Abstract

E. coli O157:H7 is a food-borne adulterant that can cause hemorrhagic ulcerative colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Faced with an increasing risk of foods contaminated with E. coli O157:H7, food safety officials are seeking improved methods to detect and isolate E. coli O157:H7 in hazard analysis and critical control point systems in meat- and poultry-processing plants. A colony lift immunoassay was developed to facilitate the positive identification and quantification of E. coli O157:H7 by incorporating a simple colony lift enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with filter monitors and traditional culture methods. Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were prewet with methanol and were used to make replicates of every bacterial colony on agar plates or filter monitor membranes that were then reincubated for 15 to 18 h at 36 ± 1°C, during which the colonies not only remained viable but were reestablished. The membranes were dried, blocked with blocking buffer (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories [KPL], Gaithersburg, Md.), and exposed for 7 min to an affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157 antibody (KPL). The membranes were washed, exposed to a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine membrane substrate (TMB; KPL) or aminoethyl carbazole (AEC; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), rinsed in deionized water, and air dried. Colonies of E. coli O157:H7 were identified by either a blue (via TMB) or a red (via AEC) color reaction. The colored spots on the PVDF lift membrane were then matched to their respective parent colonies on the agar plates or filter monitor membranes. The colony lift immunoassay was tested with a wide range of genera in the family Enterobacteriaceae as well as different serotypes within the E. coli genus. The colony lift immunoassay provided a simple, rapid, and accurate method for confirming the presence of E. coli O157:H7 colonies isolated on filter monitors or spread plates by traditional culture methods. An advantage of using the colony lift immunoassay is the ability to test every colony serologically on an agar plate or filter monitor membrane simultaneously for the presence of the E. coli O157 antigen. This colony lift immunoassay has recently been successfully incorporated into a rapid-detection, isolation, and quantification system for E. coli O157:H7, developed in our laboratories for retail meat sampling.

Escherichia coli O157:H7, associated with 34 reported food-borne outbreaks between 1982 and 1993 in the United States, has become recognized as a potentially lethal food-borne pathogen (4). While ground beef is the most common source of infection for E. coli O157:H7 in the United States, point source outbreaks have been traced to a variety of different foods. Some of these associated foods (e.g., apple cider and mayonnaise) illustrate the remarkable osmo- and acid tolerance properties of E. coli O157:H7 (21). This organism was first recognized in the United States but has been determined to be an epidemiologically significant cause of food-borne disease worldwide. The largest reported outbreaks (May and July of 1996), which involved 6,500 cases and 11 fatalities, occurred in Japan (2, 24). More recently, another O157:H7 outbreak in Scotland infected 260 people and caused 17 fatalities (7, 18). The largest recall of food product contaminated with E. coli O157:H7 occurred in the summer of 1997, when 25 million lb of hamburger meat was recalled by a single meat-processing company (3).

The low infectious dose (≤10 CFU) of this organism and its ability to cause any one illness or all illnesses of a devastating disease triad (hemorrhagic ulcerative colitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura) (15, 22) has prompted the U.S. Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS; Athens, Ga.) to establish a zero-tolerance threshold for E. coli O157:H7 contamination of raw meat products (1). Any level of contamination with E. coli O157:H7 is considered adulterating.

In response to the health risks associated with food contaminated with E. coli O157:H7, the U.S. Department of Agriculture is implementing hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) in existing production and processing procedures to reduce or eliminate contamination. HACCP is a management program intended to facilitate and verify the implementation of effective practices that prevent the spread of food-borne disease from farms to consumers. Compliance with HACCP legislation will require on-site sampling and laboratory testing to measure the reduction and determine the elimination of pathogen contamination in any given facility. Immediate reduction in the prevalence and quantity of microbiological pathogens in food is the contemporary concern.

Incorporating and monitoring HACCP programs is not a trivial task for meat and poultry plants, although those facilities that already have microbial intervention methods on-line will find the requirements less daunting. Issues of expense and convenience for industry must be balanced with reliable methods for satisfying HACCP regulations. As qualitative methods that are designed to detect specific microbial pathogens become less expensive and easier to use with new technology, they will undoubtedly have a role in monitoring food safety by enabling greater detection capability.

However, the importance and benefits of quantifying these pathogens should be very seriously considered when we attempt to understand the dynamics of contamination, a prime prerequisite in establishing logical and effective HACCP programs. Quantification methods are beneficial because they (i) can be used to determine the efficacy of HACCP intervention protocols in reducing pathogen contamination, (ii) will allow for comparison to national baseline data once it has been collected and assessed, and (iii) provide data for risk assessment and epidemiological studies. Current quantification techniques for E. coli O157:H7, such as direct plating and the most probable number technique, are not as cost-effective or efficient as qualitative methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based systems (16, 23), PCR-based assays (9), DNA probe systems (17), and immunomagnetic separation (25). However, none of these qualitative methods can replace the aforementioned benefits inherent in a quantitative system.

The colony lift immunoassay (CLI), a novel method for rapid immunodetection and enumeration of target pathogens following specimen preparation, has been applied to enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7. The CLI, when used in conjunction with a selective and differential medium, enables the detection, confirmation, and quantification of E. coli O157:H7 organisms after the colonies are isolated onto agar or filter monitor membranes with high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (88.9%), based on the data derived from this study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Specificities of the HRP-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody and reaction of Rainbow O157 agar in CLIs with 39 E. coli O157:H7 isolates, 54 miscellaneous E. coli serotypes, and other enteric bacteria

| Bacterial strain | UMD no.a | Reaction with anti-O157 antibodyb | Reaction color or result with Rain- bow O157 agar |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | |||

| O157:H7 | 1–20c | + | Black |

| O157:H7 | 21–28d | + | Black |

| O157:H7 | 29–34e | + | Black |

| O157:H7 | 36–39f | + | Black |

| O157:H7 | 35g | + | Black |

| O157:NM | 40–44g | + | Black |

| O1:H7 | 45g | + | Black |

| O157:H45 | 46d | + | Violet |

| O157:H3 | 47d | + | Violet |

| O127:NM | 48d | − | Dark blue |

| O28:NM | 49d | − | Violet |

| NTh | 50d | − | White |

| NT | 51d | − | Clear |

| NT | 52d | − | Orange |

| NT | 53d | − | Violet |

| NT | 54d | − | Dark blue |

| NT | 55d | − | Violet |

| NT | 56d | − | Violet |

| O157:H45 | 57i | + | Clear |

| O157:H19 | 58i | + | Red |

| O157:H25 | 59i | + | Red |

| O169:H40 | 60–67e | − | Blue-violet |

| NT | 68–70j | − | Clear |

| NT | 71j | − | Violet |

| NT | 72j | − | Dark blue |

| NT | 73j | − | Violet |

| Hafnia alvei | 74–83j | − | Clear |

| Salmonella typhi | 84k | − | No growth |

| Proteus vulgaris | 85k | − | Clear |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 86k | Weak + | No growth |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 87k | − | Pale grey, orange halo |

| Citrobacter freundii | 88k | Weak + | No growth |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 89k | − | Pale grey |

| Serratia marcescens | 90k | − | No growth |

| Salmonella group B | 91k | − | No growth |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 92k | − | No growth |

| Morganella morganii | 93k | − | No growth |

UMD, University of Maryland strain number.

CLI reactions were performed with either Rainbow O157 agar (BIOLOG) or nutrient agar (Difco).

Michael Janda Collection, Department of Health Services, Health and Welfare Agency, Berkeley, Calif.

Chinta Lamichhane collection, KPL.

Nelson Moyer collection, Hygienic Laboratory, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

James Kaper collection, Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Bonnie Rose collection, FSIS.

NT, E. coli strain that was not serotyped.

Jianghong Meng collection, Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Maryland, College Park.

Retail food isolates from ground beef.

Sam Joseph collection, Department of Microbiology, University of Maryland, College Park.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintenance and characterization of bacterial strains.

The E. coli strains of various serotypes used in this study were obtained from various sources worldwide (Table 1). We also used other enteric genera isolated from local retail beef and poultry, as well as strains from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) The E. coli isolates were subcultured (37°C, 15 to 18 h) onto nutrient agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) and confirmed biochemically and serologically in accord with the U.S. Department of Agriculture-FSIS methods (15). Briefly, these methods employ the following tests and media: triple sugar iron, sorbitol, cellobiose and lactose fermentation, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, indole, lysine and ornithine decarboxylase, Simmon’s citrate, motility, and O157 and H7 slide agglutination tests (Difco). Non-Escherichia isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae were analyzed with API 20E test strips (BioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All isolates used in this study were subcultured (15 to 18 h, 37°C) and maintained (3 to 4 months, 4°C) on nutrient agar slants in closed, screw-cap tubes.

Culture preparation.

For this study, each isolate was grown in 25 ml of sterile Trypticase soy broth (Difco) for 15 to 18 h at 36 ± 1°C. The cultures were pelleted at 3,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C (Sorvall R4B centrifuge), resuspended in 4.0 ml of buffered peptone water (Difco), and adjusted to 50% transmittance (T) on a Spectronic-20 spectrophotometer (Milton Roy, Orange, Calif.). The 50%-T culture was diluted to 10−5, from which 100 μl was inoculated onto a surface-dried nutrient agar plate by the spread plate method and incubated for 15 to 18 h at 36 ± 1°C. This technique consistently produced approximately 150 well-isolated colonies for each of the isolates when they were grown on either nutrient agar, sorbitol MacConkey’s agar (SMAC; Difco), or 202 agar (6).

Membrane evaluation.

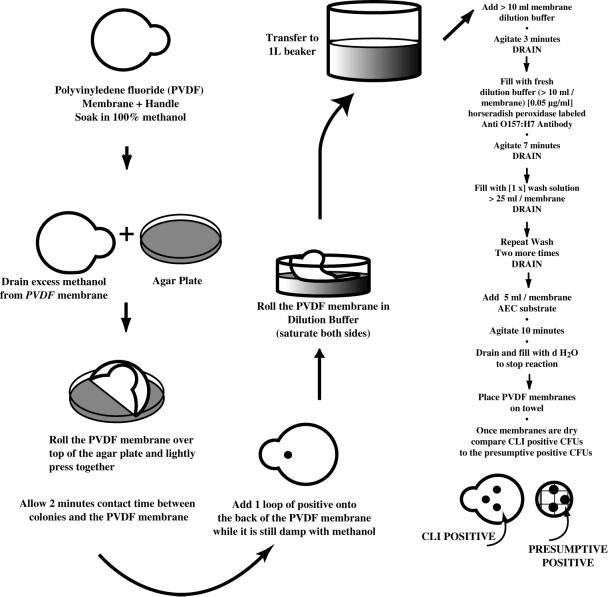

Three types of protein binding membranes were evaluated: (i) Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) hydrophobic membranes (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore); (ii) Zeta-Probe, a nylon membrane (0.45-μm pore size; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.); and (iii) Hybond-ECL, a nitrocellulose membrane (0.45-μm pore size; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). Each membrane type was cut into 4- by 1.5-cm strips. The PVDF strips required prewetting. They were saturated in 100% methanol, lightly tamped on a paper towel (to remove excess methanol), and placed while slightly damp on the surfaces of plates containing isolated colonies. After gentle pressure was applied with the wide end of a 200-μl micropipette tip to ensure antigen transfer, the PVDF membranes were removed and air dried. The other types of membranes (Zeta-Probe and Hybond-ECL) were not treated with methanol before antigen transfer. Each membrane was processed according to both the empirical and, eventually, the optimized CLI protocol (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of the optimized CLI protocol. d H2O, distilled water.

Antiserum preparation.

The antibody consisted of a polyclonal, affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157:H7 globulin (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories [KPL], Gaithersburg, Md.). The preliminary screening of all cultures (Table 1) used the following empirical conditions: 1 μg of antibody ml−1, a 4-min conjugate exposure time, and a 1-min substrate exposure time. The membranes were developed by using a one-component 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (KPL). In later experiments, aminoethyl carbazole (AEC; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Agar medium evaluation.

The agar media that were evaluated for efficacy with the CLI included nutrient agar, SMAC, 202 agar (6), and Rainbow O157 agar (BIOLOG, Inc., Hayward, Calif.). Each medium was evaluated for its use (i) in growing E. coli O157:H7, (ii) in differentiating the O157 serotype from those of other genera and from other E. coli serotypes, and (iii) as a platform from which the colonies could be lifted.

Determination of optimal conditions for the CLI. (i) Optimal antibody concentration.

Seven PVDF membranes (circular, 83-mm diameter with handles) were soaked in 100% methanol. Five different O157:H7 strains (MDL 1 to 5) and four non-O157 E. coli strains (T884, 23848, PB6472, and M1712-1) were directly inoculated with sterile loops onto sections of the surfaces of damp membranes. After the membranes were dried, each was exposed to one of seven different antibody concentrations (0.5, 0.25, 0.125, 0.062, 0.031, 0.016, and 0.008 μg ml−1) for 4 min and developed for 1 min with exposure to 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine.

(ii) Optimized conditions for CLI.

Twenty-eight circular PVDF membranes were soaked in 100% methanol and, while still damp, were used to lift colonies from nutrient agar spread plates. Each membrane contained well-defined colonies of one of four different strains of E. coli: O157:H7 (MDL 4 and MDL 5), O157:H45 (KPL 300389), and O157:H3 (KPL 300489). Each membrane was dried, blocked, and cut into seven symmetrical wedges. One representative wedge (containing several CFU) of each E. coli strain was placed into one of 28 125-ml sterile polypropylene sample containers with screw-cap lids (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.). Twenty-eight sample containers were arranged into four rows (representing antibody concentrations 0.15, 0.1, 0.05, and 0.01 μg ml−1) and seven columns (representing the conjugate incubation times 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 20 min). A 4 row by 7 column checkerboard analysis (Fig. 2) was performed under standard conditions as described below (Fig. 1) for each reaction container.

FIG. 2.

A 4 row by 7 column checkerboard assay used to optimize the antibody concentration and conjugate incubation time of the CLI. Wedge 1, O157:H45 (KPL 300386); wedge 2, O157:H3 (KPL 300489); wedges 3 and 4, O157:H7. Filled spots represent strong substrate reactions, shaded spots represent weak substrate reactions, and open spots indicate no substrate reaction.

(iii) Determination of the minimum concentration of antigen needed for a positive reaction.

An overnight Trypticase soy broth culture of O157:H7 (MDL 7) was pelleted, resuspended, and adjusted to 50% T as described above. The 50%-T culture was diluted to 10−6 in buffered peptone water by using 10-fold dilutions. For quantification, 100 μl from each dilution was spread plated onto each of three nutrient agar plates. Similarly, 5 μl from each dilution was pipetted onto a designated section of a methanol-dampened PVDF membrane, which was then processed through the optimized CLI protocol (Fig. 1).

(iv) CLI protocol.

Circular (83-mm-diameter) Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Millipore) were saturated with 100% methanol. While still damp, the membranes were laid on the surfaces of agar plates (Fig. 3) or filter monitor membranes (Fig. 4) containing presumptively positive E. coli O157:H7 colonies and tamped lightly with the wide end of a 200-μl pipette tip to ensure antigen transfer to the membrane. Single loopfuls of pure E. coli O157:H7 broth-grown cells were placed on the backs of the membranes to serve as positive controls. The PVDF membranes were then placed on a paper towel until they dried (10 to 15 min) and then transferred to blocking buffer consisting of either a commercially prepared solution (KPL) or 3% bovine serum albumin plus 0.02% Tween 20 (Sigma Chemical) suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma Chemical). The membranes were exposed for 7.5 min in blocking buffer containing 0.05 μg of the affinity-purified polyclonal HRP anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody (KPL) ml−1. The membranes were then washed three times for 4 min each time in a commercially prepared washing solution (KPL). Finally, the membranes were exposed to AEC, an HRP conjugate substrate, for 2 to 10 min, after which the reaction was stopped by rinsing the membranes in deionized water. The AEC exposure time was determined by observing the AEC reaction on the positive control spot. The membranes were air dried for 30 to 60 min before they were read. A replicate of the positive reactions was made on a transparency or the lid of a petri dish by marking the positive reactions with a felt tip marker. The replicate could then be flipped onto the original spread plate or filter membrane to match the CLI-positive replicate with the corresponding target E. coli O157:H7 colony.

FIG. 3.

Results of CLI performed on an agar plate containing isolated colonies of E. coli O157:H7 incubated for 15 to 18 h at 37°C. Arrows point to the same colony on both the PVDF membrane (left) and the nutrient agar plate (right).

FIG. 4.

Results of CLI performed on a filter monitor membrane (Biopath, Inc.) containing isolated colonies of E. coli O157:H7 incubated for 15 to 18 h at 37°C. Arrows point to the same colony on both the PVDF membrane (right) and the filter monitor membrane (left).

RESULTS

Evaluation of antibody specificity under the empirical CLI conditions.

The initial trials to determine the specificity of the antibody were performed with each strain described in Table 1. These strains were tested under empirical conditions (1 μg of antibody ml−1, 4-min conjugate exposure) as a starting point for determining the optimal conditions for the CLI. The CLI specificity was poor under these empirical conditions, producing a false-positive reaction to 42% (n = 19) of the non-O157:H7 E. coli isolates (four O169:H40 strains [FK-1, OS-2, KS-1, and OS-1], one O157:H45 strain [KPL 300389], one O157:H3 strain [KPL 300489], and two miscellaneous non-O157 E. coli strains [T884 and PB6472]). However, these initial results provided a baseline from which the antibody concentration and incubation time were optimized.

Selection of membrane and medium evaluation.

Three types of membranes were evaluated on the basis of substrate color retention, durability, and ease of use. The PVDF membranes proved superior for use in the CLI. Antigen transfer from the petri plates or filter membranes was possible only once the PVDF membranes were moistened with 100% methanol, which temporarily neutralized the hydrophobic properties of the membrane. This membrane phenomenon greatly increased the efficiency of the CLI protocol, as many membranes could be processed in the same reaction chamber without antigen cross-contamination between the membranes. Because the PVDF membranes were easy to use, were much more durable than the nitrocellulose membranes, and had better color retention than the Zeta-Probe membranes, the PVDF membranes were used for optimizing the CLI procedure.

The solid media were evaluated for their ability to serve as a platform from which bacterial antigen could be transferred to the PVDF membranes during the CLI procedure. Effective antigen transfer was based on three characteristics, the first being the ability to support the growth of E. coli O157:H7 to produce enough antigenic mass for visualization by the CLI, the second being the ability of the PVDF membranes to bind antigen from the agar surface without discoloration of the membranes, and the third being the ability of some bacterial cells to remain viable on the agar surface for further characterization. Coloration of the PVDF membranes by anything other than the substrate reaction is undesirable, because contaminating substances may interfere with interpretation of the CLI results.

The 202 agar imbued a blue-green color to many non-sorbitol-fermenting colonies (including typical O157:H7) and discolored the PVDF membranes during the antigen transfer step, but this discoloration was eliminated during the washing step in the CLI procedure. Levels of growth of E. coli O157:H7 on nutrient agar, SMAC, and 202 agar were comparable (data not shown), and the CLI methodology showed equivalent results with each type of medium.

Because the antibody is not 100% specific for the H7 antigen (Table 1), we used a new medium (Rainbow O157 agar; BIOLOG, Inc.) to chromogenically differentiate O157:H7 strains (black) from non-O157:H7 strains (various shades of violet or blue) of E. coli. The chromogenicity is based on the two enzymes glucuronidase and galactosidase. Strains that were previously confirmed as either E. coli O157:H7 or E. coli O157:NM by biochemical and serological methods turned black on Rainbow O157 agar and were positive by the CLI assay.

Optimal antibody concentration.

The preliminary study to determine the optimal concentration of the HRP-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody concentration was designed to reveal the intended effects of extreme antibody concentrations (false-positive and false-negative reactions) in the CLI protocol. The substrate reactions were very weak and gradually faded beyond recognition with antibody dilutions greater than or equal to 0.03125 μg ml−1 (data not shown). The antibody concentration that worked best in the preliminary investigation of a single incubation time was 0.0625 μg ml−1, based on substrate color retention for the true positives and the absence of substrate color for the true negatives.

The antibody concentration and the conjugate incubation time were further optimized by using two false-positive strains, O157:H45 (KPL 300386) and O157:H3 (KPL 300489), which were chosen because of their initial weak reaction with the O157-agglutinating antisera (Difco) during preliminary testing. These strains, along with the two O157:H7 strains (MDL 4 and 5), provided excellent measures of specificity for the further refinement of an effective antibody concentration and conjugate incubation time for use in the CLI.

A checkerboard-type assay (4 rows by 7 columns) was performed with 28 sterile 125-ml polypropylene specimen containers (Fisher Scientific) as reaction chambers (Fig. 2). Each chamber contained four identically prepared PVDF membranes, with several E. coli colony transfers of a single serotype on each membrane (O157:H45, O157:H3, and two O157:H7 strains). The reactions were performed according to the CLI protocol (Fig. 1), with various conjugate exposure times from 1 to 20 min and concentrations of the antibody from 0.15 to 0.01 μg ml−1. Optimal antibody concentration and exposure time combinations were those that gave the darkest (strongest) substrate reaction for the E. coli O157:H7 strains and the lightest (weakest) substrate reactions for the E. coli O157:non-H7 strains.

Optimal antibody concentration and incubation time.

It was determined that the optimal conditions for the CLI assay were 0.05 μg of HRP-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody (KPL) ml−1 with a 6- to 9-min conjugate incubation (with an average time of 7.5 min). These conditions were used to further screen 39 E. coli O157:H7, 24 E. coli non-O157, and 10 E. coli O157:non-H7 isolates (Table 1). The CLI assay produced true-positive recognition of 100% (39 of 39) of the O157:H7 isolates, false-positive recognition of 100% (10 of 10) of the E. coli O157:non-H7 isolates, and false-positive recognition of 4.1% (1 of 24) of the E. coli non-O157 isolates tested.

Determination of minimum antigen needed for a positive CLI.

The CLI procedure is very sensitive and requires minimal antigen to obtain a positive reaction. Roughly 750 cells of E. coli O157:H7 suspended in 5 μl of 0.85% saline were distributed in a 1.0-mm2 spot onto a methanol-dampened PVDF membrane. The antigen produced a visible reaction after the CLI procedure was performed. Similarly, the CLI reaction on spread plates with pure cultures incubated for less than 5 h were positive in the absence of visible colonies on the culture medium.

DISCUSSION

A CLI for the detection and quantification of E. coli O157:H7 was successfully developed, optimized, and evaluated. Optimization involved the determination of the appropriate membrane and substrate types, antibody concentration, and exposure time. PVDF membranes (Millipore) were selected for use with the CLI, because of their durability, ease of use, and good retention of the substrate color reaction. Furthermore, once saturated in methanol, the hydrophobic PVDF material appeared to have a higher affinity for the protein (antigen) attachment. The antigen transfer step, however, had to be performed while the PVDF membrane was still moist with 100% methanol. Up to 20 membranes could be processed in a single reaction mixture with little risk of antigen cross-contaminating the membranes. The brief exposure of the colonies to methanol on the agar surface did not adversely affect their viability, which allowed subculturing for biochemical and serological testing and storage.

Available detection methods for E. coli O157:H7 focus on several characteristics that distinguish the O157:H7 strain from other serotypes of E. coli. For example, most O157:H7 strains lack the enzyme glucuronidase, in contrast to an estimated 94 to 97% of other E. coli strains that have the enzyme (13). Another distinction is that approximately 95% of all E. coli strains tested ferment d-sorbitol within 24 h, while E. coli O157:H7 is a slow sorbitol fermenter (8). Various culture media that use a combination of these and other biochemical tests to differentiate E. coli O157:H7 from other E. coli strains have been described (5, 8, 19, 20). While the importance of the primary selective plating media for screening is recognized, there is an increasing need for more efficient, rapid, and quantitative detection of E. coli O157:H7. Despite the concern for better methodology in the United States, primary culture techniques using basic SMAC are still the most commonly used methods for the detection and isolation of E. coli O157:H7.

The increasing significance of both variant O157:H7 strains and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic E. coli isolates as determinants of food-borne disease worldwide has focused much attention on rapid diagnostic methods that can detect these emerging strains as well as O157:H7 (10, 11, 17). In recognition of the fact that traditional culture methods are currently the most often used methods for detecting E. coli O157:H7, the CLI was developed to enhance the efficacy, sensitivity, and specificity of traditional culture systems. One benefit of incorporating the CLI into traditional culture systems for E. coli O157:H7 is the ability to screen all presumptively positive colonies (i.e., sorbitol-negative colonies) on a spread plate simultaneously for the presence of the E. coli O157 antigen. This advantage allows the CLI assay to be easily used as a quantification tool when it is performed on several spread plates per sample. The sensitivities of currently used quantification methods such as the most probable number technique could be improved in the confirmation step by replacing the five-colony pick method with the CLI procedure.

Most commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays incorporate a polyclonal E. coli O157:H7 antibody instead of a monoclonal alternative, perhaps because of the ease and low cost of preparation of the polyclonal antibody, the inability of the monoclonal antibody to achieve a significant increase in specificity, and the retention of greater sensitivity with the polyclonal antibody. Because polyclonal antibodies have been shown to be more sensitive than monoclonal antibodies, while retaining specificity, we decided to use a polyclonal affinity-purified HRP-labeled goat anti-E. coli O157:H7 antibody (KPL). This antibody has been shown to be reactive to E. coli O157:H7 and specific for the O157 lipopolysaccharide antigen (Fig. 1).

Rainbow O157 agar (BIOLOG, Inc.), a new selective and differential medium, was incorporated into the SELeCT system (14) (an acronym for a diagnostic system of isolation, identification, and detection of Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Campylobacter spp. in raw red meat and poultry) of isolation and identification of E. coli O157:H7 in foods to enhance the specificity for E. coli O157:H7. The selective properties of this medium prevented most non-E. coli organisms from growing, and its unique chromogenic properties differentiated the O157:H7 strain from other serotypes of E. coli (Table 1), thus increasing the specificity for detecting E. coli O157:H7 from 75.9 to 88.9%. Thus, the biochemical activity of the agar medium combined with the serological response essentially provided assurance of identification. Further confirmation was obtained with slide agglutination antiserum, which is an option for excluding possible false-positive strains. Actually in this instance, only H7 antiserum is required (8, 12). Rainbow O157 agar was not found to be inhibitory to any E. coli O157:H7 strains in quantitative comparison studies with Trypticase soy agar, 202 agar, and SMAC (data not shown).

In summary, the CLI is an effective and efficient method for detecting and quantifying E. coli O157:H7 on solid media and when used in conjunction with the E. coli SELeCT system (14), it can be used to detect and quantify less than 1 CFU/g in a 25-g red meat or poultry sample within 24 h. While the CLI has been shown to detect viable colonies of E. coli O157:H7 from spread plates following as few as 5 h of incubation under optimal growth conditions, the specificity of the test for E. coli O157:H7 with this shortened incubation period is yet to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture contract FSIS-15-W-94.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association for Food Hygiene Veterinarians. FSIS publishes final rule on pathogen reduction and HACCP systems. News-O-Gram. 1996;20:16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler D. Novel pathogens beat food safety checks. Nature. 1996;384:397. doi: 10.1038/384397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with eating a nationally distributed commercial brand of frozen ground beef patties and burgers—Colorado, 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;43:777–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Epidemiology & Animal Health. A public health concern: Escherichia coli O157:H7. Newsletter N131.0194. Fort Collins, Colo: Centers for Epidemiology & Animal Health, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture Veterinary Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman P A, Siddons C A, Zadik P M, Jewes L. An improved selective medium for the isolation of Escherichia coli O157. J Med Microbiol. 1991;35:107–110. doi: 10.1099/00222615-35-2-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chuang K. M.S. thesis. Manhattan: Kansas State University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombes R. A fatal strain. Nursing Times. 1997;93(4):16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer J J I, Davis B R. H7 antiserum-sorbitol fermentation medium: a single tube screening medium for detecting Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with hemorrhagic colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:620–625. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.4.620-625.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fratamico P M, Sackitey S K, Wiedmann M, Deng M Y. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2188–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2188-2191.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;113:199–207. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunzer F, Bohn H, Russman H. Molecular detection of sorbitol-fermenting Escherichia coli O157 in patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Infect Immun. 1992;30:1807–1810. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1807-1810.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Y, Keen J E, Westerman R B, Littledike E T, Kwang J. Monoclonal antibodies for detection of the H7 antigen of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3325–3332. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3325-3332.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang S W, Chang C H, Tai T F, Chang T C. Comparison of the β-glucuronidase assay and the conventional method for identification of Escherichia coli on eosin-methylene blue agar. J Food Prot. 1997;60:6–9. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-60.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingram D T, Rigakos C G, Rollins D M, Mallinson E T, Carr L, Joseph S W. Abstracts of the 96th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1996. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Development of a 24hr assay (E. coli SELeCT) for the isolation, quantification and confirmation of E. coli O157:H7 in poultry and red meat, abstr. P-4; p. 369. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson J L, Rose B E, Sharar A K, Ransom G M, Lattuada C P, McNamara A M. Methods used for detection and recovery of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with a foodborne disease outbreak. J Food Prot. 1995;58:597–603. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson R P, Durham R J, Johnson S T, MacDonald L A. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in meat by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, EHEC-Tek. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:386–388. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.386-388.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine M M, Xu J, Kaper J B, Lior H, Prado V, Tall B, Nataro J, Helge K, Wachsmuth K. A DNA probe to identify enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli of O157:H7 and other serotypes that cause hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:175–182. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liddell K G. Escherichia coli O157:outbreak in central Scotland. Lancet. 1997;349:502–503. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.March S B, Ratman S. Sorbitol-MacConkey medium for detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with hemorrhagic colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:869–872. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.5.869-872.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okrend A J G, Rose B E, Lattuada C P. Use of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl-β-d-glucuronide in MacConkey sorbitol agar to aid in the isolation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from ground beef. J Food Prot. 1990;53:941–943. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.11.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semanchek J J, Golden D A. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 during fermentation of apple cider. J Food Prot. 1996;59:1256–1259. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.12.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su C, Brandt L J. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in humans. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:698–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-9-199511010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toth I, Barrett T J, Cohen M L, Rumshlag H S, Green J H, Wachsmuth I K. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for products of the 60-megadalton plasmid of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1016–1019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.5.1016-1019.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe H, Wada A, Inagaki Y, Itoh K-I, Tamura K. Outbreaks of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection by two different genotype strains in Japan, 1996. Lancet. 1996;348:831–832. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu H, Bruno J G. Immunomagnetic-electrochemiluminescent detection of Escherichia coli O157 and Salmonella typhimurium in foods and environmental water samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:587–592. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.587-592.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]