Abstract

Public health and epidemiologic research have established that social connectedness promotes overall health. Yet there have been no recent reviews of findings from research examining social connectedness as a determinant of mental health. The goal of this review was to evaluate recent longitudinal research probing the effects of social connectedness on depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses in the general population. A scoping review was performed of PubMed and PsychInfo databases from January 2015 to December 2021 following PRISMA-ScR guidelines using a defined search strategy. The search yielded 66 unique studies. In research with other than pregnant women, 83% (19 of 23) studies reported that social support benefited symptoms of depression with the remaining 17% (5 of 23) reporting minimal or no evidence that lower levels of social support predict depression at follow-up. In research with pregnant women, 83% (24 of 29 studies) found that low social support increased postpartum depressive symptoms. Among 8 of 9 studies that focused on loneliness, feeling lonely at baseline was related to adverse outcomes at follow-up including higher risks of major depressive disorder, depressive symptom severity, generalized anxiety disorder, and lower levels of physical activity. In 5 of 8 reports, smaller social network size predicted depressive symptoms or disorder at follow-up. In summary, most recent relevant longitudinal studies have demonstrated that social connectedness protects adults in the general population from depressive symptoms and disorders. The results, which were largely consistent across settings, exposure measures, and populations, support efforts to improve clinical detection of high-risk patients, including adults with low social support and elevated loneliness.

Introduction

While there is no universally accepted definition of social connectedness, it generally denotes a combination of interrelated constructs spanning social support, social networks, and absence of perceived social isolation [1]. There is a broad-based agreement in the public health and epidemiologic literature that social connectedness protects and promotes mental and physical health and decreases all-cause mortality [1–3]. Researchers in fields ranging from psychology and epidemiology to sociology have been aware of these findings for several decades, but its implications have only recently begun to be appreciated more widely [4]. A Mendelian randomization study has validated the protective effects of trusted social connections on depression [5]. In a recent study of 100,000 participants in the UK Biobank [6], frequency of confiding in others and visits with family and friends emerged from over 100 modifiable risk factors as the strongest predictor of depression. This suggests that social connectedness may have protective effects or may be modified by development of a mood disorder. There is now a social connection domain in the Epic Social Determinants of Health wheel included in Electronic Health Records used in many major health organizations.

In light of these developments, we decided to conduct a scoping review of the relevant literature published between 2015 and 2020 to evaluate the extent to which social connectedness influences risk for depression and anxiety. We also sought to determine which aspects of social connectedness, namely social networks, social support) are most protective. There have been a myriad of theories explaining the association between social connectedness and mental health. These include, but not limited to Bowlby attachment theory [7,8], social support and buffering theory [9], stress-buffering theory [10], and social support resource theory [11]. According to attachment theory, depression and despair develop because of a break in attachments to people you feel close to, in the context of deaths, disputes, life changes, loneliness, or the absence of attachments [7,8]. Another relevant theory that accounts for this association is Cohen et al’s exposition of social support and buffering theory [9], an extension of Lazarus’ general stress and coping theory [12], which underscored the beneficial effects of received and perceived social support against the negative impact of stressful events without specifying the types of relationships involved. These theoretical underpinnings provided an important framework for this review that synthesizes recent literature on the various categories of social connectedness and their differential effects on depression and anxiety in specific populations. Because depression and anxiety can have adverse effects on social connectedness [13], we restricted our search to longitudinal/cohort studies from which appropriate temporal ordering that is necessary, although not sufficient, for causal inferences, can be established. We performed a scoping review of the literature published during the last five years addressing whether social connectedness is longitudinally associated with common mental health outcomes of depression and anxiety among adults.

Methods

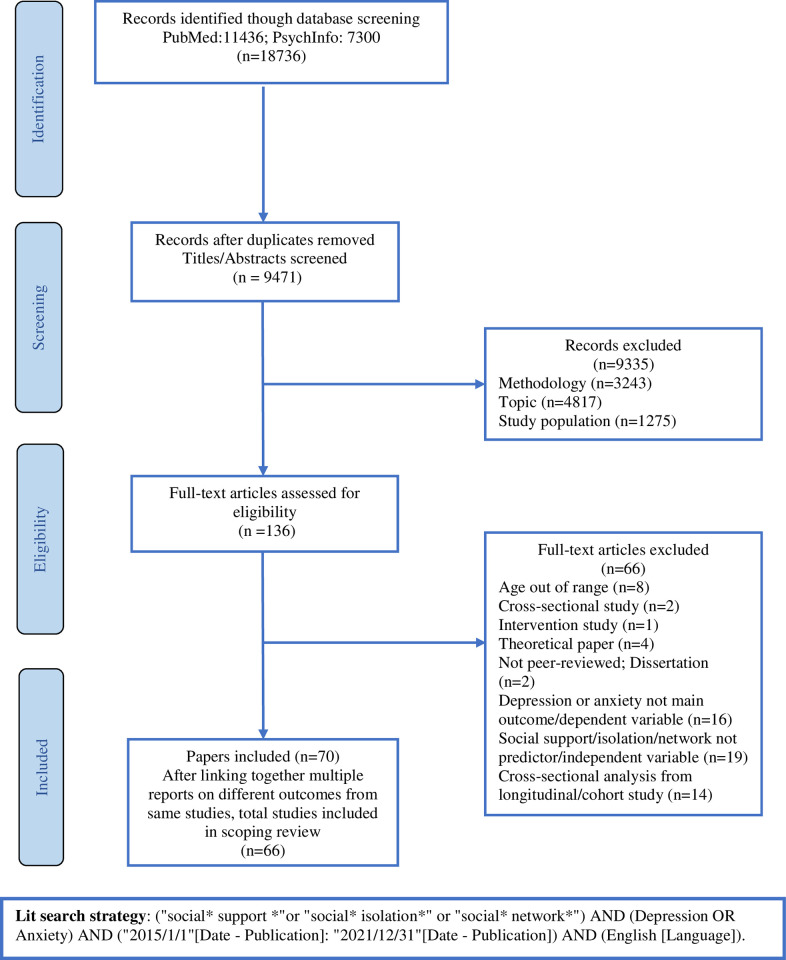

Searches of PubMed and PsychInfo databases and inspection of reference lists of relevant papers published during January 2015 and December 2021 were conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. The databases were searched using the following search strategy: ("social* support *"or "social* isolation*" or "social* network*") AND (Depression OR Anxiety) AND ("2015/1/1"[Date—Publication]: "2021/12/31"[Date—Publication]) AND (English [Language]). Fig 1 presents a flow diagram displaying the process of searching and selecting the studies.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart of the scoping review.

PRISMA diagram showing search and selection process of scoping review.

Search strategy and selection criteria

For inclusion in the review, studies were required to meet the following criteria: (a) employed longitudinal/cohort study design; (b) published in peer-reviewed journals between the years 2015 and 2021 in English; (c) assessed social support, social networks, or social isolation as one of the main predictor variables; (d) the mental health outcomes analyzed in the articles had to be either depression or anxiety; and (e) recruited participants aged 18 years or older in the study.

Studies were excluded if: (a) the article did not report original data (e.g., the article was a theoretical paper, review paper, or meta-analysis); (b) social connectedness as operationalized in the review was not measured as a predictor variable; (c) the sample included participants with pre-existing health conditions (e.g., HIV, chronic disease, cancer, stroke, etc.) except mental health conditions that are generally comorbid with depression or anxiety; and (d) the study did not focus on adults.

Data extraction

After removing irrelevant titles and duplicates, the remaining articles were reviewed with respect to the eligibility criteria. Two authors (TY and PW) scrutinized titles and abstracts, and full text articles potentially eligible for this review were obtained. Key information from included papers was initially extracted and tabulated by one author (TY). The accuracy of this information was independently verified by another co-author (PW). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. The data extracted included basic descriptive information about the sample, study type, length of follow-up, relevant predictor and outcome measures, and main findings. In cases where the same parent study data were employed in more than one publication, the papers were considered one study. Due to the wide variation in study designs and populations, we did not attempt meta-analysis, but rather provide a narrative synthesis of the main findings.

Results

The initial search yielded 18,736 articles, and 9471 articles were retained after duplicates and irrelevant articles were removed. After title and abstract screening, 136 articles were assessed for eligibility. Among studies selected for full-text review, 6 articles were deemed ineligible and excluded for various reasons: 17 did not employ longitudinal study design, 8 recruited participants aged younger than 18 years, 4 were theoretical papers, 19 did not assess social support, social networks, and/or social isolation as predictor variable, 16 did not have depression or anxiety as the main outcome variable, and 2 were not from peer-reviewed sources. The PRISMA flowchart (Fig 1) provides further detail on reasons for exclusion. Articles that used data from the same study have been combined in the table and were considered as one study. A total of 70 articles representing 66 unique studies that met inclusion criteria were included in the review.

Study characteristics

Data from 66 unique articles were categorized into three tables. Tables 1, 2 and 3 present data separately for social support, social isolation/loneliness, and social networks. Table 1 was further divided into two sections: Table 1A includes studies that investigated longitudinal effects of social support on depression or anxiety in samples other than pregnant women, and Table 1B includes studies with pregnant women.

Table 1. a. Characteristics of included studies on social support for nonpregnant samples.

b. Characteristics of included studies on social support for pregnant women.

| Reference | Sample/Setting [Country] Age (y) |

Study Type | Follow-up Times | Social Support [Measure] |

MH Outcome [Measure] |

Main Findings for Social Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Åhlin et al., 2018 [14] | n = 6679 workers [Sweden] Age = 16–64 |

Data from Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH) | 6 waves 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 |

Workplace social support [DCSQ] |

Depressive symptoms [SCL-CD6] |

Perceiving low social support is associated with subsequent higher or increasing levels of depressive symptoms over time. |

| Ahmad et al., 2021 [15] | n = 1924 refugees [Canada] Mean Age: 38.5 |

Data from Syrian Refugee Integration and Long-term Health Outcomes in Canada study (SyRIA.lth) | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 1-year later |

Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Depressive symptoms [PHQ-9] |

One of the factors significantly associated with moderate- and severe-level of depression symptoms at year 2 was lower perceived social support. |

| Aroian et al., 2017 [16] | n = 388 married Arab immigrant women [USA] Mean Age: 42 |

Longitudinal study | 3 waves roughly 18 months apart | Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

An increased rate of change over time in friend support contributed to lower depression at Time 3, but changes over time in support from husband and support from family were not significant predictors of depression at Time 3. |

| Berthelsen et al., 2015 [17] | n = 2059 nurses [Norway] Age: 21–39 |

One-year follow-up study | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 1-year follow-up |

Social support [DCSQ] | Anxiety and depression symptoms [HADS] | Structural equation modeling revealed statistically significant reverse regression paths between baseline symptoms of anxiety and depression and follow-up role clarity, role conflict, fair leadership, and social support. |

| Billedo et al., 2019 [18] | n = 98 international students from 76 host countries Age: 16–49 |

Longitudinal study | 3 waves with 3-month intervals between each wave | Perceived social support [SPS] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D-11] |

Face to face interaction with the host-country network had immediate positive impacts on international students perceived social support, which in turn, predicted lower depressive symptoms |

| Boyden et al., 2020 [19] | n = 200 parents of 158 seriously ill children [USA] Age: ≥18 |

Prospective cohort study: Decision Making in Serious Pediatric Illness study |

3 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 12 months T3: 24 months |

Perceived social support [SPS] |

Prenatal anxiety [HADS] |

Cross-sectionally, social support scores were negatively associated with anxiety scores at each time point. Longitudinally, social support scores were associated with anxiety scores, although this association weakened in adjusted modeling. |

| Canavan et al., 2021 [20] | n = 1474 participants [USA] Age: 32–87 |

National longitudinal study: Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) data set | 4 waves 1986, 1989, 1994, 2002 |

Social support [3 standardized component indices that correspond to positive support from: spouse, child/children, friend/relative] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Social support buffered the relationship between involuntary job loss and depressive symptoms among a subgroup of individuals who were more likely to be White, higher educated, and have higher social support before job loss. |

| Ciarleglio et al., 2018 [21] | n = 375 active-duty veterans deployed to Iraq at least once between 2003 and 2005 [USA] Age: ≥ 21 |

Longitudinal study: VA Cooperative Studies Program Study #566 (CSP#566) |

3 timepoints T1: prior to deployment T2: during deployment T3: after return from deployment |

Post-war-zone social support [DRRI] |

Depression and anxiety severity [DASS-21 Generalized anxiety disorder [MINI] |

Higher scores on the post-deployment social support scale were associated with lower risk of all outcomes except problem drinking. Post-deployment social support remained a strong protective factor for PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptom severity at long-term follow-up. |

| Crowe et al., 2016 [22] | n = 6521 participants in early twenties [Australia] Age: 20–24 |

Longitudinal study: Personality and Total Health (PATH) Through Life Project |

3 waves with 4-year intervals between each wave over 8-year period | Level of positive social support [2 sets of 5-item questions] |

Depressive symptoms [Goldberg Depression Scale] |

Social support, financial hardship, and a sense of personal control (mastery) all emerged as important mediators between unemployment and depression. |

| Feldman et al., 2021 [23] | n = 135 emergency medical service providers [USA] Mean Age: 35.63 |

Longitudinal study | Baseline and 3-month follow-up | Perceived quality of relationships and support [Interpersonal Support Evaluation List] |

PTSD [PCL-C] Depression [CES-D] Anxiety [BAI] |

Lower social support and poor sleep hygiene at baseline predicted increases in depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and anxiety symptoms at 3-month follow up. |

| Handley et al., 2019 [24] | n = 2639 rural residents [Australia] Age: 18–47 |

Data from Australian Rural Mental Health Study (ARMHS) |

4 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 1 year T3: 3 years T4: 5 years after baseline |

Perceived interpersonal support [Interview Schedule for Social Interaction] | Depression [PHQ-9] |

The baseline-only model found that the odds of depression were increased for those who were permanently unable to work, had low perceived availability of interpersonal support, had a greater number of recent adverse life events, and had higher levels of neuroticism. |

| Haverfield et al., 2019 [25] | n = 406 patients with co-occurring mental health and SUDs [USA] Age: NR |

Longitudinal study | 4 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 3-, T3: 9-, and T4: 15-month follow-ups |

Social support [Subscale of Basic Need Satisfaction Scale] |

Depression severity [PHQ-9] |

Less family support (i.e., more conflict) was the most consistent predictor of mental health and substance use outcomes and was associated with greater psychiatric, depression, PTSD, and drug use severity. |

| Hayslip et al., 2015 [26] | n = 86 grandparent caregivers [USA, Canada] Age: 38–90 |

Longitudinal study | 2 timepoints over 1-year time frame | Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

The interaction of overall health and social support at Time 1 predicted Time 2 depression. For those who lacked social support, overall health was negatively related to depression symptoms 1 year later. |

| Houtjes et al., 2017 [27] | n = 277 older adults [Amsterdam] Age: >55 |

Data of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) | 16 timepoints/ observations covering 13 years |

Social support [Self-reported questionnaire] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

A 2‐way interaction between depression course types and time showed significant differences in instrumental support received over time in older people with a late‐life depression. |

| Misawa et al., 2019 [28] | n = 3464 elderly people [Japan] Age: ≥ 65 |

Longitudinal panel data: Part of Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES) project | 2 waves. 2003, 2006–2007 |

Social support [Self-reported questionnaire] |

Depression [GDS-15] |

The frequency of meeting with friends and self-rated health predicted reduced odds of depression in men, while age predicted increased odds in women. |

| Noteboom et al., 2016 [29] | n = 1085 respondents from health care settings [Netherlands] Age: > 18 |

Longitudinal cohort study: Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) |

2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 2-year follow-up |

Social support [CPQ] |

Depressive disorders [CIDI] | Contrary to authors’ expectations, low perceived support, or the perceived aspects (perceived emotional support or negative aspects of support) are not associated with the development of a new episode of depression after accounting for baseline clinical characteristics |

| Van Den Brink et al., 2018 [30] | n = 1474 patients with MDD Sample 1: 1115 patients Sample 2: 359 patients [Netherlands] Age: 18–90 |

Data from two cohort studies Sample1: NESDA Sample 2: Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO) |

Social support received from partner and from closest friend or family member [CPQ] |

Presence of depression [CIDI] Depression severity [IDS-SR] |

Negative experiences with social support were the only social relational variable, which independently predicted non-remission of depression at follow-up. |

|

| Porter et al., 2017 [31] | n = 343 undergraduates and their romantic partners [USA] Age: 18–23 |

Longitudinal study | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 12-month follow-up |

Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Social anxiety [SIAS] Depression, anxiety symptoms [DASS-21] |

Social anxiety is not associated with less support as rated by observers. Socially anxious individuals received less support from their partners according to participant but not observer report. |

| Scardera et al., 2020 [32] | n = 1174 emerging adults [Canada] Age:19–20 |

Population-based cohort study: Data from Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 1 year later |

Perceived social support [SPS-10] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] Anxiety symptoms [GAD-7] |

Perceived social support was significantly associated with fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms, and suicide-related outcomes at 1-year follow-up. The magnitude of these associations appears stronger for depressive symptoms compared with anxiety symptoms. |

| Souto et al., 2021 [33] | n = 15105 civil servants [Brazil] Age:35–74 |

Multicenter cohort: Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) | 2 waves 2008–2010 2012–2014 |

Social capital- resource available on social networks [Resource Generator] |

Depressive episodes [CIS-R] |

Low social capital in the “social support” dimension was associated with the incidence of depressive episodes (RR = 1.66; 95% CI: 1.01–2.72) among men. Social support was associated with the maintenance of depressive episodes (RR = 2.66; 95% CI: 1.61–4.41) among women. |

| Stafford et al., 2019 [34] | n = 7171 people aged 50 and older living in [England] Age: >50 |

Data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | 5 waves 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010 |

Partner/spouse support [3-items questionnaire] |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D-8] |

Greater increases over time in depressive symptoms were seen in those with lower positive support at baseline. More baseline depressive symptoms predicted greater declines in positive support and greater increases in negative spousal support. |

| Steine et al., 2020 [35] | n = 506 sexual abuse survivors [Norway] Age:24–47 |

Data from the Longitudinal Investigation of Sexual Abuse (LISA) | 3 waves over 4-year period | Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Anxiety and depression symptoms [HADS] | Cross-lagged panel analyses revealed significant weak reciprocal associations between perceived social support and depression, posttraumatic stress symptoms and anxiety symptoms, but not with insomnia symptoms. |

| Whitley et al., 2016 [36] | n = 667 African American custodial grandmothers [USA] Age: 33–83 |

Prospective study | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 12-month follow-up |

Social support [FSS] |

Depression severity [BSI] |

Social support was a mediator in the association between depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life for older African American grandmothers (55+); however, this same relationship did not hold for their younger counterparts (≤55). |

| Zhou et al., 2020 [37] | n = 1137 college freshmen [China] Age: ≥ 18 |

Panel study | 3 waves with 1 month interval between each wave | Perceived Family Support [MSPSS] |

Depression severity [PHQ-9] |

Family support in Wave 1 decreased compensatory social networking sites (SNS) use for less introverted freshmen in Wave 2 and further decreased depression in Wave 3. |

| Albuja et al., 2017 [38] | n = 210 women from two clinics that provide prenatal care [Mexico] Age: 20–44 |

Longitudinal study | T1: 3rd trimester T2: 6 months postpartum |

Social Support [PDPI-R social support subscale] |

Depressive symptoms [PHQ-9] |

Lacking social support during the 3rd trimester of pregnancy was associated with greater depressive symptoms at 6 months in the postpartum, although this relationship depended on the level of endorsement of the traditional female role during pregnancy. |

| Asselmann et al., 2016 [39] | n = 306 expectant mothers sampled from community in gynecological outpatient settings [Germany] Age: 18–40 |

Prospective-longitudinal Maternal Anxiety in Relation to Infant Development (MARI) Study | T1: week 10–12 gestation T2: week 22–24 gestation T3: week 35–37 gestation T4: 10 days postpartum T5: 2 months postpartum T6: 4 months postpartum T7: 16 months postpartum |

Perceived Social Support [F-SozU K-14] |

Maternal depressive and anxiety disorders [CIDI-V] |

Perceived social support declined from prepartum to postpartum; levels of prepartum and postpartum social support were lower in women with comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders compared to those with pure depressive disorder(s), pure anxiety disorder(s), or comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders prior to pregnancy. |

| Asselmann et al., 2020 [40] | Depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms [DASS-21] |

Peripartum depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms were lower in women with higher perceived social support (b = -0.225 to -0.308). |

||||

| Cankorur et al., 2015 [41] | n = 730 women from 20 urban and rural antenatal clinics [Turkey] Age: 18–44 |

Cohort study | T1: 3rdtrimester T2: 2 months after childbirth T3: 6 months after childbirth |

Emotional, practical support [CPQ] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Worse emotional support from mother-in-law was significantly associated with postnatal depression incidence (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.99) and worse emotional support from husband with postnatal persistence (OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.96) of antenatal depression. |

| Chen et al., 2016 [42] | n = 203 South Asia immigrant mothers [Taiwan] Age: ≥ 18 |

Panel study | T1: 1 month postpartum T2: 6 months postpartum T3: 1 year postpartum |

Emotional, instrumental, informational support [Social Support Scale] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Depression and instrumental support followed downward curvilinear trajectories, while emotional and informational support followed upward curvilinear trajectories. Emotional and instrumental support negatively covaried with postpartum depression over time, but not informational support. |

| Chen et al., 2020 [43] | n = 407 immigrant and native-born women from obstetrical clinics and hospitals [Taiwan] Age: 20–44 |

Prospective study |

T1: 2nd or 3rd trimester T2: 3 months postpartum |

Emotional, instrumental, informational support [Social Support Scale] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Social support was significantly and negatively associated with postpartum depressive symptoms in both immigrant and the native-born women, and presence of depressive symptomatology during pregnancy and a lower level of social support were associated with an increased depressive symptom score at 3 months postpartum. |

| Faleschini et al., 2020 [44] | n = 1356 women from 8 obstetric offices [USA] Mean age: 32.6 |

Data from Project Viva, a prospective observational cohort study | T1: trimester visits T1: 6 months postpartum |

Perceived social support [Turner Support Scale] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Greater partner support and support from family/friends were strongly associated with lower odds of incident depression (OR 0.33, 95% CI [0.20, 0.55] and OR 0.49, 95% CI [0.30, 0.79]). |

| Gan et al., 2019 [45] | n = 3310 women from antenatal clinics [China] Age: ≥ 20 |

Prospective study; Data from Shanghai Birth Cohort | T1: early pregnancy T2: 6 weeks postpartum |

Perceived social support [ESSI] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Significant associations between low perceived social support and postpartum depressive symptoms were found (Model I odds ratio: 1.63, 95% confidence interval: 1.15, 2.30; Model II odds ratio: 1.77, 95% confidence interval: 1.24–2.52). |

| Hagaman et al., 2021 [46] | n = 780 women in rural area [Pakistan] |

Longitudinal data from the Bachpan Cohort | T1: 3 months postpartum T2: 6 months postpartum T3: 12 months postpartum |

Social support [MSPSS, MSSI] |

Major depressive disorder [SCID] |

High and sustained scores on the MSPSS through the perinatal period were associated with a decreased risk of depression at 12 months postpartum (0.35, 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.63). |

| Hare, 2020 [47] | n = 144 women at risk for peripartum depression/ euthymic [USA] Age: 19–41 |

Cohort study | T1 & T2: Twice antepartum T3 & T4: Twice postpartum |

Perceived social support [PSSQ] |

Peripartum depression [EPDS] Anxiety [HAM-A] |

Women diagnosed with PND experienced significantly worse mother–infant bonding and social support compared to HCW (p = .001, p = .002, respectively) and to those who were at‐risk for but did not develop PND (p = .02, p = .008). |

| Hetherington et al., 2018 [48] | n = 3057 women [Canada] Age: ≥ 18 |

Data from the All Our Families longitudinal pregnancy cohort | T1: 4 months postpartum T2: 1 year postpartum |

Support types: tangible, positive social interaction, and emotional/informational support. [MOS-SSS] |

Depressive or anxiety symptoms [EPDS] |

Low total social support during pregnancy was associated with increased risk of depressive symptoms (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.82) and anxiety symptoms (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.38 to 1.93) at 4 months postpartum. Low total social support at 4 months was associated with increased risk of anxiety symptoms (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.09) at 1 year. Emotional or informational support wan an important type of support for postpartum anxiety. |

| Leonard et al., 2020 [49] | n = 1316 first time mothers [USA] Age: 18–35 |

Longitudinal cohort study | 5 Time points: 1, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months postpartum | Perceived social support [MOS-SSS] |

Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Perceived social support decreased, perceived stress increased, and depressive symptoms remained constant from 1 to 18 months, then increased at 24 months. Low perceived social support predicted 6-month depressive symptoms, whereas perceived stress predicted depressive symptoms at all time points. |

| Li et al., 2017 [50] | n = 240 pregnant women from the prenatal clinic at a general hospital [China] Age: ≥ 18 |

Longitudinal study | T1: late pregnancy T2: 1 week postpartum T3: 4 weeks postpartum |

Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Antepartum depression [EPDS] |

Women who had higher Perceived Social Support Scale scores at late pregnancy had less likelihood of developing antepartum depression, and women with higher social support scores at postpartum week 4 were less likely to have postpartum depression. However, the Perceived Social Support Scale scores at late pregnancy did not predict the risk of postpartum depression. |

| Milgrom et al., 2019 [51] | n = 54 women who met DSM-IV criteria of MDD or minor depression [Australia] Age: ≥ 18 |

Longitudinal follow-up of a previous RCT for antenatal depression | T1: baseline T2: 9 weeks post-randomization T3: 6 months T4: 9 months T5: 24 months post-birth |

Perceived social support [SPS] |

Depression [BDI-II] Anxiety [BAI] |

Two aspects of social support, reassurance of worth and reliable alliance, were strongly related to perinatal depression and anxiety, particularly when predicting symptoms in late pregnancy. However, the effect of postnatal depression on child development at 9- and 24-months post-birth was not mediated by social support. |

| Morikawa et al., 2015 [52] | n = 877 women enrolled in a prepartum program during pregnancy [Japan] Age: ≥ 20 |

Cohort study |

T1: before 25th week of gestation T2: 1 month after childbirth |

Social support [SSQ] | Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Having a larger number of people available to provide social support during pregnancy has a greater protective effect on pregnant mothers with than without depression. |

| Nakamura et al., 2020 [53] | n = 12386 couples [France] Age: ≥ 18 |

Data from the French representative ELFE (Etude Longitudinale Française depuis l’Enfance) cohort study |

T1: at birth T2: 2 months post-partum T3: 1year postpartum T4: 2 years post-partum |

Informal and formal support [face-to-face and phone interviews] |

Parental postnatal depression [EPDS] |

Insufficient partner support as well as frequent quarrels during pregnancy predicted the odds of both parents being depressed. This association was higher for women with psychological difficulties during pregnancy than those without. An inverse association was also observed between psychosocial risk assessment attendance (informal support) and joint parental PPD, especially in couples in which the mother had psychological difficulties during pregnancy. |

| Ohara et al., 2017 [54] | n = 494 pregnant women attending perinatal classes [Japan] Age: ≥ 20 |

Prospective cohort study | T1: early pregnancy before week 25 T2: 1 month after delivery |

Number of persons and satisfaction with social support [SSQ] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Satisfaction with the social support received during pregnancy did not directly predict depression in the postpartum period at a statistically significant level. However, poorer satisfaction with the social support received during pregnancy was a cause of depression in the postpartum period due to increased depression during pregnancy. |

| Ohara et al., 2018 [55] | n = 855 pregnant women attending perinatal classes [Japan] Age: ≥ 20 |

Cohort study | T1: early pregnancy before week 25 T2: 1 month after delivery |

Number of persons and satisfaction with social support [SSQ] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Bonding failure in the postpartum period was significantly influenced by mothers’ own perceived rearing as well as social support during pregnancy. In addition, depression in the postpartum period was strongly influenced by social support during pregnancy. |

| Qu et al., 2021 [56] | n = 66 pregnant women with a history of recurrent miscarriage [China] Mean Age:31.9 |

Prospective longitudinal study | 6–12, 20–24 and 32–36 gestational weeks | Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Anxiety [SAS] Depression [EPDS] |

Anxiety and depression were prevalent in pregnant women with a history of recurrent miscarriage, especially in early pregnancy with the lowest level of social support. The correlations among anxiety and social support, and depression and social support at each time point were significant (p < 0.05). |

| Racine et al., 2019 [57] | n = 3388 mothers from community, laboratory, and health care clinic offices [Canada] Age: ≥ 18 |

Large, population-based cohort All Our Babies/Families (AOB/AOF) |

T1: < 25 weeks gestation T2: 34–36 weeks gestation T3: 4 months postpartum T4: 12 months postpartum |

Perceived social support: [3 questions] |

Prenatal and postpartum anxiety [STAI] |

Women who experience heightened stress and anxiety in the perinatal period relative to their own average levels are at risk of higher anxiety and stress at subsequent time points; within-person increases in partner and friend support are salient predictors of subsequent decreases in both stress and anxiety; increases in stress and anxiety in the perinatal period are at risk of experiencing decreases in friend and family support. |

| Racine et al., 2020 [58] | n = 1994 women from health care and laboratory offices [Canada] Age: ≥ 18 |

Large, population-based cohort All Our Babies/Families (AOB/AOF) |

T1: < 25 weeks gestation T2: 4 months postpartum T2: infant age of 36 months |

Maternal social support [MOS-SSS] |

Maternal depression [EPDS] |

Although maternal social support was a significant predictor of maternal depression across the perinatal period, social support did not moderate the association between ACEs and maternal depression. |

| Razurel et al., 2015 [59] | n = 235 primiparous mothers [Switzerland] Age:21–43 |

Longitudinal study | T1: During the last month of pregnancy and T2: 6 weeks after birth | Satisfaction with social support [20-items scale constructed in the area of perinatal care] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] Anxiety [STAI] |

Satisfaction with emotional support in T1 was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms in T1 and T2, which suggested that this type of support was important both in the short and the long term. |

| Razurel et al., 2017 [60] | T1: gestational weeks 37–41 T2: 2 days post-delivery T3: 6 weeks postpartum |

The more the women were provided with support from their partners, the less depressive symptoms and elevated levels of anxiety they reported, even under stressful conditions, while the satisfaction of support from their mothers boosted their sense of competency. Satisfaction with emotional support from professionals tempered the stress during the post-partum period (ΔR2 = 0.032; p < .05). | ||||

| Schwab-Reese et al., 2017 [61] | n = 195 women from a large hospital [USA] Age: ≥ 18 |

Longitudinal study | T1: following birth T2: 3 months after birth T3: 6 months after birth |

Perceived social support [MOS-SSS] |

Depressive and anxiety symptoms [DASS–21] |

Current perceptions of social support were associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms at three-months postpartum, but social support was not protective against depressive or anxiety symptoms at six-months postpartum. |

| Senturk et al., 2017 [62] | n = 730 women recruited in their third trimester [Turkey] Age: 18–44 |

Cohort study | T1: 3rd trimester T2: 0.8–7.4 months after childbirth T3: 10.8–16.6 months T4: 18.1–23.5 months |

Quality of relationships and social support [CPQ] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Self-rated emotional and practical support from all three relationships worsened over time in the cohort overall. Emotional support from the husband, and emotional and practical support from the mother-in-law declined more strongly in women with depressive symptoms at baseline |

| Tani et al., 2017 [63] | n = 179 nulliparous pregnant women [Italy] Age: 18–42 |

Longitudinal study | T1: 31–32 week of pregnancy T2: 1st day after childbirth T3: 1 month after birth |

Perceived social support [MSSS] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Post-partum depression was influenced negatively by maternal perceived social support and positively by negative clinical birth indices. In addition to these direct effects, analyses revealed a significant effect of maternal perceived social support on post-partum depression, mediated by the clinical indices considered. |

| Tsai et al., 2016 [64] | n = 1238 pregnant in economically deprived settlements [South Africa] Age: ≥ 18 |

Population-based longitudinal study | T1: 6 days after birth T2: 6 months post-partum T3: 18 months post-partum T4: 36-month follow-up |

Emotional and instrumental support (10 questions about trust and support derived from SOS) |

Depression symptom severity [EPDS] |

Social support was found to be an effect modifier of the relationship between food insufficiency and depression symptom severity, consistent with the “buffering” hypothesis. Instrumental support provided buffering against the adverse impacts of food insufficiency while emotional support did not. |

| Yoruk et al., 2020 [65] | n = 317 pregnant women at 38 weeks of gestation [Turkey] Age: 23–34 |

Longitudinal study | T1: 4th week postpartum T2: 6th week postpartum |

Perceived social support [MSPSS] |

Postpartum depression [EPDS] |

Despite the low level of perceived social support in the group at risk for PPD, this difference was not significant. |

| Yu et al., 2021 [66] | n = 512 first-time mothers [USA] Mean Age: 21.3 |

Data from the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect | T1: 6-month postpartum T2: 12-month postpartum |

Social support [SSI] |

Depressive symptoms [BDI-II] |

Social support was not found to have a direct or indirect effect on postpartum depression/ |

| Zheng et al., 2018 [67] | n = 420 Chinese primiparous women from obstetric wards at hospitals [China] Age: ≥ 18 |

Longitudinal study | T1: 6 weeks postnatally T2: 12 weeks postnatally |

Emotional, material, informational, and evaluation of support [PSSS] |

Postnatal depression symptoms [EPDS] | Postnatal depression symptoms and social support are the important influencing factors of maternal self-efficacy. The mean social support scores and scores of emotional support, informational support and evaluation of support had statistically significant increases over time. |

| Zhong et al., 2018 [68] | n = 3336 women [Peru] Age: 18–49 |

Pregnancy Outcomes, Maternal and Infant Cohort Study |

T1: <16 weeks gestation T2: 26–28 weeks gestation |

Satisfaction with social support and number of support providers [SSQ-6] |

Depressive symptoms [EPDS] |

Low number of support providers at both time points was associated with increased risk of depression (odds ratio = 1.62, 95% confidence interval: 1.12, 2.34). Depression risk was not significantly higher for women who reported high social support at one of the 2 time points. |

Checklist: BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; PCL-L = Civilian PTSD Checklist; BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CIS-R = Clinical Interview Schedule–Revised; DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; DCSQ = Demand-Control-Support-Questionnaire; DRRI = Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory; FSS = Family Support Scale; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IDS-SR = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report version; MINI: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; SCL-CD6 = Symptom Checklist Core Depression Scale; SIAS = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; SPS = Social Provisions Scale.

Checklist: BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview for Women; CPQ = Close Persons Questionnaire DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ESSI = ENRICHD Social Support Instrument; F-SozU K-14 = Brief form of the Perceived Social Support Questionnaire; HAM-A = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MOS-SSS = Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey; MSPSS = Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; MSSI = Maternal Social Support Index; MSSS = Maternal Social Support Scale; PDPI-R = Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; PSSQ = Postpartum Social Support Questionnaire; PSSS = Postpartum Social Support Scale; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; SAS = Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SOS = Significant Others Scale; SPS = Social Provisions Scale; SSI = Social Support Interview; SSQ = Social Support Questionnaire; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Scale.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies on social isolation.

| Reference | Sample/Setting [Country] |

Study Type | Follow-up Times | Social Isolation [Measure] |

MH Outcome [Measure] | Main Findings for Social Isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domènech-Abella et al., 2019 [69] | n = 5066 adults [Ireland] age ≥50 |

Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) | 2 waves of TILDA Second wave: 2012–13 Third wave: 2014–15 |

UCLA Loneliness Scale | Major depressive disorder (MDD) or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) [CIDI] |

The longitudinal association between experiencing loneliness and higher likelihood of suffering from GAD two years later is bidirectional, whereas the association between social isolation and higher likelihood of subsequent MDD or GAD as well as those between loneliness and subsequent MDD or deterioration of social integration are unidirectional. |

| Domènech-Abella et al., 2021 [70] | n = 895 older adults [Netherlands] Age: ≥75 |

Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) | 4 waves over 10 years | De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Loneliness was positively associated with depressive symptomatology, but not vice versa. |

| Evans et al., 2019 [71] | n = 2135 elderly residents [Wales] Age: ≥65 |

Data from the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study–Wales (CFAS-Wales) | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 2-year follow-up |

LSNS-6 |

Depression and anxiety [AGECAT] |

Older people with depression or anxiety perceived themselves as more isolated than those without depression or anxiety, despite having an equivalent level of social contact with friends and family. In people with depression or anxiety, social isolation was associated with poor cognitive function at baseline, but not with cognitive change at 2-year follow-up. |

| Förster et al., 2021 [72] | n = 679 elderly individuals [Germany] Age: 80+ |

Longitudinal study AgeCoDe and its follow-up study AgeQualiDe | Data from follow-up 5 to follow-up 9 (2011–2016) |

LSNS-6 |

Depression [GDS-15] |

“Widowed oldest old”, who are also at risk of social isolation, reported significantly more depressive symptoms in comparison to those without risk. |

| Herbolsheimer et al., 2018 [73] | n = 334 community-dwelling older adults [Germany] Age: 65–84 |

Longitudinal study | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 3 years later |

LSNS-6 | Depressive symptoms [HADS] |

Being socially isolated was associated with lower levels of out-of-home physical activity, and this predicted more depressive symptoms after 3 years. However, no direct relationship was observed between social isolation from friends and neighbors at the baseline and depressive symptoms 3 years later. |

| Holvast et al., 2015 [74] | n = 285 older adults [Netherlands] Age: ≥ 60 |

Multi-site prospective cohort study from the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO) | 2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 2-year follow-up |

De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale | Depression [CIDI] Depression severity [IDS-SR] |

Loneliness, subjective appraisal of social isolation, was a significant positive determinant of depressive symptom severity during follow-up. This association was independent of social network size and persisted after controlling for other potential confounders. |

| Lee et al., 2021 [75] | n = 4211 adults [UK] Age: ≥ 50 |

Data from English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | 7 waves collected once every 2 years between 2004 and 2017 | R-UCLA | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Loneliness, irrespective of other social experiences, was associated with a heightened risk of depression, and this risk persisted for up to 12 years after the loneliness was reported. |

| Martín-María et al., 2021 [76] | n = 1190 older Spanish adults Age:50+ [European countries] |

Longitudinal study | Interviewed on 3 evaluations over a 7-year period | UCLA Loneliness Scale | Depression [CIDI] |

Participants experiencing chronic loneliness were at a higher risk of presenting major depression (OR = 6.11; 95% CI = 2.62, 14.22) relative to those presenting transient loneliness (OR = 2.22; 95% CI = 1.19, 4.14). |

| Noguchi et al., 2021 [77] | n = 3331 respondents [England and Japan] Age: ≥ 65 |

Data from English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES) |

Followed up regarding depression onset for 2 years (2010/2011–2012/2013) for ELSA and 2.5 years (2010/2011–2013) for JAGES |

Modified version of SSI |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D. GDS-15] |

Social isolation was significantly associated with depression onset in both England and Japan, despite variations in cultural background. |

Checklist: AGECAT = Automated Geriatric Examination; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IDS-SR = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report version; LSNS = Lubben Social Network Scale; R-UCLA = Revision of the University of California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale; SSI = Social Isolation Index.

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies on social network.

| Reference | Sample/Setting [Country] |

Study Type | Follow-up Times | Social Network [Measure] | MH Outcome [Measure] | Main Findings for Social Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek et al., 2021 [78] | n = 291 married couples [South Korea] Age: ≥60 |

Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (KSHAP) | 5 waves: 2011, 2012, 2014–15, 2015–16, 2018–19 | Fours questions in total about supportive relations and negative relations | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

The association between husbands’ and wives’ depressive symptoms was stronger for couples that reported a low level of supportive marital relations, but only for the wife and those that reported a high level of negative marital relations for both the husband and wife. |

| Chang et al., 2016 [79] | n = 21728 elderly women [USA] Age: ≥65 |

Prospective cohort study: Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) | 5 timepoints, Baseline and 4 biennial follow-up questionnaire cycles over 10-year period |

Berkman-Syme Social Network Index | Depression [MHI-5 subscale of the SF-36, CESD-10, GDS-15] |

Social factors (lower social network; lower subjective social status; high caregiving burden to disabled/ill relatives) were associated with higher incident late-life depression risk in age-adjusted models. |

| Domènech-Abella et al., 2021 [70] | n = 5066 older adults [Ireland] Age: ≥75 |

Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) | 4 waves over 10 years | Names of persons with whom they had regular contacts in the past year | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Decreasing social network size (Coef. = -0.02; p < 0.05), predicted higher levels of loneliness, which predicted an increase in depressive symptoms (Coef. = 0.17; p < 0.05) and further reduction of social network (Coef. = -0.20; p < 0.05). |

| Domènech-Abella et al., 2019 [69] | n = 5066 adults [Ireland] Age: ≥50 |

Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) | 2 waves of TILDA Second wave: 2012–13 Third wave: 2014–15 |

Berkman-Syme Social Network Index |

MDD or GAD [CIDI] |

Both objective social isolation (size of social network) and loneliness factors have been found to be robust risk factors for depression and anxiety independently, which acts as a warning not to underestimate the subjective aspects of social isolation. |

| Förster et al., 2018 [80] | n = 783 elderly people [Germany] Age: ≥ 75 |

Population-based cohort study: Leipzig Longitudinal Study of the Aged (LEILA) | 3 timepoints T1: baseline T2: follow-up1 T3: follow-up2 |

PANT | Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Persons with a restricted social network were more likely to develop depression, and risk of depression was particularly high for elderly with social loss experiences. |

| Noteboom et al., 2016 [29] | n = 1085 respondents from health care settings [Netherlands] Age:> 18 |

Longitudinal cohort study: Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) |

2 timepoints T1: baseline T2: 2-year follow-up |

Questions on how many relatives, friends or others over the age of 18 years they had regular and important contact | Depressive disorders [CIDI] | Structural (network size and partner status) did not predict depression at follow up. Pariticipants with a lifetime history of depression reported a smaller social network. |

| Van Den Brink et al., 2018 [30] | n = 1474 patients with a major depressive disorder [Netherlands] Age:18–90 |

Data from 2 cohort studies NESDA and Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO) | Questions on social network characteristics | Presence of depression [CIDI] Depression severity [IDS-SR] |

Social network characteristics, such as having a partner and number of persons in one’s household, are related to depression course. |

|

| Reynolds et al., 2020 [81] | n = 3005 elderly people [USA] Age:57–85 |

Panel data from National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) | 3 waves 2005, 2010, and 2015 with 5-year intervals between each wave |

Questions on community-layer, interpersonal-layer, and partner-layer connection |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D] |

Results demonstrate multiple links between social connection and depression, and that the evolution of social networks in older adults is complex, with distinct mechanisms leading to positive and negative outcomes. Specifically, community involvement showed consistent benefits in reducing depression. |

| Santini et al., 2020 [82] | Social Disconnectedness Scale |

Depressive symptoms [CES-D-ML] Anxiety [HADS-A] |

Perceived isolation was positively associated with depression symptoms at T2 and T3 (β = 0·12; p<0·0001). | |||

| Santini et al., 2021 [83] | n = 38300 adults [13 European countries] Age: ≥ 50 |

Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | 2 consecutive waves (2011, 2013) of the SHARE survey | The total number of close relations in the social network | Depressive symptoms [EURO-D Scale] |

Social participation among people with relatively few close social ties was negatively associated with depression symptoms but did not seem to benefit to those with relatively many close social ties. |

Checklist: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale; CES-D-ML = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Minus Loneliness Scale; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IDS-SR = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report version; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; MHI-5 = Mental Health Index-5.

Social support

A little over half of the recent articles on the effect of social support on depression addressed the issues of depression in pregnant women, while the rest addressed the association of social support with anxiety or depression, in a variety of populations, other than pregnant women. We begin our review with nonpregnant populations because the results are of broader general relevance.

Study Samples other than pregnant women. Table 1A lists the 24 articles that reported quantitatively on the longitudinal effects of social support on depression or anxiety in samples other than pregnant women, but two papers reported on one study, resulting in a total of 23 studies. The sample size of the included studies ranged between 86 and 15,105 participants. Majority of the studies were conducted in North America (11 studies), and the remaining were from Europe (7 studies), Asia (2 studies), and Australia (2 studies). One study was international in scope and sampled students from 76 host countries.

Assessing depression/Anxiety and social support. The twenty-three included studies used a threshold score on a depression rating scale to measure depressive symptoms, and the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale was the most frequently utilized scale, being used in eight studies. Other measures with established psychometric properties included in this Table were as follows: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9, Geriatric Depression Scale, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Symptom Checklist Core Depression Scale, and Brief Symptom Inventory. In order to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, three studies [17,19,35] used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and two [21,31] used Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. Furthermore, some studies employed [29,30,33] structured diagnostic interviews for common mental disorders. The social support measures in these studies varied considerably, with five studies [15,16,26,31,35,37] using the original or the adapted version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Two studies [14,17] employed Demand-Control-Support-Questionnaire (DCSQ) to assess workplace social support, and three studies [18,19,32] used Social Provision Scale (SPS). A scale in the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) was employed in one veteran study to assess the extent to which they perceive assistance and encouragement in the war zone from fellow unit members [21]. Five studies [20,22,27,28,34] used questionnaires that were developed by the authors. The Interview Schedule for Social Interaction—availability of Attachment Scale was used to measure the perceived availability of interpersonal support [24]. Whitley et al [36] used the Family Support Scale (FSS), and Haverfield et al. [25] used a subscale of the Basic Need Satisfaction Scale to assess general social support (Table 1A).

Effects on depression/Anxiety. Social support has been shown benefit in abating symptoms of depression over time in 19/23 or 82.6% of the studies (Table 1A). Analyses of mental health conditions in a sample of nationally dispersed war-zone veterans for over seven years indicated that higher levels of social support post-deployment were associated with decreased risk of depression and anxiety disorders, as well as less severe symptoms [21]. Moreover, reduced levels of perceived support at the workplace were associated with increased levels of depression symptoms [14], which aligns with previous research that showed a direct influence of social support on the well-being of medical staff workers in the subsequent study waves [17]. Apart from these direct effects, social support has also been shown to have "buffering" effects on the association between involuntary job loss and depressive symptoms among a subgroup of persons who are more likely to be White, educated, and have high levels of social support before becoming unemployed [20]. In a longitudinal study among emergency medical care providers conducted in the United States by Feldman and colleagues [23], social support at baseline was identified as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD), depression, and anxiety symptoms at 3-month follow-up.

A five-year study of rural community residents also found that low perceived interpersonal support was associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including depression [24]. The impact of social capital in the social support dimension on psychiatric health may be differentiated by gender [33]. In a multicenter cohort of civil servants, Souto et al. [33] reported an association between social support and the maintenance of depressive episodes among women (RR = 2.66; 95% CI: 1.61–4.41). However, among men, the authors found an inverse relationship between social capital in the “social support” dimension and incidence of depressive episodes (RR = 1.66; 95% CI: 1.01–2.72) [33]. Billedo et al. [18] found short-term reciprocal associations between social support and depressive symptoms in sojourning students. They further stated that face-to-face interaction with the host-country network had immediate positive effects on perceived social support, which subsequently predicted lower depressive symptoms [18]. Even in samples of emerging adults, higher levels of perceived social support were protective against depressive and anxiety symptoms [22,32]. Boyden and colleagues followed a sample of parents of critically ill children over two years and found that greater perceived social support was associated with lower anxiety levels across assessments [19]. Higher baseline social support remained negatively associated with lower parental anxiety scores at 12 months (B = -0.12, p = 0.03; 95% CI = -.23 to -.01) and 24 months (B = -0.11, p = 0.04; 95% CI = -0.21 to -0.01). This inverse association had dissipated by 24 months in their adjusted modeling [19]. Their findings concur with other aforementioned studies that demonstrated a benefit of having supportive relationships.

Interestingly, in terms of the source of social support, the role of family support remains unclear. One study of married Arab immigrant women in the U.S. did not find family support to be protective against depression. Instead, support from friends was found predictive of fewer depressive symptoms at follow-up [16]. However, the results of this study contrast with those of Zhou et al., [37] who showed that more perceived family support decreased usage of social networking sites, which was followed by decreased depressive symptoms among Chinese college students. Similarly, Haverfield et al. [25], analyzed data from patients with co-occurring disorders at treatment intake and across follow-ups in the United States and found that deficits in family support were the most consistent predictor of greater depression and substance use severity [25]. Consistent with previous studies on social support drawn from family and their positive impacts, two studies [26,36] specifically focused on custodial grandparents in the U.S. showed that while elevated caregiving stress may negatively affect grandparent caregivers’ mental and overall health over time, greater social support from family networks may reduce depression accompanying caregiving. According to Whitley et al., [36] social support has a mediating effect on the relationship between depression and mental health quality of life in older (55+) African American custodial grandmothers, but not in their younger (≤55) counterparts.

Although depression peaks in young adulthood, it either can persist or emerge later in life, as evidenced by the three studies focusing exclusively on the role of social support in samples of adults aged 55 and older. Misawa and Kondo (2019), in a study of 3464 Japanese older people, reported that social support was unrelated to changes in depressive symptoms but added that social factors of having hobbies and meeting frequently with friends were associated with improved late-life depression. This link between social interaction and social support was only observed to be protective for men [28]. Conversely, another study spanning eight years of follow-up of older adults in England found a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and spousal support [34]. The authors found an average decrease in positive support (or an increase in negative support) over time in age- and gender-adjusted models, which later predicted increasing depressive symptom trajectory [34]. Another study on older people with depression revealed that a chronic course of depression might decrease received social support over time [27]. Moreover, their findings suggest that pre-existing depression in concert with less social support may predispose older persons, especially men and single people, to more depression over time [27].

A few studies (3/19 = 16%) found minimal or no evidence that lower levels of social support predict depression at follow-up. For example, in a naturalistic cohort study of Noteboom et al. [29], people with a prior history of depression reported a smaller network size and less emotional support at baseline However, these structural (network size or having a partner) and the perceived aspects of social support had no predictive value in the longitudinal data. Similarly, only negative experiences with social support proved to be a risk factor for non-remission, independent of other social-relational variables in depressed persons [30]. Steine et al. [35] found statistically significant weak reciprocal associations between perceived social support and depression and anxiety symptoms over time among adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Although Porter and Chambless reported a link between higher odds of relationship dissolution and social anxiety, they observed no differences between participants with high versus low social anxiety with regard to the amount of social support provided by their partners [31].

Social support for women during and post pregnancy. Table 1B presents results from thirty-one articles examining associations between social support and depression during pregnancy or postpartum, uniquely vulnerable periods for women during which they may experience a range of psychosocial stressors. Two pairs of papers provided findings based on identical samples and were reported in a combined table entry, resulting in twenty-nine studies. Studies were predominantly conducted in Asia (45%) and North America (32%), with the remaining studies from Europe (14%), South America (3%), Africa (3%), and Australia (3%). In terms of individual countries, six studies were conducted in the United States, followed by four studies in China, and three studies each in Canada, Japan, and Turkey. Sample sizes varied from 54 participants in a follow-up of a previous randomized trial [51] to 12,386 couples in a study with findings on both maternal and paternal depression [53]. Most of the included studies [38–41,43,44,47,50,51,58–60,62,63,68] in the mid or late pregnancy, four [45,54–56] started in early pregnancy, and ten studies [42,46,48,49,53,61,64,65,67,70] started after birth. Women were on average aged between 18 and 40 years old. The most commonly used measures of social support and depression were, respectively, the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Table 1B).

The majority of the studies (24/29 = 83%) found low social support increased postpartum depressive symptoms. Women with higher perceived social support exhibited lower depression (b = -0.308, SE = 0.036, p < .001) and anxiety (b = -0.225, SE = 0.039, p < .001) symptom severity across the peripartum period [40]. Similar results were obtained by other studies [45,48,51,58,68] conducted to investigate the trajectory of the association between depression and perceived social support. A study in Taiwan comprising 407 immigrant and native-born women showed that a presence of depression symptoms during pregnancy (β = 0.246; p<0.001) and deficient social support (β = -0.233; p<0.001) positively covaried with depressive symptoms at 3- months postpartum [43]. The significant protective factor of social support against postpartum depression was also highlighted in another study through a mediating effect of good clinical delivery.46 Hagaman et al. [46] employed multiple time-varying measures of social support to evaluate the causal effect of longitudinal patterns on perinatal depression outcomes at six and twelve months postpartum. The authors found that women who had sustained high scores on the MSPSS had reduced prevalence of depression at one-year post-partum [46]. Moreover, insufficient social support and frequent quarrels during pregnancy were associated with significant increase in joint postpartum depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers [53]. Tani et al. demonstrated a protective role of maternal and paternal relationships on postpartum depression in nulliparous women [63].

Asselmann and colleagues [39] found a bidirectional relationship between peripartum social support and psychopathology. They concluded that low social support increased the risk for anxiety and depressive disorders, and these disorders before pregnancy, in turn, fostered dysfunctional relationships and lowered social support across the peripartum period [39]. Women with comorbid anxiety and depression were at higher risk for lacking social support during this timeframe [39]. Social support appeared to be a predictor of depression from mid-pregnancy to six months postpartum, particularly in late pregnancy. Nonetheless, the predictive effect of social support on anxiety was only observed in late pregnancy [68]. Latina women who had lower social support during the third trimester of pregnancy were reported to be at greater risk of depressive symptoms at six months in the postpartum, which was consistent with a study on primiparous mothers [49]. Specifically, we found that women with lower social support and higher self-reported adherence to the Traditional Female Role were at the highest risk of experiencing postpartum depressive symptoms [38]. A study conducted in China found that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent in pregnant women who have experienced recurrent miscarriages, particularly in the early weeks of pregnancy when social support is at its lowest level [56]. These findings converge with those from the past studies that identified social support as an important buffer against anxiety and depression throughout the pregnancy [56].

Data from Canada reported inverse associations between 1) social support during pregnancy and anxiety and depression postnatally (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.82) and 2) social support at four months postpartum and one year postpartum (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.09) [48]. In contrast to these studies, Schwab-Reese et al. stated that social support was not protective against depressive or anxiety symptoms at six months postpartum as it was at three months postpartum [61].

Satisfaction with all the types of support (emotional, material, esteem, and informative) from the spouse reduced the psychological disorders in mothers as much in the prenatal compared to the postpartum period [59]. Among immigrant mothers in Taiwan from China or Vietnam, emotional support was found to be significantly and inversely associated with postpartum depression [43]. Emotional and informational support were identified as the most important types of social support for postpartum anxiety [48]. Marginal structural models were employed to evaluate the time-varying associations of low social support (before and in early pregnancy) with depression in late pregnancy in a cohort of Peruvian women, and analyses suggested that women with sustained low scores on the 6-item Sarason Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ-6) were at higher risk of antepartum depression [68]. The authors also found a stronger association of fewer persons providing social support on depression risk than low social support satisfaction.

Others have found that not all forms of social support during a woman’s transition into motherhood are equally beneficial in alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms. Razurel et al. reported that support provided by one’s partner buffered the effects of stress on depression, although support from friends or professionals did not [60]. Although social support from family and friends was deemed less prominent than that from the spouse, studies [44,59] showed that these sources of support also had an influence on maternal mental health. A study evaluating the impact of family relationships and support on perinatal depressive symptoms between the third trimester of pregnancy and two to six months postpartum noted that the incidence and persistence of depression symptoms were predicted by lower baseline perceived emotional support from the mother-in-law and the husband, respectively [41]. In a large population-based study, increases in partner and family support had a more protective effect against anxiety and stress, and higher than average levels of anxiety and stress led to maternal-reported decreases in support [57].

Some studies [50,65,66] did not find associations between low perceived social support during pregnancy and postpartum depression. Ohara et al. [54] showed that satisfaction with social support did not directly predict depression in the postpartum period at a statistically significant level. Further, their path model revealed that less satisfaction with the social support received during pregnancy was rather a cause of postpartum depression. This indirect link of social support with depression in the postpartum period is in line with another study with slightly larger sample size, one year later, by the same first author [55]. While one study [52] found that the number of supportive persons during pregnancy had a more substantial effect on decreasing postpartum depressive symptoms in depressed relative to non-depressed mothers, their analyses also showed that satisfaction with social support was not a significant predictor of postpartum depression. The inconsistent findings on social support and depression and anxiety across included studies can be partially attributed to varying operational definitions of social support, utilization of different self-report social support and depression measures, and insufficient control for confounding variables.

Social isolation/Loneliness

Given that both these concepts were concurrently assessed in addressing mental health outcomes in some studies, articles that met the inclusion criteria of the current review and examined the subjective counterpart of social isolation were included in Table 2. This table presents characteristics of selected studies that explored the impact of social isolation on depression and anxiety disorders. The included studies reported on a total of 22,976 older adults aged 50 and above in European countries and Japan. The number of participants in the studies varied considerably, from 285 participants with a primary diagnosis of depression in a two-year follow-up study to 5,066 in a report on a well-characterized cohort of adults from Ireland [69]. Social isolation and loneliness (perceived social isolation) are intricately related, albeit conceptually distinct.

All these studies have identified social isolation and/or loneliness as a potential risk factor for depression and anxiety among older adults [69–77]. Domènech-Abella and colleagues evaluated data from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing and Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, in Ireland and the Netherlands, respectively. Social isolation and loneliness were identified as antecedent risk factors for incident depression or exacerbating late-life generalized anxiety or major depressive disorder independently [69]. The authors emphasized the need to address the subjective aspects of social isolation through interventions aimed at improving the characteristics of middle-aged and older adults’ social environments in order to improve their mental health.[69,70]. Holvast et al. [74] found that loneliness was independently associated with more severe depressive symptoms at follow-up (β = 0.61; 95% CI 0.12–1.11). These findings are in line with those of a cohort study of adults aged 50 and older, that found that loneliness was linked to depression or increased depressive symptoms, irrespective of objective social isolation, social support, or other potential confounders such as polygenic risk profiles, and that this association persisted 12 years after loneliness had been reported [75]. Similar effects were observed in a cross-national longitudinal study that assessed the relationship between social isolation and depression onset in England and Japan [77], as well as in a study of German primary care sample of the oldest old, those aged 80 years and over [72]. Elderly people who have lost a spouse are at higher risk, as insufficient social network may increase social isolation, potentially contributing to subsequent depressive symptoms [72]. Even after adjusting for the effect of widowhood and other confounders, Martín-María and colleagues [76] found both types of loneliness (i.e., transient and chronic) to be significantly associated with depression. Another study found that participants who scored high on the subjective appraisal of social isolation, measured by six-item de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale with subscales for emotional loneliness (perceived absence of intimate relationships) and social loneliness (perceived lack of a wider circle of friends and acquaintances), at baseline had a lower likelihood of achieving remission two years later [74].Three studies [71–73] utilized the Lubben Social Network Scale, a validated instrument designed to gauge social isolation in the elderly.

Analysis of Cognitive Function and Ageing Study-Wales (CFAS-Wales) by Evans et al. (2019) showed that people with depression or anxiety experience poorer social relationships and higher social isolation and loneliness relative to those without such symptomatology, despite reporting an equivalent level of social contact [71]. The apparent reductions in negative affect at follow-up in over half of the respondents with clinically relevant depression or anxiety, diagnosed using the Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer-Assisted Taxonomy (AGECAT) algorithm, at baseline could be due to biopsychosocial changes intrinsic to ageing and/or cohort effects. Results by Herbolsheimer et al. (2018) opposed previous findings, stating that social isolation from friends and neighbors at the baseline was not directly associated with depressive symptoms at the 3-year follow-up [73]. Of importance, the authors also showed that being socially isolated from friends and neighbors was related to lower levels of out-of-home physical activity, which predicted more depressive symptoms after three years (β = .014, 95% CI .002 to .039) [73]. These reported findings demonstrate the potentially detrimental effect of objective and subjective social isolation on mood disorders in later life. Extant evidence suggests the importance of considering both social isolation and loneliness without the exclusion of the other in efforts to mitigate risk.

Social networks

Eight studies, i.e., ten papers, were identified that examined the longitudinal relationship between social networks and depression or anxiety (see Table 3). Seven [69,70,78–83] of the eight included studies on social networks focused on older adults. Community-dwelling individuals aged 75 and older with restricted social networks were more likely to develop depression compared to those who maintained an integrated social network [80]. While it has also been noted that respondents who experienced social loss within the last six months reported a higher risk of depression in old age, the adverse effects of loss on depression could be attenuated by the existence of an integrated social network [80]. According to a study conducted among Korean couples aged 60 years and older, spousal network overlap was associated with less depression concordance for husbands, however not for wives, which indicates the need for gender-specific strategies to support psychological well-being of older adults. [78]. In a large follow-up study spanning ten years that recruited older female nurses, lower social networks increased the risk of incident late-life depression in age-adjusted models [79]. In line with these results, another study on the elderly showed that a smaller network size measured using the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index is a robust risk factor of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder [69]. Conversely, one study on American adults aged 57–85 years denies this relationship as no direct effects of social networks on frequencies of depression symptoms were detected at follow-up [82]. It is worth noting that the same study also showed that social networks predicted higher levels of perceived isolation (β = 0·09; p<0·0001), which in turn predicted higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms (β = 0·12; p<0·0001) [82]. According to papers [29,30] that used data from NESDA and NESDO, the size of social networks at baseline did not predict depression at follow-up. For adults with a pre-existing diagnosis of major depressive disorder, only the social network characteristic of living in a larger household was reported to have a unique predictive value for depression course [30].