Abstract

A faculty position can be a balancing act. Many new faculty, particularly minorities, struggle due to a lack of mentorship. Writing accountability groups (WAGs) offer new faculty an opportunity to glean advice from mentors and improve their writing skills and enhance their career development in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Traditional benefits of WAGs

As faculty, we are constantly writing, whether we are preparing competitive grants to obtain funding for our research or finalizing manuscripts to undergo the long process of peer-review and publication. WAGs, which are structured writing groups that aim to increase writing productivity among a committed group of people, have become increasingly popular, with studies showing that WAG members report increased writing frequency, better time management and organizational skills, and larger numbers of publications and funded grants [1–5]. Importantly, WAGs encourage participants to schedule and protect time for writing (Table 1). For example, this can include three 1 h segments, with each segment given 50 min of protected, uninterrupted time to write and then 10 min for conversation and mentoring [1–9]. At the end of the 10 min conversation, the participants return to writing. These dedicated times can stop procrastination and provide a safe space where minority faculty can feel free to ask questions or for help with their technical writing skills [1–5].

Table 1.

WAG meeting template spanning four meetings in a month

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novice style | Goals: Analyze how you feel about your writing. Improve overall writing skills. |

Goals: Discussion about if you need accountability (list accountability partner and name). |

Goals: Evaluate each other’s writing and discuss areas of improvement. |

Goals: Look at assessment of productivity across the first 3 weeks and redefining goals. |

| Meeting layout: 30 min dedicated to writing, 15 min is reading the writing, and 15 min of group discussion. |

Meeting layout: 30 min dedicated to writing, 15 min is reading the writing, and 15 min of group discussion. |

Meeting layout: 30 min dedicated to writing, 15 min is reading the writing, and 15 min of group discussion. |

Meeting layout: 30 min dedicated to writing, 30 min of group discussion. |

|

| Key considerations: The analysis of the writing should be derived from time. Establishing goals based on goals. |

Key considerations: How can your accountability partner work with you to ensure you meet your desired goals? |

Key considerations: Ensure that weaknesses and strength are clear and constructive. |

Key considerations: In formulating the next weeks of goals, ensure input from the entire group is taken. |

|

| Experienced style | Goals: Analyze how you feel about your writing. Improve overall writing skills. |

Goals: Evaluate the goals that have been completed and the goals which remain uncompleted. |

Goals: Redefining weaknesses and creating a plan of action with accountability partner. |

Goals: Moving goals over from the previous month and reformulating them. |

| Meeting layout: 15 min of conversation/dancing/other methods to create welcoming environment, 45 min to writing. |

Meeting layout: 15 minutes of conversation/dancing/other methods to create welcoming environment, 45 min to writing. |

Meeting layout: 15 min of conversation/dancing/other methods to create welcoming environment, 45 min to writing. |

Meeting layout: 15 min of writing, and 45 min of discussion. |

|

| Key considerations: During the 45 min of writing, this can be further divided. For example, it can alternate between working on grants, manuscripts, and individual development plans. |

Key considerations: Re-evaluate focus and consider ways to calm the mind from overexertion of writing. Techniques such as dancing may help. |

Key considerations: Formulate an actionable plan to mitigate the weakness and use your partner to ensure you are both on track and will stick to your goals. |

Key considerations: Consult other people’s previous ideas and adapt goals to ensure mutual success. |

WAGs are broadly applicable to a range of faculty members and can exist in several forms. When forming a WAG it is important to consider the scope, frequency of meetings, style, and rules to be adapted. As a WAG progresses, these parameters may be adjusted as necessary. Safe WAG environments provide a place for postdocs to get feedback on their job application materials as well as to prepare and practice their talks as they transition to faculty positions. Faculty members, as a result of bringing an authentic self to the group, can test new ideas and form peer-to-peer collaborative networks [6–9]. Many different types of WAG exist, such as formal WAGs, online WAGs, process-oriented WAGs, and online instruction WAGs [1–5], so a wide variety of individuals can participate in them and find one that is tailored to them. WAGs are effective as a gathering for idea sharing, getting thought to paper, and discussing current situations related and nonrelated to academia. For example, it can be a place to share apps that assist with setting goals and task management, including effective delegation to accomplish important tasks.

Benefits – mentoring

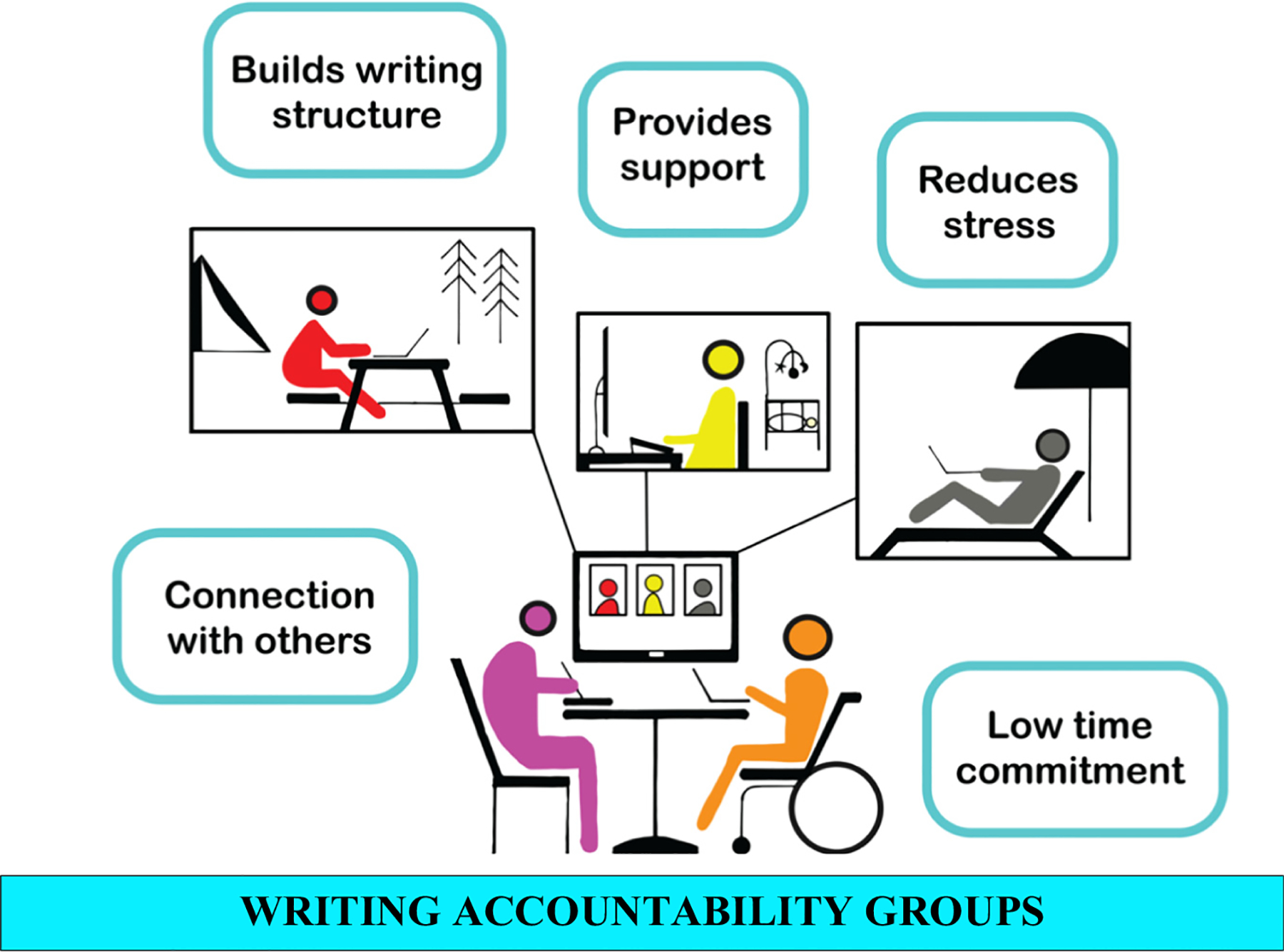

The mentorship gained in WAGs can be pivotal to strengthen faculty productivity and career progression [6–9]. Examples of this mentorship can include peer-to-peer mentoring and group mentoring. In this way, WAGs can be an important resource for anyone in academia who relies on funding and publishing opportunities. Without this particular professional opportunity [1–5], WAG participants could find it more difficult to progress to tenure. Writing accountability groups help to maintain focus, particularly of junior faculty who have many competing and often new responsibilities. Thus, WAGs lead to scholarly progress and allow participants to share their mentoring knowledge while interacting with senior faculty [1–9]. Furthermore, working in WAGs builds self-editing skills and increases the ability to be concise while tailoring writing to target different audiences (Figure 1) [1–5]. WAGs can serve a variety of roles tailored to the individual and can differ for novice and experienced writers (Table 1). While WAGs may commonly be associated with writing productivity [1–5], their benefits go far beyond this.

Figure 1. Varying environments for writing accountability groups (WAGs).

WAGs can be utilized in different environments, individually and in group settings, to strengthen writing skillsets for members including senior principal investigators and junior faculty.

Benefits beyond writing productivity

One WAG faculty member said:

The initial hurdle for me to overcome was to stop talking and start writing. I did not anticipate needing to deal with the uncomfortable space of ‘silence’ during WAG meetings. It was a strange feeling. I initially felt that I should be saying or contributing something and did not immediately recognize that silence is one of the keys to WAG success. I also had a few bad habits that I did not realize were hindering me, such as taking multiple breaks in a short period of time and giving in to distractions like multi-tasking.

WAGs help participants set goals in measured timeframes [1–5]. If goals are not reached, participants can modify their plans resulting in learning new writing strategies [1–5]. Working in a WAG allows participants to practice good time management skills [10], including knowing how long a task might take, identifying deadlines, and time utilization, for example, time spent on-task versus off-task. These skills help participants fine-tune their individual development. With the elevation of virtual communication, WAGs can be held remotely, allowing participants to remain accountable with their writing from anywhere [2,4]. This virtual capacity means that WAGs can have members from different states and countries [2,4,11,12] and build important virtual mentoring networks [7]. It is important to recognize that WAGs are a safe haven and must be treated as such [1,4].

Benefits of minority WAGs

Minority WAGs are groups made up of under-represented faculty in higher education with a central goal of improving writing skillsets and serving as a collaborative and supportive network. Given the barriers that exist for minority faculty, new faculty may consider joining a minority WAG. For example, one new Black faculty member stated that joining a minority WAG provided support and encouragement that did not exist in other faculty groups for them [1–5]. Having common shared experiences allows minority WAG members to identify, address, and conquer barriers [1–5]. Furthermore, writing with senior and more naturally skilled writers can offer junior faculty the opportunity to learn useful strategies to enhance their writing skills. As one gradually acquires new and better writing habits, and enjoys small successes by engaging in a supportive group, it may facilitate a state of clear thinking in a nonstressful writing environment. Ultimately, the goal of WAGS is to promote writing by removing stress and gaining confidence. Another benefit of a WAG is to create a judgment-free environment for all levels of writers, where individuals do not feel like they will be judged about their language and syntax, given the diverse makeup and backgrounds of minorities WAGs [1–5]. Ultimately, WAGs are important especially for minorities because they reduce stress [13] as minorities are able to say ‘no’ more easily [14] as they focus on writing and attaining grants (Table 1).

Community support is another common benefit experienced by WAG members [1–5]. The initial minutes of goal-setting during WAG meetings (Table 1) can serve as informal community therapy sessions that, at times, are more beneficial than the writing itself and may allow participants to write with greater ease [1–5]. We recommend that meetings be under 120 min, with time set aside to celebrate members’ successes, thus avoiding burnout. Benefits also occur because WAGs are great places to share resources on teaching, class assignments, conferences, grant opportunities, and research collaborations. For minority participants, meeting other under-represented WAG members, and hearing that they share some of the same struggles, can be therapeutic. Learning how others use coping mechanisms, and hearing their suggestions for dealing with similar issues, helps to build a sense of community. This shared community empowers individuals to dream bigger, set loftier goals, sharpen their wit, and make it easier to put thought to paper.

Writing in ‘nonjudgmental zones’ allows participants to write more and to put more information down on paper and focus on structure later, instead of trying to get each sentence perfect before moving on, which can hinder progress [1–5]. Writing in a psychologically safe zone, like minority WAG meetings, frees one’s creativity, increases focus, and allows for innovative thoughts [5]. One minority faculty member commented that their WAG has also become a safe space where solutions are created through group efforts by receiving invaluable feedback in a supportive environment.

An important benefit of minority WAGs is the validation that is given and received during meetings, helping to strengthen a sense of well-being, thus increasing productivity [1–5]. Writing from the standpoint of knowing that your work environment includes negative stereotypes, a lack of support, implicit biases, and marginalization, attributes to the already difficult process of writing by making it even more burdensome.

When forming the composition of a WAG, it is important to include varying levels of faculty, have a diverse group, and create clear guidelines that accomplish goals. A diverse group will add to the richness and perspective-taking that is essential for the success of WAGs. Past research has found that WAGs both alleviate feelings of guilt towards a lack of grant funding and increase the average daily writing time of participants [5], likely resulting in increased funding attainment in the future.

For example, approximately half of WAG participants in a minority WAG, run by the American Society of Cell Biology, obtained funding from a major external funding source (e.g., NIH, NSF) [15]. Future studies may consider grant success rates of WAGs against non-WAG members, as well as examining how composition and rules of the group modify the success of members of the group.

In summary, WAGs motivate participants to schedule protected time to increase scholarly activity in a supportive environment [1–5]. Importantly, WAGs allow members to assess their activities while effectively managing their time with others (Figure 1). Beyond the intentional writing productivity benefits, these groups provide positive and uplifting feedback resulting in a creative and encouraging safe zone.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Heather K. Beasley and Neng Vue for helping make the figure in BioRender. We also thank Elge Stevens, and Dr Zer Vue with editing and formatting the paper. Special thanks to Dr Haysetta Shuler for her invaluable editorial and writing contributions to this paper.

This work was supported by the UNCF/BMS EE Just Postgraduate Fellowship, Burroughs Wellcome Fund CASI Award, Burroughs Wellcome Fund Ad-hoc Award, NIH SRP Subaward to #5R25HL106365-12 from the NIH PRIDE Program, DK020593, Vanderbilt Diabetes and Research Training Center for DRTC Alzheimer’s Disease Pilot & Feasibility Program, UNCF/BMS EE Just Faculty Fund Grant awarded to A.H.J.; NSF grant MCB #2011577I and NIH T32 5T32GM133353 to S.A.M.; K01HL153210 to K.L.R.; Postdoctoral Enrichment Award, Burroughs Wellcome Fund to D.J.M. NIH SRP Subaward to #5R25HL106365-12 from the NIH PRIDE Program to S.L.C.

IRB Number: Promoting Engagement in science for underrepresented Ethnic and Racial minorities (P.E.E.R), 21-MortonD-HSR-SOM-01, Kaiser Foundation Research Institute FWA: FWA00002344.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Breitenstein SM (2021) Why and how to start a writing accountability group. Nurse Author Ed. 31, 54–57 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown NR (2021) Using structured writing communities to facilitate undergraduate research writing. Commun. Teach 34, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai PR et al. (2019) Faculty member writing groups support productivity. Clin. Teach 16, 565–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thpe RJ Jr et al. (2020) Writing accountability groups are a tool for academic success: The obesity health disparities pride program. Ethn. Dis 30, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skarupski KA and Foucher KC (2018) Writing accountability groups (WAGs): A tool to help junior faculty members build sustainable writing habits. J. Fac. Dev 32, 47–54 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hion AO Jr et al. (2020) Mentoring minority trainees: Minorities in academia face specific challenges that mentors should address to instill confidence. EMBO Rep. 21, e51269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Termini CM et al. (2021) Building diverse mentoring networks that transcend boundaries in cancer research. Trends Cancer 7, 385–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shuler H et al. (2021) Intentional mentoring: maximizing the impact of underrepresented future scientists in the 21st century. Pathog. Dis 79, ftab038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Termini CM et al. (2021) Mentoring during uncertain times. Trends Biochem. Sci 46, 345–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray SA et al. (2022) Time management for STEMM students during the continuing pandemic. Trends Biochem. Sci 47, 279–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C-L (2021) Impact of nurse practitioners and nursing education on COVID-19 pandemics: Innovative strategies of authentic technology-integrated clinical simulation. Hu Li Za Zhi 68, 4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barroga E and Mitoma H (2019) Improving scientific writing skills and publishing capacity by developing university-based editing system and writing programs. J. Korean Med. Sci 34, e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolle T et al. (2021) Toxic stress and burnout: John Henryism and social dominance in the laboratory and STEM workforce. Pathog. Dis 79, ftab041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinton AO et al. (2020) The power of saying no. EMBO Rep. 21, e50918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segarra VA et al. (2020) Scientific societies advancing STEM workforce diversity: lessons and outcomes from the Minorities Affairs Committee of the American Society for Cell Biology. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ 21, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]