Abstract

Transgender (trans) persons are sexually assaulted at high rates and often encounter barriers to equitable services and supports. The receipt of timely and appropriate postassault care, provided increasingly by specialized forensic nurses around the world, is critical in ameliorating the harms that accompany sexual assault. In order to adequately respond to the acute health care needs of trans clients and attend to longer term psychosocial difficulties that some experience, forensic nurses not only require specialized training but must also cultivate collaborative relationships with trans-positive health and social services in their communities. To meet this need, we describe our strategy to advance trans-affirming practice in the sexual assault context. We outline the design and evaluation of a trans-affirming care curriculum for forensic nurses. We also discuss the planning, formation, and maturation of an intersectoral network through which to disseminate our curriculum, foster collaboration, and promote trans-affirming practice across health care and social services in Ontario, Canada. Our approach to advancing trans-affirming practice holds the potential to address systemic barriers experienced by trans survivors and transform the response to sexual assault across other sectors and jurisdictions.

Keywords: access to health care, health disparities, LGBT health, partnerships/coalitions, training, violence prevention

Assessment of Need

It is a critical moment for transgender (trans) rights worldwide, with many in public health calling for the advancement of health equity for trans communities through improved programming and policy (Restar et al., 2020). These calls arise from the fact that trans persons—those whose gender identity may not fully or in part correspond with their sex assigned at birth, including gender diverse, genderqueer, genderfluid, Two Spirit, and nonbinary individuals—often face hurdles in accessing health care, including a lack of provider knowledge, refusal of services, and harassment and violence in medical settings (Du Mont, Kosa, et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2011). Barriers to care are particularly salient in the sexual assault context in which trans persons are victimized at lifetime rates as high as 47% (James et al., 2016). The receipt of timely and appropriate postassault supports is critical in mitigating the harms that accompany such experiences and may also aid in preventing future victimization.

Worldwide, forensic nurse examiners are increasingly assuming a central role in the provision of acute postsexual assault care (https://www.forensicnurses.org/). These nurses encounter trans persons in their practice and may thus require specialized education to sensitively respond to the complex health care needs with which trans survivors often present to emergency departments or violence treatment centers (Du Mont, Kosa, et al., 2020). Additionally, due to experiences of other forms of interpersonal and structural violence (e.g., transphobic hate crimes), trans survivors may have psychosocial difficulties that forensic nurses alone cannot address (Du Mont, Kosa, et al., 2020).

Trans-affirming practice, which “recognize[s], account[s] for, and address[es] the unique experiences and needs of trans survivors” (Saad et al., 2020, p. 65), provides a guiding framework to enhance the knowledge of forensic nurses, promote intersectoral collaboration in the care and support of trans persons, and redress the transphobic discrimination often experienced across health care and social service systems (Grant et al., 2011; James et al., 2016). This practice note describes our strategy for the advancement of trans-affirming practice in the sexual assault context.

Description of Strategy

Trans voices are vital in advancing trans-affirming practice. Our approach has therefore been guided by the invaluable input of trans community members variably as peer advisors, advisory group members, core members of the research team, and representatives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer (or questioning), intersex, and Two Spirit (LGBTQI2S) and sexual assault support organizations.

Development and Evaluation of a Trans-Affirming Care Curriculum for Forensic Nurses

We developed and evaluated a novel trans-affirming care curriculum for forensic nurses working across 36 hospital-based sexual assault/domestic violence treatment centers (SA/DVTCs) in Ontario (Du Mont, Saad, et al., 2020). This curriculum—freely available, competency-based, and evidence-informed—consists of a Training Module (slide deck covering all content), Facilitator’s Guide (slide-by-slide script with prompts for discussion), and Training Manual (independent resource that explores content in greater depth). Content includes an Introduction to the Issues (Key Terms, Experiences of Sexual Assault, Interactions with Healthcare) and Core Elements of the postsexual assault clinical encounter (Initial Assessment, Medical Care, Forensic Examination, Discharge and Referral) (https://translinknetwork.com/curricula). A recent pre- to posttraining evaluation conducted with 47 SA/DVTC nurses documented improvements in perceived level of expertise and competence across all content domains: initial assessment (p < .001), medical care (p < .001), forensic examination (p < .001), and discharge and referral (p < .001; Du Mont, Saad, et al., 2020). Nurses also demonstrated improvements in competence from pre- to posttraining by answering several questions associated with a clinical vignette focused on caring for a trans client (p < .001; Du Mont, Saad, et al., 2020).

Establishment of an Intersectoral Network on Trans-Affirming Practice

We established a provincial intersectoral network, called the trans-LINK Network, to foster trans-affirming practice across Ontario’s SA/DVTCs and the community-based organizations with whom they might refer or consult on the care of trans survivors. The development of the Network was guided by the lifecycle model, an approach endorsed by the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools that describes sequential stages for the planning, formation, and maturation of a network (Robeson, 2009).

In the planning stage, we brought together 106 representatives from 96 violence treatment centers and community organizations identifying as trans-positive (Saad et al., 2020). At these seven regional meetings, we determined the Network’s core membership, shared our nursing curriculum, and discussed key areas for Network leadership. Among the areas prioritized by attendees were education and training, peer involvement, advocacy, accessibility, and knowledge sharing and exchange (Saad et al., 2020).

In the formation stage, we further negotiated Network identity (e.g., values, activities) by surveying our members. We learned more about the rich diversity of services and supports they provide, including LGBTQI2S-specific, sexual assault, counselling/mental health, health care, housing/shelter, youth, employment, immigration and settlement, education, advocacy, legal, and peer support (Du Mont, Kosa, et al., 2020). We also determined priority Network deliverables, two of which were the development of an online resource directory of trans-positive services and supports and the creation of a knowledge sharing portal to host information on trans-affirming practice (Du Mont, Kosa, et al., 2020).

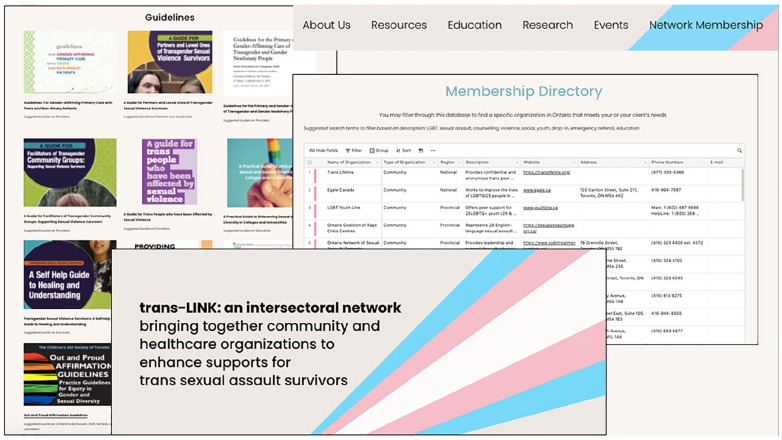

To address these priorities in the maturation stage, we focused on the development of an interactive directory and knowledge exchange platform. The interactive directory currently lists approximately 130 Network member organizations providing care and supports in Ontario and can be used by both service providers and trans survivors to locate trans-positive services in their community. It also forms a core component of our trans-LINK WebPortal (https://www.translinknetwork.com/), which we established through a survey of Network members on the perceived importance of various online resources to enhance trans-affirming practice. Based on the findings, the trans-LINK WebPortal hosts an array of relevant materials, including guidelines, toolkits, videos/podcasts, clinical summaries, information sheets, research reports, and curricula (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the trans-LINK WebPortal

Implications for Practice

By extending access to appropriate resources, including our curriculum on trans-affirming care, and building referral capacity among trans-positive services and supports in Ontario, the trans-LINK WebPortal is an ideal platform for the advancement of trans-affirming practice. Now widely available, our curriculum could be implemented in approximately 1,000 sexual assault nurse examiner programs worldwide (https://www.forensicnurses.org/) and modified to enhance applicability in the broader health and social service sectors. By fostering collaboration and creating opportunities for collective advocacy, our growing intersectoral Network is uniquely positioned to address the systemic discrimination and barriers to care experienced by trans sexual assault survivors. Our approach to advancing a trans-affirming response to sexual assault represents a promising step toward health equity for trans communities worldwide.

Next Steps

Our next step is to begin evaluating our Network using a social network analysis tool such as PARTNER (https://visiblenetworklabs.com/partner-platform/).

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: We wish to acknowledge the members of our various community advisory boards, who have contributed to this work in diverse capacities since its inception. These individuals include Alex Abramovich (Institute for Mental Health Policy Research), Lee Cameron (Egale Canada), Angel Gladdy (the 519), Paris Honoria (Egale Canada), Hannah Kia (Faculty of Social Work, University of British Columbia), Tara Leach (H.E.A.L.T.H), Devon MacFarlane (Rainbow Health Ontario), Kinnon MacKinnon (Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto), Yasmeen Persad (The 519), and Jack Woodman (Women’s College Hospital). We also wish to acknowledge the many representatives of trans-LINK Network member organizations whose passion and expertise continue to propel our project forward. The research on which this article is based received funding from the following sources: Women’s Xchange (Grant Number 15K2017R1) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Grant Numbers 611-2018-0488 and 890-2019-0047). The research on which this article is based received ethical approval from the Women’s College Hospital Research Ethics Board.

ORCID iD: Joseph Friedman Burley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9567-0327

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9567-0327

References

- Du Mont J., Kosa S. D., Hemalal S., Cameron L., Macdonald S. (2020). Formation of an intersectoral network to support trans survivors of sexual assault: A survey of health and community organizations. International Journal of Transgender Health. Advance online publication. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1787911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Du Mont J., Saad M., Kosa S. D., Kia H., Macdonald S. (2020). Providing trans-affirming care for sexual assault survivors: An evaluation of a novel curriculum for forensic nurses. Nurse Education Today, 93(October), 104541. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. M., Mottet L., Tanis J. E., Harrison J., Herman J., Keisling M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- James S. E., Herman J. L., Rankin S., Keisling M., Mottet L., Anafi M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S: Transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Restar A. J., Sherwood J., Edeza A., Collins C., Operario D. (2020). Expanding gender-based health equity framework for transgender populations. Transgender Health, 6(1), 1–4. 10.1089/trgh.2020.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson P. (2009). Networking in public health: Exploring the value of networks to the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. [Google Scholar]

- Saad M., Friedman Burley J., Miljanovski M., Macdonald S., Bradley C., Du Mont J. (2020). Planning an intersectoral network of healthcare and community leaders to advance trans-affirming care for sexual assault survivors. Healthcare Management Forum, 33(2), 65–69. 10.1177/0840470419883661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]