (which is not always the case) (4).

With regard to the tax levels to apply on novel and emerging nicotine and tobacco products, WHO recommends taxing HTPs using the same structure and rate as cigarettes, given that they are also a tobacco product designed to look and, in a way, operate like cigarettes (4). For ENDS and ENNDS products, the discussion is less straightforward given the complexity of the product and the difficulty in comparing it with tobacco products such as cigarettes. WHO recommends taxing it highly enough that it discourages use by youth and non-tobacco users (5, 7). Figure 2 shows, for example, that open systems e-liquids remain very cheap compared with other products, and this can be a good justification for taxing ENDS and ENNDS products further.

Finally, taxing devices can also be an approach for consideration by tax authorities. They can be taxed per unit (either through a specific excise or an ad valorem) but authorities will need to clearly identify and define what those units are (4).

Conclusion

This article provides a snapshot of the market structure and regulatory approach around novel and emerging tobacco and nicotine products, both globally and in Latin America, with a focus on excise taxation.

The global demand in HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products, though small relative to conventional tobacco products, has increased rapidly in recent years, showing an appetite for these novel products. A similar trend can be observed in Latin American countries. While a few countries have decided to ban the sale of these products, others have kept them unregulated; where they are regulated, a sizable number of countries apply an excise tax on them. Approaches vary in structures and rates, but evidence from 31 countries shows that the tax burden remains quite low compared to the tax applied on cigarettes.

While evidence is not yet available on the ideal tax structures and rates to apply to HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products, experience and knowledge accumulated in tobacco taxation can provide some guidance on possible best practices. Ultimately, policymakers need to ensure that the right levels of regulations are in place such that these products are not taken up by youths and non-smokers, since they are not inherently safe and their long-term health effects remain unknown. Implementation of excise taxes effective in reducing the affordability of these products will be a key regulatory approach.

As the market of HTPs, ENDS, and ENNDS products continues to evolve and grow, and as governments continue to explore new ways to regulate them, further analysis will be needed to take stock of the successes and failures experienced. Monitoring the evolution of these products’ market sizes and structures, along with the way they are being regulated, will be useful because experience has shown that policies and markets are interdependent; they influence and shape each other over time. The current regulatory approaches summarized in this article provide a starting point as to the options available to countries, with some pointers to good practices to consider, particularly in relation to excise taxation.

Disclaimer.

Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the RPSP/PAJPH and/or the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)/World Health Organization (WHO).

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Itziar Belausteguigoitia for her thoughtful contributions to this work.

Footnotes

Author contributions.

AMP and RCS conceptualized the report. All authors collected the secondary data. AMP, SM, and GMZ analyzed the evidence and framed the findings, with input from all authors. AMP, SM, and GMZ drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised it. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest.

None declared.

This article considers the 19 Latin American Member States of the Pan American Health Organization, WHO Regional Office for the Americas: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Global aggregate values and numbers for HTP sales are likely to be underestimates, as Euromonitor covers a third of all countries for HTPs, although the largest markets are included.

Global aggregate sales values for ENDS and ENNDS products are likely to be underestimates, as Euromonitor covers about half of all countries globally for those products, although the largest markets are included.

While the Dominican Republic does not apply comprehensive regulations on HTPs and ENDS/ENNDS, it does explicitly ban their use in health facilities only (23).

REFERENCES

- 1.Guindon GE, Paraje GR, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of prices and taxes on the use of tobacco products in Latin America and the Caribbean. Am J Public Health. 2018 Dec 1;108:S492–S502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Guindon GE, Paraje GR, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of prices and taxes on the use of tobacco products in Latin America and the Caribbean. Am J Public Health. 2018 Dec 1;108:S492–S502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization . The WHO Tobacco Tax Simulation Model: WHO TaXSiM user guide. Geneva: WHO; 2018. [cited 2022 Jan 5]. Internet. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260177. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. The WHO Tobacco Tax Simulation Model: WHO TaXSiM user guide [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [cited 2022 Jan 5]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260177

- 3.World Bank Group . Confronting illicit tobacco trade: A global review of country experiences. Washington, DC: WBG; 2019. [cited 2022 Jan 5]. Internet. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/677451548260528135/pdf/133959-REPL-PUBLIC-6-2-2019-19-59-24-WBGTobaccoIllicitTradeFINALvweb.pdf. [Google Scholar]; World Bank Group. Confronting illicit tobacco trade: A global review of country experiences [Internet]. Washington, DC: WBG; 2019 [cited 2022 Jan 5]. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/677451548260528135/pdf/133959-REPL-PUBLIC-6-2-2019-19-59-24-WBGTobaccoIllicitTradeFINALvweb.pdf

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration. Geneva: WHO; 2021. [cited 2022 May 9]. Internet. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240019188. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240019188

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing new and emerging products. Geneva: WHO; 2021. [cited 2022 May 9]. Internet. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032095. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing new and emerging products [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032095

- 6.World Health Organization Decision FCTC/COP8(22) Novel and emerging tobacco products; Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, eighth session; Geneva. WHO; 2018. [cited 2022 May 9]. Internet. Available from: https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/conference-of-the-parties/eight-session-of-the-conference-of-the-parties/decisions/fctc-cop8(22)-novel-and-emerging-tobacco-products. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, eighth session. Decision FCTC/COP8(22) Novel and emerging tobacco products [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://fctc.who.int/who-fctc/governance/conference-of-the-parties/eight-session-of-the-conference-of-the-parties/decisions/fctc-cop8(22)-novel-and-emerging-tobacco-products

- 7.World Health Organization Decision FCTC/COP6(9) Electronic nicotine delivery systems and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems; Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, sixth session; Geneva. WHO; 2014. [cited 2022 May 16]. Internet. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145116. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, sixth session. Decision FCTC/COP6(9) Electronic nicotine delivery systems and electronic non-nicotine delivery systems [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2014 [cited 2022 May 16]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145116

- 8.World Health Organization . Information sheet: Measuring priority emissions in heated tobacco products, importance for regulators and significance for public health. Geneva: WHO; 2021. [cited 2022 May 9]. Internet. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350565. [Google Scholar]; World Health Organization. Information sheet: Measuring priority emissions in heated tobacco products, importance for regulators and significance for public health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2022 May 9]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350565

- 9.Crosbie E, Severini G, Beem A, Tran B, Sebrie EM. New tobacco and nicotine products in Latin America and the Caribbean: assessing the market and regulatory environment. Tob Control. 2021 Dec 16; doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056959. tobaccocontrol-2021-056959 [online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Crosbie E, Severini G, Beem A, Tran B, Sebrie EM. New tobacco and nicotine products in Latin America and the Caribbean: assessing the market and regulatory environment. Tob Control. 2021 Dec 16;tobaccocontrol-2021-056959 [online ahead of print]. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Euromonitor International Limited . Tobacco All, Latin America. London: Euromonitor; 2020. [cited 2022 May 9]. Internet. Available from: https://www.portal.euromonitor.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; Euromonitor International Limited [Internet]. London: Euromonitor; 2020 [cited 2022 May 9]. Tobacco: All, Latin America. Available from: https://www.portal.euromonitor.com/ [restricted access].

- 11.TobaccoIntelligence . The world’s 5 biggest heated tobacco markets at a glance. London: Tamarind Media; 2020. [cited 2022 May 11]. Mar, 2020. Internet. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; TobaccoIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2020 [cited 2022 May 11]. The world’s 5 biggest heated tobacco markets at a glance, March 2020. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 12.ECigIntelligence . Regulatory and market intelligence for the e-cigarette sector. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Dec 20, 2018. Internet. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; ECigIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Regulatory and market intelligence for the e-cigarette sector, 20 December 2018. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 13.TobaccoIntelligence . Heated tobacco statutory excise tax rates. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Nov 20, 2021. Internet. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; TobaccoIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Heated tobacco statutory excise tax rates, 20 November 2021. Available from:https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 14.Republic of Indonesia, Ministry of Finance . TARIF CUKAI HASIL TEMBAKAU BERUPA ROKOK ELEKTRIK DAN HASIL PENGOLAHAN TEMBAKAU LAINNYA. [Excise prices for tobacco products in the form of electric cigarettes and other tobacco processing products]. Jakarta: 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Regulation of the Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. Number 193/PMK.010/2021. [Internet] Available from: https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/download/a47c52b4-6388-4b2d-a26d-0db85d88bf2f/193~PMK.010~2021Per.pdf. [Google Scholar]; Republic of Indonesia, Ministry of Finance. Regulation of the Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. TARIF CUKAI HASIL TEMBAKAU BERUPA ROKOK ELEKTRIK DAN HASIL PENGOLAHAN TEMBAKAU LAINNYA [Excise prices for tobacco products in the form of electric cigarettes and other tobacco processing products]. Number 193/PMK.010/2021. [Internet]. Jakarta: 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from: https://jdih.kemenkeu.go.id/download/a47c52b4-6388-4b2d-a26d-0db85d88bf2f/193~PMK.010~2021Per.pdf

- 15.Physicians for a Smoke-free Canada . Taxes on heat not burn cigarettes in Canadian jurisdictions. Ottawa: PSC; 2021. Apr, [cited 2022 May 11]. Internet. Available from: https://www.smoke-free.ca/SUAP/2020/taxrates-heatnotburn.pdf. [Google Scholar]; Physicians for a Smoke-free Canada. Taxes on heat not burn cigarettes in Canadian jurisdictions [Internet]. Ottawa: PSC; 2021 April [cited 2022 May 11]. Available from: https://www.smoke-free.ca/SUAP/2020/taxrates-heatnotburn.pdf

- 16.Congreso de la Nación Paraguaya . Ley 6380. Paraguay: Congreso de la Nación Paraguaya; 2019. [Google Scholar]; Congreso de la Nación Paraguaya. Ley 6380. Paraguay: Congreso de la Nación Paraguaya; 2019.

- 17.Gobierno de la República de Ecuador . Ley de Régimen Tributario Interno. Ecuador: Gobierno de la República de Ecuador; 2020. [cited 2022 May 11]. Internet. [Google Scholar]; Gobierno de la República de Ecuador. Ley de Régimen Tributario Interno [Internet]. Ecuador: Gobierno de la República de Ecuador; 2020 [cited 2022 May 11].

- 18.Gobierno de Costa Rica . Diario Oficial La Gaceta Costa Rica No 12. Costa Rica: Imprenta Nacional Costa Rica; 2022. Jan 20, [Google Scholar]; Gobierno de Costa Rica. Diario Oficial La Gaceta Costa Rica No 12. Costa Rica: Imprenta Nacional Costa Rica; 2022 January 20.

- 19.Gobierno del Perú, Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas . Resolución Ministerial N° 035-2021-EF/15. Perú: Diario Oficial El Peruano; 2021. Jan 26, [Google Scholar]; Gobierno del Perú, Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas. Resolución Ministerial N° 035-2021-EF/15. Perú: Diario Oficial El Peruano; 2021 January 26.

- 20.ECigIntelligence . Global regulatory tracker: current regulation of e-cigs. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Oct, 2021. Internet. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; ECigIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Global regulatory tracker: current regulation of e-cigs, October 2021. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 21.ECigIntelligence . Europe regulatory tracker: current regulation of e-cigs in Europe November Heated tobacco statutory excise tax rates. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Nov, 2021. Regulatory trackers. Internet. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; ECigIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Regulatory trackers. Europe regulatory tracker: current regulation of e-cigs in Europe November Heated tobacco statutory excise tax rates, November 2021. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 22.ECigIntelligence . Market report: Latin America – current trends and future market perspectives: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Internet. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; ECigIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Market report: Latin America – current trends and future market perspectives: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru. Available from: https://ecigintelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 23.Ministerio de la Salud Pública y Asistencia Social . Resolución 000066-2021 Que actualiza la Resolución núm. 000018, d/f 28 de mayo del 2015, Que declara como Lugares Libres de Humo de Tabaco a todos los Establecimientos de Salud Públicos y Privados, incluyendo todo su perímetro. República Dominicana: 2021. [Google Scholar]; Ministerio de la Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Resolución 000066-2021 Que actualiza la Resolución núm. 000018, d/f 28 de mayo del 2015, Que declara como Lugares Libres de Humo de Tabaco a todos los Establecimientos de Salud Públicos y Privados, incluyendo todo su perímetro. República Dominicana. 2021.

- 24.Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional Bolivia . LEY N° 1280: LEY DE PREVENCIÓN Y CONTROL AL CONSUMO DE LOS PRODUCTOS DE TABACO. Bolivia: Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional; 2020. Feb 13, [Google Scholar]; Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional Bolivia. LEY N° 1280: LEY DE PREVENCIÓN Y CONTROL AL CONSUMO DE LOS PRODUCTOS DE TABACO. Bolivia: Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional; 2020 February 13.

- 25.Correa R. Ley Orgánica para la Regulación y Control de Tabaco. Ecuador: 2012. Reglamento a la ley orgánica para la regulación y control de tabaco. [Google Scholar]; Correa, R. Reglamento a la ley orgánica para la regulación y control de tabaco. Ecuador. Ley Orgánica para la Regulación y Control de Tabaco. 2012.

- 26.Ministerio de Salud de El Salvador . Reglamento de la Ley para el Control de Tabaco. El Salvador: Diario Oficial; 2015. Jun 5, [Google Scholar]; Ministerio de Salud de El Salvador. Reglamento de la Ley para el Control de Tabaco. El Salvador: Diario Oficial; 2015 June 5.

- 27.Congreso Nacional de Honduras . Ley Especial para el Control de Tabaco. Honduras: La Gaceta; 2010. [Google Scholar]; Congreso Nacional de Honduras. Ley Especial para el Control de Tabaco. Honduras: La Gaceta; 2010.

- 28.Ministerio de la Salud Pública y Bienestar Social . Resolución S.G. No 630. Paraguay: Poder Legislativo; 2019. Dec 12, [Google Scholar]; Ministerio de la Salud Pública y Bienestar Social. Resolución S.G. No 630. Paraguay: Poder Legislativo; 2019 December 12.

- 29.TobaccoIntelligence . Regulatory report: Argentina – heated tobacco and oral tobacco. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. [cited 2022 May 11]. Internet. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; TobaccoIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 [cited 2022 May 11]. Regulatory report: Argentina – heated tobacco and oral tobacco. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 30.Senado y Cámara de Diputados de la Nación Argentina . Ley 24.674. Argentina: Congreso de la Nación Argentina; 1996. [Google Scholar]; Senado y Cámara de Diputados de la Nación Argentina. Ley 24.674. Argentina: Congreso de la Nación Argentina; 1996.

- 31.TobaccoIntelligence . Regulatory report: Dominican Republic. London: Tamarind Media; 2021. Jul 13, [cited 2022 May 12]. Internet. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access] [Google Scholar]; TobaccoIntelligence [Internet]. London: Tamarind Media; 2021 July 13 [cited 2022 May 12]. Regulatory report: Dominican Republic. Available from: https://tobaccointelligence.com/ [restricted access].

- 32.Chavez H. Decreto N° 5.619 03 de octubre de 2007: Gaceta Oficial Nº 5.852 Extraordinario del 5 de octubre de 2007. Venezuela: Presidencia de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela; 2007. [Google Scholar]; Chavez, H. Decreto N° 5.619 03 de octubre de 2007: Gaceta Oficial Nº 5.852 Extraordinario del 5 de octubre de 2007. Venezuela: Presidencia de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela; 2007.

- 33.Mesa Directiva de la Comisión Tercera de la Cámara de Representantes . PONENCIA PARA PRIMER DEBATE AL PROYECTO DE LEY NÚMERO 339 de 2020 de Cámara acumulado con el PROYECTO DE LEY NÚMERO 365 de 2020. Bogotá: Cámara de Representantes; 2020. [Google Scholar]; Mesa Directiva de la Comisión Tercera de la Cámara de Representantes. PONENCIA PARA PRIMER DEBATE AL PROYECTO DE LEY NÚMERO 339 de 2020 de Cámara acumulado con el PROYECTO DE LEY NÚMERO 365 de 2020. Bogotá: Cámara de Representantes; 2020.

- 34.Mayer B. How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(1):5–7. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mayer B. How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(1):5–7. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Davis RA, Curvali M. In: Analytical Determination of Nicotine and Related Compounds and their Metabolites. Gorrod JW, Jacob P, editors. Elsevier Science; 1999. Determination of nicotine and its metabolites in biological fluids: in vivo studies; pp. 583–643. [Google Scholar]; Davis RA, Curvali M. Determination of nicotine and its metabolites in biological fluids: in vivo studies. In: Gorrod JW, Jacob P, (editors). Analytical Determination of Nicotine and Related Compounds and their Metabolites. Elsevier Science; 1999:583–643.

- 36.Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, Driskill LM, Frank SG, Meier E, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette user. Tob Control. 2017;26:e23–e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, Driskill LM, Frank SG, Meier E, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette user. Tob Control. 2017;26:e23–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]