Abstract

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is a key enzyme and mediator in the aetiology of high blood pressure (HBP) and hypertension. As one of the leading cause of untimely death worldwide, there is a lot of research and studies on the management and treatment of hypertension. The usage of medicinal plants in the management of hypertension as alternative to synthetic allopathic drugs is a common practice in folkloric and traditional medicine. Therefore, this study was aimed to investigate the ACE inhibitory activity of some medicinal plants which are commonly used in the treatment of HBP in southwestern part of Nigeria using extensive in-silico approach. Compounds identified in the plants through GC–MS technique, together with Lisinopril were docked against ACE protein. It was observed that only 40 of the compounds had binding affinity ≥ − 6.8 kcal/mol which was demonstrated by the standard drug (lisinopril). Interaction between the compounds and ACE was via conventional hydrogen, carbon hydrogen, alkyl, pi-alkyl, pi-carbon, and Van Der Wall bonds among others. Most of these compounds exhibited drug like properties, without violating majority of the physicochemical descriptors and Lipinski rule of 5. The ADMET evaluation revealed that only 2 compounds (cyclopentadecanone and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one) which were identified in Bacopa florinbunda plant were predicted non-toxic and thus were subjected to molecular dynamics and simulation with ACE. From the molecular dynamics and mechanics analysis, both cyclopentadecanone and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one showed high stability and inhibitory potentials when bound to ACE. Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one was more stable than lisinopril and cyclopentadecanone in the ligand–ACE complex; we therefore suggested its experimental and clinical validation as drug candidates for the treatment of hypertension.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-022-00135-z.

Keywords: Hypertension, Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, Medicinal plants, In-silico, Molecular docking, Dynamics, Simulation

Introduction

When statistics pegs the global burden of a disease to affect one out of 4 people, then it is a matter of concern and emergency that begs for rapt attention, intervention and study. Such is the case of hypertension characterized by persistent systolic and diastolic blood pressure values above 140 and 90 mm HG respectively (Zhou et al. 2021). Hypertension (HBP) ranks among the most prevalent and leading cause of mortality globally (Sorlie et al. 2014; Mills et al. 2016). If not properly treated and managed, hypertension can result to more fatal neuro and cardiovascular derangement states such as stroke, heart attack and ultimately death (Mills et al. 2016). Although, the pathophysiology of hypertension is hydra-headed, however, derangement in renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) are frequently implicated mediators in blood pressure elevation (Sparks et al. 2014). ACE is widely expressed in the plasma, body fluids, tissues, endothelial and epithelial cell types (Natesh et al. 2003). It mediates the conversion of angiotensin I (Ang I) to angiotensin II (Ang II) which is a potent vasoconstrictor peptide, mediating the indirect release of noradrenaline from postganglionic sympathetic fibers and aldosterone from the adrenal cortex via binding to its receptor (AT1 receptor) (Sembuling and Sembuling 2012). These series and cascade of signaling consequently leads to enhanced sympathetic activity, sodium retention (increased plasma osmolality) and elevated blood pressure aldosterone signaling (Sparks et al. 2014).

Other biological activity of ACE includes removal of the C-terminal dipeptide from bradykinnin and other peptides such as encephalin, neurotensin, and substance P, thus leading to alteration in their vasodilatory and natriuretic activities (Wang et al. 2016). Furthermore, increased and uncontrolled activity of this enzyme has been associated with the genesis of myocardial infarction, heart failure, metabolic syndrome, acute and chronic kidney disease, excessive generation of reactive oxygen, neuro inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque (Putnam et al. 2012). Administration of different classes of ACE inhibitors (ACE-i) like captopril, lisinopril and fosinopril are often the first line of treatment of elevated pressure and are also frequently prescribed in the management of cardiovascular disorders and diabetic nephropathy (Natesh et al. 2003; Messerli et al. 2018). Unfortunately, numerous undesired effects such as hypotension, fetal malformation and growth retardation, renal damage, rash and neutropenia and potentially fatal effect such as angioedema have been documented among patients receiving these drugs (Banerji et al. 2017). Similarly, resistance to ACE inhibitors is common in individuals of African descent, while prolonged irritating dry cough and non-specific upper respiratory symptoms due bradykinnin elevation is common among Asians (Tseng et al. 2010). In fact, most Asian medical practitioners have stopped prescribing ACE-i (Su et al. 2017).

Some natural products have been reported to have blood pressure lowering effects (Tabassum and Ahmad 2011). In traditional medicine, some herbs are popular, coveted and widely consumed for their presumed anti-hypertensive activity (Tabassum and Ahmad 2011). Many plants native to Nigeria and Sub-Saharan Africa have been cited and presumed to have cardio-protective and anti-hypertensive potentials (Obode et al. 2020). Nonetheless, the efficacy of some these medicinal herbs is relatively understudied and yet to be scientifically validated.

In-silico computational model is a cost effective, quick and rapid technique of analyzing large number of compounds and to predict predicting their pharmacological potential (Wadood et al. 2013). On this premise, this current study sought to investigate the ACE inhibitory activity and the possible toxicity profile of twelve commonly employed Nigerian and sub-Saharan medicinal plants (Hunteria umbellata, Vernonia amygdalina, Tridax procumbens, Chenopodium ambrosioides, Acalypha wilkesiana, Rauwolfia vomitoria, Bacopa floribunda, Kigelia africana, Parkia biglobosa, Parinari curatellifolia, Ficus exasperata and Rhus longipes in the management of cardiovascular disorders and hypertension via computational techniques.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant material

The plants were sourced in Ogbomoso town, Oyo state, Nigeria with the assistance of a traditional healer. The plants were further identified and authenticated by a taxonomist in the Department of Pure and Applied Biology, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Oyo State. Voucher numbers obtained for each plant were deposited at the University Herbarium.

Preparation of plant extracts

The plants were rinsed with clean water in order to remove the sandy particles and were thereafter air dried to constant weight for 3 weeks. The dried plant leaves and seed of Hunteria umbellata were pulverized and 100 g of each plant was soaked in 600 ml analytical grade ethanol at room temperature for 48 h. The solution was sieved twice with a muslin cloth and subsequently filtrated with Whatman filter paper. The filtrate was thereafter concentrated with a rotary evaporator (Hexa Pharma Chem, India).

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of the extracts

The GC–MS analysis was carried out on Agilent Technologies 789OA connected to mass spectrophotometer with triple axis detector (VL5675C) equipped with an auto injector (10 μl syringe). Chromatographic separation was done on capillary column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) using helium gas as the carrier at a constant flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. The sample injection size was 1 μl in a split mode with split ratio of 1:50. The column temperature was initiated at 35 °C for 300 s at a rate of 4 °C/min to 150 °C and was raised to 250 °C at the rate of 20 °C/min with a holding time of 300 s. The total elution time was 47.5 min. The compounds were identified by comparing the chromatogram of the separated components with the standard mass spectra from the National Institute of Standards and Technology Library (NIST), Maryland, USA.

Data source for computational and analysis

The structure of Angiotensin converting enzyme (PDB:1O8A), was obtained from the protein data bank (PDB), (https://www.rcsb.org/structure). The SDS format of each compounds from the plant extracts were obtained from PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and searched on cactus online smiles translator (https://cactus.nci.nih.gov) and subsequently downloaded as PDB file. Interacting ligands and water molecules were removed from the proteins, thereafter saved in PDB format for docking analysis.

Molecular docking and visualization of protein and compound complex

Docking of the proteins with the identified phytochemicals was carried out on Auto Dock Vina 1.5.6. On the Autodock tool, polar-H-atoms were first added to the proteins followed by Gasteiger charges calculation. The protein file was saved as pdbqt file and the grid dimensions were set. Docking calculations (Binding Affinity (DG) were then performed by using Vina folder Interactions between the ligand and proteins were visualized using discovery studio 2019.

Physicochemical, pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction of compounds

The canonical simplified molecular-input line entry system (SMILES) of the identified compounds from the plant extracts were obtained from PubChem data base (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and were queried on SWISS ADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/) and ADMET SAR webservers (http://lmmd.ecust.edu.cn/admetsar2/) to prognosticate the drug-likeliness, and possible toxicity of the compounds respectively.

Molecular dynamics simulation protocol

Simulation of systems is done using the Graphics Process Unit (GPU) version with an integrated PMEMD module force field FF14SB of AMBER 18 (Case et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2004) Previously reported in-house protocol for the MD simulation process was followed (Lawal et al. 2018; Olotu and Soliman 2018). The ligands/compounds were charged using the ANTECHAMBER module, a process known as parameterization. This was achieved using the atomic partial charge of the module to generate ligand recognized charged form of the system for subsequent analysis. The ACE protein was also parameterized using the FF14SB force field of the AMBER system. The system was neutralized by the addition of hydrogen atoms followed by topology file generation of the ligand, protein, and complex using the LEAP module integrated model of AMBER14. TIP3P orthorhombic box of 8 Å was employed in the solvation stage of the system (Case et al. 2005). Partial and full minimization of the system was employed which involves restraining the systems with an initial 2000 step with a potential energy of 500 kcal/mol followed by the full minimization of a further 1000 steps without any restraint. The system was subjected to heating in a stepwise range from 0 to 300 K for 50 ps. The system was then allowed to equilibrate for 500 ps with a temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 bar using the Berendenson barostat (Berendsen et al. 1984). The system was finally subjected to 150 ns MD simulation time frame using the NPT ensemble at 310 K with SHAKE constraint containing hydrogen at a 2 fs time step (Ryckaert et al. 1977).

Thermodynamic calculations

Thermodynamic calculations involve the use of the MMPB/SA method in analyzing the binding free energy of the ligands at the active site pocket of the receptors (Kollman et al. 2000). This estimates the residue energy contribution at the active site of the protein with its interaction with the ligands. The prediction of the intermolecular reactions that occur between drug compounds and their respective receptors in elucidating their therapeutic potential is used by computational scientists to explain the activities involved in drug design.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

Egas signifies the gas-phase energy of the system while Eint signifies the internal energy system, van der Waals, and electrostatic interaction forces are represented by Eele and Evdw. The solvation free energy represented by Gsol is divided into polar and non-polar forces. Polar solvation contribution is represented by Gpb, (ΔGele,sol) was derived from the Poisson–Boltzmann model of the MM/PBSA method, (ΔGnp,sol) is determined from Eq. (5) which estimates the surface tension proportionality constant γ at a value of 0.00072 kcal/mol. Å−2 and β also a constant. SASA known as the solvent accessible surface area (Å2) is estimated using the linear incorporation of pairwise overlaps (LCPO) model.

Results and discussion

Gas chromatographic–mass spectrophotometric (GC–MS) analysis

GC–MS analysis of the plant extracts revealed the presence of several compounds with Alcalypha wilkesiana, Rhus longipes and Chenopodium ambrosioides extracts having the highest representative compounds. The GC–MS spectrum (supplementary Figs. 1–12) and fragmentation pattern (supplementary Figs. 13–27) of some of the identified compounds are shown in the supplementary file.

Docking score of the ligands with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)

In this study, forty (40) compounds from nine (9) plants which demonstrated in-silico ACE-inhibitory activity and binding affinity of ≥ − 6.8 kcal/mol exhibited by lisinopril were selected. The chemical identification number of these forty compounds was obtained from PubChem website (Table 1). It was deduced that Chenopodium ambrosioides, Alcalypha wilkesiana, V. amygdalina and B. floribunda had the highest representative compounds (11, 9 and 7 respectively) with ACE inhibitory activities relative to lisinopril.

Table 1.

In-silico ACE binding affinity (kcal/mol) and inhibition constant (Ki) of the compounds

| S/N | Compound | Chemical ID | Plant | Binding affinity ΔG (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant Ki (µM) 10–6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound 1 | Cholesta-3,5-diene | 92,835 | Hunteria umbellata | − 7.9 | 1.97 |

| Compound 2 | 1,4-anthracenedione, 6-nitro- | 91,738,724 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compound 3 | 3,5-Dipiperonylidene-1-propyl-4-piperidone | 1,914,874 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.7 | 2.74 |

| Compound 4 | 12-Chloro-14-azatetracyclo[7.6.1.0(2,7)0.0(13,16)]hexadeca-1(15),2(7),3,5,9(16),10,12-heptaen-8-one | 46,949,298 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.8 | 2.32 |

| Compound 5 | Dehydroabietinol acetate | 71,232,440 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 6.8 | 12.27 |

| Compound 6 | Ergoline-8-methanol, 8,9-didehydro-6-methyl | 11,051 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compound 7 | N-Benzylisatoic anhydride | 520,756 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.1 | 7.45 |

| Compound 8 | Phenol, 4-(3,4-dihydro-2,2,4-trimethyl-2H-1-benzopyran-4-yl)- | 97,788 | Vernonia amygdalina | − 7.1 | 7.45 |

| Compound 9 | 1,2,5-Oxadiazol-3-amine,4-(3-methoxyphenoxy)- | 16,762,432 | Tridax procumbens | − 7.1 | 7.45 |

| Compound 10 | 1,2-Diethoxycarbonyl-dedimethylcolchicine | 540,951 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.4 | 4.52 |

| Compound 11 | 1,3,5-Triazine,2-(4-chlorophenylamino) | 636,192 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.6 | 3.24 |

| Compound 12 | 1,3,5-Triazine,2-methylamino-4,6 | 549,970 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.1 | 7.45 |

| Compound 13 | Morellinol | 5,364,072 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.3 | 5.34 |

| Compound 14 | 2,4-Diamino-6,8-bis[3,4-dichlorophenyl]-5,6-dihydro-8H-thiapyrano[4′,3′-4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidine | 541,181 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 8.0 | 1.66 |

| Compound 15 | Isomorellin | 12,313,004 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.4 | 4.52 |

| Compound 16 | 2H-1,4-Benzodiazepin-2-one,7-bromo-1,3-dihydro-5-phenyl-1-[4-(4-phenylpiperazin-1-yl)butyl] | 551,107 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compounds 17 | 3-(Antipyrin-4-yl)-5-(5-nitrosalicylidene) rhodanine | 1,894,639 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.0 | 8.80 |

| Compound 18 | 4-(5-Methoxyindol-3-ylmethyleneamino)-2,3-dimethyl-1-phenyl-3-pyrazolin-5-one | 544,830 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.2 | 6.31 |

| Compound 19 | Benzoic acid, 4,4,6a,8a,11,11,14b-heptamethyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,6a,6b,7,8,8a,9,10,11,12,12a,14,14a,14b-eicosahydropicen-3-yl ester | 571,104 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.2 | 6.31 |

| Compound 20 | Daidzein,O,O′bis(pentafluoropropionyl) | 91,710,836 | Chenopodium ambrosioides | − 7.8 | 2.32 |

| Compound 21 | 1,3,5-Triazine,2,4-bis(2,2,2-trifluoro-1-trifluoromethylethoxy)-6-(2-methoxyphenylamino) | 550,632 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 7.6 | 3.24 |

| Compound 22 | Isomorellinol | 541,425 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 7.3 | 5.34 |

| Compound 23 | 1H-Isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione,5,5′-[(1-methylethylidene)bis(4,1-phenyleneoxy)]bis[2-methyl | 108,586 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 7.0 | 8.80 |

| Compound 24 | 2,3,4-Pentanetrione,3-[(2,3-dihydro-1,5-dimethyl-3-oxo-2-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)hydrazone] | 135,439,865 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compound 25 | 4-(5-Methoxyindol-3-ylmethyleneami no)-2,3-dimethyl-1-phenyl-3-pyrazo lin-5-one | 544,830 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 8.2 | 1.19 |

| Compound 26 | Ethanone,1-[4-[4,6-bis(2,2,2-trifluoro-1-trifluoromethylethoxy)-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl]amino]phenyl | 534,216 | Acalypha wilkisiena | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compound 27 | Isoindole, 1-(hydrazinedicarboxylic acid, diethyl ester)-3-(hydrazin edicarboxylic acid, dimethyl ester)-2-(2,3-dimethylphenyl)- | 533,811 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 6.8 | 12. 27 |

| Compound 28 | Isonipecoticacid,N-(2,5-di(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl)-,dodecylester | 91,744,033 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 6.9 | 10.39 |

| Compound 29 | 2,5-Cyclohexadiene-1,4-dione,2,3,5,6-tetrakis(4-methylphenoxy)- | 19,883,966 | Acalypha wilkesiana | − 7.4 | 4.52 |

| Compound 30 | 2-Pyrimidinamine,4-[4-[3-[1-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperidin-4-yl]propyl]piperidino]-6-methyl-N-(5,6-dichloro-1,3(1H)-benzimidazol-2-yl) | 477,228 | Rhus longipes | − 6.8 | 12.27 |

| Compound 31 | 1,3,5-Triazine, 2-(4-chlorophenylamino)-4,6-bis(2,2,2-trifluoro-1-tr ifluoromethylethoxy) | 550,635 | Rhus longipes | − 7.6 | 3.24 |

| Compound 32 | 4-(2-Chloro-1,1,2-trifluoro-2-trifluoromethoxy-ethylsulfanyl)-1,5-dimethyl-2-phenyl-1,2-dihydro-pyrazol-3-one | 545,031 | Rhus longipes | − 6.8 | 12.27 |

| Compound 33 | Apigenin | 5,280,443 | Rhus longipes | − 7.1 | 7.45 |

| Compound 34 | Benzenamine,4-trifluoromethoxy-N-[1-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(4-trifluoromethoxyphenylimino)-1-propenyl] | 5,380,090 | Rhus longipes | − 7.4 | 4.52 |

| Compound 35 | Cholest-5-en-3-ol(3.beta) | 5997 | Bacopa forinbunda | − 8.5 | 0.73 |

| Compound 36 | Cyclopentadecanone | 10,409 | Bacopa forinbunda | − 7.5 | 3.83 |

| Compound 37 | Heptadecanolide | 3,639,916 | Bacopa forinbunda | − 8.4 | 0.86 |

| Compound 38 | Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one | 7984 | Bacopa forinbunda | − 7.9 | 1.97 |

| Compound 39 | trans-4-Dimethylamino-4-methoxychalcone | 5,378,142 | Rauwolfia vomitoria | − 8.2 | 1.19 |

| Compound 40 | Pyrazolo[5,1-c][1,2,4]triazine-3-carboxylicacid | 2,778,429 | Ficus exasperata | − 7.0 | 8.80 |

| 41 | Lisinopril | 5,326,119 | Standard drug | − 6.8 | 12.27 |

Lisinopril is a long lasting, lipid soluble anti-hypertensive drug belonging to the carboxyl group binding classes of ACE inhibitors (O'Gara et al. 2013). Compounds 35 (Cholest-5-en-3-ol(3.beta) and 37 (heptadecanolide) identified in B. florinbunda exhibited the highest inhibitory activities with binding affinities of − 8.5 kcal/mol and − 8.4 kcal/mol respectively. Similarly, compounds 39 (trans-4-Dimethylamino-4-methoxychalcone) and 25 (5-[m-Trifluromethylanilino]-6-methoxy-8-[4-phthalimido-1-methylbutylamino] quinolone) which were identified in Rauwolfia vomitoria and Acalypha wilkesiana extract demonstrated lower binding energy, − 8.2 kcal/mol respectively for ACE (Table 1).

Interaction of the compounds with amino acid residues of ACE

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) also known as kinase II is coded by the ACE gene (chromosome 17q23) and made up of 1306 amino acid residues ACE is a zinc metallo-endopeptidase with two catalytic domains (N- and C-domains) which is divided into three binding pockets vis-à-vis, S1 (Ala354, Glu384, and Tyr523), S1′ (Glu162) and S2 (Gln281, His353, Lys511, His513, and Tyr520) (Pan et al. 2012; Wong 2016).

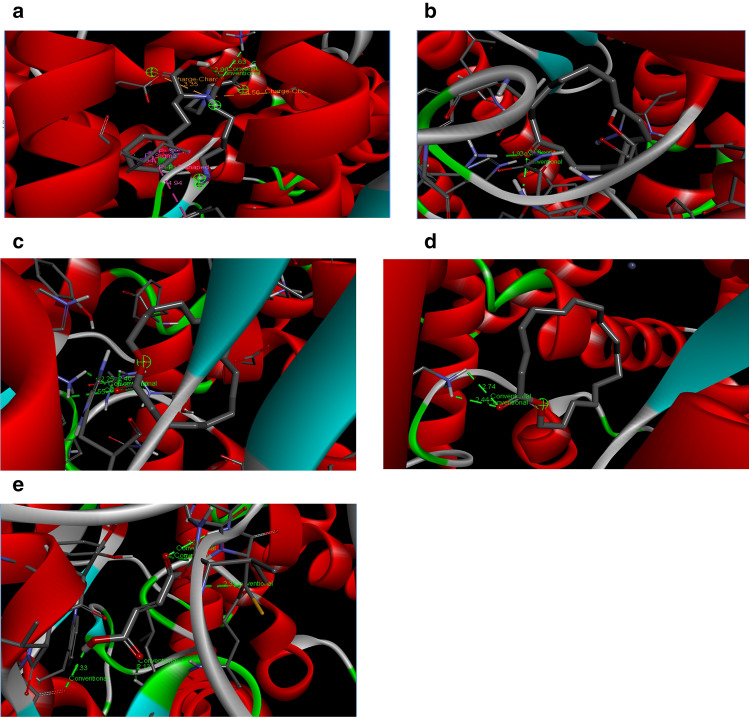

The compounds with in-silico ACE-i activity in this study bonded with some amino acid residues of the ACE via different bonds (Table 2). The 3D-complex of lisinopril and some of the best posed compounds are depicted in Fig. 1a–e. For example, lisinopril and many of the compounds interacted prominently with TRP 59, ARG 124 and GLU 123. This phenomenon has been hitherto discovered in the study of Tahir et al. (2020); however, these residues are not part of ACE catalytic sites. Compound 35 (Cholest-5-en-3-ol(3.beta)) with the highest affinity for ACE was linked via alkyl (AB) and pi-alkyl (PiB) with LYS360, LYS62, VAL518, LEU140, LEU81, LEU199, LEU82 residues (Table 2). On the other hand, some compounds interacted with amino acid residues that make up the ACE active site. For instance, cyclopentadecanone, heptadecanolide and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one identified in B. floribunda plant interacted with residues GLU411, LYS511, TYR520, and TYR523 which are amino acids present in the active site of the protein (Natesh et al. 2003). These amino acids are also in close proximity with ARG 522 which is an important target amino acid targeted by ACE inhibitors and is also involved in chloride ion dependent activation of ACE (Liu et al. 2001; Natesh et al. 2003). Our finding is similar to the previous submission of Ahmad et al. (2019) on in-silico ACE inhibition by phenolic agents from Peperomia pellucida (L) Kunth herb. Furthermore, the lower inhibition constant (Ki) (0.86 × 10–6 µM) exhibited by compound 37 (heptadecanolide) might be due to its interaction with amino acids HIS 353 and SER 355 (Table 2). Interestingly, amino acid HIS 353 and SER 355 have been reported as vital coordinating sites and motifs for zinc ion dependent ACE catalysis and might be responsible for the stability of ligand–enzyme complex (Deng et al. 2018; Ma et al. 2018; Tahir et al. 2020).

Table 2.

Bonding and interaction of the compounds with amino acid residues of ACE

| Compounds | Interacting amino acid residues | Bond type |

|---|---|---|

| Compound 1 | TRP 59, TYR 62, PHE 570, LYS 118, ILE 88, ARG 124, MET 223 | AB, PiB |

| Compound 2 | ARG124, ILE88, GLU123, TRP59 | VWF, PiA, PiB, PPTS |

| Compound 3 | TRP59,GLU123, GLU403 | CHB, PiA, PPS |

| Compound 4 | ILE88,TRP59,GLU123, THR92 | VWF, PiA, PPTS, PPiB |

| Compound 5 | ARG124,TRP59,GLU123,GLU40, ILE88 | CHB, PiB, PPTS, PiA, AB |

| Compound 6 | GLU123,TRP59,ILE 88,TYR62 | CHB,PiA,PPS,PiB,AB |

| Compound 7 | ILE88,TYR62,ALA89,TRP59,ARG124,GLU123 | PiA, PiS,PPS,PiB |

| Compound 8 | GLU123, ARG124, ILE88,TYR62 | CHB, PiA, PiB, PPS |

| Compound 9 | GLU 143, ASN 70, ASN 136, ASN 85, ARG 124, LEU 139 | CoHB, CHB, PiB, PiA, PiC, UDD |

| Compound 10 | THR123, GLU123, ARG124, TYR360,GLU104 | AC, CHB, CoHB |

| Compound 11 | TYR62, ASN85, MET223, PRO407, GLU403,ILE88,ARG124,TRP59,GLU123, LYS118 | CoHB, HB, PiB, AB, PiA |

| Compound 12 | TYR360, GLU403, TRP59, GLU123, ILE88, TYR62, ARG124 | CoHB, HB, PiB, PiA, AB |

| Compound 13 | TRP59, LYS118, GLU123 | CoHB, PiS |

| Compound 14 | TRP59, ILE88, TYR62, GLU123, MET223, LYS118, PHE570 | PiC,PiB, PiA, PiS, PiSf, AB |

| Compound 15 | TRP59, TRP220, LYS118, GLU123 | CoHB, CHB, PiS, UDD |

| Compound 16 | TYR62, GLU403, GLU123, MET223, PHE391, HIS410 | AC, PiS, AB, PiB |

| Compounds 17 | LYS118 | CoHB |

| Compound 18 | GLU123, ARG124, TRP59 | CoHB, CHB, PiB |

| Compound 19 | ILE88, TYR62, LYS117, LYS118, MET223 | CoHB, AB, PiB |

| Compound 20 | ASN85, SER517, ARG124, GLU123, TRP220, MET223 | CoHB,HB, AB, PiB |

| Compound 21 | LYS118, ARG124, GLU123, GLU403, TRP59, TYR62, ILE88 | CoHB, AB, HB, PiA, PiB |

| Compound 22 | TRP59, GLU123 | CoHB, PiS |

| Compound 2 | TRP287, ASP300 | AC, PiB |

| Compound 24 | GLU123, LYS118, TYR62, ILE88 | CoHB, PiS, AB |

| Compound 25 | GLU123, GLU403, ILE88, TYR62, ASN85, ARG124 | AC, HB, AB, PiB |

| Compound 26 | GLY64, THR 149, GLU151, SER148, GLU155, VAL56, PRO160, GLN57, GLY60, ALA161 | VWF, CoHB, CHB, HF, PiA, PiS, AB, PiB |

| Compound 27 | LEU375, TYR287, LYS 449 ASP300, SER298, PRO287 | CoHB, CHB, AB, PiB |

| Compound 28 | GLU123, MET223, ILE88, TRP59 | HB, PiB, AB |

| Compound 29 | GLU123, GLU403, TRP59, TYR62, ILE88, MET:223, PHE:570, LYS:118 | AC, AB, PiB, CoHB |

| Compound 30 | ASP288, VAL291, ASP300, | CHB, PiA, AB |

| Compound 31 | ILE88,TRY62,MET223,PRO407,GLU403,LYS118,GLU123,TRP59,ARG124 | CHB, PiA, PiB, AB, HF |

| Compound 32 | LYS118, GLU123, TRP220, TRP59 | PiA, AB, HB, CHB, CoHB |

| Compound 33 | ASN85, LYS118, GLU123 | CHB, CoHB |

| Compound 34 | LYS118,GLU403,TRP59 | CoHB, CHB, HF |

| Compound 35 | LYS360, LYS62, VAL518, LEU140, LEU81, LEU199, LEU82 | AB, PiB |

| Compound 36 | LYS511, GLN281, TYR520 | VDW, CoHB |

| Compound 37 | TYR523, HIS513, GLU411, HIS387, HIS353, PHE391, ASP358, TRP357, ALA354, SER355, PHE512, VAL518, ASN66 | VDW, CoHB |

| Compound 38 | ASP288, TYR287, SER284, LYS449, LEU375, GLU376, THR302, ASN374, ASN285, ALA170, THR171, ARG173 | VDW, CoHB |

| Compound 39 | PRO407, PHE570, MET223, LYS118, LYS117 | CHB, PPTs, PiB |

| Compound 40 | LYS 118, ILE 88, ARG 124, ALA 89, GLU 123 | CoHB, AB, PiB, PiA |

| Lisinopril | GLU123, ARG124, ILE88, TYR62 | AC, CoHB, UDD, PiS, UPP, Pi-Pi T-shaped |

Fig. 1.

a 3D complex of ACE and lisinopril. b 3D complex of ACE and cyclopentadecanone. c 3D complex of ACE and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one. d 3D complex of ACE and heptadecanolide. e 3D complex of ACE and fumaric acid

Pharmacokinetics and ADMET profile of compounds with ACE inhibitory activities

Major benchmarks considered in the development of a new drug or lead compound are its bio-availability and tendency to be easily absorbed, distributed, metabolized and excreted (ADME) by the biological system irrespective of its potency and efficacy (Bohnert and Prakash 2012). In this context, certain physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties must not be violated since drug design and toxicity are dependent on it. Lipinski rule of 5 among others such as Egan, Veber and Ghose are the commonly used yard stick in the evaluation of drug likeliness (Lipinski et al. 2001). The major emphasis is on the ability of a compound not violating more than two of the physicochemical parameters such as molecular weight (MW) not > 500 g/mol, hydrogen bond acceptor (O plus N atoms) < 10, hydrogen bond donor (OH plus NH groups) < 5, rotatable bond < 10, and lipophylicity (Mlog P) < 4.5 (Veber et al. 2002). Molecular size (MW) and hydrogen bonding are good indicators to predict the permeability and route absorption of compounds, while lipophylicity (M Log P) considers the interaction of a ligand with lipid bilayers and also measures the differences between hydrophobicity and polarity of a compound (Veber et al. 2002). It has also been reported that increased lipophylicity aids excessive movement of drug from the blood into the liver cells, leading to elevated level of reactive metabolites cross-talking with the membranes of the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum with consequences such as immune dysfunction and oxidative stress (Toyoda et al. 2011; Kloting and Bluher 2014). More importantly, physicochemical descriptors are crucial in the permeability of a therapeutic agent across the blood brain barrier, membrane of tissues and the gastrointestinal tract (Veber et al. 2002). In this study, most of the compounds showed drug like properties with none violating more than two of the Lipinski rules and physicochemical descriptors (Table 3). Only 14 (35%) and 9 (22.5%) of the 40 studied compounds failed one or two physicochemical parameters respectively with molecular weight, hydrogen bond acceptor and lipophylicity being the most breeched parameters. Notable examples are compounds 11 (1, 3, 5-triazine, 2-(4-chlorophenylamino) and 12 (1, 3, 5-triazine, 2-methylamino-4, 6-) with MW (642.67 and 546.16 g/mol respectively) > 500 g/mol and hydrogen bond acceptor atoms (21) > 10 respectively. Similarly, compound 23 (1H-Isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione,5,5'-[(1-methylethylidene)bis(4,1-phenyleneoxy)]bis[2-methyl) had a MW and higher lipophylicity value of 546.55 g/mol and 4.46 respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties and lipinski violation of the compounds

| Compound | Molecular weight | Hydrogen-bond acceptors | Hydrogen bond donors | Rotatable bonds | Mlog P | Lipinski violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 368.64 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7.3 | 1 |

| 2 | 253.21 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0.74 | 0 |

| 3 | 405.44 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 2.61 | 0 |

| 4 | 253.68 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2.72 | 0 |

| 5 | 328.49 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 4.89 | 1 |

| 6 | 310.43 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2.85 | 0 |

| 7 | 253.25 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2.77 | 0 |

| 8 | 268.35 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3.54 | 0 |

| 9 | 207.19 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 0.79 | 0 |

| 10 | 515.51 | 10 | 1 | 12 | 1.05 | 2 |

| 11 | 642.67 | 21 | 1 | 10 | 5.24 | 2 |

| 12 | 546.16 | 21 | 1 | 9 | 3.7 | 1 |

| 13 | 546.65 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 2.5 | 1 |

| 14 | 528.3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5.39 | 2 |

| 15 | 544.63 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 2.42 | 1 |

| 16 | 531.49 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 3.9 | 1 |

| 17 | 468.51 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1.78 | 0 |

| 18 | 360.41 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2.53 | 0 |

| 19 | 516.8 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 7.8 | 2 |

| 20 | 546.27 | 16 | 0 | 9 | 3.39 | 1 |

| 21 | 534.26 | 18 | 1 | 11 | 2.7 | 1 |

| 22 | 546.65 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 2.5 | 1 |

| 23 | 546.57 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 4.46 | 2 |

| 24 | 314.34 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1.06 | 0 |

| 25 | 360.41 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2.53 | 0 |

| 26 | 546.27 | 18 | 1 | 11 | 2.57 | 1 |

| 27 | 541.55 | 8 | 2 | 15 | 3.76 | 2 |

| 28 | 523.55 | 9 | 0 | 16 | 5.72 | 2 |

| 29 | 532.58 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 3.26 | 1 |

| 30 | 546.53 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 3.72 | 1 |

| 31 | 538.68 | 17 | 1 | 10 | 3.5 | 1 |

| 32 | 420.76 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 3.4 | 0 |

| 33 | 270.24 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0.52 | 0 |

| 34 | 545.27 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 4.67 | 2 |

| 35 | 442.72 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 6.7 | 1 |

| 36 | 224.38 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.67 | 0 |

| 37 | 268.43 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4.04 | 0 |

| 38 | 254.41 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 0 |

| 39 | 281.35 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 2.9 | 0 |

| 40 | 192.17 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0.57 | 0 |

| Lisinopril | 405.49 | 7 | 4 | 13 | − 1.46 | 0 |

Early and accurate in-silico toxicity predictions based on metabolism and interaction of lead compounds with certain proteins and receptors are highly desirable to identify and nullify potentially toxic drug candidates (Wang 2009; Bohnert and Prakash 2012). Toxicity is an important factor to be considered in medicinal chemistry and drug design (Parasuraman 2011; Myatt et al. 2018). Promising and numerous potent pharmacological agents and formulations have failed developmental stages and clinical trials due to their unfavorable toxicological profile (Norris et al. 2008). Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is an unwanted effect caused by administration of drugs, herbal preparation and other foreign compounds (Villanueva-Paz et al. 2021). This phenomenon is one of the leading causes of hepatic dysfunction and is responsible for the withdrawal and attrition of many pharmaceutical agents by drug and food regulatory agencies globally (Watkins 2011; Pandit et al. 2012). The liver is arguably the most important organ of the body, heavily saddled and involved with the regulation and organization of many metabolic pathways, drug detoxification and protein synthesis (Singh et al. 2016). The liver is vulnerable to drug induced damage, dysregulated hepatocyte bio-signaling and these have been strongly linked to oxidative stress, mutagenesis and carcinogenicity (Norris et al. 2008). During bio-transformation of some drugs, metabolites and electrophilic intermediate generated can form covalent adduct with DNA and sulfhydryl group of amino acids of important proteins (Coleman et al. 2007; Leung et al. 2012).

The toxicity profiles of the test compounds in this study are highlighted in Table 4. Only 14 (35%) of the compounds together with lisinopril were prognosticated not harmful to the liver, while 37 compounds (92.50%) showed no cancer risk. More so, thirty-four (85%) compounds were predicted to be non-mutagenic as they were negative to Ames test (Table 4).

Table 4.

ADMET profile of the evaluated compounds

| Compounds | Ames | BBBP | Carcinogenicity | Cyp1A2 inhibitor | Cyp2C19 inhibitor | Cyp2C9 inhibitor | Cyp2D6 inhibitor | Cyp3A4 inhibitor | DILI | hERG blocker | GI absorption | P-gp inhibitor | P-gp substrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 3 | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 4 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 5 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 6 | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| 7 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 8 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 10 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 11 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 12 | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 13 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 14 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 15 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 16 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| 17 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| 18 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 19 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| 20 | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 21 | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 22 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 23 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 24 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 25 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 26 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 27 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| 28 | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 29 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 30 | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 31 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 32 | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 33 | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| 34 | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 35 | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 36 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 37 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 38 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 39 | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| 40 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Lisinopril | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

−, negative: + positive

Ames test is a widely used bacteria assay to evaluate the carcinogenic and DNA damaging potential and effect of many test compounds (Vijay et al. 2018).

The possibility of a drug or compound to disrupt cardiac hemostasis and metabolism is of utmost consideration in drug discovery (Hanser et al. 2019; Garrido et al. 2020). The hERG ion channel is a protein encoded by the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) which dictates the permeability of K+ ions and repolarization of heart cells (Priest et al. 2008). Mutation and inhibition of this protein is associated with arrhythmia, long QT syndrome, Torsades de Pointes and cardiac arrest (Keating and Sanguinetti 2001). Eighteen (18) compounds including cholesta 3,5-diene, 4-epidehydrobietinol and trans-4-dimethylamino-4-methoxychalcone among others in this study were predicted positive for the inhibition of potassium ion channel and might not be drugable, while compounds 35–38 and lisinopril among others are negative inhibitors of this cardiac ion channel. Cytochromes P450 are superfamily (Cyp 1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, 3A4) of haemoprotein enzymes responsible for metabolism and bio-activation of foreign compounds including alcohol, drugs, environmental pollutants and chemicals (Esteves et al. 2021). Apart from their pharmacological indispensability, they have physiological importance and are integral in the synthesis of neuro transmitters, steroid hormones, bile acids and prostaglandins (Zanger and Schwab 2013; Guengerich et al. 2016; Manikandan and Nagini 2018). Therefore, identifying substrates and more importantly inhibitors of Cyp isoenzymes is of toxicological and pharmacological importance. It is predicted from this study that few of the compounds are inhibitors of one or more of the P450 isoenzymes, while majority are non-inhibitors. For instance, Cyp1A2, Cyp2C9 and Cyp2C19 could be inhibited by apigenin and isomorellin. As previously reported, inhibition of these enzymes in-vivo has negative clinical consequences and is hypothesized to be mediated through mechanisms including competition for the active site by substrates and binding to the heam moiety (Correia and Hollenberg 2015; Gentry et al. 2019). According to the pharmacokinetic prediction, most of the ligands can easily permeate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The GIT is the most important extra-hepatic site for drug metabolism. Thus, orally administered drugs and compounds must have requisite solubility and permeability to cross epithelial or mucosal cell walls through passive, facilitated diffusion, or active transport into the systemic circulation (Di et al. 2020). The role of ACE in the etio-pathogenesis of some neurovascular disorders such as stroke and Alzemier’s is well defined in literature (Möllsten et al. 2008). The treatment of these ailments is difficult due to complexity of the BBB and impermeability of many compounds through it (Alavijeh et al. 2005). The BBB is a vital interface segregating the brain from systemic circulation, and is the major entry route for therapeutic compounds to the central nervous system (Alavijeh et al. 2005). Compounds that cross the BBB are lipophilic and enter through active mechanism (Alavijeh et al. 2005). Interestingly, most of the compounds (38) in this study were predicted to have BBB penetrating potential. Thus, they might be a therapeutic agent and candidate in the treatment of high blood pressure-induced neurological disorders. Only compound 23, apigenin and lisinopril were predicted impermeable through the BBB.

Phosphorylated glycoproteins (P-gp) belong to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) group of membrane transporters and are found in all tissues (Dean et al. 2001). Studies have consistently linked P-gp with multi drug resistance (MDR) due to their drug effluxing capacity in the cells (Sun et al. 2018). This study indicates that thirty two compounds together with lisinopril are non P-gp substrates, thus suggesting that they might have prolonged half-life and increased cellular bioavailability. Altogether, it was deduced that among the compounds with ACE inhibitory potential, compounds 36, 37 and 38 (cyclopentadecanone, heptadecanolide and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one respectively) are deemed drugable as they did not violate any toxicity and physicochemical parameters and thus were shortlisted for molecular dynamics and simulation with ACE protein.

Molecular dynamics simulation (MD)

To further asses the stability of the ligands in complex with ACE, we perform the dynamics simulation as a function of time up to 150 ns. From the MD trajectories, stability was affirmed by computing the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of Gyration (ROG), and Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA).

Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

The RMSD plot usually explains the conformational stability of the ligand–receptor complex in which the stability is inversely related to RMSD value. Lower RMSD values will indicate a stable conformation of protein–ligand complex (Ray et al. 2022).

Figure 2 is the RMSD plot revealing the conformational behavior of the protein (ACE) both in the presence and absence of the ligand. Higher RMSD value is an indication of high atomic movement across the C-α atom backbone of the protein (Olotu and Soliman 2018). From the result, obvious stability of protein was noticed upon binding to lisinopril cyclopentadecanone, and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one and the stability was also sustained throughout the trajectory. The unbound ACE with a mean RMSD value of 1.73 ± 0.27 Å had lower stability than the bound complexes viz; cyclo-ACE (1.60 ± 0.22 Å), Lisi-ACE (1.42 + 0.16 Å) and Oxac-ACE (1.29 ± 0.20 Å) complexes. Oxac-ACE complex showed more stability than the standard whereas; cyclo-ACE was less stable relative to lisinopril that was used as standard. Stable conformation of the complexes was noticed throughout the course of the trajectory. In tandem with previous observation, the selected compounds showed stable conformity synonymous to those reported for fucoxanthin a plant compound isolated from the ethyl acetate fraction of Sargassum wightii, Gly-Glu-Phe (GEF) tripeptide, and some di- and tri-peptides (Qi et al. 2018; Raji et al. 2020; Yan et al. 2020).

Fig. 2.

Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of lisinopril, cyclopentadecanone, and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one–ACE complex. Unbound ACE (black), CYCLO-ACE (red), LIS-ACE (green) and OXAC-ACE (blue)

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF)

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis examines the residual conformational change. It measures individual residue fluctuation that corresponds to the ligand-binding effect on the Cα atoms residues of the protein. Regions of protein that records very high RMSF values correspond to the loop regions that might be involved in ligand binding and conformational alterations (Lee et al. 2012). In Fig. 3, the roots mean square fluctuation of lisinopril, cyclopentadecanone, and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one–ACE complexes were depicted. As indicated in the result, there are five major peaks for the complexes and ACE corresponding to residues 60–95, 110–120, 245–280, and 570 respectively, which were similarly reported by Raji et al. (2020) to belong to the loop region. Overall, the level of residues fluctuation in the cyclopentadecanone–ACE systems was relatively higher with average value of 1.04 Å as against 0.96 Å in the unbound ACE system. On other hand oxacycloheptadecan-2-one-ACE and Lisinopril–ACE, complex with average RMSF fluctuation values of 0.92 Å and 0.93 Å respectively were lower than the unbound ACE, indicating that their interactions with the protein exhibited less fluctuation of residues than the unbound ACE.

Fig. 3.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of lisinopril, cyclopentadecanone, and Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one–ACE complex. Unbound ACE (black), CYCLO-ACE (red), LIS-ACE (green), and OXAC-ACE (blue)

Solvent accessible surface analysis (SASA)

The SASA metrics gives indication of the changes in the surface of protein upon binding to a drug candidate. The hydrophobic residues of the protein are commonly responsible for the increments in SASA values. During simulation trajectory, SASA measurement can reflects the mobility of a ligand across the hydrophilic and hydrophobic core of the protein. As clearly observed in this study, cyclopentadecanone (23,470.56 ± 647.17 A2) and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one (24,122.97 ± 593.80 A2) exhibited more rigidity in the protein–ligand complex with lower SASA values than lisinopril (25,296 ± 597.12 A2) and the unbound ACE (24,707.40 ± 751.05 A2) (Fig. 4) (Qi et al. 2018). For the two plant compounds, downward trend in the SASA metric was observed throughout the simulation trajectory. It is therefore plausible to conclude that there was little to no contraction and expansion for the complexes during the simulation time (Rakib et al. 2021).

Fig. 4.

Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of lisinopril, cyclopentadecanone, and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one–ACE complex. Unbound ACE (black), CYCLO-ACE (red), LIS-ACE (green), and OXAC-ACE (blue)

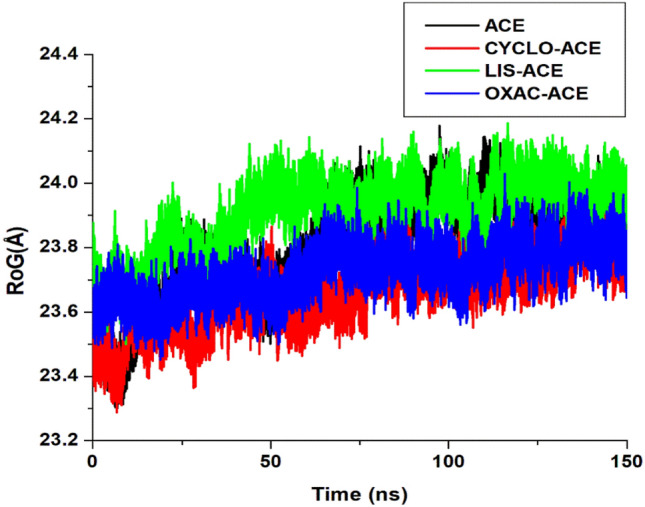

Radius of gyration (ROG)

The ROG plot is a measure of compactness and indicates structural changes in a protein (Zhou et al. 2012; Raji et al. 2020). Equilibration of the ROG spectrum during the simulation trajectory could indicate if a protein is stably folded or not and abrupt fluctuation of the spectrum could identify non-compact system (Khoutoul et al. 2016). In this study, the ROG was calculated to analyze structural changes of ACE when bound and unbound with the inhibitors. In Fig. 5, the average values were 23.80 ± 0.16 Å, 23.66 ± 0.11 Å, 23.90 ± 0.11 Å and 23.77 ± 0.12 Å for ACE, cyclo-ACE, Lisi-ACE, and Oxac-ACE respectively. Similar to the report of Raji et al. (2020), in which fucoxanthin had ROG value of approximately 23 Å, the molecules when bound to ACE exhibits high compactness. It was obvious from the ROG values that ACE exhibits more stability when bound by cyclopentadecanone and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one. Fluctuation was larger for the Lisi-ACE complex than the cyclo-ACE and Oxac-ACE complexes respectively.

Fig. 5.

Radius of Gyration (ROG) of lisinopril, cyclopentadecanone, and Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one–ACE complex. Unbound ACE (black), CYCLO-ACE (red), LIS-ACE (green), and OXAC-ACE (blue)

Binding free energy decomposition analysis using MM-PBSA

The result of the molecular dynamic simulation is not satisfactory enough to establish stability of the ligand–receptor complex. It is therefore important to dive deeper into the molecular mechanism that contributes to the stability of the test compounds. In this regard, we perform a free energy decomposition analysis using the MM-PBSA method (MacLeod-Carey et al. 2020) and the result is presented in Table 5. The MM-PBSA calculation is quintessential to describe the nature of interaction at the active site pocket of the proteins and this information could be used for the prediction of pharmacological properties derived from such drug candidates. Obviously, more favorable binding energies viz solvation (ΔGsol) and unfavourable electrostatic (ΔEele) contributions of oxacycloheptadecan-2-one and cyclopentadecanone are all observed in Table 5. Overall, the total binding energies (ΔGbinds) of cyclo-ACE, Lisi-ACE, and Oxac-ACE was − 22.94 kcal/mol, − 34.94 kcal/mol and − 46.88 kcal/mol, respectively. This observation provide credence to the previous affirmation that oxacycloheptadecan-2-one is more stable than the reference lisinopril and in fact than cyclopentadecanone. At the active site pocket of ACE, per residue decomposition analysis was further employed to validate the total binding energies of the complexes. Electrostatic interaction was most prominent among the interacting residues of the reference lisinopril (Fig. 6b) and less prominent among the residues of oxacycloheptadecan-2-one (Fig. 6c). In all the complexes, residues Tyr 484, HIS 470, Glu 372, Glu 345, HIS 344, SER 316, ALA 315 and HIS 314 was found in common and none of this residues is part of the active site residue. In the oxacycloheptadecan-2-one complex, most of these residues contributed immensely to the total binding energies and van der Waal interaction in the complex. It is noticeable from the dynamics study that oxacycloheptadecan-2-one exhibited some inhibitory stability against ACE and therefore can serve as important drug candidate in the treatment of hypertension.

Table 5.

Total free binding energy contributions of the ACE–ligand complexes

| Complexes | ΔEvdW (kcal/mol) | ΔEele (kcal/mol) | ΔGgas (kcal/mol) | (kcal/mol) | ΔGbind (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYCLO-ACE | − 31.28 ± 4.64 | − 11.30 ± 8.81 | − 42.57 ± 11.12 | 19.63 ± 8.12 | − 22.94 ± 4.30 |

| LISI-ACE | − 37.04 ± 4.21 | − 575.55 ± 46.47 | − 612.59 ± 47.39 | 577.65 ± 36.44 | − 34.94 ± 13.45 |

| OXAC-ACE | − 28.36 ± 3.71 | − 33.42 ± 5.18 | − 61.79 ± 4.64 | 14.91 ± 11.17 | − 46.88 ± 9.89 |

Fig. 6.

a Per-residue energy contribution of ACE–cyclopentadecanone complex. b Per-residue energy contribution of ACE–lisinopril complex. c Per-residue energy contribution of ACE–oxacycloheptadecan-2-one complex

Conclusions

In this study, highest number of phytochemicals was profiled from Alcalypha wilkesiana, Rhus longipes and Chenopodium ambrosioides. Forty-(40) of the compounds exhibited affinity for ACE in comparison with lisinopril. Four of the plants viz. Chenopodium ambrosioides, Alcalypha wilkesiana, V. amygdalina and B. floribunda had the highest representative of compounds, which showed potent inhibitory activity against ACE. Among all the compounds, cyclopentadecanone, heptadecanolide and oxacycloheptadecan-2-one demonstrated the highest affinity for ACE. More importantly, heptadecanolide interacted with two important amino acid residues involved in the Zn ion motifs of ACE, which are also germane for ACE catalysis. Overall, this study profiles some potential plant compounds with inhibitory potentials against ACE. Most of the potential ACE inhibitors demonstrated drug like properties with no linpiski violation and good pharmacokinetic properties. Oxacycloheptadecan-2-one out performed lisinopril and cyclopentadecanone as potential ACE inhibitor with the least RMSD, RMSF, SASA and ROG values and strongest binding based on the MMPBSA analysis. This study proposes that oxacycloheptadecan-2-one be further developed as drug candidates for the management of hypertension. Our observation in this study substantiates the need for further experimental and clinical studies to buttress the in silico investigation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad I, Azminah A, Mulia K, Yanuar A, Mun'im A. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of polyphenolic compounds from Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth: an in silico molecular docking study. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2019;9(08):25–031. [Google Scholar]

- Alavijeh MS, Chishty M, Qaiser Z, Palmer AM. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics, the blood–brain barrier, and central nervous system drug discovery. J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2005;2:554–557. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerji A, Blumenthal KG, Lai KH, Zhou L. Epidemiology of ACE inhibitor angioedema utilizing a large electronic health record. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:744–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Van Gunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert T, Prakash C. ADME profiling in drug discovery and development: an overview. Encycl Drug Metab Interact. 2012 doi: 10.1002/9780470921920.edm021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Ben-Shalom IY, Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE, III, Cruzeiro VWD, Darden TA, Duke RE, Ghoreishi D, Gilson MK, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Greene D, Harris R, Homeyer N, Huang Y, Izadi S, Kovalenko A, Kurtzman T, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C, Liu J, Luchko T, Luo R, Mermelstein DJ, Merz KM, Miao Y, Monard G, Nguyen C, Nguyen H, Omelyan I, Onufriev A, Pan F, Qi R, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Schott-Verdugo S, Shen J, Simmerling CL, Smith J, Salomon-Ferrer R, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wei H, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xiao L, York DM, Kollman PA. Amber. San Francisco: University of California; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JD, Prabhu KS, Thompson JT, Reddy PS, Peters JM, Peterson B. The oxidative stress mediator 4-hydroxynonenal anintracellularagonistofthenuclearreceptorperoxisomeproliferator-activated receptor beta/delta(PPARbeta/delta) Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia MA, Hollenberg PF. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes. In: de Montellano PRO, editor. Cytochrome P450. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 177–259. [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Rzhetsky A, Allikmets R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001;11:115e666. doi: 10.1101/gr.184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Liu Y, Wang J, Wu S, Geng L, Sui Z. Antihypertensive effects of two novel angiotensin IConverting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from gracilariopsis lemaneiformis (Rhodophyta) in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) Mar Drugs. 2018;16(9):299–305. doi: 10.3390/md16090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di L, Artursson P, Benet LZ, Houston JB, Kansy M, Kerns EH, Lennernäs H, Smith DA, Sugano K. The critical role of passive permeability in designing successful drugs. Chem Med Chem. 2020;15:1862–1874. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves F, Rueff J, Kranendonk M. The central role of cytochrome P450 in xenobiotic metabolism. A brief review on a fascinating enzyme family. J Xenobiot. 2021;11:94–114. doi: 10.3390/jox11030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido A, Lepailleur A, Mignani SM, Dallemagne P, Rochais C. hERG toxicity assessment: useful guidelines for drug design. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;195:112290. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Ramamoorthy A. Probing protein–protein and protein–substrate interactions in the dynamic membrane-associated ternary complex of cytochromes P450, b5, and reductase. Chem Commun Camb Engl. 2019;55:13422–13425. doi: 10.1039/C9CC05904K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guengerich FP, Waterman MR, Egli M. Recent structural insights into cytochrome P450 function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:625–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanser T, Steinmetz FP. Avoiding hERG-liability in drug design via synergetic combinations of different (Q)SAR methodologies and data sources: a case study in an industrial setting. J Cheminform. 2019;11:9. doi: 10.1186/s13321-019-0334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 2001;104:569–580. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoutoul M, Djedouani A, Lamsayah M, Abrigach F, Touzani R. Liquid–liquid extraction of metalions, DFT and TD-DFT analysis for some pyrane derivatives with high selectivity for Fe(II) and Pb(II) Sep Sci Technol. 2016;51(7):1112–1123. doi: 10.1080/01496395.2015.1107583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kloting N, Bluher M. Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, Lee M, Lee T, Duan Y, Wang W, Donini O, Cieplak P, Srinivasan J, Case DA, Cheatham III TE. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawal M, Olotu FA, Soliman MES. Across the blood-brain barrier: neurotherapeutic screening and characterization of naringenin as a novel CRMP-2 inhibitor in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease using bioinformatics and computational tools. Comput Biol Med. 2018;98:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GR, Shin WH, Park HB, Shin S, Seok C. Conformational sampling of flexible ligand-binding protein loops. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2012;33(3):770–774. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2012.33.3.770. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung L, Kalgutkar AS, Obach RS. Metabolic activation in drug induced liver injury. Drug Metab Rev. 2012;44:18–33. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.605791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1–3):3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Fernandez M, Wouters MA, Heyberger S, Husain A. Arg-1098 is critical for the chloride dependence of human angiotensin-1 converting enzyme C-domain catalytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33518–33525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma FF, Wang H, Wei CK, Thakur K, Wei Z, Jiang L. Three novel ACE inhibitory peptides isolated from Ginkgo biloba seeds: purification, inhibitory kinetic and mechanism. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1579. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod-Carey D, Solis-Céspedes E, Lamazares E, Mena-Ulecia K. Evaluation of new antihypertensive drugs designed in silico using Thermolysin as a target. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan P, Nagini S. Cytochrome P450 structure, function and clinical significance: a review. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(1):38–54. doi: 10.2174/1389450118666170125144557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Bavishi C, Rimoldi SF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertension to use or not to use? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(13):1474–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearny PM, Reynolds K, Chen J, He J. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control. Circulation. 2016;134:441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllsten A, Stegmayr B, Wiklund PG. Genetic polymorphisms in the renin-angiotensin system confer increased risk of stroke independently of blood pressure: a nested case–control study. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282fe1d55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myatt GJ, Ahlberg E, Akahori Y, Allen D, Amberg A, Anger LT, Aptula A, Auerbach S, Beilke L, Bellion P, Benigni R, Bercu J, Booth ED, Bower D, Brigo A, Burden N, Cammerer Z, Cronin MTD, Cross KP, Custer L, Dettwiler M, Dobo K, Ford KA, Fortin MC, Gad-McDonald SE, Gellatly N, Gervais Vé, Glover KP, Glowienke S, Van Gompel J, Gutsell S, Hardy B, Harvey JS, Hillegass J, Honma M, Hsieh J-H, Hsu C-W, Hughes K, Johnson C, Jolly R, Jones D, Kemper R, Kenyon MO, Kim MT, Kruhlak NL, Kulkarni SA, Kümmerer K, Leavitt P, Majer B, Masten S, Miller S, Moser J, Mumtaz M, Muster W, Neilson L, Oprea TI, Patlewicz G, Paulino A, Lo Piparo E, Powley M, Quigley DP, Reddy MV, Richarz A-N, Ruiz P, Schilter B, Serafimova R, Simpson W, Stavitskaya L, Stidl R, Suarez-Rodriguez D, Szabo DT, Teasdale A, Trejo-Martin A, Valentin J-P, Vuorinen A, Wall BA, Watts P, White AT, Wichard J, Witt KL, Woolley A, Woolley D, Zwickl C, Hasselgren C. In silico toxicology protocols. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natesh R, Schwager SLU, Sturrock ED, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of the human angiotensin-converting enzyme–lisinopril complex. Nature. 2003;421:551–554. doi: 10.1038/nature01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris W, Paredes AH, Lewis JH. Drug-induced liver injury in 2007. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24(3):287–297. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f9764b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obode OC, Adebayo AH, Omonhinmin CA, Yakubu OF. A systematic review of medicinal plants used in Nigeria for hypertension management. Int J Pharm Res. 2020;12(4):2231–2275. [Google Scholar]

- O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olotu FA, Soliman MES. From mutational inactivation to aberrant gain-of-function: unraveling the structural basis of mutant p53 oncogenic transition. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:2646–2652. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Cao J, Guo H, Zhao B. Studies on purification and the molecular mechanism of a novel ACE inhibitory peptide from whey protein hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2012;130(1):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit A, Sachdeva T, Bafna P. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity: a review. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;02:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman S. Toxicological screening. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2(2):74–79. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.81895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest BT, Bell IM, Garcia ML. Role of hERG potassium channel assays in drug development. Landes Biosci. 2008;2(2):87–93. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.2.6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam K, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Cassis LA. The renin-angiotensin system: a target of and contributor to dyslipidemias, altered glucose homeostasis, and hypertension of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(6):H1219–H1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00796.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C, Zhang R, Liu F, Zheng T, Wu W. Molecular mechanism of interactions between inhibitory tripeptide GEF and angiotensin-converting enzyme in aqueous solutions by molecular dynamic simulations. J Mol Liq. 2018;249:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.11.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raji V, Loganathan C, Sadhasivam G, Kandasamy S, Poomani K, Thayumanavan P. Purification of fucoxanthin from Sargassum wightii Greville and understanding the inhibition of angiotensin 1-converting enzyme: an in vitro and in silico studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;148(2020):696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakib A, Nain Z, Sami SA, Mahmud S, Islam A, Ahmed S, Siddiqui ABF, Babu SMOF, Hossain P, Shahriar A, Nainu F, Emran TB, Simal-Gandara J. A molecular modelling approach for identifying antiviral selenium-containing heterocyclic compounds that inhibit the main protease of SARSCoV-2: an in silico investigation. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22:1476–1498. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AK, Gupta PSS, Panda SK, Biswal S, Bhattacharya U, Rana MK. Repurposing of FDA-approved drugs as potential inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease: molecular insights into improved therapeutic discovery. Comput Biol Med. 2022;142:105183. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.105183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sembuling K, Sembuling P. Essential of medical physiology. 6. Delhi: New Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Cho WC, Upadhyay G. Drug-induced liver toxicity and prevention by herbal antioxidants: an overview. Front Physiol. 2016;6(363):1–17. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie PD, Allison MA, Aviles-Santa ML, Cai J, Daviglus ML, Howard AG, Kaplan R, LaVange LM, Raij L, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil- SS, Talavera GA. Prevalence of hypertension, awareness, treatment, and control in the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:793–800. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks MA, Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Mirotsou M, Coffman TM. Classical renin–angiotensin system in kidney physiology. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(3):1201–1228. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M, Zhang Q, Bai X. Availability, cost, and prescription patterns of antihypertensive medications in primary health care in China: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2017;390:2559–2568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Wang C, Meng Q, Liu Z, Huo X, Sun P. Targeting P-glycoprotein and SORCIN: dihydromyricetin strengthens anti-proliferative efficiency of adriamycin via MAPK/ERK and Ca2þ-mediated apoptosis pathways in MCF-7/ADR and K562/ADR. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:3066e79. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum N, Ahmad F. Role of natural herbs in the treatment of hypertension. Pharmacogn Rev. 2011;5(9):30–40. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.79097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir RA, Bashir A, Yousaf MN, Ahmed A, Dali Y, Khan S. In silico identification of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from MRJP1. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda Y, Miyashita T, Endo S, Tsuneyama K, Fukami T, Nakajima M. Estradiol and progesterone modulate halothane-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Lett. 2011;204:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng DS, Kwong J, Rezvani F, Coates AO. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-related cough among Chinese-Americans. Am J Med. 2010;123:183.e11-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem. 2002;6(45):2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay U, Gupta S, Mathur P, Suravajhala P, Bhatnagar P. Microbial mutagenicity assay. Ames Test Bio Protocol. 2018;8(6):1–15. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva-Paz M, Morán L, López-Alcántara N, Freixo C, Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Cubero FJ. Oxidative stress in drug-induced liver injury (DILI): from mechanisms to biomarkers for use in clinical practice. Antioxidants. 2021;10(3):390. doi: 10.3390/antiox10030390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadood A, Ahmed N, Shah L, Ahmad A, Hassan H, Shams S. In-silico drug design. An approach which revolutionarised the drug discovery process. OA Drug Des Deliv. 2013;1(1):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Comprehensive assessment of ADMET risks in drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(19):2195–2219. doi: 10.2174/138161209788682514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Kang IS, Lee JY. Ensemble simulations of Asian-Australian monsoon variability by 11 AGCMs. J Clim. 2004;17:803–818. doi: 10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<0803:ESOAMV>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, McKinnie SM, Farhan M, Paul M, McDonald T, McLean B, Llorens-Cortes C, Hazra S, Murray AG, Vederas JC, Oudit GY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 metabolizes and partially inactivates pyr-apelin-13 and apelin-17: physiological effects in the cardiovascular system. Hypertension. 2016;68(2):365–377. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PB. Drug safety sciences and the bottleneck in drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:788–790. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. Angiotensin converting enzymes. Handb Horm. 2016 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801028-0.00254-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Lin G, Zhang R, Liang Z, Wu WW. Studies on molecular mechanism between ACE and inhibitory peptides in different bioactivities by 3D-QSAR and MD simulations. J Mol Liq. 2020;304:112702. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanger UM, Schwab M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138:103–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Du K, Ji PJ, Feng W. Molecular mechanism of the interactions between inhibitory tripeptides and angiotensin-converting enzyme. Biophys Chem. 2012;168–169:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Riley LM, Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, Singleton RK. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–980. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.