Abstract

Purpose

Assess the safety, tolerability, and feasibility of subcutaneous administration of the mitochondrial-targeted drug elamipretide in patients with dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and noncentral geographic atrophy (NCGA) and to perform exploratory analyses of change in visual function.

Design

Phase 1, single-center, open-label, 24-week clinical trial with preplanned NCGA cohort.

Participants

Adults ≥ 55 years of age with dry AMD and NCGA.

Methods

Participants received subcutaneous elamipretide 40-mg daily; safety and tolerability assessed throughout. Ocular assessments included normal-luminance best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), low-luminance BCVA (LLBCVA), normal-luminance binocular reading acuity (NLBRA), low-luminance binocular reading acuity (LLBRA), spectral-domain OCT, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and patient self-reported function by low-luminance questionnaire (LLQ).

Main Outcome Measures

Primary end point was safety and tolerability. Prespecified exploratory end-points included changes in BCVA, LLBCVA, NLBRA, LLBRA, geographic atrophy (GA) area, and LLQ.

Results

Subcutaneous elamipretide was highly feasible. All participants (n = 19) experienced 1 or more nonocular adverse events (AEs), but all AEs were either mild (73.7%) or moderate (26.3%); no serious AEs were noted. Two participants exited the study because of AEs (conversion to neovascular AMD, n = 1; intolerable injection site reaction, n = 1), 1 participant discontinued because of self-perceived lack of efficacy, and 1 participant chose not to continue with study visits. Among participants completing the study (n = 15), mean ± standard deviation (SD) change in BCVA from baseline to week 24 was +4.6 (5.1) letters (P = 0.0032), while mean change (SD) in LLBCVA was +5.4 ± 7.9 letters (P = 0.0245). Although minimal change in NLBRA occurred, mean ± SD change in LLBCVA was –0.52 ± 0.75 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution units (P = 0.005). Mean ± SD change in GA area (square root transformation) from baseline to week 24 was 0.14 ± 0.08 mm by FAF and 0.13 ± 0.14 mm by OCT. Improvement was observed in LLQ for dim light reading and general dim light vision.

Conclusions

Elamipretide seems to be well tolerated without serious AEs in patients with dry AMD and NCGA. Exploratory analyses demonstrated possible positive effect on visual function, particularly under low luminance. A Phase 2b trial is underway to evaluate elamipretide further in dry AMD and NCGA.

Keywords: Dry age-related macular degeneration, Elamipretide, Geographic atrophy, Mitochondrial dysfunction, Phase 1 clinical trial

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AE, adverse event; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study; FAF, fundus autofluorescence; GA, geographic atrophy; LLBCVA, low-luminance best-corrected visual acuity; LLBRA, low-luminance binocular reading acuity; LLQ, low-luminance questionnaire; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; NCGA, noncentral geographic atrophy; NLBRA, normal-luminance binocular reading acuity; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SD, standard deviation

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in people 50 years of age and older, affecting an estimated 11 million individuals in the United States, with AMD prevalence expected to double to 22 million individuals by 2050 (10% of those 50 years of age and older).1,2 The most profound visual impairment occurs in untreated neovascular AMD or in advanced dry AMD with foveal center-involving geographic atrophy (GA), both of which can cause severe central vision loss.1 However, patients with noncentral GA (NCGA), as well as patients with high-risk drusen, also experience significant visual impairment.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Despite good best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA; i.e., often 20/40 or better), these patients frequently experience moderate to profound impairment in low-luminance visual function and activities of daily living (e.g., driving at dusk, dim light reading, others).8 Low-luminance vision impairment affects up to 50% of patients with NCGA,9,10 thus representing a significant unmet clinical need.

An emerging body of evidence suggests an important role for retinal mitochondrial dysfunction in AMD pathobiology.11, 12, 13 Multiple risk factors associated with AMD—including cigarette smoke, lipofuscin accumulation within the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and complement dysregulation—have been identified as triggers of mitochondrial dysfunction.14, 15, 16 Oxidant-induced modifications as well as mutations in mitochondrial DNA of RPE cells are more prevalent in human eyes with AMD than in eyes of age-matched control eyes, and the morphologic features of RPE mitochondria in eyes with AMD often are enlarged and dysmorphic (indicating dysfunction), as compared with the RPE mitochondria of control eyes.13,16,17 Additionally, patients with certain genetic mitochondrial disorders, especially maternal inherited diabetes and deafness and mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes, often demonstrate GA or other signs of macular degeneration.18, 19, 20 The mechanisms of visual impairment in the setting of mitochondrial dysfunction have not been elucidated clearly, but may be related to alterations in cellular bioenergetics (i.e., diminished [adenosine triphosphate] ATP production); aberrant oxidant production at the RPE, photoreceptors, or both; or a combination thereof, leading to altered phototransduction, impaired visual cycle, or insufficient metabolic support.11,16,21

Elamipretide is a first-in-class investigational drug and mitochondria-targeted tetrapeptide that was evaluated previously in mitochondrial diseases such as primary mitochondrial myopathy and Barth syndrome.22 Elamipretide increases cellular ATP production and reduces mitochondria-derived oxidants in affected cells by stabilizing the structure and function of the mitochondrial electron transport chain.23, 24, 25, 26 Elamipretide’s mechanism of action suggests that it could modulate the mitochondrial-mediated pathophysiologic processes involved in dry AMD.24,27 The ReCLAIM study was a phase 1 clinical trial with the primary objective of evaluating the safety and tolerability of elamipretide in 2 preplanned cohorts of patients with dry AMD: (1) patients with dry AMD and noncentral, fovea-sparing GA (NCGA); and (2) patients with intermediate AMD, that is, high-risk drusen without GA. Exploratory objectives included evaluation of changes from baseline in measures of visual function and in GA area. The study protocol prespecified relevant inclusion criteria for each cohort and that the 2 cohorts would be analyzed separately. This report details the findings of the NCGA cohort; results of the high-risk drusen cohort are included in a companion report.28

Methods

Study Design

This was a phase 1, single-center, 24-week, open-label clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02848313). The study was conducted in accordance with ICH GCP Guidelines and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Duke Health Institutional Review Board (Durham, NC). After giving informed consent and study enrollment, prospective participants underwent a screening assessment (≤14 days before the baseline visit) to verify study eligibility, which included physical and ophthalmic examination, measurement of Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) scale BCVA under normal luminance (i.e., standard light) and low-luminance conditions, spectral-domain OCT, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), fluorescein angiography, and assessment with a low-luminance questionnaire (LLQ; adapted from Owsley et al8; see Supplemental Appendix 1).

Participants

A detailed list of eligibility criteria is included in Supplemental Appendix 2. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized below.

Inclusion Criteria

For the NCGA cohort, men and women 55 years of age or older with dry AMD and NCGA were eligible for enrollment, with a single eye designated as the study eye. Noncentral GA was defined as a well-demarcated area(s) of GA by FAF, sparing the foveal center (i.e., center having intact RPE and outer retinal ellipsoid zone layer) by OCT. The cumulative GA lesion size (solitary or multifocal) was required to be: (1) 1.27 mm2 or more (approximately ≥ 0.5 disc area) and less than 10.16 mm2 (approximately < 4 disc areas), and (2) to reside completely within the FAF imaging field (30° image centered on the fovea). No other size requirements were specified for a single GA lesion as long as the above-specified size criteria were met. Participants also were required to have: (1) detectable rim area hyperautofluorescence adjacent to the area of GA by FAF, (2) no evidence of choroidal neovascularization (active or prior history) in the study eye, (3) normal-luminance BCVA of 55 ETDRS letters or more (i.e., Snellen equivalent, ≥ 20/70), (4) low-luminance BCVA (LLBCVA) deficit of more than 5 letters (where LLBCVA deficit defined as the difference between BCVA and LLBCVA), and (5) at least 2 LLQ abnormal subscale scores indicating impairment, wherein one of the abnormal subscales was either general dim-light vision or dim-light reading (where abnormal subscale was defined as ≥ 50% of questions in that subscale with answers of 3 [some difficulty] or 4 [a lot of difficulty] with specific low-luminance tasks or functions). The fellow eye was permitted to have any stage of AMD: intermediate AMD with high-risk drusen, AMD with NCGA, neovascular AMD, or advanced AMD with center-involving GA. Ongoing treatment with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor therapies in the fellow eye was permitted.

Participants also were required to have either no visually significant cataract or pseudophakia without posterior capsular opacity, along with sufficiently clear ocular media, adequate pupillary dilation, fixation to permit quality fundus imaging, and ability to cooperate sufficiently for adequate ophthalmic visual function testing and anatomic assessment. When both eyes were eligible for the study, the eye with the greater low-luminance visual acuity deficit was chosen for inclusion.

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria included any of the following ocular conditions in the study eye: AMD with any evidence of central GA (i.e., involving the foveola by OCT), diagnosis of neovascular AMD, or macular atrophy resulting from causes other than AMD. Additional macular and retinal exclusion criteria in the study eye included: presence of diabetic retinopathy, macular pathologic features (i.e., hole, pucker), history of retinal detachment, and presence of vitreous hemorrhage. Nonmacular exclusion criteria in the study eye included: uncontrolled glaucoma; advanced guttae indicative of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy; and visually significant cataract, presence of significant posterior capsular opacity in the setting of pseudophakia, aphakia, or significant keratopathy that would alter visual function, especially in low light conditions. Prior treatment exclusion criteria in the study eye included previous intravitreal injection of pharmacologic agents or implants (including anti-angiogenic [anti–vascular endothelial growth factor] drugs and corticosteroids); prior vitreoretinal surgery (including vitrectomy surgery and submacular surgery); prior treatment with macular laser, verteporfin, external-beam radiation therapy, or transpupillary thermotherapy; or any ocular incisional surgery (including cataract surgery) in the study eye in the 3 months preceding the baseline visit. Additional exclusion criteria included the presence of any of the following ocular conditions in either eye: active uveitis, vitreitis, or both; history of uveitis; and active infectious disease (conjunctivitis, keratitis, scleritis, endophthalmitis, etc.). Finally, individuals known to be immunocompromised, individuals receiving systemic immunosuppression for any disease, and individuals with estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 ml/minute were excluded from study participation.

Study Drug and Evaluations

The study drug elamipretide was administered as a 40-mg (1-ml) subcutaneous injection in the abdominal area once daily for 24 weeks, beginning at baseline. The study drug was either self-administered by the participant or by a caregiver, after training by study personnel at the initial baseline visit. Participants were trained using a standard script explaining the importance of proper administration of the drug daily for the 24-week study treatment period. The first dose could be given by a qualified member of the study team, by the participant, or caregiver at the investigator’s discretion. The option of a home health nurse making visit(s) to the participant and caregiver to oversee and verify proper study drug administration was offered to each participant and was provided to participants, as needed, and the number of nurse visits was recorded for each participant. Assessments for safety and tolerability were performed throughout the 24-week treatment period and at the follow-up visit (week 28). Adverse events (AEs) were assessed by the investigator for severity and relationship to study drug. Participants were asked to complete a diary documenting study drug administration and compliance. Compliance was assessed by study personnel assessment of participant diary and inventory of used study drug vials over the course of the active treatment period.

For ocular assessments, although only 1 eye of each eligible participant was designated as the study eye, all specified ophthalmic testing was performed on both eyes at each time point. Assessments of BCVA (ETDRS letter score) under normal luminance and low luminance were performed at screening and baseline, during the active treatment period (weeks 1, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24), and at follow-up (week 28). Best-corrected visual acuity and LLBCVA were measured as the correct number of letters read using standard ETDRS charts, lighting, and procedures. For LLBCVA, participants were fitted with trial frames with their best-corrected refraction and a 2.0-log unit neutral density filter to replicate low-luminance conditions under standardized ambient lighting.

Best-corrected binocular reading acuity and low-luminance binocular reading acuity (LLBRA) were measured at baseline, during study treatment (weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24), and at follow-up (week 28). Assessment of best-corrected binocular reading acuity was carried out by standardized illumination using several different standard MNREAD charts (MNREAD 1-W, 2-W, and 3-W charts; Precision Vision, Lasalle, IL). Charts were rotated at visits throughout the study and a single chart was not used at consecutive visits to reduce the likelihood of learning effect. Participants were fitted with trial frames with best-corrected near-acuity lenses in standardized ambient lighting conditions, and results were recorded as the smallest font size read correctly with 1 word or fewer mistakes within 30 seconds. The MNREAD reading chart comprises 19 distinct font sizes ranging from –0.5 logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR; smallest font size; Snellen equivalent, 20/6) to 1.3 logMAR (largest font size; Snellen equivalent, 20/400), with a total range in values of 1.9 logMAR.

Low-luminance binocular reading acuity was assessed in the same fashion as best-corrected binocular reading acuity, with MNREAD 1-W, 2-W, and 3-W charts again rotated at visits throughout the study and a single chart not being used at consecutive visits to reduce the likelihood of learning effect. For LLBRA, a 2.0-log unit neutral density filter was added to trial frames with best-corrected near-acuity lenses to replicate low-luminance conditions. Results were recorded as the smallest font size read correctly (range, –0.5 to 1.3 logMAR) with 1-word of fewer mistakes within 30 seconds. If participants were unable to read the 1.3-logMAR line (i.e., largest font size) using the 2.0-log unit neutral density filter, then LLBRA was repeated using a 1.0-log unit neutral density filter. The final adjusted logMAR value for measurements obtained with 1.0-log unit neutral density filter was derived by adding 1.9 to the measured value, such that the adjusted logMAR value ranged between 1.4 logMAR (smallest font size) to 3.2 logMAR (largest font size).

The LLQ (adapted from Owsley et al8; Supplemental Appendix 1) was performed at baseline as described and was repeated subsequently at weeks 12 and 24 and at follow-up (week 28). The LLQ was scored and analyzed as described previously.8 In brief, items in the LLQ had a difficulty response scale and corresponding scores: 1 = no difficulty at all, 2 = a little difficulty, 3 = some difficulty, and 4 = a lot of difficulty. The option of “X, does not apply to me” was included in case a particular item was not applicable for a participant, and in this case, the item was not included in determining the subscale score. The subscale score was calculated by scaling each item response from 0 to 100, wherein 100 reflects the highest functional level and 0 reflects the lowest functional level; the mean value was determined for the applicable items comprising each subscale.

For assessment of GA, OCT of the macula and FAF were performed at screening, baseline, during study treatment (weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24), and at follow-up (week 28), with measurement of GA area assessed on each imaging method performed by masked graders (M.J.A., P.S.M., and S.W.C.), who were masked to the date of performance and study visit. For FAF, masked graders demarcated the margins of GA lesions, defined as discrete regions of hypoautofluorescence within the FAF imaging field (field 2°–30° image centered on the fovea), determined lesion areas, and determined the cumulative GA lesion area (in square millimeters). For OCT, graders assessed OCT B-scan images to identify the margins of GA lesion, defined as the presence of choroidal hypertransmission, absence or disruption of RPE, and overlying photoreceptor loss (ellipsoid zone loss, absence of external limiting membrane, outer nuclear layer thinning). The GA margin was identified as the transition point between intact and disrupted or absent or attenuated RPE. OCT B-scans were registered to OCT infrared images, and the margin points were identified on infrared images to determine the cumulative GA area (in square millimeters). Square root transformation was performed on GA area measurements to eliminate the dependence of growth rates on baseline GA lesion measurements.

End Points

The primary study end point was safety and tolerability as assessed by the incidence and severity of AEs and changes from baseline in vital sign measurements, electrocardiography findings, clinical assessments, and clinical laboratory evaluations. Assessment of AEs was performed at each study visit and included both investigator-assessed and participant-reported events. Exploratory efficacy end points reported in the present study included changes from baseline in BCVA, LLBCVA, NLBRA, LLBRA, LLQ, and GA area.

Statistical Analysis

For this phase 1, open-label study, a sample size of 40 evaluable participants was considered sufficient to allow preliminary assessment of safety and tolerability, based on precedent set by prior phase 1 studies of similar nature and design. As mentioned, the high-risk drusen and NCGA cohorts were preplanned by study design. Safety and efficacy variables are summarized descriptively. All participants who received 1 dose or more of study drug were included in assessment of safety as part of the intention-to-treat analysis. Because this was an open-label study without a control or comparator group, analyses of exploratory efficacy end points were limited to descriptive analyses. Analyses of change in each metric from baseline to 24 weeks were limited to participants who completed the 24-week study period. Missing data were not imputed (e.g., by last observation carried forward) to avoid making assumptions about the outcomes of study participants that did not complete the study. All statistical analyses and reporting were performed using the SAS System version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Continuous variables analyzed in this study were summarized by the number of nonmissing observations, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum values. Statistical analysis of mean change from baseline value was assessed by signed-rank test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between GA area at baseline and the change in LLBCVA at week 24 from baseline. To correct for multiple comparisons for changes in metrics from baseline, the Holm method was applied to determine the statistically significant threshold (P value) for the α level (type I error rate) for each metric, based on the P value threshold P < 0.05 for the metric with the highest P value.29 For example, using the Holm method, for the 4 metrics BCVA, LLBCVA, NLBRA, and LLBCVA, the P values were ordered from lowest to highest to identify the statistically significant threshold for each: P < 0.0125 for the lowest P value among the 4 metrics, P < 0.0167 for the second lowest P value among the 4 metrics, P < 0.025 for the next to highest P value among the 4 metrics, and P < 0.05 for the highest P value among the 4 metrics.29

Results

Study Participants

A total of 19 participants were included in the NCGA cohort (Table 1). The mean age was 76 years and most participant were women (11/19) and were current or former smokers (11/19). Of the 19 enrolled, 15 participants completed the 24-week treatment period. Of the 4 individuals who did not complete the study, 1 participant discontinued participation because of study drug intolerance in the form of pruritus and discomfort at the injection site (before the week 4 visit), 1 participant was discontinued by study investigator because of conversion to neovascular AMD (just after the week 8 visit), 1 participant chose to withdraw from the study because of the participant’s perception of lack of efficacy of the study drug (at week 12), and 1 participant withdrew from the study (at week 20) because they did not wish to continue with study visits.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with Noncentral Geographic Atrophy (n = 19)

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |

| Mean ± SD | 76.0 ± 8.22 |

| Range | 64–96 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 (57.9) |

| Male | 8 (42.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (5.3) |

| White | 18 (94.7) |

| Former smoker∗ | 11 (57.9) |

| Baseline BCVA | 73.7 ± 9.5 |

| Baseline LLBCVA | 43.9 ± 19.8 |

| Baseline NCGA area | |

| FAF | 3.46 ± 3.39 |

| OCT | 3.28 ± 3.23 |

BCVA = best-corrected visual acuity; FAF = fundus autofluorescence; LLBCVA = low-luminance best-corrected visual acuity; NCGA = noncentral geographic atrophy; SD = standard deviation.

Data are presented as no. (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

Former smoker; no participants were active smokers.

Feasibility and Compliance

Subcutaneous administration of elamipretide was highly feasible after proper instruction of participants and caregiver by study personnel and health nurse home visits to instruct and verify proper drug administration. The mean ± SD number of home visits required to ensure proper subcutaneous administration of elamipretide was 2.5 ± 1.02 visits. Mean ± SD treatment compliance across the 24-week active study drug period was 97.3 ± 6.7%.

Safety and Tolerability

Adverse events are summarized in Table 2. All study participants experienced at least 1 AE, all of which were either or mild (73.7%) or moderate (26.3%) in intensity. The most common treatment-emergent AEs were injection site reactions, defined as a local reaction at the site of subcutaneous administration (including pruritus, erythema, discomfort, swelling, induration, and bruising). In most cases, these reactions were mild, self-limited, amenable to local treatment, or a combination thereof; 1 participant discontinued study drug because of intolerance to pruritus at the injection site, which in this instance was considered to be of moderate intensity.

Table 2.

Adverse Events in Patients with Noncentral Geographic Atrophy (n = 19)

| Event | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| All treatment-emergent events | |

| Any treatment-emergent AE | 19 (100) |

| Injection site reactions | |

| Pruritus | 17 (89.5) |

| Erythema | 14 (73.7) |

| Induration | 14 (73.7) |

| Bruising | 13 (68.4) |

| Hemorrhage | 7 (36.8) |

| Pain | 6 (31.6) |

| Urticaria | 4 (21.1) |

| Extravasation | 2 (10.5) |

| Swelling | 1 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 3 (15.8) |

| Headache | 2 (10.5) |

| Dizziness | 2 (10.5) |

| Pyrexia | 2 (10.5) |

| Nausea | 2 (10.5) |

| Gastroenteritis, viral | 2 (10.5) |

| AE by maximum intensity | |

| Mild | 14 (73.7) |

| Moderate | 5 (26.3) |

| Related to study drug | 18 (94.7) |

| AE leading to study drug discontinuation | 2 (10.5) |

| Any serious systemic AE∗ | |

| Urinary traction infection | 1 (5.3) |

| Sepsis | 1 (5.3) |

| All treatment-emergent ocular events in study eye | |

| Any treatment-emergent ocular AE | 2 (10.5) |

| Neovascular AMD | 1 (5.3) |

| Vitreous floaters | 1 (5.3) |

| AE by maximum intensity | |

| Mild | 1 (5.3) |

| Moderate | 1 (5.3) |

| Related to study drug | 0 |

| AE leading to study drug discontinuation | 2 (10.5) |

| Any serious ocular AE | 0 |

AE = adverse event; AMD = age-related macular degeneration.

Both serious systemic AEs occurred in the same participant.

Two treatment-emergent serious AEs and no deaths occurred during the study. Both serious AEs, urinary tract infection (n = 1) and sepsis (n = 1), occurred in the same participant, were of moderate intensity, and were not considered related to study drug; both events resolved with full recovery of the participant. Two study participants experienced ocular AEs in the study eye; conversion to neovascular AMD (n = 1; moderate intensity) and vitreous floaters (n = 1; mild intensity), but both events were not considered related to study drug (Table 2). As noted above, the participant with conversion to neovascular AMD was withdrawn from the study by the study investigator. Two participants reported an ocular AE in the nonstudy eye, both of which were of mild intensity and were not related to the study drug.

Exploratory Efficacy End Points

Mean ± SD normal-luminance BCVA was 77.9 ± 12.7 letters at week 24 compared with 73.7 ± 9.5 letters at baseline. Normal-luminance BCVAs over the course of the study period are summarized in Figure 1. Among the 15 participants who completed the active study period, the mean change in BCVA from baseline increased progressively over time, with a mean ± SD increase of 4.6 ± 5.1 letters (P = 0.0032; P < 0.0125, Holm method threshold for statistical significance) at week 24 (Fig 1A, B). Six of 15 participants (40%) achieved at least a 6-letter increase in BCVA at week 24, and 2 of 15 participants (13.3%) achieved a more than 10-letter increase in BCVA at week 24; no individuals showed more than 5-letter decrease in BCVA (Fig 1B, C).

Figure 1.

Effects of elamipretide on best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). A, Line graph showing the mean change in BCVA (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] letters) from baseline (day 0) over the 24-week active study period. Bars indicate standard deviation (SD). ∗∗P = 0.0032 for mean change value at week 24 vs. baseline; P < 0.0125, Holm method threshold for statistical significance. B, Scatterplot showing the change in BCVA (ETDRS letters) from baseline at week 24. Horizontal solid line = mean value; vertical dashed line = SD. C, Bar graph showing the percentage of study participants by categorical change in BCVA (ETDRS letters) from baseline at week 24.

Mean ± SD LLBCVA was 51.5 ± 21.8 letters at week 24 compared with 44.0 ± 19.8 letters at baseline. Low-luminance BCVAs over the course of the study period are summarized in Figure 2. Mean increase in LLBCVA from baseline was observed at all study visits throughout the study period, with a mean ± SD increase of +5.4 ± 7.9 letters (P = 0.0245; P < 0.025, Holm method threshold for statistical significance) at 24 weeks (Fig 2A, B). Eight of 15 participants (53.3%) achieved at least a 6-letter increase in LLBCVA, 5 of 15 participants (33.3%) achieved a more than 10-letter increase in LLBCVA, and 1 of 15 participants (6.7%) achieved a more than 15-letter increase in LLBCVA (Fig 2B, C). Two of 15 participants (13.3%) showed at least a 6-letter decrease in LLBCVA (Fig 2B, C).

Figure 2.

Effects of elamipretide on low-luminance best-corrected visual acuity (LLBCVA). A, Line graph showing the mean change in LLBCVA (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study [ETDRS] letters) from baseline (day 0) over the 24-week active study period. Bars indicate standard deviation (SD). ∗∗P = 0.0245 for mean change value at week 24 vs. baseline; P < 0.025, Holm method threshold for statistical significance. B, Scatterplot showing the change in LLBCVA (ETDRS letters) from baseline at week 24. Horizontal solid line = mean value; vertical dashed line = SD. C, Bar graph showing the percentage of study participants by categorical change in LLBCVA (ETDRS letters) from baseline at week 24.

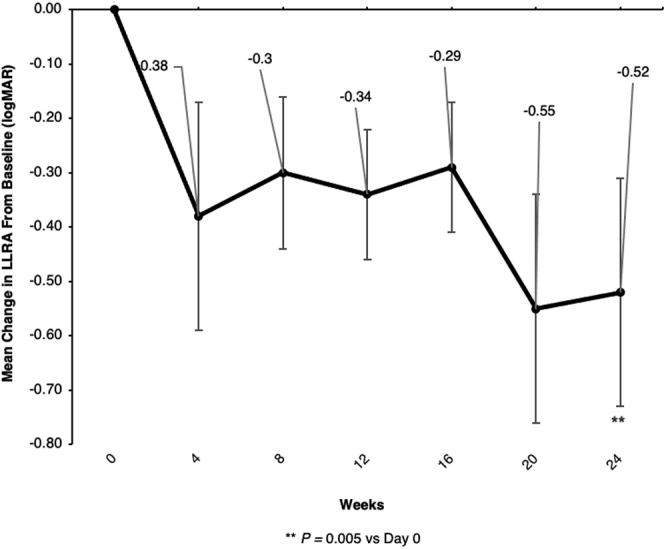

Mean ± SD NLBRA at week 24, 0.13 ± 0.26 logMAR, was not appreciably different from that at baseline, 0.15 ± 0.25 logMAR; mean change from baseline was –0.02 logMAR (P = 0.55; P < 0.05, Holm method threshold for statistical significance). In contrast, mean ± SD LLBRA at week 24 was 0.79 ± 0.97 logMAR compared with a baseline value of 1.28 ± 1.07 logMAR. Increase in LLBRA was observed at all study visits throughout the study period, with a mean LLBRA change from baseline in the smallest line read correctly of −0.52 logMAR at week 24 (P = 0.005; P < 0.0167, Holm method threshold for statistical significance; Fig 3), equivalent to an approximately 5-line gain in LLBRA.

Figure 3.

Line graph showing the effects of elamipretide on low-luminance binocular reading acuity (LLBRA). Mean change in LLBRA (in logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution units) from baseline (day 0) over the 24-week active study period. Bars indicate standard deviation. ∗∗P = 0.005 for mean change value at week 24 vs. baseline; P < 0.0167, Holm method threshold for statistical significance.

For the LLQ, subscale scores at week 24 as well as changes in subscale scores at week 24 from baseline are included in Table 3. Using Holm method thresholds for statistical significance to correct for multiple comparisons of subscales on the LLQ, mean changes from baseline were not statistically significant, although notable improvements were found in general dim light vision (P = 0.0292) and dim light reading (P = 0.0271) that trended toward clinical significance.

Table 3.

Low-Luminance Questionnaire Scores at Week 24

| Subscale Score | Observed Score at Week 24 |

Change from Baseline at Week 24 |

P Value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | No. | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Dim light reading | 15 | 40.8 | 16.00 | 37.5 | 25.0 | 81.3 | 15 | 7.1 | 11.30 | 6.3 | –12.5 | 25.0 | 0.0292 |

| Driving or riding in car | 15 | 48.9 | 26.86 | 37.5 | 25.0 | 93.8 | 15 | 4.2 | 14.11 | 0.0 | –25.0 | 31.3 | 0.2719 |

| General dim light vision | 15 | 58.4 | 20.38 | 53.1 | 31.3 | 93.8 | 15 | 7.7 | 12.10 | 6.3 | –18.8 | 25.0 | 0.0271 |

| Light transitions and glare | 15 | 51.0 | 20.98 | 45.0 | 25.0 | 95.0 | 15 | 6.7 | 13.71 | 5.0 | –25.0 | 30.0 | 0.0807 |

| Mobility | 15 | 71.1 | 22.02 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 15 | 2.8 | 16.57 | 0.0 | –25.0 | 33.3 | 0.5266 |

| Other ADLs | 15 | 64.6 | 24.96 | 68.8 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 15 | 10.4 | 20.82 | 12.5 | –37.5 | 43.8 | 0.0731 |

| Peripheral vision | 15 | 61.7 | 32.55 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 100.0 | 15 | 5.8 | 24.03 | 0.0 | –50.0 | 50.0 | 0.3630 |

ADL = activity of daily living.

For change in GA lesion size, mean ± SD change in GA area at week 24 was increased at 0.50 ± 0.49 mm2 on FAF and 0.45 ± 0.61 mm2 on OCT. Mean ± SD change from baseline in GA area at week 24, measured by square root transformation (i.e., calculation performed to eliminate dependence of growth rates on lesion measurements), was increased at 0.14 ± 0.08 mm on FAF and 0.13 ± 0.14 mm on OCT. Good correlation was found between baseline GA area (square millimeters) on OCT and change in LLBCVA at week 24 from baseline (correlation coefficient, –0.6555; P = 0.008). In general, eyes with smaller GA area at baseline showed greater increase in LLBCVA at week 24, with all instances of a 6-letter increase or more in LLBCVA (n = 8) occurring in eyes with baseline GA area of less than 4 mm2 (approximately 1.6 disc areas) and an intact foveal ellipsoid zone.

Discussion

Dry AMD with GA represents an advanced form of AMD, characterized by foci of cell death at the RPE, attenuation of underlying choriocapillaris, and loss of overlying and marginal photoreceptors.12 Although the disease is variably progressive, the extent of associated visual deficit is related to several factors, including size and location of GA relative to the fovea as well as the rate and direction of GA enlargement.30 Progression of AMD disease produces increasing impairment in health-related quality of life, with a quality of life in moderate AMD (i.e., AMD with NCGA) comparable with that after a moderate stroke and quality of life in severe AMD (i.e., AMD with center-involving GA) similar to that found in patients with total renal failure receiving home dialysis.31 Currently, no treatments are approved to prevent GA, to limit its progression, or to improve vision for affected patients. The lack of efficacious therapies for dry AMD carries significant public health and societal burden, estimated at a total financial cost (direct and indirect) of $30 billion.31

Declines in visual function experienced by patients with dry AMD are especially apparent under low-luminance conditions, including difficulty reading in dimly lit conditions and driving at dusk or nightfall or in poor ambient light environments.8, 9, 10 These deficits in activities of daily living profoundly impact affected patients, in many cases causing loss of independence and social withdrawal. Low-luminance vision dysfunction is quantified by clinical end points of LLBCVA and LLBRA, which assess central cone-mediated function under standardized conditions.10,32,33 Therapies that specifically improve low-luminance visual function and boost LLBCVA and LLBRA thus represent a paradigm shift for patients with AMD.

Mitochondrial dysfunction at the RPE and neurosensory retina, characterized by excessive production of cellular oxidants (superoxide, singlet oxygen, and others) and diminished ATP production, seems to be an important contributor to AMD pathobiology.11,13,21 Retinal pigment epithelial cells in eyes from patients with AMD exhibit mitochondrial dysmorphologic features and oxidative damage with the effect proportional to disease severity.13,17,21 Preclinical mouse models of dry AMD, which are characterized by dysmorphic RPE and sub-RPE deposit formation, have abnormal RPE mitochondria along with biochemical evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction and increased superoxide production at the RPE.27,34,35 Additionally, induction of the ApoE4 dry AMD mouse model triggers neurosensory retina mitochondrial dysfunction in the setting of diminished electroretinography amplitudes and disrupted photoreceptor–bipolar cell synapses.27 These data strongly support mitochondrial dysfunction as a key disease paradigm for dry AMD.

The investigational drug elamipretide is a small peptide that reversibly binds cardiolipin, a phospholipid found only in the inner mitochondrial membrane that is responsible for establishing the cristae architecture and optimizing the function of the electron transport chain for ATP generation.23, 24, 25, 26 Binding of elamipretide to cardiolipin restores the efficiency of the electron transport chain in dysfunctional mitochondria, improving cellular respiration and ATP production and reducing production of oxidants.23, 24, 25, 26 The net effect is to restore niche cellular functions requiring high levels of ATP and to downregulate cellular response to injury pathways that are triggered by oxidants. Elamipretide has been shown to have significant activity in preclinical models of eye disease, with in vitro studies showing reduced oxidative stress, decreased apoptosis, and improved cell survival in cultured human RPE cells.24,36 Furthermore, in RPE cells cultured from dry AMD donor eyes, elamipretide treatment improved mitochondrial function, as measured by maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity.24 Finally, treatment of the ApoE4 mouse model of dry AMD, using a rigorous drug intervention strategy after induction of the model (as opposed to an pretreatment strategy before or concurrent with model induction), promoted reversal of mitochondrial dysfunction, regression of sub-RPE deposits, restoration of RPE cellular morphologic features, improvement in neurosensory retinal function by electroretinography, and restoration of phototransduction and synaptic integrity and function.27 It was on the basis of these compelling preclinical data that the elamipretide clinical development program was initiated for dry AMD.

Results from the present phase 1 ReCLAIM study demonstrated that subcutaneous administration of elamipretide generally is well tolerated without serious drug-related AEs in patients with AMD and NCGA. Treatment-emergent AEs, which primarily comprised injection site reactions, were mild or moderate in severity, with only 1 participant discontinuing study participation because of injection site reaction (pruritus). Two serious AEs occurred (urinary tract infection [n = 1] and sepsis [n = 1]) in the same patient, but neither of these was deemed to be related to the study drug, and both serious AEs resolved with recovery of the participant. Among ocular AEs occurring in the study eye (n = 2), none were severe or thought to be related to study drug, and only 1, conversion to neovascular AMD (n = 1), led to study drug discontinuation. The overall safety profile of elamipretide was comparable with that observed previously in other clinical trials of elamipretide.37,38

Elamipretide dose and frequency were selected based on maximum tolerated subcutaneous dosing from prior safety studies in adults. Although pharmacokinetics samples were not collected and analyzed in the present study, the pharmacokinetics profile of elamipretide administered via infusion has been characterized in other clinical trials (Stealth BioTherapeutics, data on file, 2017).39 In rabbit pharmacokinetics studies, subcutaneous dosing of elamipretide (1 mg/kg) produced measurable drug levels at the choroid, RPE, and retina at Cmax (30 minutes). The measured concentrations are expected to be therapeutic based on the exposure-response data from the mouse model of hydroquinone- (HQ) induced oxidative injury (Stealth BioTherapeutics, data on file). Studies of the pharmacokinetics of subcutaneous elamipretide in patients with AMD are included in the forthcoming phase 2 clinical trial.

Exploratory efficacy end points suggest that elamipretide may have a possible positive benefit on visual function in dry AMD and NCGA, particularly under low-luminance conditions. We observed increased mean change in both LLBCVA and LLBRA that was evident at early visits (i.e., day 7 and week 4) and subsequently was sustained over the duration of the study, suggesting a possible drug treatment effect. The phenomenon of short-term learning effect has been described in studies of other measures of visual function (e.g., microperimetry) in patients with dry AMD.40 It is possible that short-term learning effect could have contributed to observed changes in LLBCVA and LLBRA at early visits. However, as described in “Methods,” for LLBRA (and NLBRA), MNREAD charts were rotated at visits throughout the study, such that a single chart was not used at consecutive visits, to reduce the likelihood of a testing-specific learning effect. Furthermore, because the methodology for LLBCVA testing does not include added psychovisual aspects beyond what is encountered in the testing of normal-luminance BCVA, a learning effect specifically attributable to LLBCVA would be unexpected. The recent GA natural history study Proxima B (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02399072) demonstrated that patients with NCGA (with fellow-eye intermediate AMD) sustained a mean visual acuity loss of approximately 3 to 5 letters at the similar 6-month (24-week) assessment interval; neither a short-term learning effect for LLBCVA nor a spontaneous improvement in LLBCVA occurred at later points for patients in this study.9 This is of relevance because Proxima B included eyes of similar disease state and baseline LLBCVA as compared with those included in the NCGA cohort of the present ReCLAIM study.

In contrast, in the sham control arms of GATHER1, the phase 2b/3 clinical trial of avacincaptad pegol (Iveric Bio), mean change in LLBCVA from baseline to month 12 was –1.4 (standard error, 3.3) in the sham group for the 2-mg arm and +3.0 (standard error, 3.4) for the sham group for the 4-mg arm.41 In a natural history study of a cohort (n = 8) of patients with NCGA, Wu et al6 observed minimal change in LLBCVA from baseline to 12 months. The findings from these studies suggest the possibility that LLBCVA may not decline substantially over time or may demonstrate short-term improvement in some patients with dry AMD. Further, the coefficient of repeatability for LLBCVA in patients with intermediate AMD was found to be 9.34 letters by Chandramohan et al42 and approximately 6.5 letters by Wu et al.43 Although the present study showed findings in a cohort of NCGA patients rather than patients with intermediate AMD, visit-to-visit variation in LLBCVA and LLBRA must be taken into account when considering the potential for true differences attributable to study drug. The data from available and relevant literature highlight the importance of careful study design, end point measurement methodology, and patient selection in assessing change in low-luminance visual function in patients with AMD over time and, most importantly, underscore the critical need for a placebo control group to understand the true nature and magnitude of drug effect on low-luminance visual function in patients with NCGA.

With respect to effects on GA area, similarly, multiple caveats apply in interpreting observations, including the relatively short 24-week duration of the study, selection of patients with NCGA, and the normal variability across AMD populations for changes in GA size over time. We observed a mean increase in GA area (square root transformation) of 0.14 mm on FAF and 0.13 mm on OCT. Previously published studies of GA natural history at 6 months (24 weeks) have included increases in GA area (square root transformation) ranging from 0.17 to 0.19 mm.9,44,45 The limitations inherent in making cross-trial comparisons with other studies preclude substantive conclusions for patients with NCGA in the ReCLAIM study. If a reduced rate of GA progression is affirmed for elamipretide-treated patients in a placebo-controlled study, this would suggest the hypothesis that retinal or RPE mitochondrial dysfunction, or both, may contribute to progression of GA over time and further would suggest that the rate of GA progression could serve as an additional clinical efficacy end point for mitochondria-targeted drugs. Further evaluation in a placebo-controlled study is needed to address this possibility.

Although the study produced an acceptable safety profile as well as intriguing efficacy signals, care must be taken not to overinterpret the presented exploratory efficacy analyses. As we have noted, the lack of a placebo control group represents the most significant limitation for this study in considering the implications of the efficacy analyses. Because this was an open-label, uncontrolled, phase 1 safety with small sample size, the statistical approach also showed limitations because the rules for handling missing data were not prespecified. As such, efficacy analyses were restricted to the 15 participants who completed the study to avoid making assumptions about the outcomes of those individuals who discontinued study participation. The inability to account for the impact of the 4 participants’ withdrawals on efficacy analyses represents an additional limitation of the present study. However, we did adjust analyses for multiple comparisons to determine appropriate thresholds for statistical significance, after which, the observed changes from baseline to week 24 for BCVA, LLBCVA, and LLBRA remained statistically significant.

The observed, potentially positive, effects of elamipretide on visual function thus are highly promising and provide substantial support and justification for further investigation of elamipretide in clinical trials of dry AMD. Based on the results of this prespecified cohort analysis of patients with NCGA, a randomized, double-masked, multicenter phase 2b clinical trial (ReCLAIM 2; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03891875) is ongoing to continue the evaluation of safety and efficacy of subcutaneous administration of elamipretide in patients with dry AMD with NCGA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank James A. Shiffer, RPh, and Bret Fulton, RPh, for writing and formatting assistance with the manuscript.

Manuscript no. D-21-00045.

Footnotes

Supplemental material available atwww.ophthalmologyscience.org.

Disclosure(s):

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): P.S.M.: Consultant and Financial support – Stealth BioTherapeutics

M.J.A.: Consultant – Stealth BioTherapeutics; Financial support – Stealth BioTherapeutics, Ocuphire Pharma

S.W.C.: Consultant – Stealth BioTherapeutics; Financial support – Stealth BioTherapeutics, Bausch & Lomb, Lineage Cell Therapeutics, Merck

Funded by Stealth BioTherapeutics, Newton, MA. The sponsor participated in the design of the study, conducting the study, data collection, data management, and data analysis. After the authors’ preparation of the manuscript, the sponsor reviewed the manuscript before submission. However, the authors retained full and final control over data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing and content, and final decision to submit manuscript for publication.

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with ICH GCP Guidelines and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Duke Health Institutional Review Board. Following informed consent and study enrollment, prospective participants underwent a screening assessment.

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Mettu, Allingham, Cousins

Analysis and interpretation: Mettu, Allingham, Cousins

Data collection: Mettu, Allingham, Cousins

Obtained funding: N/A

Overall responsibility: Mettu, Allingham, Cousins

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Pennington K.L., DeAngelis M.M. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. Eye Vis (Lond) 2016;3:34. doi: 10.1186/s40662-016-0063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R., Klein B.E.K. The prevalence of age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in aging: current estimates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(14):ORSF5–ORSF13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunness J.S., Rubin G.S., Applegate C.A., et al. Visual function abnormalities and prognosis in eyes with age-related geographic atrophy of the macula and good visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1677–1691. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30079-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owsley C., McGwin G., Jackson G.R., et al. Cone- and rod-mediated dark adaptation impairment in age-related maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1728–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunness J.S., Rubin G.S., Broman A., et al. Low luminance visual dysfunction as a predictor of subsequent visual acuity loss from geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1480–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z., Ayton L.N., Luu C.D., Guymer R.H. Longitudinal changes in microperimetry and low luminance visual acuity in age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:442–448. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu S.T., Thompson A.C., Stinnett S.S., et al. Longitudinal study of visual function in dry age-related macular degeneration at 12 months. Ophthalmol Retina. 2019;3:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owsley C., McGwin G., Scilley K., Kallies K. Development of a questionnaire to assess vision problems under low luminance in age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:528–535. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holekamp N., Wykoff C.C., Schmitz-Valckenberg S., et al. Natural history of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: results from the prospective Proxima A and B clinical trials. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:769–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakravarthy U., Bailey C.C., Johnston R.L., et al. Characterizing disease burden and progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown E.E., Lewin A.S., Ash J.D. Mitochondria: potential targets for protection in age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;174:11–17. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75402-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mettu P.S., Wielgus A.R., Ong S.S., Cousins S.W. Retinal pigment epithelium response to oxidant injury in the pathogenesis of early age-related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:376–398. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terluk M.R., Kapphahn R.J., Soukup L.M., et al. Investigating mitochondria as a target for treating age-related macular degeneration. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7304–7311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0190-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrington D.A., Kapphahn R.J., Leary M.M., et al. Increased retinal mtDNA damage in the CFH variant associated with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2016;145:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marin-Castaño M.E., Csaky K.G., Cousins S.W. Nonlethal oxidant injury to human retinal pigment epithelium cells causes cell membrane blebbing but decreased MMP-2 activity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3331–3340. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaarniranta K., Uusitalo H., Blasiak J., et al. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;79:100858. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karunadharma P.P., Nordgaard C.L., Olsen T.W., Ferrington D.A. Mitochondrial DNA damage as a potential mechanism for age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5470–5479. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massin P., Virally-Monod M., Violettes B., et al. Prevalence of macular pattern dystrophy in maternally inherited diabetes and deafness. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1821–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)90356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latkany P., Ciulla T.A., Cucchillo P., Malkoff M.D. Mitochondrial maculopathy: geographic atrophy of the macula in the MELAS associated A to G 3243 mitochondrial DNA point mutation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:112–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rummelt V., Folberg R., Ionasescu V., et al. Ocular pathology of MELAS syndrome with mitochondrial DNA nucleotide 3243 point mutation. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1757–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riazi-Esfahani M., Kuppermann B.D., Kenney M.C. The role of mitochondria in AMD: current knowledge and future applications. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:424–428. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_182_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabbah H.N. Barth syndrome cardiomyopathy: targeting the mitochondria with elamipretide. Heart Fail Rev. 2021;26:237–253. doi: 10.1007/s10741-020-10031-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickel A., Kohlhaas M., Maack C. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production and elimination. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;73:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapphahn R., Terluk M., Ebeling M., et al. Elamipretide protects RPE and improves mitochondrial function in models of AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:1954. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birk A.V., Chao W.M., Bracken C., et al. Targeting mitochondrial cardiolipin and the cytochrome c/cardiolipin complex to promote electron transport and optimize mitochondrial ATP synthesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2017–2028. doi: 10.1111/bph.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szeto H.H. First-in-class cardiolipin-protective compound as a therapeutic agent to restore mitochondrial bioenergetics. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2029–2050. doi: 10.1111/bph.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cousins S.W., Saloupis P., Brahmajoti M.V., Mettu P.S. Mitochondrial dysfunction in experimental mouse models of SubRPE deposit formation and reversal by the mito-reparative drug MTP-131. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:2126. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allingham M.J., Mettu P.S., Cousins S.W. Phase 1 clinical trial of Elamipretide in intermediate age-related macular degeneration and high-risk drusen ReCLAIM High-Risk Drusen Study. Ophthalmology Science. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xops.2021.100095. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menyhart O., Weltz B., Győrffy B. MultipleTesting.com: a tool for life science researchers for multiple hypothesis testing correction. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleckenstein M., Mitchell P., Freund K.B., et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:369–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown G.C., Brown M.M., Sharma S., et al. The burden of age-related macular degeneration: a value-based medicine analysis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:173–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Datta S., Cano M., Ebrahimi K., et al. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2017;60:201–218. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cocce K.J., Stinnett S.S., Luhmann U.F.O., et al. Visual function metrics in early and intermediate dry age-related macular degeneration for use as clinical trial endpoints. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;189:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Espinosa-Heidmann D.G., Suner I.J., Catanuto P., et al. Cigarette smoke-related oxidants and the development of sub-RPE deposits in an experimental animal model of dry AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:729–737. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Espinosa-Heidmann D.G., Sall J., Hernandez E.P., Cousins S.W. Basal laminar deposit formation in APO B100 transgenic mice: complex interactions between dietary fat, blue light, and vitamin E. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:260–266. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cousins S.W., Mettu P.S., Brahmajothi M.V. The mitochondria-targeted peptide MTP-131 prevents hydroquinone-mediated persistent injury phenotype in cultured retinal pigment epithelium cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:829. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karaa A., Haas R., Goldstein A., et al. Randomized dose-escalation trial of elamipretide in adults with primary mitochondrial myopathy. Neurology. 2018;90:E1212–E1221. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butler J., Khan M.S., Anker S.D., et al. Effects of elamipretide on left ventricular function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the PROGRESS-HF phase 2 trial: effects of elamipretide in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2020;26:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daubert M.A., Yow E., Dunn G., et al. Novel mitochondria-targeting peptide in heart failure treatment. Circ Hear Fail. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Z., Ayton L.N., Guymer R.H., Luu C.D. Intrasession test-retest variability of microperimetry in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7378–7385. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaffe G.J., Westby K., Csaky K.G., et al. C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized pivotal phase 2/3 trial. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandramohan A., Stinnett S.S., Petrowski J.T., et al. Visual function measures in early and intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2016;36:1021–1031. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Z., Ayton L.N., Guymer R.H., Luu C.D. Low-luminance visual acuity and microperimetry in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1612–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yehoshua Z., Alexandre De Amorim Garcia Filho C., Nunes R.P., et al. Systemic complement inhibition with eculizumab for geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: the COMPLETE study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stetson P.F., Yehoshua Z., Garcia Filho C.A.A., et al. OCT minimum intensity as a predictor of geographic atrophy enlargement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:792–800. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.