Abstract

The variable 56-kDa major outer membrane protein of Orientia tsutsugamushi is the immunodominant antigen in human scrub typhus infections. The gene encoding this protein from Karp strain was cloned into the expression vector pET11a. The recombinant protein (r56) was expressed as a truncated nonfusion protein (amino acids 80 to 456 of the open reading frame) which formed an inclusion body when expressed in Escherichia coli BL21. Refolded r56 was purified and compared to purified whole-cell lysate of the Karp strain of O. tsutsugamushi by immunoglobulin G (IgG) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for reactivity with rabbit sera prepared against eight antigenic prototypes of O. tsutsugamushi as well as several other species of Rickettsiales and nonrickettsial antigens. Refolded r56 exhibited broad reactivity with the rabbit antisera against the Orientia prototypes, and the ELISA reactions with the r56 and Karp whole-cell lysate antigens correlated well (r = 0.81, n = 22, sensitivity compared to that of standard ELISA of 91%). Refolded r56 did not react with most antisera against other rickettsial species or control antigens (specificity = 92%, n = 13) using a positive cutoff value determined with eight uninfected rabbit sera. Refolded r56 was evaluated further by ELISA, using 128 sera obtained from patients with suspected scrub typhus from Korat, Thailand, and 74 serum specimens from healthy Thai soldiers. By using the indirect immunoperoxidase assay as the reference assay, the recombinant antigen exhibited a sensitivity and specificity of 93% or greater for detection of both IgG and IgM in the ELISA at 1:400 serum dilution. These results strongly suggest that purified r56 is a suitable candidate for replacing the density gradient-purified, rickettsia-derived, whole-cell antigen currently used in the commercial dipstick assay available in the United States.

Scrub typhus or tsutsugamushi disease is an acute, febrile disease caused by infection with Orientia (formerly Rickettsia) tsutsugamushi (40). It accounts for up to 23% of all febrile episodes in areas of endemicity in the Asia-Pacific region (5). The incidence of disease has increased in some countries during the past several years (7).

O. tsutsugamushi is a gram-negative bacterium, but in contrast to other gram-negative bacteria, O. tsutsugamushi has neither lipopolysaccharide nor a peptidoglycan layer (1) and the ultrastructure of its cell wall differs significantly from those of its closest relatives, the typhus and spotted fever group species in the genus Rickettsia (33). Orientia isolates are highly variable in their antigenic properties (13, 23, 29, 32, 43). The major surface protein antigen of O. tsutsugamushi is the variable 56-kDa protein which accounts for 10 to 15% of its total protein (16, 27). Many serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies to Orientia react with homologs of the 56-kDa protein (16, 24, 25, 43). Sera from most patients with scrub typhus recognize this protein, suggesting that it is a good candidate for use as a diagnostic antigen (28).

Diagnosis of scrub typhus is generally based on the clinical presentation and the history of a patient. However, differentiating scrub typhus from other acute febrile illnesses, such as leptospirosis, murine typhus, malaria, dengue fever, and viral hemorrhagic fevers, can be difficult because of the similarities in signs and symptoms. Highly sensitive PCR methods have made it possible to detect O. tsutsugamushi at the onset of illness when antibody titers are not high enough to be detected (14, 19, 36). PCR amplification of the 56-kDa protein gene has been demonstrated to be a reliable diagnostic method for scrub typhus (14, 18). Furthermore, different genotypes associated with different Orientia serotypes could be identified by analysis of variable regions of this gene without isolation of the organism (12, 14, 17, 18, 25, 39). However, gene amplification requires sophisticated instrumentation and reagents generally not available in most rural medical facilities. Current serodiagnostic assays, such as the indirect immunoperoxidase (IIP) assay and the indirect immunofluorescent-antibody or microimmunofluorescent-antibody (MIF) assays, require the propagation of rickettsiae in infected yolk sacs of embryonated chicken eggs or antibiotic-free cell cultures (4, 20, 30, 37, 44). At the present time, the only commercially available dot blot immunologic assay kits (Dip-S-Ticks; Integrated Diagnostics, Baltimore, Md.) requires tissue culture-grown, Renografin density gradient-purified, whole-cell antigen (42). However, only a few specialized laboratories have the ability to culture and purify O. tsutsugamushi, since this requires biosafety level 3 facilities and practices. The availability of recombinant rickettsial protein antigens which can be produced and purified in large amounts and have sensitivities and specificities similar to those of rickettsia-derived antigens would greatly reduce the cost, transport, and reproducibility problems presently associated with diagnostic tests which require the growth and purification of rickettsiae.

Recently, a recombinant 56-kDa protein from Boryong strain fused with maltose binding protein was shown to be suitable for diagnosis of scrub typhus in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and passive hemagglutination test (21, 22). In this report, we describe the molecular cloning, expression, purification, and refolding of a truncated nonfusion 56-kDa protein from Karp strain (r56). Hyperimmune rabbit sera against eight antigenic prototype strains of O. tsutsugamushi as well as antisera against other species of Rickettsiales were used to characterize the specificity and sensitivity of r56 in an ELISA for scrub typhus. Folded r56 was compared with purified whole-cell lysate of O. tsutsugamushi in our standard ELISA for diagnosis of scrub typhus (11). Finally, the diagnostic potential of this r56 preparation was evaluated by ELISA for detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM in 202 sera from healthy Thai soldiers and from febrile patients suspected to have scrub typhus. The results employing refolded r56 were compared to a standard indirect immunoperoxidase test for sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of scrub typhus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and vectors.

Escherichia coli HB101 was used for cloning, and E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for overexpression of proteins under the control of phage T7 lac promoter (35). The plasmid vector used was pET11a (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). Plaque-purified O. tsutsugamushi Karp strain grown in irradiated L929 cells was used for preparation of the genomic DNA (18).

Cloning of the gene for the r56 protein into the expression vector pET11a.

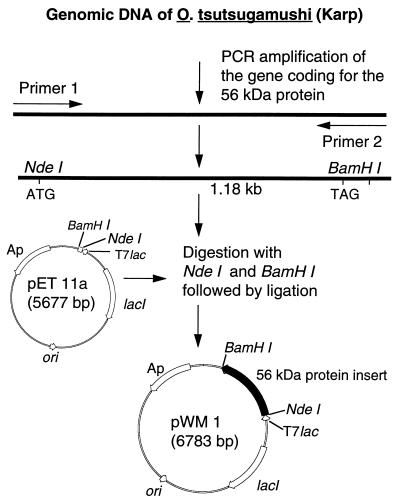

A primer pair [56F(226/261) (5′-TTGGCTGCACATATGACAATCGCTCCAGGATTTAGA-3′) and 56R(1410/1363) (5′-CTTTCTAGAAGTATAAGCTAACCCGGATCCAACACCAGCCTATATTGA-3′)] was designed by using the nucleotide sequence of the open reading frame for the 56-kDa protein from strain Karp (34). The restriction sites for NdeI and BamHI are underlined, and the new initiation codon (in bold type) and reverse complement of the new stop codon (in bold italic type) are shown. The forward primer 56F(226/261) contained the methionine initiation codon at residue 80, which is part of the NdeI recognition sequence. The reverse primer 56R(1410/1363) mutated the tyrosine codon at residue 457 to a stop codon and contained a BamHI site. The coding sequence from amino acids 80 to 456 was amplified by PCR from DNA isolated from O. tsutsugamushi Karp strain. The truncated 56-kDa gene was amplified in a mixture of 400 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 mM (each) primer, 1.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.3) supplemented with 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM KCl. The PCR was started with 15 s at 80°C and 4 min at 94°C and followed by 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 57°C, and 2 min at 72°C. A final step of 7 min at 72°C was added to the last cycle. The amplified fragment (1.18 kb) was digested with NdeI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) and BamHI (GIBCO-BRL Life Technology, Gaithersburg, Md.) and ligated with the doubly digested expression vector pET11a (Fig. 1). E. coli HB101 was transformed with the ligation mixture, and colonies were screened for inserts with the right size and orientation.

FIG. 1.

Strategy for cloning and construction of pWM1 which expresses the truncated recombinant 56-kDa protein antigen from the Karp strain of O. tsutsugamushi.

Expression and purification of the 56-kDa protein.

Plasmids carrying the insert were transformed into the expression host E. coli BL21. The optimum time and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) concentration for inducing r56 expression were determined. Recombinant E. coli expressing r56 were propagated overnight in 2× YT (16 g of Bacto Tryptone, 10 g of Bacto Yeast Extract, and 5 g of NaCl per liter of distilled water [pH 7.0]) at 37°C with shaking. Cell pellets from 100-ml cultures were resuspended in 3 ml of buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) containing 5 mM EDTA and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Ultrasonic disruption of the cell was performed by using setting 3 on a Sonicator Ultrasonic Liquid Processor model XL2020 with a standard tapered microtip (Heat Systems, Inc., Farmingdale, N.Y.) six times for 20 s each time, with cooling on ice for 1 min between each sonication. Disrupted cell extract was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min. The pellets were vortexed to a homogeneous suspension with 2 M urea in buffer A, placed on a shaker at room temperature for an additional 10 min, and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm in an Eppendorf centrifuge (model 5415). The entire process was then repeated with 4 M urea in buffer A. Finally, the pellets were dissolved in 8 M urea in buffer A and applied to a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) ion-exchange (DEAE 5PW) column (Waters Associates, Milford, Mass.) (0.75 by 7.5 cm) for fractionation. Proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of buffer B (6 M urea in buffer A) and buffer C (6 M urea and 2 M NaCl in buffer A) from 0.0 to 0.4 M NaCl over 30 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Fractions were collected at 1 min per fraction. For a typical run, approximately 200 μl of extract obtained from a 10-ml culture was loaded onto the column (see Fig. 2). The presence of r56 in fractions was detected by dot blot immunoassay. Positive fractions with significant amounts of protein were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting.

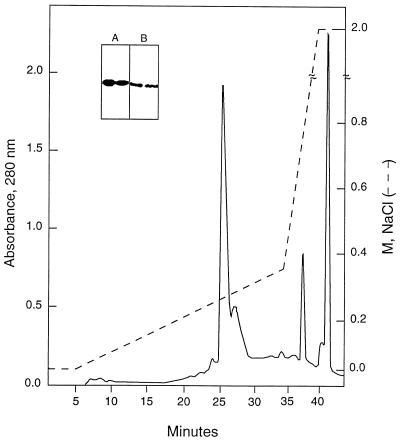

FIG. 2.

HPLC ion-exchange profile for the purification of r56. Inclusion bodies extracted with 4 M urea were dissolved in 8 M urea in buffer A (buffer B) and applied to an HPLC ion-exchange (DEAE) column for fractionation. The extract was fractionated as described in Materials and Methods. The insert shows the Coomassie blue staining (A) and Western blot analysis (B) of the two peak fractions at 25 (left lanes) and 27 min (right lanes) which contain most of the r56.

Dot blot immunoassay.

A 2-μl sample of each eluted fraction was diluted into 200 μl of water and applied to a well of a 96-well dot blotter (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, N.H.). After drying under vacuum for 5 min, the nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 30 min, then incubated with monoclonal antibody Kp56c specific for Karp 56-kDa protein antigen for 1 h, washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min each time, and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chains) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) for 30 min. After the membrane was washed with PBS five times for 5 min each time, substrate solution containing a 5:5:1 ratio of TMB (tetramethylbenzidine) peroxidase substrate, hydrogen peroxide solution, and TMB membrane enhancer (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added to the nitrocellulose membrane. The enzymatic reaction was stopped after 2 min by washing the membrane in distilled water.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

SDS-PAGE analysis was performed with the mini-protein II Dual Slab Cell System (8.2 by 7.2 by 0.75 cm; Bio-Rad). The stacking gel and separation gel contained 4 and 10% acrylamide (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio was 30:1), respectively. Electrophoresis was carried out at constant voltage of 125 V for 75 min. The gels were either stained with Coomassie blue R or electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunodetection of the Western blot was the same as described above for the dot blot immunoassay.

Refolding of r56.

Refolding of r56 in 6 M urea in buffer A was achieved by sequential dialysis with 4 M urea and 2 M urea in buffer A and finally with buffer A only. The peak fractions from the DEAE column containing 0.1 to 0.2 mg of r56 per ml were combined and dialyzed against 6.7 volumes of 4 M urea in buffer A for 30 min at room temperature followed with one change of the dialysis solution and dialyzed for an additional 30 min. The same procedure was repeated with 2 M urea in buffer A. The final dialysis was against buffer A with two initial changes of buffer for 30 min each and finally overnight at 4°C.

CNBr cleavage and amino acid sequence determination on purified r56.

Purified r56 was subjected to CNBr cleavage, and the fragments were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as previously described (8). Three fragments were detected by Coomassie blue staining, and the excised fragments were subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis as previously described (8).

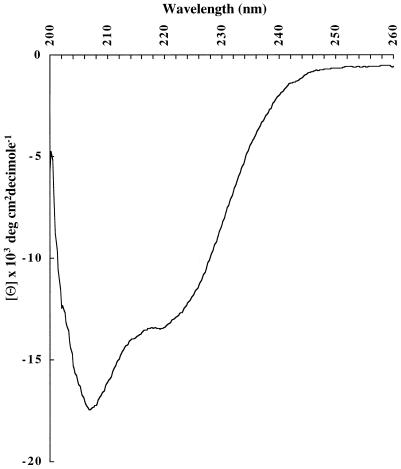

CD spectrum of r56.

The circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of refolded r56 was measured on a JASCO model 715 spectrometer in Ettore Apella’s laboratory at National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. Data were analyzed by Latchezar I. Tsonev, Henry Jackson Foundation, Rockville, Md., at a protein concentration of 117 μg/ml in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 and the calculated molecular mass of 40,903 Da.

Rabbit sera.

Antisera (n = 22) against O. tsutsugamushi Karp (ATCC VR-150) (n = 4), Gilliam (ATCC VR-312) (n = 2), Kato (ATCC VR-609) (n = 4), TA763 (n = 3), TH1817 (n = 4), TA716 (n = 2), TA686 (n = 2), and TA678 (n = 1) were previously described (11, 13, 32). Rabbit antisera against other agents or antigens (n = 13) were prepared by one or more inoculations of the following purified suspensions mixed with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant: Rickettsia rickettsii (n = 2), Rickettsia typhi (ATCC VR-144), Rickettsia conorii (ATCC VR-141) (n = 2), Rickettsia prowazekii (ATCC VR-142), Ehrlichia risticii (ATCC VR-986), Ehrlichia sennetsu (ATCC VR-367), Escherichia coli, murine fibroblast L929 cell (ATCC CCL1 NCTC clone 929), uninfected yolk sac, primary chick embryo cell, and RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC TIB 71). Control sera (n = 8) were either prebleeds or from rabbits in similar lots. The experiments reported herein were conducted according to the principles set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (41a).

Human sera.

Control sera were collected from healthy Royal Thai Army soldiers (38). Patient sera were collected from febrile individuals in Korat, Thailand, from June 1994 to 1995. Onset of fever was as stated by the patient. All individuals identified as positive cases were positive for the presence of Orientia both by PCR amplification of DNA present in acute-phase blood and by recovery of isolates in mice from the same sample (5, 14). This study was conducted in accordance with protocols for human use approved by the Naval Medical Research Institute Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

IIP assay.

The IIP assay was performed as previously described for the detection of antibodies in human serum by using a mixture of O. tsutsugamushi Karp (ATCC VR-150), Gilliam (ATCC VR-312), and Kato (ATCC VR-609) strains propagated in the yolk sacs of embryonated chicken eggs (20, 38, 44).

ELISA.

Microtiter plates (96 well) were coated overnight at 4°C with antigens diluted in PBS, blocked with 0.5% boiled casein for 1 h, and rinsed twice with PBS for 5 min each time. Linbro U plates (catalog no. U 76-311-05; ICN, Costa Mesa, Calif.) were used for assays with rabbit sera, while Microtest III tissue culture plates (Falcon catalog no. 3072) were employed with human sera. Patient sera were diluted 1:400 in PBS with control protein extracts (20 μg/ml) purified from E. coli BL21 by a procedure identical to that used for purifying r56 (fractions collected at 21 to 32 min pooled from gradients equivalent to Fig. 2), preabsorbed for about 1 h at room temperature, and then added to the ELISA plates. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed four times with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG (Fc specific) (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.) diluted 1:8,000 and goat anti-human IgM (mu chain specific) (Kirkegaard & Perry) diluted 1:1,000 were added. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature, the plates were washed four times with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and the last wash was with PBS only before the addition of the 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline sulfonic acid) (ABTS) substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry). Optical densities at 405 nm (OD405) were measured after 15 min of incubation at room temperature. Rabbit sera were diluted 1:250 with PBS only. All procedures were the same as for detection of human antibodies except that rabbit sera were not preabsorbed with protein preparations from BL21 and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry) diluted 1:2,000 was used.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of the recombinant 56-kDa protein.

In order to optimize conditions for the expression of r56, E. coli BL21 transformed with pWM1 (Fig. 1) was propagated at 37°C in medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml to an OD600 of 0.7 to 0.8, induced with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, or 2.0 mM IPTG, and grown further for 4, 6, or 16 h. Although the expression level of r56 increased with the time of incubation, no significant differences were observed in the very high level of expression of r56 with different levels of IPTG or without IPTG under these conditions (data not shown).

In the pET11a expression system, highly expressed recombinant proteins are often produced as inclusion bodies, as was observed here. The inclusion bodies of r56 were serially extracted with 2 and 4 M urea and finally dissolved in 8 M urea and subjected to ion-exchange HPLC. Bound proteins were eluted with a salt gradient in buffer containing 6 M urea. The purification profile is shown in Fig. 2. By dot blot immunoassay, fractions from 21 to 34 min contained r56, while the other fractions were negative. Two major absorbance peaks at min 25 and 27 containing r56 were observed. Both peaks contained r56 with the expected size and similar high level of purity, as judged from the protein staining and Western blotting profiles (Fig. 2, insert). The existence of two peaks with similar protein contents indicated that r56 may exist in different aggregated or partially folded forms. Approximately 10 mg of r56 could be purified from a 1-liter culture.

Refolding and primary and secondary structure of r56.

Peak fractions containing r56 in 6 M urea were pooled and dialyzed sequentially against 4 and 2 M urea each in buffer A and then with buffer A alone. r56 appeared to be properly folded by this process because it remained soluble when no urea was present in the final dialysis. Three CNBr fragments were obtained from purified r56. They were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and following their detection by Coomassie blue staining, three N-terminal amino acid sequences from excised fragments were obtained (amino acids 94 to 111 [YLTNIDAQVEEGKVKADS], amino acids 203 to 218 [VINPILLNIPQGNPNP], and amino acids 338 to 355 [PQQAQQQGQGQQQQAQAT]). The sequences were identical to those deduced from the nucleotide sequence (34), thus confirming the identity and correct expression of the recombinant construct.

The CD spectrum of refolded r56 was also determined (Fig. 3). From the molar ellipticity, the secondary structure was estimated to be 38% α-helix, 13% β-sheet, and 50% random coil (15). Based on the amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence (34), 33% α-helix and 8% β-sheet, and 59% no predicted structure were estimated for the truncated protein (2, 9). Therefore, the structure estimated from the experimental CD data for folded r56 was similar to that predicted for correctly folded, truncated, 56-kDa protein. How close this secondary structure prediction matches that of the native form of 56-kDa protein cannot be evaluated yet because no spectrum for purified rickettsia-derived protein is available.

FIG. 3.

CD spectrum of refolded r56.

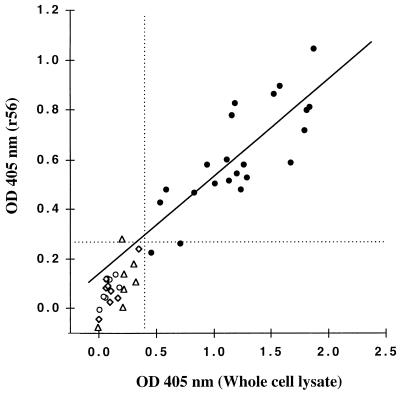

Comparison of the ELISA reactivity of rabbit antisera to r56 and rickettsial whole-cell lysate.

r56 contains only a portion of the 56-kDa protein, the major antigen that is used to differentiate antigenic types of Orientia. Rickettsial whole-cell lysate also contains numerous other protein antigens besides intact 56-kDa antigen. We established positive breakpoints (mean plus 2 standard deviations [SD]) for reactivity of both r56 and whole-cell Orientia lysate (WCEx) in our standard ELISA using eight uninfected rabbit sera (OD405 of 0.27 and 0.38, respectively; Fig. 4 and Table 1). None of the eight rabbits immunized with other species of Rickettsiales or the five antisera prepared against either L-cell, yolk sac, or E. coli exhibited reactivity higher than the cutoff for WCEx, while one rabbit antiserum against primary chick embryo reacted but barely above the breakpoint with r56 (OD405 of 0.28) (Fig. 4 and Table 1). On the other hand, 20 of 22 rabbit antisera against the eight Orientia antigenic prototypes reacted above the breakpoint with r56, and all sera exhibited positive ELISA with WCEx (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Although the r56 antigen gave lower ELISA reactivity at the amount employed than that obtained with WCEx, the Orientia rabbit antisera exhibited a very good correlation of ELISA reactions to the two antigens (r = 0.8, n = 22). One Kato antiserum and one TA686 antiserum which exhibited relatively low positive ELISA reactivity with WCEx did not react significantly with r56 antigen (Table 1). Consequently, the ELISA with folded r56 was almost as good a test as the standard ELISA in the detection of Orientia-specific antibodies by ELISA (specificity of 92%, sensitivity of 91%, and accuracy of 91%) with WCEx ELISA as the reference assay, even though r56 is only a truncated portion of one of the complex antigens found in WCEx.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of ELISA IgG reactivity of r56 and O. tsutsugamushi Karp strain whole-cell lysate with rabbit antisera (Table 1). Data for eight control uninfected rabbit sera (open diamonds), five antisera against nonrickettsial antigens (open triangles), eight antisera to Rickettsiales other than Orientia (open circles), and 22 antisera to eight antigenic prototypes of Orientia tsutsugamushi (solid circles) are shown. The dotted lines represent the mean plus 2 SD of reactions of the control rabbit sera. The solid line is the linear regression of data for the 22 anti-Orientia rabbit antisera (r = 0.81).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of ELISA reactivity of purified Karp whole-cell lysate and folded r56 with individual rabbit antisera

| Antisera against different antigens |

ELISA OD405a of whole-cell lysate (corresponding r56 result) |

|---|---|

| O. tsutsugamushi strains | |

| Karp | 0.94 (0.58), 1.87 (1.04), 1.81 (0.80), 1.83 (0.81) |

| Kato | 0.46 (0.22), 1.02 (0.50), 1.16 (0.77), 1.27 (0.58) |

| Gilliam | 0.54 (0.42), 1.20 (0.54) |

| TH1817 | 1.67 (0.59), 1.12 (0.60), 1.29 (0.53), 0.83 (0.47) |

| TA678 | 0.59 (0.48) |

| TA686 | 0.71 (0.26), 1.52 (0.86) |

| TA716 | 1.24 (0.48), 1.14 (0.51) |

| TA763 | 1.79 (0.72), 1.57 (0.89), 1.18 (0.82) |

| Other Rickettsiales | |

| R. prowazekii | 0.08 (0.12) |

| R. typhi | 0.18 (0.08) |

| R. rickettsii | 0.06 (0.04), 0.15 (0.14) |

| R. conorii | 0.10 (0.11), 0.07 (0.11) |

| E. sennetsu | 0.01 (0.05) |

| E. risticii | 0.01 (−0.01) |

| Nonrickettsial antigens | |

| Yolk sac | 0.22 (0.08) |

| L929 cell | 0.01 (−0.08) |

| Primary chick embryo | 0.20 (0.28) |

| RAW 264.7 cells | 0.22 (0.14) |

| E. coli HB101 | 0.32 (0.11) |

| No-antigen control (n = 8) | 0.135 ± 0.123 (0.093 ± 0.088)b |

OD405 listed are the difference between data with antigen and without antigen.

Mean ± SD for eight sera.

Comparison of r56 ELISA with IIP assay with human sera.

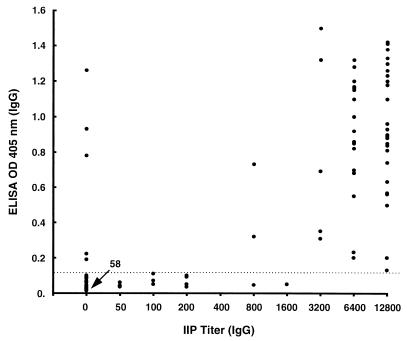

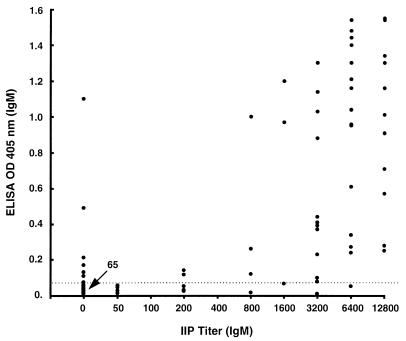

Seventy-four sera from healthy Thai soldiers were used to establish an ELISA breakpoint for positive reactions (mean plus 2 SD) with r56 as the antigen. These breakpoints were 0.11 (0.05 plus 0.06) OD405 for IgG and 0.064 (0.032 plus 0.032) OD405 for IgM at 1:400 serum dilution. The r56 ELISA OD405 of 128 sera from patients suspected of scrub typhus from Korat, Thailand were compared with the IgG and IgM titers determined by an IIP method with a mixture of intact Karp, Kato, and Gilliam prototypes of Orientia (20, 38) (Fig. 5 and 6). Using IIP titers as the “gold standard,” the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy values of ELISA results with the 128 test sera were calculated by using different positive breakpoints for the IIP assay (Table 2).

FIG. 5.

Scattergram of IgG ELISA reactivity of 128 Thai patient sera obtained with folded r56 and the corresponding IIP assay IgG titers. The dotted line shows the mean plus 2 SD of reactions of control healthy humans.

FIG. 6.

Scattergram of IgM ELISA reactivity of 128 Thai patient sera obtained with folded r56 and the corresponding IIP assay IgM titers. The dotted line shows the mean plus 2 SD of reactions of control healthy humans.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of efficiency of r56 ELISA with the IIP assay for 128 Thai patient sera

| Titer for IIP cutoff | Immunoglobulin | No. of positive sera by IIP | ELISA results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | |||

| 1:50 | IgG | 65 | 80 | 92 | 86 |

| IgM | 56 | 80 | 93 | 88 | |

| 1:200 | IgG | 58 | 90 | 93 | 91 |

| IgM | 51 | 88 | 94 | 91 | |

| 1:400 | IgG | 52 | 96 | 93 | 95 |

| IgM | 47 | 94 | 93 | 93 | |

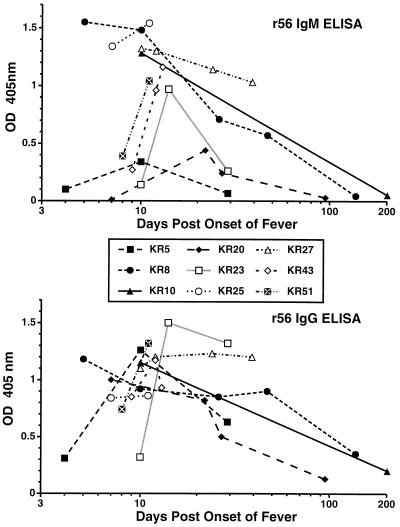

Sera from 13 isolate and PCR-confirmed cases of scrub typhus were analyzed to characterize the kinetics and magnitude of the IgM and IgG immune responses as measured by IIP assay titers and by r56 ELISA OD405. Representative data are shown in Fig. 7 and Table 3. Four sera from four different cases were available for the first week (days 4 to 7) after onset of fever. All sera were positive by IIP for both IgM and IgG, with titers between 3,200 and 12,800 for all cases. In contrast, by ELISA, KR5 (day 4, Table 3) had very low IgM and IgG OD405 and KR20 was still negative for IgM even at day 7, while the other two sera (KR8 and KR25) were more reactive by IgM assay than IgG. Sixteen sera from 12 cases were collected 8 to 14 days after the onset of fever. By IIP, both IgM and IgG titers were again high and within one twofold dilution for all of these sera except for the day 10 serum from KR23 which also had the lowest IgM and IgG ELISA OD405 (Table 3 and Fig. 7). Except for three other sera from days 8 to 10 (KR5, KR43, and KR51), which also had low IgM OD405, most sera had similar IgG and IgM ELISA reactions. Five sera from four cases were obtained in weeks 3 and 4 after infection. Two of the cases (KR8 and KR20) exhibited decreases in IgM OD405 by ELISA at this time which were not apparent by IIP assay, while the other reactions all remained strong. In weeks 5 and 6 after infection, two of five sera from different patients had decreases in IIP IgM titers (but not IgG titers), while three sera exhibited significant declines in ELISA IgM titers and one serum had a significant decline in ELISA IgG titers. In striking contrast, KR27 maintained high levels of specific antibody, as measured by all assays from 10 to 39 days (Table 3). With all six sera collected from six different cases 95 to 202 days after the onset of illness, IgM IIP titers and both IgM and IgG ELISA OD405 dropped significantly; in contrast, only one of the sera exhibited a decline in IgG IIP titers (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Time course of IgM and IgG reactivity of confirmed cases of scrub typhus by ELISA with folded r56 as the antigen.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of IIP assay titer with r56 ELISA OD405 obtained with human sera from confirmed cases of scrub typhus

| Patient | No. of days after onset of fever | IIP assay titer

|

r56 ELISA OD405

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgM | IgG | IgM | IgG | ||

| KR5 | 4 | 3,200 | 3,200 | 0.10 | 0.31 |

| KR5 | 10 | 6,400 | 12,800 | 0.34 | 1.26 |

| KR5 | 29 | 1,600 | 12,800 | 0.07 | 0.63 |

| KR8 | 5 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 1.55 | 1.18 |

| KR8 | 10 | 6,400 | 6,400 | 1.48 | 0.92 |

| KR8 | 26 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| KR8 | 47 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 0.57 | 0.90 |

| KR8 | 137 | 50 | 3,200 | 0.05 | 0.35 |

| KR10 | 10 | 12,800 | 6,400 | 1.30 | 1.15 |

| KR10 | 201 | 200 | 6,400 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| KR20 | 7 | 3,200 | 6,400 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| KR20 | 22 | 3,200 | 6,400 | 0.44 | 0.82 |

| KR20 | 27 | 6,400 | 12,800 | 0.24 | 0.50 |

| KR20 | 95 | 200 | 6,400 | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| KR23 | 10 | 200 | 800 | 0.14 | 0.32 |

| KR23 | 14 | 1,600 | 3,200 | 0.97 | 1.50 |

| KR23 | 29 | 800 | 3,200 | 0.26 | 1.32 |

| KR25 | 7 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 1.34 | 0.84 |

| KR25 | 11 | 6,400 | 6,400 | 1.54 | 0.86 |

| KR27 | 10 | 3,200 | 6,400 | 1.30 | 1.10 |

| KR27 | 12 | 6,400 | 12,800 | 1.30 | 1.20 |

| KR27 | 24 | 3,200 | 12,800 | 1.14 | 1.23 |

| KR27 | 39 | 3,200 | 12,800 | 1.03 | 1.20 |

| KR43 | 9 | 6,400 | 6,400 | 0.27 | 0.85 |

| KR43 | 12 | 6,400 | 6,400 | 0.96 | 1.17 |

| KR43 | 13 | 12,800 | 12,800 | 1.16 | 0.93 |

| KR51 | 8 | 3,200 | 12,800 | 0.39 | 0.74 |

| KR51 | 11 | 6,400 | 6,400 | 1.04 | 1.32 |

DISCUSSION

The truncated recombinant protein antigen r56 offers a considerable advantage over the antigens derived directly from O. tsutsugamushi in the manufacture of commercial tests. It can be easily purified in large amounts; compared with antigens in commercial tests, it is more stable and its quantity and purity can be more easily assessed. Refolded r56 from Karp strain exhibited cross-reactivity in ELISA with the rabbit antisera against various Orientia prototypes but did not react with most antisera against other rickettsial species or control antigens. The ELISA reactivity of r56 correlated well with that of whole-cell lysate antigens from the Karp strain. The feasibility of using r56 as a diagnostic reagent was further evaluated by ELISA using sera from patients with suspected scrub typhus and from healthy soldiers in Thailand, an area where scrub typhus is endemic. By using the indirect immunoperoxidase assay as the reference assay, the recombinant antigen exhibited a sensitivity and specificity of >90% for detection of both IgG and IgM in ELISA. The present r56 ELISA appears to have an assay accuracy similar or greater than those of several dot blot immunoassays which use whole-cell extracts of purified O. tsutsugamushi (10, 41, 42). These results strongly suggest that purified r56 is a suitable candidate for replacing the whole-cell rickettsial antigen currently used in the commercial dip-stick assay.

Expressed r56 does not contain the N-terminal 79 residues or the C-terminal 77 residues of the intact 56-kDa protein as deduced from the open reading frame of its encoding gene. Although no CD data are available for the native protein derived from Orientia for comparison, the strong seroreactivity of r56, which we observed with both rabbit and human sera, suggests that it presents epitopes similar to those found in the full-length native protein. The experimental data from CD measurements of r56 agree very well with the secondary structures predicted from the deduced protein sequence. Both regions deleted from the N and C termini were predicted to be rather hydrophobic and may be responsible for association of the intact 56-kDa protein with the rickettsial outer membrane. Truncation of these termini may have facilitated the refolding of the protein extracted from inclusion bodies; moreover, it clearly favors the solubility of r56 in aqueous solutions and simplifies the sample handling significantly.

A basic problem in the design of diagnostic tests for Orientia is that numerous serotypes exist. Eight prototypes (Gilliam, Karp, Kato, TA686, TA716, TA678, TA763, and TH1817) have been widely used as reference strains for MIF serotyping of isolates collected throughout the areas endemic for Orientia (13, 32). In recent years, several additional serotypes from Japan and Korea have been recognized (7, 29, 43). We have recently characterized more than 200 Orientia isolates by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of four different antigen gene homologs following their amplification by PCR (12, 18). A total of 45 RFLP variant types were identified. The dominant human immune response is against the variable 56-kDa outer membrane protein which is the major antigen distinguished in serotyping. Some of the antigenic serotypes found in Japan and Taiwan have recently been further subdivided by RFLP analysis of their 56-kDa genes (17, 25, 39). Both specific and cross-reactive domains exist in different homologs of this protein. DNA sequence analysis of 56-kDa genes from various serotypes has revealed that the sequences may be divided into four conserved and four variable domains (26, 34). These conserved domains of 56-kDa protein may account for the cross-reactivity of antisera against diverse serotypes, while the variable domains are very likely responsible for some of the serotype specificity observed in Orientia. r56 lacks most of the conserved regions of the 56-kDa protein at both the N terminus (missing 79 of 105 residues) and the C terminus (missing 77 of 107 residues). The conserved regions between the first and second variable domains and between the second and third variable domains are relatively short. Consequently, the broad reactivity of r56 may be due to the conserved region located between the third and fourth variable domains which is about 160 residues long. This is consistent with the r56 ELISA reactivity we observed with rabbit antisera against different serotypes and with diverse patient sera from Malaysia, Pescadore Islands (Taiwan) (data not shown), and Thailand (this study).

The variability of human responses to different serotypes is not well understood, and the geographic distribution of serotypes is not completely known. A particular serotype from one region may be infrequent or may not exist in another area. Therefore, the effectiveness of a given antigen from one serotype for detecting antibodies in patients from other regions is difficult to predict at the present time. Kim et al. (21) evaluated Korean sera (at least four serotypes in Korea) against an indigenous dominant Korean serotype (Boryong). We evaluated Thai sera (more than 20 indigenous serotypes which do not overlap with the Korean ones) by using Karp serotype antigen from New Guinea. Because of the variability, the sensitivity and specificity of the two tests do not have to be similar. The serological results may also be affected by the difference in truncation. r56 contains amino acids 80 to 456 with truncation at both the N and C termini and is expressed as a nonfusion protein, while Bor56 contains amino acids 85 to 532 without C-terminus truncation and is expressed as a protein fused to the maltose binding protein.

The excellent sensitivity and specificity of the Karp r56 ELISA compared with those of the IIP assay (Table 2) suggest that one protein antigen is sufficient for detecting anti-Orientia antibody in sera from patients with scrub typhus. However, we have observed that one anti-Kato rabbit serum and one anti-TA686 rabbit serum which exhibited low positive reactivity to whole-cell Karp lysate did not react with r56 antigen. If the IIP assay is taken as the standard for serology, both false positives and false negatives in r56 ELISA were observed (Fig. 5 and 6). Most false negatives occurred at low IIP titers. This may be due in part to strain specificity or due to the high dilution of sera used in this study. False positives based on IIP were examined by Western blotting. Three of five sera were confirmed to be true positives for IgM, and four of five sera were confirmed to be true positives for IgG. These results suggested that IIP assay results may be erroneous for some sera.

By MIF, Bourgeois et al. (3) found that two types of IgM responses occurred in scrub typhus patients in areas of endemicity. Type 1 responses, which were believed to be primary infections, exhibited an early, greater, and more rapid increase in IgM responses compared to the IgG responses, and the early IgM responses were relatively strain specific. In contrast, type 2 responders had suppressed and delayed IgM responses which were highly strain specific, while their IgG responses were immediate, strong, and not strain specific. The r56 IgM assay may be even more sensitive to differences in immune responses to the infecting strains than the IIP or the MIF assay, because no other conserved antigens are present as found in whole-organism assays. With the sera tested here, IgG antibodies could be detected by r56 ELISA as early as 4 days after reported onset of fever. In no cases were IgM antibodies detected earlier than IgG antibodies, although the time of onset of fever is difficult to verify, and the classic fourfold rise in titer was rarely observed in confirmed cases in this study (Table 3).

Comparison of the IgM and IgG r56 ELISA reactions may provide an improved method for estimating primary infections and reinfections in areas of high endemicity and permit more precise calculation of attack rates than can be obtained with whole-immunoglobulin tests (30, 31).

We have shown that r56 is a good candidate as a diagnostic reagent. r56 is under further study to refine the sensitivity and specificity of r56 ELISA prior to clinical trials. In addition, a semiquantitative dot blot immunoassay is under development to make the assay adaptable to a field setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ettore Apella for providing the CD measurements, Latchezar I. Tsonev for the data analysis, and Grace Lin for excellent technical assistance.

This research was supported by Naval Medical Research and Development Command (research work units 62787A.001.01.EJX.1295 and 61102A.001.01.BJX.1293).

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano K, Tamura A, Ohashi N, Urakami H, Kaya S, Fukushi K. Deficiency of peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide components in Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2290–2292. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2290-2292.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanar M A, Kneller D, Clark A J, Karu A E, Cohen F E, Langridge R, Kuntz I D. A model for the core structure of the Escherichia coli RecA protein. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:507–511. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeois A L, Olson J G, Fang R C, Huang J, Wang C L, Chow L, Bechthold D, Dennis D T, Coolbaugh J C, Weiss E. Humoral and cellular responses in scrub typhus patients reflecting primary infection and reinfection with Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:532–540. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozeman F M, Elisberg B L. Serological diagnosis of scrub typhus by indirect immunofluorescence. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;112:568–573. doi: 10.3181/00379727-112-28107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown G W, Robinson D M, Huxsoll D L, Ng T S, Lim K J, Sannasey G. Scrub typhus: a common cause of illness in indigenous populations. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1976;70:444–448. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(76)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown G W, Saunders J P, Singh S, Huxsoll D L, Shirai A. Single dose doxycycline therapy for scrub typhus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:412–416. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang W-H. Current status of tsutsugamushi disease in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 1995;10:227–238. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1995.10.4.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ching W-M, Carl M, Dasch G A. Mapping of monoclonal antibody binding sites on CNBr fragments of the S-layer protein antigens of Rickettsia typhi and Rickettsia prowazekii. Mol Immunol. 1992;29:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(92)90161-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen F E, Abarbanel R M, Kuntz I D, Fletterick R J. Secondary structure assignment for α/β proteins by a combinatorial approach. Biochemistry. 1983;22:4894–4904. doi: 10.1021/bi00290a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crum J W, Hanchalay S, Eamsila C. New paper enzyme-linked immunosorbent technique compared with microimmunofluorescence for detection of human serum antibodies to Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:584–588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.6.584-588.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasch G A, Halle S, Bourgeois L. Sensitive microplate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibodies against the scrub typhus rickettsia, Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9:38–48. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.1.38-48.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasch G A, Strickman D, Watt G, Eamsila C. Measuring genetic variability in Orientia tsutsugamushi by PCR/RFLP analysis: a new approach to questions about its epidemiology, evolution, and ecology. In: Kazar J, editor. Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases. Vth International Symposium. Bratislava, Slovakia: Slovak Academy of Sciences; 1996. pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dohany A L, Shirai A, Robinson D M, Ram S, Huxsoll D L. Identification and antigenic typing of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in naturally infected chiggers (Acarina: Trombiculidae) by direct immunofluorescence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:1261–1264. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuya Y, Yoshida Y, Katayama T, Kawamori F, Yamamoto S, Ohashi N, Kamura A, Kawamura A., Jr Specific amplification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi DNA from clinical specimen by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2628–2630. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2628-2630.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenfield N, Fasman G D. Computed circular dichroism spectra for the evaluation of protein conformation. Biochemistry. 1969;10:4108–4116. doi: 10.1021/bi00838a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson B. Identification and partial characterization of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi major protein immunogens. Infect Immun. 1985;50:603–609. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.3.603-609.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horinouchi H, Murai K, Okayama A, Nagatomo Y, Tachibana N, Tsubouchi H. Genotypic identification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of DNA amplified by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:647–651. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly D J, Dasch G A, Chye T C, Ho T M. Detection and characterization of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in infected Leptotrombidium (Leptotrombidium) fletcheri chiggers (Acari: Trombiculidae) with the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Entomol. 1994;31:691–699. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/31.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly D J, Marana D, Stover C, Oaks E, Carl M. Detection of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by gene amplification using polymerase chain reaction techniques. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;590:564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly D J, Wong P W, Gan E, Lewis G E., Jr Comparative evaluation of the indirect immunoperoxidase test for the serodiagnosis of rickettsial disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:400–406. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim I-S, Seong S-Y, Woo S-G, Choi M-S, Chang W-H. High-level expression of a 56-kilodalton protein gene (bor56) of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi Boryong and its application to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:598–605. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.3.598-605.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim I-S, Seong S-Y, Woo S-G, Choi M-S, Chang W-H. Rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus by a passive hemagglutination assay using recombinant 56-kilodalton polypeptide. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2057–2060. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2057-2060.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moree M F, Hanson B. Growth characteristics and proteins of plaque-purified strains of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3405–3415. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3405-3415.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murata M, Yoshida Y, Osono M, Ohashi N, Oyanagi M, Urakami H, Tamura A, Nogami S, Tanaka H, Kawamura A., Jr Production and characterization of monoclonal strain-specific antibodies against prototype strains of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:599–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi N, Koyama Y, Urakami H, Fukuhara M, Tamura A, Kawamori F, Yamamoto S, Kasuya S, Yoshimura K. Demonstration of antigenic and genotypic variation in Orientia tsutsugamushi which were isolated in Japan, and their classification into type and subtype. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohashi N, Nashimoto H, Ikeda H, Tamura A. Diversity of immunodominant 56-kDa type-specific antigen (TSA) of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Sequence and comparative analyses of the genes encoding TSA homologues from four antigenic variants. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12728–12735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohashi N, Tamura A, Ohta M, Hayashi K. Purification and partial characterization of a type-specific antigen of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1427–1431. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.5.1427-1431.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohashi N, Tamura A, Sakurai H, Suto T. Immunoblotting analysis of anti-rickettsial antibodies produced in patients of tsutsugamushi disease. Microbiol Immunol. 1988;32:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1988.tb01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohashi N, Tamura A, Sakurai H, Yamamoto S. Characterization of a new antigenic type, Kuroki, of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi isolated from a patient in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2111–2113. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2111-2113.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson D M, Brown G, Gan E, Huxsoll D L. Adaptation of a microimmunofluorescence test to the study of human Rickettsia tsutsugamushi antibody. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976;25:900–905. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1976.25.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders J P, Brown G W, Shirai A, Huxsoll D L. The longevity of antibody to Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in patients with confirmed scrub typhus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1980;74:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(80)90254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirai A, Robinson D M, Brown G W, Gan E, Huxsoll D L. Antigenic analysis by direct immunofluorescence of 114 isolates of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi recovered from febrile patients in rural Malaysia. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1979;32:337–344. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.32.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman D J, Wisseman C L., Jr Comparative ultrastructural study on the cell envelopes of Rickettsia prowazekii, Rickettsia rickettsii, and Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect Immun. 1978;21:1020–1023. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.3.1020-1023.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stover C K, Marana D P, Carter J M, Roe B A, Mardis E, Oaks E V. The 56-kilodalton major protein antigen of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi: molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the sta56 gene and precise identification of a strain-specific epitope. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2076–2084. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2076-2084.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studier F W, Moffatt B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugita Y, Nagatani T, Okuda K, Yoshida Y, Nakajima H. Diagnosis of typhus infection with Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:357–360. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-5-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suto T. Rapid serological diagnosis of tsutsugamushi disease employing the immuno-peroxidase reaction with cell cultured rickettsia. Clin Virol. 1980;8:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suwanabun N, Chouriyagune C, Eamsila C, Watcharapichat P, Dasch G A, Howard R S, Kelly D J. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in Thai scrub typhus patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:38–43. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura A, Ohashi N, Koyama Y, Fukuhara M, Kawamori F, Otsuru M, Wu P-F, Lin S-Y. Characterization of Orientia tsutsugamushi isolated in Taiwan by immunofluorescence and restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;150:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamura A, Ohashi N, Urakami H, Miyamura S. Classification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in a new genus, Orientia gen. nov., as Orientia tsutsugamushi comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:589–591. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-3-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Urakami H, Yamamoto S, Tsuruhara T, Ohashi N, Tamura A. Serodiagnosis of scrub typhus with antigens immobilized on nitrocellulose sheet. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1841–1846. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1841-1846.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41a.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services publication (National Institutes of Health) 86–23. U.S. Washington, D.C: Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weddle J R, Chan T C, Thompson K, Paxton H, Kelly D J, Dasch G, Strickman D. Effectiveness of a dot-blot immunoassay of anti-Rickettsia tsutsugamushi antibodies for serologic analysis of scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamamoto S, Kawabata N, Tamura A, Urakami H, Ohashi N, Murata M, Yoshida Y, Kawamura A., Jr Immunological properties of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi, Kawasaki strain, isolated from a patient in Kyushu. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:611–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb02988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamamoto S, Minamishima Y. Serodiagnosis of tsutsugamushi fever (scrub typhus) by the indirect immunoperoxidase technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1128–1132. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1128-1132.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]