Abstract

Purpose:

The phase II CAPTIVATE study investigated first-line treatment with ibrutinib plus venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in two cohorts: minimal residual disease (MRD)-guided randomized treatment discontinuation (MRD cohort) and fixed duration (FD cohort). We report tumor debulking and tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk category reduction with three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in before initiation of venetoclax using pooled data from the MRD and FD cohorts.

Patients and Methods:

In both cohorts, patients initially received three cycles of ibrutinib 420 mg/day then 12 cycles of ibrutinib plus venetoclax (5-week ramp-up to 400 mg/day).

Results:

In the total population (N = 323), the following decreases from baseline to after ibrutinib lead-in were observed: percentage of patients with a lymph node diameter ≥5 cm decreased from 31% to 4%, with absolute lymphocyte count ≥25 × 109/L from 76% to 65%, with high tumor burden category for TLS risk from 23% to 2%, and with an indication for hospitalization (high TLS risk, or medium TLS risk and creatinine clearance <80 mL/minute) from 43% to 18%. Laboratory TLS per Howard criteria occurred in one patient; no clinical TLS was observed.

Conclusions:

Three cycles of ibrutinib lead-in before venetoclax initiation provides effective tumor debulking, decreases the TLS risk category and reduces the need for hospitalization for intensive monitoring for TLS.

Translational Relevance.

Effective tumor debulking with single-agent ibrutinib before venetoclax initiation may reduce the proportion of patients with a high hematological tumor burden requiring hospitalization for intensive monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS). We evaluated the impact of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in on tumor debulking and risk of TLS using pooled data from 323 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) treated with first-line ibrutinib plus venetoclax in the CAPTIVATE study. At baseline, 74 (23%) patients had a high tumor burden category for TLS risk. Three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in before initiation of venetoclax provided effective tumor debulking and reduced TLS risk category for 68 (92%) of these patients. Consequently, hospitalization during venetoclax initiation was no longer indicated in 61% of patients with such an indication at baseline. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax represents an all-oral, once-daily, chemotherapy-free regimen that can be delivered in the outpatient setting for most patients with CLL.

Introduction

Ibrutinib, a once-daily oral Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and venetoclax, a BCL-2 inhibitor, are both approved for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL; refs. 1, 2). Together, ibrutinib and venetoclax eliminate both dividing and resting CLL cells through different but complementary modes of action that preferentially affect distinct CLL subpopulations and cell compartments (3–5). In the CAPTIVATE and GLOW clinical studies, the combination of ibrutinib plus venetoclax demonstrated high rates of undetectable minimal residual disease (MRD) in both peripheral blood and bone marrow and high rates of progression-free survival in patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL (6–8), with durable treatment-free remissions in patients treated with fixed-duration ibrutinib plus venetoclax (7, 8).

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), a potentially life-threatening adverse event resulting from release of tumor cell contents into the circulation, can occur spontaneously in tumors with a high proliferative rate or in response to treatment in patients with high tumor burden (9). TLS is characterized by electrolyte and metabolic disturbances with laboratory findings of hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and/or hypocalcemia, which can lead to renal insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and multiorgan failure (9). TLS was identified as an adverse reaction early in the development of venetoclax. Prevention strategies are required to mitigate TLS risk, including standardized dose ramp-up and risk-adapted prophylaxis and monitoring as described in prescribing information for venetoclax (2). Per venetoclax prescribing information, a proportion of patients will require hospitalization for intensive monitoring during venetoclax initiation because of high TLS risk or medium TLS risk with creatinine clearance <80 mL/minute (2). Real-world data suggest that most patients have one or more planned hospitalizations during venetoclax ramp-up highlighting challenges for settings outside of clinical trials (10). Despite these prevention strategies, approximately 9–12% of patients with CLL and high baseline tumor burden develop laboratory and/or clinical TLS during venetoclax initiation (10, 11). Reduction of TLS risk category through effective tumor debulking before venetoclax initiation could allow more patients to initiate venetoclax in the outpatient setting and reduce healthcare burden for patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. Previous studies using single-agent ibrutinib demonstrated rapid tumor debulking in a large proportion of patients with CLL/SLL (12). Therefore, three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in before combination treatment with ibrutinib plus venetoclax is expected to reduce tumor burden category for TLS risk and the need for hospitalization during venetoclax initiation.

CAPTIVATE is a multicenter phase II study that demonstrated deep and durable responses with ibrutinib plus venetoclax in first-line treatment of CLL/SLL (6, 7). Here, we report results from the lead-in portion of the CAPTIVATE study to evaluate tumor debulking, TLS risk, and indication for hospitalization with three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in before venetoclax initiation.

Patients and Methods

Study design and treatment

CAPTIVATE is a multicenter, international, phase II study comprising two sequentially enrolled cohorts: the MRD cohort (6) and the fixed-duration (FD) cohort (7). In both cohorts, patients received single-agent oral ibrutinib (420 mg once daily) lead-in for three cycles followed by combined ibrutinib plus oral venetoclax (target dose 400 mg once daily after standard 5-week ramp-up, with TLS prophylaxis and monitoring per venetoclax prescribing information; ref. 2) for 12 cycles. Each cycle was 28 days. Subsequently, FD cohort patients received no further treatment (7), while MRD cohort patients were randomly assigned to subsequent treatment, including a placebo arm, according to MRD status (6).

The study was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards or independent ethics committees of all participating institutions. All patients provided written informed consent. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02910583).

Patients

Key eligibility criteria included adults aged ≥18 to <70 years (MRD cohort) or ≤70 years (FD cohort); previously untreated CLL/SLL requiring treatment per International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (iwCLL) criteria (13); measurable nodal disease by CT; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1; and adequate hepatic, renal, and hematologic function. Due to requirement for TLS prophylaxis per venetoclax prescribing information (2), patients with known allergy to xanthine oxidase inhibitors and/or rasburicase were excluded.

Tumor burden and TLS risk category assessments

Tumor burden was assessed by radiographic evaluation of the sum of the products of perpendicular diameters (SPD) of target lymph nodes and craniocaudal spleen length using CT or MRI, and by absolute lymphocyte count (ALC). Radiographic evaluation was performed at baseline and at the end of cycle 3 (before venetoclax initiation in cycle 4). ALC and serum creatinine were assessed at baseline, on day 1 of cycles 2 and 3, at the end of cycle 3 (before venetoclax initiation in cycle 4), and at 24 hours prior to each venetoclax ramp-up (weeks 2–4 of cycle 4 and week 1 of cycle 5). Additional hematology and serum chemistry samples were collected at 6–8 hours and at 24 hours after the first dose of each venetoclax ramp-up for patients in the high-risk category for TLS, as recommended per venetoclax prescribing information (2). Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula. Tumor burden categories for TLS risk (Supplementary Table S1) were assessed at baseline and before venetoclax initiation in cycle 4 using criteria described in venetoclax prescribing information (2).

TLS monitoring assessments

TLS monitoring with serum chemistry, which included potassium, uric acid, phosphorus, and calcium, was performed on the same schedule as that described for ALC and serum creatinine. Indication for hospitalization for TLS prophylaxis and monitoring was assessed at the same timepoints as TLS risk category assessments (Supplementary Table S2). Patients in the high-risk category for TLS (≥1 lymph node lesion ≥10 cm in longest diameter, or ≥1 lesion ≥5 cm to <10 cm plus circulating lymphocytes >25×109/L) were hospitalized during the first 24–48 hours of venetoclax treatment for more rigorous TLS monitoring and prophylaxis as recommended per venetoclax prescribing information (2). Hospitalization was also recommended for patients with medium TLS risk and creatinine clearance <80 mL/minute (2) and could be considered as clinically indicated for patients lacking immediate access to a facility capable of promptly correcting TLS or who were otherwise considered at risk for TLS per treating physician discretion. TLS was assessed using Howard criteria (9).

Data availability statement

Requests for access to individual participant data from clinical studies conducted by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Results

Three hundred twenty-three patients were enrolled in CAPTIVATE: 164 in the MRD cohort and 159 in the FD cohort. Baseline characteristics were similar between cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline.

| MRD cohort | FD cohort | Overall population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N = 164 | N = 159 | N = 323 |

| Age | |||

| Median, years (range) | 58 (28–69) | 60 (33–71) | 59 (28–71) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 41 (25) | 45 (28) | 86 (27) |

| Male, n (%) | 103 (63) | 106 (67) | 209 (65) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 105 (64) | 110 (69) | 215 (67) |

| 1 | 59 (36) | 49 (31) | 108 (33) |

| Histology, n (%) | |||

| CLL | 156 (95) | 146 (92) | 302 (93) |

| SLL | 8 (5) | 13 (8) | 21 (7) |

| Rai stage, n (%) | |||

| 0/I/II | 111 (68) | 113 (71) | 224 (69) |

| III/IV | 53 (32) | 44 (28) | 97 (30) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Bulky disease, n (%) | |||

| ≥5 cm | 53 (32) | 48 (30) | 101 (31) |

| ≥10 cm | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | 10 (3) |

| ALC ≥25 × 109/L, n (%) | 125 (76) | 120 (75) | 245 (76) |

| ALC, × 109/L | |||

| Mean (SD) | 86 (81) | 92 (89) | 89 (85) |

| Median (range) | 56 (1–419) | 70 (1–503) | 65 (1–503) |

| Tumor burden category for TLS risk, n (%) | |||

| High | 40 (24) | 34 (21) | 74 (23) |

| Medium | 102 (62) | 97 (61) | 199 (62) |

| Low | 22 (13) | 28 (18) | 50 (15) |

| Cytopenia at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Any cytopenia | 59 (36) | 54 (34) | 113 (35) |

| Hemoglobin ≤11 g/dL | 35 (21) | 37 (23) | 72 (22) |

| Platelet count ≤100 × 109/L | 30 (18) | 21 (13) | 51 (16) |

| ANC ≤1.5 × 109/L | 14 (9) | 13 (8) | 27 (8) |

| Hierarchical cytogenetics classification, n (%)a | |||

| Del(17p) | 26 (16) | 20 (13) | 46 (14) |

| Del(11q) | 28 (17) | 28 (18) | 56 (17) |

| Trisomy 12 | 22 (13) | 23 (14) | 45 (14) |

| Normal | 25 (15) | 33 (21) | 58 (18) |

| Del(13q) | 63 (38) | 54 (34) | 117 (36) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Mutated TP53, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (12) | 16 (10) | 36 (11) |

| No | 144 (88) | 142 (89) | 286 (89) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Del(17p) or mutated TP53, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 32 (20) | 27 (17) | 59 (18) |

| No | 131 (80) | 129 (81) | 260 (80) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) |

| IGHV gene mutation status, n (%) | |||

| Unmutated | 99 (60) | 89 (56) | 188 (58) |

| Mutated | 63 (38) | 66 (42) | 129 (40) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | 6 (2) |

| Complex karyotype, n (%)b | |||

| Yes | 31 (19) | 31 (19) | 62 (19) |

| No | 106 (65) | 102 (64) | 208 (64) |

| Unknown | 27 (16) | 26 (16) | 53 (16) |

Abbreviations: ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FD, fixed duration; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; MRD, minimal residual disease; SD, standard deviation; TLS, tumor lysis syndrome.

aPer Dohner hierarchy.

bDefined as ≥3 abnormalities by conventional CpG-stimulated cytogenetics.

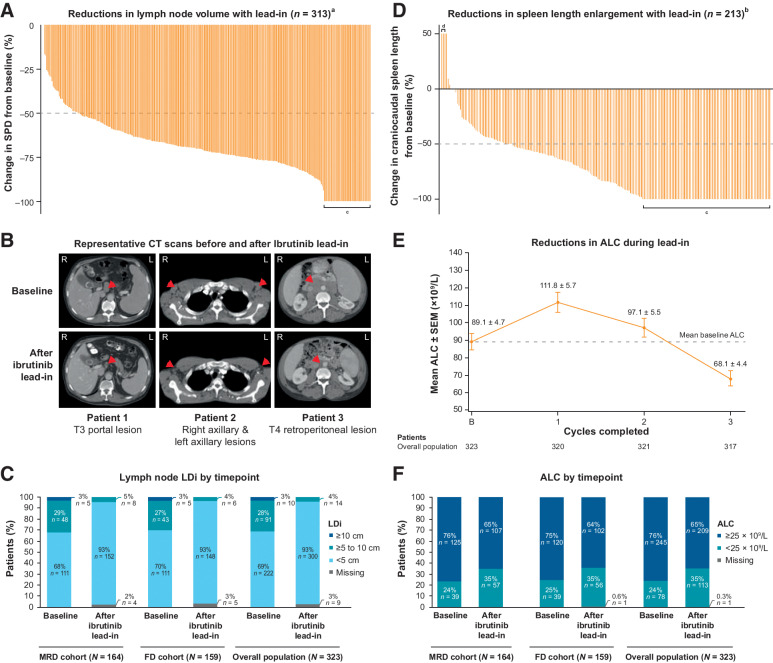

Tumor burden reduction

In the overall population, lymph node burden was reduced in all patients after three cycles of ibrutinib lead-in (Fig. 1A). Among 313 patients with measurable target lesions at baseline [lymph node longest diameters (LDi) >1.5 cm], 280 (89%) had reductions of ≥50% in SPD of target lymph nodes; 44 (14%) had resolution of maximum LDi to ≤1.5 cm (Fig. 1A). Representative images are shown in Fig. 1B. The proportion of patients with LDi ≥5 cm decreased from 31% (101/323) at baseline to 4% (14/323) after ibrutinib lead-in (Fig. 1C). The proportion of patients with LDi ≥10 cm was 3% (10/323) at baseline and 0% after ibrutinib lead-in. Of 213 patients with spleen length enlargement at baseline, 172 (81%) had reductions of ≥50% in spleen length after ibrutinib lead-in; 83 (39%) had resolution of craniocaudal spleen length to ≤13 cm (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Single-agent ibrutinib lead-in impact on tumor debulking. A, Waterfall plot of percent change in the sum of the products of perpendicular diameters of target lymph nodes (SPD) in individual patients after ibrutinib lead-in,a (B) representative CT scans of target lymph nodes at baseline and after ibrutinib lead-in, (C) lymph node maximal LDi of target lymph nodes at baseline and after ibrutinib lead-in, (D) waterfall plot of percent change in spleen length enlargement in individual patients after ibrutinib lead-in,b (E) mean ALC by cycle during ibrutinib lead-in, and (F) ALC by timepoint at baseline and after ibrutinib lead-in. aIn patients with measurable target lesions (LDi >1.5 cm) at baseline and measured after ibrutinib lead-in (n = 313). bIn patients with spleen length enlarged >13 cm at baseline and measured after ibrutinib lead-in (n = 213). cLDi resolved to ≤1.5 cm or spleen length resolved to ≤13 cm. dSpleen length enlargement was increased by 400% (from 0.3 to 1.5 cm) in one patient, by 275% (from 0.4 to 1.5 cm) in one patient, and by 85% (from 2.5 to 3.9 cm) in one patient. ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; FD, fixed duration; LDi, maximal lymph node diameter of target lesions; MRD, minimal residual disease; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Mean ALC remained above baseline levels after two cycles of ibrutinib lead-in (day 1 of cycle 3) due to its established pharmacodynamic effects of lymphocytosis but was reduced to below baseline levels after three cycles (Fig. 1E). The proportion of patients with ALC ≥25 × 109/L decreased from 76% (245/323) at baseline to 65% (209/323) after three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in (Fig. 1F).

TLS risk category/indication for hospitalization

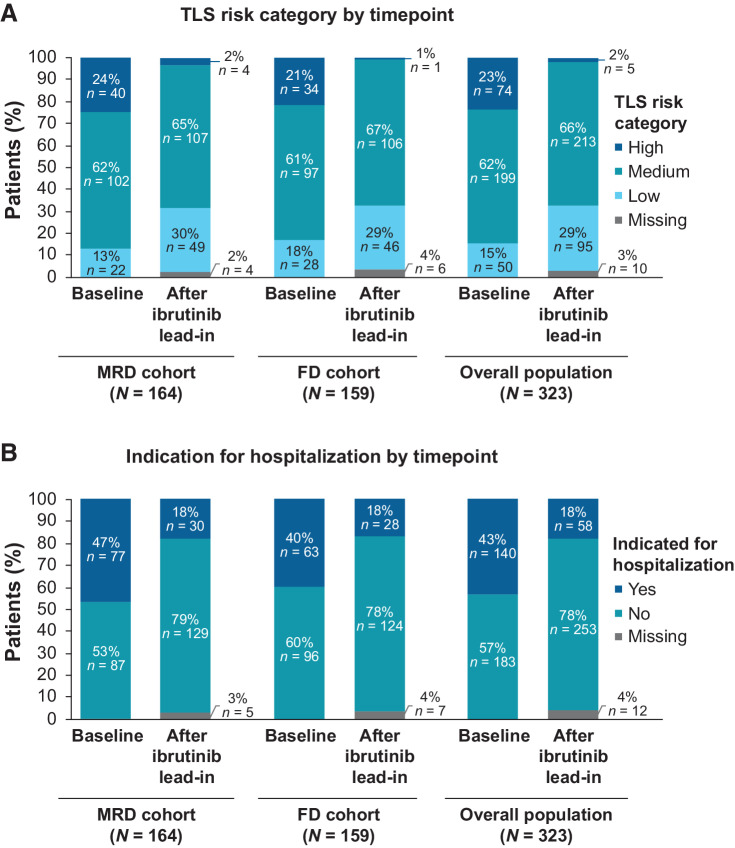

At baseline risk assessment for TLS before ibrutinib initiation, 23% (74/323) of patients were categorized as high tumor burden category for TLS risk. Most (66/323; 20%) of these patients were categorized as high tumor burden category for TLS risk based on LDi ≥5 cm to 10 cm with ALC ≥25 × 109/L, whereas 2% (8/323) had LDi ≥10 cm. After ibrutinib lead-in, 2% (5/323) of patients were in the high tumor burden category for TLS risk, all of whom had LDi ≥5 cm to 10 cm with ALC ≥25 × 109/L (Fig. 2A). Overall, 92% (68/74) of patients with high tumor burden category for TLS risk at baseline shifted to medium [53/74 (72%)] or low [15/74 (20%)] tumor burden categories for TLS risk and 7% (5/74) remained in the high tumor burden category for TLS risk; one patient had missing assessment after ibrutinib lead-in.

Figure 2.

Single-agent ibrutinib lead-in impact on (A) tumor burden category for TLS risk and (B) indication for hospitalization. FD, fixed duration; MRD, minimal residual disease; TLS, tumor lysis syndrome.

The proportion of patients indicated for hospitalization for TLS monitoring and prophylaxis per venetoclax prescribing information decreased from 43% (140/323) at baseline to 18% (58/323) after ibrutinib lead-in (Fig. 2B).

Of 140 patients in the total population who met criteria for indication for hospitalization at baseline, 61% (85/140) were no longer indicated for hospitalization after lead-in. Of 58 patients who met criteria for indication for hospitalization after ibrutinib lead-in, 5 had high tumor burden category for TLS risk and 53 had medium tumor burden category for TLS risk with creatinine clearance <80 mL/minute. Of the 323 patients, 312 completed three cycles of ibrutinib lead-in and started ibrutinib plus venetoclax. Overall, following protocol and local standards of care, 55/312 patients (18%) were hospitalized for TLS monitoring and prophylaxis during venetoclax initiation. Results were consistent between the MRD and FD cohorts.

Laboratory and clinical TLS

In 312 patients who started treatment with ibrutinib plus venetoclax, abnormalities in TLS-associated individual laboratory parameters were modest in frequency during monitoring (Table 2). Laboratory TLS per Howard criteria occurred in one patient who was in the low tumor burden category for TLS risk at baseline and did not receive protocol-specified oral hydration and allopurinol; abnormalities resolved spontaneously without dose modification, hospitalization, or clinical sequelae. No patients had laboratory TLS with increased creatinine and no clinical TLS was observed.

Table 2.

Laboratory parameters monitored for TLS per Howard criteria in patients who completed ibrutinib lead-in and started ibrutinib plus venetoclax.

| MRD cohort | FD cohort | Pooled cohorts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 159 | N = 153 | N = 312 | ||||

| Met Howard criteria, n (%) | Before venetoclaxa | After venetoclaxb | Before venetoclaxa | After venetoclaxb | Before venetoclaxa | After venetoclaxb |

| Uric acid >475.8 μmol/L | 3 (2) | 9 (6) | 0 | 7 (5) | 3 (1) | 16 (5) |

| Phosphorous >1.5 mmol/L | 6 (4) | 40 (25) | 6 (4) | 37 (24) | 12 (4) | 77 (25) |

| Potassium >6.0 mmol/L | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2) | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1) |

| Corrected calcium <1.75 mmol/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Creatinine increased by ≥26.5 μmol/Ld | NA | 6 (4) | NA | 5 (3) | NA | 11 (3) |

| Laboratory TLSc | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Laboratory TLS with increased creatinined,e | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 |

Abbreviations: FD, fixed duration; MRD, minimal residual disease; NA, not applicable; TLS, tumor lysis syndrome.

aLast measurement before initiation of venetoclax.

bWithin 8 weeks after the first dose of venetoclax.

cPresence of ≥2 metabolic abnormalities within the same 24-hour period.

dCreatinine increased by ≥26.5 μmol/L since last measurement before initiation of venetoclax.

eCreatinine increased by ≥26.5 μmol/L within 24 hours of laboratory TLS.

Discussion

Three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib lead-in before venetoclax initiation provided effective tumor debulking with substantial reductions in lymph node burden and ALC in this analysis of 323 young, fit patients treated with first-line ibrutinib plus venetoclax in the CAPTIVATE study, including in patients with high-risk disease features. Indeed, 89% of patients met radiographic criteria for partial response or better after three cycles of ibrutinib, with ≥50% reductions in target lymph nodes. Consistent with known effects of single-agent ibrutinib (12), together with reductions in lymph node burden, an initial increase in ALC was observed after the first cycle of ibrutinib lead-in followed by a gradual reduction in ALC in subsequent cycles. There was greater reduction in ALC during cycle 3, suggesting greater potential benefit with three versus two cycles of lead-in. These findings are consistent with results of previous studies demonstrating that single-agent ibrutinib treatment for 2–4 months rapidly reduces tumor bulk in a large proportion of patients with CLL/SLL (12, 14), effectively mitigating the risk of venetoclax-related TLS.

With this tumor debulking, three cycles of ibrutinib lead-in before venetoclax initiation in the CAPTIVATE study reduced tumor burden category for TLS risk for 92% of patients with high tumor burden at baseline as defined by very large lymph nodes (LDi ≥10 cm), or a combination of large lymph nodes (LDi ≥5 cm to 10 cm) with elevated lymphocyte count (≥25 × 109/L) per venetoclax prescribing information (2). Similar results were observed in the phase III GLOW study, which evaluated first-line treatment with three cycles of ibrutinib followed by 12 cycles of combined ibrutinib plus venetoclax in a complementary population of older/unfit patients; after ibrutinib lead-in, tumor burden category was reduced in 85% of patients with high tumor burden category at baseline (8). Building on the results of previous studies, we demonstrated that tumor debulking with single-agent ibrutinib lead-in also reduced the need for hospitalization for intensive monitoring for TLS in the young, fit population of the CAPTIVATE study. After three cycles of ibrutinib lead-in, hospitalization during venetoclax initiation was no longer indicated in 61% of patients with such indication at baseline and 82% of patients were able to initiate venetoclax without hospitalization. The impact of ibrutinib lead-in on hospitalization has yet to be reported for the older/unfit population in the GLOW study who may be more likely to have renal impairment necessitating hospitalization per venetoclax prescribing information.

The phase III CLL14 study of first-line treatment with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab used one cycle of obinutuzumab before venetoclax initiation; although no clinical or laboratory TLS occurred during venetoclax initiation, laboratory TLS occurred in 3 of 212 patients (1.4%) during obinutuzumab lead-in before venetoclax initiation (15). TLS has been reported with obinutuzumab initiation, and US prescribing information for obinutuzumab recommends TLS prophylaxis for patients with high tumor burden, ALC >25 × 109/L, or renal impairment (16). In a recent phase II study, patients received one cycle of acalabrutinib followed by two cycles of acalabrutinib plus obinutuzumab before venetoclax initiation; no clinical or laboratory TLS was observed during venetoclax initiation, but laboratory TLS occurred in 2 of 37 patients (5%) during the acalabrutinib and obinutuzumab combination portion of the lead-in (17). Similarly, no cases of TLS were reported during venetoclax initiation in 29 patients who started combination treatment with zanubrutinib plus venetoclax after 3 months of zanubrutinib lead-in in the SEQUOIA Cohort 3 arm (18). Furthermore, infusion-related reactions occurred in 45% of patients treated with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab in the CLL14 study (15) and in 22% of patients treated with acalabrutinib plus obinutuzumab plus venetoclax in the phase II study (17). In comparison, laboratory TLS during the CAPTIVATE study was observed in just one patient (0.3%) treated with ibrutinib plus venetoclax, during venetoclax initiation. The occurrence in a patient with low tumor burden category for TLS risk highlights the importance of TLS prophylaxis and monitoring in all patients initiating venetoclax. The safety profile of ibrutinib lead-in was consistent with that previously reported with single-agent ibrutinib (6). Cross-trial comparisons should be interpreted with caution given differences in patient populations, and the broader safety profile of each regimen should also be taken into consideration, but ibrutinib may represent an attractive option for tumor debulking before venetoclax initiation without the risk of anti-CD20–related TLS or infusion-related reactions given the significant clinical and economic burden associated with treatment-emergent TLS (19). Oral debulking with ibrutinib may also represent an attractive alternative to intravenous anti-CD20 agents in the context of the COVID pandemic, minimizing time in the clinic with lower potential for compromising immune response to COVID vaccination (20).

In conclusion, tumor debulking with three cycles of single-agent ibrutinib reduces tumor burden category for TLS risk prior to venetoclax initiation, resulting in avoidance of hospitalization during venetoclax initiation in a large proportion of patients with high baseline risk of TLS. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax represents an all-oral, once-daily, chemotherapy-free, time-limited regimen that offers patient convenience and ease of administration and can be delivered in the outpatient setting for most patients with CLL/SLL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in the study and their supportive families, as well as the investigators and clinical research staff from the study centers. This study was sponsored by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company. Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Melanie Sweetlove, MSc, and funded by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Authors' Disclosures

P.M. Barr reports other support from Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, Gilead, Merck, Genentech, Celgene/BMS, TG Therapeutics, Janssen, BeiGene, Seattle Genetics, and MorphoSys outside the submitted work. A. Tedeschi reports personal fees from Janssen SpA, AbbVie, BeiGene, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. J.N. Allan reports personal fees from Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie Company, Janssen, Epizyme, AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene; grants from Celgene; and grants and personal fees from Genentech and TG Therapeutics outside the submitted work. P. Ghia reports grants and personal fees from AbbVie, Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, and Janssen during the conduct of the study; P. Ghia also reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, as well as personal fees from BeiGene, BMS, Loxo/Lilly, MSD, and Roche outside the submitted work. R. Jacobs reports grants and personal fees from Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, TG Therapeutics; grants from Loxo Oncology / Lilly; and personal fees from Secura Bio, Genentech, Adaptive, BeiGene, Janssen, AbbVie, and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. S. O'Brien reports other support from AbbVie, Acerta, Alexion, Alliance, Amgen, Aptose Biosciences, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Autolus, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, DynaMed, Eli Lily and Co, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Oncology, Johnsons & Johnson, Juno Therapeutics, Kite, Loxo Oncology, MEI Pharma, Merck, Mustang, NOVA Research Company, Nurix Therapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, Regeneron, TG Therapeutics, Vaniam Group, Verastem, and Vida Ventures during the conduct of the study. A.P. Grigg reports personal fees from Janssen outside the submitted work. J. Ninomoto reports other support from AbbVie outside the submitted work. G. Krigsfeld reports other support from AbbVie and Bristol Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. C.S. Tam reports other support from Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, AbbVie, and BeiGene during the conduct of the study. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions

P.M. Barr: Conceptualization, resources, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. A. Tedeschi: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. W.G. Wierda: Conceptualization, resources, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. J.N. Allan: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. P. Ghia: Conceptualization, resources, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing. D. Vallisa: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. R. Jacobs: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. S. O'Brien: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. A.P. Grigg: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. P. Walker: Resources, investigation, writing–review and editing. C. Zhou: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing–review and editing. J. Ninomoto: Conceptualization, supervision, visualization, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. G. Krigsfeld: Conceptualization, methodology, writing–review and editing. C.S. Tam: Conceptualization, resources, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing.

References

- 1. Imbruvica (ibrutinib) [package insert]. Sunnyvale, CA: Pharmacyclics LLC; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Venclexta (venetoclax tablets) for oral use [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deng J, Isik E, Fernandes SM, Brown JR, Letai A, Davids MS. Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibition increases BCL-2 dependence and enhances sensitivity to venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2017;31:2075–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herman SE, Gordon AL, Hertlein E, Ramanunni A, Zhang X, Jaglowski S, et al. Bruton tyrosine kinase represents a promising therapeutic target for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is effectively targeted by PCI-32765. Blood 2011;117:6287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu P, Wang S, Franzen CA, Venkataraman G, McClure R, Li L, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax target distinct subpopulations of CLL cells: implication for residual disease eradication. Blood Cancer J 2021;11:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wierda WG, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Kipps TJ, Opat S, Tedeschi A, et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax for first-line treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: primary analysis results from the minimal residual disease cohort of the randomized phase II CAPTIVATE study. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3853–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ghia P, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, Kipps TJ, Jacobs R, Opat S, et al. Fixed-duration (FD) first-line treatment (tx) with ibrutinib (I) plus venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL): Primary analysis of the FD cohort of the phase 2 captivate study. Poster presented at: ASCO21 Virtual; June 4–8, 2021.

- 8. Kater A, Owen C, Moreno C, Follows G, Munir T, Levin MD, et al. Fixed-duration ibrutinib and venetoclax (i+v) versus chlorambucil plus obinutuzumab (clb+o) for first-line (1L) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (cll): Primary analysis of the phase 3 glow study. Poster presented at: EHA2021 Virtual Congress; June 9–17, 2021.

- 9. Howard SC, Jones DP, Pui CH. The tumor lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1844–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roeker LE, Fox CP, Eyre TA, Brander DM, Allan JN, Schuster SJ, et al. Tumor lysis, adverse events, and dose adjustments in 297 venetoclax-treated CLL patients in routine clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:4264–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davids MS, Hallek M, Wierda W, Roberts AW, Stilgenbauer S, Jones JA, et al. Comprehensive safety analysis of venetoclax monotherapy for patients with relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wierda WG, Byrd JC, O'Brien S, Coutre S, Barr PM, Furman RR, et al. Tumour debulking and reduction in predicted risk of tumour lysis syndrome with single-agent ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2019;186:184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Dohner H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008;111:5446–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, Ferrajoli A, Burger J, Borthakur G, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2095–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Bahlo J, Fink AM, Tandon M, Dixon M, et al. Venetoclax and obinutuzumab in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2225–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gazyva (obinutuzumab) injection, for intravenous use [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davids MS, Lampson BL, Tyekucheva S, Wang Z, Lowney JC, Pazienza S, et al. Acalabrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab as frontline treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tedeschi A, Ferrant E, Flinn IW, Tam CS, Ghia P, Robak T, et al. Zanubrutinib in combination with venetoclax for patients with treatment-naïve (TN) chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) with del(17p): Early results from arm D of the SEQUOIA (BGB-3111–304) trial. Blood 2021;138:67. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rogers K, Emond B, Côté-Sergent A, Kinkead F, Lafeuille M-H, Lefebvre P, et al. Clinical and economic burden of tumor lysis syndrome among patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. Blood 2021;138:4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Molica S, Giannarelli D, Montserrat E. mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Haematol 2022;108:264–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Requests for access to individual participant data from clinical studies conducted by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie Company, can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.