Abstract

Since the first SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Wuhan, China, there has been continued concern over the link between SARS-CoV-2 transmission and food. However, there are few studies on the viability and removal of SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food. This study aimed to evaluate the viability of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices, depending on storage temperature, and inactivate the virus contaminating food using disinfectants. Two SARS-CoV-2 strains (L and S types) were used to contaminate lettuce, chicken, and salmon, which were then stored at 20,4 and −40 °C. The half-life of SARS-CoV-2 at 20 °C was 3–7 h but increased to 24–46 h at 4 °C and exceeded 100 h at −40 °C. SARS-CoV-2 persisted longer on chicken or salmon than on lettuce. Treatment with 70% ethanol for 1 min inactivated 3.25 log reduction of SARS-CoV-2 inoculated on lettuce but not on chicken and salmon. ClO2 inactivated up to 2 log reduction of SARS-CoV-2 on foods. Peracetic acid was able to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from all foods. The virucidal effect of all disinfectants used in this study did not differ between the two SARS-CoV-2 strains; therefore, they could also be effective against other SARS-CoV-2 variants. This study demonstrated that the viability of SARS-CoV-2 can be extended at 4 and −40 °C and peracetic acid can inactivate SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Viability, Ethanol, Peracetic acid, Chlorine dioxide, Lettuce, Salmon, Beef

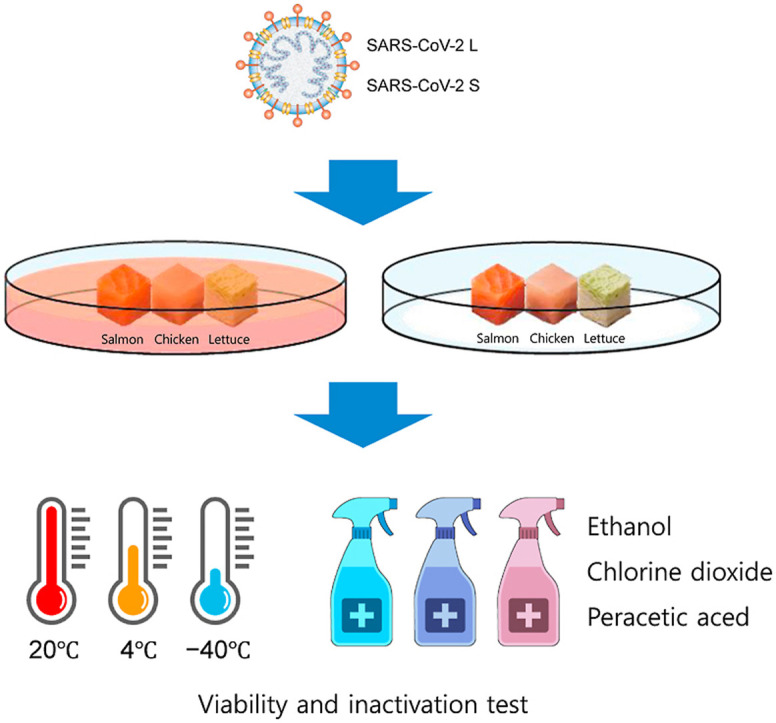

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, which started in 2019, has caused 585 million confirmed cases and 6.42 million deaths by August 10, 2022 (WHO, 2021). Although over 4 billion people have completed vaccination, the pandemic is still ongoing, with the daily number of confirmed cases reaching 1.5 million (Mathieu et al., 2021). Concerns over food safety have been raised since the seafood market in Wuhan was identified as the initial source of SARS-CoV-2. In December 2019, 55% of SARS-CoV-2 infections in China were associated with markets in Wuhan, including the Huanan seafood wholesale market (Bai et al., 2021). In the United States, between April and May 2020, 264 meat and poultry processing facilities in 23 states reported coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreaks, with 17,358 confirmed cases among workers (Birhane et al., 2020). In addition, SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected on the surfaces of various foods and their packaging materials, and it has been reported that some of the outbreaks may be related to frozen imported foods and food packaging materials (Liu et al., 2020; Pang et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020).

As person-to-person, airborne, and contact with contaminated surfaces is spreading virus, foodborne transmission is the important route as well. Virus can be contaminated on food with two main means (Ceylan et al., 2020). The first can occur during the production and manufacture of food, including using contaminated water during harvest processing and infected food handlers. The second is the consumption of animal-derived foods infected with zoonotic viruses. Although SARS-CoV-2 infection by eating contaminated food was not reported, there have been cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in foods related facilities, and up to 1011 copies of RNA have been detected in human excretions, such as sputum from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Wölfel et al., 2020). Nipah virus is a zoonotic respiratory virus closely related to infection by contaminated food, and SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, which are members of SARS-CoV-2, can also be transmitted through food (Cui et al., 2019; WHO, 2018). As such, the foodborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 seems plausible but unproven. However, there are few studies on the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 contaminating foods or how to eliminate it.

Recent studies have raised concerns about food-related transmission or oral infection. Van Doremalen et al. (2020) reported that depending on the surface (except copper), SARS-CoV-2 can remain infectious for up to several days and survives for hours in aerosols. These results suggest the possibility of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 via fomites on contaminated surfaces. In addition, Dai et al. (2021) reported that SARS-CoV-2 contaminating fish could survive up to a week at 4 °C. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and bloody stools caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, have also been reported (Guan et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021). In a case control study of COVID-19 patients in Baltimore, USA, 73% of patients experienced gastrointestinal symptoms (Chen et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 not only caused gastrointestinal symptoms but was also shed in feces. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in feces or rectal swabs in 48% (312/650) of the investigated COVID-19 patients. Of these, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 63.2% (187/296) in fecal/rectal samples but not in respiratory samples (Guo et al., 2021). In addition, SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in fecal/rectal samples had a faster threshold cycle than respiratory samples or shed high titers over a longer period than respiratory samples, where titers decreased over time (Han et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Animal coronaviruses, already well studied, are enterotropic viruses that infect and cause symptoms in the intestinal tract, and associations with the intestinal tract were also observed with the previous novel coronaviruses SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Assiri et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2003; Weiss and Leibowitz, 2011). For SARS-CoV-2 to enter cells, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and transmembrane serine protease 2 are essential, and they are expressed not only in the lungs but also in the ileum and colon (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is also known to be robust under extremely acidic conditions (Chin et al., 2020).

The viability of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrix have been studied little. As the efficacy of sanitizers could be reduced depending on the characteristics of food matrix, the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by disinfectants have been conducted on the various food matrices. SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was detected in the imported frozen food packages and the surface of the frozen foods including salmon, beef, and chicken wings (Bai et al., 2021). Chicken is the world's most consumed meat, and lettuce is one of the main sources of food-borne viruses (CDC, 2021; OECD/FAO, 2021). Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the viability of SARS-CoV-2 according to the storage temperature on experimentally contaminated food matrices and to assess the efficacy of disinfectants in inactivating SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food matrices.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viruses and cells

Vero E6 (ATCC CL-1586) cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco; Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics-antimycotics (Gibco). Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Confluent Vero E6 cells were inoculated with two strains of SARS-CoV-2 (L type, NCCP43326; S type, NCCP43330) at 0.1 multiplicities of infection in DMEM with 2% FBS. SARS-CoV-2 was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 days. After two freeze/thaw cycles, viral titers were assessed using a 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) and quantified using the Spearman–Karber method (Ramakrishnan, 2016). All experiments related to SARS-CoV-2 were performed at the biosafety level 3 facility of the Zoological Infectious Disease Research Institute, Chonbuk National University.

2.2. Viability test on food matrices

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in human excreta is 106–1011 copies, and when converted into infectious particles, it is approximately 102–107 TCID50 (Sender et al., 2021; Wölfel et al., 2020). Therefore, in the present study, the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 to be used for food contamination was determined to be 106 log TCID50/mL. The three food matrices (lettuce, chicken breast, and salmon) used in the viability test were purchased from a market in Anseong, Korea. Viability tests were performed based on a previous study (Dai et al., 2021). Briefly, chicken and salmon were cut into 125 mm3 pieces and lettuce into 1 cm2 pieces, which were then used as food matrices. Thereafter, the food matrices were immersed in SARS-CoV-2 L and S at 6 log TCID50/mL and incubated for 15 s. After removing excess virus using filter paper, food matrices were immediately transferred to an individual 1.5 mL tube. Thereafter, individual contaminated food matrices were maintained at 40% relative humidity (RH) under three temperature conditions (room temperature: 20 °C, refrigerated: 4 °C, and frozen: −40 °C). For each period (room temperature: 0, 8, 24, 48, and 72 h; refrigerated: 0 and 8 h and 2, 3, 7, 10, and 14 d; frozen: 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 d), 1 mL of DMEM with 2% FBS was added to individual tubes and vortexed for 10 s to recover viruses and then filtered using a 0.45-μm filter. Recovered viruses were immediately diluted 10-fold and viral infectivity was determined using TCID50.

2.3. Quantitative carrier test using food matrices

A quantitative carrier test to evaluate the inactivation effect of disinfectants on SARS-CoV-2 contaminated food matrices were performed with modifications to OECD guidelines and previous study. (OECD, 2013; Moon et al., 2021). As disinfectants to be evaluated, chlorine dioxide (ClO2) and peracetic acid (PAA) were selected in consideration of food grade, persistence, and generation of toxic by-products such as trihalomethane (Aieta and Berg, 1986; Farinelli et al., 2022). As ethanol (EtOH) is known to be effective in inactivating SARS-CoV-2 on various surface materials, food-grade ethanol was used in this study (Jung et al., 2023). The two disinfectants except EtOH were used at half of the recommended concentration, the recommended concentration and twice of the recommended concentration. SARS-CoV-2 contaminated food matrices prepared in the same manner as for the viability test were treated with 50 μL of 30, 50, and 70% EtOH (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or 20, 40, and 80 ppm ClO2 (LifeClean, Uddevalla, Sweden) for 1 and 5 min, respectively. In addition, lettuce was treated with 40, 80, and 160 ppm PAA (Daesung C&S, Seoul, Korea), and chicken and salmon were treated with 1,000, 2,000, and 4000 ppm of the same as recommended (MFDS, 2019). After neutralizing the disinfectant by adding 950 μL of 5% FBS DMEM to the food matrices, the neutralized solutions were immediately evaluated for viral infectivity using TCID50.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. To determine virus stability, a Bayesian regression model was used to estimate the decay rate of viable virus titers (Van Doremalen et al., 2020). The posterior samples were drawn using a No-U-Turn Sampler (a form of Markov Chain Monte Carlo). For the quantitative carrier test, a two-sample t-test was used to analyze differences between strains. The disinfection effect between concentrations on viruses was analyzed using one-way ANOVA and the Tukey post-hoc. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.0.

3. Results

3.1. Viability test on food matrices

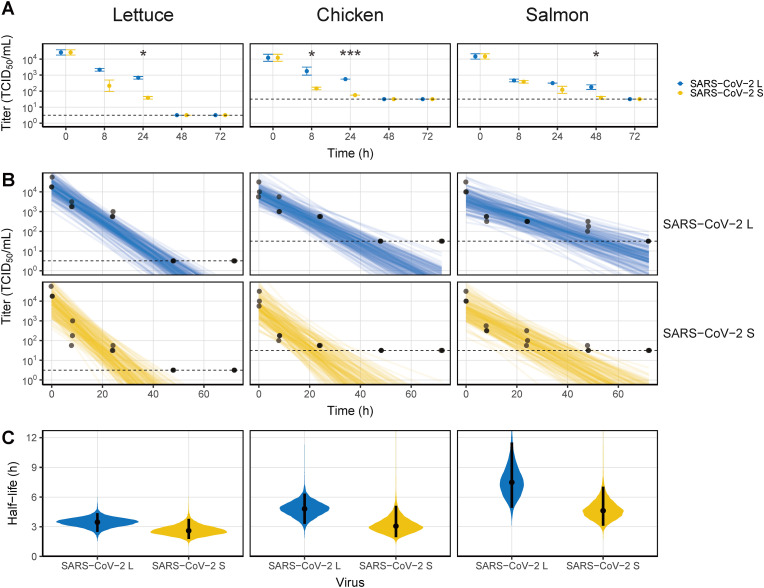

At 20 °C, SARS-CoV-2 did not survive more than 3 days on food matrices (Fig. 1 A). On lettuce, the SARS-CoV-2 titers, which were 3.06 × 104 TCID50/mL after contamination, decreased by more than 1 log TCID50/mL to 7.08 × 102 and 3.98 × 101 TCID50/mL for SARS-CoV-2 L and SARS-CoV-2 S at 24 h, respectively. After 48 h, the titers were below the detection limit. Similar to lettuce, the titers of both SARS-CoV-2 strains on chicken were below the detection limit from 48 h. On salmon, SARS-CoV-2 titers decreased by more than 1 log at 8 h (SARS-CoV-2 L to 4.80 × 102 TCID50/mL and SARS-CoV-2 S to 3.98 × 102 TCID50/mL), which was faster than on lettuce and chicken, but viruses survived longer, up to 48 h. The kinetics of the two SARS-CoV-2 strains on food matrices were somewhat different. On all surfaces, SARS-CoV-2 S was more unstable than SARS-CoV-2 L, and the two strains significantly differed at 24 h on lettuce (p < 0.001), 8 and 24 h on chicken (p = 0.014 and p < 0.001, respectively), and 48 h on salmon (p = 0.016). Virus titers decreased sharply on all food matrices, as indicated by the linear decrease over time (Fig. 1B). The half-life of SARS-CoV-2 differed depending on the food matrix (Fig. 1C and Table S1). The median estimates of half-lives for SARS-CoV-2 L and SARS-CoV-2 S on lettuce were 3.47 and 2.60 h, respectively, and 4.80 and 3.08 h on chicken, respectively, slightly longer than those on lettuce. On the other hand, the median estimate of half-lives on the salmon surface, where infectious virus was detected for up to 2 d, were longest at 7.46 h for SARS-CoV-2 L and 4.65 h for SARS-CoV-2 S.

Fig. 1.

Viability of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices at 20 °C. (A) Virus titer recovered from the surface by timepoint. (B) Bayesian regression plots showing the predicted decay of virus titers over time. The dots are slightly jittered to avoid overlapping. Lines show exponential decay rates and were randomly drawn at 150 per panel from the joint posterior distribution. (C) Violin plot representing the half-life of viruses. The dots represent the median estimates, and the lines are the 95% confidence intervals. The dashed lines in (A) and (B) indicate the limit of detection. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005).

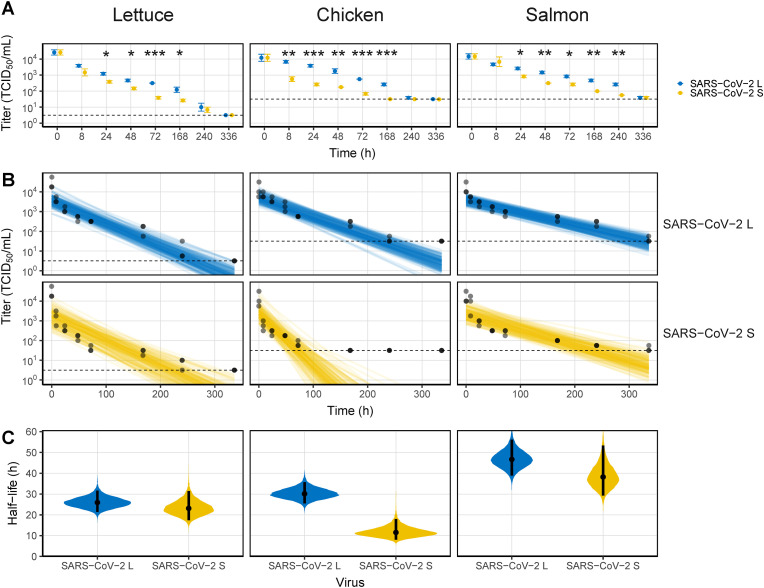

At 4 °C, the viability of the viruses was prolonged to 10 days (Fig. 2 A). The time required for viruses to decrease by 1 log TCID50/mL on lettuce was 24 h, which was the same as that at 20 °C; however, infectious SARS-CoV-2 was detected for up to 10 d. The difference in viability between the two SARS-CoV-2 strains was greatest at 72 h (p < 0.001). The differences between the two SARS-CoV-2 strains were most pronounced on chicken. SARS-CoV-2 L, although in small amounts, maintained the infectivity for up to 10 d (3.98 × 101 TCID50/mL), whereas SARS-CoV-2 S decreased sharply at 8 h (to 6.26 × 102 TCID50/mL) and was not detected from 7 d. The prolongation of the viability of both SARS-CoV-2 strains was particularly pronounced on salmon, where they remained infectious for up to 14 d post contamination. Due to the spoilage of the food samples, the experimental period was limited to 2 weeks. The posterior distribution of the decay model showed that SARS-CoV-L was less scattered than SARS-CoV-2 S (Fig. 2B). The half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was also increased 5–9 fold compared with that at 20 °C, except for that of SARS-CoV-2 S on chicken (Fig. 2C and Table S1). On lettuce, median half-life estimates for SARS-CoV-2 L and SARS-CoV-2 S were 25.90 and 23.20 h, respectively, close to 1 d. However, the median half-life estimate for SARS-CoV-2 L on chicken was increased to 30.1 h, whereas that for SARS-CoV-2 S was only 11.6 h. Similar to the half-life results at 20 °C, the half-lives of SARS-CoV-2 L and SARS-CoV-2 S on salmon were 46.6 and 38.2 h, respectively, longer than on other foods.

Fig. 2.

Viability of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices at 4 °C. (A) Virus titers recovered from the surface by timepoint. (B) Bayesian regression plots showing the predicted decay of virus titers over time. The dots are slightly jittered to avoid overlapping. Lines show exponential decay rates and were randomly drawn at 150 per panel from the joint posterior distribution. (C) Violin plot representing the half-life of viruses. The dots represent the median estimates, and the lines are the 95% confidence intervals. The dashed lines in (A) and (B) indicate the limit of detection. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005).

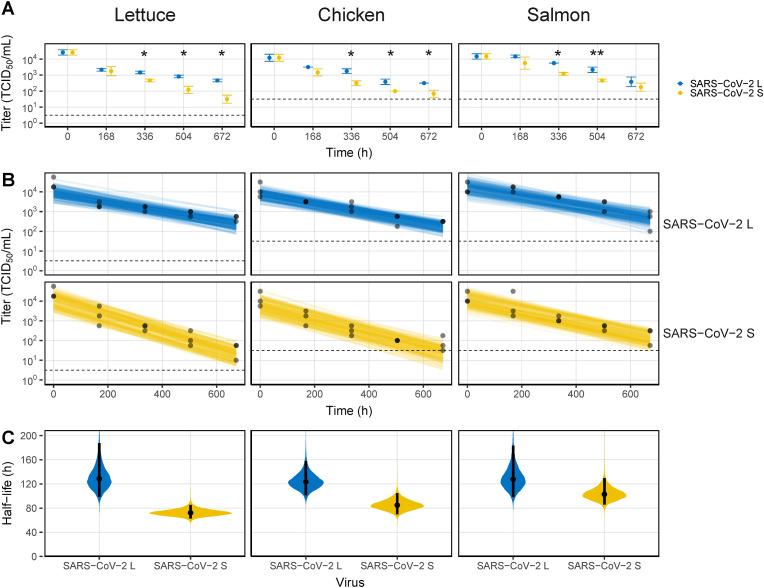

At −40 °C, the SARS-CoV-2 strains were viable for 4 weeks on all food matrices (Fig. 3 A). In particular, SARS-CoV-2 L maintained infectivity of more than 2 log TCID50/mL (4.80 × 102, 3.16 × 102, and 5.54 × 102 TCID50/mL on lettuce, chicken, and salmon, respectively). In addition, the decay model data were smooth on all food matrices until the end of the experiment (Fig. 3B). Accordingly, the half-life of the virus on each surface was significantly increased, but there were differences depending on the strain. (Fig. 3C and Table S1). On the one hand, SARS-CoV-2 L had a half-life greater than 5 d, similar across all foods (129, 123, and 128 h on lettuce, chicken, and salmon, respectively). On the other hand, the half-lives of SARS-CoV-2 S were 72.3, 84.9, and 103 h on lettuce, chicken, and salmon, respectively, up to 56.7 h shorter than those for SARS-CoV-2 L.

Fig. 3.

Viability of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices at −40 °C. (A) Virus titers recovered from the surface by timepoint. (B) Bayesian regression plots showing the predicted decay of virus titers over time. The dots are slightly jittered to avoid overlapping. Lines show exponential decay rates and were randomly drawn at 150 per panel from the joint posterior distribution. (C) Violin plot representing the half-life of viruses. The dots represent the median estimates, and the lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. The dashed lines in (A) and (B) indicate the limit of detection. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005).

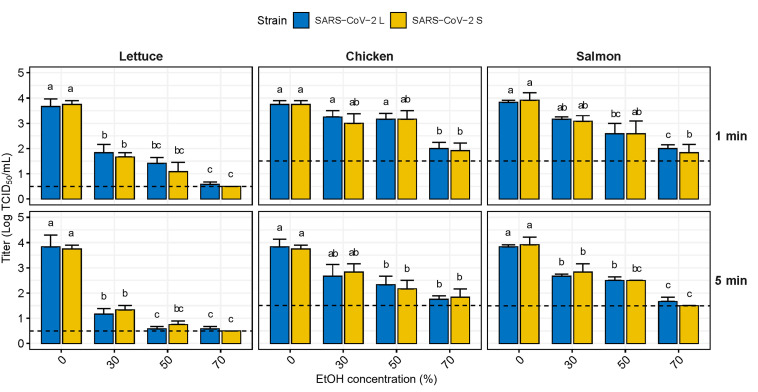

3.2. Virucidal effect of disinfectants on food matrices

According to the OECD guideline criteria, the standard effect of the carrier test is defined as a ≥3 log reduction; nevertheless, no reduction of more than 3 logs was observed in the experiments on chicken and salmon due to the detection limit. Therefore, only ≥2 log reduction was observed in both foods in this study. EtOH effectively reduced the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food, albeit not completely (Fig. 4 ). EtOH exposure for 1 min reduced the SARS-CoV-2 strains on lettuce by 1.96 and 2.45 log TCID50/mL at 30 and 50%, respectively, and achieved a ≥3 log reduction at 70%. On chicken, the SARS-CoV-2 strains were reduced by only 0.63 and 0.58 log TCID50/mL at 30 and 50%, respectively, and did not achieve a 2 log reduction even at 70%. When treated for 5 min, SARS-CoV-2 on lettuce was reduced by more than 3 log TCID50/mL at 50%; nonetheless, SARS-CoV-2 L was not completely inactivated even at 70%, similar to the results for 1 min exposure. Although the amount of infectious SARS-CoV-2 was reduced compared with that for the 1 min exposure, it was still insufficient to reduce SARS-CoV-2 contaminating chicken and salmon. SARS-CoV-2 was reduced by 1.04 and 1.54 log TCID50/mL on chicken and 1.13 and 1.38 log TCID50/mL on salmon at 30 and 50% concentrations, respectively. Treatment with 70% EtOH for 5 min reduced SARS-CoV-2 by > 2 logs on both foods, SARS-CoV-2 S on salmon was completely inactivated, but there was no difference between the strains.

Fig. 4.

Virucidal effect of ethanol against SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food matrices. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection at 0.5 TCID50/mL for lettuce and 1.5 TCID50/mL for chicken and salmon. Lowercase letters indicate significant difference between the disinfectant treated group and the control within the same virus strain (p < 0.05). EtOH, ethanol.

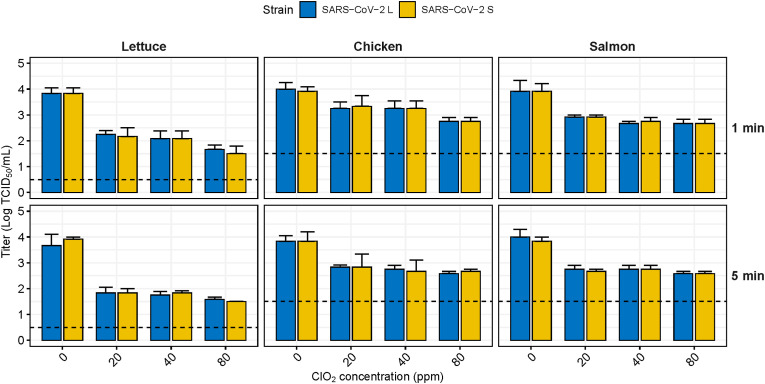

ClO2 has a weaker virucidal effect on SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food than EtOH and did not achieve the standard effect on any food matrix under all exposure time conditions (Fig. 5 ). Although the virucidal effect on SARS-CoV2 contaminating lettuce was superior to that of other foods, it was reduced by only 2.25 log TCID50/mL even at 80 ppm and a 5 min exposure time. Exposure for 1 min showed only a 0.67–1.25 log reduction on chicken and salmon, and the effect was not satisfactory, with a 1.00–1.33 log reduction in 5 min of exposure. Moreover, the virucidal effect of ClO2 did not appear to be concentration or exposure time dependent, and there was no significant difference between the two virus strains.

Fig. 5.

Virucidal effect of sodium hypochlorite against SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food matrices. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection at 0.5 TCID50/mL for lettuce and 1.5 TCID50/mL for chicken and salmon. Lowercase letters indicate significant difference between the disinfectant treated group and the control within the same virus strain (p < 0.05). ClO2, Chlorine dioxide.

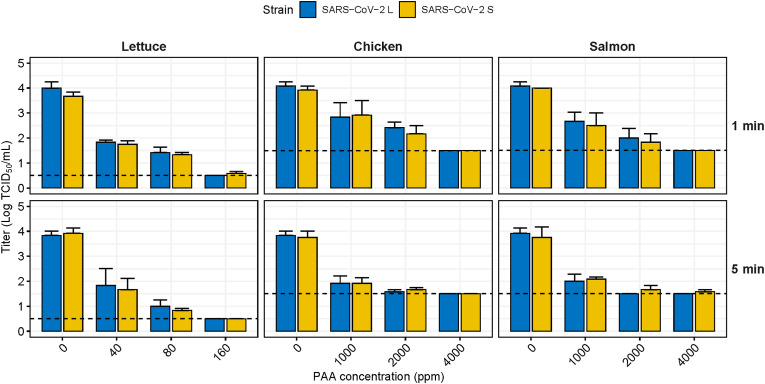

SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food matrices was sensitive to PAA treatment (Fig. 6 ). The virucidal effect of PAA against SARS-CoV-2 contaminating lettuce was significantly reduced by 2.04 and 2.46 logs at 40 and 80 ppm PAA, respectively (p < 0.05), although it did not achieve the standard effect. Treatment with 160 ppm PAA for 1 min completely inactivated SARS-CoV-2 L, although SARS-CoV-2 S remained slightly infectivity (0.58 log TCID50/ml). When lettuce was exposed for 5 min, it showed an approximately 3 log reduction from 80 ppm, and both SARS-CoV-2 strains were completely reduced at 160 ppm. On chicken and salmon, which were minimally affected by EtOH and ClO2, infectious SARS-CoV-2 was no longer detected when PAA was applied at 4000 ppm for 1 min. Exposure for 5 min reduced SARS-CoV-2 above the standard effect (≥2 log reduction) from 2000 ppm. As with other foods, there were no differences between SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Fig. 6.

Virucidal effect of peracetic acid against SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food matrices. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection at 0.5 TCID50/mL for lettuce and 1.5 TCID50/mL for chicken and salmon. Lowercase letters indicate significant difference between the disinfectant treated group and the control within the same virus strain (p < 0.05). PAA, peracetic acid.

4. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory virus that infects the upper respiratory tract and causes respiratory symptoms, such as coughing and sore throat, and has received little attention in terms of food or oral transmission (WHO, 2020). The viability of SARS-CoV-2 was dependent on storage temperature and the contaminated food. At room temperature, SARS-CoV-2 was short-lived on all tested foods, particularly lettuce and chicken. The SARS-CoV-2 contaminated food samples were stored under 40% relative humidity, but the food gradually dried over time. The viability of SARS-CoV-2 may be related to dried food matrices. SARS-CoV-2 is generally less viable on porous than non-porous surfaces (Bueckert et al., 2020). As the food dries, the surface becomes rough, and tends to become more porous (Xiao and Gao, 2012). In particular, SARS-CoV-2 viability was rapidly reduced in cellulose based material, consistent with other enveloped viruses (Bueckert et al., 2020; Chin et al., 2020; Grinchuk et al., 2021; Van Doremalen et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 viability may also be associated with the wettability of surfaces. SARS-CoV-2 survives longer on hydrophobic surfaces, such as plastics and glass, than on hydrophilic surfaces, such as stainless steel (Bueckert et al., 2020; Grinchuk et al., 2021; Van Doremalen et al., 2020). In addition, the high water activity in food makes the virus more sensitive to heat (Bosch et al., 2018). Moreover, contrary to expectations that the viability of the two SARS-CoV-2 strains would be similar, the difference was significant. Genetically, SARS-CoV-2 S is more ancient than SARS-CoV-2 L, but the initial outbreak was responsible for SARS-CoV-2 L, and SARS-CoV-2 S spread more slowly (Awadasseid et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2020). This may have made it easier for SARS-CoV-2 L to spread to humans from contaminated food as it could survive longer on food.

The persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices was inversely proportional to storage temperature. In the present study, the half-life of SARS-CoV-2 increased 8.9 and 37.2 fold at refrigeration and freezing temperatures, respectively, compared with that at room temperature, depending on the surface. Chin et al. (2020) conducted a study on the stability of SARS-CoV-2 suspensions at different temperatures. They reported a 0.7 log decrease at 4 °C for 14 days; however, the decrease became faster with increasing temperature, maintaining stability for 7 d at 22 °C and 2 d at 37 °C. In previous studies by Biryukov et al. evaluating the viability of SARS-CoV-2 on stainless steel, SARS-CoV-2 was inactivated significantly faster at 35 °C than at 24 °C (Biryukov et al., 2020, 2021). In fact, the correlation between temperature and virus viability is not limited to SARS-CoV-2. For instance, in the coronavirus family, which includes animal and human coronavirus, increases in temperature and the time it takes for decimal reduction (1 log reduction in virus infectivity; D-value) are linearly inversely proportional (Guillier et al., 2020). On the other hand, Kratzel et al. (2020a, 2020b) reported that there was no significant difference in the stability of SARS-CoV-2 on a metal surface at 30 °C, room temperature, and at 4 °C. It should be noted that the aforementioned experiments were all conducted at above 0 °C temperatures. In the present study, SARS-CoV-2 persisted for longer in the order of salmon > chicken > lettuce, which seems to be related to food constituents. Although there have been no direct studies on the effect of food constituents on SARS-CoV-2 stability, it can be partially explained by previous studies. The protein and fat content of food increases the stability of viruses under heat treatment. For example, the D-value of a SARS-CoV suspension increased from 1.9 to 5.0 when protein (20% FBS) was added (Rabenau et al., 2005). Moreover, the D-value of the hepatitis A virus in milk composed of 1 and 18% fat doubled from 1.6 to 3.1 (Bozkurt et al., 2015). The protein contents of lettuce, chicken breast, and salmon are 1.4, 31, and 20 g per 100 g, respectively, and the fat contents are 0.2, 3.6, and 13 g, respectively. Although we did not heat treat our food samples, the present study results suggest that protein and fat content is associated with virus stability. In particular, it seems that fat content affects the stability of SARS-CoV-2 surrounded by a lipid envelope more than protein content.

PAA inactivated SARS-CoV-2 stains effectively on any of three food matrices. Although its mechanism for inactivating bacteria or viruses is not entirely understood, PAA is a highly effective biocide used in various fields, including wastewater and clinical and food industries (Rutala and Weber, 2008). PAA is a potent oxidizing agent speculated to denature proteins, disrupt cell wall permeability, and oxidize sulfhydryl and sulfur bonds of proteins, enzymes, and other metabolites (Finnegan et al., 2010). The Korean Food and Drug Administration recommends using PAA at 2000 ppm for poultry and 80 ppm for fruits and vegetables (MFDS, 2019), while the FDA recommends using 350, 2,000, and 230 ppm of PAA in fruits and vegetables, poultry, and fish, respectively (FDA, 2017). Since no recommendations have been made for salmon by The Korean Food and Drug Administration, the recommendations for poultry were applied for salmon in the present study. PAA inactivated most SARS-CoV-2 when applied at the recommended concentration for 5 min; however, the recommended concentration was insufficient to completely inactivate the virus. Given the potential for SARS-CoV-2 transmission by imported salmon, it may be necessary to consider adjusting the recommended PAA concentrations for fish. Overall, PAA is a suitable disinfectant for food safety as it inactivates gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, molds, and yeasts in less than 5 min at <100 ppm and is also effective against non-enveloped viruses, such as poliovirus and adenovirus, at > 400 ppm (Becker et al., 2017; Rutala and Weber, 2015).

Although not recommended for direct use in food, ethanol effectively removed SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food. Ethanol inactivates bacteria by coagulating or denaturing proteins and enzymes in the cell wall, cell membrane, and cytoplasm of bacteria (Huffer et al., 2011). The action of ethanol in enveloped viruses is not clearly understood, but it is assumed to be similar to that in bacteria and is generally effective (Dev Kumar et al., 2020). Alcohol-based disinfectants were effective against SARS-CoV-2 in suspension as it was completely inactivated with only 30% ethanol and 2-isopropanol applied for 30 s (Kratzel et al., 2020a, 2020b). In the present study, virus-contaminated lettuce was effectively treated in 70% ethanol for 1 min, but for chicken and salmon, this treatment was insufficient. The virucidal effect of ethanol was lower in food with higher protein content, suggesting that the protein denaturation and coagulation action of ethanol may be competitive between the virus and food matrix.

Chlorine-based disinfectants, especially sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), are most widely used on water and food contact surfaces. However, the effect of NaClO on coronbib_kratzel_et_al_2020bavirus is ambiguous. Exposure to 600 ppm NaClO for 1 min reduced the infectivity of animal coronavirus by less than 1 log, significantly lower than that of 70% ethanol, which reduced infectivity by > 3 logs (Hulkower et al., 2011). Although there are differences depending on the type of coronavirus, NaClO concentrations above 1000 ppm were required to observe a 3 log reduction in infectivity, which is too high for food applications (Kampf et al., 2020). ClO2 is a chlorine-based disinfectant that acts as an oxidizing agent similar to NaClO; however, ClO2 has better oxidation ability because it can accept five electrons, whereas NaClO can only accept two electrons (Warf, 2019). Moreover, the solubility of chlorine per molar weight in ClO2 is 263%, which is remarkably higher than that in NaClO at 95.2%. Therefore, the present study attempted to remove SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food using ClO2, which was expected to be more effective. However, even under conditions of the highest concentration and exposure time used in the experiment, SARS-CoV-2 decreased by only 2 logs on lettuce and 1 log on chicken and salmon. Wang et al. (2005) reported that SARS-CoV contaminating wastewater was completely inactivated by treatment with 40 ppm ClO2 for 5 min. It seems that the action of ClO2 was also affected by food constituents similar to the EtOH treatment. To reuse processed water for fresh products, it is necessary to prevent cross contamination of pathogens that can threaten food safety and remove organic compounds that encourage microorganism growth (Meneses et al., 2017). However, these organic compounds rapidly deplete free chlorine, inducing a high chlorine demand (CLD). According to a study by Teng et al. (2018), the factors that increased CLD in cabbage wash water included proteins, phenols, organic acids, and sugars, and among them, protein contributed the most to the increase in CLD. Similarly, chicken and salmon are high in protein, which may have increased the chlorine demand to inactivate the SARS-CoV-2.

The results of this study clearly show how well SARS-CoV-2 can survive on different foods. However, it is still unknown whether infection is caused by ingesting food contaminated with SARS-CoV-2. In addition, although SARS-CoV-2 can survive for a long time at low pH, which has been well documented in intestinal infections, there is no direct study on whether it can tolerate the intestinal environment (e.g., bile salt and various digestive enzymes). Therefore, future studies should evaluate the viability of SARS-CoV-2 in a mimicked intestinal environment. In addition, this study presented methods to effectively remove SARS-CoV-2 contaminating food; however, this should be sufficiently studied using food applicable disinfectants, such as ozonated water.

5. Conclusions

While the viability of SARS-CoV-2 can be maintained in refrigeration and freezing condition, SARS-CoV-2 was rapidly inactivated in food matrices at room temperature. Therefore, the potential for food-borne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 appears to be low, consistent with the FDA opinion. Among the variant strains, SARS-CoV-2 L survived more than SARS-CoV-2 S on the food matrices. When PAA is used two times higher than recommended concentration, SARS-CoV-2 L and S strain can be completely inactivated. Treating food with such an effective disinfectant minimizes the threat of SARS-CoV-2 even in group meals, such as in schools and medical facilities. However, chlorine-based disinfectants are insufficient to inactivate SARS-CoV-2 on food matrices.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant (20162MFDS039) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2020. Seoyoung Woo was supported by the Chung-Ang University Graduate Research Scholarship in 2021.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fm.2022.104164.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aieta E.M., Berg J.D. A review of chlorine dioxide in drinking water treatment. J. Am. WATER Work. Assoc. 1986;78:62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Al-Rabiah F.A., Al-Hajjar S., Al-Barrak A., Flemban H., Al-Nassir W.N., Balkhy H.H., Al-Hakeem R.F. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA . 2017. Environmental Assessment for Food Contact Notification FCN 1867.https://www.fda.gov/media/114385/download Accessed 16 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Awadasseid A., Wu Y., Tanaka Y., Zhang W. SARS-CoV-2 variants evolved during the early stage of the pandemic and effects of mutations on adaptation in Wuhan populations. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021;17:97–106. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.47827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Wang Y., Wang Y., Wu Y., Li N., Liu Z. Controlling COVID-19 transmission due to contaminated imported frozen food and food packaging. Chin. CDC Wkly. 2021;3:30–33. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B., Brill F.H., Todt D., Steinmann E., Lenz J., Paulmann D., Bischoff B., Steinmann J. Virucidal efficacy of peracetic acid for instrument disinfection. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2017;6:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-017-0271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birhane M., Bressler S., Chang G., Clark T., Dorough L., Fischer M., Watkins L., Goldstein J.M., Kugeler K., Langley G., Lecy K., Martin S., Medalla F., Mitruka K., Nolen L., Sadigh K., Spratling R., Thompson G., Trujillo A. Update: COVID-19 among workers in meat and poultry processing facilities―United States, April–May 2020. MMWR (Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.) 2020;69:887. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6927e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukov J., Boydston J.A., Dunning R.A., Yeager J.J., Wood S., Reese A.L., Ferris A., Miller D., Weaver W., Zeitouni N.E. Increasing temperature and relative humidity accelerates inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces. mSphere. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00441-20. e00441-00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukov J., Boydston J.A., Dunning R.A., Yeager J.J., Wood S., Ferris A., Miller D., Weaver W., Zeitouni N.E., Freeburger D. SARS-CoV-2 is rapidly inactivated at high temperature. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021;19:1773–1777. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch A., Gkogka E., Le Guyader F.S., Loisy-Hamon F., Lee A., Van Lieshout L., Marthi B., Myrmel M., Sansom A., Schultz A.C. Foodborne viruses: detection, risk assessment, and control options in food processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018:110–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.001. 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt H., D'Souza D.H., Davidson P.M. Thermal inactivation of foodborne enteric viruses and their viral surrogates in foods. J. Food Protect. 2015;78:1597–1617. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueckert M., Gupta R., Gupta A., Garg M., Mazumder A. Infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses on dry surfaces: potential for indirect transmission. Materials. 2020;13:5211. doi: 10.3390/ma13225211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC National outbreak reporting system (NORS) dashboard retrieved from. 2021. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/norsdashboard Accessed.

- Ceylan Z., Meral R., Cetinkaya T. Relevance of SARS-CoV-2 in food safety and food hygiene: potential preventive measures, suggestions and nanotechnological approaches. Indian J. Virol. 2020;31:154–160. doi: 10.1007/s13337-020-00611-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Agarwal A., Ravindran N., To C., Zhang T., Thuluvath P.J. Are gastrointestinal symptoms specific for coronavirus 2019 infection? A prospective case-control study from the United States. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1161–1163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W., Chu J.T., Perera M.R., Hui K.P., Yen H.-L., Chan M.C., Peiris M., Poon L.L. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microb. 2020;1:e10. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Li H., Yan N., Huang J., Zhao L., Xu S., Wu J., Jiang S., Pan C., Liao M. Long-term survival of SARS-CoV-2 on salmon as a source for international transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223:537–539. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev Kumar G., Mishra A., Dunn L., Townsend A., Oguadinma I.C., Bright K.R., Gerba C.P. Biocides and novel antimicrobial agents for the mitigation of coronaviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinelli G., Coha M., Vione D., Minella M., Tiraferri A. Formation of halogenated byproducts upon water treatment with peracetic acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:5123–5131. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c06118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan M., Linley E., Denyer S.P., McDonnell G., Simons C., Maillard J.-Y. Mode of action of hydrogen peroxide and other oxidizing agents: differences between liquid and gas forms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:2108–2115. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinchuk P.S., Fisenko K.I., Fisenko S.P., Danilova-Tretiak S.M. Isothermal evaporation rate of deposited liquid aerosols and the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus survival. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021;21 [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.-j., Ni Z.-y., Hu Y., Liang W.-h., Ou C.-q., He J.-x., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.-l., Hui D.S.C., Du B., Li L.-j., Zeng G., Yuen K.-Y., Chen R.-c., Tang C.-l., Wang T., Chen P.-y., Xiang J., Li S.-y., Wang J.-l., Liang Z.-j., Peng Y.-x., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.-h., Peng P., Wang J.-m., Liu J.-y., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z.-j., Qiu S.-q., Luo J., Ye C.-j., Zhu S.-y., Zhong N.-s. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillier L., Martin-Latil S., Chaix E., Thébault A., Pavio N., Le Poder S., Batéjat C., Biot F., Koch L., Schaffner D.W. Modeling the inactivation of viruses from the Coronaviridae family in response to temperature and relative humidity in suspensions or on surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01244-20. e01244-01220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., Tao W., Flavell R.A., Zhu S. Potential intestinal infection and faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:269–283. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.S., Seong M.-W., Kim N., Shin S., Cho S.I., Park H., Kim T.S., Park S.S., Choi E.H. Viral RNA load in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic children with COVID-19, Seoul, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:2497–2499. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffer S., Clark M.E., Ning J.C., Blanch H.W., Clark D.S. Role of alcohols in growth, lipid composition, and membrane fluidity of yeasts, bacteria, and archaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:6400–6408. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00694-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulkower R.L., Casanova L.M., Rutala W.A., Weber D.J., Sobsey M.D. Inactivation of surrogate coronaviruses on hard surfaces by health care germicides. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2011;39:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S., Kim D.H., Ahn H.S., Go H.J., Wang Z., Yeo D., Woo S., Seo Y., Hossain M.I., Choi I.-S., Ha S.-D., Choi C. Stability and inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 on food contact surfaces. Food Control. 2023;143 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G., Todt D., Pfaender S., Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020;104:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzel A., Steiner S., Todt D., V'Kovski P., Brueggemann Y., Steinmann J., Steinmann E., Thiel V., Pfaender S. Temperature-dependent surface stability of SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 2020;81:452–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzel A., Todt D., V'Kovski P., Steiner S., Gultom M., Thao T.T.N., Ebert N., Holwerda M., Steinmann J., Niemeyer D., Dijkman R., Kampf G., Drosten C., Steinmann E., Thiel V., Pfaender S. Inactivation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 by WHO-recommended hand rub formulations and alcohols. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1592–1595. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung W.K., To K.-f., Chan P.K., Chan H.L., Wu A.K., Lee N., Yuen K.Y., Sung J.J. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Yang M., Zhao X., Guo Y., Wang L., Zhang J., Lei W., Han W., Jiang F., Liu W.J. Cold-chain transportation in the frozen food industry may have caused a recurrence of COVID-19 cases in destination: successful isolation of SARS-CoV-2 virus from the imported frozen cod package surface. Biosaf. Health. 2020;2:199–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E., Ritchie H., Ortiz-Ospina E., Roser M., Hasell J., Appel C., Giattino C., Rodés-Guirao L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat. Human Behav. 2021;5:947–953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneses Y.E., Stratton J., Flores R.A. Water reconditioning and reuse in the food processing industry: current situation and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017;61:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- MFDS . 2019. Field Guidelines for Disinfectants for Food Use.https://www.mfds.go.kr/docviewer/skin/doc.html?fn=20191018092631428.pdf&rs=/docviewer/result/data0013/33294/1/202203 Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y., Han S., won Son J., Park S.H., Ha S.D. Impact of ultraviolet-C and peroxyacetic acid against murine norovirus on stainless steel and lettuce. Food Control. 2021;130 [Google Scholar]

- OECD . OECD Environmental Health and Safety Publications; 2013. OECD Guidance Document on Quantitative Methods for Evaluating the Activity of Microbicides Used on Hard Non-porous Surfaces - OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/FAO OECD-FAO agricultural outlook. 2021. Retrieved from. Accessed. [DOI]

- Pang X., Ren L., Wu S., Ma W., Yang J., Di L., Li J., Xiao Y., Kang L., Du S. Cold-chain food contamination as the possible origin of COVID-19 resurgence in Beijing. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020;7:1861–1864. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabenau H., Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Preiser W., Doerr H. Stability and inactivation of SARS coronavirus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;194:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00430-004-0219-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan M.A. Determination of 50% endpoint titer using a simple formula. World J. Virol. 2016;5:85–86. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v5.i2.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutala W.A., Weber D.J. 2008. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities.https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/47378 2008. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- Rutala W.A., Weber D.J. Elsevier; 2015. Disinfection, Sterilization, and Control of Hospital Waste, Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; pp. 3294–3309. 9th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Sender R., Bar-On Y.M., Gleizer S., Bernshtein B., Flamholz A., Phillips R., Milo R. The total number and mass of SARS-CoV-2 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024815118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Wu C., Li X., Song Y., Yao X., Wu X., Duan Y., Zhang H., Wang Y., Qian Z. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020;7:1012–1023. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z., Van Haute S., Zhou B., Hapeman C.J., Millner P.D., Wang Q., Luo Y. Impacts and interactions of organic compounds with chlorine sanitizer in recirculated and reused produce processing water. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N., Tamin A., Harcourt J.L., Thornburg N.J., Gerber S.I. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-W., Li J.-S., Jin M., Zhen B., Kong Q.-X., Song N., Xiao W.-J., Yin J., Wei W., Wang G.-J. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warf C.C. Routledge; 2019. Chlorine Dioxide and the Small Drinking Water System, Providing Safe Drinking Water in Small Systems; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.R., Leibowitz J.L. In: Adv. Virus Res. Maramorosch K., Shatkin A.J., Murphy F.A., editors. . Academic Press; 2011. Chapter 4 - coronavirus pathogenesis; pp. 85–164. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2018. Nipah Virus.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nipah-virus Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Modes of Transmission of Virus Causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC Precaution Recommendations: Scientific Brief; p. 27.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331601/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Transmission_modes-2020.1-eng.pdf March 2020. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2021. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., Niemeyer D., Jones T.C., Vollmar P., Rothe C. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.-W., Gao Z.-J. IntechOpen; 2012. The Application of Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) to Study the Microstructure Changes in the Field of Agricultural Products Drying. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y., Guo Q., Sun X., Zhao D., Shen J. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Kang Z., Gong H., Xu D., Wang J., Li Z., Li Z., Cui X., Xiao J., Zhan J. Digestive system is a potential route of COVID-19: an analysis of single-cell coexpression pattern of key proteins in viral entry process. Gut. 2020;69:1010–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Mao L., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Song Y., Bo Z., Wang H., Wang J., Chen C., Xiao J. vol. 2. China CDC Weekly; 2020. pp. 658–660. (Reemergent Cases of COVID-19—Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China). July 22, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.