Abstract

Objectives

We introduced the cohort studies included in the Korean Cohort Consortium (KCC), focusing on large-scale cohort studies established in Korea with a prolonged follow-up period. Moreover, we also provided projections of the follow-up and estimates of the sample size that would be necessary for big-data analyses based on pooling established cohort studies, including population-based genomic studies.

Methods

We mainly focused on the characteristics of individual cohort studies from the KCC. We developed “PROFAN”, a Shiny application for projecting the follow-up period to achieve a certain number of cases when pooling established cohort studies. As examples, we projected the follow-up periods for 5000 cases of gastric cancer, 2500 cases of prostate and breast cancer, and 500 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The sample sizes for sequencing-based analyses based on a 1:1 case-control study were also calculated.

Results

The KCC consisted of 8 individual cohort studies, of which 3 were community-based and 5 were health screening-based cohorts. The population-based cohort studies were mainly organized by Korean government agencies and research institutes. The projected follow-up period was at least 10 years to achieve 5000 cases based on a cohort of 0.5 million participants. The mean of the minimum to maximum sample sizes for performing sequencing analyses was 5917–72 102.

Conclusions

We propose an approach to establish a large-scale consortium based on the standardization and harmonization of existing cohort studies to obtain adequate statistical power with a sufficient sample size to analyze high-risk groups or rare cancer subtypes.

Keywords: Data pooling, Cohort studies, Follow-up studies

INTRODUCTION

In Korea, interest in large-scale population cohorts increased in the 1990s and the 2000s after the Kangwha Cohort Study (KCS), Korea’s first cohort study. Thus, individual researchers and government institutions have sporadically built cohort studies as infrastructure [1].

From 2004 to 2009, the Korean National Cancer Center (KNCC) conducted the “Attributable Causes of Cancer in Korea in the Year 2009” project to estimate the population attributable fraction (PAF) of cancers in Korea [2]. This study aimed to calculate the fraction of cancers attributable to major risk factors from a representative data source. This meta-analysis assessed the major risk factors for cancer in Koreans, based on the results of the association between major risk factors and individual cancers. The PAF of cancer is an index used to estimate the degree of cancer prevention in the population when 100% of a risk factor is removed, and it is an important index for cancer prevention in the population [3]. At this time, we estimated the cancer risk for various risk factors in Korean cohort studies. However, the follow-up period of each cohort study was short, and risks for uncommon cancers were not estimated owing to the limited number of patients. Subsequently, with longer follow-up periods, sufficient statistical data were acquired.

In the 2000s, large-scale cohort studies based on the Korean health examination system using cancer screening were established [4]. Using multiple large-scale Korean cohort studies that had already been established, we constructed the “Fraction of Cancer Attributable to Lifestyle and Environmental Factors in Korea in 2015” project [5]. In the third phase of this project in 2020, the researchers from individual cohort studies who participated in this project study established the Korean Cohort Consortium (KCC).

This study aimed to introduce the Korean cohort studies included in the KCC. In addition, we discussed the importance of pooling cohorts based on examples of several established international consortia. We also presented the sample sizes and follow-up periods of the pooled cohorts required to perform big-data analyses, including population-based genomic studies.

METHODS

Introduction to Cohort Studies Established in Korea

We first considered individual cohort studies from the KCC that participated in the “Fraction of Cancer Attributable to Lifestyle and Environmental Factors in Korea in 2015” project. We focused on the number of cohort members enrolled thus far, the cohort registration year, follow-up methods, and cancer assessment. The studies conducted by individual researchers were divided into community-based and screening-based cohorts to briefly describe their statuses. In addition to these cohort studies, we included data from population cohort studies conducted by government agencies and research institutes. We also described Korean cohort studies that participated in the Asia Cohort Consortium (ACC) and the status of individual cohort studies in Asia.

Projection of Follow-up Periods to Achieve a Certain Number of Cases

The 5-year-interval age-specific and sex-specific numbers of incident cancer cases between 2000 and 2019, as well as the mid-year population numbers, which are the estimated yearly values from the census data, were obtained from the Korea Statistical Information System (KOSIS) of the National Statistical Office in Korea [6]. They were divided into age groups of 5-year intervals. We did not consider the age groups <20 years due to the small number of cancer cases in those age groups. The age-standardized rate (ASR) in each year was calculated based on the population standardized by the mid-year population in 2000 from KOSIS.

The trends in ASRs were summarized as annual percent changes (APCs) [7]. With the APC approach, the case rates were assumed to change annually at a constant percentage. The average annual percent change (AAPC), a measure of trends over a pre-specified fixed interval, was calculated by summarizing the trend over the time period as a weighted average of the APCs [7]. All-cause-specific trends for age-standardized mortality and prevalence rates were analyzed using the joinpoint regression method with the Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.9.1 (Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA).

Furthermore, assuming 0.5 million, 0.7 million, and 1.0 million participants from the pooled cohorts established in 2000, we projected the follow-up periods required to achieve 5000 cases for gastric cancer, 2500 cases for breast and prostate cancer, and 500 cases for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in Korea.

We developed the “PROjection of Follow-up period to Achieve a certain Number of cases (PROFAN)” application within Shiny, an R that includes a variety of functions and formulas for researchers—even those unaccustomed with R programming—to analyze and visualize their own databases (available online at https://sjunlee.shinyapps.io/PROFAN/). The equations, which were based on the formulas developed by Quante et al. [8], included in “PROFAN” are shown in Supplemental Material 1.

Sample Size Estimation for Sequencing-based Association Studies

We simulated genetic sequence data using demographic models based on the data from Williamson et al. [9]. The parameters of the model followed the probability of having a selection coefficient of 0.37; shape and scale parameters of gamma distribution of 0.23 and 0.185×2.0, respectively; and a dominance coefficient of 0.5. The gene range was 1800–10 000, with a mutation rate per base pair of 1.8E-08. We assumed that the genetic variants consisted of 20% protective, 43% deleterious, and 37% non-synonymous variants. Because not all functional rare variants are directly causal to the phenotype, a random set of 50% of the variants was included in the analysis to assess their effect on the sample size through non-causal “noise” data.

The odds ratios were assigned to be within the range of 1.5 to 2.0 for rare variants, and 1.2 for common variants depending on whether the minor allele frequency (MAF) was <0.01; based on α=0.05, the sample size was calculated assuming a 1:1 case-control study given 80% power. The significance level for whole-exome sequencing analysis was α=2.5E-06 (Bonferroni-corrected p-value for testing 20 000 genes) with 100 replications based on the Monte Carlo method. All sample size estimations were performed using SEQpower [10].

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the status of the individual cohort studies in the KCC, which mainly consisted of 3 community-based and 5 health screening-based cohorts, respectively. The KCS, which was the first community-based cohort in Korea, was established based on the local population over the age of 55 years on Kangwha Island, with 6372 individuals followed up over 24 years [1]. The Korean Multi-center Cancer Cohort (KMCC) study began in 1993, and by 2004, approximately 20 000 participants from the local population were enrolled in this study [4]. The KMCC was first constructed as a part of the control area of the Korea Radiation Effect & Epidemiology Cohort [11]. Later, as an independent cohort study, it was used to estimate cancer incidence and mortality over approximately 10 years. The Namwon study/Dong-gu study (NWS/DGS), whose participants were residents of both Namwon, a representative rural area, and Dong-gu, a representative urban area, was also followed over approximately 10 years [12].

Table 1.

Individual Korean cohort studies in the KCC

| Cohorts | Subjects, n | Enrollment period | Age, mean±SD | Male, n (%) | Cancer outcome | Median FU (Max), y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community-based cohorts included in the KCC | ||||||

| KCS | 6372 | 1985 | >55.0 | 2724 (42.7) | Death | − (24.0) |

| KMCC | 20 631 | 1993–2005 | 54.1±14.3 | 8232 (39.9) | Incidence | 13.4 (21.8) |

| NWS/DGS | 19 927 | 2004–2007 | 63.25±8.1 | 7912 (39.7) | Incidence | 10.9 (13.9) |

| 2007–2010 | Death | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Health screening-based cohorts included in the KCC | ||||||

| KNCC | 37 264 | 2002–2014 | 49.6±9.2 | 19 153 (51.4) | Incidence | 9.1 (15.4) |

| KSCS | 319 768 | 2002–2018 | 37.7±9.7 | 173 347 (54.2) | Incidence | 4.8 (15.0) |

| 659 442 | 2002–2018 | 39.7±10.8 | 146 421 (22.2) | Death | 7.4 (17.0) | |

| KCPS-II | 159 844 | 2004–2013 | 41.5±10.5 | 96 537 (60.4) | Incidence | 9.0 (12.9) |

| HPC-SNUH | 17 650 | 2004–2016 | 53.8±10.7 | 8961 (50.8) | Incidence | 4.4 (7.1) |

| H-PEACE | 47 168 | 2005–2008 | 45.7±11.7 | 25 754 (54.6) | Incidence | 2.0 (15.1) |

KCC, Korea Cohort Consortium; SD, standard deviation; FU, follow-up; Max, maximum; KCS, Kangwha Cohort Study; KMCC, Korean Multicenter Cancer Cohort Study; NWS/DGS, Namwon study/Dong-gu study; KNCC, Korean National Cancer Center Cohort; KSCS, Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study; KCPS-II, Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II; HPC-SNUH, Health Promotion Center of Seoul National University Hospital; H-PEACE, Health and Prevention Enhancement.

The health screening-based cohort studies in Korea that began in 2000 were established based on Korea’s health check-up services (Table 1). These cohort studies were cost-effective because participants voluntarily visited health check-up centers. In addition, cohort studies in Korea have the advantage of being able to collect repeated test information owing to a system that requires annual or biennial health check-ups. The KNCC, Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study (KSCS), Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II (KCPS-II), Health Promotion Center of Seoul National University Hospital (HPC-SNUH), and Health and Prevention Enhancement (H-PEACE) studies were included [13–17].

Table 2 shows the population-based cohort studies organized by Korean government agencies and research institutes. The Korean Genome Epidemiology Study (KoGES), a multi-cohort study, was established by the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) from 2001 to 2015 [18]. The 3 general population cohorts within the KoGES were the Ansan-Ansung Cohort study, Health Examinee cohort study (HEXA), and Cardiovascular Disease Association Study (CAVAS), with approximately 200 000 enrolled participants [18]. Moreover, the Korea Biobank Array (KoreanChip) for approximately 70 000 participants and multi-omics data based on the KoGES were provided by researchers [19]. Another cohort study tracking mortality during the follow-up period was established by the KDCA based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), consisting of participants from a random sampling of all Koreans to regularly identify the prevalent risk factors and diseases in Korea [20]. The Korea National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) can be regarded as a retrospective cohort representing Koreans because it is possible to identify age-specific and occupation-specific population groups based on Korea’s national insurance system [21]. Moreover, it was provided to researchers as a retrospective cohort by random sampling of 1 million participants in 2002 within the KNHIS. Researchers also can be provided with the National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) cohort, which was constructed by random sampling of approximately 10% of individuals aged 40–70 years old between 2002 and 2003 [22]. The KNHIS also provided a customized retrospective cohort database reflecting researchers’ needs [22].

Table 2.

Population-based cohort studies conducted by Korean government agencies or research institutes

| Cohorts | Subjects, n | Recruitment period | Age, mean±SD | Male, n (%) | Median FU (Max) y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KoGES1 | 152 027 | 2001–2015 | 50±16.2 | 55 368 (36.4) | 9.4 (17.6) |

| KNHANES | 79 207 | 2007–2015 | 54±8.7 | 21 139 (43.0) | 7.3 (11.4) |

| Customized NHIS-HEALS based retrospective cohort study2 | 10 271 473 | 2004–2005 | 45±14.0 | 5 860 902 (57.1) | 13.1 (15.2) |

| Customized KNHIS Cancer Screening-based retrospective cohort study2 | 7 654 993 | 2004–2007 | 50.6 | 2 958 317 (38.6) | 7.6 (15.1) |

SD, standard deviation; FU, follow-up; Max, maximum; KoGES, Korean Genome Epidemiology Study; KNHANES, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS-HEALS, National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening Cohort; KNHIS, Korean National Health Insurance Service.

The KoGES is a multicohort study with nearly 200 000 people, including the Ansan-Ansung community cohort study (n=10 000); The Health Examinees-based cohort study with participants living in urban areas of Korea (n=170 000); The cohort study of people living in rural areas of Korea (n=20 000); Of them 152 027 participants’ data were used in the calculation of the population-attributable fraction for cancers in Korea, 2015.

There are various types of the KNHIS-based retrospective cohort study databases, including the KNHIS-Health Screening-based retrospective cohort study (n=500 000), the KNHIS cohort of 1.0 million people obtained through random sampling among Korean health insurance subscribers (n=1 000 000), a female worker-based cohort among Korean health insurance subscribers, an elderly-based cohort of Korean health insurance subscribers, and a cohort of children and adolescents among Korean health insurance subscribers; In addition, a retrospective cohort tailored to researchers’ needs is being distributed; The 2 customized cohorts were used in the calculation of the population attributable fraction for cancers in Korea, 2015.

Table 3 shows the 37 cohort studies that were enrolled in the ACC. Although 9 cohort studies in Korea were included in the ACC, the total number of participants in Korea was smaller than that of China or Japan [23]. Detailed information on these studies and their contacts are described in Supplemental Material 2.

Table 3.

Cohort studies participating in the Asia Cohort Consortium

| Cohorts | Country | Subjects | Recruitment period | Age | Male | Cancer outcomes | Follow-up | Recruitment status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| n | mean±SD | n (%) | Incidence | Mortality | |||||

| Health Effects for Arsenic Longitudinal Study Bangladesh (HEALS) | Bangladesh | 65 876 | 2000–2006 | - | - | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| China Hypertension Survey Epidemiology Follow-up Study (CHEFS) | China | 169 871 | 1991–2000 | - | 83 533 (49.2) | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Linxian General Population Trial Cohort (Linxian) | China | 29 584 | 1986–1991 | - | 13 313 (45.0) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Shanghai Cohort Study (SCS) | China | 18 244 | 1986–1989 | 55.8±5.7 | 18 244 (100) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Shanghai Men’s Health Study (SMHS) | China | 61 469 | 2001–2006 | 54.9±9.7 | 61 469 (100) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS) | China | 74 940 | 1996–2000 | 52.6±9.1 | 0 (0.0) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| A Multi-center Ultrasound-based Breast Cancer Screening Cohort Study in China | China | 1973 | 2016–2017 | 45.4±9.7 | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| The Mumbai cohort study (MCS) | India | 148 173 | 1991–2003 | 50.8±11.2 | 88 658 (59.8) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Radiation Epidemiologic Studies (Karunagappally Cohort Study) | India | 359 619 | 1990–1997 | - | - | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Golestan Cohort Study | Iran | 50 045 | 2004–2008 | - | 21 241 (42.4) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in IrAN (PERSIAN) | Iran | 170 000 | 2014- | - | - | Y | Y | Active | Y |

|

| |||||||||

| Pars Cohort Study (PCS) | Iran | 9264 | 2012–2014 | - | 4276 (46.2) | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Mashhad Stroke and Heart Atherosclerotic Disorder (MASHAD Study) | Iran | 9761 | 2010–2020 | - | 3903 (40.0) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) | Iran | 15 005 | 1999 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Tehran Cohort Study | Iran | 8296 | 2016–2019 | 53.8±12.8 | 3818 (46.0) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Surveillance of Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases in Iran STEPs 2016 (STEPs 2016) | Iran | 30 541 | 2005–2011 | - | 14 565 (47.7) | - | - | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Japan Public Health Center-based prospective Study1 (JPHC1) | Japan | 61 595 | 1990–1992 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Japan Public Health Center-based prospective Study2 (JPHC2) | Japan | 78 825 | 1992–1995 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Japan Collaborative Cohort Study (JACC) | Japan | 110 792 | 1988–1990 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Miyagi Cohort study (Miyagi) | Japan | 47 605 | 1990 | 52.0±7.5 | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Ohsaki National Health Insurance Cohort Study (Ohsaki) | Japan | 52 029 | 1995 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Life Span Study Cohort (LSS) | Japan | 120 321 | 1950 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study (IPHS) | Japan | - | - | Y | Y | Active | Y | ||

| 1st cohort | 98 326 | 1993 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2nd cohort | 53 339 | 2009 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Health-checkup cohort | 700 000 | 1993- | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| Takayama Study | Japan | 31 552 | 1992 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Three-Prefecture Cohort Study, Miyagi (3pref. Miyagi) | Japan | 31 345 | 1983–1985 | - | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Three-Prefecture Cohort Study, Aichi (3pref. Aichi) | Japan | 33 529 | 1985 | 56.2±11.3 | - | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| The Three Prefecture Study Osaka | Japan | 35 755 | 1983–1985 | - | - | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Korean Multi-center Cancer Cohort (KMCC) | Korea | 20 631 | 1993–2004 | 54.1±14.3 | 8232 (40.0) | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Seoul Male Cancer Cohort Study (SMCC) | Korea | 14 533 | 1992–1993 | - | - | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Korean National Cancer Screenee Cohort (KNCC) | Korea | 43 038 | 2002- | - | - | Y | Y | Active | Y |

|

| |||||||||

| The Namwon study | Korea | 33 068 | 2004–2007 | - | 14 960 (45.2) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Kangwha cohort study | Korea | 6374 | 1985 | - | 2724 (42.7) | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| The Health Examinees’ study | Korea | 152 027 | -2015 | 50.0±16.2 | 55 368 (36.4) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Health and Prevention Enhancement Cohort (H-PEACE) | Korea | 91 336 | 2003–2014 | 45.5±11.7 | 50 507 (55.3) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Seoul National University Hospital Health Promotion Cohort Study (HPC) | Korea | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

|

| |||||||||

| Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II (KCPS-II) Severance | Korea | 156 701 | 2004–2008 | - | 94 840 (60.5) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Nationwide cancer cohort study (MON-COHORT) | Mongolia | 2280 | 2009 | 52.9±9.2 | 851 (37.3) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Malaysian Cohort Study | Malaysia | 106 527 | 2006–2012 | - | 44 897 (42.1) | Y | Y | Active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Cohort study on clustering of lifestyle risk factors and understanding its association with stress on health and wellbeing among school teachers in Malaysia (CLUSTer) | Malaysia | expected 10 000 | 2013–2014 | - | - | - | - | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| The Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS) | Singapore | 63 257 | 1993–1998 | 56.5±8.0 | 27 954 (44.2) | Y | Y | - | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Singapore Population Health Studies | Singapore | - | - | Y | Y | Not active | N | ||

| Multiethnic cohort, Phase 1 | 14 729 | 2004–2010 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Multiethnic cohort, Phase II | 34 870 | 2013–2016 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Diabetic cohort | 14 033 | 2004–2010 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Singapore health studies | 5074 | 2012–2015 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Community health study | 7860 | 2015–2016 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| Community-based Cancer Screening Project (CBCSP) | Taiwan | 23 820 | 1991–1992 | - | - | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Cardiovascular Diseases Risk Factor two-Township Study (CVDFACTS) | Taiwan | 6312 | 1991–1993 | - | 2902 (46.0) | Y | Y | Not active | N |

|

| |||||||||

| Taiwan Biobank | Taiwan | 159 195 | 2012- | - | - | Y | Y | Active | Y |

|

| |||||||||

| The Taiwan MJ Cohort: half a million Chinese with repeated health surveillance | Taiwan | 593 215 | 1994–2011 | - | 281 892 (47.5) | Y | Y | - | N |

SD, standard deviation.

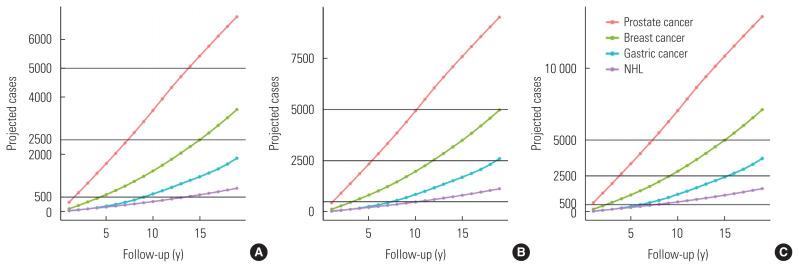

Supplemental Material 3 shows the projected incidence rates from 2000 to 2019 based on changing demographics and the changes in AAPCs for gastric cancer, NHL, prostate cancer, and breast cancer in female, male, and both sexes combined. Although the ASR of gastric cancer decreased from 2000 to 2019, with an AAPC of −2.46% (95% CI, −2.71 to −2.21) in male and −1.85% (95% CI, −2.14 to −1.57) in female, that of NHL, prostate cancer, and breast cancer increased from 2000 to 2019, with AAPCs of 1.75% (95% CI, 1.52 to 1.97) in male and 2.63% (95% CI, 2.42 to 2.83) in female, 8.22% (95% CI, 7.11 to 9.33) in male, and 5.53% (95% CI, 4.72 to 6.35) in female, respectively (Supplemental Material 3). Based on the established pooled cohorts of 0.5 million, 0.7 million, and 1.0 million participants, the required follow-up periods were 14 years, 11 years, and 8 years to obtain 5000 cases of gastric cancer; 14 years, 11 years, and 8 years to obtain 500 cases of NHL; >19 years, 19 years, and 16 years to obtain 2500 cases of prostate cancer; and 16 years, 12 years, and 10 years to obtain 2500 cases of breast cancer (Figure 1 and Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 1.

Projected incidence cases in Korea by 2000 to 2019, assuming that (A) 0.5, (B) 0.7, and (C) 1.0 million participants from the pooling cohort established in 2000. NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The minimum sample size required was 5917±1770 for 209 genetic variants with a mean MAF of 0.033±0.001, and the maximum sample size required was 72 102±74 562 for 50 genetic variants with a mean MAF of 0.004±0.000 (Supplemental Material 4). Although the mean required sample size decreased to 43 687±27 131, even with the mean MAF increasing only by 0.006±0.000 in the 50 rarer genetic variants used to estimate the effect size with sufficient statistical power, the required sample size increased dramatically in the sequencing data analysis (Supplemental Material 4).

DISCUSSION

The KCC consists of 8 individual cohort studies (KCS, KMCC, NWS/DGS, KNCC, KSCS, KCPS-II, HPC-SNUH, and H-PEAC) [1, 4, 12–17] and 4 open public cohort studies organized by Korean government agencies or research institutes (KoGES, KNHANES, the customized NHIS-HEALS based retrospective cohort study, and the customized KNHIS cancer screening-based retrospective cohort study) [18,21,22]. The purpose of the “Fraction of Cancer Attributable to Lifestyle and Environmental Factors in Korea in 2015” project was to calculate the incidence and mortality rate (%) due to exposure to each risk factor for cancer incidence and mortality among Koreans in 2015, based on lifestyle and environmental factors associated with carcinogenicity or epidemiological causality in the Korean population.

Clinical trials, as experimental designs for humans, are efficient for identifying the causality between risk factors and outcomes [24]. However, the manipulation of risk factors through experimental designs poses ethical issues [25]. Therefore, observational cohort studies are important in elucidating the causal relationships between risk factors and diseases.

Cohort studies have investigated the associations between risk factors and cancer. Based on the results of epidemiological investigations, international cancer research institutions such as the International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Cancer Research Fund International have published prevention guidelines for various cancers [26,27].

Pooled analysis, a method of reanalyzing data by collecting individual cohorts, is used when individual studies are too small to yield conclusions [28]. One method of pooling data is to reanalyze the effect size by meta-analysis based on the initial results; another is to harmonize individual cohort studies.

The Asia Pacific Cohort Research Collaboration (APCSC) is a representative project for pooling data for meta-analyses [29]. One study based on APCSC estimating regional differences in mortality numbers showed that useful results could be obtained even with a relatively small number of variables from pooled data, suggesting the possibility of further harmonization of multiple studies [30].

Large population-based pooling of data from the harmonization of individual cohort studies was initiated mainly in North American and European populations to estimate the associations between risk factors and diseases. In Denmark and Sweden, a nationwide cohort study was conducted by establishing a database based on the registration system for mortality [31]. The National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium was initiated in 2001 as pooled data, including 58 cohort studies from 20 countries with more than 9 million participants and 2 million specimens [32]. As most cohort studies consisted of North American and European populations, the associations between risk factors and their causality were different for Asian and African populations.

With an emphasis on the importance of cohort studies with large populations, pooled data from cohort studies for Asian populations were also initiated, following Western countries. It was not until the 2000s that cohort studies began in several Asian countries. The ACC reported the first results from collaborative cohort studies with a population of over 1 million Asian participants in 2010 [33]. In that study, the association between lower body mass index and mortality differed from that in Western populations.

Based on the need not only to obtain a large-scale genomic database, but also to identify the causal relationships of risk factors by stratifying the population for predicting individual risk for cancer subtypes, the UK Biobank as a prospective cohort study was constructed in 2006, with about 0.5 million participants from across the United Kingdom [34]. The UK Biobank collects genotyping data, biological samples such as blood, urine, and saliva, and various types of imaging information.

Based on the statistical power calculations for nested case-control studies from large-scale cohorts, approximately 5000 cases to 10 000 cases would be required for reliable odds ratios of 1.3 to 1.5 to assess the effects of exposures, which correspond to the reported upper limit from genome-wide association studies of various conditions [35]. In addition, at least 5000 cases are needed to conduct not only studies of gene and environmental interactions, but also research on the subtypes of each disease, such as the different pathological findings from histologically different gastric cancer types [36]. Therefore, the follow-up period to obtain 5000–10 000 cases in the UK Biobank was calculated [37], and it was suggested that continuing follow-up until 2042 would be necessary [38]. In Korea, depending on the incidence rates, assuming a pooled cohort study based on approximately 0.5 million participants, a follow-up period of at least 10 years would be required to achieve 5000 cases (Supplemental Material 3). To observe such large numbers of disease cases within a reasonable follow-up period, prospective cohorts would need large numbers of participants.

Pooling data based on the harmonization of established individual cohort studies has the advantage of obtaining statistical power based on a sufficient sample size even for a small number of observations, such as high-risk groups or rare cancer subtypes. Nevertheless, since databases derived from different laboratories are pooled, variation between cohorts is a statistical challenge [39]. For example, pooled retrospective cohort studies differ in study design, methodologies, age groups, races, and regions. In addition, the definition of variables for each individual cohort study can be different. According to the established international cohort consortium [23,32], the data management center usually standardizes variables from different cohort studies to overcome the challenges of harmonization [40]. The data management center generally makes the units of continuous variables match and designates criteria for categorical variables to harmonize the data by unifying the criteria of categories in each individual cohort. Therefore, the harmonization of data from multiple cohorts with good quality control and standardization for obtaining a large sample size enables studies to be conducted on diseases with high importance but relatively low case numbers, which would be difficult to perform in individual cohorts [40]. Therefore, the KCC plans to manage variable coordination through its data management center in the future.

The construction of large-scale cohorts with more diverse and precise information is also important. Although the establishment of new cohort studies to follow-up participants is time-consuming and expensive, variables can be unified from the beginning in the large-scale cohort planning stage. In addition, this approach has the advantage of obtaining enough participants for a group with a small number of observations at the time of recruitment.

Cohort studies play a key role in determining the causes of cancer in the general population. However, the statistical power of individual data sources is insufficient both to analyze the associations between rare risk factors and cancer and to identify the causes of rare cancers. Moreover, it is difficult to obtain information on detailed subtypes of cancer, which would be required for personalized risk prediction and prevention, from individual cohort studies owing to the insufficient sample size. Therefore, a cost-effective approach that overcomes the lack of statistical power in individual cohorts by establishing a large-scale cohort consortium based on existing cohort studies must also be considered. In particular, a cohort consortium based on the harmonization of individual cohorts is required to raise the low statistical power of multiple comparisons for the analysis of big data, including genomic information. Consequently, a large-scale cohort consortium is recommended to identify the causes of disease subtypes and predisposing factors based on the standardization and harmonization of existing cohort studies with continuing follow-up.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES; 6635-302), National Institute of Health, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Republic of Korea, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, and customized cohort databases provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS-2019-1-495, NHIS-2020-1-164), Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute (OSHRI), and Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

This study was funded partly by the Korean Foundation for Cancer Research (grant No. CB-2017-A-2), a grant from Seoul National University Hospital (2022), a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. NRF-2016R1A2B4014552), and a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant No.: HI16C1127).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Lee S, Park SK. Data curation: Ko KP, Lee JE, Kim I, Jee SH, Shin A, Kweon SS, Shin MH, Park S, Ryu S, Yang SY, Choi SH, Kim J, Yi SW, Kang D, Yoo KY, Park SK. Formal analysis: Lee S. Funding acquisition: Park SK. Methodology: Lee S. Project administration: Park SK. Visualization: Lee S. Writing – original draft: Lee S. Writing – review & editing: Ko KP, Lee JE, Kim I, Jee SH, Shin A, Kweon SS, Shin MH, Park S, Ryu S, Yang SY, Choi SH, Kim J, Yi SW, Kang D, Yoo KY, Park SK.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Supplemental Materials are available at https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.22.299.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim IS, Ohrr H, Jee SH, Kim H, Lee Y. Smoking and total mortality: Kangwha cohort study, 6-year follow-up. Yonsei Med J. 1993;34(3):212–222. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1993.34.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park S, Jee SH, Shin HR, Park EH, Shin A, Jung KW, et al. Attributable fraction of tobacco smoking on cancer using population-based nationwide cancer incidence and mortality data in Korea. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:406. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanley JA. A heuristic approach to the formulas for population attributable fraction. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(7):508–514. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.7.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo KY, Shin HR, Chang SH, Lee KS, Park SK, Kang D, et al. Korean multi-center cancer cohort study including a biological materials bank (KMCC-I) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2002;3(1):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoo JY, Cho HJ, Moon S, Choi J, Lee S, Ahn C, et al. Pickled vegetable and salted fish intake and the risk of gastric cancer: two prospective cohort studies and a meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(4):996. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korean Statistical Information Service Population. [cited 2022 May 30]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&menuId=M_01_01#content-group (Korean)

- 7.Shin Y, Park B, Lee HA, Park B, Han H, Choi EJ, et al. Disease-specific mortality and prevalence trends in Korea, 2002–2015. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(4):e27. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quante AS, Ming C, Rottmann M, Engel J, Boeck S, Heinemann V, et al. Projections of cancer incidence and cancer-related deaths in Germany by 2020 and 2030. Cancer Med. 2016;5(9):2649–2656. doi: 10.1002/cam4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson SH, Hernandez R, Fledel-Alon A, Zhu L, Nielsen R, Bustamante CD. Simultaneous inference of selection and population growth from patterns of variation in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(22):7882–7887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502300102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang GT, Li B, Santos-Cortez RP, Peng B, Leal SM. Power analysis and sample size estimation for sequence-based association studies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(16):2377–2378. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn Y, Lee M, Yoo K, Chung J, Park B, Li Z, et al. Epidemiological investigation on cancer risk among radiation workers in nuclear power plants and residents nearby nuclear power plants in Korea. Seoul: Seoul National University; 2011. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kweon SS, Shin MH, Jeong SK, Nam HS, Lee YH, Park KS, et al. Cohort profile: the Namwon study and the Dong-gu study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):558–567. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J. Cancer screenee cohort study of the National Cancer Center in South Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014013. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jee YH, Emberson J, Jung KJ, Lee SJ, Lee S, Back JH, et al. Cohort profile: the Korean Cancer Prevention Study-II (KCPS-II) Biobank. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):385–386f. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo E, Lee Y, Mun E, Kim DH, Jeong Y, Lee J, et al. The effect of long working hours on developing type 2 diabetes in adults with prediabetes: the Kangbuk Samsung Cohort Study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2022;34:e4. doi: 10.35371/aoem.2022.34.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon C, Goh E, Park SM, Cho B. Effects of smoking cessation and weight gain on cardiovascular disease risk factors in Asian male population. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208(1):275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C, Choe EK, Choi JM, Hwang Y, Lee Y, Park B, et al. Health and Prevention Enhancement (H-PEACE): a retrospective, population-based cohort study conducted at the Seoul National University Hospital Gangnam Center, Korea. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019327. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y, Han BG, KoGES group Cohort profile: the Korean genome and epidemiology study (KoGES) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):e20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moon S, Kim YJ, Han S, Hwang MY, Shin DM, Park MY, et al. The Korea Biobank Array: design and identification of coding variants associated with blood biochemical traits. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1382. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37832-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun S, Oh K. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data linked Cause of Death data. Epidemiol Health. 2022;44:e2022021. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2022021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seong SC, Kim YY, Khang YH, Park JH, Kang HJ, Lee H, et al. Data resource profile: the National Health Information Database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):799–800. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seong SC, Kim YY, Park SK, Khang YH, Kim HC, Park JH, et al. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service-National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016640. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song M, Rolland B, Potter JD, Kang D. Asia Cohort Consortium: challenges for collaborative research. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(4):287–290. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulimani PS. Evidence-based practice and the evidence pyramid: a 21st century orthodontic odyssey. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paquette M, Kelecevic J, Schwartz L, Nieuwlaat R. Ethical issues in competing clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;14:100352. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shams-White MM, Brockton NT, Mitrou P, Romaguera D, Brown S, Bender A, et al. Operationalizing the 2018 World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) cancer prevention recommendations: a standardized scoring system. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1572. doi: 10.3390/nu11071572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans. 2004. [cited 2022 May 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK294452/

- 28.Taioli E, Bonassi S. Pooled analysis of epidemiological studies involving biological markers. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2003;206(2):109–115. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward M, Barzi F, Martiniuk A, Fang X, Gu DF, Imai Y, et al. Cohort profile: the Asia Pacific cohort studies collaboration. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1412–1416. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woodward M, Barzi F, Feigin V, Gu D, Huxley R, Nakamura K, et al. Associations between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and both stroke and coronary heart disease in the Asia Pacific region. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(21):2653–2660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Vestergaard M, Obel C, Cnattingus S, Gissler M, Olsen J. Cohort profile: the Nordic perinatal bereavement cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(5):1161–1167. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow AJ, Harvey CE, Milne RL, Pottinger CA, Vachon CM, Wilkens LR, et al. The National Cancer Institute Cohort Consortium: an international pooling collaboration of 58 cohorts from 20 countries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(11):1307–1319. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland B, Zhang X, Inoue M, Matsuo K, et al. Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):719–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hattersley AT, McCarthy MI. What makes a good genetic association study? Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1315–1323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meisner A, Kundu P, Chatterjee N. Case-only analysis of gene-environment interactions using polygenic risk scores. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(11):2013–2020. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ollier W, Sprosen T, Peakman T. UK Biobank: from concept to reality. Pharmacogenomics. 2005;6(6):639–646. doi: 10.2217/14622416.6.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taioli E, Bonassi S. Methodological issues in pooled analysis of biomarker studies. Mutat Res. 2002;512(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adhikari K, Patten SB, Patel AB, Premji S, Tough S, Letorneau N, et al. Data harmonization and data pooling from cohort studies: a practical approach for data management. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2021;6(1):1680. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v6i1.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.