Abstract

The correlation among the presence of a 32-bp deletion in the CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) gene, disease progression, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific immune responses was analyzed for a cohort of 79 Caucasian HIV-1-infected patients. The CCR5 genotype (CCR5/CCR5 = wild type/wild type or Δ32CCR5/CCR5 = 32-bp deletion/wild type) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells was determined by PCR, followed by sequencing of both wild-type and Δ32CCR5 gene fragments. HIV-1-specific humoral responses to gp41 and V3MN peptides were determined by enzyme immunoassays. The prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele was lower among 37 patients with rapid progression (progression to AIDS or to a CD4 cell count of <200 × 106/liter in less than 9 years; P < 0.01) compared to that for 42 patients with slow progression (no AIDS and CD4 cell count of >200 × 106/liter after at least 9 years from infection) or to that for 25 non-HIV-1-infected Swedish blood donors (P < 0.05). No differences were observed in the wild-type CCR5 sequences between the different groups of patients. For three analyzed patients, the 32-bp Δ32CCR5 gene deletions were identical. The antibody titers against gp41 and a V3MN peptide in patients with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype were not significantly different from those in pair-matched CCR5/CCR5 controls. However, in 13 analyzed patients, a stronger serum neutralizing activity was associated with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype. Thus, a CCR5/CCR5 genotype correlates with a shortened AIDS-free HIV-1 infection period and possibly with a worse neutralizing activity, without an evident influence on the antibody response to two major antigenic regions of HIV-1 envelope.

Two major coreceptors, essential for the entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into CD4-positive cells, were recently described. The fusin, or CXC receptor 4 (CXCR-4), is required for the infectivity of T-cell-tropic syncytium-inducing HIV-1 strains (3). The CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) gene (20) is essential for the infectivity of macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) non-syncytium-inducing HIV-1 strains (1, 9, 10) by binding the viral gp120 V3 loop (6). It was recently shown that a homozygous 32-bp deletion in the CCR5 (Δ32CCR5/Δ32CCR5) gene causes truncation and loss of CCR5 receptor expression on lymphoid cells, reducing the permissiveness of cells for HIV-1 infection. This mostly results in protection of the host against infection with HIV-1 (17, 23, 26). A heterozygous deletion in the same gene pair (Δ32CCR5/CCR5), although not protective against HIV-1 infection, may change the rate of HIV-1-related disease progression (8, 15, 21, 22). In fact, a higher prevalence of this genotype has been reported for HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors (LTNPs) (11, 12). Additional, lesser known factors, such as switching between different receptor usages (7), are likely to be important during HIV-1 infection and disease progression.

The prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele in the Caucasian population varies from 4 to 12% in Europe with a 15% peak in Denmark and Iceland (11, 18). The prevalence in HIV-1-infected and uninfected individuals in Sweden has not yet been reported. Furthermore, it is not known whether all Δ32CCR5 deletions are identical or whether certain sequences or mutations within the CCR5 gene correlate with disease progression.

The humoral immune response to HIV-1 has been extensively studied. It has been shown elsewhere that HIV-1-infected patients with a long-term nonprogressive course or slow disease progression display significantly different humoral responses than do those with a more rapid disease progression (4, 5, 16, 24, 28). It is not known whether the humoral HIV-1-specific responses are in any way correlated with the CCR5 genotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained from a cohort of 79 HIV-1-infected Swedish or Italian patients attending the Division of Infectious Diseases at Huddinge Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden (n = 64), or the Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases at the University of Rome “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy (n = 15), respectively. The cohort is composed of patients with a defined HIV-1 seroconversion time (n = 13) or a first positive HIV-1 test documented before 1988. Patients were divided into rapid and very rapid progressors versus slow progressors and LTNPs on the basis of their individual AIDS-free intervals (time from seroconversion or from first HIV-positive test to reach Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] stage C or 3) and their CD4+ cell counts in February 1997. The median time for progression in the whole cohort was 9.2 years. The patients considered rapid progressors were those with an AIDS-free period of less than 9 years (n = 37), including 12 very rapid progressors (AIDS-free interval shorter than 5 years). Slow progressors were all the remaining individuals (n = 42; 29 Swedish and 13 Italian patients) including 23 LTNPs, these being defined by the contemporary presence of 9 or more years of documented HIV-1 infection, a CD4+ cell count always above 500 per μl of blood, no antiretroviral therapy, and no HIV-related symptoms. Twenty-five HIV-1-seronegative Swedish blood donors were used as controls. Serum samples from 36 non-AIDS patients of the cohort (26 Swedish and 10 Italian patients; 47% in CDC stage A1, 39% in A2, and 14% in B1-B2), collected from October 1995 to February 1997, were also used for antibody measurement and neutralization testing.

Enzyme immunoassays and neutralization activity test.

The levels of antibodies to a peptide corresponding to the V3 loop of HIV-1MN (U.S.-European consensus; RKSIHIGPGRAFYTT) and to a peptide corresponding to an antigenic region of the HIV-1 gp41 (GIWGCSKLICTTAVPWNAS) were determined exactly as described previously (5). The 90% inhibitory activity (neutralizing activity) of patient sera toward clinical primary Swedish and Italian macrophage-tropic HIV-1 isolates was measured as previously described (24).

PCR.

A 183-bp fragment of the CCR5 gene was amplified by a previously described PCR (17) from PBMC genomic DNA. Wild-type 183-bp CCR5 gene fragments were distinguished from the CCR5 genes with an internal 32-bp deletion (Δ32CCR5) (17) by electrophoresis separation. For sequencing, a 340-bp fragment from the CCR5 gene was amplified by a separate PCR, with the primers 5′-CTCCTGACAATCGATAGGTAC-3′ and biotinylated 5′-CACAGCCCTGTGCCTC-TTCTT-3′. The amplification was performed in a volume of 50 μl with 10 μl of sample (lysed PBMC or extracted DNA from PBMC), 20 pmol of each primer, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 125mmoles of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate per liter, and 1 U of Taq polymerase in 1× PCR buffer. In the PCR program, a 5-min 94°C denaturation was followed by 5 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 90 s and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 62°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 90 s. Amplimers were separated on a 2.5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR products with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype were excised, purified with the QIAEX II kit (Qiagen, Heiden, Germany), and separately reamplified for sequencing.

Sequencing.

The amplified products were directly sequenced with the Cy5-labeled primer 5′-ACTTGGGTGGTGGCTGTGTTT-3′ and T7 polymerase as previously described (23). Sequence alignment and analysis were performed with the DNASIS sequence analysis software (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., San Bruno, Calif.).

Pair matching and statistical analysis.

The prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele in the different groups was compared by the Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier log rank test was used to compare cumulative AIDS-free fractions. HIV-1 antibody titers were compared in Δ32CCR5/CCR5 subjects and in CCR5/CCR5 patients by the Mann-Whitney U test. Patient pair matching was obtained for sex, age (±5 years), and CDC stage to control the effects of these confounding variables on antibody titers in 12 Δ32CCR5/CCR5 subjects and in 12 CCR5/CCR5 controls. The remaining 12 controls could not be matched with the cases (unmatched).

RESULTS

Analysis of CCR5 genotypes.

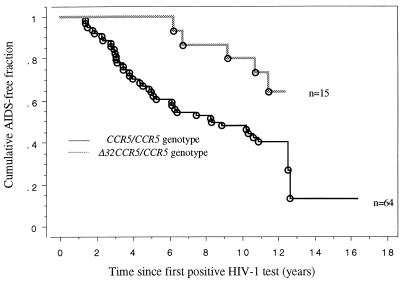

The CCR5 genotype was determined for the cohort of 79 HIV-1-infected patients and for 25 uninfected blood donors. The prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele in rapid progressors was lower than that in slow progressors (P < 0.01) and than that in blood donors (P < 0.05) (Table 1). A different classification of the patients was also tested for statistical significance, including LTNP (n = 23) and very rapid progressor (n = 12) subgroups (Table 1). However, a difference in the prevalence of the mutated allele did not further increase. The prevalence rates of the Δ32CCR5 allele in Swedish and Italian LTNPs were similar (14.3 and 16.6%, respectively; P = 0.99). A significant delayed progression rate was found in subjects with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype compared to those with CCR5/CCR5 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Presence of the 32-bp deletion in the CCR5 gene in a cohort of 79 HIV-1-infected patients from Sweden and Italy with respect to AIDS-free time and CDC stage in 1997

| Disease progression rate groupa | No. of subjects | AIDS-free interval (yr) | CDC stage in 1997 | No. of subjects (%) with a 32-bp deletion (+) in the CCR5 gene pair

|

Δ32CCR5 allele prevalenceb (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −/− | +/− | +/+ | |||||

| All slow progressors | 42 | >9 | A1-B2 | 30 (71) | 12 (29) | 0 | 14.3 |

| LTNPs alone | 23 | >9 | A1 | 16 (70) | 7 (30) | 0 | 15.2 |

| All rapid progressors | 37 | <9 | AIDS or death | 35 (95) | 2 (8) | 0 | 2.7 |

| Very rapid progressors alone | 12 | <5 | AIDS or death | 12 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uninfected blood donors | 25 | 19 (76) | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 14.0 | ||

See the text for definitions.

Fisher’s exact test for the Δ32CCR5 allele prevalence: slow versus rapid progressors, P = 0.009; slow versus very rapid progressors, P = 0.040; LTNPs versus rapid progressors, P = 0.016; LTNPs versus very rapid progressors, P = 0.045; blood donors versus slow progressors, P = 0.589; blood donors versus LTNPs, P = 0.547; blood donors versus rapid progressors, P = 0.022; blood donors versus very rapid progressors, P = 0.055.

FIG. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves describing the cumulative AIDS-free fraction in subjects with CCR5/CCR5 and Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotypes calculated at time points since seroconversion (n = 13) or first positive HIV test (n = 66). ○, AIDS (1993) events. Kaplan-Meier log rank chi-square for CCR5/CCR5 versus Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype, P = 0.038.

Sequence analysis of the amplified CCR5 gene fragments.

The sequence of the amplified CCR5 gene fragments was determined for 44 patients with a CCR5/CCR5 genotype and for 3 patients with a Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype. In the latter three cases, the wild-type and Δ32CCR5 gene fragments were excised from the gels and were separately sequenced. The 32-bp deletion was identical for all three patients. Moreover, no differences were observed in the wild-type CCR5 genes of patients with different rates of disease progression compared to the CCR5 consensus sequence (GenBank accession no. U54994) (data not shown). Thus, in the present material no specific sequence motif within the amplified wild-type CCR5 gene fragments correlates with the rate of disease progression.

Correlation between CCR5 genotype and HIV-1-specific humoral responses.

To analyze the correlation between the CCR5 genotypes and HIV-1-specific humoral responses, titers of antibodies to HIV-1 V3 and gp41 peptides were determined by enzyme immunoassays for 12 patients with a Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype and for 24 CCR5/CCR5 controls (12 of them pair matched with the patients). No significant differences in V3 and gp41 antibody titers were observed with respect to the CCR5 genotype (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antibody titers to gp41 and V3MN peptides in 12 HIV-1-infected patients with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype and 24 CCR5/CCR5 HIV-1-infected controls (12 pair matched and 12 unmatched)

| Patient | V3 antibody inverted titera

|

gp41 antibody inverted titerb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ32CCR5/ CCR5 |

CCR5/CCR5 control

|

Δ32CCR5/ CCR5 |

CCR5/CCR5 control

|

|||

| Matched | Un- matched | Matched | Un- matched | |||

| 1 | 62,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 62,500 | 12,500 |

| 2 | 12,500 | 2,500 | 62,500 | 500 | 62,500 | 12,500 |

| 3 | 62,500 | 2,500 | 62,500 | 12,500 | 12,500 | 500 |

| 4 | 500 | 62,500 | 500 | 62,500 | 2,500 | 12,500 |

| 5 | 500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 12,500 | 62,500 | 2,500 |

| 6 | 2,500 | 12,500 | 500 | 62,500 | 2,500 | 12,500 |

| 7 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 100 | 2,500 | 12,500 | 500 |

| 8 | 500 | 62,500 | 500 | 12,500 | 2,500 | 12,500 |

| 9 | 62,500 | 500 | 12,500 | 62,500 | 12,500 | 62,500 |

| 10 | 12,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 62,500 | 12,500 | 62,500 |

| 11 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 62,500 | 500 | 2,500 |

| 12 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 12,500 |

| Geometric mean antibody titer | 4,915 | 4,272 | 2,500 | 12,500 | 8,359 | 7,302 |

Mann-Whitney U test values: patients versus matched controls, P = 0.92; patients versus unmatched controls, P = 0.44; matched versus unmatched controls, P = 0.40.

Mann-Whitney U test values: patients versus matched controls, P = 0.52; patients versus unmatched controls, P = 0.39; matched versus unmatched controls, P = 0.93.

In a subgroup of eight Swedish and five Italian patients, the serum neutralizing activity toward 5 to 10 primary M-tropic HIV-1 isolates was measured. The geometric mean neutralizing titer for the 2 Δ32CCR5/CCR5 subjects was significantly higher than that for the 11 subjects with the CCR5/CCR5 genotype (1:22 versus 1:14; P = 0.025). In this group, the correlation between neutralizing activity and anti-V3 or -gp41 titer was not significant.

DISCUSSION

The recent discovery that cellular chemokine receptors are required for HIV-1 entry into CD4-positive cells has improved the understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis (6, 9, 10, 17, 23). It has been shown elsewhere that both the natural receptor ligands and their antagonists may interfere with HIV-1 infection of permissive cells in vitro (25). It has been proposed elsewhere that the presence of a heterozygous 32-bp deletion in the CCR5 gene may partially protect against progression to AIDS (8, 11, 12, 15, 19, 21, 22). We could confirm this finding in the present patient samples since the Δ32CCR5 allele was more frequent among patients with slow or no disease progression. Interestingly, we observed similar high frequencies of the Δ32CCR5 allele in LTNPs, slow progressors, and uninfected blood donors, which indicates that in our samples the wild-type CCR5/CCR5 genotype correlates with a faster disease progression and not vice versa. This result can probably be explained by both the high prevalence of LTNPs in our slow progressor group and the high prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele in our Swedish blood donor sample. Patients with the CCR5/CCR5 genotype may better support a rapid HIV-1 life cycle (14, 27) than do the ones expressing the mutant Δ32CCR5 allele (29). The mutant allele may prevent efficient HIV-1 replication by a reduction in the number of available receptors, and this effect could be amplified by secondary increases in the level of antiviral chemokine secretion (21). Therefore, patients with a CCR5/CCR5 genotype might be more prone to an early onset of immune deficiency and clinical symptoms during the first years of infection, when M-tropic HIV-1 strains are predominant. Still unclear is the influence of the CCR5 genotype in the advanced stages of HIV-1 infection. However, in a recent report, the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype was found to correlate with a reduced survival time after AIDS development (13). Other rare allelic variants of the CCR5 gene apart from the wild type and the Δ32 deletion have been described elsewhere (2). By sequence analysis of the 207 bases of the amplified CCR5 gene fragment outside the primer regions, we could not correlate a particular CCR5 sequence motif with the rate of disease progression. However, our analysis is limited to the amplified fragment and should be extended to full-length CCR5 genes.

We have for the first time correlated the CCR5 genotype with the humoral HIV-1-specific immune responses. However, in patients with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype no differences were observed in levels of antibody to HIV-1 V3 and gp41 peptides, especially when the influence of the clinical stage was excluded by pair matching the CCR5/CCR5 controls. A higher mean neutralization titer was associated with the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype in our results (P = 0.025), and this finding merits further investigation. However, only two Δ32CCR5/CCR5 patients could be tested, a number too small to control the confounding effect of clinical stage on neutralizing activity (24). Thus, this result has to be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, we could confirm that the Δ32CCR5 allele is more frequent among HIV-1-infected patients with a long-term AIDS-free infection period compared to those who rapidly progress to AIDS. No differences were seen in comparing LTNPs with the remaining slow progressors. A high prevalence of the Δ32CCR5 allele was found in our group of Swedish blood donors. Moreover, in the present study possible correlations between HIV-1-specific immune responses and the Δ32CCR5/CCR5 genotype were not clearly observed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC-CKR5: a RANTES, MIP1alpha, MIP1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari-Lari M A, Liu X M, Metzker M L, Rut A R, Gibbs R A. The extent of genetic variation in the CCR5 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:221–222. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleul C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature. 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broström C, Sönnerborg A, Sällberg M. HIV-1 infected patients with no disease progression display a maintained high avidity antibody production to autologous V3 sequences. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:897–898. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broström C, Sönnerborg A, Kim S, Sällberg M. Site directed serology of HIV-1 subtype B infection: relation between virus specific antibody levels and disease progression. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:35–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lusso P. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp 120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N R. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, Obrien S J. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng H K, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y X, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4(+) cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eugen-Olsen J, Iversen A K N, Garred P, Koppelhus U, Pedersen C, Benfield T L, Sorensen A M, Katzenstein T, Dickmeiss E, Gerstoft J, Skinhoj P, Svejgaard A, Nielsen J O, Hofmann B. Heterozygosity for a deletion in the CKR-5 gene leads to prolonged AIDS-free survival and slower CD4 T-cell decline in a cohort of HIV-seropositive individuals. AIDS. 1997;11:305–310. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galli M, Balotta C, Violin M, Colombo M C, Papagno L, Bagnarelli P the Resistant Host Perspective Study (R-HoPeS) Abstracts of the Sixth European Conference on Clinical Aspects and Treatment of HIV-Infection, 1997, Hamburg, Germany. 1997. Prevelance of CCR5 wt/D32 phenotype in long-term non progressors (LTNP), abstr. 117; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garred P, Eugen-Olsen J, Iversen A K N, Benfield T L, Svejgaard A, Hofmann B the Copenhagen AIDS Study Group. Dual effect of CCR5 Δ32 gene deletion in HIV-1-infected patients. Lancet. 1997;349:1884. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)63874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Y X, Paxton W A, Wolinsky S M, Neumann A U, Zhang L Q, He T, Kang S, Ceradini D, Jin Z Q, Yazdanbakhsh K, Kunstman K, Erickson D, Dragon E, Landau N R, Phair J, Ho D D, Koup R A. The role of a mutant CCR5 allele in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1996;2:1240–1243. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keet I P, Krol A, Klein M R, Veugelers P, de Wit J, Roos M, Koot M, Goudsmit J, Miedema F, Coutinho R A. Characteristics of long-term asymptomatic infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in men with normal and low CD4+ cell counts. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, Macdonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinson J J, Chapman N H, Rees D C, Liu Y T, Clegg J B. Global distribution of the CCRr5 gene 32-basepair deletion. Nat Genet. 1997;16:100–103. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michael N L, Chang G, Louie L G, Mascola J R, Dondero D, Birx D L, Sheppard H W. The role of viral phenotype and CCR5 gene defects in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1997;3:338–340. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raport C J, Gosling J, Schweickart V L, Gray P W, Charo I F. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel human CC chemokine receptor (CCR5) for Rantes, Mip-1-beta, and Mip-1-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17161–17166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rappaport J, Cho Y Y, Hendel H, Schwartz E J, Schachter F, Zagury J F. 32 Bp CCR5 gene deletion and resistance to fast progression in HIV-1 infected heterozygotes. Lancet. 1997;349:922–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe P M. CKR-5 deletion heterozygotes progress slower to AIDS. Lancet. 1996;348:947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C M, Saragosti S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cognaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Burtonboy G, Georges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y J, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature. 1996;382:722–772. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuelsson A, Broström C, van Dijk N, Sönnerborg A, Chiodi F. Apoptosis of CD4+ and CD19+ cells during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection—correlation with clinical progression, viral load, and loss of humoral immunity. Virology. 1997;238:180–188. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons G, Clapham P R, Picard L, Offord R E, Rosenkilde M M, Schwartz T W, Buser R, Wells T N C, Proudfoot A E I. Potent inhibition of HIV-1 infectivity in macrophages and lymphocytes by a novel CCR5 antagonist. Science. 1997;276:276–279. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theodorou I, Meyer L, Magierowska M, Katlama C, Rouzioux C. HIV-1 infection in an individual homozygous for CCR5-delta-32. Lancet. 1997;349:1219–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong M T, Warren R Q, Anderson S A, Dolan M J, Hendrix C W, Blatt S P, Melcher G P, Boswell R N, Kennedy R C. Longitudinal analysis of the humoral immune response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp160 epitopes in rapidly progressing and non-progressing HIV-1-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1523–1527. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L J, Paxton W A, Kassam N, Ruffing N, Rottman J B, Sullivan N, Choe H, Sodroski J, Newman W, Koup R A, Mackay C R. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1 in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1681–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]